1. Introduction

Anemia is defined as the number of circulating red blood cells, the concentration of hemoglobin, or the hematocrit level falling below the normal range, resulting in reduced oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood¹. This leads to symptoms such as fatigue, weakness, and shortness of breath [

1]. It affects women of reproductive age at a disproportionate rate, especially in low and middle-income regions. Women aged 15-49 years are considered anemic if their hemoglobin levels are below 120 g/L when non-pregnant or lactating, and below 110g/L when pregnant [

2].

According to the 2019 Global Burden of Disease Study, approximately 30% of women of reproductive age worldwide were affected by anemia in 2019, highlighting its widespread global impact [

3]. By 2030, 18 million more women and girls in South Asia could suffer from anemia, therefore causing it to remain a large public health concern among women in South Asia [

4,

5].

Multiple factors contribute to the high burden of anemia in the South Asian region, including limited access to healthcare, nutritional deficiencies, poor sanitation and hygiene, and socioeconomic disparities [

6]. The infectious and non-infectious causes of anemia, such as malaria, other parasitic or waterborne diseases, and dehydration, can lead to reduced plasma volume, hemoconcentration, and red blood cell damage during severe heat stress [

7]. While these factors are the focus of public health strategies, emerging evidence suggests that ambient temperature may also play an important role in anemia risk [

8]. Elevated ambient temperatures can increase dehydration risk, which reduces plasma volume and impairs oxygen transport in the body [

9]. Elevated ambient temperatures also impair nutritional status by decreasing appetite, altering dietary intake, and increasing metabolic demands that deplete key micronutrients such as iron, folate, and vitamin B₁₂ [

9]. The first and second trimesters of pregnancy serve as susceptible exposure windows, during which elevated ambient temperatures significantly increase the risk of anemia in pregnancy [

10]. Given its high anemia burden and climatic vulnerability, South Asia is a key region for exploring the role of ambient temperature in shaping anemia outcomes. This makes the South Asian region a critical setting to examine environmental determinants such as ambient temperature on anemia.

This study investigates whether maximum temperatures are significantly associated with anemia among middle-aged women of reproductive age in South Asia. Previous research has connected temperature to infectious diseases and its correlation with anemia; however, no large-scale study in South Asia has directly examined the relationship between temperature and maternal hemoglobin levels. Although several indirect pathways have been proposed, no direct biological mechanism has yet been established linking ambient temperature to maternal anemia. We hypothesize that a rise in temperatures will have an effect on maternal hemoglobin levels across different regions of South Asia. Average surface temperatures in South Asia have been increasing at approximately 0.5°C per decade, indicating a clear and ongoing warming trend in the region. Understanding how climatic conditions influence maternal health can inform targeted public health strategies and strengthen resilience against the evolving threats of global climate change.

2. Methods

This population-based ecological cross-sectional study used South Asian data from 2000-2022, focusing on women of reproductive age (15-49 years) across eight countries: Afghanistan (AFG), Bangladesh (BGD), Bhutan (BTN), India (IND), Maldives (MDV), Nepal (NPL), Pakistan (PAK), and Sri Lanka (LKA). National-level data from each country were combined to create a regional dataset for analysis. Further division of the dataset was made into three regions: (1) western South Asia (AFG and PAK); (2) central South Asia (IND, MDV, NPL, LKA); (3) eastern South Asia (BGD and BTN). Maternal anemia prevalence data were retrieved from the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Global Health Observatory and cross-verified with Demographic and Health Surveys and national health reports from corresponding years.

Annual mean maximum surface air temperatures (in °C) for each country were obtained from the World Bank Climate Change Knowledge Portal, which provides national-level long-term climate monitoring data. Furthermore, other known risk factors for country-specific reproductive anemia were also obtained from ‘Our World in Data’ for 2000-2022. The variables include annual fertility rate per woman giving birth, percentage of population residing in rural regions, population BMI ≥25 kg/m2, cereal agriculture yield, and the trend.

To address serial autocorrelation, we used negative binomial regression with autocorrelated residuals of order one, adjusting for covariates. Anemia prevalence rates were log transformed, allowing the estimated parameters to be interpreted as rate ratios (RR).

3. Results

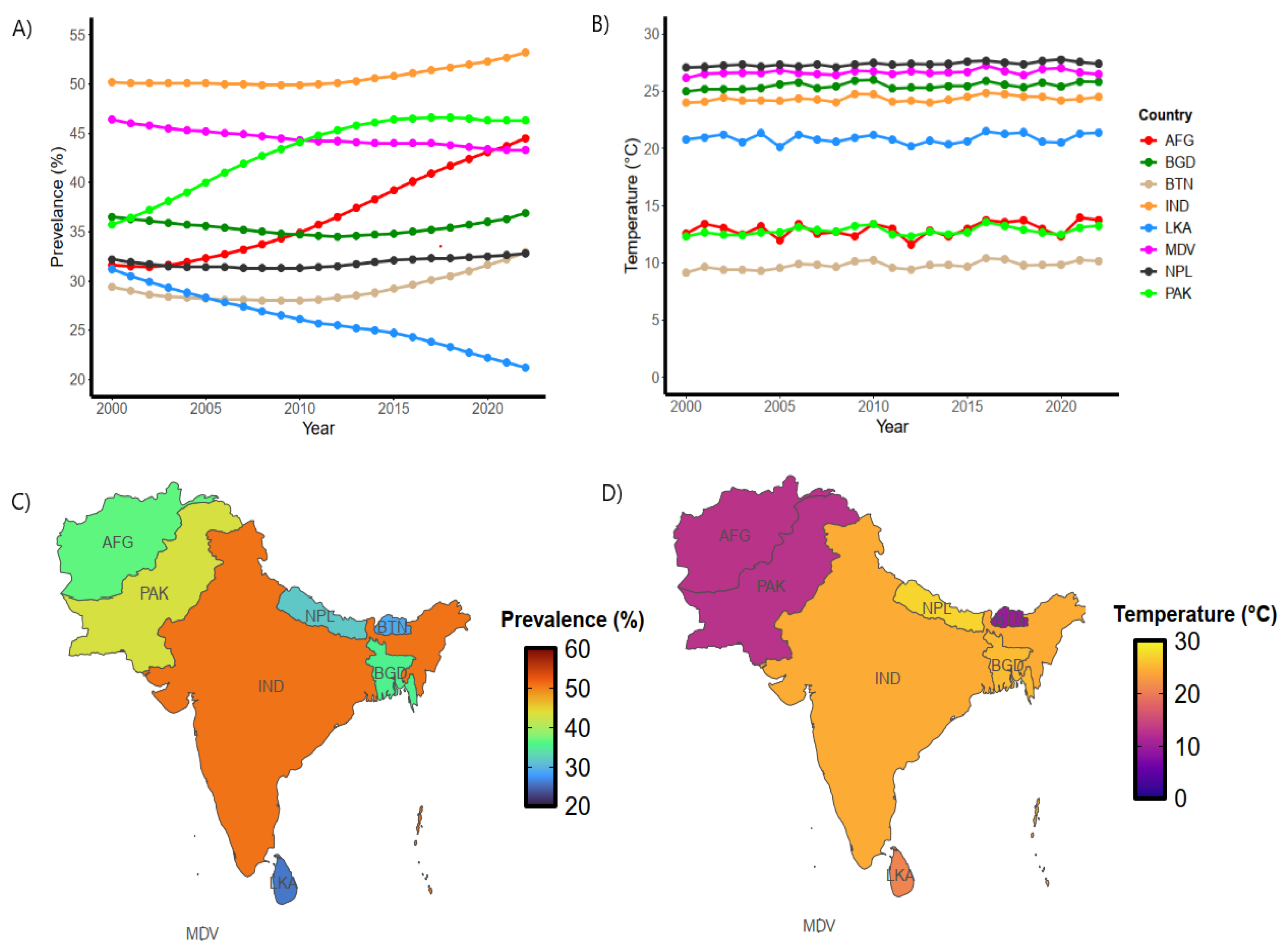

Figure 1A depicts country-specific anemia trends among reproductive women, with large variations observed in South Asia.

Figure 1B shows country-specific temperature trends in South Asian nations.

Figure 1C and 1D show geographical variations in anemia and temperatures across South Asia. By the year 2022, India had the highest prevalence of anemia among reproductive women across all other South Asian nations, whereas Sri Lanka had the lowest. The coolest annual temperatures were noted in western South Asia (i.e., Afghanistan and Pakistan), whereas the highest temperatures were observed in central South Asia. Specifically, the highest mean annual temperatures were recorded in Nepal, averaging approximately 27°C, while Bhutan exhibited the lowest annual temperatures, averaging approximately 9.5°C. Bhutan and Nepal differed in anemia prevalence despite having cooler climates, with Bhutan showing relatively low rates and Nepal exhibiting moderate levels.

The highest maternal anemia prevalence was found in India (~51%) and Pakistan (~46%), whereas Sri Lanka (~24%) and Bhutan (~30%) recorded the lowest prevalence (Figure 4). Annual temperature trends remained stable over the study period, with only minor year-to-year variation. Periods of higher mean annual temperatures often coincided with increased anemia prevalence, especially in India, Pakistan, and the Maldives.

A statistically significant but weak positive association was observed between maternal anemia prevalence and mean annual ambient temperature across South Asian countries from 2010 to 2022. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was 0.24 (P=0.013), indicating the linear nature of the relationship.

Table 1 presents the region-specific adjusted regression model, highlighting the risks associated with the relationship between anemia and temperatures from 2000 to 2022. For each 1℃ increment in annual mean temperatures, Eastern South Asia (n=2 nations) was associated with a significant 1% (P=0.005) increased risk of anemia among reproductive women. Similar effects were noted in Central (n=4 nations) South Asia, where the risk of anemia increased by 0.8% (P=0.002) per temperature increment. There was no statistically significant relationship noted in Western South Asia (Afghanistan/Pakistan).

These findings indicate that higher ambient temperatures in South Asia are significantly correlated with greater maternal anemia prevalence. As regional temperatures are expected to rise due to climate change, these results highlight the need to integrate such knowledge into targeted public health and maternal healthcare strategies.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrates a modest but statistically significant association between temperatures and maternal anemia prevalence in South Asia over the past two decades. Although temperature may contribute to anemia risk, the limited relationship suggests that maternal anemia is influenced by a combination of factors such as environmental, biological, and social determinants. A recent case-control study found that for each 1 °C increase in mean temperature, especially in the first and second trimesters, the odds of developing anemia in pregnancy rise [

12]. These results align with existing studies that emphasize the negative effects of heat exposure on immune functions and overall health, especially among vulnerable populations such as pregnant women [

13]. The increased risk is plausible due to various factors linked to heat exposure, such as reduced food intake affecting nutritional status, and stress on maternal physiology during pregnancy, which can all cause or exacerbate anemia [

14]. Despite these links, cross-country variation in our dataset highlights the complexity of this relationship. For instance, Bhutan exhibited the lowest average surface air temperature across the study period and concurrently recorded the second lowest maternal anemia prevalence. Moreover, countries like Sri Lanka, with higher temperatures, consistently showed low anemia rates, suggesting that other significant factors that have not been addressed should be considered (

Figure 1). Such differences suggest that nutritional status, healthcare access, socioeconomic conditions, and cultural practices are likely to play a larger role than climate alone. Anemia, although perceived as a disease, is a symptom of low hemoglobin that can have various factors contributing to its exacerbation. Although iron deficiency is a common cause, it does not necessarily constitute anemia. However, pregnancy increases the likelihood of anemia due to the fetus’s complete reliance on maternal iron and nutrient stores, which can deplete the mother’s reserves, especially when dietary intake is inadequate [

24]. Some individuals suffer from genetic conditions like thalassemia or sickle cell disease that can cause anemia independent of surface air temperature [

15].

Rising temperatures due to global warming significantly impact human immunity and the overall adaptive immune system [

16]. They can also further increase vulnerability to infections and worsen the symptoms of existing diseases [

17]. The risk of heat exhaustion and heatstroke increases when the body cannot control temperature or release excess heat [

18]. This also affects the heart and kidneys, worsening chronic conditions such as cardiovascular, respiratory, metabolic, and mental health disorders [

18]. The detrimental risks of high temperatures and anemia emphasize the need for climate-health strategies that prioritize nutrition, disease prevention, and adaptable healthcare delivery systems.

Beyond the direct physiological stress imposed by ambient temperatures in South Asia, several mechanisms may explain how heat has an association with increased anemia risk among women of reproductive age. Exposure to high temperatures can raise hepcidin levels, a hormone responsible for regulating iron metabolism, thereby limiting iron absorption and transport even when dietary intake is sufficient [

20]. Sweat induced losses of minerals such as iron and zinc may further deplete essential micronutrients, especially for women engaged in manual or outdoor labor [

21]. Additionally, heat-related appetite suppression can result in reduced caloric and micronutrient intake, which is particularly concerning in regions such as South Asian with existing food insecurity [

23]. High altitudes, on the other hand, may offer a partial physiological buffer, as red blood cell production is stimulated under chronic hypoxic conditions, possibly explaining why countries like Bhutan with lower temperatures and higher elevation showed lower anemia prevalence [

22]. Furthermore, heat and air pollution are often intertwined, and fine dust particle exposure has been shown to trigger inflammation, which may interfere with iron homeostasis [

30].

Additionally, systematic and environmental factors should be considered to fully understand the complex pathways linking climate exposure to maternal anemia. While this study focused on the role of heat, cold temperatures may also impact public health through immune suppression and increased infection risk. Increasing susceptibility to infections such as respiratory illness can indirectly contribute to anemia by further reducing red blood cell count or iron absorption [

28]. Another critical factor to consider alongside temperature is climate-related food insecurity. Rising temperatures and declining crop yields reduce the micronutrient density of staple foods, such as rice and wheat, that form the bulk of many South Asian diets [

29]. Warming and erratic rainfall are not only reducing crop quantity but also lowering levels of iron, zinc, and folate in key cereals.

From a public health perspective, periods of high heat should prompt targeted anemia screening in vulnerable populations, supported by integrated environmental and maternal health interventions. Research gaps remain, particularly the absence of studies directly measuring temperature alongside hemoglobin concentrations. Current reliance on secondary datasets and cross-sectional analyses limits causal inference and may introduce methodological and cultural biases. Future research should incorporate direct measures of hemoglobin, multidisciplinary approaches, and longitudinal designs that account for climate, nutrition, infection, and gender dynamics to explain the drivers of maternal anemia in the region.

The main limitations of this study include accounting for intra-regional socioeconomic disparities within the dataset, such as variances in poverty levels, literacy rates, and access to healthcare infrastructure across regions. Determinants such as dietary iron intake, prevalence of infectious diseases (e.g., malaria, hookworm), genetic hemoglobin disorders, and access to prenatal care were not factored into the data analysis. Furthermore, only linear models were employed; therefore, potential non-linear relationships between temperature and anemia were not evaluated.

5. Limitations

The analysis is based on national-level, repeated cross-sectional data, and it was impossible to determine whether the same women were included in the surveys across years. The observed associations between ambient temperature and anemia in women of reproductive age indicate correlations at the country level and cannot be assumed to represent causal relationships for individual women. The reliance on country averages introduces the potential for ecological fallacy, as individual exposure to heat, varying socioeconomic conditions, and genetic predisposition cannot be separated from broader population trends. Although national datasets allow for regional comparisons, they may obscure within-country heterogeneity, such as urban-rural differences or state-level disparities in healthcare access and nutritional status. However, the data we did analyze confirms the relationship between ambient temperature and anemia in women of reproductive age.

The study was further limited by the data being generalized to regions of South Asia, which limited our ability to account for variables such as nutritional intake, cultural dietary habits, and reproductive history, which can substantially modify anemia outcomes, independent of environmental exposure [

19]. Further, since elevation influences local climate, using aggregated regional data may have reduced the accuracy of temperature estimates, as variations in altitude within countries can create meaningful differences in ambient temperature exposure [

25]. This study also did not incorporate specific risk factors such as education level and access to clean water, which could possibly contribute to the prevalence of anemia. While differences in climate exposure, such as women’s outdoor labor intensity and hydration practices, may partly explain the variation of the association between temperature and anemia, empirical data on these behaviors remain limited. Also, the uneven quality and coverage of health surveillance systems across South Asia may introduce reporting bias, particularly in rural and resource-limited settings.

Variation in the quality and reach of healthcare systems across South Asia likely influences the extent to which rising temperatures affect anemia outcomes in women of reproductive age. In countries with more developed public health infrastructure, women are more likely to receive nutritional counseling and access to iron supplementation, which can mitigate most health impacts of high ambient temperatures. Conversely, in areas with weak healthcare systems, women may have insufficient resources to manage anemia. Although these disparities may introduce some variation into our findings, the underlying trends remain constant and point towards temperature as a contributing factor in anemia prevalence.

6. Conclusions

Rising temperatures may act as a region-specific risk factor for a decline in maternal anemia, according to our findings. Environmental stressors, including climate change, can influence maternal health outcomes. To help reduce the burden of anemia, we can integrate temperature-related preventive strategies into maternal health planning through anemia screening, nutritional support, and heat-adapted antenatal care. Proactive strategies can also be employed, such as community education on the health effects of extreme heat. Coordinated action among governments, researchers, and policymakers will be essential to decrease the risk of anemia for women. Programs to support women in rural and resource-limited areas may be especially effective. Elevated ambient temperature is one of several factors shaping maternal anemia prevalence in South Asia. Some regions, especially South Asia, may experience greater health consequences from rising temperatures, likely due to underlying disparities in resilience, infrastructure, and access to care [

24]. Elevated temperatures contribute to reduced plasma volume, impaired nutrient absorption, and greater metabolic demand, all of which can worsen maternal anemia [

26]. Public health messaging focused on dietary habits during hot seasons can reduce anemia risk as behavioral and nutritional interventions are critical components of any preventative strategy [

27]. The challenges of climate change and high anemia prevalence could worsen maternal morbidity and perpetuate inequities in women’s health across the region without timely intervention.

Author Contributions

Dr. Muhammad A. Saeed: Original Idea, Paper Review, Administration, Data Review, Writing of draft, Final Review. Bhargavi Rao: Data Collection; Writing of draft, Data Review, Administration, Final review Mohammad R. Saeed: Original Idea, Data Collection, Writing of draft, Data Review, Administration, Final review. Xaviera Ayaz: Writing of draft, Final review Aleena Fatima: Writing of draft, Data Review, Data Collection Mohammad Usman: Writing of draft, Final review Vatsal Vemuri: Methodology; Data Review, Data Collection Uzair Mohammad: Final review Dr. Binish Arif Sultan: Final review Dr. Haris Majeed: Original Idea, Paper Review, Data Collection, Data Review, Writing of draft, Final Review.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were not applicable for this study due to the use of publicly available, anonymized data that does not involve direct interaction with human participants.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. These data are available from the World Health Organization (WHO) and can be accessed at

https://www.who.int/data. Access to specific datasets may require registration or approval from the WHO.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Turner, Jake, et al. “Anemia.” National Library of Medicine, StatPearls Publishing, 2023, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499994/.

- World Health Organization. “Anaemia.” World Health Organization, 10 Feb. 2025, www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/anaemia.

- Safiri, Saeid, et al. “Burden of Anemia and Its Underlying Causes in 204 Countries and Territories, 1990–2019: Results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019.” Journal of Hematology & Oncology, vol. 14, no. 1, 4 Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- World. (2025, July 9). Without urgent action, 18 million more women and girls in South Asia could suffer from anaemia by 2030. Who.int; World Health Organization: WHO. https://www.who.int/southeastasia/news/detail/09-07-2025-without-urgent-action-18-million-more-women-and-girls-in-south-asia-could-suffer-from-anaemia-by-2030.

- Sunuwar, Dev Ram, et al. “Prevalence and Factors Associated with Anemia among Women of Reproductive Age in Seven South and Southeast Asian Countries: Evidence from Nationally Representative Surveys.” PLOS ONE, vol. 15, no. 8, 13 Aug. 2020, p. e0236449. [CrossRef]

- Goodarzi, E., Beiranvand, R., Naemi, H., Darvishi, I., & Khazaei, Z. “Prevalence of Iron Deficiency Anemia in Asian Female Population and Human Development Index (HDI): An Ecological Study.” Obstetrics & Gynecology Science, 63(4), 497–505, 2020. [CrossRef]

- V Ramana Dhara, et al. “Climate Change & Infectious Diseases in India: Implications for Health Care Providers.” The Indian Journal of Medical Research, vol. 138, no. 6, Dec. 2013, p. 847, pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3978971/.

- Zhu, Yixiang, et al. “Global Warming May Significantly Increase Childhood Anemia Burden in Sub-Saharan Africa.” One Earth, vol. 6, no. 10, 1 Oct. 2023, pp. 1388–1399. [CrossRef]

- Imberti, Luisa, et al. “Effects of Climate Change on the Immune System: A Narrative Review.” Health Science Reports, vol. 8, no. 4, Apr. 2025, pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12007019/. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Hua, et al. “High Ambient Temperature May Increase the Risk of Anemia in Pregnancy: Identifying Susceptible Exposure Windows.” The Science of the Total Environment, vol. 926, 29 Mar. 2024, pp. 172059–172059. [CrossRef]

- Auriti, Cinzia, et al. “Pregnancy and Viral Infections: Mechanisms of Fetal Damage, Diagnosis and Prevention of Neonatal Adverse Outcomes from Cytomegalovirus to SARS-CoV-2 and Zika Virus.” Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease, vol. 1867, no. 10, Oct. 2021, p. 166198. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H., Li, Y., Liu, X., Wen, Q., Yao, C., Zhang, Y., Xie, W., Wu, W., Wu, L., Ma, X., Li, Y., Ji, A., & Cai, T. (2024). High ambient temperature may increase the risk of anemia in pregnancy: Identifying susceptible exposure windows. The Science of the Total Environment, 926, 172059–172059. [CrossRef]

- CDC. (2024). Clinical Overview of Heat and Pregnancy. Heat Health. https://www.cdc.gov/heat-health/hcp/clinical-overview/heat-and-pregnant-women.html.

- Torlesse, H., & Aguayo, V. M. (2018). Aiming higher for maternal and child nutrition in South Asia. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 14, e12739. [CrossRef]

- Mayo Clinic. (2021, November 17). Thalassemia - Symptoms and Causes. Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/thalassemia/symptoms-causes/syc-20354995.

- Imberti, L., Tiecco, G., Logiudice, J., Castelli, F., & Quiros-Roldan, E. (2025). Effects of Climate Change on the Immune System: A Narrative Review. Health Science Reports, 8(4). [CrossRef]

- Liao, H., Lyon, C. J., Ying, B., & Hu, T. (2024). Climate change, its impact on emerging infectious diseases and new technologies to combat the challenge. Emerging Microbes & Infections, 13(1). [CrossRef]

- WHO. (2024, May 28). Heat and health. World Health Organization; World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/climate-change-heat-and-health.

- Gibore NS, Ngowi AF, Munyogwa MJ, Ali MM. Dietary Habits Associated with Anemia in Pregnant Women Attending Antenatal Care Services. Current Developments in Nutrition. 2020 Dec 11;5(1). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37833703/.

- Bloomer, S. A., Kregel, K. C., & Brown, K. E. (2014). Heat stress stimulates hepcidin mRNA expression and C/EBPα protein expression in aged rodent liver. Archives of gerontology and geriatrics, 58(1), 145–152. [CrossRef]

- Waller, M. F., & Haymes, E. M. (1996). The effects of heat and exercise on sweat iron loss. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 28(2), 197–203. [CrossRef]

- Alkhaldy, H. Y., Awan, Z. A., Abouzaid, A. A., Elbahaey, H. M., Al Amoudi, S. M., Shehata, S. F., & Saboor, M. (2022). Effect of Altitude on Hemoglobin and Red Blood Cell Indices in Adults in Different Regions of Saudi Arabia. International journal of general medicine, 15, 3559–3565. [CrossRef]

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Military Nutrition Research; Marriott BM, editor. Nutritional Needs in Hot Environments: Applications for Military Personnel in Field Operations. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 1993. 10, Effects of Heat on Appetite.

- Sangkhae, V., Fisher, A. L., Ganz, T., & Nemeth, E. (2023). Iron Homeostasis During Pregnancy: Maternal, Placental, and Fetal Regulatory Mechanisms. Annual review of nutrition, 43, 279–300. [CrossRef]

- Saeed, M. A., Zaidi, A., Saeed, M. R., Khokhar, H., Sultan, B. A., Khan, S., Dawer, A., & Majeed, H. (2025). Impacts of Ambient Temperatures on Pediatric Anemia in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Regional Ecological Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(9), 1364. [CrossRef]

- Xiao H, Li Y, Liu X, Wen Q, Yao C, Zhang Y, Xie W, Wu W, Wu L, Ma X, Li Y, Ji A, Cai T. High ambient temperature may increase the risk of anemia in pregnancy: Identifying susceptible exposure windows. Sci Total Environ. 2024 May 20;926:172059. . Epub 2024 Mar 29. [CrossRef]

- Gibore NS, Ngowi AF, Munyogwa MJ, Ali MM. Dietary Habits Associated with Anemia in Pregnant Women Attending Antenatal Care Services. Curr Dev Nutr. 2020 Dec 11;5(1):nzaa178. . PMID: 33501404. [CrossRef]

- Imberti L, Tiecco G, Logiudice J, Castelli F, Quiros-Roldan E. Effects of Climate Change on the Immune System: A Narrative Review. Health Sci Rep. 2025 Apr 18;8(4):e70627. . PMID: 40256129; PMCID: PMC12007019. [CrossRef]

- Semba RD, Askari S, Gibson S, Bloem MW, Kraemer K. The Potential Impact of Climate Change on the Micronutrient-Rich Food Supply. Adv Nutr. 2022 Feb 1;13(1):80-100. [CrossRef]

- Ghio AJ, Soukup JM, Dailey LA, Madden MC. Air pollutants disrupt iron homeostasis to impact oxidant generation, biological effects, and tissue injury. Free Radic Biol Med. 2020 May 1;151:38-55. . Epub 2020 Feb 21. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).