1. Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) stands as the most common cardiac arrhythmia globally [

1,

2]. Its prevalence is rising, and it is associated with severe complications, including a significantly increased risk of stroke and heart failure, as well as higher overall mortality [

1,

3,

4]. A significant challenge in managing AF is the existence of subclinical or asymptomatic episodes. These episodes, often missed by traditional diagnostic methods like standard ECGs, still contribute to the overall disease burden and risk [

5,

6]. Patients with cardiac implantable electronic devices (CIEDs), such as permanent pacemakers, offer a unique opportunity for study. These devices can continuously monitor the atrial rhythm, allowing for the detection of asymptomatic atrial high-rate episodes (AHRE), which are considered a form of subclinical atrial fibrillation [

5,

7]. AHRE itself has been linked to a 2.5-fold increased risk of stroke [

8].

Identifying which patients will develop these arrhythmias is crucial for prevention. While traditional cardiovascular risk factors are known, they do not fully account for an individual’s risk of developing AF. This has led to a search for blood-based biomarkers that could improve risk prediction and enhance understanding of the underlying pathophysiology. Various markers reflecting processes like atrial strain, inflammation, and myocardial fibrosis have been investigated [

9].

Among the most studied biomarkers, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), an indicator of myocardial stretch, has been consistently suggested as a strong predictor for incident AF [

10]. Another key biomarker is cardiac troponin, a protein released following myocardial cell injury. While critical for diagnosing acute coronary syndromes, elevated troponin levels are also found in other conditions, including supraventricular tachyarrhythmias. The conditions that lead to the development of AF may also cause a rise in troponin levels. Although some community-based studies have confirmed an association between elevated troponin and the subsequent development of AF [

11], the overall scientific evidence remains limited. Furthermore, its specific value as an independent risk marker, particularly when compared to established biomarkers like NT-proBNP, is not yet certain.

This study was conducted to explore the role of high-sensitivity troponin I (hs-cTnI) in predicting new-onset atrial high-rate episodes (AHRE) in patients with permanent pacemakers. This specific population allows for the accurate detection of subclinical arrhythmias, providing a valuable opportunity to determine if baseline hs-cTnI levels can serve as a predictor for the future development of AHRE.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

We conducted a prospective cohort study at the Department of Arrhythmia Treatment and the Department of Biochemistry at Cho Ray Hospital, Vietnam. The study enrolled adult patients (≥ 18 years) who had a clinical indication for and agreed to undergo permanent pacemaker implantation between September 2023 and August 2026. All participants provided written informed consent. We excluded patients who were critically ill with a high risk of mortality, pregnant, had an indication for surgery, or had severe renal impairment defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of ≤ 30 mL/min/1.73m².

2.2. Data Collection and Baseline Assessment

Baseline clinical data was collected from patient medical records and clinical examinations prior to pacemaker implantation. This included demographics (age, sex), anthropometrics (Body Mass Index, BMI), and medical history, including cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, heart failure (HF), and prior stroke. Standard 12-lead ECGs and transthoracic echocardiogram results, including left atrial (LA) diameter and left ventricular ejection fraction (EF), were also recorded.

2.3. Biomarker Measurement

Blood samples for measuring high-sensitivity troponin I (hs-cTnI) and N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) were collected from all patients before the pacemaker implantation procedure. All assays were performed at the Department of Biochemistry at Cho Ray Hospital using a Siemens ADVIA Centaur XPT automated immunoassay system. hs-cTnI was measured using a 3-site sandwich immunoassay utilizing direct chemiluminescence technology. NT-proBNP was measured using a 2-site sandwich immunoassay, also utilizing direct chemiluminescence technology.

2.4. Outcome Definition and Follow-Up

Patients were divided at baseline into those with pre-existing AF (n=40) and those without (n=232). The non-AF group (n=232), which constituted the at-risk population, was followed prospectively for a median of 12 months to monitor for the primary endpoint. The primary endpoint was the first detection of new-onset Atrial High-Rate Episodes (AHRE) or clinical AF. Follow-up was conducted during routine pacemaker interrogation appointments. The diagnosis of an event was based on data from the cardiac implantable electronic device (CIED) or a standard ECG. Clinical Atrial Fibrillation (AF) was defined according to the 2020 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines as a 12-lead ECG or a single-lead ECG strip of ≥ 30 seconds showing a heart rhythm with no discernible repeating P waves and irregular RR intervals [

12]. Atrial High-Rate Episodes (AHRE) were defined according to American Heart Association (AHA) criteria as device-detected atrial tachyarrhythmias that met a programmed rate threshold (typically 175–220 bpm) [

13] and were confirmed by visual inspection of the stored intracardiac electrograms.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using R software. Continuous variables were assessed for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Normally distributed data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and compared using Student’s t-test, while non-normally distributed data were presented as median and interquartile range (IQR) and compared using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Categorical variables were reported as frequencies (n) and percentages (%) and compared using the Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. The cumulative incidence of new-onset AHRE was analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method, and differences between groups (based on baseline biomarker quartiles) were assessed using the log-rank test. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression was used to identify independent predictors for the incidence of AHRE, including baseline hs-cTnI levels and other clinical, echocardiographic, and laboratory factors. A two-sided p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

2.6. Ethical Considerations

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Medicine and Pharmacy at Ho Chi Minh City and Cho Ray Hospital. The research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent prior to any study-related procedures.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Population and Baseline Characteristics

A total of 285 patients were initially screened for the study. After excluding 13 patients who had an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) below 30 mL/min/1.73m², the final study cohort consisted of 272 patients. This cohort was stratified at baseline into 40 patients with pre-existing atrial fibrillation and 232 patients without atrial fibrillation. This group of 232 patients constituted the at-risk population for analyzing the prediction of new-onset arrhythmias.

The baseline characteristics of this at-risk cohort (n=232) are presented in

Table 1. The mean age was 63.7 ± 14.0 years, and 124 (53.4%) were male. The mean body mass index (BMI) was 22.5 ± 3.34 kg/m². The most prevalent comorbidities in this group were hypertension (59.0%), dyslipidemia (40.5%), diabetes mellitus (22.0%), and heart failure (18.0%).

For the total cohort (n=272), the primary indications for pacemaker implantation were AV block (34.91%) and sick sinus syndrome (33.09%). The majority of patients (66.9%) received a dual-chamber pacemaker.

3.2. Incidence of Atrial High-Rate Episodes (AHRE)

Over a median follow-up period of 12.0 months (Interquartile Range [IQR] 6.75–13.0 months), 65 of the 232 at-risk patients (28.0%) developed new-onset AHRE as detected by their implanted device.

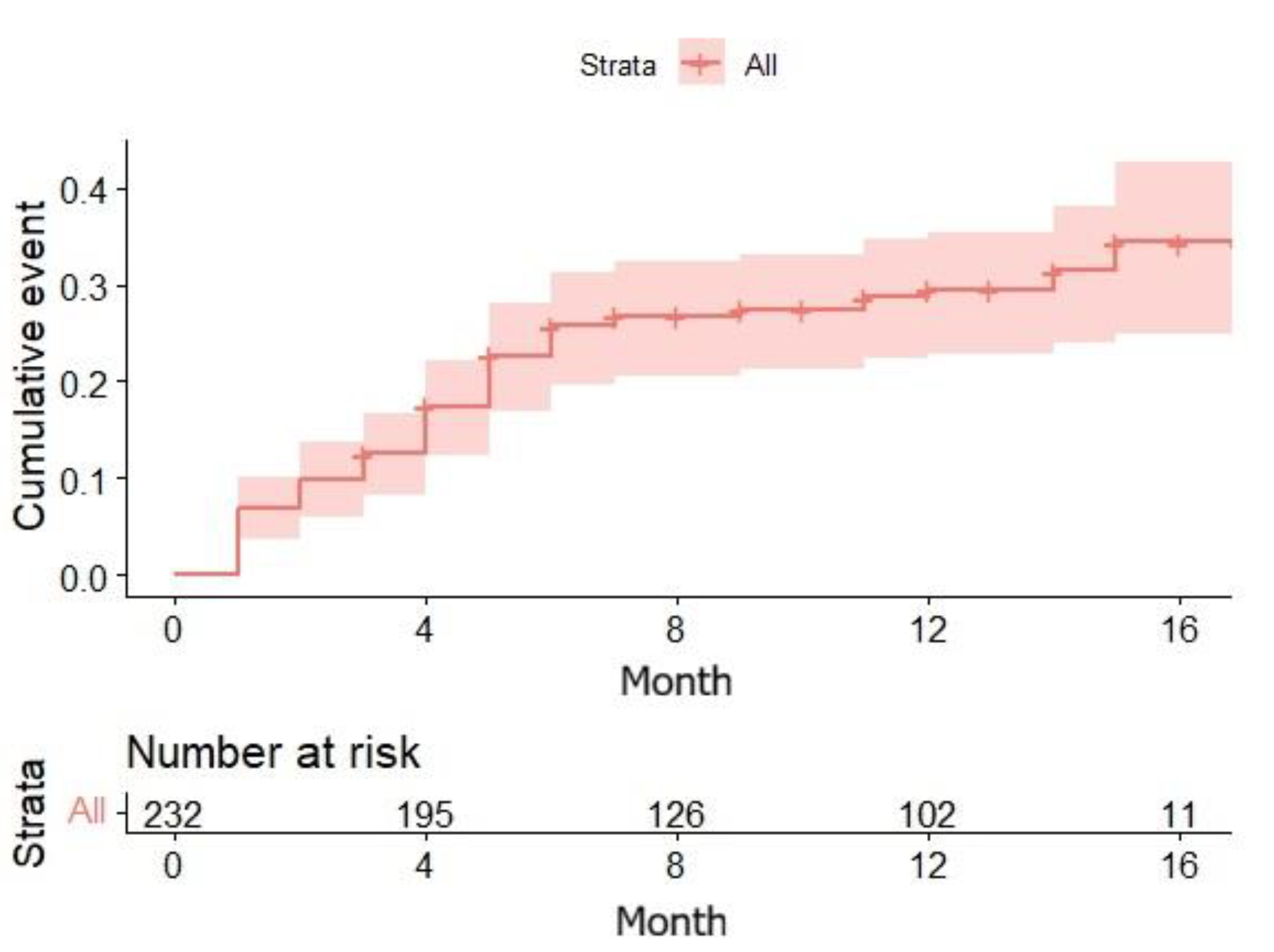

The Kaplan-Meier analysis showed a cumulative probability of developing AHRE of approximately 30% at 12 months, increasing to approximately 35% by 17 months. Among the 65 patients who developed AHRE, the duration of the longest recorded episode was less than 30 seconds in 46% of cases, between 30 seconds and 6 minutes in 40% of cases, and greater than 6 minutes in 14% of cases.

3.3. Baseline hs-cTnI, NT-proBNP, and Risk of New-Onset AHRE

We compared the baseline biomarker levels between the patients who developed AHRE and those who remained free of AHRE during the follow-up period.

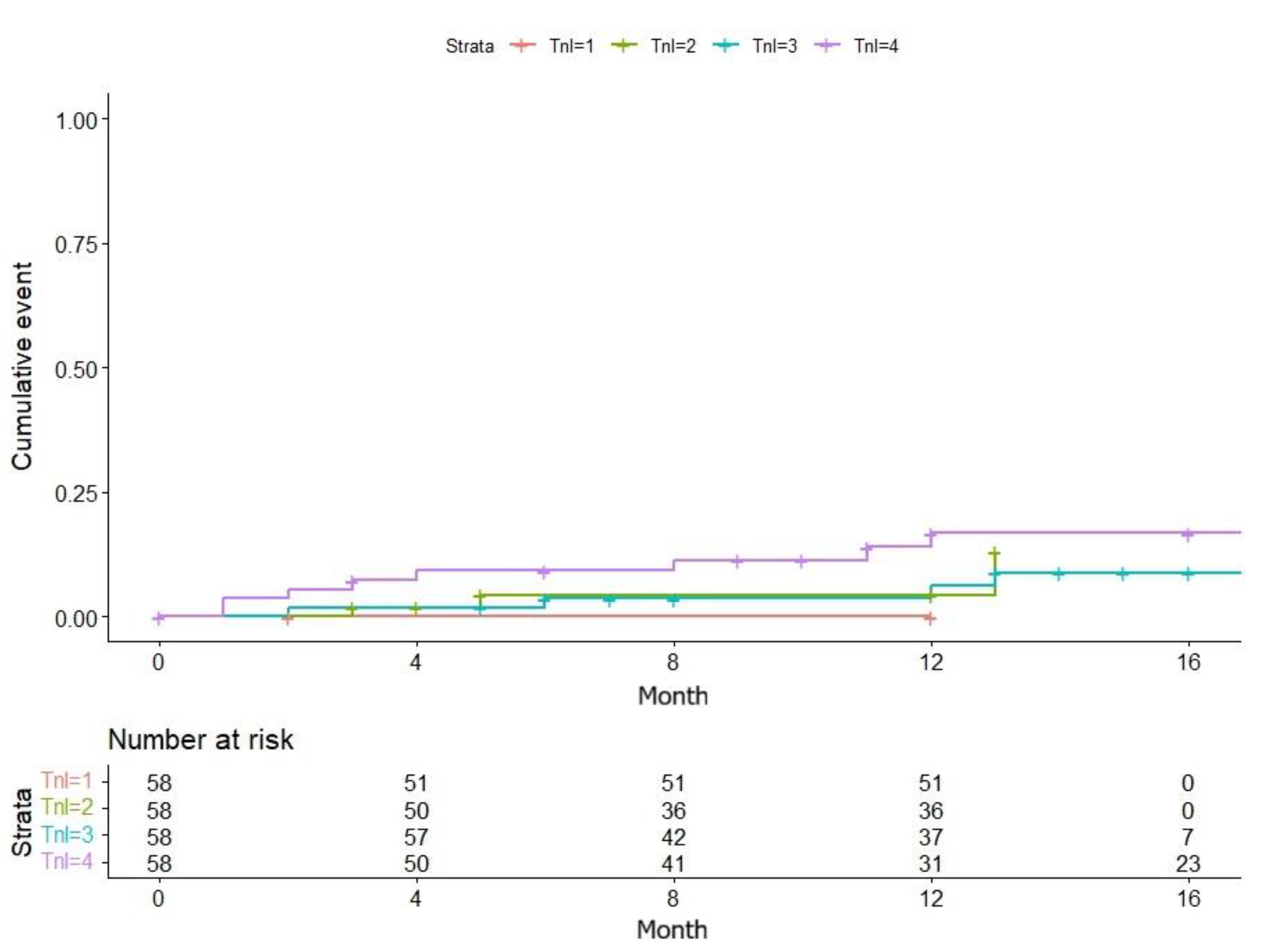

The median baseline hs-cTnI level was not statistically different between the two groups. The AHRE group (n=65) had a median hs-cTnI of 16.5 pg/mL (IQR 5.61–80.9), compared to 15.7 pg/mL (IQR 4.06–95.3) in the no-AHRE group (n=167) (Wilcoxon rank-sum test, p = 0.148). A Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, stratified by baseline hs-cTnI quartiles, confirmed this finding, showing no significant difference in the cumulative incidence of AHRE across the quartiles (Log-rank test, p = 0.9).

Similarly, baseline NT-proBNP levels did not predict the development of AHRE. The median NT-proBNP level was 37.1 pmol/L (IQR 10.7–153.7) in the group that developed AHRE, compared to 32.9 pmol/L (IQR 7.07–157) in the group that did not (Wilcoxon rank-sum test, p = 0.396). The Kaplan-Meier analysis stratified by NT-proBNP quartiles also showed no significant difference in the cumulative event rate (Log-rank test, p = 0.2).

3.4. Multivariable Cox Proportional-Hazards Analysis for Predictors of New-Onset AHRE

A multivariable Cox proportional-hazards analysis was performed to identify independent predictors of new-onset AHRE among the 232 patients in the at-risk cohort. The results are detailed in

Table 2.

After adjusting for other covariates, baseline biomarker levels were not associated with the development of AHRE. Neither hs-cTnI (per log-unit increase) (HR 1.02, 95% CI 0.84–1.23, p = 0.850) nor NT-proBNP (per log-unit increase) (HR 1.07, 95% CI 0.90–1.28, p = 0.430) were significant predictors.

In contrast, several clinical and echocardiographic factors were strong independent predictors of new-onset AHRE. The strongest predictor was a pacing indication of Sick Sinus Syndrome (compared to AV Block), which more than doubled the risk (HR 2.10, 95% CI 1.35–3.26, p < 0.001). A history of Heart Failure (HR 1.78, 95% CI 1.15–2.76, p = 0.010) and Hypertension (HR 1.65, 95% CI 1.08–2.51, p = 0.020) were also significantly associated with increased risk.

Additionally, increasing Age (per 10-year increase) (HR 1.42, 95% CI 1.10–1.83, p = 0.007) and a larger Left Atrial Diameter (per 1-mm increase) (HR 1.15, 95% CI 1.04–1.27, p = 0.006) were significant predictors. Male sex and LVEF were not found to be independently associated with AHRE in this model.

4. Discussion

This prospective cohort study was designed to test the hypothesis that baseline high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I (hs-cTnI) could predict the development of new-onset atrial high-rate episodes (AHRE) in patients requiring permanent pacemakers. We also evaluated the predictive utility of NT-proBNP. The primary finding of our study was twofold: First, we observed a high incidence (28.0%) of subclinical AHRE within a median 12-month follow-up period. Second, and contrary to our initial hypothesis, baseline levels of both hs-cTnI and NT-proBNP failed to predict the development of AHRE, both in unadjusted analyses and, crucially, in our multivariable Cox proportional-hazards model. The multivariable analysis instead revealed that established clinical and echocardiographic factors - specifically Sick Sinus Syndrome, Heart Failure, Hypertension, advancing Age, and Left Atrial Diameter - were the dominant independent predictors of AHRE.

Our negative findings regarding hs-cTnI and NT-proBNP are in notable contrast to some community-based studies that have linked these biomarkers to the development of clinical atrial fibrillation [

10,

11,

14,

15,

16]. This discrepancy may be explained by fundamental differences in both the study population and the primary endpoint. Our cohort consisted of a high-risk population with established, significant conduction system disease (i.e., AV block or sick sinus syndrome) warranting pacemaker implantation, rather than a general community population. Furthermore, our endpoint was device-detected subclinical AHRE, which may represent a different pathophysiological stage than symptomatic, clinical AF [

17,

18]. Conversely, our positive findings - that age, LA diameter, hypertension, and heart failure are predictive - are highly consistent with the established understanding of the atrial remodeling process that forms the substrate for atrial arrhythmias [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23].

We propose that in this specific high-risk cohort, the advanced, established electrical and structural disease - the very factors necessitating pacemaker implantation—are the overwhelming drivers of AHRE development [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. The strong independent predictive power of Sick Sinus Syndrome (HR 2.10), a primary atrial electrical disease, and structural markers like Heart Failure (HR 1.78) and LA Diameter (HR 1.15) supports this hypothesis. In this context, the subtle information provided by biomarkers of subclinical myocardial injury (hs-cTnI) or myocardial stretch (NT-proBNP) may be masked or rendered non-significant by these dominant, pre-existing pathological factors [

30,

31,

32,

33]. The disease substrate may already be too advanced for these initiating biomarkers to offer additional predictive value.

The clinical implications and significance of these findings relate directly to risk stratification. Our results suggest that a single, baseline measurement of hs-cTnI or NT-proBNP is not a useful tool for identifying pacemaker patients at high short-term risk for developing subclinical AHRE. Instead, clinicians should focus on the readily available clinical and echocardiographic factors that were confirmed as independent predictors in our model: pacing indication (Sick Sinus Syndrome), a history of Heart Failure or Hypertension, patient Age, and Left Atrial Diameter.

Our study has several notable strengths, including its prospective cohort design, the use of objective, continuous device-based monitoring for the accurate detection of the AHRE endpoint, and the standardized collection and analysis of all biomarkers at a central laboratory prior to implantation. However, limitations must be acknowledged. As a single-center study conducted in Vietnam, the generalizability of our findings to other ethnic groups or healthcare systems may be limited. Furthermore, the median follow-up of 12.0 months is relatively short. The Kaplan-Meier curve (

Figure 1) had not yet plateaued, suggesting that a longer observation period might be necessary to identify predictors of late-onset AHRE, for which these biomarkers might yet have a role.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier comparison of new-onset AHRE cases by baseline hs-cTnI concentration quartiles.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier comparison of new-onset AHRE cases by baseline hs-cTnI concentration quartiles.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this prospective study of 232 patients receiving permanent pacemakers found a high 12-month incidence of new-onset subclinical atrial high-rate episodes (AHRE) at 28.0%. However, contrary to our hypothesis, we found no evidence that baseline levels of either high-sensitivity troponin I or NT-proBNP could predict the development of these arrhythmias in this high-risk population. These findings highlight the potential limitations of using biomarkers validated in the general population for specialized patient cohorts. Future research should focus on other predictive models, potentially incorporating longer follow-up and multivariable adjustments, to better identify pacemaker patients at the highest risk for developing AHRE.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.H.K.L., L.V.N., and T.T.V.; Methodology, D.H.K.L. and L.V.N.; Formal analysis, D.H.K.L.; Investigation, D.H.K.L.; Data Curation, D.H.K.L.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, D.H.K.L.; Writing – Review & Editing, D.H.K.L., L.V.N., and T.T.V.; Supervision, L.V.N. and T.T.V.; Project administration, D.H.K.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was granted ethical approval by the Ethics Council in Biomedical Research of University of Medicine and Pharmacy at Ho Chi Minh City under the approval number 806/HDDD-DHYD on September 22, 2023. The study was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT06174506) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. All participants provided written informed consent prior to any study-related procedures.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author (Linh Ha Khanh Duong).

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to all the patients who graciously agreed to participate in this research. We also extend our heartfelt thanks to the dedicated medical, nursing, and technical staff of the Department of Arrhythmia Treatment and the Department of Biochemistry at Cho Ray Hospital for their invaluable assistance in patient recruitment, clinical data collection, and biomarker analysis. This study received institutional support from Cho Ray Hospital and the University of Medicine and Pharmacy at Ho Chi Minh City.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Brundel, B.; Ai, X.; Hills, M.T.; Kuipers, M.F.; Lip, G.Y.H.; de Groot, N.M.S. Atrial fibrillation. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2022, 8, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippi, G.; Sanchis-Gomar, F.; Cervellin, G. Global epidemiology of atrial fibrillation: An increasing epidemic and public health challenge. Int J Stroke 2021, 16, 217–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linz, D.; Gawalko, M.; Betz, K.; Hendriks, J.M.; Lip, G.Y.H.; Vinter, N.; Guo, Y.; Johnsen, S. Atrial fibrillation: epidemiology, screening and digital health. Lancet Reg Health Eur 2024, 37, 100786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svennberg, E.; Freedman, B.; Andrade, J.G.; Anselmino, M.; Biton, Y.; Boriani, G.; Brandes, A.; Buckley, C.M.; Cameron, A.; Clua-Espuny, J.L.; et al. Recent-onset atrial fibrillation: challenges and opportunities. Eur Heart J 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boriani, G.; Tartaglia, E.; Trapanese, P.; Tritto, F.; Gerra, L.; Bonini, N.; Vitolo, M.; Imberti, J.F.; Mei, D.A. Subclinical atrial fibrillation/atrial high-rate episodes: what significance and decision-making? Eur Heart J Suppl 2025, 27, i162–i166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aletras, G.; Koutalas, E.; Bachlitzanaki, M.; Stratinaki, M.; Bachlitzanaki, I.; Stavratis, S.; Garidas, G.; Pitarokoilis, M.; Foukarakis, E. Paroxysmal Supraventricular Tachycardia and Troponin Elevation: Insights into Mechanisms, Risk Factors, and Outcomes. J Clin Med 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orozco-Burbano, J.D.; Chara-Salazar, C.J.; Vargas-Zabala, D.L.; Castillo-Concha, J.S.; Agudelo-Uribe, J.F.; Ramirez-Barrera, J.D. Clinical relevance and management of atrial high-rate episodes: a narrative review. Arch Cardiol Mex 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, J.S.; Connolly, S.J.; Gold, M.R.; Israel, C.W.; Van Gelder, I.C.; Capucci, A.; Lau, C.P.; Fain, E.; Yang, S.; Bailleul, C.; et al. Subclinical atrial fibrillation and the risk of stroke. N Engl J Med 2012, 366, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafaqat, S.; Rafaqat, S.; Ijaz, H. The Role of Biochemical Cardiac Markers in Atrial Fibrillation. J Innov Card Rhythm Manag 2023, 14, 5611–5621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieweke, J.T.; Pfeffer, T.J.; Biber, S.; Chatterjee, S.; Weissenborn, K.; Grosse, G.M.; Hagemus, J.; Derda, A.A.; Berliner, D.; Lichtinghagen, R.; et al. miR-21 and NT-proBNP Correlate with Echocardiographic Parameters of Atrial Dysfunction and Predict Atrial Fibrillation. J Clin Med 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borschel, C.S.; Geelhoed, B.; Niiranen, T.; Camen, S.; Donati, M.B.; Havulinna, A.S.; Gianfagna, F.; Palosaari, T.; Jousilahti, P.; Kontto, J.; et al. Risk prediction of atrial fibrillation and its complications in the community using hs troponin I. Eur J Clin Invest 2023, 53, e13950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindricks, G.; Potpara, T.; Dagres, N.; Arbelo, E.; Bax, J.J.; Blomstrom-Lundqvist, C.; Boriani, G.; Castella, M.; Dan, G.A.; Dilaveris, P.E.; et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS): The Task Force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J 2021, 42, 373–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noseworthy, P.A.; Kaufman, E.S.; Chen, L.Y.; Chung, M.K.; Elkind, M.S.V.; Joglar, J.A.; Leal, M.A.; McCabe, P.J.; Pokorney, S.D.; Yao, X.; et al. Subclinical and Device-Detected Atrial Fibrillation: Pondering the Knowledge Gap: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2019, 140, e944–e963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhou, T.; Li, J.; Yuan, C.; Li, C.; Chen, S.; Shen, C.; Gu, D.; Lu, X.; Liu, F. Association between NT-proBNP levels and risk of atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Heart 2025, 111, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugnicourt, J.M.; Rogez, V.; Guillaumont, M.P.; Rogez, J.C.; Canaple, S.; Godefroy, O. Troponin levels help predict new-onset atrial fibrillation in ischaemic stroke patients: a retrospective study. Eur Neurol 2010, 63, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ocak, M.; Tascanov, M.B. Clinical value of the combined use of P-wave dispersion and troponin values to predict atrial fibrillation recurrence in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Rev Port Cardiol (Engl Ed) 2021, 40, 679–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.A.; Boriani, G.; Lip, G.Y.H. Are atrial high rate episodes (AHREs) a precursor to atrial fibrillation? Clin Res Cardiol 2020, 109, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, P.; Zhao, X.; Li, X.; Geng, J.; Ni, S.; Li, Q. Pathophysiology, molecular mechanisms, and genetics of atrial fibrillation. Hum Cell 2024, 38, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoun, I.; Layton, G.R.; Nizam, A.; Barker, J.; Abdelrazik, A.; Eldesouky, M.; Koya, A.; Lau, E.Y.M.; Zakkar, M.; Somani, R.; et al. Hypertension and Atrial Fibrillation: Bridging the Gap Between Mechanisms, Risk, and Therapy. Medicina (Kaunas) 2025, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koniari, I.; Bozika, M.; Nastouli, K.M.; Tzegka, D.; Apostolos, A.; Velissaris, D.; Leventopoulos, G.; Perperis, A.; Kounis, N.G.; Tsigkas, G.; et al. The Role of Early Risk Factor Modification and Ablation in Atrial Fibrillation Substrate Remodeling Prevention. Biomedicines 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parajuli, P.; Alahmadi, M.H.; Ahmed, A.A. Left Atrial Enlargement. In StatPearls; Treasure Island (FL) ineligible companies. Disclosure: Mohamed Alahmadi declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies. Disclosure: Andaleeb Ahmed declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J.F.; Hu, J.; Fu, H.X.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, M.; Zhang, P.P.; Yu, Y.C.; Wang, Q.S.; Sun, J.; Li, Y.G. The risk factors of atrial substrate remodeling in the patients of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation following pulmonary vein isolation. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2025, 25, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saadeh, R.; Abu Jaber, B.; Alzuqaili, T.; Ghura, S.; Al-Ajlouny, T.; Saadeh, A.M. The relationship of atrial fibrillation with left atrial size in patients with essential hypertension. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pestrea, C.; Cicala, E.; Enache, R.; Rusu, M.; Gavrilescu, R.; Vaduva, A.; Risca, S.; Clapon, D.; Ortan, F. Mid-term comparison of new-onset AHRE between His bundle and left bundle branch area pacing in patients with AV block. J Arrhythm 2025, 41, e70009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Huang, B.; Fang, C.; Wang, P.; Tan, C.; Zheng, Y.; Wu, G.; Zheng, S.; Zhou, S. Study on the relationship between atrial high-rate episode and left atrial strain in patients with cardiac implantable electronic device. Quant Imaging Med Surg 2024, 14, 1844–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Nguyen, S.K.; Kieu, D.N.; Tran, P.L.U.; Nguyen, C.K.T.; Dang, T.Q.; Van Ly, C.; Van Hoang, S.; Nguyen, T.T. The incidence and risk factors of atrial high-rate episodes in patients with a dual-chamber pacemaker. J Arrhythm 2024, 40, 1158–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuel, J.; Batta, A.; Barwad, P.; Sharma, Y.P.; Panda, P.; Kaur, N.; Shrimanth, Y.S.; Pruthvi, C.R.; Sambyal, B. Incidence of atrial high rate episodes after dual-chamber permanent pacemaker implantation and its clinical predictors. Indian Heart J 2022, 74, 500–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, M.; Dejene, K.; Bedru, M.; Ahmed, M.; Markos, S. Predictors of complications and mortality among patients undergoing pacemaker implantation in resource-limited settings: a 10-year retrospective follow-up study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2024, 24, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markos, S.; Nasir, M.; Ahmed, M.; Abebe, S.; Amogne, M.A.; Tesfaye, D.; Mekonnen, T.S.; Getachew, Y.G. Assessment of Trend, Indication, Complications, and Outcomes of Pacemaker Implantation in Adult Patients at Tertiary Hospital of Ethiopia: Retrospective Follow Up Study. Int J Gen Med 2024, 17, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherbi, M.; Verdaguer, J.; Itier, R.; Barde, L.; Fournier, P.; Grunenwald, E.; Gaudard, P.; Rouviere, P.; Molina, A.; Ughetto, A.; et al. Prognostic value of NT-proBNP monitoring in patients with left ventricular assist devices. JHLT Open 2025, 10, 100387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Bian, X.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, R.; Song, C.; Yuan, S.; Wang, H.; Liu, W.; Gao, J.; Cui, X.; et al. Clinical implication of NT-proBNP to predict mortality in patients with acute type A aortic dissection: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2025, 15, e093757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, D.C.; Ciobanu, M.; Tint, D.; Nechita, A.C. Linking Heart Function to Prognosis: The Role of a Novel Echocardiographic Index and NT-proBNP in Acute Heart Failure. Medicina (Kaunas) 2025, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ianos, R.D.; Iancu, M.; Pop, C.; Lucaciu, R.L.; Hangan, A.C.; Rahaian, R.; Cozma, A.; Negrean, V.; Mercea, D.; Procopciuc, L.M. Predictive Value of NT-proBNP, FGF21, Galectin-3 and Copeptin in Advanced Heart Failure in Patients with Preserved and Mildly Reduced Ejection Fraction and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Medicina (Kaunas) 2024, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).