Submitted:

13 November 2025

Posted:

14 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. Image Retrieval-Based Localization

2.2. Learned Local Feature Matching

2.3. Rendering and View Synthesis Methods

2.4. Hybrid Geometry-Learning Approaches

3. Methodology

3.1. Problem Definition

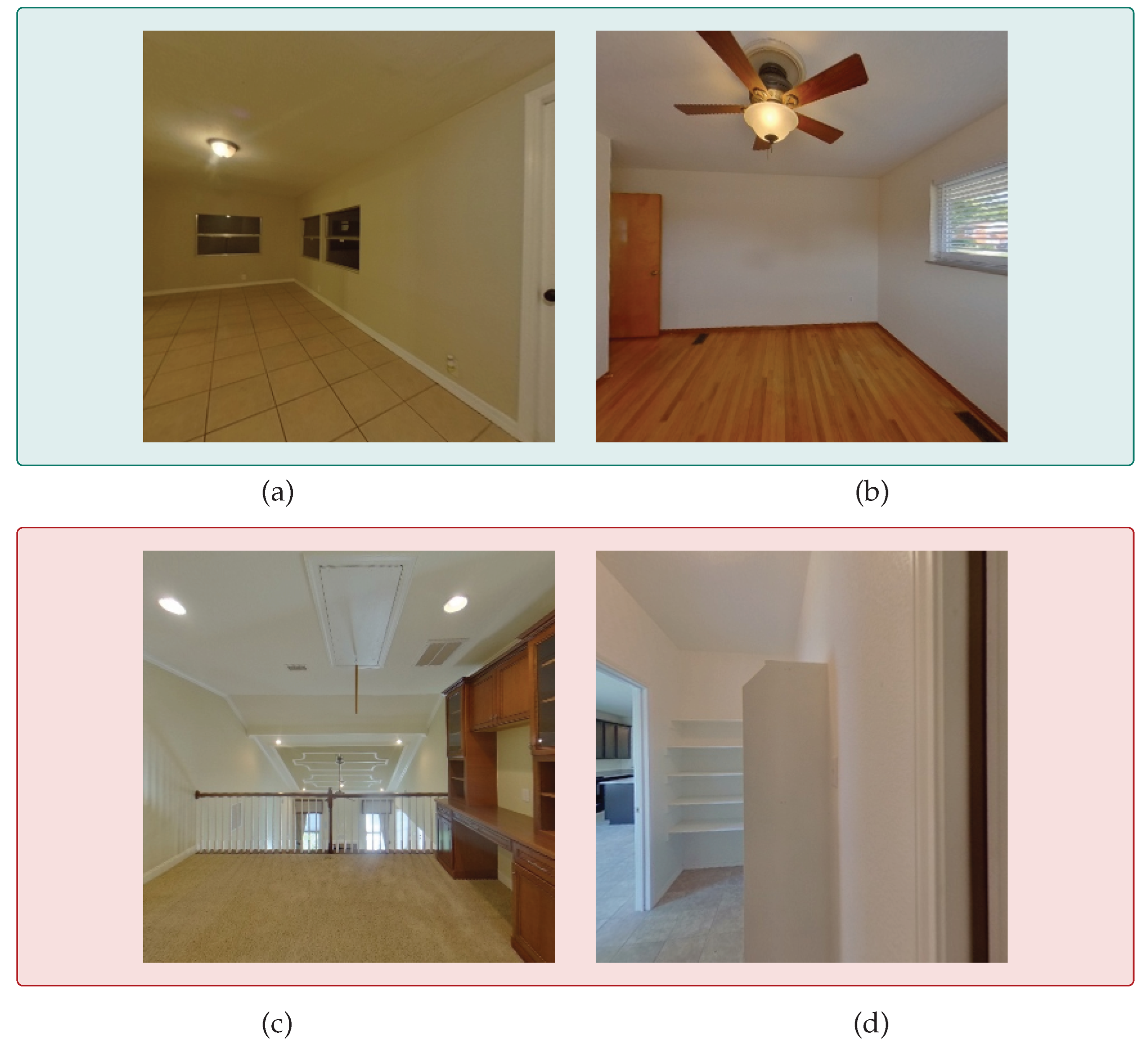

3.2. Quantifying Layout Ambiguity

3.3. Theoretical Motivation: A Bayesian View

-

Phase 1 – Retrieval as the PriorWe first use semantic mesh segmentation and viewport matching to rapidly narrow the search space from potentially thousands of poses to a small, high-recall set . The retrieval scores assigned to these candidates are proportional to and thus act as an empirical prior. This step is deliberately tuned for coverage: even if some top-ranked candidates are wrong, the goal is to ensure that the true pose remains within the short list.

-

Phase 2 – Descriptor Matching as the LikelihoodWe then introduce an independent source of evidence by computing rotation-invariant circular descriptors for both the query and each candidate rendering . The cosine similarity between and measures how consistent the global layout is between the two views, regardless of in-plane rotation. We model this as a likelihood term:where the exponential ensures higher similarity values correspond to higher likelihood (by introducing soft-max style weighting that removes negative weights and magnifies stronger matches).The final posterior probability for each candidate pose is then:This Bayesian update ensures that candidates supported by both the high-recall retrieval prior and the ambiguity-resolving descriptor likelihood rise to the top. Importantly, it allows correct poses that were initially ranked low due to retrieval bias to overtake incorrect top-1 candidates. This is something correlation-based refinements cannot achieve reliably. In high-ambiguity layouts, this principled combination of evidence is the key to systematically improving accuracy without additional geometric solvers or per-scene retraining.

3.4. Rotation Invariance via Group Theory

3.5. Algorithm Pipeline

-

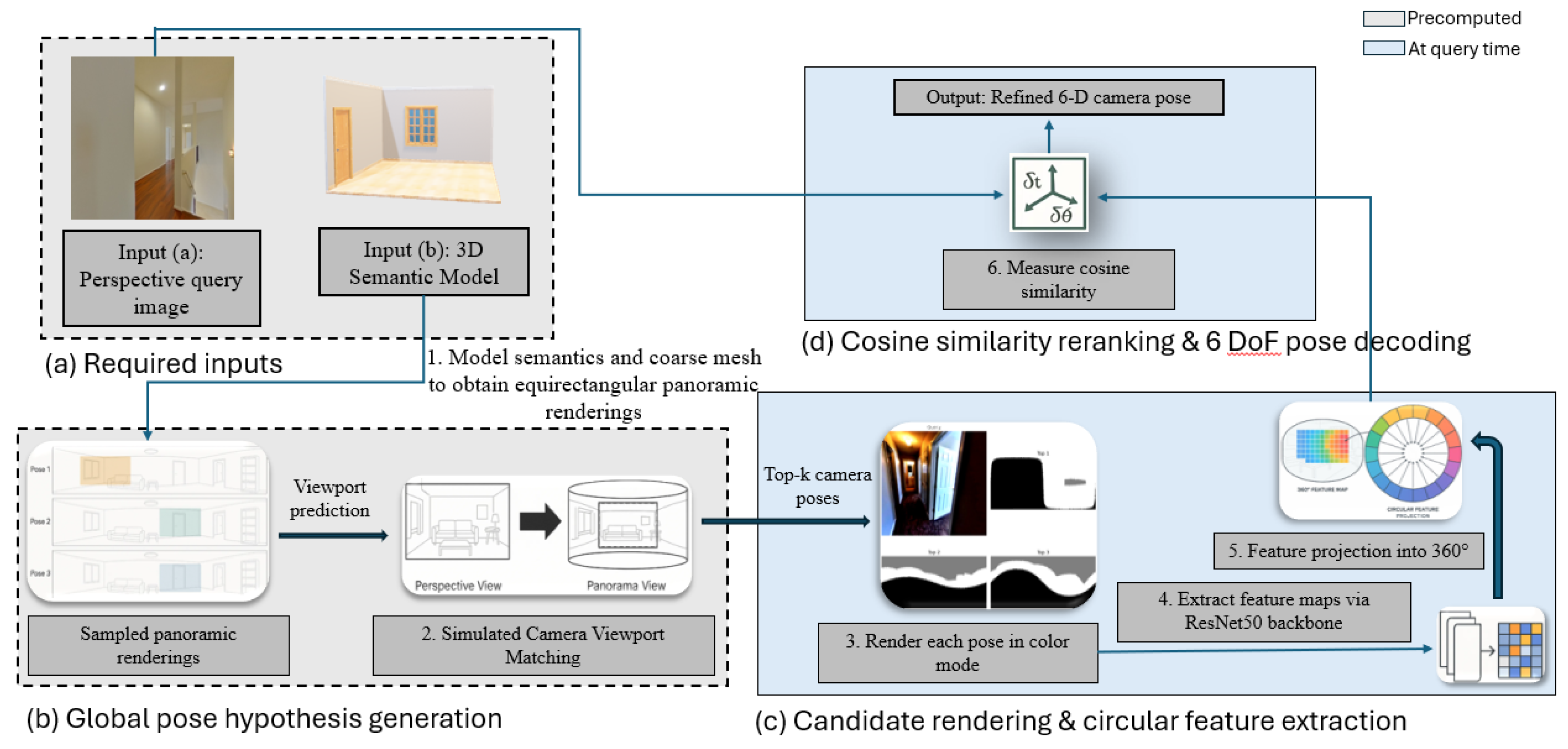

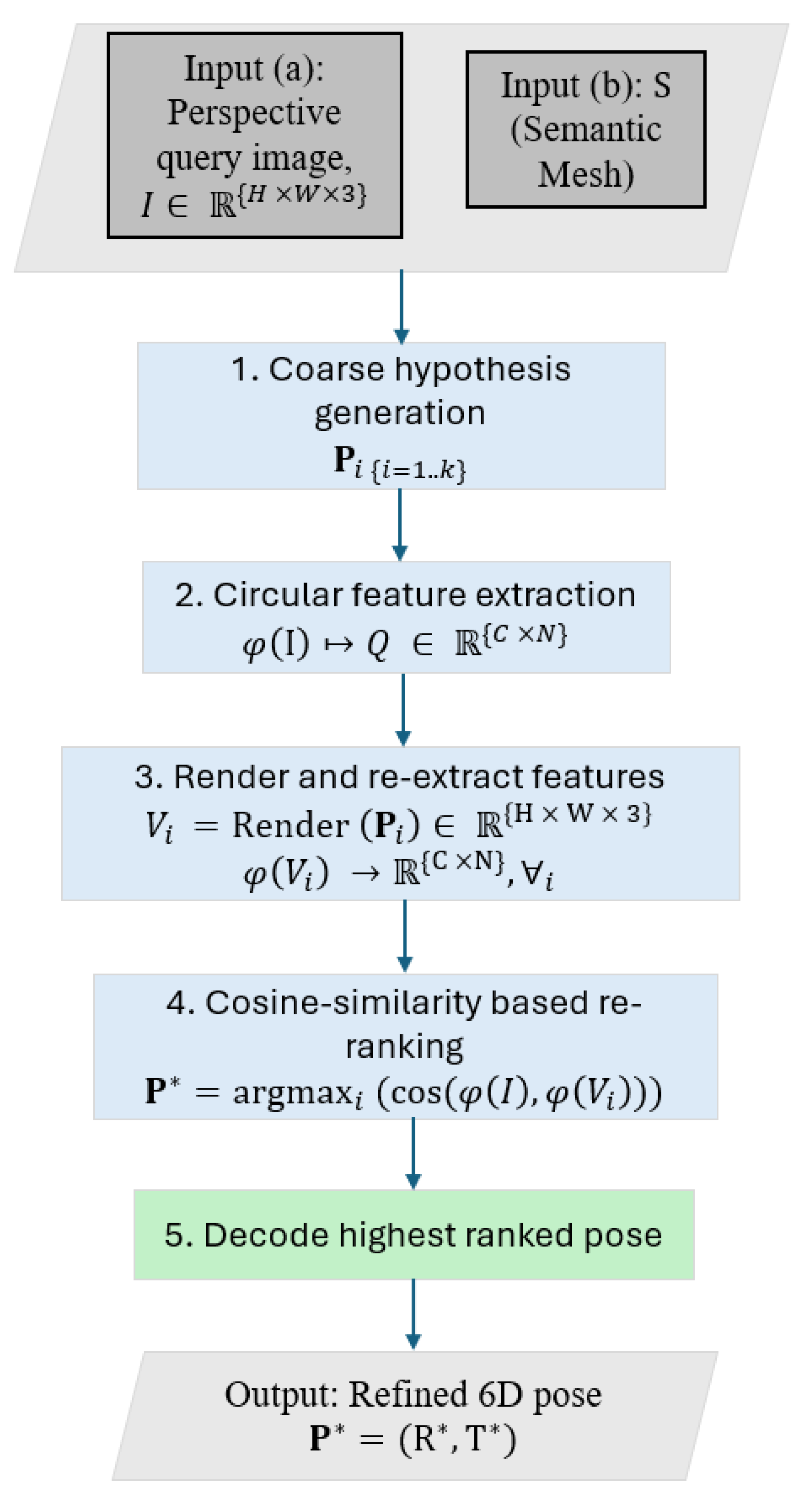

Stage 1: InitializationAt query time, we begin by semantically segmenting the 3D room mesh and then render a set of panoramic viewports on a uniform 1.2 m × 1.2 m grid, requiring far fewer samples than LaLaLoc’s [22] layout based approach. Inspired by the basal pipeline in [9], each rendered panorama and the input perspective image are passed through pretrained backbones: EfficientNet-S [37] for the query images and DenseNet [38] for the panoramas, to produce dense feature maps.

-

Stage 2: Initial Pose EstimationWe compute depth-wise correlations between the query’s features and each panorama’s features, yielding a similarity score for every candidate viewport. A lightweight MLP takes the top-k scoring candidates and directly regresses their 6-DoF poses. All training and evaluation follow the standard ZInD split [11]. This coarse retrieval stage (Figure 2 steps (a) and (b)) efficiently narrows the search from thousands of potential views to a few high-confidence hypotheses and does not require 2D floorplans or low-level annotations as in LASER [10].

-

Stage 3: Circular Feature ExtractionWe compute rotation-invariant circular descriptors for the query (and later, for each candidate viewport):

- Extract a dense feature map from a pretrained ResNet-50 [39] backbone.

- Transform into polar coordinates, sampling M rings and N points per ring ( and ).

- Apply average and max pooling per ring to form D-dimensional vectors ().

- Concatenate across rings and L2-normalize.

This stage corresponds to Figure 2 step (c) and produces a compact, rotation-agnostic signature that captures global layout, crucial for disambiguating visually similar scenes. -

Stage 4: Pose Re-rankingFinally, as can be seen in Figure 2 step (d), each candidate from Stage 1 is re-rendered and encoded into a circular descriptor. Cosine similarity to the query descriptor is computed, and candidates are re-ranked. Unlike SPVLoc’s correlation-based refinement, which assumes top-1 correctness, our Bayesian combination allows lower-ranked but correct candidates to surface. This avoids failure modes where initial retrieval bias dominates refinement.

4. Experimental Evaluation

4.1. Baselines

4.2. Dataset

4.3. Model Training

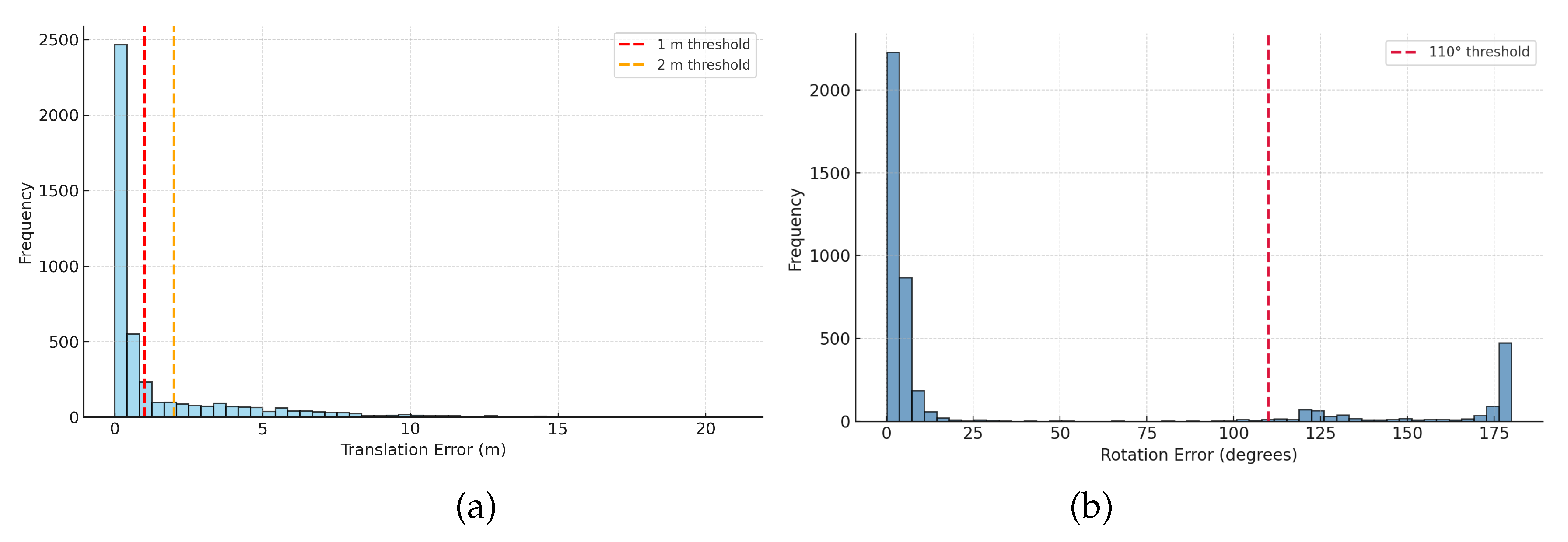

4.4. Inference Results.

5. Discussion and Limitation

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Taira, H.; Okutomi, M.; Sattler, T.; Cimpoi, M.; Pollefeys, M.; Sivic, J.; Pajdla, T.; Torii, A. InLoc: Indoor Visual Localization with Dense Matching and View Synthesis. In Proceedings of the Proceedings IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), [arXiv:cs.CV/1803.10368]. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Fidler, S.; Urtasun, R. Lost Shopping! Monocular Localization in Large Indoor Spaces. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), December 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Acharya, D.; Ramezani, M.; Khoshelham, K.; Winter, S. BIM-Tracker: A model-based visual tracking approach for indoor localisation using a 3D building model. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2019, 150, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Fan, G.; Roberts, E.; Steven, H.J. A Transfer Learning-Based Smart Homecare Assistive Technology to Support Activities of Daily Living for People with Mild Dementia. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 23rd International Conference on Bioinformatics and Bioengineering (BIBE); 2023; pp. 359–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triggs, B.; McLauchlan, P.F.; Hartley, R.I.; Fitzgibbon, A.W. Bundle adjustment—a modern synthesis. In Proceedings of the International workshop on vision algorithms. Springer; 1999; pp. 298–372. [Google Scholar]

- Snavely, N.; Seitz, S.; Szeliski, R. Photo tourism: Exploring photo collections in 3D. ACM Transactions on Graphics (2006) 2006, 25, 835–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, A.; Grimes, M.; Cipolla, R. PoseNet: A Convolutional Network for Real-Time 6-DOF Camera Relocalization, 2016, [arXiv:cs.CV/1505.07427]. arXiv:cs.CV/1505.07427].

- Zheng, J.; Zhang, J.; Li, J.; Tang, R.; Gao, S.; Zhou, Z. Structured3D: A Large Photo-realistic Dataset for Structured 3D Modeling. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of The European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV); 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gard, N.; Hilsmann, A.; Eisert, P. SPVLoc: Semantic Panoramic Viewport Matching for 6D Camera Localization in Unseen Environments. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision – ECCV 2024: 18th European Conference on Computer Vision, Proceedings, Part LXXIII, Cham; 2024; pp. 398–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, Z.; Khosravan, N.; Bessinger, Z.; Narayana, M.; Kang, S.B.; Dunn, E.; Boyadzhiev, I. LASER: LAtent SpacE Rendering for 2D Visual Localization, 2023, arXiv:cs.CV/2204.00157].

- Cruz, S.; Hutchcroft, W.; Li, Y.; Khosravan, N.; Boyadzhiev, I.; Kang, S.B. Zillow Indoor Dataset: Annotated Floor Plans With 360º Panoramas and 3D Room Layouts. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), June 2021, pp. 2133–2143.

- Torii, A.; Sivic, J.; Pajdla, T.; Okutomi, M. Visual Place Recognition with Repetitive Structures. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2013; pp. 883–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausler, S.; Garg, S.; Xu, M.; Milford, M.; Fischer, T. Patch-NetVLAD: Multi-Scale Fusion of Locally-Global Descriptors for Place Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2021; pp. 14136–14147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarlin, P.E.; Cadena, C.; Siegwart, R.; Dymczyk, M. From Coarse to Fine: Robust Hierarchical Localization at Large Scale. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2019; pp. 12708–12717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, D.G. Distinctive image features from scale-invariant keypoints. International journal of computer vision 2004, 60, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bay, H.; Ess, A.; Tuytelaars, T.; Van Gool, L. Speeded-Up Robust Features (SURF). Computer Vision and Image Understanding 2008, 110, 346–359, Similarity Matching in Computer Vision and Multimedia,. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rublee, E.; Rabaud, V.; Konolige, K.; Bradski, G. ORB: An efficient alternative to SIFT or SURF. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Computer Vision; 2011; pp. 2564–2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leutenegger, S.; Chli, M.; Siegwart, R.Y. BRISK: Binary Robust invariant scalable keypoints. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Computer Vision; 2011; pp. 2548–2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Zhou, L.; Bai, X.; Chen, H.; Zhang, J.; Yao, Y.; Li, S.; Fang, T.; Quan, L. ASLFeat: Learning Local Features of Accurate Shape and Localization. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2020; pp. 6588–6597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischler, M.A.; Bolles, R.C. Random Sample Consensus: A Paradigm for Model Fitting with Applications to Image Analysis and Automated Cartography. In Readings in Computer Vision; Fischler, M.A., Firschein, O., Eds.; Morgan Kaufmann: San Francisco (CA), 1987; pp. 726–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepetit, V.; Moreno-Noguer, F.; Fua, P. EP n P: An accurate O (n) solution to the P n P problem. International journal of computer vision 2009, 81, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard-Jenkins, H.; Ruiz-Sarmiento, J.R.; Prisacariu, V.A. Lalaloc: Latent layout localisation in dynamic, unvisited environments. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2021, ppp. 10107–10116.

- Howard-Jenkins, H.; Prisacariu, V.A. Lalaloc++: Global floor plan comprehension for layout localisation in unvisited environments. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision. Springer; 2022; pp. 693–709. [Google Scholar]

- Salas-Moreno, R.F.; Newcombe, R.A.; Strasdat, H.; Kelly, P.H.; Davison, A.J. Slam++: Simultaneous localisation and mapping at the level of objects. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2013, pp. 1352–1359.

- Engel, J.; Schöps, T.; Cremers, D. LSD-SLAM: Large-scale direct monocular SLAM. In Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision. Springer; 2014; pp. 834–849. [Google Scholar]

- Mur-Artal, R.; Montiel, J.M.M.; Tardós, J.D. ORB-SLAM: A Versatile and Accurate Monocular SLAM System. IEEE Transactions on Robotics 2015, 31, 1147–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mur-Artal, R.; Tardos, J.D. ORB-SLAM2: An Open-Source SLAM System for Monocular, Stereo, and RGB-D Cameras. IEEE Transactions on Robotics 2017, 33, 1255–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whelan, T.; Salas-Moreno, R.F.; Glocker, B.; Davison, A.J.; Leutenegger, S. ElasticFusion: Real-time dense SLAM and light source estimation. The International Journal of Robotics Research 2016, 35, 1697–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormac, J.; Handa, A.; Davison, A.; Leutenegger, S. SemanticFusion: Dense 3D semantic mapping with convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA); 2017; pp. 4628–4635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mildenhall, B.; Srinivasan, P.P.; Tancik, M.; Barron, J.T.; Ramamoorthi, R.; Ng, R. NeRF: Representing Scenes as Neural Radiance Fields for View Synthesis, 2020, arXiv:cs.CV/2003.08934].

- Dai, A.; Ritchie, D.; Bokeloh, M.; Reed, S.; Sturm, J.; Nießner, M. ScanComplete: Large-Scale Scene Completion and Semantic Segmentation for 3D Scans. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2018; pp. 4578–4587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahmbhatt, S.; Gu, J.; Bansal, K.; Darrell, T.; Hwang, J.; Adelson, E.H. Geometry-Aware Learning of Maps for Camera Localization. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, R.; Wang, S.; Wen, H.; Handa, A.; Nieuwenhuis, D.; Davison, A.; Leutenegger, S. VidLoc: A Deep Spatio-Temporal Model for 6-DoF Video-Clip Relocalization. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tateno, K.; Tombari, F.; Laina, I.; Navab, N. Cnn-slam: Real-time dense monocular slam with learned depth prediction. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2017, pp. 6243–6252.

- Brachmann, E.; Krull, A.; Nowozin, S.; Shotton, J.; Michel, F.; Gumhold, S.; Rother, C. DSAC — Differentiable RANSAC for Camera Localization. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2017; pp. 2492–2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, C.; Pizzoli, M.; Scaramuzza, D. SVO: Fast semi-direct monocular visual odometry. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA); 2014; pp. 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Le, Q.V. EfficientNet: Rethinking Model Scaling for Convolutional Neural Networks, 2020, [arXiv:cs.LG/1905.11946]. arXiv:cs.LG/1905.11946].

- Huang, G.; Liu, Z.; van der Maaten, L.; Weinberger, K.Q. Densely Connected Convolutional Networks, 2018. arXiv:cs.CV/1608.06993].

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, C.R.; Yi, L.; Su, H.; Guibas, L.J. PointNet++: Deep Hierarchical Feature Learning on Point Sets in a Metric Space. CoRR 2017, abs/1706.02413, [1706.02413].

- Wang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Liu, Z.; Sarma, S.E.; Bronstein, M.M.; Solomon, J.M. Dynamic Graph CNN for Learning on Point Clouds. CoRR 2018, abs/1801.07829, [1801.07829].

- Zhou, Q.Y.; Park, J.; Koltun, V. Open3D: A Modern Library for 3D Data Processing, 2018. arXiv:cs.CV/1801.09847].

- Askar, C.; Sternberg, H. Use of Smartphone Lidar Technology for Low-Cost 3D Building Documentation with iPhone 13 Pro: A Comparative Analysis of Mobile Scanning Applications. Geomatics 2023, 3, 563–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Yu, Y.; Xu, J.; Ni, F.; Le, X. PF-Net: Point Fractal Network for 3D Point Cloud Completion, 2020. arXiv:cs.CV/2003.00410].

| Method | (%) | (%) | (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| LASER (from [9]) | 8.69 | 67.01 | 80.90 |

| SPVLoc | 12.25 | 59.49 | 98.21 |

| SPVLoc – Refined | 22.07 | 73.80 | 98.21 |

| Ours | 12.86 | 63.42 | 99.14 |

| Ours – Refined | 21.82 | 73.62 | 99.14 |

| (cm) | () | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method | Min | Max | Mean | Median | Min | Max | Mean | Median |

| Baseline | 0.406 | 2089.24 | 149.93 | 32.38 | 0.040 | 179.99 | 38.91 | 3.57 |

| Baseline – refined | 1.210 | 2069.46 | 131.73 | 18.47 | 0.046 | 179.99 | 36.33 | 2.97 |

| Ours | 0.406 | 2089.24 | 116.54 | 29.17 | 0.040 | 179.99 | 35.98 | 3.44 |

| Ours – refined | 0.406 | 2069.47 | 103.07 | 19.41 | 0.027 | 179.99 | 30.20 | 2.56 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).