1. Introduction

Quantum machine learning (QML) has emerged as a promising interdisciplinary field at the confluence of quantum computing, machine learning, and quantum information [

1,

2]. Fueled by the potential for computational speedups and the ability to process data in quantum mechanical ways [

3,

4], QML explores how to leverage quantum computers to enhance classical data analysis. Early works in the field laid the groundwork for a new theoretical framework for learning [

5], while more recent contributions have focused on the practical implementation of algorithms and their potential for achieving a quantum advantage [

6].

QML has been applied to various domains, from methods based on quantum kernels for improving predictive accuracy [

7] to applications in data analysis such as breast cancer detection and image classification [

8]. While the field holds immense promise, it is not without challenges, most notably the issue of barren plateaus, which can hinder the training of deep quantum neural networks [

9].

Recent reviews highlight the growing potential of QML in biological and biomedical domains [

10]. Applications in the biological sciences span diverse areas, including bioinformatics, drug discovery, and medical diagnostics [

11]. For instance, QML has been explored for drug discovery through qualitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) predictions, demonstrating that quantum classifiers can outperform classical ones, particularly when working with limited data and a reduced number of features [

12]. In bioinformatics, quantum annealers have been trained on transcription data, showing a slight advantage in classification and near-equal ranking performance compared to classical methods on simplified datasets [

13]. Similarly, annealing algorithms of the Ising type, inspired by quantum processors, have shown superior classification performance on small training sets of omics cancer data, a finding particularly relevant for rare diseases or limited clinical data [

14].

Further studies have showcased the utility of QML in medical diagnostics. A quantum machine learning framework, QProteoML, has been proposed to predict drug sensitivity in multiple myeloma using high-dimensional proteomic data, outperforming classical machine learning algorithms [

15]. For breast cancer prediction, QML has been identified as a cost-effective and efficient strategy, with specific algorithms like Pegasos-QSVC excelling in recall metrics and quantum neural networks (QNNs) achieving high accuracy for binary classification of genomic sequence data [

16,

17]. Research also explores the use of quantum-inspired machine learning for metastasis prediction in breast cancer, employing least-squares methods via quantum measurements [

18]. The mapping of quantum algorithms to applications in electronic health records (EHR), omics, and imaging has also been detailed, alongside the challenges of discovery, validation, and adaptation of quantum computing in these fields [

19]. This body of work underscores the interdisciplinary nature of QML and its potential to address complex challenges in molecular biology and medicine.

A key area of research within QML is the development of quantum algorithms for tasks like classification and regression. The variational quantum eigensolver (VQE) [

20] is a prime example of a hybrid quantum-classical algorithm that has been adapted from its traditional use in molecular ground state estimation to tackle optimization problems [

21]. As VQE gained attraction, a variety of research has focused on improving its performance and extending its capabilities, particularly for noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices. Recent advances include methods to handle constraints and ensure the algorithm finds a true eigenstate [

22], as well as new approaches for exploring the Hilbert space to find non-orthogonal solutions [

23]. To address limitations in circuit complexity, researchers have proposed techniques such as clustering qubits to create shallower circuits [

24] and schemes based on measurement that use entangled resource states [

25]. Other optimizations include qubit-efficient strategies that can represent complex states with fewer physical qubits by using sequential measurements [

26] and accelerated VQE algorithms that interpolate between VQE and quantum phase estimation (QPE) [

27]. Furthermore, VQE has been shown to be effective for complex problems, with successful implementations on Hamiltonians with hundreds of Pauli terms [

28]. These methodological advances, along with comprehensive reviews of VQE’s components and extensions [

29], have cemented its position as a central tool in near-term quantum computing.

Beyond its traditional application in finding the ground state of molecular Hamiltonians, VQE and its counterpart, the variational quantum classifier (VQC), have found an expanding role in the biological and biomedical sciences, particularly in addressing complex optimization and classification problems. VQE, for instance, has been leveraged for enhancing molecular predictions in drug discovery, demonstrating that its application in molecular dynamics simulations can lead to improved accuracy compared to classical methods [

30]. This is complemented by its use in identifying candidate inhibitors through a synergy with quantum graph neural networks, which can model molecular structures [

31]. In a similar vein, researchers have applied VQE to find the ground state of molecular systems of genes, a critical step in understanding genetic interactions [

32].

VQE and VQC have also been explored for a variety of clinical and medical informatics tasks. For instance, they show promise in optimizing clinical trial site selection by finding the ground state of a Hamiltonian that represents the optimization problem, potentially improving high-dimensional classical parameter spaces [

33]. In medical diagnostics, VQC has been successfully applied to problems such as classifying diabetes using an 8- and 4-qubit circuit with rotation and controlled-NOT (

) entanglement layers [

34] and predicting asthma with high accuracy by using the quantum approximate optimization algorithm (QAOA) for feature selection [

35]. Furthermore, a hybrid autoencoder and VQC framework has been proposed for the classification of anomalies in biological samples, showcasing its potential in identifying irregularities [

36]. These applications highlight VQE’s and VQC’s ability to bridge quantum and molecular systems, a capability that makes them particularly promising for medical applications where complex, high-dimensional data is prevalent [

37]. Such advancements show the potential of these variational methods to transform biomedical data analysis by moving beyond traditional computational paradigms to harness quantum-mechanical principles for more efficient and accurate results.

A notable gap persists in the literature regarding the application of quantum computing to immunology and epidemiology, especially in the context of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and syndemic co-infections. Immunology itself generates data of extraordinary complexity—ranging from protein interaction networks to single-cell sequencing—that often exceed the representational and computational capacity of classical approaches. To address this, Basu et al. [

38] have proposed a quantum framework for cell-centric therapeutics, which employs quantum algorithms to infer missing links in protein interaction networks by mapping them into exponentially large Hilbert spaces. This approach offers a novel foundation for precision medicine and provides a computational pathway to model the intricate interplay of viral and host proteins, immune cells, and co-morbidities in HIV pathogenesis.

Complementing this progress, quantum-mechanical perspectives on immune signaling have begun to emerge. One such model proposes that T-cell activation operates through quantized energy transfers during protein phosphorylation, mediated by receptor phosphorylation–dephosphorylation cycles initiated by pulses in the peptide complexes [

39]. This framework suggests that fundamental immunological processes may unfold in discrete quantum units, thereby enabling more accurate modeling of disease progression in conditions such as HIV, where immune dysfunction is central. Similarly, the concept of "quantum microRNA (miRNA) immunity" has been advanced as a lens to interpret viral manipulation of host gene regulation [

40]. By treating aberrant miRNA regulation as a process driven by entanglement, this model connects quantum principles to the nonlinear, multivariate dynamics of viral immunodeficiency, opening avenues for QML applications to viral genomics and cancer biology.

At the epidemiological scale, the first empirical steps toward quantum applications in population health have been demonstrated by Dan Roosan and his research group in their study of QAOA for HIV clusters forecasting, [

41]. This research introduced a quantum-accelerated approach to HIV surveillance, reframing cluster detection as a quadratic unconstrained binary optimization (QUBO) problem. Using the QAOA, the method achieved

clustering accuracy in 1.6 seconds, outperforming classical density-based approaches. In parallel, a hybrid neural network reached

forecasting accuracy for HIV prevalence, surpassing a purely classical counterpart. Notably, quantum Bayesian networks revealed the causal roles of housing instability and stigma in driving cluster emergence and expansion, highlighting structural determinants of disease. This study demonstrates the potential of quantum computing to move beyond applications at a molecular scale towards modeling at the population level, thereby informing prevention strategies, resource allocation for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), and interventions addressing structural inequities.

Building on this emerging landscape, Choppara and Lokesh [

42] worked with predictions of genetic mutations in viral proteins, with a specific focus on the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) as a model system. Leveraging quantum features for dimensionality reduction and embedding them within a quantum long short-term memory (QLSTM) architecture, they demonstrate the model’s ability to capture complex, nonlinear relationships in genomic data. QLSTM outperforms classical deep learning models in mutation prediction accuracy, while also providing biologically meaningful insights into immune evasion and viral transmissibility.

Researchers at Merrimack College, led by Roosan, have made significant contributions to the field, with a particular focus on applying quantum computing and QML to complex problems in biology and clinical medicine. Their work spans diverse quantum algorithms and architectures at the molecular scale, demonstrating how quantum methods for complex biomolecular interactions can predict protein-ligand binding affinity by mapping molecular interactions to a high-dimensional Hilbert space, capturing complex relationships with fewer parameters on par with or even improving upon classical models [

43]. This is complemented by quantum simulation for protein structural analysis, which investigated the structural stability of proteins implicated in neurodegenerative disorders and identified regions for protein-protein interactions [

44]. Additionally, a quantum regression model was developed to predict the toxicity of herbal compounds, integrating both molecular and pharmacokinetic data to achieve lower prediction errors than classical linear regression and random forest models [

45]. Their research also highlights how a hybrid QNN can outperform a classical liquid neural network (LNN) in drug repurposing by leveraging amplitude encoding and feature maps to analyze drug databases [

46].

Expanding on these advances, Roosan’s group further demonstrated the power a quantum variational transformer model for enhanced cancer classification, using a hybrid approach to capture intricate genomic patterns more effectively than classical transformer models, resulting in reduced misclassification for complex cancer types [

47]. They also developed a prototype for drug repurposing using omics data, integrating quantum principal component analysis (QPCA) and quantum kernel methods to achieve tighter clustering and better performance compared to classical approaches, particularly when combined with large language models (LLMs) [

48]. Collectively these studies establish a foundational context for the present work, showcasing the ability of QML methods to address complex challenges in biological and clinical research.

In this work, we extend a previously proposed approach using VQE for clinical biomarker discovery [

49]. Our method inverts the traditional VQE paradigm: instead of minimizing the energy of a fixed Hamiltonian, we fix the quantum state (representing a patient’s clinical profile) and search for a Hamiltonian whose ground state energy closely matches the state’s expectation value. This "inverse VQE" offers a novel lens to identify complex biomarkers with multiple relationships that are highly predictive of a patient’s condition.

Our prior work demonstrated the feasibility of this approach using a single-qubit model, successfully identifying key biomarkers related to HIV treatment response and co-morbidities. However, a single qubit’s limited degrees of freedom restricts its ability to capture the multifaceted nature of clinical data. Here, we generalize the model to a multi-qubit system, allowing for the simultaneous encoding of multivariate patient features and, critically, the inclusion of multiple qubits interaction terms in the Hamiltonian. The resulting increase in expressivity and complexity enables a deeper exploration of the relationships between biomarkers, including those that are non-classical in nature.

The specific clinical data used comes from a cohort of patients with HIV and tuberculosis (TB) co-infection. We analyze key clinical markers such as viral load and CD4 count differences, alongside quantum game theoretic features. We hypothesize that a multi-qubit model, by accommodating interaction terms like and , will reveal more intricate biomarker relationships and provide a more robust and clinically relevant set of Hamiltonians.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Acquisition and Feature Engineering

This study leverages the

qphen dataset, a unique resource for applying quantum inspired algorithms to clinical data related to HIV. The dataset is publicly available through the

qvirus package [

50] on the Comprehensive R Archive Network (CRAN) [

51]. Data were collected from a longitudinal cohort of 213 individuals with HIV and TB co-infection at a clinic in Guerrero, Mexico, from 2018 to 2024, in accordance with institutional and national research ethics guidelines. The protocol was approved by the Local Health Research Committee 1102 of General Regional Hospital No. 1.

The dataset integrates classical clinical measurements with engineered features derived from a quantum game theoretic model of HIV phenotypes [

52]. Key variables include differences in viral load (

) and CD4 T lymphocyte counts (

), along with binary indicators for TB co-infection (

) and genotypic drug resistance (

).

A stringent data cleaning process was necessary to prepare the initial cohort comprised of 213 patient records for the quantum game theoretic model. This cleaning process excluded records with only a single longitudinal value, as these data points did not permit the derivation of change rates or the temporal dynamics that represent the competition between lymphocytes and viral load over time, features which proved critical for the model. Following this depuration, the base utilized for all subsequent analyses was reduced to 176 records, which were used for the feature engineering and modeling procedures.

A central component of the feature engineering process is the Nearest Payoff Algorithm, which bridges the observed viral dynamics in a study cohort with the vast state space of quantum game simulations. The quantum game is defined by a Hilbert space , an initial state , a set of strategies and corresponding payoffs . Two infectious phenotypes are considered: a low-replication phenotype v and a high-replication phenotype V, encoded as qubits and , respectively.

The game’s dynamics are governed by unitary operators. For a two-phenotype system, the initial state is prepared as:

where

I is the Identity and

is the Pauli

gate. Subsequent quantum moves, including Pauli gates and the Hadamard gate

H, are applied to generate superposition states that reflect different phenotype interactions. After applying the appropriate combination of quantum gates to evolve the initial state

U to the final state

, the expected payoffs

and

are computed as a weighted sum of the probability amplitudes of the final state (the quantum outcomes) and the classical payoff parameters:

and

Classical payoff parameters correspond to the outcomes of the four possible interactions , capturing biologically relevant properties such as resource consumption, replication rate, and survival.

The nearest payoff algorithm maps an observed patient viral load difference, , to the closest previously simulated quantum expected payoff, from a set of all possible payoffs. This process yields both a numeric prediction, and a phenotypic characterization, for each patient, based on the quantum strategy combination that generated the closest payoff. By embedding these quantum game theoretic outcomes into clinically interpretable features, the approach enhances the dataset with descriptors that capture nontrivial interactions between viral phenotypes, providing a richer basis for downstream analyses such as multi-qubit Hamiltonian modeling.

The key engineered features in the dataset include:

Quantum Payoffs: The variable nearest_payoff provides the numerical prediction for a patient’s phenotype. It’s the value of the closest simulated quantum payoff, or expected outcome, that best fits the patient’s viral load difference.

-

Quantum Strategy Encoding: This category is crucial for understanding the quantum model’s interpretation of a patient’s viral dynamics. The variables here encode the specific quantum gates used as strategies by two distinct HIV phenotypes, a low-replication phenotype (v) and a high-replication phenotype (V).

- –

phen_1 indicates whether the phenotype associated with the nearest payoff is v or V.

- –

str1_2: represents the primary strategy of the first phenotype, with a binary encoding that corresponds to the Pauli gate (X), the gate (T), or the H gate.

- –

str1_3: is the alternative strategy for the first phenotype, also using binary encoding.

- –

str2_2: is the primary strategy of the second phenotype. Its binary encoding corresponds to one of several quantum gates: H, I, Phase gate (S), T, X, Pauli gate (Y), or Pauli gate (Z).

- –

str2_3 to str2_7: are alternative strategies for the second phenotype. Each variable is a binary indicator (0 or 1) for the presence or absence of a specific quantum gate from the set .

Batch Indicator: The distinguishes predictions performed on the full dataset (0) versus batch-processed subsets (1).

Other features in the dataset are:

Phenotypic Clustering: Variables through are derived from a k-means clustering of standardized viral load and CD4 differences, which groups patients by their phenotypic behavior.

Clinical Differences: Variables such as and are the raw differences in viral load and CD4 T lymphocyte counts. Standardized versions ( and ) are also included.

Binary Clinical Indicators: and are binary variables that indicate the presence of TB co-infection and genotypic drug resistance, respectively.

For example, the payoff label translates to: (high-replication phenotype), (first strategy is the Pauli gate), (second strategy is the Hadamard gate), and (indicating a batch-processed subset).

This synthesis of classical clinical data with features derived with quantum games of phenotypes provides a robust foundation for biomarker discovery and patient stratification using the multi-qubit variational approach.

2.2. Multi-Qubit VQE Algorithmic Methods

This section presents the theoretical and algorithmic principles underlying the extension of the VQE to multi-qubit systems. As a hybrid quantum-classical algorithm, VQE enables practical simulations on near-term quantum hardware by preparing shallow quantum circuits while delegating computationally intensive optimization tasks to a classical processor. At its core, VQE leverages quantum simulation and the Schrödinger equation to define a Hamiltonian operator , whose eigenvalues correspond to the system’s energy levels. The variational principle ensures that the expectation value of any trial state provides an upper bound to the ground state energy.

VQE iteratively minimizes the expectation value of a parameterized Hamiltonian using a quantum trial state, or ansatz,

, for an

n-qubit system:

VQE iteratively minimizes the expectation value of a parameterized Hamiltonian using a quantum trial state, or ansatz,

, for an

n-qubit system:

where each

is a tensor product of Pauli matrices (

), and

are real coefficients. The expectation value of the Hamiltonian is

with

obtained from projective measurements on the quantum device. By the variational principle, for any normalized trial state

,

where

is the true ground state energy. Minimizing

over trial states provides the best approximation of

.

In multi-qubit systems, Hamiltonians are decomposed into single-qubit operators (acting on one qubit) and interaction terms (acting on multiple qubits). For a two-qubit system, single-qubit terms include or , whereas interaction terms include or , which induce correlations between qubits. The identity operator I acts as a placeholder for qubits not directly involved in a term.

Expectation values are measured using either analytical or sampling-based approaches. The analytical method involves simulation where the quantum state

can be represented as a density matrix

, and the exact expectation value of a Pauli operator

P is:

|

Algorithm 1: Analytical Pauli Expectation Value Estimation

|

Require:

Quantum state , Pauli operator P

- 1:

Compute

- 2:

Represent P as a matrix - 3:

Calculate - 4:

return E

|

Alternatively, the sampling-based method is used on real quantum hardware, where expectation values are probabilistically estimated from repeated measurements

.

where

is the eigenvalue of

for the

k-th shot after appropriate basis rotations. Specifically, to measure multi-qubit Pauli terms, the state must first be transforming the state with a basis change unitary operator

to map the observable to the standard computational (

Z) basis:

|

Algorithm 2: Sampling-Based Pauli Expectation Value Estimation |

-

Require:

Quantum state , Pauli operator P, shots N

- 1:

Apply basis rotations for measurement in the basis - 2:

Compute probability distribution from state vector - 3:

Draw N samples to simulate measurement outcomes - 4:

Map samples to eigenvalues

- 5:

Average eigenvalues to estimate - 6:

return Estimated expectation value |

The analytical method provides exact benchmarks for algorithm validation, whereas the sampling-based method simulates realistic hardware execution, accounting for statistical fluctuations.

The core of our hybrid quantum-classical approach involves preparing a patient-specific quantum state that encodes the clinical status. This is achieved through two main components: amplitude encoding (the mapping of classical features to rotation angles) and the ansatz circuit (the parameterized quantum circuit structure).

2.2.1. Amplitude Encoding: Mapping Clinical Data to Angles

For our multi-qubit system, four key clinical features are assigned to the four rotation angles of the ansatz circuit. This technique, known as feature embedding, utilizes Min-Max Normalization to scale each clinical value x into the rotation range , ensuring that the entire feature space is represented by the quantum Hilbert space.

The four encoded features are: viral load mean difference (

), CD4 mean difference (

), TB co-infection (

), and genotypic drug resistance (

). Each feature

is normalized using the full range of the data set:

where

defines one of the four rotation angles. The resulting normalized features define the rotation parameters of the ansatz as

2.2.2. Ansatz Definition and Circuit Diagram

The ansatz is the multi-qubit parameterized quantum circuit used to create the patient state . Its structure is fixed across all patients, but its parameters (the rotation angles) are unique for each patient’s clinical data.

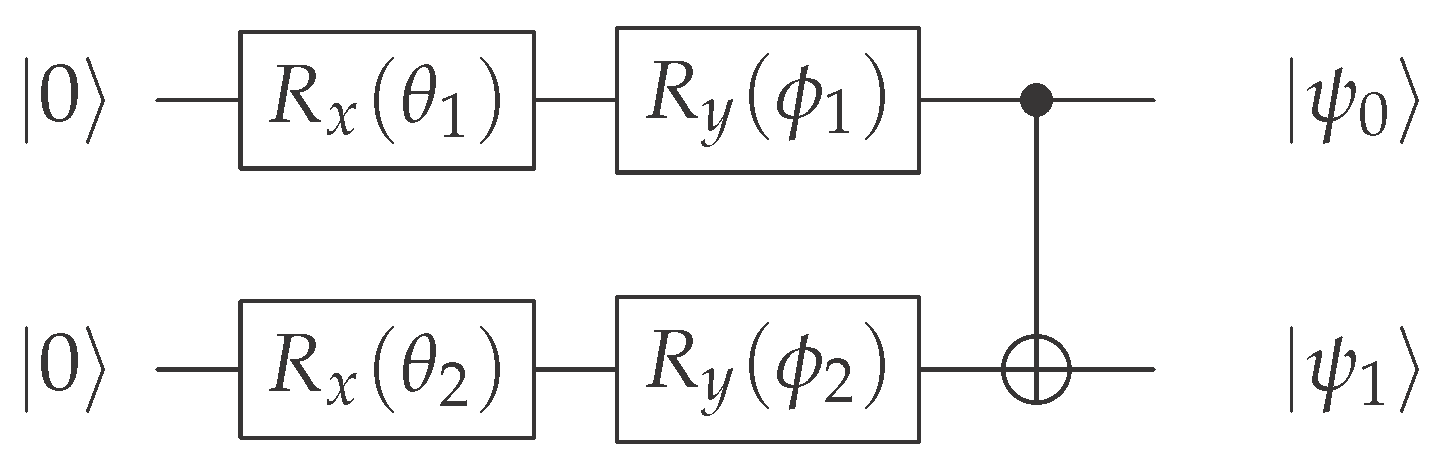

The circuit initializes both qubits in the ground state 0 and applies two sequential single-qubit rotations ( and ) on each qubit, followed by a CNOT gate for entanglement. The circuit diagram is as follows:

2.2.3. Resulting Amplitudes and Entangled State

Each sequence of single-qubit rotations transforms the basis state 0 into a superposition state whose amplitudes are functions of the input clinical features:

Before the entanglement step (CNOT), the state of the two-qubit system is a simple tensor product. The CNOT gate then acts to couple the features, mapping the state 10 to 11.

This results in the final, entangled patient state:

where

and

are the complex amplitudes of Eq.

12 for qubit

. This construction ensures that the final state reflects both the individual features and their latent correlations, which is critical for the Hamiltonian search phase.

2.2.4. Inverse/Data-Conditioned VQE

Rather than the standard VQE, where ansatz parameters are optimized for a fixed Hamiltonian, here the paradigm is inverted: the patient-specific quantum state is fixed, and the algorithm searches for a Hamiltonian whose ground state best matches this state. The objective function is the delta metric:

with

the minimal eigenvalue of the trial Hamiltonian. The optimization problem is

which identifies the Hamiltonian that most accurately represents the patient’s encoded state and highlights the most informative features.

This framework integrates the measurement of multi-qubit Pauli terms with a stochastic Hamiltonian optimization that highlights patient-specific feature correlations. The minimum delta is analogous to the ground state energy in conventional VQE, while the selected coefficients indicate the most informative clinical features.

The optimal Hamiltonian search described in Algorithm 3 is extended into a global binary classification routine to predict clinical status (e.g. TB co-infection or drug resistance) throughout a patient cohort. In this classification context, the Hamiltonian expectation value for a patient

x serves as the direct classification score

of Equation

16.

|

Algorithm 3: Optimal Clinical Hamiltonian Search for Multi-Qubit Systems |

-

Require:

Patient record, clinical dataset, threshold , max iterations

- 1:

Initialize , best Hamiltonian , feature set ,

- 2:

Encode patient features into (Eq. 11) - 3:

Prepare ansatz

- 4:

while and do

- 5:

- 6:

Generate trial Hamiltonian using feature correlations

- 7:

Evaluate via measurement - 8:

Compute classically - 9:

- 10:

if then

- 11:

- 12:

- 13:

- 14:

end if

- 15:

end while - 16:

return

|

The prediction

is then a binary decision derived from this quantum score by applying a classically optimized threshold

:

The goal shifts from finding a Hamiltonian that minimizes the

metric (Equation

12) for feature selection to finding the optimal pair (

) that minimizes a selected classification loss function,

, across the entire dataset.

The global optimization of and is driven by minimizing one of the three standard loss metrics in the iteration space.

1. Simple Error (

): Minimizes the total number of misclassified instances, equivalent to

, where the accuracy is the correct classification rate.

: The predicted class (0 or 1) for the j-th instance

: The true class (0 or 1) for the j-th instance

: The total number of instances (patients) in the dataset

: The indicator function, which equals 1 if the condition inside is true (, i.e., misclassification) and 0 otherwise

2. Balanced Error (

): Minimizes the error based on the average of sensitivity (true positive, TP, rate) and specificity (true negative, TN, rate), making it robust against class imbalance.

3. Penalized Error (

): Imposes a higher cost on false negatives (FN) compared to false positives (FP), often critical in medical diagnostics to avoid missing a condition.

: The total count of FN (instances that are actually positive, , but were predicted negative, )

: The total count of FP (instances that are actually negative, , but were predicted positive, )

The core routine involves a stochastic global search where, at each iteration, a random Hamiltonian is generated, all patient scores are computed, and a classical grid search is performed over the expanded range of possible scores (from

to

, where

N is the number of Pauli terms) to find the threshold

that minimizes the chosen loss function.

|

Algorithm 4: Global Multi-Qubit Classifier Search |

Require:

Clinical Dataset D, Target Status y, Loss Function L, Max Iterations M, Number of Pauli Terms N

- 1:

Initialize

- 2:

Pre-calculate normalization bounds for feature encoding - 3:

Define threshold grid

- 4:

for i=1 to M do

- 5:

Generate Trial Hamiltonian : - 6:

i. Randomly select N Pauli operators

- 7:

ii. Assign coefficients from random clinical feature correlations - 8:

Compute Scores : - 9:

For all patients : - 10:

Compute via the quantum ansatz and measurement routine (Eq. 4) - 11:

Optimize Threshold (Grid Search): - 12:

Find

- 13:

Compute

- 14:

if then

- 15:

- 16:

- 17:

- 18:

end if

- 19:

end for - 20:

return Optimal Classifier and

|

The output of the routine is the optimal clinical Hamiltonian and the optimal threshold that together minimize the predefined classification loss function. This final pair constitutes the predictive quantum classifier for the target clinical status.

2.3. Classical Benchmarks

To rigorously assess the performance and stability of the multi-qubit VQE approach, its results were benchmarked against a suite of strong classical machine learning models. This comparative analysis was conducted under a unified and robust validation scheme designed to address class imbalance, guarantee reproducibility across random conditions, and evaluate feature robustness.

The following models were selected as classical baselines for binary classification of the and status:

Regularized Logistic Regression (LogReg): A strong linear baseline, implemented using the brulee package (equivalent to the glmnet engine), which incorporates L2 regularization (penalty) to prevent overfitting and optimize the loss function.

Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP): A single-hidden-layer neural network, trained using the brulee package, which serves as a classical deep learning baseline that explicitly incorporates class weights to handle the data imbalance during optimization.

The entire modeling process, including feature preprocessing, hyperparameter tuning, and final evaluation, was nested within a rigorous, multi-seed validation loop to ensure result stability. The analysis was replicated across distinct random seeds. For each seed, a new 70/30 train/test split was performed, and the subsequent repeated Cross-Validation (CV) and final evaluation were executed. The final reported metrics are the mean and standard deviation across these N replicates. Hyperparameter tuning for all classical baselines (LogReg, MLP) was performed using 10 fold CV repeated 3 times on the training set. Model selection during CV was based on maximizing the Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUCPR), which is the most reliable metric for imbalanced data. The modeling pipeline utilized the tidymodels framework in R. All numeric predictors were standardized (), and zero-variance features were removed using the step_zv function.

Crucially, to address the severe class imbalance in the target variable, the Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE) was applied within the CV folds of the training set to balance the training data for the LogReg models. The MLP model was trained using explicit inverse class weights (inversely proportional to class frequency) instead of SMOTE, a common technique for gradient-based models, to directly influence the loss function toward the minority class.

To assess feature redundancy and the contribution of the quantum-derived features, an ablation study was conducted. The full validation pipeline (multi-seed CV and final test evaluation) was repeated for three distinct feature sets:

A Full Feature Set (using all available clinical and quantum-derived features).

A No Quantum Features Set (excluding features related to VQE payoffs, nearest payoff, and quantum structure).

A No Classical Features Set (excluding raw clinical differences, ratios, and counts).

The comparison of performance metrics across these ablated sets provides direct evidence of the feature stability and incremental value of the proposed features.

3. Results

The search algorithm was applied to three distinct clinical scenarios to identify the optimal, low dimensional clinical Hamiltonian . This Hamiltonian serves as a personalized quantum biomarker, where its ground state energy provides a measurable risk score, and its Pauli operator structure defines the most critical interaction (entanglement) between clinical features.

3.1. Stable Patient Scenario

This scenario establishes the clinical baseline, representing a patient with maximal resilience (no TB:

, no drug resistance:

). The patient’s quantum state

exhibits an ideal outcome state (

) despite active internal dynamics on qubit 1 (

). The search algorithm identified the simplest Hamiltonian, certifying the decoupling of the two-qubit system:

This Identity operator serves as the quantum stability identifier. The analytical delta () confirms that is an exact eigenstate of , resulting in a constant, intrinsic energy .

The result implies that the internal dynamics (qubit 1) do not structurally affect the ideal clinical outcome (qubit 2). The constant coefficient C is the system’s baseline energy, derived from the correlation of the highest competing, non-Identity term (), which is successfully neutralized by the patient’s state.

The principal clinical advantage of the

Hamiltonian is its zero measurement cost. Following standard VQE shot budgeting, the expected number of measurements

is proportional to the variance of the Pauli terms

[

21]. Since

, the prognostic shot budget is

. This demonstrates the ultimate cost-efficiency achieved when a patient’s state certifies maximal clinical resilience (

Table 1).

3.2. TB Co-Infected Patient Scenario

This scenario examines a patient with TB co-infection (). The patient’s state is characterized by structural stress, evidenced by a high risk outcome qubit encoding () despite currently stable viral load dynamics ().

The optimal search algorithm identified a single entanglement operator that certifies this instability:

This

operator, with

, is the quantum strategy interaction identifier (

Table 2). The low analytical delta (

) confirms a strong alignment between the patient state and this Hamiltonian’s eigenstate, signifying structural instability by establishing a measurable, inverse correlated entanglement between key features.

The Hamiltonian functions as a feature reduction filter, isolating the crucial interaction between: (the latent high risk Hadamard strategy for the low replicating viral phenotype) and (the active biomarker of viral load dynamics).

Unlike the scenario, the operator requires a non zero shot budget to overcome the finite sampling error (FSE) inherent to quantum measurement.

The

shots used in the search phase were an optimization cost to ensure the

Hamiltonian was reliably discovered with minimal FSE. The prognostic shots are the operational cost for the final, single measurement. The required shots for clinical grade precision (

) are calculated as:

This cost quantifies the added complexity introduced by the co-infection. For resource constrained NISQ deployment, relaxing the tolerance to

reduces the cost significantly:

This demonstrates the critical trade-off between clinical precision and hardware budget [

53].

3.3. Drug Resistance (GR) Scenario

This scenario investigates a patient with resistance to treatment (). The patient’s state is highly unstable, characterized by significant viral load increase and CD4 decrease. The encoding shows the instability is primarily contained within the internal dynamics (qubit 1: ).

The optimal search identified an entanglement operator defining the instability:

This

operator is the quantum conditional payoff identifier. The highly accurate analytical delta (

) validates the Hamiltonian as the minimal energy operator, verifying a deep, inverse correlated structural instability linked to viral fitness (

Table 3).

The Hamiltonian’s features are: (the latent defensive X strategy for the high replicating phenotype) and (the classical viral fitness score/reproductive capacity).

The negative coefficient () shows that the patient’s drug resistance is defined by an inverse correlation where the viral phenotype’s maximum classical survival capacity () suppresses its necessity to adopt a critical defensive strategy (). This is an active strategic instability.

Prognosis requires measuring : a value near confirms the persistence of this conditional instability, while a shift towards zero (loss of inverse correlation) would signal a phase transition in the viral strategy, requiring intervention.

As with the TB scenario, the

operator requires a substantial budget for high assurance prognosis. The

search shots again serve as a high fidelity optimization step. The operational budget is calculated for

:

This ≈ 10,500 shot requirement quantifies the cost of measuring the instability introduced by drug resistance. For routine monitoring, relaxing the precision to

drastically reduces the shot budget:

This illustrates that the clinical Hamiltonian provides clinicians with a direct, quantifiable mechanism to choose the cost-efficiency strategy based on the required risk tolerance .

3.4. Classification Results

The multi-qubit VQE framework was deployed as a global binary classifier to predict two critical clinical statuses: the genotypic drug resistance status () and TB co-infection (). The routine utilizes a single-term Hamiltonian () , optimized over 10,000 iterations to minimize a chosen classification loss function. In both scenarios, the dataset is severely imbalanced, making balanced accuracy the key performance metric.

The target class, , consists of 8 positive cases out of 176 patients (prevalence ). The four features encoded into the two-qubit ansatz were: , , , and .

The multi-qubit quantum classifier was optimized to minimize three distinct loss functions: simple error, balanced error, and penalized error. The performance of the optimal classifier

found for each loss function is presented in

Table 4.

The classifier optimized with the balanced error loss function yielded the best performance, achieving a balanced accuracy of . This model correctly identified 7 out of the 8 drug-resistant patients (Sensitivity) while maintaining a high true negative rate (Specificity). The poor performance of the simple error model (Sensitivity) highlights the necessity of using loss functions robust to class imbalance in medical diagnostics.

The second task targeted the prediction of the

co-infection status, which is even more imbalanced, with only 6 positive cases out of 176 patients (prevalence

). For this prediction, the encoded features were modified to be:

,

,

(using the final status as a predictor), and

. The performance of the optimal classifier

for the

prediction is shown in

Table 5.

Similar to the scenario, the classifier optimized for simple error yielded a misleading accuracy but had low sensitivity (0.167), correctly identifying only 1 out of 6 TB-co-infected patients. The penalized error also failed to achieve robust sensitivity (Sensitivity).

The best predictive performance for was achieved using the balanced error loss function, with a balanced accuracy of . This model successfully identified 4 out of 6 co-infected patients (Sensitivity) while maintaining a high specificity of 0.894.

While the balanced accuracy for () is lower than that for (), this result is highly significant given the extreme imbalance and the difficulty of predicting TB co-infection using standard clinical markers. The single-term quantum classifier demonstrates an ability to leverage quantum encoded features and their correlations to distinguish between the minority and majority classes with substantial predictive power.

3.5. Comparative Analysis with Classical Baselines

To rigorously evaluate the strength of the VQE approach, its performance was benchmarked against standard classical models (LogReg and MLP) trained using inverse class weights to mimic the "Balanced Error" optimization and mitigate class imbalance. The results of these classical baselines are summarized in

Table 6.

The classical models demonstrated a high overall accuracy ( for and between and for ) but showed a significant bias toward the majority class for . Specifically, for the variable, both LogReg and MLP failed to correctly identify any patient in the minority class (Sensitivity ), resulting in a Balanced Accuracy below the random chance level ().

For the variable, the classical baselines showed better, but still limited, performance. The LogReg achieved a Balanced Accuracy of , while the MLP achieved . Although the MLP attained the same Sensitivity () as the VQE, this was achieved by significantly sacrificing Specificity (). In contrast, the VQE model optimized with the Balanced Error loss significantly outperformed all classical methods, achieving a Balanced Accuracy of while maintaining both high Sensitivity () and high Specificity (). These results suggest that the VQE approach effectively utilizes the complex clinical and quantum-derived features to better resolve the minority class without compromising the correct classification of the majority class, a key requirement for reliable clinical risk scoring.

While the balanced accuracy for () is lower than that for (), the consistent and significant outperformance of the VQE model over all classical baselines across both imbalanced targets validates the utility of quantum-derived features in this clinical domain. The VQE’s ability to maintain high sensitivity while preserving high specificity suggests that the feature encoding and Hamiltonian learning successfully capture latent, clinically relevant correlations that are inaccessible to conventional models, providing a superior basis for reliable clinical risk scoring.

4. Discussion

The variational quantum approach, extended here to a multi-qubit framework, has demonstrated significant potential as an interpretable feature discovery and classification tool for complex clinical data, specifically in the highly challenging domain of HIV/TB co-infection and drug resistance.

The present work successfully extends the methodology proposed in earlier single-qubit analyses, which were limited to encoding only two clinical features into the parameters of a state

[

49]. While the single-qubit model validated the core concept that a clinical Hamiltonian’s ground state could be used as a classification boundary, its practical application was inherently limited by its low expressivity, failing to capture the complex, multi variate correlations common in biological systems.

The transition to a multi-qubit ansatz with an entangling gate (as shown in Algorithm 3) addresses this limitation. By encoding four clinical features (, , and or ) into the state , the model explores a vastly richer Hilbert space. The introduction of the entangling gate is crucial, as it allows the quantum state to encode non-linear correlations between features, which are believed to be essential for accurate prediction of multiple factor diseases and drug resistance. This architectural expansion is the critical step that permits the identification of a single-term Pauli operator, , that acts as a robust classifier.

The success of the multi-qubit model is profoundly linked to the advanced feature engineering derived from the quantum game of infectious phenotypes [

52]. By converting complex biological dynamics, like the competition of HIV-1 phenotypes, into single, clinically meaningful, one-hot encoded variables (e.g.,

,

, or

), the model achieves two primary goals. The first one is an interpretability through dimensionality reduction. This abstraction limits the effective feature space, enabling the optimal Hamiltonian to be found as a minimal single-term operator. A Hamiltonian like

(for the TB scenario) or

(for the stable patient) is highly interpretable, as its single term and coefficient immediately indicate the key clinical biomarker combination driving the patient’s state towards the minimal energy. The secon goal concerns the dentification of clinical biomarkers. The results of the multi-qubit (

Table 1,

Table 2 and

Table 3) model demonstrate how the model pinpoints the specific, most relevant pair of clinical and quantum derived features that define the patient’s state (i.e., the variables coupled by the optimal Pauli operator

).

A key aspect enabling the high performance and interpretability of this model is the incorporation of a feature derived from quantum game theory: the . This is a powerful example of feature engineering where complex, multi-dimensional information (specifically, the competitive dynamics between HIV-1 phenotypes) is abstracted into a single, clinically relevant measure.

By including this one-hot encoded quantum strategy (as a quantum derived feature), the total number of necessary clinical features for robust classification is kept low, which in turn limits the complexity of the optimal Hamiltonian found by the optimal clinical Hamiltonian search algorithm. This reduction in the feature space for the Hamiltonian enhances clinical interpretability, directly highlighting the most influential pairwise correlation for the target outcome offering a clear, interpretable biomarker. Fewer terms in the Hamiltonian lead to fewer required measurements for estimating the expectation value

, minimizing the effects of sampling error, a critical challenge in the NISQ era [

53].

The classification results validated the efficacy of the multi-qubit model. Given the severe class imbalance in the dataset (positive cases were for and for ), the standard simple error loss function proved clinically misleading, favoring high accuracy and specificity at the expense of nearly zero sensitivity (e.g., Sensitivity for ).

The optimization based on the balanced error loss function, however, delivered highly relevant diagnostic results. For the status, a balanced accuracy of successfully identifying 7/8 drug-resistant patients (Sensitivity). For the status, a balanced accuracy of , successfully identifyied 4/6 co-infected patients (Sensitivity).

This performance confirms that the proposed quantum classifier can effectively distinguish between minority and majority classes by focusing on the underlying feature correlations, thereby providing a clinically valuable result that overcomes the limitations of traditional models in imbalanced settings.

While the performance metrics validate the hybrid quantum-classical methodology, it is essential to acknowledge specific limitations regarding the clinical cohort and data collection process. Firstly, the dataset is derived exclusively from a single, regional HIV clinic in Guerrero, Mexico. This homogeneity, while useful for controlling local treatment and epidemiological factors during training, inherently limits the generalizability (external validity) of the final model. The precise numerical values of the optimal Hamiltonian coefficients may be specific to the regional strain variants or local clinical protocols, and may not directly translate to cohorts from other geographical areas.

Secondly, the use of longitudinal clinical records (2018-2024) introduces potential selection biases. Patients who maintain consistent follow-up and remain in the cohort over extended periods tend to be more treatment-adherent or may represent a subpopulation with inherently better long term outcomes. Furthermore, the necessary data depuration process, which excluded records lacking multiple longitudinal measurements, further restricted the final analytical base to those patients with documented temporal dynamics, potentially biasing the model toward compliant, multi-visit individuals.

To address these limitations, our immediate future work is focused on external validation of the trained model. The next step is to test the structural validity of the discovered quantum biomarker, meaning the specific pair of clinical features and the Pauli operator that yields the optimal classification (e.g., coupling and for TB). The plan is to apply the trained classifier to independent, distinct cohorts from other states in Mexico or from international public repositories, such as those made available through the NIH. This external validation will confirm whether the identified feature relationships () are universal clinical biomarkers or are merely artifacts of the local training cohort, thereby establishing the model’s true external reliability for precision medicine applications.

The successful application of this multi-qubit entangling ansatz to a real world imbalanced biomedical classification problem, is a powerful demonstration of the potential of variational quantum algorithms in the NISQ era [

4]. The model leverages the strengths of quantum computation, the capacity for expressive state preparation and the efficient estimation of Hamiltonian expectation values, while keeping the circuit depth and number of required qubits minimal.

As quantum hardware continues to improve, the move from this two-qubit system to models with qubits will naturally pave the way for further, more accurate models. Higher-qubit ansätze will allow for the encoding of even more clinical and omics features, while the fundamental clinical Hamiltonian principle will continue to serve as a powerful engine for identifying optimal, interpretable, and parsimonious biomarker combinations. This hybrid quantum-classical approach thus represents a promising direction for achieving the goal of precision medicine through quantum machine learning.