1. Introduction

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection has transitioned into a chronic condition due to the widespread use of antiretroviral therapy (ART), which has significantly improved survival. As life expectancy increases, people living with HIV (PLHIV) experience a higher burden of non–AIDS-related comorbidities, particularly cardiovascular disease (CVD), which is now a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in this population [

1,

2]. Despite extensive research, the mechanisms underlying the elevated cardiovascular risk in PLHIV remain incompletely understood, and evidence indicates that this population is at increased risk of developing subclinical atherosclerosis, even after adjustment for traditional risk factors [

3,

4].

Lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)] is a low-density lipoprotein (LDL)-like particle composed of apolipoprotein(a) covalently bound to apolipoprotein B-100. It carries proatherogenic and proinflammatory properties and is recognized as an independent causal risk factor for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease [

5,

6]. Unlike LDL cholesterol (LDL-C), its plasma concentrations remain stable throughout life and are not significantly modified by lifestyle or standard lipid-lowering therapies.

Lp(a) concentrations are predominantly genetically determined (>90%) and influenced by ethnicity, being higher in individuals of African descent [

7,

8]. Lp(a) levels ≥125 nmol/L are present in approximately 20–25% of the general population and are associated with a two- to three-fold increased risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, and calcific aortic stenosis [

9,

10]. International guidelines now recommend measuring Lp(a) at least once in adulthood, especially in individuals with premature cardiovascular disease or high residual risk despite optimal lipid-lowering therapy [

9].

In people living with HIV, persistent immune activation, chronic inflammation, and endothelial dysfunction are well-described features even in the setting of sustained viral suppression, which may potentiate the proatherogenic and proinflammatory properties of Lp(a) [

8]. Recent studies have reported higher Lp(a) levels in PLHIV compared with HIV-negative individuals and have shown inverse associations with coronary endothelial function [

11,

12], as well as increased perivascular inflammation on coronary imaging [

13]. These findings suggest that the impact of Lp(a) on cardiovascular risk may be amplified or mechanistically distinct in the context of HIV infection, supporting the rationale for targeted investigation using advanced cardiovascular imaging modalities.

To date, no studies have simultaneously examined the relationship between Lp(a) levels, HIV infection, and coronary plaque morphology assessed by coronary computed tomography angiography. Moreover, the potential modulation of Lp(a) levels by long-term antiretroviral therapy remains insufficiently explored. By integrating clinical, biochemical, and imaging parameters, the present study aims to provide novel insights into the role of Lp(a) in subclinical atherosclerosis among people living with HIV.

The primary objective of this study was to determine the relationship between Lp(a) levels and HIV-related clinical variables and validated cardiovascular risk scores in a contemporary cohort of PLHIV receiving stable ART. A secondary objective was to examine the association between Lp(a) levels and the presence of subclinical coronary artery disease, assessed by coronary computed tomography angiography (CTA).

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design and Population

This single-center, cross-sectional study consecutively enrolled PLHIV from the monographic consultation at Hospital Gómez Ulla in Madrid, who met all inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria were: age ≥40 years, stable antiretroviral therapy for more than 6 months, suppressed HIV viral load (<50 copies/mL), and provision of written informed consent. Exclusion criteria included a history of cerebrovascular and/or cardiovascular events, a diagnosis of type 1 diabetes mellitus (DM), or type 2 DM of more than 10 years’ duration (or shorter duration in the presence of additional cardiovascular risk factors). Recruitment began on March 22, 2022, and continued for one year. All participants had Lp(a) levels measured in a follow-up blood sample collected after enrollment. Cardiovascular risk was assessed using the Framingham Risk Score, and those with a score ≥10% were offered coronary CTA, provided there were no contraindications to the test (e.g., renal insufficiency, contrast agent allergy, or refusal to provide specific informed consent for the procedure).

Study Variables

Demographic data, HIV-related variables, ART information, traditional cardiovascular risk factors, statin use, and lipid profile parameters were collected for all participants.

Importantly, Lp(a) levels were measured systematically in all study participants as part of the study protocol. This approach allowed for an unbiased evaluation of Lp(a) distribution within the cohort and facilitated estimation of its prevalence among PLHIV with virological suppression. Lp(a) levels were determined using a particle-enhanced immunoturbidimetric assay (Roche Diagnostics), with results initially expressed in nmol/L according to current recommendations10 (≥75 nmol/L: moderately elevated; and ≥125 nmol/L: highly elevated).

For all patients, the following cardiovascular risk scores were calculated: Framingham Risk Score, SCORE2, REGICOR, and the Data Collection on Adverse Events of Anti-HIV Drugs (D:A:D) equation. Although SCORE2 and REGICOR are contemporary tools widely used in European populations, these models are not validated specifically in PLHIV. The D:A:D score was calculated when sufficient clinical data were available; however, it could not be applied in all participants due to missing historical variables, particularly among long-term survivors. Therefore, for consistency and comparability across the cohort, the Framingham Risk Score—which has been previously used in HIV research—was selected to define participants at moderate-to-high risk (≥10%) eligible for coronary computed tomography angiography (CTA).

Coronary Computed Tomography Angiography

All patients initially underwent ECG-synchronized, non-contrast computed tomography for coronary artery calcium (CAC) scoring, using standardized acquisition parameters (detector collimation: 64 × 1.5 mm; tube voltage: 120 kV). The Agatston score was calculated to assess baseline atherosclerotic burden. A score ≥400 was used to identify individuals at high cardiovascular risk. Subsequently, contrast-enhanced CTA was performed using a 124-detector Philips scanner.

An iodinated contrast agent (400 mg I/mL) was administered at a flow rate of 5 mL/s, followed by a 40 mL saline flush. Automatic bolus tracking was employed, with a region of interest (ROI) placed in the ascending aorta and a threshold of 100 Hounsfield units (HU) used to trigger image acquisition during the arterial phase. The contrast volume ranged from 60 to 100 mL, adjusted according to body weight and scan duration. Image post-processing was performed using IntelliSpace Portal (Philips), a dedicated client-server platform. Curved multiplanar reformations (cMPR) and interactive oblique reconstructions were generated for detailed evaluation of coronary plaques and luminal morphology.

Coronary artery stenosis was qualitatively assessed according to the Coronary Artery Disease Reporting and Data System (CAD-RADS) and graded on a scale from 0 to 5: 0 (no visible stenosis), 1 (minimal, <25%), 2 (mild, 25–49%), 3 (moderate, 50–69%), 4 (severe, ≥70%), and 5 (total occlusion, 100%). Stenoses were evaluated segment by segment using the modified American Heart Association (AHA) 17-segment coronary artery model. Plaque morphology was classified into the following categories: calcified plaque, predominantly calcified plaque, mixed plaque, predominantly non-calcified plaque, and non-calcified plaque. Qualitative assessment of high-risk plaque features included evaluation for low-attenuation plaque, Napkin-Ring Sign (NRS), punctate calcification and the remodeling index (RI). Low-attenuation plaque was defined as non-calcified plaque with attenuation <130 Hounsfield units (HU). The NRS was identified as a hypoattenuating central area surrounded by a thin high-attenuation rim, indicative of positive remodeling and the presence of a necrotic core. Punctate calcifications, defined as calcifications <3 mm in diameter within the plaque, suggest microcalcifications associated with plaque instability. A RI >1.1 was considered indicative of positive vascular remodeling and was calculated as the ratio of the maximum transverse luminal diameter at the lesion site to the diameter of the nearest reference segment (proximal or distal).

A coronary lesion was classified as a vulnerable plaque when it exhibited at least two of the following features: a lipid-rich core (low-attenuation plaque), positive remodeling, and spotty calcification. This definition aligns with the criteria for vulnerable plaque proposed by other authors [

14].

All analyses were conducted independently by cardiovascular imaging specialists with expertise in coronary computed tomography. Standardized methodologies ensured accurate characterization of stenosis severity and reliable identification of high-risk plaque features.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were conducted using the R statistical software, version 4.4.1 (R Core Team, 2024).

Continuous variables were tested for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test and expressed as median values and interquartile ranges (IQR), given the non-parametric distribution of Lp(a) and other variables. Categorical variables were described using relative frequencies (percentages). Differences in Lp(a) levels were analyzed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for binary variables (e.g., sex, statin use) and the Kruskal–Wallis test for comparisons across multiple groups (e.g., race, ART regimen). Spearman correlation coefficients were calculated to assess associations between Lp(a) and clinical or cardiovascular risk variables (Framingham, SCORE2, REGICOR, and D:A:D risk scores). A two-sided p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical and Legal Aspects

All participants provided written informed consent prior to enrollment in the study. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the participating institution before recruitment commenced. Furthermore, the study adhered to Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki principles, ensured participant anonymity, and the data collected were processed in accordance with current legislation on data protection (Organic Law 3/2018 of December 5 and EU Regulation 679/2016).

3. Results

The study included 69 participants with no known history of coronary artery disease or chest pain. The mean age was 54 years; 81% were male, and the predominant ethnicity was Caucasian (50.7%), followed by Hispanic (39.1%). Dyslipidemia was present in 49% of participants, 33% were active smokers, 30% had hypertension and 13% had type 2 diabetes. Only two participants reported a family history of premature cardiovascular disease (

Table 1).

The median duration of ART was 11.5 years (IQR 8–14). The mean current CD4+ T-cell count was 642 cells/μL, and the mean CD4 nadir was 338 cells/μL. Most participants (69.5%) were receiving an ART regimen containing an integrase strand transfer inhibitor (INSTI). A total of 35% had previously received a protease inhibitor (PI), and 17.4% were receiving a PI at baseline. Additionally, 43% of participants were on statin therapy.

The median Lp(a) level was 23.4 nmol/L (IQR: 8.24–81.6), and the mean level was 66.7 nmol/L. Elevated Lp(a) levels ≥75 nmol/L were present in 29% of participants, and 23% had levels ≥125 nmol/L. Among the two patients with a family history of premature cardiovascular disease, Lp(a) levels were 227 nmol/L and 28 nmol/L, respectively.

No significant differences in Lp(a) levels were observed across demographic, clinical, or HIV-related variables, including statin use. A non-significant inverse trend was found between Lp(a) levels and ART duration (r = –0.209; p = 0.08). Similarly, no significant associations were identified between Lp(a) and cardiovascular risk estimated by validated scores, nor with current CD4 count or CD4 nadir (

Table 2), indicating that Lp(a) levels were not correlated with immunological status in this cohort.

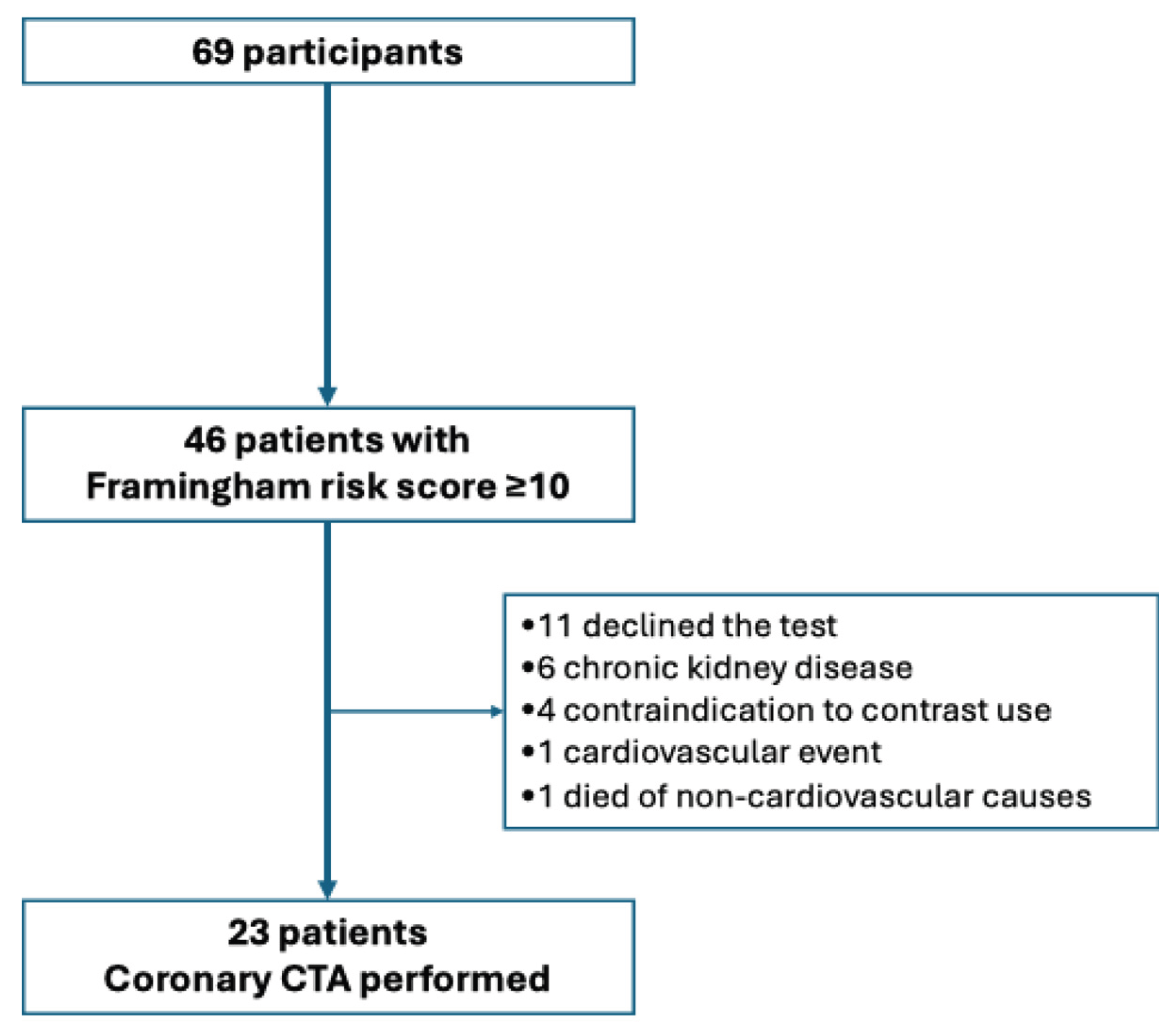

Of the 46 patients with a Framingham score ≥10%, 23 underwent coronary CTA.

Figure 1 illustrates the patient selection flow for those who underwent coronary CT angiography, as well as the reasons for patients who did not undergo the procedure. Among these participants, 52.2% had evidence of coronary stenosis.

Table 3 shows the distribution of coronary lesions by arterial segment, along with their corresponding degrees of stenosis. The proximal left anterior descending artery (LAD) was the most frequently affected segment (n = 8), followed by the mid-LAD and proximal circumflex (Cx) segments (n = 5 each). Mild stenosis (<25%) was predominant. One participant showed complete (100%) occlusion of the mid-LAD, which was successfully revascularized.

Among participants with Lp(a) ≥125 nmol/L, 4 underwent CTA; among those with Lp(a) 75–124 nmol/L, 1 underwent CTA. Of these 5 individuals, 4 (80%) exhibited at least two high-risk plaque features. In contrast, among participants with Lp(a) <75 nmol/L, 6 of 16 (37.5%) demonstrated plaque vulnerability markers. Although this difference did not reach statistical significance (Fisher’s exact test p = 0.149), a higher proportion of vulnerable plaques was observed in those with elevated Lp(a). No correlation was found between Lp(a) levels and coronary artery calcium score (r = –0.03; p = 0.90).

4. Discussion

In this cross-sectional study of virologically suppressed PLHIV with no history of cardiovascular disease, we observed a non-significant inverse trend between Lp(a) levels and the duration of ART. Importantly, this association appeared to be independent of immune status, as no significant correlations were found with current CD4+ T-cell count or CD4 nadir. Furthermore, Lp(a) levels did not differ according to statin use, consistent with previous evidence indicating that statins have minimal or no effect on Lp(a) concentrations. These findings suggest that the observed trend may be related to specific ART regimens, particularly those based on integrase strand transfer inhibitors, rather than to immunological recovery or lipid-lowering therapy.

Previous studies evaluating the relationship between HIV infection, antiretroviral therapy, and Lp(a) levels have reported heterogeneous findings. In a study conducted in the pre-ART era, Enkhmaa et al. [

12] observed that HIV-infected African-American women not receiving treatment had lower Lp(a) concentrations compared with HIV-negative controls, whereas levels increased following ART initiation. In contrast, Kikuchi et al. [

11] reported higher Lp(a) levels in virologically suppressed PLHIV than in HIV-negative individuals, suggesting that chronic treated HIV infection may be associated with elevated Lp(a). The mean Lp(a) level in our cohort (approximately 67 nmol/L) was slightly lower than that reported by Kikuchi et al., likely reflecting the lower proportion of individuals of African descent in our cohort. Furthermore, findings from the SPIRAL clinical trial [

15] demonstrated that switching from protease inhibitor–based regimens to raltegravir resulted in a reduction in Lp(a), supporting the hypothesis that ART regimen composition, rather than HIV infection itself, may influence Lp(a) metabolism.

The biological plausibility of our findings is supported by the known proatherogenic and proinflammatory properties of Lp(a), which may be amplified in the setting of chronic HIV infection. Persistent immune activation, even in virologically suppressed individuals, contributes to endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and increased expression of cellular adhesion molecules, all of which facilitate the arterial wall deposition of Lp(a). Furthermore, Lp(a) carries oxidized phospholipids and apolipoprotein(a), which stimulate proinflammatory pathways and impair fibrinolysis [

10], thereby promoting the development of high-risk, unstable plaques. These mechanisms may contribute to accelerated atherosclerosis in PLHIV and could help explain the trend we observed toward a greater prevalence of vulnerable plaque features in individuals with elevated Lp(a). Collectively, these findings highlight the importance of evaluating the association between Lp(a) concentrations and coronary plaque morphology in this population.

In the subgroup of participants at moderate-to-high estimated cardiovascular risk who underwent coronary CTA, a higher proportion of individuals with elevated Lp(a) levels exhibited vulnerable plaque features, even in the absence of significant obstructive disease. Although this association did not reach statistical significance, likely due to the limited sample size, the observed pattern is consistent with findings from non-HIV populations. In the PROMISE trial [

16], elevated Lp(a) levels ≥125 nmol/L were associated with both obstructive coronary artery disease and high-risk plaque morphology in asymptomatic individuals. Similarly, Dai et al. [

17] demonstrated that patients with Lp(a) concentrations >125 nmol/L and multiple plaque vulnerability features had a markedly increased risk of major adverse cardiovascular events. Our observations extend these findings to PLHIV, a population in whom chronic inflammation and immune dysregulation may further potentiate Lp(a)-mediated plaque instability.

Beyond its role as a causal and genetically determined lipid biomarker, Lp(a) is increasingly recognized as a therapeutic target, with several RNA-based agents currently in advanced clinical development demonstrating reductions of more than 80% in plasma Lp(a) concentrations [

18,

19]. Given the elevated prevalence of Lp(a) observed in our cohort and the higher proportion of vulnerable plaque features among individuals with elevated levels, our findings underscore the potential relevance of incorporating Lp(a) into cardiovascular risk stratification algorithms for PLHIV. This approach may be particularly important in the era of emerging therapies specifically designed to lower Lp(a), which could offer novel preventive strategies for high-risk patients with HIV infection.

This study has several limitations. It was conducted in a single center with a relatively small sample size, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. In particular, the number of participants with elevated Lp(a) who underwent coronary CTA was small, reducing the statistical power to detect associations with plaque vulnerability features; therefore, these results should be interpreted as exploratory. In addition, the absence of an HIV-negative control group precludes assessment of whether the relationship between Lp(a) and subclinical coronary atherosclerosis is specific to HIV infection or reflects the established proatherogenic effects of Lp(a) observed in the general population. Future multicenter studies with larger and more diverse populations are needed to validate these findings and to determine the clinical utility of incorporating Lp(a) into cardiovascular risk stratification algorithms for PLHIV, particularly in light of emerging therapies specifically designed to lower Lp(a). Additionally, future studies integrating apolipoprotein B measurements may help further refine residual atherogenic risk in this population.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this cross-sectional study of virologically suppressed individuals living with HIV identified a non-significant inverse trend between Lp(a) concentrations and the duration of antiretroviral therapy, suggesting a potential modulatory effect of long-term treatment exposure on Lp(a) metabolism. Furthermore, in the subgroup of participants at moderate-to-high cardiovascular risk, the prevalence of coronary plaque vulnerability features was higher among those with elevated Lp(a) levels (≥75 nmol/L), highlighting a possible link between Lp(a) and subclinical atherosclerosis in this population.

Taken together, these findings support the relevance of Lp(a) as a potential biomarker for cardiovascular risk stratification in people living with HIV. Given the proatherogenic and proinflammatory properties of Lp(a), its measurement may contribute to the identification of individuals at increased risk despite viral suppression. Future prospective studies are needed to confirm these observations, elucidate underlying mechanisms, and determine whether targeted Lp(a)-lowering therapies could improve cardiovascular outcomes in this high-risk population.

Author Contributions

Study conceptualization: DJRT, MME; Methodology and study protocol: CRA; Patient inclusion: TMF, MME; Data collection: CRA, DJRT, MR; Lipoprotein(a) measurements: BTA, JEGS; Data analysis: CRA, DJRT, JJRJ; Manuscript writing – original draft: CRA; Manuscript writing – review and editing: DJRT, MME; Supervision: DJRT, MME; Study protocol approval: SAA, FJMN, ELS. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Funding for the reagents required to determine lp(a) levels was obtained through the award granted in the Cátedra-RIS-UAH-Gilead call for research project funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Hospital Gómez Ulla (protocol code 8/22 and date of approval 16th February 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Individual participant data will be made available on request to the corresponding authors. After approval of a proposal, data will be shared through a secure online platform.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

References

- Shah ASV, Stelzle D, Lee KK, Beck EJ, Alam S, Clifford S, et al. Global burden of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in people living with HIV. Circulation. 2018;138(11):1100–1112. [CrossRef]

- Smith CJ, Ryom L, Weber R, Reynes J, d’Arminio Monforte A, El-Sadr W, et al. Trends in underlying causes of death in people with HIV from 1999 to 2011 (D:A:D): A multicohort collaboration. Lancet. 2014;384(9939):241–248. [CrossRef]

- Post WS, Budoff M, Kingsley L, Palella FJ, Witt MD, Li X, et al. Associations between HIV infection and subclinical coronary atherosclerosis. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(7):458–467. [CrossRef]

- D’Ascenzo F, Cerrato E, Calcagno A, Mameli A, Tedeschi A, Omedè P, et al. High prevalence at computed coronary tomography of non-calcified plaques in asymptomatic HIV patients treated with HAART: A meta-analysis Atherosclerosis. 2015;240(1):197–204. [CrossRef]

- Pearson GJ, Thanassoulis G, Anderson TJ, Barry AR, Couture P, Dayan N, et al. 2021 Canadian Cardiovascular Society Guidelines for the Management of Dyslipidemia for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in Adults. Can J Cardiol. 2021;37(8):1129–1150. [CrossRef]

- Mach F, Baigent C, Catapano AL, Koskinas KC, Casula M, Badimon L, et al. 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(1):111–188. [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Soffer, G. The impact of race and ethnicity on lipoprotein(a) levels and cardiovascular risk. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2021;32(3):163–166. [CrossRef]

- Dzobo KE, Kraaijenhof JM, Stroes ESG, Nurmohamed NS, Kroon J, Tsimikas S, et al. Lipoprotein(a): An underestimated inflammatory mastermind. Atherosclerosis. 2022;349:101–109. [CrossRef]

- Duarte Lau F, Giugliano RP. Lipoprotein(a) and its significance in cardiovascular disease: A review. JAMA Cardiol. 2022;7(7):760–769. [CrossRef]

- Kronenberg F, Mora S, Stroes ESG, Ference BA, Arsenault BJ, Berglund L, et al. Lipoprotein(a) in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and aortic stenosis: a European Atherosclerosis Society consensus statement. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(39):3925–3946. [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi DS, Kwapong YA, Schär M, Weiss RG, Sun K, Brown TT, et al. Lipoprotein(a) is elevated and inversely related to coronary endotelial function in people with HIV. J Am Heart Assoc. 2024;13(23):e035975. [CrossRef]

- Enkhmaa B, Anuurad E, Zhang W, Li CS, Kaplan R, Lazar J, et al. Lipoprotein(a) and HIV: Allele-specific apolipoprotein(a) levels predict carotid intima-media thickness in HIV-infected young women in the Women’s Interagency HIV Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2017;37(5):997–1004. [CrossRef]

- Zisman E, Hossain M, Funderburg NT, Christenson R, Jeudy J, Burrowes S, et al. Association of lipoprotein(a) with peri-coronary inflammation in persons with and without HIV. J Clin Lipidol. 2024;18(3):e430–e443. [CrossRef]

- Chang HJ, Lin FY, Lee SE, Andreini D, Bax J, Cademartiri F, et al. Coronary atherosclerotic precursors of acute coronary syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(22):2511–2522. [CrossRef]

- Saumoy M, Sánchez-Quesada JL, Martínez E, Llibre JM, Ribera E, Knobel H, et al. LDL subclasses and lipoprotein-phospholipase A2 activity in suppressed HIV infected patients switching to raltegravir: Spiral substudy. Atherosclerosis. 2012;225(1):200–207. [CrossRef]

- O’Toole T, Shah NP, Giamberardino SN, Kwee LC, Voora D, McGarrah RW, et al. Association between lipoprotein(a) and obstructive coronary artery disease and high-risk plaque: insights from the PROMISE Trial. Am J Cardiol. 2024;231:40–47. [CrossRef]

- Dai N, Chen Z, Zhou F, Zhou Y, Hu N, Duan S, et al. Association of lipoprotein(a) with coronary-computed tomography angiography-assessed high-risk coronary disease attributes and cardiovascular outcomes. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2022;15(12):e014611.

- Nissen, S. E., Linnebjerg, H., Shen, X., Wolski, K., Ma, X., Lim, S., et al. Lepodisiran, an extended-duration short interfering RNA targeting lipoprotein(a): a randomized dose-ascending clinical trial. JAMA. 2025. 330(21), 2075–2083. [CrossRef]

- Graham, M. J., Viney, N., Crooke, R. M., & Tsimikas, S. Antisense inhibition of apolipoprotein (a) to lower plasma lipoprotein (a) levels in humans. Journal of lipid research. 2016. 57(3), 340–351. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).