1. Introduction

The manufacturing sector is undergoing a profound transformation driven by the convergence of advanced digital technologies and artificial intelligence (AI). This evolution—commonly referred to as manufacturing digitalization—represents not merely a technological upgrade but a strategic reorientation of industrial processes toward enhanced efficiency, adaptability, and sustainability. Central to this transformation is the integration of real-time predictive models that leverage AI to anticipate system behavior, optimize operations, and enable proactive decision-making throughout the production lifecycle [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5].

The strategic frameworks of Industry 4.0 and Industry 5.0 collectively provide a comprehensive roadmap for this ongoing transformation. Industry 4.0 emphasizes the digital integration of cyber-physical systems (CPS), the Internet of Things (IoT), and cloud computing, enabling smart factories characterized by automation and seamless data exchange. Building upon this foundation, Industry 5.0 introduces principles of human-centricity, sustainability, and resilience, ensuring that technological progress aligns with societal and environmental values [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Within this context, AI-driven innovation not only accelerates operational excellence but also acts as a catalyst for inclusive, responsible, and sustainable industrial growth.

The digital transformation of manufacturing is accelerating through the adoption of AI—particularly via real-time predictive-corrective and decision-making models. These models are revolutionizing industrial operations by enabling proactive, data-driven optimization that surpasses traditional reactive approaches. This paradigm shift is supported by a convergence of enabling technologies, including big data analytics, cyber-physical systems, advanced sensor networks, high-fidelity numerical simulations, cloud computing, and human-centric design principles. Together, these components form intelligent, adaptive, cost-efficient, and sustainable manufacturing ecosystems [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19].

AI-driven predictive models constitute a cornerstone of this transformation. By continuously analyzing data from offline experiments, numerical simulations, and real-time streams from sensors, machines, and enterprise systems, these models empower manufacturers to anticipate product quality deviations, predict tool failures, optimize production processes, and respond dynamically to changing conditions. This holistic approach fosters more reliable, efficient, and adaptive manufacturing operations, positioning AI as a critical enabler of next-generation industrial systems.

This paper explores the transformative potential of AI-driven predictive data models in the digitalization of manufacturing processes, with a particular focus on their emerging role in enabling online advisory systems. These advanced frameworks deliver substantial benefits, including improved operational transparency, enhanced simulation capabilities, and intelligent decision support. However, their implementation presents critical challenges such as data availability and quality, model reliability and validation, and seamless integration into existing systems. Beyond theoretical considerations, this study reviews current industrial practices in real-time data modeling within manufacturing domains such as casting. Through a real-world case study, it highlights both the opportunities and limitations of AI-based predictive systems, offering insights into their practical deployment and strategic relevance within the broader context of Industry 4.0 and 5.0.

Furthermore, the paper examines the application of data science methodologies—including database construction, data sampling and snapshotting, reduced-order modeling, model validation, and deployment—for manufacturing processes. Key challenges addressed include data generation and sourcing for database development, ensuring data quality, filtering and mapping, and selecting appropriate data solvers and interpolation methods. The novelty of this research lies in the seamless integration of data sampling, snapshotting, solvers, interpolators, and machine learning (ML) techniques into a unified framework for optimizing manufacturing processes. The study introduces reduced-order modeling approaches and predictive strategies such as the Conditional Variational Autoencoder (CVAE), along with data training and learning techniques, and explores their application to complex manufacturing scenarios. These models offer promising solutions for significantly reducing computational resources and costs while enabling rapid predictive capabilities—particularly for multi-physical, multi-phase, and multi-scale processes.

2. Background and Theoretical Framework

The digital transformation of manufacturing is firmly anchored in the conceptual evolution of industrial paradigms, particularly those defined by Industry 4.0 and Industry 5.0. These frameworks—promoted by the European Commission and other global stakeholders—provide the theoretical and strategic foundation for understanding how AI-driven technologies, especially real-time predictive models, are reshaping industrial operations [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24].

2.1. Digitalization of Manufacturing Processes

The digitalization of manufacturing processes represents a transformative shift from conventional production methods to intelligent, interconnected systems. Guided by the principles of Industry 4.0 and Industry 5.0, this evolution reflects a transition from purely technological integration toward a more human-centric, resilient, and adaptive manufacturing paradigm. At the core of this transformation is the seamless interaction between physical processes and digital systems, enabling advanced decision-making, process optimization, operational efficiency, and production agility [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34].

A practical embodiment of this shift is the online advisory system—an AI-powered platform that leverages real-time predictive models to support process design and execution. By continuously analyzing live data from sensors, machines, and digital twins, these systems can detect potential issues such as quality deviations or maintenance needs, recommend optimal process parameters, and assist engineers in complex decision-making tasks. In the context of Industry 5.0, such systems are designed not to replace human expertise but to augment it, acting as intelligent collaborators that enhance responsiveness and precision in dynamic manufacturing environments.

Figure 1 illustrates the digitalization framework for manufacturing processes, including its workflow for data preparation and integration into digital systems.

The dynamic databases powering these systems are initially constructed using existing datasets, experimental trials, and calibrated numerical simulations, and are continuously updated with live operational data. At the heart of the online advisory system lies the system modeler, which integrates data models (e.g., solvers and interpolators) with an efficient data training module to enable accurate predictions and corrective actions. These systems are not merely automation tools—they represent intelligent, adaptive frameworks that complement human decision-making, driving responsiveness, precision, and agility in modern manufacturing [

35,

36,

37].

2.2. Process Data Handling and Processing

Manufacturing process data generation, acquisition, filtering, mapping, and management constitute a highly interconnected system that is fundamental to modern industrial operations. Data originates from four primary sources: controlled experimental setups, predictive simulation models, data-driven models, and live production environments. Acquisition typically relies on sensor arrays and embedded data collection systems integrated within the process infrastructure. Once collected, the data under-goes rigorous filtering and validation to eliminate noise and ensure integrity. A critical step is data translation and mapping, where heterogeneous inputs—such as sensor readings and simulation outputs—are harmonized into a unified format to guarantee interoperability and enable meaningful analysis.

To achieve semantic consistency, a formal ontological framework is employed. This framework defines domain-specific concepts (e.g., machine, temperature, material), organizes them through taxonomies, and establishes relationships via logical axioms (e.g., has_material, requires, is_a). It serves as a master blueprint for contextualizing data, ensuring that all information—regardless of origin—retains a clear and consistent meaning. Finally, the semantically enriched data is stored in structured databases, enabling comprehensive analysis, optimization, and informed decision-making across all stages of the manufacturing process [

38,

39,

40,

41,

42].

Figure 2 illustrates the data infrastructure and its core components, including data filters, translators, mappers, acquisition systems, and storage.

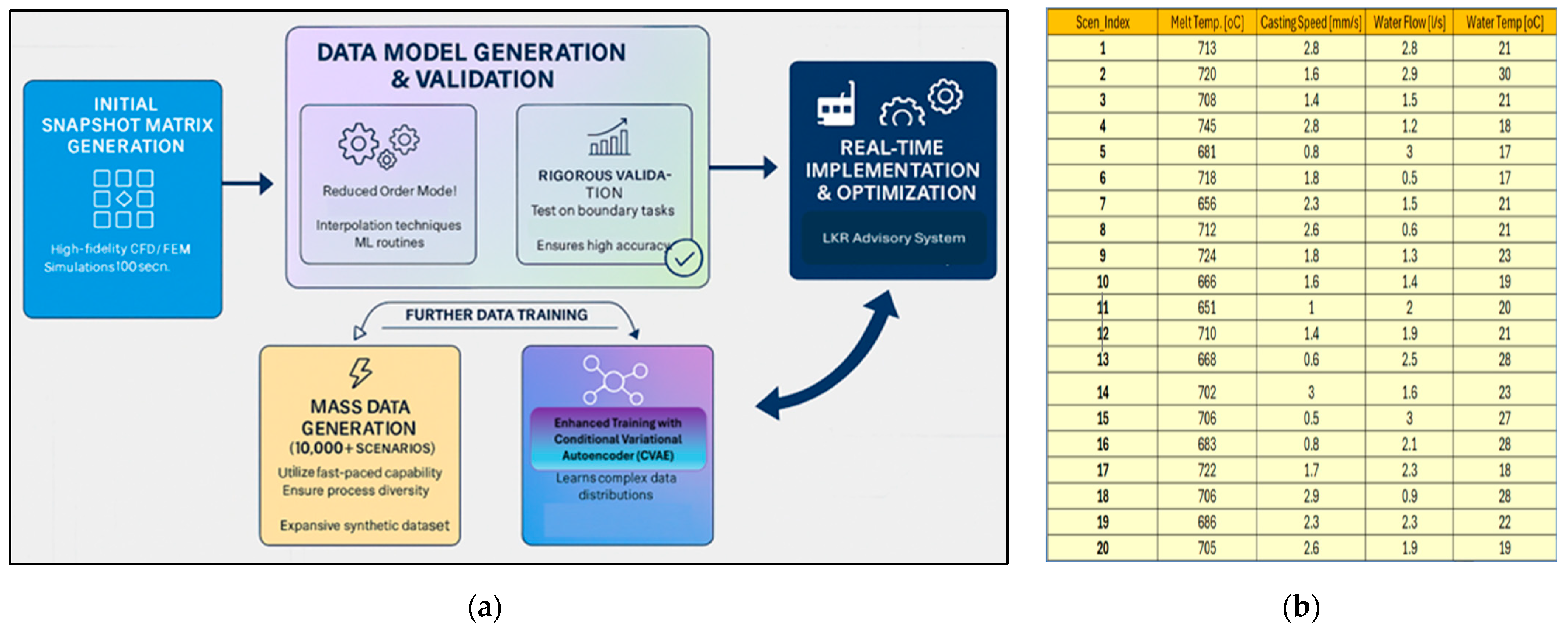

For this research, data generation was achieved through a combination of numerical simulations and large-scale synthetic data modeling, employing rigorous sampling and snapshotting techniques. At the outset of the data preparation phase, the numerical simulation model was calibrated using both experimental data and mined datasets. A strategic sampling approach was adopted to construct a snapshot matrix representing diverse process scenarios across multiple parameter combinations. This matrix was carefully designed to ensure a minimal yet sufficient data volume—optimizing computational efficiency—while maintaining a balanced distribution across the parameter space to enhance predictive accuracy. Initial data models were developed using a comprehensive process database that incorporated snapshot scenarios for all relevant process parameters.

2.3. Data Models: Key Concepts

For dynamic manufacturing processes, constructing and executing real-time data models demands a systematic, stepwise methodology to overcome the computational limitations of traditional numerical simulation tools. These processes are typically categorized as steady-state, transient, or generative, depending on their operational characteristics—each requiring tailored modeling strategies. The development of such models is guided by several key principles:

- Data Handling and Processing: Data is systematically gathered from experiments, simulations, and validated literature sources. Preprocessing steps—including cleaning, normalization, anomaly detection, and semantic mapping via ontological frameworks—are essential to ensure consistency, quality, and interoperability before data storage.

- Model Development Strategies: Steady-state modeling is applicable to stable processes with minimal fluctuations. Transient modeling captures the full dynamics of a process, including startup, ramp-up/down phases, transitions, and boundary shifts. Generative modeling is ideal for additive or block-wise processes where components are built incrementally over time.

- Solver and Interpolator Techniques: A hybrid approach is employed, combining eigen-based, regression, and clustering solvers with interpolators such as Kriging, Radial Basis Functions (RBF), and Inverse Distance Weighting (IDW). These techniques are integrated with ML routines to enhance predictive accuracy across diverse process data spaces.

- Model Validation: Robust validation ensures model reliability under normal, near-boundary, and extreme conditions. Validation techniques include neural networks, regression models, Genetic Algorithm Symbolic Regression (GASR), and tree-based approaches.

- Model Implementation: Once validated, data models can be embedded into process digitalization frameworks such as online digital advisory systems, digital shadows, and digital twins. This integration requires a resilient data infrastructure and efficient communication systems to support streamlined input/output operations.

- Model Updates: Generative loops can be used to continuously update data models with filtered live data, allowing ongoing refinement of the snapshot matrix derived from the dynamic process database.

Process modeling approaches are traditionally classified based on temporal characteristics (e.g., steady-state, transient), scaling characteristics (e.g., multi-scale, macro-scale), and physical characteristics (e.g., multi-physics, multi-phase). When developing data-driven modeling concepts for manufacturing processes, it is crucial to account for transient effects, bridge time and length scales, and incorporate phase-change phenomena. Accordingly, the integration of data science techniques into manufacturing process modeling should address the following core aspects, temporal aspects of data models, scaling aspects of data models, and physical aspects of data models. For temporal issues, some manufacturing processes can be approximated as steady-state or quasi-static, with transient effects represented through statistical or averaging techniques. Although some processes have significant startup conditions or ramp-up phases, and it is essential to explicitly model the transient evolution of materials, boundary condition changes, and process parameter variations. For spatial issues, variations in process parameters can be represented using 1D, 2D, or 3D data models. These models may incorporate multi-scale phenomena—such as microstructural evolution—through bridging techniques. Events occurring at different length scales can be modeled either in parallel or sequentially and integrated into macro-scale predictions to support process optimization and control. Finally, for the processes multi-physical aspects, a deep physical understanding of processes—including multi-physics interactions (e.g., thermal, mechanical) and multi-phase behavior (e.g., solid, liquid, solidification)—can be embedded into data models. Complex interactions are best captured through hybrid approaches that combine analytical models with data-driven methods. These models may utilize single or distributed databases, integrating both analytical and learned data to improve predictive accuracy and computational efficiency.

Figure 3 illustrates the core concepts of process data modeling and offers a framework for process characterization in data model development.

3. Process AI-Based Technologies

AI and the resulting data-driven modeling have emerged as strategic enablers for modern manufacturing industries. Their capacity to process vast volumes of process data, identify patterns, and perform predictive analytics, corrections, and autonomous decision-making positions AI as a cornerstone of smart and sustainable manufacturing. In particular, real-time predictive data models powered by AI empower manufacturers to dynamically adjust process parameters, anticipate potential failures, optimize product quality, and reduce energy consumption and operational costs with unprecedented agility.

3.1. Process Data Generation

In the context of modern manufacturing process design and control using AI-driven, data-centric techniques, process data and databases are constructed from a variety of sources to form a comprehensive and cohesive digital representation of the process. This is a multi-stage endeavor that strategically integrates diverse data types. The foundation of the database is typically built using experimental data, obtained through controlled laboratory tests and pilot-scale trials. This data is essential for calibrating numerical simulations, validating data models, and understanding fundamental process behaviors under specific conditions. Next, numerical simulation data is incorporated. This data is generated by simulating selected process scenarios to model complex physical phenomena that are often too costly or impractical to observe experimentally. These simulations provide high-fidelity insights that complement and extend the experimental findings. Live sensor data from the factory floor delivers real-time insights into ongoing operations. This includes continuous measurements of parameters such as temperature, pressure, and flow rate, which are streamed into the database to maintain an up-to-date digital twin of the physical process. All collected data is meticulously curated, filtered, and stored in a centralized database, often structured around an ontological framework.

AI plays a pivotal role in enhancing the resilience of manufacturing systems by enabling dynamic reconfiguration in response to disruptions—such as supply chain fluctuations or equipment failures. It also supports sustainability goals by optimizing energy consumption, minimizing waste, and facilitating circular production models.

Figure 4 illustrates a schematic overview of the data flow involved in process data generation, processing, and storage. It also highlights sampling techniques and snapshot methods used in constructing initial databases.

3.2. Calibrated Numerical Simulations

Experimental trials remain a critical benchmark for both the calibration and validation of numerical simulations—steps that are essential for establishing confidence in the accuracy and reliability of process models. Once calibrated and validated, these simulations can be used to generate rich datasets for data modeling, particularly for transient processes that are challenging to measure in real time. Calibration involves systematically adjusting the parameters of a numerical simulation so that its outputs closely match experimental observations. Since simulations often rely on idealized assumptions regarding material properties, boundary conditions, and process parameters, experimental data provides the necessary grounding to fine-tune these inputs. These refinements ensure that predicted cooling rates, for example, align with those measured by thermocouples during real-world trials, thereby correcting any inherent biases or inaccuracies in the model assumptions [

43].

Validated simulations can then be used to generate extensive datasets that would be impractical or impossible to obtain through physical experimentation alone. These datasets are particularly valuable for building initial process databases and supporting advanced data-driven modeling.

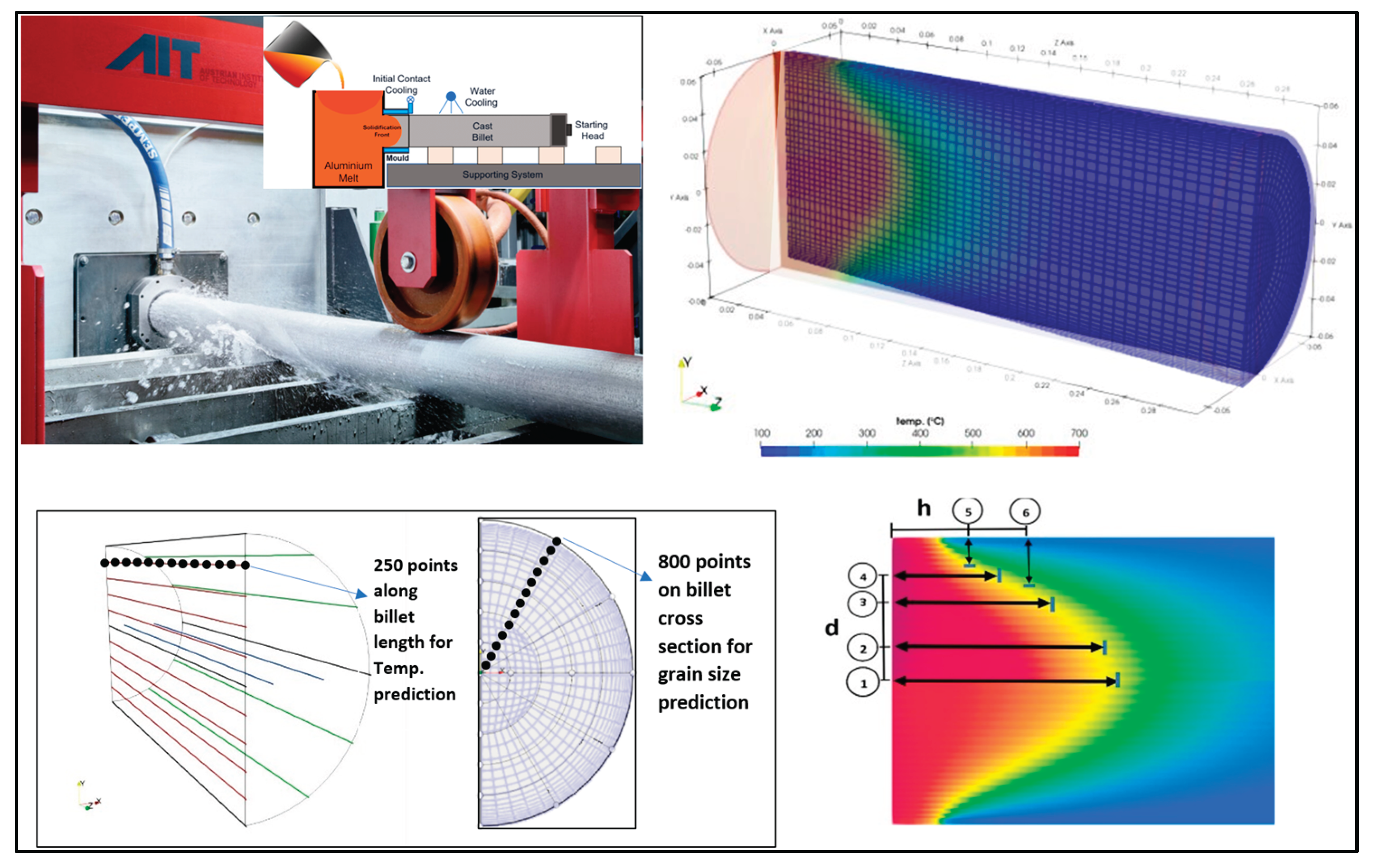

Figure 5 illustrates the workflow for generating process data based on calibrated simulation results. It includes a schematic of a casting facility, and a typical discretization of numerical domain and contour results for Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) casting simulations.

In essence, experimental data serves as the anchor of truth—a small but highly accurate dataset used to calibrate and validate numerical simulations. Once validated, these simulations become powerful engines for data generation, producing extensive datasets that would be impractical to obtain through physical experimentation alone. These datasets are then used to train the next generation of AI-driven, real-time, and adaptive process models.

3.3. Process Digitalization Frameworks

Some of the core concepts of manufacturing digitalization can be distilled into the development of online advisory systems, digital shadows, and digital twins, and their interconnection with process modeling, data models, and data infrastructure. These elements represent a fundamental integration of the physical and digital realms, built upon several key components: robust data infrastructure, system modelers such as real-time data models, and the frameworks of digital shadow and digital twin. Together, they form the foundation of a comprehensive process digitalization strategy. Digital advisory systems, both online and offline—are increasingly recognized as essential enablers of smart manufacturing within the Industry 4.0 and 5.0 paradigms. These systems extend beyond basic automation by offering decision-support capabilities, process design tools, and operational guidance for engineers and operators. Their primary objective is to improve efficiency, quality, and predictive accuracy while preserving human oversight, thereby promoting a human-in-the-loop approach that harmonizes automation with expert judgment.

Modern advisory systems leverage hybrid architectures that integrate analytical and rule-based logic with AI-driven models. This combination allows deterministic decision rules to coexist with adaptive learning mechanisms that draw from process databases and live data streams. While analytical routines are effective for embedding domain expertise in well-defined scenarios, AI components—including generative models—enable dynamic optimization, anomaly detection, and predictive analytics across complex and variable process conditions. A central architectural feature of digital advisory systems is the use of predictive models trained on historical and real-time data, which power dashboards, generate design alerts, and offer simulation-based optimization recommendations. These capabilities enhance digital twins—virtual representations of machines or entire production lines—by enabling outcome simulations prior to implementation, thereby reducing risk and increasing decision confidence.

Although process operators retain ultimate authority over whether to act on system-generated advice, the human-in-the-loop paradigm is reinforced through immersive real-time data modeling technologies. Nonetheless, several challenges remain, including limitations in data availability, quality, and distribution, moderate implementation costs, and ongoing gaps in the development and integration of AI and digital technologies. In contrast, digital shadow is a passive, one-way digital representation of a physical process, where data flows from the physical system to its digital counterpart without any feedback or control in the reverse direction. It serves as a live snapshot of the physical object's state at any given moment, enabling real-time or near-real-time monitoring and descriptive analytics. While digital twin is a more advanced and high-fidelity virtual framework that enables a two-way, real-time feedback loop between the physical process and its digital replica. It facilitates modeling, simulation, prediction, optimization, and control of manufacturing systems. A digital twin integrates physics-based models, AI-driven data models (such as real-time predictive models), and a robust data infrastructure.

AI-based real-time models—often built using solver-interpolator combinations and ML algorithms—learn the relationships between process parameters and outcomes. They enable the creation of lightweight, predictive replicas of the system modeler, enhancing responsiveness and adaptability.

Figure 6 illustrates the key digitalization frameworks for manufacturing processes, highlighting the roles of digital shadow and digital twin in enabling smart, data-driven production environments.

4. Real-Time Predictive Models

The integration of data science techniques into manufacturing process modeling has advanced rapidly in recent years, driven by the growing need for faster predictions, deeper process insights, and improved operational efficiency. Traditionally, process modeling was grounded in analytical formulations, empirical correlations, and physical experimentation. Over time, these methods evolved into sophisticated numerical simulation techniques, which—enabled by increasing computational power—allowed for multi-scale modeling of complex physical phenomena. This convergence of data science and process engineering represents a paradigm shift toward more intelligent, adaptive, and scalable manufacturing systems—where predictive accuracy, responsiveness, and operational agility are significantly enhanced.

Traditional modeling approaches for metal manufacturing processes encompass a broad spectrum of techniques, including steady-state and transient modeling, multi-physical and multi-phase modeling, multi-scale and interactive modeling, and hybrid analytical–numerical frameworks. The integration of data science is reshaping how these models are developed, calibrated, and applied, introducing new capabilities for predictive accuracy, scalability, and computational efficiency. The evolution of data modeling techniques in this context can be associated with the real-time data models which are constructed using three core components: data solvers, interpolators, and robust ML modules. Various mathematical techniques can be employed to build efficient data solvers, including eigenvalue-based methods, regression, and classification algorithms. For interpolation during process prediction, techniques such as RBF and inverse distance weighting (IDW) are commonly used. Additionally, ML methods like neural networks (NN), genetic algorithms, and symbolic regression can be incorporated into the data model framework to support data training and pattern recognition. In this research work, eigenvalue-based solver techniques have been applied to disentangle process data resulting from variations in process parameters. To create a reduced order model of a complex dynamic system or process, let’s consider a dynamic mechanical system as [

35]:

where

,

, and

can be considered as stiffness, mass, and damping matrices, respectively. The

and

are the displacement and dynamic force vector. The construction techniques for reduced-order models of mechanical vibrating systems were detailed in [

35]. In contrast, for transient processes involving thermal evolution—such as casting—the governing equations can be formulated as follows:

where

is the density,

is the specific heat,

T is the temperature,

k is the thermal conductivity, and

Q represents heat generation. Discretizing the domain leads to a system of ordinary differential equations:

where [

M] is the thermal capacity matrix, [

K] is the thermal conductivity (stiffness) matrix, and [

Q(t)] represents heat flux and boundary conditions. Like the mechanical vibrating systems in [

35], to reduce the order of the system, the temperature field can be expressed as a linear combination of spatial eigenmodes and temporal coefficients:

Here,

are spatial basis functions (eigenmodes), and

are time-dependent modal coefficients. To create data reduced version of these systems, the same concept can be extended to data matrices derived from dynamic thermal or mechanical system responses (e.g., from simulations or experiments). Instead of assembling physical system matrices (e.g., stiffness, thermal capacity…), the data-driven approach uses eigen-decomposition of system response matrix to extract system characteristics, significantly reducing computational effort and enabling real-time predictions for new input scenarios. An alternative data-driven formulation of the system thermal response can be expressed as:

where

is the system characteristics derived via eigen-based techniques,

represents the input process parameters, and

is the predicted system thermal response. To further decompose the system’s tempo-spatial behavior, data science techniques such as Proper Orthogonal Decomposition (POD) or Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) can be applied:

where

U represents spatial eigenvectors,

∑ is the diagonal matrix of singular values (eigenvalues), and

captures the temporal dynamics. By projecting the scenarios in snapshot matrix onto the most influential eigenmodes (those with the highest energy in

Σ), the system can be reconstructed using a reduced-order model. This significantly reduces the size of the system matrices, enabling fast, real-time predictions for ongoing processes.

Figure 7 illustrates the workflow for constructing data models within the context of process digitalization, emphasizing their central role in the digital transformation of manufacturing industries. The figure outlines the key components of a data model system, including the database derived from calibrated simulations, model builder tools, validation mechanisms, and ML routines. This framework offers a structured approach to managing process data as a strategic asset, supporting optimization and control across the entire production chain.

5. Case Studies and Applications

To demonstrate the practical application of digitalization in manufacturing processes, this study presents a real-world case study focused on a steady-state casting operation. By excluding transient behaviors typically associated with process initiation, the analysis concentrates on stable process conditions, allowing for a more controlled and focused evaluation. The implementation incorporates key digitalization components, including data acquisition, preprocessing, modeling, and training using the CVAE technique. This approach supports the development of an online advisory system capable of delivering real-time insights and actionable recommendations. The study specifically examines the evolution of thermal fields and microstructural characteristics, with predictive modeling of spatial temperature distributions and grain size variations at selected locations and cross-sections within the casting domain. These results highlight the potential of AI-enhanced data modeling to support process optimization and informed decision-making in smart manufacturing environments.

Developing an online advisory system for casting processes enables the evaluation of diverse operational scenarios under varying process parameters and boundary conditions, particularly during the early stages of process design. Casting is inherently a multi-physical, multi-phase, and multi-scale process, where macro-scale thermal fields significantly influence solidification dynamics and microstructural evolution at finer scales. The digitalization of casting presents several challenges, especially in data generation, handling, training, and predictive model development across different length scales. Addressing these challenges is essential for building robust, scalable, and intelligent systems that can adapt to complex manufacturing environments.

To develop a virtual replica of the casting process, a comprehensive framework was implemented, integrating data infrastructure, system modeling, machine learning-based data training, and a web-based advisory interface. The methodology adhered to the steps outlined in

Section 2.3, where key principles were applied to establish a robust AI-driven advisory system. Following the acquisition of process data from calibrated simulation scenarios, data models were constructed and validated to generate extensive training datasets for the CVAE system. These components were subsequently integrated into the final web-based advisory platform, enabling real-time process monitoring and decision support. System performance throughout the development stages was assessed using error indices and predictive metrics. In the initial phases, when data availability was limited, the models relied on correlation analyses of deterministic scenarios, laying the groundwork for scalable, data-driven process optimization.

5.1. Data Generation

For the numerical simulations of the snapshot matrix scenarios, fixed-domain fluid–thermal CFD models were employed to analyze thermal evolution and solidification behavior during the casting process. The open-source solver directChillFoam [

44], developed within the OpenFOAM framework [

45,

46,

47], was utilized for melt flow modeling. The code was ported to a newer version of OpenFOAM and is publicly available in [

48]. The initial CFD validation setup was based on a previous study using directChillFoam, where simulation results were benchmarked against experimental data reported by Vreeman et al. [

49]. The casting material was specified as a binary alloy, Al–6 wt% Cu. Solidification modeling incorporated temperature-dependent melt fraction data derived from CALPHAD routines, while solute redistribution followed the Lever rule [

50]. For thermal modeling, heat transfer coefficients (HTCs) at the mold–melt interface (primary cooling) were locally averaged as a function of solid fraction. Secondary cooling at the billet–water interface was modeled using tabulated HTC values obtained from the correlation proposed in [

51].

Figure 8 illustrates the experimental setup, simulation domain, and melt pool size calculations for horizontal direct-chill casting, including reference lines defined for predicting thermal evolution along the billet.

All snapshot scenarios were simulated for a process runtime of 2,000 seconds—more than twice the duration required to achieve quasi-steady-state conditions. Time-averaged values of temperature and melt fraction over the final 1,000 seconds were recorded at all cell centers, along with their spatial coordinates (X and Z).

5.2. Data Models: Mass Data Generation

The core concept of real-time data models is to move beyond computationally ex-pensive physical and numerical simulations—such as Finite Element or CFD models—toward more efficient data-driven or hybrid approaches capable of delivering fast, real-time predictions under diverse process conditions. This is accomplished by developing reduced-order models that capture complex process phenomena, including thermal evolution and microstructure formation, with significantly lower computational effort. The methodology is built on a structured data strategy, starting with the collection of high-quality, well-balanced data organized into a snapshot matrix, sourced primarily from validated simulations and a limited set of experiments. This data serves as the foundation for training predictive models tailored to casting processes, employing a combination of advanced data solvers, interpolation techniques, and ML components to enhance accuracy and computational efficiency.

The methodology for generating a large training dataset for advanced neural network learning begins with the creation of an initial snapshot matrix comprising ap-proximately 100 process scenarios. These scenarios are selected using balanced sampling techniques such as Latin Hypercube or Sobol sequences to ensure comprehensive coverage of the operational parameter space, including variations in melt temperature, cooling configurations, and casting speed. Each scenario is simulated using calibrated CFD models to produce a small but representative database. From this database, reduced-order models are constructed using decomposition techniques such as SVD combined with interpolation methods like Inverse Distance Weighting (InvD). These approaches extract dominant thermal patterns and compress the data into a low-dimensional space suitable for rapid computation. ML routines—including regression models, neural networks, and symbolic regression—are then applied to improve predictive accuracy, particularly in regions with steep thermal gradients near the melt pool. Once trained and validated, these models are employed to generate a large-scale database of more than 10,000 scenarios for training CVAE systems. This approach re-duces prediction time from over 1,000 seconds to less than a fraction of a second per scenario. Importantly, these models are dynamic; they can generate synthetic data through interpolation and generative modelling techniques, continuously enriching the database for iterative refinement. This capability is essential for improving model robustness under boundary and extreme conditions, where prediction errors are typically higher.

This expansive, high-quality synthetic dataset is subsequently utilized within a CVAE training system to further refine process predictions, with a particular focus on developing robust predictors that accurately capture the underlying process physics across the entire operational window. The ultimate implementation integrates these rapid, high-fidelity data models into the casting process advisory system, enabling operators to achieve accelerated process design and optimization through instant, vali-dated predictions of final thermal and microstructural states.

Figure 9 illustrates the framework for mass data generation using data-driven models, along with a typical initial snapshot matrix.

5.3. CVAE Data Training Framework

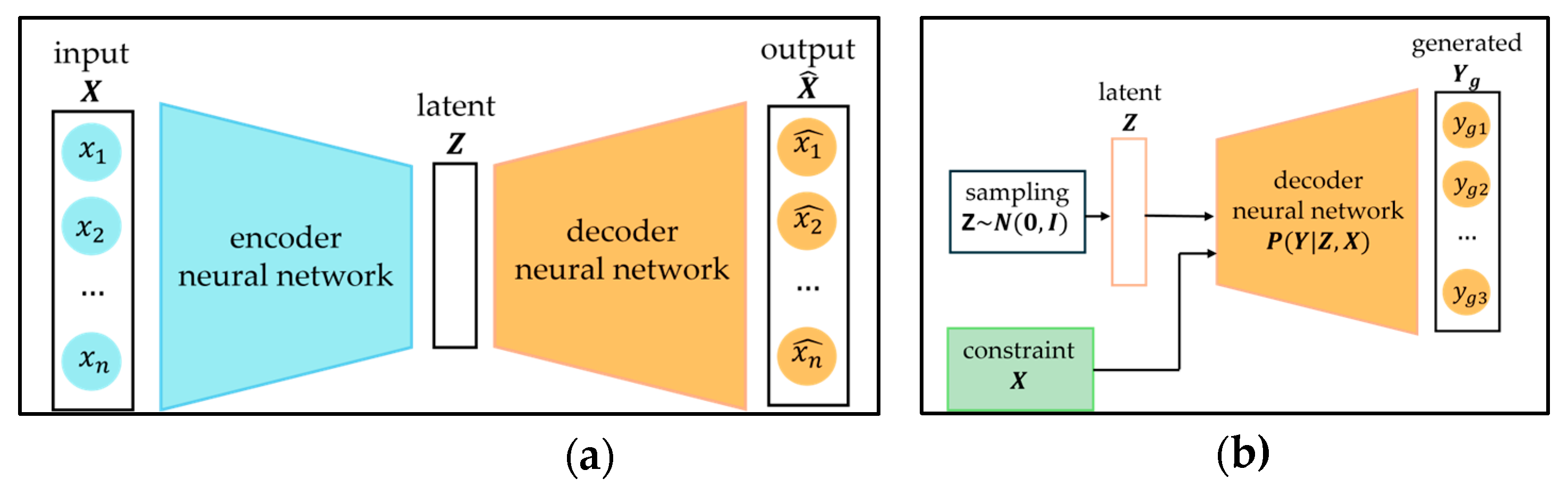

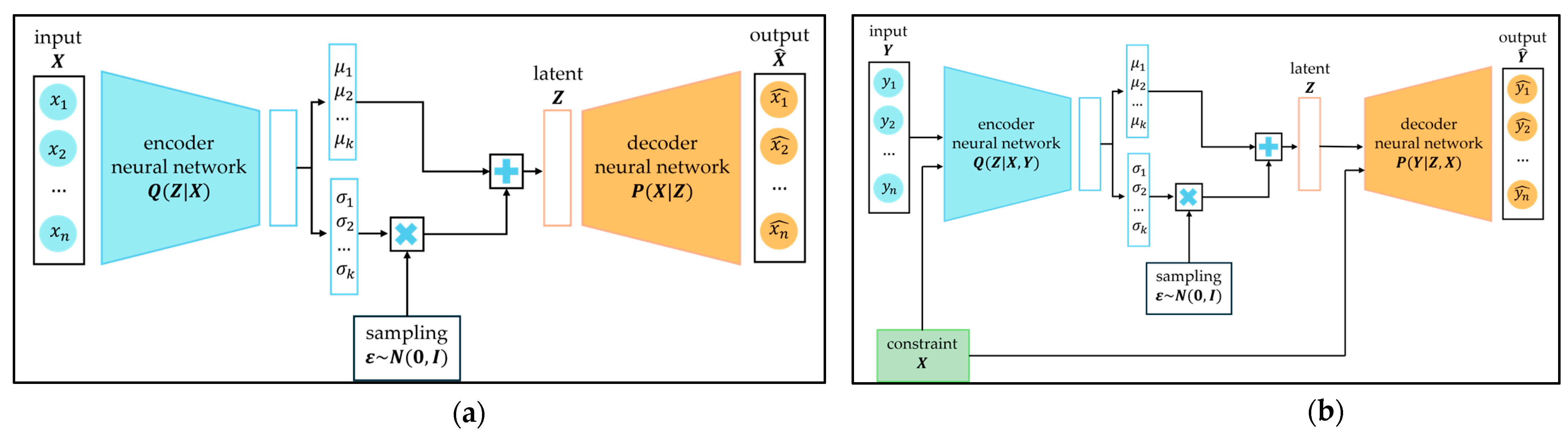

The autoencoder is a well-known neural network architecture. As shown in

Figure 10(a), the high-dimensional input data is first encoded into a lower-dimensional representation, commonly referred to as the latent space representation or bottleneck, while

Figure 10(b) illustrates CVAE generation-phase architecture. Unlike the input data, which correspond to observable or measurable quantities, the latent space is abstract and doesn’t directly correspond to physical variables. This representation is then decoded back into an approximation of the original input. The autoencoder is an unsupervised learning approach, primarily used to learn efficient representations or coding of input data. The model is trained via backpropagation to minimize the reconstruction loss, typically measured using the mean squared error (MSE). Autoencoders are widely applied across various tasks like dimensionality reduction, data compression, anomaly detection etc. Advanced architectures inspired by them like variational autoencoders (VAE), which incorporate probabilistic modelling, learn a latent space distribution, from which they can generate realistic data by sampling. Subsequent variant, CVAE enhance this process by introducing constraints (conditions) that guide the generation. CVAEs are particularly useful for tasks like feature imputation and image inpainting, where they can infer missing or masked parts of input data, by leveraging learned latent space distributions and sampling conditioned on available context (known features or visible parts of an image).

VAEs and CVAEs are generative models primarily designed to generate data. Given data samples , their goal is to learn the underlying distribution . While this can be approximated numerically, knowing the distribution mainly helps estimate how likely certain samples are to belong to the dataset. The real value lies in learning a distribution that supports sampling, enabling the creation of realistic, previously unseen data. This capability is central to generative models and a key reason for their growing popularity, especially with the widespread adoption of AI nowadays.

VAEs were introduced in [

52], with a detailed mathematical derivation, alongside that of CVAEs, provided in [

53]. In VAEs and CVAEs, encoder and decoder neural networks serve as function approximators, with their parameters corresponding to weights and biases. The overall training objective of a VAE is to maximize the probability of each

in the training set, which aligns with the standard maximum likelihood principle. The continuous latent space is modeled using a latent variable

, assumed to follow a standard normal prior distribution. The decoder approximates

and computing

would require marginalizing this function over the entire latent space. However, many latent space realizations contribute very little to this marginalization integral. To address this, the VAE follows an interesting approach of focusing on those

values that are more likely to have produced

, i.e. those for which

is higher. This leads to the core idea of introducing a new function

, approximated by the encoder, which takes a fixed input

and produces a distribution over latent variable’s realizations

that are likely to generate

. Ideally, this distribution concentrates on a smaller, more relevant region of the latent space compared to the original prior. The VAE objective is derived purely from mathematical principles, using Bayes’ rule and Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence, and is expressed as follows:

The left-hand side represents the quantity to be maximized: the probability of a training sample

, while simultaneously minimizing the distribution modeling error expressed through KL divergence. The right-hand side, as discussed in [

53] is of a form that can be optimized using stochastic gradient descent. Noteworthy is that

is modeled as Gaussian distribution, with its mean and diagonal covariance matrix estimated by the encoder network. This diagonal constraint simplifies the KL divergence between two multivariate Gaussian distributions.

The only remaining challenge is that sampling

is part of the architecture, yet sampling itself is non-differentiable, which prevents backpropagation. To overcome this, the reparameterization trick is introduced: sampling is separated from the main architecture by drawing

from standard normal distribution and expressing

. This formulation enables proper gradient flow during training. The complete VAE architecture is illustrated in

Figure 11(a).

The mathematics behind the VAE is easily adapted to the CVAE by conditioning the entire generative process on the input. The main objective becomes maximizing the conditional probability

for each

in the dataset, given its associated condition

, which leads to the following optimization Equation (8). All the principles described for the VAE apply here as well and the architecture is illustrated in

Figure 11(b).

The right-hand side of Equation (8) represents the quantity to be maximized. However, when training neural networks, it’s more common to define a loss function, i.e. a quantity to minimize. By negating this expression, the second term corresponds to the KL divergence between the Gaussian distribution produced by the encoder

and the standard normal prior, with its closed form given in Equation (9), where

represents the dimensionality of the latent space. By estimating mathematical expectation using a single realization (which aligns closely with the concept of stochastic gradient descent) and assuming the decoder distribution follows a Gaussian

, where

denotes the decoder’s reconstruction

, it can be shown that the negative log-likelihood term can be expressed as the Euclidean distance between the input ground-truth sample

and its generated counterpart

under the constraint. This formulation aligns with the standard autoencoder loss function and can be represented as the MSE.

Once the CVAE has been successfully trained, the architecture used during training is no longer needed. The key advantage of a CVAE lies in its ability to generate samples that satisfy a given constraint. During the generation phase, the encoder and the latent space transformations related to the reparameterization trick are omitted. The remaining architecture, shown in

Figure 10(b), draws a latent variable from the standard normal distribution and together with a constraint passes through the decoder. The decoder then produces a generated sample that both satisfies the constraint and resembles samples from the training set. Sampling from just standard normal distribution without applying reparameterization trick might seem confusing, but KL divergence loss’s role (from the Equation (8)) was to move latent’s space distribution as close as possible to standard normal.

5.4. Integration into Advisory System

Whenever new casting molds or alloys are introduced, determining suitable process parameters to ensure smooth casting (avoiding production halts or safety risks) is required. Traditionally, this search involves trial and error and relies entirely on the expertise of experienced personnel. Whether the microstructure in the solidified billets meet the requirements can only be measured between trials, further increasing the needed time and costs. With the advent of digital shadows, the prospect of reducing the number of necessary trials and consequently saving energy and time has led to many advances in this field. In a recent publication [

54], researchers presented their approach to combine FEM simulations with a NN to predict horizontal casting quality parameters for a given set of process parameters. In comparison, the approach presented in our paper allows also for the inverse approach, with a NN (CVAE) able to predict the process parameters needed to achieve a given casting quality, albeit for horizontal casting. In both cases, an advisory system might take advantages of the predictions to assist operators during production. In comparison, the approach presented in our paper allows also for the inverse approach, with a NN (CVAE) able to predict the process parameters needed to achieve a given casting quality, albeit for horizontal casting. In both cases, an advisory system might make use of such predictions to assist operators during production. However, while adding the synthetic results to the exponentially increasing amount of data from live sensors and accumulating historic data theoretically allows for new insights, it also introduces the need for increased human-machine interaction. Modern operators are asked to make decisions based upon a vast amount of information while supervising the real process. Consequently, a well-structured Human-Machine Interface (HMI) is crucial to provide the relevant data in a trustworthy and understandable way.

This poses a significant challenge for the introduction of digital advisory systems [

55]. In the case of horizontal direct chill casting, not all process parameters can be adjusted freely during operation due to temporary physical or operational constraints. Thus, an intelligent real-time decision-support system should address the following challenge: given a scenario where a subset of parameters is fixed, the system should recommend optimal settings for the remaining adjustable ones. These recommendations will be evaluated based on predefined criteria, including process stability, product quality, and real-time applicability. The design for a specific screen of an HMI which was developed together with operators in the research project “opt1mus”is presented in [

56].

Figure 12.

HMI Draft frontend featuring visualization of real-time CVAE data to predict process stability, microstructure and sump depth. Developed for horizontal direct chill casting in course of user-centered design approach in the research project “opt1mus” [

56].

Figure 12.

HMI Draft frontend featuring visualization of real-time CVAE data to predict process stability, microstructure and sump depth. Developed for horizontal direct chill casting in course of user-centered design approach in the research project “opt1mus” [

56].

The user-centered design process has led to multiple screen designs, this example is employing the CVAE to predict the current sump depth and the expected grain size, based on the current parameters. Furthermore, the safe process window is displayed in the upper right corner. For this , the data obtained through mass data generation is subjected to exploratory data analysis and feature engineering, allowing each case to be represented by a set of input process parameters together with derived features - numerical values that carry specific physical meaning. The task of interest can be framed as a feature imputation problem, which is well-suited for solving with a CVAE. Given any scenario where a subset of process parameters is missing or masked, along with all features related to the result, the CVAE should learn to infer and complete them by sampling. Improving the solution lies in enhancing the expressiveness of the data that can be processed by the proposed ML model. One promising idea is a bi-modal data representation, where in addition to physical, tabular features, an image representation of the solidified billet’s microstructure is included. In this image, pixel values correspond to grain sizes, preserving the spatial layout. The image is encoded using a convolutional neural network (CNN), passed through a CVAE alongside the tabular features, and finally decoded using a decoder CNN. Generated images of the sump shape and the microstructure in the solidified billet could then be used as additional information for the operators, giving insights that would otherwise be impossible to provide during the process. The actual implementation of the HMI providing this information in a suitable way requires a through user-centered design approach aiming to develop a positive user experience. User acceptance is crucial for providing a long-term added value in working environments and necessary to maximize the impact of recommendations coming from underlying data models [

57].

6. Performance, Challenges and Limitations

A comprehensive assessment of model performance, predictive accuracy, robust-ness, and validation protocols is essential for establishing the reliability of data-driven advisory systems in manufacturing contexts. Ensuring operational resilience under variable process conditions and compliance with established industrial standards is critical for practical deployment. In this work, advanced computational solvers, high-fidelity interpolation techniques, and neural network-based learning architectures were systematically integrated to develop predictive frameworks with enhanced efficiency. Model optimization was achieved through iterative ML training cycles, implemented both during preliminary development and subsequent refinement phases, to improve computational scalability and predictive precision.

6.1. Analyses and Performance: Data Models

Comprehensive analyses and performance evaluations of data-driven models for casting processes were conducted to assess their predictive accuracy and their capability to generate large-scale datasets for CVAE model training. Initial validation of these models was performed using Design of Experiments (DOE)-based simulation scenarios, encompassing a wide range of process conditions, including nominal, near-boundary, and extreme cases. The preliminary results demonstrate that, while the models exhibit strong potential for process prediction, several technical challenges remain. Casting processes inherently involve complex fluid–thermal–mechanical interactions, and grain evolution during solidification introduces pronounced multiphase phenomena that must be accurately captured to predict the final product characteristics. For example, precise modeling of thermal evolution—including cooling rates, temperature gradients, solidification fronts, and phase transitions—is critical, as these factors govern defect formation and influence microstructural integrity.

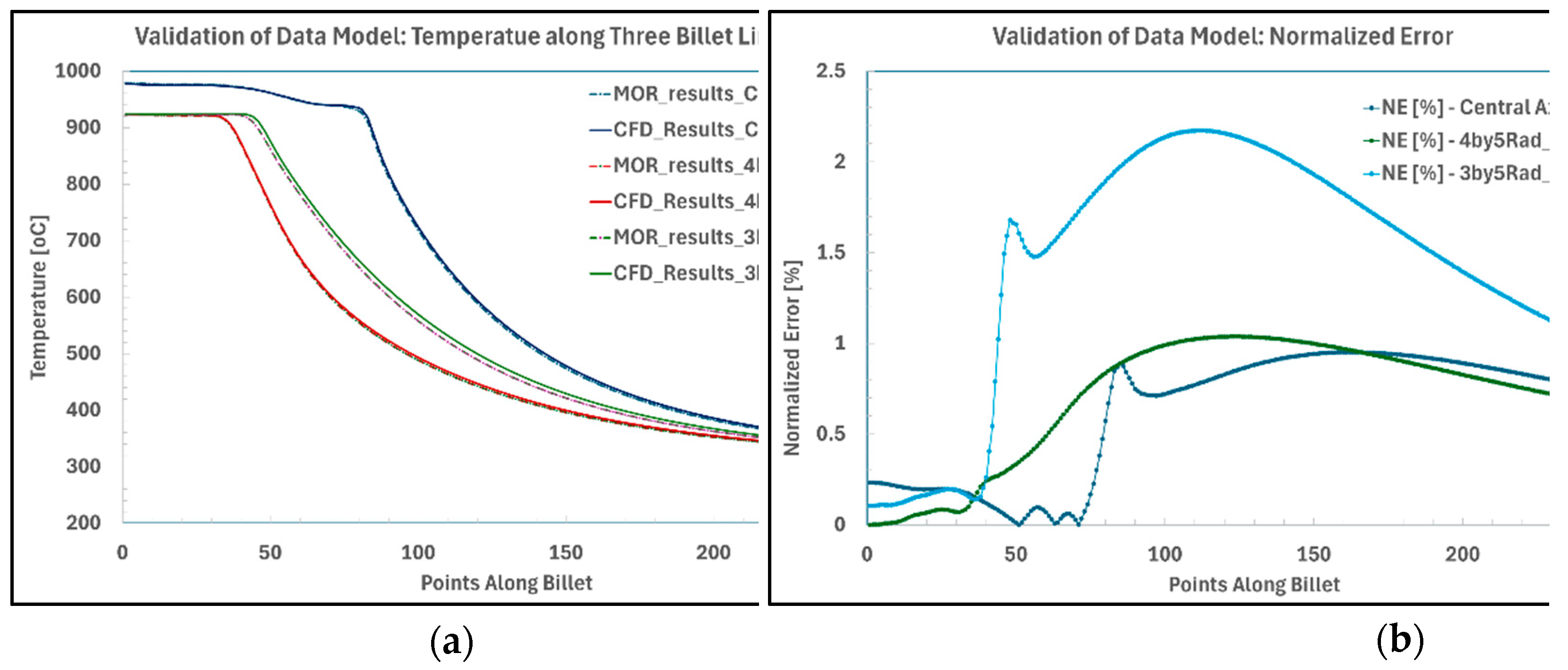

Figure 13 illustrates temperature predictions along three longitudinal lines of a cast billet, comparing CFD-based results with those from the data-driven model, along with normalized error distributions for a near-boundary process scenario. The results indicate that the data model achieves reasonable accuracy in predicting the thermal field, with a maximum normalized error of approximately 2%. Notably, predictions within the melt pool, where temperature gradients are relatively low, exhibit smaller error margins. However, as the analysis approaches the solidification front—characterized by steep thermal gradients—the prediction errors increase significantly (occasionally exceeding 2%), reflecting the model’s difficulty in capturing rapid data variations.

Conversely, the model demonstrates strong performance in fitting initial thermal conditions. The integration of an eigen-based data solver with an inverse-distance interpolation scheme, further enhanced by ML techniques, effectively minimizes errors in these regions. Specifically, error margins at the melt pool surface remain below 0.5%, indicating that the model is well-suited for adhering to process constraints, such as casting machine operational limits.

Predictions related to multi-scale grain evolution during solidification represent a critical aspect of casting process modeling, as microstructural formation significantly influences material properties. In this study, the CFD framework incorporates a meso–macro microstructure module to estimate grain growth based on the evolving thermal field within the melt pool. However, achieving accurate representation of phase transformations and microstructural heterogeneity remains challenging due to limitations in numerical mesh resolution and the computational cost associated with fine-scale discretization. While larger and finer meshes improve fidelity, they impose substantial computational overhead, and integrating lower-scale physical phenomena further complicates the modeling process. Data-driven models, trained on limited datasets, can supplement these simulations by providing surrogate predictions for subsequent CVAE-based training. Nevertheless, because the CFD microstructure module computes grain evolution at discrete nodal points, discontinuities and abrupt variations between neighboring nodes are expected.

Figure 14 illustrates the predicted grain size distribution on a billet cross-section (at the billet end) for both CFD and data-driven models, along with normalized error metrics for the same near-boundary process scenario.

Several key observations can be drawn from the analysis of the results. First, the underlying data exhibits a highly complex pattern characterized by discontinuities and abrupt transitions between adjacent points, which significantly complicates predictive modeling. Second, although the general trend indicates an increase in grain size from the billet center toward the periphery, the variation is non-uniform and irregular. Third, the overall range of grain size variation is relatively narrow—approximately 6.3 to 6.5 μm—suggesting that the spatial resolution of the dataset may be unnecessarily high for practical applications. Nevertheless, accurate thermal field estimation within the CFD framework necessitates the use of a fine computational mesh to capture grain evolution dynamics. An additional challenge arises from the initialization of the predictive model, as the initial estimates for the billet center are inaccurate, leading to difficulties in fitting the model to the stepwise nature of the data. To mitigate this, a moving average filter with a broad kernel (e.g., 50 data points) could be applied to derive a smoothed grain growth profile suitable for engineering applications.

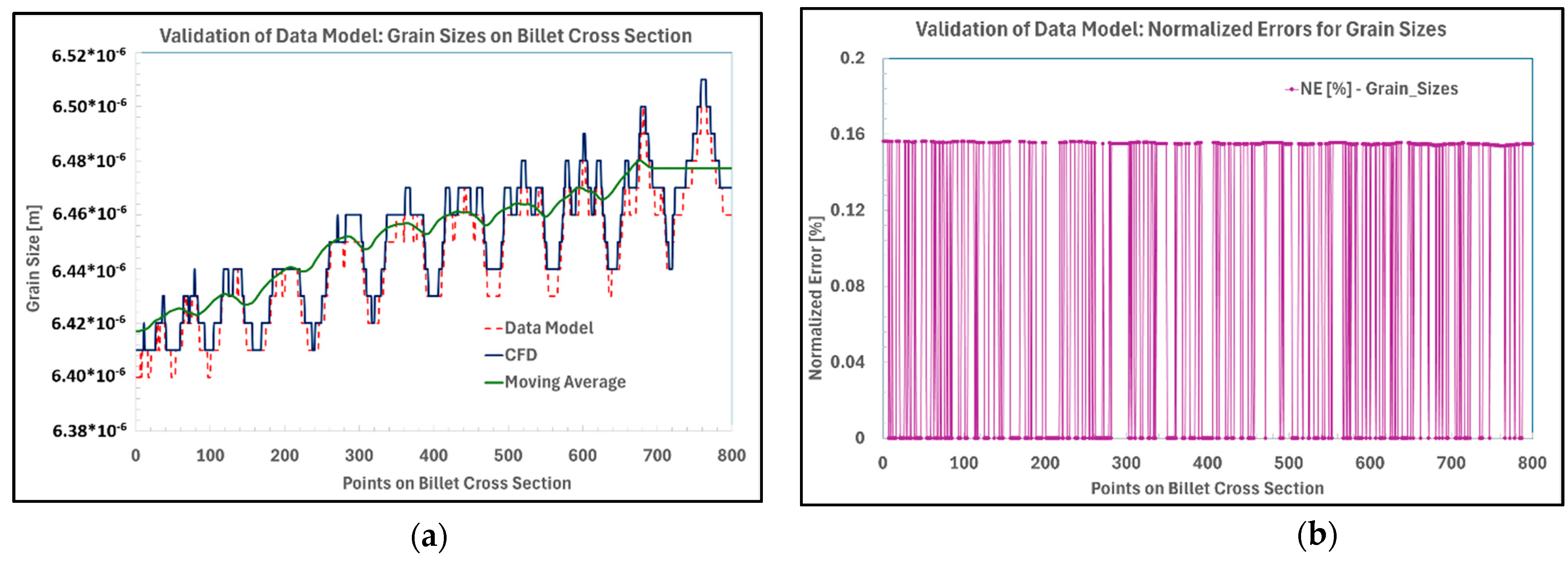

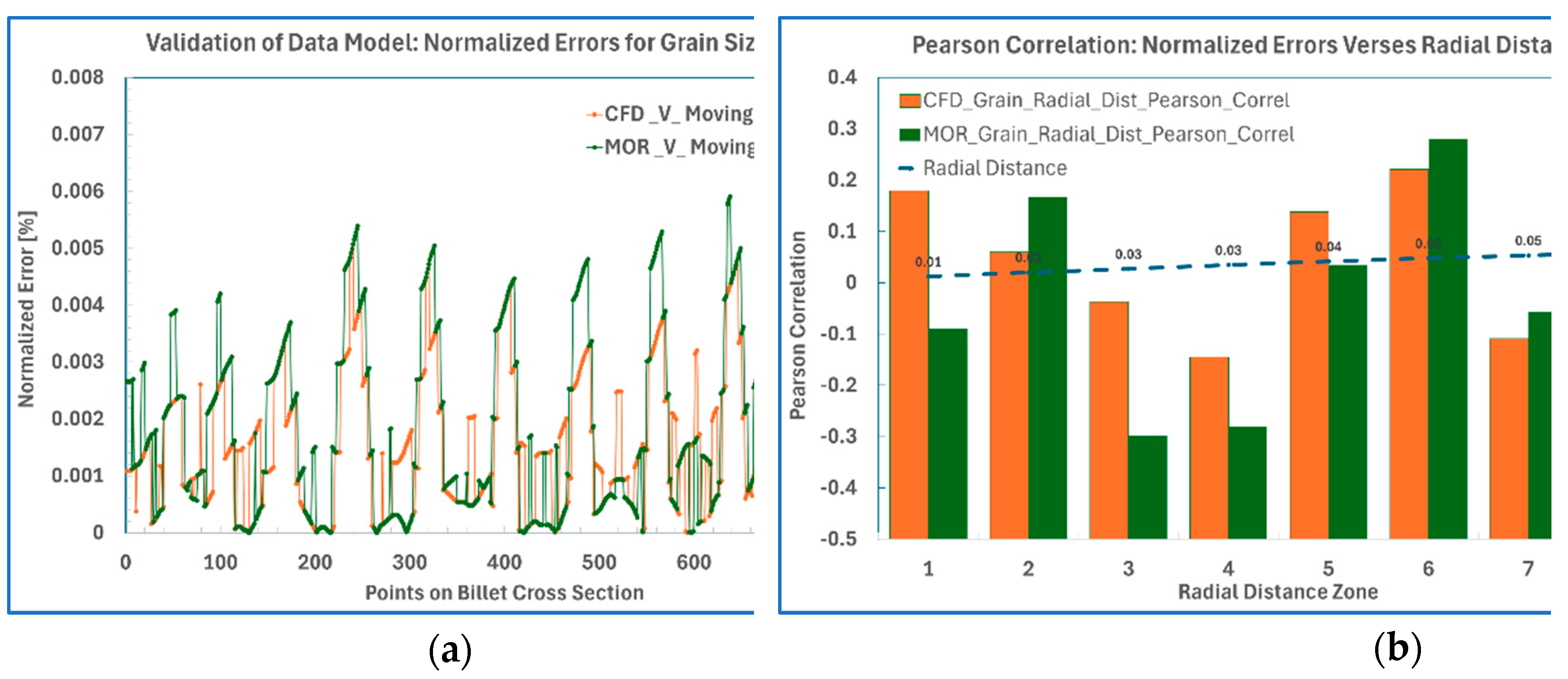

To quantify prediction errors,

Figure 15a presents normalized error distributions for both the CFD simulation and the data-driven model relative to the moving average reference curve.

Figure 15b illustrates the Pearson correlation analysis of these normalized errors as a function of radial position. The results indicate that error distributions for both approaches are spatially uniform, with no significant location-dependent discrepancies. Consequently, the predictive accuracy remains consistent across regions with smaller grain sizes near the billet center and larger grains near the periphery.

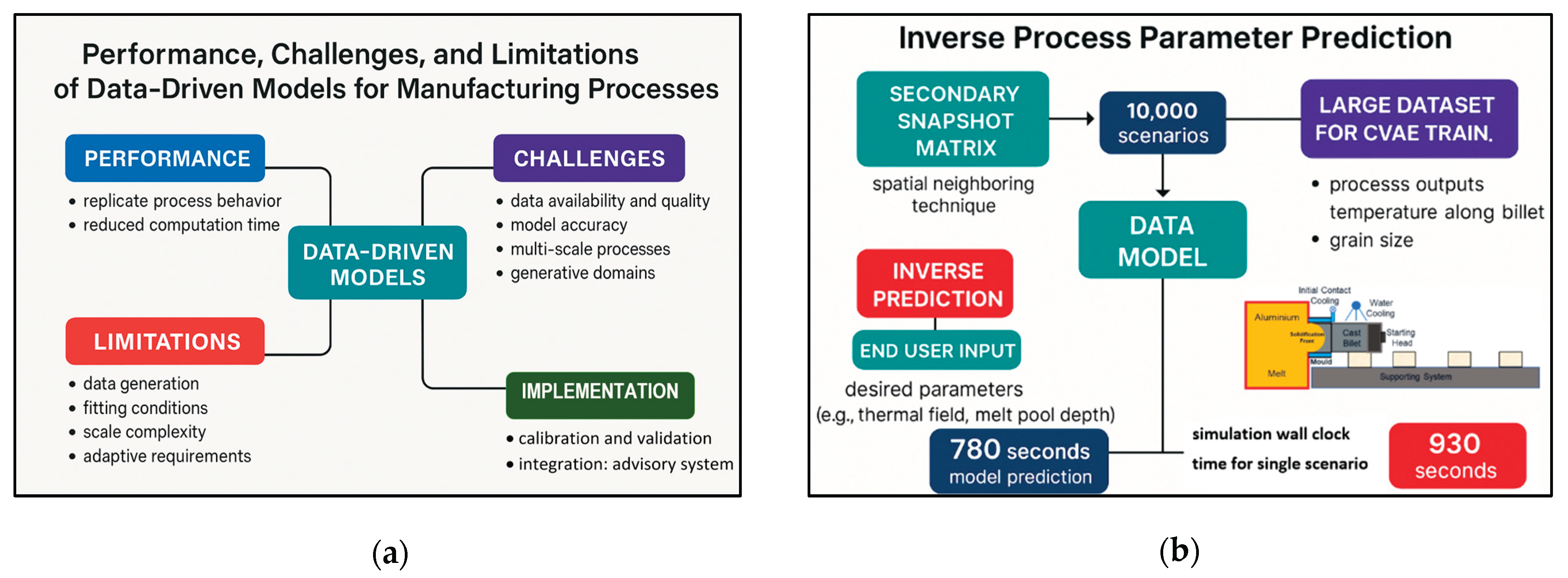

After validating the performance of the data model, an expanded secondary snapshot matrix comprising 10,000 additional process scenarios was generated using a spatial-neighboring technique. This approach enabled the creation of a large dataset for CVAE-based training, supporting inverse process parameter prediction. These inverse predictions allow end users to design and evaluate new processes by specifying desired parameters and obtaining recommendations for complementary conditions to achieve target outcomes—such as thermal field distribution, melt pool depth, and final grain size.

The data model was applied to all 10,000 scenarios to predict temperature profiles along predefined lines on the cast billet and grain sizes across 800 calculation points on the billet cross-section. The entire prediction process required approximately 780 seconds, demonstrating significant computational efficiency compared to conventional CFD simulations, where a single scenario typically requires about 930 seconds to compute thermal and microstructural results.

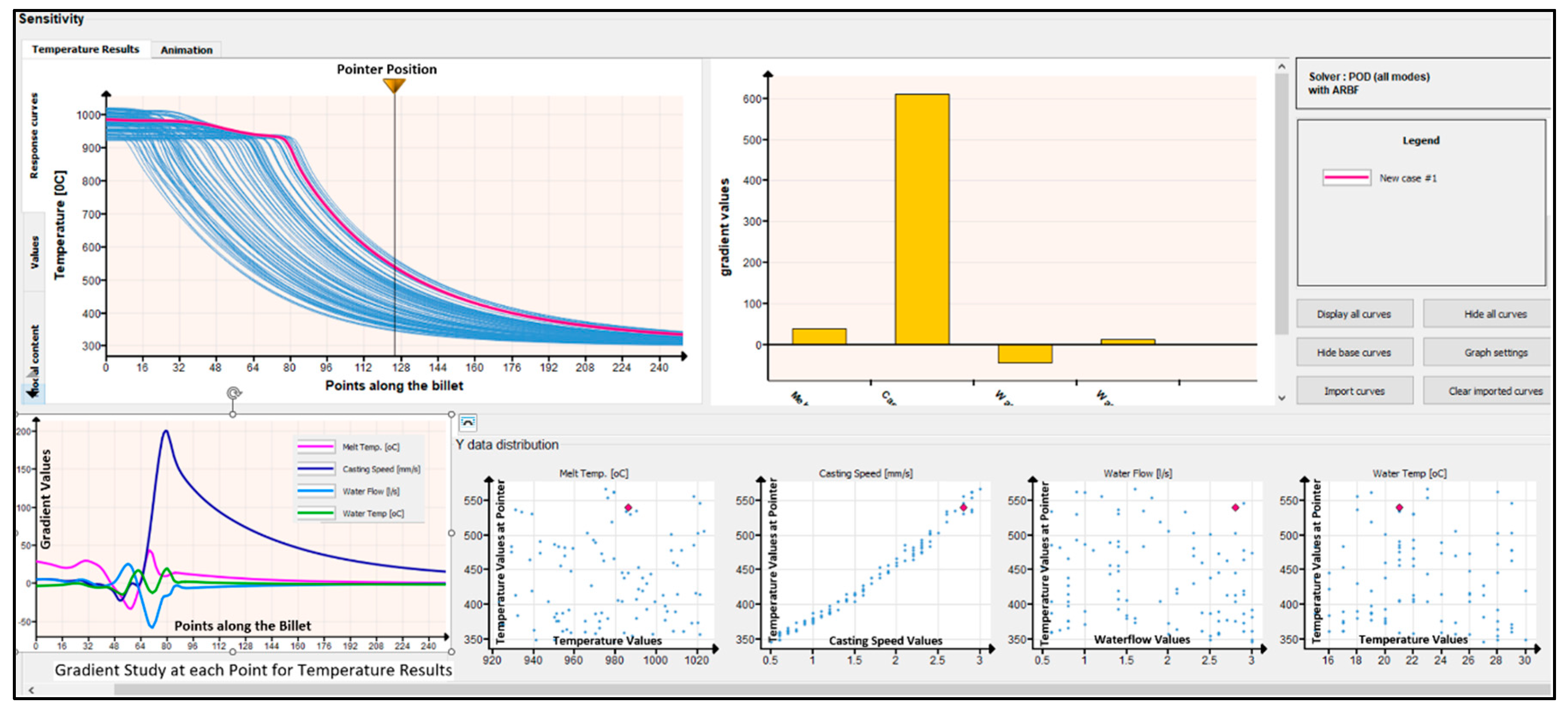

Figure 16 illustrates representative temperature predictions from the data model for selected cases, along with sensitivity analyses, correlation studies, and gradient trends for key process parameters, including melt temperature, casting speed, water cooling rate, and water temperature.

6.2. Analyses and Performance: CVAE Training

All simulated data cases are stored in a PostgreSQL database. It is essential to maintain a clear distinction between different data sources through a dedicated attribute in the results table indicating whether the data originates from CFD simulations, ROM simulations, or real physical measurements. Ideally, the ultimate ground truth should be based on physical measurements collected directly from the continuous casting process. However, such data is expensive to obtain, limited in availability, and often constrained by operational and safety considerations in an industrial environment. As a result, CFD simulations are treated as the reference ground truth, while ROM data offers a favorable balance between physical fidelity and computational cost. ROM generates results almost instantaneously, enabling rapid experimentation and broad parameter exploration. This makes ROM particularly useful for early-stage ML experimentation, data requirement estimation, uncertainty quantification, and advisory strategy testing without the heavy computational burden of CFD. After training the CVAE model on ROM data, it may either be fine-tuned to adapt to the available CFD data or retrained from scratch on an expanded CFD dataset, generated according to estimated data requirements and appropriate sampling strategies.

Extensive exploratory data analysis and feature engineering were carried out to understand the influence of process parameters on the outcomes and to represent each case as a high-dimensional numerical feature vector. This vector includes both input process parameters and derived quantities from raw data, such as melt pool depth, maximum grain size, temperature values along the billet’s central axis and surface (sampled at key positions to capture thermal trends), and various liquid-fraction indicators. The data was split into training, validation, and test sets and normalized using Z-score standardization. As discussed earlier, the advisory task is formulated as a feature imputation problem: given only the available process parameters, the CVAE model imputes missing process and result features through sampling. In practical use, the generated samples are then evaluated based on process stability and product quality criteria.

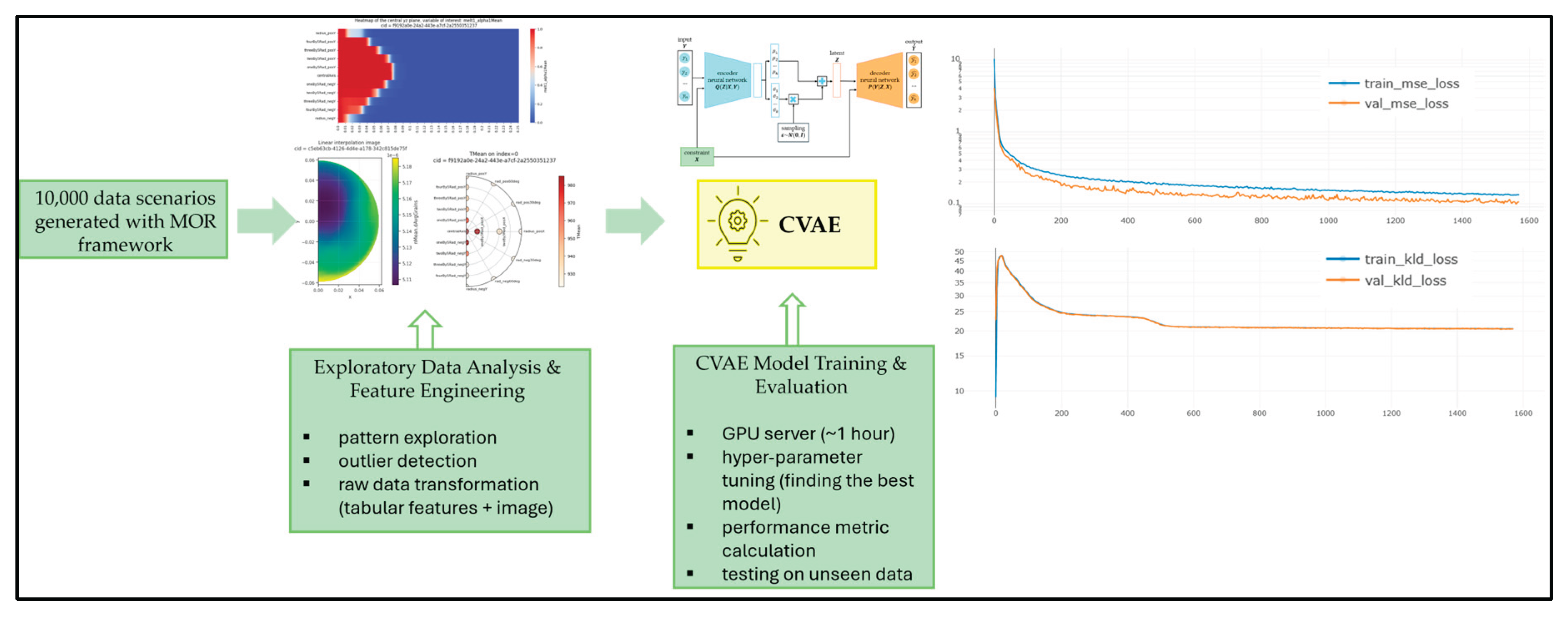

A comprehensive hyperparameter tuning was performed to identify the best performing CVAE on the ROM validation set. The search space covered both architectural and training parameters. Architectural choices included the number of hidden layers in the encoder and decoder, latent space dimensionality, and activation functions. Training parameters such as batch size, learning rate, weight decay, and the use of batch normalization were systematically varied. The objective function used during training is defined as the sum of the KL divergence loss (typically assigned a lower weight) and the MSE loss, as described previously. Early stopping is included to prevent overfitting

Training the best performing model lasted for approximately 1 hour.

Figure 17 shows the explained workflow: from ROM input data, through exploratory data analysis, feature engineering, to model training with hyper-parameter tuning and evaluation. The training and validation loss curves for both the MSE and KL divergence terms are shown on the right. Both curves decrease throughout training, demonstrating stable learning without evidence of overfitting.

In the real-world implementation of the advisory system, the generation-phase CVAE architecture (

Figure 10(b)) is used to generate a specified number of samples for a selected subset of process parameters (constraints). The model internally imputes missing features related to the omitted process parameters and result features, achieving a generation rate of approximately 100 samples per second. Each generated sample is evaluated based on two criteria: process stability and product quality. Process stability is determined using a ML classifier that categorizes samples into good, bleed-out (leakage of molten metal), or freeze-in (early solidification) classes, while also providing class probability estimates. Product quality is assessed based on the billet microstructure, specifically the proportion of the grain size distribution across the billet cross-section that falls within predefined thresholds. Specific features enable this quantitative assessment. Finally, the advisory system recommends the process parameters corresponding to the sample with the highest overall quantitative score (computed as the sum of the two evaluation measures).

6.3. Challenges and Shortcomings

Performance evaluations indicate that data-driven models can effectively replicate the behavior of manufacturing processes while delivering significant reductions in computational time for large-scale data generation compared to conventional numerical simulations. For instance, prediction times were reduced from several minutes to fractions of a second per scenario with minimal compromise in accuracy. Despite these advantages, the development of robust data models faces several challenges, primarily related to data availability, quality, balanced distribution, and the construction of comprehensive database structures. Generating extensive and well-balanced process datasets remains resource-intensive, and inadequate or poorly distributed data can undermine model reliability and generalizability. Additional challenges include ensuring model accuracy and implementing rigorous validation schemes. These issues were addressed through advanced sampling strategies that encompass normal, near-boundary, and extreme process conditions. Efficient sampling techniques such as Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) and Sobol sequences were employed to achieve broad coverage of multi-dimensional parameter spaces while minimizing redundancy. Nevertheless, the complexity of multi-physical and multi-phase manufacturing processes introduces further limitations, which can be categorized as follows:

1. Data Generation: Reliable data models require comprehensive and balanced process databases. Low-volume, inconsistent, or unbalanced datasets often fail to adequately represent the full parameter space, resulting in weak predictive performance and limited generalizability.

2. Fitting to Process Conditions: Manufacturing processes are inherently thermal and often involve rapid heating and cooling rates, transient startup conditions, and nonlinear transitions. Many models struggle to accurately capture these dynamics, particularly during initiation stages or under abrupt changes in process variables.

3. Multi-Scale Process Challenges: Microstructural evolution during solidification spans vast spatial and temporal scales—from micrometers and microseconds to meters and hours. Addressing this complexity requires hierarchical database structures, partitioned data spaces, and advanced data mapping and filtering techniques to preserve fidelity across scales.

4. Generative Numerical Domains: Conventional numerical simulations typically rely on fixed-size discretized domains, which are inadequate for generative processes such as casting, where the billet evolves continuously over time. Data models must therefore incorporate spatial and temporal adaptability, dynamic data integration, and self-updating mechanisms to accommodate evolving process conditions.

To mitigate these challenges, this research adopts efficient data sampling and snapshotting strategies to ensure comprehensive coverage of the process parameter space. Snapshot matrices were constructed to represent the full data domain, and models were developed using eigenvalue-based solvers combined with advanced interpolation schemes to improve accuracy in high-gradient regions. ML routines were integrated to enhance model fitting for transient and initial conditions.

The database architecture was designed to support partitioned spatial domains and temporal scales, incorporating ontological annotations for semantic consistency across datasets. Meso- and macro-scale results—including thermal field predictions and grain size estimations—were systematically managed during database construction and snapshot generation to prevent resolution loss. Further complexities associated with the transient nature of casting processes, such as startup, shutdown, and solidification phases, were addressed through CFD simulations extended to steady-state conditions and time-averaging techniques. Hybrid analytical–numerical models were employed for grain evolution, combining physical principles of solidification with macro-scale thermal field predictions. For data-driven predictions, eigenvalue-based SVD solvers were integrated with InvD and RBF interpolators to capture the generative characteristics of casting processes. These models were further refined through ML-based training to accommodate the high dimensionality and complexity of the process data space.

Figure 18 illustrate a pictorial summary of the challenges, performances and limitations along with the summary of mass data generation for CVAE data training module using the data model.

7. Discussions and Results

The predictions and results presented in the preceding sections provide valuable insights into the performance of data-driven models, the CAVE data training system, and their integration within a process advisory framework, highlighting both capabilities and challenges. The effectiveness of these data science techniques for process design, optimization, and control has been examined, alongside the role of numerical simulations in generating initial datasets. These aspects of manufacturing process digitalization and their implementation can be summarized as follows:

First, the cost and time required to produce high-quality data, construct robust databases, develop efficient data models, and design a training framework such as CVAE are substantial. However, this initial investment is offset by long-term benefits when the advisory system is deployed for process design, parameter optimization, and active control within a digitalized manufacturing environment. Furthermore, the use of advanced data science strategies—such as efficient sampling, snapshotting, and well-balanced low-volume databases distributed across multi-dimensional parameter spaces—can significantly reduce these costs for industrial applications.

Second, managing the inherent complexity of manufacturing processes remains a critical challenge. These processes involve multi-physical, multi-scale, and multi-phase phenomena, requiring data models capable of capturing interactions across expansive temporal and spatial scales. Accurate modeling must account for coupled thermal, fluid, and mechanical fields, as well as phase transitions and solidification dynamics. In particular, microstructural evolution—essential for predicting final product quality—demands high-fidelity data models. To address these requirements, initial datasets were generated using multi-physical numerical simulations, incorporating analytical calculations for meso-scale microstructure evolution. Sophisticated CFD simulations were employed to model coupled fluid and thermal fields during billet casting, and the results were post-processed to create snapshot scenarios. These scenarios were then used to develop efficient data models through a combination of advanced solvers, interpolation schemes, and ML routines. Following comprehensive validation, these models were utilized to generate large-scale datasets for the CVAE training scheme, forming the core of the advisory system.

Third, rigorous validation and performance benchmarking are essential to justify the resources invested in developing these techniques. Limited experimental trials, well-calibrated numerical simulations, and trusted mined data serve as benchmarks for evaluating system reliability. In this research, an extensive performance assessment was conducted within a postgraduate thesis program to evaluate the accuracy and effectiveness of data models, CVAE training, and their integration into the advisory framework.

Overall, the development of these data-driven techniques offers significant potential for advancing process design and improving sustainability, control, and optimization in manufacturing. However, successful integration into industrial digitalization frameworks requires further investigation to address interdependent factors influencing generality, performance, and adaptability under real-world conditions.

8. Summary and Conclusions

This research establishes a comprehensive framework for integrating data generation and processing, database construction, data model development, CVAE-based training, and their deployment within an online advisory system for casting processes. The study underscores the critical importance of data volume, quality, distribution, balance, and availability for the success of predictive systems. It further emphasizes the need for efficient sampling and snapshot techniques, along with the careful selection of data solvers, interpolation methods, and ML algorithms tailored to the specific characteristics of manufacturing processes. For the multi-physical casting scenarios addressed in this work, SVD eigen-based solvers combined with advanced RBF and InvD interpolators demonstrated strong capabilities in capturing complex temporal and spatial dynamics.

Initial process scenarios for the snapshot matrix were generated using advanced sampling strategies to ensure well-distributed coverage across the entire parameter space. The initial database was constructed from verified CFD simulation results corresponding to these scenarios, and the data were post-processed to populate a semantically structured process database. Data models were then developed using combinations of solvers, interpolators, and ML routines based on this database. Validation was performed through DOE-based simulations covering normal, near-boundary, and extreme conditions. After identifying the most effective solver-interpolator combinations, the validated models were employed to generate a large-scale training dataset comprising 10,000 new scenarios using an extended secondary snapshot matrix.

The neural network training system was designed to incorporate process boundary conditions and parameter variations, employing an autoencoder architecture for inverse parameter prediction. Integration of this data-driven system into the online advisory framework was completed with a user-friendly industrial interface. The inherent complexity of casting processes—spanning multi-physical, multi-phase, and multi-scale phenomena—was addressed by modeling interactions across domains and scales, from meso-scale microstructural evolution to macroscopic thermal dynamics. To meet the demands for scalability and adaptability, the system supports heterogeneous data integration and real-time predictions, ensuring accuracy and relevance in dynamic manufacturing environments.

Looking ahead, as data science capabilities continue to expand within manufacturing, the future of digitalization will depend on the successful integration of online advisory systems, digital shadows, and digital twins. Real-world implementation of these technologies requires adaptive, self-updating, and interpretable models capable of evolving alongside manufacturing advancements. Such models must enable both direct real-time predictions for process optimization and inverse predictions for new process design. Although challenges related to data generation, validation, reliability, and performance persist, the mitigation strategies proposed in this work strengthen the development pipeline, paving the way for robust, dual-purpose predictive tools that advance industrial digitalization.

Author Contributions

Amir Horr: conceptualization, methodology, writing-original draft preparation, software (data models), validation, data curation, writing-review, editing, visualization. Sofija Milicic: methodology, investigation, scripting (CVAE), data curation, validation, writing-review, proof reading. David Blacher: conceptualization, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition, proof reading, editing. “All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”.

Funding

This research is financially supported by the Austrian Institute of Technology (AIT) under the UF2025 funding program, and by the Austrian Research Promotion Agency (FFG) through the opt1mus project (FFG No. 899054).

Data Availability Statement

The sharing of raw-data required to reproduce the case studies are considered upon request by readers.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the technical and financial support provided by the Austrian Federal Ministry for Innovation, Mobility and Infrastructure, the Federal State of Upper Austria, and the Austrian Institute of Technology (AIT). Special thanks are extended to Rodrigo Gómez Vázquez, Manuel Hofbauer, Christian Bechinie (creator of HMI Design, Figure 12) and Dr. Johannes Kronsteiner for their valuable contributions to this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Batwara, A., Kayande, R.A. & Kediya, S. Critical Drivers of AI Integration in Industrial Processes for Enhancing Smart Sustainable Manufacturing: Decision-Making Framework. Process Integr. Optim. Sustain., 2025, 9, . [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S., Bacanin, N. Artificial intelligence in advanced manufacturing. Int. J. Comp. Integ. Manuf., 2024, 37(4), . [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-C.; Chien, C.-H. Machine Learning for Industrial Optimization and Predictive Control: A Patent-Based Perspective with a Focus on Taiwan’s High-Tech Manufacturing. Processes 2025, 13, 2256. [CrossRef]

- Okuyelu O., Adaji O. AI-Driven Real-Time Quality Monitoring and Process Optimization for Enhanced Manufacturing Performance, J. Adv. in Math. and Comp. Sci. 2024, 39 (4), . [CrossRef]

- Horr A. M., Notes on New Physical & Hybrid Modelling Trends for Material Process Simulations; J. of Phy. conference Series, 2020, Vol. 1603, 012008, . [CrossRef]

- Slam, M.T.; Sepanloo, K.; Woo, S.; Woo, S.H.; Son, Y.-J. A Review of the Industry 4.0 to 5.0 Transition: Exploring the Intersection, Challenges, and Opportunities of Technology and Human–Machine Collaboration. Machines 2025, 13, 267. [CrossRef]

- Colombathanthri, A., Jomaa, W. & Chinniah, Y.A. Human-centered cyber-physical systems in manufacturing industry: a systematic search and review. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 2025, 136, . [CrossRef]

- Lou S., Hu Z., Zhang Y., Feng Y., Zhou M. and Lv C. Human-Cyber-Physical System for Industry 5.0: A Review From a Human-Centric Perspective, in IEEE Transactions on Automation Science and Engineering, 2025, 22, . [CrossRef]

- Oks, S.J., Jalowski, M., Lechner, M. et al. Cyber-Physical Systems in the Context of Industry 4.0: A Review, Categorization and Outlook. Inf Syst Front 2024, 26, . [CrossRef]

- Katherine van-Lopik, Steven Hayward, Rebecca Grant, Laura McGirr, Paul Goodall, Yan Jin, Mark Price, Andrew A. West, Paul P. Conway, A review of design frameworks for human-cyber-physical systems moving from industry 4 to 5, IET Cyber-Physical Systems: Theory & Applications 2023, . [CrossRef]

- Rishabh Sharma, Himanshu Gupta, Leveraging cognitive digital twins in industry 5.0 for achieving sustainable development goal 9: An exploration of inclusive and sustainable industrialization strategies, J. Cleaner Prod., 2024, 448, . [CrossRef]

- Tommy Langen, A Literature Review of Conceptual Modeling for Human Systems Integration in Manned-Unmanned Systems, Systems Engineering 2025, . [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.S., et al.: Smart manufacturing: past research, present findings, and future directions. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. Green Technol 2016, 3(1), . [CrossRef]

- Krugh, M., Mears, L.: A complementary cyber-human systems framework for industry 4.0 cyber-physical systems. Manuf. Lett. 2018, 15, . [CrossRef]

- Van-Lopik, K. Considerations for the design of next-generation interfaces to support human workers in Industry 4.0, Doctoral Thesis, Loughborough University, 2019, . [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, E.Y., et al.: Industry 4.0 reference architectures: state of the art and future trends. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 156, 107241 . [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, R., et al.: An industrial evaluation of an Industry 4.0 reference architecture demonstrating the need for the inclusion of security and human components. Comput. Ind. 2019, 108, . [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H., Ganix, N., Ion, L.: Human - centred design in industry 4. 0: case study review and opportunities for future research. J. Intell. Manuf. 2022, 33 . [CrossRef]

- Moghaddam, M., et al.: Reference architectures for smart manufacturing: a critical review. J. Manuf. Syst. 2018, 49, . [CrossRef]

- Zong, Z., Guan, Y. AI-Driven Intelligent Data Analytics and Predictive Analysis in Industry 4.0: Transforming Knowledge, Innovation, and Efficiency. J Knowl Econ 2025, 16, . [CrossRef]

- Çınar, Z.M.; Abdussalam Nuhu, A.; Zeeshan, Q.; Korhan, O.; Asmael, M.; Safaei, B. Machine Learning in Predictive Maintenance towards Sustainable Smart Manufacturing in Industry 4.0. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8211. [CrossRef]

- Salierno, G.; Leonardi, L.; Cabri, G. Generative AI and Large Language Models in Industry 5.0: Shaping Smarter Sustainable Cities. Encyclopedia 2025, 5, 30. [CrossRef]

- Horr, A., Blacher, D. & Gómez Vázquez, On Performance of Data Models and Machine Learning Routines for Simulations of Casting Processes, R., 8 Jan 2025, BHM Berg- und Hüttenmännische Monatshefte. 2025, . [CrossRef]

- Horr, A.M., Real-Time Modeling for Design and Control of Material Additive Manufacturing Processes. Metals 2024, 14, 1273. [CrossRef]

- Wang J., Li Y., Gao R. X., Zhang F., Hybrid physics-based and data-driven models for smart manufacturing: Modelling, simulation, and explainability, J. of Manuf. Sys. 2022, 63, . [CrossRef]

- Sumit K. Bishnu, Sabla Y. Alnouri, Dhabia M. Al-Mohannadi, Computational applications using data driven modeling in process Systems: A review, Digital Chemical Engineering 2023, 8, 100111, . [CrossRef]