Submitted:

12 November 2025

Posted:

13 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical and Methodological Foundations

2.1. The Philosophical Approach: Set as a Holistic State

2.2. The Two-Phase Structure of the Experiment

- The Fixation Phase (Set-Inducing Trials): Designed to establish the set through repetitive exposure to a constant stimulus relationship, a process of implicit, procedural learning (Seger, 2018) akin to developing a "perceptual expectation" (Kok et al., 2017).

- The Phase of Objectification (Critical Trials): Reveals the set's presence by presenting identical stimuli. The resulting contrast illusion is empirical proof of the set's power (Cheng & Tseng, 2021), demonstrating that perception is actively constructed by the brain's pre-activated models, a core tenet of predictive processing (Friston, 2010).

2.3. Key Diagnostic Parameters

- Sensitization to Set (Speed of Formation): Reflects efficiency in implicit learning mechanisms (Ashby et al., 2010).

- Strength / Degree of Fixation (Persistence): A marker of cognitive rigidity, linked to prefrontal cortex function (Dajani & Uddin, 2015).

- Lability / Rigidity of Set (Adaptability): Indicates cognitive flexibility, associated with prefrontal integrity (Dajani & Uddin, 2015).

| Parameter | Operational Definition | Cognitive Interpretation | Neural Correlate (Example) |

| Sensitization | Number of fixation trials needed for a stable illusion. | Efficiency of implicit learning. | Cortico-striatal circuits (Ashby et al., 2010) |

| Strength | Number of critical trials where the illusion persists. | Cognitive rigidity; resistance to updating models. | Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex (Dajani & Uddin, 2015) |

| Lability | Speed of illusion extinction or set switching. | Cognitive flexibility; adaptability. | Anterior Cingulate Cortex (Cavanagh & Frank, 2014) |

3. Experimental Design and Modifications

3.1. The Classic Haptic Variant

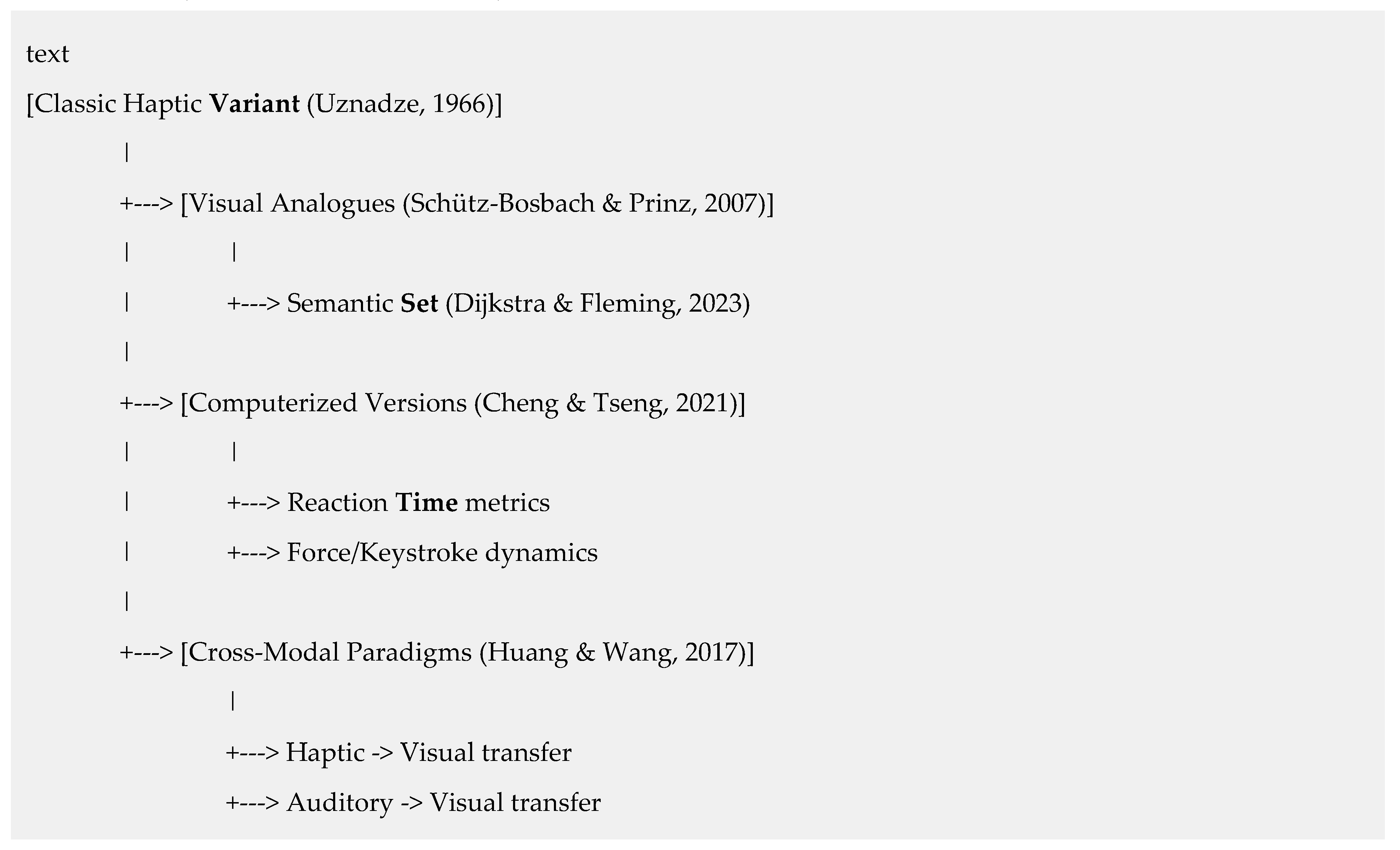

3.2. Modern Modifications and Paradigm Extensions

- Visual Analogues: Demonstrate domain-generality, producing a visual contrast illusion (Schütz-Bosbach & Prinz, 2007). Extended to semantic set (Dijkstra & Fleming, 2023).

- Computerized Versions: Enhance precision through millisecond-accurate reaction time measurement (Schütz-Bosbach & Prinz, 2007), objective motor metrics (Song & Nakayama, 2008), and perfect standardization (Cheng & Tseng, 2021).

- Cross-Modal Paradigms: Provide evidence for the amodal nature of set, showing transfer from haptic to visual perception (Huang & Wang, 2017), likely involving heteromodal association cortices (Driver & Noesselt, 2008).

4. Key Findings and Their Interpretation

4.1. The Universality of the Phenomenon

4.2. Individual Differences: From Cognitive Style to Neurological Signature

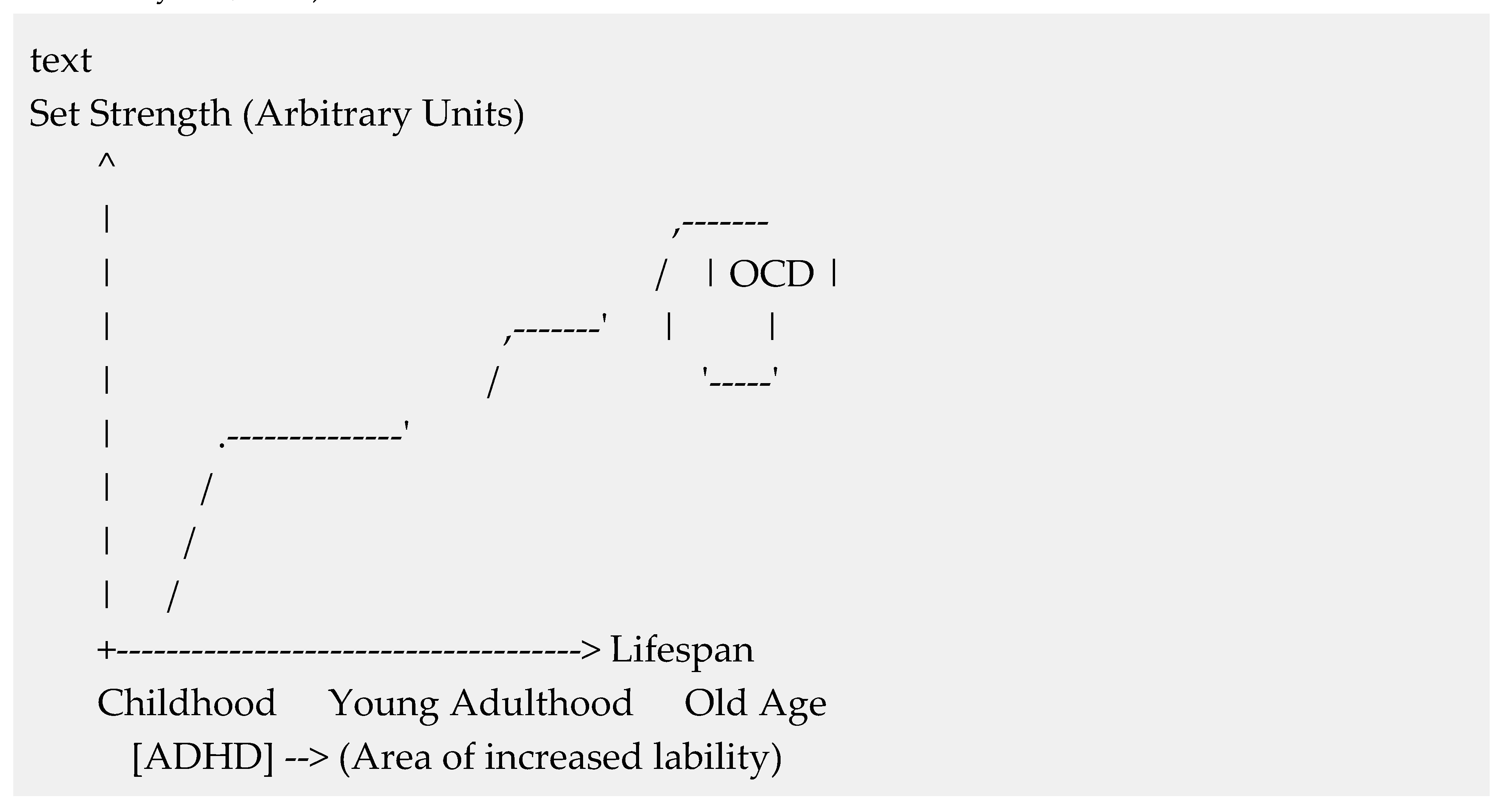

- "Strong" Set and Cognitive Rigidity: Persistent illusion is a marker of rigidity, linked to PFC function and observed in OCD and schizophrenia (Gómez-Ariza et al., 2017; Dajani & Uddin, 2015).

- "Weak" or Labile Set and Cognitive Flexibility: Rapid extinction indicates flexibility, but extreme lability can be pathological (e.g., ADHD, TBI) (Cheng & Tseng, 2021).

4.3. Diagnostic Potential in Applied Fields

- Clinical Psychology: Sensitive to cognitive dysregulation in schizophrenia (Sterzer et al., 2018), anxiety disorders (Gómez-Ariza et al., 2017), and Parkinson's disease (Ashby et al., 2010).

- Developmental Psychology: Trajectory mirrors brain maturation, from labile in childhood (Jolles & Crone, 2012) to rigid in aging (Tsvetkov et al., 2022).

- Sports and Professions: Assesses motor skill acquisition and cognitive-motor flexibility (Song & Nakayama, 2008).

5. Neurocognitive Correlates and Contemporary Interpretation

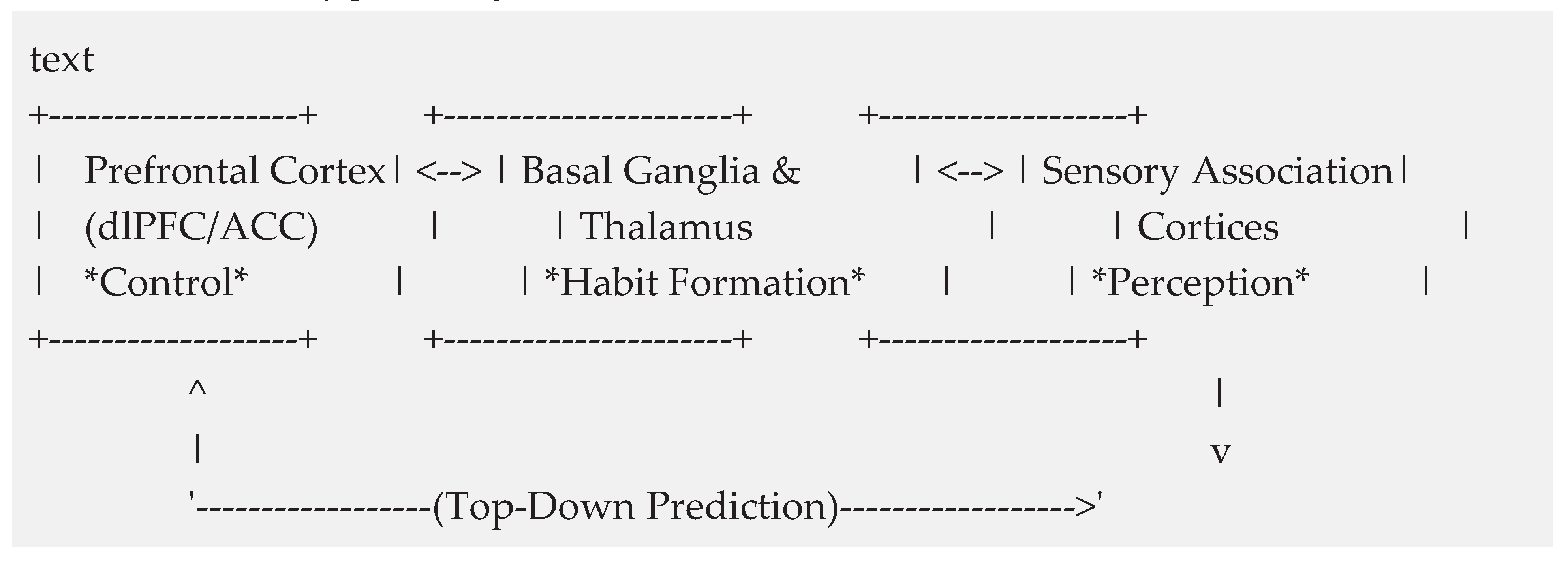

5.1. The Neurophysiological Substrate

- Basal Ganglia and Thalamus: Critical for the implicit habit learning and reinforcement of the set "stereotype" (Ashby et al., 2010; Seger, 2018).

- Prefrontal Cortex (PFC): The executive controller, particularly the dlPFC and ACC, which monitor conflict and inhibit the prepotent set response (Dajani & Uddin, 2015; Cavanagh & Frank, 2014).

- Sensory Association Cortices: The locus of perceptual integration, where top-down predictions modulate sensory processing to create the illusion (Kok et al., 2017; Friston, 2010).

5.2. Interpretation within Cognitive Psychology

- Implicit Learning and Procedural Memory: Set formation is a classic example of non-conscious knowledge acquisition (Réber, 2013; Seger, 2018).

- The Priming Effect: The set acts as a prolonged form of negative priming, biasing subsequent perception (Henson, 2003).

- A Cognitive Heuristic ("Anchoring"): The fixation phase establishes a powerful "perceptual anchor" that distorts subsequent judgments (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974).

| Uznadze's Concept | Modern Cognitive Framework | Key Reference |

| Set Formation | Implicit / Procedural Learning | Seger (2018) |

| Contrast Illusion | Predictive Coding / Perception as Inference | Friston (2010) |

| Set Persistence (Rigidity) | Deficits in Cognitive Control / Switching | Dajani & Uddin (2015) |

| Set as a prepared state | Priming (especially negative) | Henson (2003) |

| Fixation Phase | Establishment of a Cognitive "Anchor" | Tversky & Kahneman (1974) |

6. Discussion and Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Conclusions

6.2. Practical Conclusions

6.3. Promising Avenues for Future Research

- Elucidating Neurochemical Foundations: Probing the role of the dopaminergic and GABAergic systems using pharmacological challenges (Cools & D'Esposito, 2011; Ashby et al., 2010).

- Social and Affective Neuroscience of Set: Establishing "social sets" to study implicit bias and stereotyping (Amodio, 2019).

- Developing Interventions: Using the paradigm for cognitive training to enhance behavioral flexibility in aging and pathology (Katz et al., 2018).

References

- Amodio, D. M. (2019). Social cognition 2.0: An interactive memory systems account. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 23(1), 21–33. [CrossRef]

- Ashby, F. G., Turner, B. O., & Horvitz, J. C. (2010). Cortical and basal ganglia contributions to habit learning and automaticity. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 14(5), 208–215. [CrossRef]

- Bassin, M. V. (2021). The problem of the unconscious in the context of the theory of set by D.N. Uznadze. Psychology. Journal of the Higher School of Economics, 18(1), 315-331. [CrossRef]

- Brayanov, J. B., & Smith, M. A. (2010). Bayesian and "anti-Bayesian" biases in sensory integration for action and perception in the size-weight illusion. Journal of Neurophysiology, 103(3), 1518–1531. [CrossRef]

- Buckingham, G. (2014). Getting a grip on heaviness perception: a review of weight illusions and their probable causes. Experimental Brain Research, 232(6), 1623–1629. [CrossRef]

- Cavanagh, J. F., & Frank, M. J. (2014). Frontal theta as a mechanism for cognitive control. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 18(8), 414–421. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C. H., & Tseng, Y. J. (2021). The neural correlates of motor-based and cognitive-based implicit learning. NeuroImage, 235, 118000. [CrossRef]

- Cools, R., & D'Esposito, M. (2011). Inverted-U-shaped dopamine actions on human working memory and cognitive control. Biological Psychiatry, 69(12), e113–e125. [CrossRef]

- Dajani, D. R., & Uddin, L. Q. (2015). Demystifying cognitive flexibility: Implications for clinical and developmental neuroscience. Trends in Neurosciences, 38(9), 571–578. [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, N., & Fleming, S. M. (2023). Subjective signal strength distinguishes reality from imagination. Nature Communications, 14, 1627. [CrossRef]

- Driver, J., & Noesselt, T. (2008). Multisensory interplay reveals crossmodal influences on 'sensory-specific' brain regions, neural responses, and judgments. Neuron, 57(1), 11–23. [CrossRef]

- Friston, K. (2010). The free-energy principle: a unified brain theory? Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 11(2), 127–138. [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Ariza, C. J., Iglesias-Parro, S., García-López, L. J., Díaz-Castela, M. M., Espinosa-Fernández, L., & Muela, J. A. (2017). Cognitive flexibility and attentional bias in children and adolescents with anxiety disorders. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 55, 66–73. [CrossRef]

- Hassin, R. R. (2013). Yes it can: On the functional abilities of the human unconscious. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 8(2), 195–207. [CrossRef]

- Henson, R. N. (2003). Neuroimaging studies of priming. Progress in Neurobiology, 70(1), 53–81. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y., & Wang, L. (2017). The cross-modal effect of the haptic set on visual size perception. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1561. [CrossRef]

- Jaba, T. (2022). Dasatinib and quercetin: short-term simultaneous administration yields senolytic effect in humans. Issues and Developments in Medicine and Medical Research Vol. 2, 22-31.

- Jolles, D. D., & Crone, E. A. (2012). Training the developing brain: a neurocognitive perspective. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 6, 76. [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Katz, B., Shah, P., & Meyer, D. E. (2018). How to play 20 questions with nature and lose: Reflections on 100 years of brain-training research. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(40), 9897-9904. [CrossRef]

- Kok, P., Mostert, P., & de Lange, F. P. (2017). Prior expectations induce prestimulus sensory templates. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(39), 10473-10478. [CrossRef]

- Réber, A. S. (2013). Implicit learning and tacit knowledge: An essay on the cognitive unconscious. In The Oxford Handbook of Cognitive Psychology. Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]

- Schütz-Bosbach, S., & Prinz, W. (2007). Perceptual resonance: action-induced modulation of perception. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11(8), 349–355. [CrossRef]

- Seger, C. A. (2018). Corticostriatal foundations of habits. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 20, 153–160. [CrossRef]

- Song, J. H., & Nakayama, K. (2008). Target selection in visual search as revealed by movement trajectory. Vision Research, 48(7), 853–861. [CrossRef]

- Sterzer, P., Adams, R. A., Fletcher, P., Frith, C., Lawrie, S. M., Muckli, L., ... & Corlett, P. R. (2018). The predictive coding account of psychosis. Biological Psychiatry, 84(9), 634–643. [CrossRef]

- Tognoli, E., & Kelso, J. A. (2014). The metastable brain. Neuron, 81(1), 35-48. [CrossRef]

- Tsvetkov, A., Kuptsova, S., & Ivanova, M. (2022). Cognitive rigidity in healthy aging and frontotemporal degeneration. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 14, 841647. [CrossRef]

- Tkemaladze, J. (2023). Reduction, proliferation, and differentiation defects of stem cells over time: a consequence of selective accumulation of old centrioles in the stem cells?. Molecular Biology Reports, 50(3), 2751-2761. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36583780/.

- Tkemaladze, J. (2024). Editorial: Molecular mechanism of ageing and therapeutic advances through targeting glycative and oxidative stress. Front Pharmacol. 2024 Mar 6;14:1324446. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tkemaladze, J. (2025). Through In Vitro Gametogenesis—Young Stem Cells. Longevity Horizon, 1(3). [CrossRef]

- Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases. Science, 185(4157), 1124–1131. [CrossRef]

- Uznadze, D. N. (1966). The Psychology of Set. Consultants Bureau.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).