1. Introduction

The growing demand for autonomous monitoring in industrial systems, such as aerospace structures [

1], railway systems [

2], and civil infrastructure [

3], has intensified interest in vibration energy harvesting (VEH) as a sustainable power source for wireless sensor networks (WSNs). By converting ambient mechanical vibrations into electricity, VEH systems eliminate the need for frequent battery replacement and enable long-term, maintenance-free operation in hard-to-access environments. Among various transduction mechanisms, piezoelectric and electromagnetic approaches remain the most promising for practical deployment due to their compactness, scalability, and compatibility with typical industrial vibration frequencies.

Piezoelectric devices can generate high voltages and are structurally compact [

4]; however, they suffer from high damping [

5] and material fatigue under long-term cyclic loading [

6] . Electromagnetic (EM) harvesters, in contrast, offer robust mechanical performance and higher efficiency at low frequencies typical of large-scale machinery [

7]. The main limitation of conventional, linear VEH systems is their narrow operational bandwidth, which restricts efficiency under variable excitation. To overcome this, researchers have explored nonlinear [

8] and tunable [

9] configurations that broaden the response spectrum and enhance adaptability.

While hybrid [

10,

11,

12,

13] and tristable [

14,

15] configurations have been proposed, they remain valuable primarily from a theoretical perspective for exploring complex nonlinear dynamics [

16]. However, their increased structural and control complexity often outweighs the potential performance gains in practical implementations. Similarly, chaotic designs, once considered attractive for energy amplification, have proven unreliable and unpredictable for industrial deployment [

17,

18,

19].

Nonlinear electromagnetic energy harvesters with adjustable magnetic stiffness [

20] have shown particular promise. By varying the spacing between repelling permanent magnets, the restoring force can be tuned to change the harvester’s effective stiffness and to achieve either monostable or bistable behavior, enabling the system to adapt to changing vibration conditions. Bistable designs, in particular, can reach high-amplitude “high-orbit” oscillations that significantly increase power output [

21]. However, this beneficial regime coexists with low-energy and chaotic attractors, making the nonlinear energy harvesting system response highly sensitive to parameter variations.

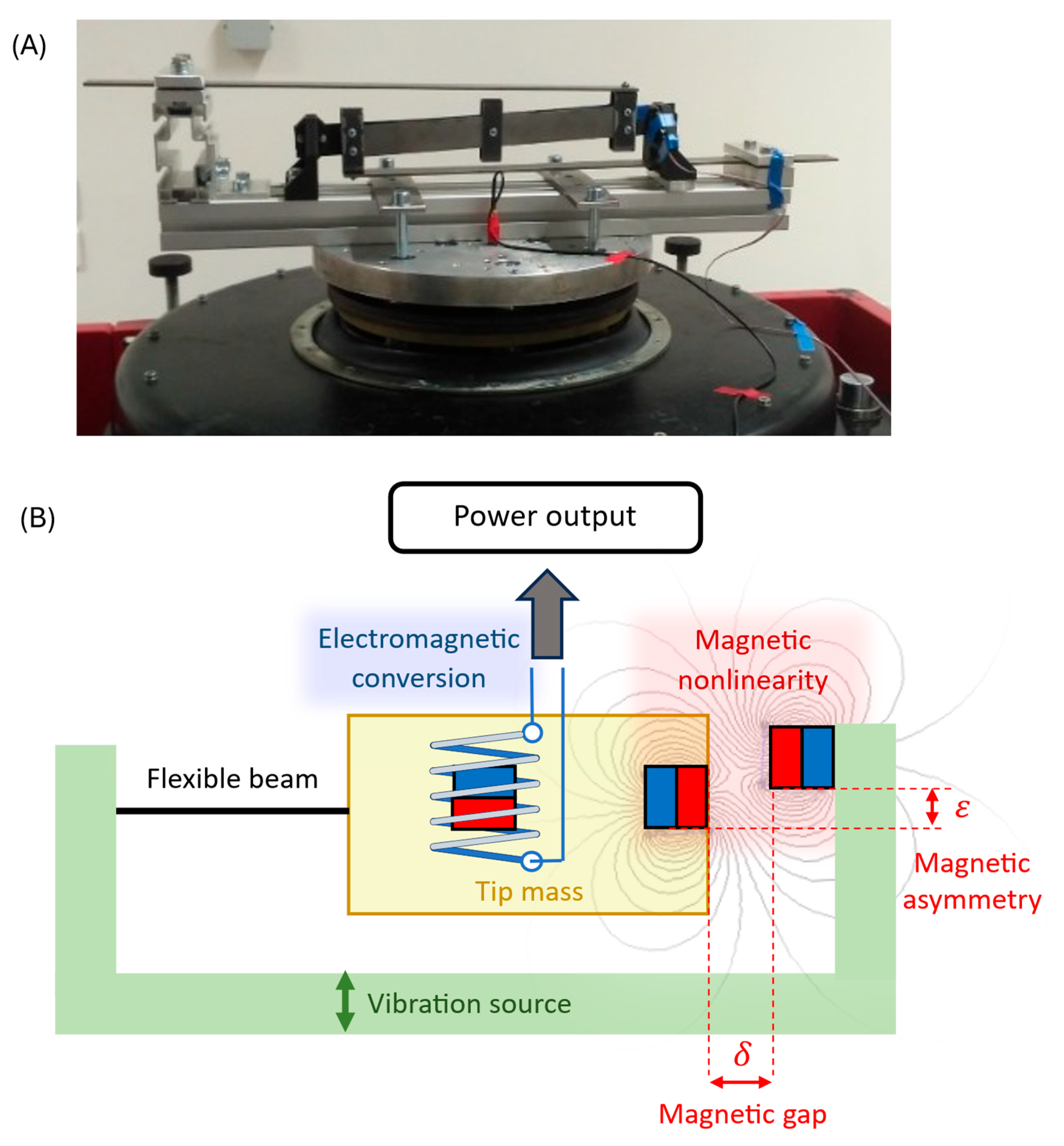

The primary experimental results of the linear laboratory sample [

22] and industrial prototype [

23] (see

Figure 1(A)) have been published, and such railway WSN applications expect mass deployment of harvesters. Both studies addressed trackside kinetic electromagnetic energy harvesters designed for powering wireless sensor nodes, demonstrating their feasibility in railway infrastructure operation based on WSNs. Although these systems were essentially linear, the concept presented in [

22] offers a straightforward path toward nonlinear and tunable behavior by the addition of magnetic elements. This opens a new research question regarding the transition from linear laboratory devices to nonlinear, universally adaptable harvesters suitable for robust industrial integration.

A key remaining challenge is the nonlinear energy harvesting system’s sensitivity to small deviations in geometry, material properties, and excitation. In practice, such uncertainties can arise from design tolerances, variability in magnetic material coercivity, or irregular vibration inputs. Since EM harvesters couple magnetic, mechanical, and electrical domains, even minor parameter changes may drastically alter potential energy landscapes, shifting the system between monostable, bistable, and chaotic states. These phenomena fall under uncertainty amplification, which remains insufficiently explored despite its strong implications for industry.

The problem of uncertainty amplification extends beyond individual devices. In future WSN industrial deployments, many energy harvesters could operate in parallel. Lack of reproducibility among these units can compromise the reliability of entire sensor networks, where predictable power delivery is crucial. Therefore, understanding how parameter uncertainties propagate through nonlinear electromagnetic energy harvesting systems is necessary for ensuring consistent and stable performance. Although some recent works have examined probabilistic effects in bistable harvesters [

24,

25], a comprehensive study linking geometric, material, and excitation uncertainties remains missing.

To address this research gap, the presented study investigates how variations in geometry, magnetic material properties, and excitation forces affect the behavior and energy output of tunable nonlinear electromagnetic harvesters. The nonlinear magnetic restoring forces are characterized through numerical magnetic simulations, providing detailed force–displacement relationships for various magnet configurations. These data are incorporated into a one-degree-of-freedom (1-DOF) dynamic model that captures the coupled electromechanical behavior of the system. Numerical analyses are then performed to assess how uncertainties in magnet spacing, vertical asymmetry, and magnetic coercivity influence the dynamic behavior and harvested power. Additionally, the effects of excitation variability—modeled as harmonic vibration with superimposed impulsive disturbances—are explored to simulate realistic industrial conditions.

Ultimately, this work aims to bridge the gap between laboratory prototypes and mass production of field-ready devices by providing quantitative guidelines for uncertainty-aware design and calibration. The outcomes not only advance the theoretical understanding of nonlinear electromagnetic energy harvesters but also establish a foundation for scalable, predictable integration into industrial WSN and Internet of Things (IoT) platforms—where consistent and autonomous operation is crucial for the next generation of smart monitoring technologies.

2. Modelling of Energy Harvesting System

The energy harvesting system under study is a nonlinear electromagnetic vibration energy harvester (EM VEH) with tunable magnetic stiffness, as shown in

Figure 1 (B).

The harvester consists of a vibrating beam with a moving magnet, coupled to a fixed coil for electromagnetic conversion. Nonlinear restoring forces are introduced by repelling permanent magnets placed near the moving element.

Adjusting the magnet gap changes the potential landscape:

for large gaps, the system behaves as a softening monostable oscillator,

for smaller gaps, it transitions into a bistable regime with two potential wells separated by an energy barrier.

The bistable case is particularly relevant, as cross-well oscillations give the high-amplitude “high-orbit” response associated with maximum energy output. However, this regime exists alongside low-energy intra-well or chaotic solutions, making the overall response highly sensitive to system parameters. Additionally, some transversal asymmetry

is assumed, which can also alter the potential landscape and system dynamics dramatically. The possible solutions of such a system can be seen in

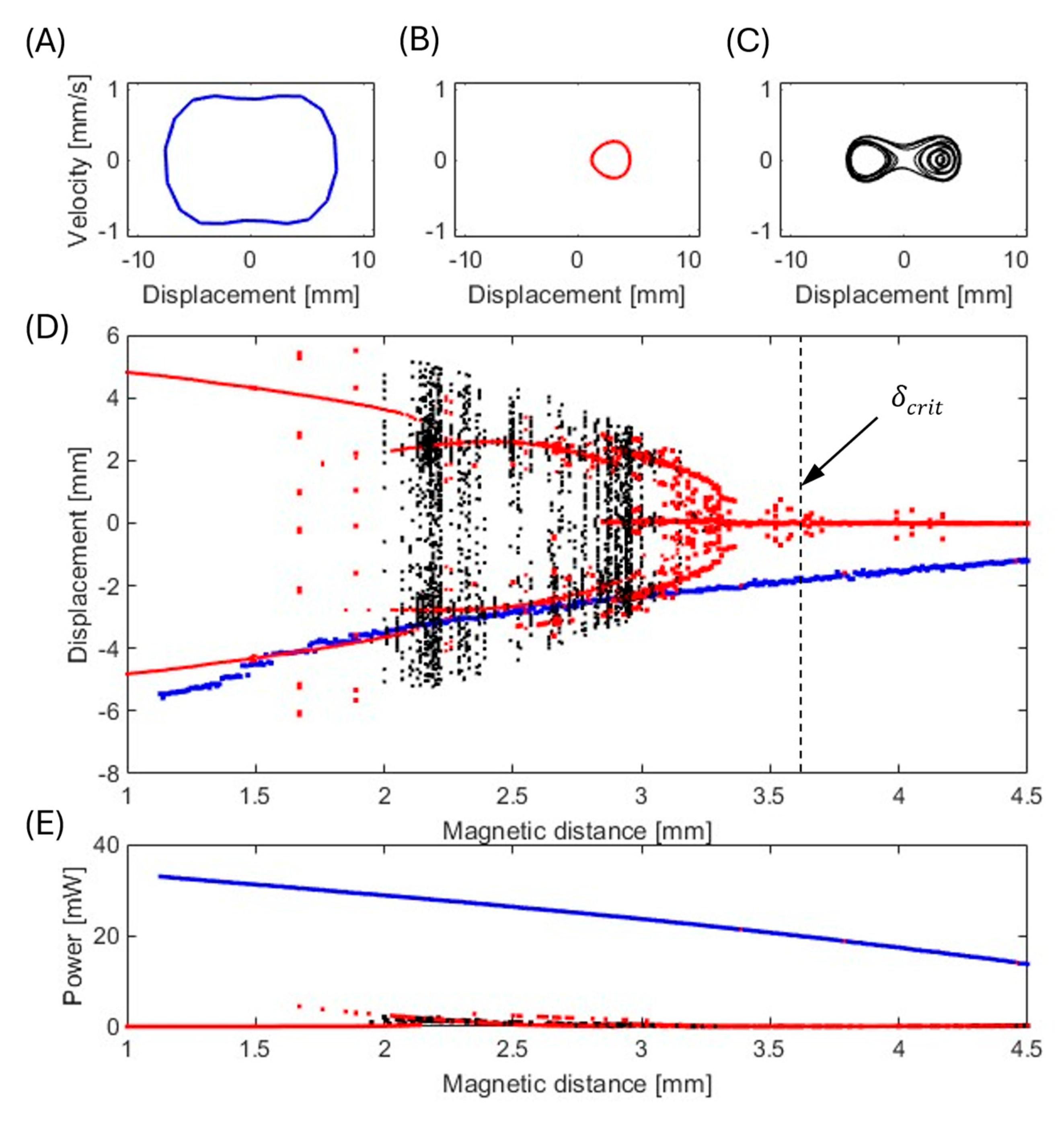

Figure 4 (A)-(C).

Figure 1.

Part (A) shows an EM VEH for railway applications developed in [

23]. Schematic representation of the nonlinear EM VEH is in part (B). The systems consist of an oscillating beam with a tip mass and an electromagnetic converter. The nonlinear version also has repelling permanent magnets, which introduce magnetic nonlinearity defined by their separation and vertical asymmetry.

Figure 1.

Part (A) shows an EM VEH for railway applications developed in [

23]. Schematic representation of the nonlinear EM VEH is in part (B). The systems consist of an oscillating beam with a tip mass and an electromagnetic converter. The nonlinear version also has repelling permanent magnets, which introduce magnetic nonlinearity defined by their separation and vertical asymmetry.

Table 1.

Overview of the discretized nominal parameters of the EM VEH.

Table 1.

Overview of the discretized nominal parameters of the EM VEH.

| Parameter |

Symbol |

Value |

Unit |

Mechanical

Mass

Damping (mechanical) |

|

|

|

|

90 |

|

|

0.034 |

|

| Stiffness |

|

3178 |

|

Electromagnetic

EM coupling

EM load resistance

Coil resistance |

|

|

|

|

13.16 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Coil inductance |

|

neglected |

|

| Excitation |

|

|

|

| Excitation amplitude |

|

range

|

|

| Excitation frequency |

|

|

|

2.1- 1-DOF Model of EM Vibration Energy Harvester

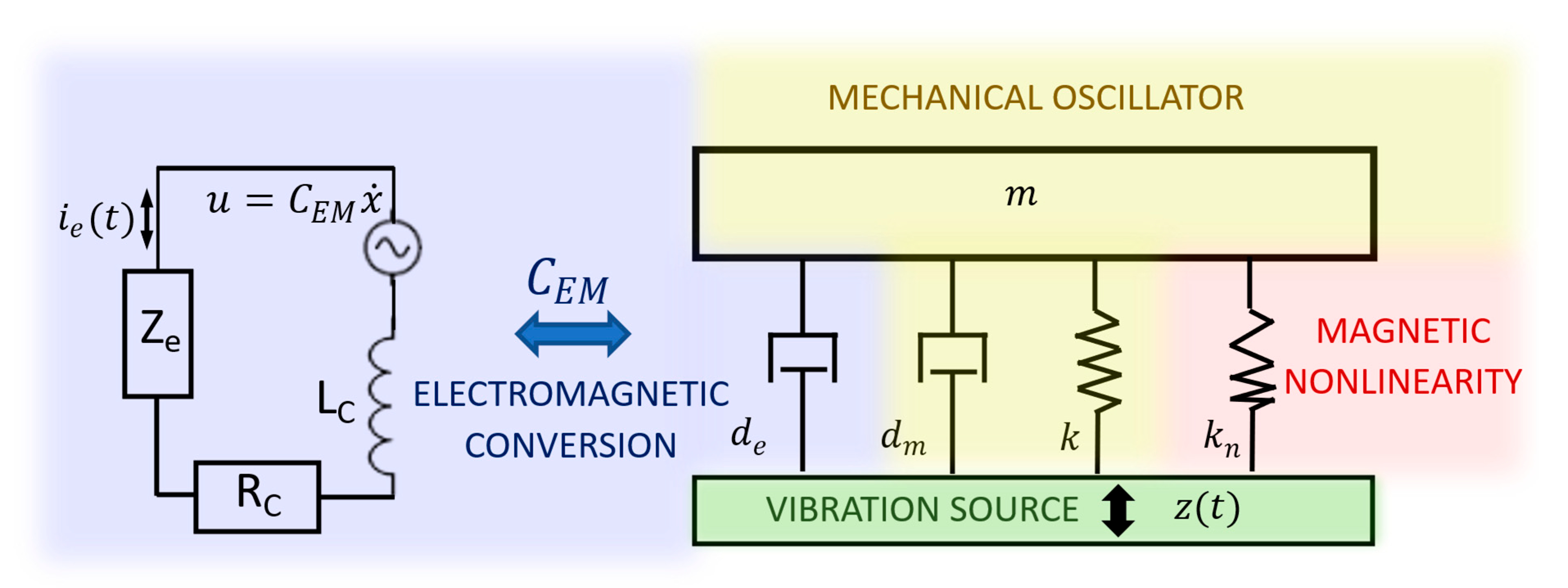

The dynamics can be captured by a 1DOF nonlinear model with magnetic stiffness and electromagnetic damping, see

Figure 2 and Equations (1)-(2). This reduced model captures the essential multiphysics coupling (mechanical–magnetic–electrical) while remaining useful for analyses with a focus on sensitivity and uncertainty.

where

is the discretized mass which includes material and geometric parameters of the cantilever beam and tip mass with both magnets,

is experimentally identified mechanical damping,

is electromechanical coupling [

23].

is the resistance of the coil,

inductance of the coil, and

is the impedance of connected electric loads to the electromagnetic converter. There are two dependent variables, deflection of the tip mass of the beam

, and current in the coil

. The following color representation of the subsystems is followed: mechanical – orange/yellow, magnetic - red, electromagnetic – blue, and excitation – green. We note that the excitation frequency

matches the resonant frequency of a linear version of the energy harvester, i.e., with magnets far apart.

The energy harvesting process can, in principle, be performed on any load

. However, in this paper, we consider the simplest case of a purely resistive load characterized by resistance

and the harvester is assumed to operate under the optimal load

And therefore, the power which is harvested by the EM VEH is calculated as

Throughout the paper, the excitation is assumed to be harmonic with a possibility of an impulse (Sec. 5), therefore

where

is the acceleration of the external harmonic force and

is its frequency. The impulse is represented by a short half-sine pulse of duration

(≈ 4 ms) and strength J, initiated at time

. The impulse term can be written as:

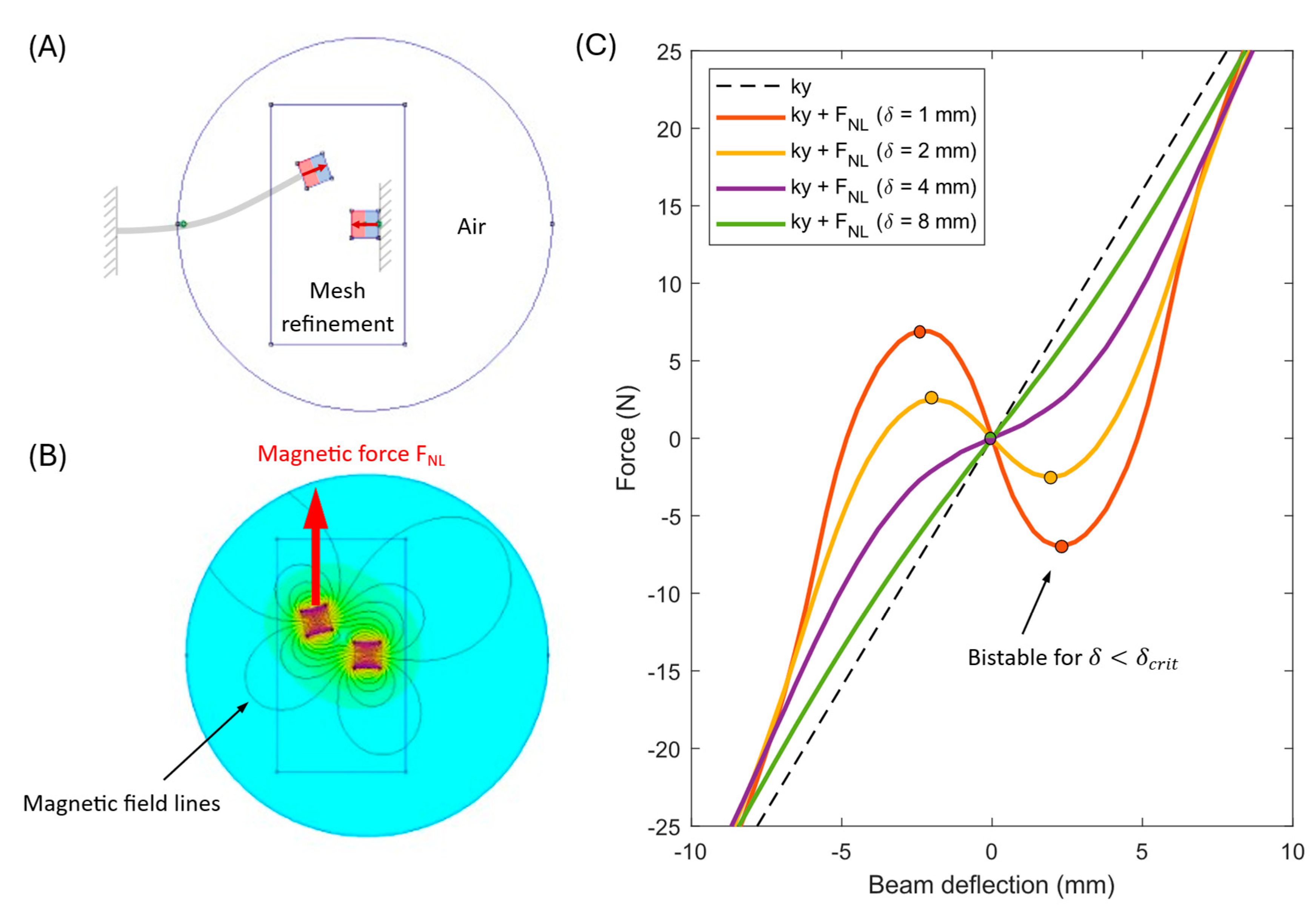

2.2. Modeling Magnetic Nonlinearity

To represent the nonlinear restoring forces, the interaction of permanent magnets is modeled numerically using Finite Element Method Magnetics (FEMM). The problem is treated as magnetostatic, since the magnetic field is time-invariant. In the simulation:

Geometry, magnet positions, and polarization directions are defined.

The nonlinear force is evaluated along the deflection axis y for different magnetic gaps .

Only the y-component of the force (aligned with beam deflection) is considered. The x-component is neglected due to the assumed small oscillation angles.

The full field distribution and corresponding force curves are shown in

Figure 3, which also illustrates the FEMM model setup. The resulting force–displacement characteristics are then incorporated into the system equations of motion.

3. Uncertainties in Magnetic Position and Geometry

3.1. Effect of Magnetic Distance on Generated Power

A critical geometric parameter of the nonlinear electromagnetic harvester is the horizontal magnet spacing

, see

Figure 1. In an idealized laboratory setup, δ is controlled precisely. However, in practical assembly, mechanical tolerances could introduce deviations on the order of ±0.1–0.2 mm, depending on machining and mounting accuracy.

The Equations (1)-(2) were numerically integrated for various magnet gaps and to evaluate the effect of on the system dynamics under harmonic excitation at frequency and amplitude , representative of typical industrial vibration conditions.

Figure 4 shows the corresponding bifurcation diagram of displacement and output power as functions of

. The results are presented for moderate excitation, where three attractors coexist—a low-energy intra-well (low-orbit) motion, a high-energy cross-well (high-orbit) response, and an intermediate chaotic regime. Simulations were performed for multiple initial displacements to identify these coexisting attractors and to map their domains of attraction. The results highlight that the system behavior is most sensitive near the boundaries between attractors, where small geometric deviations or perturbations can cause abrupt transitions between low- and high-energy responses.

Figure 4.

Effect of magnetic distance on system dynamics and harvested power. Phase portraits (A-C) illustrate possible responses for mm for various initial conditions. Plot (D) shows the bifurcation diagram of displacement over magnetic distance. The value denotes the boundary between monostable and bistable regimes. The corresponding average power as a function of magnetic distance is shown in (E). The favorable high-orbit is shown in blue, chaotic behavior in black, and red are other low-orbit solutions.

Figure 4.

Effect of magnetic distance on system dynamics and harvested power. Phase portraits (A-C) illustrate possible responses for mm for various initial conditions. Plot (D) shows the bifurcation diagram of displacement over magnetic distance. The value denotes the boundary between monostable and bistable regimes. The corresponding average power as a function of magnetic distance is shown in (E). The favorable high-orbit is shown in blue, chaotic behavior in black, and red are other low-orbit solutions.

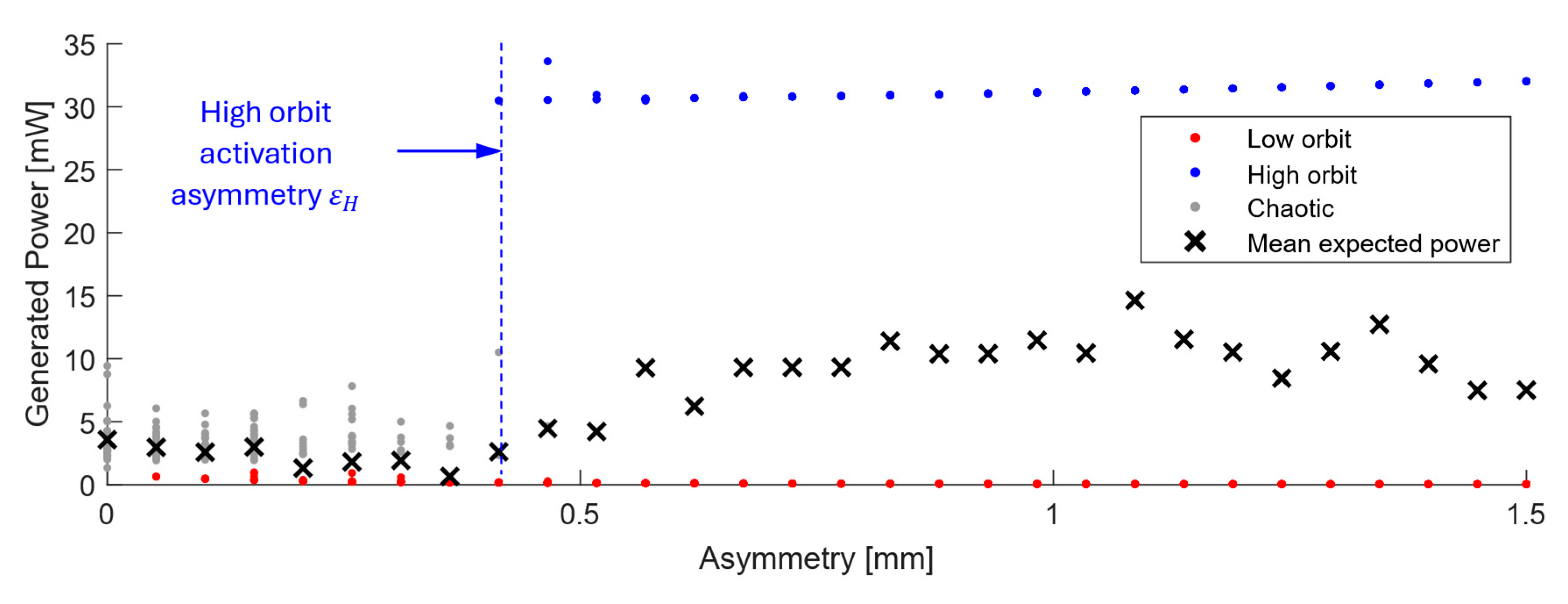

3.2. Effect of Magnetic Asymmetry on Power Generation

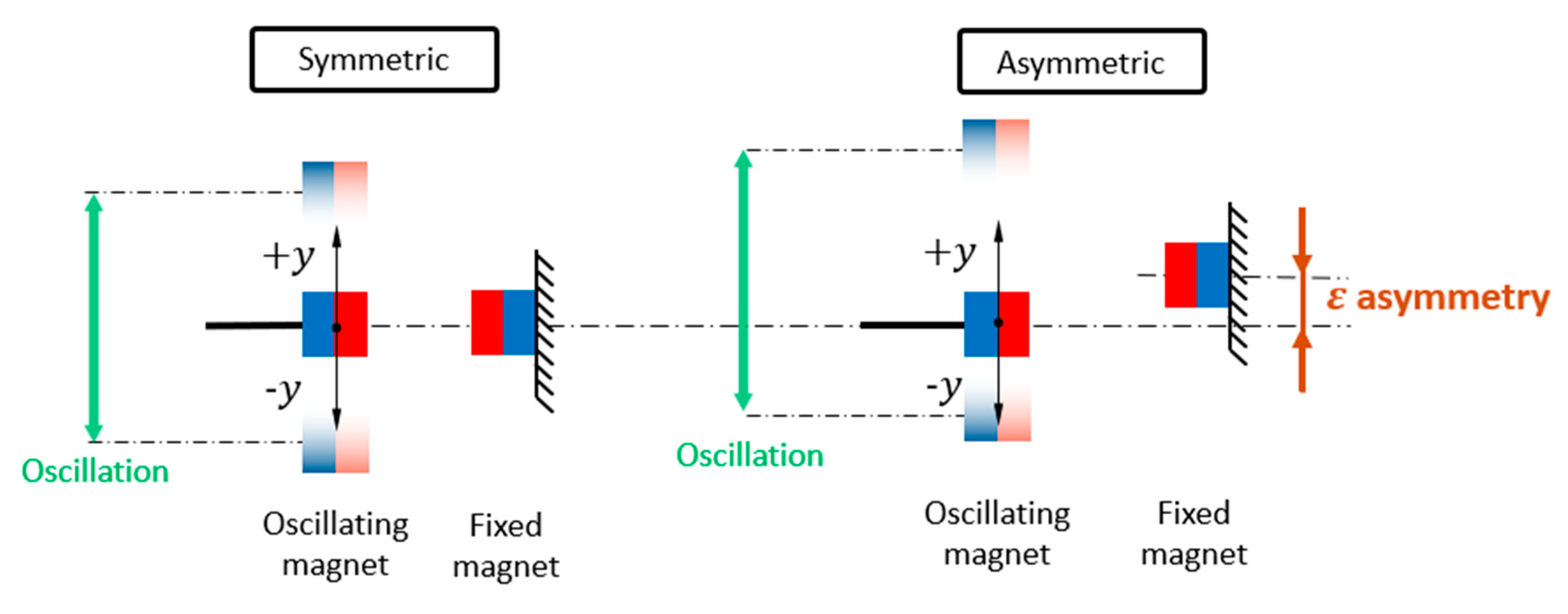

The role of vertical asymmetry ε in the placement of the nonlinear magnet was systematically investigated for both monostable and bistable configurations of the electromagnetic vibration energy harvester.

Figure 5 illustrates the definition of asymmetry ε and the coordinate system used in the analysis.

The results can be summarized as follows:

Monostable configuration - Asymmetry in the potential has a negligible and predictable effect.

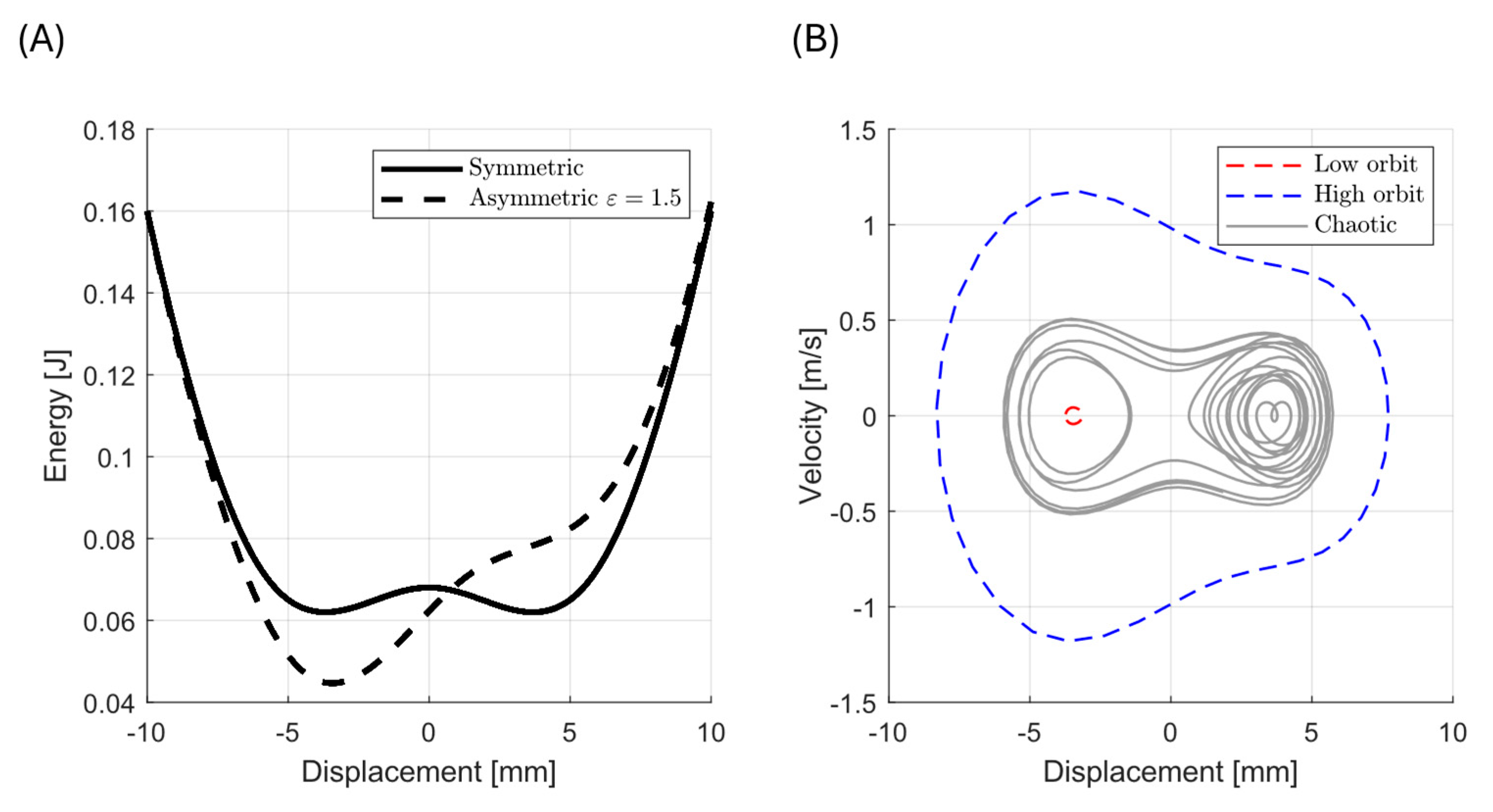

Bistable configuration:

Low excitation – The response remains trapped inside one potential well regardless of asymmetry. The harvested power is minimal, and the system is poorly utilized.

Moderate excitation (

Figure 6) – In a perfectly symmetric system, the energy barrier prevents transitions to the high orbit, and the chaotic behavior is the only possible stable solution. An introduced asymmetry lowers this barrier on one side (

Figure 7(A)), enabling cross-well oscillations and improving performance. The high orbit is activated for asymmetry values as one of the possible solutions and occurs only sometimes based on initial conditions. For higher asymmetry values, the chaotic solution no longer exists, and the mean of generated power from coexisting low orbit and high orbit solutions (see

Figure 7(B)) is bigger than that of the original symmetric chaotic solution. Therefore, controlled asymmetry could, for moderate excitation values, activate the otherwise unreachable high orbits.

High excitation – The symmetric system consistently reaches the high orbit. In this case, asymmetry is detrimental because it favors one potential well and increases the chance of the response becoming trapped in a single well, reducing harvested power.

3.3. Uncertainties in Dimensions of Magnets

Manufacturing tolerances of rare earth magnets are typically around ±0.1 mm, according to their datasheet. Although such deviations appear negligible, they directly affect the total mass of the vibrating beam. Our results show that even small mass changes can significantly influence the dynamic response and harvested power.

This highlights the need to account for real mass values during both modeling and assembly. Fortunately, such deviations can be compensated for by mass tuning, for example, by adding or removing small additional weights during assembly. In this way, the unfavorable impact of dimensional tolerances can be minimized, ensuring consistent energy harvesting performance across devices.

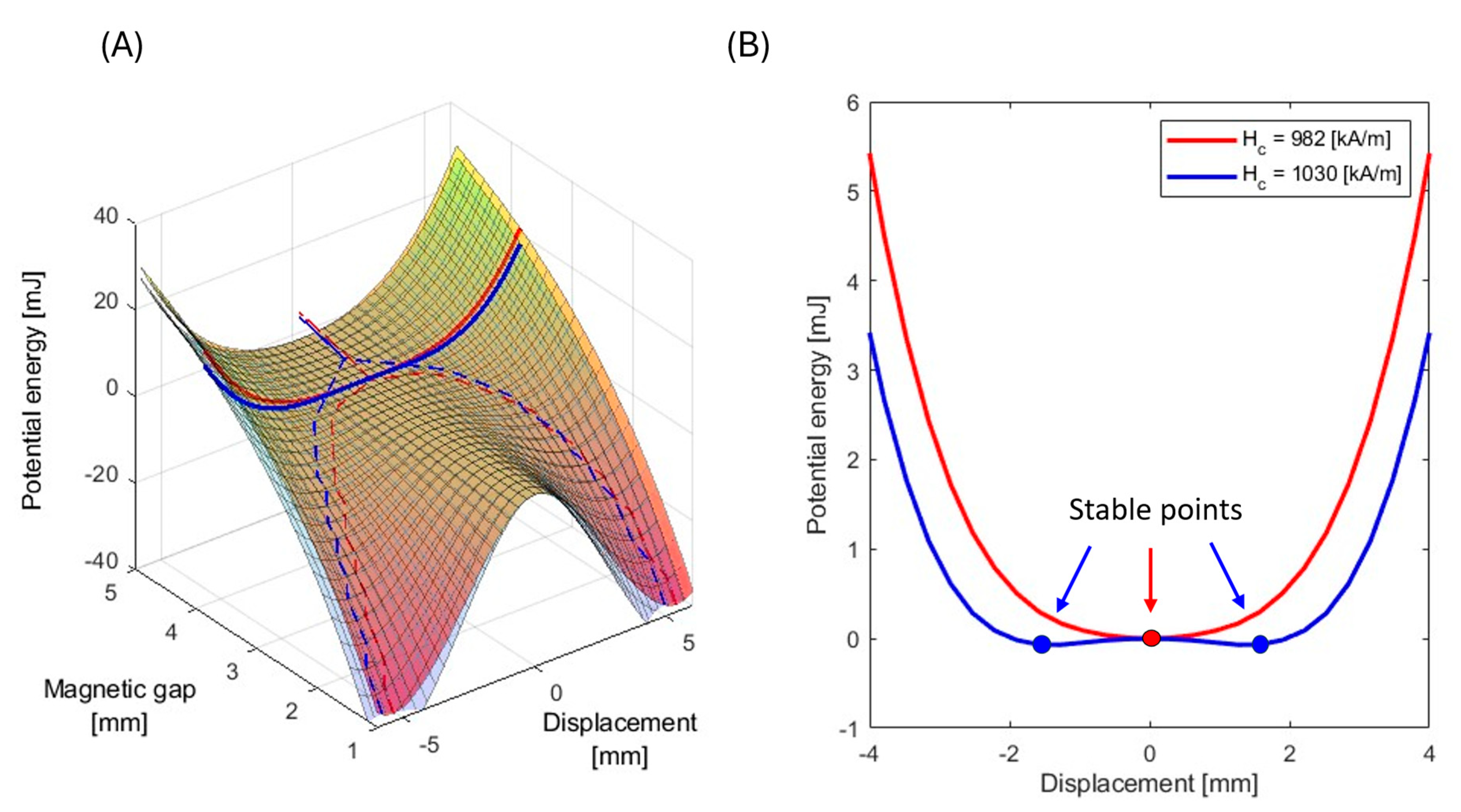

4. Uncertainties in Magnetic Material Properties - Coercivity

4.1. Definition of Materials and Variability Sources

Beyond geometry, material uncertainties of the magnets represent another critical sensitivity factor. Magnets of the same grade (e.g., NdFeB N42) and the same dimensions often show small but non-negligible differences in coercivity due to material inconsistencies or magnetization defects.

In particular, coercivity — a material property defining resistance to demagnetization — is a critical parameter. For a magnet with dimensions which is typically used in these VEHs, its magnetic properties are defined with maximum energy product = .

Coercivity is calculated from the maximum energy product using empirical formula:

Which can result in coercivity:

This seemingly small variation represents a critical source of uncertainty, as it directly influences the shape and depth of the magnetic potential well.

4.2. Effect of Coercivity Uncertainty on Potential Landscape

Using the magnetic force data (Sec. 2.2.) for the two boundary values of coercivity, we compute the magnetic potential energy by numerical integration, since:

This is combined with the linear elastic energy

to obtain the total potential energy landscape, which governs the harvester’s dynamic behavior. The simulation results are shown in

Figure 8.

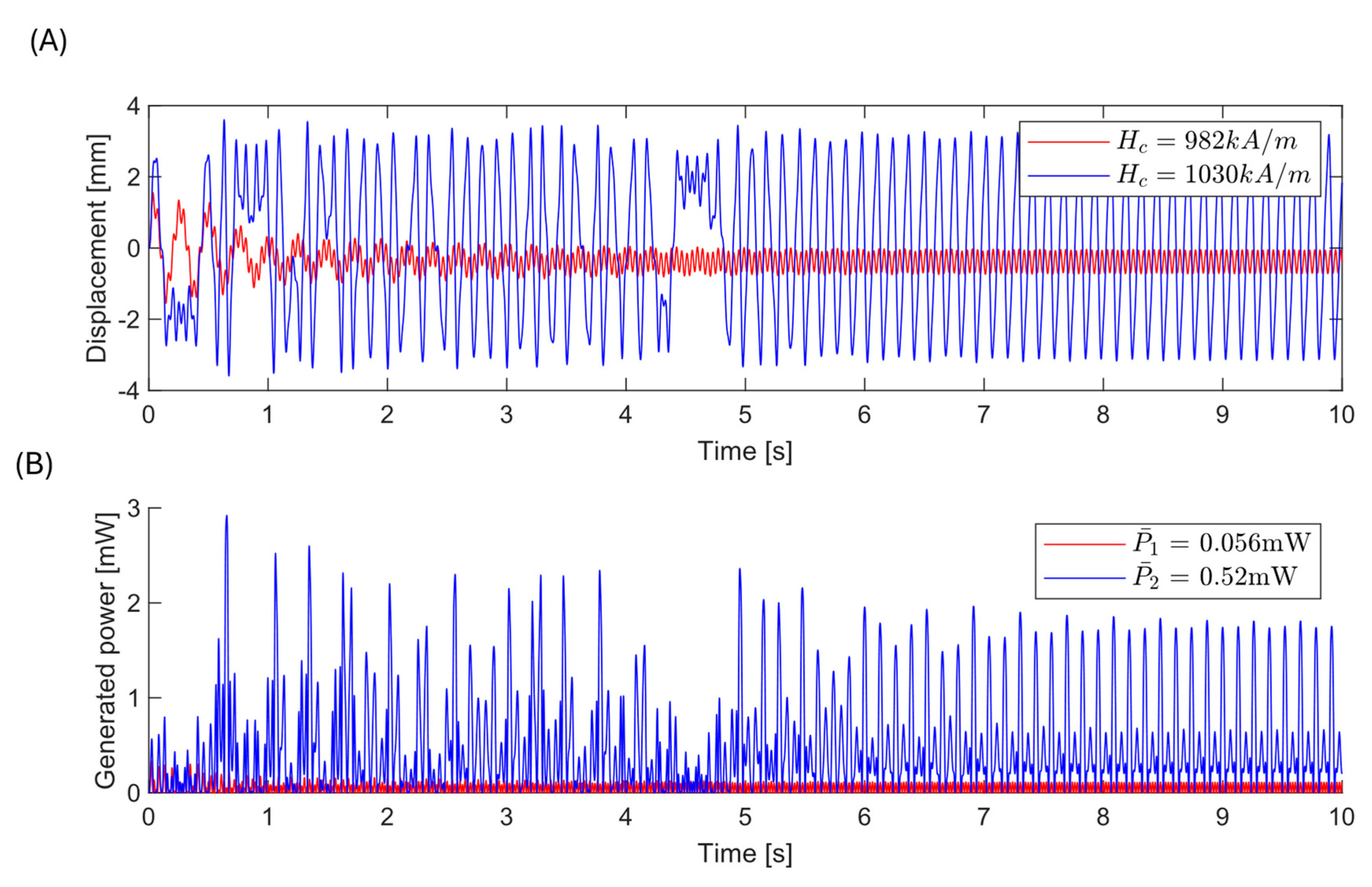

It is particularly important to pay close attention to magnet gaps near the boundary between the bistable and monostable regimes, since small parameter changes can cause abrupt transitions in system behavior. This effect is clearly illustrated for the representative magnetic gap of δ = 4 mm, see

Figure 9. Suppose one harvester is precisely tuned to operate at δ = 4 mm like a monostable oscillator using a magnet with coercivity

. Another nominally identical harvester, assembled with magnets of slightly higher coercivity

, will exhibit a distinctly different bistable potential landscape, and its power generation may be drastically affected.

The findings here reinforce the broader message introduced in previous chapters: nonlinear electromagnetic VEH systems are highly sensitive to parameter variation, and uncertainty in magnetic properties can dominate system behavior. To ensure a robust design:

Coercivity should be measured or guaranteed within narrow bounds before magnet integration.

Fine-tuning of magnet spacing after assembly can compensate for material variability, ensuring consistent operation across devices.

5. Uncertainties in Loads

5.1. Excitation Impulses as a High-Orbit Operation Tool

The previous chapter (Ch. 3) showed that small asymmetries or parameter shifts can help a nonlinear electromagnetic harvester reach high-amplitude orbits under moderate excitation. When the excitation is too weak, however, even controlled asymmetry cannot trigger cross-well motion. Another possible mechanism involves uncertainty of excitation, i.e., short impulsive events capable of activating the high-energy regime.

Industrial vibration signals typically exhibit a dominant periodic component accompanied by occasional transient disturbances. Therefore, the external excitation can be reasonably modeled as a primary harmonic component superimposed with an impulse term that accounts for either stochastic disturbances or deliberate triggering events. Such impulsive excitations may arise from gear tooth impacts, sudden load changes, electrical commutations, or other irregular machine operations.

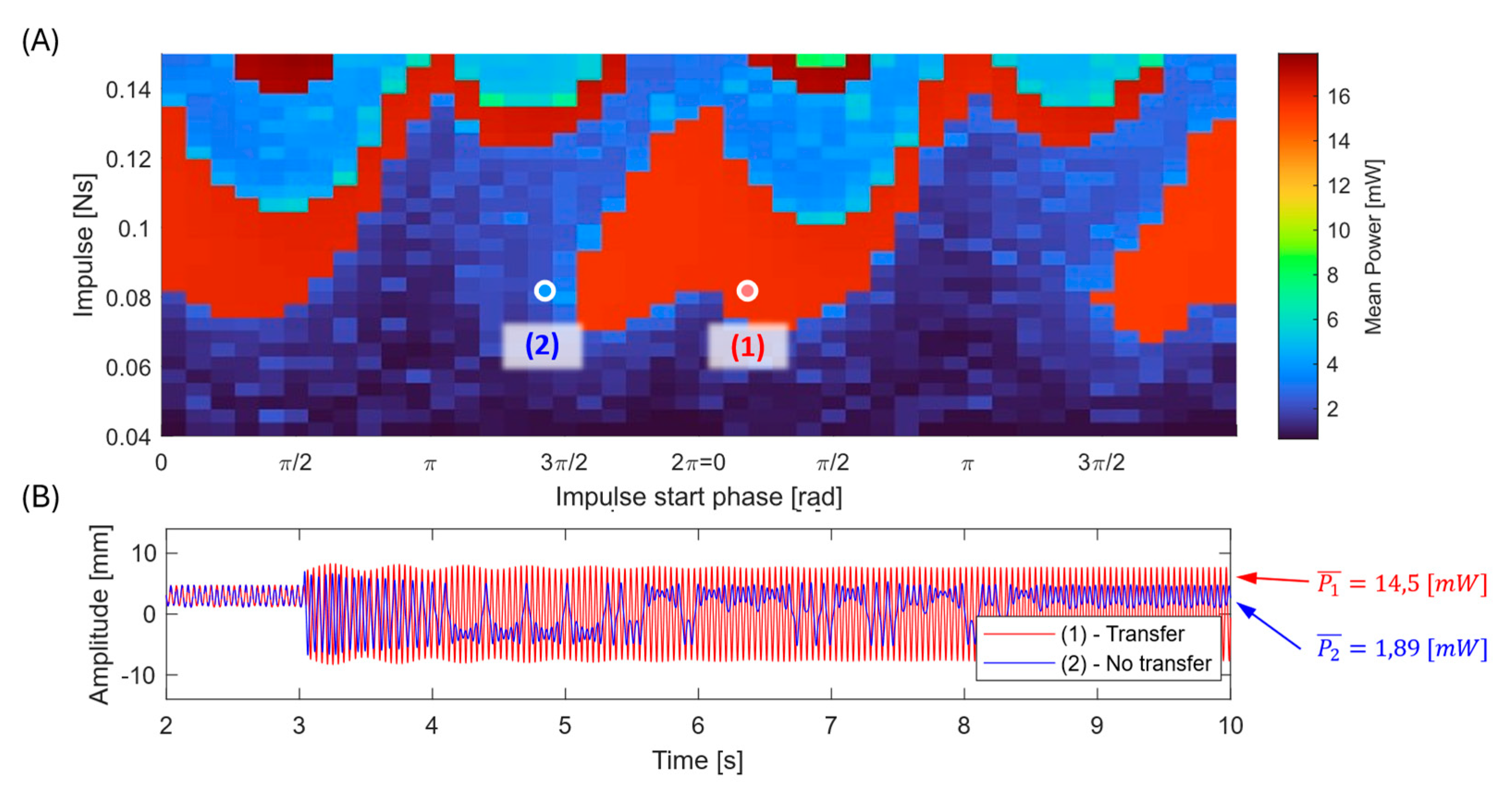

To evaluate the impact of impulsive disturbances, the EM VEH was simulated under varying impulse onset times and amplitudes, following the formulation given in Equations (5) - (6). The resulting responses are illustrated in

Figure 10. Numerical simulations show that:

The system response repeats every excitation period.

There exists an optimal impulse strength maximizing the chance of reaching the high orbit.

Too weak impulses leave the motion trapped; too strong ones overexcite the system, and its behavior is more unpredictable.

Large impulses affect the generated power even if the system doesn’t make the jump.

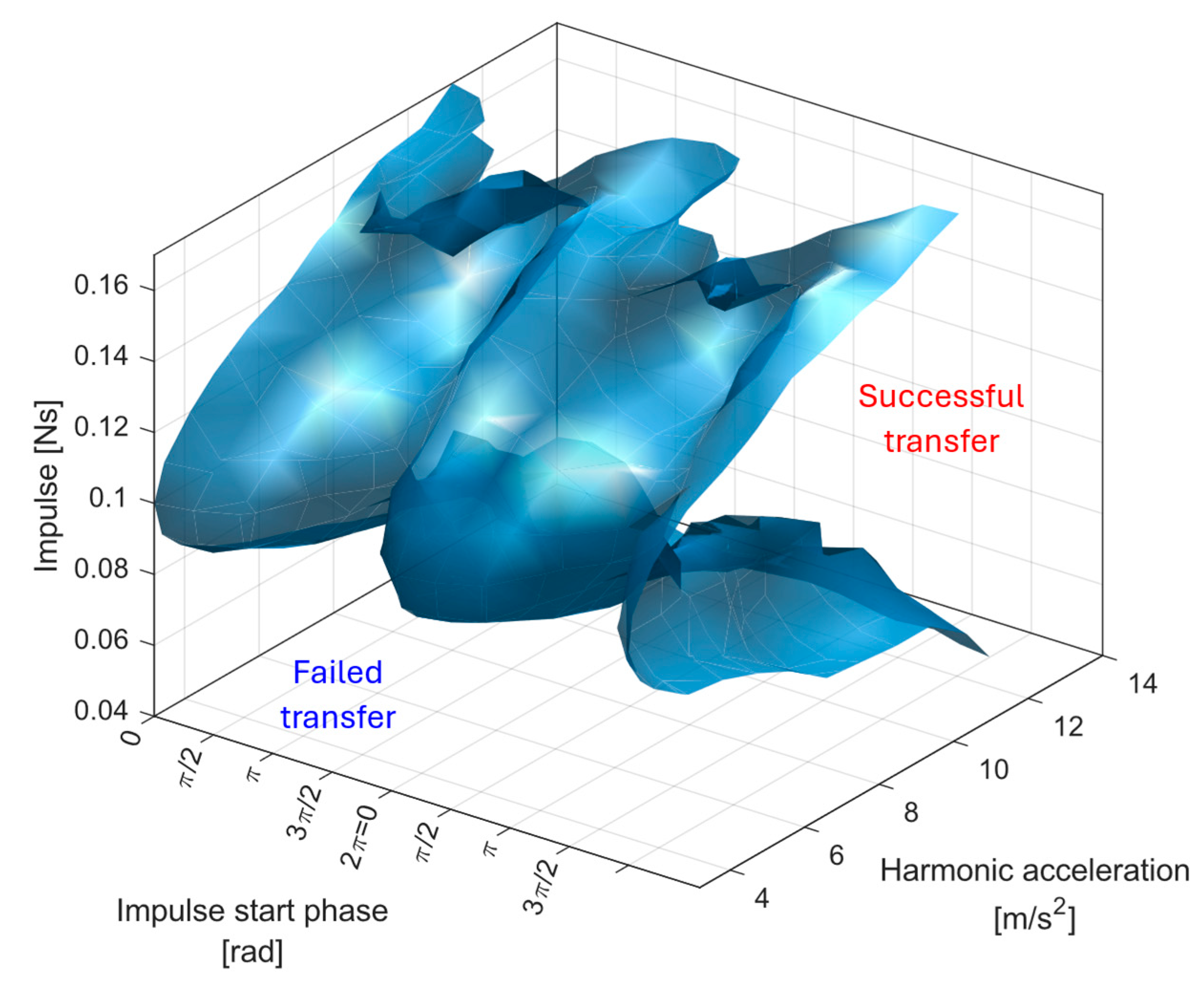

Further simulations for various harmonic amplitudes

(see

Figure 11) reveal that impulsive excitations are most beneficial in the moderate-excitation regime—strong enough to overcome the potential barrier, yet below the threshold where the harmonic force alone ensures high-orbit motion. This map illustrates the regions of excitation configurations that allow transitions to the high-orbit regime versus those that do not.

5.2. Uncertainties in Electrical Load

The analyzed EM VEH could be used to power the data transmission of an autonomous sensor node that measures strain on a structure under vibration, as a similar lab self-power wireless sensor was developed and tested in our lab [

26]. For such a self-monitoring wireless task, an average of 7mW of power is required for its continuous operation, with a power consumption of 4mW for sensing and a power consumption of 12mW for transmission of data. Advanced control of sensing, transmitting, and idle operation modes has a significant impact on the coupled electromagnetic force in Equation (1). In the case of dynamic responses of a nonlinear energy harvesting system, the advanced control of current by power consumption could be in the form of active excitation impulses, as was presented in the previous subsection. It is evident that control of output power consumption can significantly affect the coupled electromagnetic force, which, in the form of variable feedback force, affects the solution, as shown in

Figure 10. An active approach to managing electricity consumption and influencing the solution of a nonlinear energy harvesting system deserves deeper analysis in a new research paper.

Interestingly, the irregular impacts present in industrial excitation spectra—traditionally seen as noise—need not be detrimental. It is clear from the results of this chapter that random impulses can help the harvester jump from low- to high-energy orbits. Two approaches emerge:

Passive use – design the harvester so it can naturally respond to random shocks, letting these occasional disturbances push it into the high-energy regime.

Active use – apply controlled electrical impulses when the system operates in low-energy states.

Understanding uncertainties in both excitation and electrical load, therefore, complements geometric and material analyses, offering a clear path toward robust and adaptable nonlinear electromagnetic harvesters.

6. Discussions

Uncertainties play a defining role in the behavior and industrial deployment of nonlinear electromagnetic vibration energy harvesters. The harvester exhibits optimal performance when operating in the high-amplitude, or high-orbit, regime, where energy conversion is maximized. Achieving and maintaining this effective regime requires careful consideration of:

Magnetic material properties,

Horizontal magnet position (δ), and

Vertical magnet position (ε).

The results show that even small variations in these parameters—well within typical manufacturing tolerances—can lead to large differences in dynamic response. Consequently, two harvesters with identical nominal specifications may exhibit entirely different operational regimes: one functioning efficiently in the desired nonlinear orbit, while another remains confined to a low-energy state.

At the same time, the same mechanisms that introduce uncertainty can also be leveraged for performance tuning.

Controlled asymmetry or transient impulses can assist transitions into the high-energy orbit under weak or moderate excitation.

Adjustable magnet positioning in longitudinal and transverse directions enables post-assembly fine-tuning of individual devices.

It is therefore clear (from

Figure 4 and

Figure 6) that the high orbit is capable of generating the required power for the continuous operation of industrial wireless sensor nodes. However, the chaotic or low-orbit behavior is not capable of harvesting the required outputs. The active approach for control of power consumption of WSN should also be a way to change the chaotic or low-orbit behavior into a high-orbit solution with sufficient power output.

7. Conclusions

From a design perspective, mechanical adjustability and wide basins of attraction are essential for robust operation of industrial energy harvesting systems for WSNs. Parameter deviations and uncertainties cannot be eliminated, but they can be quantified, understood, and harnessed—allowing each harvester to be calibrated for optimal performance in its specific deployment environment.

In industrial mass production, such tuning can be achieved, for example, by fine-adjusting magnet spacing during final assembly or maintenance, much like the calibration of sensors or mass-balancing of rotating machinery. Implementing simple mechanical adjustment screws would enable in-situ optimization and consistent energy output despite small geometric deviations or changing vibration sources.

The lack of reproducibility represents a critical challenge for small-series industrial production and integration into larger WSN or IoT frameworks, where consistent and predictable performance across devices is essential. This work demonstrates that the reliability of large-scale autonomous sensing systems depends not only on the performance of individual nonlinear electromagnetic harvesters but also on their reproducibility across multiple units. The sensitivity of bistable and tunable magnetic systems to small parameter deviations highlights the need for design concepts that ensure repeatable operation across devices produced within standard manufacturing tolerances.

By combining sensitivity analysis, parameter control, and post-assembly tuning, reproducible performance can be achieved even in small-series production. These strategies support scalable industrial deployment of nonlinear vibration energy harvesting technology for autonomous sensing and predictive maintenance in the railway and aviation industries.

Future work will focus on automated calibration and self-tuning mechanisms that compensate for magnetic and geometric tolerances, enabling consistent plug-and-play integration of energy harvesters into industrial WSN and IoT systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Zdenek Hadas; data curation, Zdenek Hadas and Petr Sosna; formal analysis, Petr Sosna; funding acquisition, Zdenek Hadas; investigation, Zdenek Hadas and Petr Sosna; methodology, Petr Sosna; project administration, Zdenek Hadas; resources, Zdenek Hadas and Petr Sosna; software, Petr Sosna; supervision, Zdenek Hadas; validation, Zdenek Hadas and Petr Sosna; visualization, Petr Sosna; writing - original draft, Petr Sosna. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This publication was supported by the project “Mechanical Engineering of Biological and Bio-inspired Systems”, funded as project No. CZ.02.01.01/00/22_008/0004634 by Programme Johannes Amos Commenius, call Excellent Research. Additionally, authors gratefully acknowledge support provided by the project GAČR no. 25-14505L Advanced techniques for effective kinetic nonlinear energy harvesting technologies.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI, GPT-5, 2025) to assist in improving the clarity and readability of the text. The final version was fully reviewed and approved by the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results”.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| VEH |

Vibration Energy Harvesting |

| WSN |

Wireless Sensor Network |

| EM |

Electromagnetic |

| 1-DOF |

One Degree of Freedom |

| IoT |

Internet of Things |

| EM VEH |

Electromagnetic Vibration Energy Harvester |

| FEMM |

Finite Element Method Magnetics |

References

- M. Abdulkarem, K. Samsudin, F.Z. Rokhani, M.F. A Rasid, Wireless sensor network for structural health monitoring: A contemporary review of technologies, challenges, and future direction, Struct Health Monit 19 (2020) 693–735. [CrossRef]

- J. Zuo, L. Dong, F. Yang, Z. Guo, T. Wang, L. Zuo, Energy harvesting solutions for railway transportation: A comprehensive review, Renew Energy 202 (2023) 56–87. [CrossRef]

- A. Moslemi, M. Rashidi, A.M. Nazar, P. Sharafi, Advancements in vibration-based energy harvesting systems for bridges: A literature and systematic review, Results in Engineering 26 (2025) 104622. [CrossRef]

- C. Wei, X. Jing, A comprehensive review on vibration energy harvesting: Modelling and realization, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 74 (2017) 1–18. [CrossRef]

- P. Sosna, Z. Hadaš, D. Gaska, Uncertainty and sensitivity analysis of hybrid piezoelectric-electromagnetic kinetic energy harvesting system, (n.d.). [CrossRef]

- J. Wang, X. Qin, Z. Liu, G. Ding, G. Cai, Experimental study on fatigue degradation of piezoelectric energy harvesters under equivalent traffic load conditions, Int J Fatigue 150 (2021). [CrossRef]

- M.V. Perrozzi, M. Lo Monaco, A. Somà, Recent Advances in Translational Electromagnetic Energy Harvesting: A Review, Energies 2025, Vol. 18, Page 1588 18 (2025) 1588. [CrossRef]

- J. Wang, B. Zhao, W.H. Liao, J. Liang, New insight into piezoelectric energy harvesting with mechanical and electrical nonlinearities, Smart Mater Struct 29 (2020) 2–7. [CrossRef]

- R. Sun, Q. Li, J. Yao, F. Scarpa, J. Rossiter, Tunable, multi-modal, and multi-directional vibration energy harvester based on three-dimensional architected metastructures, Appl Energy 264 (2020) 114615. [CrossRef]

- K. Niazi, M.J.K. Parsi, M. Mohammadi, Nonlinear Dynamic Analysis of Hybrid Piezoelectric-Magnetostrictive Energy-Harvesting Systems, J Sens 2022 (2022). [CrossRef]

- X. Huang, T. Zhong, Hydrokinetic energy harvesting from flow-induced vibration of a hollow cylinder attached with a bi-stable energy harvester, (2023). [CrossRef]

- G. Tang, Z. Wang, X. Hu, S. Wu, B. Xu, Z. Li, X. Yan, F. Xu, D. Yuan, P. Li, Q. Shi, C. Lee, A Non-Resonant Piezoelectric–Electromagnetic–Triboelectric Hybrid Energy Harvester for Low-Frequency Human Motions, Nanomaterials 12 (2022). [CrossRef]

- H. Uluşan, S. Chamanian, W.M.P.R. Pathirana, Zorlu, A. Muhtaroǧlu, H. Külah, Triple Hybrid Energy Harvesting Interface Electronics, J Phys Conf Ser 773 (2016). [CrossRef]

- S. Zhou, J. Cao, G. Litak, J. Lin, Numerical analysis and experimental verification of broadband tristable energy harvesters, Technisches Messen 85 (2018) 521–532. [CrossRef]

- D. Huang, J. Han, S. Zhou, Q. Han, G. Yang, D. Yurchenko, Stochastic and deterministic responses of an asymmetric quad-stable energy harvester, Mech Syst Signal Process 168 (2022) 108672. [CrossRef]

- S. Zhou, L. Zuo, Nonlinear dynamic analysis of asymmetric tristable energy harvesters for enhanced energy harvesting, Commun Nonlinear Sci Numer Simul 61 (2018) 271–284. [CrossRef]

- P. Sosna, O. Rubeš, Z. Hadaš, Verification and analysis of advanced tuneable nonlinear vibration energy harvester, Mech Syst Signal Process 189 (2023). [CrossRef]

- M.F. Daqaq, R.S. Crespo, S. Ha, On the efficacy of charging a battery using a chaotic energy harvester, Nonlinear Dyn 99 (2020) 1525–1537. [CrossRef]

- M. Mohammadpour, S.M.M. Modarres-Gheisari, P. Safarpour, R. Gavagsaz-Ghoachani, M. Zandi, Identifying Chaotic Behavior in Non-linear Vibration Energy Harvesting Systems, Renewable Energy Research and Applications 2 (2021) 71–80. [CrossRef]

- P. Sosna, Z. Hadas, Verification of kinetic piezoelectric energy harvesting model with periodic and chaotic responses, Proceedings of the 2022 20th International Conference on Mechatronics - Mechatronika, ME 2022 (2022). [CrossRef]

- J. Margielewicz, D. Gąska, G. Litak, P. Wolszczak, D. Yurchenko, Nonlinear dynamics of a new energy harvesting system with quasi-zero stiffness, Appl Energy 307 (2022). [CrossRef]

- O. Rubes, M. Beno, P. Sosna, Z. Hadas, Electromagnetic Trackside Vibration Energy Harvester with Cantilever Beams Spring, Proceedings of the 2022 20th International Conference on Mechatronics - Mechatronika, ME 2022 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Z. Hadas, O. Rubes, F. Ksica, J. Chalupa, Kinetic Electromagnetic Energy Harvester for Railway Applications—Development and Test with Wireless Sensor, Sensors 22 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Y. Li, S. Zhou, G. Litak, Robust design optimization of a nonlinear monostable energy harvester with uncertainties, Meccanica 55 (2020) 1753–1762. [CrossRef]

- K. Yang, Q. Zhou, Robust optimization of a dual-stage bistable nonlinear vibration energy harvester considering parametric uncertainties, Smart Mater Struct 28 (2019). [CrossRef]

- O. Rubes, J. Chalupa, F. Ksica, Z. Hadas, Development and experimental validation of self-powered wireless vibration sensor node using vibration energy harvester, Mech Syst Signal Process 160 (2021) 107890. [CrossRef]

Figure 2.

Electromechanical model of the nonlinear electromagnetic vibration energy harvester showing the interaction between the mechanical oscillator with magnetic nonlinearity and the electrical conversion circuit. The electromagnetic coupling coefficient mediates energy transfer between the vibrating mass and the electrical subsystem.

Figure 2.

Electromechanical model of the nonlinear electromagnetic vibration energy harvester showing the interaction between the mechanical oscillator with magnetic nonlinearity and the electrical conversion circuit. The electromagnetic coupling coefficient mediates energy transfer between the vibrating mass and the electrical subsystem.

Figure 3.

FEMM magnetostatic model of the nonlinear magnetic force. (A) Geometry, boundary, and mesh-refined region. (B) Resulting magnetic flux density distribution which is recalculated into the magnetic force . (C) Total restoring force for several gaps . Filled markers: stable equilibria . Dashed black: linear stiffness .

Figure 3.

FEMM magnetostatic model of the nonlinear magnetic force. (A) Geometry, boundary, and mesh-refined region. (B) Resulting magnetic flux density distribution which is recalculated into the magnetic force . (C) Total restoring force for several gaps . Filled markers: stable equilibria . Dashed black: linear stiffness .

Figure 5.

Schematic representation of symmetric and asymmetric configurations of the nonlinear magnetic energy harvester. In the asymmetric case, the fixed magnets are vertically shifted by ε, introducing a misalignment in the potential landscape while the oscillation zero remains unchanged.

Figure 5.

Schematic representation of symmetric and asymmetric configurations of the nonlinear magnetic energy harvester. In the asymmetric case, the fixed magnets are vertically shifted by ε, introducing a misalignment in the potential landscape while the oscillation zero remains unchanged.

Figure 6.

Effect of asymmetry on power generation of the EM VEH. denotes the minimum asymmetry that makes reaching the high orbit possible. Simulations performed for .

Figure 6.

Effect of asymmetry on power generation of the EM VEH. denotes the minimum asymmetry that makes reaching the high orbit possible. Simulations performed for .

Figure 7.

Example magnetic asymmetry and its effect on the potential landscape (A) and possible solutions (B). The only chaotic solution for the symmetric case (grey solid line) is destroyed by the asymmetry, and low-orbit (red) and high-orbit (blue) solutions now coexist (dashed lines). Simulations performed for .

Figure 7.

Example magnetic asymmetry and its effect on the potential landscape (A) and possible solutions (B). The only chaotic solution for the symmetric case (grey solid line) is destroyed by the asymmetry, and low-orbit (red) and high-orbit (blue) solutions now coexist (dashed lines). Simulations performed for .

Figure 8.

Potential energy landscape of the energy harvesting system as a combined function of displacement and magnetic gap for lower (982, red shades) and higher (1030, blue shades) limit of coercivity (A). Dashed lines show the position of fixed oscillation points. Plot (B) shows a section of the potential for sample magnetic gap .

Figure 8.

Potential energy landscape of the energy harvesting system as a combined function of displacement and magnetic gap for lower (982, red shades) and higher (1030, blue shades) limit of coercivity (A). Dashed lines show the position of fixed oscillation points. Plot (B) shows a section of the potential for sample magnetic gap .

Figure 9.

Comparison of the behavior of two energy harvesters built with magnets of identical size and grade, which exhibit different behavior due to property variations within manufacturer-specified tolerances. Time evolution of oscillations (A) and generated power (B). Simulations performed for .

Figure 9.

Comparison of the behavior of two energy harvesters built with magnets of identical size and grade, which exhibit different behavior due to property variations within manufacturer-specified tolerances. Time evolution of oscillations (A) and generated power (B). Simulations performed for .

Figure 10.

Generated power as a combined function of impulse starting time and impulse strength (A). Examples (B) of successfully timed (red) and unsuccessfully timed impulses (blue). Simulations performed for .

Figure 10.

Generated power as a combined function of impulse starting time and impulse strength (A). Examples (B) of successfully timed (red) and unsuccessfully timed impulses (blue). Simulations performed for .

Figure 11.

Dependence of successful high-orbit transition on impulse start phase, harmonic excitation amplitude, and impulse strength. The plotted surface represents the boundary between excitation configurations that enable a transition to the high-orbit regime and those that do not.

Figure 11.

Dependence of successful high-orbit transition on impulse start phase, harmonic excitation amplitude, and impulse strength. The plotted surface represents the boundary between excitation configurations that enable a transition to the high-orbit regime and those that do not.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).