Submitted:

09 November 2025

Posted:

10 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

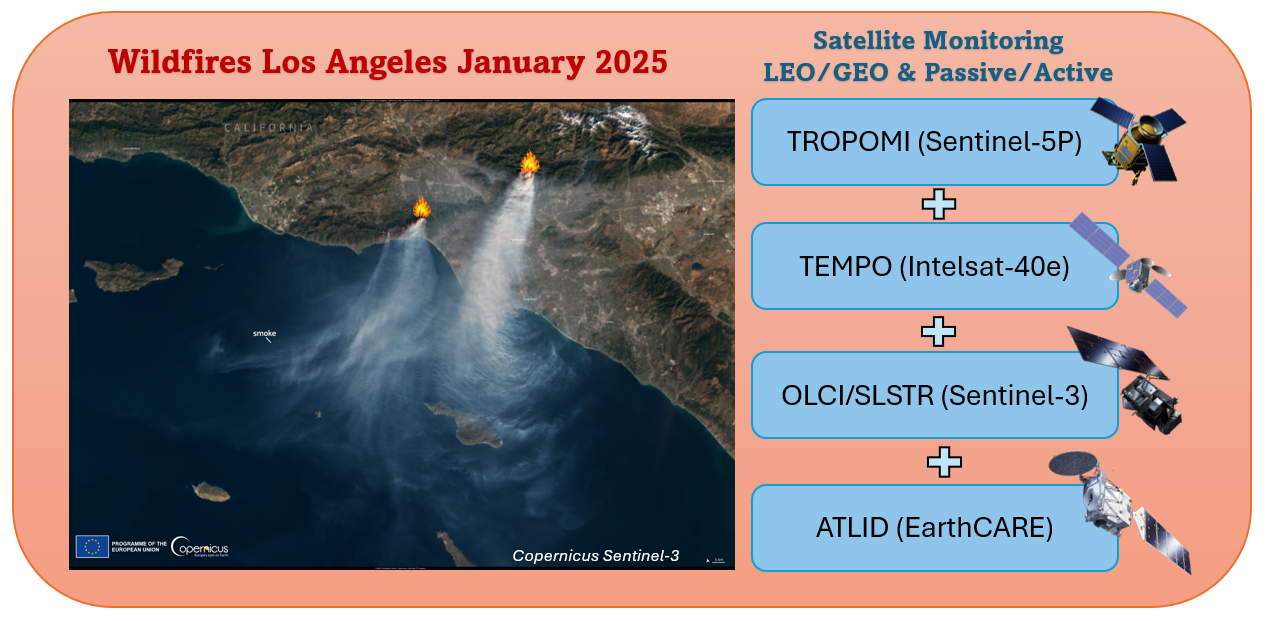

1. Introduction

2. Datasets and Methodology

2.1. Satellite Observations

2.1.1. Tropospheric Emissions Monitoring of Pollution (TEMPO)

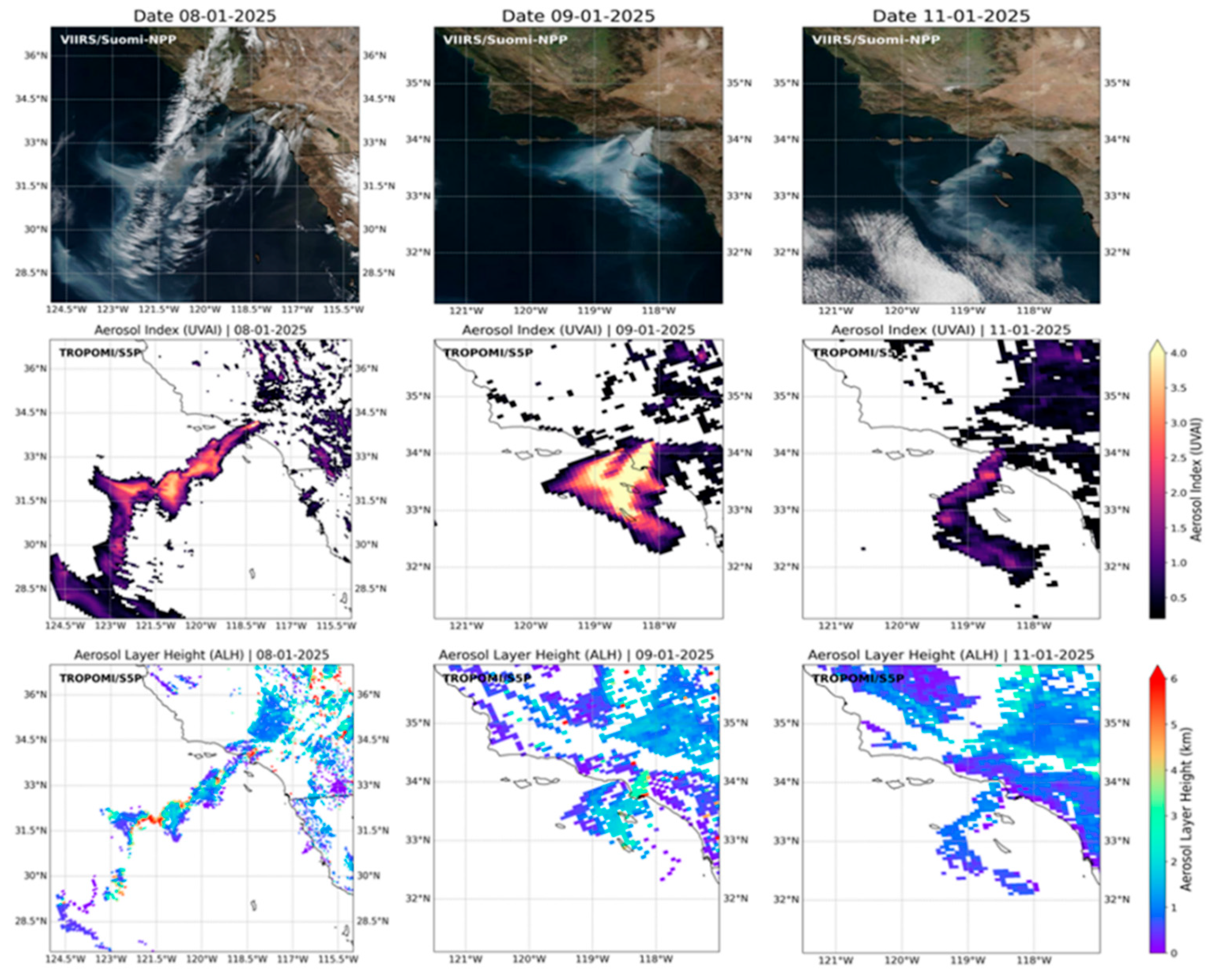

2.1.2. TROPOspheric Monitoring Instrument (TROPOMI)

TROPOMI/S5P Trace Gases Observations

TROPOMI/S5P Aerosol Observations

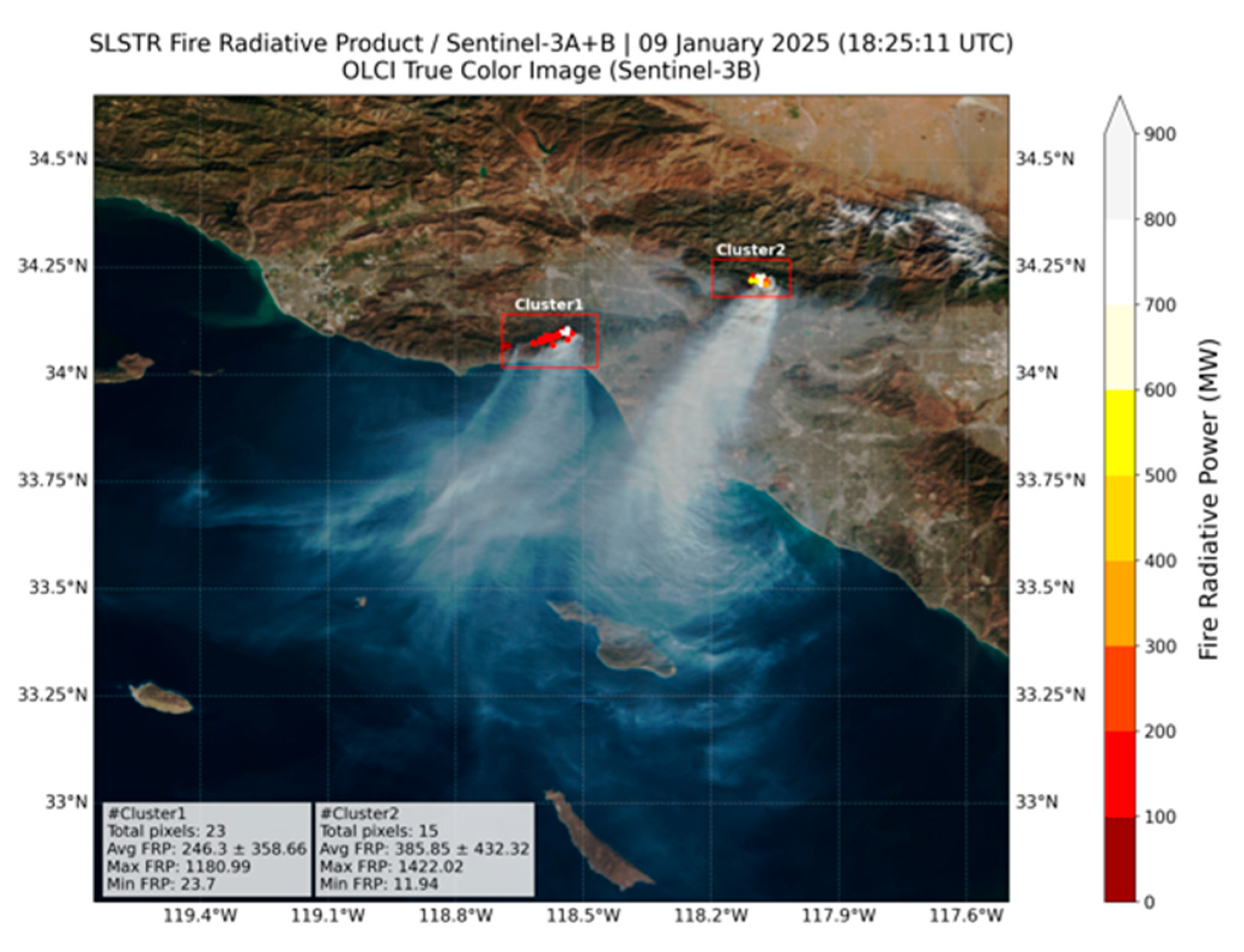

2.1.3. Fire Radiative Power from Sentinel-3 Polar-Orbiting Satellites

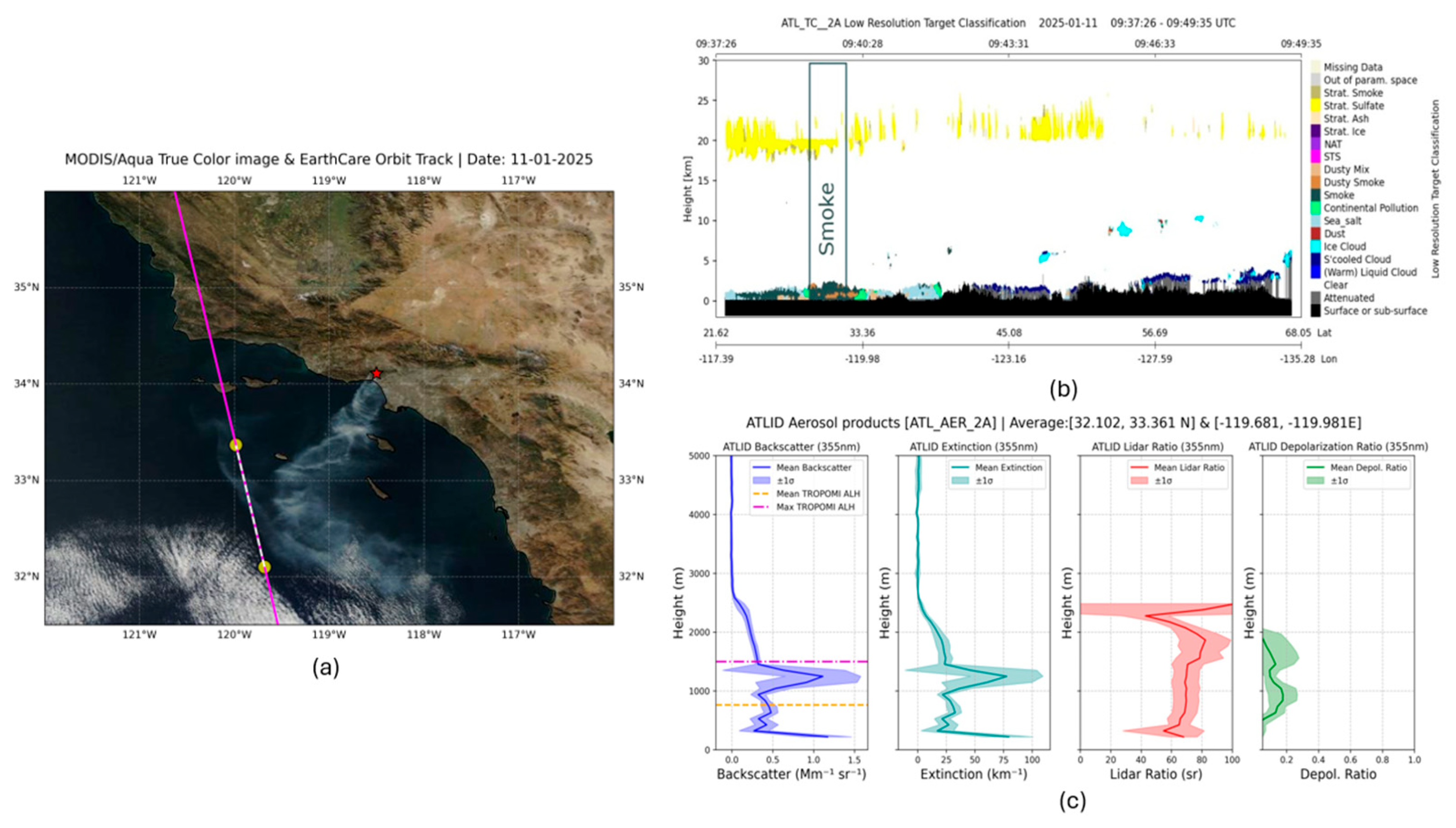

2.1.4. ATmospheric LIDar (ATLID) Instrument Observations

3. Results and Discussion

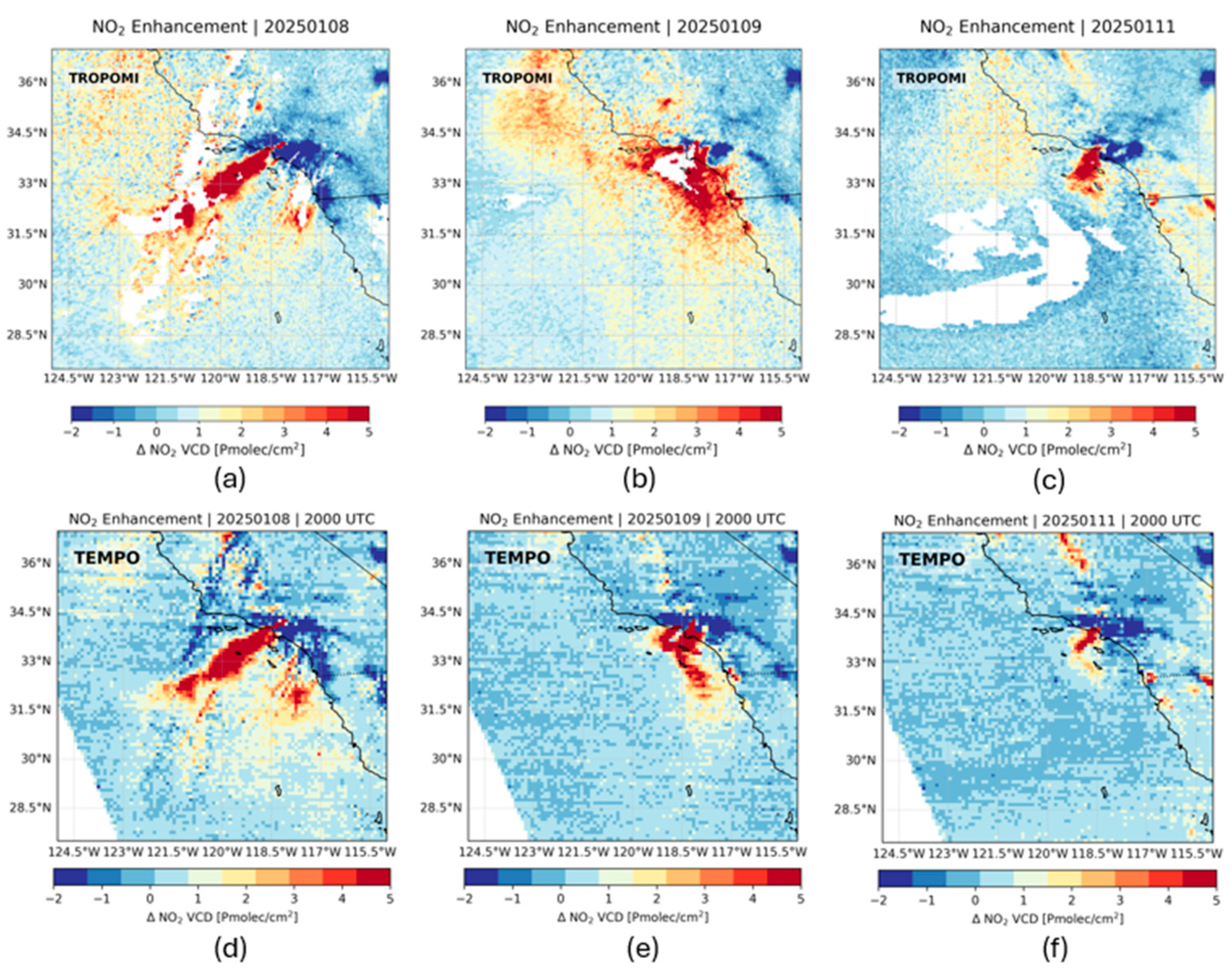

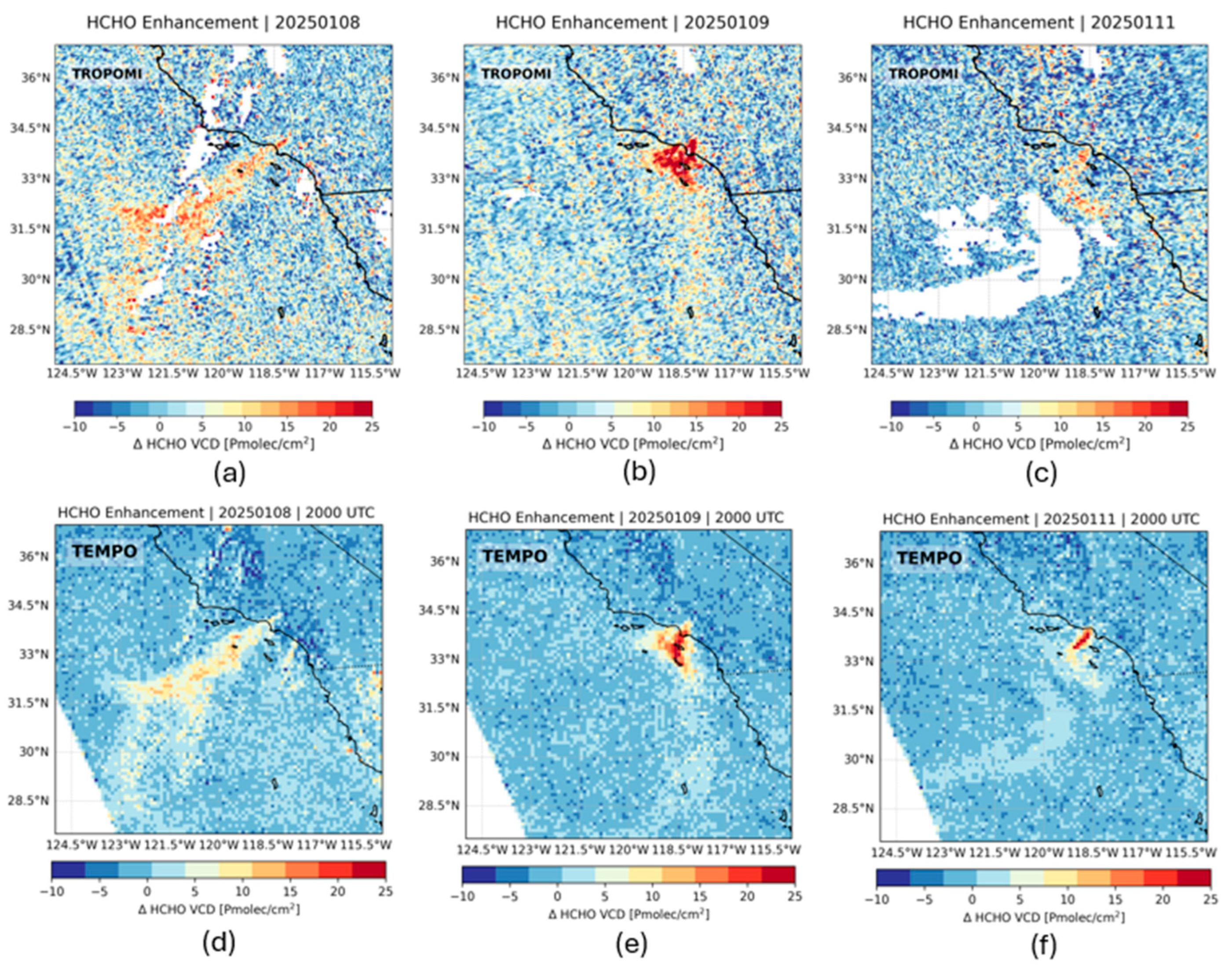

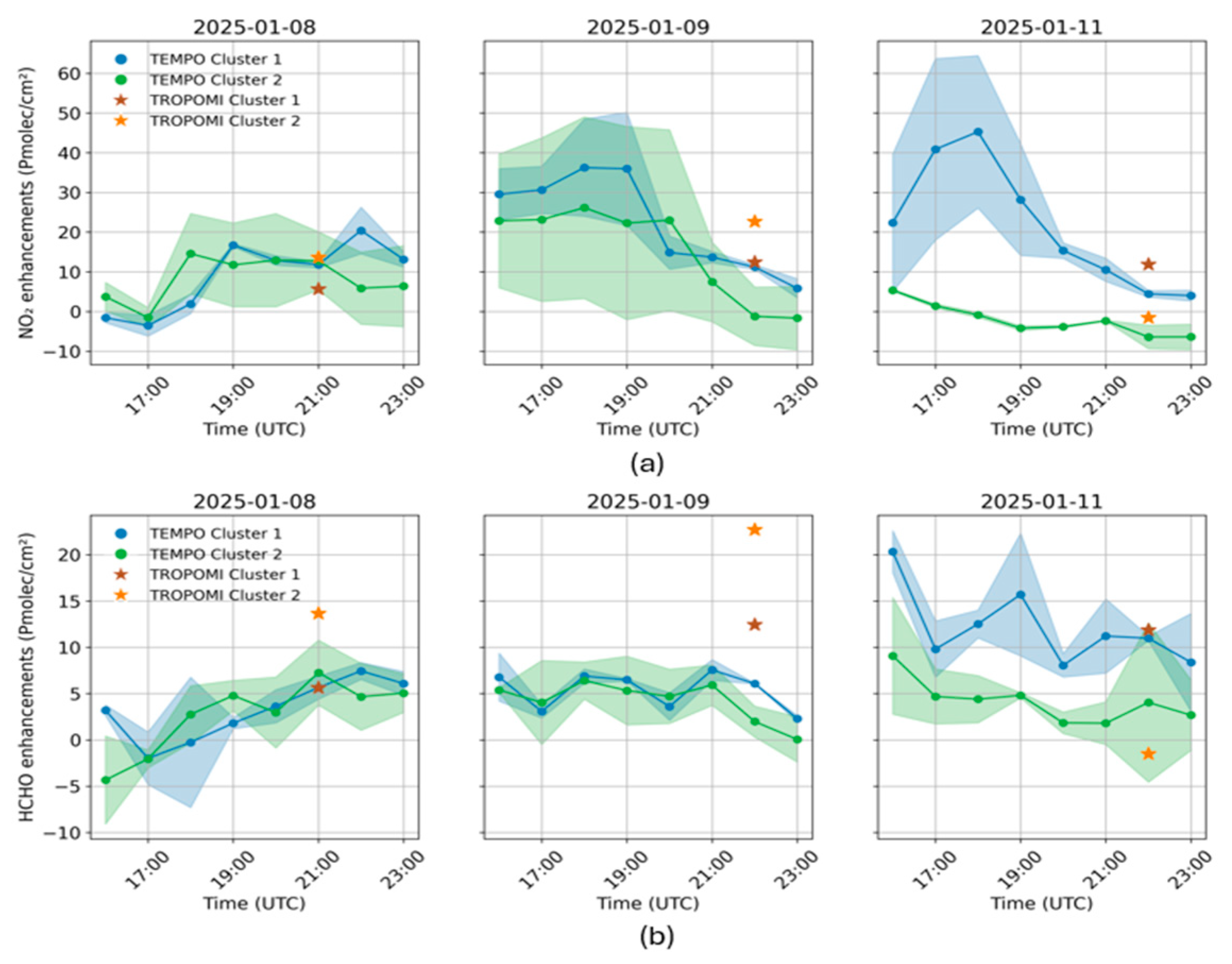

TROPOMI and TEMPO Tropospheric Gases Monitoring

4. Summary and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Keeley Jon E., Flannigan Michael, Brown Tim J., Rolinski Tom, Cayan Daniel, Syphard Alexandra D., Guzman-Morales Janin, Gershunov Alexander: Climate and weather drivers in southern California Santa Ana Wind and non-Santa Wind fires. International Journal of Wildland Fire 33, WF23190, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Billmire Michael, French Nancy, H. F., Loboda Tatiana, Owen R. Chris, Tyner Marlene (2014) Santa Ana winds and predictors of wildfire progression in southern California. International Journal of Wildland Fire 23, 1119-1129. [CrossRef]

- Wan, N.; Xiong, X.; Kluitenberg, G. J., Hutchinson, J. M. S., Aiken, R., Zhao, H., and Lin, X.: Estimation of biomass burning emission of NO₂ and CO from 2019–2020 Australia fires based on satellite observations, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 23, 711–724, 2023. [CrossRef]

- van der Velde, I. R., van der Werf, G. R., Houweling, S., Eskes, H. J., Veefkind, J. P., Borsdorff, T., and Aben, I.: Biomass burning combustion efficiency observed from space using measurements of CO and NO₂ by the TROPOspheric Monitoring Instrument (TROPOMI), Atmos. Chem. Phys., 21, 597–616, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Koukouli, M.-E.; Pseftogkas, A.; Karagkiozidis, D.; Mermigkas, M.; Panou, T.; Balis, D. and Bais, A. (2025). Extreme wildfires over Northern Greece during Summer 2023 – Part B. Adverse effects on regional air quality. Atmospheric Research, [online] p.108034. [CrossRef]

- Magro, C.; Nunes, L.; Gonçalves, O.C.; Neng, N.R.; Nogueira, J.M.F.; Rego, F.C.; Vieira, P. Atmospheric Trends of CO and CH4 from Extreme Wildfires in Portugal Using Sentinel-5P TROPOMI Level-2 Data. Fire. 2021; 4(2):25. [CrossRef]

- Filonchyk, M.; Peterson, M.P. and Sun, D. (2022). Deterioration of air quality associated with the 2020 US wildfires. Science of The Total Environment, 826, p.154103. [CrossRef]

- Michailidis, K.; Garane, K.; Karagkiozidis, D.; Peletidou, G.; Voudouri, K.-A.; Balis, D. and Bais, A. (2024). Extreme wildfires over northern Greece during summer 2023 – Part A: Effects on aerosol optical properties and solar UV radiation. Atmospheric Research, [online] 311, p.107700. [CrossRef]

- Zoogman, P.; Liu, X.; Suleiman, R.; Pennington, W.; Flittner, D.; Al-Saadi, J. et al. (2017). Tropospheric Emissions: Monitoring of Pollution (TEMPO). Journal of Quantitative Spectroscopy and Radiative Transfer, 186, 17–39. [CrossRef]

- Burrows, J. P., Weber, M., Buchwitz, M., Rozanov, V., Ladstätter-Weißenmayer, A., Richter, A., DeBeek, R., Hoogen, R., Bramstedt, K., Eichmann, K.-U., Eisinger, M., & Perner, D. (1999). The Global Ozone Monitoring Experiment (GOME): Mission Concept and First Scientific Results. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences, 56(2), 151–175.

- Bovensmann, H.; Burrows, J. P., Buchwitz, M., Frerick, J., Noël, S., Rozanov, V. V., Chance, K. V., & Goede, A. P. H. (1999). SCIAMACHY: Mission Objectives and Measurement Modes. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences, 56(2), 127–150.

- Levelt, P. F., Joiner, J., Tamminen, J., et al. (2018). The Ozone Monitoring Instrument: overview of 14 years in space. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 18(8), 5699-5745. [CrossRef]

- Munro, R.; Lang, R.; Klaes, D.; Poli, G.; Retscher, C.; Lindstrot, R.; Huckle, R.; Lacan, A.; Grzegorski, M.; Holdak, A.; Kokhanovsky, A.; Livschitz, J.; Eisinger, M. (2016). The GOME-2 instrument on the Metop series of satellites: Instrument design, calibration, and level 1 data processing—An overview. Atmospheric Measurement Techniques, 9(3), 1279–1301. [CrossRef]

- Flynn, L.; Long, C.; Wu, X.; Evans, R.; Beck, C. T., Petropavlovskikh, I., McConville, G., Yu, W., Zhang, Z., Niu, J., Beach, E., Hao, Y., Pan, C., Sen, B., Novicki, M., Zhou, S., & Seftor, C. (2014). Performance of the Ozone Mapping and Profiler Suite (OMPS) products. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 119, 6181–6195. [CrossRef]

- Veefkind, J. P., Aben, I., McMullan, K., et al., (2012). TROPOMI on the ESA Sentinel-5 Precursor: A GMES mission for global observations of the atmospheric composition for climate, air quality and ozone layer applications. Remote Sensing of Environment, 120, 70-83. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Jeong, U.; Ahn, M. H., Kim, J. H., Park, R. J., Lee, H., Song, C. H., Choi, Y. S., Lee, K. H., Yoo, J. M., Jeong, M. J., Park, S. K., Lee, K. M., Song, C. K., Kim, S. W., Kim, Y. J., Kim, S. W., Kim, M., Go, S., … Choi, Y. (2020). New era of air quality monitoring from space: Geostationary environment monitoring spectrometer (GEMS). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 101(1), E1–E22. [CrossRef]

- Nowlan, C. R., González Abad, G., Liu, X., Wang, H., & Chance, K. (2025). TEMPO Nitrogen Dioxide Retrieval Algorithm Theoretical Basis Document. NASA Algorithm Publication Tool. [CrossRef]

- González Abad G., Caroline Nowlan, Huiqun (Helen) Wang, Heesung Chong, John Houck, Xiong Liu and Kelly Chance, TROPOSPHERIC EMISSIONS: MONITORING OF POLLUTION (TEMPO) PROJECT, Trace Gas and Cloud Level 2 and 3 Data Products User Guide, December 9, 2024, version 1.2, TEMPO_Level-2-3_trace_gas_clouds_user_guide_V1.2.pdf, last access: 12.03.2025.

- González Abad, G.; Nowlan, C. R., Liu, X., Wang, H., & Chance, K. (2025), TEMPO Formaldehyde Retrieval Algorithm Theoretical Basis Document, NASA Algorithm Publication Tool. [CrossRef]

- van Geffen, J.; Eskes, H.; Compernolle, S.; Pinardi, G.; Verhoelst, T.; Lambert, J.-C.; Sneep, M.; ter Linden, M.; Ludewig, A.; Boersma, K. F., and Veefkind, J. P.: Sentinel-5P TROPOMI NO₂ retrieval: impact of version v2.2 improvements and comparisons with OMI and ground-based data, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 15, 2037–2060, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Vigouroux, C.; Langerock, B.; Bauer Aquino, C. A., Blumenstock, T., De Mazière, M., De Smedt, I., Grutter, M., Hannigan, J., Jones, N., Kivi, R., Lutsch, E., Mahieu, E., Makarova, M., Metzger, J. M., Morino, I., Murata, I., Nagahama, T., Notholt, J., Ortega, I., Palm, M., Pinardi, G., Röhling, A., Smale, D., Stremme, W., Strong, K., Sussmann, R., Té, Y., van Roozendael, M., Wang, P., and Winkler, H.: TROPOMI/S5P formaldehyde validation using an extensive network of ground-based FTIR stations, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 13, 3751–3767, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Landgraf, J., aan de Brugh, J., Scheepmaker, R., Borsdorff, T., Hu, H., Houweling, S., Butz, A., Aben, I., and Hasekamp, O.: Carbon monoxide total column retrievals from TROPOMI shortwave infrared measurements, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 9, 4955–4975, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Lorente, A.; Borsdorff, T.; Martinez-Velarte, M. C., Butz, A., Hasekamp, O. P., Wu, L., and Landgraf, J.: Evaluation of the methane full-physics retrieval applied to TROPOMI ocean sun glint measurements, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 15, 6585–6603, 2022. [CrossRef]

- de Graaf, M.; Sneep, M.; ter Linden, M.; Tilstra L. G., Donovan, D. P., van Zadelhoff, G.-J., and Veefkind, J. P.: Improvements in aerosol layer height retrievals from TROPOMI oxygen A-band measurements by surface albedo fitting in optimal estimation, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 18, 2553–2571, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Lambert, J.-C. A. Keppens, S. Compernolle, K.-U. Eichmann, M. de Graaf, D. Hubert, B. Langerock, M.K. Sha, E. van der Plas, T. Verhoelst, T. Wagner, C. Ahn, A. Argyrouli, D. Balis, K.L. Chan, M. Coldewey-Egbers, I. De Smedt, H. Eskes, A.M. Fjæraa, K. Garane, J.F. Gleason, J. Granville, P. Hedelt, K.-P. Heue, G. Jaross, M.E. Koukouli, E. Loots, R. Lutz, M.C Martinez Velarte, K. Michailidis, A. Pseftogkas, S. Nanda, S. Niemeijer, A. Pazmiño, G. Pinardi, A. Richter, N. Rozemeijer, M. Sneep, D. Stein Zweers, N. Theys, G. Tilstra, C. Topaloglou, O. Torres, P. Valks, J. van Geffen, C. Vigouroux, P. Wang, and M. Weber, Quarterly Validation Report of the Copernicus Sentinel-5 Precursor Operational Data Products #28: April 2018 – August 2025, S5P MPC Routine Operations Consolidated Validation Report series, Issue #28, Version 28.00.00, 227 pp., 15 September 2025. https://mpc-vdaf.tropomi.eu/ProjectDir/reports//pdf/S5P-MPC-IASB-ROCVR-28.00.00_FINAL_signed-jcl-AD.pdf last access: 04.11.2025.

- Eskes, H.; Jos van Geffen Folkert Boersma Kai-Uwe Eichmann Arnoud Apituley Mattia Pedergnana Maarten Sneep, J. Pepijn Veefkind, and Diego Loyola, Sentinel-5 precursor/TROPOMI Level 2 Product User Manual, S5P-KNMI-L2-0021-MA, CI-7570-PUM, 4.4.0, 2024-11-08. https://sentiwiki.copernicus.eu/web/s5p-products last access: 31 March 2025.

- Romahn, F., Pedergnana, M., Loyola, D., Apituley, D., Sneep, M., Veefkind, P., Sentinel-5 precursor/TROPOMI Level 2 Product User Manual Formaldehyde HCHO, Report S5P-L2-DLR-PUM-400F, version v.02.04.00, ESA, 2022. https://sentinel.esa.int/documents/247904/2474726/Sentinel-5P-Level-2-Product-User-Manual-Formaldehyde (last accessed on February 20, 2023).

- Zhou, S.; Collier, S.; Jaffe, D. A., Briggs, N. L., Hee, J., Sedlacek III, A. J., Kleinman, L., Onasch, T. B., and Zhang, Q.: Regional influence of wildfires on aerosol chemistry in the western US and insights into atmospheric aging of biomass burning organic aerosol, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 17, 2477–2493, 2017. [CrossRef]

- IPCC (2021). Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. In: Masson-Delmotte, V.; Zhai, P.; Pirani, A.; Connors, S.L.; et al. (eds). Cambridge University Press. [CrossRef]

- Pandis, S. N., Harley R. A., Cass G. R. and Seinfeld J. H. (1992) Secondary Organic Aerosol Formation and Transport, Atmospheric Environment, 26, 2266 2282.

- Hallquist, M.; Wenger, J. C., Baltensperger, U., Rudich, Y., Simpson, D., Claeys, M., Dommen, J., Donahue, N. M., George, C., Goldstein, A. H., Hamilton, J. F., Herrmann, H., Hoffmann, T., Iinuma, Y., Jang, M., Jenkin, M. E., Jimenez, J. L., Kiendler-Scharr, A., Maenhaut, W., McFiggans, G., Mentel, Th. F., Monod, A., Prévôt, A. S. H., Seinfeld, J. H., Surratt, J. D., Szmigielski, R., and Wildt, J.: The formation, properties and impact of secondary organic aerosol: current and emerging issues, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 9, 5155–5236, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Stein Zweers, D.C, 2022. TROPOMI ATBD of the UV Aerosol Index, Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute, S5P-KNMI-L2-0008-RP issue 2.1.0, 22 July 2022, TROPOMI ATBD of the UV Aerosol Index, (last access: 15 April 2025).

- de Graaf, M. and Stammes, P.: SCIAMACHY Absorbing Aerosol Index – calibration issues and global results from 2002–2004, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 5, 2385–2394, 2005. [CrossRef]

- Apituley, A.; Pedergnana, M.; Sneep, M.; Veefkind, J. P., Loyola, D., and Zweers, D. S.: Sentinel-5 precursor/TROPOMI level 2 product user manual UV aerosol index. https://sentinels.copernicus.eu/documents/247904/2474726/ Sentinel-5P-Level-2-Product-User-Manual-Aerosol-Index-product (last access: 2 July 2025), 2022.

- Nanda, S.; de Graaf, M.; Sneep, M.; de Haan, J. F., Stammes, P., Sanders, A. F. J., Tuinder, O., Veefkind, J. P., and Levelt, P. F.: Error sources in the retrieval of aerosol information over bright surfaces from satellite measurements in the oxygen A band, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 11, 161–175, 2018. [CrossRef]

- de Graaf, M.; Sneep, M.; ter Linden, M.; Tilstra L. G., Donovan, D. P., van Zadelhoff, G.-J., and Veefkind, J. P.: Improvements in aerosol layer height retrievals from TROPOMI oxygen A-band measurements by surface albedo fitting in optimal estimation, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 18, 2553–2571, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Apituley, A.; Pedergnana, M.; Sneep, M.; Veefkind, J. P., Loyola, D., Sanders, B., and de Graaf, M., 2024b. Sentinel-5 precursor/TROPOMI Level 2 Product User Manual Aerosol Layer Height, S5P-KNMI-L2-0022-MA, issue 2.8.0, 08 November 2024, CI-7570-PUM, [online]. https://sentiwiki.copernicus.eu/web/s5p-products(last access: 15 March 2025).

- Michailidis, K.; Koukouli, M.-E.; Balis, D.; Veefkind, J. P., de Graaf, M., Mona, L., Papagianopoulos, N., Pappalardo, G., Tsikoudi, I., Amiridis, V., Marinou, E., Gialitaki, A., Mamouri, R.-E., Nisantzi, A., Bortoli, D., João Costa, M., Salgueiro, V., Papayannis, A., Mylonaki, M., Alados-Arboledas, L., Romano, S., Perrone, M. R., and Baars, H.: Validation of the TROPOMI/S5P aerosol layer height using EARLINET lidars, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 23, 1919–1940, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Xu Weidong, Wooster Martin J., He Jiangping, Zhang Tianran, First study of Sentinel-3 SLSTR active fire detection and FRP retrieval: Night-time algorithm enhancements and global intercomparison to MODIS and VIIRS AF products, Remote Sensing of Environment, Volume 248, 2020, 111947, ISSN 0034-4257. [CrossRef]

- Donlon, C.; Berruti, B.; Buongiorno, A.; Ferreira, M.H.; Féménias, P. Frerick, F., Goryl, P., Klein, U., Laur, H., Mavrocordatos, C., Nieke, J., Rebhan, H., Seitz, B., Stroede, J., Sciarra R.: The Global Monitoring for Environment and Security (GMES) Sentinel-3 mission, Remote Sens. Environ., 120 (2012), pp. 37-57.

- Illingworth, A. J., Barker, H. W., Beljaars, A., Ceccaldi, M., Chepfer, H., Clerbaux, N., Cole, J., Delanoë, J., Domenech, C., Donovan, D. P., Fukuda, S., Hirakata, M., Hogan, R. J., Huenerbein, A., Kollias, P., Kubota, T., Nakajima, T., Nakajima, T. Y., Nishizawa, T., Ohno, Y., Okamoto, H., Oki, R., Sato, K., Satoh, M., Shephard, M. W., Velázquez-Blázquez, A., Wandinger, U., Wehr, T., and van Zadelhoff, G.-J.: The EarthCARE Satellite: The Next Step Forward in Global Measurements of Clouds, Aerosols, Precipitation, and Radiation, B. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 96, 1311–1332, 2015. [CrossRef]

- van Zadelhoff, G.-J.; Donovan, D. P., and Wang, P.: Detection of aerosol and cloud features for the EarthCARE atmospheric lidar (ATLID): the ATLID FeatureMask (A-FM) product, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 16, 3631–3651, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Wehr, T., Kubota, T., Tzeremes, G., Wallace, K., Nakatsuka, H., Ohno, Y., Koopman, R., Rusli, S., Kikuchi, M., Eisinger, M., Tanaka, T., Taga, M., Deghaye, P., Tomita, E., and Bernaerts, D.: The EarthCARE mission – science and system overview, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 16, 3581–3608, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Donovan, D. P., van Zadelhoff, G.-J., and Wang, P.: The EarthCARE lidar cloud and aerosol profile processor (A-PRO): the A-AER, A-EBD, A-TC, and A-ICE products, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 17, 5301–5340, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Eisinger, M., Marnas, F., Wallace, K., Kubota, T., Tomiyama, N., Ohno, Y., Tanaka, T., Tomita, E., Wehr, T., and Bernaerts, D.: The EarthCARE mission: science data processing chain overview, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 17, 839–862, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Seinfeld, J. H., & Pandis, S. N. (2016). Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics: From Air Pollution to Climate Change (3rd ed.). Wiley. [ISBN: 978-1-118-94740-1].

- Jacob, D.J. (2000). Heterogeneous chemistry and tropospheric ozone. Atmospheric Environment, 34(12-14), 2131-2159. [CrossRef]

- Lamsal, L. N., Krotkov, N. A., Celarier, E. A., et al. (2015). Evaluation of OMI operational standard NO₂ column retrievals using in situ and surface-based NO₂ observations. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 14(21), 11587-11609. [CrossRef]

- Duncan, B. N., Lamsal, L. N., Thompson, A. M., et al. (2016). A space-based, high-resolution view of notable changes in urban NO₂ pollution around the world (2005–2014). Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 121(2), 976-996. [CrossRef]

- Krotkov, N. A., McLinden, C. A., Li, C., Lamsal, L. N., et al. (2016). Aura OMI observations of regional SO₂ and NO₂ pollution changes from 2005 to 2015. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 16(7), 4605-4629. [CrossRef]

- van Geffen, J.H.G.M., H.J. Eskes, K.F. Boersma and J.P. Veefkind, TROPOMI ATBD of the total and tropospheric NO2 data products, document number: S5P-KNMI-L2-0005-RP, CI identification:CI-7430-ATBD, issue: 2.8.0, date: 2024-11-18, status: released, TROPOMI ATBD of the total and tropospheric NO2 data products, last accessed: 04.11.2025.

- De Smedt, Isabelle, Nicolas Theys, Jonas Vlietinck, Huan Yu, Thomas Danckaert, Christophe Lerot, Michel Van Roozendael, S5P/TROPOMI HCHO ATBD, document number: S5P- BIRA-L2-400F-ATBD, CI identification: CI-400F-ATBD, issue: 2.7.0, date: 2024-10-01, status: Update for the version 2.7.0 of the operational processor, S5P Documents, last accessed: 04.11.2025.

- Szykman James, R. Bradley Pierce, Barron Henderson and Laura Judd, for the TEMPO Validation Team and TEMPO Ad-hoc Validation Working Group, Validation and Quality Assessment of the TEMPO Level-2 Trace Gas Products, SAO-DRD-XX, version: Baseline, release date: September 15, 2025. https://asdc.larc.nasa.gov/documents/tempo/TEMPO_validation_report_baseline_draft.pdf last accessed: 30.10.2025.

- Stavrakou, T., Müller, J.-F., Bauwens, M., De Smedt, I., Van Roozendael, M., De Mazière, M., Vigouroux, C., Hendrick, F., George, M., Clerbaux, C., Coheur, P.-F., and Guenther, A.: How consistent are top-down hydrocarbon emissions based on formaldehyde observations from GOME-2 and OMI?, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 15, 11861–11884, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Eke, M., Cingiroglu, F., Kaynak, B.: Investigation of 2021 wildfire impacts on air quality in southwestern Turkey,Atmospheric Environment,Volume 325, 2024, 120445,ISSN 1352-2310. [CrossRef]

- Schollaert, C.; Connolly, R.; Cushing, L.; Jerrett, M.; Liu, T.; Marlier, M. Air Quality Impacts of the January 2025 Los Angeles Wildfires: Insights from Public Data Sources. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2025, 12, 911–917. [CrossRef]

- Bi, J.; Wallace, L. A., Sarnat, J. A., and Liu, Y.: Characterizing outdoor infiltration and indoor contribution of PM2.5 with citizen-based low-cost monitoring data, Environ. Pollut., 276, 116763. [CrossRef]

- Wallace, L.; Bi, J.; Ott, W. R., Sarnat, J., and Liu, Y.: Calibration of low-cost PurpleAir outdoor monitors using an improved method of calculating PM2.5, Atmos. Environ., 256, 118432, 2021. [CrossRef]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Technical Assistance Document for the Reporting of Daily Air Quality – the Air Quality Index (AQI) (EPA-454/B-16-002). U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Air Quality Planning and Standards (2016).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).