Submitted:

10 November 2025

Posted:

12 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. Bone Fracture Detection

2.2. Elbow Fracture Challenges

2.3. Current Approaches

2.4. Application in Mobile and Edge Environments

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Preparation and Model Training

3.2. Model Export and Deployment

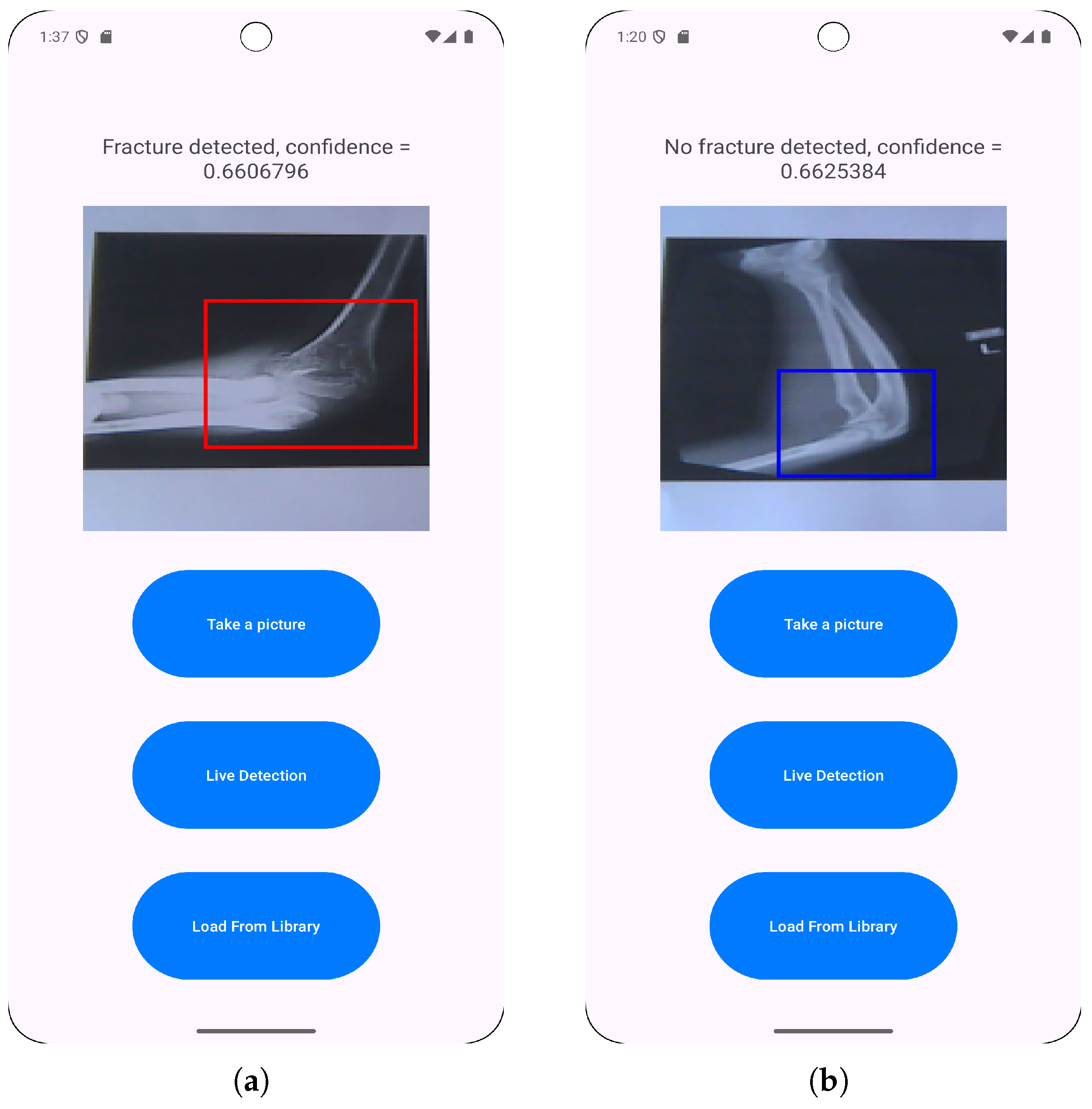

3.3. Application Features Implementation

- Loading images from a photo library to enable the classification of pre-existing saved radiographs.

- Direct camera capturing to allow for immediate fracture classification.

- Live fracture detection that provides real-time feedback during positioning and imaging.

3.4. Evaluation and Testing

4. Results

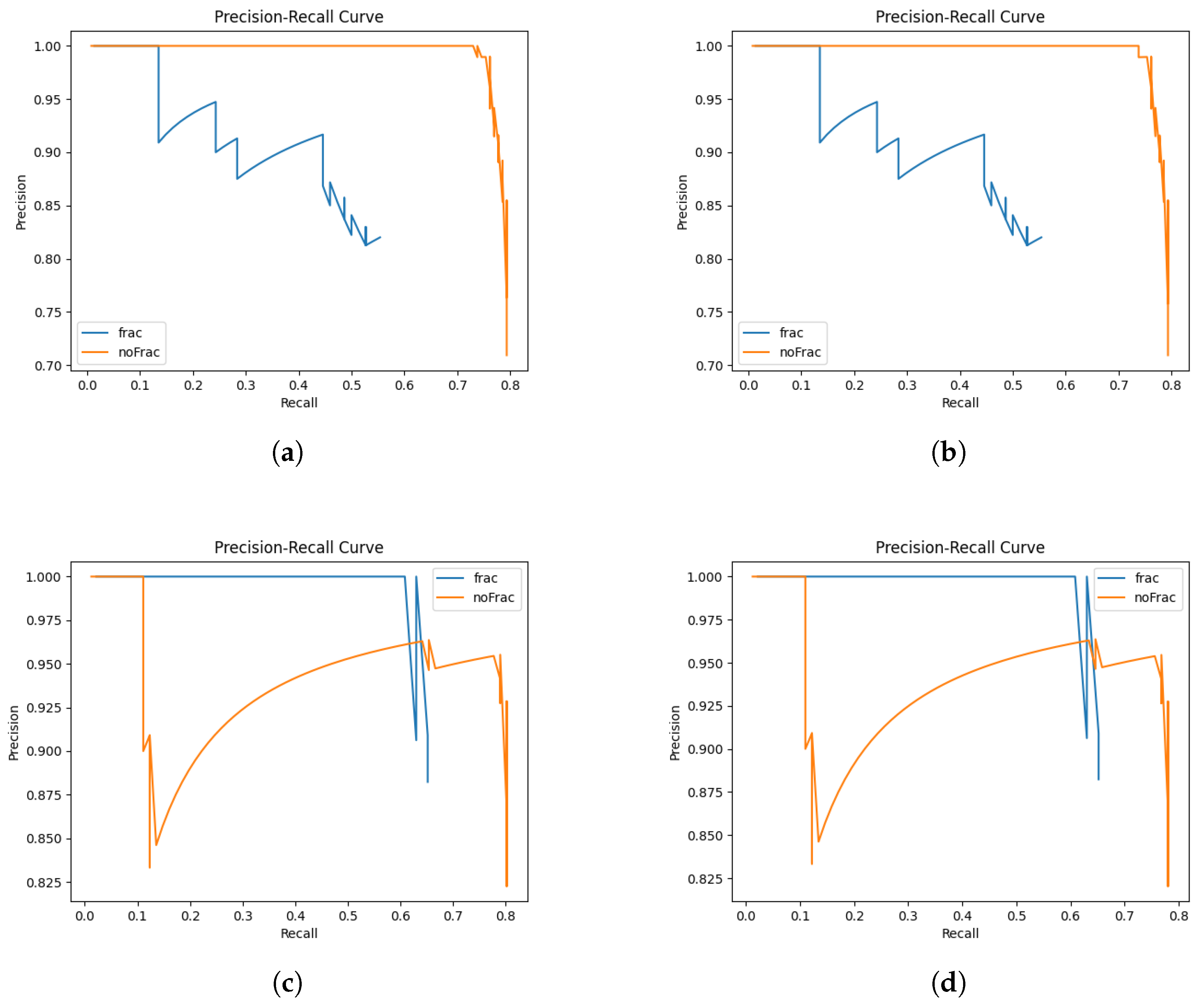

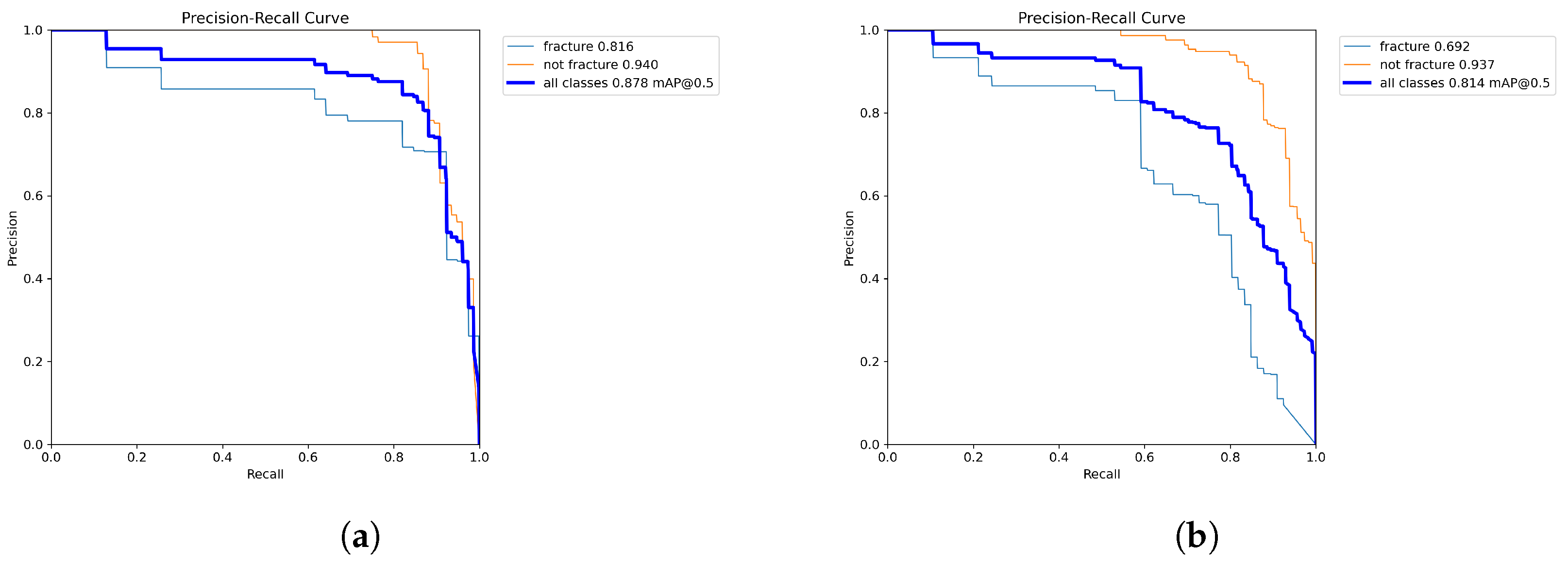

4.1. Model Training Results

| Hyperparameter | Model 1 | Model 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Learning Rate (lr0) | 0.0810 | 0.0492 |

| Final Learning Rate (lrf) | 0.8947 | 0.3719 |

| Batch Size | 32 | 32 |

| Box Loss Weight | 0.1610 | 0.1043 |

| Classification loss weight | 0.9062 | 0.5831 |

| Performance Metric | Model 1 | Model 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Average precision | 0.821 | 0.85 |

| Average recall | 0.89 | 0.722 |

| Average mAP50 | 0.878 | 0.814 |

| Average mAP50-95 | 0.408 | 0.375 |

| Average F1 Score | 0.854 | 0.781 |

4.2. In-App Test Set Results

4.2.1. Independent Testing

| Performance Metric | Model 1 FP32 & FP16 | Model 2 FP32 & FP16 |

|---|---|---|

| Average F1 Score | 0.697 | 0.889 |

| Average Confidence | 0.682 | 0.625 |

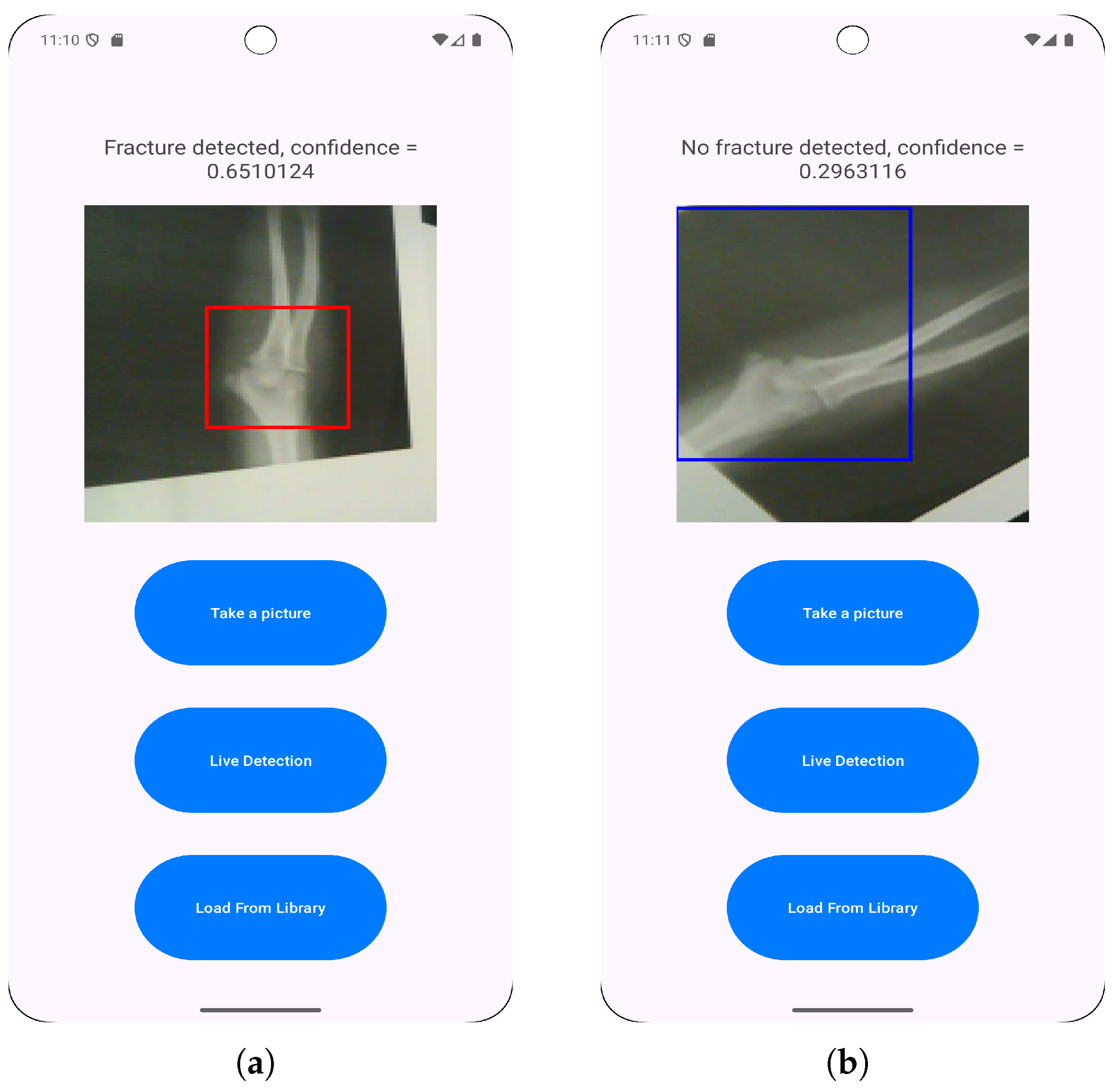

| Average Accuracy | 0.7 | 0.9 |

4.2.2. Performance Testing

- User launches the app, takes a photo with the camera and chooses it for model inference.

- User launches the app, selects a photo from the library and chooses it for model inference.

- User launches the app and starts live detection for model inference.

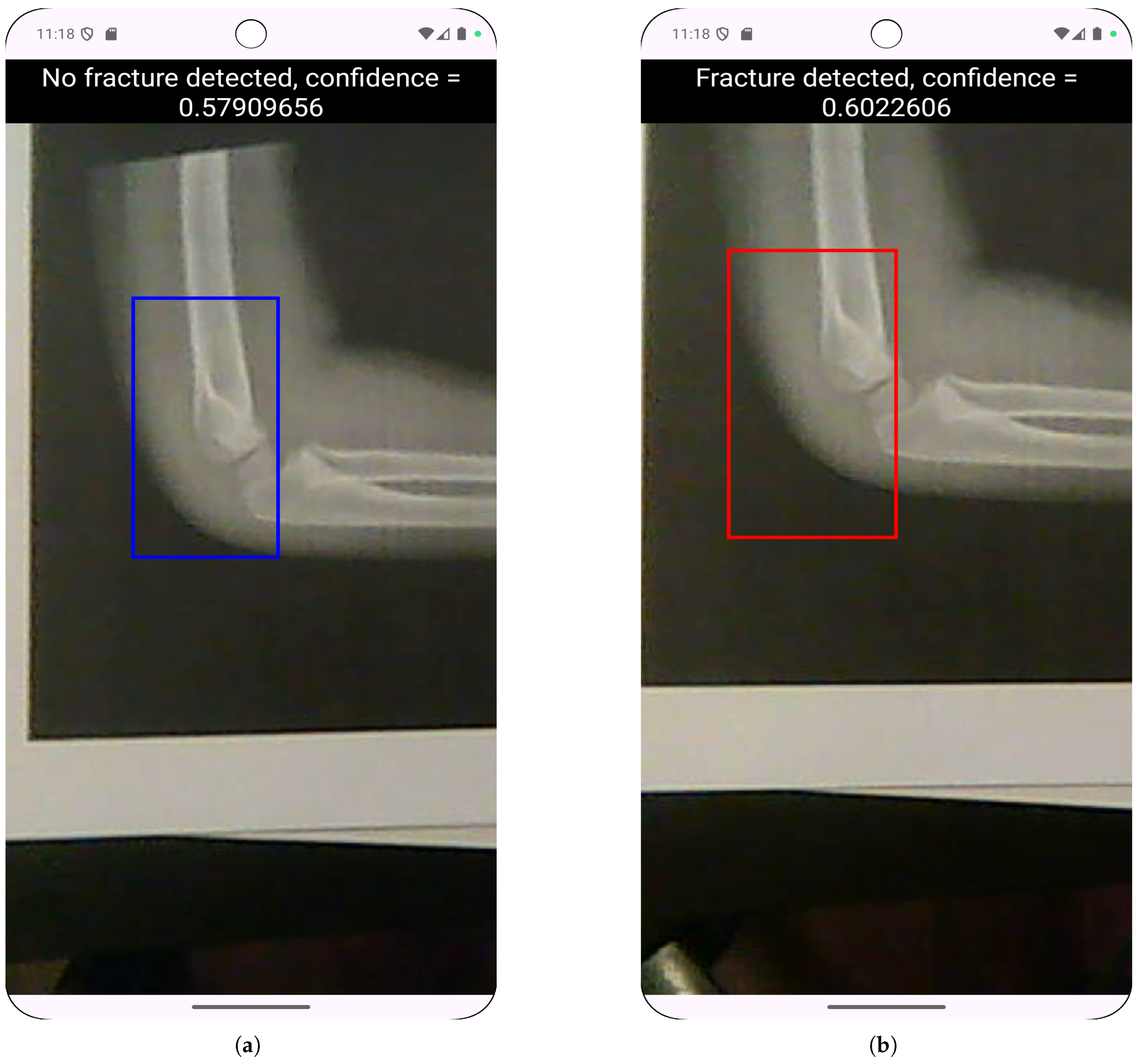

4.3. Real Camera Testing

| Model | Lighting | Avg. Precision | Avg. Recall | Avg. F1 Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 80/10/10 FP32 | Daylight | 0.669 | 0.533 | 0.549 |

| 80/10/10 FP32 | Artificial | 0.563 | 0.5 | 0.516 |

| 80/10/10 FP16 | Daylight | 0.653 | 0.625 | 0.603 |

| 80/10/10 FP16 | Artificial | 0.334 | 0.3 | 0.31 |

4.4. Live Detection Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Performance on Digital Radiographs and Clinical Relevance

5.2. Generalization Challenges and Domain Shift

5.3. Improoving the Performance Degradation in Camera-Based Inference

5.4. Computational Efficiency

6. Conclusions

- developing diverse datasets explicitly incorporating camera-acquired images under varied conditions;

- implementing domain adaptation techniques like CycleGAN to bridge digital-to-photograph gaps;

- creating pediatric-specific models addressing anatomical differences;

- exploring hybrid approaches combining PACS integration for clinical settings with camera functionality for field use; and

- conducting prospective clinical trials comparing AI-assisted diagnosis with standard practice.

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| YOLO | You Only Look Once |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| NMS | Non-Maximum Suppression |

| IoU | Intersection over Union |

| TFLite | TensorFlow Lite |

| FP | Floating Point |

| PR | Precision-Recall |

| mAP | mean Average Precision |

| PACS | Picture Archiving and Communication System |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Camera Detection Results - Daylight (Model 1 FP32) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Performance Metric | Straight Down | 45 paper shift | 45 side angle | average |

| Fracture detection precision | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.533 |

| Fracture detection recall | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.667 |

| Fracture detection F1 score | 0.6 | 0.545 | 0.615 | 0.587 |

| Non-Fracture detection precision | 0.75 | 0.667 | 1.0 | 0.806 |

| Non-Fracture detection recall | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.4 |

| Non-Fracture detection F1 score | 0.667 | 0.533 | 0.333 | 0.51 |

| Average Precision | 0.675 | 0.583 | 0.75 | 0.669 |

| Average Recall | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.533 |

| Average F1 Score | 0.634 | 0.539 | 0.474 | 0.549 |

| Camera Detection Results - Artificial Light (Model 1 FP32) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Performance Metric | Straight Down | 45 paper shift | 45 side angle | average |

| Fracture detection precision | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.429 | 0.51 |

| Fracture detection recall | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.533 |

| Fracture detection F1 score | 0.6 | 0.444 | 0.5 | 0.515 |

| Non-Fracture detection precision | 0.6 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 0.617 |

| Non-Fracture detection recall | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.467 |

| Non-Fracture detection F1 score | 0.6 | 0.667 | 0.286 | 0.518 |

| Average Precision | 0.6 | 0.625 | 0.465 | 0.563 |

| Average Recall | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0. 5 |

| Average F1 Score | 0.6 | 0.555 | 0. 393 | 0.516 |

| Camera Detection Results - Daylight (Model 1 FP16) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Performance Metric | Straight Down | 45 paper shift | 45 side angle | average |

| Fracture detection precision | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 0.667 |

| Fracture detection recall | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.467 |

| Fracture detection F1 score | 0.667 | 0.667 | 0.286 | 0.54 |

| Non-Fracture detection precision | 0.667 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 0.639 |

| Non-Fracture detection recall | 0.8 | 0.75 | 0.8 | 0.783 |

| Non-Fracture detection F1 score | 0.632 | 0.75 | 0.615 | 0.666 |

| Average Precision | 0.708 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 0.653 |

| Average Recall | 0.7 | 0.675 | 0.5 | 0.625 |

| Average F1 Score | 0.649 | 0.708 | 0. 451 | 0.603 |

| Camera Detection Results - Artificial Light (Model 1 FP16) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Performance Metric | Straight Down | 45 paper shift | 45 side angle | average |

| Fracture detection precision | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.333 | 0.361 |

| Fracture detection recall | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| Fracture detection F1 score | 0.545 | 0.222 | 0.364 | 0.377 |

| Non-Fracture detection precision | 0.333 | 0.333 | 0.25 | 0.306 |

| Non-Fracture detection recall | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Non-Fracture detection F1 score | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.222 | 0.241 |

| Average Precision | 0.417 | 0.292 | 0.292 | 0.334 |

| Average Recall | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Average F1 Score | 0.398 | 0.236 | 0.293 | 0.31 |

| Live Camera Detection Results - Daylight (Model 1 FP32) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Performance Metric | Straight Down | 45 paper shift | 45 side angle | average |

| Fracture detection precision | 0.333 | 0.625 | 0.333 | 0.431 |

| Fracture detection recall | 0.4 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 0.6 |

| Fracture detection F1 score | 0.364 | 0.769 | 0.364 | 0.499 |

| Non-Fracture detection precision | 0.25 | 1.0 | 0.333 | 0.528 |

| Non-Fracture detection recall | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.267 |

| Non-Fracture detection F1 score | 0.222 | 0.571 | 0.25 | 0.348 |

| Average Precision | 0.292 | 0.813 | 0.333 | 0.479 |

| Average Recall | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.433 |

| Average F1 Score | 0.293 | 0.67 | 0.307 | 0.423 |

| Live Camera Detection Results - Daylight (Model 1 FP16) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Performance Metric | Straight Down | 45 paper shift | 45 side angle | average |

| Fracture detection precision | 0.25 | 0.625 | 0.333 | 0.403 |

| Fracture detection recall | 0.2 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 0.533 |

| Fracture detection F1 score | 0.222 | 0.769 | 0.364 | 0.452 |

| Non-Fracture detection precision | 0.2 | 1.0 | 0.333 | 0.511 |

| Non-Fracture detection recall | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.267 |

| Non-Fracture detection F1 score | 0.2 | 0.571 | 0.25 | 0.340 |

| Average Precision | 0.225 | 0.813 | 0.333 | 0.457 |

| Average Recall | 0.2 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.4 |

| Average F1 Score | 0.211 | 0.67 | 0.307 | 0.396 |

| Live Camera Detection Results - Artificial Light (Model 1 FP32) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Performance Metric | Straight Down | 45 paper shift | 45 side angle | average |

| Fracture detection precision | 0.2 | 0.571 | 0.333 | 0.368 |

| Fracture detection recall | 0.2 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.467 |

| Fracture detection F1 score | 0.2 | 0.667 | 0.364 | 0.41 |

| Non-Fracture detection precision | 0.0 | 0.667 | 0.0 | 0.222 |

| Non-Fracture detection recall | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.133 |

| Non-Fracture detection F1 score | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.167 |

| Average Precision | 0.1 | 0.619 | 0.167 | 0.295 |

| Average Recall | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.3 |

| Average F1 Score | 0.1 | 0.583 | 0.182 | 0.288 |

| Live Camera Detection Results - Artificial Light (Model 1 FP16) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Performance Metric | Straight Down | 45 paper shift | 45 side angle | average |

| Fracture detection precision | 0.333 | 0.667 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Fracture detection recall | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.567 |

| Fracture detection F1 score | 0.4 | 0.727 | 0.444 | 0.524 |

| Non-Fracture detection precision | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Non-Fracture detection recall | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.267 |

| Non-Fracture detection F1 score | 0.0 | 0.571 | 0.444 | 0.338 |

| Average Precision | 0.167 | 0.833 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Average Recall | 0.25 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.417 |

| Average F1 Score | 0.2 | 0.649 | 0.444 | 0.431 |

| Model Performance Results | ||

|---|---|---|

| Performance Metric | Model 1 | Model 2 |

| Fracture detection precision | 0.701 | 0.826 |

| Fracture detection recall | 0.923 | 0.591 |

| Fracture detection F1 score | 0.797 | 0.689 |

| Fracture detection mAP50 | 0.816 | 0.692 |

| Fracture detection mAP50-95 | 0.348 | 0.266 |

| Non-Fracture detection precision | 0.942 | 0.874 |

| Non-Fracture detection recall | 0.857 | 0.852 |

| Non-Fracture detection F1 score | 0.897 | 0.862 |

| Non-Fracture detection mAP50 | 0.94 | 0.937 |

| Non-Fracture detection mAP50-95 | 0.467 | 0.483 |

| Average precision | 0.821 | 0.85 |

| Average recall | 0.89 | 0.722 |

| Average mAP50 | 0.878 | 0.814 |

| Average mAP50-95 | 0.408 | 0.375 |

| Average F1 Score | 0.854 | 0.781 |

| Model Performance Results | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Performance Metric | model 1 - FP32 | model 1 - FP16 | model 2 - FP32 | model 2 - FP16 |

| Fracture detection precision | 0.846 | 0.846 | 0.893 | 0.893 |

| Fracture detection recall | 0.971 | 0.971 | 0.877 | 0.877 |

| Fracture detection F1 score | 0.904 | 0.904 | 0.885 | 0.885 |

| Fracture average mAP@50 | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.51 | 0.51 |

| Fracture average mAP@50-95 | 0.310 | 0.312 | 0.223 | 0.223 |

| Non-Fracture detection precision | 0.985 | 0.985 | 0.936 | 0.936 |

| Non-Fracture detection recall | 0.917 | 0.917 | 0.945 | 0.945 |

| Non-Fracture detection F1 score | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.941 | 0.941 |

| Non-Fracture average mAP@50 | 0.736 | 0.757 | 0.79 | 0.79 |

| Non-Fracture average mAP@50-95 | 0.373 | 0.374 | 0.386 | 0.386 |

| Average F1 Score | 0.927 | 0.927 | 0.913 | 0.913 |

| Average Accuracy | 0.934 | 0.934 | 0.922 | 0.922 |

| Average Bounding Box IoU | 0.699 | 0.699 | 0.683 | 0.683 |

| Average mAP@50 | 0.693 | 0.704 | 0.65 | 0.65 |

| Average mAP@50-95 | 0.342 | 0.343 | 0.305 | 0.305 |

| Average Confidence | 0.698 | 0.698 | 0.676 | 0.676 |

| Model Performance Results - Independent Test Set | ||

|---|---|---|

| Performance Metric | Model 1 FP32 & FP16 | Model 2 FP32 & FP16 |

| Fracture detection precision | 0.667 | 1.0 |

| Fracture detection recall | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| Fracture detection F1 score | 0.727 | 0.889 |

| Non-Fracture detection precision | 0.75 | 0.833 |

| Non-Fracture detection recall | 0.6 | 1.0 |

| Non-Fracture detection F1 score | 0.667 | 0.91 |

| Average F1 Score | 0.697 | 0.889 |

| Average Confidence | 0.682 | 0.625 |

| Average Accuracy | 0.7 | 0.9 |

References

- Kuo, R.Y.L.; Harrison, C.; Curran, T.; Jones, B.; Freethy, A.; Cussons, D.; Stewart, M.; Collins, G.; Furniss, D. Artificial Intelligence in Fracture Detection: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Radiology, 2022; 211785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutbi, M. Artificial Intelligence-Based Applications for Bone Fracture Detection Using Medical Images: A Systematic Review. Diagnostics 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nurifin, S. Performance of artificial intelligence in detecting bone fractures in radiographic results: A systematic literature review. Malahayati International Journal of Nursing and Health Science 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.K. Evolution of Artificial Intelligence in Bone Fracture Detection. International Journal of Reliable and Quality E-Healthcare, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guermazi, A.; Tannoury, C.; Kompel, A.; Murakami, A.M.; Ducarouge, A.; Gillibert, A.; Li, X.; Tournier, A.; Lahoud, Y.; Jarraya, M.; et al. Improving Radiographic Fracture Recognition Performance and Efficiency Using Artificial Intelligence. Radiology, 2021; 210937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousson, V.; Attané, G.; Benoist, N.; Perronne, L.; Diallo, A.; Hadid-Beurrier, L.; Martin, E.; Hamzi, L.; Duval, A.D.; Revue, E.; et al. Artificial Intelligence for Detecting Acute Fractures in Patients Admitted to an Emergency Department: Real-Life Performance of Three Commercial Algorithms. Academic radiology 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canoni-Meynet, L.; Verdot, P.; Danner, A.; Calame, P.; Aubry, S. Added value of an artificial intelligence solution for fracture detection in the radiologist’s daily trauma emergencies workflow. Diagnostic and interventional imaging 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dann, L.; Edwards, S.; Hall, D.; Davis, T.; Roland, D.; Barrett, M. Black and white: how good are clinicians at diagnosing elbow injuries from paediatric elbow radiographs alone? Emerg Med J 2024, 41, 662–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Hu, W.; Wu, H.; Chen, Z.; Chen, J.; Lai, Q.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y. Detection of hidden pediatric elbow fractures in X-ray images based on deep learning. Journal of Radiation Research and Applied Sciences 2024, 17, 100893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boissin, C.; Blom, L.; Wallis, L.; Laflamme, L. Image-based teleconsultation using smartphones or tablets: qualitative assessment of medical experts. Emergency Medicine Journal 2017, 34, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M, P.P.; M, S.H.; N, R.; S, S.B. Edge AI-based Bone Fracture Detection using TFlite. International Journal of Innovative Research in Advanced Engineering 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajpurkar, P.; Lungren, M.P. The Current and Future State of AI Interpretation of Medical Images. New England Journal of Medicine 2023, 388, 1981–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto-Coelho, L. How Artificial Intelligence Is Shaping Medical Imaging Technology: A Survey of Innovations and Applications. Bioengineering 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayan, J.; Reddy, N.; Kan, J.; Zhang, W.; Annapragada, A. Binomial Classification of Pediatric Elbow Fractures Using a Deep Learning Multiview Approach Emulating Radiologist Decision Making. Radiology: Artificial Intelligence 2019, 1, e180015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binh, L.N.; Nhu, N.T.; Nhi, P.T.U.; Son, D.L.H.; Bach, N.; Huy, H.Q.; Le, N.Q.K.; Kang, J.H. Impact of deep learning on pediatric elbow fracture detection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Trauma and Emergency Surgery 2025, 51, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyeniyi, J.; Oluwaseyi, P. Emerging Trends in AI-Powered Medical Imaging: Enhancing Diagnostic Accuracy and Treatment Decisions. International Journal of Enhanced Research In Science Technology & Engineering 2024, 13, 2319–7463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagar, A.; Kekatpure, A.L.; Velagala, V.R.; Kekatpure, A. A Review on the Use of Artificial Intelligence in Fracture Detection. Cureus 2024, 16, e58364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacques, T.; Cardot, N.; Ventre, J.; Demondion, X.; Cotten, A. Commercially-available AI algorithm improves radiologists’ sensitivity for wrist and hand fracture detection on X-ray, compared to a CT-based ground truth. European Radiology 2024, 34, 2885–2894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagar, A.; Kekatpure, A.L.; Velagala, V.R.; Kekatpure, A. A review on the use of artificial intelligence in fracture detection. Cureus 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dupuis, M.; Delbos, L.; Rouquette, A.; Adamsbaum, C.; Veil, R. External validation of an artificial intelligence solution for the detection of elbow fractures and joint effusions in children. Diagnostic and Interventional Imaging 2024, 105, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ROZWAG, C.; VALENTINI, F.; COTTEN, A.; DEMONDION, X.; PREUX, P.; JACQUES, T. Elbow trauma in children: development and evaluation of radiological artificial intelligence models. Research in Diagnostic and Interventional Imaging 2023, 6, 100029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huhtanen, J.; Nyman, M.; Doncenco, D.; et al. Deep learning accurately classifies elbow joint effusion in adult and pediatric radiographs. Scientific Reports 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erzen, E.M.; BÜtÜn, E.; Al-Antari, M.A.; Saleh, R.A.A.; Addo, D. Artificial Intelligence Computer-Aided Diagnosis to automatically predict the Pediatric Wrist Trauma using Medical X-ray Images. In Proceedings of the 2023 7th International Symposium on Innovative Approaches in Smart Technologies (ISAS); 2023; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdi, A. Lightweight G-YOLOv11: Advancing Efficient Fracture Detection in Pediatric Wrist X-rays, [arXiv:eess.IV/2501.00647]. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Altmann-Schneider, I.; Kellenberger, C.J.; Pistorius, S.M.; Saladin, C.; Schäfer, D.; Arslan, N.; Fischer, H.L.; Seiler, M. Artificial intelligence-based detection of paediatric appendicular skeletal fractures: performance and limitations for common fracture types and locations. Pediatric Radiology 2024, 54, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zech, J.R.; Ezuma, C.O.; Patel, S.; Edwards, C.R.; Posner, R.; Hannon, E.; Williams, F.; Lala, S.V.; Ahmad, Z.Y.; Moy, M.P.; et al. Artificial intelligence improves resident detection of pediatric and young adult upper extremity fractures. Skeletal Radiology 2024, 53, 2643–2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanapure, A.; Kashyap, H.; Bidargaddi, A.; Habib, S.; Anand, A.; M, M.S. Bone Fracture Detection with X-Ray images using MobileNet V3 Architecture. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 9th International Conference for Convergence in Technology (I2CT); 2024; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, D.P.; Sharma, A.; Athithan, S.; Bhola, A.; Sharma, B.; Dhaou, I.B. Hybrid SFNet Model for Bone Fracture Detection and Classification Using ML/DL. Sensors 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varun, V.; Natarajan, S.K.; M, A.; P, N.; A, M.C.; Moorthi Hosahalli, N. Efficient CNN-Based Bone Fracture Detection in X-Ray Radiographs with MobileNetV2. In Proceedings of the 2024 2nd International Conference on Recent Advances in Information Technology for Sustainable Development (ICRAIS); 2024; pp. 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handoko, A.B.; Putra, V.C.; Setyawan, I.; Utomo, D.; Lee, J.; Timotius, I.K. Evaluation of YOLO-X and MobileNetV2 as Face Mask Detection Algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Industrial Electronics and Applications Conference (IEACon); 2022; pp. 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Values |

|---|---|

| Initial Learning Rate (lr0) | [0.00001 - 0.1] |

| Final Learning Rate (lrf) | [0.01 - 1.0] |

| Batch Size | 16, 32 and 64 |

| Box Loss Weight | [0.02 - 0.2] |

| Classification loss weight | [0.2 - 4.0] |

| Performance Metric | model 1 - FP32 | model 1 - FP16 | model 2 - FP32 | model 2 - FP16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average F1 Score | 0.927 | 0.927 | 0.913 | 0.913 |

| Average Accuracy | 0.934 | 0.934 | 0.922 | 0.922 |

| Average Bounding Box IoU | 0.699 | 0.699 | 0.683 | 0.683 |

| Average mAP@50 | 0.693 | 0.704 | 0.65 | 0.65 |

| Average mAP@50-95 | 0.342 | 0.343 | 0.305 | 0.305 |

| Average Confidence | 0.698 | 0.698 | 0.676 | 0.676 |

| Device | Average RAM Usage (GB) | Average CPU Usage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Pixel 3 | 0.173 | 3.492 |

| Pixel 8 Pro | 0.168 | 3.621 |

| Device | Average RAM Usage (GB) | Average CPU Usage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Pixel 3 | 0.253 | 23.55 |

| Pixel 8 Pro | 0.29 | 24.931 |

| Model | Lighting | Average Precision | Average Recall | Average F1 Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 80/10/10 FP32 | Daylight | 0.479 | 0.433 | 0.423 |

| 80/10/10 FP32 | Artificial | 0.457 | 0.4 | 0.396 |

| 80/10/10 FP16 | Daylight | 0.295 | 0.3 | 0.288 |

| 80/10/10 FP16 | Artificial | 0.5 | 0.417 | 0.431 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).