3.1. Motivation and Research Shift

Although this research ultimately centers on the analysis of the Riemann Zeta function, the method for locating its zeros was first discovered during an independent investigation of semiprime numbers. In that earlier study, the focus was on expressing a semiprime number N, composed of two prime factors and , through an algebraic structure that could reveal deeper numerical symmetries.

It was observed that

N,

, and

could be conveniently related using a quadratic form. The standard and existing approach begins by defining the unknown primes

p and

q such that:

The sum of the two factors, denoted , is equally important. In certain factoring methods, this value is associated with expressions derived from the totient function or other auxiliary formulations (sometimes referred to in the literature as ).

Given the relationships above, one can form a quadratic equation whose roots correspond to the two prime factors. For a general quadratic equation of the form

, the sum of the roots is

, and the product of the roots is

c. Substituting

and

yields:

The solutions of this equation are therefore the two prime factors:

Finding this approach computationally demanding and difficult to extend efficiently, the method was ultimately set aside in favor of exploring a more effective alternative.

3.2. N-to-Complex Conversion

The method described in this section, focus on the

mean between

and

. A quadratic equation involving

N,

m,

and

can be rewritten using this straightforward approach:

The goal is to solve for .

First, from Equation (

2), express

in terms of

m and

.

Multiply both sides by 2:

Isolate :

Now, substitute this expression for

into Equation (

1):

Expand the equation:

To solve for

, rearrange into a standard quadratic equation (

):

This is a quadratic equation where

,

, and

. using the quadratic formula to solve for

:

Substitute the values of

a,

b, and

c:

Simplifying the square root by factoring out a 4:

Finally, divide both terms in the numerator by 2:

This simple algebraic exercise provides the conceptual foundation of the present research and formally justifies both the name of this section and the title of the paper.

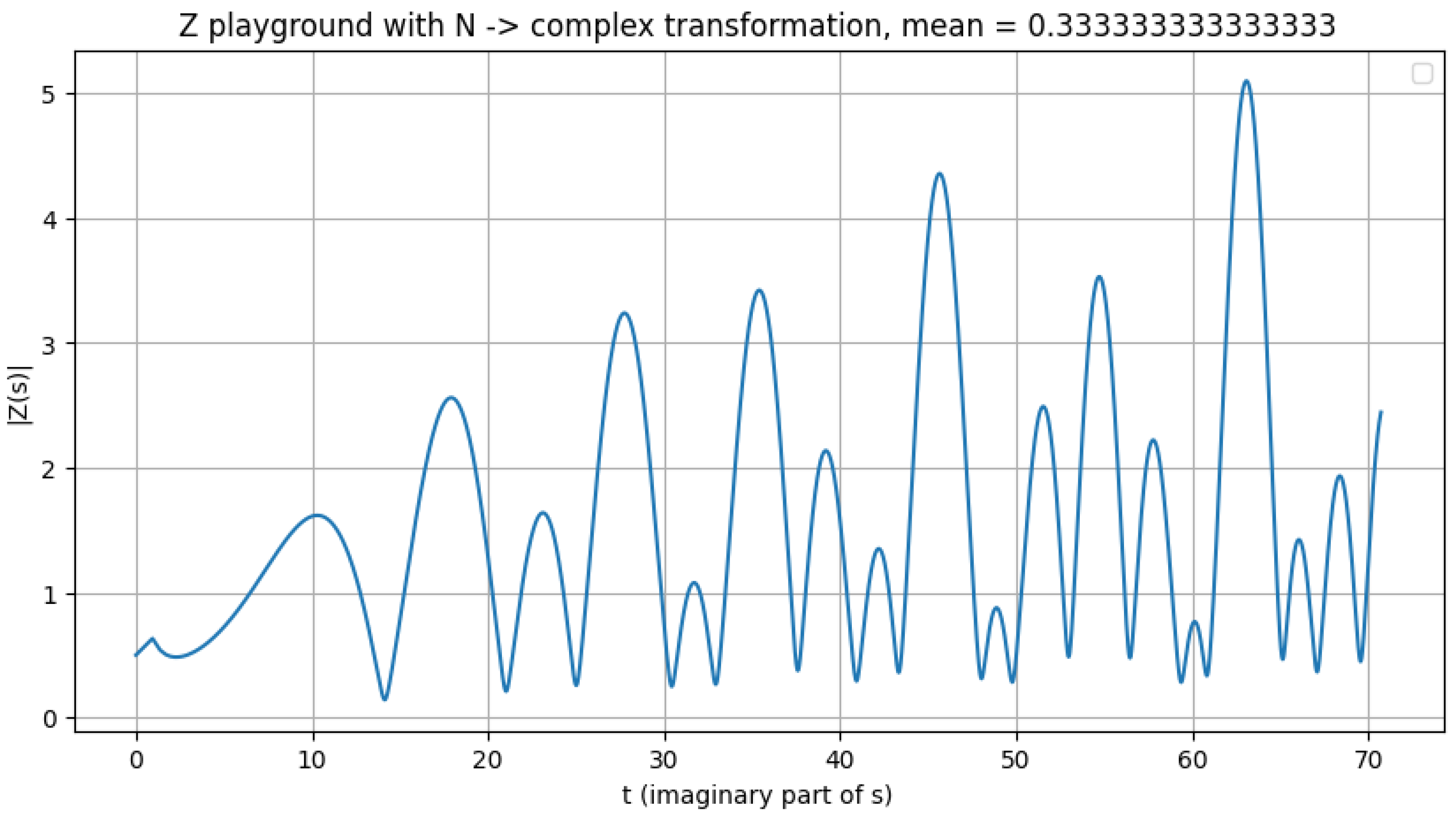

was originally introduced as part of an exploratory study aimed at analyzing the variable m and the area under the curve of the quadratic expression, in search of a possible relationship between m or the area and N, where N represents the semiprime number to be factorized.

A series of statistical models were subsequently developed in Python to evaluate the predictive relationship between these parameters and N. Although some preliminary results appeared promising, further testing revealed that neither the area under the quadratic curve nor the variable m exhibited a sufficiently strong or consistent correlation with N. This outcome, while initially discouraging, served as a valuable turning point: What if we move the mean m to a known point like 1 (one)?

To answer this question, the equation:

Will serve better. It is worth noting that when

, the expression causes the square root term to become undefined, since

. Anecdotally, this detail was initially overlooked during the generation of test datasets, which inadvertently produced millions of invalid results. After identifying this simple oversight, it became evident that the solutions for

p could be expressed as two complex numbers, provided that the equation is formulated appropriately as follows:

, i is the standard notation for square root of -1

For researchers interested in prime numbers, the Riemann Zeta function is a recurrent and foundational topic. It is well established that, in order to evaluate the Zeta function along the critical line where its nontrivial zeros are conjectured to lie, the real part of the complex variable s must be . Consequently, the parameter m in this study was intuitively fixed at 1/2, aligning with the critical line of the Riemann zeta function. From this point onward, the focus of the research was redirected toward the investigation of the Z-function.

3.3. Valley Scanner Algorithm

The term valley scanner will appear recurrently throughout the following sections. It originated from the datasets computed under the following input parameters:

A range of N, consisting of real, positive integer values (e.g., 1–10000).

The variable p, hereafter denoted as s, to align with the standard notation used in the study of the Zeta function, evaluated at .

The imaginary part as t, and Isolating N:

The central objective of this stage was to compute the magnitude

across a continuous range of

N values, and to analyze the resulting datasets through direct observation and graphical representation. For this operation, a dedicated Python script was developed (the complete source code is presented on the following page).

1 Please note that copying the code directly from this document may alter indentation or character encoding, potentially leading to syntax errors.

For the fully formatted and maintained version, please refer to the public repository:

import subprocess

import sys

def ensure_lib(package):

try:

__import__(package)

except ImportError:

subprocess.check_call(

[sys.executable, "-m", "pip", "install", package, "--quiet"]

)

# Ensure required libraries

ensure_lib("mpmath")

ensure_lib("matplotlib")

import mpmath as mp

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

mp.dps = 250 # precision

# From N, we Calculate:

# m + sqrt(N - m^2) i

def N_to_complex(N, m):

t = mp.sqrt(N - m ** 2)

s = m + t * 1j

return s, t

# Z

def Z(N, m):

s, t = N_to_complex(N, m)

z_val = mp.zeta(s)

return t, z_val

# Dataset for plotting

dataset = []

m = mp.mpf(’0.5’) # <-------------- IMPORTANT: MEAN = 1/2

for n in range(5000):

t, z = Z(n, m)

dataset.append([t.real, abs(z)])

ts = [t for t, _ in dataset]

zs = [z for _, z in dataset]

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 5))

plt.plot(ts, zs)

plt.xlabel("t (imaginary part of s)")

plt.ylabel("|Z(s)|")

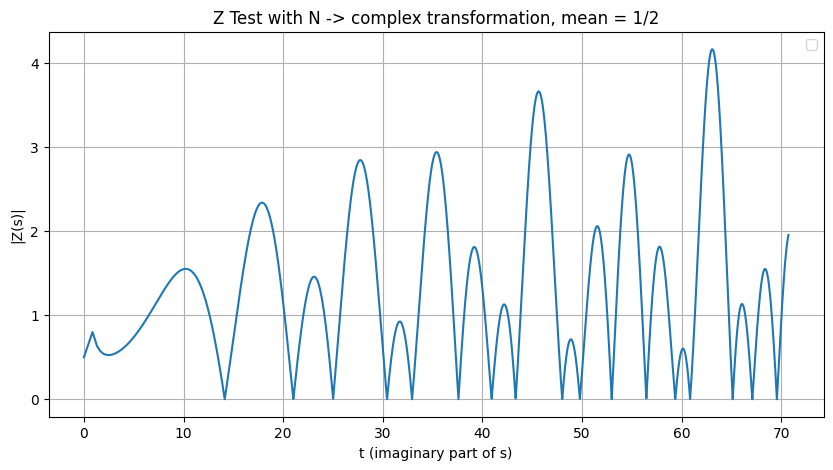

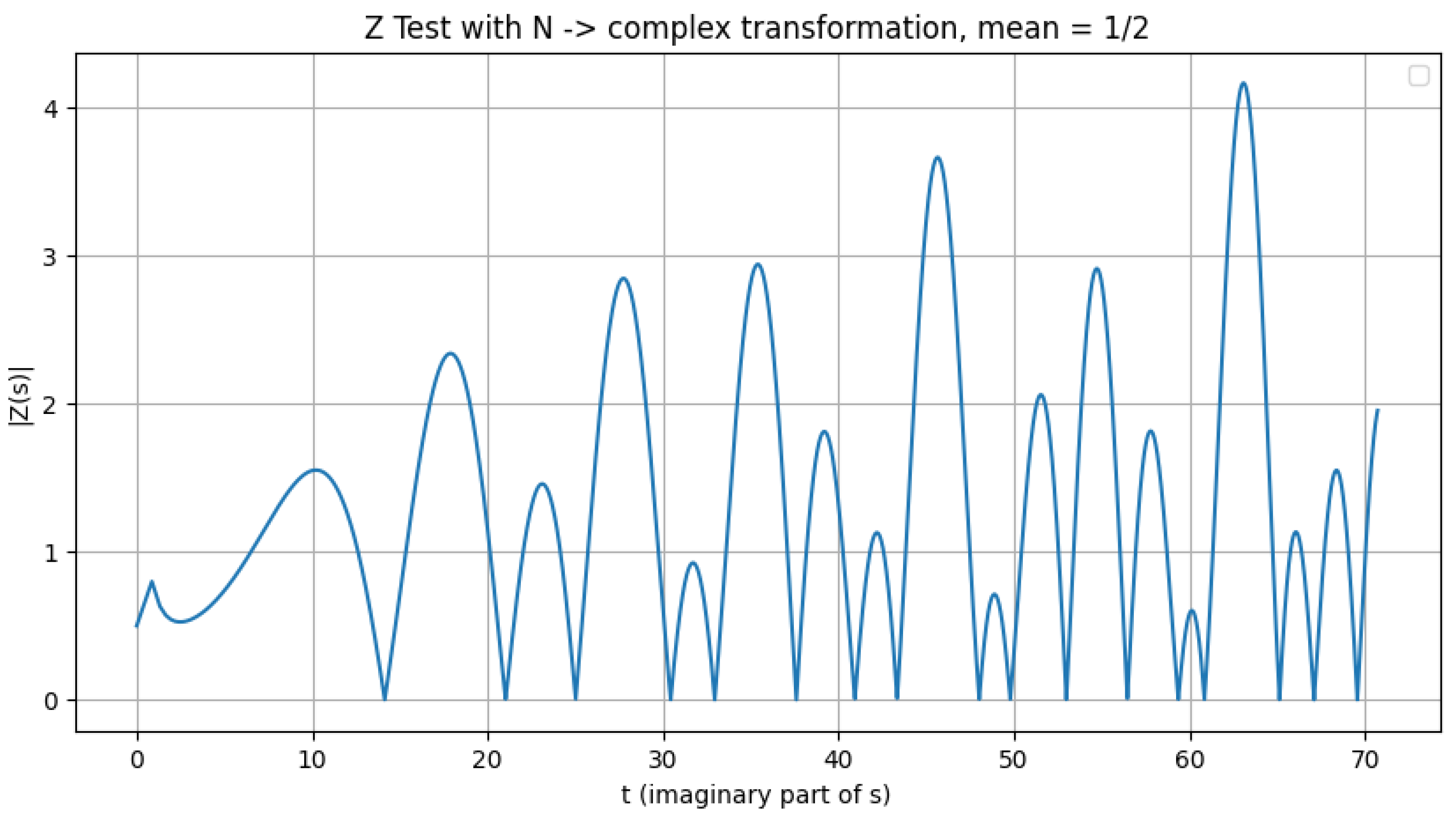

plt.title("Z Test with N -> complex transformation, mean = 1/2")

plt.legend()

plt.grid(True)

plt.show()

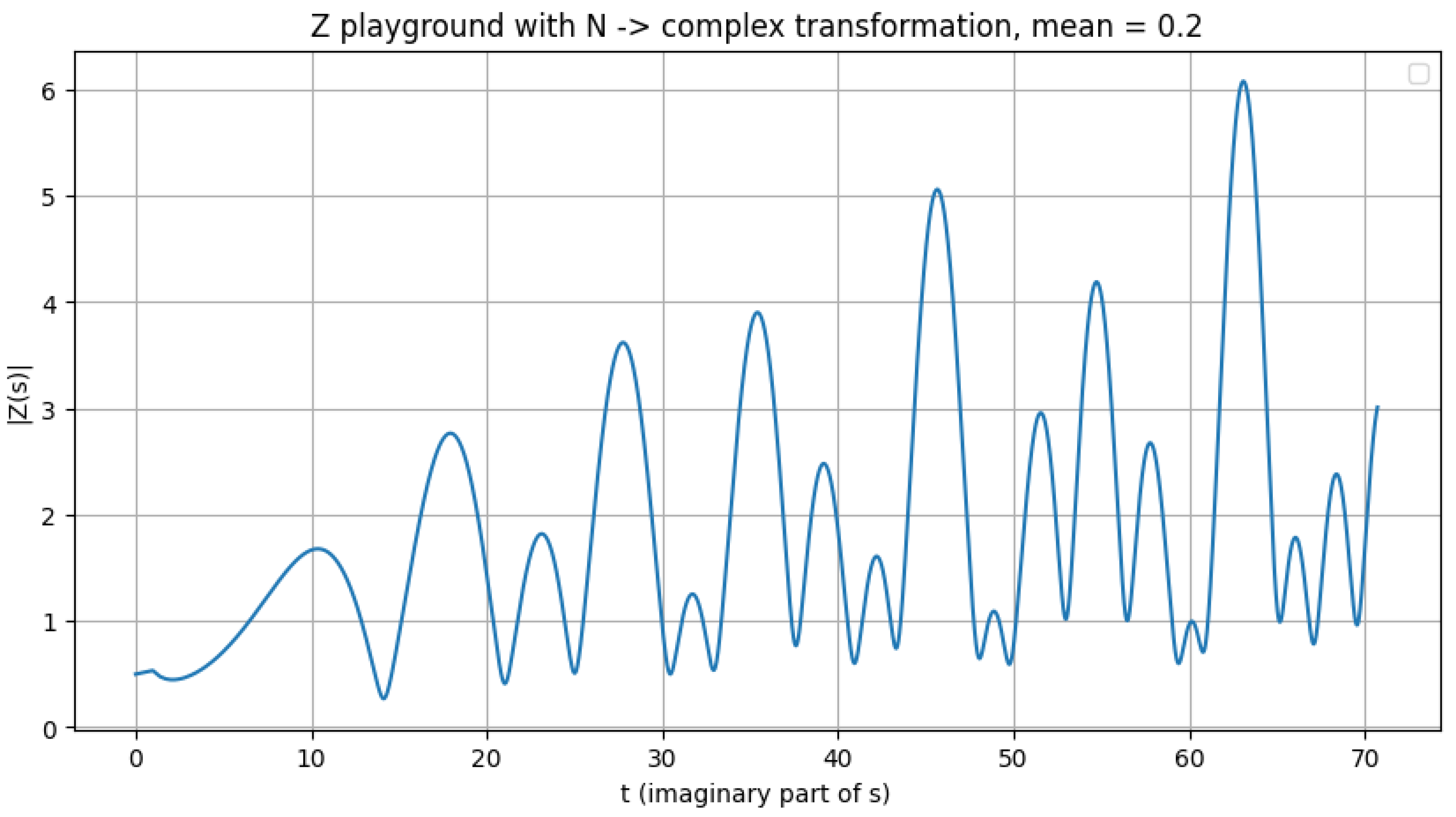

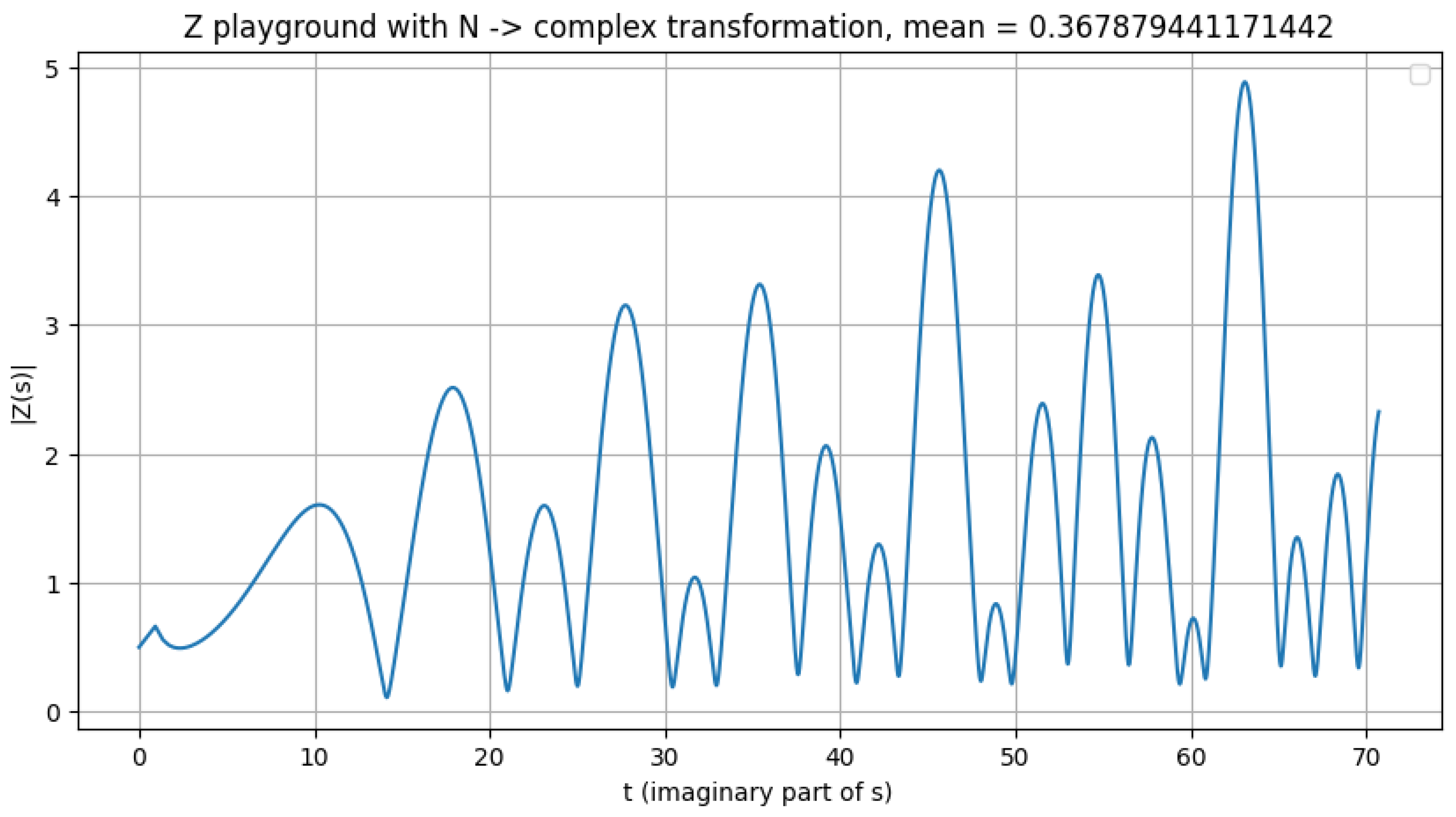

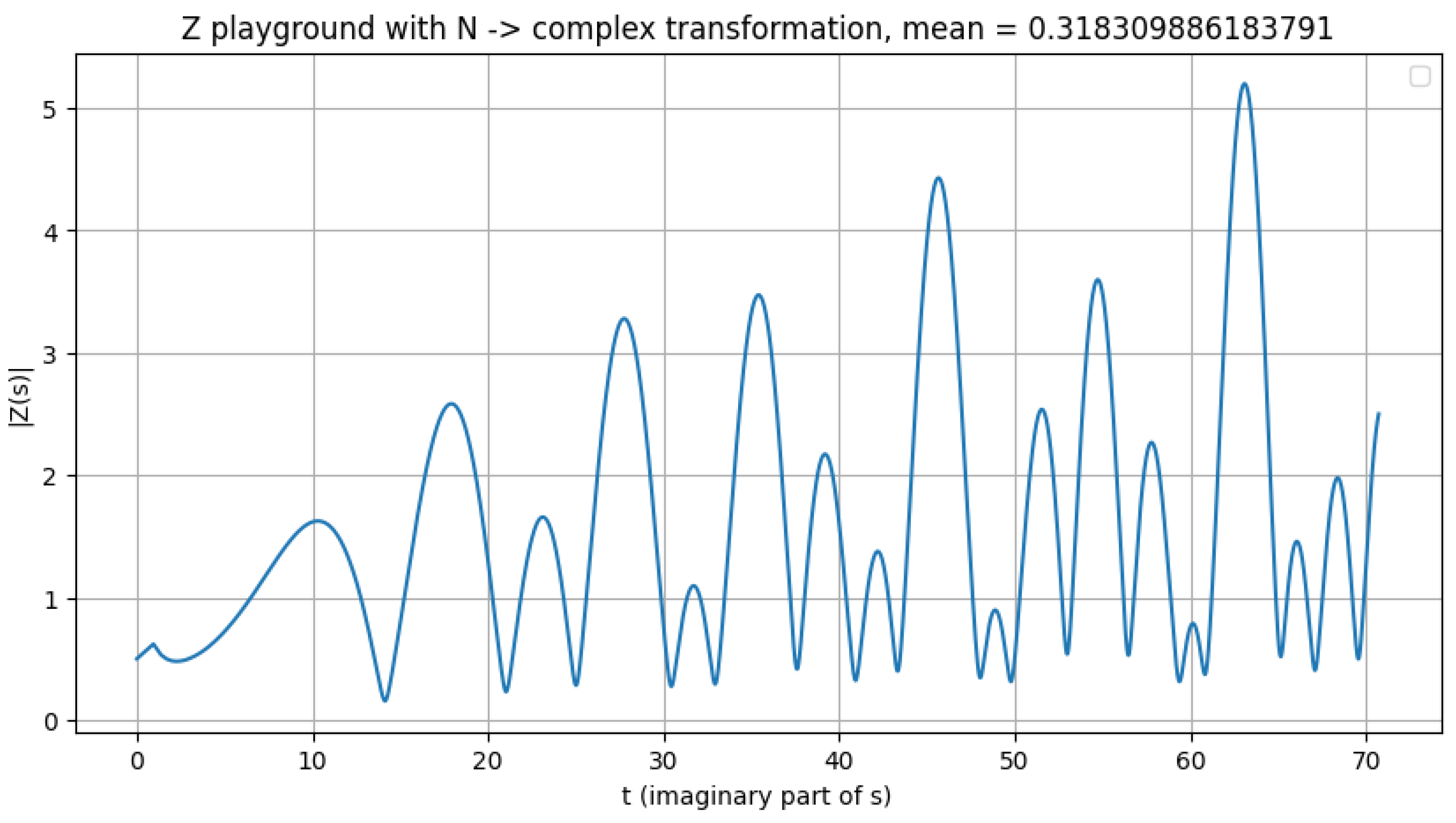

Results:

Figure 1.

Illustration of the valley scanner detecting zeros.

Figure 1.

Illustration of the valley scanner detecting zeros.

Table 1.

First Non-trivial Zeros of the Riemann Zeta Function

Table 1.

First Non-trivial Zeros of the Riemann Zeta Function

| Index |

Imaginary Part () |

| 1 |

14.1347251417346937904572519835625 |

| 2 |

21.0220396387715549926284795938969 |

| 3 |

25.0108575801456887632137909925628 |

| 4 |

30.4248761258595132103118975305840 |

| 5 |

32.9350615877391896906623689640747 |

| 6 |

37.5861781588256712572177634807053 |

| 7 |

40.9187190121474951873981269146334 |

| 8 |

43.3270732809149995194961221654068 |

| 9 |

48.0051508811671597279424727494277 |

| 10 |

49.7738324776723021819167846785638 |

| 11 |

52.9703214777144606441472966088808 |

| 12 |

56.4462476970633948043677594767060 |

| 13 |

59.3470440026023530796536486749922 |

| 14 |

60.8317785246098098442599018245241 |

| 15 |

65.1125440480816066608750542531836 |

| 16 |

67.0798105294941737144788288965221 |

| 17 |

69.5464017111739792529268575265547 |

Visually, the resulting plot is self-explanatory. This behavior can be described as follows: when the Riemann Zeta function is evaluated using at , and for N evaluated over any numerical range, the computed values of consistently approach zero—demonstrating convergence along the critical line, as expected from the theoretical framework of the Riemann Hypothesis.

Refining the range of N values by introducing decimal precision yields a closer approximation of to zero. The accompanying Python script reproduces this behavior consistently across any chosen range of N; however, it should be noted that these computations are computationally demanding.

This is the dataset calculated from the python script showing the approximations compared to confirmed zeros:

Table 2.

Comparison between computed and reference zeros of the Riemann Zeta function.

Table 2.

Comparison between computed and reference zeros of the Riemann Zeta function.

| N |

Computed t

|

t from Public Database |

| 200 |

14.13329402510257 |

14.13472514 |

| 442 |

21.017849556983705 |

21.02203964 |

| 626 |

25.014995502697975 |

25.01085758 |

| 926 |

30.426140077242792 |

30.42487613 |

| 1085 |

32.93554311074891 |

32.93506159 |

| 1413 |

37.586566749305526 |

37.58617816 |

| 1675 |

40.92370951 |

40.91871901 |

| 1877 |

43.32147273581544 |

43.32707328 |

| 2305 |

48.00781186432057 |

48.00515088 |

| 2478 |

49.77700272214067 |

49.77383248 |

| 2806 |

52.96933074902875 |

52.97032148 |

| 3186 |

56.442448564887755 |

56.44624770 |

| 3522 |

59.34433418617145 |

59.34704400 |

| 3701 |

60.83378995 |

60.83177853 |

| 4240 |

65.11336268386084 |

65.11254405 |

| 4500 |

67.08017591 |

67.07981053 |

| 4837 |

69.54674686856315 |

69.54640171 |

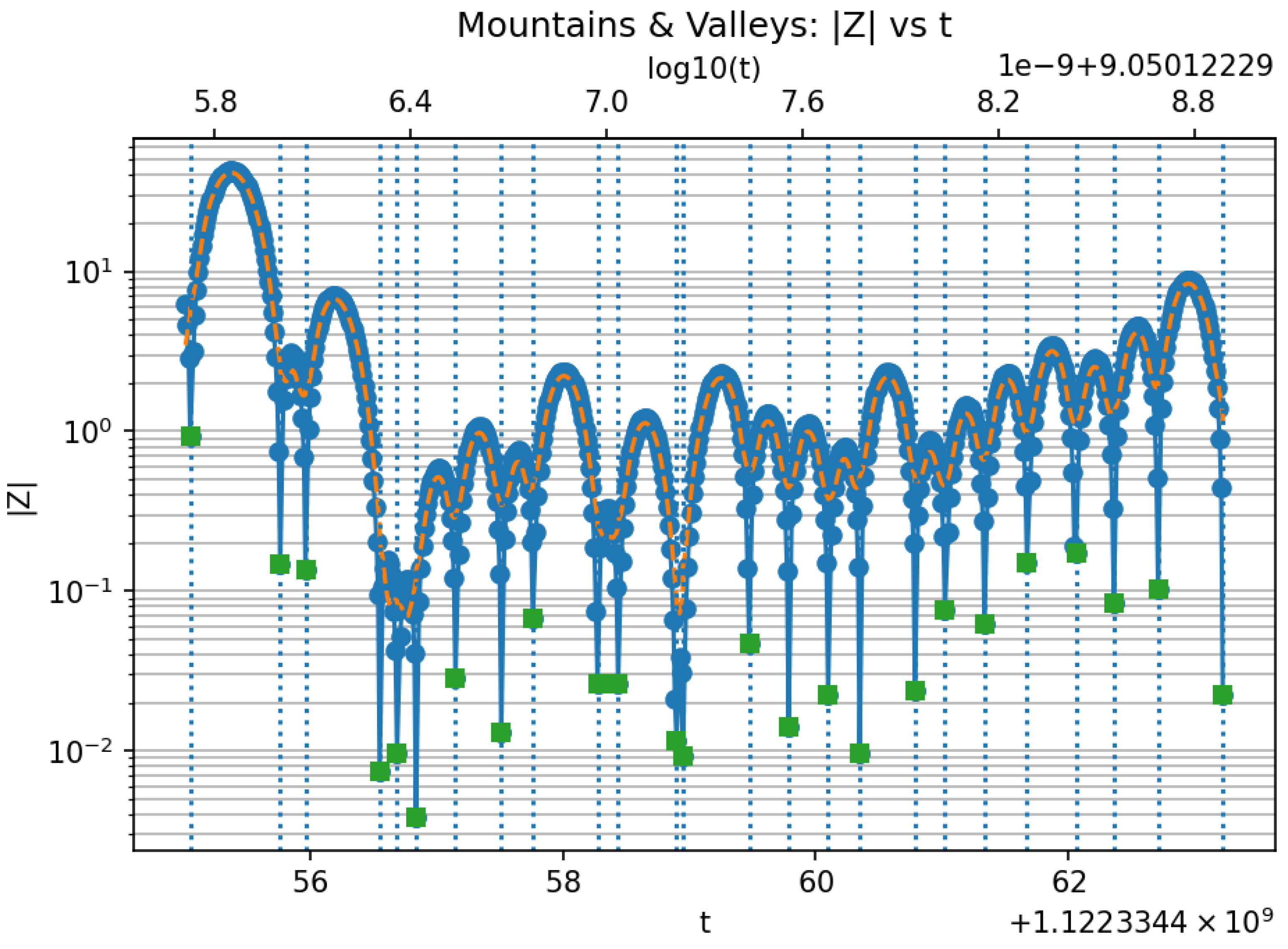

3.4. Identifying Zeros by Detecting Consecutive Minima of

Having obtained reproducible values across multiple ranges of N, it became necessary to test this approach at very high magnitudes of t as part of scientific rigor. While Python provides a remarkable ecosystem for numerical exploration of , the process—informally termed “mountain walking” or the “valley scanner” soon became computationally prohibitive.

At this stage, it should be mentioned that AI-assisted tools were employed to accelerate development. Throughout this research, ChatGPT 5/4.5 was used to iteratively generate, refine, and validate code implementations, effectively serving as a peer collaborator during the construction of the numerical framework.

Mountain Walking and Valley Scanner Algorithm

The central idea of the method is to traverse the numerical “landscape” of as a function of N and t, identifying valleys corresponding to local minima—potential zeros of the Riemann Zeta function. The algorithm, much like the Python code, operates in the following manner:

Set an initial value , the imaginary part of s, which may or may not correspond to a true zero.

Transform

into its corresponding real-number representation

N using the established

mapping (see Section

1).

Increment N by one, i.e., , and compute the corresponding .

Evaluate for both and .

If , the algorithm interprets this as a descent toward a valley—an interval likely containing a zero. Conversely, if , the process is ascending a mountain, and the algorithm must continue forward to reach the next descent.

During descent, when the algorithm detects a reversal in the gradient (a bounce), it records the current point as a local minimum, i.e., a candidate zero.

The corresponding t-value at this point is then refined using a Newton root-finding method to obtain the precise zero location.

Method of evaluating the Z function

The

Riemann–Siegel formula is employed for high values of

t:

where

represents the remainder term corrected via the

Gabcke method.

The phase function

is evaluated using

Stirling’s approximation for

, allowing high-precision computation without overflow:

Each candidate zero obtained from the valley scanner is refined using a Safeguarded Newton refinement with Pegasus fallback (hybrid Newton–secant–Pegasus). 128-bit to 256-bit precision, ensuring convergence even for steep or oscillatory regions.

Validation is conducted by comparison with the Odlyzko–Schönhage algorithm and cross-verified using the Ball test for consistency across neighboring zeros.

3.5. Parallelization and Cloud Execution

The computation of

through the Riemann–Siegel formula involves a large summation term:

where each summand

is independent of the others for a fixed

t. This independence makes the summation term an ideal candidate for

parallelization. Each thread (or compute node) evaluates a portion of the partial sums

and a reduction step aggregates all

to yield the final

. The remainder term

, corrected by the Gabcke expansion, is then added as a separate serial step.

Parallel execution therefore targets the summation domain of the Riemann–Siegel series, not the remainder correction. In practice, this allows the workload to scale linearly with the number of available CPU cores. For cloud execution, AWS EC2 instances were configured to distribute the summation across all physical cores using OpenMP directives. Each thread evaluates its assigned range of n values, ensuring thread-safe accumulation via reduction clauses, while the overall computation remains deterministic and numerically stable due to the associative nature of the cosine summand.

The parallelized portion of the computation is thus the evaluation of

with each range of

n processed concurrently. This design enables efficient scaling for very large

t, where

may reach millions.

3.6. Why Spacing Heuristics (And Naive Prefiltering) Can Skip Zeros

A classical asymptotic for the zero-counting function on the critical line is

which implies an average zero

density Hence the

average spacing between consecutive zeros near height

T is

Key caveat.

While (

3) is an excellent

mean predictor, the

local spacing fluctuates considerably. If one advances

t by a deterministic step

(or rejects points by a naive

threshold), genuine zeros can be skipped.

Concrete example (skip demonstrated).

Consider two consecutive zeros (as verified against high-precision tables) near

Their empirical gap is

The average-spacing prediction at

from (

3) is

If one used

, the probe would jump to

overshooting the true next zero at

. This directly illustrates that spacing-only stepping can miss zeros.

Implication for the valley scanner.

During development we also experimented with prefiltering by discarding points where exceeded a threshold before refinement. In regions with sharper or asymmetric valleys, this likewise rejected valid neighborhoods, degrading recall. Consequently, the final algorithm avoids spacing-only jumps and uses dense local sampling with minima detection, followed by robust bracketing and root refinement (Newton–secant with safeguarded bracketing), to prevent skipped zeros.

Why GPU acceleration is not used.

While the Riemann–Siegel summation is inherently parallel, its implementation for large t values requires high–precision arithmetic (typically 200–500 bits), which is not natively supported by GPU architectures. CUDA cores operate efficiently on fixed–width floating–point types (float32, float64), but do not provide hardware support for arbitrary–precision formats such as those implemented by the MPFR and MPC libraries used in this project. Emulating multi–precision on GPUs would require manually splitting mantissas across multiple registers and synchronizing additions and carries, introducing overheads that completely negate the theoretical parallel advantage.

Additionally, GPU kernels are optimized for massive, homogeneous workloads with simple arithmetic pipelines. In contrast, the Riemann–Siegel computation involves branch–intensive operations, logarithmic and trigonometric functions, and frequent precision adjustments all of which are poorly suited to GPU thread execution models. Memory coherence and divergence among threads would further reduce throughput.

For these reasons, the high–precision calculations of are executed on CPU instances with many physical cores (e.g., c7i.8xlarge), using OpenMP to distribute the summation work across threads. This CPU–based approach provides deterministic reproducibility, robust numerical stability, and easier integration with the MPFR environment, while still benefiting from significant parallel speedups proportional to the number of cores.

Software and computational stack

C++ — core numerical computation, employing the MPFR library for arbitrary precision arithmetic.

AWS EC2 — high-performance compute instances with configurable CPU counts for parallel Z-evaluations.

AWS Cognito — secure user authentication for the web console.

AWS Lambda — serverless backend for initiating batch computations, monitoring, and handling S3 storage.

AWS ECR + React — containerized web frontend for real-time visualization of the valley scanner up to .

AWS S3 — persistent data storage for computed zeros and logs.

Docker — A portable .exe is available to be executed locally.

The accompanying

web application capable of calculating zeros up to

is accessible upon authorization. The core computation code is not publicly archived at this stage, pending independent peer validation of the numerical results. Upon request from qualified reviewers or collaborators, the author will gladly provide access to the computation core to enable verification and replication of the reported findings. Additionally, a

Docker public image is provided for local study and reproduction of this method. Please refer to the README.md file here:

README