1. Introduction

Climate change has substantially increased the frequency, intensity, and uncertainty of flood hazards, placing unprecedented pressure on urban flood risk management systems worldwide. Conventional flood management approaches—primarily based on engineered defences and floodplain regulation—were historically designed under assumptions of climatic stability and predictable hydrological extremes. Recent flood disasters, however, have demonstrated that these assumptions are increasingly invalid under contemporary climate dynamics (Klijn et al., 2015; Spencer et al., 2017). Floodplains, often promoted as nature-based solutions for flood risk reduction, are now central to debates on adaptive flood governance. However, their effectiveness is highly contingent on local environmental conditions, land-use dynamics, and governance capacity.

The flood events that struck New Orleans (USA) and Carlisle (UK) in 2005 illustrate not only the occurrence of extreme hydrological events but also the failure of existing flood risk governance frameworks to anticipate, absorb, and adapt to escalating risk. In both cities, floodplain policies and engineered defences proved insufficient when confronted with compound pressures arising from climatic extremes, urban development, and institutional fragmentation (Burby, 2006; Convery & Bailey, 2008). These cases reveal that flood risk is not solely a product of natural hazards, but is actively shaped by planning decisions, governance arrangements, and socio-political priorities. Understanding flood disasters as governance failures rather than isolated natural events is therefore essential for advancing disaster risk reduction under climate change.

Existing research on flood risk management has increasingly emphasized the potential of floodplains and nature-based solutions to enhance urban resilience by attenuating flood peaks and reducing downstream impacts. However, much of this literature assumes that floodplains function as inherently beneficial or scalable interventions, often underplaying the institutional, spatial, and social conditions required for their effective operation (Priest et al., 2016; Venkataramanan et al., 2019). As a result, limited attention has been paid to the circumstances under which floodplain-based strategies fail to reduce risk, or may even exacerbate vulnerability when poorly integrated into broader governance frameworks.

In particular, comparative insights into how floodplain performance is shaped by interactions between environmental constraints, urban development pressures, governance capacity, and civic participation remain scarce. While individual case studies have documented flood impacts in specific cities, fewer studies explicitly examine floodplains as governance instruments whose effectiveness depends on decision-making processes, policy coordination, and social acceptance (Mehring et al., 2018; Hudson et al., 2019). This gap is especially salient under climate change, where increasing uncertainty and extreme events challenge static floodplain design assumptions and demand adaptive, context-sensitive approaches to disaster risk reduction.

Against this background, this study aims to examine the context-dependent effectiveness of floodplain-based flood management strategies under conditions of increasing climatic extremes. Specifically, it investigates how floodplains function—or fail to function—as flood risk-reduction instruments when embedded in different environmental settings and governance arrangements. To address this objective, the study adopts a qualitative comparative case study approach, focusing on New Orleans (USA) and Carlisle (UK), two flood-prone cities that experienced severe flooding in 2005 but differ markedly in geomorphology, hydrological regimes, governance structures, and socio-economic contexts.

The comparison of these cases enables an examination of how similar flood outcomes can emerge from distinct physical and institutional conditions, thereby illuminating shared risk governance challenges beyond site-specific factors. By analysing flood causes, floodplain roles, and post-event governance responses, this study identifies key mechanisms shaping floodplain performance and their implications for urban disaster risk reduction. Rather than seeking universal policy prescriptions, the analysis highlights the importance of place-based, adaptive flood governance in managing flood risk under climate change.

2. Limitations of Conventional Flood Defence Strategies

2.1. Structural Flood Defences and Their Risk Limitations

Conventional flood defence strategies have historically relied on structural measures such as levees, floodwalls, dams, and reservoirs to protect urban areas from inundation. These interventions were primarily designed to reduce flood probability by containing or diverting water flows under assumed design thresholds (Klijn et al., 2015). While such measures have been effective in managing frequent, low- to medium-magnitude flood events, their performance is fundamentally constrained by static design assumptions that fail to account for increasing climatic variability and extreme hydrological conditions.

Under climate change, the probability of flood events exceeding design standards has increased substantially, exposing urban areas to residual and systemic risk. Structural defences may create a false sense of security, encouraging urban expansion and asset concentration in protected areas, thereby amplifying potential losses when defences fail (Burby, 2001). As a result, flood risk is not eliminated but redistributed and, in some cases, intensified. These dynamics have led to growing recognition that engineering-based protection alone cannot ensure effective disaster risk reduction in flood-prone cities.

2.2. Flood Defence Failure as a Governance Problem

The flood disasters experienced in New Orleans and Carlisle demonstrate that the failure of structural flood defences cannot be understood solely as a technical malfunction, but must be analysed as a governance failure shaped by planning decisions, institutional fragmentation, and long-term land-use trajectories. In New Orleans, the extensive levee system was designed to protect a city located mainly below sea level; however, Hurricane Katrina exceeded these design assumptions, leading to widespread breaching and catastrophic inundation (Burby, 2006). The disaster revealed how reliance on engineered protection, combined with wetland degradation and delayed infrastructure maintenance, produced systemic vulnerability rather than resilience.

Similarly, in Carlisle, floodwalls and embankments along the River Eden and its tributaries were overtopped during extreme rainfall events in 2005 and again in 2015, despite post-event upgrades (Convery and Bailey, 2008; Spencer et al., 2017). These events highlight how flood defence standards based on historical hydrological records are increasingly misaligned with contemporary risk conditions. In both cases, governance constraints—including limited financial capacity, delayed implementation, and fragmented responsibility across agencies—restricted the ability of flood management systems to adapt proactively to escalating risk.

2.3. Implications for Floodplain-Based Strategies

The limitations of conventional flood defences have intensified interest in floodplains and other nature-based solutions as alternatives or complements to engineered protection. Floodplains are often expected to attenuate flood peaks by temporarily storing excess water and restoring hydrological connectivity. However, when floodplains are treated as isolated technical fixes rather than components of integrated risk governance systems, their effectiveness remains limited.

Both New Orleans and Carlisle demonstrate that floodplains cannot compensate for governance failures embedded in land-use planning, urban expansion, and institutional coordination. Where floodplains are constrained by urban development, ecological degradation, or conflicting policy objectives, their capacity to reduce flood risk is significantly undermined. These cases suggest that floodplain-based strategies do not inherently resolve flood risk challenges, but instead require supportive governance frameworks, adaptive planning, and alignment with broader disaster risk reduction objectives.

3. Case Study: New Orleans, USA

3.1. Flood Risk Context and Governance Constraints

New Orleans is located within the Mississippi River Delta, a low-lying coastal landscape where approximately 80% of the urban area lies below sea level. The combined effects of riverine flooding, hurricane-induced storm surges, subsidence, and sea-level rise shape flood risk in the city. Historically, flood risk management in New Orleans has relied heavily on large-scale structural defences, particularly levees, floodwalls, and pumping systems designed to protect urban development from both fluvial and coastal flooding (Burby, 2001; Colten, 2018).

This engineering-dominated approach has been accompanied by long-term ecological degradation, most notably the extensive loss of coastal wetlands that previously served as natural buffers against storm surges. Between the early twentieth century and the early 2000s, coastal Louisiana experienced substantial wetland loss driven by urban expansion, navigation infrastructure, and oil and gas extraction, significantly reducing the region’s flood attenuation capacity (Hupp et al., 2009; Cutter et al., 2018). As a result, flood risk in New Orleans has progressively intensified, not only due to climatic factors, but also as a consequence of cumulative planning and development decisions.

3.2. Hurricane Katrina as a Systemic Flood Risk Governance Failure

Hurricane Katrina in 2005 exposed the structural limitations of New Orleans’ flood risk management system when extreme conditions exceeded design assumptions. Storm surges and high water levels overtopped and breached multiple sections of the levee system, resulting in widespread inundation across the city (Seed et al., 2008). While the event is often framed as an unprecedented natural disaster, it more accurately represents a systemic failure of flood risk governance rooted in overreliance on engineered protection, delayed infrastructure maintenance, and insufficient consideration of compound risk.

The disaster demonstrated how structural defences, when treated as primary risk reduction instruments, can generate residual and systemic risk by encouraging urban development in highly vulnerable areas. Once defences fail, the consequences are catastrophic, particularly in cities where evacuation, emergency response, and recovery capacities are unevenly distributed. In this sense, Katrina revealed not only technical fragility but also institutional and social vulnerability embedded within the city’s flood governance framework (Burby, 2006; Kates et al., 2006).

3.3. Social Vulnerability and Unequal Risk Reduction Outcomes

Flood risk in New Orleans is further shaped by pronounced socio-economic inequalities that influence exposure, preparedness, and recovery capacity. During and after Hurricane Katrina, communities with lower incomes and limited access to political and institutional resources experienced disproportionately severe impacts and slower recovery trajectories (Cutter et al., 2018). These disparities highlight how flood risk reduction outcomes are mediated by civic participation, trust in governance institutions, and access to information.

Although substantial investments were made to rebuild and upgrade flood defences following Katrina, governance fragmentation and uneven community engagement constrained the long-term effectiveness of these measures. The post-disaster reconstruction process prioritised infrastructural reinforcement but addressed social vulnerability and participatory governance to a much lesser extent. Consequently, while structural protection standards improved, underlying drivers of flood risk—including land-use pressures, ecological degradation, and social inequality—remained largely unresolved.

3.4. Implications for Floodplain-Based Risk Reduction

The New Orleans case illustrates that floodplains and wetlands cannot serve as effective flood risk-reduction instruments in isolation from broader governance reforms. While wetland restoration and floodplain reconnection have been promoted as complementary strategies, their capacity to reduce flood risk is fundamentally constrained by ongoing urban development, fragmented institutional responsibilities, and limited integration with social planning objectives.

From a disaster risk reduction perspective, the failure observed in New Orleans underscores the need to conceptualise floodplains not merely as hydraulic buffers, but as governance-dependent interventions whose performance depends on coordinated land-use regulation, long-term ecological management, and inclusive decision-making processes. Without such integration, floodplain-based strategies risk reproducing the same vulnerabilities that undermined earlier engineering-dominated approaches.

4. Case Study: Carlisle, UK

4.1. Flood Risk Context and Catchment Characteristics

Carlisle is located in northwest England at the confluence of three rivers—the Eden, Caldew, and Petteril—making it inherently vulnerable to fluvial flooding. Flood risk in the city is primarily driven by prolonged and intense rainfall events within the upstream catchment, rather than by coastal storm surges as in New Orleans. The regional climate is characterised by high precipitation associated with Atlantic weather systems, and recent decades have seen an increase in extreme rainfall intensity consistent with broader climatic trends (Spencer et al., 2017).

Flood risk management in Carlisle has traditionally relied on a combination of engineered flood defences, including embankments and floodwalls, alongside designated floodplains intended to store excess water during high-flow events. These measures were designed based on historical hydrological records and standard protection levels, assuming relatively stable climatic conditions. However, repeated flood events since 2005 have increasingly challenged the adequacy of this approach under changing rainfall regimes.

4.2. Recurrent Flooding as a Failure of Adaptive Flood Governance

Severe flooding in Carlisle in January 2005 revealed the vulnerability of the city’s flood risk management system when prolonged rainfall caused river flows to exceed the capacity of defences. Despite subsequent investments in flood protection, Storm Desmond in December 2015 again overwhelmed flood defences, inundating more than 2,000 properties and causing widespread disruption to infrastructure and services (Convery and Bailey, 2008; Spencer et al., 2017). These recurrent events demonstrate that flood risk management in Carlisle has struggled to adapt to escalating hydrological extremes.

Rather than representing isolated failures of individual structures, the repeated flooding highlights limitations in adaptive flood governance. Protection standards based on historical flood frequencies proved insufficient under intensifying rainfall, while delays in implementation and constrained funding limited the scope of post-event upgrades. As a result, flood risk reduction efforts lagged behind rapidly evolving hazard conditions, producing a growing gap between protection design and actual risk.

4.3. Floodplains, Land-Use Pressures, and Unintended Risk Amplification

Floodplains in and around Carlisle have been promoted as natural flood management measures capable of attenuating peak flows and reducing downstream impacts. In practice, however, their effectiveness has been undermined by land-use change, soil compaction, and urban development encroachment. Large portions of floodplain areas have been converted into impermeable surfaces or intensively managed land, significantly reducing their water storage capacity (Entwistle and Heritage, 2016).

Empirical studies indicate that, rather than functioning as controlled retention zones, some floodplain areas in Carlisle have become saturated prior to flood events, limiting their capacity to absorb additional water and, in some cases, exacerbating local flooding. These outcomes reflect a mismatch between floodplain policy objectives and actual land management practices, revealing how floodplains can amplify risk when governance mechanisms fail to regulate competing land-use interests effectively.

4.4. Social Impacts and Governance Constraints

Beyond physical damage, recurrent flooding in Carlisle has generated substantial social and psychological impacts, including increased anxiety, reduced well-being, and heightened consideration of relocation among residents (Convery and Bailey, 2008). Although public consultation processes are formally embedded within UK flood risk governance, civic participation has often been procedural rather than substantive, limiting the incorporation of local knowledge into decision-making (Mehring et al., 2018).

Local governance capacity has further constrained flood risk reduction efforts. Limited financial resources, multi-level approval requirements, and competing development priorities have delayed maintenance and adaptation of flood defences and floodplain areas. Consequently, floodplains in Carlisle illustrate how nature-based solutions cannot deliver effective disaster risk reduction without sustained institutional support, coordinated land-use planning, and meaningful civic engagement.

4.5. Implications for Floodplain-Based Risk Reduction

The Carlisle case demonstrates that floodplain-based strategies are susceptible to catchment-scale processes and governance arrangements. While floodplains offer potential benefits for flood attenuation, their performance depends on long-term land management, regulatory enforcement, and adaptive planning that can respond to evolving climatic risks.

From a disaster risk reduction perspective, Carlisle highlights the limitations of implementing floodplain policies as static or supplementary measures within otherwise unchanged governance frameworks. Without continuous adaptation and integration across policy domains, floodplains risk becoming symbolic rather than functional components of flood risk management, offering limited protection under increasingly extreme conditions.

5. Comparative Discussion: Evidence-Informed Mechanisms Across the Two Cases

5.1. Intensifying Climatic Conditions and Design–Risk Misalignment

The two case studies illustrate a growing mismatch between historical design assumptions in flood management and evolving climatic conditions. In New Orleans,

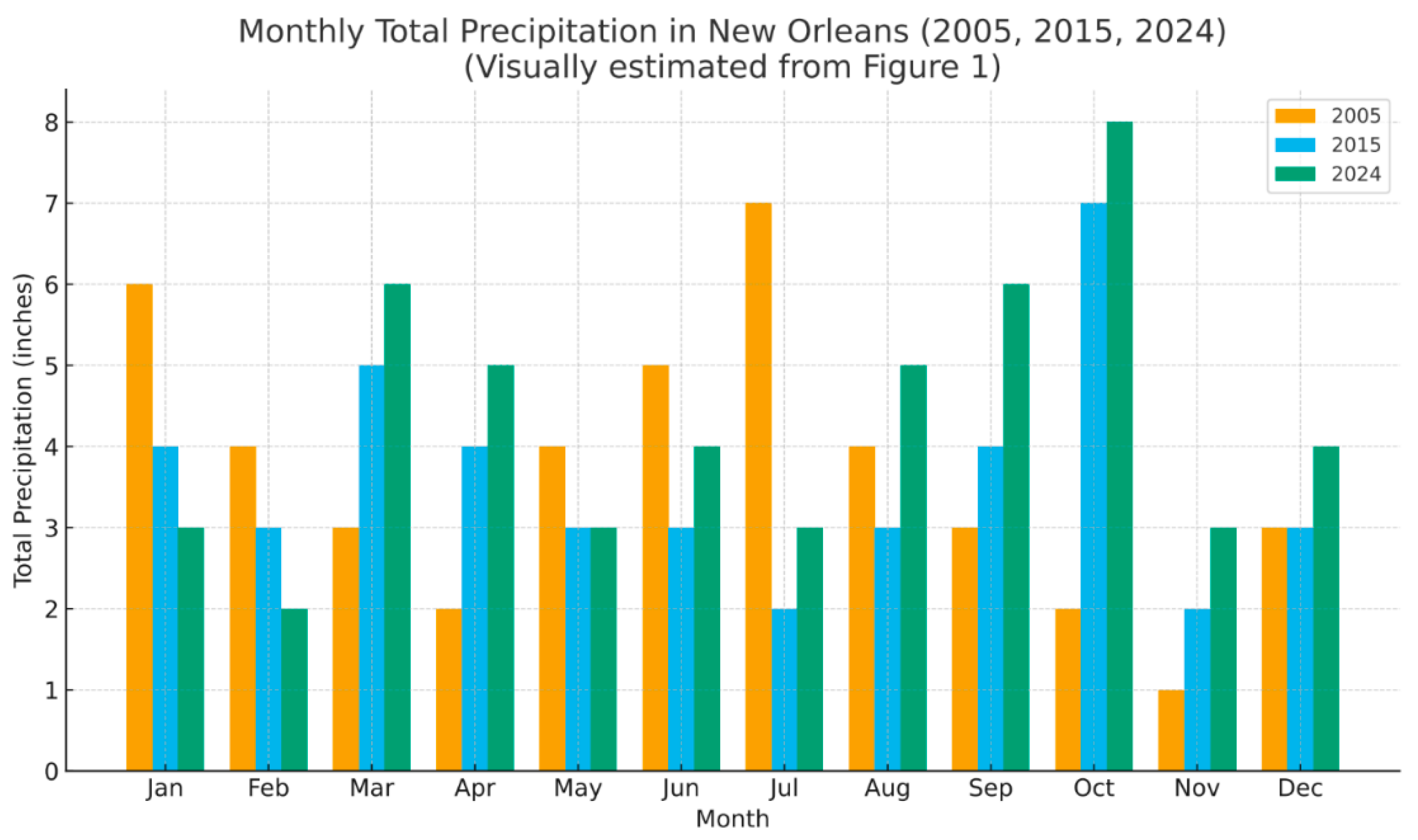

Figure 1 (monthly total precipitation for 2005, 2015, and 2024) indicates substantial interannual variability and periods of elevated rainfall totals, particularly in late summer and autumn, which are critical seasons for compound flood risk in coastal cities. While this figure alone cannot establish a long-term trend, it provides case-level evidence that recent precipitation patterns can exceed the practical operating conditions assumed by conventional flood defences and drainage systems, thereby increasing residual flood risk.

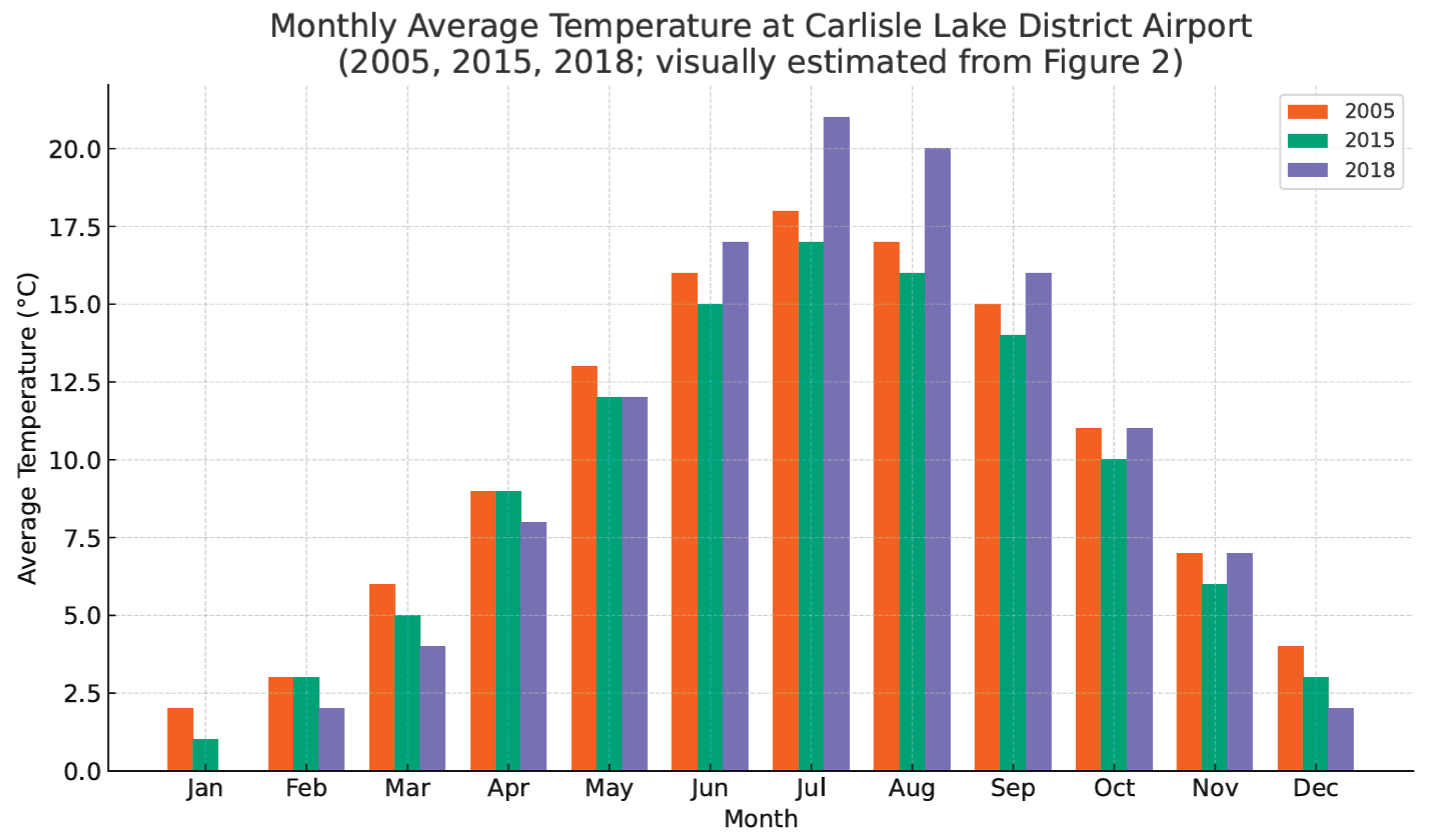

In Carlisle, the climatic pressure manifests differently.

Figure 2 (monthly average temperature at Carlisle Lake District Airport for 2005, 2015, and 2018) shows warmer seasonal conditions in the later observation year(s) for several months, signalling an evolving climatic context. Although temperature is not a direct proxy for flood discharge, warmer atmospheric conditions can intensify the hydrological cycle and interact with storm systems, contributing to risk environments in which historical flood protection standards may become increasingly misaligned with actual hazard regimes. Taken together, these figures support the argument that flood risk governance must move beyond static design baselines and incorporate adaptive planning in the face of climatic uncertainty (Klijn et al., 2015; Spencer et al., 2017).

5.2. Exposure Growth and the Paradox of Protection in New Orleans

The New Orleans case further demonstrates that flood risk is shaped not only by hazard intensity but also by changing exposure patterns.

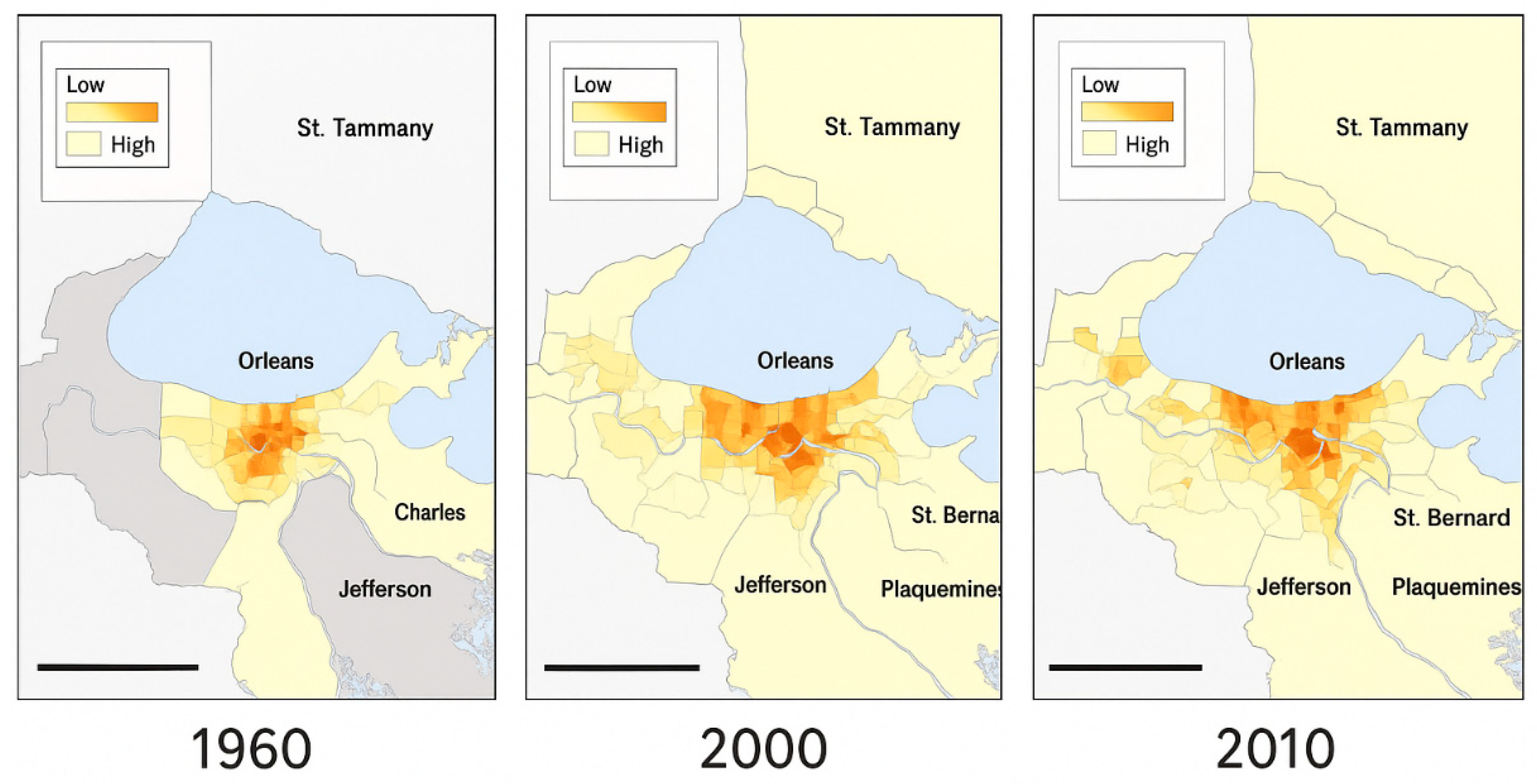

Figure 3 (density of occupied housing units in the New Orleans metropolitan area, 1960–2010) visualises pronounced urban expansion and increasing residential concentration over time. This spatial growth pattern is consistent with a well-documented risk dynamic: structural protection and floodplain regulation can create a “security effect” that encourages development behind defences, increasing the number of people and assets exposed when protection fails (Burby, 2001).

From a disaster risk reduction perspective,

Figure 3 strengthens the interpretation of Hurricane Katrina as a systemic governance failure rather than an isolated natural event: urban expansion and land-use decisions, interacting with engineered protection and ecological degradation, produced an increasingly brittle urban risk configuration (Burby, 2006; Cutter et al., 2018). Significantly, this mechanism also constrains the effectiveness of floodplain-based strategies—where floodplain space is limited or gradually encroached upon, its buffering capacity becomes governance-dependent rather than “naturally available”.

5.3. Why Floodplains Fail as Universal Solutions Across Contexts

The comparative evidence indicates that floodplains cannot be treated as universally reliable instruments for flood risk reduction. In New Orleans, floodplain and wetland functions have been progressively weakened by long-term land conversion and urban expansion pressures. At the same time, risk management has remained dominated by levees and pumping systems. In Carlisle, although flood risk is primarily fluvial and catchment-driven, recurrent extreme events have repeatedly tested the limits of engineered defences and the practical capacity of floodplain storage, mainly where land management and maintenance constrain infiltration and retention performance.

Across both cases, the core lesson is that floodplain strategies deliver risk reduction benefits only when embedded within integrated flood risk management frameworks that align (i) evolving climatic conditions, (ii) spatial planning and development control, and (iii) governance capacity for long-term maintenance and coordinated action. Without this alignment, floodplains risk becoming symbolic policy components—present in planning documents but unable to deliver measurable reductions in disaster risk under extreme conditions.

5.4. Implications for Disaster Risk Reduction Under Climate Change

For IJDRR’s disaster risk reduction agenda, these cases indicate that the central policy challenge is not simply whether floodplains should be restored, but how they are governed under conditions of competing land-use pressures and increasing climatic uncertainty. Evidence from

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 demonstrates that effective floodplain-based risk reduction requires adaptive governance capable of routinely reassessing design assumptions against evolving hazard conditions rather than relying on static historical thresholds. At the same time, flood risk reduction depends on exposure-aware spatial planning that limits the concentration of people and assets behind protective structures, as such protection can otherwise unintentionally amplify disaster consequences (Burby, 2001). Crucially, floodplains function as governance-dependent interventions whose performance is shaped by regulatory enforcement, long-term maintenance capacity, and cross-sector coordination, rather than solely by ecological intent.

6. Conclusions

This study examined the performance and limitations of floodplain-based flood management strategies through a comparative case study of New Orleans (USA) and Carlisle (UK) under conditions of increasing climatic extremes. Despite substantial differences in geomorphology and flood-generating processes, both cases demonstrate that floodplains cannot be treated as universally reliable instruments for flood risk reduction. Instead, their effectiveness is shaped by the interaction of climatic pressures, land-use dynamics, governance capacity, and social vulnerability.

The comparative analysis shows that evolving climatic conditions have increasingly challenged the static design assumptions embedded in conventional flood management systems. As illustrated by the precipitation and temperature patterns presented in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2, recent hydro-climatic variability and extremes have exposed a growing misalignment between historical protection standards and contemporary risk environments. This misalignment constrains both engineered defences and floodplain-based strategies, increasing residual and systemic flood risk when extreme events exceed anticipated thresholds.

At the same time, the New Orleans case highlights how exposure growth driven by urban expansion can undermine flood risk reduction efforts.

Figure 3 demonstrates that long-term increases in residential density behind flood defences have amplified potential losses when protection fails, reinforcing the well-established paradox of protection. These findings underscore that flood risk is not solely a function of hazard intensity, but is actively produced through spatial planning decisions and governance choices that shape exposure and vulnerability over time.

Across both cases, floodplains emerge as governance-dependent interventions rather than inherently protective landscape features. Where floodplain space is constrained by development pressures, ecological degradation, or insufficient maintenance, its capacity to attenuate flood risk is significantly reduced. Moreover, fragmented institutional responsibilities and limited integration between land-use planning, infrastructure management, and community engagement further restrict the long-term effectiveness of floodplain strategies.

From a disaster risk reduction perspective, the results suggest that the key policy challenge is not whether floodplains should be restored, but how they are governed under competing land-use demands and climatic uncertainty. Effective floodplain-based risk reduction requires adaptive governance frameworks that regularly reassess design baselines, actively manage exposure growth, and ensure coordination across sectors and scales. Without such integration, floodplains risk becoming symbolic policy elements rather than functional components of urban flood risk management.

By demonstrating how similar flood outcomes can arise from different physical and institutional contexts, this study contributes transferable insights for flood risk governance beyond the two cases examined. For IJDRR’s broader agenda, the findings highlight the importance of moving beyond technical or nature-based solutions alone and towards place-based, adaptive approaches that explicitly address governance capacity, social equity, and long-term risk dynamics in an era of climate change.

Acknowledgments

The authors declare that during the preparation of this manuscript, ChatGPT, an AI language model developed by OpenAI, was utilised as an auxiliary tool for writing and editing. The tasks assisted by this tool included: linguistic refinement in line with journal specifications, structural optimisation, adjustments to reference formatting, and verification of content consistency. All conceptual development, data interpretation, analytical decisions, and final content revisions were independently completed and approved by the authors. The authors bear full responsibility for the integrity, originality, and accuracy of this work.

References

- Abass, K.; Buor, D.; Afriyie, K.; Dumedah, G.; Segbefi, A.Y.; Guodaar, L.; Garsonu, E.K.; Adu-Gyamfi, S.; Forkuor, D.; Ofosu, A.; Mohammed, A.; Gyasi, R.M. Urban sprawl and the depletion of green space: Implications for flood incidence in Kumasi, Ghana. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2020, 51, 101915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burby, R.J. Flood insurance and floodplain management: The US experience. Environmental Hazards 2001, 3(3), 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burby, R.J. Hurricane Katrina and the paradoxes of government disaster policy: Promoting wise governmental decisions in hazardous areas. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 2006, 604(1), 171–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colten, C.E. Raising New Orleans: Historical analogs and future environmental risks. Environmental History 2018, 23(1), 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Convery, I.; Bailey, C. After the flood: The health and social consequences of the 2005 Carlisle flood event. Journal of Flood Risk Management 2008, 1(2), 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutter, S.L.; Emrich, C.T.; Gall, M.; Reeves, R. Flash flood risk and the paradox of urban development. Natural Hazards Review 2018, 19(1), 05017005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entwistle, N.; Heritage, G. UK floods: Changes to rivers and floodplains have exacerbated flooding. Flood Risk Management and Policy Analysis 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Houser, M.; Gazley, B.; Reynolds, H.; Grennan Browning, E.; Sandweiss, E.; Shanahan, J. Public support for local adaptation policy: The role of social-psychological factors, perceived climatic stimuli, and social structural characteristics. Global Environmental Change 2022, 72, 102424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, P.; Botzen, W.J.W.; Poussin, J.; Aerts, J.C.J.H. Impacts of flooding and flood preparedness on subjective well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies 2019, 20(2), 665–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hupp, C.R.; Pierce, A.R.; Noe, G.B. Floodplain geomorphic processes and environmental impacts of human alteration along coastal plain rivers in the USA. Wetlands 2009, 29(2), 413–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kates, R.W.; Colten, C.E.; Laska, S.; Leatherman, S.P. Reconstruction of New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina: A research perspective. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2006, 103(40), 14653–14660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klijn, F.; Kreibich, H.; de Moel, H.; Penning-Rowsell, E. Adaptive flood risk management planning based on a comprehensive flood risk conceptualisation. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change 2015, 20(6), 845–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehring, P.; Geoghegan, H.; Cloke, H.L.; Clark, J.M. What is going wrong with community engagement? How flood communities and flood authorities construct engagement and partnership working. Environmental Science & Policy 2018, 89, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priest, S.J.; Suykens, C.; Van Rijswick, H.F.M.W.; Schellenberger, T.; Goytia, S.; Kundzewicz, Z.W.; van Doorn-Hoekveld, W.J.; Beyers, J.-C.; Homewood, S. The European Union approach to flood risk management and improving societal resilience. Ecology and Society 2016, 21(4), 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seed, R.B.; Bea, R.G.; Athanasopoulos-Zekkos, A.; Boutwell, G.P.; Bray, J.D.; Cheung, C.; Cobos-Roa, D.; Ehrensing, L.; Harder, L.F.; Pestana, J.M.; Riemer, M.F.; Rogers, J.D.; Storesund, R.; Vera-Grunauer, X.; Wartman, J. New Orleans and Hurricane Katrina. II: The Central Region and the Lower Ninth Ward. Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering 2008, 134(5), 718–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, P.; Faulkner, D.; Perkins, I.; Lindsay, D.; Dixon, G.; Parkes, M.; Lowe, A.; Asadullah, A.; Hearn, K.; Gaffney, L.; Parkes, A.; James, R. The floods of December 2015 in northern England: Description of the events and possible implications for flood hydrology in the UK. Hydrology Research 2017, 49(2), 568–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkataramanan, V.; Packman, A.I.; Peters, D.R.; Lopez, D.; McCuskey, D.J.; McDonald, R.I.; Miller, W.M.; Young, S.L. A systematic review of the human health and social well-being outcomes of green infrastructure for stormwater and flood management. Journal of Environmental Management 2019, 246, 868–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).