Submitted:

05 November 2025

Posted:

10 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Using the JASP Environment

- Edit Title: instead of the word ‘Results’

- Copy

- Export Results: to the computer

- Add note: This feature allows the results output to be easily annotated and exported to an HTML file by navigating to the Main menu > Export Results.

- Remove all analyses from the output window

- Refresh all

- Show R syntax

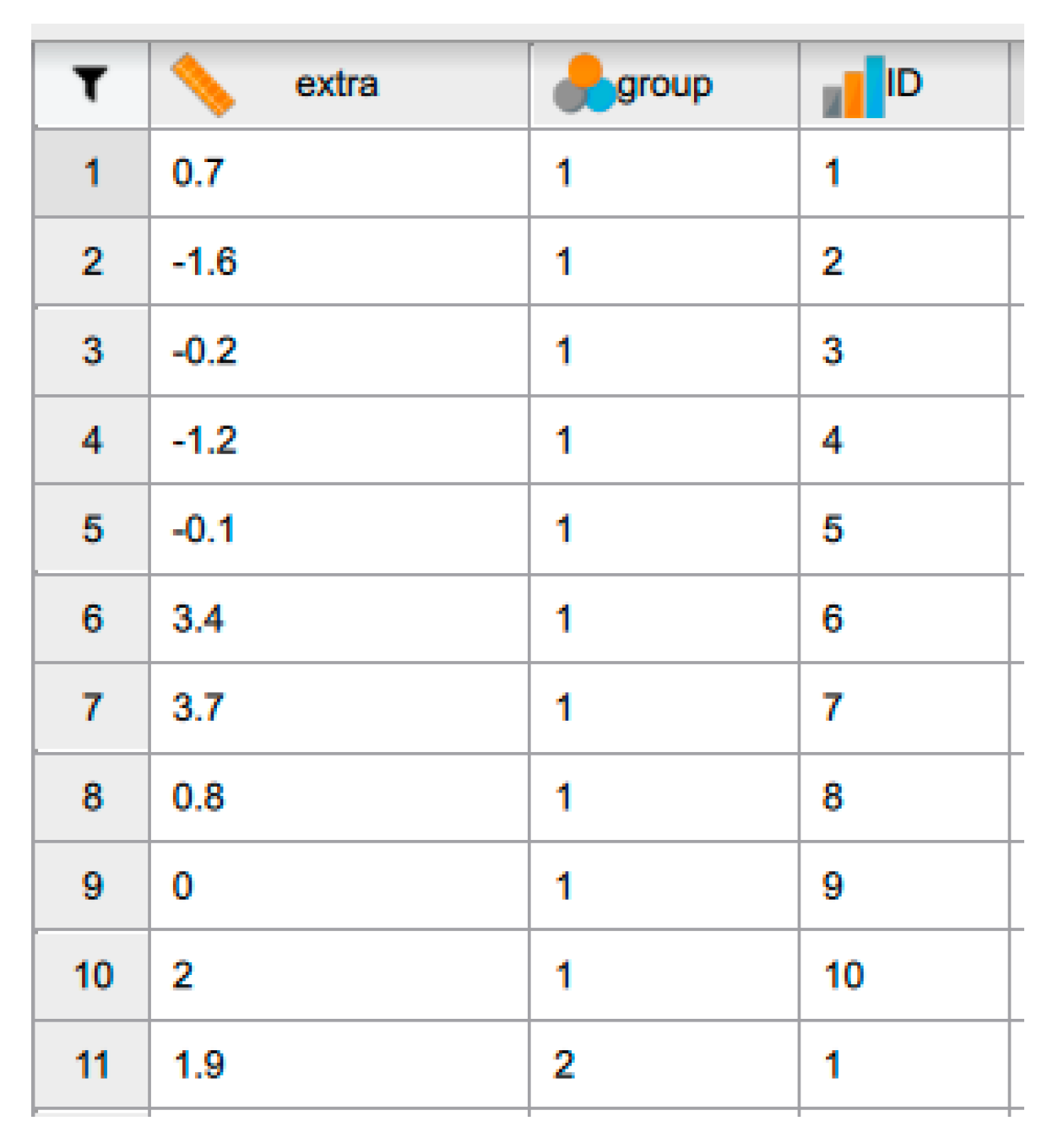

3. Data Handling in JASP

- Keep Original Data: It is a good practice to keep your original data file intact and create a separate file for any modifications or analyses.

- Check Compatibility: When exporting data, the suer needs to select a file format compatible with the software or platform where the user intend to use the data.

- Documentation: Maintain documentation of any changes made to the data or any transformations applied before exporting, as this can help ensure transparency and reproducibility in the analyses.

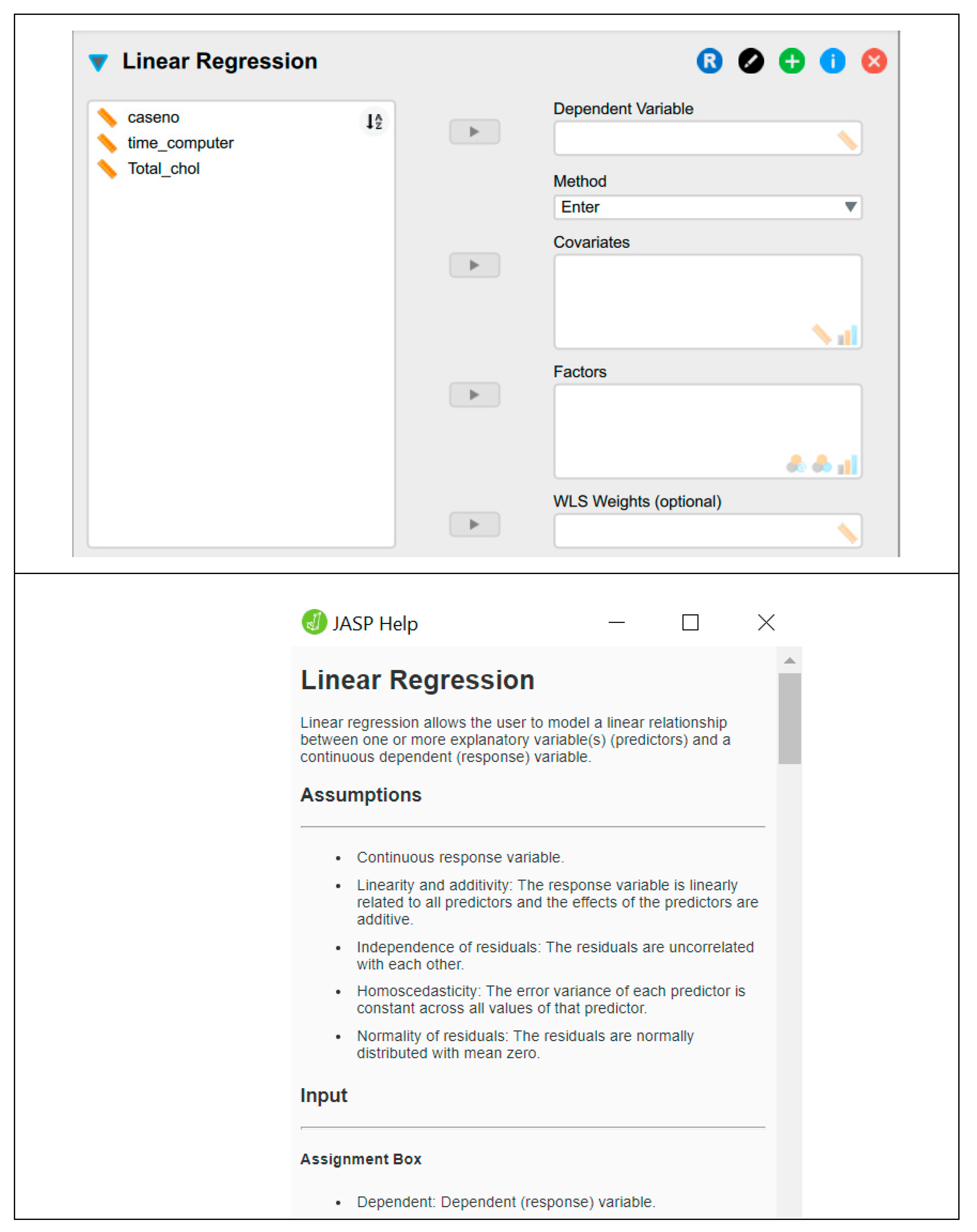

4. JASP Analysis Menu

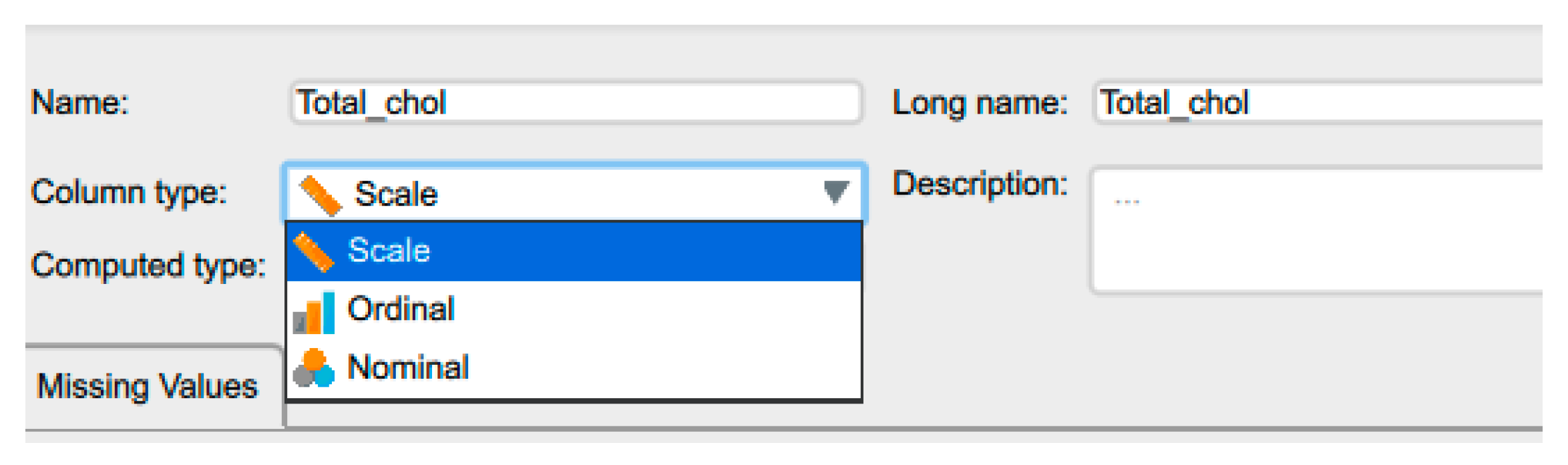

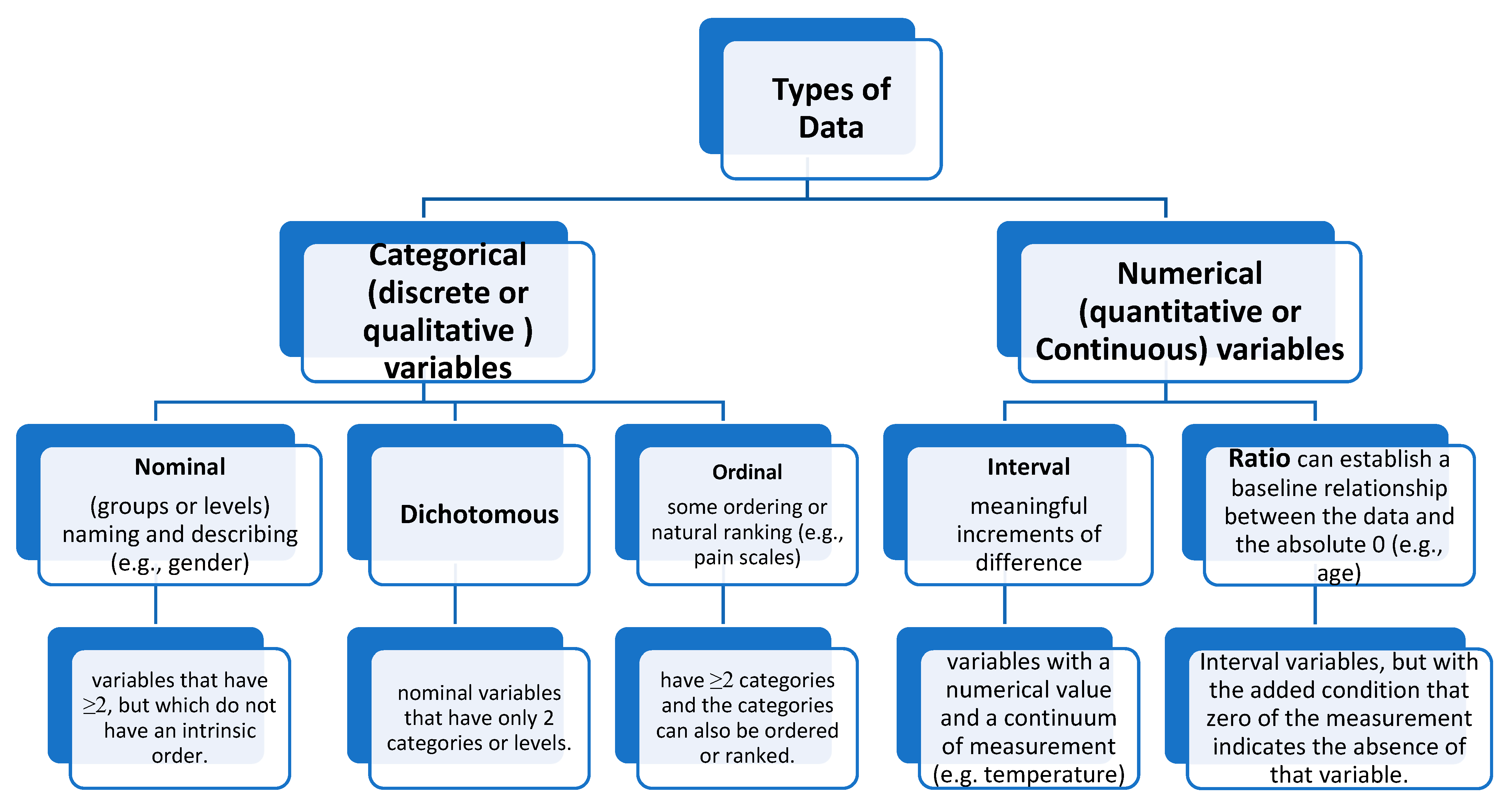

5. Types of Variables

5.1. Dependent and Independent Variables

5.2. Categorical and Continuous Variables

5.3. Discrete and Continuous Variables

5.4. Ambiguities in Classifying a Type of Variable

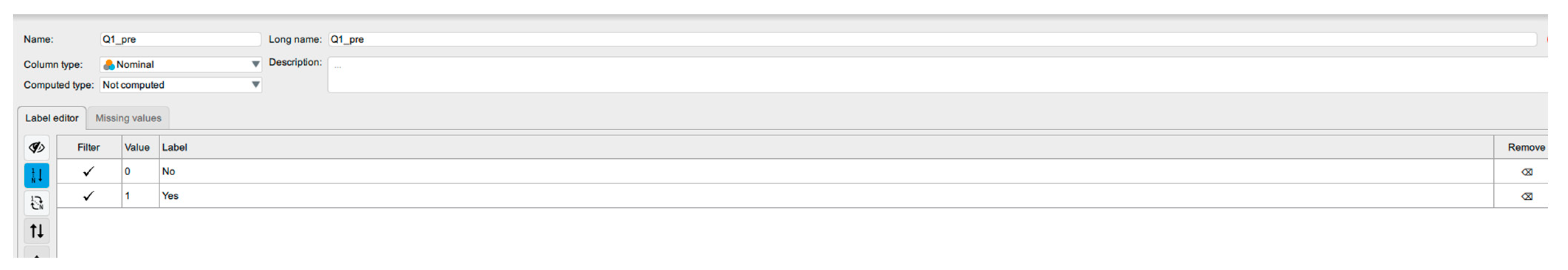

5.5. Recoding and Transforming Variables in JASP

- Check Assumptions: When recoding or transforming variables, be mindful of the statistical analysis assumptions we plan to use. Ensure that the transformations we apply do not violate these assumptions.

- Document Changes

- Preview Changes: Before applying recoding or transformations, we can preview the changes to see how they will affect the data. This can help us make informed decisions about the modifications to apply.

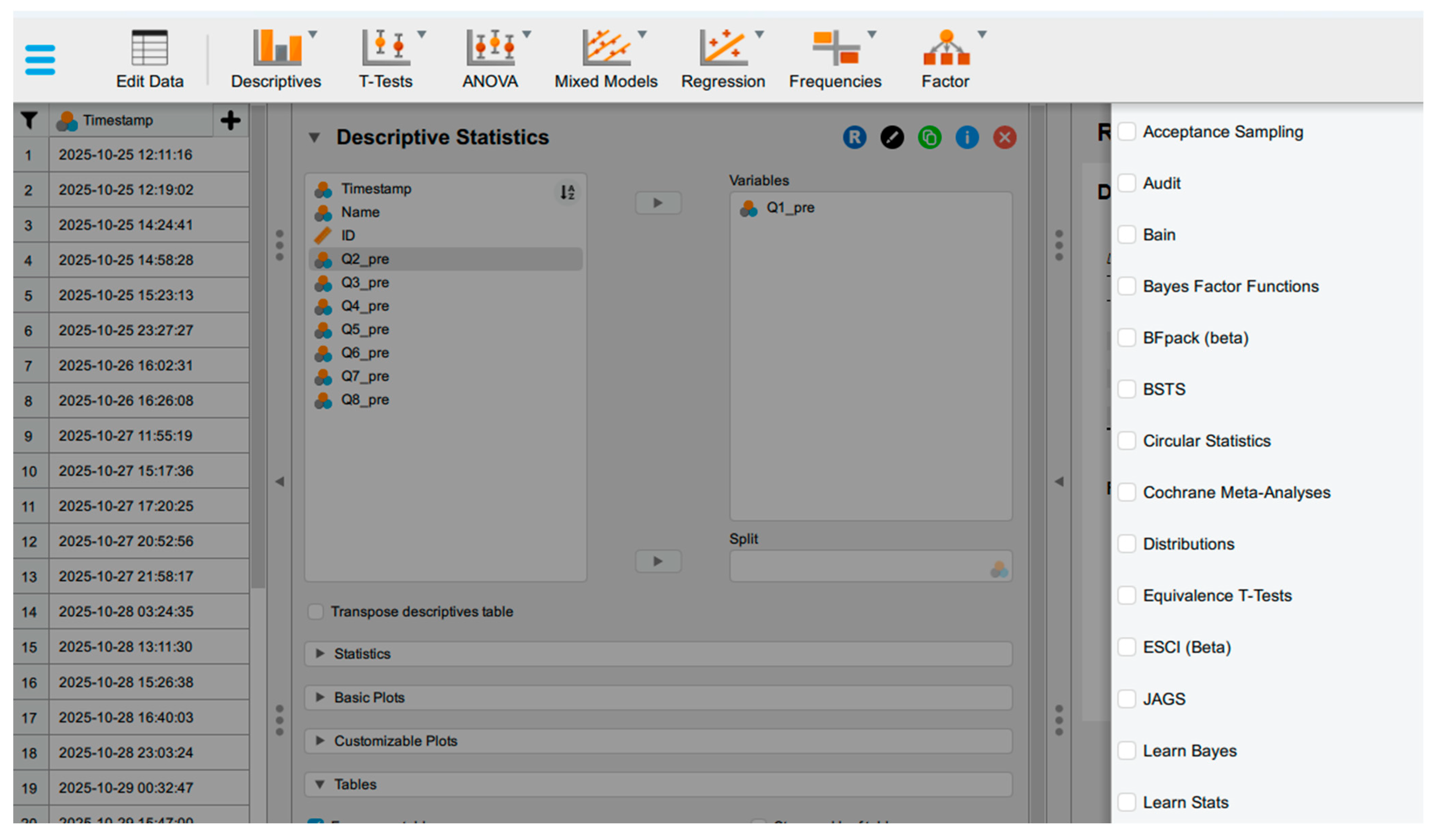

6. Descriptive Statistics

6.1. Measures of Central Tendency

6.2. Measures of Dispersion

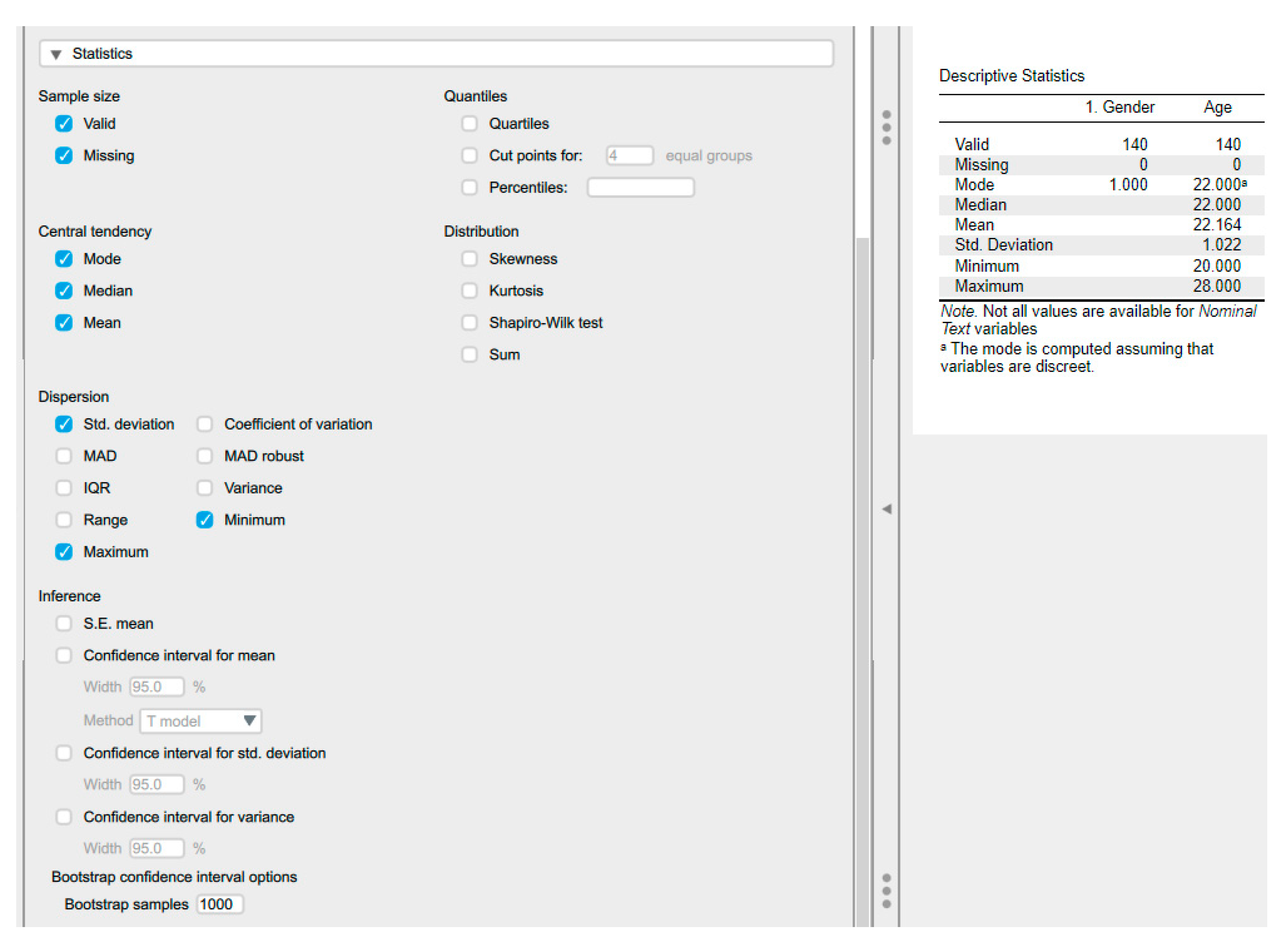

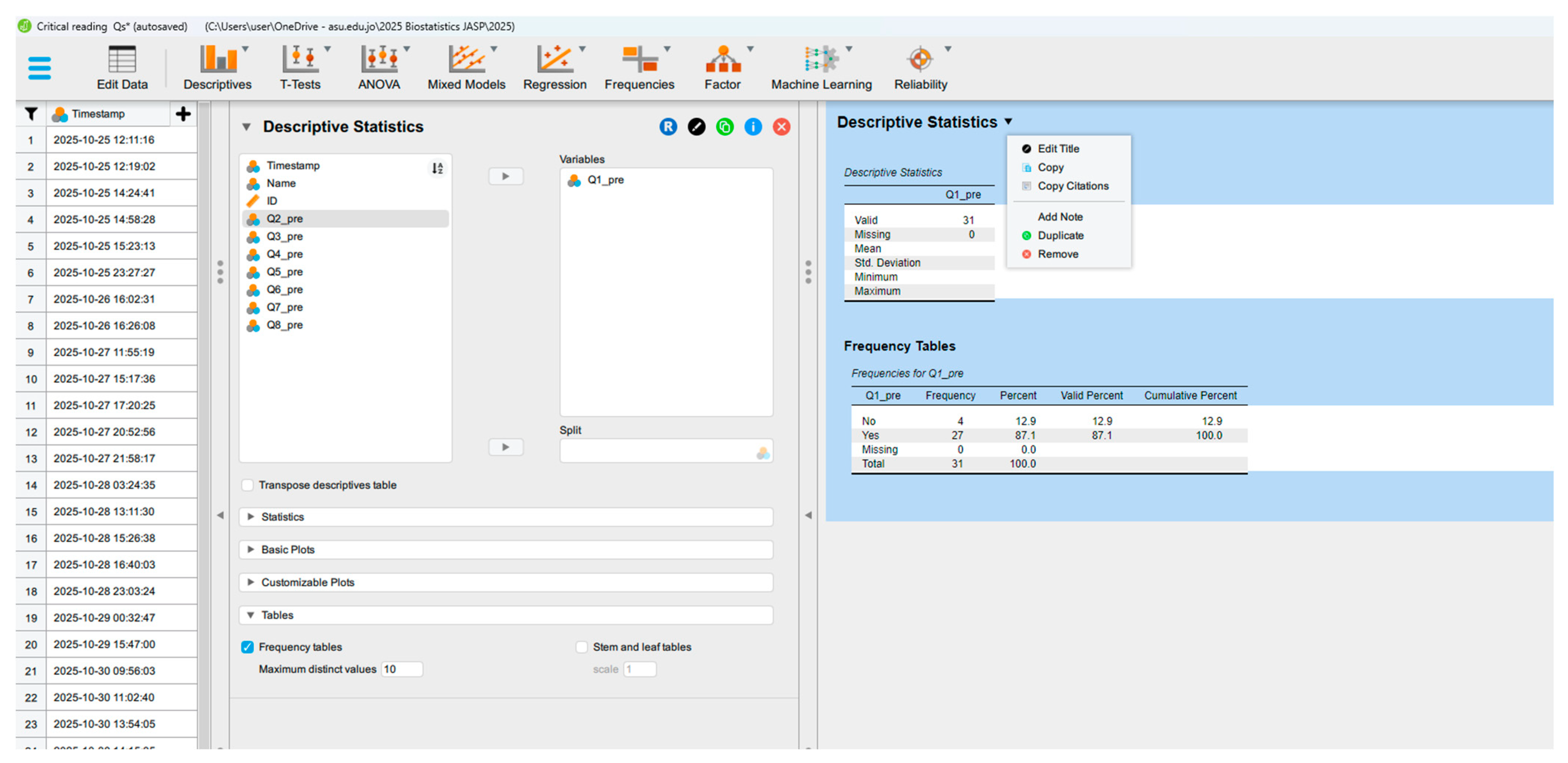

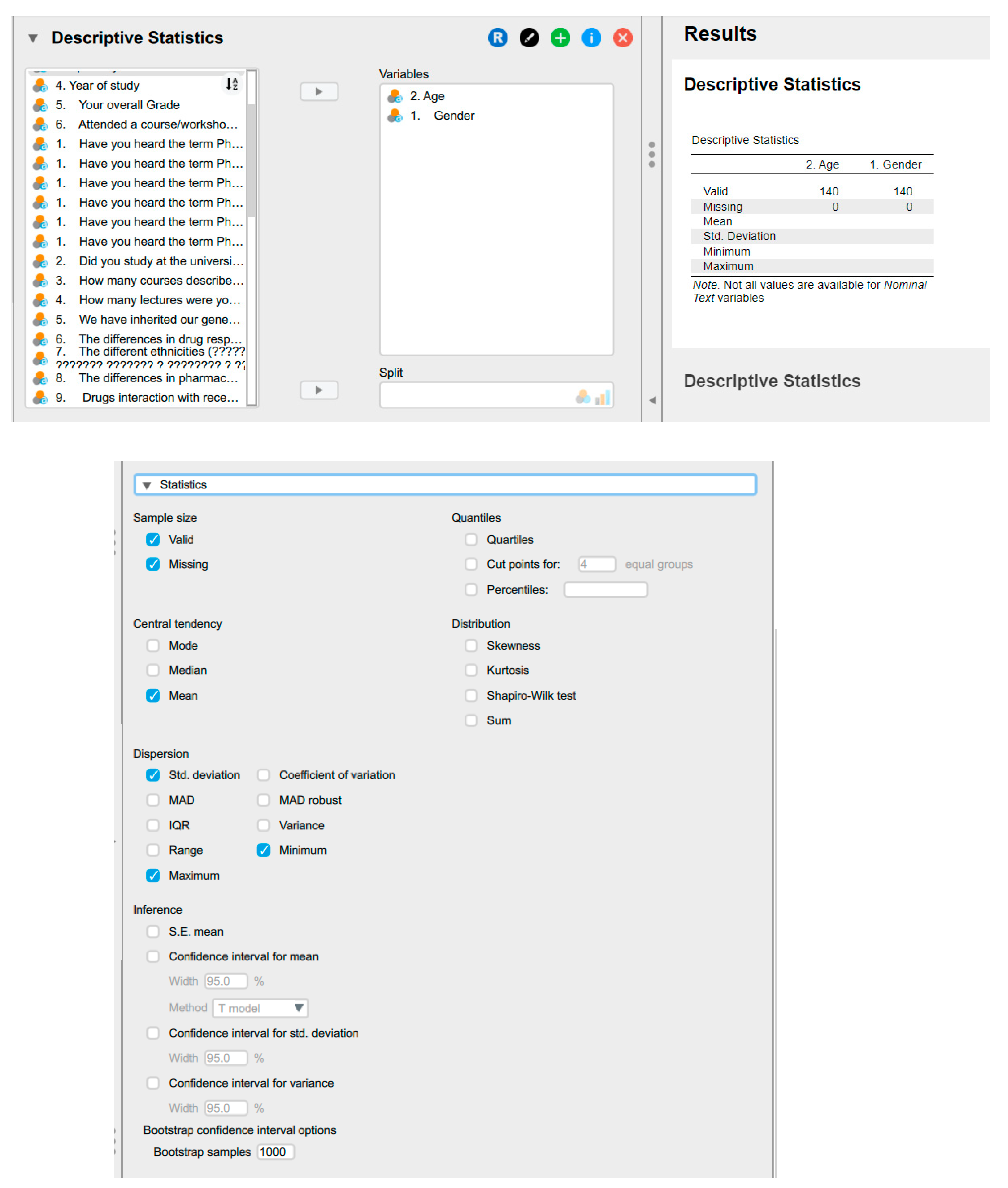

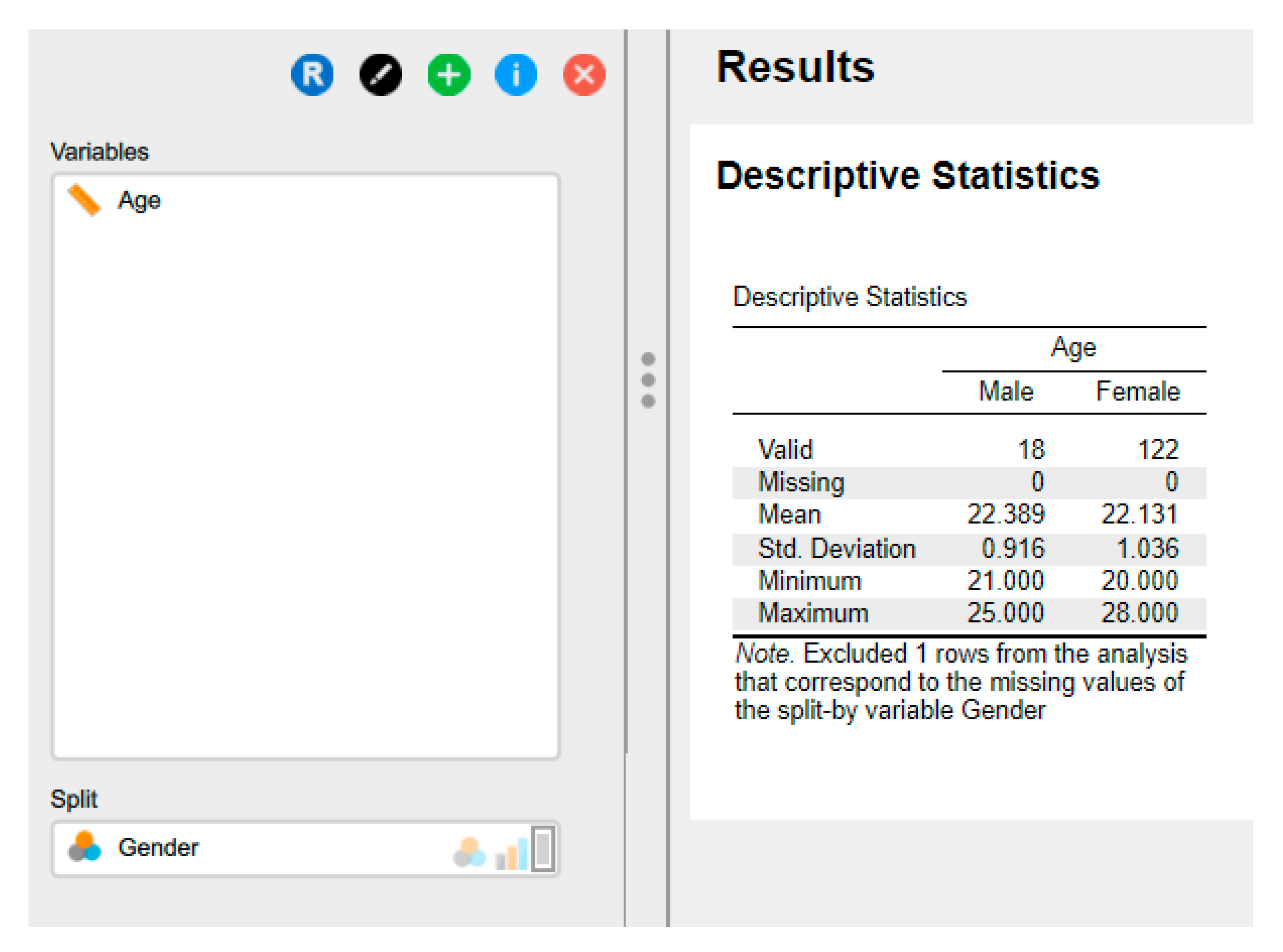

6.3. Descriptive Statistics Using JASP

6.4. Central Tendency

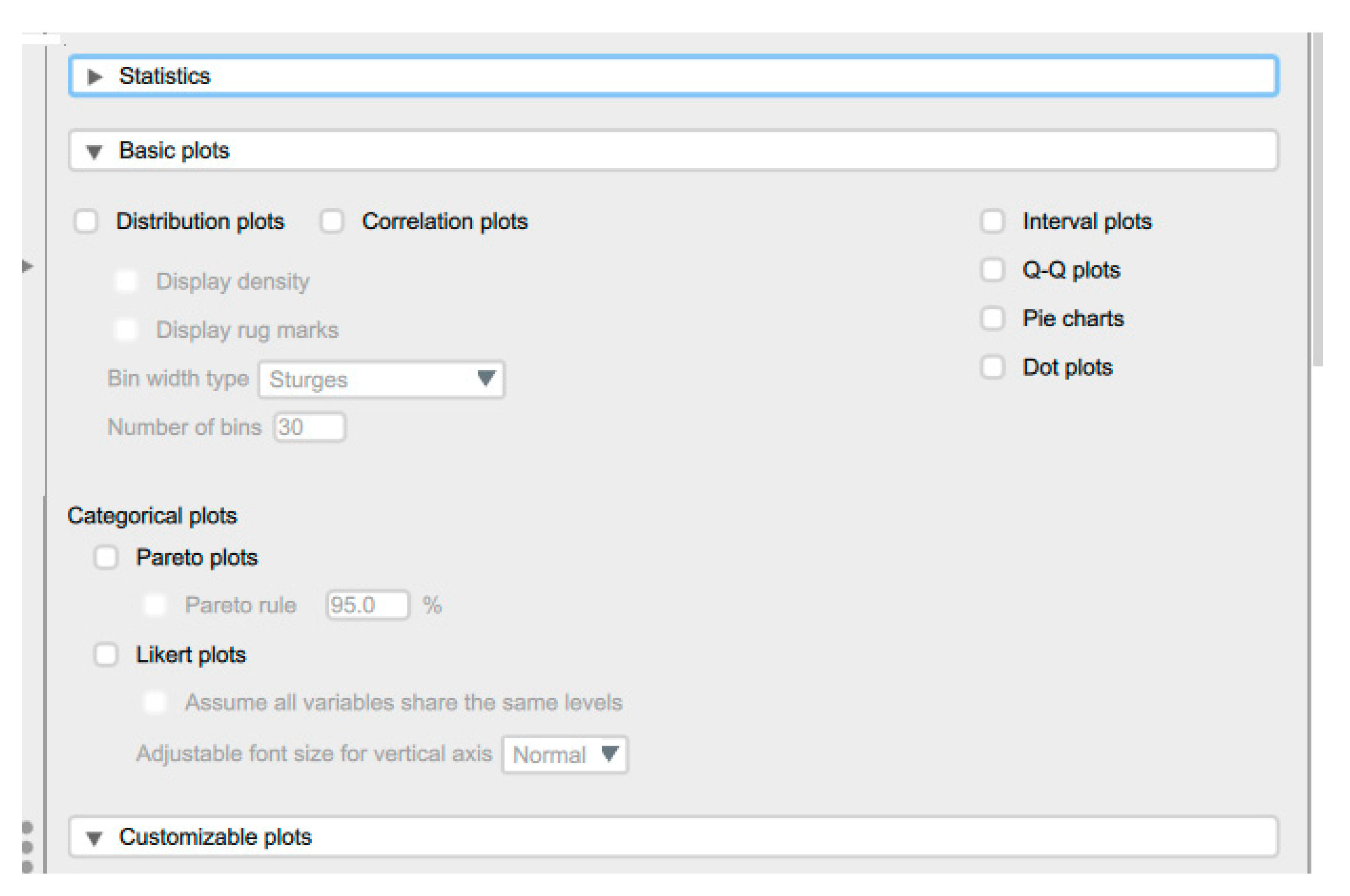

6.5. Plots, Graphs, and Figures

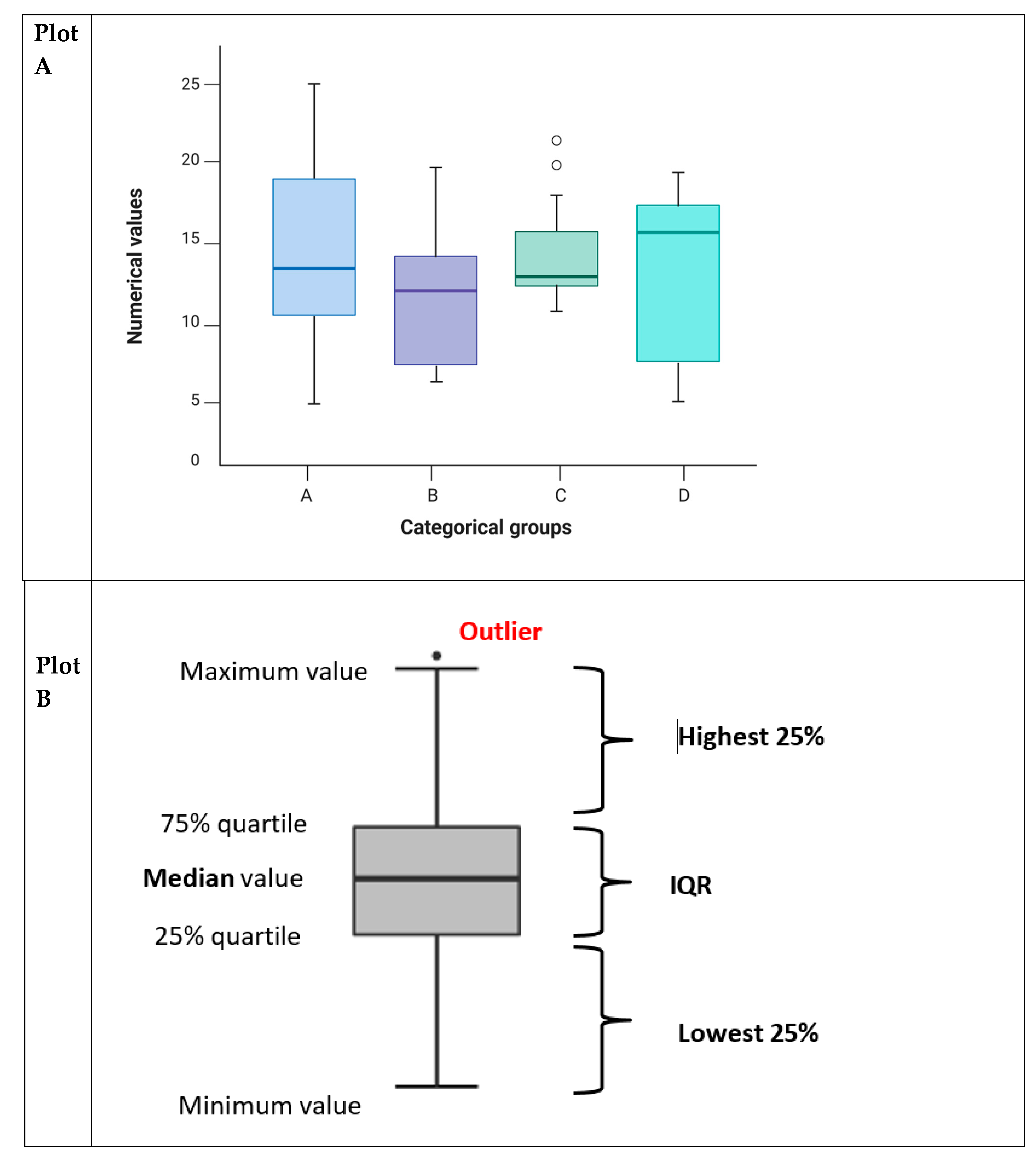

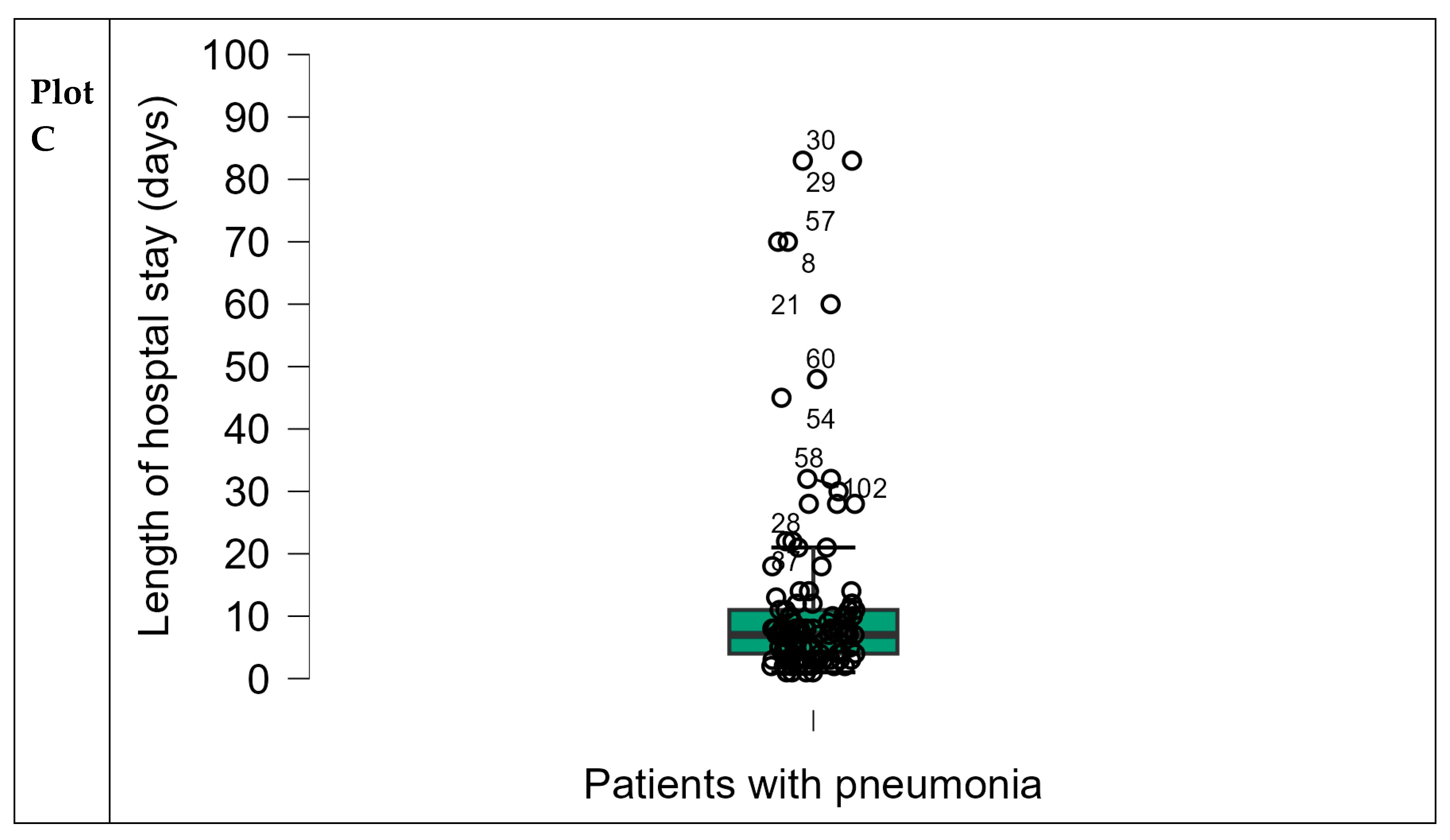

6.5.1. Box and Whisker Plots

6.5.2. Count/ Bar Plots

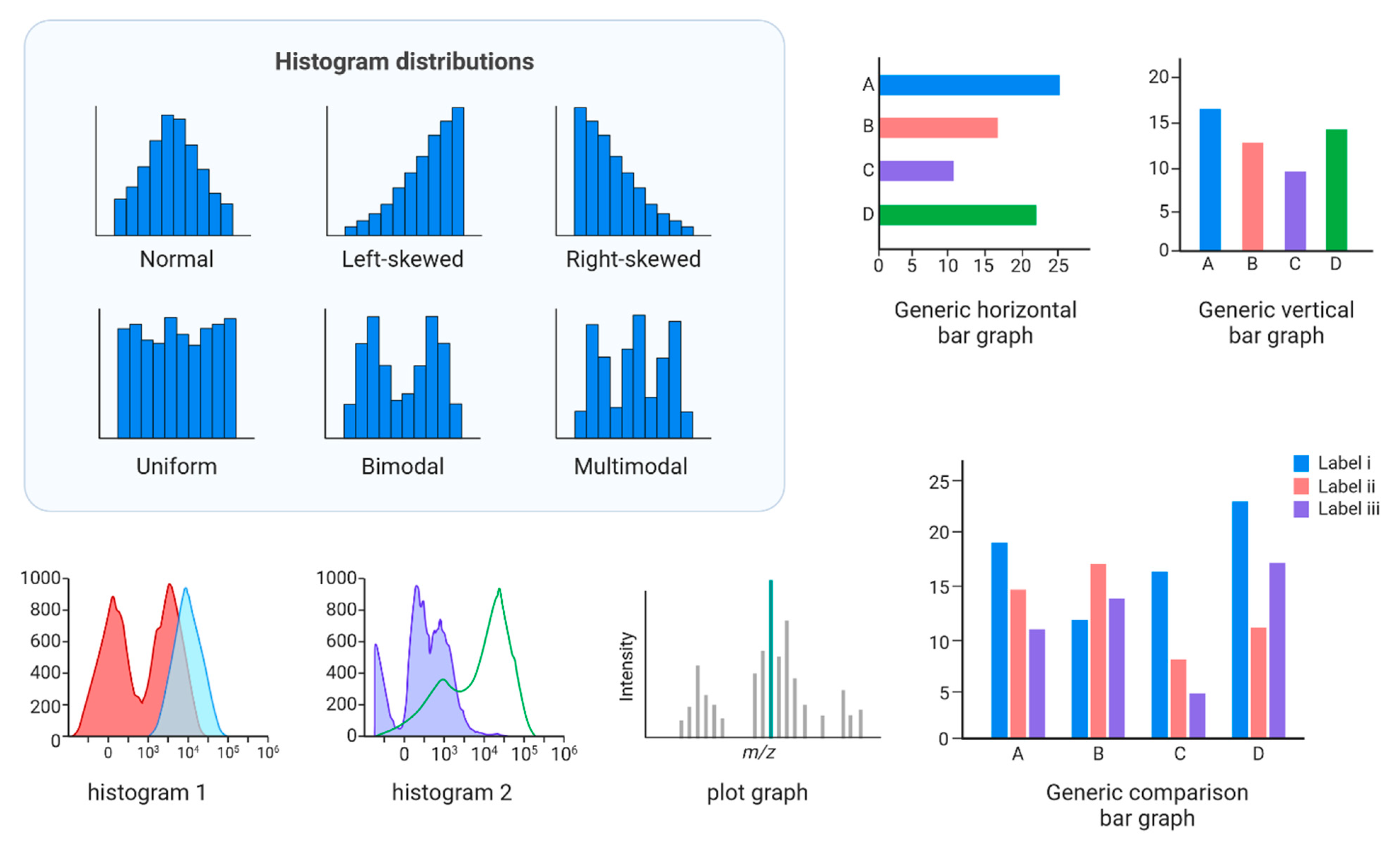

6.5.3. Histogram

6.5.4. Distribution Plots

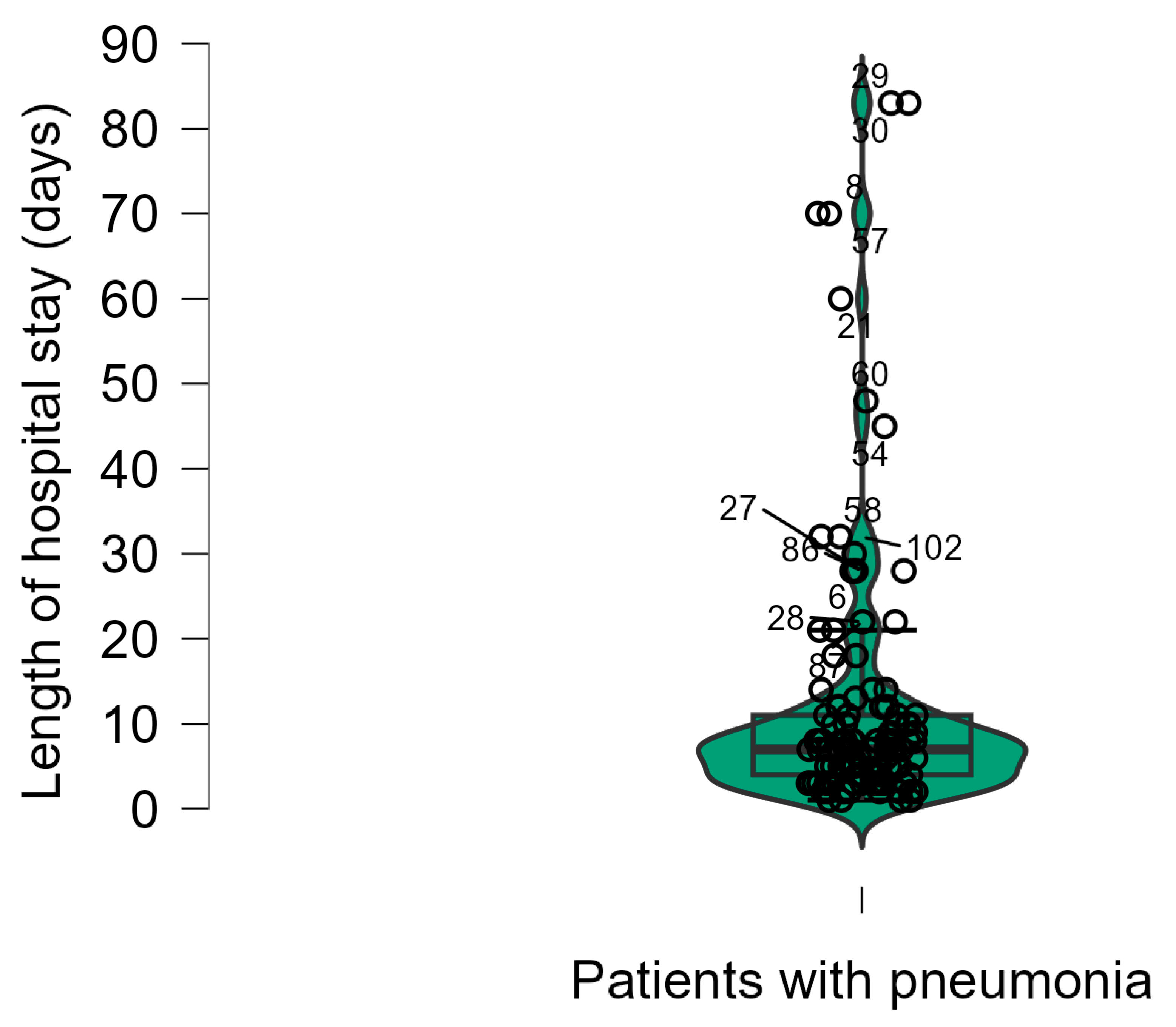

6.5.5. Violin Plots

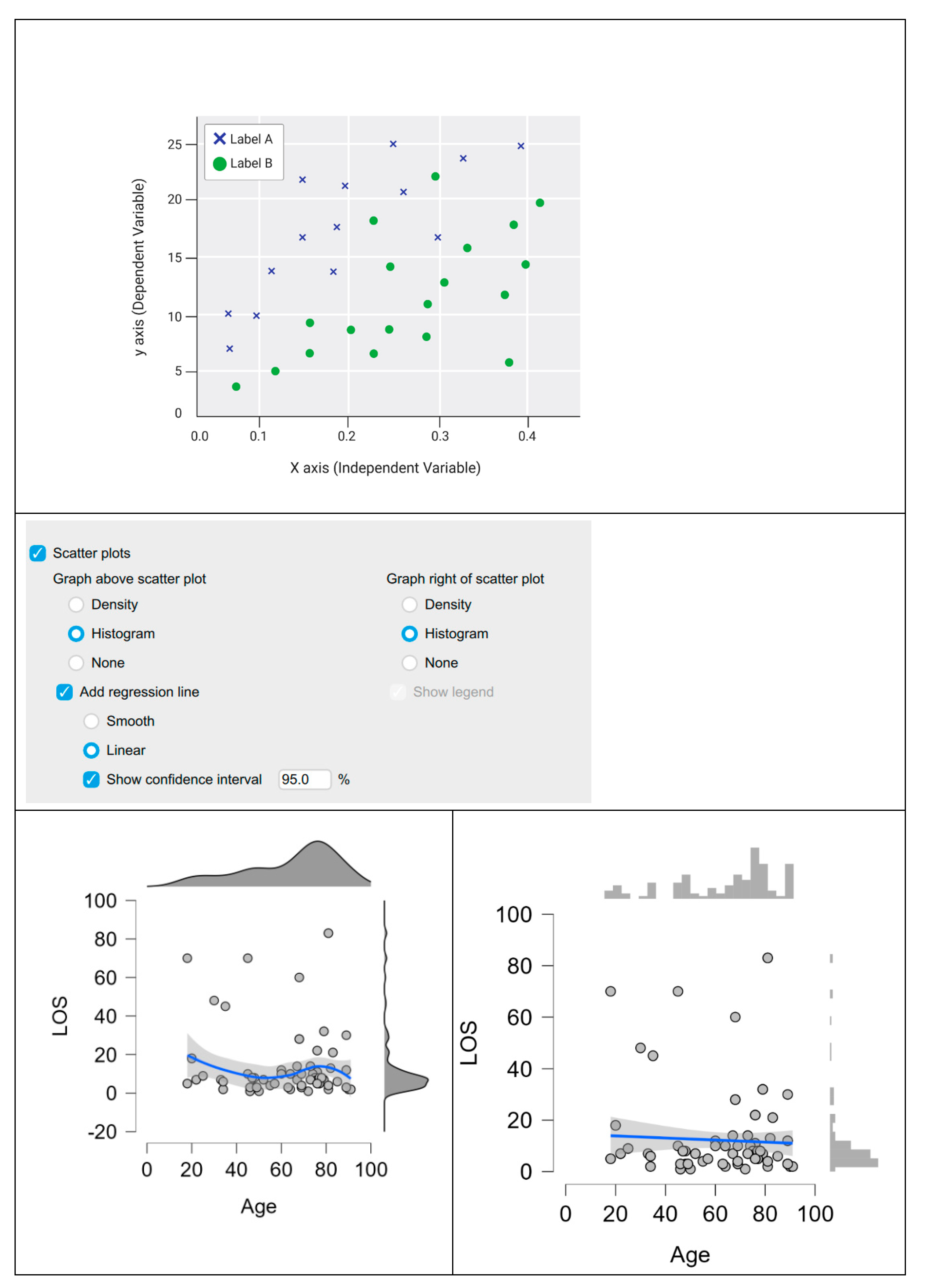

6.5.6. Scatter Plots

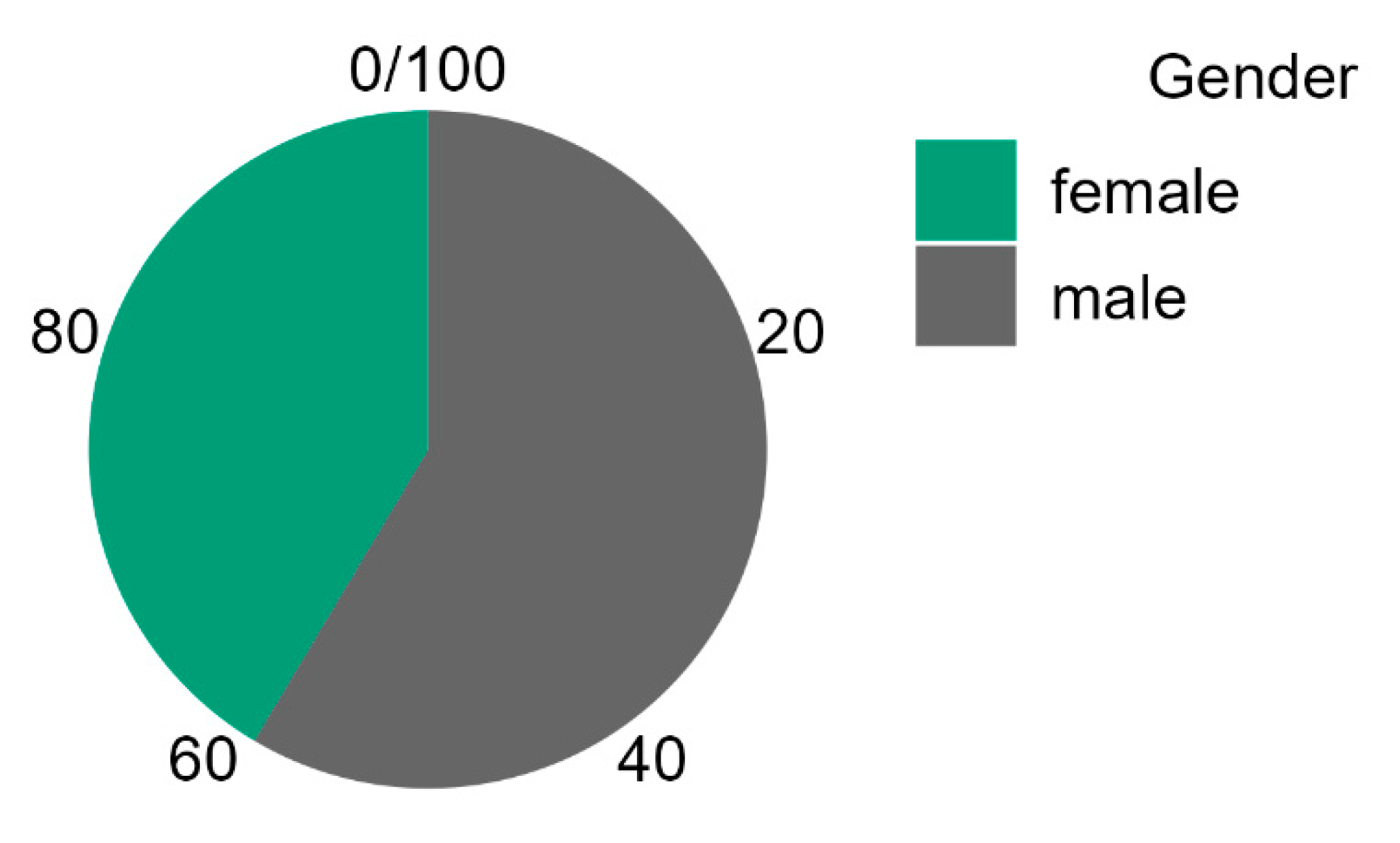

6.5.7. Pie Chart

7. Splitting Data Files

8. Exploring Data Integrity

- Participant selection bias – some being more likely to be selected for the study than others.

- Participant exclusion bias - due to the systematic exclusion of specific individuals from the study.

- Analytical bias - due to the way that the results are evaluated.

- Statistical bias can affect parameter estimates, standard errors, confidence intervals, test statistics and p-values.

8.1. Is the Data Correct?

9. Data Transformation

References

- Mansoor, A.R.; Abed, A.; Alqudah, A.; Alsayed, A.R. Assessment of Medical Care Strategies for Primary Hypertension in Iraqi Adults: A Hospital-Based Problem-Oriented Plan. Patient preference and adherence 2025, 1317–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsayed, A.R. Illustrating How to Use the Validated Alsayed_v1 Tools to Improve Medical Care: A Particular Reference to the Global Initiative for Asthma 2022 Recommendations. Patient preference and adherence 2023, 1161–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, R.D.; Lambert, P.C.; Abo-Zaid, G. Meta-Analysis of Individual Participant Data: Rationale, Conduct, and Reporting. BMJ 2010, 340, c221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, K.; Zerbe, G.; Engelman, C.D.; Norris, J.M.; Weitzel, L.-R.B. Genome Scan Linkage Results for Longitudinal Systolic Blood Pressure Phenotypes in Subjects from the Framingham Heart Study. BMC Genetics 2003, 4, S83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsayed, A.R.; Abu Ajamieh, M.; Melhem, M.; Samara, A.; Hakooz, N. Pharmacogenetics Education for Pharmacy Students: Measuring Knowledge and Attitude Changes. Advances in Medical Education and Practice 2025, 1761–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fino, L.B.; Alsayed, A.R.; Basheti, I.A.; Saini, B.; Moles, R.; Chaar, B.B. Implementing and Evaluating a Course in Professional Ethics for an Undergraduate Pharmacy Curriculum: A Feasibility Study. Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning 2022, 14, 88–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsayed, A.R.; Hasoun, L.; Al-Dulaimi, A.; AbuAwad, A.; Basheti, I.; Khader, H.A.; Al Maqbali, M. Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Educational Medical Informatics Tutorial on Improving Pharmacy Students’ Knowledge and Skills about the Clinical Problem-Solving Process. Pharmacy Practice 2022, 20, 2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsayed, A.R.; Alsayed, Y. Integrating Telemonitoring in COPD Exacerbations Care: A Multinational Study Using the Alsayed System for Applied Medical-Care Improvement (ASAMI) Database. OBM Transplantation 2025, 9, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsayed, A.R.; Alsayed, Y. Evaluating the Role of Telemonitoring in Detecting COPD Ex-Acerbations: Results from a Multinational Study. 2024.

- Shaqfeh, M.I.; Alsayed, A.R.; Hasoun, L.Z.; Khader, H.A.; Zihlif, M.A. The Effects of Trade Names on the Misuse of Some Over-The-Counter Drugs and Assessment of Community Knowledge and Attitudes in Alkarak, Jordan. Patient preference and adherence 2024, 2697–2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqbali, M.A.; Alsayed, A.; Hughes, C.; Hacker, E.; Dickens, G.L. Stress, Anxiety, Depression and Sleep Disturbance among Healthcare Professional during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Umbrella Review of 72 Meta-Analyses. PloS one 2024, 19, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrasheeday, A.; Alsaeed, M.A.; Alshammari, B.; Alshammari, F.; Alrashidi, A.S.; Alsaif, T.A.; Mahmoud, S.K.; Cabansag, D.I.; Borja, M.V.; Alsayed, A.R. Sleep Quality among Emergency Nurses and Its Influencing Factors during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study. Frontiers in Psychology 2024, 15, 1363527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Maqbali, M.; Alsayed, A.; Bashayreh, I. Quality of Life and Psychological Impact among Chronic Disease Patients during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Integrative Nursing 2022, 4, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khader, H.; Hasoun, L.Z.; Alsayed, A.; Abu-Samak, M. Potentially Inappropriate Medications Use and Its Associated Factors among Geriatric Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study Based on 2019 Beers Criteria. Pharmacia 2021, 68, 789–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Moraes, A.G.; Africano, C.J.R.; Hoskote, S.S.; Reddy, D.R.S.; Tedja, R.; Thakur, L.; Pannu, J.K.; Hassebroek, E.C.; Smischney, N.J. Ketamine and Propofol Combination (“Ketofol”) for Endotracheal Intubations in Critically Ill Patients: A Case Series. The American Journal of Case Reports 2015, 16, 81. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrenson, J.G.; Evans, J.R. Advice about Diet and Smoking for People with or at Risk of Age-Related Macular Degeneration: A Cross-Sectional Survey of Eye Care Professionals in the UK. BMC public health 2013, 13, 564. [Google Scholar]

- Alsayed, A.; Halloush, S.; Hasoun, L. Perspectives of the Community in the Developing Countries toward Telemedicine and Pharmaceutical Care during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Pharm Pract (Granada). 2022; 20 (1): 2618.

- Alsayed, A.R.; El Hajji, F.D.; Al-Najjar, M.A.; Abazid, H.; Al-Dulaimi, A. Patterns of Antibiotic Use, Knowledge, and Perceptions among Different Population Categories: A Comprehensive Study Based in Arabic Countries. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal 2022, 30, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu Khadija, L.H.; Alomari, S.M.; Alsayed, A.R.; Khader, H.A.; Permana, A.D.; Hasoun, L.Z.; Zraikat, M.S.; Ashran, W.; Zihlif, M. Beyond Culture: Real-Time PCR Performance in Detecting Causative Pathogens and Key Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Hospital-Acquired Pneumonia. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-kilkawi, Z.M.; Basheti, I.A.; Obeidat, N.M.; Saleh, M.R.; Hamadi, S.; Abutayeh, R.; Nassar, R.; Alsayed, A.R. Evaluation of the Association between Inhaler Technique and Adherence in Asthma Control: Cross-Sectional Comparative Analysis Study between Amman and Baghdad. Pharmacy Practice 2024, 22, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Lubke, G.H.; Muthén, B.O. Applying Multigroup Confirmatory Factor Models for Continuous Outcomes to Likert Scale Data Complicates Meaningful Group Comparisons. Structural equation modeling 2004, 11, 514–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahfufah, U.; Sya’ban Mahfud, M.A.; Saputra, M.D.; Abd Azis, S.B.; Salsabila, A.; Asri, R.M.; Habibie, H.; Sari, Y.; Yulianty, R.; Alsayed, A.R. Incorporation of Inclusion Complexes in the Dissolvable Microneedle Ocular Patch System for the Efficiency of Fluconazole in the Therapy of Fungal Keratitis. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2024, 16, 25637–25651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rshaidat, M.M.; Al-Sharif, S.; Tamimi, T.A.; Al-Zeer, M.A.; Samhouri, J.; Alsayed, A.R.; Rayyan, Y.M. First Middle Eastern-Based Gut Microbiota Study: Implications for Inflammatory Bowel Disease Microbiota-Based Therapies. Pharmacy Practice 2025, 23, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrabadi, N.; Alsayed, A.R.; Saadeh, R.; Loze, K.J.A.; Aljanabi, M.; Al-Khamaiseh, A.M. Level of Awareness about Air Pollution among Decision-Makers in Jordan: Unveiling Important COPD Etiology. Pharmacy Practice (Granada) 2024, 22, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Rshaidat, M.M.; Al-Sharif, S.; Al Refaei, A.; Shewaikani, N.; Alsayed, A.R.; Rayyan, Y.M. Evaluating the Clinical Application of the Immune Cells’ Ratios and Inflammatory Markers in the Diagnosis of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Pharmacy Practice 2022, 21, 2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zihlif, M.; Zakaraya, Z.; Feda’Hamdan, A.S.; Tahboub, F.; Qudsi, S.; Abuarab, S.F.; Daghash, R.; Alsayed, A.R. Hepatocyte Nuclear Factor 4, Alpha (HNF4A): A Potential Biomarker for Chronic Hypoxia in MCF7 Breast Cancer Cell Lines. Pharmacy Practice (1886-3655) 2025, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khader, H.; Alsayed, A.; Hasoun, L.Z.; Alnatour, D.; Awajan, D.; Alhosanie, T.N.; Samara, A. Pharmaceutical Care and Telemedicine during COVID-19: A Cross-Sectional Study Based on Pharmacy Students, Pharmacists, and Physicians in Jordan. Pharmacia 2022, 69, 891–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsayed, A.R.; Talib, W.; Al-Dulaimi, A.; Daoud, S.; Al Maqbali, M. The First Detection of Pneumocystis Jirovecii in Asthmatic Patients Post-COVID-19 in Jordan. Bosnian journal of basic medical sciences 2022, 22, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dulaimi, A.; Alsayed, A.R.; Al Maqbali, M.; Zihlif, M. Investigating the Human Rhinovirus Co-Infection in Patients with Asthma Exacerbations and COVID-19. Pharmacy Practice 2022, 20, 2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahfufah, U.; Sya’ban Mahfud, M.A.; Saputra, M.D.; Abd Azis, S.B.; Salsabila, A.; Asri, R.M.; Habibie, H.; Sari, Y.; Yulianty, R.; Alsayed, A.R. Incorporation of Inclusion Complexes in the Dissolvable Microneedle Ocular Patch System for the Efficiency of Fluconazole in the Therapy of Fungal Keratitis. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2024, 16, 25637–25651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, B.A.; Oriquat, G.A.; Khader, H.A.; ALSAYED, A.R.; FARAH, H.S.; Alhmoud, J.F.; Al-Najjar, M.A.; Hasoun, L.; Abdelhalim, S.M.; Awwad, S.H. A Comparison of the Effect of Omega-3 Alone versus Omega-3/Vitamin D3 Co-Supplementation Therapy on 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Levels in Adults with Vitamin D Deficiency. Pharmacy Practice 2025, 23, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zihlif, M.; Zakaraya, Z.; Rawan, N.; Al-Shudiefat, A.A.-R.; ALSAYED, A.R. Association between Toll-Like Receptor 4 Gene and Inflammatory Bowel Disease among Jordanian Patients. Pharmacy Practice 2024, 22, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaled, R.A.; Alhmoud, J.F.; Issa, R.; Khader, H.A.; Mohammad, B.A.; Alsayed, A.R.; Khadra, K.A.; Habash, M.; Aljaberi, A.; Hasoun, L. The Variations of Selected Serum Cytokines Involved in Cytokine Storm after Omega-3 Daily Supplements: A Randomized Clinical Trial in Jordanians with Vitamin D Deficiency. Pharmacy Practice 2024, 22, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsayed, A.; Al-Doori, A.; Al-Dulaimi, A.; Alnaseri, A.; Abuhashish, J.; Aliasin, K.; Alfayoumi, I. Influences of Bovine Colostrum on Nasal Swab Microbiome and Viral Upper Respiratory Tract Infections–A Case Report. Respiratory medicine case reports 2020, 31, 101189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsayed, A.R.; Al-Dulaimi, A.; Alnatour, D.; Awajan, D.; Alshammari, B. Validation of an Assessment, Medical Problem-Oriented Plan, and Care Plan Tools for Demonstrating the Clinical Pharmacist’s Activities. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal 2022, 30, 1464–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bland, M. Estimating Mean and Standard Deviation from the Sample Size, Three Quartiles, Minimum, and Maximum. International Journal of Statistics in Medical Research 2015, 4, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, N.B. Estimation of Weibull Parameters from Common Percentiles. Journal of applied Statistics 2005, 32, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mramba, L.K.; Liu, X.; Lynch, K.F.; Yang, J.; Aronsson, C.A.; Hummel, S.; Norris, J.M.; Virtanen, S.M.; Hakola, L.; Uusitalo, U.M. Detecting Potential Outliers in Longitudinal Data with Time-Dependent Covariates. European journal of clinical nutrition 2024, 78, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaska, M.; Nuhu, B.M. Assessment of Measures of Central Tendency and Dispersion Using Likert-Type Scale. African Journal of Advances in Science and Technology Research 2024, 16, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, D.P.; Zimba, O.; Gasparyan, A.Y. Statistical Data Presentation: A Primer for Rheumatology Researchers. Rheumatology International 2021, 41, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

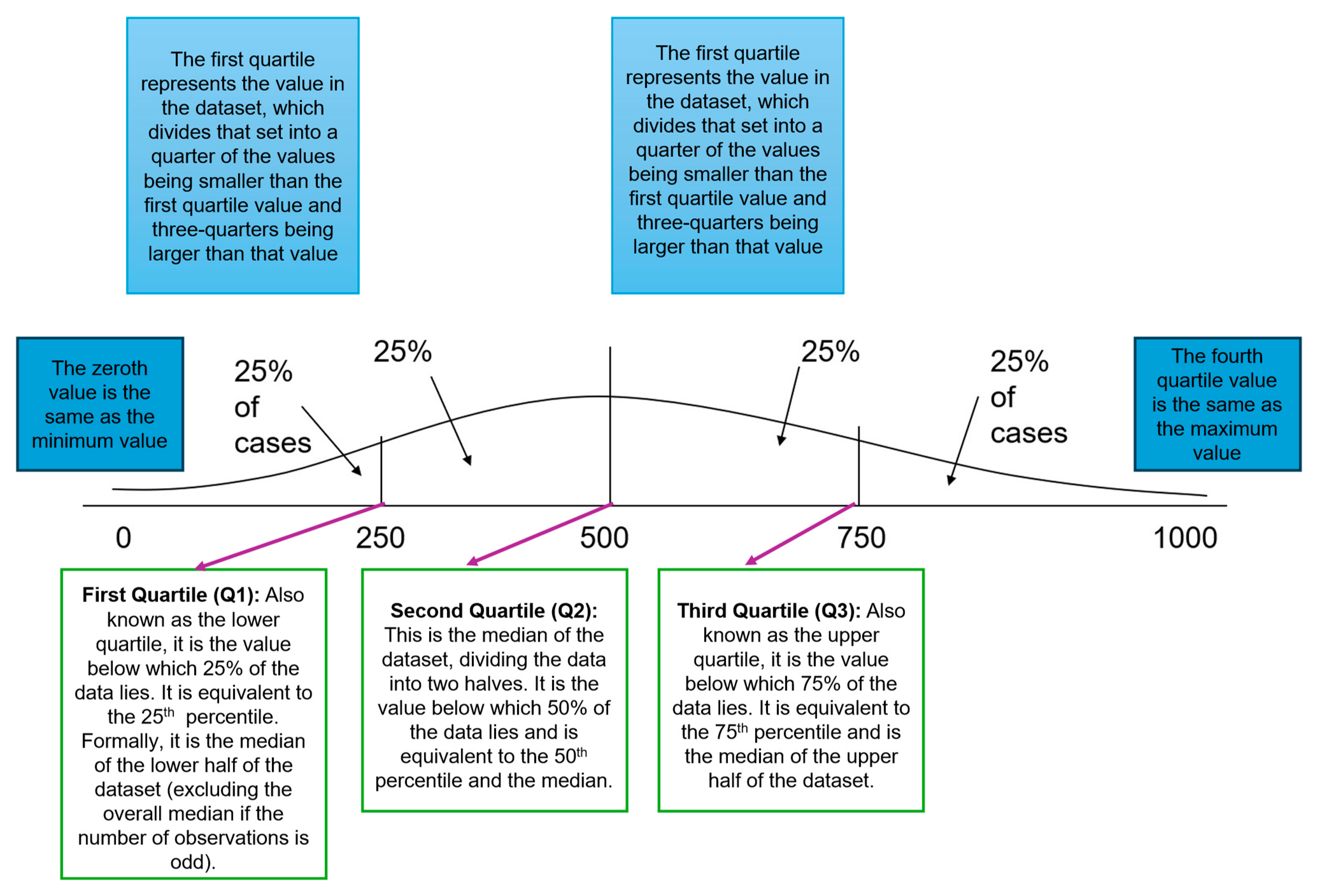

- Altman, D.G.; Bland, J.M. Statistics Notes: Quartiles, Quintiles, Centiles, and Other Quantiles. Bmj 1994, 309, 996–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for Reporting Observational Studies. The lancet 2007, 370, 1453–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, D.G. Why We Need Confidence Intervals. World journal of surgery 2005, 29, 554–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsayed, A.R.; Alzihlif, M.; Al Ramahi, J.A.W. Relevance of Vancomycin Suceptibility on Patients Outcome Infected with Staphylococcus Aureus. The International Arabic Journal of Antimicrobial Agents 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pivk, M.; Le Diberder, F.R. Plots: A Statistical Tool to Unfold Data Distributions. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 2005, 555, 356–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-hamaden, R.; Abed, A.; Khader, H.; Hasoun, L.; Al-Dulaimi, A.; Alsayed, A. Knowledge and Practice of Healthcare Professionals in the Medical Care of Asthma Adult Patients in Jordan with a Particular Reference to Adherence to GINA Recommendations. JMDH 2024, 17, 391–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, J.E.; Zhong, Y.; Duggal, P.; Mehta, S.H.; Lau, B. Defining Representativeness of Study Samples in Medical and Population Health Research. BMJ Medicine 2023, 2, e000399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsayed, A.R.; Ahmed, S.I.; Shweiki, A.O.A.; Al-Shajlawi, M.; Hakooz, N. The Laboratory Parameters in Predicting the Severity and Death of COVID-19 Patients: Future Pandemic Readiness Strategies. Biomolecules and Biomedicine 2024, 24, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Shajlawi, M.; Alsayed, A.R.; Abazid, H.; Awajan, D.; Al-Imam, A.; Basheti, I. Using Laboratory Parameters as Predictors for the Severity and Mortality of COVID-19 in Hospitalized Patients. Pharmacy Practice 2022, 20, 2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tincani, M.; Travers, J. Replication Research, Publication Bias, and Applied Behavior Analysis. Perspectives on Behavior Science 2019, 42, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsalehy, A.S.; Bailey, M. Improving Time Series Data Quality: Identifying Outliers and Handling Missing Values in a Multilocation Gas and Weather Dataset. Smart Cities 2025, 8, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

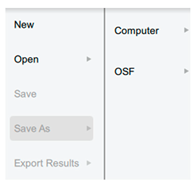

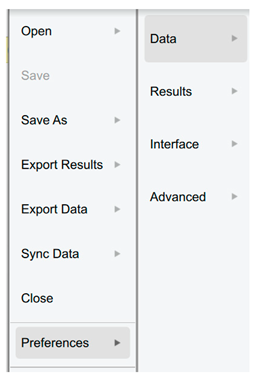

| Open JASP | |

| |

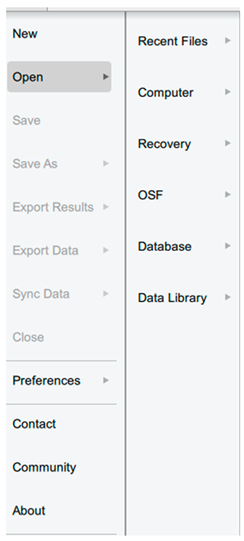

| The main menu can be accessed by clicking on the top-left icon. |  |

| Open | |

| The file formats include .csv (comma-separated values), which is a standard format for data exchange; .txt (plain text), which can also be saved in Excel; .sav (IBM SPSS data file); and .ods (Open Document spreadsheet). Users have the capability to open recent files, browse files stored on their computer, and access the Open Science Framework (OSF). Additionally, they can access a diverse selection of examples provided within the Data Library in JASP. |  |

| Save/Save as | |

| Annotations and analysis can be saved in the .jasp format. |  |

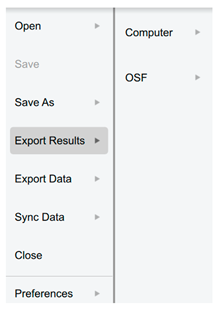

| Export Results | |

| to an HTML file. |  |

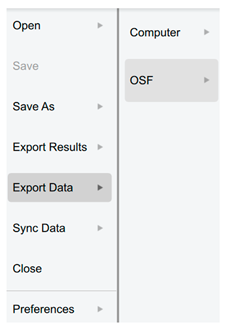

| Export Data | |

| to either a .csv or .txt file. |  |

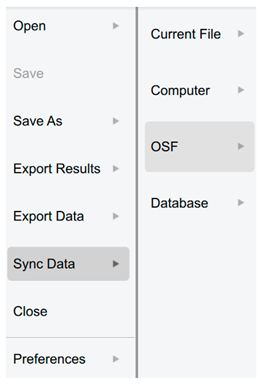

| Sync data | |

| Used to synchronise with any updates in the current data file (also can use Ctrl-Y). |  |

| Close | |

| It closes the current file but not JASP. | |

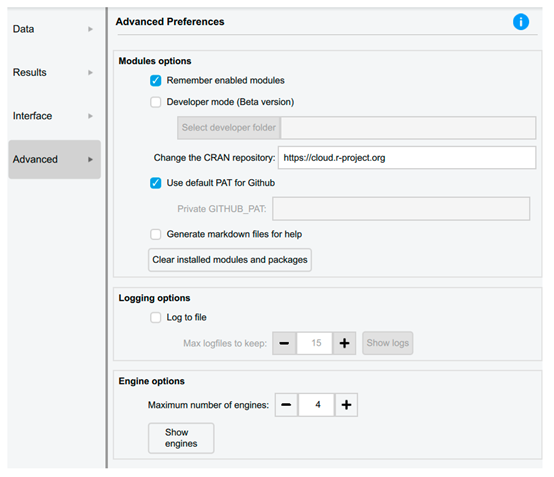

| Preferences | |

| There are three sections available for adjusting JASP to fulfil the requirements. |  |

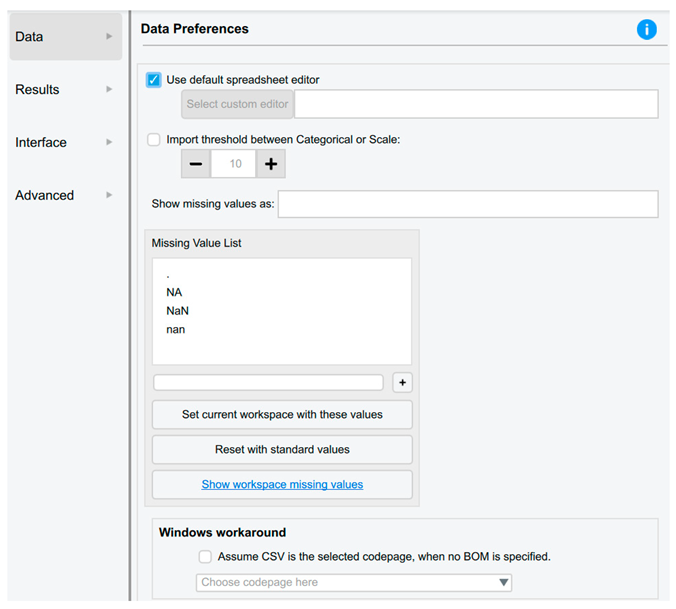

| Data Preferences | |

| The users are able to: • Automatically synchronise or update the data upon saving the data file (default setting). • Select the default spreadsheet editor, such as Excel, SPSS, etc. • Modify the threshold to enhance JASP's ability to differentiate between nominal and scale data. • Incorporate a custom missing value code. |

|

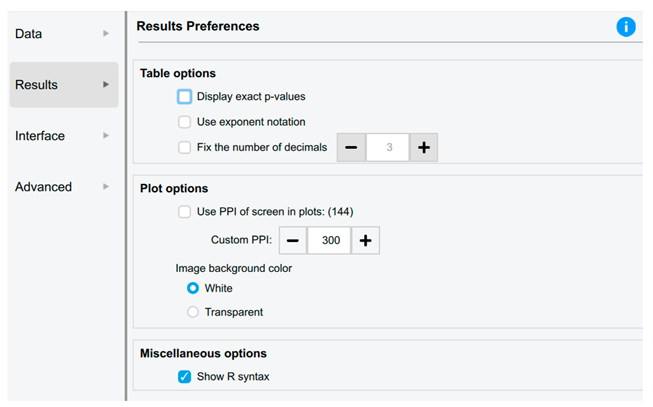

| Results Preferences | |

| The users are able to: • Configure JASP to provide precise p values, such as P=0.00056, rather than P<.001. • Specify the number of decimal places for data in tables, thereby enhancing readability and suitability for publication. • Adjust the pixel resolution of graphical plots. • When copying graphs, choose whether they have a white or transparent background. |

|

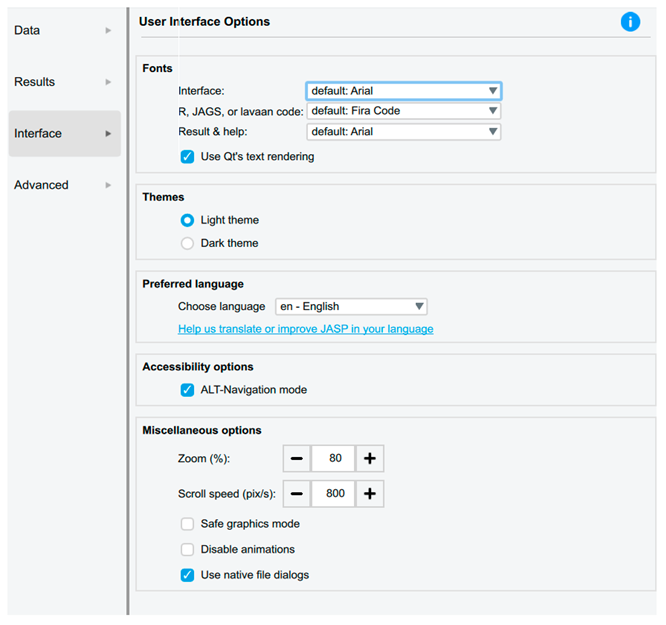

| Interface Preferences | |

| Users can adjust the user interface options to customise the system font size for improved accessibility and scroll speeds. |

|

| Advanced Preferences | |

|

|

| Icon | |

| Nominal |  |

| Nominal -Text * |  |

| Ordinal |  |

| Continuous |  |

| Type of data handling | Steps |

|---|---|

| Saving Data |

Open JASP: Launch the JASP software on the computer. Import Data: Before saving the data, we need to import it into JASP. The users can do this by clicking the "Open Data" button on the main toolbar and selecting the data file they want to analyse. Make Necessary Changes: If needed, the users can make changes to the data within JASP. This might include recoding variables, filtering data, or creating new variables. Save Data: By following these steps: Click on the "File" menu at the top-left corner of the JASP window. Select "Save As" from the drop-down menu. Choose a location on the computer where the user want to save the file. Enter a name for the file and select the file format (JASP saves data in .jasp format). Click "Save" to save the data. |

| Exporting Data |

Open JASP: As mentioned above. Prepare Data (if necessary): Ensure that the data is cleaned and organised appropriately for export. This may involve removing unnecessary variables, recoding data, or filtering rows. Export Data: To export the data from JASP, the user has to follow these steps: Click on the "File" menu at the top-left corner of the JASP window. Select "Export" from the drop-down menu. Choose the desired file format for export (options include CSV, Excel, SPSS, and R). Specify the location on the computer where the user want to save the exported file. Enter a name for the exported file. Click "Save" or "Export" to export the data, making it compatible with other statistical software or for further analysis in different programs. |

| Discrete data | Continuous data |

|---|---|

| has a finite set of values. | has an infinite number of subdivisions (for example, 1.1, 1.11, 1.111, etc.). |

| Cannot be subdivided (rolling the dice is an example; we can only roll a 5, not a 5.5). | Is mostly seen practically; i.e., although we can keep halving the number of white blood cells per litre of blood and eventually end up with a one cell, the vast numbers we are dealing with make the whiye blood cell count a continuous data value. |

| An example includes binomial values, where only two possible outcomes exist, such as a patient either developing a dosorder or not. | An example is the measurement of body weight, with the possibility of taking increasingly detailed readings depending on the equipment's sensitivity. |

| Process | |

| Recoding Variables | Identify Variables: Identify the variables in the dataset that we want to recode. These might be categorical variables with different levels or numerical variables that need to be categorised differently. Open the Variable Viewer: Click on the "Variable Viewer" tab at the bottom-left corner of the JASP window. This will display a list of variables in the dataset. Select Variable to Recode: Locate the variable we want to recode in the Variable Viewer. Click on the variable name to select it. Recoding Options: Right-click on the variable name or click on the gear icon next to the variable name to access the recoding options. Choose Recode: From the drop-down menu, select "Recode Variable." This will open a dialog box where we can specify how we want to recode the variable. Specify Recoding Rules: In the Recode Variable dialogue box, we can specify the recoding rules. This might include merging categories, creating new categories, or assigning new values to existing categories. Apply Recoding: Once er have specified the recoding rules, click "OK" to apply the changes. JASP will recode the selected variable according to our specifications. |

| Transforming Variables | Identify Variables: Identify the variables in the dataset that we want to transform. These might be numerical variables that need to be transformed to meet the assumptions of statistical tests. Open the Variable Viewer: Click on the "Variable Viewer" tab at the bottom-left corner of the JASP window to display a list of variables in the dataset. Select Variable to Transform: Locate the variable we want to transform in the Variable Viewer. Click on the variable name to select it. Transformation Options: Right-click on the variable name or click on the gear icon next to the variable name to access the transformation options. Choose Transform: From the drop-down menu, select "Transform Variable." This will open a dialogue box where we can specify the transformation we want to apply. Specify Transformation: In the Transform Variable dialogue box, we can choose from a variety of transformation options, including square root, logarithm, inverse, and others. Apply Transformation: After specifying the transformation, click "OK" to apply the changes. JASP will create a new variable with the transformed values. |

| Mean (Average) | Median |

Mode |

|---|---|---|

| Refers to the process of summing all data point values for a variable within a dataset and dividing that total by the number of values in the set. | It is a computed value positioned exactly at the midpoint of all other data points. This indicates that fifty per cent of the values are greater than this figure, while the remaining fifty per cent are lesser, regardless of their specific magnitudes. | It is the data value that appears most frequently and is used to describe categorical values |

| It represents a meaningful method for illustrating a set of numbers that lack outliers, defined as values significantly diverging from the majority of the data. | These are used when there are values that could distort the data, i.e., a few values significantly differ from the majority of the data points. | Returns the value that occurs most frequently in a dataset, which indicates that some datasets may possess more than one mode, giving rise to the terms bimodal (for two modes) and multimodal (for more than two modes). |

| Example of a dataset consists of: 5, 4, 13, 1, 66, 9, 13 | ||

| Mean = 111 divided by 7 = 15.9 | Arrange from the lowest to the highest or vice versa: 1, 4, 5, 9, 13, 13, 66 Median = 9 When the data set contains an even number of values, the median is the average of the two middle values. |

The mode is 13 |

| Measure of Dispersion | Definition and Formula | Specific Use Cases | Key Advantages | Key Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | The difference between the maximum and minimum values. Formula: R = Xₘₐₓ - Xₘᵢₙ |

• Quick, initial assessment of data spread • Quality control for process limits • Situations where extremes are critical |

• Extreme Simplicity: Easy and quick to compute • Clear boundary of data's full extent |

• Highly Sensitive to Outliers • Ignores Data Distribution |

| Interquartile Range (IQR) | The range of the middle 50% of the data. Formula: IQR = Q₃ - Q₁ |

• Analysing skewed distributions or data with outliers • Non-parametric statistics • Defining (determining) outliers and constructing box plots |

• Statistical Robustness: Resistant to outliers • Focuses on the central data portion • Applicable to ordinal data |

• Does not use all data • Limited Use in Parametric Models |

| Variance (s²) | The average of squared deviations from the mean. Sample Formula: s² = Σ(xᵢ - x̄)²/(n-1) |

• Foundational for inferential statistics • Theoretical probability and modelling • ANOVA and regression analysis |

• Uses All Data points • Mathematically Tractable (can be derived, manipulated, and used for inference using relatively straightforward and well-established mathematical operations) • Cornerstone of statistical theory |

• Squared Units • Highly Sensitive to Outliers • Less intuitive for interpretation |

| Standard Deviation (s) | The square root of the variance. Sample Formula: s = √[Σ(xᵢ - x̄)²/(n-1)] |

• Primary spread measure for normal data • Applying Empirical Rule • Confidence intervals and standard errors |

• Original Units of measurement • Comprehensive and Widely Used • Essential for precision assessment |

• Sensitive to Outliers • Assumes roughly normal distribution |

| Mean Absolute Deviation (MAD) | The average of absolute deviations from mean. Formula: MAD = Σ|xᵢ - x̄|/n |

• Robust alternative to standard deviation • Forecasting error measurement • When outlier resistance is needed |

• Robustness and Simplicity balance • Intuitively clear as average distance • Original data units |

• Mathematical Intractability • Not used in inferential formulas |

| Coefficient of Variation (CV) | The ratio of standard deviation to mean. Formula: CV = s/x̄ |

• Comparing variability across different datasets • Risk assessment in finance • Measurement system comparison |

• Dimensionless: Enables cross-dataset comparison • Scale-invariant relative measure |

• Meaningless for Mean Near Zero • Only for ratio-scale data |

| Condition | Measure |

|---|---|

| For quick assessment | Range (with caution) |

| For robust analysis (skewed data/outliers) | Interquartile Range |

| For parametric data and inference | Standard Deviation and Variance |

| For comparing different datasets | Coefficient of Variation |

| For a robust all-data measure | Mean Absolute Deviation |

|

Key Considerations: Data Distribution: Normal vs. Skewed Outlier Presence: Robust vs. sensitive measures Measurement Scale: Ordinal, interval, or ratio Analytical Purpose: Descriptive vs. inferential statistics Interpretability: Units and communication needs | |

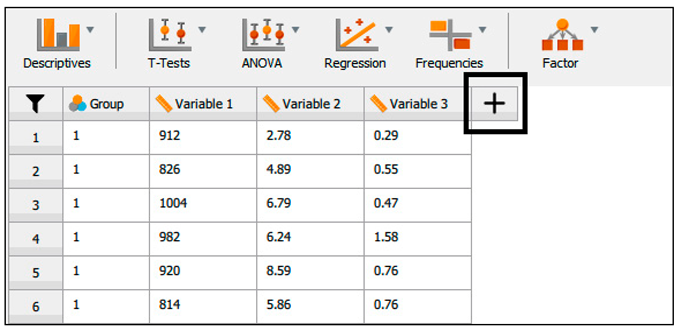

| A. | Running the data transformation. |

|

|

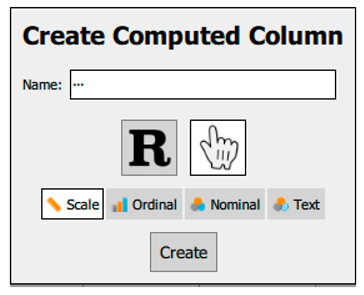

| B. | Clicking on the + opens up a small dialogue window where we can: Enter the name of a new variable or the transformed variable Select whether we enter the R code directly or use the commands built into JASP Select the suitable data type |

|

|

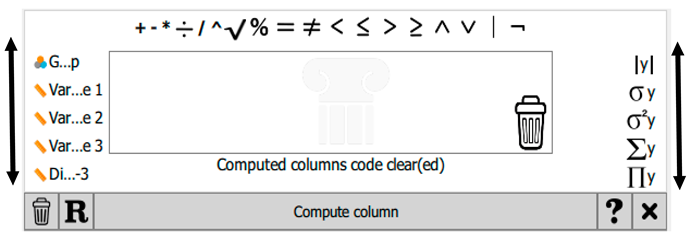

| C. | Once the new variable has been named and the other options have been selected, click 'Create'. If the manual option is chosen, this will open all the built-in creation and transformation options. Users can scroll left or right to view additional variables or operators, respectively. |

|

|

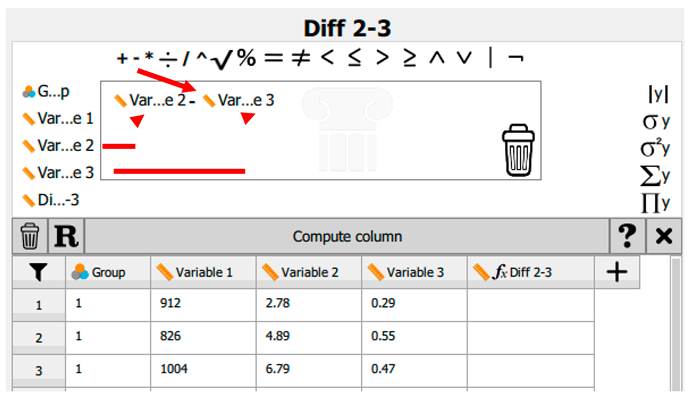

| D. | For example, if the intention is to generate a data column illustrating the difference between variable 2 and variable 3, once the column name has been entered into the Create Computed Column dialogue box, the name will be displayed within the spreadsheet window. The mathematical operation must then be specified. In this instance, variable 2 is dragged into the equation box, followed by the ‘minus’ sign, and subsequently variable 3. |

|

|

| E. | If we have made a mistake, e.g., used the wrong variable or operator, we remove it by dragging the item into the dustbin in the bottom-right corner. |

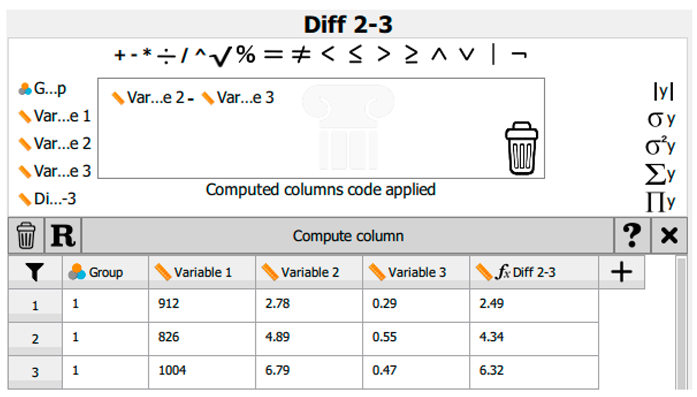

| F. | When we are satisfied with the equation/operation, we click Compute Column to enter the data. |

|

|

| G. | If we decide not to keep the derived data, we can remove the column by clicking the other dustbin icon next to the R. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).