1. Introduction

Code generation has emerged as one of the most transformative applications of Large Language Models (LLMs), fundamentally reshaping software development practices across diverse programming paradigms. Following the remarkable success of models like Codex [

1] and CodeLlama [

2], LLM-based code generation has demonstrated unprecedented capabilities in translating natural language specifications into executable code for general-purpose programming languages such as Python, Java, and C++ [

3]. This success has catalyzed extensive research exploring LLM applications beyond traditional software engineering, extending into specialized domains including scientific computing [

4], web development [

5], and domain-specific languages [

6,

7].

However, the realm of hardware design presents fundamentally distinct challenges that differentiate it from conventional software development. The Electronic Design Automation (EDA) industry faces escalating complexity in modern integrated circuit design, where the productivity gap between hardware capabilities and design resources continues to widen [

8]. Hardware Description Languages (HDLs) such as Verilog demand specialized domain expertise encompassing intricate knowledge of digital circuit design, timing constraints, and hardware architecture principles. Traditional hardware design workflows, characterized by manual coding, extensive verification cycles, and iterative refinement processes, frequently become bottlenecks in meeting the demands of rapidly evolving technological requirements. Furthermore, the hardware design industry confronts severe talent shortages, with the steep learning curve of HDLs creating barriers for entry-level engineers and limiting productivity even among experienced designers. Verilog code generation represents a particularly compelling research direction due to several fundamental distinctions from software code generation [

150]:

Concurrency: hardware systems are inherently parallel, requiring simultaneous consideration of multiple signal paths unlike sequential software execution;

Timing constraints: designs must satisfy strict timing requirements including setup/hold times and propagation delays;

Physical limitations: generated code must respect area, power, and routing constraints that directly impact manufacturing feasibility;

Synthesizability: verification encompasses functional correctness and timing closure beyond traditional software testing;

Domain expertise: effective generation demands deep understanding of digital logic and computer architecture.

These unique characteristics underscore both the potential impact and inherent difficulty of applying LLMs to Verilog code generation.

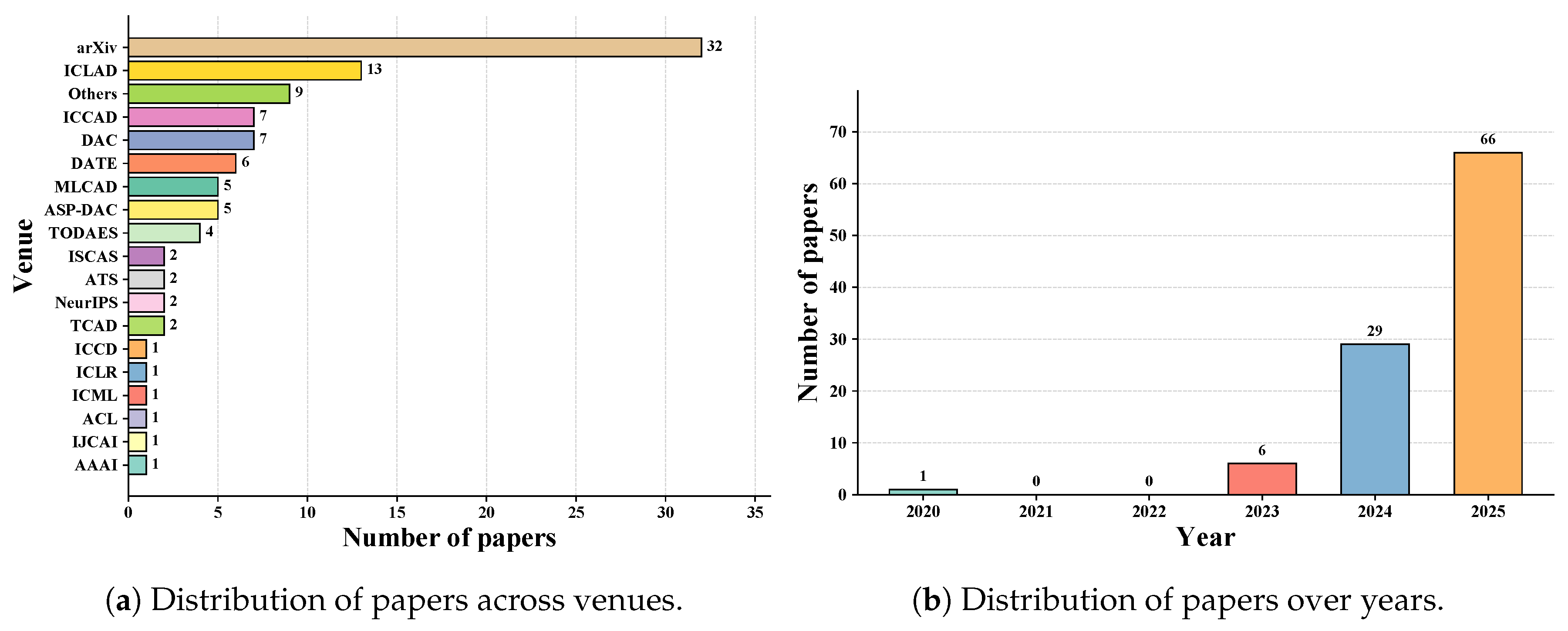

Research interest in LLM-based Verilog code generation has experienced remarkable growth since its inception. Our comprehensive literature analysis reveals an explosive trajectory: beginning with a single pioneering study in 2020 [

9], the field remained relatively dormant through 2022, but subsequently exponential dramatic expansion with 6 papers in 2023, 29 papers in 2024, and an impressive 64 papers in 2025 alone, which can be seen in

Figure 1. This research spans multiple disciplinary boundaries, appearing across premier venues in artificial intelligence, electronic design automation, and emerging interdisciplinary forums. However, this phenomenon has resulted in fragmented knowledge across diverse research communities with inconsistent terminologies, evaluation metrics, and optimization approaches. Despite this rapid growth, the field lacks a comprehensive systematic review unifying these scattered contributions. This gap prevents the research community from identifying promising directions, understanding how well different approaches work, establishing best practices, and avoiding repeated efforts.

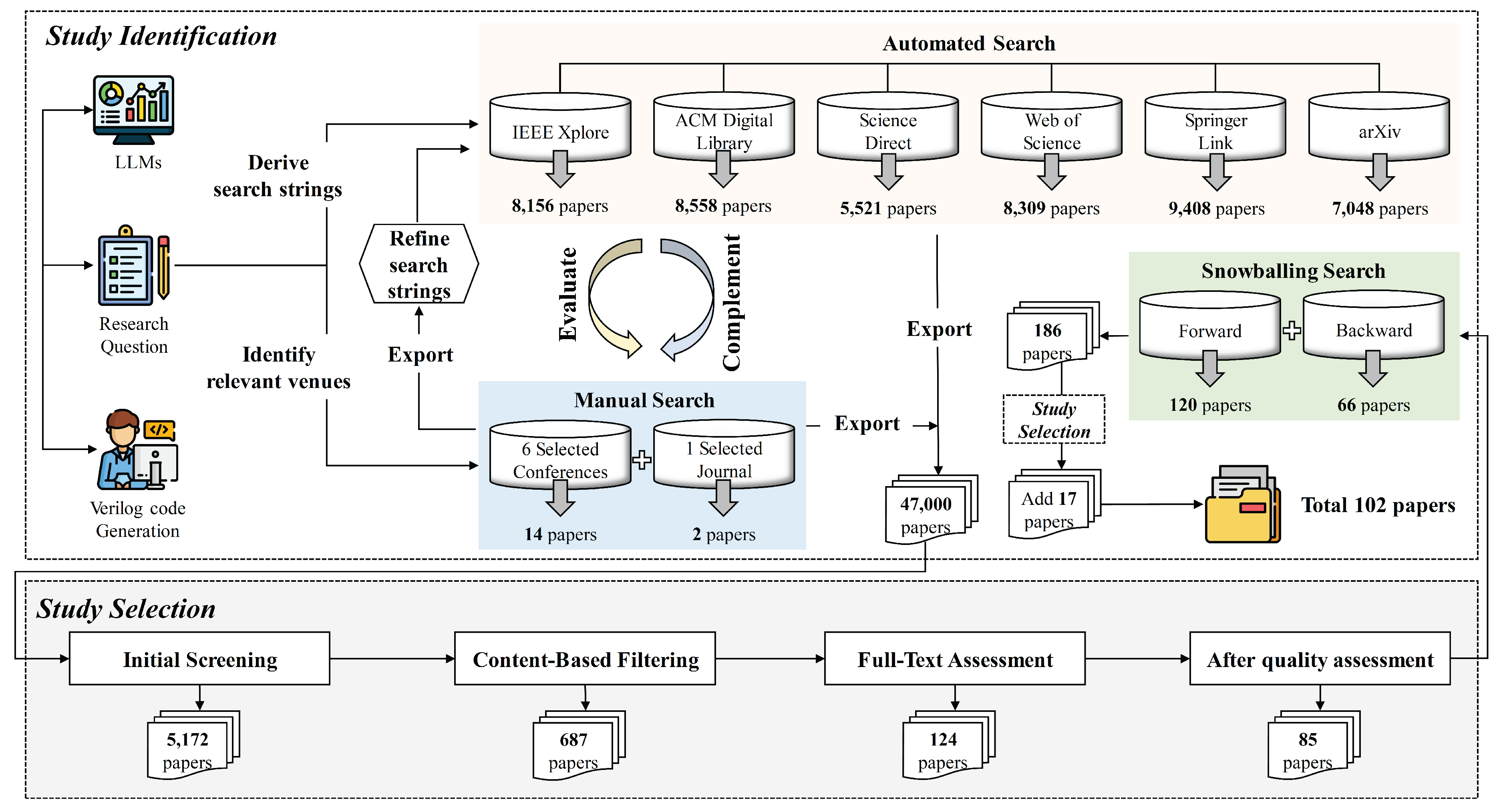

To fill this critical research gap, we conducted a rigorous Systematic Literature Review (SLR) following established methodologies [

10]. As shown in

Figure 2, we employed the Quasi-Gold Standard (QGS) search strategy [

11], combining manual searches across seven premier conferences and journals (AAAI, ACL, ICML, ICLR, NeurIPS, DAC, and TCAD) with automated searches spanning six academic databases (IEEE Xplore, ACM Digital Library, ScienceDirect, Web of Science, SpringerLink, and arXiv). Our comprehensive search yielded a substantial pool of candidate papers, which underwent systematic three-stage filtering including title/abstract screening, full-text assessment, and quality evaluation. Supplementary forward and backward snowballing identified additional relevant studies. This rigorous process yielded 102 high-quality papers (70 peer-reviewed publications and 32 high-quality preprints) made publicly available from 2020 through October 2025, forming the empirical foundation for our analysis. Our investigation addresses four fundamental research questions examining the LLMs employed (RQ1), dataset construction and evaluation methodologies (RQ2), adaptation and optimization techniques (RQ3), and alignment approaches for human-centric requirements (RQ4).

Related Literature Reviews. While several surveys have examined LLM applications in code generation, software engineering, and hardware design automation, our work represents the first comprehensive review focusing specifically on Verilog code generation.

Table 1 summarizes how our work differs from existing literature reviews. Prior surveys fall into two primary categories: (1)

general code generation surveys that predominantly concentrate on high-level programming languages like Python and Java but neglect hardware description languages, and (2)

broad EDA surveys that cover multiple aspects of hardware design automation without in-depth analysis of LLM-based Verilog generation.

General code generation [

12,

17] and low-resource domain-specific programming language surveys [

6] provide valuable insights into LLM architectures and code generation techniques, but neither addresses the unique challenges of hardware description languages such as timing constraints, synthesizability requirements, and physical design considerations. Recent EDA-focused surveys [

14,

15,

16] examine broader applications of AI in electronic design automation, including various stages of the design flow. While some mention LLMs for RTL generation, they lack systematic analysis of Verilog-specific datasets, evaluation methodologies, and alignment techniques. In contrast, our survey presents the first comprehensive review of LLMs for Verilog code generation, systematically analyzing model architectures, dataset construction, evaluation methods, and alignment techniques from both hardware design and AI perspectives.

In general, this study makes the following contributions:

We present the first systematic literature review on LLM-based Verilog code generation, analyzing 102 papers (70 peer-reviewed, 32 high-quality preprints) spanning 2020-2025.

We provide comprehensive taxonomy and trend analysis of LLMs for Verilog generation (RQ1), systematically analyze dataset construction and evaluation evolution across 27 benchmarks and 34 training datasets (RQ2), investigate adaptation and optimization techniques (RQ3), and examine alignment techniques addressing human-centric requirements including security, efficiency, copyright, and hallucinations (RQ4).

We identify key research limitations and propose a comprehensive roadmap for future directions in LLM-assisted hardware design.

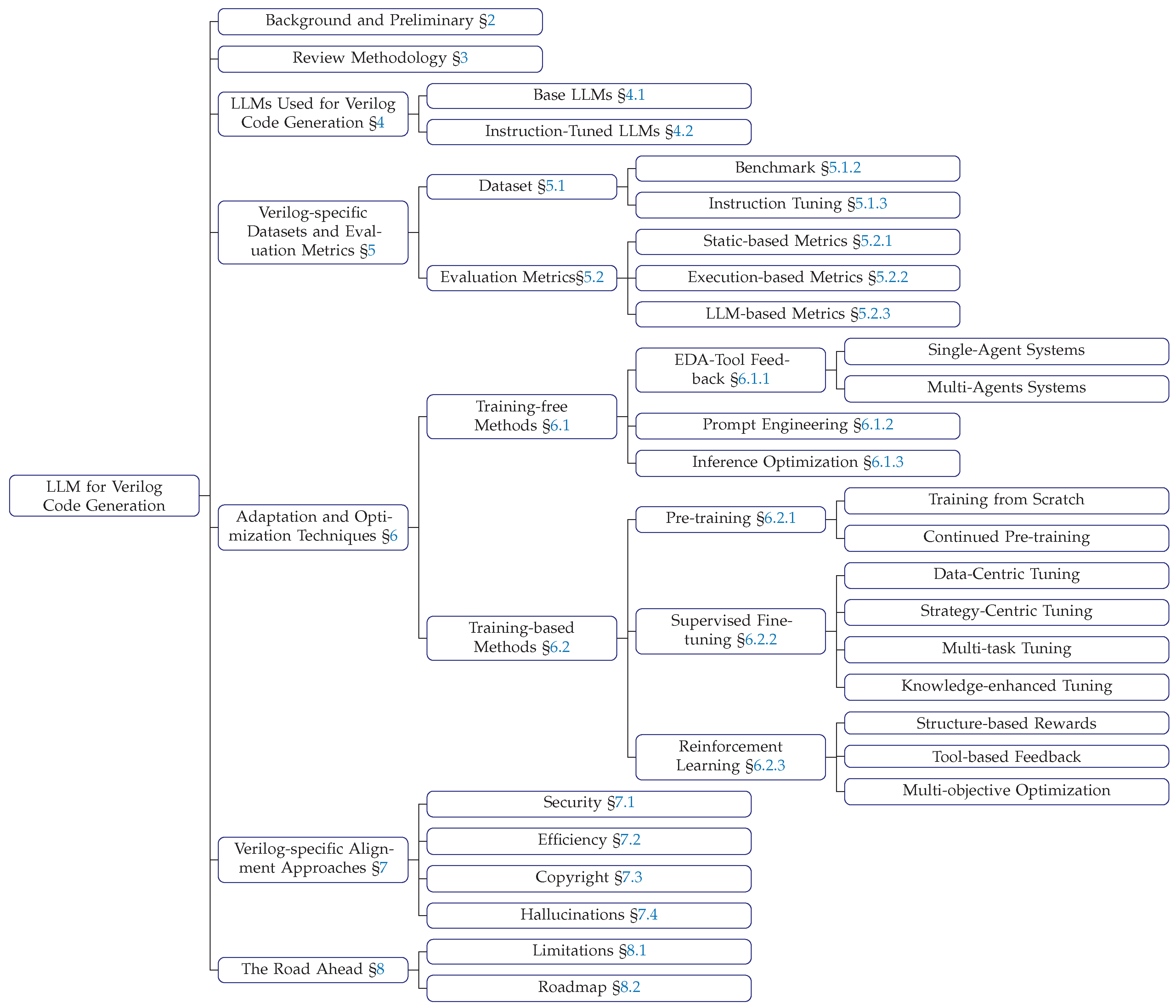

Survey Structure. Figure 3 illustrates the organization of this survey.

Section 2 provides essential background on Large Language Models and Verilog code generation within the EDA workflow.

Section 3 details our systematic review methodology including search strategy, selection criteria, and quality assessment procedures.

Section 4 examines the landscape of LLMs employed for Verilog code generation, categorizing Base LLMs and instruction-tuned models with trend analysis.

Section 5 investigates dataset construction methodologies and evaluation metrics, analyzing both benchmark and instruction-tuning datasets alongside the evolution of assessment approaches.

Section 6 explores adaptation and optimization techniques for enhancing LLM performance in Verilog generation tasks.

Section 7 analyzes alignment approaches addressing security, efficiency, copyright, and hallucination challenges.

Section 8 and

Section 9 discusses limitations of current research and presents a roadmap for future directions. Finally,

Section 10 concludes the survey with key takeaways and perspectives on the field’s trajectory.

2. Background and Preliminaries

2.1. Large Language Models

LLMs represent a major breakthrough in artificial intelligence, characterized by massive-scale (billions to trillions of parameters) transformer-based architectures [

18]. Through self-supervised learning on vast text corpora, these models acquire sophisticated capabilities in understanding linguistic patterns, encoding domain knowledge, and performing complex reasoning tasks.

Since the introduction of GPT-3 [

19] in 2020, LLMs have demonstrated remarkable proficiency in natural language understanding and generation across diverse domains. Modern LLMs fall into two main categories:

base models, pretrained on large-scale general corpora to establish foundational language understanding, and

instruction-tuned models, further refined through supervised fine-tuning or reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF) [

20] to better follow instructions and align with human preferences.

The power of LLMs lies in their adaptability to domain-specific tasks through various techniques. Prompt engineering guides model behavior through carefully designed input templates; in-context learning enables few-shot adaptation without updating parameters; and fine-tuning adjusts model parameters on task-specific datasets. These capabilities have made LLMs highly effective for automating complex tasks, with code generation emerging as a particularly successful application that bridges natural language and formal programming languages.

2.2. Verilog Code Generation

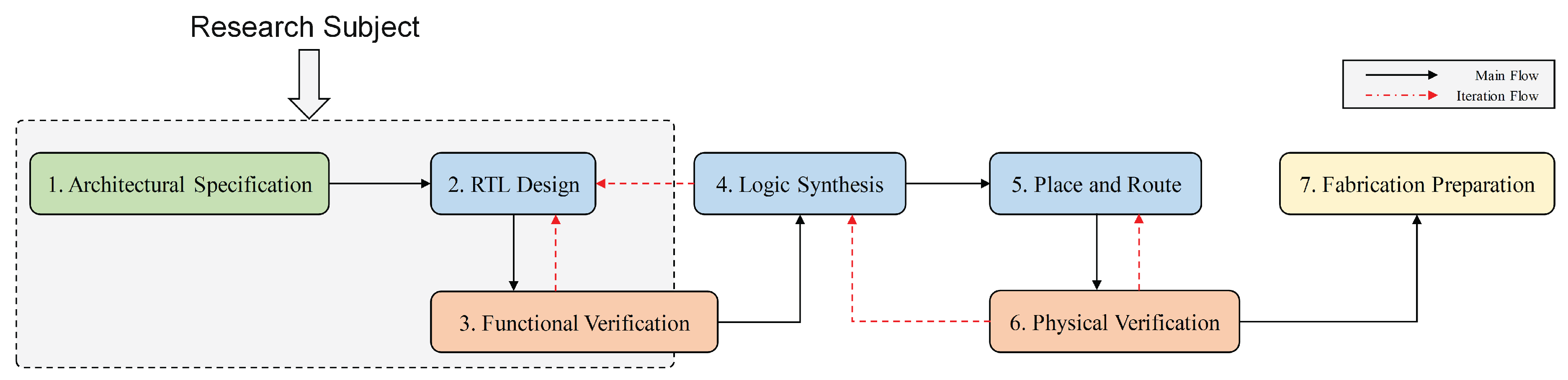

As illustrated in

Figure 4, the EDA workflow for integrated circuit development follows a systematic sequence of seven interconnected phases with iterative refinement loops. The process begins with

Architectural Specification (Phase 1), where system-level requirements and functionalities are formally defined. This feeds into

RTL Design (Phase 2), where HDLs like Verilog describe the hardware architecture through registers, data paths, and control logic.

Functional Verification (Phase 3) validates behavioral correctness against specifications through simulation using testbenches, which are structured verification environments containing test vectors, stimulus generators, and monitoring logic to systematically exercise the design under test, with iteration back to RTL design when errors are detected. Subsequently,

Logic Synthesis (Phase 4) transforms verified RTL into gate-level netlists. Following synthesis, timing simulation verifies timing correctness at the netlist level, potentially iterating with verification for optimization.

Place and Route (Phase 5) determines physical component placement and interconnections on the silicon die, followed by

Physical Verification (Phase 6) that checks design rules, timing constraints, and signal integrity with iterative refinement loops. Finally,

Fabrication Preparation (Phase 7) generates GDSII files and manufacturing documentation for trial tape-out. After successful physical testing of the fabricated prototype, the design proceeds to mass production.

Verilog code generation, as highlighted in the dashed box of

Figure 4, primarily targets the first three phases of this workflow, forming a critical iterative cycle. Natural language specifications from architectural design are transformed into synthesizable Verilog code during RTL design, which is then validated through functional verification. The iterative feedback loop between verification and RTL design enables refinement until correctness is achieved. The quality of generated Verilog code directly impacts all downstream processes, influencing synthesis optimization opportunities, achievable clock frequencies, power consumption profiles, and ultimately manufacturing feasibility.

LLM-based Verilog code generation can be formally represented as a mapping function , where represents the model parameters, D denotes natural language descriptions encompassing both functional specifications (design intent and behavioral requirements) and design constraints (timing requirements, area budgets, power targets, interface protocols), I denotes optional multimodal inputs (circuit diagrams, timing waveforms, state machine diagrams), and V is the generated Verilog code. Text-only generation, which represents the majority of current approaches, simplifies to .

The correctness evaluation of generated Verilog code employs a verification function , where V represents the generated code, S denotes specifications or reference implementations, T represents testbenches with input-output test vectors, and M captures quality metrics. This evaluation encompasses: (1) syntactic validation through HDL parsers ensuring compilability; (2) functional correctness via simulation-based testing where ; (3) semantic similarity measuring structural correspondence with reference implementations through AST comparison or text-based metrics; and (4) formal equivalence proving mathematical equivalence between generated and reference designs using formal verification tools.

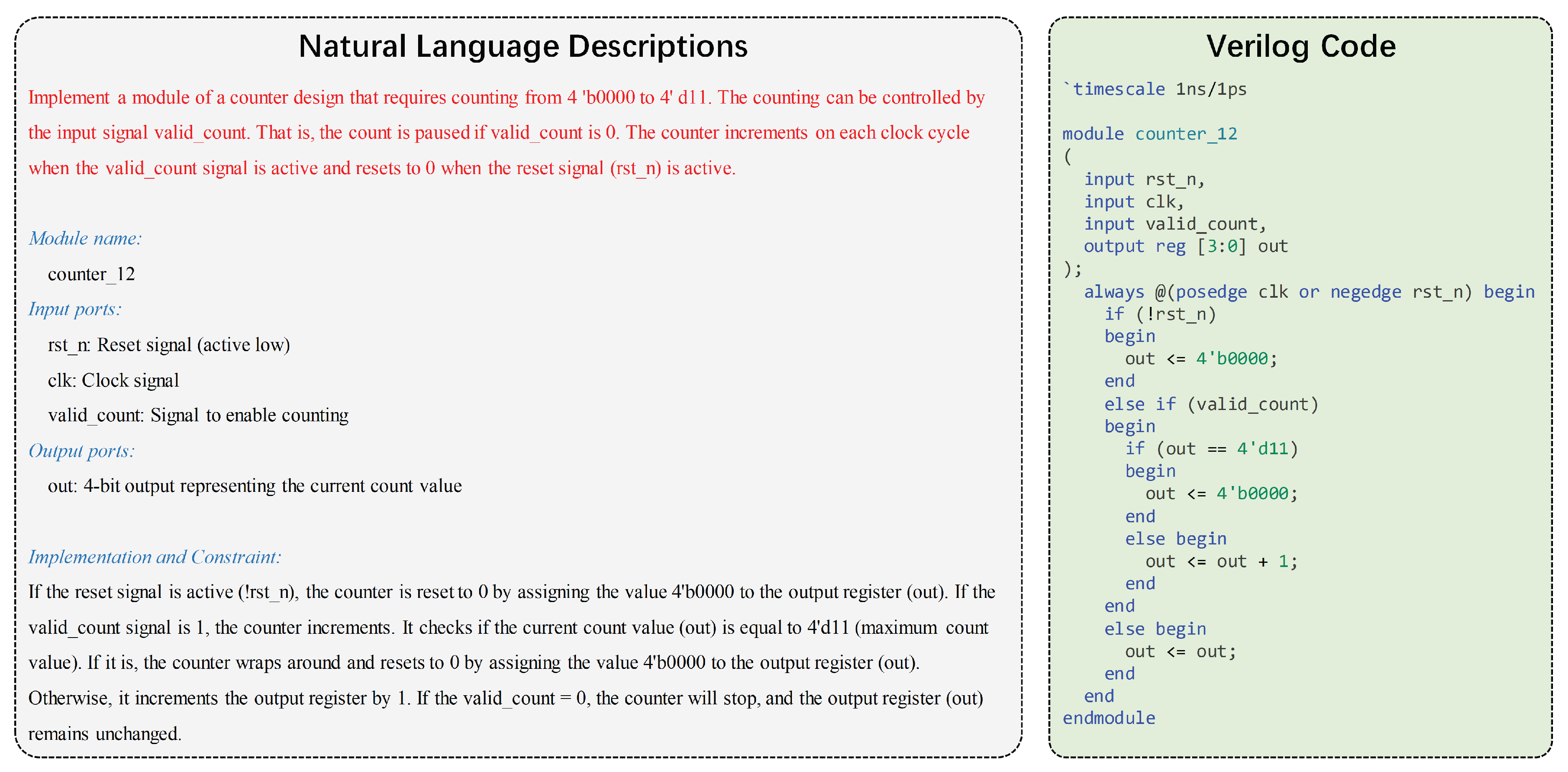

Figure 5 illustrates a practical example from RTLLM-v2 [

21], where a natural language specification is transformed into synthesizable RTL code for a 4-bit counter (0 to 11) with pause and reset functionality. This example demonstrates essential HDL design elements: synchronous sequential logic with asynchronous reset (

always @(posedge clk)), conditional state transitions based on control signals, and bounded counting behavior. The natural language input contains both functional specifications (counting logic, range limits) and behavioral requirements (reset handling, pause control), which must be correctly interpreted into standard Verilog constructs. In terms of our formal representation,

D is the counter specification,

V is the generated Verilog module, and verification would involve testbenches

T that validate counting behavior under various conditions.

3. Review Methodology

Following the guide by Kitchenham et al. [

10], which is used in most other SLRs [

22,

23,

24], our methodology is organized as follows: planning the review (i.e.,

Section 3.1,

Section 3.2), conducting the review (i.e.,

Section 3.3), and analyzing the basic review results (i.e.,

Section 3.4).

3.1. Research Question

To provide a comprehensive overview of LLM for Verilog code generation, it is important to fully understand the construction of Verilog domain-specific datasets, how LLMs are currently being applied in Verilog code generation, the challenges they face, and their potential future research directions in this domain. Thus, we aim to provide an SLR of the application of LLMs to Verilog code generation. This study thus aims to answer the following research questions:

RQ1: What LLMs have been employed to solve Verilog code generation tasks? Identifying the architectures of LLMs utilized in Verilog code generation is fundamental to establishing the current technological landscape and understanding model selection patterns in this emerging field. This comprehensive taxonomy enables systematic comparative analysis of different LLMs (i.e., general-purpose Base LLMs vs. domain-specific IT LLMs, open-source vs. closed-source) and their adoption trends, revealing the evolution of model preferences and the growing diversity in this rapidly expanding research domain.

RQ2: How are Verilog-specific datasets constructed and what evaluation metrics are utilized to assess LLMs? Understanding the construction methodologies of Verilog-specific datasets and the evaluation metrics employed for LLM assessment is critical, as these factors directly influence the reliability of conclusions drawn about model capabilities. This investigation is pivotal for interpreting model performance, ensuring benchmark validity, and guiding dataset optimization strategies for Verilog code generation tasks.

RQ3: What adaptation and optimization techniques are applied in Verilog code generation? Examining the adaptation and optimization techniques employed in Verilog code generation is crucial for revealing effective strategies that customize general-purpose LLMs to accommodate the unique syntax, semantics, and constraints of Verilog. This understanding is central to enhancing model performance in domain-specific tasks and advancing the field’s methodological foundations.

RQ4: What alignment techniques are employed for meeting human-centric requirements? Investigating alignment techniques is essential for ensuring that LLM-generated Verilog code conforms to human intentions and values. This becomes particularly critical considering potential risks such as copyright infringement, security vulnerabilities, inefficiencies, and trustworthiness issues, which may have severe consequences when code is implemented by users without specialized programming expertise in hardware design.

3.2. Search Strategy

As shown in

Figure 2, we employed the “Quasi-Gold Standard” (QGS) [

11] approach for comprehensive paper search. The QGS methodology involves manual search to identify a set of relevant studies from which search strings are extracted. Subsequently, these search strings are utilized to perform automated searches, followed by snowballing techniques to further supplement the search results. Finally, we applied a series of rigorous filtering procedures to obtain the most pertinent studies for our review.

Given that the first application of LLMs to Verilog code generation emerged in 2020 [

9], our search strategy specifically targets publications from 2020 to 2025, ensuring comprehensive coverage of this emerging research domain.

3.2.1. Search Items

During the manual search phase, we selected eight premier conferences and journals spanning artificial intelligence, machine learning, and electronic design automation domains (i.e., AAAI, ACL, ICML, ICLR, NeurIPS, DAC, and TCAD, as detailed in

Table 2), and systematically retrieved papers applying LLMs to Verilog code generation tasks. Following the manual search process, we identified 16 papers (14 papers from conferences and 2 papers from journals) that aligned with our research objectives. These 16 relevant publications constitute the foundational corpus for constructing our QGS, serving as the basis for extracting comprehensive search terms and validating our automated search strategy.

Our search string construction follows a systematic approach by combining two complementary keyword sets: one pertaining to Verilog code generation tasks and another related to LLMs. A paper is considered potentially relevant only when it contains keywords from both categories, thereby ensuring higher precision in our search results. The comprehensive search keyword sets are as follows:

Keywords related to Verilog code generation (12 terms): Verilog, HDL, Hardware Description Language, RTL, Register Transfer Level, Digital Design, Hardware Design, Electronic Design Automation, EDA, Verilog Generation, FPGA, ASIC

Keywords related to LLMs (13 terms): LLM, Large Language Model, Language Model, GPT, ChatGPT, Transformer, fine-tuning, prompt engineering, In-context learning, Natural Language Processing, NLP, Machine Learning, AI

Here is our used command search string:

(Verilog OR ``Hardware Description Language’’ OR ``Register Transfer Level’’ OR

``Digital Design’’ OR ``Hardware Design’’ OR ``Electronic Design Automation’’ OR

``EDA’’ OR ``Verilog Generation’’ OR ``FPGA’’ OR ``ASIC’’)

AND

(LLM OR ``Large Language Model’’ OR ``Language Model’’ OR ``GPT’’ OR ``ChatGPT’’ OR

``Transformer’’ OR ``fine-tuning’’ OR ``prompt engineering’’ OR ``In-context learning’’

OR ``Natural Language Processing’’ OR ``NLP’’ OR ``Machine Learning’’ OR AI)

It is important to note that our LLM-related keyword list encompasses broader terms such as machine learning and deep learning, which may not be exclusively associated with LLMs. This inclusive approach is deliberately adopted to maximize recall and minimize the risk of omitting potentially relevant studies, thereby broadening our search scope during the automated search process to ensure comprehensive coverage of the literature.

3.2.2. Search Databases

Following the establishment of our search strings, we conducted systematic automated searches across six widely recognized academic databases: IEEE Xplore [

25], ACM Digital Library [

26], ScienceDirect [

27], Web of Science [

28], SpringerLink [

29], and arXiv [

30]. Consistent with our temporal scope targeting publications from 2020 onward, we applied appropriate date filters to each database search. The automated search process yielded 8,156 papers from IEEE Xplore, 8,558 papers from ACM Digital Library, 5,521 papers from ScienceDirect, 8,309 papers from Web of Science, 9,408 papers from SpringerLink, and 7,048 papers from arXiv, resulting in a total of about 47,000 papers for subsequent screening and evaluation.

3.3. Search Selection

3.3.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

To ensure methodological rigor and systematic paper selection, we established well-defined inclusion and excl usion criteria grounded in established best practices from leading systematic literature reviews [

31,

32], as presented in

Table 3. These criteria were meticulously designed to guarantee that selected studies directly address our research questions while maintaining objectivity and reproducibility.

1

Our paper selection process employed a three-stage filtering approach to systematically reduce the candidate pool while preserving study quality:

Stage 1 (Initial Screening): We applied exclusion criteria 1 and 6 to eliminate short papers (< 5 pages) and duplicate publications, reducing our corpus to 5,172 papers. This preliminary filter ensured that only substantial, original contributions proceeded to detailed evaluation.

Stage 2 (Content-Based Filtering): Manual examination of publication venues, titles, and abstracts further refined our selection to 687 papers. We deliberately retained high-quality arXiv preprints to capture emerging research trends while excluding non-peer-reviewed materials such as books, keynote records, technical reports, theses, tool demonstrations, editorials, and survey papers (exclusion criteria 2-3).

Stage 3 (Full-Text Assessment): Comprehensive full-text review enabled precise relevance determination. Studies exclusively addressing Verilog code repair, optimization, or test case generation without code generation components were excluded (exclusion criterion 5), except where these activities served as auxiliary components enhancing generation performance. We also eliminated studies that mentioned LLMs only conceptually in future work sections without implementation (exclusion criterion 4). This final stage yielded 124 primary studies directly relevant to our research topic.

3.3.2. Quality Assessment

To mitigate potential bias from low-quality studies and provide readers with transparent quality indicators, we implemented a comprehensive quality assessment framework. Our evaluation protocol comprises five Quality Assessment Criteria (QACs), as detailed in

Table 4, designed to systematically evaluate the relevance, methodological rigor, clarity, and scholarly significance of selected studies [

33].

Each quality assessment criterion was evaluated using a four-point Likert scale (0-3), where 0 indicates the lowest quality and 3 represents the highest quality. To maintain high standards while accommodating methodological diversity, we established a threshold of 12 points (representing 80% of the maximum possible score of 15) for study inclusion. For arXiv preprints lacking formal publication venues, we assigned a score of 0 for QAC1 (venue prestige) while evaluating the remaining criteria. Preprints achieving the overall threshold score of 12 were retained to capture cutting-edge research contributions that may not yet have undergone traditional peer review but demonstrate substantial methodological and theoretical merit.

Following quality assessment, our final corpus comprised 85 studies: 55 peer-reviewed publications from prestigious venues and 30 high-quality preprints that met our established criteria. This balanced approach ensures both scholarly rigor and inclusivity of emerging research trends in the rapidly evolving field of LLM-based Verilog generation.

3.3.3. Forward and Backward Snowballing

To ensure comprehensive literature coverage and minimize the risk of overlooking relevant studies during our manual and automated search processes, we conducted systematic forward and backward snowballing procedures [

34]. This supplementary search strategy involves examining both the reference lists of our selected primary studies (backward snowballing) and publications that subsequently cite these studies (forward snowballing).

The snowballing process was implemented as follows: First, we systematically reviewed the reference lists of our 85 primary studies to identify potentially relevant publications that may have been missed in our initial search. Second, we utilized citation databases to identify papers that cite our selected studies, focusing on recent publications that might represent emerging developments in the field. The supplementary search yielded 186 additional papers, which were subsequently subjected to our established selection pipeline, including screening against inclusion and exclusion criteria, duplicate removal, and quality assessment. Following this rigorous evaluation process, we identified 15 additional relevant studies, resulting in a final corpus of 102 papers (70 peer-reviewed publications and 32 high-quality preprints) that form the foundation of our systematic literature review.

3.4. Data Extraction and Analysis

Through our comprehensive search and snowballing procedures, we ultimately obtained 102 relevant research papers.

Figure 1 provides an overview of the distribution of our selected papers. As shown in

Figure 1(a), 68 papers were published in peer-reviewed venues. ICCAD emerges as the most prominent venue among these, contributing 13 papers. Other significant contributing venues include DAC, DATE, and TCAD, which contributed 7, 6, and 5 papers respectively. Additionally, we observe that prominent AI-related venues such as NeurIPS, ICLR, ICML, ACL, and AAAI also contributed a substantial number of publications. This distribution indicates that LLM for Verilog code generation has garnered attention not only within hardware-related research communities but also within AI and machine learning research domains, reflecting the interdisciplinary nature of this emerging field.

The remaining 31 papers were published on arXiv and 1 paper were published on TechRxiv, an open-access platform serving as a repository for scholarly articles. This finding is not surprising, as many novel LLM for Verilog code generation studies are rapidly emerging, and numerous works have recently been completed and may currently be undergoing peer-review processes. Although these papers have not undergone formal peer review, we applied rigorous quality assessment procedures to all collected papers to ensure the validity and quality of our research findings. This approach enables us to include all high-quality and relevant publications while maintaining high research standards.

Figure 1(b) illustrates the temporal distribution of our selected papers. A rapid growth trend in publication numbers has been observed since 2023. There was only one relevant paper in 2020, while 2021 and 2022 saw no relevant publications. However, from 2023 to 2024, the number of papers increased dramatically from 6 to 29. Remarkably, by September 2025 alone, the number of published papers had already reached 66. This rapid growth trajectory demonstrates the increasing research interest in the LLM for Verilog code generation domain, highlighting its emergence as a significant area of investigation.

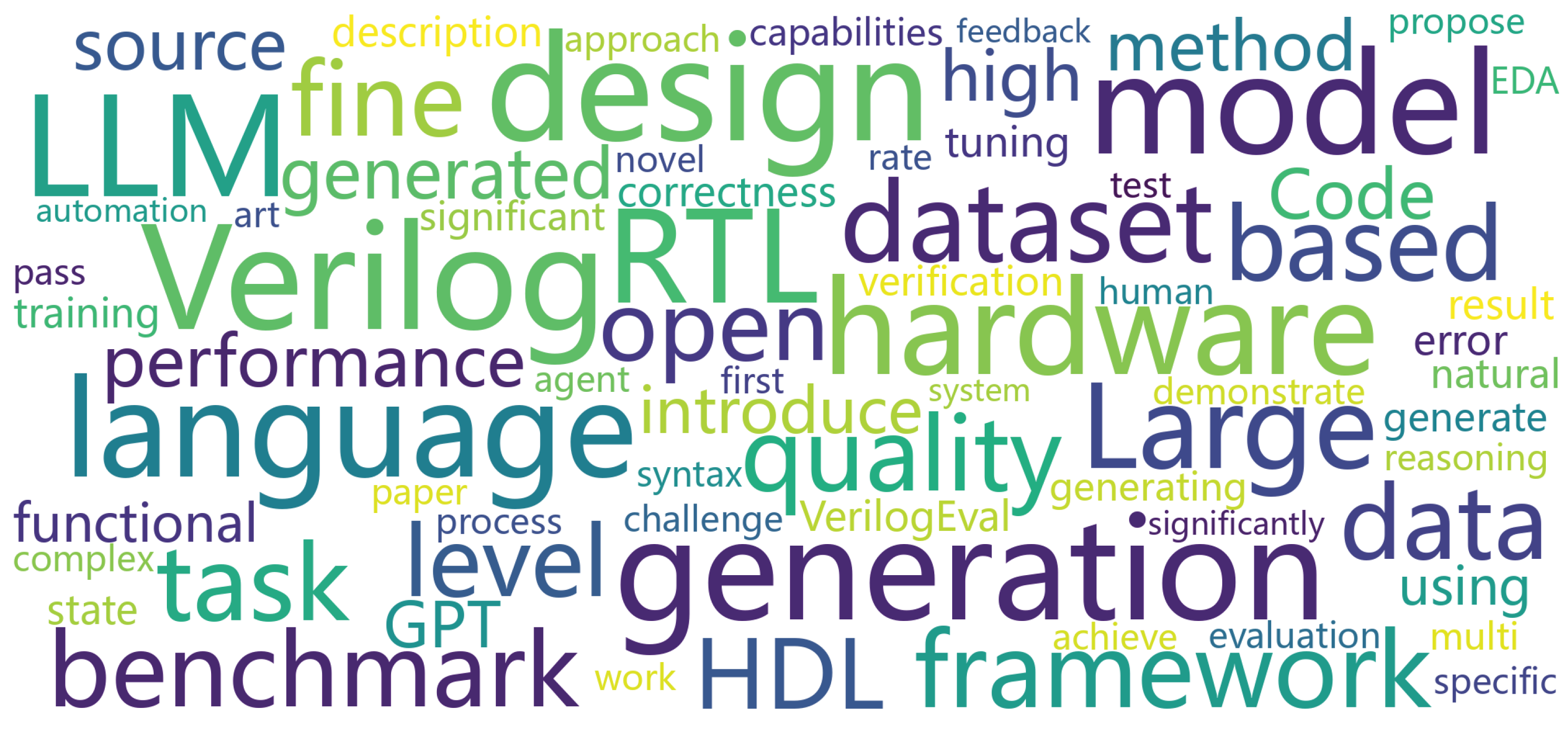

To visualize the primary content themes of our paper collection, we generated a word cloud based on the abstracts of all 102 papers, as shown in

Figure 6. The most frequently appearing terms include “Verilog”, “RTL”, “HDL”, “LLM”, “dataset”, “performance”, “quality”, “functional”, “syntax”, and “feedback”, clearly indicating the main topics explored in these papers. The terms “Verilog”, “RTL”, and “HDL” emphasize the core hardware description language elements, while “LLM”, “model”, and “code” represent the utilization of large language models in Verilog code generation tasks. The term “dataset” underscores the critical need for constructing Verilog domain-specific datasets in LLM for Verilog code generation research. Meanwhile, terms such as “performance”, “quality”, “functional”, “syntax”, and “feedback” reflect ongoing discussions about the effectiveness and evaluation of LLMs in Verilog code generation. The word cloud provides further visual evidence that our collected literature is highly relevant to our research focus.

4. RQ1: LLMs Employed for Verilog Code Generation

Through our systematic literature review of 102 included studies, we identify that researchers have employed a diverse range of LLMs for Verilog code generation tasks.

Statistical Scope. Our analysis encompasses all LLMs utilized in the reviewed papers, whether for method implementation or as baseline comparisons, ensuring comprehensive coverage of the LLM adoption landscape in Verilog code generation research. Based on their adaptation for Verilog tasks, we categorize these LLMs into two main types: Base LLMs (general-purpose models without Verilog-specific adaptation) and IT LLMs (models specifically Instruction-Tuned for Verilog code generation).

4.1. Analysis of Base LLMs

As shown in

Table 5 and

Table 6, Base LLMs represent the majority of models employed in Verilog code generation research, with 383 total mentions across all studies. Despite not being specifically designed for hardware description languages, these models demonstrate substantial capability in understanding and generating Verilog code through their general programming language comprehension.

4.1.1. Open-Source Base LLMs

Open-source Base LLMs demonstrate significant diversity and adoption, accounting for 204 mentions (53.3% of all Base LLM usage). The landscape is characterized by several key model families:

(1) Llama Family Leadership

The Llama ecosystem [

35] emerges as the most successful open-source family with 64 total mentions. While CodeLlama (23 mentions) [

2] leads within this family, it remains a general code generation model rather than a Verilog-specific adaptation. The rapid adoption of Llama3.1 (18 mentions) [

36] demonstrates the community’s preference for the latest general-purpose models.

(2) DeepSeek Series Growth

DeepSeek models [

37] secure strong adoption with 54 mentions, led by DeepSeek-Coder (27 mentions) [

38]. The emergence of reasoning variants like DeepSeek-R1 (8 mentions) [

39] reflects growing interest in advanced reasoning capabilities for complex Verilog generation tasks.

(3) Qwen Series Growth

Qwen series shows promising growth with 28 mentions, led by CodeQwen (13 mentions) [

40]. The introduction of Qwen2.5-Coder (12 mentions) [

41] continues this trend toward enhanced code generation capabilities.

(4) Other Code-Oriented Models

Other code generation models like CodeGen (12 mentions) [

42,

43] and StarCoder (11 mentions) [

44,

45] maintain steady usage, though their adoption remains modest compared to general-purpose foundation models. This suggests that scale and general capability often outweigh domain-specific code training for Verilog tasks.

(5) Other Models

A substantial portion (35 mentions) represents various other open-source models (e.g., CodeGemma [

46], CodeT5+ [

47], Phi [

48,

49], Nemotron [

50])

2, indicating the experimental nature of the field and researchers’ willingness to explore diverse solutions.

4.1.2. Closed-Source Base LLMs

Closed-source Base LLMs demonstrate strong adoption with 179 total mentions (46.7% of all Base LLM usage), dominated by major technology companies’ offerings:

(1) GPT-series LLMs

OpenAI’s GPT series [

51] dominates the closed-source landscape with 149 mentions (83.2% of closed-source usage). GPT-4 leads with 52 mentions, followed by GPT-3.5 (43 mentions) and GPT-4o (35 mentions). The introduction of reasoning models (GPT-o1: 6 mentions, GPT-o3: 4 mentions) reflects researchers’ exploration of advanced reasoning capabilities for complex Verilog code generation tasks.

(2) Other LLMs

Anthropic’s Claude series [

52] shows steady growth with 19 mentions, led by Claude 3.5 (8 mentions). Google’s Gemini [

53] represents a newer entrant with growing adoption (5 mentions) for Verilog code generation tasks.

Trends Analysis

The field demonstrates unprecedented expansion, with total LLM mentions growing from 12 in 2023 to 274 in 2025 (2,183% growth). This reflects the rapid maturation of LLM technology and researchers’ increasing confidence in applying these models to hardware design tasks.

We first analyze the trends in LLM adoption for Verilog code generation from the perspective of Open-Source and Closed-Source, as well as the Architectural preferences of Base LLMs.

(1) Open-Source vs. Closed-Source

While both categories show strong growth, their trajectories differ significantly, with distinct model evolution patterns:

-

Open-Source LLMs: Demonstrate accelerated growth (5 → 46 → 153 mentions) with 233% increase from 2024 to 2025. The evolution shows a clear shift from specialized code models to general-purpose foundation models:

- –

2023: Dominated by traditional code generation models (CodeGen: 3 mentions)

- –

2024: Transition to foundation families (Llama: 15, DeepSeek: 6, Qwen: 3 mentions)

- –

2025: Widespread adoption of latest foundation models (Llama: 49, DeepSeek: 48, Qwen: 25 mentions)

-

Closed-Source LLMs: Show steady expansion (7 → 51 → 121 mentions) with 137% growth rate, reflecting market diversification:

- –

2023: Exclusively OpenAI models (GPT-3.5, GPT-4: 7 mentions)

- –

2024: GPT dominance continues (42 mentions) while competitors emerge (Claude: 5 mentions, Gemini: 1 mention)

- –

2025: Market expansion with new reasoning models (GPT-o1/o3) and stronger competition from Claude 3.5 and Gemini

(2) Architectural Preferences

Most employed LLMs adopt Decoder-only architectures, reflecting preference for autoregressive generation. However, some studies have explored Encoder-Decoder models (e.g., CodeT5+ [

47]), demonstrating architectural diversity. Additionally, Vision-Language Models (GPT-4V, LlaVa [

54]) are increasingly used for translating visual design specifications into Verilog code, indicating evolution toward multimodal input capabilities.

4.2. Analysis of Instruction Tuned LLMs

As shown in

Table 7, we identify 34 instruction-tuned (IT) LLMs specifically built for Verilog code generation. A defining feature of this ecosystem is its comparatively high level of openness: 19 models (55.9%) provide public weights while 15 (44.1%) remain closed. This open-weight ratio exceeds typical rates in general-purpose LLMs, reflecting a stronger community emphasis on reproducibility and downstream evaluability for hardware design research.

4.2.1. Foundation Model

Foundation model choices reveal a clear preference for code-specialized bases. In total, 82.4% (28/34) of IT LLMs adopt coding-oriented foundations, with three clusters standing out:

DeepSeek-Coder ecosystem: 32.4% market share (11 models) across variants (base, v2, R1-Distill), reflecting confidence in its code comprehension architecture

Qwen coder series: 26.5% adoption (9 models) combining CodeQwen and Qwen2.5-Coder, demonstrating rapid integration of Alibaba’s latest developments

CodeLlama variants: 23.5% usage (8 models), maintaining strong presence despite newer alternatives

The remaining 17.6% (6/34) of models (6/34) build upon general-purpose foundations, with Llama family leading adoption (4 models) and compact models (GPT-2, Phi-1.5B) demonstrating efficiency approaches. Notably, 20.6% of projects (7 models) experiment across multiple foundation models, indicating systematic evaluation approaches rather than single-model commitment.

4.2.2. Naming Patterns

Naming conventions further highlight research intent:

RTL-Centric Approaches: 5 models (14.7%) explicitly target Register Transfer Level abstraction (CraftRTL [

58], DeepRTL series [

59,

60], RTL++ [

66], RTLCoder [

80], OpenRTLSet [

64])

Verilog-Optimized Systems: 7 models (20.6%) employ “Veri-” prefixing (VeriCoder [

81], VeriGen [

82], VeriLogos [

83], VeriPrefer [

84], VeriReason [

85], VeriSeek [

86], VeriThoughts [

87]), emphasizing language-specific optimization

Reasoning-Enhanced Models: 4 models (11.8%) explicitly incorporate advanced reasoning (CodeV-R1 [

72], ReasoningV [

79], VeriReason [

85], VeriThoughts [

87]), reflecting emerging focus on complex logical inference

4.2.3. Trends Analysis

The current trajectory of IT LLMs for Verilog code generation exhibits three salient tendencies. First, development is consolidating around code-specialized foundations (e.g., DeepSeek-Coder, Qwen coding series, CodeLlama), alongside a sustained shift toward open weights. This configuration improves reproducibility and enables rigorous comparisons across studies.

In addition, there is a pronounced move toward explicit reasoning. Models that foreground multi-step inference (e.g., “R1-style” or “Reasoning/Thoughts” variants) aim to stabilize long-horizon logical chains and hierarchical design workflows, which better aligns with testbench-driven verification. Notwithstanding this emphasis, multi-base experimentation remains common, indicating that no single foundation dominates across all RTL tasks, datasets, and tool-chain settings.

4.3. Model Selection Insights

While our statistical analysis provides a comprehensive landscape of LLM adoption in Verilog code generation, translating these findings into actionable guidance for model selection represents a critical contribution to the different research scenarios (e.g., resource constraints, performance requirements, and research contexts).

For resource-constrained academic environments, open-source foundation models such as DeepSeek-Coder, Llama3.1, and Qwen2.5-Coder provide the optimal balance between performance, cost-effectiveness, and reproducibility. These models offer competitive Verilog generation capabilities while enabling local deployment and fine-tuning customization, though they require substantial computational infrastructure.

Performance-critical applications achieve best results with state-of-the-art closed-source models, particularly GPT variants and Claude variants. Despite higher operational costs and API dependencies, these models deliver superior generation quality and advanced reasoning capabilities essential for complex hardware design tasks. The sustained adoption of GPT-3.5 alongside newer models demonstrates that cost-performance considerations remain important across research contexts.

For domain-specific Verilog research, we recommend prioritizing the 19 available open-weight IT LLMs as foundational starting points. Among these, reasoning-enhanced variants (e.g., CodeV-R1 [

72], ReasoningV [

79], VeriReason [

85], VeriThoughts [

87]) merit particular attention, as their advanced reasoning capabilities address the increasingly complex logical inference requirements of modern hardware design challenges.

5. RQ2: Dataset and Evaluation Metrics for Verilog Code Generation

5.1. Dataset Construction

We categorize datasets for Verilog code generation into two complementary families: (1) Benchmark datasets for standardized evaluation, and (2) Instruct-tuning datasets for supervised fine-tuning and preference/reasoning augmentation.

5.1.1. Overview

Table 8 and

Table 9 provide a comprehensive overview of the Verilog code generation dataset landscape. In terms of benchmarking, our analysis reveals 18 open-source benchmarks compared to 9 closed-source alternatives (2023–2025), reflecting the research community’s commitment to reproducibility and transparent comparative evaluation. Similarly, in the instruction-tuning domain, open datasets (22 entries) also outnumber their closed-source items (12 entries), enabling standardized fine-tuning pipelines and consistent cross-method evaluation.

Across these datasets, we identify four design factors: input modality (Text vs. Text+Image vs. Text+Code), dataset availability (Open vs. Closed), testbench coverage (functional executability), and scale (ranging from tens to hundreds of thousands of samples). Although some researchers [

61,

88] have extracted raw Verilog corpora for pre-training

34, the field is mainly supported by carefully selected benchmarks for evaluation and structured instruction-style pairs for model training.

The following sections examine in detail the dataset construction methodologies and their associated quality assurance processes.

5.1.2. Benchmark Dataset Construction

(1) Data Sources

Benchmark datasets for Verilog code generation can be systematically categorized into four primary data sources based on their construction methodologies:

➀ Template Synthesis. Template synthesis utilizes systematic template construction to generate controlled datasets with parameterized descriptions and corresponding code templates.

For example,

DAVE [

9] first develops a structured template library containing paired English task templates and Verilog code templates with parameter placeholders, then populates these templates through systematic parameter conversion (e.g., mapping English “OR” to Verilog “|”).

Although this approach ensures quality control through its structured generation process, it inherently lacks the natural diversity present in real-world implementations [

113].

➁ Mining Software Repositories. Mining software repositories extracts code and problem statements from established educational platforms, public repositories, and community resources, leveraging verified solutions and comprehensive coverage.

VerilogEval [

57] draws entirely from HDLBits [

114], a Verilog learning platform, addressing multimodal elements like circuit diagrams and state graphs through two approaches:

VerilogEval-machine uses GPT-3.5-turbo for automated description generation, creating 143 valid problems, while

VerilogEval-human employs expert manual conversion to produce 156 high-fidelity problems.

VerilogEval-v2 [

108] builds on this foundation with hybrid collections combining HDLBits resources and manual curation, targeting code completion and specification-to-RTL tasks with optimized formats and in-context learning examples.

AutoChip [

96] similarly processes HDLBits data to develop executable benchmarks, refining 178 original problems to 120 code generation tasks and reconstructing testbenches by reverse engineering HDLBits’ testing logic before standardizing design prompts. In contrast,

RTL-repo-test [

102] uses GitHub API to collect from public repositories, applying filters for permissive licenses, creation dates after October 2023, and repositories containing 4-24 Verilog files, then systematically selecting files and target lines for prediction tasks.

➂ Expert Curated. Expert-curated datasets are developed by domain specialists who craft task specifications and reference implementations based on canonical designs, educational materials, and industrial best practices, typically featuring precise, unambiguous prompts and comprehensive testbenches.

Educational foundations appear in

VGV [

92] and

VeriGen_test [

88], which derive from course materials and HDLBits-style exercises, spanning from basic combinational logic to complex sequential circuits and finite state machines with graduated difficulty levels and expert-authored diagrams and testbenches, with VGV further incorporating visual prompt representations.

Standardized methodologies and broad module coverage characterize

RTLLM-v1/v2 [

21,

101] and

ChipGPTV [

97], which present comprehensive module taxonomies across arithmetic, logic/control, storage, and advanced categories. Complex hierarchical design challenges are addressed in

ModelEval [

95], CreativEval [

98],

Hierarchical [

100], and

ArchXBench [

103], which examine top-submodule structures, dependency graphs, timing constraints, and evaluation across diverse application domains.

Application-oriented benchmarks include

GEMMV [

73] and

CVDP [

104], with GEMMV offering 24 specialized tasks for AI accelerator cores evaluation, while CVDP provides comprehensive coverage across 13 task categories focused on design and verification scenarios, both emphasizing multi-scenario testing methodologies.

ResBench [

107] concentrates on real FPGA applications including machine learning acceleration, financial computing, and encryption, emphasizing resource optimization and application diversity. Specialized domain-specific accelerator evaluation is provided by

HiVeGen [

94], which employs LLM-based kernel analysis for application-driven parameter extraction, producing dataflow graphs and key attributes to guide design and verification processes.

➃ Hybrid Methods. Hybrid methods integrate multiple data sources, typically starting with open-source mining and then applying expert modifications, LLM-based synthesis, or other enhancement techniques to improve data quality and coverage.

Open-source mining combined with expert curation is demonstrated in

AutoSilicon [

93], which extract code from open-source repositories while incorporating expert-written prompts.

AutoSilicon targets industrial modules such as I/O controllers, processors, and accelerators, with expert-written specifications that follow RTLLM dataset description formats.

Multi-source integration is illustrated by

GenBen [

105], which combines silicon verification projects, textbooks, Stack Overflow discussions, and open-source hardware community resources through expert screening and organization into knowledge, design, debugging, and multimodal categories, featuring enhanced verification coverage and data perturbation techniques for contamination prevention and robustness improvement. Verified IP designs enhanced through expert optimization appear in

RealBench [

106], which draws from four verified open-source IP designs including OpenCores stable-stage AES encryption/decryption cores, SD card controllers, and open-source CPU cores such as Hummingbirdv2 E203, offering expert-written and optimized design specifications that ensure compliance with real engineering standards, complemented by 100% line coverage testbenches and formal verification processes for both module-level and system-level tasks.

LLM generation combined with human verification is exemplified by

VeriThoughts [

87], which integrates the MetRex dataset [

115] containing 25.8K synthesizable Verilog designs with LLM-generated prompts, reasoning trajectories, and candidate Verilog code using models such as Gemini and DeepSeek-R1, followed by formal verification and human sampling verification to ensure quality and correctness.

(2) Quality Assurance

Quality control for benchmark datasets centers on three complementary approaches that ensure dataset reliability and correctness.

➀ Expert Curation and Standardization. Expert curation and standardization eliminate ambiguity and enhance reproducibility: benchmarks incorporate expert-authored specifications and reviews, alongside unified artifacts that ensure consistent interfaces and evaluation (i.e., natural language description, testbench, and reference RTL) with standardized prompt/module-header formats or structured, annotated diagrams [

21,

88,

90,

92,

96,

97,

101,

104,

106].

➁ Testbench and Formal/Toolchain Checks. Testbench and formal/toolchain checks verify functional correctness. Solutions range from reverse-engineered testbenches where platform logic remains undisclosed [

96] to comprehensive coverage-driven or 100% line-coverage suites [

105,

106], hierarchical unit–integration testing [

100], and multi-scenario/boundary testing with explicit timing constraints [

95]. Formal methods address simulation limitations through equivalence checking and SAT-based proofs with self-consistency verification [

87,

106], while EDA pipelines deliver linting, synthesis, and PPA analysis to evaluate implementation viability (e.g., Verilator, Yosys, Design Compiler) [

70,

94].

➂ Contamination Control. Contamination control maintains the fairness of evaluation. Decontamination procedures against external corpora, static/dynamic perturbations with expert verification, multi-stage quality checks with LLM-judge filters, and structured failure taxonomies with detailed logs protect against data leakage and noise [

21,

104,

105,

106].

5.1.3. Instruct-Tuning Dataset Construction

(1) Data Sources

Instruct-tuning datasets for Verilog code generation can be systematically categorized into three primary data source strategies based on their construction methodologies:

➀ Mining Software Repositories. Similar to benchmark datasets, mining software repositories in instruct-tuning datasets exclusively collect data from public repositories, educational platforms, and community resources without relying on LLM-generated augmentation.

VeriGen_train [

88] demonstrates this methodology by integrating GitHub repository mining with educational resource extraction, processing 70 Verilog textbooks through OCR and text extraction to establish a comprehensive 400MB training corpus alongside GitHub-derived code modules.

VerilogDB [

109] and

RTL-repo [

102] expand this approach by incorporating multiple open-source channels including GitHub repositories, OpenCores hardware archives [

116], and academic resources, achieving broad coverage through structured database organization and detailed metadata extraction.

Although this methodology guarantees data authenticity and legal compliance, it necessitates substantial preprocessing to address quality variations and lacks the semantic consistency provided by LLM-generated descriptions.

➁ LLM Synthesis. LLM synthesis approaches produce training data entirely through language model capabilities, primarily utilizing instruction-following techniques and structured synthetic data generation strategies.

RTLCoder [

80,

111] implements this methodology through methodical keyword pool development and instruction generation, employing GPT-3.5 to create over 27,000 instruction-code pairs from a carefully selected vocabulary of 350 hardware design keywords spanning more than 10 circuit categories.

CraftRTL [

58] utilizes multiple LLM-based synthesis techniques including Self-Instruct, OSS-Instruct, and Docu-Instruct to develop 80.1k synthetic samples, addressing challenges with non-textual representations through advanced prompt engineering and structured generation protocols.

ScaleRTL [

68] employs DeepSeek-R1 for extensive reasoning trajectory generation, producing 3.5 billion token Chain-of-Thought datasets through automated specification development and multi-step reasoning synthesis.

While this methodology provides substantial scalability and consistent generation quality, it may not fully capture the diversity and practical complexity inherent in human-authored code.

➂ Hybrid Methods. Hybrid methods integrate open-source mining with LLM synthesis, typically starting with community-sourced code and then applying LLM-based enhancements for description generation, quality improvement, or data augmentation.

Open-source mining combined with LLM description generation is illustrated by

VerilogEval-train [

57], which extracts Verilog modules from GitHub repositories and uses GPT-3.5-turbo for automated problem description generation, creating 8,502 instruction-code pairs through systematic validation and quality filtering.

BetterV [

56] advances this approach by combining authentic GitHub-sourced Verilog data with LLM-synthesized virtual data, utilizing V2C translation tools and EDA verification to ensure functional correctness across all data sources.

MEV-LLM [

63] merges GitHub repository mining with ChatGPT-3.5-Turbo API for automated description generation, implementing tiered labeling strategies to create 31,104 classified samples across four complexity levels.

Multi-source integration with LLM enhancement is demonstrated by

AutoVCoder [

55], which collects 100,000 RTL modules from GitHub repositories while employing ChatGPT-3.5 for problem-code pair generation, implementing robust code filtering and correctness verification through Icarus Verilog and Python equivalence testing.

MG-Verilog [

76] combines repository mining with multi-granularity description generation using LLaMA2-70B-Chat and GPT-3.5-turbo, developing hierarchical descriptions from line-level comments to comprehensive summaries to support diverse learning objectives.

Origen [

78] implements code-to-code augmentation techniques, starting with open-source RTL libraries and leveraging Claude3-Haiku for description generation and code regeneration, with iterative compilation verification to guarantee functional correctness.

Expert knowledge integration with LLM synthesis is exemplified by

Haven [

75], which combines GitHub-sourced Verilog code with expert-curated examples from digital design textbooks and professional engineer annotations, utilizing GPT-3.5 for instruction optimization and logical enhancement to create knowledge-enriched and logic-enhanced datasets.

DeepRTL [

59] combines GitHub mining with proprietary industrial IP modules, employing GPT-4 for multi-granularity annotation through Chain-of-Thought methods while incorporating professional hardware engineer verification for industrial-grade accuracy, achieving 90% annotation precision through human evaluation validation.

(2) Quality Assurance

Quality control for instruct-tuning datasets converges on five complementary approaches that ensure training data reliability and optimize model performance.

➀ Syntax and Synthesizability Verification. Syntax and synthesizability verification confirms that training samples meet essential hardware design requirements through automated toolchain validation.

VeriGen_train [

88] utilizes Pyverilog for AST extraction and syntax validation, filtering modules to guarantee complete module-endmodule structures and proper port definitions.

AutoVCoder [

55] conducts comprehensive syntax checking via Icarus Verilog compilation, followed by Yosys synthesis verification to ensure code mappability to gate-level netlists, eliminating non-synthesizable constructs like

initial blocks and

$display statements.

VeriCoder [

81] extends this methodology by combining syntax validation with functional testing, using iverilog for compilation verification and automated testbench execution to ensure both syntactic correctness and behavioral validity.

DeepRTL [

59] performs CodeT5+ tokenizer compatibility checks, ensuring all modules fit within the 2048-token context window while preserving structural integrity through Pyverilog AST validation.

➁ Functional Correctness Verification. Functional correctness verification extends beyond syntax validation to confirm that generated code produces expected outputs through comprehensive testing and formal verification.

VeriCoder [

81] implements automated testbench generation using GPT-4o, creating unit tests with input stimuli and output assertions, then executing simulations through iverilog to verify functional equivalence between generated and reference implementations.

VeriThoughts [

87] applies formal equivalence checking using Yosys

miter commands and SAT solvers to verify that LLM-generated code produces identical outputs to reference implementations across all input combinations.

ReasoningV [

79] integrates simulation-based testing with boundary case analysis, generating comprehensive test vectors covering edge cases, reset scenarios, and error conditions for robust functional validation.

VeriPrefer [

84] employs coverage-driven testing through VCS tools, achieving over 90% line coverage and comprehensive assertion validation for thorough correctness assessment.

➂ Contamination Control. Contamination control safeguards dataset integrity by eliminating redundant samples and preventing data leakage from evaluation benchmarks.

PyraNet [

65] applies Jaccard similarity analysis on tokenized code sequences, removing samples with similarity scores above 0.9 to prevent model overfitting to redundant patterns.

CodeV [

71] implements MinHash-based deduplication with 128-dimensional vector mapping, calculating Jaccard similarity to filter duplicate files while maintaining dataset diversity.

VeriLogos [

83] addresses contamination through Rouge-L similarity analysis against public benchmarks (VerilogEval, RTLLM), removing samples with similarity scores exceeding 0.5 to prevent evaluation bias.

ScaleRTL [

68] utilizes 5-gram sequence analysis for contamination detection, comparing training samples against benchmark solutions to preserve evaluation integrity and prevent data leakage.

➃ Format Standardization and Length Control. Format standardization and length control establish consistent data representation and ensure compatibility with model training requirements.

Haven [

75] implements comprehensive format normalization, standardizing signal naming conventions (e.g.,

clk,

rst_n), module declaration structures, and indentation styles (4-space indentation) while removing redundant comments and preserving functional documentation.

OpenRTLSet [

64] applies CodeLlama tokenizer for length validation, truncating samples exceeding 8k tokens to prevent training context overflow while preserving code completeness.

VeriReason [

85] implements structured format control, standardizing specification descriptions (100-300 words), reasoning steps (150-300 words), and code segments (under 2048 tokens) to ensure consistent training input formatting.

RTL++ [

66] extends format standardization to multimodal data, ensuring consistent CFG/DFG text representation and maintaining structured instruction-code-graph triplets within model context boundaries.

➄ Quality Filtering and Human Validation. Quality filtering and human validation provide expert oversight to ensure annotation accuracy and domain-specific correctness.

PyraNet [

65] employs GPT-4o-mini for automated quality scoring (0-20 scale) based on coding style, efficiency, and standardization, with human validation by hardware engineers to verify score-quality consistency.

DeepRTL [

59] conducts multi-stage human validation, utilizing four professional Verilog designers for annotation accuracy assessment and three additional engineers for cross-validation, achieving 90% annotation accuracy through expert review.

VeriCoder [

81] combines automated filtering with human verification, engaging hardware engineers to validate specification-code consistency and testbench effectiveness, ensuring 92% functional correctness through expert evaluation.

Haven [

75] incorporates expert-curated examples from digital design textbooks and professional engineer annotations, implementing knowledge-enhanced and logic-enhanced dataset construction with domain expert validation for engineering practice compliance.

These quality assurance mechanisms collectively ensure that instruct-tuning datasets deliver reliable, diverse, and functionally correct training supervision, enabling effective model fine-tuning while preserving evaluation integrity and preventing common issues such as data leakage, annotation errors, and functional inconsistencies.

5.1.4. Trends Analysis

We analyze three key evolutionary aspects of datasets and their implications for evaluation methodology: (1) testbench availability as an indicator of executability, (2) input modality as benchmarks extend beyond text-only specifications, and (3) dataset scale as applications range from reasoning-focused micro-suites to comprehensive coverage collections. Based on these trends, we formulate actionable recommendations for future dataset development that better align training supervision with executable evaluation and downstream tasks.

(1) Testbench availability

Executable verification has become the standard approach for evaluation. Among open benchmarks, 16 of 18 include testbenches (with exceptions being RTLRepo_test, which focuses on line-level generation, and VeriThoughts, which employs formal equivalence via Yosys rather than simulation). In the closed-source category, all datasets except DAVE_test provide testbenches. By contrast, most instruct-tuning datasets lack testbenches; only select examples (e.g., VeriCoder-Origen, VeriCoder-RTLCoder, VeriReason-Data) incorporate executable verification. This disparity highlights the critical need for executable supervision in training protocols (including testbenches, formal specifications, and synthesis-driven feedback).

(3) Dataset scale

Dataset dimensions diverge according to purpose. Benchmarks span from focused micro-scale collections (4–30 items) that emphasize logical reasoning and specification fidelity, to comprehensive mid/large-scale resources (e.g., CVDP: 783; GenBen: 324) that prioritize coverage and diversity. Instruction-tuning resources, conversely, range from specialized compact sets (e.g., CodeV-R1-Data) to extensive corpora (reaching hundreds of thousands to million-scale samples; e.g., AutoVCoder-Data, PyraNet). The former sharpen reasoning capabilities and alignment, while the latter facilitate broad generalization despite less rigorous executable validation. This complementary relationship between compact, high-signal benchmarks and extensive, weakly-validated training sets reflects broader methodological patterns in code-oriented language models.

Based on these observations, future dataset development should prioritize: (1) early integration of

executable supervision (testbenches, formal specifications, synthesis signals) to reduce the gap between supervision and evaluation; (2) stronger

multimodal alignment between training and evaluation (e.g., diagrams, specification sheets) as benchmarks incorporate visual artifacts; (3)

reasoning-enhanced training that explicitly incorporates intermediate reasoning steps and design decision processes into fine-tuning datasets (as seen in recent efforts like CodeV-R1 [

72], VeriReason [

85], ScaleRTL [

68], and VeriThoughts [

87]) to develop models that can articulate design rationales and tackle complex hardware design problems with transparent, verifiable reasoning.

5.2. Evaluation Metrics

Assessing the quality of LLM-generated Verilog code poses substantial challenges, requiring thorough evaluation of both syntactic validity and semantic correctness. To address these assessment requirements systematically, researchers have developed diverse evaluation methodologies that can be organized into three fundamental categories:

5.2.1. Similarity-Based Metrics

Similarity-based evaluation metrics assess generated Verilog code quality by comparing structural or textual similarity scores between generated code and reference implementations without executing the code.

(1) General-Purpose Metrics

The majority of evaluation approaches utilize established text similarity metrics adapted from natural language processing and general code evaluation frameworks, including:

Exact Match: Evaluates complete correspondence between generated and reference code, providing binary correctness assessment [

67,

102]

Edit Distance Metrics: Quantify minimal character-level modifications needed for alignment, including Levenshtein distance [

67,

102] and Ratcliff-Obershelp similarity [

9]

N-gram Based Metrics: Assess sequence overlap through established measures such as BLEU [

60,

104,

112,

117], METEOR [

60,

112], ROUGE [

60,

112,

117], and chrF [

117] scores, originally developed for machine translation evaluation

These metrics provide notable advantages including computational efficiency and straightforward implementation.

(2) Verilog-Specific Metrics

Traditional general-purpose metrics cannot adequately capture domain-specific semantics inherent in hardware description languages. To address this limitation, researchers developed SimEval [

118], a specialized metric operating at three complementary levels: (1)

Syntactic analysis using Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) extraction via PyVerilog for structural assessment; (2)

Semantic analysis employing Control Flow Graph (CFG) analysis through Verilator to identify execution paths; and (3)

Functional analysis utilizing gate-level netlist comparison via Yosys synthesis for implementation equivalence.

5.2.2. Execution-Based Metrics

Execution-based evaluation metrics assess generated Verilog code quality through comprehensive compilation and runtime verification, providing assessment of functional correctness and hardware implementation efficiency.

(1) Correctness Assessment

The fundamental execution-based evaluation focuses on verifying code functionality through compilation and behavioral testing, including:

Syntax-pass@k: Quantifies the proportion of generated code samples that successfully compile without syntax errors across k attempts

Functional-pass@k: Determines behavioral correctness by executing generated modules against standardized testbenches with predefined expected outputs

Formal-Verification: Establishes equivalence between generated code and reference implementations using formal methods via "Yosys -equiv"

(2) Hardware Quality Metrics

Beyond fundamental correctness, researchers increasingly evaluate hardware implementation quality through comprehensive PPA (Power, Performance, Area) analysis:

Power: Measures energy efficiency of synthesized designs

Performance: Analyzes timing characteristics including maximum operating frequency, critical path delays, and latency metrics

Area: Quantifies resource utilization efficiency in terms of logic gates, flip-flops, memory elements, and overall silicon footprint

5.2.3. LLM-Based Metrics

LLM-based evaluation metrics utilize the reasoning capabilities of language models to assess code quality, capturing semantic understanding and domain-specific knowledge beyond traditional similarity-based techniques.

(1) Model Confidence Metrics

These metrics analyze the internal confidence of language models during code generation:

Perplexity: Quantifies model certainty in generated Verilog code [

74,

117]

(2) LLM-as-a-Judge

These methodologies employ language models as expert evaluators to assess multiple dimensions of code quality:

GPT Score: Utilizes GPT-family models as evaluators to assess code quality across multiple dimensions including readability, correctness, and design best practices [

59,

60]

VCD-RNK: Evaluates semantic consistency between natural language specifications and generated code implementations, implementing knowledge distillation techniques to develop efficient lightweight models capable of assessing functional [

119]

MetRex: Utilizes language models as expert evaluators to predict the PPA of generated Verilog code [

115]

5.2.4. Metrics Trends Analysis

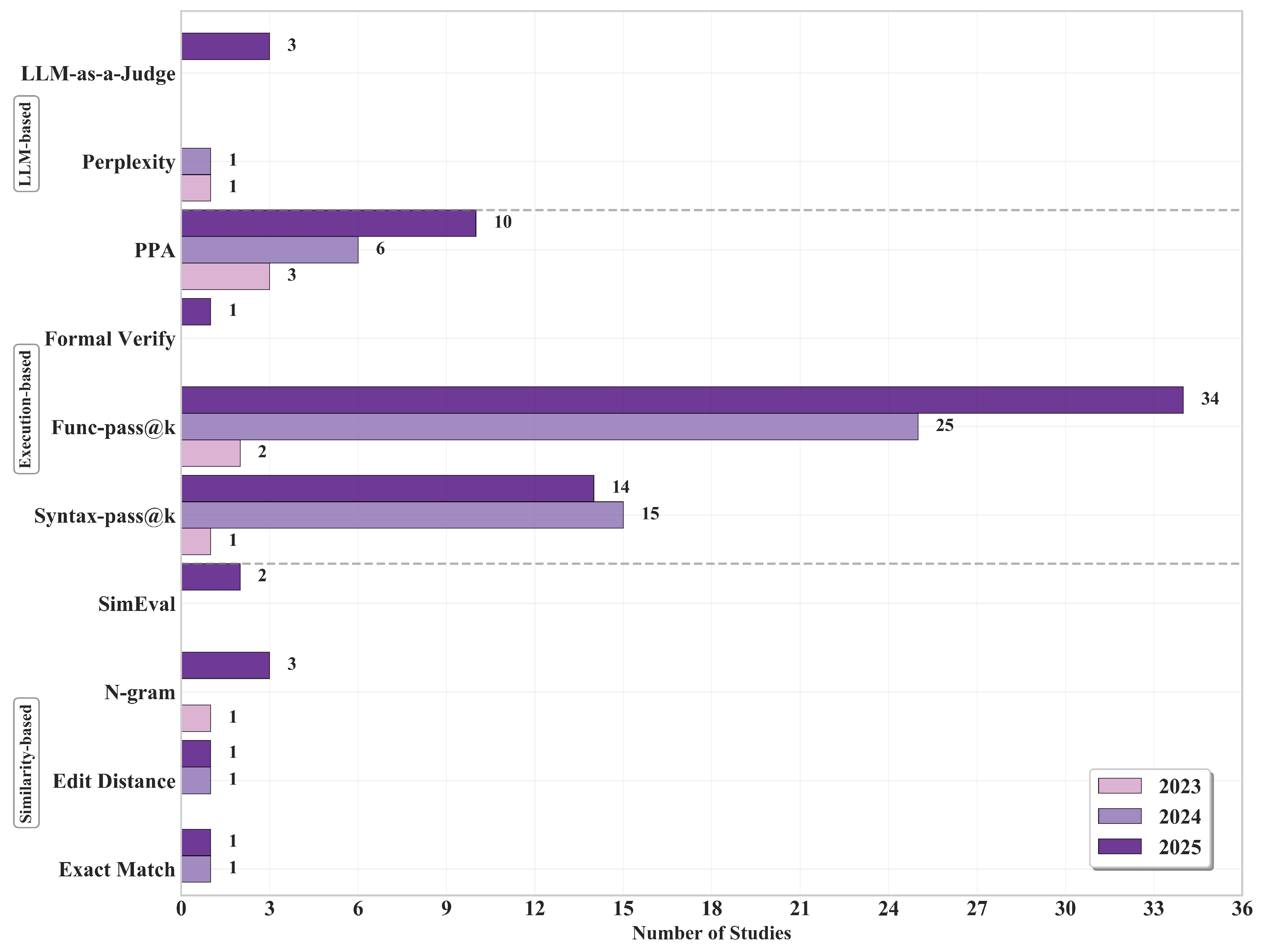

As illustrated in

Figure 7, evaluation methodologies from 2023 to 2025 demonstrate a clear evolution.

(1) Execution-based metrics

Execution-based metrics have become primary: functional-pass@k shows substantial growth from 2 instances (2023) to 25 (2024) and 34 (2025), while syntax-pass@k increases from 1 (2023) to 15 (2024), maintaining significant presence with 14 instances in 2025. Hardware quality assessment steadily gains importance, with PPA measurements increasing from 3 (2023) to 6 (2024) and 10 (2025), highlighting the research community’s growing emphasis on implementation feasibility beyond basic functional correctness. Formal equivalence verification has only recently entered mainstream adoption (formal verification: 1 instance in 2025), largely facilitated by improvements in verification tool-chain maturity.

(2) Similarity-based metrics

Similarity-based measures continue to exist but increasingly serve supplementary functions. N-gram metrics display modest variation (1 → 0 → 3), while Exact Match and Edit Distance maintain minimal presence (0/0 in 2023, followed by 1/1 in both 2024 and 2025), highlighting their inherent limitations in capturing RTL semantic structures. By contrast, the Verilog-specific metric SimEval emerges in 2025 (2 instances), indicating growing recognition of the need for specialized metrics that effectively integrate syntax analysis, control/data flow evaluation, and functional equivalence verification.

(3) LLM-based metrics

LLM-based evaluation represents an emerging complementary approach. While use of Perplexity gradually diminishes (1 → 1 → 0), LLM-as-a-Judge appears in 2025 (3 instances), indicating a transition from basic confidence measures toward sophisticated, task-aware evaluations capable of assessing readability, specification alignment, and design best practices beyond the capabilities of traditional text similarity metrics.

Based on these observations, future metrics development should prioritize: (1) standardized benchmark integration with execution-based metrics to ensure consistent, reproducible evaluation across research efforts; (2) hardware-specific evaluation frameworks that directly measure downstream design objectives beyond functional correctness, such as PPA optimization; (3) LLM-as-a-Judge frameworks as a promising research direction, particularly for evaluating semantic correctness of generated Verilog code without reference implementations.

6. RQ3: Adaptation and Optimization Techniques for Verilog Code Generation

Having established the foundational datasets and evaluation methodologies in the previous sections, we now examine the diverse adaptation and optimization techniques employed to enhance LLMs for Verilog code generation. These techniques can be broadly categorized into training-free and training-based approaches, each offering distinct advantages and trade-offs in terms of computational efficiency and performance gains.

6.1. Training-Free Methods

Training-free methods provide immediate applicability without requiring additional model training, making them particularly attractive for practitioners with limited computational resources.

6.1.1. EDA-Tool Feedback

EDA-tool feedback represents a critical advancement in LLM-based Verilog generation, where EDA tools provide concrete error diagnostics and performance metrics to guide iterative code refinement. Unlike approaches relying solely on LLM self-correction or testbench outputs, EDA-tool feedback leverages industry-standard verification and synthesis tools to capture syntax errors, functional mismatches, timing violations, and PPA metrics. This feedback mechanism creates a closed-loop optimization system where tool-generated diagnostics inform subsequent LLM refinement iterations, progressively improving code quality from syntactic correctness to physical implementation feasibility.

Based on the architectural design of the feedback loop, we categorize these approaches into single-agent systems and multi-agent systems.

(1) Single-Agent Systems

Single-agent systems employ a unified LLM instance that processes EDA tool feedback and iteratively refines Verilog code through self-correction mechanisms, integrating multiple feedback sources into cohesive prompt engineering strategies.

Several approaches implement hierarchical optimization stages with progressive feedback integration. VeriPPA [

133] introduces dual-stage optimization combining iverilog simulator feedback for syntax/functional correctness (

) with Synopsys Design Compiler PPA reports for power-performance-area optimization through VeriRectify module exploration of pipelining, clock gating, and parallel operations. The LLM-Powered RTL Assistant [

138] implements automatic prompt engineering mimicking human designer workflows through three prompt types: initial prompts establishing “professional Verilog designer” roles with step-by-step planning, self-verification prompts guiding testbench generation and behavioral analysis, and self-correction prompts integrating Icarus Verilog error logs.

RTLFixer [

139] specifically targets syntax errors through ReAct prompting with “think-act-observe” iterative cycles combining compiler feedback and RAG-based human expert knowledge retrieval. Paradigm-Based HDL Generation [

137] emulates human expert design through structured task decomposition using three paradigm blocks: COMB blocks extract truth tables simplified by PyEDA to Sum-of-Products expressions; SEQU blocks construct state transition tables guiding “three-always-block” generation; BEHAV blocks decompose complex tasks into behavioral components.

EvoVerilog [

140] integrates LLM reasoning with evolutionary algorithms through thought tree initialization and four specialized offspring operators for design space exploration. Non-dominated sorting implements multi-objective optimization balancing testbench mismatch minimization and hardware resource reduction, identifying Pareto-optimal solutions across iterations. VGV [

92] leverages MMLLMs to generate Verilog from circuit diagrams through two visual prompting strategies: Basic Visual (BV) mode for direct diagram-to-code conversion and Thinking Visual (TV) mode requiring two-stage component description before generation.

These single-agent approaches demonstrate significant advancements in automated Verilog generation through systematic integration of EDA tool feedback, achieving substantial improvements in code quality, functional correctness, and design optimization.

(2) Multi-Agent Systems

Multi-agent systems employ multiple specialized LLM instances that collaborate through structured communication protocols and role-based task distribution, leveraging collective intelligence to address complex Verilog generation challenges through coordinated EDA tool feedback processing.

Several frameworks implement basic two-agent architectures with complementary roles. AIVRIL [

142] establishes a dual-loop optimization system with Code Agent generating RTL code and testbenches while Review Agent analyzes compilation logs for structured correction feedback, achieving AutoReview (syntax verification) and AutoDV (functional verification) cycles with tool/LLM agnostic design supporting Claude 3.5 Sonnet, GPT-4o, and Llama3 70B. The LLM-aided Front-End Framework [

89] deploys three task-specific LLMs in sequential collaboration:

generates RTL from specifications,

constructs corresponding testbenches, and

performs design review based on behavioral simulation results. RTL Agent [

143] implements Generator-Reviewer architecture inspired by Reflexion technology, improving the performance of GPT-4o-mini/GPT-4o through iterative “generation-test-reflection” cycles with cost-performance trade-off analysis favoring parallel width over iterative depth.

Advanced frameworks employ domain-specific agent specialization with sophisticated coordination mechanisms. MAGE [

144] introduces four-agent collaboration: Testbench Generator optimizing text waveform output, RTL Generator with syntax checking, Judge Agent for simulation evaluation and scoring, and Debug Agent for iterative refinement, employing high-temperature sampling with Top-K candidate selection and normalized mismatch scoring for up to 5 syntax error iterations. VerilogCoder [

145] integrates Task Planning with Task-Circuit Relationship Graph (TCRG) decomposition, Code Agent with Verification Assistant for syntax consistency, and Debug Agent utilizing three EDA tool types: Icarus Verilog syntax checker, Verilog simulator for VCD generation, and novel AST-based waveform tracing tool through Pyverilog for signal backward tracing and mismatch localization. CoopetitiveV [