1. Introduction

The first evidence of biological effects induced by low-level laser irradiation was reported in 1967 by Hungarian physician Dr. Endre Mester [

1] at Semmelweis Medical University. His experiment aimed to replicate earlier work by McGuff [

2] in Boston, who had used high-power ruby lasers (694 nm) to treat malignant tumors in both animal models and human patients. However, Mester’s ruby laser possessed only a small fraction of McGuff’s power output. While he did not reproduce the antitumor effect, he unexpectedly observed accelerated hair regrowth in the treated group of mice, which had been shaved and surgically implanted with tumor tissue. This observation, later expanded through studies using helium-neon (HeNe) lasers (632.8 nm) on wound healing in both animals and clinical settings, gave rise to the concept of “laser biostimulation” - a phenomenon describing the ability of light to promote tissue repair without inducing thermal damage or ablation.

Initially, coherence was thought essential to these effects, but later research demonstrated that non-coherent light sources such as LEDs could produce similar outcomes. This shifted attention from light delivery properties to the biological pathways activated by wavelength, fluence, and dosing parameters, laying the foundation for photobiomodulation (PBM) as a therapeutic discipline.

In the following decades, PBM research expanded, focusing on underlying mechanisms and clinical applications [

3]. A key milestone was the work of Tina Karu [

4], who identified Cytochrome C oxidase (COX) as a mitochondrial chromophore for red and near-infrared light. Photon absorption by COX enhanced ATP production, modulated cellular redox states, and influenced the release of nitric oxide (NO) and reactive oxygen species (ROS). These findings provided a molecular basis for PBM’s effects and confirmed its potential to influence biological activity without significant temperature increases.

These insights translated into clinical use of low-power lasers and LEDs, typically delivering energy densities of J/cm², for conditions such as soft tissue injuries, chronic inflammation, peripheral neuropathies, and delayed wound healing [

5,

6].

Concurrently, standardization efforts led by Jan Turner and Lars Hode [

7] emphasized key parameters like wavelength, fluence, pulse structure, irradiation time, and tissue type. These contributed to early classifications distinguishing Low-Level Laser Therapy (LLLT), associated with photochemical stimulation, from High-Power Laser Therapy (HPLT) [

8], often used for thermal effects and ablation.

However, this binary model proved inadequate. Professor Leonardo Masotti, founder of El.En. Group and professor at the University of Florence, in 1997 introduced the term High-Intensity Laser Therapy (HILT) to define a distinct modality based on photoacoustic effects. The key parameter was not average power, while intensity, specifically, high-peak-power pulses (kilowatt range) delivered in short durations (tens to hundreds of microseconds), at low frequencies (5–30 Hz) and extremely low duty cycles (0.05–1%). This configuration enables high-energy delivery per pulse and the generation of acoustic pressure waves in tissue, thereby activating mechanosensitive pathways. To further formalize this concept, Fortuna and Masotti [

9] proposed the PIF (Peak Intensity Fluence), a mathematical model integrating pulse energy, duration, and frequency to distinguish true HILT devices from systems that produce only photochemical or photothermal effects. This distinction is essential: continuous-wave or quasi-continuous high-power lasers may exceed power thresholds but lack the capacity to induce optoacoustic waves. Misclassification of such devices as HILT risks conflating mechanisms and producing inconsistent clinical or scientific outcomes.

Recent in vitro investigations further refined our understanding of how PBM parameters affect cells. A review by Ohsugi et al. [

10] summarized how oral-related cells—epithelial, fibroblasts, osteocytes, osteoclasts, endothelial, and mesenchymal stem cells—respond differently depending on laser settings. For instance, diode lasers (810–910 nm) enhanced epithelial proliferation via MAPK/ERK and reduced pro-inflammatory cytokines in carcinoma cells. Gingival fibroblasts showed increased viability and decreased COX-2/PGE2 expression via Akt and JNK. Osteocytes and osteoclasts exhibited reduced sclerostin and increased osteogenic markers.

Parallel research by Hosseinpour et al. [

11] reviewed 49 studies on laser-assisted gene transfection. They identified three contributing mechanisms: photochemical internalization, photothermal modulation, and photoacoustic stimulation. While photochemical and photothermal processes improved uptake, only photoacoustic stimulation (achievable via high-peak, short-pulse lasers) was effective in vivo. This “triple effect” underscores the importance of delivering all three mechanisms simultaneously for optimal regenerative outcomes.

These findings are consistent with biomechanical studies. Research on hypergravity and shear stress (Tarantino et al. [

12], Monici et al. [

13], Cialdai et al. [

14], Genchi et al. [

15], De Cesari et al. [

16]) demonstrated that mechanical loading promotes cytoskeletal reorganization and gene expression. HILT systems, through photoacoustic waves, replicate these effects non-invasively and may serve as surrogates for mechanical therapies.

These findings underscore the importance of parameter-specific effects, suggesting that the biological outcomes of PBM cannot be predicted by output power alone. Rather, wavelength, pulse structure, and energy density must be carefully tailored to the biological target and clinical objective.

Recent experimental studies further confirmed that PBM outcomes depend not only on energy quantity, but on how light is delivered. In a study on osteoblast cultures, Sleep et al. [

17] demonstrated that even continuous-wave LED exposure with carefully selected energy density could transiently enhance mitochondrial respiration and osteogenic gene expression. However, this effect declined with repeated treatments, illustrating a biphasic response typical of photochemical-only stimulation. These findings emphasize that photochemical mechanisms alone, although biologically active, may be insufficient for sustained regenerative stimulation. This supports the notion that only laser systems capable of inducing all three mechanisms (photochemical, photothermal, and photoacoustic) - can achieve what we term the "triple effect," with true HILT as its most representative expression.

Building on this understanding, laser technology has evolved to include systems with increasingly complex pulse architectures and high peak powers, enabling biological effects that extend beyond traditional photochemistry and photothermal modulation.

Among these, High-Intensity Laser Therapy (HILT) emerged as a promising modality [

18,

19] that combines the penetration depth of HPLT with the metabolic benefits of LLLT. However, the term "HILT" is nowadays inconsistently applied. In many cases, devices classified as HILT lack the pulse characteristics needed to induce photoacoustic effects and behave instead as purely photothermal systems.

This inconsistency has critical implications. A device with high average power but no capability to generate high-peak, short pulses may induce only superficial heating, while a lower-power device capable of kilowatt-scale peaks may trigger genuine regenerative pathways. Current classifications often fail to reflect these nuances, leading to potential misinterpretation of clinical outcomes and confusion in scientific reporting.

This review does not question the efficacy of laser devices when used appropriately. Instead, it highlights taxonomic inconsistencies, particularly regarding HILT, that risk obscuring biological specificity. A mechanism-based classification will better align terminology with therapeutic action, benefiting research, device development, and clinical decision-making. The goal is not to rank the effectiveness of different laser devices or protocols, but rather to propose a biologically coherent framework that distinguishes laser systems based on their dominant mechanism of interaction with biological tissues. It is important to emphasize that all laser systems, whether classified as LLLT, HPLT or HILT, can produce beneficial biological effects when properly applied. Some devices primarily induce photochemical effects, others combine photochemical and photothermal mechanisms, while only a subset can also trigger photoacoustic effects. Each modality has therapeutic value within its intended application context.

The following sections delve into each light-tissue interaction mechanism, discuss misclassification issues in the literature, and propose a biologically coherent taxonomy for laser-based therapies.

To restrict the present review study, we mainly focused on dentistry. However, the findings can be easily translated to any other clinical application of HILT (e.g. sport medicine).

1.1. Biological Mechanisms of Laser-Tissue Interaction

1.1.1. Photochemical Effects: Mitochondrial Activation and Cellular Biostimulation

Photochemical mechanisms form the foundation of traditional Low-Level Laser Therapy (LLLT) and represent one of the principal modes of action in photobiomodulation (PBM). In this regime, low-power laser light, typically in the red or near-infrared spectrum (600–1,000 nm), is absorbed by intracellular chromophores, most notably Cytochrome C oxidase (COX), a key enzyme in the mitochondrial electron transport chain. This photon absorption enhances mitochondrial membrane potential, accelerates ATP synthesis, and modulates the production of nitric oxide (NO) and reactive oxygen species (ROS), thereby influencing key cellular pathways related to metabolism, inflammation, and proliferation (Karu [

4]).

A comprehensive review by Ohsugi et al. [

10] demonstrated that such photochemical stimulation promotes favorable biological responses across a range of oral-related cell types, including epithelial cells, fibroblasts, osteoblasts, osteoclasts, endothelial cells, and mesenchymal stem cells. In particular, laser settings in the range of 1–10 J/cm² were shown to significantly increase proliferation, wound closure, and the expression of genes linked to tissue repair and regeneration, such as ALP, Runx2, BMP-2, and TGF-β1. These effects were dose- and time-dependent, often peaking between 24 and 72 hours post-irradiation. However, the authors also noted that higher energy densities (>20 J/cm²) could lead to cytotoxic effects or oxidative stress, underscoring the importance of optimized dosimetry.

This dose-dependent response was further confirmed by Sleep et al. [

17], who used a multi-wavelength LED array (700, 850, and 980 nm) in osteoblast cultures. Moderate energy densities (5.3 J/cm²) effectively stimulated mitochondrial respiration and upregulated osteogenic genes such as RUNX2, COL-1, and BMP-2, while prolonged or repeated exposure to higher doses (10.6 J/cm²) led to a suppression of these beneficial effects. This biphasic behavior suggests that without additional biomechanical stimuli, excessive photonic energy may hinder rather than enhance therapeutic outcomes.

Photochemical PBM is also capable of modulating inflammatory processes by inducing antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD) and glutathione peroxidase, and by stimulating the production of growth factors like platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) and transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β). These mediators play a central role in fibroblast migration, collagen synthesis, wound healing, and inflammatory disease management such as periodontitis.

In the context of gene therapy, a systematic review by Hosseinpour et al. [

11] identified photochemical internalization as a critical enhancer of nucleic acid transfection. This mechanism involves the light-induced disruption of endosomal membranes, allowing nucleic acids to escape into the cytosol and reach their molecular targets. Although less efficient than photoacoustic methods, photochemical PBM still offers a favorable safety profile and non-invasive strategy for gene delivery and cellular reprogramming.

The depth of penetration for photochemical effects is limited (due to the optical absorption of the biological tissues), typically between 0.3 and 0.8 cm, making these interactions most suitable for superficial tissues or anatomically thin structures such as the oral mucosa, periodontal ligament, and small joints. Despite these limitations, the therapeutic scope of photochemical PBM spans soft tissue repair, chronic inflammation management, periodontal therapy, and regenerative medicine.

Taken together, these findings confirm that photochemical mechanisms, although limited in penetration depth, offer a powerful, mitochondria-mediated pathway for metabolic activation, tissue repair, and inflammation control. When carefully dosed, they provide a cornerstone for PBM applications, particularly in superficial and chronic conditions. However, when used in combination with photothermal and photoacoustic mechanisms, as in true HILT protocols, these effects can be further amplified to support deeper and more complex tissue regeneration.

1.1.2. Photothermal Effects: Heat-Induced Modulation of Tissue Physiology

Photothermal mechanisms involve the conversion of absorbed light into heat. Depending on energy delivery and tissue optical properties, temperature may rise by 2–6°C, promoting vasodilation, increased circulation, collagen remodeling, muscle relaxation, and transient inhibition of nerve conduction (Orchardson et al., [

20]; Zhang et al., [

21]; Cronshaw et al., [

22]). These effects are especially valuable in pain therapy, analgesia, dentinal hypersensitivity, myorelaxation, and rehabilitation. However, excessive thermal buildup may cause inflammation, protein denaturation, or delayed healing, particularly in the absence of appropriate pulse modulation or cooling.

Photothermal effects are generally produced by continuous-wave or quasi-continuous systems operating in the near-infrared range (800–1,064 nm) at power levels above 1 W. Cronshaw et al. [

22] demonstrated that among several wavelengths tested on porcine muscle, 980 nm light induced the highest thermal effect, particularly when applied statically or with Gaussian beam profiles. In contrast, scanning modes and flat-top applicators limited temperature rise, highlighting the relevance of beam geometry and movement technique in safe energy delivery.

From a molecular perspective, photothermal stimulation modulates inflammation through TRPV ion channels and heat shock proteins (HSPs), particularly HSP70 and HSP47. These proteins regulate stress responses, collagen folding, and immune signaling. HSP47 facilitates proper collagen assembly, while HSP70 enhances cell survival and tissue recovery. Zhang et al. [

21] further reported that photothermal effects stabilize the extracellular matrix and promote regeneration via the PI3K/AKT/mTOR and ERK/MAPK pathways.

Orchardson et al. [

20] showed that transient axonal depolarization induced by controlled heat could block peripheral nerve conduction, explaining the localized analgesic effect observed with high-intensity stimulation. This nerve modulation occurs without structural damage, offering a non-invasive modality for acute and chronic pain management.

Alayat et al. [

23] observed improved joint mobility and pain reduction in temporomandibular joint dysfunction following HILT, due to the combined vasodilatory and muscle-relaxant effects of photothermal PBM. Mild hyperthermia (≈39–43 °C) induces HSP-mediated activation of dendritic cells and macrophages, enhancing antigen presentation and downstream T-cell responses [

24].

Nevertheless, exceeding thermal thresholds (typically >45°C) can impair mitochondrial function, denature proteins, and cause tissue injury. Therefore, precise control over pulse duration, duty cycle, and total exposure is crucial to optimize therapeutic effects while avoiding adverse outcomes. HILT systems help achieve this balance through low duty cycles (0.05–1%) and long thermal relaxation intervals, allowing high peak powers without cumulative overheating.

Photothermal effects typically penetrate to depths of 1–1.5 cm depending on tissue composition and vascularization. Their utility spans from localized pain relief to enhancement of microcirculation, angiogenesis, and fascial release. While not sufficient alone for deep regenerative activation, their synergy with photochemical and photoacoustic stimuli in HILT contributes significantly to therapeutic success.

In summary, photothermal PBM offers a powerful but nuanced approach to tissue modulation. Its biological efficacy depends on fine-tuned parameters and appropriate delivery, reinforcing the need for accurate laser classification and personalized treatment planning.

1.1.3. Photoacoustic Effects: Mechanical Stimulation and Regenerative Signaling

A key distinction of HILT lies in its photoacoustic effects, where high-energy pulses generate acoustic pressure waves that propagate deep into tissues, activating mechano-transduction pathways critical for cellular function. Tarantino et al. [

12] demonstrated that these effects trigger the tyrosine kinase (TK) pathway, regulating cellular proliferation, extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling, and inflammation control. Remarkably, even when the TK pathway was pharmacologically inhibited, HILT restored cellular proliferation and reactivated anabolic processes, underscoring its capability to counteract degenerative conditions such as fibrosis and chronic inflammation.

Monici et al. [

13] and Cialdai et al. [

14] provided further insights into HILT-induced cytoskeletal remodeling, showing that pulsed Nd:YAG lasers reorganize microtubules and intermediate filaments while enhancing integrin-mediated ECM interactions. These changes optimize cellular adhesion, improve tissue resilience, and stimulate ECM synthesis. Research also confirms that photoacoustic stimulation significantly boosts collagen and glycosaminoglycan production, reinforcing tissue structural integrity.

Studies by Monici [

13], Cialdai [

14], Bosco [

25], Cheng [

26], De Cesari [

16] and Genchi [

15] have demonstrated that biological responses to mechanical forces emerge at pressures as low as 10 kPa (1G) but become significantly more pronounced at 100–800 kPa (10–80G). Notably, De Cesari et al. [

16] found that exposure to hypergravity conditions ≥4G (39.24 kPa) significantly enhances angiogenesis, cellular motility, and ECM remodeling, reinforcing the hypothesis that mechanical pressure influences multiple levels of tissue adaptation. Additionally, Genchi et al. [

15] demonstrated that extreme hypergravity levels (150G, 1,471.5 kPa) accelerate neurogenesis and neurite outgrowth, highlighting the critical role of pressure in neuronal differentiation.

Preclinical and clinical studies further validate these findings. Fortuna et al. [

18,

27] demonstrated significant cartilage regeneration and ECM organization improvements in models of osteoarthritis and in severe tendonitis of horses [

28], while Zati et al. [

29] confirmed these effects in human clinical trials, underscoring HILT’s potential as a non-invasive alternative for cartilage repair.

HILT photoacoustic effects also promote fibrocyte-to-fibroblast differentiation [

30,

31], a critical process in tissue repair. By activating mechano-transduction pathways, HILT enhances cellular metabolism and ECM deposition, ensuring that repaired tissues regain their original structural and functional properties. Notably, HILT-generated pressure waves exceed 10 kPa, a threshold necessary for activating cellular differentiation and mechano-transduction, with values ranging up to 800 kPa, similar to those observed in hyper gravity studies [

13,

14,

30,

31,

32,

33].

The ability of HILT to generate such mechanical waves depends on key parameters such as pulse energy, tissue absorption coefficients, and duty cycle. The most precise method for quantifying pressure wave generation is the Margheri [

32] equation, which offers a detailed analytical model for estimating pressure amplitude. However, due to its complexity, its use in clinical settings is limited. Earlier calculations by Fortuna and Masotti [

9] used the PIF model in aqueous media at 27°C to simulate

in vitro conditions. In contrast, as noted by Salomatina et al. [

33], biological tissues possess significantly higher absorption coefficients, suggesting that actual

in vivo pressure amplitudes are likely an order of magnitude greater—thus amplifying the mechanical stimuli delivered during clinical HILT treatments.

Because photoacoustic mechanisms operate independently of thermal accumulation, their effects can penetrate 3–5 cm into tissue, making them particularly advantageous for non-invasive interventions in orthopedics, dentistry, sports medicine, and soft tissue regeneration. This unique depth of action and mechano-transductive profile clearly distinguish photoacoustic stimulation from photochemical and photothermal effects, positioning it as a safe and potent mechanism within modern regenerative therapy.

1.2. Laser-Tissue Interaction Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications

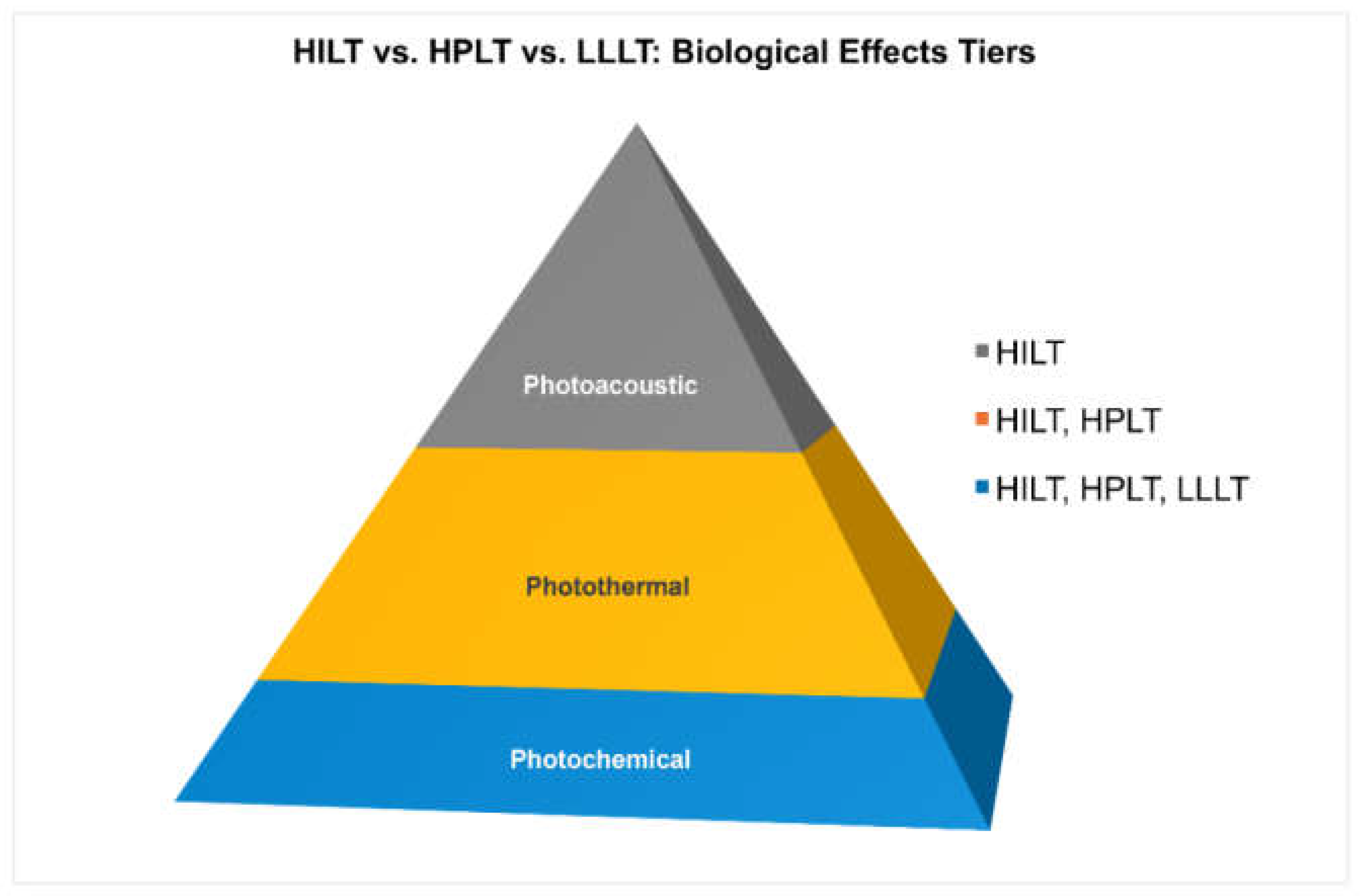

The three laser-tissue interaction mechanisms, i.e. the photochemical, photothermal, and photoacoustic ones, are not mutually exclusive. Rather, they can coexist and act synergistically depending on the specific laser parameters and device architecture.

Each mechanism has distinct biological effects and depth of penetration, but only systems capable of generating all three simultaneously, i.e., true High-Intensity Laser Therapy (HILT) devices, can activate what we define as the "triple effect".

This effect combines: metabolic stimulation via photochemistry (ATP, NO, ROS); tissue modulation via photothermal vasodilation and remodeling; mechanical regeneration via photoacoustic activation of mechano-transduction pathways.

Laser systems can thus be functionally classified as:

Single effect: Low-Level Laser Therapy (LLLT) → Photochemical only

Dual effect: High-Power Laser Therapy (HPLT) → Photochemical + Photothermal

Triple effect: High-Intensity Laser Therapy (HILT) → Photochemical + Photothermal + Photoacoustic

This comparative overview, summarized in the table below, underscores that the mean output power alone is not sufficient to define the biological outcomes of a laser system. Instead, pulse structure, including peak power, energy per pulse, pulse duration time, and pulse repetition frequency, is the principal determinant of the therapeutic action.

Table 1.

Photoacoustic stimulation, unique to true HILT, requires high-peak-power pulses despite low average power. (*) The "Mean Power" values for photoacoustic stimulation may appear low due to the very short pulse durations and low duty cycles. However, peak power often reaches kW levels, which is critical to generating therapeutic acoustic waves.

Table 1.

Photoacoustic stimulation, unique to true HILT, requires high-peak-power pulses despite low average power. (*) The "Mean Power" values for photoacoustic stimulation may appear low due to the very short pulse durations and low duty cycles. However, peak power often reaches kW levels, which is critical to generating therapeutic acoustic waves.

| Mechanism |

Trigger |

Primary Effect |

Depth [cm] |

Mean Power [W] |

Clinical Use |

| Photochemical |

Photon absorption (COX) |

ATP ↑, ROS/NO modulation |

0.3-0.8 |

0.5 |

LLLT, chronic wounds, neuropathies |

| Photothermal |

Heat conversion |

Perfusion ↑, collagen remodeling |

<1.5 |

<5 |

Pain relief, muscle relaxation |

| Photoacoustic |

Acoustic wave (kW pulse) |

Mechano-transduction, ECM remodeling |

<3 |

<10

[high peak power – kW] (*) |

HILT, TMJ, bone/cartilage regeneration |

2. Materials and Methods

This article is structured as a narrative, mechanism-focused review, aiming at clarifying the semantic ambiguity surrounding the term High-Intensity Laser Therapy (HILT).

Based on this rationale, we performed a targeted literature search on PubMed for the years 2010–2025 including only double-blind randomized controlled trials (DB-RCTs) that explicitly mention “High Intensity Laser Therapy” or “HILT” in the title or abstract. Reviews and meta-analyses were excluded. A total of 60 studies were selected for analysis.

For each study, we extracted available technical details on the laser system used: wavelength, source type, peak power, average power, emission mode, pulse duration, pulse energy, repetition rate, and duty cycle. When full specifications were not provided in the article, we referred to device manuals and manufacturer datasheets.

The studies were then analyzed based on whether the used laser system met the biophysical requirements to induce photoacoustic effects, defined as: (1) Peak intensity ≥ 5 kW/cm², (2) Pulse energy in the hundreds of mJ, (3) Pulse duration ≤ 200 μs, (4) Duty cycle preferably in the 0.05%–0.5% range and always below 1%. These thresholds are based on the original criteria proposed by Fortuna and Masotti [

9] and reflect the physical requirements for generating therapeutic photoacoustic waves capable of activating mechanosensitive cellular pathways. Due to the lack of consistent reporting in many of the studies, only partial data could be retrieved in several cases. Furthermore, it is important to note that technical specifications were not always fully disclosed in the reviewed studies. As a result, the classification presented in

Table 2 includes only those laser parameters (such as wavelength and duty cycle) that could be explicitly extracted from the publications or reasonably inferred from the manufacturer’s documentation. The summary table in the following section reports only those parameters that could be verified from either the article or official technical documentation. This methodological limitation highlights a broader issue in Laser Therapy research: the urgent need for standardized and transparent reporting of laser characteristics, especially when classifying systems under specific therapeutic labels such as HILT.

3. Results

A total of 60 clinical studies published between 2010 and 2025 and referring explicitly to High-Intensity Laser Therapy (HILT) were identified and included in this analysis. All studies were focused on therapeutic applications of HILT and excluded reviews or meta-analyses. Among them, 38 were designed as double-blind and/or randomized trials, while 22 adopted alternative designs.

From a technological perspective, only 26 studies (43.3%) employed solid-state Nd:YAG laser systems, which, according to the parameters defined in our Materials and Methods section, are capable of delivering high-peak power density (≥5 kW/cm²), short-duration (<200 μs) pulses with duty cycles below 1%, often in the 0.05–0.5% range. These characteristics are essential for generating a significant photoacoustic effect, the key mechanism distinguishing true HILT from other photo-induced biomodulation modalities.

Conversely, the remaining 34 studies (56.7%) utilized gallium-arsenide (GaAs) diode lasers, most commonly emitting at 1064 nm, the same wavelength used in Nd:YAG systems. Despite their capability to produce high average powers, these diode devices typically operate in continuous wave (CW) mode or at very high duty cycles (e.g., ~25%) and lack the pulsing architecture needed to achieve optoacoustic stimulation. These systems are well suited to inducing photochemical and photothermal effects, but their capacity to generate significant photoacoustic responses remains questionable or unverified.

Table 2.

Summary of selected clinical studies labeled as HILT, detailing laser source, wavelength, emission mode, duty cycle, and study design.

Table 2.

Summary of selected clinical studies labeled as HILT, detailing laser source, wavelength, emission mode, duty cycle, and study design.

| |

Duty C34. |

|

| Ref. # |

Author |

Source |

Wavelength [nm] |

Biostimulation |

Analgesic |

Double Blind / Randomized |

| [34] |

Abdelbasset et al. 2020 |

GaAs |

1064 |

CW |

25 % (±20 %) |

Yes |

| [35] |

Abdelbasset et al. 2021 |

Nd:YAG |

1064 |

0.05-0.6% |

0.05-0.6% |

No |

| [36] |

Abdelhakiem NM, et al., 2024 |

GaAs |

1064 |

CW |

25 % (±20 %) |

Yes |

| [37] |

Abo Elyazed, et al., 2023 |

Nd:YAG |

1064 |

0.05-0.6% |

0.05-0.6% |

Yes |

| [38] |

Akaltun et al., 2021 |

GaAs |

1064 |

CW |

25 % (±20 %) |

Yes |

| [39] |

Akkurt et al. 2016 |

GaAs |

1064 |

CW |

25 % (±20 %) |

No |

| [40] |

Alayat et al. 2016 |

Nd:YAG |

1064 |

0.05-0.6% |

0.05-0.6% |

Yes |

| [41] |

Alayat et al. 2017 |

Nd:YAG |

1065 |

0.05-0.6% |

0.05-0.6% |

Yes |

| [42] |

Alkaltun et al. 2021 |

GaAs |

1064 |

CW |

25 % (±20 %) |

Yes |

| [43] |

Angelova et al., 2016 |

GaAs |

1064 |

CW |

25 % (±20 %) |

No |

| [44] |

Atan et al. 2021 |

GaAs |

1064 |

CW |

25 % (±20 %) |

Yes |

| [45] |

Bayburt et al., 2025 |

GaAs |

1064 |

CW |

25 % (±20 %) |

No |

| [46] |

Boyraz I., et al., 2015 |

GaAs |

1064 |

ND |

ND |

No |

| [47] |

Casale R., et al., 2012 |

Nd:YAG/Diode |

1064/830 |

ND |

ND |

No |

| [48] |

Chen et al. 2018 |

GaAs |

1064 |

CW |

25 % (±20 %) |

Yes |

| [49] |

Dundar et al., 2015 |

Nd:YAG |

1064 |

0.05-0.6% |

0.05-0.6% |

Yes |

| [50] |

Dundar et al., 2015 |

Nd:YAG |

1064 |

0.05-0.6% |

0.05-0.6% |

Yes |

| [51] |

Ebid et al., 2015 |

Nd:YAG |

1064 |

0.05-0.6% |

0.05-0.6% |

Yes |

| [52] |

Ebid et al., 2017 |

Nd:YAG |

1064 |

0.05-0.6% |

0.05-0.6% |

Yes |

| [53] |

Ekici et al., 2022 |

Nd:YAG |

1064 |

0.05-0.6% |

0.05-0.6% |

Yes |

| [54] |

Ekici et al., 2023 |

Nd:YAG |

1064 |

0.05-0.6% |

0.05-0.6% |

Yes |

| [55] |

El-Shamy et al. 2018 |

Nd:YAG |

1064 |

0.05-0.6% |

0.05-0.6% |

No |

| [56] |

Ezzati et al., 2020 |

GaAs |

808 |

ND |

ND |

No |

| [57] |

Ezzati et al., 2024 |

GaAs |

808 |

ND |

ND |

Yes |

| [58] |

Fiore et al., 2011 |

Nd:YAG |

1064 |

0.05-0.6% |

0.05-0.6% |

Yes |

| [59] |

Gocewska et al., 2019 |

GaAs |

940 |

ND |

ND |

No |

| [60] |

Haładaj et al., 2017 |

GaAs |

1064 |

CW |

25 % (±20 %) |

Yes |

| [61] |

Hamed et al., 2023 |

Nd:YAG |

1064 |

0.05-0.6% |

0.05-0.6% |

Yes |

| [62] |

Ince S. et al., 2024 |

Nd:YAG |

1064 |

0.05-0.6% |

0.05-0.6% |

Yes |

| [63] |

Ismail Boyraz et al., 2015 |

GaAs |

1064 |

ND |

ND |

No |

| [64] |

Karakuzu Güngör Z, 2025 |

GaAs |

1064 |

CW |

25 % (±20 %) |

No |

| [65] |

Kaydok et al., 2019 |

GaAs |

1064 |

CW |

25 % (±20 %) |

Yes |

| [66] |

Kheshie et al., 2014 |

Nd:YAG |

1064 |

0.05-0.6% |

0.05-0.6% |

Yes |

| [67] |

Kim GJ et al., 2016 |

GaAs |

980 |

CW |

ND |

No |

| [68] |

Kolu et al., 2018 |

GaAs |

1064 |

CW |

25 % (±20 %) |

Yes |

| [69] |

Kulchitskaya et al., 2017 |

GaAs |

1064 |

CW |

25 % (±20 %) |

No |

| [70] |

Lu Q, et al. , 2021 |

GaAs |

1064 |

CW |

25 % (±20 %) |

Yes |

| [71] |

Naruseviciute et al., 2020 |

GaAs |

1064 |

CW |

25 % (±20 %) |

Yes |

| [72] |

Nazari et al. 2019 |

GaAs |

1064 |

Pulsed |

duty cycle of 70% |

Yes |

| [73] |

Ordahan et al. 2018 |

GaAs |

1064 |

CW |

25 % (±20 %) |

Yes |

| [74] |

Ordahan et al. 2023 |

GaAs |

1064 |

CW |

25 % (±20 %) |

Yes |

| [75] |

Ozge Ozlu et al., 2024 |

Nd:YAG |

1064 |

25Hz |

ND |

Yes |

| [76] |

Paulina Zielińska et al., 2022 |

InGaAs / AlGaAs |

808/980 |

ND |

ND |

No |

| [77] |

Pekyavas et al., 2016 |

Nd:YAG |

1064 |

0.05-0.6% |

0.05-0.6% |

No |

| [78] |

Rahimi et al., 2024 |

GaAs |

1064 |

CW |

25 % (±20 %) |

Yes |

| [79] |

Saleh et al., 2024 |

Nd:YAG |

1064 |

0.05-0.6% |

0.05-0.6% |

No |

| [80] |

Salli et al. 2016 |

GaAs |

1064 |

0.05-0.6% |

0.05-0.6% |

No |

| [81] |

Santamato et al., 2009 |

Nd:YAG |

1064 |

0.05-0.6% |

0.05-0.6% |

Yes |

| [82] |

Siriratna P. et al., 2022 |

GaAs |

808/905 |

50% |

50% |

Yes |

| [83] |

Sudiyono & Handoyo, 2020 |

GaAs |

1064 |

CW |

25 % (±20 %) |

No |

| [84] |

Tache-Codreanu et al. 2024 |

GaAs |

1064 |

CW |

25 % (±20 %) |

No |

| [85] |

Thabet et al., 2017 |

Nd:YAG |

1064 |

0.05-0.6% |

0.05-0.6% |

No |

| [86] |

Thabet et al., 2018 |

Nd:YAG |

1064 |

0.05-0.6% |

0.05-0.6% |

No |

| [87] |

Tkocz P, et al., 2021 |

GaAs |

1064 |

ND |

90% |

Yes |

| [88] |

Venosa et al., 2018 |

Nd:YAG |

1064 |

0.05-0.6% |

0.05-0.6% |

Yes |

| [89] |

Viliani T, et al., 2012 |

Nd:YAG |

1064 |

0.05-0.6% |

0.05-0.6% |

No |

| [90] |

Yesil et al., 2020 |

Nd:YAG |

1064 |

0.05-0.6% |

0.05-0.6% |

Yes |

| [91] |

Yilmaz at al., 2020 |

GaAs |

1064 |

CW |

25 % (±20 %) |

Yes |

| [92] |

Yilmaz at al., 2022 |

Nd:YAG |

1064 |

0.05-0.6% |

0.05-0.6% |

Yes |

| [93] |

Zare Bidoki M. et al., 2024 |

GaAs |

980 |

ND |

ND |

Yes |

4. Discussion

The results of this review reveal a profound inconsistency in how the term "High-Intensity Laser Therapy" (HILT) is used across clinical studies. Out of 60 analyzed trials, only 43% utilized laser systems whose parameters aligned with the biophysical thresholds required to produce photoacoustic stimulation, namely, high-peak-power, short-duration pulses delivered at low duty cycles. The remaining 57% of studies employed devices that, while potentially effective for photochemical and photothermal stimulation, lacked the structural prerequisites for generating optoacoustic pressure waves. These findings indicate that the label HILT is often applied based solely on nominal output power or manufacturer designation, rather than on measurable interaction mechanisms.

The implications of this finding are twofold: (1) a significant proportion of studies labeled as “HILT” in the literature have likely evaluated therapies based only on dual effects (photochemical + photothermal), rather than the triple effect which defines true High-Intensity Laser Therapy; (2) the current terminological inconsistency in classifying therapeutic lasers may introduce interpretative bias in clinical trials, especially when devices with fundamentally different mechanisms of action are grouped under the same label.

This misalignment has significant implications. Clinically, it may lead practitioners to overestimate the regenerative capabilities of certain devices, especially when deeper tissue effects are expected. Scientifically, it compromises the comparability of studies and reduces the interpretability of meta-analyses, particularly when devices with distinct mechanisms of action are grouped under the same terms.

The core of the issue lies in a power-based classification model that prioritizes average output power, neglecting pulse structure, particularly peak power, pulse energy, repetition frequency, and duty cycle. These parameters are crucial because they determine not only the quantity of energy delivered but also how it interacts with biological tissues. Specifically, only laser systems capable of delivering brief, high-intensity energy bursts can generate photoacoustic pressure waves, a phenomenon governed by thermoelastic expansion and following the laws of acoustics.

Unlike light or heat, acoustic pressure waves propagate rapidly and deeply through tissues, several centimeters beyond the absorption limit of photons or the dissipation range of thermal gradients. This property is well-known in the clinical practice, particularly in ultrasound therapies. In HILT, the ability to mimic this dynamic through light-induced acoustic waves represents a biophysical breakthrough with direct implications for mechano-transduction, cellular differentiation, and extracellular matrix remodeling.

Despite the importance of these mechanisms, many published studies fail to report basic technical details. Parameters such as fluence are frequently reported without explicit definition, leaving ambiguity as to whether they refer to average power over time and area, or to pulse energy normalized to spot size. Similarly, device descriptions are frequently imprecise or even contradictory, for example, referencing “Nd:YAG diode lasers” or “semiconductive neodymium sources,” when the same manufacturers identify these systems as near-infrared diode emitters. Such terminological ambiguities make it impossible to assess the true mode of action and invalidate comparisons across studies.

Other publications refer vaguely to “intensity level 2” or “frequency 11 Hz” without specifying peak power, pulse duration, or pulse energy. Worse, some devices classified as HILT are reported as using diode sources emitting in cw mode, with duty cycles exceeding 20–50%, far outside the range necessary to produce photoacoustic effects. In these cases, HILT is used as a marketing label rather than a scientific category, a practice that misleads clinicians, confuses readers, and undermines the validity of systematic reviews. While all the cited devices may induce beneficial biological responses, this review aims to clarify semantic confusion and promote a more mechanism-based classification, rather than judging one laser as superior to another on in its clinical effects. Every system can be effective when used correctly and appropriately, but different mechanisms require different terminology. This section avoids citing specific studies and instead focuses on general trends observed in literature. The aim is not to discredit the clinical results achieved, but to emphasize that inadequate or inconsistent reporting of technical parameters hampers scientific clarity and leads to semantic inflation. Much of this confusion appears to stem not from negligence, but from commercial influence and an underestimation of the biophysical complexity involved.

It is also noteworthy that some devices classified as HILT by authors or manufacturers are, upon closer inspection, diode lasers operating in continuous wave or quasi-continuous modes with high duty cycles, structures that inherently prevent the generation of true photoacoustic effects. Without pulsed emission in the kilowatt range and sub-millisecond durations, the capacity to induce mechano-transduction remains unsupported.

To address this confusion, we propose a mechanism-based taxonomy that classifies laser therapies by their predominant biological effects:

Photochemical PBM (LLLT) → Mitochondrial activation and redox modulation via low-power continuous or long-pulse emission.

Photothermal (HPLT) → Heat-induced vasodilation, collagen remodeling, and analgesia via high average power.

Photoacoustic (true HILT) → Mechano-transductive stimulation via short, high-peak-power pulses generating acoustic pressure waves.

In addition to these, a complete and transparent description of the protocol should also include: the diameter of the laser spot on tissue (in centimeters), the pulse repetition frequency (in Hertz), and the total treatment duration (in seconds or minutes). These additional values are not only helpful for replication purposes but also provide essential context for dosimetry analysis. The photochemical PBM steps modulates mitochondrial redox chains and raises ATP, priming cell metabolism for repair. Within micro- to milliseconds, thermoelastic expansion of the illuminated volume launches an acoustic pressure wave. This photoacoustic component travels several centimeters through tissue, mechanically exciting the cytoskeleton and focal adhesions and thereby driving mechanotransduction that promotes protein and extracellular-matrix synthesis—even when kinase signaling is blunted by chronic inflammation [

12]. The same physics explains rapid nerve-function modulation and analgesia through transient conduction block [

20]. Finally, across pulse trains, residual heat accumulates locally and more shallowly than the acoustic wave, producing photothermal effects—vasodilation, lymphatic drainage, and muscle relaxation—that improve perfusion and pain control; among near-infrared wavelengths, static 980-nm delivery produces the greatest local temperature rise, whereas scanning/flat-top beams limit it [

22].

This tripartite classification offers a biologically coherent and clinically meaningful framework. While all laser modalities can induce beneficial effects when properly applied, only systems capable of producing all three mechanisms—the “triple effect”—can fully support regenerative processes that depend on mechanical signaling.

Figure 1.

Biological effects of therapeutic lasers illustrated as a pyramid. The basal photochemical layer is shared by LLLT, HPLT, and HILT; the intermediate photothermal layer characterizes HPLT and HILT; the apical photoacoustic layer is unique to HILT. LLLT mainly produces the photochemical step; HPLT adds photothermal heating; only true HILT—with high-peak-power, short pulses at low duty cycle—co-delivers all three mechanisms concurrently and synergistically in each treatment sequence: photochemical (first & superficial) → photoacoustic (fast & deep) → photothermal (later & local). This tri-modal, co-temporal action is what distinguishes HILT biologically and clinically.

Figure 1.

Biological effects of therapeutic lasers illustrated as a pyramid. The basal photochemical layer is shared by LLLT, HPLT, and HILT; the intermediate photothermal layer characterizes HPLT and HILT; the apical photoacoustic layer is unique to HILT. LLLT mainly produces the photochemical step; HPLT adds photothermal heating; only true HILT—with high-peak-power, short pulses at low duty cycle—co-delivers all three mechanisms concurrently and synergistically in each treatment sequence: photochemical (first & superficial) → photoacoustic (fast & deep) → photothermal (later & local). This tri-modal, co-temporal action is what distinguishes HILT biologically and clinically.

5. Conclusions

Laser Therapy is a field with well-documented effects on cellular metabolism, inflammation, and tissue repair. However, as the field matures, it becomes increasingly evident that the current classification of therapeutic lasers, still largely based on nominal power output, fails to reflect the complexity of their biological effects. In particular, the term High-Intensity Laser Therapy (HILT) is frequently misapplied to systems lacking the temporal architecture required to induce photoacoustic stimulation, the hallmark mechanism that distinguishes true HILT from other modalities.

Biophysically, the defining factor of a laser’s therapeutic mechanism is not average power, but rather pulse structure, including peak power, pulse energy, duty cycle, and repetition frequency. Only devices capable of delivering short, high-peak-power pulses at low duty cycles can generate the acoustic pressure waves necessary to activate mechanosensitive pathways involved in long-term tissue regeneration. Without these features, a device may still be effective through photochemical or photothermal effects, but it should not be classified as HILT.

To restore clarity, we propose a revised classification based on the dominant biological mechanism of action:

1. Photochemical effects → mitochondrial and metabolic stimulation (PBM or LLLT)

2. Photothermal effects → temperature-mediated modulation (commonly HPLT)

3. Photoacoustic effects → regeneration via acoustic pressure wave, induced mechano-transduction (true HILT)

This mechanism-based taxonomy provides a biologically coherent foundation for both clinical and research applications. It enables more accurate interpretation of results, supports better clinical decision-making, and avoids conflating technologies with divergent modes of action.

To ensure accurate classification, reproducibility, and meaningful comparison across clinical studies, a standardized set of laser parameters should always be reported. These include laser source (e.g., Nd:YAG, GaAs), wavelength, emission mode (CW or pulsed), average and peak power, duty cycle, pulse duration, and frequency. Reported values must reflect the actual settings used during treatment, not the maximum specifications listed by the manufacturer. Only through such rigorous and transparent reporting can we advance toward a mechanism-based classification of therapeutic lasers and avoid interpretative bias in clinical research. Journals, reviewers, and regulatory bodies should consider mandating this minimal data set as a prerequisite for publication.

Our findings do not question the efficacy of existing laser therapies but highlight the urgent need for a more precise and biologically grounded classification model. The term HILT should be reserved for systems capable of photoacoustic stimulation, not simply those exceeding arbitrary power thresholds.

Clarifying this distinction is essential to distinguishing true photobiomodulation (i.e., photochemical effects) from other laser-based therapies, namely, those based on photothermal and photoacoustic effects, and to ensure that clinical use is guided by biological mechanisms rather than marketing.

Future research should aim to define quantitative thresholds for photoacoustic stimulation and develop validated metrics to characterize treatment protocols. By establishing a common language rooted in biology and physics, this work aims to support a more rigorous, effective, and transparent use of laser therapy in regenerative medicine.

Supplementary Materials

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.F. and F.R.; Methodology, D.F.; Investigation, D.F.; Data Curation, D.F.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, D.F.; Writing—Review & Editing, D.F., F.M., S.P. and F.R.; Visualization, D.F.; Supervision, F.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank El.En. S.p.A. (Florence, Italy), DEKA Dental Lasers (Nashville, TN, USA), and the Institute of Applied Physics (CNR-IFAC, Florence, Italy) for scientific discussions and support.

Conflicts of Interest

Fabrizio Margheri is employed in the R&D department of El.En. Group (Florence, Italy), a manufacturer of HILT lasers. Other manufacturers of HILT devices are also active worldwide.Scott Parker is employed as VP of Clinical Affairs at DEKA Dental Lasers (Nashville, TN, USA), a company that markets HILT devices in dentistry.Damiano Fortuna acts as an external consultant for DEKA Dental Lasers (Nashville, TN, USA).The authors declare that these affiliations did not influence the design, analysis, or interpretation of the review.

References

- Mester, E.; Szende, B.; Gärtner, P. The effect of laser beams on the growth of hair in mice. Radiobiol. Radiother. (Berl.) 1968, 9, 621–626.

- McGuff, P.E.; Deterling, R.A.; Gottlieb, L.S. Tumoricidal effect of laser energy on experimental and human malignant tumors. N. Engl. J. Med. 1965, 273, 490–492. [CrossRef]

- Mester, A.; Mester, A. The History of Photobiomodulation: Endre Mester (1903–1984). Photomed. Laser Surg. 2017, 35, 393–394. [CrossRef]

- Karu, T. Photobiology of low-power laser effects. Health Phys. 1989, 56, 691–704. [CrossRef]

- Chow, R.T.; Johnson, M.I.; Lopes-Martins, R.A.; Bjordal, J.M. Efficacy of low-level laser therapy in the management of neck pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised placebo or active-treatment controlled trials. Lancet 2009, 374, 1897–1908. [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, J.T.; McLoda, T.A.; Seegmiller, J.G.; Baxter, G.D. Low-Level Laser Therapy Facilitates Superficial Wound Healing in Humans: A Triple-Blind, Sham-Controlled Study. J. Athl. Train. 2004, 39, 223–229.

- Turner, J.; Hode, L. The Laser Therapy Handbook; Prima Books: Grängesberg, Sweden, 2004.

- Mårdh, A.; Lund, I. High power laser for treatment of Achilles tendinosis—A single blind randomized placebo controlled clinical study. J. Lasers Med. Sci. 2016, 7, 92–98. [CrossRef]

- Fortuna, D.; Masotti, L. The HILT domain by the pulse intensity fluence (PIF) formula. Energy Health 2010, 5, 12–19.

- Ohsugi, Y.; Niimi, H.; Shimohira, T.; et al. In Vitro Cytological Responses against Laser Photobiomodulation for Periodontal Regeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9002. [CrossRef]

- Hosseinpour, S.; Walsh, L.J. Laser-assisted nucleic acid delivery: A systematic review. J. Biophotonics 2021, 14, e202000295. [CrossRef]

- Tarantino, C.; Rossi, G.; Flamini, G.; Fortuna, D. Cytoproliferative activity of the HILT: In vitro survey. Lasers Med. Sci. 2002, 17, A22.

- Monici, M.; Cialdai, F.; Fusi, F.; Romano, G.; Pratesi, R. Effects of pulsed Nd:YAG laser at molecular and cellular level—A study on the basis of Hilterapia®. Energy Health 2009, 3, 26–33.

- Cialdai, F.; Monici, M. Relationship between cellular and systemic effects of pulsed Nd:YAG laser. Energy Health 2010, 5, 4–9.

- Genchi, G.G.; Cialdai, F.; Monici, M.; et al. Hypergravity stimulation enhances PC12 neuron-like cell differentiation. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 748121. [CrossRef]

- De Cesari, C.; Barravecchia, I.; Pyankova, O.V.; et al. Hypergravity Activates a Pro-Angiogenic Homeostatic Response by Human Capillary Endothelial Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2354. [CrossRef]

- Sleep, S.; Hryciw, D.H.; Walsh, L.J.; et al. Effects of Multiple Near-Infrared LEDs (700, 850, and 980 nm) CW-PBM on Mitochondrial Respiration and Gene Expression in MG63 Osteoblasts. J. Biophotonics 2025, e70015. [CrossRef]

- Fortuna, D.; Rossi, G.; Zati, A.; et al. High Intensity Laser Therapy in experimentally induced chronic degenerative tenosynovitis in heavyline chicken broiler. Proc. SPIE 2002, 4903, 85–91.

- [19] Zati, A.; Fortuna, D.; Valent, A.; Filippi, M.V.; Bilotta, T.W. High Intensity Laser Therapy (HILT) versus TENS and NSAIDs in low back pain: Clinical study. Proc. SPIE 2004, 5610, 277–283.

- [20] Orchardson, R.; Peacock, J.M.; Whitters, C.J. Effect of pulsed Nd:YAG laser radiation on action potential conduction in isolated mammalian spinal nerves. Lasers Surg. Med. 1997, 21, 142–148. [CrossRef]

- [21] Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, P.; et al. The Role of Photobiomodulation to Modulate Ion Channels in the Nervous System: A Systematic Review. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2024, 44, 79. [CrossRef]

- [22] Cronshaw, M.; Parker, S.; Grootveld, M.; Lynch, E. Photothermal Effects of High-Energy Photobiomodulation Therapies: An In Vitro Investigation. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1634. [CrossRef]

- [23] Alayat, M.S.; Battecha, K.H.; Elsodany, A.M.; Ali, M.I. Pulsed Nd:YAG laser combined with progressive pressure release in cervical myofascial pain syndrome: A randomized control trial. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2020, 32, 422–427.

- [24] Lee, S.; Son, B.; Park, G.; Kim, H.; Kang, H.; Jeon, J.; Youn, H.; Youn, B. Immunogenic Effect of Hyperthermia on Enhancing Radiotherapeutic Efficacy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2795. [CrossRef]

- [25] Bosco, C. Adaptive response of human skeletal muscle to simulated hypergravity condition. Acta Physiol. Scand. 1985, 124, 507–513.

- [26] Cheng, G.; Yu, B.; Song, C.; Zablotskii, V.; Zhang, X. Bioeffects of Microgravity and Hypergravity on Animals. Chin. J. Electr. Eng. 2023, 9, 29–46. [CrossRef]

- [27] Fortuna, D.; Rossi, G.; Zati, A.; et al. Nd:YAG laser in experimentally induced chronic degenerative osteoarthritis in heavyline chicken broiler—Pilot study. Proc. SPIE 2002, 4903, 77–84.

- [28] Fortuna, D.; Rossi, G.; Paolini, C.; et al. Nd:YAG pulsed wave laser as support therapy in teno-desmopathies of athlete horses: Clinical and experimental trial. Proc. SPIE 2002, 4903, 105–118.

- [29] Zati, A.; Desando, G.; Cavallo, C.; et al. Treatment of human cartilage defects by means of Nd:YAG Laser Therapy. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2012, 26, 701–711.

- [30] Bucala, R.; Spiegel, L.A.; Chesney, J.; Hogan, M.; Cerami, A. Circulating fibrocytes define a new leukocyte subpopulation that mediates tissue repair. Mol. Med. 1994, 1, 71–81.

- [31] Andersson-Sjöland, A.; Nihlberg, K.; Eriksson, L.; et al. Fibrocytes and the tissue niche in lung repair. Respir. Res. 2011, 12, 76. [CrossRef]

- [32] Margheri, F. Sviluppo di trasduttori acusto-ottici miniaturizzati per diagnostica clinica e controlli non distruttivi. Ph.D. Thesis, Università degli Studi di Firenze, Florence, Italy, 2000.

- [33] Salomatina, E.; Jiang, B.; Novak, J.; Yaroslavsky, A.N. Optical properties of normal and cancerous human skin in the visible and near-infrared spectral range. J. Biomed. Opt. 2006, 11, 064026. [CrossRef]

- [34] Abdelbasset, W.K.; Nambi, G.; Alsubaie, S.F.; et al. A randomized comparative study between high-intensity and low-level laser therapy in chronic nonspecific low back pain. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2020, 2020, 1350281. [CrossRef]

- [35] Abdelbasset, W.K.; Nambi, G.; Elsayed, S.H.; et al. Pulsed HILT vs pulsed electromagnetic field in chronic nonspecific low back pain. Photobiomodul. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2021, 39, 362–368. [CrossRef]

- [36] Abdelhakiem, N.M.; Mustafa Saleh, M.S.; Shabana, M.M.A.; Abd El Wahaab, H.A.; Saleh, H.M. Effectiveness of a high-intensity laser for improving hemiplegic shoulder dysfunction: Randomized controlled trial. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 7346. [CrossRef]

- [37] Abo Elyazed, T.I.; Al-Azab, I.M.; Abd El-Hakim, A.A.E.; et al. HILT vs shockwave therapy in osteoporotic long-term hemiparetic patients: Randomized controlled trial. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2023, 18, 653. [CrossRef]

- [38] Akaltun, M.S.; Altindag, O.; Turan, N.; Gursoy, S.; Gur, A. HILT in knee osteoarthritis: Double-blind randomized study. Clin. Rheumatol. 2021, 40, 1989–1995. [CrossRef]

- [39] Akkurt, E.; Kucuksen, S.; Yılmaz, H.; Parlak, S.; Sallı, A.; Karaca, G. Long-term effects of HILT in lateral epicondylitis patients. Lasers Med. Sci. 2016, —.

- [40] Alayat, M.S.; Mohamed, A.A.; Helal, O.F.; Khaled, O.A. HILT for chronic neck pain: Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Lasers Med. Sci. 2016, 31, 687–694. [CrossRef]

- [41] Alayat, M.S.M.; Abdel-Kafy, E.M.; Elsoudany, A.M.; Helal, O.F.; Alshehri, M.A. HILT in males with osteopenia/osteoporosis: Randomized placebo-controlled trial. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2017, 29, 1675–1679.

- [42] Akaltun, M.S.; Altindag, O.; Turan, N.; Gursoy, S.; Gur, A. HILT in knee osteoarthritis: Double-blind randomized study. Clin. Rheumatol. 2021, 40, 1989–1995. [CrossRef]

- [43] Angelova, A.; Ilieva, E.M. Effectiveness of HILT for pain reduction in knee osteoarthritis. Pain Res. Manag. 2016, 2016, 9163618. [CrossRef]

- [44] Atan, T.; Bahar-Ozdemir, Y. HILT in adhesive capsulitis: Sham-controlled randomized trial. Lasers Med. Sci. 2021, 36, 207–217. [CrossRef]

- [45] Bayburt, K.A.; Diker, N.; Aydin, M.S.; Dolanmaz, D. HILT vs PBM on sciatic nerve regeneration (animal). Lasers Med. Sci. 2025, 40, 81. [CrossRef]

- [46] Boyraz, I.; Yildiz, A.; Koc, B.; Sarman, H. HILT vs ultrasound in lumbar discopathy. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 304328. [CrossRef]

- [47] Casale, R.; Damiani, C.; Maestri, R.; Wells, C.D. 830–1064 nm HILT vs TENS in carpal tunnel syndrome: Randomized controlled study. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2013, 49, 205–211.

- [48] Chen, L.; Liu, D.; Zou, L.; et al. HILT for lumbar disc protrusion: Randomized trial. J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 2018, 31, 191–196. [CrossRef]

- [49] Dundar, U.; Turkmen, U.; Toktas, H.; Ulasli, A.M.; Solak, O. HILT and splinting in lateral epicondylitis: Prospective RCT. Lasers Med. Sci. 2015, 30, 1097–1107. [CrossRef]

- [50] Dundar, U.; Turkmen, U.; Toktas, H.; Solak, O.; Ulasli, A.M. HILT in myofascial pain syndrome of the trapezius: Double-blind placebo-controlled study. Lasers Med. Sci. 2015, 30, 325–332. [CrossRef]

- [51] Ebid, A.A.; El-Sodany, A.M. Long-term pulsed HILT in post-mastectomy pain: Double-blind randomized study. Lasers Med. Sci. 2015, 30, 1747–1755. [CrossRef]

- [52] Ebid, A.A.; Ibrahim, A.R.; Omar, M.T.; El Baky, A.M.A. Long-term pulsed HILT in post-burn pruritus: Double-blind randomized study. Lasers Med. Sci. 2017, 32, 693–701. [CrossRef]

- [53] Ekici, Ö.; Dündar, Ü.; Büyükbosna, M. HILT in myogenic temporomandibular disorder: Double-blind placebo-controlled study. J. Stomatol. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2022, 123, e90–e96. [CrossRef]

- [54] Ekici, B.; Ordahan, B. HILT in knee osteoarthritis: Randomized study. Lasers Med. Sci. 2023, 38, 218. [CrossRef]

- [55] El-Shamy, S.M.; Abdelaal, A.A.M. Pulsed HILT in children with haemophilic arthropathy. Disabil. Rehabil. 2018, 40, 462–468. [CrossRef]

- [56] Ezzati, K.; Laakso, E.L.; Saberi, A.; et al. Dose-dependent effects of LLLT vs HILT in carpal tunnel syndrome. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2020, 56, 733–740. [CrossRef]

- [57] Ezzati, K.; Esmaili, K.; Reihanian, Z.; et al. HILT vs LLLT in knee osteoarthritis: Single-blinded RCT. J. Lasers Med. Sci. 2024, 15, e66. [CrossRef]

- [58] Fiore, P.; Panza, F.; Cassatella, G.; et al. HILT vs ultrasound in low back pain: Randomized trial. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2011, 47, 367–373.

- [59] Gocevska, M.; Nikolikj-Dimitrova, E.; Gjerakaroska-Savevska, C. High-intensity laser in chronic low back pain: Randomized trial. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2019, 7, 949–954. [CrossRef]

- [60] Haładaj, R.; Pingot, M.; Topol, M. Saunders traction device plus HILT for cervical spondylosis: Randomized trial. Med. Sci. Monit. 2017, 23, 335–342. [CrossRef]

- [61] Hamed, S.M.; Ahmed, Y.F.; Ghuiba, K.; Ibrahim, K.S.; Hassan, E.J. High- vs low-intensity laser in lateral epicondylitis: Randomized trial. Eur. Chem. Bull. 2023, 12(S3), 593–604.

- [62] İnce, S.; Eyvaz, N.; Dündar, Ü.; et al. HILT in cervical radiculopathy: 12-week randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2024, 103, 3–12. [CrossRef]

- [63] Boyraz, I.; Yildiz, A.; Koc, B.; Sarman, H. Comparison of HILT and ultrasound in lumbar discopathy. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 304328. [CrossRef]

- [64] Karakuzu Güngör, Z. ESWT vs HILT for calcaneal spur: Clinical outcomes. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2025, 20, 393. [CrossRef]

- [65] Kaydok, E.; Ordahan, B.; Solum, S.; Karahan, A.Y. High- vs low-intensity laser in lateral epicondylitis: Double-blind RCT. Arch. Rheumatol. 2019, 35, 60–67. [CrossRef]

- [66] Kheshie, A.R.; Alayat, M.S.; Ali, M.M. High-intensity vs low-level laser therapy in knee osteoarthritis: Randomized controlled trial. Lasers Med. Sci. 2014, 29, 1371–1376. [CrossRef]

- [67] Kim, G.J.; Choi, J.; Lee, S.; Jeon, C.; Lee, K. Effects of HILT on pain and function in knee osteoarthritis. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2016, 28, 3197–3199. [CrossRef]

- [68] Kolu, E.; Buyukavci, R.; Akturk, S.; Eren, F.; Ersoy, Y. HILT vs TENS+ultrasound in chronic lumbar radiculopathy: Single-blind RCT. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 34, 530–535.

- [69] Kulchitskaya, D.B.; Konchugova, T.V.; Fedorova, N.E. High- vs low-intensity laser on microcirculation in knee arthritis. J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 2017, 826, 012015.

- Lu, Q.; Yin, Z.; Shen, X.; et al. HILT in chronic refractory wounds: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e045866. [CrossRef]

- Naruseviciute, D.; Kubilius, R. HILT vs LLLT in plantar fasciitis: Participant-blind RCT. Clin. Rehabil. 2020, 34, 1072–1082. [CrossRef]

- Nazari, A.; Moezy, A.; Nejati, P.; Mazaherinezhad, A. HILT vs conventional physiotherapy and exercise in knee osteoarthritis: 12-week RCT. Lasers Med. Sci. 2019, 34, 505–516. [CrossRef]

- Ordahan, B.; Karahan, A.Y.; Kaydok, E. HILT vs LLLT in plantar fasciitis: Randomized clinical trial. Lasers Med. Sci. 2018, 33, 1363–1369. [CrossRef]

- Ordahan, B.; Yigit, F.; Mülkoglu, C. LLLT vs HILT in adhesive capsulitis: Randomized clinical trial. Saudi J. Med. Med. Sci. 2023, 11, 201–207. [CrossRef]

- Ozlu, O.; Atilgan, E. HILT in patellofemoral pain syndrome: Single-blind RCT. Lasers Med. Sci. 2024, 39, 103. [CrossRef]

- Zielińska, P.; Soroko, M.; Godlewska, M.; et al. Photothermal effects of HILT on superficial digital flexor tendon in racehorses. Animals (Basel) 2022, 12, 1253. [CrossRef]

- Pekyavas, N.O.; Baltaci, G. Short-term effects of HILT, manual therapy, and Kinesio taping in subacromial impingement syndrome. Lasers Med. Sci. 2016, 31, 1133–1141. [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, M.S.; Jafari-Nozad, A.M.; Jazebi, F. HILT + quadriceps biofeedback vs exercise in knee OA: RCT. Anesth. Pain Med. 2024, 14, e143642. [CrossRef]

- Saleh, M.S.; Shahien, M.; Mortada, H.; et al. High-intensity vs low-level laser in musculoskeletal disorders. Lasers Med. Sci. 2024, 39, 179. [CrossRef]

- Salli, A.; Akkurt, E.; Izki, A.A.; Şen, Z.; Yilmaz, H. HILT vs epicondylitis bandage in lateral epicondylitis. Arch. Rheumatol. 2016, 31, 234–238. [CrossRef]

- Santamato, A.; Solfrizzi, V.; Panza, F.; et al. HILT vs ultrasound in subacromial impingement: Randomized clinical trial. Phys. Ther. 2009, 89, 643–652. [CrossRef]

- Siriratna, P.; Ratanasutiranont, C.; Manissorn, T.; Santiniyom, N.; Chira-Adisai, W. Short-term efficacy of HILT in knee osteoarthritis: Single-blind RCT. Pain Res. Manag. 2022, 2022, 1319165. [CrossRef]

- Sudiyono, N.; Handoyo, R. High- vs low-level laser in moderate carpal tunnel syndrome. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 52, 335–342.

- Tache-Codreanu, D.L.; Trăistaru, M.R. Effectiveness of HILT in lumbar disc herniation. Life (Basel) 2024, 14, 1302. [CrossRef]

- Thabet, A.A.E.; Elsodany, A.M.; Battecha, K.H.; Alshehri, M.A.; Refaat, B. HILT vs pulsed electromagnetic field in primary dysmenorrhea. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2017, 29, 1742–1748. [CrossRef]

- Thabet, A.A.E.; Mahran, H.G.; Ebid, A.A.; Alshehri, M.A. Pulsed HILT on delayed Caesarean section healing in diabetic women. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2018, 30, 570–575. [CrossRef]

- Tkocz, P.; Matusz, T.; Kosowski, Ł.; et al. HILT for painful calcaneal spur with plantar fasciitis: Randomised-controlled clinical study. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 4891. [CrossRef]

- Venosa, M.; Romanini, E.; Padua, R.; Cerciello, S. HILT vs ultrasound+TENS in cervical spondylosis: RCT. Lasers Med. Sci. 2019, 34, 947–953. [CrossRef]

- Viliani, T.; Carabba, C.; Mangone, G.; et al. High-intensity pulsed Nd:YAG laser in painful knee osteoarthritis: The biostimulating protocol. Energy Health 2012, 9, 18–22.

- Yesil, H.; Dundar, U.; Toktas, H.; Eyvaz, N.; Yeşil, M. HILT in painful calcaneal spur: Double-blind placebo-controlled study. Lasers Med. Sci. 2020, 35, 841–852. [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, M.; Tarakci, D.; Tarakci, E. HILT vs ultrasound+TENS for cervical pain due to disc herniation: Randomized trial. Complement. Ther. Med. 2020, 49, 102295. [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, M.; Eroglu, S.; Dundar, U.; Toktaş, H. HILT in subacromial impingement: 3-month double-blinded randomized placebo-controlled trial. Lasers Med. Sci. 2022, 37, 241–250. [CrossRef]

- Zare Bidoki, M.; Vafaeei Nasab, M.R.; Khatibi Aghda, A. HILT vs extracorporeal shock wave therapy in plantar fasciitis: Double-blind randomized clinical trial. Iran J. Med. Sci. 2024, 49, 147–155. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).