Background

Modifiable risk factors, such as poor dietary intake and physical inactivity, are the leading causes of death and disability from non-communicable diseases.(WHO, 2023) The Global Burden of Disease study estimates dietary risk factors, including low intake of fruit and vegetables and high consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages, and physical inactivity were collectively responsible for 12 million deaths and 271 million disability adjusted life years.(Afshin et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2022)

As these risk factors track from childhood into later life,(García-Hermoso et al., 2022; Zheng et al., 2018) leading health organisations and countries internationally have released preventive health strategies that support healthy eating and physical activity in young children.(NHMRC, 2013; Tremblay et al., 2017; WHO, 2003) Early childhood and education care (ECEC) services are one setting in which population dietary intake and physical activity levels of children can be addressed at a critical developmental stage. ECEC services are regulated facilities which care for children aged 0-6 years prior to attending compulsory schooling, including long day care, preschools, nurseries, kindergartens and family day care (also known as family child care homes). In many developed countries, ECEC services are the primary setting outside of home where young children spend a significant portion of their time.(OECD, 2023)

Many high-income countries and health organisations have published guidance outlining best-practice recommendations to create ECEC environments supportive of child diet and physical activity.(Jackson et al., 2021) Examples of recommendations include offering a variety of food awareness/education activities and providing opportunities for adult-led, structured physical activity.(Jackson et al., 2021) An assessment of the methodological quality of the guidelines indicated a lack of reporting of how evidence was gathered or used to develop the recommendations.(Jackson et al., 2021)

Since the release of such ECEC-specific guidelines, there has been growth in high-quality empirical research evidence in this area.(Lum et al., 2022; Yoong et al., 2023) The examination of this new evidence is needed to understand and prioritise recommendations for implementation within the sector, as recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO).(WHO, 2021) The WHO toolkit, published in 2021, outlines global standards in ECEC settings to support the implementation of the WHO guidelines on healthy eating, physical activity, sedentary behaviour and sleep in young children.(WHO, 2021)

Therefore, this study sought to examine this evidence building on the common practice elements approach which has been used to identify important evidence-based elements for early childhood development.(McLeod et al., 2017; Garland et al., 2010) This approach seeks to identify shared, active components across multiple evidence-based interventions, rather than focusing on single branded programs. Such an approach is intended to promote flexibility for scaling by allowing selection of components most relevant to the local context and support the development of training and implementation strategies by focusing on a ‘set’ of universal components. Drawing on systematic review and randomised controlled trial (RCT) evidence, the aims of this study are to describe a novel systematic evidence-mapping process which: i) examines the evidence-base underpinning ECEC-based healthy eating and physical activity practice elements; and ii) classifies practice elements according to the WHO Standards for Healthy Eating, Physical Activity, Sedentary Behaviour and Sleep in Early Childhood and Care Settings to examine alignment with current global guidelines.

Methods

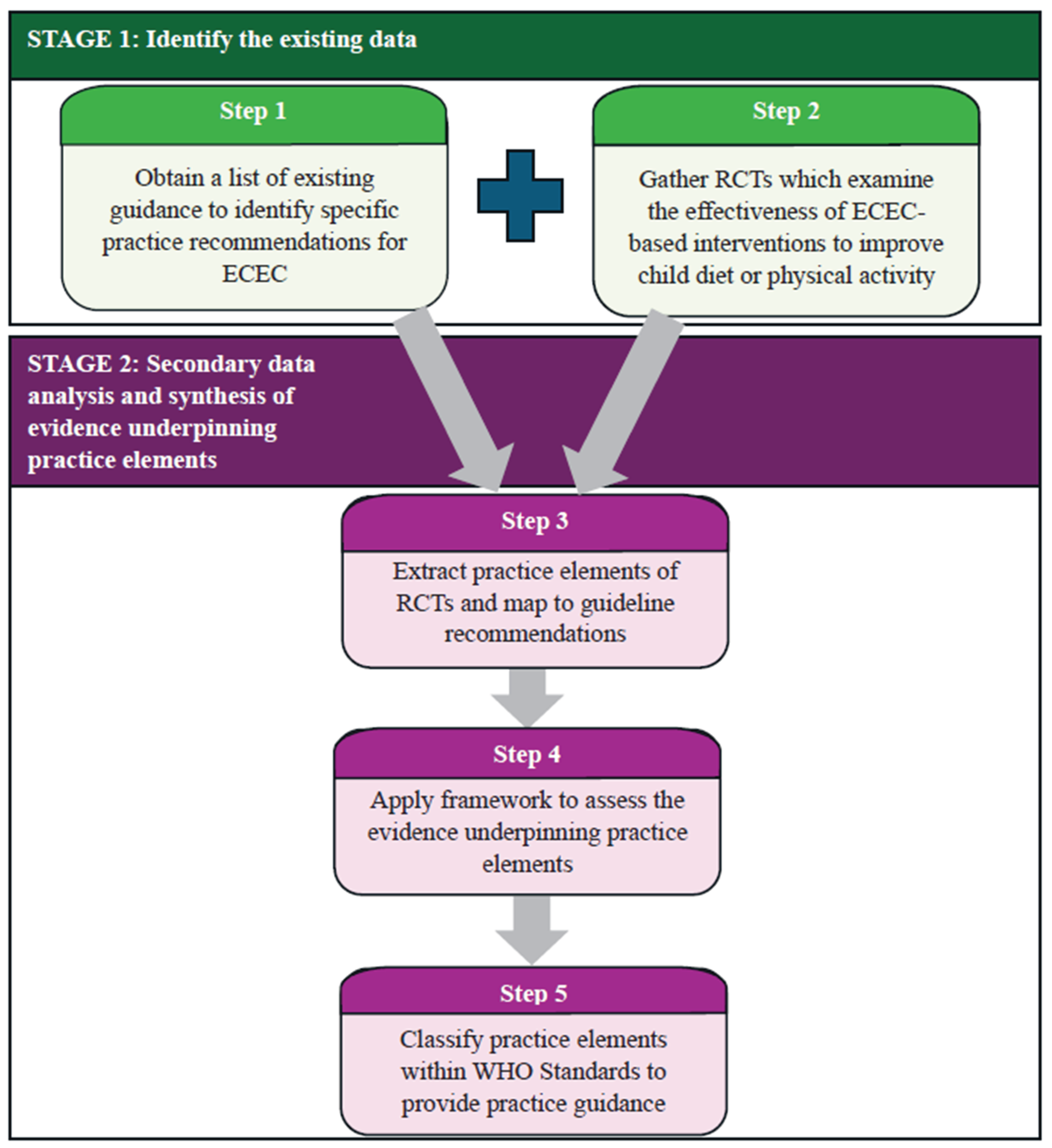

Similar to the common practice elements approach, this study employed a two-stage, five-step evidence-mapping process using secondary data extracted from published RCTs included within high quality, contemporary systematic reviews (

Figure 1). Due to the nature of this study, ethical approval was not required, nor sought.

Stage 1: Identify the existing evidence base

Step 1: Obtain a list of existing guidance to identify specific practice recommendations for ECEC

We obtained a list of broad practice themes and recommendations based on the results of a previous systematic review of 38 ECEC-based healthy eating and physical activity guidelines and policies conducted by the team.(Jackson et al., 2021)

Step 2: Gather RCTs which examine the effectiveness of ECEC-based interventions to improve child diet or physical activity

We gathered all RCTs captured within the following systematic reviews conducted by the team examining: i) ECEC-based healthy eating interventions;(Yoong et al., 2023) ii) ECEC-based physical activity interventions (review of reviews);(Lum et al., 2022) iii) physical activity interventions delivered in centre-based ECEC;(Grady et al., 2025) and iv) healthy eating and physical activity interventions delivered in family day care settings.(Yoong et al., 2020)

Stage 2: Secondary data analysis and synthesis of evidence underpinning practice elements

Step 3: Extract practice elements of RCTs and map to guideline recommendations

Two authors extracted practice elements of healthy eating and physical activity interventions evaluated in RCTs identified in Step 2. Practice elements were defined as specific individual components within an intervention or program that contribute to the impact of an intervention (e.g. providing healthier foods in care; providing opportunity for physical activity). These practice elements were then mapped to recommendations or broad practice themes from the list identified in Step 1 by one author (ML) and checked by a second author (LG, HT or AG), with a third author (SLY) resolving discrepancies. If we were unable to map practice elements to the identified recommendations or broad practice themes, we recorded these intervention practice elements separately as “additional practices”.

Step 4: Apply framework to assess the evidence underpinning practice elements

For each RCT, two authors (ML, LG or HT) extracted the direction of effect for the overall intervention on key dietary and physical activity outcomes, as outlined in a core outcome set for early childhood obesity prevention.(Brown et al., 2022) For diet, this included diet quality and intake of fruit, vegetable, fruit and vegetable (combined), sugar-sweetened beverages and discretionary food (i.e. less healthy foods that are typically high in sugar, salt and saturated fat). Physical activity outcomes included total physical activity, moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, sedentary behaviour and energetic movement (measured by counts and steps).

To assess the evidence underpinning practice elements, we used a vote-counting approach consistent with Synthesis without Meta-Analysis guidelines.(Campbell et al., 2020) We counted the number of studies reporting a positive or negative effect on each child diet and physical activity outcome, based on standardised direction of effects. RCTs were included in vote-counting for a practice element if they measured a relevant outcome, with each outcome assessed individually. RCTs could be included across multiple vote-counting analyses (i.e. if the RCT was mapped to multiple practices and/or reported on multiple outcomes of interest).

Consistent with the approach used previously,(O'Brien et al., 2021) we assessed each practice element (where three or more studies were available) based on the following categorisation framework:

- a)

Likely beneficial: ≥75% of included primary studies demonstrated positive findings (regardless of significance) on the examined outcome

- b)

Possibly beneficial (more evidence needed): 51-74% of included primary studies demonstrated positive findings (regardless of significance) on the examined outcome

- c)

Possibly not beneficial (more evidence needed): the majority (≥50%) of included primary studies demonstrated negative findings (regardless of significance) on the examined outcome

- d)

Not beneficial: all included primary studies demonstrated negative findings (regardless of significance) on the examined outcome

- e)

No conclusions possible due to lack of evidence: If ≤2 primary studies examined this outcome, no conclusions were able to be drawn.

Step 5: Classify practice elements within WHO Standards to provide practice guidance

Lastly, we classified each practice element to one of four global standards outlined within the WHO Standards for Healthy Eating, Physical Activity, Sedentary Behaviour and Sleep in Early Childhood and Care Settings.(WHO, 2021) The standards include: Standard 1 – “build children’s knowledge and skills”; Standard 2 – “provide supportive environments”; Standard 3 – “work with families/primary caregivers about healthy eating and movement behaviours” and Standard 4 – “ensure safety”.

Results

Stage 1: Identifying the existing data

Step 1: Obtain a list of existing guidance to identify specific practice recommendations for ECEC

The list of existing guidance included seven broad practice themes encompassing 36 recommendations for healthy eating and eight broad practice themes encompassing 44 recommendations for physical activity.

Step 2: Gather RCTs which examine the effectiveness of ECEC-based interventions to improve child diet or physical activity

Overall, 78 RCTs described across 80 manuscripts were obtained; 22 RCTs targeted healthy eating, 51 targeted physical activity, and 7 targeted both (see Supplementary file for complete reference list of included RCTs). All included RCTs are briefly summarised in Supplementary Table 1 and have been described in detail in the original review publications.(Grady et al., 2025; Lum et al., 2022; Yoong et al., 2020; Yoong et al., 2023) The majority of RCTs (n=76, 97.4%) were delivered in centre-based ECEC and two (2.6%) were delivered in family day care services. All RCTs were conducted in high- or upper-middle-income countries, with the majority of studies conducted in the United States (n=29, 37.2%) and Australia (n=16, 20.5%). Sample sizes ranged from 1 to 309 services and included between 39 and 4,964 children.

Stage 2: Secondary data analysis and synthesis of evidence underpinning common practice elements

Step 3: Extract practices elements of RCTs and map to guideline recommendations

RCTs provided evidence for 26 healthy eating and 30 physical activity practice elements which could be mapped to guideline recommendations or themes. None of the RCTs mapped to the remaining 11 healthy eating recommendations and 14 physical activity recommendations (Supplementary Table 2 and 3). We also recorded two additional practices: restructuring the scheduling of play opportunities to promote active play and parent involvement in child physical activity.

Step 4: Apply framework to assess the evidence underpinning practice elements

Where a study identified from systematic reviews in Step 2 did not report on the effect of the intervention on any of the outcomes of interest, these studies were excluded from the vote-counting approach (n=9 for healthy eating (Fitzgibbon et al., 2005; Fitzgibbon et al., 2006; Hu et al., 2010; Kipping et al., 2019; Lerner-Geva et al., 2015; Nekitsing et al., 2019; Puder et al., 2011; Reyes-Morales et al., 2016; Zeinstra et al., 2018); n=4 for physical activity (Carroll et al., 2021; Fitzgibbon et al., 2005; Fitzgibbon et al., 2006; Salazar et al., 2014)).

From 29 RCTs reporting on healthy eating, we categorised 16 practice elements as likely beneficial, one as possibly beneficial and one as possibly not beneficial, based on our categorisation framework (Supplementary Table 2). No conclusions could be drawn on the remaining 19 practice elements due to insufficient number of included RCTs that targeted these.

From 58 RCTs reporting on physical activity, we categorised 19 practice elements as likely beneficial, six as possibly beneficial and one as possibly not beneficial (Supplementary Table 3). We could draw no conclusions on the remaining 20 practice elements.

Step 5: Classify practice elements within WHO Standards to provide practice guidance

We classified four healthy eating practices elements within Standard 1; 24 to Standard 2; eight to Standard 3; and one to Standard 4 of the WHO Standards. We classified 16 physical activity practice elements within Standard 1; 16 to Standard 2; seven to Standard 3; and seven to Standard 4 of the WHO Standards. There were some likely beneficial practice elements included across Standards 1, 2 and 3 for both healthy eating and physical activity, and no likely beneficial practice elements for Standard 4 (see Supplementary Tables 2 and 3).

Discussion

This study applied a systematic process to describe the intervention evidence-base underpinning healthy eating and physical activity practice elements in ECEC. The majority of practice elements were categorised overall as likely beneficial, and none were categorised as not beneficial. Two additional likely beneficial physical activity practices (restructuring the scheduling of play opportunities to promote active play; parent involvement in child physical activity) were identified. Future revision of ECEC guidelines should consider evidence from this review to support the retainment of existing recommendations and justify the development of new recommendations supported by evidence. Practice elements mapped across all four WHO standards.

All included interventions were multi-component, as is common in public health research, therefore, the effectiveness of each practice element in isolation was not able to be directly explored. Our mapping process categorised evidence based on the proportion of RCTs that included a particular practice element and reported a positive direction of effect, over all RCTs including that practice element. Therefore, the beneficial practice elements should be interpreted in the context of a multi-component intervention rather than as a single intervention strategy. Study designs, such as factorial-RCTs, are needed to understand the relative benefits of individual practice elements. For example, Zarnowieki and colleagues outline a multiphase optimisation strategy including a factorial-RCT that seeks to identify the benefits of changing food provision, curriculum and supportive mealtime practices in ECEC on child’s vegetable intake, in isolation.(Zarnowiecki et al., 2021) Such research is important to better inform the development of evidence-based guidelines in this setting.

Our mapping to the WHO Standards(WHO, 2021) identified several likely beneficial practice elements aligned to Standards 1, 2 and 3, however most practice elements mapped to Standard 4 did not have sufficient evidence to allow for categorisation. This provides guidance for policy makers, prevention practitioners and ECEC settings looking to prioritise and implement evidence-based practices to promote healthy eating and physical activity. Future guideline iterations should also consider refining recommendations in line with terminology which reflects contemporary frameworks such as more recent Australian-endorsed guidance (e.g., the Early Years Learning Framework v2.0(Australian Government Department of Education, 2022) and the National Quality Standard(Australian Children's Education and Care Quality Authority, 2018)). These frameworks now emphasise “energetic play” (rather than the earlier focus on “structured physical activity”) recognising the importance of spontaneous, child-led movement throughout the day. Healthy eating terminology has also evolved from prescriptive concepts such as “food groups” and “nutrition education” toward more holistic language promoting “food literacy,” “responsive feeding,” and “positive mealtime environments”. Processes to refine recommendations should also be conducted with other relevant stakeholders to ensure alignment with current terminology.(Brouwers et al., 2010)

Limitations

The RCT evidence was gathered from existing reviews, with search strategies conducted between 2019-2022, therefore, an update of these reviews is required to capture the most recent evidence. These findings only consider the impact on child diet and physical activity outcomes. An examination including additional relevant health outcomes (e.g. sedentary behaviour, screen time, cognitive or social and emotional learning outcomes) may provide a more holistic understanding of the impact of practice elements. We used vote-counting approaches to assess evidence underpinning practices elements, where each study was given equal weighting. Therefore, sample sizes, specific effect sizes and study characteristics did not contribute to the result. While additional practices were captured where possible, the mapping process may also have been limited by the recommendations identified in the guidelines, which were published between 1999-2020.(Jackson et al., 2021)

Conclusions

This study describes the evidence-base underpinning common practice elements to promote healthy eating and physical activity in children attending ECEC services. The findings provide insights into likely beneficial practice elements that may warrant inclusion in future guideline updates and provides an important decision-making tool for implementation investment for jurisdictions where ECEC is a key setting for chronic disease prevention efforts.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Deakin University, Hunter New England Local Health District, University of Newcastle and Hunter Medical Research Institute for providing infrastructure support.

Ethics information

Ethics approval and consent to participate are not applicable due to the use of unidentifiable secondary data.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study. All mapping data is provided as part of the submitted manuscript.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Funding sources

This work was supported by the NHMRC Centre for Research Excellence grant (CIA: Wolfenden, CIG Yoong APP1153479). The contents are the responsibility of the authors and do not reflect the views of the NHMRC. AG was supported by a Heart Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship (102518). LW was supported by a NHMRC Leadership Grant (APP1197022). SLY was supported by a Heart Foundation Future Leader Fellowship (106654). Deakin University, Hunter New England Local Health District, University of Newcastle and Hunter Medical Research Institute provided infrastructure and in-kind support.

Authors' contributions

SY, AG and LW conceptualised the paper. SY, ML and LW developed the mapping methodology applied in this manuscript. SY, ML, AG, NP and LW are authors on the reviews included in this study. SY, ML, HT, AG and LG undertook the practice mapping, extraction, and classification of evidence. ML drafted the manuscript, and SY supported the revisions of the manuscript. All authors provided conceptual comments and approved the final version for submission.

Declaration of interest statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| ECEC |

Early Childhood Education and Care |

| RCTs |

Randomised Controlled Trials |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

References

- Afshin A, Sur PJ, Fay KA, et al. (2019) Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet 393(10184): 1958–1972. [CrossRef]

- Australian Children's Education and Care Quality Authority (2018) Guide to the National Quality Framework. Sydney, Australia: ACECQA.

- Australian Government Department of Education (2022) Belonging, Being and Becoming: The Early Years Learning Framework for Australia (V2.0). Australian Government Department of Education for the Ministerial Council.

- Brouwers M, Kho M, Browman G, et al. (2010) AGREE II: Advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in healthcare.: Can Med Assoc J, 182:E839–842.

- Brown V, Moodie M, Sultana M, et al. (2022) Core outcome set for early intervention trials to prevent obesity in childhood (COS-EPOCH): Agreement on “what” to measure. International Journal of Obesity 46(10): 1867–1874. [CrossRef]

- Campbell M, McKenzie JE, Sowden A, et al. (2020) Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) in systematic reviews: reporting guideline. BMJ 368: l6890. [CrossRef]

- Carroll AV, Spring KE and Wadsworth DD (2021) The effect of a teacher-guided and -led indoor preschool physical activity intervention: A feasibility study. Early Childhood Education Journal. No Pagination Specified. [CrossRef]

- Fitzgibbon ML, Stolley MR, Schiffer L, et al. (2005) Two-year follow-up results for Hip-Hop to Health Jr.: a randomized controlled trial for overweight prevention in preschool minority children. The Journal of pediatrics 146(5): 618–625. [CrossRef]

- Fitzgibbon ML, Stolley MR, Schiffer L, et al. (2006) Hip-hop to health Jr. for Latino preschool children. Obesity 14(9): 1616–1625. [CrossRef]

- García-Hermoso A, Izquierdo M and Ramírez-Vélez R (2022) Tracking of physical fitness levels from childhood and adolescence to adulthood: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Transl Pediatr 11(4): 474–486. [CrossRef]

- Garland AF, Bickman L and Chorpita BF (2010) Change What? Identifying Quality Improvement Targets by Investigating Usual Mental Health Care. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research 37(1): 15–26. [CrossRef]

- Grady A, Lorch R, Giles L, et al. (2025) The impact of early childhood education and care-based interventions on child physical activity, anthropometrics, fundamental movement skills, cognitive functioning, and social-emotional wellbeing: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev 26(2): e13852. [CrossRef]

- Hu C, Ye D, Li Y, et al. (2010) Evaluation of a kindergarten-based nutrition education intervention for pre-school children in China. Public Health Nutrition 13(2): 253–260. [CrossRef]

- Jackson JK, Jones J, Nguyen H, et al. (2021) Obesity Prevention within the Early Childhood Education and Care Setting: A Systematic Review of Dietary Behavior and Physical Activity Policies and Guidelines in High Income Countries. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(2). [CrossRef]

- Kipping R, Langford R, Brockman R, et al. (2019) Child-care self-assessment to improve physical activity, oral health and nutrition for 2-to 4-year-olds: a feasibility cluster RCT. Public Health Research 7(13): 1–164. [CrossRef]

- Lerner-Geva L, Bar-Zvi E, Levitan G, et al. (2015) An intervention for improving the lifestyle habits of kindergarten children in Israel: a cluster-randomised controlled trial investigation. Public Health Nutrition 18(9): 1537–1544. [CrossRef]

- Lum M, Wolfenden L, Jones J, et al. (2022) Interventions to Improve Child Physical Activity in the Early Childhood Education and Care Setting: An Umbrella Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19(4): 1963. [CrossRef]

- McLeod BD, Sutherland KS, Martinez RG, et al. (2017) Identifying Common Practice Elements to Improve Social, Emotional, and Behavioral Outcomes of Young Children in Early Childhood Classrooms. Prev Sci 18(2): 204–213. [CrossRef]

- Nekitsing C, Blundell-Birtill P, Cockroft JE, et al. (2019) Taste exposure increases intake and nutrition education increases willingness to try an unfamiliar vegetable in preschool children: a cluster randomized trial. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 119(12): 2004–2013. [CrossRef]

- NHMRC (2013) Infant feeding guidelines: summary. Reportno. Report Number, Date. Place Published: Institution.

- O'Brien KM, Barnes C, Yoong S, et al. (2021) School-Based Nutrition Interventions in Children Aged 6 to 18 Years: An Umbrella Review of Systematic Reviews. Nutrients 13(11). [CrossRef]

- OECD (2023) PF3.2: Enrolment in childcare and pre-school. Available at: www.oecd.org/els/soc/PF3_2_Enrolment_childcare_preschool.pdf (accessed June).

- Puder JJ, Marques-Vidal P, Schindler C, et al. (2011) Effect of multidimensional lifestyle intervention on fitness and adiposity in predominantly migrant preschool children (Ballabeina): cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 343. [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Morales H, González-Unzaga MA, Jiménez-Aguilar A, et al. (2016) Effect of an intervention based on child-care centers to reduce risk behaviors for obesity in preschool children. Boletin Medico del Hospital Infantil de Mexico 73(2): 75–83. [CrossRef]

- Salazar G, Vasquez F, Concha F, et al. (2014) Pilot nutrition and physical activity intervention for preschool children attending daycare centres (JUNJI): primary and secondary outcomes. Nutr Hosp 29(5): 1004–1012.

- Tremblay MS, Chaput J-P, Adamo KB, et al. (2017) Canadian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for the Early Years (0–4 years): An Integration of Physical Activity, Sedentary Behaviour, and Sleep. BMC Public Health 17(5): 874. [CrossRef]

- WHO (2003) Global strategy for infant and young child feeding. Reportno. Report Number, Date. Place Published: Institution.

- WHO (2021) Standards for healthy eating, physical activity, sedentary behaviour and sleep in early childhood education and care settings: a toolkit. Reportno. Report Number, Date. Place Published: Institution.

- WHO (2023) Noncommunicable diseases. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases (accessed 16 September).

- Xu YY, Xie J, Yin H, et al. (2022) The Global Burden of Disease attributable to low physical activity and its trends from 1990 to 2019: An analysis of the Global Burden of Disease study. Front Public Health 10: 1018866. [CrossRef]

- Yoong SL, Lum M, Jones J, et al. (2020) A systematic review of interventions to improve the dietary intake, physical activity and weight status of children attending family day care services. Public Health Nutr 23(12): 2211–2220. [CrossRef]

- Yoong SL, Lum M, Wolfenden L, et al. (2023) Healthy eating interventions delivered in early childhood education and care settings for improving the diet of children aged six months to six years. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 6(6): Cd013862. [CrossRef]

- Zarnowiecki D, Kashef S, Poelman AA, et al. (2021) Application of the multiphase optimisation strategy to develop, optimise and evaluate the effectiveness of a multicomponent initiative package to increase 2-to-5-year-old children’s vegetable intake in long day care centres: a study protocol. BMJ Open 11(12): e047618. [CrossRef]

- Zeinstra GG, Vrijhof M and Kremer S (2018) Is repeated exposure the holy grail for increasing children's vegetable intake? Lessons learned from a Dutch childcare intervention using various vegetable preparations. Appetite 121: 316–325. [CrossRef]

- Zheng M, Lamb KE, Grimes C, et al. (2018) Rapid weight gain during infancy and subsequent adiposity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of evidence. Obesity Reviews 19(3): 321–332. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).