Submitted:

06 November 2025

Posted:

07 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

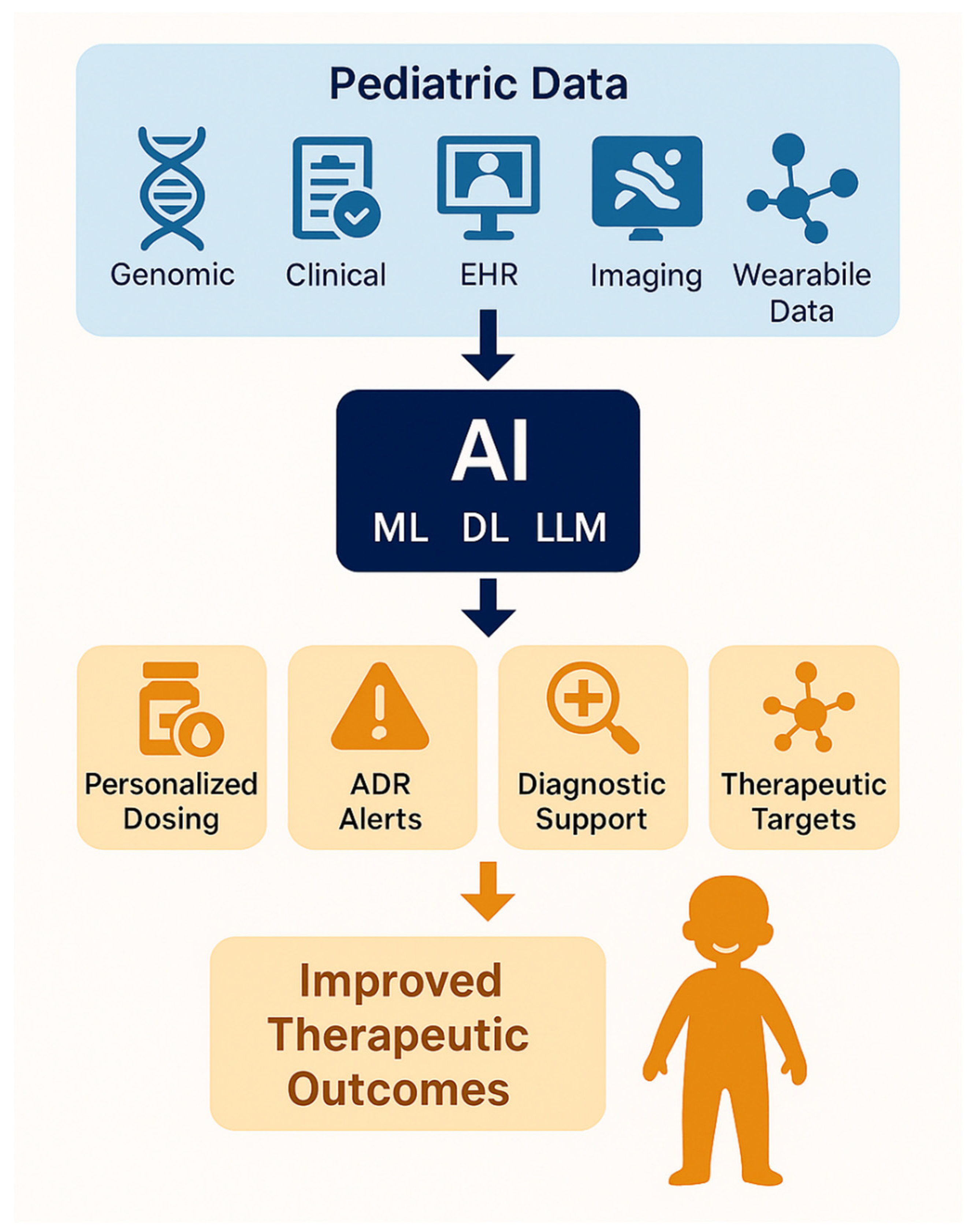

1. Introduction

2. Artificial Intelligence and Precision Medicine: Theoretical Foundations and Clinical Convergence

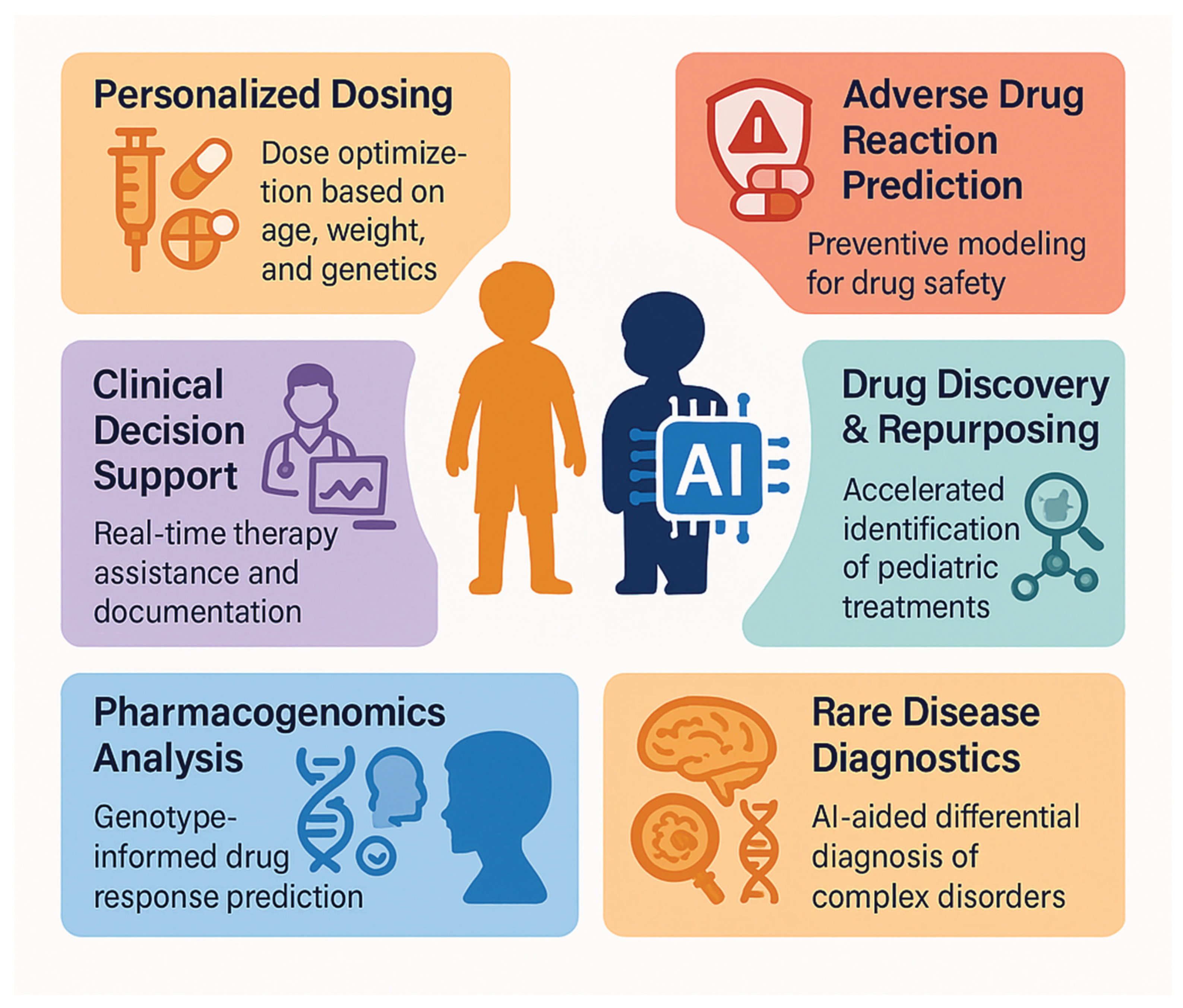

3. Current Applications in Pediatric Precision Pharmacotherapy

3.1. Pharmacogenomics and Dosage Optimization

3.2. Adverse Drug Reaction Prediction

3.3. Drug Discovery and Repositioning

3.4. Clinical Decision Support Systems

4. Disease-Specific Applications

4.1. Pediatric Oncology

4.2. Pediatric Infectious Diseases

4.3. Pediatric Neurological Diseases

4.4. Pediatric Rare Genetic Diseases

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Definition |

| ACCEPT-AI | Age, Communication, Consent and assent, Equity, Protection of data, Technology |

| ADE | Adverse Drug Event |

| ADRs | Adverse Drug Reactions |

| ALL | Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia |

| AML | Acute Myeloid Leukemia |

| APEX GO | APEX Generative Optimization |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| AUPR | Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve |

| CDSS | Clinical Decision Support System |

| CPIC | Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| DTI | Diffusion Tensor Imaging |

| EHR | Electronic Health Record |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| GBDT | Gradient Boosting Decision Tree |

| GBRT | Gradient Boosted Regression Trees |

| HD-MTX | High-Dose Methotrexate |

| LIU | Labeled Independent Users dataset |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| MGPS | Multi-item Gamma Poisson Shrinker |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| PCC | Pearson Correlation Coefficient |

| PGx | Pharmacogenomics |

| RAG | Retrieval-Augmented Generation |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| rs-fMRI | Resting-State Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| SEPD | Sepsis on ED to PICU Disposition |

| SHAP | SHapley Additive exPlanations |

| SIRS | Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome |

| SMOTE | Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique |

| UTI | Urinary Tract Infection |

| XGB | Extreme Gradient Boosting |

| XGBoost | Extreme Gradient Boosting |

References

- World Health Organization. (2023). Artificial intelligence for health. https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/fact-sheets/item/artificial-intelligence-for-health (Accessed 22/06/25).

- Kearns, G. L., Abdel-Rahman, S. M., Alander, S. W., Blowey, D. L., Leeder, J. S., & Kauffman, R. E. (2003). Developmental Pharmacology—Drug Disposition, Action, and Therapy in Infants and Children. New England Journal of Medicine, 349(12), 1157–1167. [CrossRef]

- Precision for Medicine. Precision Medicine in Pediatrics: Biomarkers and Assay Development. Available at: https://www.precisionformedicine.com/blog/pediatric-studies-precision-medicine-approach (Accessed 22/06/25).

- Matellio. AI in Pediatric Healthcare: How Custom AI Solutions Improve Child-Centric Medical Services. Available at: https://www.matellio.com/blog/ai-in-pediatric-healthcare-services/ (Accessed 22/06/25).

- Tekkeşin Aİ. Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare: Past, Present and Future. Anatol J Cardiol. 2019 Oct;22(Suppl 2):8-9. [CrossRef]

- Johnson KB, Wei WQ, Weeraratne D, Frisse ME, Misulis K, Rhee K, Zhao J, Snowdon JL. Precision Medicine, AI, and the Future of Personalized Health Care. Clin Transl Sci. 2021 Jan;14(1):86-93. [CrossRef]

- Sartori F, Codicè F, Caranzano I, Rollo C, Birolo G, Fariselli P, Pancotti C. A Comprehensive Review of Deep Learning Applications with Multi-Omics Data in Cancer Research. Genes. 2025; 16(6):648. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Chonghui & Chen, Jingfeng. (2023). Big Data Analytics in Healthcare. [CrossRef]

- Schork NJ. Artificial Intelligence and Personalized Medicine. Cancer Treat Res. 2019;178:265-283. [CrossRef]

- Alsaedi S, Ogasawara M, Alarawi M, Gao X, Gojobori T. AI-powered precision medicine: utilizing genetic risk factor optimization to revolutionize healthcare. NAR Genom Bioinform. 2025 May 5;7(2):lqaf038. [CrossRef]

- Lorkowski J, Kolaszyńska O, Pokorski M. Artificial Intelligence and Precision Medicine: A Perspective. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2022;1375:1-11. [CrossRef]

- Tremmel R, Honore A, Park Y, Zhou Y, Xiao M, Lauschke VM. Machine learning models for pharmacogenomic variant effect predictions - recent developments and future frontiers. Pharmacogenomics. 2025 May 22:1-12. [CrossRef]

- Huang Q, Lin X, Wang Y, Chen X, Zheng W, Zhong X, Shang D, Huang M, Gao X, Deng H, Li J, Zeng F, Mo X. Tacrolimus pharmacokinetics in pediatric nephrotic syndrome: A combination of population pharmacokinetic modelling and machine learning approaches to improve individual prediction. Front Pharmacol. 2022 Nov 15;13:942129. [CrossRef]

- Arab A, Kashani B, Cordova-Delgado M, Scott EN, Alemi K, Trueman J, Groeneweg G, Chang WC, Loucks CM, Ross CJD, Carleton BC, Ester M. Machine learning model identifies genetic predictors of cisplatin-induced ototoxicity in CERS6 and TLR4. Comput Biol Med. 2024 Dec;183:109324. [CrossRef]

- Han LY, Chen X, Liu TS, Zhang ZL, Chen F, Zhan DC, Yu Y, Yu G. Applying exposure-response analysis to enhance Mycophenolate Mofetil dosing precision in pediatric patients with immune-mediated renal diseases by machine learning models. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2025 Aug 1;211:107146. [CrossRef]

- Zheng P, Pan T, Gao Y, Chen J, Li L, Chen Y, Fang D, Li X, Gao F, Li Y. Predicting the exposure of mycophenolic acid in children with autoimmune diseases using a limited sampling strategy: A retrospective study. Clin Transl Sci. 2025 Jan;18(1):e70092. [CrossRef]

- Hansson P, Blacker C, Uvdal H, Wadelius M, Green H, Ljungman G. Pharmacogenomics in pediatric oncology patients with solid tumors related to chemotherapy-induced toxicity: A systematic review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2025 Jul;211:104720. [CrossRef]

- Murugan M, Yuan B, Venner E, Ballantyne CM, Robinson KM, Coons JC, Wang L, Empey PE, Gibbs RA. Empowering personalized pharmacogenomics with generative AI solutions. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2024 May 20;31(6):1356-1366. [CrossRef]

- Ou Q, Jiang X, Guo Z, Jiang J, Gan Z, Han F, Cai Y. A Fusion Deep Learning Model for Predicting Adverse Drug Reactions Based on Multiple Drug Characteristics. Life (Basel). 2025 Mar 10;15(3):436. [CrossRef]

- Dsouza VS, Leyens L, Kurian JR, Brand A, Brand H. Artificial intelligence (AI) in pharmacovigilance: A systematic review on predicting adverse drug reactions (ADR) in hospitalized patients. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2025 Jun;21(6):453-462. [CrossRef]

- Simpson MD, Qasim HS. Clinical and Operational Applications of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Pharmacy: A Narrative Review of Real-World Applications. Pharmacy. 2025; 13(2):41. [CrossRef]

- Hu Q, Chen Y, Zou D, He Z and Xu T (2024) Predicting adverse drug event using machine learning based on electronic health records: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Pharmacol. 15:1497397. [CrossRef]

- Ietswaart R, Arat S, Chen AX, Farahmand S, Kim B, DuMouchel W, Armstrong D, Fekete A, Sutherland JJ, Urban L. Machine learning guided association of adverse drug reactions with in vitro target-based pharmacology. EBioMedicine. 2020 Jul;57:102837. [CrossRef]

- Yu Z, Ji H, Xiao J, Wei P, Song L, Tang T, Hao X, Zhang J, Qi Q, Zhou Y, Gao F, Jia Y. Predicting Adverse Drug Events in Chinese Pediatric Inpatients With the Associated Risk Factors: A Machine Learning Study. Front Pharmacol. 2021 Apr 27;12:659099. [CrossRef]

- Yalçın N, Kaşıkcı M, Çelik HT, Allegaert K, Demirkan K, Yiğit Ş, Yurdakök M. An Artificial Intelligence Approach to Support Detection of Neonatal Adverse Drug Reactions Based on Severity and Probability Scores: A New Risk Score as Web-Tool. Children (Basel). 2022 Nov 26;9(12):1826. [CrossRef]

- Rekha BH, Hisham SA, Wahab IA, Ali NM, Goh KW, Ming LC. Digital monitoring of medication safety in children: an investigation of ADR signalling techniques in Malaysia. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2024 Dec 18;24(1):395. [CrossRef]

- Zeng Y, Lu H, Li S, Shi QZ, Liu L, Gong YQ, Yan P. Risk Prediction of Liver Injury in Pediatric Tuberculosis Treatment: Development of an Automated Machine Learning Model. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2025 Jan 13;19:239-250. [CrossRef]

- Mishra HP, Gupta R. Leveraging Generative AI for Drug Safety and Pharmacovigilance. Curr Rev Clin Exp Pharmacol. 2025;20(2):89-97. [CrossRef]

- Niazi SK, Mariam Z. Artificial intelligence in drug development: reshaping the therapeutic landscape. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2025 Feb 24;16:20420986251321704. [CrossRef]

- Ocana A, Pandiella A, Privat C, Bravo I, Luengo-Oroz M, Amir E, Gyorffy B. Integrating artificial intelligence in drug discovery and early drug development: a transformative approach. Biomark Res. 2025 Mar 14;13(1):45. [CrossRef]

- Wan Z, Sun X, Li Y, Chu T, Hao X, Cao Y, Zhang P. Applications of Artificial Intelligence in Drug Repurposing. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2025 Apr;12(14):e2411325. [CrossRef]

- Young CM, Phares SE, Kennedy A, Sullivan J, McGowan B, Trusheim MR. Pediatric-onset rare disease therapy pipeline yields hope for some and gaps for many: 10-year projection of approvals, treated patients, and list price revenues. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2025 May;31(5):491-498. [CrossRef]

- Choudhury A, Asan O. Role of Artificial Intelligence in Patient Safety Outcomes: Systematic Literature Review. JMIR Med Inform. 2020 Jul 24;8(7):e18599. [CrossRef]

- Abdalwahab Abdallah ABA, Hafez Sadaka SI, Ali EI, Mustafa Bilal SA, Abdelrahman MO, Fakiali Mohammed FB, Nimir Ahmed SD, Abdelrahim Saeed NE. The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Pediatric Intensive Care: A Systematic Review. Cureus. 2025 Mar 6;17(3):e80142. [CrossRef]

- Bannett, Yair & Gunturkun, Fatma & Pillai, Malvika & Herrmann, Jessica & Luo, Ingrid & Huffman, Lynne & Feldman, Heidi. (2024). Applying Large Language Models to Assess Quality of Care: Monitoring ADHD Medication Side Effects. Pediatrics. 155. [CrossRef]

- Haddad T, Helgeson JM, Pomerleau KE, Preininger AM, Roebuck MC, Dankwa-Mullan I, Jackson GP, Goetz MP. Accuracy of an Artificial Intelligence System for Cancer Clinical Trial Eligibility Screening: Retrospective Pilot Study. JMIR Med Inform. 2021 Mar 26;9(3):e27767. [CrossRef]

- Parsi A, Glavin M, Jones E, Byrne D. Prediction of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation using new heart rate variability features. Comput Biol Med. 2021 Jun;133:104367. [CrossRef]

- Bozyel S, Şimşek E, Koçyiğit Burunkaya D, Güler A, Korkmaz Y, Şeker M, Ertürk M, Keser N. Artificial Intelligence-Based Clinical Decision Support Systems in Cardiovascular Diseases. Anatol J Cardiol. 2024 Jan 7;28(2):74–86. [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Cabello CA, Borna S, Pressman S, Haider SA, Haider CR, Forte AJ. Artificial-Intelligence-Based Clinical Decision Support Systems in Primary Care: A Scoping Review of Current Clinical Implementations. Eur J Investig Health Psychol Educ. 2024 Mar 13;14(3):685-698. [CrossRef]

- Elhaddad M, Hamam S. AI-Driven Clinical Decision Support Systems: An Ongoing Pursuit of Potential. Cureus. 2024 Apr 6;16(4):e57728. [CrossRef]

- Sarvepalli S, Vadarevu S. Role of artificial intelligence in cancer drug discovery and development. Cancer Lett. 2025 Sep 1;627:217821. [CrossRef]

- Bongurala AR, Save D, Virmani A. Progressive role of artificial intelligence in treatment decision-making in the field of medical oncology. Front Med (Lausanne). 2025 Feb 13;12:1533910. [CrossRef]

- Rossner, T., Li, Z., Balke, J., Salehfard, N., Seifert, T., & Tang, M. (2025). Integrating single-cell foundation models with graph neural networks for drug response prediction (arXiv:2504.14361). arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y., Su, X., Ullanat, V., Liang, I., Clegg, L., Olabode, D., Ho, N., John, B., Gibbs, M., & Zitnik, M. (2025). Multimodal AI predicts clinical outcomes of drug combinations from preclinical data (arXiv:2503.02781). arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Predicting Relapse at the Time of Diagnosis in Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. NIH Reporter. Available at: https://reporter.nih.gov/project-details/11047678 (Accessed 22/06/25).

- Ilyas M, Ramzan M, Deriche M, Mahmood K, Naz A. An efficient leukemia prediction method using machine learning and deep learning with selected features. PLoS One. 2025 May 16;20(5):e0320669. [CrossRef]

- Zhan M, Chen Z, Ding C, Qu Q, Wang G, Liu S, Wen F. Risk prediction for delayed clearance of high-dose methotrexate in pediatric hematological malignancies by machine learning. Int J Hematol. 2021 Oct;114(4):483-493. [CrossRef]

- Zhan M, Chen ZB, Ding CC, Qu Q, Wang GQ, Liu S, Wen FQ. Machine learning to predict high-dose methotrexate-related neutropenia and fever in children with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2021 Oct;62(10):2502-2513. [CrossRef]

- Chappell TL, Pflaster EG, Namata R, Bell J, Miller LH, Pomputius WF, Boutilier JJ, Messinger YH. Bloodstream Infections in Childhood Acute Myeloid Leukemia and Machine Learning Models: A Single-institutional Analysis. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2025 Jan 1;47(1):e26-e33. [CrossRef]

- Li M, Wang Q, Lu P, Zhang D, Hua Y, Liu F, Liu X, Lin T, Wei G, He D. Development of a Machine Learning-Based Prediction Model for Chemotherapy-Induced Myelosuppression in Children with Wilms' Tumor. Cancers (Basel). 2023 Feb 8;15(4):1078. [CrossRef]

- AlGain S, Marra AR, Kobayashi T, Marra PS, Celeghini PD, Hsieh MK, Shatari MA, Althagafi S, Alayed M, Ranavaya JI, Boodhoo NA, Meade NO, Fu D, Sampson MM, Rodriguez-Nava G, Zimmet AN, Ha D, Alsuhaibani M, Huddleston BS, Salinas JL. Can we rely on artificial intelligence to guide antimicrobial therapy? A systematic literature review. Antimicrob Steward Healthc Epidemiol. 2025 Mar 31;5(1):e90. [CrossRef]

- Cao K, Braykov N, McCarter A, Kandaswamy S, Orenstein EW, Ray E, Carter R, Gleeson MB, Iyer S, Muthu N, Mai MV. Development and Validation of an Artificial Intelligence Predictive Model to Accelerate Antibiotic Therapy for Critical Ill Children with Sepsis in the Pediatric ED with Pediatric ICU Disposition. medRxiv [Preprint]. 2025 Mar 26:2025.03.25.25324127. [CrossRef]

- Tang BH, Yao BF, Zhang W, Zhang XF, Fu SM, Hao GX, Zhou Y, Sun DQ, Liu G, van den Anker J, Wu YE, Zheng Y, Zhao W. Optimal use of β-lactams in neonates: machine learning-based clinical decision support system. EBioMedicine. 2024 Jul;105:105221. [CrossRef]

- Weissenbacher D, Dutcher L, Boustany M, Cressman L, O'Connor K, Hamilton KW, Gerber J, Grundmeier R, Gonzalez-Hernandez G. Automated Evaluation of Antibiotic Prescribing Guideline Concordance in Pediatric Sinusitis Clinical Notes. Pac Symp Biocomput. 2025;30:138-153. [CrossRef]

- Yin M, Jiang Y, Yuan Y, Li C, Gao Q, Lu H, Li Z. Optimizing vancomycin dosing in pediatrics: a machine learning approach to predict trough concentrations in children under four years of age. Int J Clin Pharm. 2024 Oct;46(5):1134-1142. [CrossRef]

- Huang X, Yu Z, Bu S, Lin Z, Hao X, He W, Yu P, Wang Z, Gao F, Zhang J, Chen J. An Ensemble Model for Prediction of Vancomycin Trough Concentrations in Pediatric Patients. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2021 Apr 14;15:1549-1559. [CrossRef]

- Chen X, Zhang R, Tang XY. Towards real-time diagnosis for pediatric sepsis using graph neural network and ensemble methods. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2021 Jul;25(14):4693-4701. [CrossRef]

- Ramgopal S, Horvat CM, Yanamala N, Alpern ER. Machine Learning To Predict Serious Bacterial Infections in Young Febrile Infants. Pediatrics. 2020 Sep;146(3):e20194096. [CrossRef]

- Lamping F, Jack T, Rübsamen N, Sasse M, Beerbaum P, Mikolajczyk RT, Boehne M, Karch A. Development and validation of a diagnostic model for early differentiation of sepsis and non-infectious SIRS in critically ill children - a data-driven approach using machine-learning algorithms. BMC Pediatr. 2018 Mar 15;18(1):112. [CrossRef]

- Hoffer O, Cohen M, Gerstein M, Shkalim Zemer V, Richenberg Y, Nathanson S, Avner Cohen H. Machine Learning for Clinical Decision Support of Acute Streptococcal Pharyngitis: A Pilot Study. Isr Med Assoc J. 2024 May;26(5):299-303. PMID: 38736345.

- Torres MDT, Zeng Y, Wan F, Maus N, Gardner J, de la Fuente-Nunez C. A generative artificial intelligence approach for antibiotic optimization. bioRxiv [Preprint]. 2024 Nov 27:2024.11.27.625757. [CrossRef]

- Juang WC, Hsu MH, Cai ZX, Chen CM. Developing an AI-assisted clinical decision support system to enhance in-patient holistic health care. PLoS One. 2022 Oct 31;17(10):e0276501. [CrossRef]

- Ayyıldız, Hakan and Arslan Tuncer, Seda. "Is it possible to determine antibiotic resistance of E. coli by analyzing laboratory data with machine learning?" Turkish Journal of Biochemistry, vol. 46, no. 6, 2021, pp. 623-630. [CrossRef]

- Pascual-Sanchez, Lidia & Jiménez, Inma & Martínez-Agüero, Sergio & Álvarez, Joaquín & Soguero Ruiz, Cristina. (2021). Predicting Multidrug Resistance Using Temporal Clinical Data and Machine Learning Methods. 2826-2833. [CrossRef]

- de la Lastra JMP, Wardell SJT, Pal T, de la Fuente-Nunez C, Pletzer D. From Data to Decisions: Leveraging Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Combating Antimicrobial Resistance - a Comprehensive Review. J Med Syst. 2024 Aug 1;48(1):71. [CrossRef]

- de Vries S, Ten Doesschate T, Totté JEE, Heutz JW, Loeffen YGT, Oosterheert JJ, Thierens D, Boel E. A semi-supervised decision support system to facilitate antibiotic stewardship for urinary tract infections. Comput Biol Med. 2022 Jul;146:105621. [CrossRef]

- Mourid MR, Irfan H, Oduoye MO. Artificial Intelligence in Pediatric Epilepsy Detection: Balancing Effectiveness With Ethical Considerations for Welfare. Health Sci Rep. 2025 Jan 22;8(1):e70372. [CrossRef]

- Zou Z, Chen B, Xiao D, Tang F, Li X. Accuracy of Machine Learning in Detecting Pediatric Epileptic Seizures: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2024 Dec 11;26:e55986. [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, E., Naik, D., & Kannan, A. (2025). Rare disease differential diagnosis with large language models at scale: From abdominal actinomycosis to Wilson's disease. arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Barry JS, Beam K, McAdams RM. Artificial intelligence in pediatric medicine: a call for rigorous reporting standards. J Perinatol. 2025 Apr 2. [CrossRef]

- Schouten JS, Kalden MACM, van Twist E, Reiss IKM, Gommers DAMPJ, van Genderen ME, Taal HR. From bytes to bedside: a systematic review on the use and readiness of artificial intelligence in the neonatal and pediatric intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med. 2024 Nov;50(11):1767-1777. [CrossRef]

- Grand View Research. AI In Healthcare Market Size, Share | Industry Report, 2030. Available at: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/artificial-intelligence-ai-healthcare-market (Accessed 24/06/25).

- Aalpha. The Cost of Implementing AI in Healthcare in 2025. Available at: https://www.aalpha.net/blog/cost-of-implementing-ai-in-healthcare/ (Accessed 24/06/25).

- Axis Intelligence. Healthcare AI Implementation: $2.4M ROI Blueprint for Medical Organizations in 2025. Available at: https://axis-intelligence.com/healthcare-ai-implementation-ai-health-2025/ (Accessed 24/06/25).

- The AI Journal. The Good, the Bad: Behind the Scenes Economic Impact of AI in Healthcare. Available at: https://aijourn.com/economicimpacthealthcare/ (Accessed 24/06/25).

- Muralidharan V, Daneshjou R, Burgart A, Rose S. Recommendations for the use of pediatric data in artificial intelligence and machine learning ACCEPT-AI. NPJ Digit Med. 2023;6:166. [CrossRef]

- Mondillo, G., Colosimo, S., Perrotta, A., Frattolillo, V., & Masino, M. (2025). Are LLMs ready for pediatrics? A comparative evaluation of model accuracy across clinical domains. medRxiv. [CrossRef]

- Cross JL, Choma MA, Onofrey JA. Bias in medical AI: Implications for clinical decision-making. PLOS Digit Health. 2024 Nov 7;3(11):e0000651. [CrossRef]

- Mondillo, G., Perrotta, A., Colosimo, S., Frattolillo, V., Masino, M., & Mantovani, M. (2025). Artificial intelligence in pediatrics: An opportunity to lead, not to follow. The Journal of Pediatrics, 114641. [CrossRef]

- Ganatra HA. Machine Learning in Pediatric Healthcare: Current Trends, Challenges, and Future Directions. J Clin Med. 2025 Jan 26;14(3):807. [CrossRef]

- Faiyazuddin M, Rahman SJQ, Mehta R, Khatib MN, Gaidhane S, Zahiruddin QS, Gaidhane A. The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Healthcare: A Comprehensive Review of Advancements in Diagnostics, Treatment, and Operational Efficiency. Health Sci Rep. 2025 Jan 5;8(1):e70312. [CrossRef]

- Kandaswamy S, Knake LA, Dziorny AC, Hernandez SM, McCoy AB, Hess LM, Orenstein E, White MS, Kirkendall ES, Molloy MJ, Hagedorn PA, Muthu N, Murugan A, Beus JM, Mai M, Luo B, Chaparro JD. Pediatric Predictive Artificial Intelligence Implemented in Clinical Practice from 2010 to 2021: A Systematic Review. Appl Clin Inform. 2025 May;16(3):477-487. [CrossRef]

- Bhargava H, Salomon C, Suresh S, Chang A, Kilian R, Stijn DV, Oriol A, Low D, Knebel A, Taraman S. Promises, Pitfalls, and Clinical Applications of Artificial Intelligence in Pediatrics. J Med Internet Res. 2024 Feb 29;26:e49022. [CrossRef]

- Kandaswamy S, Subbaswamy A, Saria S. Artificial intelligence-based clinical decision support in pediatrics. Pediatr Res. 2022 Sep;92(3):656-664. [CrossRef]

- Shortliffe EH, Sepúlveda MJ. Clinical decision support in the era of artificial intelligence. JAMA. 2018;320:2199–2200. [CrossRef]

- Balla Y, Tirunagari S, Windridge D. Pediatrics in Artificial Intelligence Era: A Systematic Review on Challenges, Opportunities, and Explainability. Indian Pediatr. 2023 Jul 15;60(7):561-569.

- Elzagallaai A, Barker C, Lewis T, Cohn R, Rieder M. Advancing Precision Medicine in Paediatrics: Past, present and future. Camb Prism Precis Med. 2023 Jan 10;1:e11. [CrossRef]

- Shahin MH, Desai P, Terranova N, Guan Y, Helikar T, Lobentanzer S, Liu Q, Lu J, Madhavan S, Mo G, Musuamba FT, Podichetty JT, Shen J, Xie L, Wiens M, Musante CJ. AI-Driven Applications in Clinical Pharmacology and Translational Science: Insights From the ASCPT 2024 AI Preconference. Clin Transl Sci. 2025 Apr;18(4):e70203. [CrossRef]

| Application Area | Pediatric Population | AI Model | Main Results | Reference |

| Pharmacogenomics and dosage | 139 children with refractory nephrotic syndrome | Lasso Regression | R² = 0.42 for tacrolimus clearance | [13] |

| Ototoxicity prevention | Pediatric oncology patients | Neural Network + Adversarial Training | Identified CERS6 and TLR4 variants | [14] |

| Mycophenolate mofetil exposure | 171 children with autoimmune renal diseases | Random Forest + SHAP | AUC0–12h > 30 mg·h/L, accurate exposure prediction | [15] |

| Predictive dosing with few blood samples | 209 children with autoimmune diseases | Wide & Deep Network | R² = 0.95 with only 3 blood samples | [16] |

| Chemotherapy-induced toxicity | Children with solid tumors | Systematic AI-PGx analysis | Gene associations with MTX/anthracycline-related toxicities | [17] |

| Study | Population | AI Model | Main Results | Reference |

| ADR in hospitalized Chinese pediatric patients | 1,746 children (median age 3.84 years) | Gradient Boosting Decision Tree (GBDT) | Precision 44% vs. 13.3% for GTT; BMI, number of doses and drugs, and hospital stay length | [24] |

| ADR in critically ill neonates | 412 critically ill neonates | ML-based Risk Score | C-index = 0.914; effective ADR prediction | [25] |

| Digital signal detection in Malaysian children | 3,152 pediatric ADR reports | MGPS | Specificity/PPV = 100%; MGPS sensitivity = 20% | [26] |

| Hepatotoxicity in pediatric tuberculosis | Children treated with rifampicin | AutoML + Gradient Boosting | AUC = 0.838 (train), 0.784 (test); Cmax and BMI most predictive | [27] |

| Meta-analysis of 59 ADR studies | Mixed-age population including pediatrics | Random Forest, SVM, XGBoost, etc. | AUC = 76.68%; Accuracy = 76.00%; Sensitivity = 62.35% | [22] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).