Submitted:

06 November 2025

Posted:

07 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Historical Context and Description of the Statuettes

2.2. Conservation Degree and Metallurgical State

2.3. From Specimen Collection to Microscopic Analyses

- Optical microscopy in both bright and dark fields (using Leica MEF4 M equipped with six magnifications: 25x, 50x, 100x, 200x, 500x, 1000x, Wetzlar; Germany).

- Energy Dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (using a PENTAFET® EDXS detector sensitive to light elements, Oxford Instruments, Abingdon-on-Thames, UK) connected to a Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) Evo40 Zeiss and INCA 300 software for BSE (backscattered electrons).

3. Results and Discussion

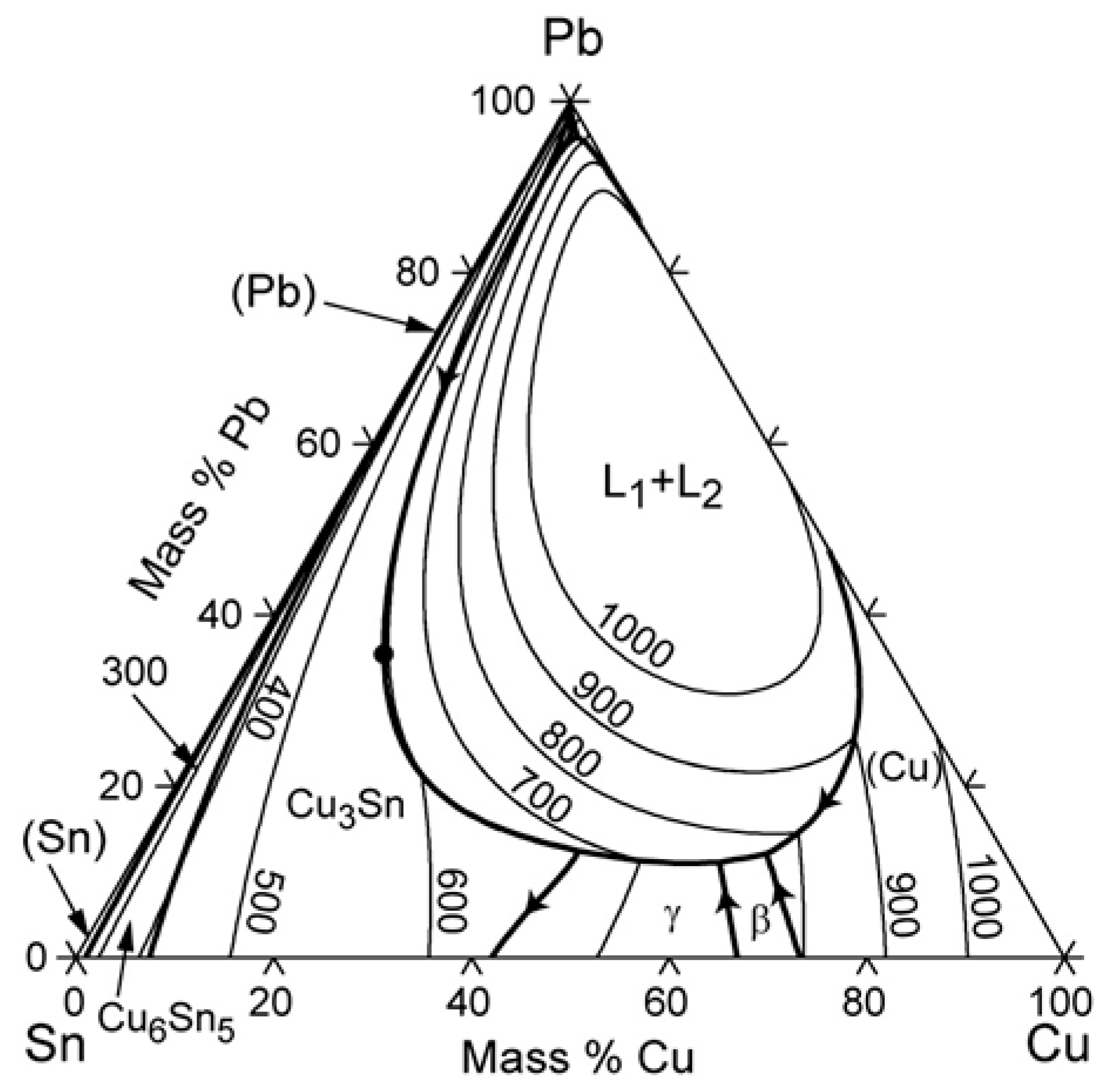

3.1. Compositional Analyses

3.1.1. p-XRF Results

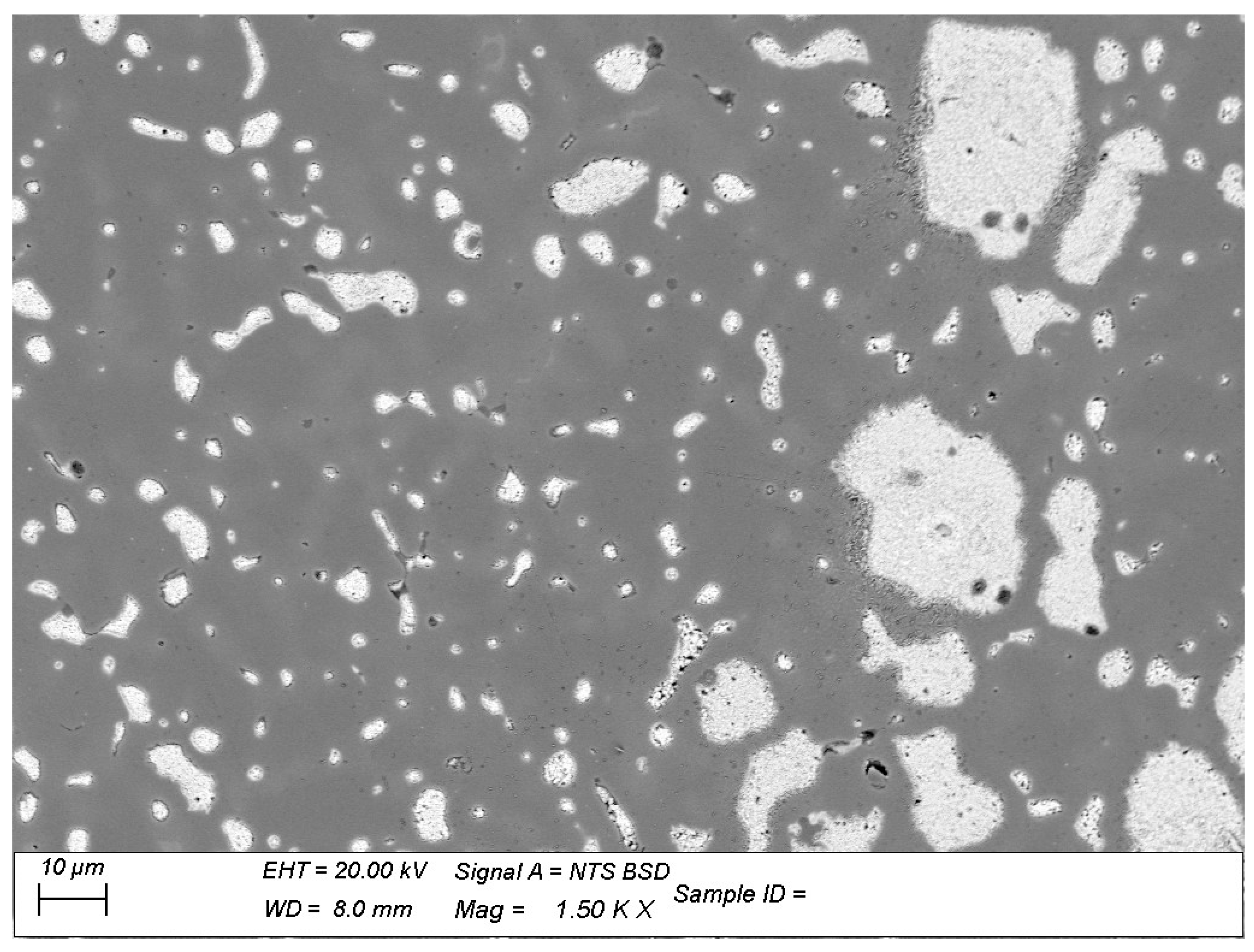

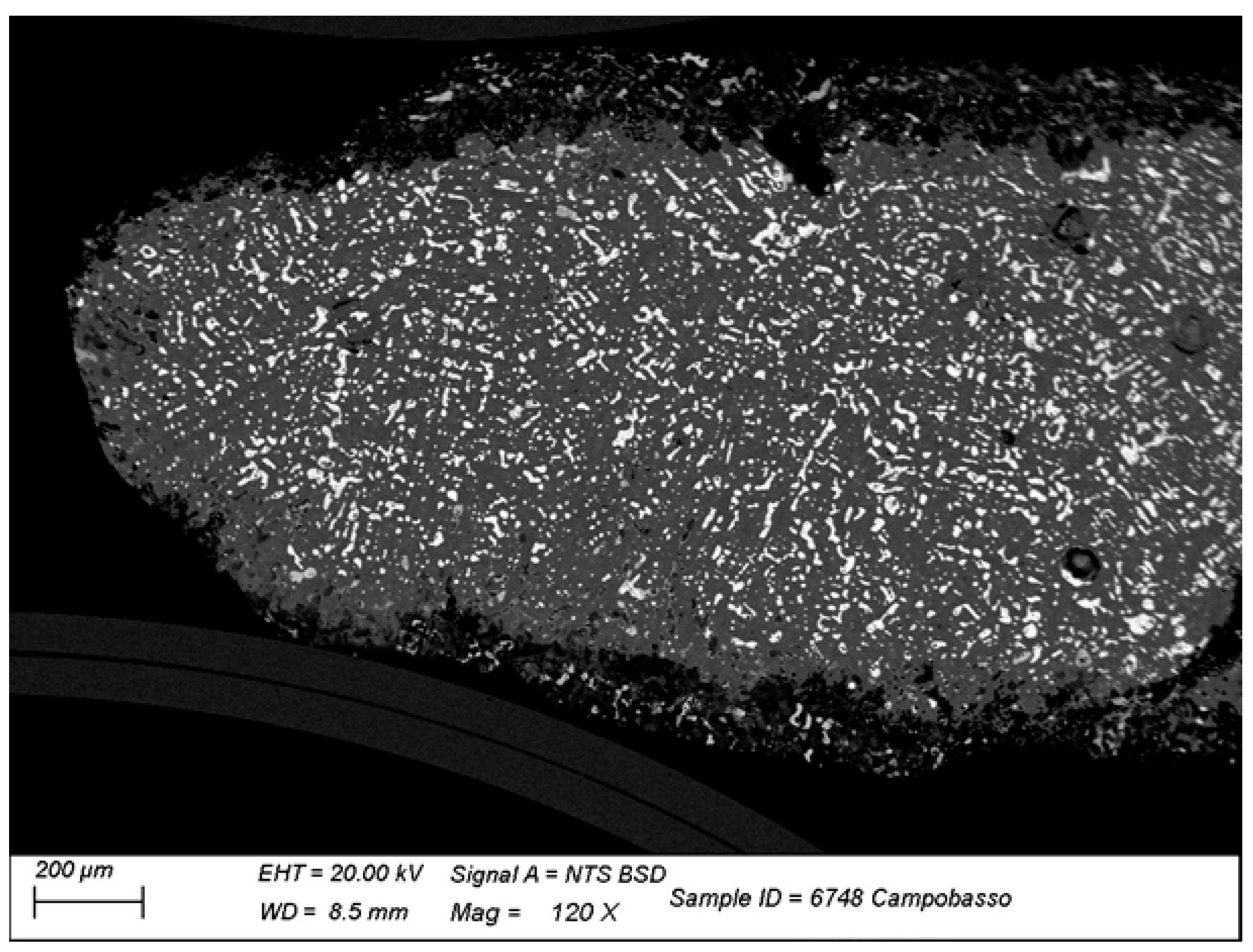

3.1.2. SEM-EDS Results

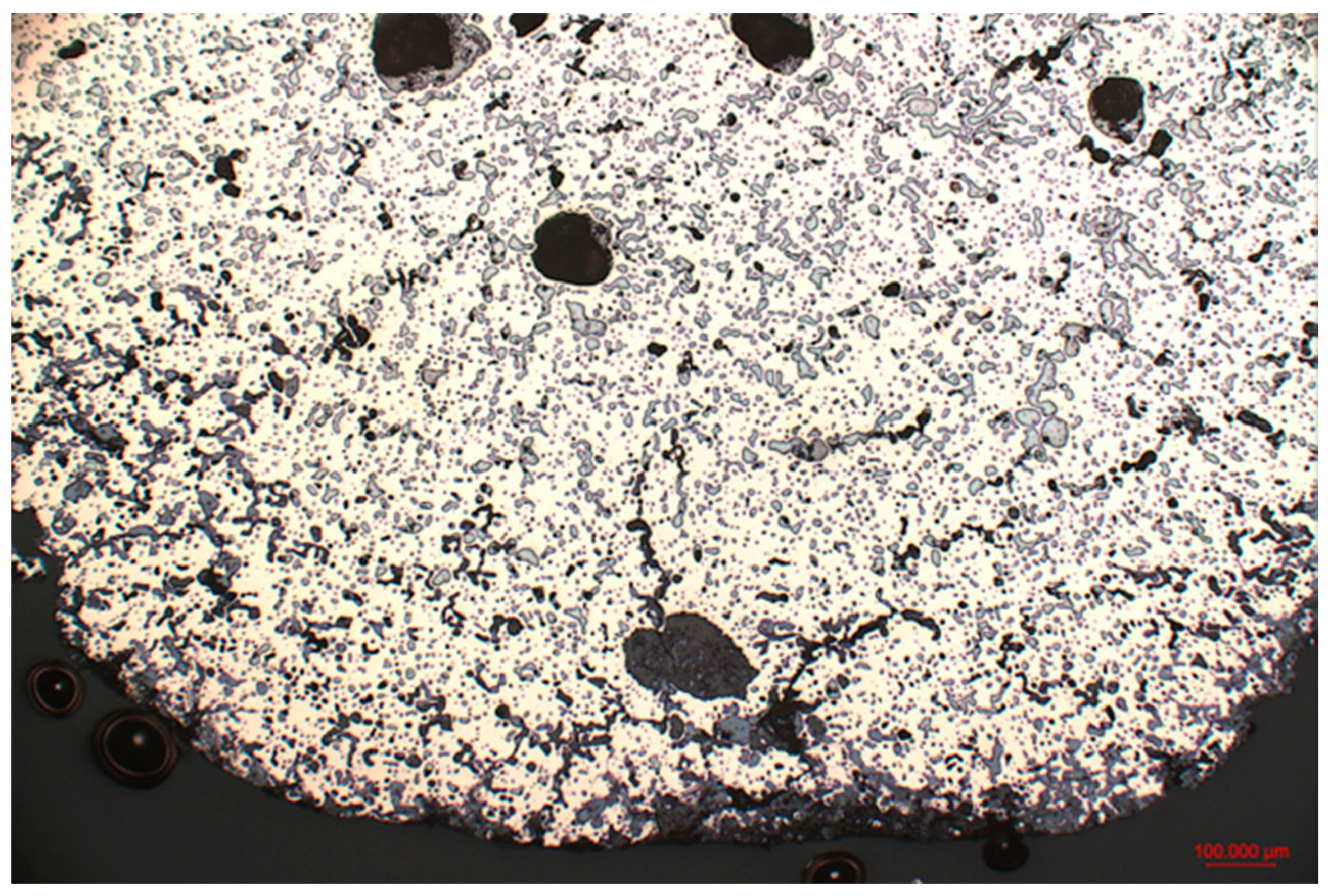

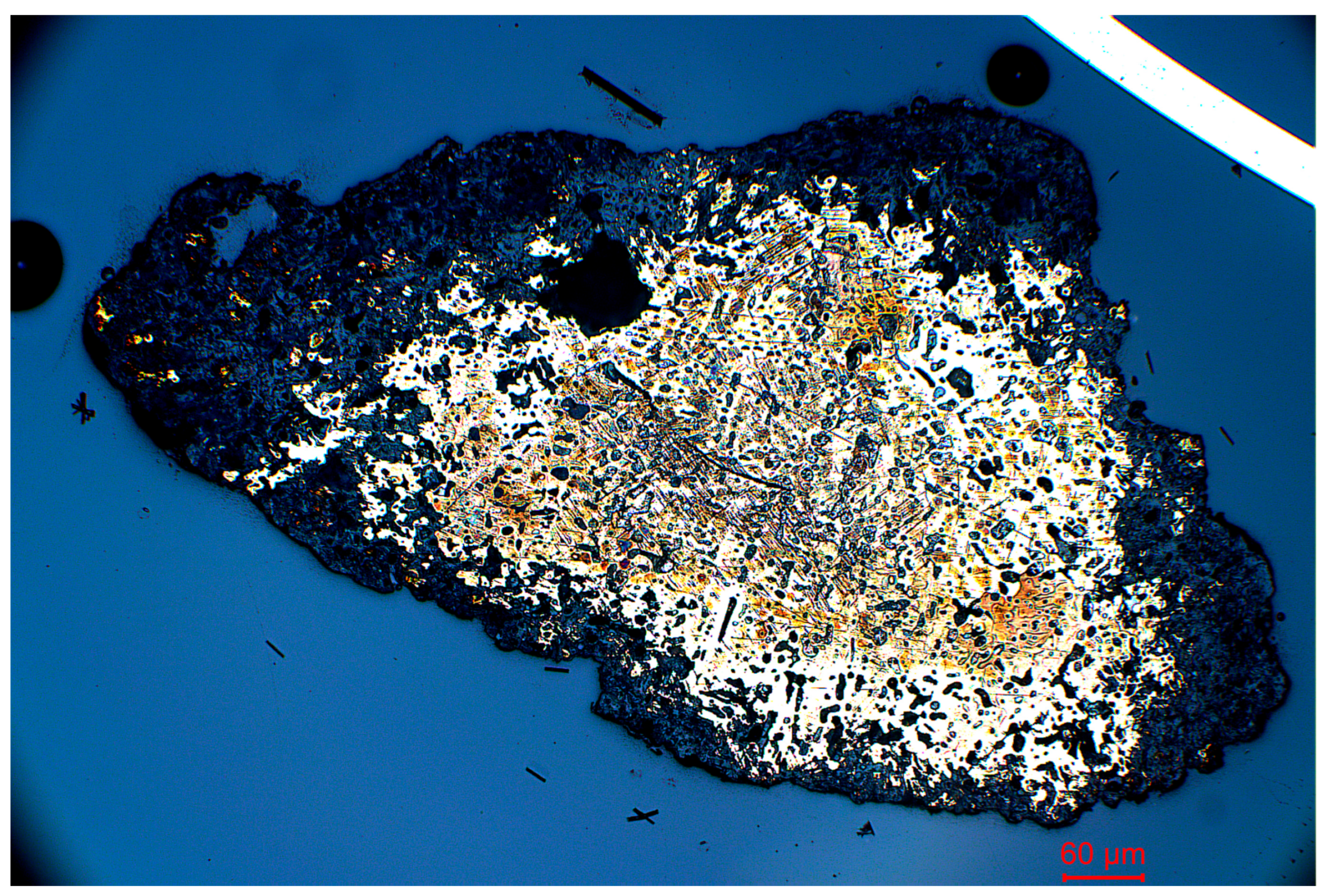

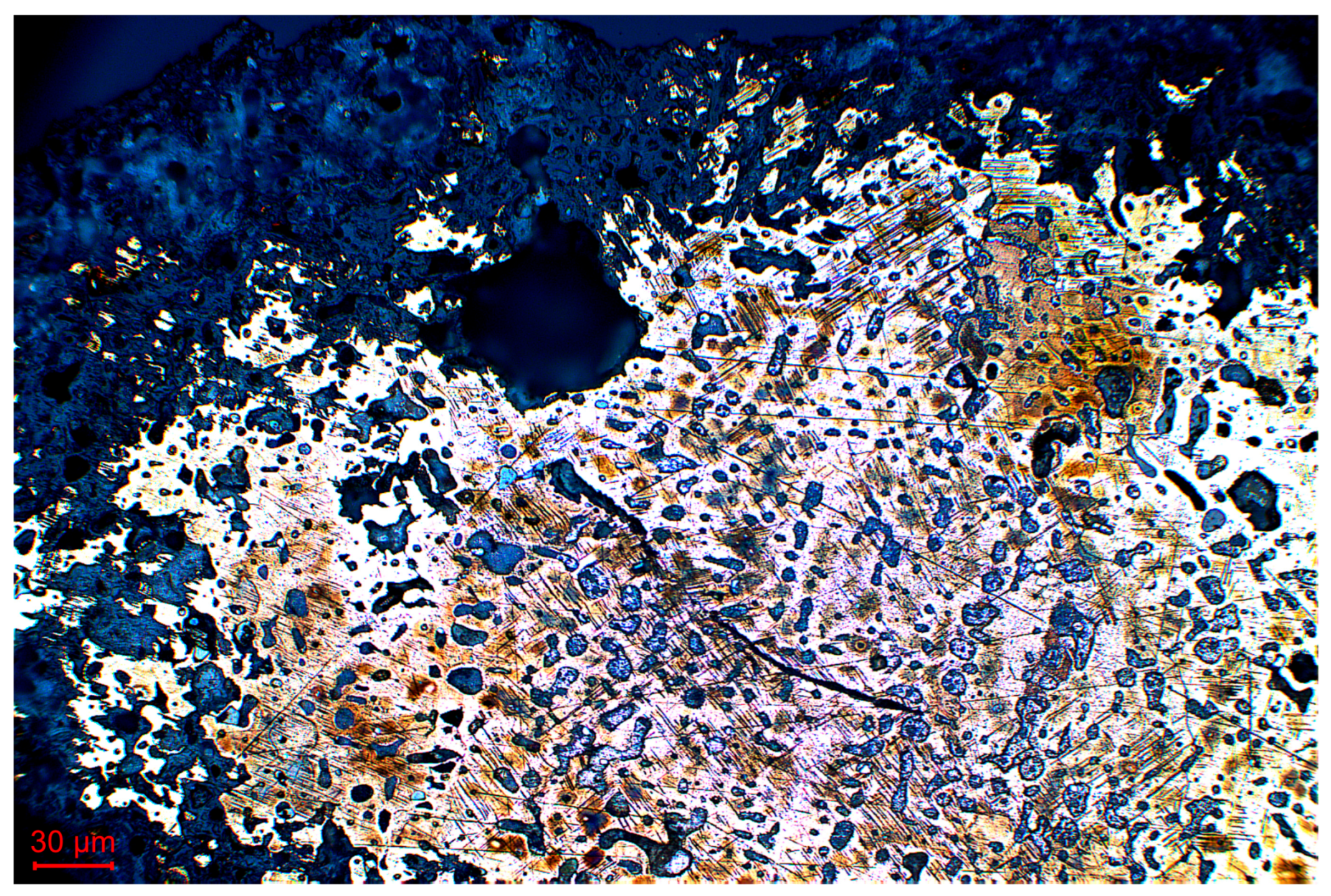

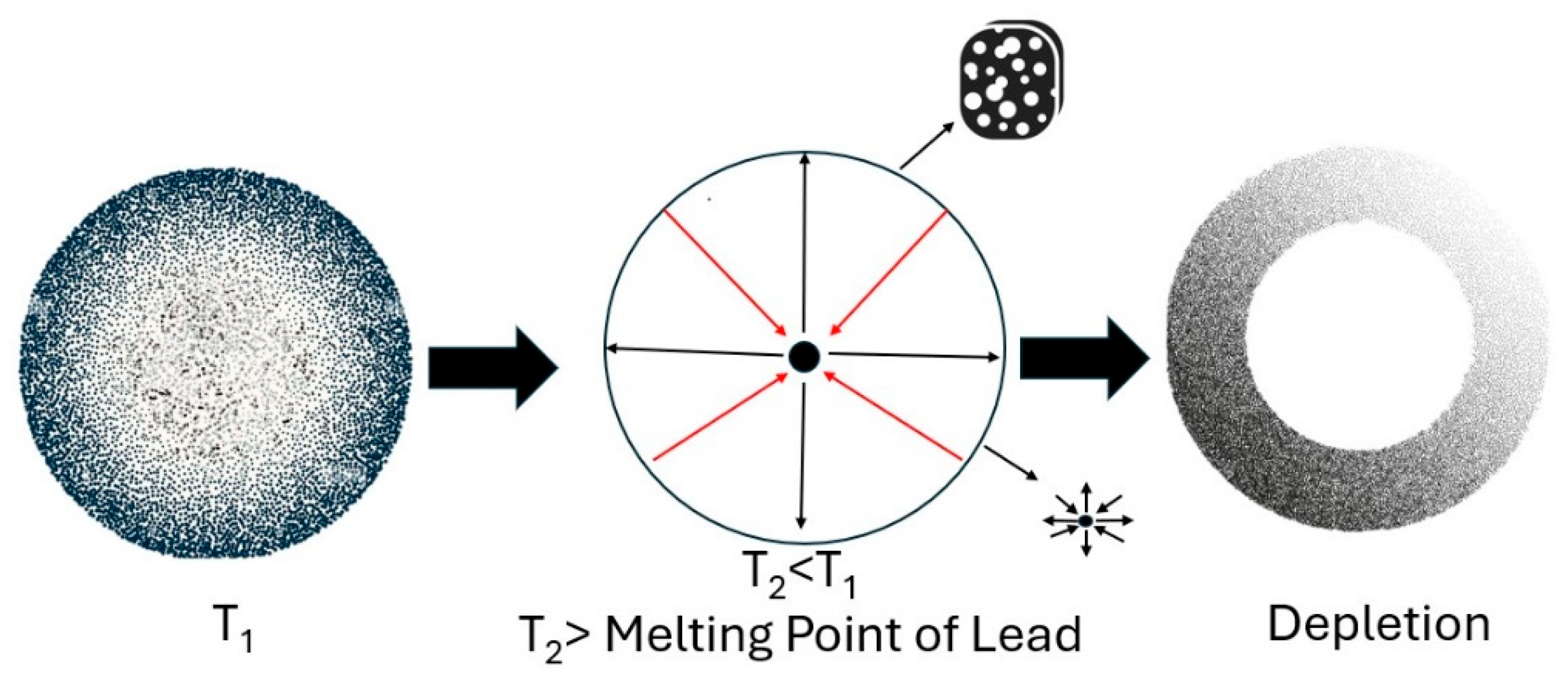

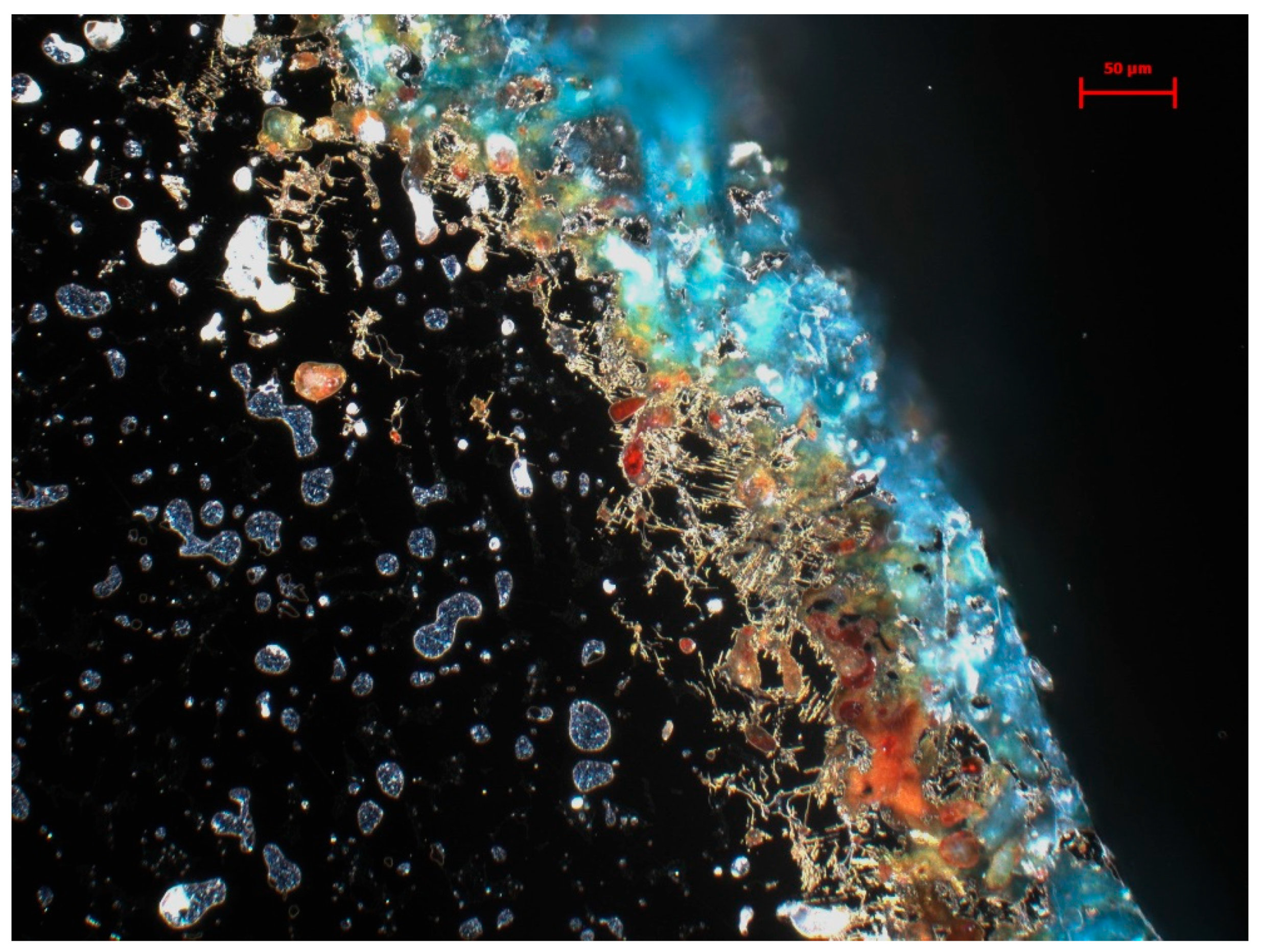

3.2. Metallography

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Delfino, D. Il Museo Sannitico Di Campobasso. Un Viaggio Di 4.000 Anni Nella Storia Del Sannio; 2020.

- Sîrbu, V.; Peţan, A. Temples and Cult Places from the Second Iron Age in Europe: Proceedings of the 2nd International Colloquium “Iron Age Sanctuaries and Cult Places at the Thracians and Their Neighbours”, Alun (Romania), 7th-9th May 2019; Dacica: Alun, 2020.

- Piccardo, P.; Ghiara, G.; Vernet, J. M. Mise En Œuvre Des Alliages Cuivreux : Faire Parler Le Métal Grâce à La Science Des Matériaux. In: M. Pernot, Quatre mille ans d'historie du cuivre, fragments d'une suite de rebonds, Presses universitaires de Bordeaux, collection THEA, 2017,m pp 41-60.

- Piccardo, P.; Amendola, R.; Adobati, A.; Faletti, C. STUDIO DELLA FLUIDITÀ DI LEGHE A BASE RAME, Metallurgia Italiana, 2009, pp 31-38.

- Kohler, F.; Germond, L.; Wagnière, J.-D.; Rappaz, M. Peritectic Solidification of Cu–Sn Alloys: Microstructural Competition at Low Speed. Acta Mater. 2009, 57 (1), 56–68. [CrossRef]

- Piccardo, P.; Mille, B.; Robbiola, L. 14 - Tin and Copper Oxides in Corroded Archaeological Bronzes. In Corrosion of Metallic he Heritage Artefacts; Dillmann, P., Béranger, G., Piccardo, P., Matthiesen, H., Eds.; European Federation of Corrosion (EFC) Series; Woodhead Publishing, 2007; Vol. 48, pp 239–262. [CrossRef]

- Paul, A.; Ghosh, C.; Boettinger, W. Diffusion Parameters and Growth Mechanism of Phases in the Cu-Sn System. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2011, 42, 952–963. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A. Segregation in Cast Products. Sadhana 2001, 26 (1–2), 5–24. [CrossRef]

- Harries, D. R.; Marwick, A. D. Non-Equilibrium Segregation in Metals and Alloys. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. Math. Phys. Sci. 1980, 295 (1413), 197–207.

- Khoza, I. NMC 313 - Materials Science Practical 1: Segregation During Solidification., 2016.

- Abdelbar, M.; El-Shamy, A. M. Understanding Soil Factors in Corrosion and Conservation of Buried Bronze Statuettes: Insights for Preservation Strategies. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14 (1). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Deng, C. Grain Boundary Interstitial Segregation in Substitutional Binary Alloys. Acta Mater. 2025, 291, 121019. [CrossRef]

- Assunção, M.; Vynnycky, M. On Macrosegregation in a Binary Alloy Undergoing Solidification Shrinkage. Eur. J. Appl. Math. 2024, 35 (1), 40–61. [CrossRef]

- CUI, H.; GUO, J.; su, Y.; DING, H.; WU, S.; BI, W.; XU, D.; FU, H. Microstructure Evolution of Cu-Pb Monotectic Alloys during Directional Solidification. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China - TRANS NONFERROUS Met. SOC CH 2006, 16, 783–790. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zheng, J.; Li, X.; Niu, C.; Peng, L.; Wan, F.; Liu, Z.; Zuo, Y.; Xue, C.; Cheng, B. Investigation of Lead Surface Segregation during Germanium–Lead Epitaxial Growth. J. Mater. Sci. 2020, 55 (11), 4762–4768. [CrossRef]

- Inverse Segregation - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics. https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/engineering/inverse-segregation (accessed 2025-07-16).

- Robbiola, L.; Portier, R. A Global Approach to the Authentication of Ancient Bronzes Based on the Characterization of the Alloy–Patina–Environment System. J. Cult. Herit. 2006, 7 (1), 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Nord, A. G.; Mattsson, E.; Tronner, K. Factors Influencing the Long-Term Corrosion of Bronze Artefacts in Soil. Prot. Met. 2005, 41 (4), 309–316. [CrossRef]

- Eggert, G. ‘Copper and Bronze in Art’ and the Search for Rare Corrosion Products. Heritage 2023, 6 (2), 1768–1784. [CrossRef]

- Nessel, B.; Brügmann, G.; Frank, C.; Marahrens, J.; Pernicka, E. Tin Provenance and Raw Material Supply – Considerations about the Spread of Bronze Metallurgy in Europe. METALLA 2019, 24 (2), 65–72. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Handwerker, C. A.; Dayananda, M. A. Intrinsic and Interdiffusion in Cu-Sn System. J. Phase Equilibria Diffus. 2011, 32 (4), 309–319. [CrossRef]

- Macrosegregation - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics. https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/engineering/macrosegregation (accessed 2025-07-16).

| N.Hercules | p-XRF | Sampling | LOM | SEM |

| Herc_1 | X | X | X | X |

| Herc_2 | X | |||

| Herc_3 | X | |||

| Herc_4 | X | X | X | X |

| Herc_5 | X | |||

| Herc_6 | X | X | X | X |

| Herc_1002 | X | |||

| Herc_1005 | X | X | X | X |

| Herc_1006 | X | X | X | X |

| Herc_1009 | X | X | X | X |

| Herc_1013 | X | X | X | X |

| Herc_1014 | X | |||

| Herc_1019 | X | |||

| Herc_1025 | X | X | X | X |

| Herc_1028 | X | X | X | X |

| Herc_1031 | X | |||

| Herc_1033 | X | |||

| Herc_1035 | X | |||

| Herc_4137 | X | X | X | X |

| Herc_6748 | X | X | X | X |

| Herc_34904 | X | |||

| Herc_34905 | X | |||

| Herc_34906 | X | |||

| Herc_42491 | X | |||

| Herc_58342 | X | X | X | X |

| N. Hercules | Cu* | Sn* | Pb* |

| Herc_1 | 35 ± 0,1 | 49 ± 0,2 | 17 ± 0,1 |

| Herc_2 | 50 ± 0,1 | 13 ± 0,1 | 37 ± 0,1 |

| Herc_3 | 62 ± 0,1 | 19± 0,1 | 19 ± 0,1 |

| Herc_4 | 47 ± 0,1 | 29 ± 0,1 | 24± 0,1 |

| Herc_5 | 52 ± 0,1 | 24 ± 0,1 | 23± 0,1 |

| Herc_6 | 34 ± 0,1 | 18 ± 0,1 | 48 ± 0,1 |

| Herc_1002 | 50 ± 0,1 | 15 ± 0,1 | 35 ± 0,1 |

| Herc_1005 | 51± 0,1 | 20 ± 0,1 | 29 ± 0,1 |

| Herc_1006 | 81 ± 0,1 | 7 ± 0,1 | 12 ± 0,1 |

| Herc_1009 | 52 ± 0,1 | 19 ± 0,1 | 29 ± 0,1 |

| Herc_1013 | 36 ± 0,1 | 44 ± 0,1 | 20 ± 0,1 |

| Herc_1014 | 45 ± 0,1 | 22 ± 0,2 | 34 ± 0,1 |

| Herc_1019 | 69 ± 0,1 | 15 ± 0,1 | 16± 0,1 |

| Herc_1025 | 40 ± 0,1 | 27 ± 0,1 | 33 ± 0,1 |

| Herc_1028 | 36 ± 0,1 | 16 ± 0,1 | 48 ± 0,1 |

| Herc_1031 | 39 ± 0,1 | 18± 0,1 | 43 ± 0,1 |

| Herc_1033 | 39 ± 0,1 | 21 ± 0,2 | 40 ± 0,1 |

| Herc_1035 | 54 ± 0,1 | 41 ± 0,1 | 5 ± 0,1 |

| Herc_4137 | 47 ± 0,1 | 16 ± 0,2 | 37 ± 0,2 |

| Herc_6748 | 45± 0,1 | 17 ± 0,1 | 38 ± 0,1 |

| Herc_34904 | 31 ± 0,1 | 60 ± 0,1 | 9 ± 0,1 |

| Herc_34905 | 54 ± 0,1 | 38 ± 0,1 | 8± 0,1 |

| Herc_34906 | 31 ± 0,1 | 30 ± 0,1 | 39 ± 0,1 |

| Herc_42491 | 46 ± 0,1 | 22 ± 0,1 | 32 ± 0,1 |

| Herc_58342 | 31 ± 0,1 | 56 ± 0,1 | 13 ± 0,1 |

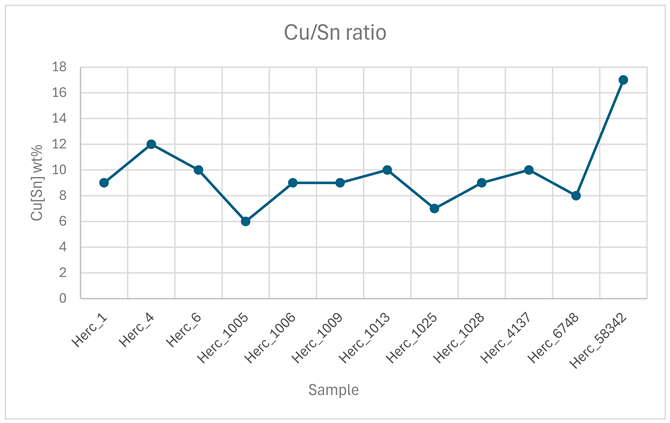

| N. Sample | Cu* | Sn* | Pb* | Cu**/Sn** |

| Herc_1 | 78±0.3 | 8±0.3 | 14±0.4 | 91/9 |

| Herc_4 | 75±0.3 | 10±0.3 | 15±0.4 | 88/12 |

| Herc_6 | 82±0.4 | 9±0.3 | 10±0.3 | 90/10 |

| Herc_1005 | 79±0.3 | 5±0.4 | 16±0.5 | 94/6 |

| Herc_1006 | 83±0.4 | 8±0.3 | 9±0.3 | 91/9 |

| Herc_1009 | 86±0.4 | 8±0.3 | 6±0.3 | 91/9 |

| Herc_1013 | 82±0.4 | 9±0.3 | 8±0.3 | 90/10 |

| Herc_1025 | 79±0.3 | 6±0.4 | 15±0.4 | 93/7 |

| Herc_1028 | 79±0.3 | 8±0.3 | 12±0.4 | 91/9 |

| Herc_4137 | 84±0.4 | 9±0.3 | 7±0.3 | 90/10 |

| Herc_6748 | 78±0.3 | 7±0.3 | 15±0.4 | 92/8 |

| Herc_58342 | 79±0.3 | 16±0.5 | 5±0.3 | 83/17 |

|

| N. Sample | O* | Si* | Cl* | Fe* | Cu* | Sn* | Pb* | Ca* |

| Herc_1 | XXXX | X | X | X | XXXX | XXXX | X | XXXX |

| Herc_4 | XXX | X | X | XXXXX | XXX | XXX | ||

| Herc_6 | XXXX | X | X | XXXX | X | XXXX | ||

| Herc_1005 | XX | X | X | XXX | XX | XXXX | X | |

| Herc_1006 | X | X | X | X | XXXX | X | XXX | |

| Herc_1009 | X | X | X | X | XXX | XX | XXXX | |

| Herc_1013 | XX | X | X | XXXX | XX | XX | ||

| Herc_1025 | XX | X | XXXXX | X | XX | |||

| Herc_1028 | X | X | X | XXXXXX | X | X | X | |

| Herc_4137 | XX | X | X | XXXXX | XX | X | ||

| Herc_6748 | XX | X | X | X | XX | XXX | XXX | |

| Herc_58342 | XXX | X | X | X | XX | XXX | X |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).