Submitted:

06 November 2025

Posted:

10 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Works

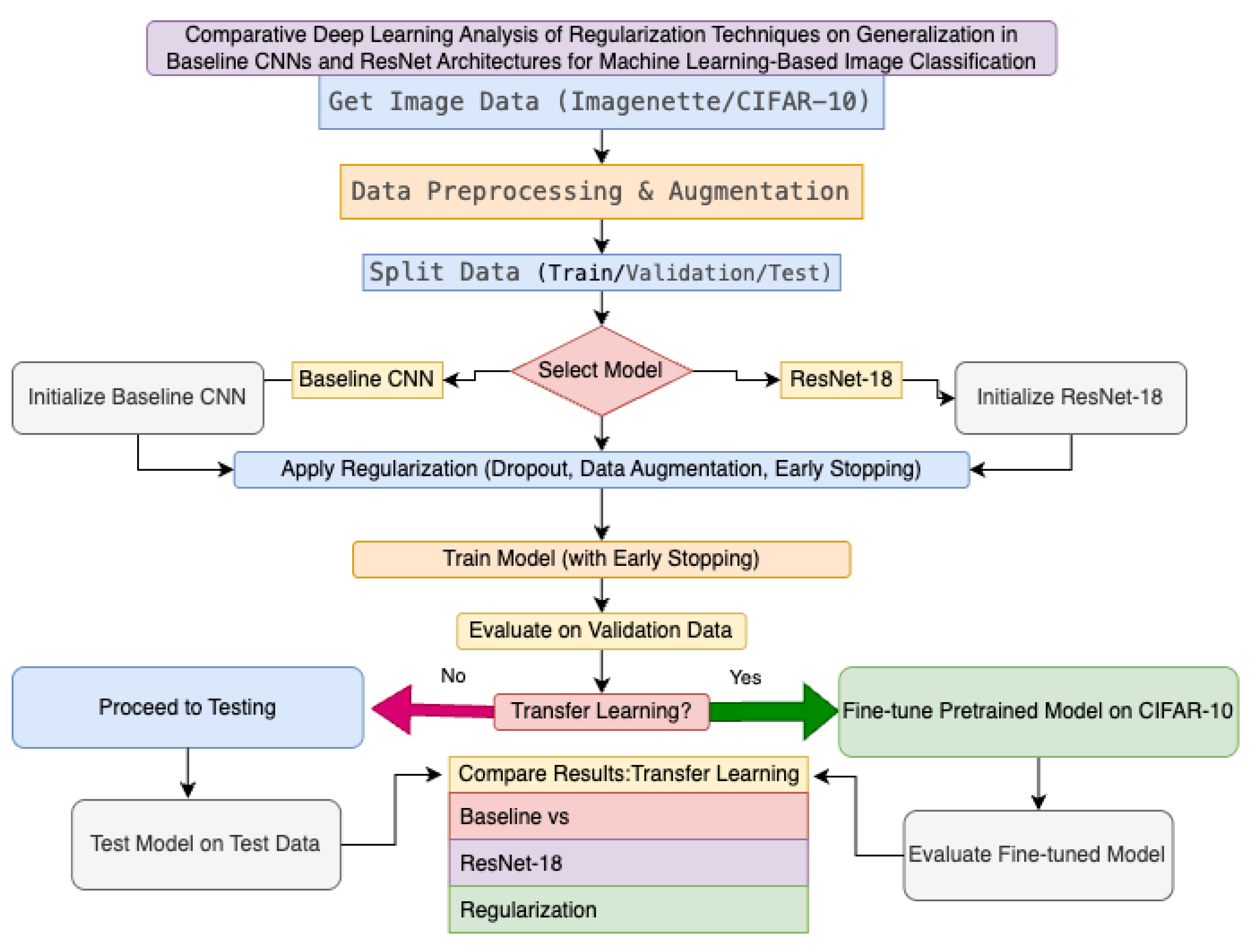

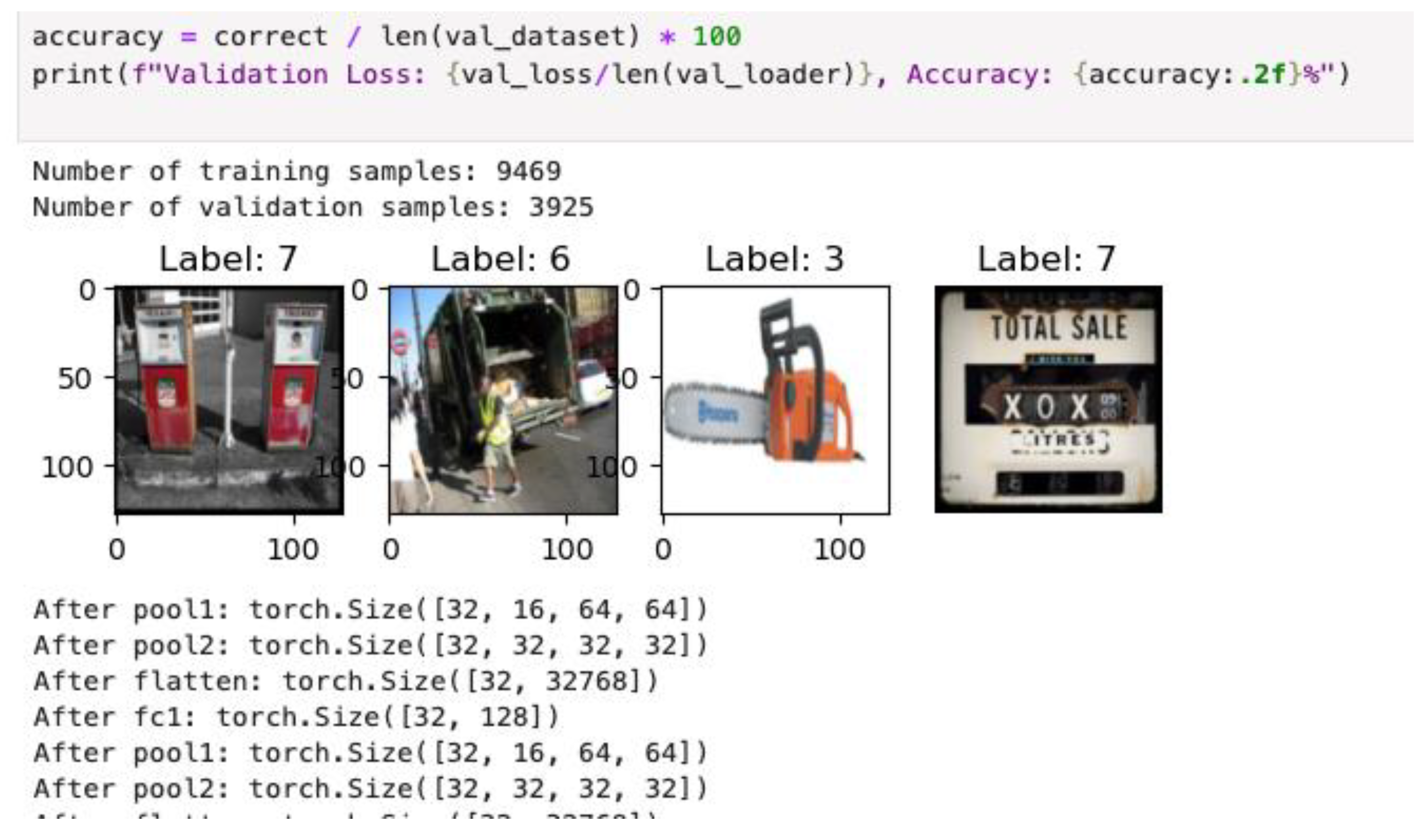

3. Methodology

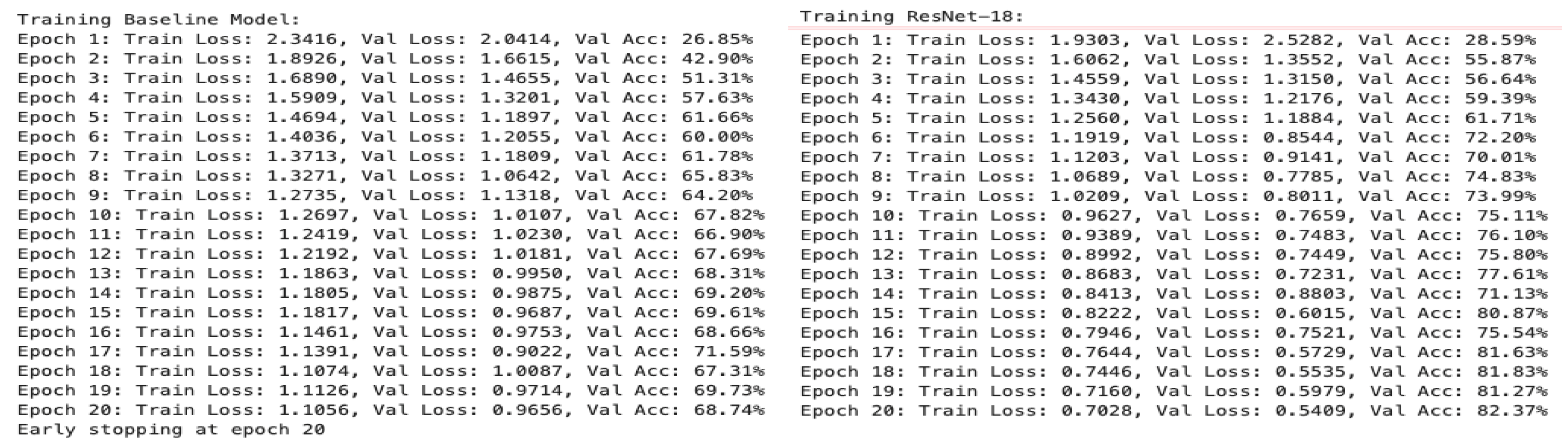

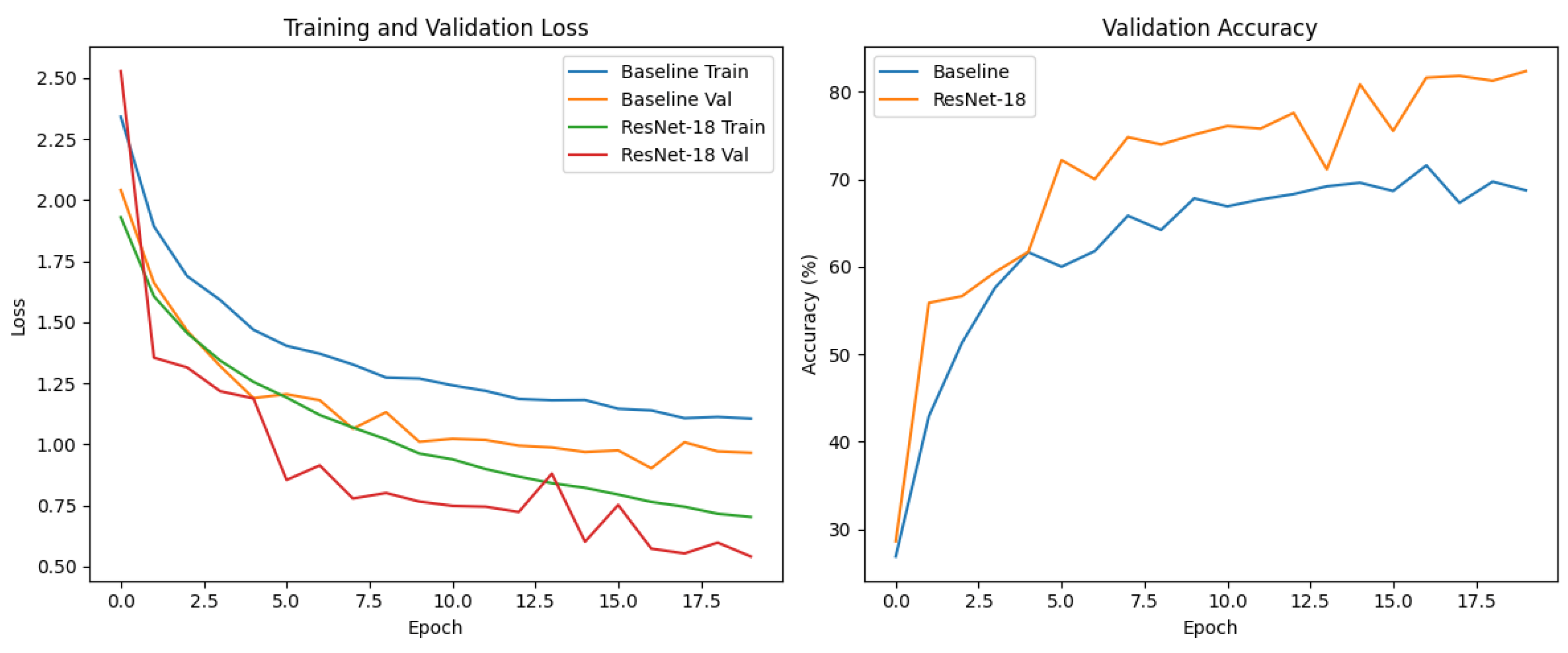

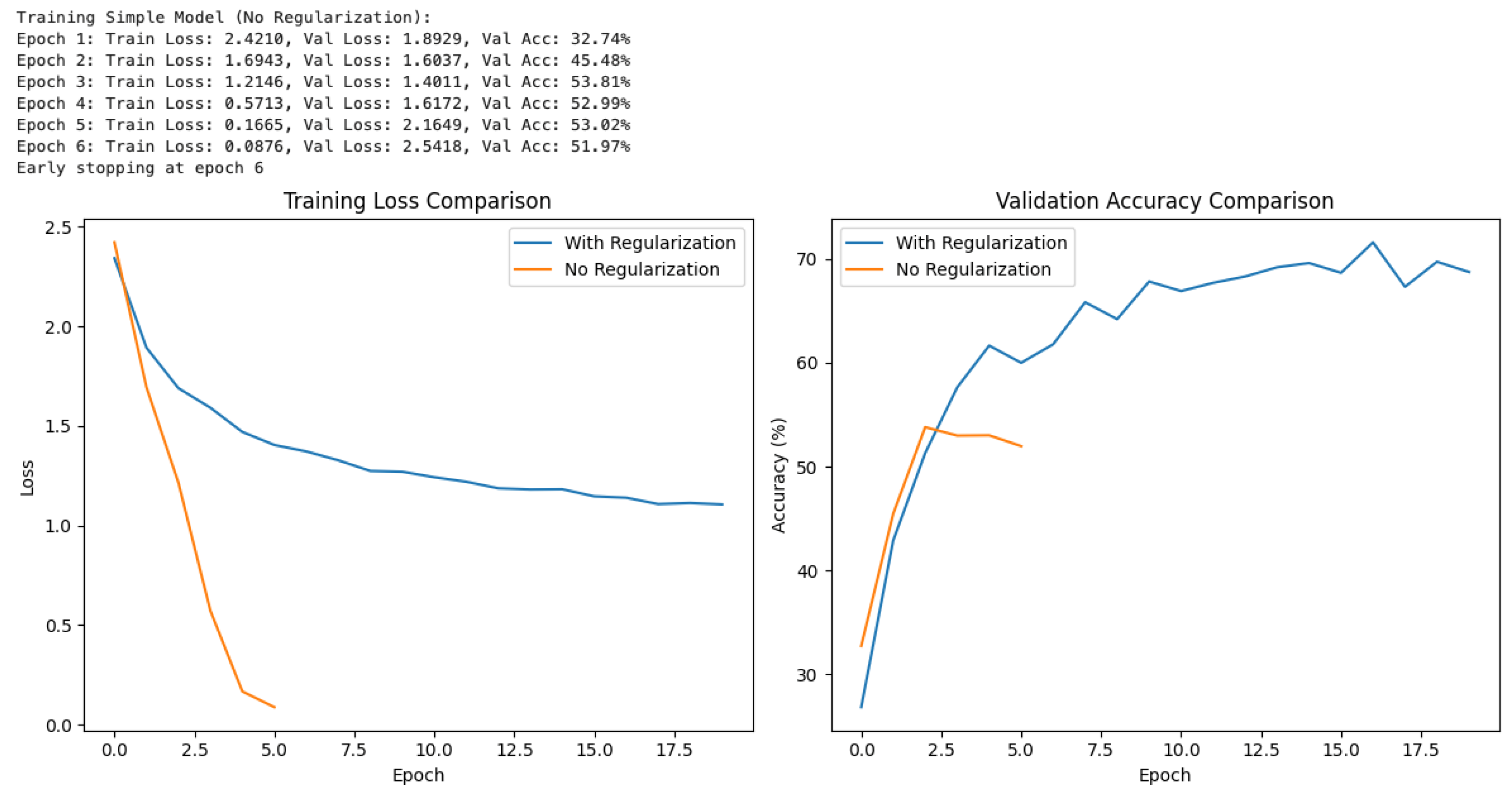

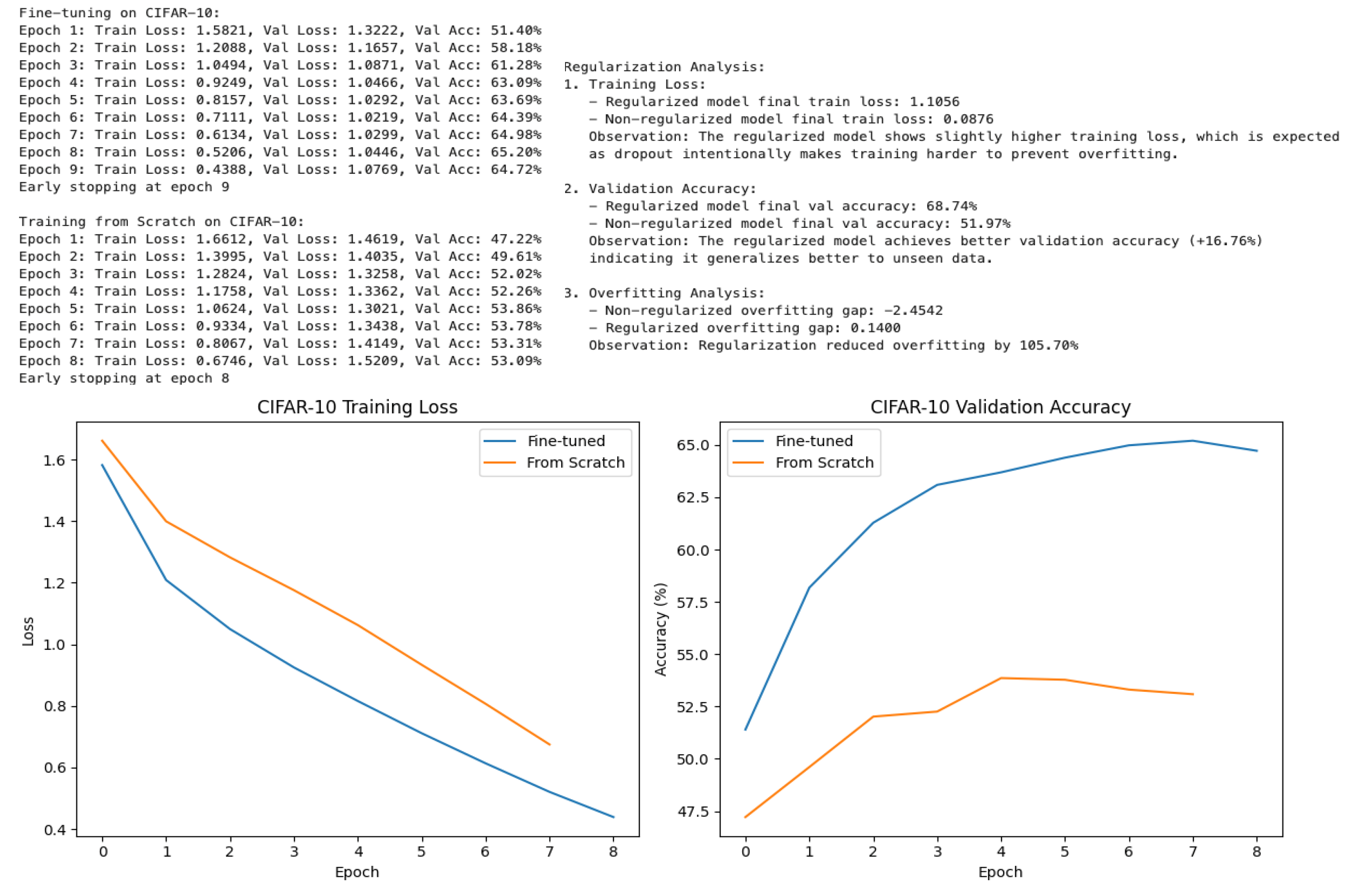

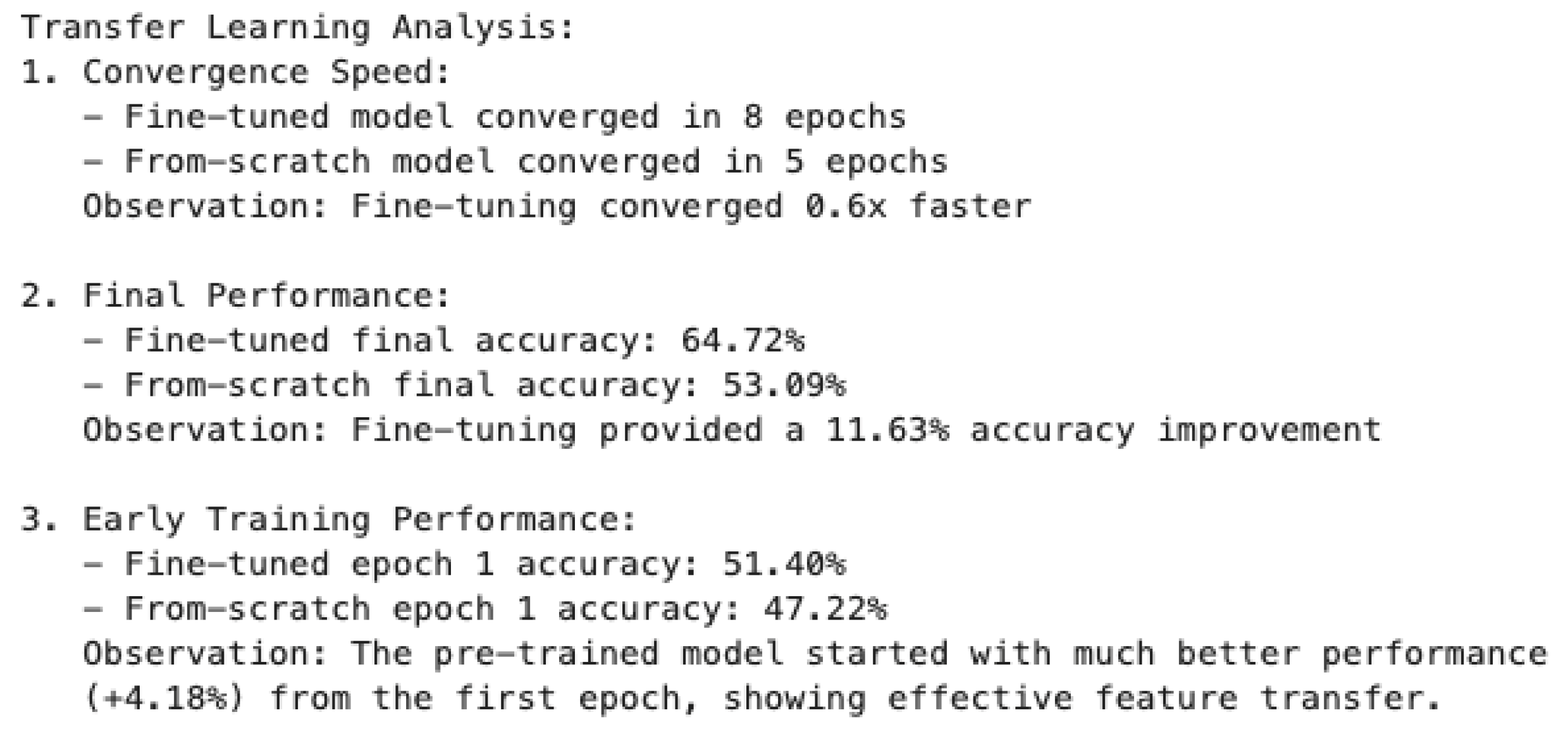

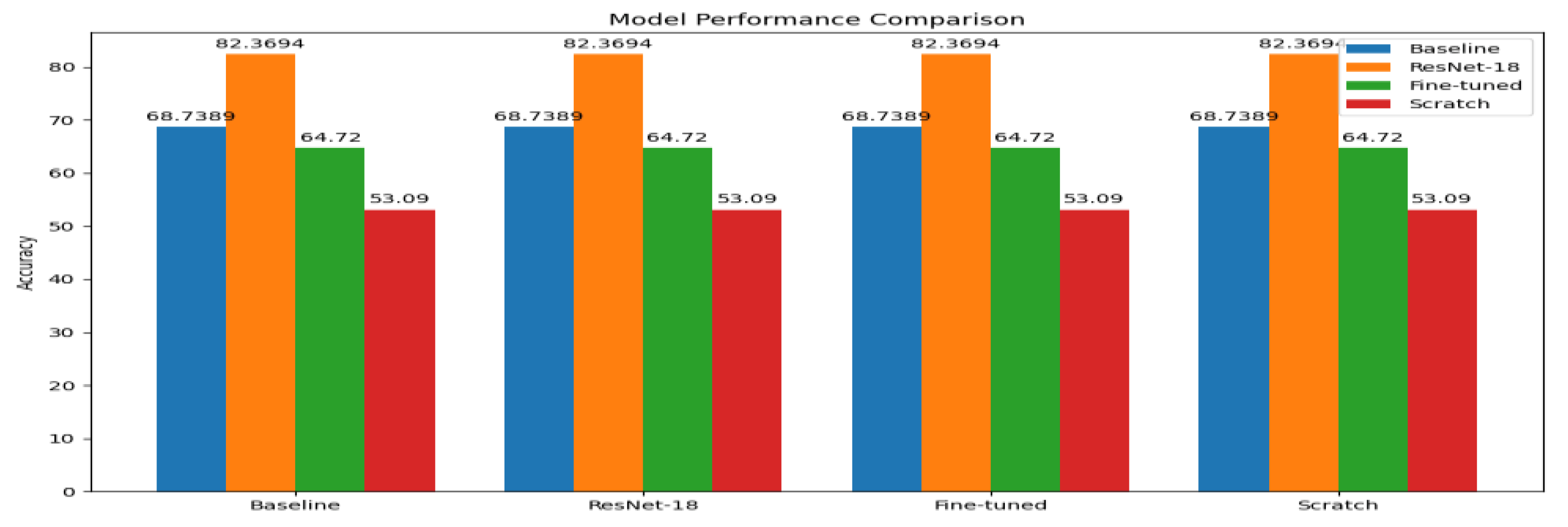

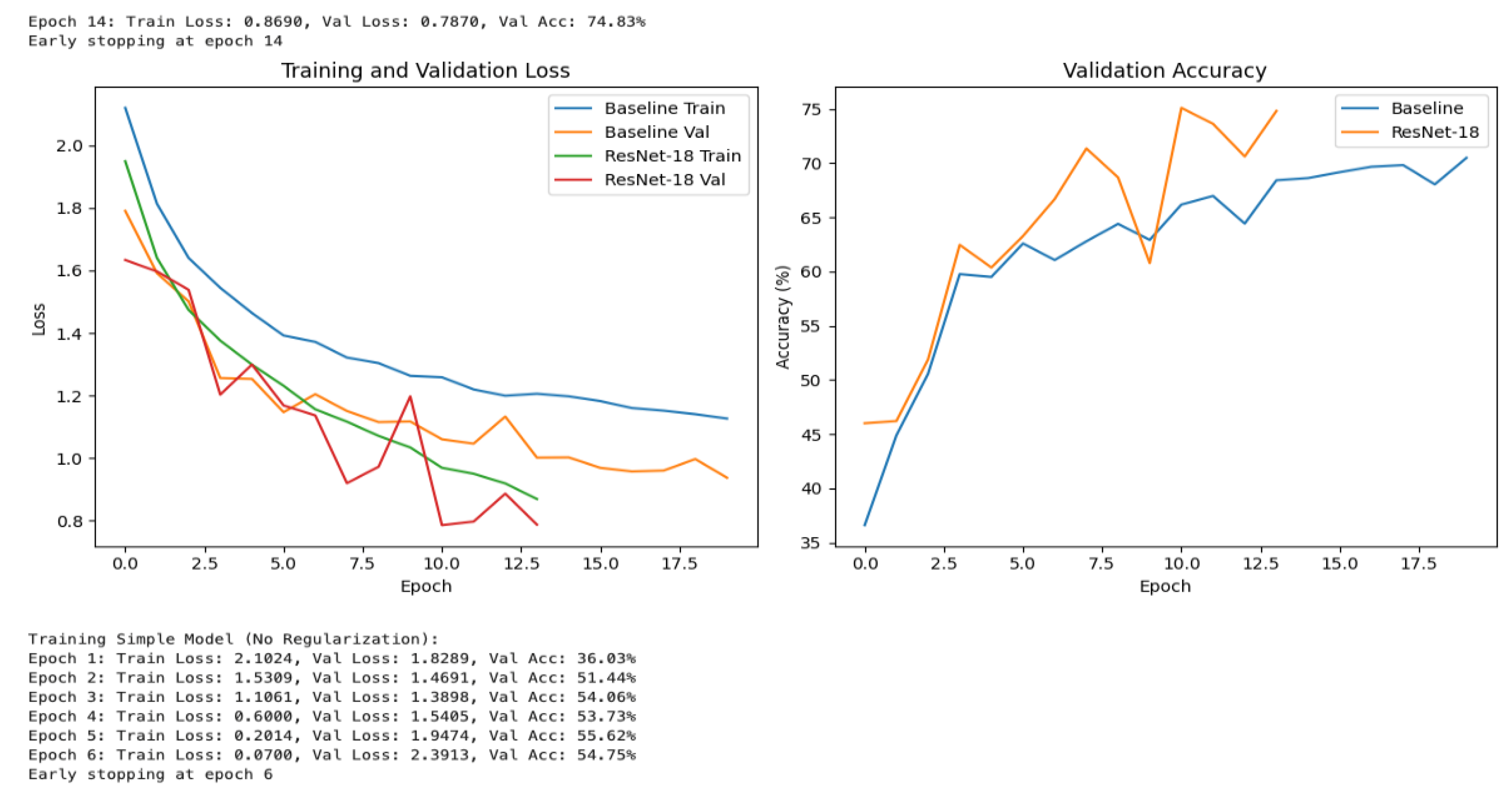

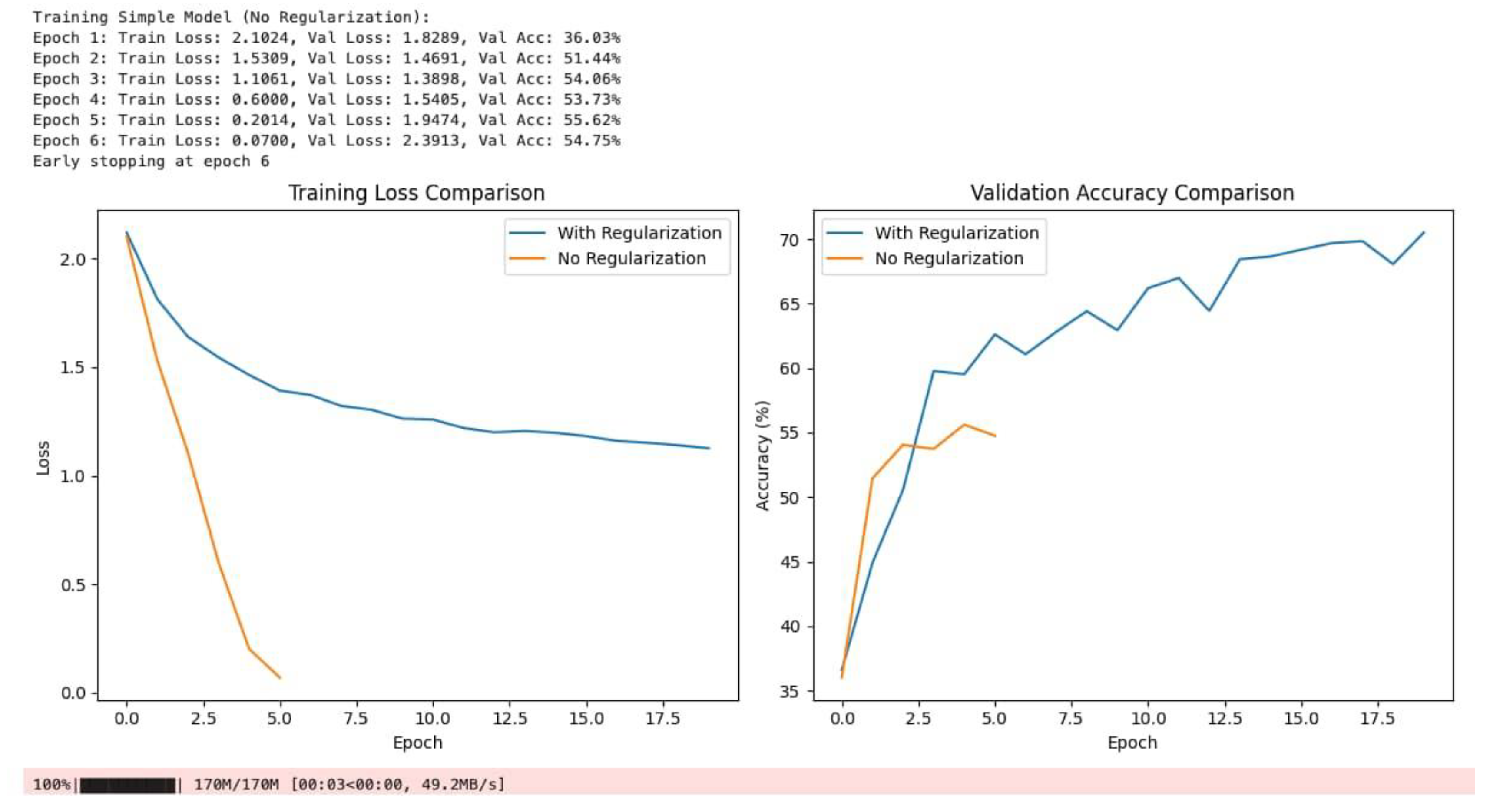

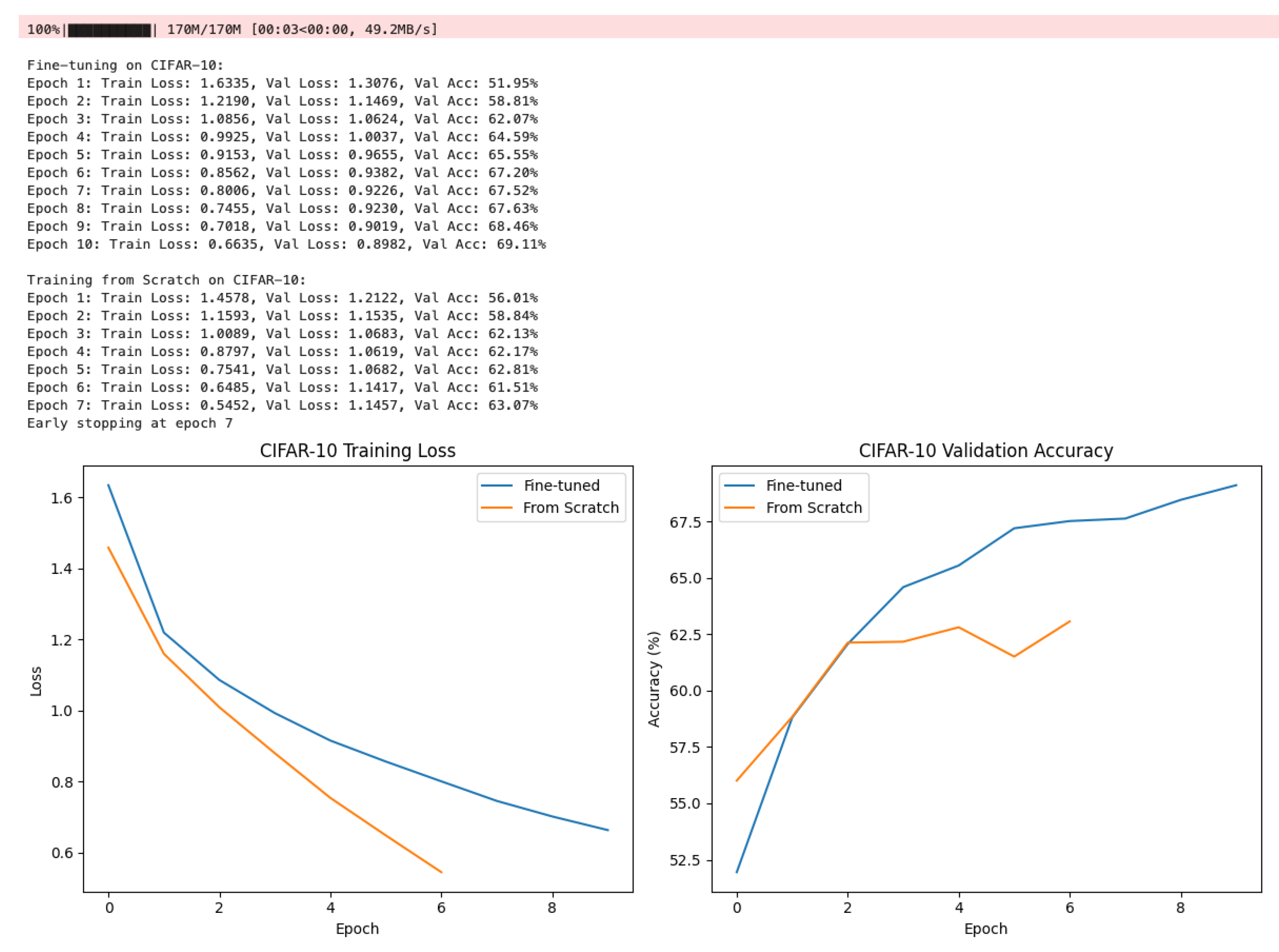

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusion

References

- K. O’Shea and R. Nash, “An Introduction to Convolutional Neural Networks,” Int J Res Appl Sci Eng Technol, vol. 10, no. 12, pp. 943–947, Nov. 2015. [CrossRef]

- G. Hu et al., “When Face Recognition Meets With Deep Learning: An Evaluation of Convolutional Neural Networks for Face Recognition,” 2015.

- A. I. Khan and S. Al-Habsi, “Machine Learning in Computer Vision,” Procedia Comput Sci, vol. 167, pp. 1444–1451, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. E. T Akinsola, A. Jet, and H. J. O, “Supervised Machine Learning Algorithms: Classification and Comparison,” Article in International Journal of Computer Trends and Technology, vol. 2017; 48. [CrossRef]

- T. Dietterich, “Overfitting and Undercomputing in Machine Learning,” ACM Computmg Survevs, vol. 27, no. 3, 1995, Accessed: May 02, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://dl.acm.org/doi/pdf/10.1145/212094.

- C. Zhang, S. Bengio, M. Hardt, B. Recht, and O. Vinyals, “Understanding deep learning (still) requires rethinking generalization,” Commun ACM, vol. 64, no. 3, pp. 107–115, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. El Sawy, H. El-Bakry, and M. Loey, “CNN for Handwritten Arabic Digits Recognition Based on LeNet-5,” in Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, Springer, Cham, 2017, pp. 566–575. [CrossRef]

- F. N. Iandola, S. Han, M. W. Moskewicz, K. Ashraf, W. J. Dally, and K. Keutzer, “SqueezeNet: AlexNet-level accuracy with 50x fewer parameters and .

- S. Tammina, “Transfer learning using VGG-16 with Deep Convolutional Neural Network for Classifying Images,” International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, vol. 9, no. 10, p. 143, 2019. [CrossRef]

- C. Szegedy, S. Ioffe, V. Vanhoucke, and A. A. Alemi, “Inception-v4, Inception-ResNet and the Impact of Residual Connections on Learning,” Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, vol. 31, no. 1, pp. 4278–4284, Feb. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Y. Tian and Y. Zhang, “A comprehensive survey on regularization strategies in machine learning,” Information Fusion, vol. 80, pp. 146–166, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Bengio, A. Courville, and P. Vincent, “Representation learning: A review and new perspectives,” IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell, vol. 35, no. 8, pp. 1798–1828, 2013. [CrossRef]

- P. Ponte and R. G. Melko, “Kernel methods for interpretable machine learning of order parameters,” Phys Rev B, vol. 96, no. 20, p. 205146, Nov. 2017. [CrossRef]

- H. D. Khalaf Jabbar Rafiqul Zaman Khan, “METHODS TO AVOID OVER-FITTING AND UNDER-FITTING IN SUPERVISED MACHINE LEARNING (COMPARATIVE STUDY),” 2015.

- A. Muscoloni, J. M. Thomas, S. Ciucci, G. Bianconi, and C. V. Cannistraci, “Machine learning meets complex networks via coalescent embedding in the hyperbolic space,” Nat Commun, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 1–19, Dec. 2017. [CrossRef]

- O. Demir-Kavuk, M. Kamada, T. Akutsu, and E. W. Knapp, “Prediction using step-wise L1, L2 regularization and feature selection for small data sets with large number of features,” BMC Bioinformatics, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 1–10, Oct. 2011. [CrossRef]

- T. Hoefler, D. Alistarh, T. Ben-Nun, N. Dryden, and A. Peste, “Sparsity in Deep Learning: Pruning and growth for efficient inference and training in neural networks,” Journal of Machine Learning Research, vol. 22, no. 241, pp. 1–124, 2021, Accessed: May 02, 2025. [Online]. Available: http://jmlr.org/papers/v22/21-0366.

- P. Baldi and P. Sadowski, “The dropout learning algorithm,” Artif Intell, vol. 210, no. 1, pp. 78–122, May 2014. [CrossRef]

- J. I. Glaser, A. S. Benjamin, R. H. Chowdhury, M. G. Perich, L. E. Miller, and K. P. Kording, “Machine Learning for Neural Decoding,” eNeuro, vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 1–16, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. T. T. Nguyen and G. Armitage, “Training on multiple sub-flows to optimise the use of Machine Learning classifiers in real-world IP networks,” Proceedings - Conference on Local Computer Networks, LCN, pp. 2006. [CrossRef]

- G. Ghiasi, T.-Y. Lin, and Q. V. Le, “DropBlock: A regularization method for convolutional networks,” Adv Neural Inf Process Syst, vol. 31, 2018.

- H. Meyer, C. Reudenbach, S. Wöllauer, and T. Nauss, “Importance of spatial predictor variable selection in machine learning applications – Moving from data reproduction to spatial prediction,” Ecol Modell, vol. 411, p. 108815, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. Mikołajczyk and M. Grochowski, “Data augmentation for improving deep learning in image classification problem,” 2018 International Interdisciplinary PhD Workshop, IIPhDW 2018, pp. 117–122, Jun. 2018. [CrossRef]

- A. Vabalas, E. Gowen, E. Poliakoff, and A. J. Casson, “Machine learning algorithm validation with a limited sample size,” PLoS One, vol. 14, no. 11, p. e0224365, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- D. Rafique and L. Velasco, “Machine learning for network automation: Overview, architecture, and applications [Invited Tutorial],” Journal of Optical Communications and Networking, vol. 10, no. 10, pp. D126–D143, Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- R. Adolf, S. Rama, B. Reagen, G. Y. Wei, and D. Brooks, “Fathom: Reference workloads for modern deep learning methods,” Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Symposium on Workload Characterization, IISWC 2016, pp. 148–157, Oct. 2016. [CrossRef]

- A Sharif Razavian, H. Azizpour, J. Sullivan, and S. Carlsson, “CNN Features Off-the-Shelf: An Astounding Baseline for Recognition,” in IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) Workshops, 2014, pp. 806–813. Accessed: May 02, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.cv-foundation.org/openaccess/content_cvpr_workshops_2014/W15/html/Razavian_CNN_Features_Off-the-Shelf_2014_CVPR_paper.

- Z. Goldfeld et al., “Estimating Information Flow in Deep Neural Networks,” 36th International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML 2019, vol. 2019-June, pp. 4153–4162, Oct. 2018, Accessed: May 02, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1810.

- A. Nedic, “Distributed Gradient Methods for Convex Machine Learning Problems in Networks: Distributed Optimization,” IEEE Signal Process Mag, vol. 37, no. 3, pp. 92–101, May 2020. 20. [CrossRef]

- E. Dufourq and B. A. Bassett, “EDEN: Evolutionary deep networks for efficient machine learning,” 2017 Pattern Recognition Association of South Africa and Robotics and Mechatronics International Conference, PRASA-RobMech 2017, vol. 2018-January, pp. 110–115, Jul. 2017. [CrossRef]

- R. Moradi, R. Berangi, and B. Minaei, “A survey of regularization strategies for deep models,” Artif Intell Rev, vol. 53, no. 6, pp. 3947–3986, Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. Liu et al., “A cascaded dual-pathway residual network for lung nodule segmentation in CT images,” Physica Medica, vol. 63, pp. 112–121, Jul. 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. T. Ataei, P. M. Zadeh, and S. Ataei, “Vision-based autonomous structural damage detection using data-driven methods,” Jan. 2025, Accessed: Aug. 23, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2501.16662.

- Alireza Pirverdizade and Tohid Asadi, “Transformation of the Global Trade System and Its Impact on Energy Markets,” in In book: SYSTEMIC TRANSITIONS IN WORLD TRADE AND THEIR ENERGY MARKET REPERCUSSIONSEdition: First EditionChapter: 1Publisher: Liberty Academic Publishers, Jul. 2025. Accessed: Oct. 17, 2025. [Online]. Available: 10.5281/zenodo.16317283.

- E. Ziad, F. Ju, Z. Yang, and Y. Lu, “Pyramid Learning Based Part-to-Part Consistency Analysis in Laser Powder Bed Fusion,” in Proceedings of ASME 2024 19th International Manufacturing Science and Engineering Conference, MSEC 2024, American Society of Mechanical Engineers Digital Collection, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Bozorgpour, “Computational Fluid Dynamics in Highly Complex Geometries Using MPI-Parallel Lattice Boltzmann Methods: A Biomedical Engineering Application,” bioRxiv, p. 2025.05.25.656026, May 2025. [CrossRef]

- G. Zhai et al., “Quantifying subsidence damage risk to infrastructures in 25 most populous U.S. cities from the space,” AGUFM, vol. 2022, pp. NH34A-02, 2022, Accessed: Aug. 25, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2022AGUFMNH34A..02Z/abstract.

- M. Zarchi, • Zohreh, H. Aslani, • Kong, and F. Tee, “An interpretable information fusion approach to impute meteorological missing values toward cross-domain intelligent forecasting,” Neural Computing and Applications 2025, pp. 1–57, Aug. 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. E. Fard, T. Ghosh, and E. Sazonov, “Multi-Task NoisyViT for Enhanced Fruit and Vegetable Freshness Detection and Type Classification,” Sensors 2025, Vol. 25, Page 5955, vol. 25, no. 19, p. 5955, Sep. 2025. [CrossRef]

- C. Ruiz and A. Dashti, “Mixed Models for Product Design Selection Based on Accelerated Degradation Testing,” in Proceedings - Annual Reliability and Maintainability Symposium, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. Adadian and J. Russell, “Exploring Backcasting as a Tool to Co-create A Vision for a Circular Economy: A Case Study of the Polyurethane Foam Industry | NSF Public Access Repository,” 2024. Accessed: Oct. 18, 2025. [Online]. Available: ttps://par.nsf.gov/biblio/10539801.

- B. Kiafar, S. Daher, S. Sharmin, A. Ahmmed, L. Thiamwong, and R. L. Barmaki, “Analyzing Nursing Assistant Attitudes Towards Geriatric Caregiving Using Epistemic Network Analysis,” Communications in Computer and Information Science, vol. 2278 CCIS, pp. 187–201, 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Mehrnia and M. S. M. Elbaz, “Stochastic Entanglement Configuration for Constructive Entanglement Topologies in Quantum Machine Learning with Application to Cardiac MRI,” Jul. 2025, Accessed: Oct. 18, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2507.11401.

- E. Ziad, Z. Yang, Y. Lu, and F. Ju, “Knowledge Constrained Deep Clustering for Melt Pool Anomaly Detection in Laser Powder Bed Fusion,” in IEEE International Conference on Automation Science and Engineering, IEEE Computer Society, 2024, pp. 670–675. [CrossRef]

- Y. Mousavi, P. Akbari, R. Mousavi, I. B. Kucukdemiral, A. Fekih, and U. Cali, “QRL-AFOFA: Q-Learning Enhanced Self-Adaptive Fractional Order Firefly Algorithm for Large-Scale and Dynamic Multiobjective Optimization Problems,” Aug. 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. Abedi, O. Noakoasteen, S. D. Hemmady, C. Christodoulou, and E. Schamiloglu, “Application of Time Reversal Techniques for Identifying Shielding Effectiveness in Complex Electronic Systems,” Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), Sep. 2025, pp. 529–532. [CrossRef]

- B. Kiafar, P. U. Ravva, S. Daher, A. Ahmmed Joy, and R. Leila Barmaki, “MENA: A Multimodal Framework for Analyzing Caregiver Emotions and Competencies in AR Geriatric Simulations,” Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Multimodal Interaction, pp. 181–190, Oct. 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. SALEHI, Roozbeh Naghshineh, and َAli Ahmadian, “Determine of Proxemic Distance Changes before and During COVID-19 Pandemic with Cognitive Science Approach,” OSF, 25, Accessed: Aug. 24, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://osf.io/y4p82.

- E. Maleki et al., “AI-generated and YouTube Videos on Navigating the U.S. Healthcare Systems: Evaluation and Reflection,” International Journal of Technology in Teaching and Learning, vol. 20, no. 1, 2024. [CrossRef]

- N. Karpourazar, S. K. Mazumder, V. Jangir, K. M. Dowling, J. Leach, and L. Voss, “Parametric Analysis of First High-Gain Vertical Fe-doped Ultrafast Ga2O3 Photoconductive Semiconductor Switch,” Aug. 2025, Accessed: Aug. 25, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2508.04911.

- M. J. Torkamani, N. Mahmoudi, and K. Kiashemshaki, “LLM-Driven Adaptive 6G-Ready Wireless Body Area Networks: Survey and Framework,” Aug. 2025, Accessed: Oct. 18, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2508.08535.

- S. E. Fard et al., “Development of a Method for Compliance Detection in Wearable Sensors,” in International Conference on Electrical, Computer and Energy Technologies, ICECET 2023, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Irani and V. Metsis, “Positional Encoding in Transformer-Based Time Series Models: A Survey,” Feb. 2025, Accessed: Oct. 18, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2502.12370.

- A. Hosseini and A. M. Farid, “A Hetero-functional Graph Theory Perspective of Engineering Management of Mega-Projects,” IEEE Access, 2025. [CrossRef]

- R. Bozorgpour and P. Kim, “CFD and FSI Face-Off: Revealing Hemodynamic Differences in Cerebral Aneurysms,” May 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. S. Norouzi, M. Masjedi, H. Sholehrasa, S. Alkaee Taleghan, and A. Arastehfard, “Primer on Deep Learning Models,” pp. 3–37, Mar. 2025. [CrossRef]

- K. Kaur, E. Rajaie, ; Zaid Momani, S. Ghalambor, and M. Najafi, “Applicability of Hole-Spanning Design Equations and FEM Modeling for Carbon Steel Pipelined with Spray Applied Pipe Lining,” Pipelines 2025, pp. 690–700, Aug. 2025. [CrossRef]

- K. Yazdipaz, N. Kohli, S. Ali Golestaneh, and M. Shahbazi, “Robust and Efficient Phase Estimation in Legged Robots via Signal Imaging and Deep Neural Networks,” IEEE Access, vol. 13, pp. 49018–49029, 2025. [CrossRef]

- A. Ahmadian, S. Salehi, and R. Naghshineh, “Recognize adaptive ecologies and their applications in architectural structures,” Sharif Journal of Civil Engineering, vol. 39, no. 4, pp. 101–109, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Younesi Heravi, A. Y. Demeke, I. S. Dola, Y. Jang, I. Jeong, and C. Le, “Vehicle intrusion detection in highway work zones using inertial sensors and lightweight deep learning,” Autom Constr, vol. 176, p. 106291, Aug. 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. Goodarzi and Q. Li, “Micro Energy-Water-Hydrogen Nexus: Data-driven Real-time Optimal Operation,” Nov. 2023, Accessed: Aug. 24, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2311.12274.

- S. D. Gapud, H. H. Karahroodi, and H. J. De Queiroz, “From Insights to Action: Uniting Data and Intellectual Capital for Strategic Success,” The Amplifying Power of Intellectual Capital in the Contemporary Era [Working Title], Aug. 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. Shoja and T. Kouchesfahani, “A Recommended Approach to Violin Educational Repertoire in Iran: A Composition Analysis Based on Western Techniques,” Journal of Research in Music, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 86–105, Aug. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Hasan Pourmahmood-Aghababa, Mohammad Hossein Sattari, and Hamid Shafie-Asl, “Bounded Pseudo-Amenability and Contractibility of Certain Banach Algebras,” JSTOR, 2020, Accessed: Aug. 25, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.jstor.org/stable/27383292?seq=1.

- E. Soltanmohammadi, “INNOVATIVE STRATEGIES FOR HEALTHCARE DATA INTEGRATION: ENHANCING ETL EFFICIENCY THROUGH CONTAINERIZATION AND PARALLEL COMPUTING,” 2024.

- M. H. Sattari and H. Shafieasl, “PRODUCT OF DERIVATIONS ON TRIANGULAR BANACH ALGEBRAS,” Journal of Hyperstructures, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 28–39, 2017.

- Z. Rahmani et al., “Privacy-Preserving Collaborative Genomic Research: A Real-Life Deployment and Vision,” pp. 85–91, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- N. Jafari, S. Sheikhfarshi, F. Raisali, P. Aghaei, P. Azini, and H. Health Environments Research and Design Journal, 2025. [CrossRef]

- D. BOLHASSANI et al., “Numerical analysis with experimental verification of a multi-layer sheet-based funicular glass bridge,” in Proceedings of IASS Annual Symposia, IASS 2024 Zurich Symposium: Computational Methods - Numerical Methods for Geometry, Form-Finding and Optimization of Lightweight Structures, International Association for Shell and Spatial Structures (IASS), 2024, pp. 1–10.

- P. Omidmand, “View of Short Review: Artificial Intelligence Applications in Growth Hacking Methodology,” International Journal of Applied Data Science in Engineering and Health, 2025, Accessed: Aug. 25, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://ijadseh.com/index.php/ijadseh/article/view/36/35.

- S. Sharifi, “Novel stratified algorithms for sustainable decision-making under uncertainty: MOSDM and SSDM,” Appl Soft Comput, vol. 178, p. 113239, Jun. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Y. Fazeli, Z. Nourbakhsh, S. Yalameha, and D. Vashaee, “Anisotropic Elasticity, Spin–Orbit Coupling, and Topological Properties of ZrTe2 and NiTe2: A Comparative Study for Spintronic and Nanoscale Applications,” Nanomaterials, vol. 15, no. 2, p. 148, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- E. Ghanaee, J. I. Pérez-Díaz, D. Fernández-Muñoz, J. Nájera, and M. Chazarra, “Comparative Analysis of Battery Degradation Models for Optimal Operation of a Hybrid Power Plant in the Day-Ahead Market,” in 2025 IEEE Kiel PowerTech, IEEE, Jun. 2025, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- A. Vaysi et al., “Network-based methodology to determine obstructive sleep apnea,” Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications, vol. 673, p. 130714, Sep. 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. Yari and G. D. Acar, “Dynamics of a cylindrical beam subjected to simultaneous vortex induced vibration and base excitation,” Ocean Engineering, vol. 318, p. 120198, Feb. 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. Faghirnejad, “Performance-Based Optimization of 2D Reinforced Concrete Moment Frames through Pushover Analysis and ABC Optimization Algorithm,” Earthquake and Structures, vol. 27, no. 4, pp. 285–302, Jul. 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. Faghirnejad, D.-P. N. Kontoni, and M. R. Ghasemi, “Performance-based optimization of 2D reinforced concrete wall-frames using pushover analysis and ABC optimization algorithm,” Earthquakes and Structures, vol. 27, no. 4, p. 285, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ebrahim Maghsoudlou, Sruthi Rachamallaa, and Henry Hexmoor, “Blockchain and IoT-Enabled Earning Mechanism for Driver Safety Rewards in Cooperative Platooning Environment,” International Journal of Emerging Trends in Engineering Research, 2025, Accessed: Aug. 25, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.warse.org/IJETER/static/pdf/file/ijeter021322025.pdf.

- Amirhossein Saghezchi, Vesal Ghassemzadeh Kashani, and Faraz Ghodratizadeh, “A Comprehensive Optimization Approach on Financial Resource Allocation in Scale-Ups - ProQuest,” Journal of Business and Management Studies, 2024.

- K. Lahsaei, M. Vaghefi, C. A. Chooplou, and F. Sedighi, “Numerical simulation of flow pattern at a divergent pier in a bend with different relative curvature radii using ansys fluent,” Engineering Review : Međunarodni časopis namijenjen publiciranju originalnih istraživanja s aspekta analize konstrukcija, materijala i novih tehnologija u području strojarstva, brodogradnje, temeljnih tehničkih znanosti, elektrotehnike, računarstva i gr…, vol. 42, no. 3, pp. 63–85, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Golmohammadi et al., “Comprehensive assessment of adverse event profiles associated with bispecific antibodies in multiple myeloma,” Blood Cancer J, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 1–11, Dec. 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. Mashhadi, S. Mojtahedi, and M. Kanaanitorshizi, “Return Anomalies Under Constraint: Evidence from an Emerging Market,” Journal of Economics, Finance and Accounting Studies, vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 166–184, Aug. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Matin Ghasempour Anaraki, Masoud Rabbani, Moein Ghaffari, and Ali Moradi Afrapoli, “Simulation-Based Optimization of Truck Allocation in Material Handling Systems,” MOL Report Ten, 2022, Accessed: Aug. 25, 2025. [Online]. Available: www.ualberta.ca/mol.

- S. Sohrabi, Y. Darestani, and W. Pringle, “Accurate and efficient resilience assessment of coastal electric power distribution networks,” in 14th International Conference on Structural Safety and Reliability - ICOSSAR’25, Los Angeles California, USA: Scipedia, S.L., Jun. 2025. [CrossRef]

- A. Morteza and R. A. Chou, “Distributed Matrix Multiplication: Download Rate, Randomness and Privacy Trade-Offs,” in 2024 60th Annual Allerton Conference on Communication, Control, and Computing, Allerton 2024, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Minaei, Y. S. Salar, I. Zwierzchowska, F. Azinmoghaddam, and A. Hof, “Exploring inequality in green space accessibility for women - Evidence from Mashhad, Iran,” Sustain Cities Soc, vol. 126, p. 106406, May 2025. [CrossRef]

- F. Nasihati and Z. M. Kassas, “Observability Analysis of Receiver Localization with DOA Measurements from a Single LEO Satellite,” IEEE Trans Aerosp Electron Syst, 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. A. Balasubramanian, “Signal-First Architectures: Rethinking Front-End Reactivity,” Jun. 2025, Accessed: Oct. 30, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2506.13815.

- M. Piri, J. E. Ash, and M. J. Amani, “Does the Conspicuity of Automated Vehicles with Visible Sensor Stacks Influence the Car-Following Behavior of Human Drivers? Transp Res Rec, 2025. [CrossRef]

- H. Shafie-Asl, “A Note on Ramified Coverings of Riemann Surfaces,” International Mathematical Forum, vol. 15, no. 8, pp. 377–381, 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Dolhopolov, T. Honcharenko, and D. Chernyshev, “NeuroPhysNet: A Novel Hybrid Neural Network Model for Enhanced Prediction and Control of Cyber-Physical Systems,” in Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH, 2025, pp. 351–365. [CrossRef]

- P. Nikzat and M. Noorymotlagh, “Artificial Intelligence in Business: Driving Innovation and Competitive Advantage,” International journal of industrial engineering and operational research, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 50–62, Oct. 2025. [CrossRef]

- A. Hosseini and A. M. Farid, “Extending Resource Constrained Project Scheduling to Mega-Projects with Model-Based Systems Engineering & Hetero-functional Graph Theory,” Oct. 2025, Accessed: Oct. 30, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2510.19035.

- J. Jeong, J. H. Lee, H. H. Karahroodi, and I. Jeong, “Uncivil customers and work-family spillover: examining the buffering role of ethical leadership,” BMC Psychol, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 1–13, Dec. 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. Faghirnejad, D. P. N. Kontoni, C. V. Camp, M. R. Ghasemi, and M. Mohammadi Khoramabadi, “Seismic performance-based design optimization of 2D steel chevron-braced frames using ACO algorithm and nonlinear pushover analysis,” Structural and Multidisciplinary Optimization, vol. 68, no. 1, pp. 1–27, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. Zehsaz and F. Soleimani, “Enhancing seismic risk assessment: a sparse multi-task learning approach for high-dimensional structural systems,” in 14th International Conference on Structural Safety and Reliability - ICOSSAR’25, Scipedia, S.L., Jun. 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. Zehsaz, S. Kameshwar, and F. Soleimani, “The influence of aging on seismic bridge vulnerability: A machine learning and probabilistic model integration,” Structures, vol. 82, p. 110472, Dec. 2025. [CrossRef]

- A. Ebrahimi, “DNA-Based Deep Learning and Association Studies for Drug Response Prediction in Leiomyosarcoma,” medRxiv, p. 2025.10.22.25338578, Oct. 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. H. Shahverdian et al., “Towards Zero-Energy Buildings: A Comparative Techno-Economic and Environmental Analysis of Rooftop PV and BIPV Systems,” Buildings 2025, Vol. 15, Page 999, vol. 15, no. 7, p. 999, Mar. 2025. [CrossRef]

- A. Yeganeh Rikhtehgar and B. Teymür, “Effect of Magnesium Chloride Solution as an Antifreeze Agent in Clay Stabilization during Freeze-Thaw Cycles,” Applied Sciences 2024, Vol. 14, Page 4140, vol. 14, no. 10, p. 4140, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Ataei, S. T. Ataei, and A. M. Saghiri, “Applications of Deep Learning to Cryptocurrency Trading: A Systematic Analysis,” Authorea Preprints, Jun. 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. Yadollahi, A. Heydarnoori, and I. Khazrak, “Enhancing Commit Message Generation in Software Repositories: A RAG-Based Approach,” in 2025 IEEE/ACIS 23rd International Conference on Software Engineering Research, Management and Applications, SERA 2025 - Proceedings, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2025, pp. 573–578. [CrossRef]

- S. Salehi, A. Talaei, and R. Naghshineh, “Proxemic Behaviors in Same-Sex and Opposite-Sex Social Interactions: Applications in Urban and Interior Space Design,” Apr. 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. Filvantorkaman, M. Piri, M. F. Torkaman, A. Zabihi, and H. Moradi, “Fusion-Based Brain Tumor Classification Using Deep Learning and Explainable AI, and Rule-Based Reasoning,” Aug. 2025, Accessed: Aug. 23, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2508.06891.

- D. Charkhian, “Exploring the potential of AI for improving inclusivity in university portals,” Drexel University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States, 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. Farhang and H. Hojat Jalali, “Performance assessment of corroded buried pipelines under strike-slip faulting using stochastic wall loss modeling,” Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering, vol. 199, p. 109697, Dec. 2025. [CrossRef]

- B. Kiafar, P. U. Ravva, A. A. Joy, S. Daher, and R. L. Barmaki, “MENA: Multimodal Epistemic Network Analysis for Visualizing Competencies and Emotions,” IEEE Trans Vis Comput Graph, Apr. 2025, Accessed: Aug. 25, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2504.02794.

- S. Sharmin et al., “Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS) Analysis of Interaction Techniques in Touchscreen-Based Educational Gaming,” Jul. 2025. [CrossRef]

- B. Kiafar, “Enhancing Nursing Assistant Attitudes Towards Geriatric Caregiving through Transmodal Ordered Network Analysis,” in Sixth International Conference on Quantitative Ethnography: Conference Proceedings Supplement, 2024. Accessed: Aug. 25, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://par.nsf.gov/biblio/10555543.

- J. Ling, R. Jones, and J. Templeton, “Machine learning strategies for systems with invariance properties,” J Comput Phys, vol. 318, pp. 22–35, Aug. 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. Shin, M. Kim, and D. S. Kwon, “Baseline CNN structure analysis for facial expression recognition,” 25th IEEE International Symposium on Robot and Human Interactive Communication, RO-MAN 2016, pp. 724–729, Nov. 2016. [CrossRef]

- G. Naidu, T. Zuva, and E. M. Sibanda, “A Review of Evaluation Metrics in Machine Learning Algorithms,” Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, vol. 724 LNNS, pp. 15–25, 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Li et al., “Machine Learning for Patient-Specific Quality Assurance of VMAT: Prediction and Classification Accuracy,” International Journal of Radiation Oncology*Biology*Physics, vol. 105, no. 4, pp. 893–902, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- P. Wang, E. Fan, and P. Wang, “Comparative analysis of image classification algorithms based on traditional machine learning and deep learning,” Pattern Recognit Lett, vol. 141, pp. 61–67, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Victor Ikechukwu, S. Murali, R. Deepu, and R. C. Shivamurthy, “ResNet-50 vs VGG-19 vs training from scratch: A comparative analysis of the segmentation and classification of Pneumonia from chest X-ray images,” Global Transitions Proceedings, vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 375–381, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Iqbal, A. N. Qureshi, J. Li, and T. Mahmood, “On the Analyses of Medical Images Using Traditional Machine Learning Techniques and Convolutional Neural Networks,” Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering 2023 30:5, vol. 30, no. 5, pp. 3173–3233, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Naushad, T. Kaur, and E. Ghaderpour, “Deep Transfer Learning for Land Use and Land Cover Classification: A Comparative Study,” Sensors 2021, Vol. 21, Page 8083, vol. 21, no. 23, p. 8083, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. U. R. Khan, M. Zhao, S. Asif, and X. Chen, “Hybrid-NET: A fusion of DenseNet169 and advanced machine learning classifiers for enhanced brain tumor diagnosis,” Int J Imaging Syst Technol, vol. 34, no. 1, p. e22975, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. Roy, H. Banville, I. Albuquerque, A. Gramfort, T. H. Falk, and J. Faubert, “Deep learning-based electroencephalography analysis: a systematic review,” J Neural Eng, vol. 16, no. 5, p. 051001, Aug. 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. Mao, M. Mohri, and Y. Zhong, Cross-Entropy Loss Functions: Theoretical Analysis and Applications. PMLR, 2023. Accessed: May 09, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://proceedings.mlr.press/v202/mao23b.html.

- Y. Bengio, I. Goodfellow, and A. Courville, Deep Learning. 2015.

- J. D. Kelleher, Deep Learning. MIT press, 2019.

- S. Theodoridis and K. Konstantinos, Pattern Recognition. Elsevier, 2006. Accessed: May 09, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=gAGRCmp8Sp8C&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=pattern+recognition&ots=pKR5YNPeTK&sig=IbVTnxSrod7DdcvF9XVWvknCSZc#v=onepage&q=pattern%20recognition&f=false.

- J. Howard, “Imagenette: A smaller subset of 10 easily classified classes from Imagenet [Data set]. GitHub.” Accessed: May 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/fastai/imagenette#imagenette-1.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).