Introduction

The increasing demand for total hip arthroplasty (THA), especially among multimorbid elderly patients, presents a growing challenge for healthcare systems globally, with a significant risk of postoperative complications such as dislocation, infection, periprosthetic fractures, and bleeding [

1]. Revision surgeries are frequently necessitated by factors like infection, aseptic loosening, mechanical failure, and suboptimal restoration of femoral offset, which can destabilize hip biomechanics, reducing abductor function and leading to functional impairments [

2]. The revision procedure itself, especially when removing well-fixed femoral components, carries risks of substantial morbidity, including blood loss, infection, and prolonged operative time [

3,

4].

Over the past decades, the design of femoral stem tapers in THA has undergone substantial modification. Earlier generations of implants commonly utilized a 14/16 mm taper geometry, providing a robust connection between the stem and the femoral head. However, starting in the 1990s, implant manufacturers progressively adopted smaller taper designs such as 12/14 mm, primarily to facilitate the use of smaller femoral heads and thereby increase the achievable range of motion and reduce the risk of impingement [

5]. As described by Morlock et al. [

6], this downsizing also reduced the contact area and bending stiffness of the taper junction, which later contributed to increased susceptibility to fretting and corrosion phenomena. Importantly, this design evolution led to a compatibility gap in revision procedures, since most modern femoral heads are now produced exclusively for 12/14 mm tapers. Consequently, revision cases involving older but well-fixed 14/16 mm femoral stems pose a technical limitation, as standard replacement heads cannot be directly mounted on the existing taper.

Although the taper size is commonly described by nominal dimensions such as 12/14 or 14/16, it should be emphasized that these designations do not imply full interchangeability. As demonstrated by Müller et al. [

7], even tapers sharing the same nominal size may differ in angle, length, surface finish, and microgeometry, which can affect fixation mechanics and corrosion susceptibility

Because of these compatibility challenges, revision surgeries on older implants require dedicated solutions that allow head or liner exchange while retaining a stable femoral stem. One such option is the Bioball™ System (Merete Medical, Germany), a modular head–neck adapter that provides a versatile and less invasive alternative in revision THA. It enables orthopedic surgeons to preserve a well-fixed femoral component while revising only the acetabular or head element, thus minimizing surgical trauma and operative time. This titanium adapter system, available in various lengths (−3 mm to +21 mm, S to 5XL) and compatible with multiple Morse tapers (e.g., 12/14, 14/16, and V40), provides options for adjusting femoral offset, leg length, and anteversion intraoperatively. Additionally, it supports modular heads in cobalt-chromium and ceramic materials in diameters from 28 mm to 58 mm, making it versatile across different patient anatomies and prosthetic requirements.

Research indicates that the Bioball™ System can effectively restore femoral offset and enhance joint stability without necessitating femoral stem revision, offering an attractive solution particularly in elderly or ASA class III & IV patients with significant comorbidities [

1,

3,

8]. Notably, the Bioball™ System has demonstrated reliable long-term outcomes, especially for hip instability, through adaptations that protect the femoral neck-head junction and maintain functional biomechanics [

1,

8].

The aim of this study was to evaluate the clinical outcomes of revision total hip arthroplasty (RTHA) procedures limited to the exchange of the acetabular component or liner, while retaining a well-fixed femoral stem with a 14/16 taper using the Bioball™ system. This system, which, unlike most currently manufactured femoral heads, allows for direct attachment to a 14/16 taper. This approach was intended to minimize the extent of surgical intervention and preserve stable femoral fixation.

Materials and Methods

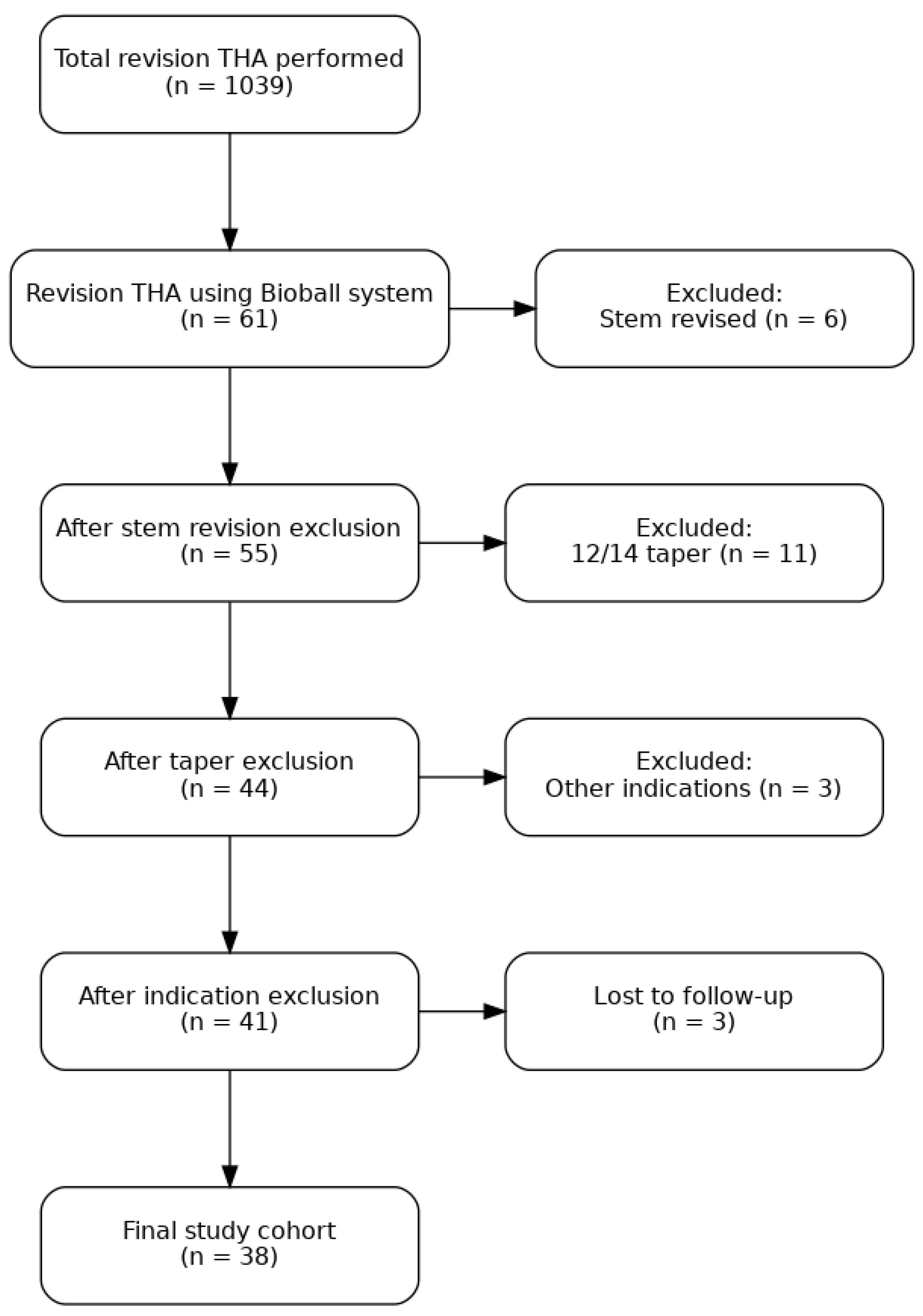

Since 1974, our center has been performing THA. Currently, we conduct over 450 primary hip arthroplasties and approximately 90 revision procedures annually. This retrospective study analyzed patient data from 2008 to 2020, encompassing a total of 1039 revision THA procedures. Among these, 61 revisions involved the use of the Bioball™ system, limited to exchange of the acetabular component or liner, with a stable femoral stem featuring a 14/16 taper. We excluded 6 cases in which the femoral stem was also revised due to loosening, 11 cases involving stems with a 12/14 taper, and 3 cases in which revision was performed for reasons other than aseptic loosening (septic or post-traumatic). An additional 3 patients were lost to follow-up. The final study cohort comprised 38 patients (

Figure 1).

Among the patients treated, 23 were women (60.3%) and 15 were men (39.7%). The right hip was operated on in 16 cases (42.1%) and the left hip in 22 cases (57.9%). The mean age of patients on the day of surgery was 64.81 years, ranging from 24 to 86 years (SD: 12.21 years, Me: 66.5 years). The average follow-up period after revision surgery was 3082 days (8.44 years), SD: 1041.5 days, Me: 2872 days.

In the study cohort, the Exception stem and L-Cup acetabular components (Biomet) were most commonly used; later, a press-fit Rimcup acetabular component (Biomet) was also utilized. Additional acetabular components included the Screwcup (BBraun/Aesculap). In 84% of cases, the implants were fixed to the bony bed using a cementless technique.

Radiological evaluation was integral to preoperative planning and follow-up assessments. For each case, anteroposterior and axial X-rays of the operated hip were obtained. Prosthesis positioning, acetabular and femoral component integration into bone tissue, and the presence and extent of heterotopic ossification were assessed. Acetabular component migration (horizontal, vertical, and angular) was evaluated using the DeLee and Charnley three-zone classification [

9]. A dual calibration marker ball system (KingMark™) was routinely used as a reference for determining the individual magnification factor. Digital templating was performed as described by Bono et al. [

10,

11], using TraumaCad™ software (BrainLab, Chicago, IL, USA). Femoral offset was defined as the distance from the center of femoral head rotation to a line bisecting the femur’s long axis. Stem integration was analyzed using the Gruen and Moreland classifications [

12,

13], with assessments of axial positioning in the femoral metaphysis, vertical migration, bone resorption, hypertrophy, bone density, and the presence of intraosseous and periosteal ossification across seven zones. Radiologic assessments were conducted by an independent researcher uninvolved in the surgeries (A.B., Ł.O.).

All procedures were performed under epidural anesthesia with an anterolateral approach, without greater trochanter osteotomy. In the cases where acetabulum was revised the acetabular component was placed within the Lewinnek safe zone [

14], with typical acetabular anteversion not exceeding 15° and stem antetorsion between 5–10°. In most cases, the acetabular component was located in the anatomical true acetabular region. Polyethylene or ceramic acetabular inserts were used, with options including symmetrical (P-M) or asymmetrical 10° (Munich/Plasmacup) designs or fully ceramic (Mittelmeier) components. Additionally, the femoral stem was intraoperatively assessed in every case, with meticulous exclusion of any signs of loosening of damage.

Standard antibiotic and anticoagulant prophylaxis, in line with current epidemiological guidelines, was provided perioperatively. Rehabilitation commenced on the first postoperative day, and following removal of the Redon drain, patients were mobilized and trained to bear weight according to pain tolerance. Further rehabilitative exercises were introduced over the following days.

After hospital discharge, follow-ups were scheduled at three, six, and twelve months, and annually thereafter. Clinical outcomes were assessed by the same surgeon at each follow-up, using the Merle d’Aubigné and Postel classification, modified by Charnley (Modified MAP) [

15], to score pain, gait, and passive range of hip motion on a 1 to 6 scale per domain (maximum total score of 18). Pain was also measured using a ten-point Visual Analog Scale (VAS) [

16], with “0” indicating no pain and “10” indicating the worst possible pain. Implant survival probability was planned to be analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier estimator [

17], however we have experienced no components loosening after the revision surgery. Patients were followed from the date of revision until death or outcome, whichever occurred first. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Lodz (NR RNN/195/24/KE, approval date on 10 September 2024).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with IBM Statistics for MacOS IBM SPSS Statistics for MacOS, Version 29 (IBM Corp., Armonk, New York, United States). Nominal data between unpaired observations were compared using the Chi-square test, while McNemar’s test was applied for paired observations. Normality was assessed with the Shapiro-Wilk test. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Continuous variables were analyzed based on measurement type: unpaired measurements were evaluated with an independent t-test if normality was met; otherwise, the Mann-Whitney U test was used. A paired t-test was employed for paired measurements when normality was satisfied. Mean comparisons across more than two groups involved one-way ANOVA if normal distribution was present; if not, the Kruskal-Wallis test was used. The aim of the analysis was to investigate the association between patient gender and the extent of the procedure performed (i.e., liner-only replacement vs. replacement involving both the acetabular cup and liner). Additionally, it examined whether specific prosthesis head sizes and offset values were more frequently used for different procedure types.

Results

The mean age of patients was 64.81 years (SD: 12.21 years ,Me: 66.5 years). The study group included 23 women and 15 men. The primary cause for the initial THA was secondary osteoarthritis due to idiopathic osteoarthritis in 21 patients (55.3%), developmental dysplasia of the hip in 13 patients (34.2%), and other causes in 4 patients (10.5%). The mean follow-up duration was 3082 days (Me: 2872 days, SD: 1041.5 days). Four patients passed away due to unrelated causes during the follow-up period, and their follow-up time was therefore excluded from the analysis. The mean Body Mass Index (BMI) of the patients was 27.85 (SD: 3.48 , Me: 27.2). Among the study population, 6 out of the 38 patients had a history of primary prosthesis dislocation. All prior dislocation episodes, following closed reduction, did not require reoperation. The primary reason for revision surgery in the study group was acetabular cup loosening (n=29, 76.31%), while only the liner was replaced in 9 patients (23.69%). No gender impact was observed (p=0.310).

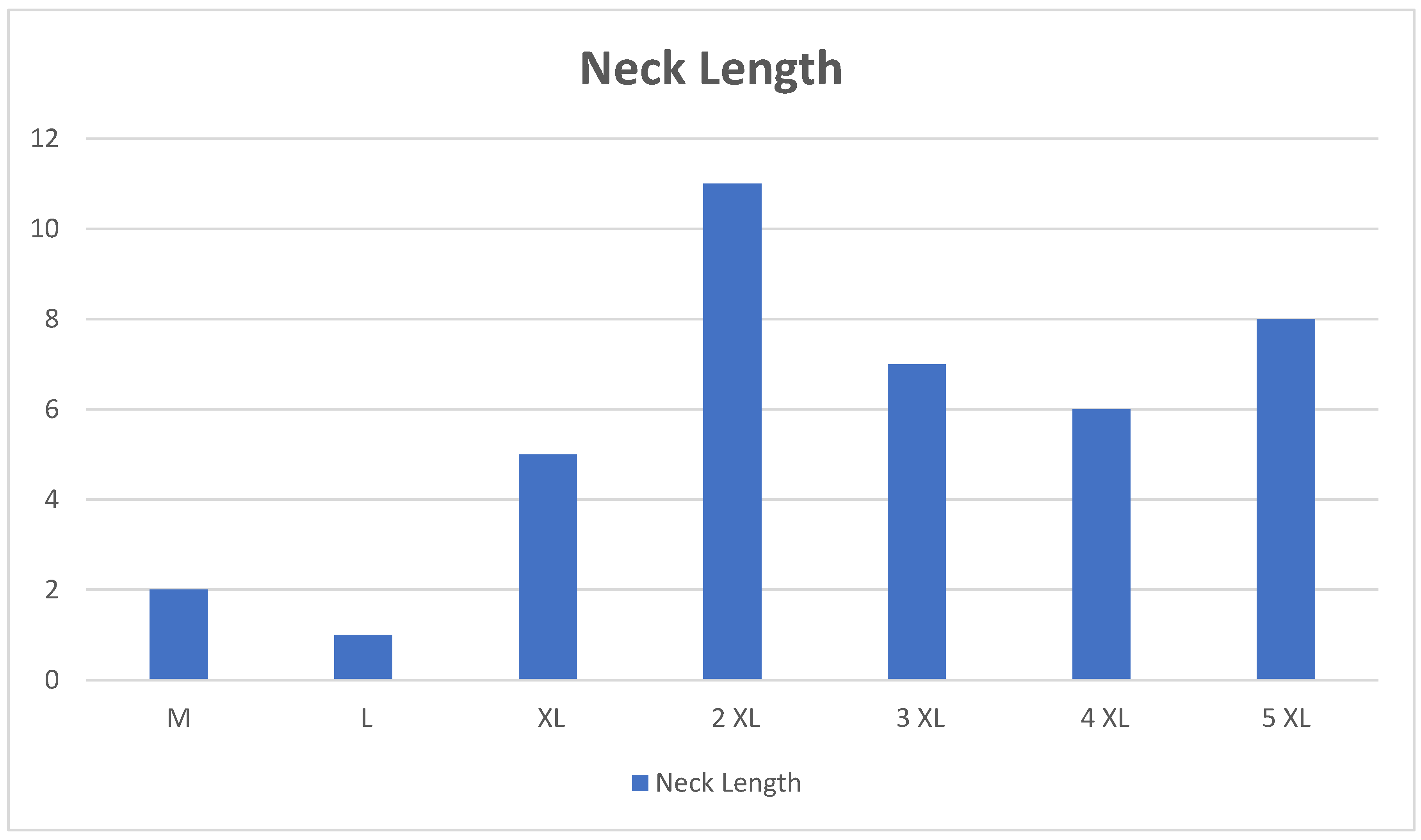

As regards the implants’ characteristics, the most used neck length was 2XL (+ 10.5 mm) (28.95% of cases (n = 11)), followed by 5 XL (+ 21 mm) (21.05% of cases (n=8)), 3XL (+ 14 mm) (18.42% of cases (n = 7)), 4XL (+17.5 mm) (15.79% of cases (n=6)), XL ( + 7 mm) (7.90% of cases (n=3)), M (+ 0 mm) (5.26% of cases (n=2)), L (+ 3,5 mm) (2.63% of cases (n=1)), summarized in

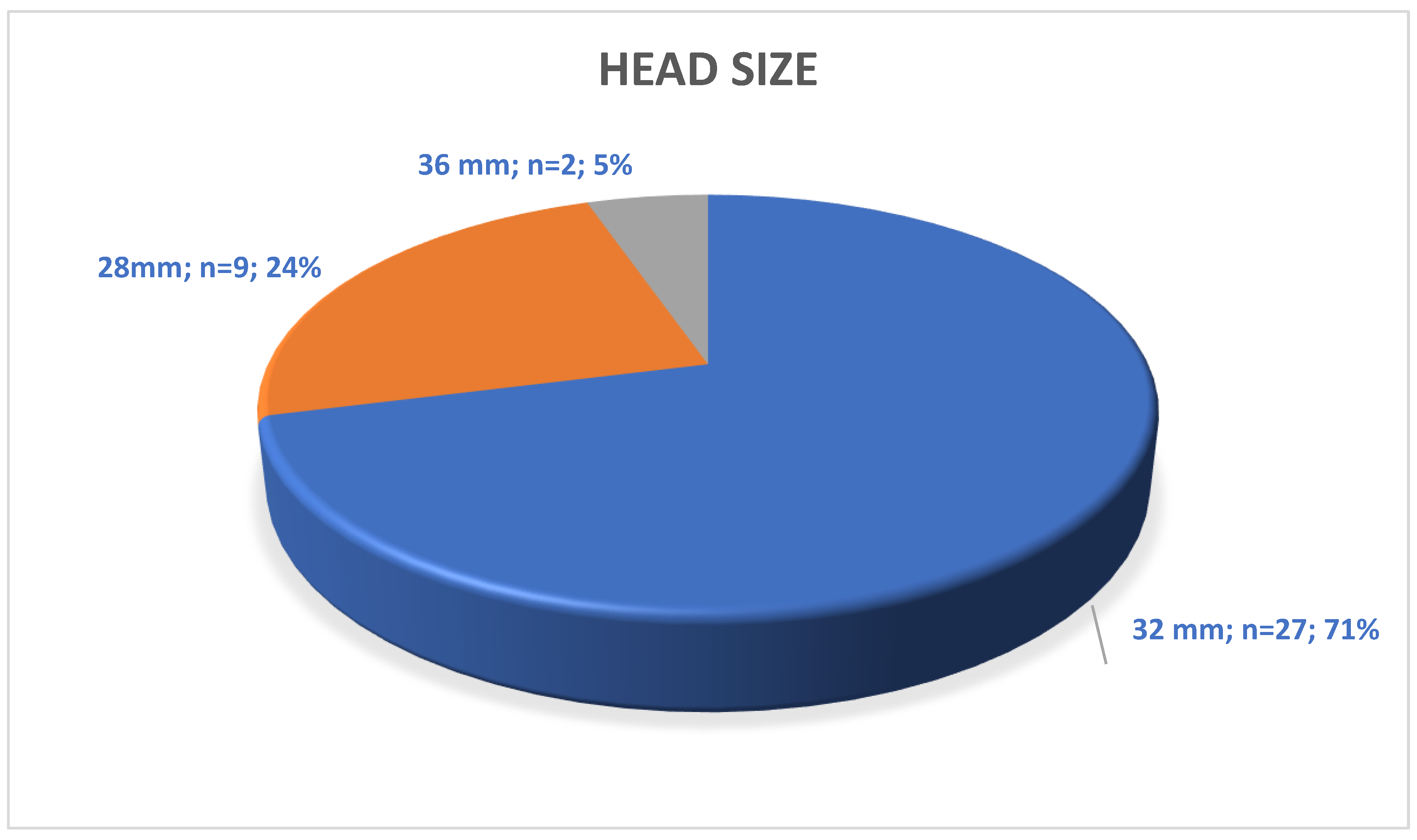

Figure 2. The most frequently used head sizes were 32 mm (71.05% of patients (n = 27)) and 28 mm (23.68% of patients (n = 9)), size 36 mm was used only in 2 cases (5.26% of cases), summarized in

Figure 3. The size was not statistically significant between the procedure type (p=0.060). The 7.5° offset adapter was used in 57.90% (n = 22) of patients. The offset values were not affected by the procedure type (p=0.480).

Preoperatively, as expected, all patients demonstrated poor clinical and radiological outcomes. At a mean follow-up of 8.44 years postoperatively, the final results, assessed using the modified Merle d’Aubigné and Postel (MAP) classification[

15], were as follows: an excellent outcome was not observed in any case (0%), good outcome in 14 cases (36.84%), and fair outcome in 24 cases (63.16%). A poor outcome was not recorded in any case (0%). Above mentioned details are summarized in

Table 1. The mean improvement in the modified MAP scale was 5.7 points, which was statistically significant (p < 0.05). The Modified MAP score was distributed the same between the different procedure types (p=0.404).

Subjective patient-reported outcomes postoperatively were notably better than the objective results obtained using the modified MAP classification. The greatest improvements were seen in pain relief and range of motion, contributing to enhanced hip function and overall patient satisfaction. As anticipated, the best outcomes were obtain in the group where only the liner was exchanged. However, it is important to note that an “excellent outcome” in the modified MAP classification represents a result comparable to a healthy native hip joint. Importantly, no cases of thigh pain which is sometimes reported following uncemented hip arthroplasty were recorded in this study.

Using the Visual Analog Scale (VAS)[

18], preoperative pain levels averaged 7.4 points, while postoperatively, pain levels improved to 2.6 points. This pain reduction was statistically significant (p < 0.05).

During the follow-up period following revision hip arthroplasty using the Bioball™ System, no dislocation episodes of the prosthesis were observed. Furthermore, until the final day of the follow-up period i.e. June 30, 2025, no signs of prosthesis loosening were noted in any of the patients included in the study.

Discussion

A unique and clinically significant aspect of our study is that all revision procedures were performed in patients with well-fixed femoral stems featuring a 14/16 taper. This taper geometry, once widely used in early generations of femoral stems, has been largely replaced by smaller 12/14 designs in modern arthroplasty systems. Consequently, surgeons are often confronted with a compatibility gap, as currently manufactured modular heads are no longer produced for 14/16 tapers. In such scenarios, a standard head exchange is technically impossible, often leading to unnecessary removal of a well-fixed femoral stem. The Bioball™ System provides an effective solution to this problem by offering an adapter-based interface that allows secure attachment of new modular heads to legacy 14/16 tapers. This approach enables true partial revision, limited to the acetabular component or head exchange, while preserving stable femoral fixation, thereby reducing operative time, intraoperative blood loss, and bone stock loss associated with stem removal. Furthermore, the adapter’s surface finish ensure mechanical stability while minimizing micromotion and corrosion risk at the taper junction. In our cohort, the exclusive use of 14/16 tapers confirms the Bioball™ System’s reliability and relevance as a dedicated tool for addressing a growing clinical need in revision arthroplasty of older implant generations.

Another crucial aspect of achieving optimal function following THA is restoration of native femoral offset. While the importance of restoring femoral offset is well-established, the precise impact on functional outcomes remains a topic of ongoing debate. In recent years a lot has been debated about influence of femoral offset on strength, range of motion but also on pain sensation and quality of life [

19,

20,

21,

22]. Cassidy et al. [

23] have shown that a significant decrease in femoral offset, particularly a reduction greater than 5 mm or 15%, can result in hip abductor weakness and reduced joint function. Similar findings have been reported by Bullen et al. [

24], who found that a reduction greater than 20 mm in offset typically led to worse pain and motion scores. In our series, all patients were reoperated due to a cup loosening or liner wear which also decreased the femoral offset. After revision surgery with a head-neck adapter, all of the 38 examined patients experienced significant improvements in the Modified MAP scores [

15] and we noted no dislocations of the endoprosthesis, demonstrating the potential benefit of restoring femoral offset to improve functional outcomes and address abductor weakness.

The head-neck adapter has become an essential tool in revision surgeries, especially in cases where only partial hip revision is required. By retaining the original femoral stem and replacing the taper surface on the damaged cone, the adapter minimizes the need for more extensive revision procedures. Moreover, the addition of a 7.5° offset via the head-neck adapter can significantly improve hip stability, particularly in cases of recurrent dislocation, as highlighted by Kock et al. [

1]. The utility of the adapter in primary THA, particularly in patients with a high risk of dislocation, has also been reported by Kock et al. [

1]. In our series, we utilized the 7 different head-neck adapters in (from M to 5XL) to increase femoral neck length and also in 57,90% of cases special taper was used to adjust the center of rotation with a 7.5° offset. These applications demonstrate the versatility of the Bioball™ System in both complicated revision procedures.

Hoberg et al [

25]. examined retrospectively 95 consecutive patients revised with the Bioball adaptor system. 13 patients were lost to follow-up and a total of 82 patients were reviewed. Recurrent dislocations, acetabular component loosening and wear of the acetabular liner were indicated to be the most common indications for revision in the examined group. In their study satisfaction was assessed in a ternary fashion (i.e. whether satisfied, partly satisfied or not satisfied). They have noted mostly excellent results - approximately 90% of patients reported satisfaction after the revision surgery, whereas only 1% of patients in their cohort reported no satisfaction. Moreover the survival rate of the Bioball™ System accounted for 92.8% after 8.17 years. Interestingly they have reported 100% of survival rate at 2-years follow up. Similar results were obtained by Dabis et al [

26], who have reviewed the outcomes of 32 hip revision arthroplasty procedures using the Bioball™ System. During a minimum follow-up period of two years, two cases of recurrent dislocations of the artificial joint were reported following revision surgery, as well as one case of instability without dislocation of the prosthesis. In our study we have noted 100% survival rate after 8.44 years of follow-up and only good (36.84%) and fair (63.16%) results at the latest appointment.

Similar results to ours were obtained by Jack et al. [

27], who studied the outcomes of ceramic-on-ceramic articulation in isolated acetabular component revision procedures of THA. In their study group, a total of 165 revision procedures were performed, with the Bioball™ System used in 75 cases. During a mean follow-up period of 8.3 years, they achieved a biofunctional rate of the acetabular component at 96.6%. An important challenge in revision hip arthroplasty is joint instability, which can result in recurrent dislocations. Woelfle et al. [

28] have analyzed the outcomes of 44 hip revision surgeries using the Bioball™ System. Over a four-year follow-up period, only three cases of recurrent dislocation of the artificial joint were reported. However, due to the advanced age of the patients and the coexistence of other chronic medical conditions, the average clinical outcome (HHS = 54) was deemed relatively poor. In their conclusions, the authors emphasized the positive role of the Bioball™ System in reducing postoperative leg length discrepancies and highlighted its beneficial impact on restoring proper biomechanical conditions of the operated hip joint (offset). In our study, despite a high rate of dislocations of the primary prosthesis (15.79%), no cases of prosthetic dislocation were observed following revision surgery throughout the entire follow-up period. Interestingly, the MAP score in patients with episodes of primary prosthesis dislocation, after revision surgery was nearly identical to that of patients with no episodes of prosthesis dislocation (14.19 vs. 14.39, respectively). The comparison yielded a p-value of 0.574, indicating no statistically significant differences between these groups.

Pautasso et al. [

29] have performed comprehensive narrative review analyzing the outcomes of hip revision arthroplasty using the BioBall® adapter in various clinical scenarios. It included data from multiple studies and the timeframe was limited between 01.01.2000 and 01.12.2022, with groups ranging from 32 to 194 patients. Follow-up periods varied, and dislocation rates ranged from 5.2% to 15%. Patient satisfaction was mostly high, with studies reporting Harris Hip Scores averaging 80.9 and satisfaction rates of up to 89%. Complications were rare, and the ones reported were fatigue fractures of the neck adapter, third body wear, stem neck fracture, ceramic head fracture and disassembly of the system components. None of the described complications have occurred in our study.

Patients with hip dysplasia, characterized by reduced femoral offset, present a unique challenge during THA [

30]. If not carefully managed, correction of femoral offset in these patients can lead to an excessively increased offset. Cassidy et al. [

23] reported that 22.6% of patients with a decreased offset preoperatively still had residual offset reduction postoperatively despite the use of extended offset stems. In our study, thirteen patients with congenital hip abnormalities presented with a diminished offset were included in the study. Despite anatomical abnormalities and difficulties the revision surgeries were successfully addressed with the Bioball™ System, reinforcing the adapter’s role in precise offset restoration, particularly in complex cases.

Our study, based on a retrospective analysis of 38 adult patients with a mean observation time of 3082 days, provides valuable insight into the effectiveness of the Bioball™ System in revision THA. Notably, we observed no dislocations or loosening of prosthetic components after the revision procedures, which further supports the reliability and stability of the Bioball™ System. However, there were some limitations inherent to the retrospective nature of our study, including potential biases and a lack of control over confounding variables. Additionally, the management of periarticular soft tissues, such as gluteus medius tears, could have contributed to the observed improvements in functional outcomes. Given the small sample size of our study, the results may not be broadly generalizable, and further prospective research with larger cohorts is necessary to confirm the long-term benefits of femoral offset restoration using the Bioball™ System.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the use of the Bioball™ System allows for achieving hip joint stability without the need to remove a stable femoral component. This substantially reduces the extent of the procedure, blood loss, and complications that may arise during stem removal. Importantly, it enables limitation of surgical invasiveness in cases where the femoral stem remains stable but the acetabular component or insert is loosened, provided that a 14/16 taper is present - a scenario that would not be feasible with the currently prevailing 12/14 head standard. Moreover, the Bioball™ System is a promising solution for addressing femoral offset restoration in both revision and primary THA. Our study demonstrates its effectiveness in improving clinical outcomes, particularly in patients with decreased femoral offset or those at risk of recurrent dislocation. Further research is required to validate these findings and refine the criteria for its use in diverse clinical scenarios.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.D. and A.B. (Andrzej Borowski); Methodology, M.D., B.G. and A.B. (Andrzej Borowski); Formal analysis, B.G. and G.T.; Investigation, M.D. and K.R.; Resources, M.D. and B.G.; Writing—original draft, M.D., B.G. and K.R.; Writing—review & editing, M.D., B.G., Ł.O., A.B. (Adam Borowski), G.T. and A.B. (Andrzej Borowski); Supervision, M.D. and A.B. (Andrzej Borowski); Project administration, B.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Lodz (NR RNN/195/24/KE, approval date on 10 September 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

List of Abbreviations

RTHA – revision total hip arthroplasty; THA- total hip arthroplasty; VAS - Visual Analog Scale, BMI - The Body Mass Index, MAP - Merle d’Aubigné and Postel, modified by Charnley

References

- Kock, H.J.; Cho, C.; Buhl, K.; Hillmeier, J.; Huber, F.X. Long-Term Outcome after Revision of Hip Arthroplasty with the BioBall® Adapter System in Multimorbid Patients. J Orthop Translat 2019, 22, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimeno, C.; Fernández-Valencia, J.Á.; Alías, A.; Serra, A.; Postnikov, Y.; Combalia, A.; Muñoz-Mahamud, E. Contribution of the BioballTM Head–Neck Adapter to the Restoration of Femoral Offset in Hip Revision Arthroplasty with Retention of a Well-Fixed Cup and Stem. Int Orthop 2023, 47, 2245–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaishya, R.; Sharma, M.; Chaudhary, R.R. Bioball Universal Modular Neck Adapter as a Salvage for Failed Revision Total Hip Arthroplasty. Indian J Orthop 2013, 47, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garabadi, M.; Akhtar, M.; Blow, J.; Pawar, R.; Rowsell, M.; Antapur, P. Clinical Outcome of Bioball Universal Adapter in Revision Hip Arthroplasty. J Orthop 2023, 38, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrack, R.L.; Butler, R.A.; Laster, D.R.; Andrews, P. Stem Design and Dislocation after Revision Total Hip Arthroplasty: Clinical Results and Computer Modeling. Journal of Arthroplasty 2001, 16, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morlock, M.M.; Hube, R.; Wassilew, G.; Prange, F.; Huber, G.; Perka, C. Taper Corrosion: A Complication of Total Hip Arthroplasty. EFORT Open Rev 2020, 5, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueller, U.; Braun, S.; Schroeder, S.; Sonntag, R.; Kretzer, J.P. Same Same but Different? 12/14 Stem and Head Tapers in Total Hip Arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2017, 32, 3191–3199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novoa, C.D.; Citak, M.; Zahar, A.; López, R.E.; Gehrke, T.; Rodrigo, J.L. The Merete BioBall System in Hip Revision Surgery: A Systematic Review. Orthopaedics & Traumatology: Surgery & Research 2018, 104, 1171–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLee, J.; Charnley, J. Radiological Demarcation of Cemented Sockets in Total Hip Replacement. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1976, 121, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bono, J. V. Digital Templating in Total Hip Arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2004, 86-A Suppl 2, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamczyk, A.; Laboudie, P.; Nessek, H.; Kim, P.R.; Gofton, W.T.; Feibel, R.; Grammatopoulos, G. Accuracy of Digital Templating in Uncemented Primary Total Hip Arthroplasty: Which Factors Are Associated with Accuracy of Preoperative Planning? https://doi.org/10.1177/11207000221082026 2022, 33, 434–441. [CrossRef]

- Gruen, T.; McNeice G; Amstutz, H. “Modes of Failure” of Cemented Stem-Type Femoral Components: A Radiographic Analysis of Loosening. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1979, 141, 17–27. [CrossRef]

- Moreland, J.R.; Moreno, M.A. Cementless Femoral Revision Arthroplasty of the Hip: Minimum 5 Years Followup. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2001, 393, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewinnek, G.; Lewis, J.L.; Tarr, R.; Compere, C.L.; Zimmerman, J.R. Dislocations after Total Hip-Replacement Arthroplasties. The journal of bone & joint sugery 1978, 60, 217–220. [Google Scholar]

- D’Aubigné, R.M.; Postel, M.; Brand, R.A. The Classic: Functional Results of Hip Arthroplasty with Acrylic Prosthesis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2009, 467, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Costa, B.R.; Saadat, P.; Basciani, R.M.; Agarwal, A.; Johnston, B.C.; Jüni, P. Visual Analogue Scale Has Higher Assay Sensitivity than WOMAC Pain in Detecting Between-Group Differences in Treatment Effects: A Meta-Epidemiological Study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2021, 29, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, E.L.; Meier, P. Nonparametric Estimation from Incomplete Observations. J Am Stat Assoc 1958, 53, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danoff, J.R.; Goel, R.; Sutton, R.; Maltenfort, M.G.; Austin, M.S. How Much Pain Is Significant? Defining the Minimal Clinically Important Difference for the Visual Analog Scale for Pain After Total Joint Arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2018, 33, S71–S75.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapira, J.; Chen, S.L.; Rosinsky, P.J.; Maldonado, D.R.; Meghpara, M.; Lall, A.C.; Domb, B.G. The Effect of Postoperative Femoral Offset on Outcomes after Hip Arthroplasty: A Systematic Review. J Orthop 2020, 22, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, H.; Maezawa, K.; Gomi, M.; Kajihara, H.; Hayashi, A.; Maruyama, Y.; Nozawa, M.; Kaneko, K. Effect of Femoral Offset and Limb Length Discrepancy on Hip Joint Muscle Strength and Gait Trajectory after Total Hip Arthroplasty. Gait Posture 2020, 77, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, S.S.; Mukka, S.S.; Crnalic, S.; Wretenberg, P.; Sayed-Noor, A.S. Association between Changes in Global Femoral Offset after Total Hip Arthroplasty and Function, Quality of Life, and Abductor Muscle Strength. Acta Orthop 2016, 87, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husby, V.S.; Bjørgen, S.; Hoff, J.; Helgerud, J.; Benum, P.; Husby, O.S. Unilateral vs. Bilateral Total Hip Arthroplasty - the Influence of Medial Femoral Head Offset and Effects on Strength and Aerobic Endurance Capacity. Hip Int 2010, 20, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, K.A.; Noticewala, M.S.; Macaulay, W.; Lee, J.H.; Geller, J.A. Effect of Femoral Offset on Pain and Function after Total Hip Arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2012, 27, 1863–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullen, M.E.; Babazadeh, S.; van Bavel, D.; McKenzie, D.P.; Dowsey, M.M.; Choong, P.F. Reduction in Offset Is Associated With Worse Functional Outcomes Following Total Hip Arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2023, 38, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoberg, M.; Konrads, C.; Huber, S.; Reppenhagen, S.; Walcher, M.; Steinert, A.; Barthel, T.; Rudert, M. Outcome of a Modular Head-Neck Adapter System in Revision Hip Arthroplasty. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2015, 135, 1469–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dabis, J.; Hutt, J.R.; Ward, D.; Field, R.; Mitchell, P.A.; Sandiford, N.A. Clinical Outcomes and Dislocation Rates after Hip Reconstruction Using the Bioball System. Hip Int 2020, 30, 609–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, C.M.; Molloy, D.O.; Walter, W.L.; Zicat, B.A.; Walter, W.K. The Use of Ceramic-on-Ceramic Bearings in Isolated Revision of the Acetabular Component. Bone Joint J 2013, 95-B, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woelfle, J. V.; Fraitzl, C.R.; Reichel, H.; Wernerus, D. Significantly Reduced Leg Length Discrepancy and Increased Femoral Offset by Application of a Head-Neck Adapter in Revision Total Hip Arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2014, 29, 1301–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pautasso, A.; Bardellini, G.; Stissi, P.; D’Angelo, F. Usefulness of Modular Neck Adapter in Partial Hip Revision. Ann Jt 2023, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drobniewski, M.; Gonera, B.; Olewnik, Ł.; Borowski, A.; Ruzik, K.; Triantafyllou, G.; Borowski, A. Challenges and Long-Term Outcomes of Cementless Total Hip Arthroplasty in Patients Under 30: A 24-Year Follow-Up Study with a Minimum 8-Year Follow-Up, Focused on Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2024, Vol. 13, Page 6591 2024, 13, 6591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).