1. Introduction

Mental manipulation is the intentional use of language to influence or control someone’s thoughts, emotions, or decisions [

1]. These manipulative techniques can be subtle and difficult to detect, making them a significant challenge for both humans and artificial intelligence (AI) systems [

2,

3]. As large language models (LLMs) become increasingly integrated into digital communication, ensuring that these models can recognize and mitigate manipulative language is crucial for preventing misinformation, exploitation, and unethical persuasion As discussed by [

4].

Recent efforts, such as MentalManip [

5], have primarily focused on detecting manipulative intent within English-language conversations [

6,

7]. Studies evaluating models like GPT-4 Turbo, LLaMA-2-13B, and RoBERTa-base have revealed that state-of-the-art LLMs struggle to reliably identify manipulative content due to the inherently subjective nature of annotation and the complexity of linguistic manipulation [

2].

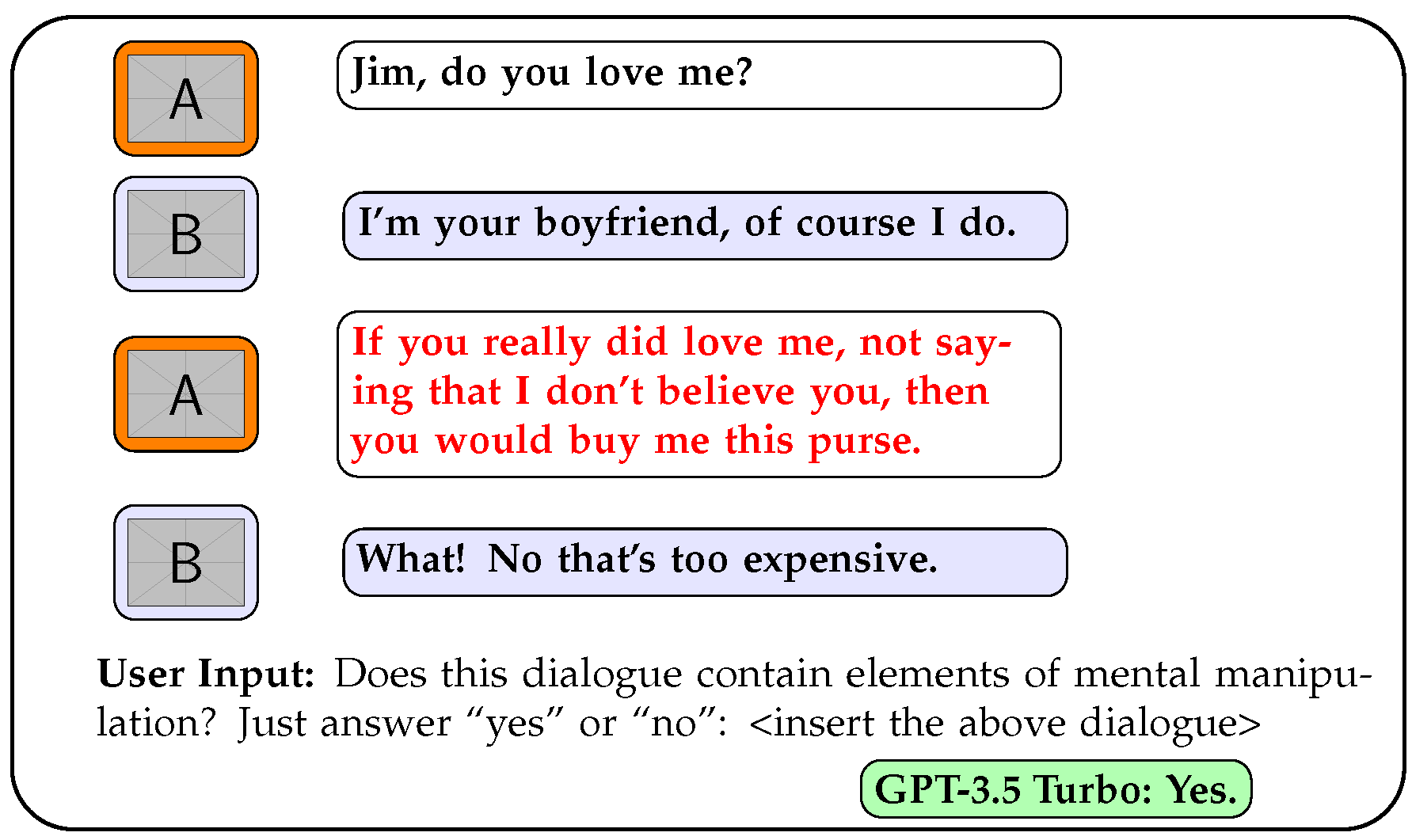

Figure 1.

Example of conversation analysis by ChatGPT 3.5-Turbo.

Figure 1.

Example of conversation analysis by ChatGPT 3.5-Turbo.

Our research seeks to address this gap by introducing CultureManip, a multilingual benchmark designed to explore how mental manipulation manifests across different languages. Unlike previous studies that focus solely on English, our work investigates the performance of LLMs in detecting manipulation across linguistic structures and cultural contexts.

To achieve this, we conduct experiments using ChatGPT-3.5 Turbo [

8] , evaluating its performance under zero-shot prompting. By examining the cross-linguistic aspects of mental manipulation, our research contributes to the development of more robust AI moderation systems, ultimately fostering safer and more ethical AI-assisted communication across a multilingual spectrum.

2. Related Work

Recent efforts to detect mental manipulation in language have focused heavily on evaluating and improving large language models (LLMs) using the MentalManip dataset Wang et al. [

5]. This dataset was used to conducted baseline evaluations using models like GPT-4 Turbo and LLaMA-2-13B. Their findings revealed that current state-of-the-art models struggle with reliably identifying manipulative content. The annotation process, being inherently subjective, introduces potential inconsistencies that may not align with broader societal perceptions of verbal manipulation. Furthermore, [

9] demonstrated the difficulty for LLMs to classify fine-grained sarcasm, highlighting the shortcoming of LLMs in detecting human conversational nuance.

Extended work on this topic examined the performance of LLMs using prompting strategies, particularly Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting [

7]. Their results demonstrated that CoT without example-based learning (i.e., zero-shot CoT) underperformed relative to simpler prompting strategies as model complexity increased.

More recently, a new novel prompting approach was proposed: Intent-Aware Prompting (IAP) [

6]. This prompting technique is aimed at improving the detection of mental manipulation by emphasizing the intent behind statements. IAP provided better performance over existing prompting techniques, notably through a substantial reduction in false negatives. The authors recommend the development of a more diverse and representative dataset to improve the generalization of future models.

3. Constructing CultureManip

3.1. Taxonomy

To construct our dataset, CultureManip, we based off of MentalManip [

5]. In which our data is separated into 5 columns representing:

ID: the identification number for each conversation block

Conversation: Each conversation block

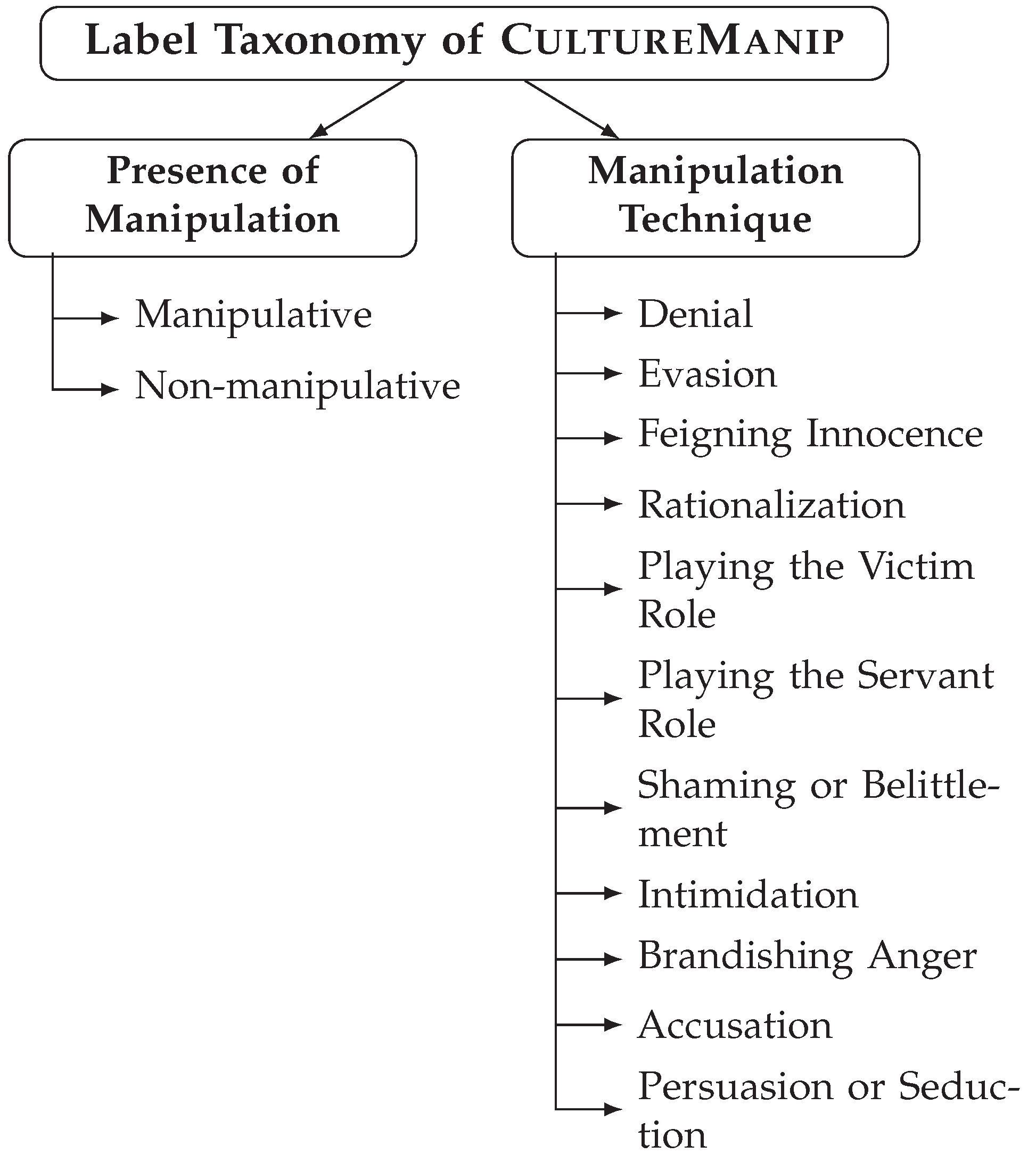

Presence of Manipulation: Decide whether manipulative or not. (1 for manipulative, 0 for non-manipulative) Represents the Presence of Manipulation line in

Figure 2.

Manipulation Dialogue: whichever line(s) that specify manipulation

Manipulation Technique: Decide what type of manipulation(s) are present based on the CultureManip taxonomy sheet (

Figure 2) [

5].

Our taxonomy sheet is a replica of the taxonomy sheet shown in MentalManip however, we did not implement the Targeted Vulnerability aspect. To ensure clarity, we used the definitions given through the MentalManip paper for each manipulation technique [

5].

3.2. Data Source and Preprocessing

To support our multilingual analysis, we utilized dialogue data from the OPUS corpus [

10], an open collection of parallel corpora available at

https://opus.nlpl.eu. Specifically, we extracted data in four languages: English, Spanish, Chinese, and Tagalog.

We used ChatGPT-3.5 Turbo to organize raw dialogue data into conversation blocks by grouping contiguous lines from the same exchange. Each block, representing a short conversation with two or more participants, was then formatted into rows in a spreadsheet.

3.3. Human Annotation

To identify instances of mental manipulation within our multilingual dataset, we enlisted two native-speaking annotators for each target language: English, Spanish, Chinese, and Tagalog. Each annotator was provided with a structured spreadsheet with 100 conversations.

The annotation protocol was standardized across languages, with annotators following shared instructions. For each conversation in Column B, annotators identified manipulative lines, transcribing them into Column C. Column D indicated manipulation presence (1 for manipulative, 0 for non-manipulative), and Column E contained selected manipulation techniques from a predefined taxonomy, including labels like Intimidation, Brandishing, and Anger. An example annotation is shown below:

Conversation Block: “You’re impossible, you would even delude a saint! I will divorce you!”

Manipulative Dialogue: “You’re impossible, you would even delude a saint! I will divorce you!”

Presence of Manipulation: 1

Manipulation Techniques: Intimidation, Brandishing, Anger

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Setup

We conducted experiments in English, Spanish, Chinese, and Tagalog to measure the ability of LLMs to detect manipulation on a multilingual level. Like the human annotators, the LLM was tasked to give a binary response for each conversation, indicating whether there was presence of manipulation. All baseline experiments were carried out using zero-shot prompting, asking the model to read the conversation and detect whether manipulation is present or not, with temperature and top P set at 0.3, as we found that these two values produced the most consistent answers.

We then used a raw inter-annotator agreement score (percentage agreement) to check for agreement between human-human and human-LLM. This was calculated by counting how many times both annotators assigned the same label to a conversation, then dividing by the total number of conversations. The result is a percentage, with a score closer to 1 indicating high agreement and closer to 0 indicating little agreement. In essence, the inter-annotator agreement score represents the raw agreement between annotators or between a human and the model.

4.2. Results

Overall, the results indicate that English remains the language with the highest agreement between the LLM’s predictions and human judgments, which aligns with expectations given the predominance of English data in the model’s training data. The model’s performance decreases progressively with Spanish, Chinese, and especially Tagalog, indicating that performance decreases from high resource to low resource languages.

Table 1.

Inter-annotation agreement Scores for different Languages. Group 1 is between two human annotators. Group 2 is between ChatGPT-3.5 Turbo and two human annotators.

Table 1.

Inter-annotation agreement Scores for different Languages. Group 1 is between two human annotators. Group 2 is between ChatGPT-3.5 Turbo and two human annotators.

| Language |

Group 1 |

Group 2 |

| English |

62% |

48% |

| Spanish |

76% |

41% |

| Tagalog |

37% |

20% |

| Chinese |

50% |

28% |

Our language selection—three major languages (English, Spanish, and Chinese) paired with a lower-resource language (Tagalog)—was intentional to highlight this disparity. These findings are consistent with recent research such as the MEGAVERSE benchmark [

11] and StringrayBench [

12], both of which shows that large language models tend to perform significantly better on classification tasks like sentiment analysis and named entity recognition in high-resource languages, while struggling on lower-resource languages like Tagalog.

Between English and Spanish, the agreement was relatively higher (62% and 76%, respectively), indicating a moderately strong consensus between annotators. This suggests that the annotators generally shared similar interpretations and criteria when evaluating dialogues in these languages. The higher agreement in Spanish, even exceeding that in English, could be due to clearer linguistic markers or less ambiguity in the sample dialogues, which is confirmed by both annotators.

In contrast, the agreement dropped substantially for Chinese (50%) and was lowest for Tagalog (37%). The lower agreement scores suggest increased difficulty and ambiguity in annotating manipulation in these languages, which was confirmed by testimonies of the annotators (see Appendix).

5. Multilingual Analysis

Spanish Spanish-speaking cultures rely on high-context communication, using implicit cues and shared background, while English communication is more direct [

13]. This cultural difference makes subtle manipulative signals in Spanish harder for GPT-3.5 Turbo, which is primarily trained on English data, to detect [

8]. As a result, LLMs like GPT-3.5 Turbo, dependent on surface-level features, struggle to identify subtle manipulation [

14]. Moreover, the collectivist values and indirect communication in Spanish cultures, as noted by Hofstede [

15], and the use of complex rhetorical features like politeness and figurative language [

16], further complicate manipulation detection, leading to lower agreement scores in Spanish than in English.

Tagalog Detecting manipulation in Tagalog is challenging due to the indirect communication style of Filipino culture, where Filipinos often avoid direct confrontation to preserve hiya (shame) and prevent loss of face, using subtle hints and ambiguous language instead [

17,

18]. This indirectness obscures manipulative intent, making it hard to identify manipulation through text alone. Additionally, the cultural value of Pakikisama, which emphasizes social harmony and conformity, leads individuals to avoid open disagreement [

19]. This can bias annotators, causing them to overlook manipulative behaviors. Our annotation experience reflected these challenges, with low inter-annotator agreement and high subjectivity, particularly for Tagalog conversations. Language models like GPT-3.5 Turbo, trained on more explicit languages, also struggle with these subtleties.

Chinese In Chinese culture, maintaining face (miànzi) is a key social value, leading to indirect communication that conceals manipulative intent through nuanced language, body language, and implied meanings rather than direct statements [

20,

21,

22]. This cultural indirectness makes detecting manipulation from text alone challenging, as nonverbal cues like tone and facial expressions are absent. Models like GPT-3.5 Turbo, which rely on surface-level textual patterns and lack cultural grounding, struggle to interpret these subtleties [

14,

20,

21,

22]. Additionally, [

23] highlights that LLMs tend to overestimate performance, especially in non-Latin languages like Chinese, due to biases and lack of cultural understanding, making reliable manipulation detection difficult for both humans and LLMs.

6. Future Work and Conclusions

This study introduces CultureManip, a new multilingual benchmark for detecting verbal manipulation across languages. Using annotated conversational data, we examined how well models like GPT-3.5 Turbo identify manipulation. Results revealed significant differences in detection accuracy between languages, reflecting cultural variation and the subjective nature of manipulation. These findings echo prior research and highlight the need for more culturally adaptive models. Current LLMs, often trained primarily on English, show reduced effectiveness in other languages—underscoring the importance of multilingual, culturally sensitive approaches to manipulation detection.

Future work should refine datasets and develop standardized annotation guidelines to improve consistency across languages. Studying cross-lingual generalization can reveal shared or language-specific manipulation patterns [

24]. Incorporating multimodal data—such as tone or gestures—may boost accuracy by adding context [

25]. To address subjectivity and bias in monolingual data, localized guidelines are essential. Exploring sources like podcast transcripts or real conversations may also yield more natural dialogue than subtitle-based data.

Although detecting manipulation is a challenging task, both for humans and LLMs, the development of CultureManip serves as a foundational step in advancing multilingual manipulation detection. As LLMs continue to evolve, it will be crucial to assess the capabilities of smaller, more specialized models for this task. By making CultureManip publicly available, we hope to inspire further research and innovation in the field, encouraging the development of more accurate, context-aware, and culturally sensitive manipulation detection systems. This work lays the groundwork for future efforts aimed at improving the reliability of LLMs in detecting manipulation across diverse languages and cultural contexts.

Limitations

CultureManip has several limitations. First, data annotation is subjective, with cultural perception further complicating accurate manipulation identification. Although annotators were trained for objectivity and required to specify manipulation types, limited fluency in certain languages sometimes led to misclassifications.

Second, data sources are drawn from movie scripts, which are often stylized and exaggerated, limiting their representativeness of real-life conversations. While covering various genres, the benchmark may still reflect biases in script conventions that don’t capture the full range of manipulative speech in everyday contexts.

Lastly, cultural context influences how manipulation is perceived. Different cultural norms affect how manipulative behavior is categorized, leading to potential subjectivity in labeling, as certain behaviors seen as manipulative in one culture might be overlooked or misunderstood in another.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The benchmark was created from publicly available movie scripts, focusing on common communication forms like persuasion and emotional manipulation. Human annotators from diverse linguistic backgrounds voluntarily labeled the dialogues for manipulation, following ethical guidelines to ensure anonymity and fairness. Annotators were trained to identify linguistic cues without assuming characters’ intent, considering cultural and contextual nuances. While the benchmark covers various genres and settings, it may not fully represent all cultural contexts, and future work aims to expand its diversity. The project emphasizes responsible research and ethical use, cautioning about the sensitive implications of automating manipulation detection.

Appendix A. Annotator Testimonies

Tagalog Annotator A: “I didn’t find a lot of manipulative stuff in the dialogue so far, but maybe I’m too selective? I think in the context that some are used, it’s not manipulation. But I checked the Annotator B file and they were picking lines that sometimes might be manipulative, but not really.”

Tagalog Annotator B: “It was not easy because the Tagalog was not translated well. Also, the reader eventually figured out what the story was. I am not sure if that’s intentional, but having some idea of the story influenced the identification process of manipulation. The reader may be prone to reasoning why such statements were made and make their own justifications (unintentional but natural bias).”

Spanish Annotator A: Reading from the dialogues, I could easily tell that they were manipulative. What gave it away was the fact that they included tons of name-calling and belittlement. Checking through these conversations, I can tell the mood and tone of the dialogues. They contained exclamation points, sarcasm, and irony. This is where I figured the conversations were not nice.

Spanish Annotator B: I think it was easy to tell that most of the text was manipulative. It fit a lot of the categories given, and there was a lot of harsh language being used, which made it obvious to me that it was a manipulation.

English Annotator A: I personally found it pretty hard. It was extremely sutble for some conversation, to the point where I can make an argument for both and convince myself. The manipulation wasn’t the kind that was used to control people and insult them. It was more subtle than that, so I think that ChatGPT wouldn’t, or rather couldn’t, do that well, but I don’t know.

English Annotator B: I think most of the text was easy to tell, especially in their specific contexts. Although it might have been unclear exactly what was happening, there was a lot of chaos and dialogue that had a strong sense of manipulation that were fitting of the categories given through the taxonomy sheet.

Chinese Annotator A: I think a lot of the conversations provided had very subtle forms of Mental Manipulation. I lot of the lines weren’t using mental manipulation specifically to take advantage of another person, but would fit into a lot of the categories given through the taxonomy sheet. In that sense, I believe it was a bit harder to see manipulation, and what people perceive as mental manipulation is more subjective.

Chinese Annotator B: It was a mix of good and bad. Yeah there were some conversation that were obviously manipulative, but also a good amount of conversations that could be argued for not manipulative. Overall, pretty subjective.

Appendix B. Prompting

Zero-Shot Prompt

Zero-shot prompting format:

’’’

I will provide you with a dialogue.

Please determine if it contains elements

of mental manipulation. Just answer with

’Yes’ or ’No’, and don’t add anything else.

<insert dialogue>

’’’

References

- Barnhill, A. What is manipulation. Manipulation: Theory and practice 2014, 50, 72. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, I.; Hassanpour, S.; Vosoughi, S. MentalManip: A dataset for fine-grained analysis of mental manipulation in conversations. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.16584 2024.

- Ienca, M. On Artificial Intelligence and Manipulation. Topoi 2023, 42, 833–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, W.; Xu, W.; Xu, M.; Yang, N.; Zhou, B.; Duan, N.; Zhao, D.; Wu, Y.; et al. LLM Can be a Dangerous Persuader: Empirical Study of Persuasion Safety in Large Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.10430 2025.

- Wang, Y.; Yang, I.; Hassanpour, S.; Vosoughi, S. MentalManip: A Dataset For Fine-grained Analysis of Mental Manipulation in Conversations. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers); Ku, L.W.; Martins, A.; Srikumar, V., Eds., Bangkok, Thailand, 2024; pp. 3747–3764. [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Na, H.; Wang, Z.; Hua, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, W.; Chen, L. Detecting Conversational Mental Manipulation with Intent-Aware Prompting, 2024, [arXiv:cs.CL/2412.08414].

- Yang, I.; Guo, X.; Xie, S.; Vosoughi, S. Enhanced Detection of Conversational Mental Manipulation Through Advanced Prompting Techniques, 2024, [arXiv:cs.CL/2408.07676].

- Brown, T.B.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.; Dhariwal, P.; ....; Amodei, D. Language Models are Few-Shot Learners. arXiv preprint arXiv:2005.14165 2020.

- Xiong, L.; Gao, R.; Jeong, A. Sarc7: Evaluating Sarcasm Detection and Generation with Seven Types and Emotion-Informed Techniques. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 9th Widening NLP Workshop; Zhang, C.; Allaway, E.; Shen, H.; Miculicich, L.; Li, Y.; M’hamdi, M.; Limkonchotiwat, P.; Bai, R.H.; T.y.s.s., S.; Han, S.S.; et al., Eds., Suzhou, China, 2025; pp. 157–166.

- Tiedemann, J. Finding Alternative Translations in a Large Corpus of Movie Subtitles. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 12th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics (EACL 2009). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2009, pp. 449–457.

- Ahuja, S.; Aggarwal, D.; Gumma, V.; Watts, I.; Sathe, A.; Ochieng, M.; Hada, R.; Jain, P.; Ahmed, M.; Bali, K.; et al. MEGAVERSE: Benchmarking Large Language Models Across Languages, Modalities, Models and Tasks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2024 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (Volume 1: Long Papers); Duh, K.; Gomez, H.; Bethard, S., Eds., Mexico City, Mexico, 2024; pp. 2598–2637. [CrossRef]

- Cahyawijaya, S.; Zhang, R.; Lovenia, H.; Cruz, J.C.B.; Gilbert, E.; Nomoto, H.; Aji, A.F. Thank You, Stingray: Multilingual Large Language Models Can Not (Yet) Disambiguate Cross-Lingual Word Sense, 2024, [arXiv:cs.CL/2410.21573].

- Hall, E.T. Beyond Culture; Anchor Books, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Deroy, A.; Maity, S. HateGPT: Unleashing GPT-3.5 Turbo to Combat Hate Speech on X, 2024, [arXiv:cs.CL/2411.09214].

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions and Organizations Across Nations; Sage Publications, 2001.

- Avila, M.; Gomez, J. Cultural Influences in Natural Language Processing: Challenges and Opportunities. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 2023, 44, 245–260. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, A. Language and Culture in the Philippines; Asian Cultural Press: Manila, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tupas, R.F. Hiya and Cultural Control in the Philippines. Asian Journal of Social Science 2015, 43, 490–512. [Google Scholar]

- Salazar, Z.A. Pakikisama and Social Harmony in Filipino Culture. Philippine Journal of Psychology 2011, 44, 45–67. [Google Scholar]

- Ting-Toomey, S.; Kurogi, A. Facework competence in interpersonal conflict: A cross-cultural comparison of Chinese, Japanese, and American cultures. Communication Research 1998, 25, 567–590. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, T.; Faure, G.O. Chinese communication characteristics: A yin yang perspective. International Business Review 2010, 19, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffman, E. Interaction ritual: Essays on face-to-face behavior; Anchor Books, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Hada, R.; Gumma, V.; de Wynter, A.; Diddee, H.; Ahmed, M.; Choudhury, M.; Bali, K.; Sitaram, S. Are Large Language Model-based Evaluators the Solution to Scaling Up Multilingual Evaluation? In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EACL 2024; Graham, Y.; Purver, M., Eds., St. Julian’s, Malta, 2024; pp. 1051–1070.

- Ma, W.; Zhang, H.; Yang, I.; Ji, S.; Chen, J.; Hashemi, F.; Mohole, S.; Gearey, E.; Macy, M.; Hassanpour, S.; et al. Communication Makes Perfect: Persuasion Dataset Construction via Multi-LLM Communication. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2025 Conference of the Nations of the Americas Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (Volume 1: Long Papers), 2025, pp. 4017–4045.

- Herring, S.C. New frontiers in interactive multimodal communication. In The Routledge handbook of language and digital communication; Routledge, 2015; pp. 398–402. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).