The creation of nanoscale materials based on A15 phases, particularly those containing Ti, is important for improving their physicochemical properties. Such doped materials could be important for superconducting and adsorption-catalytic systems.

A. Adsorption energy

A literature review (2022–2025) revealed no DFT data on the adsorption energy of atomic nitrogen on titanium alloys. The existing studies consider either metals, alloys with other metals, molecular nitrogen, or conditions different from those for atomic nitrogen adsorption on the titanium alloy surface. Furthermore, to compare adsorption data with existing studies, the nitrogen adsorption conditions (temperature, coating, surface structure) must be similar. We are interested in the adsorption energy of atomic nitrogen N on the surface of titanium-containing alloys. For example, the adsorption and diffusion of atomic nitrogen in cubic α-Ti (α-Ti(0001)) were studied in [

27]. It was shown that the N atom is adsorbed on the surface of α-Ti(0001) in FCC and HCP structures. The FCC structure has a lower adsorption energy for nitrogen N atom. Doping α-Ti with aluminum (Al) reduces the adsorption capacity. However, the adsorption energy of N in α-Ti was not reported.

No such data are available for the Ti3Sb–N system. DFT calculations of N adsorption in the Ti3Sb–N supercell were considered at different surface sites (T, B, H-site). We considered four different N adsorption sites on the Ti3Sb surface. They were located: (i) directly above the surface titanium atom (T-site); (ii) midway between two nearest neighboring surface titanium atoms (bridge site); (iii) in the hollow above the titanium atom in the second layer (H-site); and (iv) in the hollow above the titanium atom in the third layer.

The nitrogen adsorption energy

(N) was calculated as the difference between the total energy of the supercell with the adsorbed nitrogen atom Ti

3Sb–N, the energies of the Ti

3Sb surface and the nitrogen atom N in vacuum:

where

is the total energy of the Ti

3Sb–N system with an adsorbed N atom,

is the energy of the Ti

3Sb plate surface,

n is the number of adsorbed N atoms,

is the energy of N atoms, respectively.

Lower adsorption energies of N atoms on the Ti3Sb surface correspond to more stable adsorption centers or sites. N adsorption on the Ti3Sb surface has a negative value.

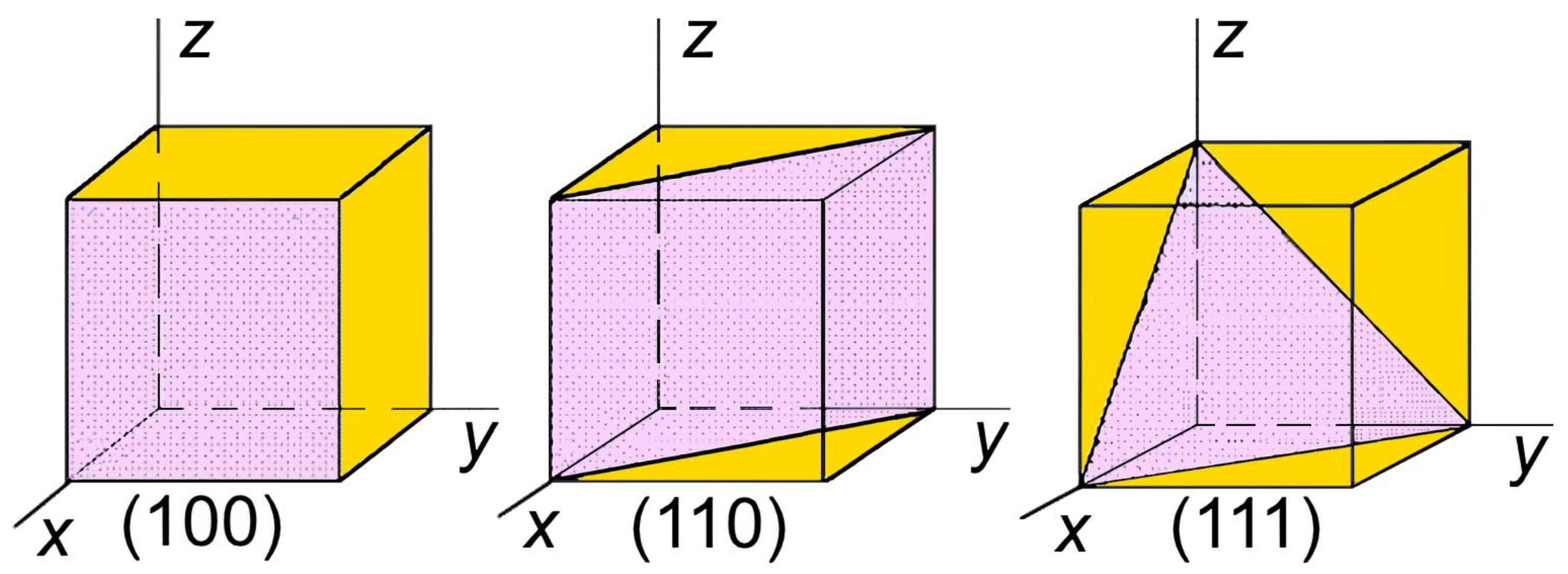

Nitrogen-containing cubic metallic structures are known to have two highly symmetric interstitial positions (octahedral (O) and tetrahedral (T)). These positions are energetically more probable for the location of adsorbed or doping nitrogen in the cubic lattice. The arrangement of the various planes in a cubic unit cell is shown in

Figure 1.

As noted above, the adsorbate coverage

is a key parameter in adsorption studies. Monolayer fractions (0 ≤

≤ 1) were used in DFT calculations. The coverage was determined by the number of adsorbed atoms on the model surface

where

is the number of adsorbed nitrogen atoms, and

is the total number of active sites on the surface. Using the cubic Ti

3Sb surface cell model, the number of sites suitable for adsorption was determined, and nitrogen atoms N 1, 2, 3, etc., were added to these sites. Each added N atom corresponded to its own

= 1/n, 2/n, etc. The periodicity of the cell model was taken into account. Adding one N atom to a given region, for example, a 2 × 2 cell, results in a coverage of

= 0.25 ML. Experimental methods for determining coverage are often used in surface physical chemistry. Coverage is determined, for example, by pressure and Langmuir isotherms

where

is the adsorption equilibrium constant, and

is the partial pressure of the adsorbate (in our case, nitrogen).

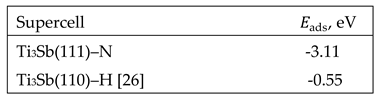

We investigated the adsorption energy

on the Ti

3Sb surface at low nitrogen concentrations. The equilibrium adsorption parameters of Ti

3Sb–N are presented in

Table 1 for a 2 × 2 supercell and a coverage of

= 0.25 ML. The

values for relaxed Ti

3Sb–N structures differ from the

of hydrogen in the Ti

3Sb–H supercell [

26].

Using the Nudged Elastic Band (NEB) method [

28], the transition state energy of nitrogen atom adsorption was determined. The distance from the Ti

3Sb surface for the adsorption of nitrogen atoms was varied in the range of 1–3 Å. The transition state structures were localized as the structures with the highest energy along the reaction coordinate, characterized by a single imaginary frequency. The adsorption activation energies differ for different faces. The activation energies for adsorption on Ti

3Sb (111), Ti

3Sb (110), and Ti

3Sb(100) are negative and are -0.07, 0.17, and -0.11 eV, respectively.

Thus, the stable N adsorption configuration on the studied Ti3Sb faces is N adsorption on top of Ti3Sb (111), with an adsorption energy of –3.11 eV. The N adsorption energies on Ti3Sb (100) and Ti3Sb (110) are –0.87 and –0.15 eV, respectively. For the Ti3Sb (100) and (110) crystallographic faces, the energetically favorable N adsorption trajectory is the bridged adsorption form (located near two adjacent Ti3Sb atoms).

The adsorption energy

of atomic nitrogen on Ti

3Sb is significantly lower than that of hydrogen (

Table 1). This may be due to several physicochemical factors.

1. Different nature of the chemical bond. Atomic nitrogen has five valence e⁻ orbitals (2s22p3 configuration), making it nucleophilic and allowing it to form a variety of bonds, including triple bonds. However, efficient nitrogen adsorption on the surface requires accessible d-orbitals with a specific energy and spatial orientation. Hydrogen, in contrast, has one electron orbital (1s), which interacts more readily with the surface, even on a metal with a low-activity substrate. It readily adsorbs on many metallic surfaces through simple donor-acceptor interactions. Conclusion: atomic nitrogen has difficulty finding a compatible orbital on the Ti3Sb surface, while hydrogen atoms easily do so.

2. Composition and electronic structure of Ti3Sb. Ti3Sb is an intermetallic compound, where Ti, a transition metal, produces d-orbitals; Sb is a semimetal with high electronegativity (~2.05), which can be considered a “sink” for Ti’s electron density. As a result, the Ti3Sb surface may be charge- and orbitally suboptimal for strong nitrogen adsorption. The d-orbitals of Ti may be partially filled and may not be available for strong bonding with N. Conclusion: the electronic state of Ti on the surface is not capable of effectively capturing and stabilizing nitrogen (including due to the strong π-electron nature of N).

3. Differences in radii and steric effects. Atomic nitrogen is larger than hydrogen but has a lower tendency to form strained bonds. However, steric effects and the arrangement of the Ti and Sb atoms may not favor a stable geometry for N. Conclusion: geometrically, Ti3Sb can be considered a substrate that does not prefer N (no convenient sites, weak orbital match, steric hindrance).

4. Thermodynamic properties of N and H. Nitrogen prefers to form N2, a molecule with high bound energy (~9.8 eV), so atomic nitrogen is very unstable and does not tend to remain alone. Hydrogen H does not have this problem, and its atomic form is easily adsorbed, in some ways “preferably” than H2. Conclusion: even if atomic N is brought to the surface, it energetically prefers to leave it or form an N2 molecule rather than create a stable adsorption configuration.

Taking into account the above reasons for the low (N) on Ti3Sb, we can conclude. There is weak orbital bonding between the N and d-orbitals of Ti, and therefore the accessibility of donor-acceptor orbitals is low. Energetically, nitrogen prefers to remain in its molecular form (N2) rather than in its atomic form. Hydrogen is more easily adsorbed on various types of surfaces. Therefore, the Ti3Sb surface is a site for very weak fixation of atomic nitrogen.

Based on these data, it can be concluded that Ti3Sb is selective and resistant to surface poisoning. Weak N adsorption means that the Ti3Sb surface will be resistant to nitrogen-containing pollutants such as NO, NO2, NH3, etc. Therefore, Ti3Sb may be a suitable material for gas-selective sensors, such as water sensors in the presence of N2, NO, NH3, etc.

On the other hand, hydrogen will be readily captured by the Ti3Sb surface, which is important for systems requiring selective H2 capture. In other words, strong H2 adsorption on the surface may indicate the potential of Ti3Sb as a material for hydrogen storage (if desorption is possible under suitable conditions) or for water separation in membrane systems.

B. Relationship between adsorption energy and activation energy

Let us consider the relationship between the nitrogen adsorption energy and the activation energy of the surface of a cubic Ti3Sb crystal. The adsorption and surface activation energies are related through the electron-structural changes in the crystal during adsorption. This demonstrates how nitrogen interacts with the surface of the Ti3Sb crystal lattice.

It is known that adsorption energy is the energy released (or absorbed) when an atom or molecule (in our case, nitrogen) attaches to a surface. depends on the nature of the surface (coordination numbers, local electron density), the type of adsorbent (N atom, N2 molecule), the presence of defects, doping, etc.

The activation energy of a surface is the barrier for a certain reaction (e.g., dissociation of N2, migration of atoms, or further doping). The stronger the nitrogen atom’s bond to the surface (the higher the ), the greater the contribution of its orbitals to the local electronic structure of the Ti3Sb surface. This can alter (decrease or increase) for the next step (reaction or nitrogen atom migration), depending on the nature of the bond (covalent, ionic, donor-acceptor).

For some simple surface reactions (especially on metals and semiconductors), there is a so-called linear Brønsted–Evans–Polanyi (BEP) relationship:

where

is the energy effect of the reaction (can be related to

),

,

are empirical constants for a given material and reaction.

In the case of nitrogen doping, if nitrogen is adsorbed with high energy and readily diffuses into the crystal, this can be considered a low activation energy for doping. For example, on the surface of cubic TiN or ZrN, where nitrogen is adsorbed with strong covalent bonds, a low energy barrier to nitrogen diffusion into the crystal bulk can be expected. On inert surfaces (e.g., oxides), weak nitrogen adsorption can correspond to a high energy barrier to N2 dissociation.

Thus, there is a relationship between and via the local electron structure and the BEP rules. However, this relationship is usually nonlinear and depends on the reaction context.

B. Alloying

Alloying and heat treatment are known to significantly improve the mechanical properties (e.g., antifriction) of titanium alloys. However, chemical-thermal nitriding can improve these properties [

19,

20,

21].

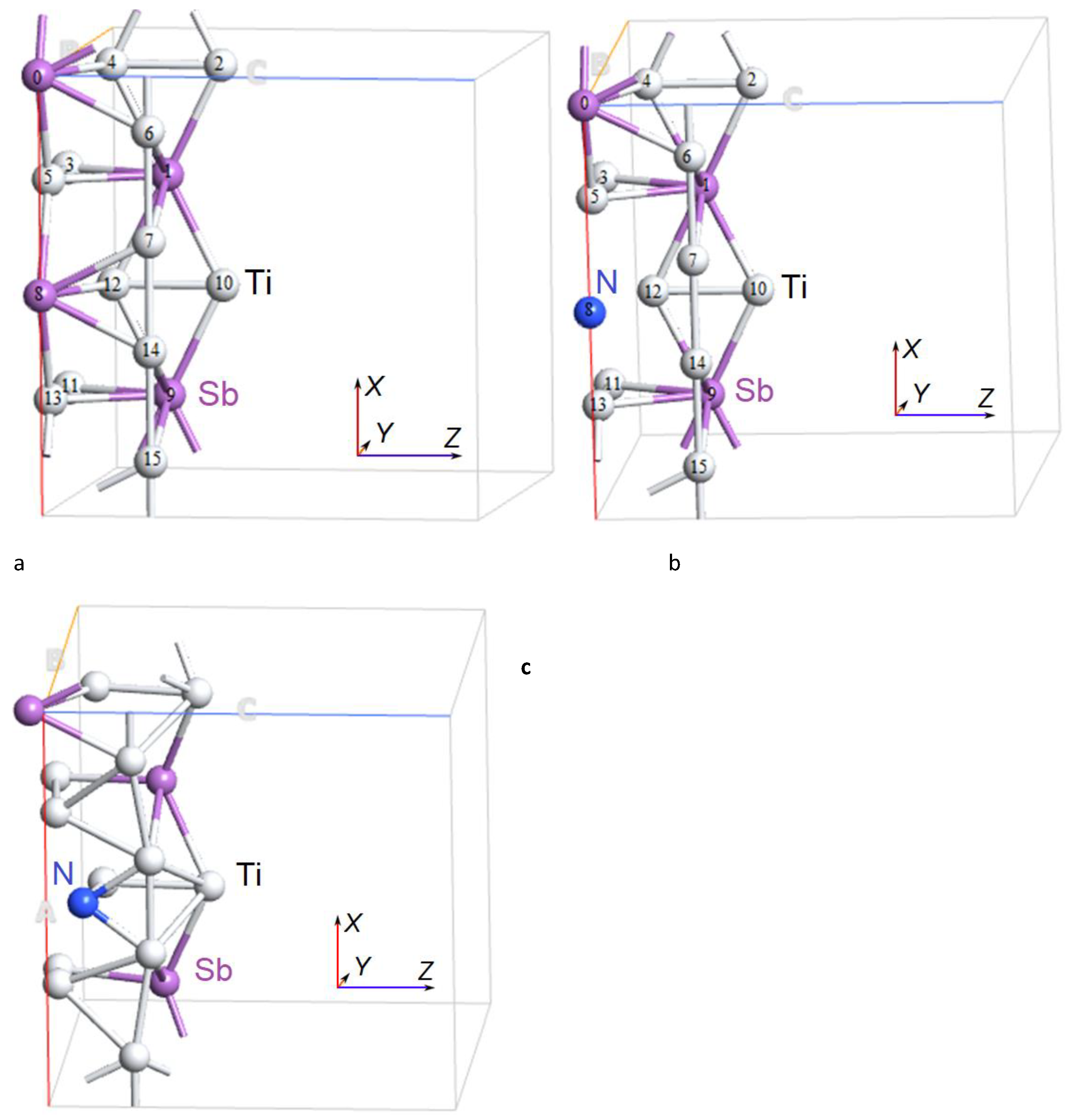

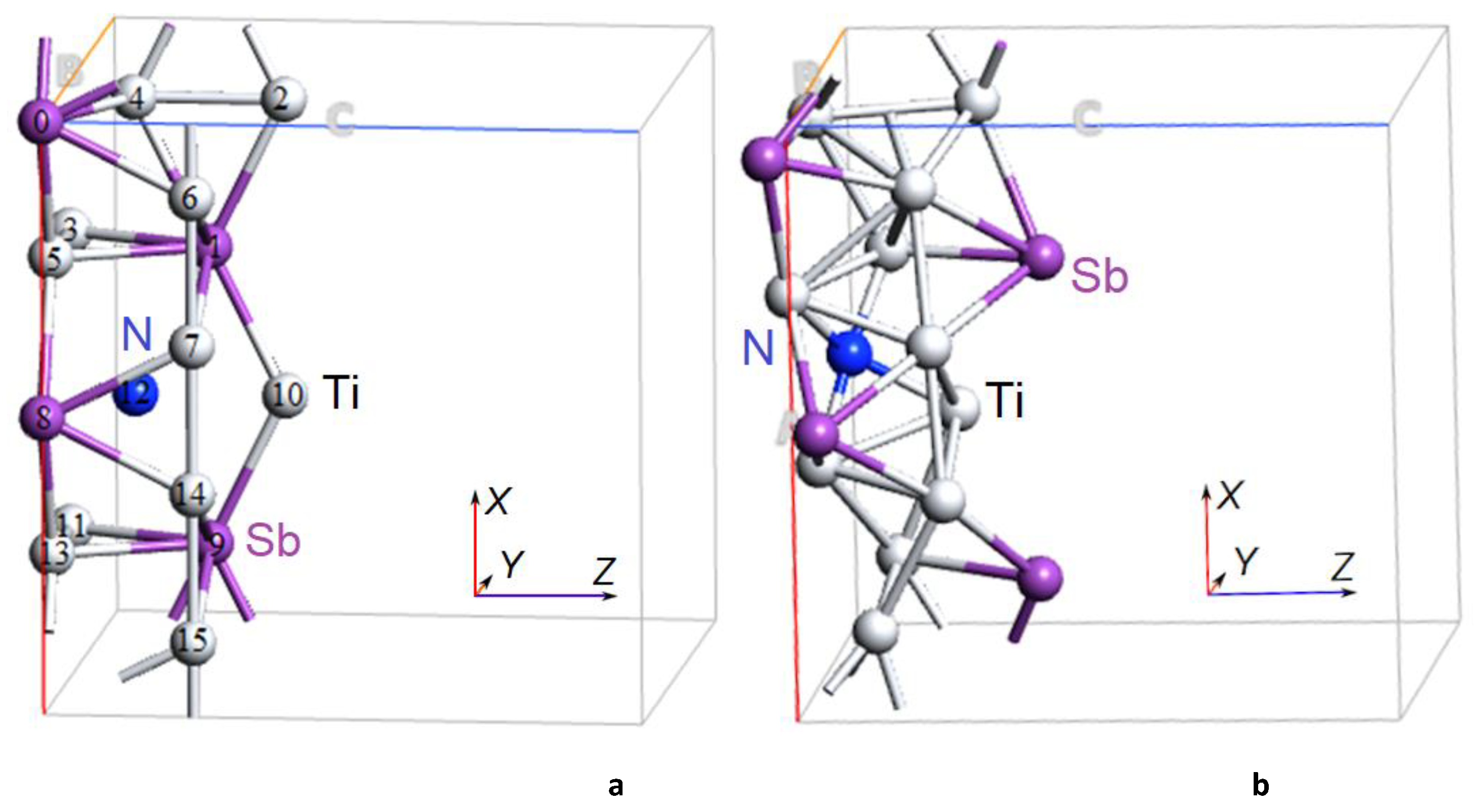

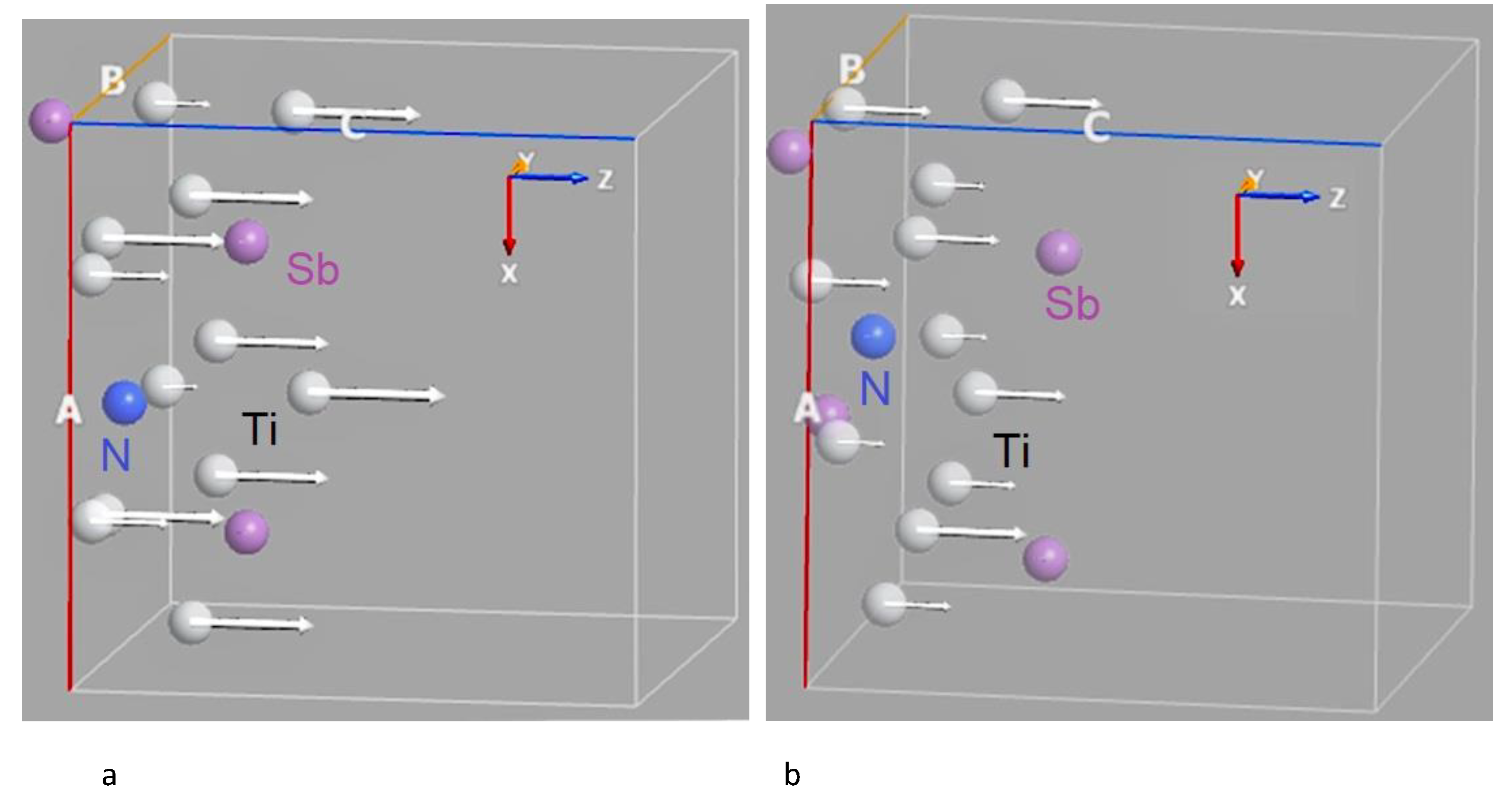

Ti

3Sb 2×1×1 supercells were modeled by doping with N atoms, where N atoms individually replace Sb (

Figure 2) and Ti (

Figure 3) atoms.

The cubic three-dimensional structure of Ti3Sb A15 can be represented as a single Ti atom bonded to two other Ti atoms and four Sb atoms in a lattice. The Ti–Ti bond length is 2.61 Å, and the Ti–Sb bond length is 2.92 Å. In this lattice, a given Sb atom is bonded to twelve Ti atoms, forming SbTi12 cuboctahedra that share edges and faces.

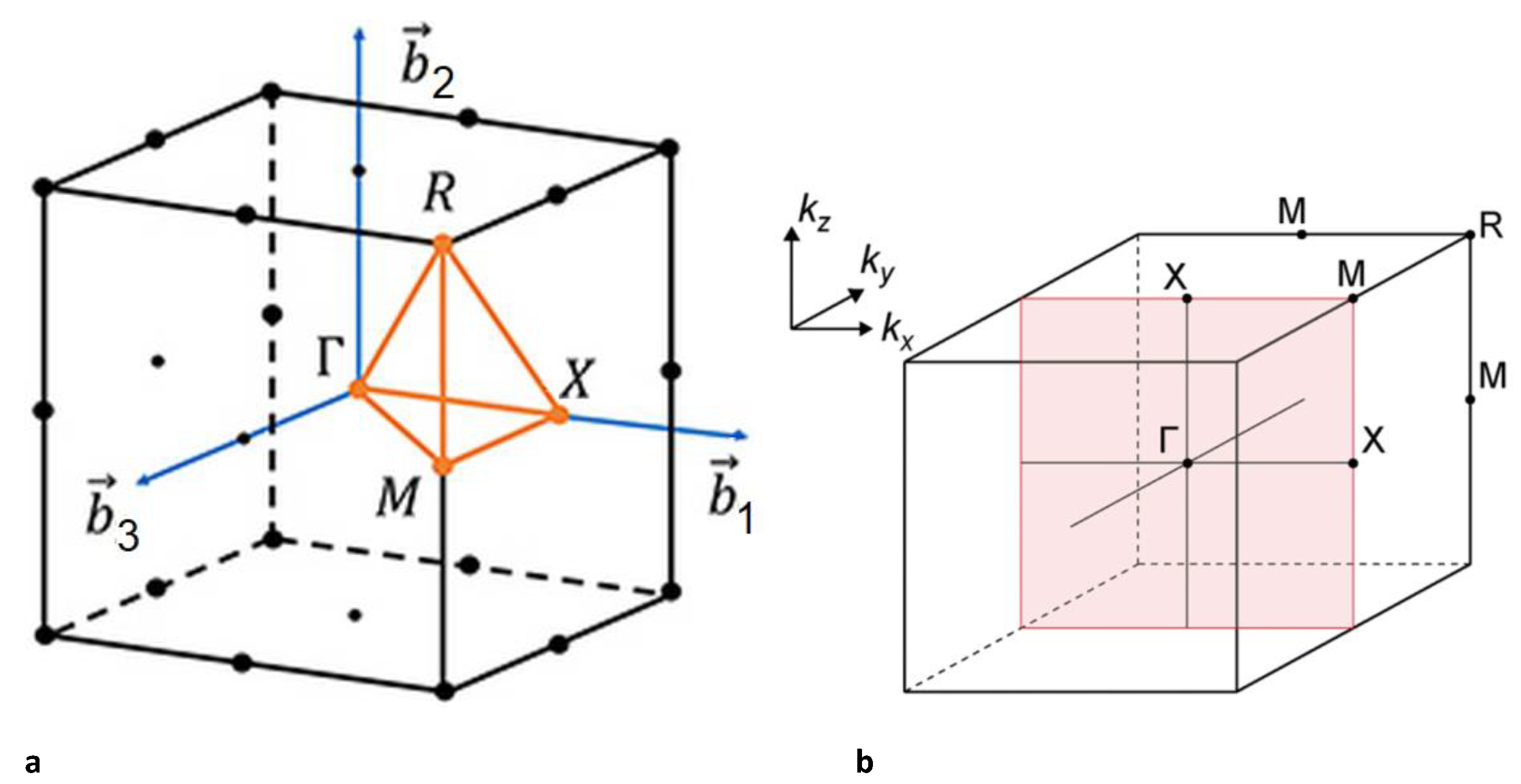

Figure 4 shows the Brillouin zone of the cubic Ti

3Sb structure, where the Γ–X–M–X plane corresponds to the

Fermi surface.

Partial replacement of Ti or Sb atoms with nitrogen atoms at the Ti

3Sb crystal lattice sites alters the structural parameters (bond lengths, electronic properties). This may be due to differences in the oxidation states and ion sizes of the components of the Ti

3Sb–N system: Ti

+3 (0.67 Å), Sb

+3 (0.76 Å), and N

+3 (0.16 Å). Thus, it has been established that partial nitrogen doping affects the interatomic distances between Ti and Sb atoms near the N atom in Ti

3Sb–N and the electronic structure (

Table 2).

In the ordered crystal structure of the Ti3Sb compound, Sb is a p-element (5 valence electrons), and Ti is a transition metal (4 valence electrons; 3d24s2). In compounds, antimony can exhibit oxidation states of -3, +3, and +5, while Ti can exhibit oxidation states of +2, +3, and +4.

Consider doping the Ti3Sb–N system with nitrogen N. Nitrogen has 5 valence electrons (2s22p3), like Sb, but the nitrogen atom is significantly smaller than the Sb atom. N has a higher electronegativity (~3.0 for N and ~2.05 for Sb). Therefore, the electron density of Ti3Sb–N(doped) can change with partial substitution of N for Sb. In this case, N more strongly attracts electrons from Ti3Sb, which can be considered as local electron depletion of the neighboring Sb (or Ti) atom. This nitriding can be considered as -alloying in the Ti3Sb crystal structure, where Ti donates electrons to the Sb atom.

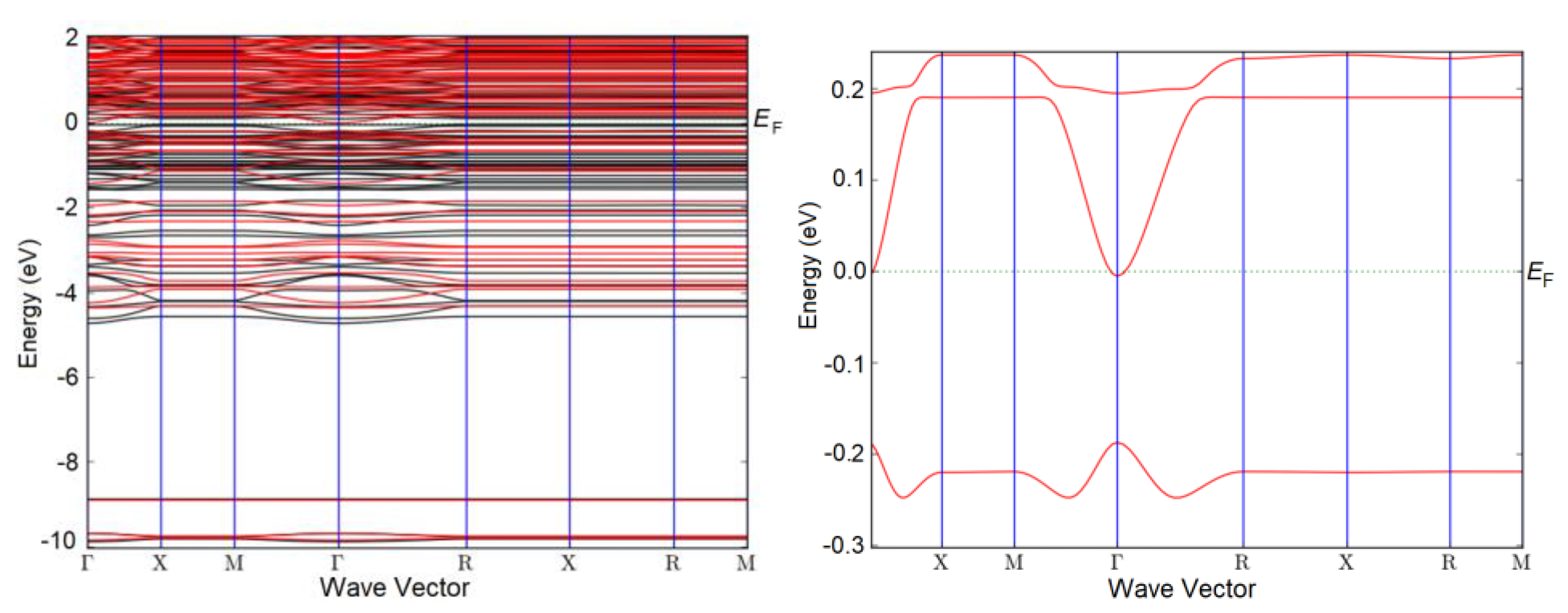

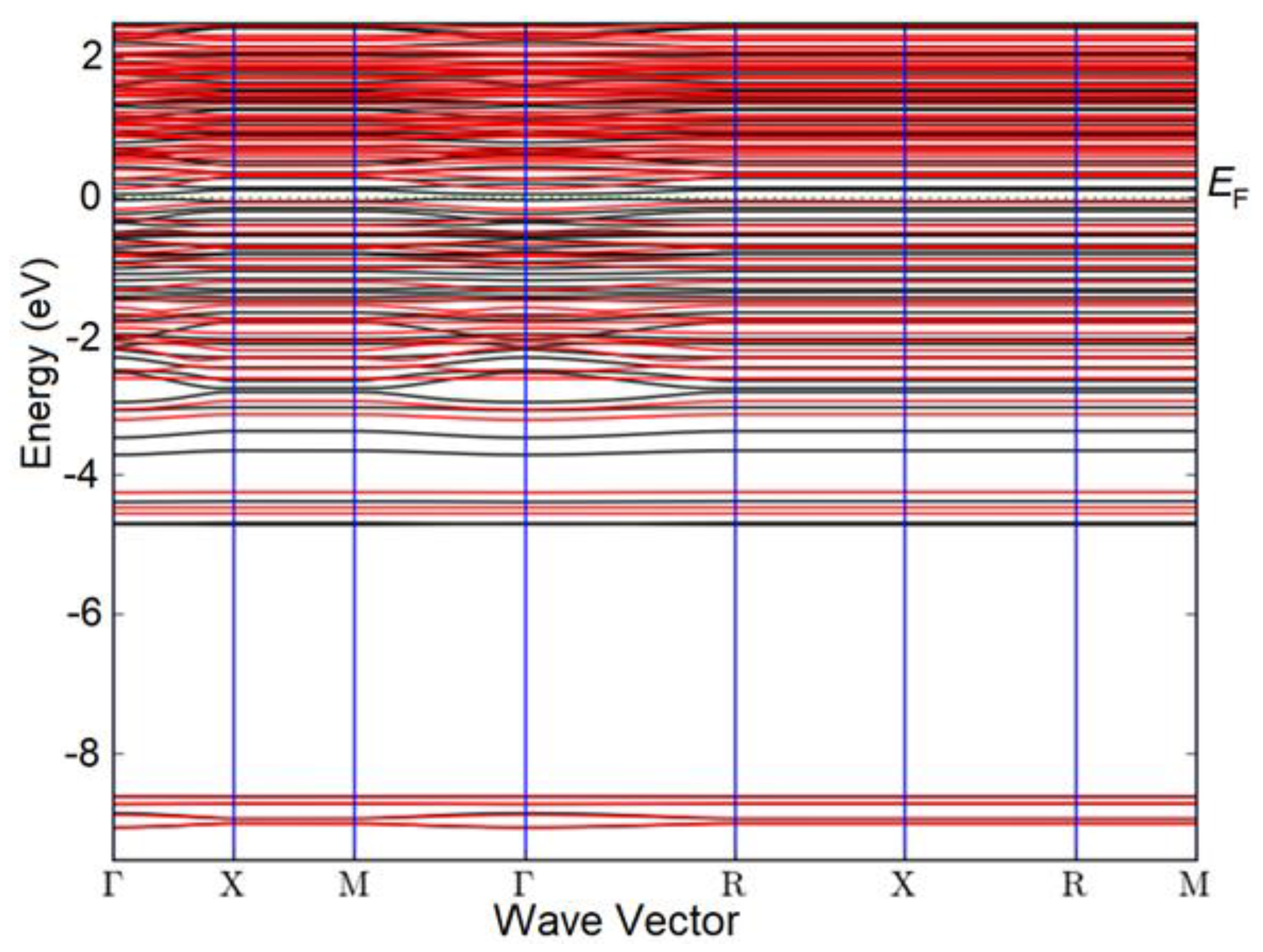

As a result of partial replacement of Sb (or Ti) by nitrogen impurity N, the electron distribution in the band structure of Ti

3Sb changes. Compared to pure Ti

3Sb [

26], local electron density bands appear in Ti

3Sb–N due to modification of the conduction band of Ti

3Sb (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6).

D. Surface anisotropy

Surface anisotropy in cubic crystals arises from differences in the atomic structure and electronic properties of the various crystallographic faces (e.g., (100), (110), (111), even if the crystal has high symmetry in the bulk.

In general, electron anisotropy in crystals with a cubic structure can arise due to:

- anisotropy of the electron effective mass (near band minima);

- the crystal potential, which, although symmetrical on average, can lead to a directional dependence of properties (for example, due to the band structure);

- spin-orbit interaction;

- crystal deformations (mechanical stress);

- the presence of impurities or defects that break symmetry.

Cubic structures (FCC, BCC, SC, DC, NaCl, TiN, etc.) have high volumetric symmetry. Different faces have different numbers of neighbors, angular bonds, packing density, etc. As soon as the crystal is destroyed and a surface is created, the symmetry of the bulk crystal is broken. In other words, the formation of a surface disrupts the symmetry of the crystal.

As an example, let’s consider the FCC structure. The (111) surface direction is the region with the highest packing density, is stable, and has a low (100) is a finer packing, with more uncanceled bonds → higher (110) has even more bond breaks → higher These differences lead to different surface energies . This is called surface energy anisotropy.

After the surface is formed, the atoms relax, changing the interatomic distances and local electron density. The (111) face can relax differently than the (100) face; this is called electron anisotropy. In metallic systems (e.g., FCC Ni, Cu), anisotropy is formed due to d-electrons, which are distributed differently on different faces. In ionic crystals (e.g., NaCl, TiN), anisotropy is formed due to the uneven distribution of ions on different garnets. In covalent crystals (e.g., C, Si, Ge, Sb), anisotropy is formed due to the different topologies of chemical bonds (for (111) and (100)).

The higher the atomic density at the boundary (Miller indices and packing density), the higher the protection of the surface atoms and the lower the surface energy of the crystal, i.e., the more stable the facet. The general dependence of surface energy on facet and packing density for the FCC cubic structure is presented in

Table 3.

Thus, surface anisotropy is the difference in surface energies of different planes:

The value of γ can be calculated using the DFT method for each plane of the supercell:

Although cubic symmetry theoretically implies isotropy, real crystals exhibit anisotropic behavior due to:

- differences in the effective mass of electrons along different directions;

- electron bands, which can have an ellipsoidal shape (for example, in silicon, the conduction bands have six ellipsoids along the [100] axes);

- spin-orbit splitting, especially in heavy elements.

Conclusion. Surface anisotropy of cubic crystals is due to differences in geometry (atomic density, bond cleavages), electronic properties (local density of states, relaxation), and crystallography (face indices).

Let’s consider the DOS taking into account crystallographic directions, for example, in a cubic crystal. DOS is a scalar quantity that depends on energy but not direction. However, the anisotropy of the band structure means that the contribution to DOS from different crystallographic directions can differ.

That is, the DOS itself does not explicitly depend on direction, but the group velocity, dispersion , and other crystal characteristics can be significantly directional. In the isotropic case (e.g., free electrons) is independent of direction. In a crystal, due to the complex shape of the bands, the bands can be denser in states in certain directions. For example, if the dispersion in [111] is flatter than in [100], then there are more states at the same energy.

The influence of cubic crystal directions manifests itself in the following cases: Partial density of states (PDOS) – if we consider the contribution from specific atomic directions (orbitals). Fermi surface orientation – different directions produce different surface cross-sections, which influence the electron density. Anisotropy of transport properties – for example, thermoelectric properties or thermal conductivity of the crystal.

Thus, electron anisotropy arises from differences in the dispersion of despite cubic symmetry; this is determined experimentally or through band calculations. The DOS is generally a scalar, but the band shape and dispersion anisotropy contribute to the DOS, making it directionally dependent. This manifests itself in the transport properties and DOS spectra.

There is no universal formula for the DOS for anisotropic electrons. For this, we will use the theory and the effective mass tensor. The DOS for the isotropic case of free electrons with parabolic dispersion is

Then in three dimensions for the kinetic energy density of an electron we can write:

where

is the bottom of the zone or the level relative to which the energy is calculated. This expression assumes that the effective mass

is the same in all directions.

The DOS for the anisotropic case will include the anisotropic effective mass and the mass tensor. If the dispersion is anisotropic, then for small deviations from the zone minima:

where

are the components of the inverse effective mass tensor.

If the system allows the selection of principal axes, the mass tensor becomes diagonal:

where

,

are the effective masses along the principal directions.

In a cubic crystal, with complete symmetry, should be true. However, due to the peculiarities of the zone, there may be cases where different directions of the crystal are poorly approximated by a single mass.

Therefore, let’s consider the DOS for the anisotropic case in terms of the mass tensor. For the case with a diagonal mass tensor, the DOS expression is:

where the integration is over the surface of constant energy

.

Substituting the parabolic anisotropic form into this expression, we obtain:

After transformations, the final result for small deviations is obtained in the form:

or:

That is, the effective DOS mass in the anisotropic case is the geometric mean of the masses in three directions in the crystal:

Taking this into account, the DOS expression in the anisotropic case can be written similarly to the isotropic case, but with the contribution of .

Notes and limitations. This formula is valid only near the band minimum, when the dispersion can be considered parabolic in three directions of the crystal. If the dispersion is significantly non-parabolic, or if the bands are significantly curved, then exact integration over the surface =const or numerical methods (e.g., DFT, special packages for DOS calculations) should be used.

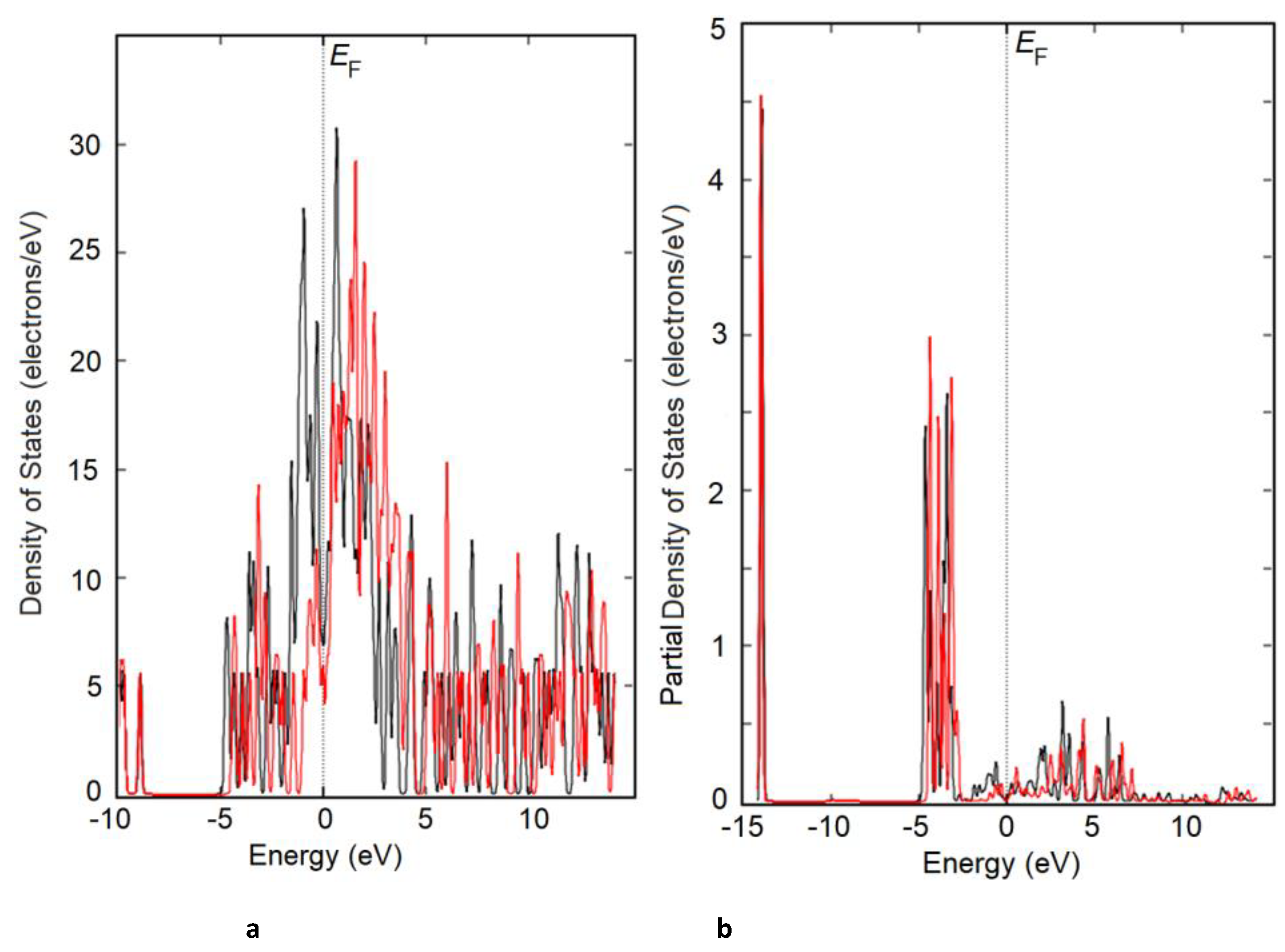

The DOS spectra of Ti

3Sb–N along the Γ–X direction of the wave vector differ from each other, as can be seen from

Figure 7 and

Figure 8. They also differ from the DOS spectra of the pure Ti

3Sb supercell [

25]. In addition to the Sb 5

p valence bands located approximately 5 eV below the Fermi energy

, the intensity of the peaks near

at the Γ point (

Figure 9) can be due to the 3

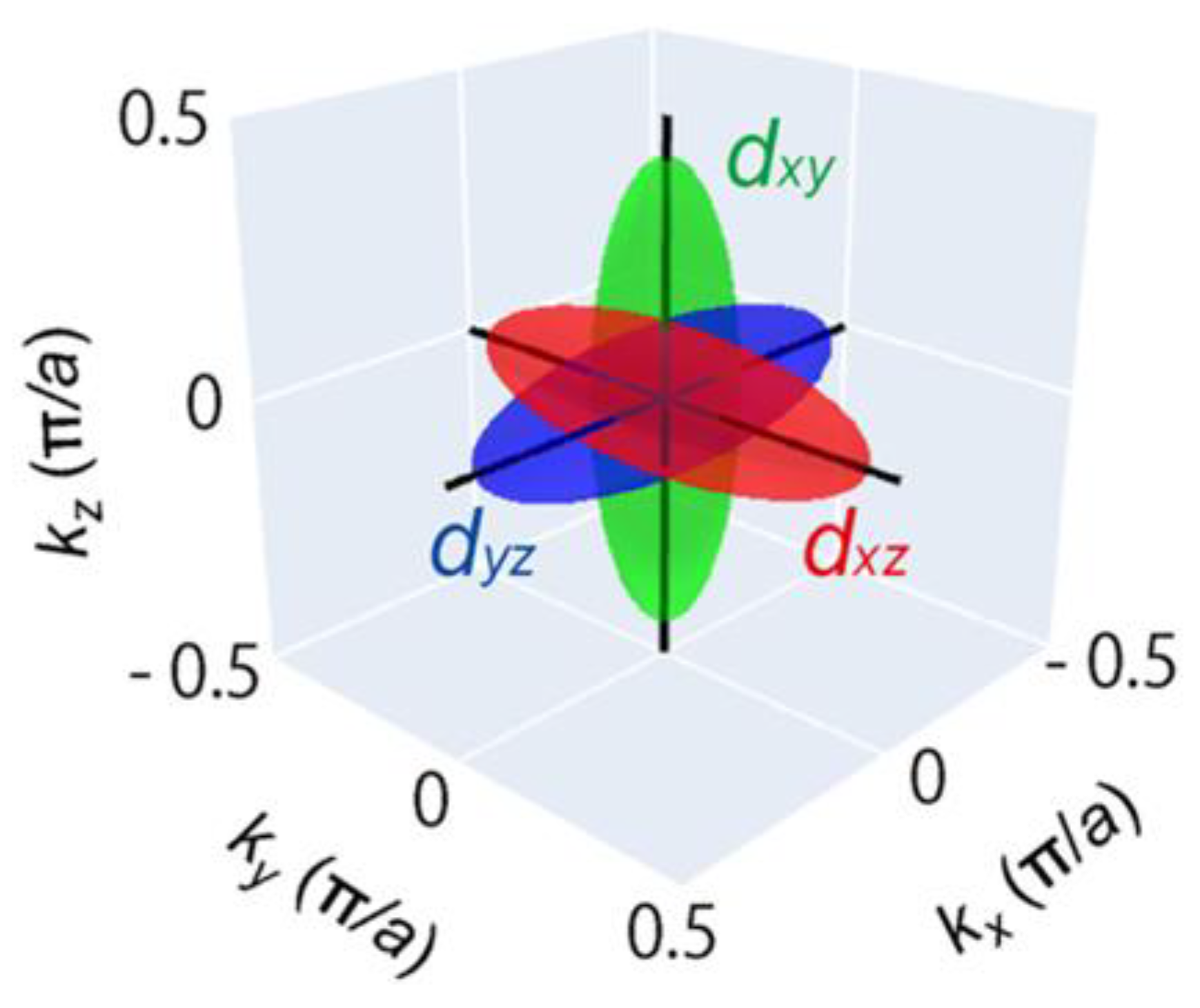

d-t

2g states (

Figure 10) characteristic of Ti, occupied by the electrons of the N dopant.

The anisotropic dispersion of the electron pocket bands t

2g of cubic crystals containing titanium [

29] can be expressed in terms of the effective mass model:

where ℏ is the reduced Planck constant.

Taking this into account, as well as the sixfold degeneracy of the t

2g bands due to spin and orbital degrees of freedom, the electron carrier density for occupied states in Ti

3Sb–N can be estimated as:

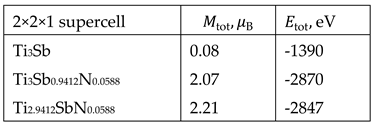

The stability of the obtained Ti

3Sb–N structures with partial substitution of Ti3Sb components with nitrogen was estimated by calculating the formation energy:

where

is the formation energy,

and

are the total energies of nitrogen-doped Ti

3Sb and pure Ti

3Sb, respectively;

are the chemical potentials of the dopant nitrogen and the Ti and/or Sb components, respectively;

is the number of Ti or Sb atoms replaced by the dopant nitrogen atom.

The calculations assume that the dopant nitrogen atoms replace Ti or Sb atoms. The ratio of the chemical potential [

30] is defined as

. Calculation results showed that partial replacement of Ti or Sb in the Ti

3Sb lattice with nitrogen impurity atoms leads to a negative formation energy for Ti

3Sb–N structures. On average,

= -0.32 eV for these structures. This indicates favorable incorporation of nitrogen impurity atoms into the Ti

3Sb crystal lattice. DFT LSDA calculated

of pure Ti

3Sb is

= -0.38 eV/atom [

25].

The calculated energy levels remain nearly identical for both spin-up and spin-down states in the density-of-state spectra of Ti

3Sb–N (Figures 8, 9). That is, these energies for both spin orientations differ little from each other in Ti

3Sb–N. The band gap for Ti

3Sb–N, calculated based on highly symmetric k-points, is 0.009 eV. A local magnetic moment was detected in Ti

3Sb–N using the Mulliken method (

Table 4).

Both nitrogen adsorption on the surface and the incorporation of the nitrogen atom into the lattice of the cubic Ti3Sb A15 crystal can also depend on the anisotropy and crystallographic orientation of the structural planes. These data can be used to specifically control the electronic, mechanical, and catalytic properties of Ti3Sb-based materials. These findings are important for the development of new nitrogen-containing functional materials that are resistant to oxidation and suitable for applications such as electronics, catalysis, and sensors.