1. Introduction

Acute respiratory infections (ARIs) remain one of the leading causes of hospitalization and death among children under five, especially in low- and middle-income countries [

1,

2]. Among the most common viral culprits are respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), influenza A and B, and SARS-CoV-2, all of which contribute significantly to this burden [

1,

3]. RSV, in particular, is known for causing severe lower respiratory tract infections (LRTIs) in infants and toddlers, often requiring emergency care or hospitalization that requires oxygen support [

4,

5].

In Africa, RSV plays a major role in the burden of LRTIs among children under five [

2]. Its impact on child mortality and morbidity is further fueled by the high prevalence of HIV among pediatric populations, which increases vulnerability to severe RSV infections [

2]. Economic challenges across the continent also compound the issue, limiting access to timely diagnosis and treatment and placing additional strain on families and healthcare systems [

6,

7].

In Ethiopia, ARIs remain a major public health concern. A recent case–control study in Addis Ababa found RSV A, RSV B, and influenza viruses significantly associated with LRTIs in children under five, with RSV showing the highest attributable fraction [

8,

9]. Despite this, the burden in children under two is underreported, and surveillance data are fragmented. Except for one study, most of these studies used CDC multiplex RT-PCR for diagnosing respiratory viruses, and sample testing was performed only at specialized referral centers [

10,

11].

This centralized, molecular-based approach creates a diagnostic gap at the point of care, especially in emergency departments, where timely decisions are critical [

12]. Rapid antigen-based multiplex tests offer a practical alternative: they are portable, easy to use, and require no specialized equipment. Their use in pediatric emergency settings could improve clinical decision-making, reduce unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions, and help curb antimicrobial resistance [

13,

14].

Respiratory viral co-infections are commonly observed in pediatric populations and are associated with an increased risk of severe outcomes [

15], including hospitalization and mortality, while also complicating clinical diagnosis. In Ethiopia, high seasonal circulation of respiratory viruses such as RSV and influenza has been reported among children under five, with a significant proportion of co-infections identified through multiplex rRT-PCR assays [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Additionally, infections with SARS-CoV-2, influenza, and RSV often present with similar symptoms [

16]. This makes clinical differentiation challenging. This is especially true in resource-limited pediatric and emergency settings. In such settings, having access to validated multiplex rapid antigen detection tests that can identify and distinguish multiple respiratory viruses quickly is essential for making informed clinical decisions in tertiary care.

Although rRT-PCR-based point-of-care tests (POCTs) offer superior sensitivity and specificity [

16,

17,

18], their use in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) is limited due to the need for specialized equipment, trained personnel, and higher per-test costs. In contrast, lateral-flow rapid antigen tests are more practical for emergency departments and intensive care units in LMICs, as they are affordable, easy to use, and provide visually interpretable results in under 20 minutes. Importantly, antigen-based multiplex or combo rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) that detect multiple respiratory pathogens from a single specimen can accelerate decisions regarding antiviral therapy, isolation protocols, and reduce unnecessary antibiotic use—ultimately improving targeted treatment [

19,

20]. These tests may also reduce the need for additional diagnostic procedures, including invasive and costly investigations such as chest radiography [

20].

In this study, we evaluated the diagnostic performance of the MobiLab SARS-CoV-2, Flu A/B, and RSV Antigen Combo RDT, an immunochromatographic assay designed to detect and differentiate these viruses from a single nasopharyngeal sample. We analyzed 470 nasopharyngeal swabs (NPS) from hospitalized pediatric patients with suspected respiratory infections. Sensitivity, specificity, and clinical utility were assessed using the Allplex™ Respiratory Panel 1 multiplex RT-qPCR as the reference standard. We also examined correlations with viral load (Ct values) and evaluated the test’s point-of-care utility in resource-limited hospital settings.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Period, and Setting

This was a hospital-based cross-sectional study conducted at three government referral hospitals (ALERT Hospital, Yekatit 12 Hospital, and Zewditu Memorial Hospital), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, between January 2024 and September 2025. The study was designed to evaluate the diagnostic sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, Positive Predictive Value (PPV), Negative Predictive Value (NPV) and concordance of the SARS-CoV-2, Influenza A/B and RSV Antigen Combo RDT (MobiLab Medical Innovatives, San Diego, USA), hereinafter referred to as the ML Ag combo RDT against the Allplex™ Respiratory Panel 1 (Flu / RSV / Flu A subtyping) (Seegene Inc., Seoul, South Korea), a reference standard, in line with US FDA diagnostic evaluation guidelines [

21,

22]. The reference assay, hereinafter referred to as the Allplex RT-qPCR.

2.2. Ethical Consideration

The study received approval from the AHRI/ALERT Ethical Review Committee (Protocol number: PO/037/24).

2.3. Collection of Clinical Samples and Data

As proper sampling collection can have an effect on the quality of the specimen and thereby the accuracy of testing results, nurses and physicians selected as collectors received an hour of training on NPS collection from children and were provided with a video. NPS were collected twice from each participant by admitting nurses or pediatricians using sterile flocked swabs. One swab was placed in a dry tube for POCT using the ML Ag Combo RDT. The second swab was placed in viral transport medium (VTM), frozen at −20 °C at the study hospital, and transported in a cold box to the Armauer Hansen Research Institute (AHRI) within two weeks. Upon arrival, samples were stored at −80 °C until molecular testing was performed using Allplex rRT-qPCR.

Clinical and demographic data were collected through structured interviews with parents or guardians, conducted by trained nurses or physicians. Data were entered into REDCap, a secure web-based platform for research data management.

2.4. Clinical Specimens Testing by Allplex Multiplex rRT-qPCR

2.4.1. RNA Extraction

Viral RNA was extracted from a total of 474 nasopharyngeal swabs (NPS) specimens, which had been collected in a VTM and stored at - 20 °C prior to processing. An automated RNA extraction from each specimen was performed on the Bioer NPA-32P extraction instrument (Hangzhou Bioer Technology, China) using the MagaBio plus virus RNA extraction Kit II (Cat No. BSC87S1E, Hangzhou, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, with 300 μL starting volume and 70 μL final eluted RNA volume. All RNA samples (n= 474) were then tested using rRT-qPCR in a pool of eight RNA samples for the presence of RSV and Flu.

2.4.2. Pooled RNA Samples Testing

We used pooled RNA samples for testing because of the cost and shortage of the Allplex rRT-qPCR assay. We assessed the sensitivity of pooled RNAs by mixing one known positive RNA sample with a high Ct value with seven RNA samples, each confirmed negative by rRT-qPCR. The pooled RNA was adjusted by adding more positives and fewer negatives until a pool of four positives and four negatives was achieved. This resulted in four pooled RNA samples, and we then tested them by rRT-qPCR per the manufacturer's procedures. The testing results showed that the positivity of pooled RNA remained unaffected by the number of negative samples or higher Ct values (

Table S1). This experiment suggests that our RNA pooling strategy did not reduce detection sensitivity with Allplex rRT-qPCR, even at low viral loads. After this validation, all RNA samples (n = 474) were tested by rRT-qPCR in pools of up to eight RNA samples. If the pooled RNA sample tested positive, each RNA sample in the pool was then tested individually. If it tested negative, each sample in the pool was recorded as negative.

2.4.3. rRT- qPCR Assay

Viral detection was performed using Allplex rRT-qPCR according to the manufacturer’s instructions. This assay is a multiplex real-time one-step RT-PCR assay that permits simultaneous amplification and detection of target nucleic acids of Flu A, Flu B, RSV A, RSV B, and subtyping Flu A (Flu A-H1, Flu A-H3, Flu A-H1pdm09), and Internal Control (IC), following the manufacturer's instructions.

Briefly, 8 µL of the extracted RNA(s) was combined with 17 µL of the Allplex™ reaction master mix for quantitative multiple amplification, yielding a final reaction volume of 25 µL. Amplification and fluorescence detection were performed using the CFX96TM Real-time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) under the following thermal cycling conditions: 1 cycle of reverse transcription at 50°C for 20 minutes and, initial denaturation at 95°C for 15 minutes, succeeded by 45 amplification cycles of 95°C for 10 seconds, 60°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 10 seconds. The assay includes an exogenous internal control to monitor sample integrity and amplification efficiency.

2.4.4. rRT-qPCR Analysis

Upon completion of the amplification run, CFX96TM Dx v 3.1 was used to export the data to Seegene Viewer software (Seegene Inc., South Korea) for interpretation and data analysis that applies predefined algorithms to assess curve morphology and signal strength, ensuring consistency across runs. Accordingly, a positive test result for Flu A, Flu B, RSV A, and RSV B was recorded when a clear exponential fluorescence curve crossed the Ct at or before 42 cycles. A negative test result was recorded when no amplification curve for the pathogen’s target genes crossed the threshold line, and the internal control was successfully amplified (

Figure S1). Testing quality was assured by the inclusion of an exogenous internal control. The test result was recorded as invalid when neither the target genes nor the internal control was amplified. When invalid tests occurred, retesting was performed using a new RNA extraction from another aliquot of the original specimen to rule out technical failure during extraction or amplification. Positive results were classified into different categories based on the cycles of threshold (Ct) values to evaluate whether the sensitivity of the ML Ag Combo Rapid Test correlates with the Ct. The Ct values of rRT-qPCR are inversely proportional to the viral load; thus, a lower Ct value indicates a higher viral load.

2.5. Retesting of Samples with Invalid Allplex rRT-qPCR Results

During Allplex rRT-qPCR testing, we observed that samples (n = 11) placed in the peripheral wells of 96-well plates yielded invalid results. We suspected edge effect due to evaporation and retested them in interior wells. Remarkably, 10 of the 11 samples produced valid results upon retesting, and all but one were subsequently confirmed as positive. For a sample that continued to produce invalid results, we performed a fresh RNA extraction from the original specimen and repeated the assay using an interior well. Despite these efforts, the result remained invalid. We suspect that PCR inhibitors may have been present in this sample, interfering with amplification.

Our observations indicate that edge effects (possibly due to evaporation) may have contributed to the initial invalid results seen in RNA samples placed in edge wells. Based on this experience, we recommend that a sample yielding an invalid result in the edge well needs to be retested.

2.6. Clinical Specimens Testing by the ML Ag Combo Test

A total of 476 NPS specimens were evaluated using the ML Ag combo Rapid Test, a lateral-flow immunochromatographic assay for the qualitative detection and differentiation of RSV, Flu A, Flu B, and SARS-CoV-2 antigens in upper-respiratory specimens. Specifically, the assay targets the nucleoprotein (NP) antigen specific to Influenza A virus, the NP antigen specific to Influenza B virus, the nucleocapsid (N) protein of SARS-CoV-2, and both the fusion (F) protein and NP antigens specific to RSV.

Testing was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, each NPS was inserted into the extraction tube containing approximately 500 µL of extraction buffer, rotated at least 10 times while pressing against the tube wall to release viral antigens, and then removed while squeezing the swab to recover as much liquid as possible. Three drops (≈ 60 µL) of the processed sample were dispensed into the sample well of the test cassette.

The assay was run at room temperature (15–30 °C), and the results were visually interpreted after 15 minutes (not later than 20 minutes). The presence of a colored band in the control (C) region confirmed test validity. A colored line in the designated region for RSV (T), Flu A (A), Flu B (B), or SARS-CoV-2 (T) indicated a positive result for that pathogen. In contrast, the absence of any test line with a visible control line was considered negative. All tests were performed and interpreted independently by two authors (B.M. and D.F.) using unaided visual inspection. In cases of discordant interpretation, a third author (T.G.) served as the adjudicator.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

To assess the diagnostic agreement between the ML Ag combo test and the Allplex rRT-qPCR, two-by-two contingency tables were constructed for each target pathogen. From these, sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, PPV, and NPV were calculated, along with their corresponding two-sided 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Cohen’s kappa coefficient (κ) was computed to quantify the overall consistency of the diagnostic performance of the ML Ag Combo RDT beyond chance. Values between 0.0 and 0.20 were considered poor, values between 0.21 and 0.40 were considered fair, values between 0.41 and 0.60 were considered moderate, values between 0.61 and 0.80 were considered strong, and values between 0.81 and 1.00 were considered nearly perfect [

21]. Additionally, the area under the curve (AUC) for the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was done. Its interpretation is classified as follows: unsatisfactory if AUC <0.7, acceptable if 0.7 ≤ AUC <0.8, excellent if 0.8 ≤ AUC <0.9, and outstanding if AUC ≥0.9 [

24].

More so, for specimens that tested positive by the Allplex rRT-qPCR, the correlation between Ct values and the qualitative results of the ML Ag combo test was evaluated using Cohen’s kappa coefficient. All statistical analyses and visualizations were performed in Python (version 3) with pandas, scikit-learn, and matplotlib libraries, with a significance threshold set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

A total of 492 children with respiratory symptoms were recruited for this study, and clinicians collected NPS specimens. However, 16 children were excluded from the evaluation due to missing data. The median age of the qualified children (n = 476) was 9 months (IQR: 4-15 months). The majority of these (59.03%) children were male. All of them were hospitalized and symptomatic with respiratory illness.

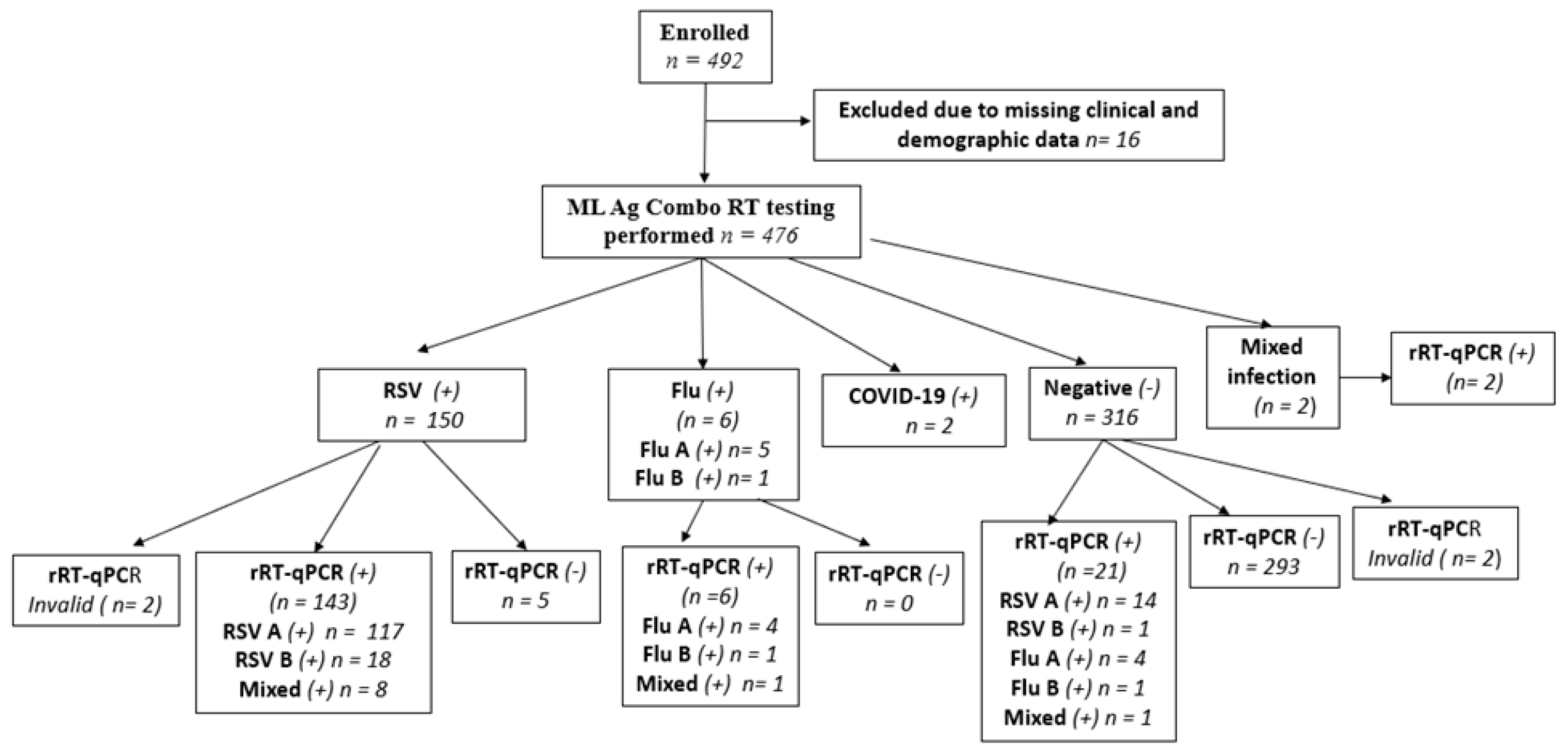

Of the 476 NPS specimens tested using the ML Ag-Combo RDT, 150 tested positive for RSV, six tested positive for flu, two tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, and two had a mixed infection of RSV and SARS-CoV-2. The remaining 316 samples tested negative for all three targeted viruses. Of the 150 RSV-positive samples, 145 were confirmed by rRT-qPCR (κ = 0.90). Meanwhile, 21 out of 316 RDT negatives tested positive by rRT-PCR.

As shown in

Figure 1, of the 492 NPs, 16 were excluded due to missing data, and 2 were excluded because Allplex rRT-qPCR does not detect SARS-CoV-2. An additional 4 NPs samples were excluded because they yielded invalid rRT-qPCR test results. This left 470 NPs for ML Ag Combo RDT performance evaluation. Additionally,

Figure 1 provides a visual summary of the workflow from recruitment to the final cohort for performance analysis, while

Table S2 summarizes the two-by two table test results by both assays and utilized for performance analysis.

3.1. Mixed Infections

The Allplex rRT-qPCR assay identified ten cases (n = 10) of mixed infections among the 470 NPS included for ML Ag Combo RDT performance evaluation. Nine of these cases were identified as mixed infections with RSV and influenza A, while the remaining one was identified as a mixed infection with Flu A and Flu B. This finding aligns with the relative predominance of the two viruses in our cohort of hospitalized pediatric patients, where RSV was found to be predominant (~34%), followed by Flu (4.4%). Among these mixed infections, the ML Ag Combo RDT classified eight cases as RSV mono-infections, while one case was identified as negative (

Figure S1 and

Figure S2).

Confirmation of the two samples that had mixed infection with RSV and SARS-CoV-2 by RDT was not possible, as the Allplex™ panel did not include primers and probes for SARS-CoV-2 detection. Nevertheless, both cases were confirmed as RSV-positive by Allplex rRT-qPCR.

3.2. Clinical Performance of the ML Ag Como Rapid Test Using Allplex rRT-qPCR as a Reference

3.2.1. ML Ag Combo RDT Sensitivity Depending on the Ct Values

As expected, the ML Ag Combo RDT demonstrated 100% sensitivity in NPs samples with Ct values below 20 for RSV and Flu A. It also showed high sensitivity at Ct values below 25, with 96.9% specificity for RSV and 100% specificity for Flu A. However, at Ct values below 42, its sensitivity decreased to 90.1% for RSV and 71.4 % for Flu A/B (

Table 1).

3.2.2. ML Ag Combo RDT Sensitivity Depending on the Ct Values

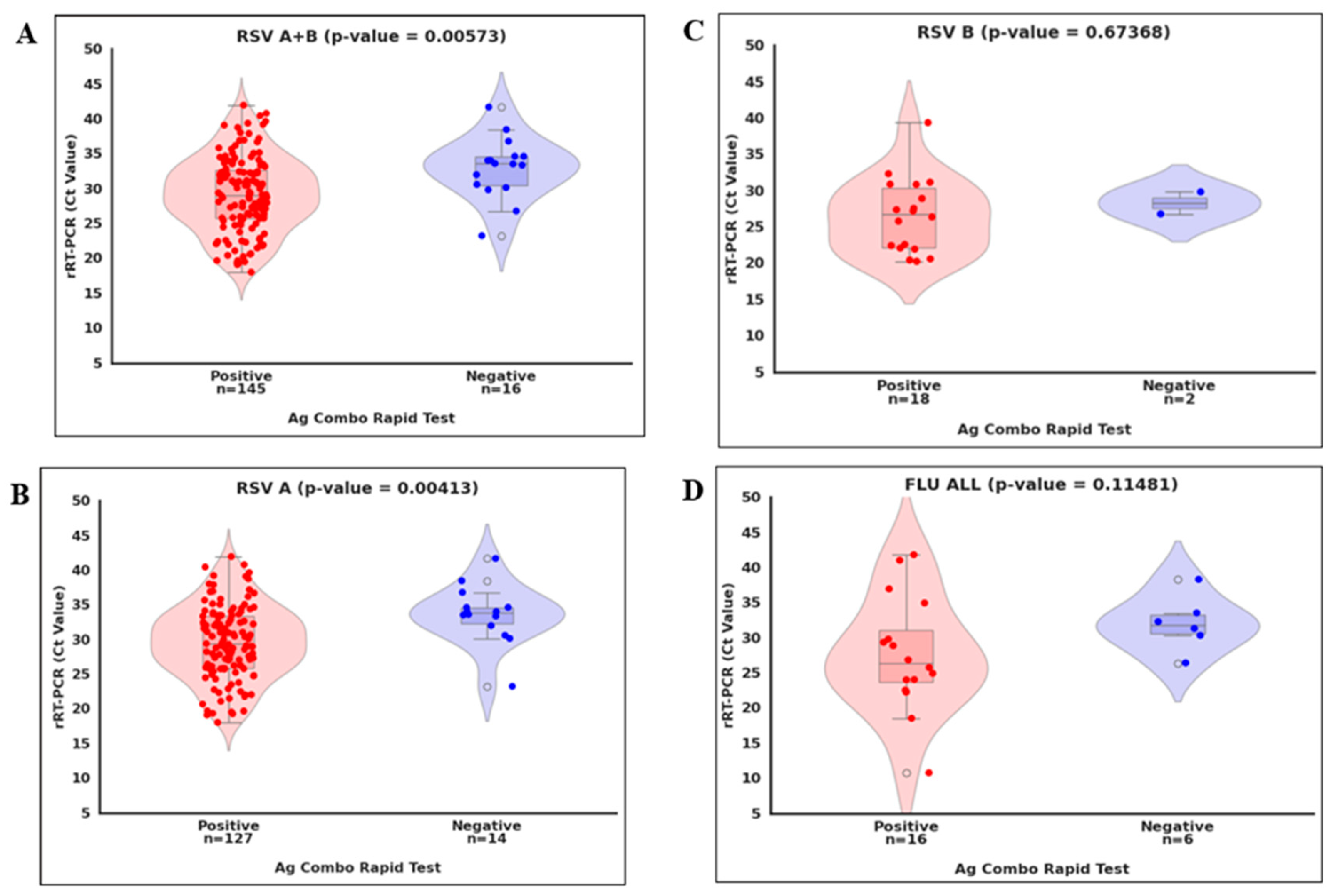

As shown in

Figure 2, we compared viral loads (Ct values) by categorizing RT-PCR-positive samples into two groups: concordant (positive by the ML Ag Combo RDT) and discordant (negative). We also compared the viral load difference between concordance and discordance per virus. We found a statistically significant difference in Ct values between concordant and discordant RSV and RSV A cases (p < 0.01;

Figure 2A and

Figure 2B and

Table 1). However, no significant difference was detected for Flu A/B and RSV B (p > 0.05;

Figure 2C and

Figure 2D), likely due to the limited number of positive cases identified for these viruses. Overall, these observations suggest that discordant results likely occurred near the detection limit of the ML Ag Combo RDT.

3.2.3. ML Ag Combo RDT Showed High Performance Across Different Metrics in Pediatric Hospital Settings

We evaluated the performance of the ML Ag Combo RDT in detecting RSV (types A and B) and influenza (types A or B) among Ethiopian children under 2 with ILI, using a 21% prevalence of RSV [

10]. Performance metrics included were sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, overall accuracy, and agreement with reference methods. Cohen's kappa (κ) was used to assess these metrics. Based on 470 NPS test results available for head-to-head comparison, the ML Ag Combo RDT demonstrated higher sensitivity for RSV (90.06%; 95% CI: 84.36–94.21%) than for Flu A/B (71.43 95% CI: 47.82%-88.72%). However, the overall accuracy was similar for both targets: 96.60% (95% CI: 94.51–98.05%) for RSV and 94.47% (95% CI: 91.37–96.71%) for Flu A. (

Table 2)

The ML Ag Combo RDT showed a slightly higher positive predictive PPV for Flu A (100%; 95% CI: 76.84–100%) than for RSV (93.49%; 95% CI: 85.74–97.17%). Conversely, the NPV was higher for RSV (97.38%; 95% CI: 95.90–98.34%) than for Flu A/B (94%%; 95% CI: 90.80 -96.34 %) (

Table 2).

The ML Ag Combo RDT and the reference rRT-qPCR assay showed strong agreement (Cohen's κ = 0.90 [95% CI: 0.86–0.94] for RSV and 0.82 [95% CI: 0.7–0.96] for Flu A/B,

Table 2). These results suggest that the ML Ag Combo RDT is a reliable tool for detecting both viruses and shows strong concordance with the reference method for RSV. The high performance observed for RSV could be due to the fact that the assay detects two RSV antigens, the F and N proteins, which likely enhances its sensitivity, even in samples with lower concentrations.

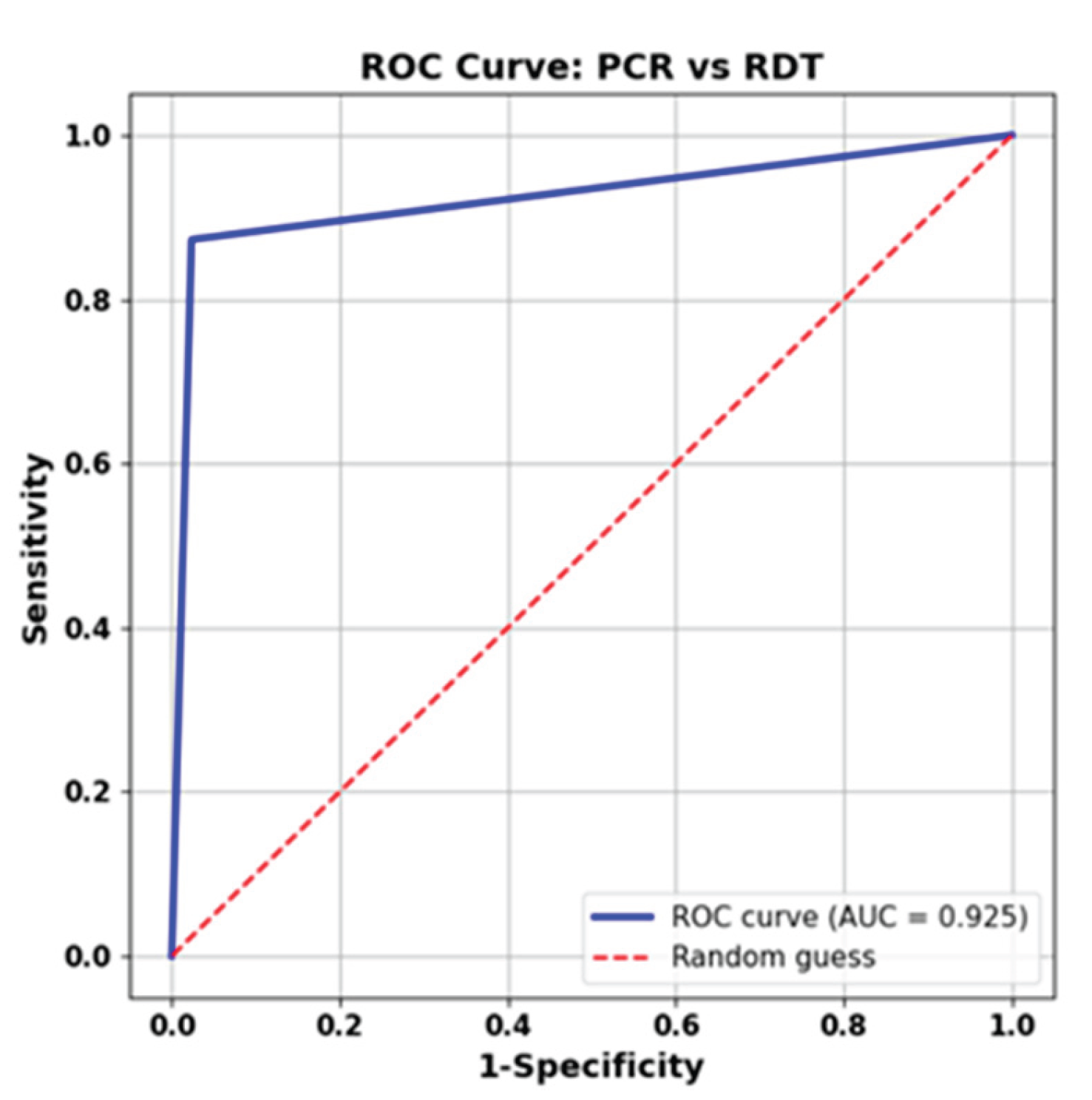

Furthermore, as shown in

Figure 3, we performed ROC curve analysis on the aggregated dataset, combining samples from all viruses, excluding SARS-CoV-2, as our reference, as rRT-qPCR did not detect it. The determined AUC for the ML Ag Combo RDT was 0.925, suggesting outstanding accuracy in detecting RSV and influenza virus infections.

We used all clinical specimens that tested negative by Allplex rRT-qPCR as true negatives (n = 298) to calculate the specificity of the ML Ag Combo RT for Flu A, Flu B, and RSV (n = 470). The ML Ag Combo RDT had high specificity for RSV (98.3%, CI: 96.13–99.45%) and 100% for influenza A/B (CI: 98.77–100%) (

Table 1 and

Table 2). Five samples that were identified as RSV by ML Ag Combo RDT were found to be negative by Allpex rRT-qPCR. To rule out the possibility of RNA extraction failure, these samples were retested using freshly extracted RNA from the original sample. None of the retests were positive by rRT-qPCR, and all had valid internal control results (

Figure 1). These five samples may represent false positives or post-infectious antigen persistence, which affects specificity. If the latter were the case, the RSV specificity could be even higher than 98.0%.

4. Discussion

In Ethiopia, respiratory viruses such as SARS-COV-2, RSV, and influenza viruses are co-circulating. During seasonal peak transmission, these viruses lead to hospitalization of children under five with respiratory symptoms [

9,

25,

26]. Performing multiple tests to identify and distinguish the virus(es) responsible for infection is time-consuming for healthcare workers and uncomfortable for children. Rapid multiplexed or Combo antigen detection tests can offer a more efficient alternative by detecting multiple viral pathogens from a single sample, guiding clinical management, and implementing effective control measures [27,.28]. This highlights the urgent need for validated multiplex or combo POCTs that can detect and differentiate these pathogens within two hours using just one clinical specimen. Such tools, especially in resource-limited settings like Ethiopia, can substantially improve the quality of pediatric care services by streamlining patient triage, optimizing bed usage, and reducing the risk of hospital-acquired infections [

29]. When test results from these RDTs are combined with POCTs that detect host biomarkers such as CRP and myxovirus resistance protein A (MxA), it can significantly reduce antibiotic misuse [

30].

This study evaluated the clinical performance of the ML Ag Combo RDT, a combined lateral flow assay designed to detect SARS-CoV-2, influenza A and B, and RSV. The ML Ag Combo RDT's performance was evaluated against the Allplex rRT-qPCR assay, the reference standard capable of simultaneously detecting and differentiating RSV (RSV A and RSV B) and influenza viruses (Flu A and Flu B) subtypes. Based on 470 NPS specimens with valid test results for both assays, the ML Ag Combo RDT demonstrated high sensitivity for RSV (90.06%) and moderate sensitivity for Flu A/B (71.43%) at a Ct cutoff of 42, as defined by the manufacturer. Restricting the analysis to samples with Ct values below 20, which indicates high viral loads, resulted in 100% sensitivity for both RSV and Flu A. These results suggest that the sensitivity of the ML Ag Combo RDT is closely related to viral load. The RDT also demonstrated high specificity, reaching 100% for Flu A/B and 98.3% for RSV. There was strong overall agreement with the reference rRT-qPCR assay, with Cohen’s kappa (κ) values of 0.90 for RSV and 0.824 for Flu A/B, indicating excellent concordance.

The sensitivity and specificity performance metrics from our evaluation suggest that the ML Ag Combo RDT is a reliable tool for detecting RSV and Flu A, with strong concordance with the reference rRT-qPCR assay for RSV. Its sensitivity was found to be better for RSV than Flu A. Perhaps relatively higher sensitivity for RSV because it targets two antigens (the F protein and the N protein) for RSV, while for Flu A/B, it targets only the N protein. Interestingly, unlike the ML Ag Combo RDT, most commercial RSV RDTs target either the F protein or the N protein [

28]. For example, the BinaxNOW™ RSV by Abbott detects the F protein, while the BD Veritor™ RSV by Becton Dickinson detects the N protein. These antigens may be expressed at different stages of RSV infection, allowing for detection across varying viral loads and time points.

The performance of the ML Ag Combo RDT for Flu A/B meets or exceeds the performance metrics previously reported for two commercially available combo antigen tests: the SARS-CoV-2/Influenza A + B/RSV Antigen Combo Rapid Test (Alltest) and the SARS-CoV-2/Flu A + B/RSV Antigen Rapid Test (Qingdao HighTop) [

16]. Both assays demonstrated high specificity, ranging from 99.48% to 100%, but sensitivity varied. The Alltest had sensitivities of 73.0% for influenza A and 44.4% for RSV in samples with Ct values <25. The ML Ag Combo RDT demonstrated higher sensitivity under similar Ct values <25—100% for influenza A and 96.9% for RSV. The Qingdao HighTop test reported sensitivities of 85% for Flu A and 100% for RSV in samples with Ct <25. The ML Ag Combo RDT exhibits superior sensitivity compared to the Alltest and is comparable to, if not better than, the Qingdao HighTop assay.

The present evaluated test achieved 100% sensitivity for RSV NPS samples with higher viral loads (Ct <20), mirroring the findings of Widyasari et al. [

31], who reported near-perfect RSV detection in high viral load specimens using the STANDARD QCOVID/FLU Ag Combo test.

The ML Ag Combo RDT's performance, particularly its sensitivity and specificity, was found to be either superior or non-inferior to other antigen-based POCTs for respiratory virus detection listed in the review paper by Basile and colleagues [

28]. The BD Directigen™ EZ Flu A + B, BD Veritor™ Influenza A + B, BD Veritor™ RSV (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), and the D Bioline Influenza Ag (Standard Diagnostics Inc., Gyeonggi, Korea) are the most widely used assays for this purpose. The lateral flow immunochromatographic platforms of these tests are similar to those of the ML Ag Combo RDT, further underscoring its comparative strength within this diagnostic category.

Our findings are consistent with those of Rosenblatt and colleagues [

31], who found similar κ values, as we found strong agreement between the ML Ag Combo RDT and the reference laboratory-based Allplex rRT-qPCR assay, with κ values of 0.90 for RSV and 0.82 for Flu A/B. This is further corroborated by AUC 0.925. This high level of agreement with our laboratory-based reference molecular method supports the use of the ML Ag Combo RDT as a POCT for pediatric patients presenting with respiratory symptoms.

Unlike our study, the Fluorecare® SARS-CoV-2 & Influenza A/B & RSV rapid antigen combo test demonstrated the highest sensitivity for influenza A (80.8%) and the lowest sensitivity for RSV (41.5%) [

32]. However, unlike our study, this study evaluated specimens from symptomatic children and adults presenting to the emergency department with flu-like symptoms. Additionally, a UK study reported slightly lower sensitivity (67.0%) for Flu using a multiplex LFA in adults with flu-like symptoms [

29]. The differences in the populations studied likely contributed to the variation in the performance of the tests between these studies and ours. Symptomatic children are more likely to have higher viral loads, which could improve the ML Ag Combo RDT's sensitivity. The enhanced sensitivity may also be linked to the kit design and the nature of RDT design (combo vs. multiplex). Combo antigen detection tests, like ours, may offer superior sensitivity compared to multiplexed platforms that target the same number of viral pathogens. Unlike multiplex platforms, which share reagents across multiple targets, combo formats have no competition for reagents or binding sites; each pathogen is detected in a dedicated reaction zone (

Figure S2).

The accuracy of the variety of commercial multiplex or combo antigen RDTs for detection of respiratory viruses such SARS-CoV-2, Flu and RSV is dependent on the tested populations (symptomatic vs asymptomatic; age of subject: children or vs adults), timing of sample collection from onset of symptoms, and chosen sample material, such as, nasal, nasopharyngeal, oropharyngeal, and throat swabs are used [

28,

33,

34]. For example, lower sensitivity for RSV was observed when throat swab was used instead of a nasal, nasopharyngeal, or trachea secretes [

35]. NPS was found to be a good matrix for the detection of RSV and flu in children using the BD Veritor™ System Rapid Test [

36]. In our study, only NPS were analyzed, and all of them were collected from hospitalized children with respiratory symptoms, a population likely to have higher viral loads. As such, the performance of the ML Ag Combo RDT may be overestimated when extrapolated to non-hospitalized or mildly symptomatic children in community settings, as well as in hospitalized adult subjects with respiratory symptoms. This concern is echoed by Caldwell and colleagues [

12], who noted that antigen test sensitivity tends to decline in outpatient or low-viral-load populations.

Notably, over 62% of symptomatic pediatric inpatients tested negative for SARS-CoV-2, influenza viruses, and RSV (

Figure 2), highlighting the need for host biomarkers such as myxovirus resistance protein A (MxA) and C-reactive protein (CRP)-based point-of-care tests (37) to guide antibiotic use and clinical triage. Similar observations were reported by Lim et al. (20), who emphasized the need for broader diagnostic panels or follow-up molecular testing in cases with high clinical suspicion but negative antigen results. We are currently evaluating the utility of the Fluorescence immunoassay (FIA) MxA assay and FIA CRP in our ongoing studies.

5. Study Strengths and Limitations

The study demonstrates several key strengths. First, it is the first in Ethiopia to validate an Ag Como RDT for detecting RSV, Influenza A/B, and SARS-CoV-2 from a single sample. Its ability to detect multiple pathogens with high accuracy supports a critical shift from syndromic management to diagnosis-driven, pathogen-specific treatment. Second, the sample size—particularly for RSV—was sufficiently large to ensure reliable analysis and strengthen the validity of the findings. Third, the study was conducted with strong methodological and analytical rigor, including the use of a well-established reference multiplex rRT-qPCR assay, which further reinforces the credibility of the results.

However, our study had limitations as well. One important limitation was the lack of a third diagnostic method to settle disagreements between the ML Ag Combo RDT and rRT-qPCR tests. For example, five samples that tested positive with the ML Ag Combo RDT tested negative with rRT-qPCR. These discordant results may indicate true positives that were missed by RT-PCR, particularly since antigen-based tests can detect residual viral proteins even after RNA has cleared. This is particularly relevant in pediatric patients who may have recently suffered RSV infections, but the virus has cleared to the level not to be detected by rRT-qPCR.

Another limitation was the underrepresentation of RSV B and influenza viruses, especially Flu B, which likely stems from our study population of hospitalized children under two years of age presenting with flu-like symptoms. Flu B circulates more widely among older children and adolescents, so its underrepresentation may reflect our age-specific sampling. Had we included older children, the prevalence of influenza, particularly Flu B, might have been higher. Additionally, RSV A has been more frequently associated with severe disease in young children than RSV B [

38].

A third limitation is that our samples came exclusively from symptomatic pediatric inpatients. Antigen tests generally show higher sensitivity in symptomatic children, especially early in the illness [

36]. Consequently, the performance of the ML Ag Combo RDT in our study may not reflect its accuracy in asymptomatic children, where sensitivity is likely lower.

A fourth limitation of this study is that the ML Ag Combo RDT does not detect other common respiratory viruses in children, such as rhinoviruses and adenoviruses [

15,

39]. Empirical treatment with antimicrobials could not be ruled out in positive cases unless test results are paired with host biomarker-based POCTs that distinguish viral from bacterial infections.

Lastly, due to funding constraints we did not conduct follow-up on treatment types and outcomes, limiting our ability to assess the impact of the ML Ag Combo RDT on antibiotic misuse.

6. Conclusions

The ML Ag Combo RDT demonstrates high specificity and strong diagnostic accuracy for RSV and influenza A/B detection in pediatric hospital settings (90.06% sensitivity; 98.3% specificity for RSV). When combined with the MxA and CRP levels ratio, this platform provides a comprehensive viral and host biomarker profile in under 20 minutes, potentially reducing antibiotic misuse and redefining RSV management in LMICs. Further studies with larger and more diverse populations are needed to confirm its broader clinical applicability.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1: rRT-qPCR graph showing Ct values for selected specimen samples; Figure S2: Photographs of the ML Ag Combo Rapid Test cassettes; Table S1: Sensitivity of Pooling of eight RNA samples with different proportions of known positive and negative RNA samples and their corresponding Ct values.; Tabel S2: Two-by-Two Table for Test comparison between ML Ag Combo Rapid Test and Allplex rRT-qPCR.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.G.; methodology, T.G. B.M., D.F and D. H; validation, A.A, B.M. and T.G.; formal analysis, B.M., A.A and T.G.; investigation, D.F, B.M. and D.H.; resources, B. M.; data curation, B.M.; writing—original draft preparation, T.G.; writing—review and editing, T.G., B.M., and D.F.; visualization, A. A and T.G.; supervision, T.G., A. A. A., and G.G; project administration, T.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the AHRI/ALERT Ethical Review Committee (Protocol number: PO/037/24 and dated on October 21, 2024.

Informed Consent Statement

Given all our study subjects were pediatric patients under 2 years of old, written informed consent was obtained from their parents or guardians who accompanied them during their hospitalization.

Data Availability Statement

Additional raw data is not presented due to patients’ privacy and most of the necessary data to support our key findings are presented the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the Armauer Hansen Research Institute (AHRI) for financial support for sample collection and laboratory reagents and administrative support. We also extend our sincere thanks to the University of Gondar for the sponsorship and the monthly stipend of the MSc student (Birhan Mulugeta) who contributed to this study.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare they have no conflict. No honorarium or other form of payment was given to anyone to produce the manuscript.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AHRI |

Armauer Hansen Research Institute |

| ARI |

Acute Respiratory Infections |

| AUC |

Arear Under Curve |

| CDC |

Center for Disease Control |

| CI |

Confidence Interval |

| COVID-19 |

Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| CRP |

C-Reactive Protein |

| CT |

Cycle Threshold |

| FIA |

Fluorescence immunoassay |

| ILI |

Influenza-like Illness |

| IQR |

Inter Quartile Range |

| LFA |

Lateral Flow Assay |

| LRTI |

Lower Respiratory Tract Infection |

| ML |

MobiLab |

| MxA |

Myxovirus Resistance Protein A |

| NP |

Nucleoprotein |

| NPS |

Nasopharyngeal Swab |

| NPV |

Negative Predictive Value |

| POCT |

Point-of-care Test |

| PPV |

Positive Predictive Value |

| RDT |

Rapid Diagnostic Test |

| RNA |

Ribo Nucleic Acid |

| RSV |

Respiratory Syncytial Virus |

| Flu A |

Influenza A virus |

| Flu B |

Influenza B virus |

| RSV A |

Respiratory syncytial virus A |

| RSV B |

respiratory syncytial virus B. |

| ROC |

Receiver Operating Characteristics |

| rRT-qPCR |

Real-Time Reverse Transcription Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| SARS-COV2 |

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome- Corona Virus 2 |

| VTM |

Viral Transport Medium |

References

- Wang X, Li Y, Deloria-Knoll M, Madhi SA, Cohen C, Arguelles VL, Basnet S, Bassat Q, Brooks WA, Echavarria M, Fasce RA, Gentile A, Goswami D, Homaira N, Howie SRC, Kotloff KL, Khuri-Bulos N, Krishnan A, Lucero MG, Lupisan S, Mathisen M, McLean KA, Mira-Iglesias A, Moraleda C, Okamoto M, Oshitani H, O’Brien KL, Owor BE, Rasmussen ZA, Rath BA, Salimi V, Sawatwong P, Scott JAG, Simões EAF, Sotomayor V, Thea DM, Treurnicht FK, Yoshida L-M, Zar HJ, Campbell H, Nair H. Global burden of acute lower respiratory infection associated with human parainfluenza virus in children younger than 5 years for 2018: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2021, 9, e1077–e1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson SE, Roca A, Alonso P, Simoes EAF, Kartasasmita CB, Olaleye DO, Odaibo GN, Collinson M, Venter M, Zhu Y, Wright PF. Respiratory syncytial virus infection: denominator-based studies in Indonesia, Mozambique, Nigeria and South Africa. Bull World Health Organ 2004, 82, 914–922. [Google Scholar]

- 2023 Respiratory Virus Response - NSSP Emergency Department Visits - COVID-19, Flu, RSV, Combined | Data | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://data.cdc.gov/Public-Health-Surveillance/2023-Respiratory-Virus-Response-NSSP-Emergency-Dep/vutn-jzwm/about_data. Retrieved 28 October 2025.

- Langley JM, Bianco V, Domachowske JB, Madhi SA, Stoszek SK, Zaman K, Bueso A, Ceballos A, Cousin L, D’Andrea U, Dieussaert I, Englund JA, Gandhi S, Gruselle O, Haars G, Jose L, Klein NP, Leach A, Maleux K, Nguyen TLA, Puthanakit T, Silas P, Tangsathapornpong A, Teeratakulpisarn J, Vesikari T, Cohen RA. Incidence of Respiratory Syncytial Virus Lower Respiratory Tract Infections During the First 2 Years of Life: A Prospective Study Across Diverse Global Settings. J Infect Dis 2022, 226, 374–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazur NI, Caballero MT, Nunes MC. Severe respiratory syncytial virus infection in children: burden, management, and emerging therapies.

- Moyes J, Tempia S, Walaza S, McMorrow ML, Treurnicht F, Wolter N, von Gottberg A, Kahn K, Cohen AL, Dawood H, Variava E, Cohen C. The economic burden of RSV-associated illness in children aged < 5 years, South Africa 2011–2016. BMC Medicine 2023, 21, 146.

- Getzzg. 2025. Estimating the economic burden of respiratory syncytial virus infection among children <2 years old receiving care in Maputo, Mozambique. JOGH. https://jogh.org/2025/jogh-15-04076/. Retrieved 28 October 2025.

- Tayachew A, Teka G, Gebeyehu A, Shure W, Biru M, Chekol L, Berkessa T, Tigabu E, Gizachew L, Agune A, Gonta M, Hailemariam A, Gedefaw E, Woldeab A, Alemu A, Getaneh Y, Lisanwork L, Yibeltal K, Abate E, Abayneh A, Wossen M, Hailu M, Workineh F. Prevalence of respiratory syncytial virus infection and associated factors in children aged under five years with severe acute respiratory illness and influenza-like illness in Ethiopia. IJID Reg 2024, 10, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wadilo F, Feleke A, Gebre M, Mihret W, Seyoum T, Melaku K, Howe R, Mulu A, Mihret A. Viral etiologies of lower respiratory tract infections in children < 5 years of age in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: a prospective case–control study. Virol J 2023, 20, 163. [Google Scholar]

- Tayachew A, Mekuria Z, Shure W, Arimide DA, Gebeyehu A, Berkesa T, Gonta M, Teka G, Kebede M, Melese D, Wossen M, Abte M, Hailu M, Berhe N, Medstrand P, Kebede N. Epidemiology of respiratory syncytial virus and its subtypes among cases of influenza like illness and severe acute respiratory infection: findings from nationwide sentinel surveillance in Ethiopia. BMC Infect Dis 2025, 25, 941. [Google Scholar]

- Shure W, Tayachew A, Berkessa T, Teka G, Biru M, Gebeyehu A, Woldeab A, Tadesse M, Gonta M, Agune A, Hailemariam A, Haile B, Addis B, Moges M, Lisanwork L, Gizachew L, Tigabu E, Mekuria Z, Yimer G, Dereje N, Aliy J, Lulseged S, Melaku Z, Abate E, Gebreyes W, Wossen M, Abayneh A. SARS-CoV-2 co-detection with influenza and human respiratory syncytial virus in Ethiopia: Findings from the severe acute respiratory illness (SARI) and influenza-like illness (ILI) sentinel surveillance, January 01, 2021, to June 30, 2022. PLOS Glob Public Health 2024, 4, e0003093. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell JM, Espinosa CM, Banerjee R, Domachowske JB. Rapid diagnosis of acute pediatric respiratory infections with Point-of-Care and multiplex molecular testing. Infection 2025, 53, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong HW, Heo JY, Park JS, Kim WJ. Effect of the Influenza Virus Rapid Antigen Test on a Physician’s Decision to Prescribe Antibiotics and on Patient Length of Stay in the Emergency Department. [CrossRef]

- Diagnostic utility of rapid antigen testing as point-of-care test for influenza and other respiratory viruses in patients with acute respiratory illness. [CrossRef]

- Swets MC, Russell CD, Harrison EM, Docherty AB, Lone N, Girvan M, Hardwick HE, Visser LG, Openshaw PJM, Groeneveld GH, Semple MG, Baillie JK. SARS-CoV-2 co-infection with influenza viruses, respiratory syncytial virus, or adenoviruses. The Lancet 2022, 399, 1463–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rapid multiplex PCR for respiratory viruses reduces time to result and improves clinical care: Results of a systematic review and meta-analysis. [CrossRef]

- Nelson PP, Rath BA, Fragkou PC, Antalis E, Tsiodras S, Skevaki C. Current and Future Point-of-Care Tests for Emerging and New Respiratory Viruses and Future Perspectives. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2020, 10, 181. [Google Scholar]

- Tai C-S, Jian M-J, Lin T-H, Chung H-Y, Chang C-K, Perng C-L, Hsieh P-S, Shang H-S. Analytical performance evaluation of a multiplex real-time RT-PCR kit for simultaneous detection of SARS-CoV-2, influenza A/B, and RSV. PeerJ 2025, 13, e19693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schober T, Wong K, DeLisle G, Caya C, Brendish NJ, Clark TW, Dendukuri N, Doan Q, Fontela PS, Gore GC, Li P, McGeer AJ, Noël KC, Robinson JL, Suarthana E, Papenburg J. Clinical Outcomes of Rapid Respiratory Virus Testing in Emergency Departments: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Intern Med 2024, 184, 528–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim H-J, Lee J-Y, Baek Y-H, Park M-Y, Youm D-J, Kim I, Kim M-J, Choi J, Sohn Y-H, Park J-E, Yang Y-J. Evaluation of Multiplex Rapid Antigen Tests for the Simultaneous Detection of SARS-CoV-2 and Influenza A/B Viruses. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 3267. [Google Scholar]

- 2020. Biological evaluation of medical devices—Part 1: Evaluation and testing within a risk management processANSI/AAMI/ISO 10993-1:2018; Biological evaluation of medical devices—Part 1: Evaluation and testing within a risk management process. AAMI.

- Meier, K. Guidance for Industry and FDA Staff - Statistical Guidance on Reporting Results from Studies Evaluating Diagnostic Tests.

- McHugh, ML. 2012. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem Med 276–282.

- Lee S. Guide to ROC and AUC for Statistical Analysis. https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/roc-auc-guide-statistical-analysis. Retrieved 2 November 2025.

- Chekol MT, Sugerman D, Tayachew A, Mekuria Z, Tesfay N, Alemu A, Gashu A, Shura W, Gonta M, Agune A, Hailemariam A, Assefa Y, Wossen M, Hassen A, Michele P, Silver R, Delelegn H, Briana L, Kasa T, Kebede N. Frontiers | Clinical and epidemiological characteristics of influenza and SARS-CoV-2 virus among patients with acute febrile illness in selected sites of Ethiopia 2021–2022. [CrossRef]

- Dulo B, Hinsene G, Mannekulih E. 2024. Viral etiology of respiratory infections among patients at Adama Hospital Medical College, a facility-based surveillance site in Oromia, Ethiopia. [CrossRef]

- CDC. 2025. Multiplex Assays Authorized for Simultaneous Detection of Influenza Viruses and SARS-CoV-2 by FDA. Influenza (Flu). https://www.cdc.gov/flu/hcp/testing-methods/flu-covid19-detection.html. Retrieved 28 October 2025.

- Basile K, Kok J, Dwyer DE. Point-of-care diagnostics for respiratory viral infections. Expert Rev Mol Diagn 2017, 18, 75–83. [Google Scholar]

- Batra R, Blandford E, Kulasegaran-Shylini R, Futschik ME, Bown A, Catton M, Conti-Frith H, Alexandridou A, Gill R, Milroy C, Harper S, Gettings H, Noronha M, Harrison H-L, Douthwaite S, Nebbia G, Klapper PE, Tunkel S, Vipond R, Hopkins S, Fowler T. 2025. Multiplex lateral flow test sensitivity and specificity in detecting influenza A, B and SARS-CoV-2 in adult patients in a UK emergency department. [CrossRef]

- Carlton HC, Savović J, Dawson S, Mitchelmore PJ, Elwenspoek MMC. Novel point-of-care biomarker combination tests to differentiate acute bacterial from viral respiratory tract infections to guide antibiotic prescribing: a systematic review.

- Rosenblatt KP, Romeu H, Romeu C, Granger E. Frontiers | Performance evaluation of a SARS-CoV-2 and influenza A/B combo rapid antigen test. [CrossRef]

- Bayart J-L, Gillot C, Dogné J-M, Roussel G, Verbelen V, Favresse J, Douxfils J. Clinical performance evaluation of the Fluorecare® SARS-CoV-2 & Influenza A/B & RSV rapid antigen combo test in symptomatic individuals. J Clin Virol 2023, 161, 105419. [Google Scholar]

- Aboagye FT, Annison L, Hackman HK, Acquah ME, Ashong Y, Owusu-Frimpong I, Egyam BC, Annison S, Osei-Adjei G, Antwi-Baffour S. Comparative evaluation of RT-PCR and antigen-based rapid diagnostic tests (Ag-RDTs) for SARS-CoV-2 detection: performance, variant specificity, and clinical implications. Microbiol Spectr 2024, 12, e00073–24. [Google Scholar]

- Widyasari K, Kim S, Kim S, Lim CS. Performance Evaluation of STANDARD Q COVID/FLU Ag Combo for Detection of SARS-CoV-2 and Influenza A/B. Diagnostics (Basel) 2022, 13, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franck KT, Schneider UV, Ma CMG, Knudsen D, Lisby G. Evaluation of immuview RSV antigen test (SSI siagnostica) and BinaxNOW RSV card (alere) for rapid detection of respiratory syncytial virus in retrospectively and prospectively collected respiratory samples. [CrossRef]

- Cantais A, Mory O, Plat A, Giraud A, Pozzetto B, Pillet S. Analytical performances of the BD VeritorTM System for the detection of respiratory syncytial virus and influenzaviruses A and B when used at bedside in the pediatric emergency department. Journal of Virological Methods 2019, 270, 66–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu M, Chen L, Cao J, Cai J, Huang S, Wang H, He H, Chen Z, Huang R, Ye H. Frontiers | Clinical application of Myxovirus resistance protein A as a diagnostic biomarker to differentiate viral and bacterial respiratory infections in pediatric patients. [CrossRef]

- Jung J-A, Wi P-H, Kim H. Comparisons of clinical characteristics between Respiratory Syncytial Virus A and B infection.

- van der Zalm MM, Sam-Agudu NA, Verhagen LM. Respiratory adenovirus infections in children: a focus on Africa. Curr Opin Pediatr 2024, 36, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).