Over the past decade, energy drink consumption among adolescents has increased significantly, becoming a major public health concern. These beverages are marketed as performance enhancers that boost alertness and stamina. However, they often contain high amounts of caffeine, sugar, taurine, and other stimulant ingredients that pose serious health risks for developing bodies [

8]. Alarmingly, consumption is also rising among younger children and early adolescents, which further escalates these concerns [

7]. Despite the known risks, energy drinks remain popular due to aggressive marketing, peer pressure, and the lack of age-specific regulatory guidelines [

3].

Adolescents often lack adequate knowledge regarding the adverse effects of energy drinks. These beverages are frequently used during high-stress academic periods or social gatherings, sometimes in combination with alcohol or other substances, further exacerbating their negative impact [

11]. A national study in Canada revealed that 74% of adolescents had consumed energy drinks at least once, with 36% experiencing adverse symptoms such as rapid heartbeat and nausea [

2]. Similar usage patterns have been reported in the United States, Europe, and South Korea, where teenagers use energy drinks to manage academic stress or enhance athletic performance, often experiencing side effects such as sleep disturbances, mood swings, and increased heart rate [

9,

13]. Notably, most remain unaware of safe caffeine limits.

In Pakistan, research highlights similar patterns. A study reported that nearly half of medical students regularly consumed energy drinks but lacked knowledge about their harmful effects [

14]. This reflects a broader issue of insufficient health literacy among young people in the region. These trends are concerning as they underscore the widespread misconception that energy drinks are harmless stimulants, a belief shaped more by marketing than by science [

5].

Social media and digital marketing significantly influence youth consumption behavior. Platforms like YouTube, TikTok, and Instagram feature promotional content that rarely includes health warnings, thus normalizing energy drink use among teens [

1]. Digital marketing had a stronger impact on youth behavior than traditional media [

1,

4]. These campaigns often bypass age-specific advertising regulations, targeting vulnerable demographics with persuasive messaging [

6,

10].

Physiologically, energy drinks can lead to increased blood pressure, insomnia, and, in extreme cases, cardiac arrhythmias [

11]. Psychologically, frequent use is associated with heightened anxiety, aggression, poor academic performance, and risky behaviors such as substance abuse and school absenteeism [

13,

15]. Consumption patterns also vary by region, gender, and socioeconomic status, as highlighted in pan-European data [

16].

Despite these risks, energy drinks remain easily accessible, and awareness about their health implications is limited. The labeling of energy drinks is another concern, as most do not provide clear caffeine content or health risk disclosures [

10]. In low- and middle-income countries like Pakistan, adolescents face increasing exposure to these products with minimal access to health education that highlights their dangers. To mitigate these risks, educational interventions such as school-based awareness campaigns and digital media literacy programs have been shown to reduce energy drink consumption [

3,

12]. However, policy measures alone are insufficient unless aligned with adolescents’ digital consumption habits.

Therefore, this study aims to assess adolescents’ knowledge of energy drink-related health risks. Participants were recruited from various public settings and completed a knowledge-focused Likert-scale survey. The findings will inform future awareness programs and policy recommendations targeting adolescent health education.

Materials and Method

Population

The target population includes adolescents aged 15 to 18 years from Karachi, Pakistan.

Sample

A total of 50 adolescents were selected for this study.

Sampling Technique

A purposive sampling approach was employed to select participants aged 15 to 18 years from both genders, with the aim of ensuring representation across these demographic groups. Participants were approached in various public settings, including shopping malls, restaurants, cafeterias, and public parks. Adolescents who met the age criteria and voluntarily agreed to participate were given the questionnaire to fill out on the spot.

Before the main survey, a brief pilot test (n=5) was conducted to evaluate the clarity and reliability of the questionnaire. Adjustments were made to two questions based on feedback. Cronbach’s alpha was calculated at .81, indicating acceptable internal consistency.

Recruitment and Incentive

Participants were rewarded with a booklet featuring four creative, adolescent-friendly pages detailing the health risks of energy drinks, designed using visual storytelling techniques.

Data Analysis Technique

After the data collection phase, the responses from the 12-item Likert-scale questionnaire were compiled and scored to compute a total awareness score for each participant, ranging from 12 to 60. Basic descriptive statistics including mean, median, standard deviation, minimum, and maximum were calculated to summarize the overall knowledge level of the adolescent sample. Participants were then categorized into three awareness levels (low, moderate, high) based on their total scores using predetermined cutoff points.

To examine whether awareness levels varied significantly across demographic groups, inferential statistical tests were conducted. Independent samples t-tests were used to compare the mean awareness scores between male and female participants, as well as between younger (15–16 years) and older (17–18 years) adolescents. Additionally, Chi-square tests of independence were performed to analyze associations between categorical awareness levels (low, moderate, high) and demographic variables (gender and age group).

All statistical analyses were conducted using Microsoft Excel and IBM SPSS Statistics (version 25). A significance level of p < .05 was used to determine statistical significance.

Confidentiality and Ethical Considerations

All participation in the study was entirely voluntary. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to any data collection. Rigorous measures were implemented to ensure the confidentiality of participant data.

Results

Table 1.

Overview of Participant Demographics and Awareness Scores.

Table 1.

Overview of Participant Demographics and Awareness Scores.

| Variable |

Value |

| Sample size |

50 |

| Age range |

15-18 |

| Gender |

Male (25), Female (25) |

| Mean score |

25 |

| Median |

24 |

| Standard deviation |

4.777 |

| Minimum score |

20 |

| Maximum score |

41 |

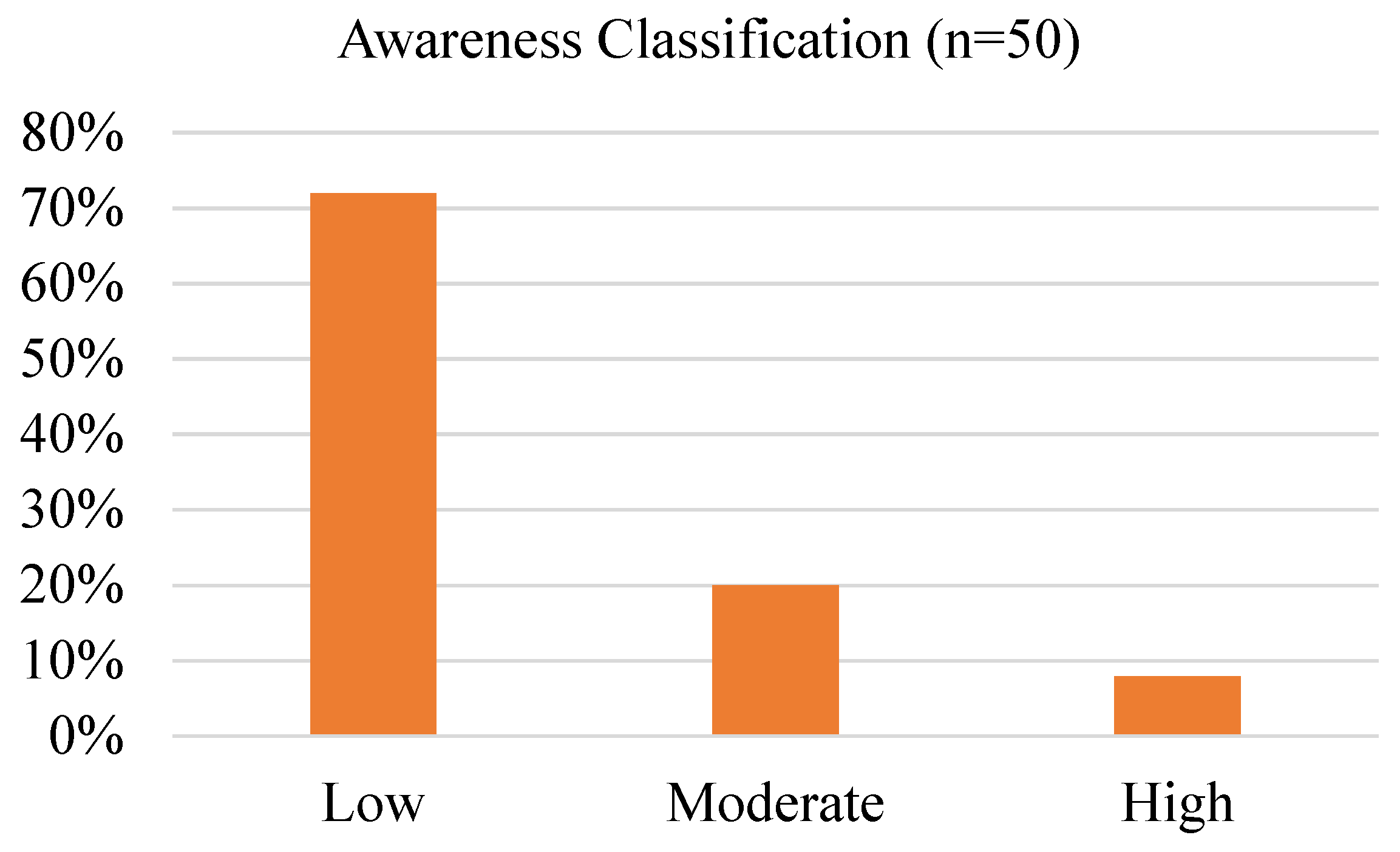

Figure 1 illustrates a large majority (72%) of adolescents fall into the low awareness category, indicating that most participants lack sufficient knowledge about the health risks of energy drink consumption.

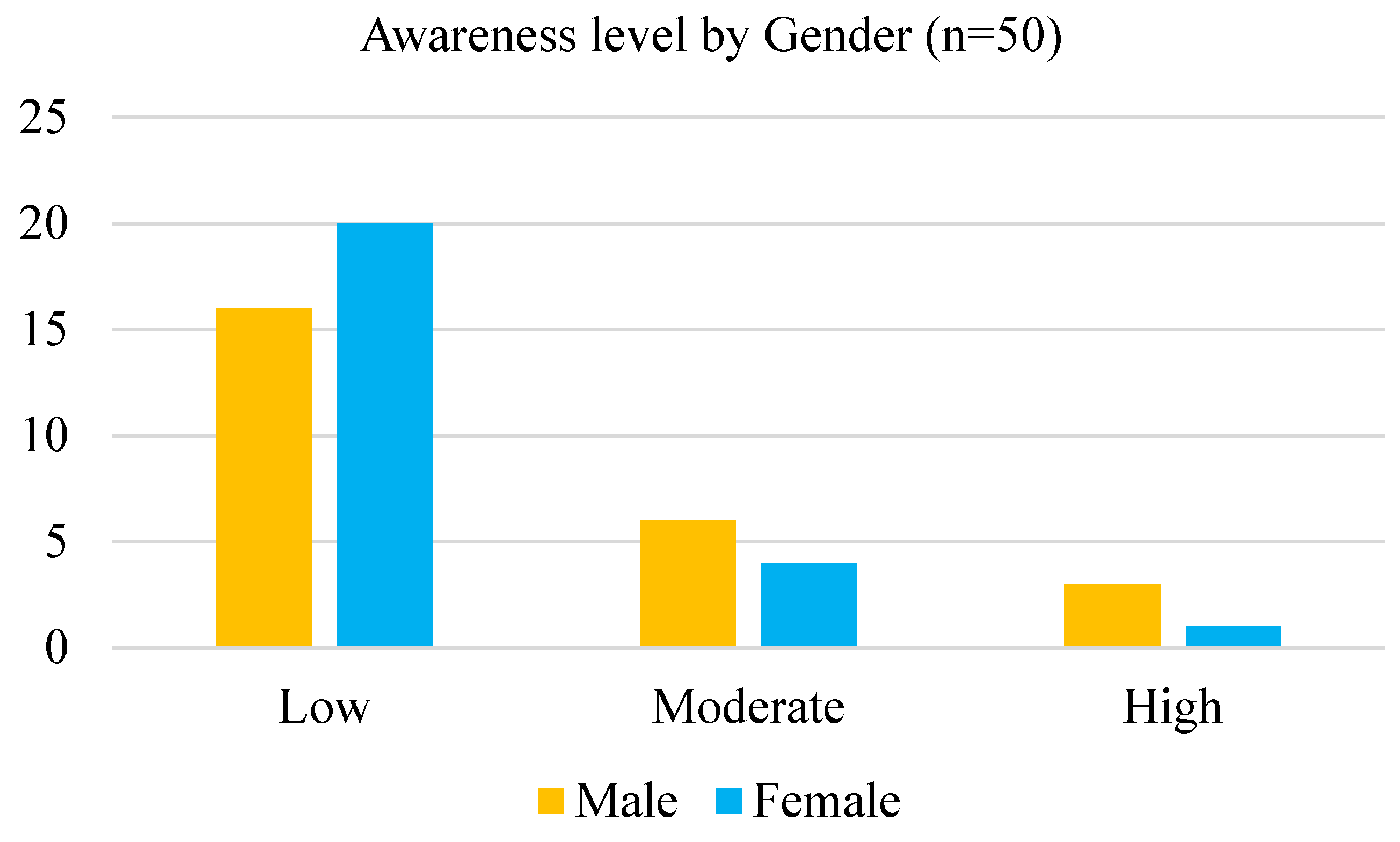

Independent samples t-tests and chi-square analyses revealed no statistically significant differences in awareness scores or levels based on gender (

p = .33 and

p = .51, respectively) or age group (

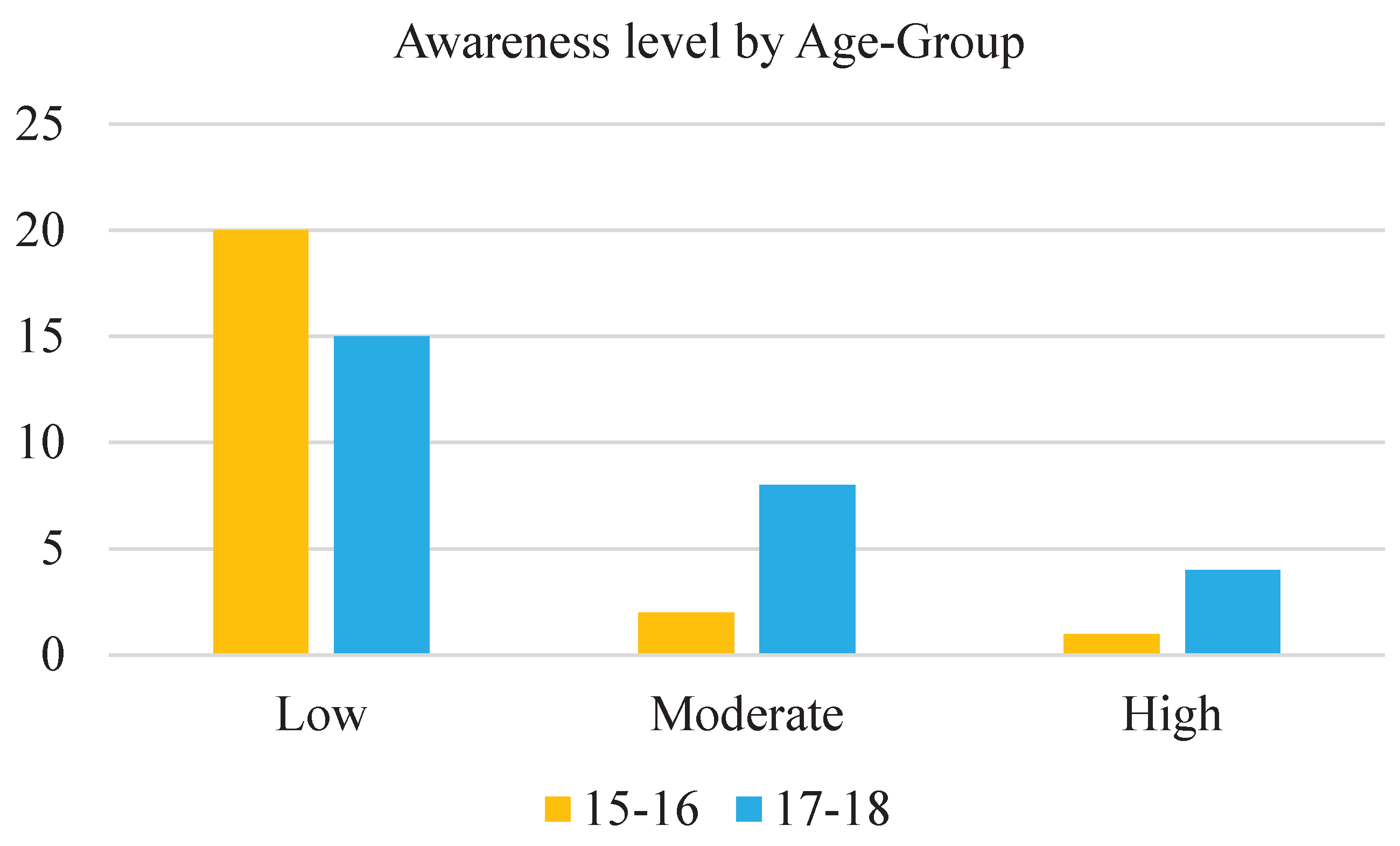

p = .25 and

p = .18, respectively). These results suggest that the knowledge deficit is widespread and not limited to a particular demographic segment among adolescents (

Table 2).

The gender-based analysis of awareness levels indicates that both male and female participants predominantly fall within the low awareness category. However, males showed a slightly higher representation in the moderate and high awareness levels compared to females (

Figure 2). This marginal difference suggests that while overall awareness remains low across both genders, male adolescents might be slightly more receptive to or informed about the health consequences of energy drink consumption. These findings highlight the need for targeted awareness campaigns that address gender-specific communication strategies to improve health literacy among adolescents.

The analysis of awareness levels across age groups reveals a notable trend. Among participants aged 15–16, the majority demonstrated low awareness of the adverse health effects of energy drink consumption, with only a small proportion falling into the moderate category and none reaching the high awareness level. In contrast, the 17–18 age group exhibited a more balanced distribution, with several participants achieving moderate and high awareness levels (

Figure 3). This suggests that older adolescents may have greater exposure to health-related information or more cognitive maturity to understand such risks, indicating the importance of age-tailored educational interventions.

Discussion

The findings of this study reveal a significant gap in adolescents’ knowledge regarding the adverse health effects of energy drink consumption. With an average awareness score of 25 out of 60 and a median of 24, most participants demonstrated limited understanding of energy drink ingredients, health risks, and recommended usage. Notably, 72% of the sample fell into the “low awareness” category, and only a small minority exhibited high levels of knowledge. These results align with previous research indicating that despite the widespread consumption of energy drinks, adolescents often lack critical health literacy in this area [

5].

Importantly, statistical analysis showed no significant differences in awareness scores across gender (

p = .33,

p = .51) or age groups (

p = .25,

p = .18). This suggests that low awareness is a pervasive issue across demographic subgroups, rather than being concentrated in specific segments of the adolescent population. These findings are consistent with those reported in [

8], which found that peer influence, unregulated digital advertising, and inadequate health education contribute to a uniformly low level of knowledge among youth. Additionally, the absence of stronger awareness in older adolescents challenges the assumption that knowledge increases with age and highlights the systemic nature of the issue.

One explanation may lie in the lack of formal education about energy drinks in school curricula. Furthermore, adolescents are routinely exposed to misleading advertising through social media, sports endorsements, and pop culture. As noted in [

15], such campaigns often present energy drinks as performance-enhancing and socially desirable, rarely offering nutritional warnings. This was evident in this study’s reverse-scored items, where many participants struggled to correctly interpret reverse-scored items, highlighting susceptibility to misleading health claims.

This study’s findings also underscore the limitations of passive digital exposure. Although social media was used effectively for recruitment, it did not correlate with higher awareness. This implies that awareness-building requires more structured and engaging educational approaches, such as interactive videos, gamified apps, or visual booklets tailored to adolescent media habits.

Limitations

The sample size (n = 50) was relatively small, limiting the generalizability of findings. The use of self-reported data may also introduce bias due to inaccurate recall or social desirability. Additionally, the cross-sectional design prevents causal inferences regarding the impact of digital exposure or age on awareness.

Future Implications

This study highlights the urgent need to incorporate energy drink education into school-based health curricula. Educational efforts should begin early and be tailored to adolescents’ preferred communication channels. Health campaigns must move beyond awareness and actively engage students through interactive, evidence-based materials. In parallel, policy measures must address misleading marketing practices by enforcing age-specific regulations and digital media accountability.

Conclusions

This study revealed a significant lack of awareness among adolescents regarding the adverse health effects of energy drink consumption, with the majority of participants falling into the low-awareness category. The absence of significant differences across gender and age groups indicates that this knowledge gap is widespread and not limited to any particular demographic. These findings align with global concerns about rising energy drink use among youth without adequate health education or risk understanding.

Despite limitations such as a small sample size and purposive sampling, the consistency of low scores across the dataset underscores the urgency of the issue. The study emphasizes the need for targeted educational interventions, particularly through platforms familiar to adolescents, such as schools and social media. To protect adolescent health, future research should examine the impact of such interventions and involve larger, more diverse populations to strengthen generalizability and guide policy development.

Recommendations

Integrate digital health literacy into social media platforms.

Introduce formal lessons on energy drinks in school health curricula.

Encourage parental engagement in adolescent health education.

Appendix A

Section A: Demographic Information

Age: ___________________ years

-

Gender

☐ Male

-

Female Do you currently consume energy drinks?

☐ Never

☐ Occasionally

☐ Weekly

-

Daily Which of the following energy drink brands have you tried? (Tick all that apply)

☐ Red bull

☐ Booster

☐ Sting

-

OtherWhere did you first learn about energy drinks?

☐ Friends & family

☐ Social media

☐ School

Section B: Knowledge Assessment of Energy Drinks

Use the scale below and tick (✓) for each statement.

1 = Strongly Disagree 2 = Disagree 3 = Neutral 4 = Agree 5 = Strongly Agree

| Statement |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

| I am aware that energy drinks contain high levels of caffeine. |

|

|

|

|

|

| Energy drinks can cause sleep problems in teenagers. |

|

|

|

|

|

| Consuming energy drinks can lead to heart issues like palpitations or high blood pressure. |

|

|

|

|

|

| Energy drinks can be addictive. |

|

|

|

|

|

| I know that energy drinks are not the same as sports drinks like ORS. |

|

|

|

|

|

| It is safe to consume energy drinks before or during exercise. (Reverse-scored) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Energy drinks help improve focus and school performance. (Reverse-scored) |

|

|

|

|

|

| I am aware that energy drinks may negatively affect mental health. |

|

|

|

|

|

| Mixing energy drinks with other substances (e.g., alcohol or medicine) can be dangerous. |

|

|

|

|

|

| I can name at least 3 side effects of energy drink overuse. |

|

|

|

|

|

| I have received formal or informal education about energy drinks from school, parents, or online. |

|

|

|

|

|

| Energy drinks are just flavored soft drinks with no harm. (Reverse-scored) |

|

|

|

|

|

Thank you for your participation!

References

- Alissa, N. A. (2024). The impact of social media on adolescent energy drink consumption. Medicine, 103(19), e38041. [CrossRef]

- Azagba, S., Langille, D., & Asbridge, M. (2014). An emerging adolescent health risk: Caffeinated energy drink consumption patterns among high school students. Preventive Medicine, 62, 54–59. [CrossRef]

- Breda, J. J., Whiting, S. H., Encarnação, R., Norberg, S., Jones, R., Reinap, M., & Jewell, J. (2014). Energy drink consumption in Europe: A review of the risks, adverse health effects, and policy options to respond. Frontiers in Public Health, 2, Article 134. [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, L., Yeatman, H., Kelly, B., & Kariippanon, K. (2018). Digital promotion of energy drinks to young adults is more strongly linked to consumption than other media. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 50(9), 888–895. [CrossRef]

- Costa, B. M., Hayley, A., & Miller, P. (2014). Young adolescents’ perceptions, patterns, and contexts of energy drink use: A focus-group study. Appetite, 80, 183–189. [CrossRef]

- Emond, J. A., Sargent, J. D., & Gilbert-Diamond, D. (2015). Patterns of energy drink advertising over US television networks. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 47(2), 120–126. [CrossRef]

- Gallimberti, L., Buja, A., Chindamo, S., Vinelli, A., Lazzarin, G., Terraneo, A., Scafato, E., & Baldo, V. (2013). Energy drink consumption in children and early adolescents. European Journal of Pediatrics, 172(10), 1335–1340. [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Hellín, J., & Varillas-Delgado, D. (2021). Energy drinks and sports performance, cardiovascular risk, and genetic associations: Future prospects. Nutrients, 13(3), 715. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. Y., Sim, S., & Choi, H. G. (2017). High stress, lack of sleep, low school performance, and suicide attempts are associated with high energy drink intake in adolescents. PLOS One, 12(11), e0187759. [CrossRef]

- Pomeranz, J. L., Munsell, C. R., & Harris, J. L. (2013). Energy drinks: An emerging public health hazard for youth. Journal of Public Health Policy, 34(2), 254–271. [CrossRef]

- Seifert, S. M., Schaechter, J. L., Hershorin, E. R., & Lipshultz, S. E. (2011). Health effects of energy drinks on children, adolescents, and young adults. Pediatrics, 127(3), 511–528. [CrossRef]

- Temple, J. L., Bernard, C., Lipshultz, S. E., Czachor, J. D., Westphal, J. A., & Mestre, M. A. (2017). The safety of ingested caffeine: A comprehensive review. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 8, 80. [CrossRef]

- Trapp, G. S. A., Allen, K., O’Sullivan, T., Robinson, M., Jacoby, P., & Oddy, W. (2014). Energy drink consumption is associated with anxiety in Australian young adult males. Depression and Anxiety, 31 (5), 420–428. [CrossRef]

- Usman, A., Bhombal, S. T., Jawaid, A., & Zaki, S. (2015). Energy drink consumption practices among medical students of a private-sector university in Karachi, Pakistan. Journal of Pakistan Medical Association, 65(9), 1005–1007. https://ecommons.aku.edu/pakistan_fhs_mc_fam_med/209/.

- Visram, S., Cheetham, M., Riby, D. M., Crossley, S. J., & Lake, A. A. (2016). Consumption of energy drinks by children and young people: A rapid review examining evidence of physical effects and consumer attitudes. BMJ Open, 6(10), Article e010380. [CrossRef]

- Zucconi, S., Volpato, C., Adinolfi, F., Gandini, E., Gentile, E., Loi, A., & Fioriti, L. (2013). Gathering consumption data on specific consumer groups of energy drinks (EFSA Supporting Publications, 10(3), EN-394). European Food Safety Authority. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).