Submitted:

05 November 2025

Posted:

06 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Pain

2.3.2. Psychological Distress

2.2.3. Optimism About Recovery

2.3.4. Manchester Colour Wheel

- Which colour do feel most drawn to?

- What colour is your favourite colour?

- What colour represents your day-to-day mood?

- What colour represents your day-to-day pain?

2.4. Software and data analysis

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Findings

3.1.1. Onboarding Statistics

3.1.2. Onboarding Statistics by Injury Types

3.1.3. Program Outcomes by Injury Type

3.2. Construct Validity of the Manchester Colour Wheel

3.2.1. Sensitivity to Injury Type

3.2.2. Sensitivity to Pain Severity Classification

3.2.3. Sensitivity to Anxious Classification

3.2.4. Sensitivity to Stress Classification

3.2.5. Sensitivity to Depressed Classification

3.2.6. Sensitivity to Pain Catastrophisation Classification

3.2.7. Sensitivity to Kinesiophobia Classification

3.3. Predictive Validity of the MCW

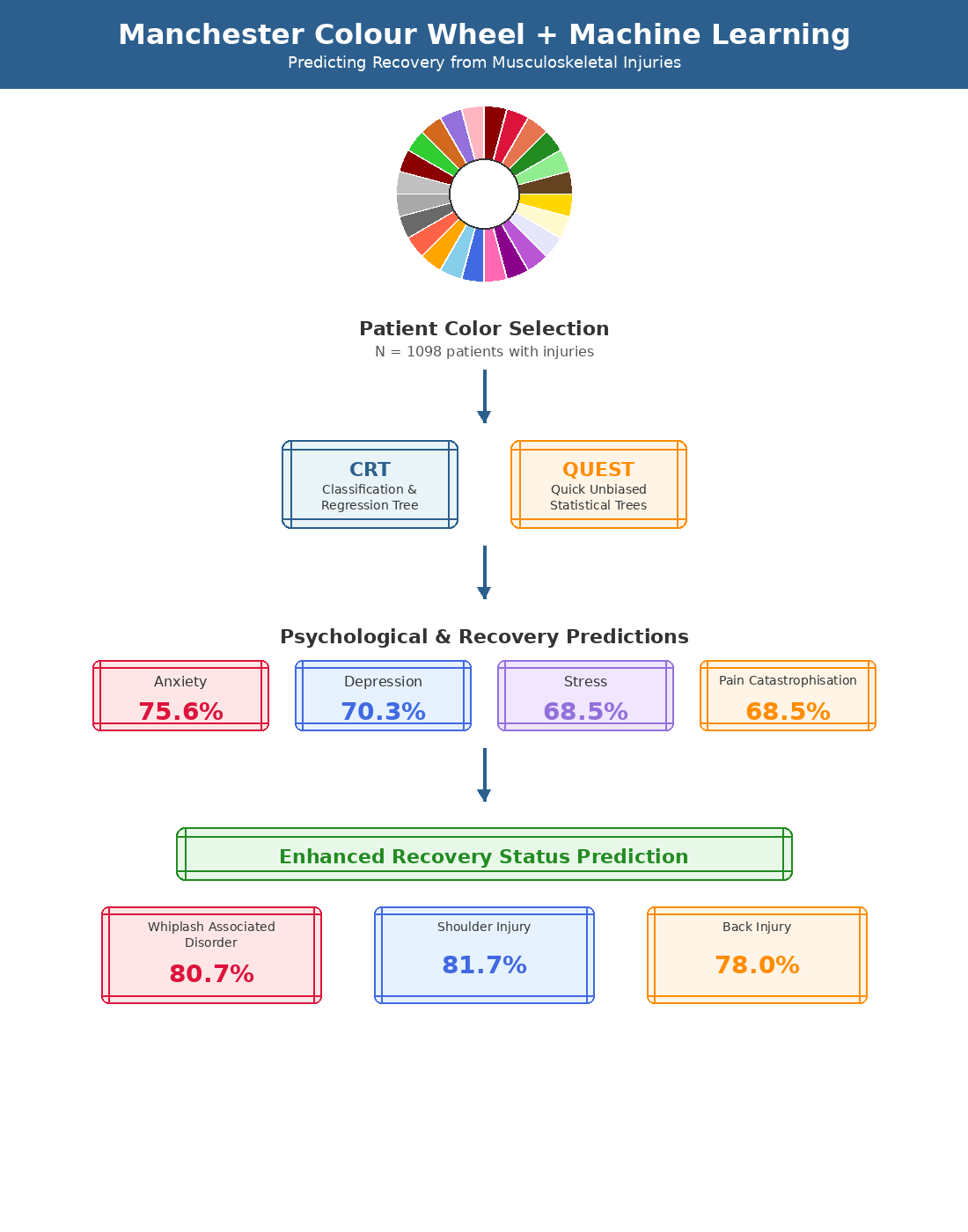

3.3.1. Recovery Models

3.3.2. Whiplash Associated Disorder Recovery Prediction Models

3.3.3. Back Injury Recovery Prediction Models

3.3.4. Shoulder Injury Recovery Prediction Models

3.3.5. Neck Injury Recovery Prediction Models

3.3.6. Comparison of Features in Recovery Prediction Models

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ARC | Active Recovery Clinics |

| AW | Administrative Withdrawal |

| BI | Back Injury |

| CHAID | Chi-Square Automatic Interaction Detector |

| CRT | Classification and Regression Tree Model |

| DI | Digital Intervention |

| DNC | Did Not Commence |

| DNCP | Did Not Complete |

| EMDR | Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing Therapy |

| FR | Full Recovery |

| MCW | Manchester Colour Wheel |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| MVC | Motor Vehicle Crash |

| NBC | Naïve Bayesian Classifier |

| NI | Neck Injury |

| NR | No Recovery |

| PR | Partial Recovery |

| PTSD | Posttraumatic Stress Disorder |

| QUEST | Quick Unbiased Efficient Statistical Tree |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SI | Shoulder Injury |

| SW | Surgical Withdrawals |

| USC | Unsuitable for Clinic |

| VAS | Visual Analogue Pain Scale |

| WAD | Whiplash Associated Disorder |

References

- Cattel, R.B. Personality Structure: Principles in Common to Q-, L- and T-Data. In: Cattel RB. Personality and mood by questionnaire. Jossey-Bass: San Fransciso CA, USA, 1973; pp. 1-23.

- Carruthers, H.R.; Morris, J.; Tarrier, N.; Whorwell, P.J. The Manchester Colour Wheel: development of a novel way of identifying color choice and its validation in healthy, anxious and depressed individuals. BMC Med Res Methodol 2010, 10, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carruthers, H.R.; Morris, J.; Tarrier, N.; Whorwell, P.J. Mood colour choice helps to predict response to hypnotherapy in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. BMC Complement Med Ther 2010, 10, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carruthers, H.R.; Magee, L.; Osborne, S.; Hall, L.K.; Whorwell, P.J. The Manchester Colour Wheel: validation in secondary school pupils. BMC Med Res Methodol 2012, 12, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carruthers, H.R.; Whorwell, P.J. The Manchester Colour Wheel: enhancing its utility. Percept Mot Skills 2013, 116, 761–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrick, C.B.; Taylor, D.; Correa, E.I. Colour sensitivity and mood disorders: biology or metaphor. J Affect Disord 2002, 68, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, N.; Epps, H. Relationship between color and emotion: A study of college students. Coll Stu J 2004, 38, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, V.; Carruthers, H.R.; Moors, J.; Hasan, S.S.; Archbold, S.; Whorwell, P.J. Hypnotherapy for irritable bowel syndrome: an audit of one thousand adult patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015, 41, 844–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carruthers, H.R. Imagery colour and illness: A review. J Vis Comm 2011, 34, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, M. Mark Grant’s EMDR Pain Protocol. 2016: https://emdrtherapyvolusia.com/wpcontent/uploads/2016/12/Mark_Grants_Pain_Protocol.pdf.

- Carruthers, H.; Miller, V.; Morris, J.; Eveans, R.; Tarrier, N.; Whorwell, P.J. Using art to help understand the imagery of irritable bowel syndrome and its response to hypnotherapy. Int J Clin Exp Hypn 2009, 57, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, M.; Threlfo, C. EMDR in the treatment of chronic pain. J Clin Psychol 2002, 58, 1505–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demaree, H.A.; Everhart, D.E.; Youngstrom, E.A.; Harris, D.W. Brain lateralization of emotional processing: historical roots and future incorporating “dominance”. Beh Cogn Neurosci Rev 2005, 4, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wager, T.D.; Phan, K.L.; Liberzon, I.; Taylor, S.F. Valence, gender, and lateralization of functioning brain anatomy in emotion: a meta-analysis of findings from neuroimaging. NeuroImage 2003, 19, 513–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegal, D.J. An interpersonal neurobiology of psychotherapy: The developing mind and the resolution of trauma. In: Solomon M, Siegle DJ, editors. Healing Trauma. W.W. Norton, New York, USA 2002; pp. 1-56.

- Wyczesany, M.; Capotosto, P.; Zappadsodi, F.; Prete, G. Hemispheric asymmetries and emotions: evidence from effective connectivity. Neuropsychologia 2018, 121, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palomero-Gallagher, N.; Amunts, K. A short review on emotion processing: a lateralized network of neuronal networks. Brain Struct Funct 2022, 227, 673–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdallah, C.G.; Geha, P. Chronic pain and chronic stress: two sides of the same coin. CS 2017, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puntillo, F.; Giglio, M.; Paladini, A.; Perchiazzi, G.; Viswanath, O.; Urits, I.; Sabba, C.; Varrassi, G.; Brienza, N. Pathophysiology of musculoskeletal pain: a narrative review. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis 2021, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Khalifa, M.; Albadawy, M. AI in diagnostic imaging: revolutionising accuracy and efficiency. Comput Methods Programs in Biomed Update 2024, 5, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, O.F.; Perry, F.; Salehi, M.; Bandurski, H.; Hubbard, A.; Ball, C.G.; Hameed, S.M. Science fiction or clinical reality: a review of the applications of artificial intelligence along the continuum of trauma care. World J Emerg Surg 2023, 18, 16–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliaferrie, S.D.; Angelova, M.; Zhao, X.; Owen, P.J.; Miller, C.T.; Wilkin, T.; Belavy, D.L. Artificial intelligence to improve back pain outcomes and lessons learnt from clinical classification approaches: Three systematic reviews. NPJ Digit Med 2020, 3, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corban, J.; Lorange, J.-P.; Lavereiere, C.; Khoury, J.; Richevsky, G.; Burman, M.; Marineau, P.A. Artificial Intelligence in the management of anterior cruciate ligament injuries. Orhop J Sports Med 2021, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkotis, C.; Moustakidis, S.; Tsatalas, T.; Ntakolia, C.; Chalatsis, G.; Konstadakos, S.; Hantes, M.E.; Giakis, G.; Tsaopoulous, D. Leveraging explainable machine learning to identify gait biomechanical parameters associated with anterior cruciate ligament injury. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 6647–6659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajaei, F.; Cheng, S.; Williamson, C.A.; Wittrup, E.; Najarian, K. AI-based decision support system for traumatic brain injury: A survey. Diagn 2023, 13, 1640–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awasthi, A.; Bhaskar, S.; Panda, S.; Roy, S. A review of brain injury at multiple time scales and its clinical pathological correlation through in silico modelling. Brain Metaphysics, 2024, 5, 100146–100158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigurdon, H.; Chan, J.H. Machine learning applications to sports injury: a review. icsSPORTS 2021, 157–168. [Google Scholar]

- Schultebraucks, K.; Chang, B.P. The opportunities and challenges of machine learning in the acute care setting for precision prevention of posttraumatic stress sequelae. Exp Neurol 2021, 336, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, C.E.; Laska, E.M.; Lin, Z.; Xu, M.; Abu-Amara, D.; Jeffers, M.K.; Meng, Q.; Milton, N.; Flory, J.D.; Hammamieh, R.; Diagle BJJr Gautam, A.; Dean, K.R.; Reus, V.I.; Wokowitz, O.M.; Mellon, S.H.; Ressler, K.J.; Yehuda, R.; Wang, K.; Hood, L.; Doyle, I.I.I.F.J.; Jett, M.; Marmar, C. Utilization of machine learning for identifying symptom severity military-related PTSD subtypes and their biological correlates. Transl Psychiatry 2021, 11, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, A.H.; Mirabelli, P.H.; Elder, S.; Steyrl, D.; Lueger-Shuster, B.; Scharnowski, F.; O’Connor, C.; Martin, P.; Lanius, R.A.; Mckinnon, M.C.; Nicholson, A.A. Machine learning models predict PTSD severity and functional impairment: A personalized medicine approach for uncovering complex associations among heterogenous symptom profiles. Psychol Trauma: Theory Res Pract Policy 2023, 17, 372–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutcher, M.E.; Goodin, B.R.; Rao, U.; Mooris, M.C. Predicting pain among female survivors of recent interpersonal violence: A proof-of-concept machine-learning approach. PLOSOne. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozzi, N.; Preatoni, G.; Ciotti, F.; Hubli, M.; Schweinhardt, P.; Curt, S.; Raspopovic, S. Unravelling the physiological and psychosocial signatures of pain by machine learning. Med 2024, 13, 1495–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worksafe Australia. Workers’ Compensation-Bodily Location [Internet]. 2022 [cited 20th November 2024]. Available from: https://data.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/interactive-data/topic/workers-compensation.

- State Insurance Regulatory Authority. Guidelines for the management of acute whiplash associated disorders for health professionals. Sydney: third edition 2014.

- Cui, D.; Janela, D.; Costa, F.; Molinos, M.; Areias, A.C.; Moulder, R.G.; Scheer, J.K.; Bento, V.; Cohen, S.P.; Yanamadala, V.; Correia, F.D. Randomized-controlled trial assessing a digital care program versus conventional physiotherapy for chronic low back pain. NPJ Digit Med 2023, 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sword Health Inc. Sword [Internet]. 2024 [Cited 30 November 2024]. Available from: https://swordhealth.com/.

- Janela, D.; Costa, F.; Molinos, M.; Moulder, R.G.; Lains, J.; Francisco, G.E.; Bento, V.; Cohen, S.P.; Correia, F.D. Asynchronous and tailored digital rehabilitation of chronic shoulder pain: A prospective longitudinal cohort study. J Pain Res 2022, 8, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Areias, A.; Costa, F.; Janela, D.; Molinos, M.; Moulder, R.G.; Lains, J.; Scheer, J.K.; Bento, V.; Yanamadala, V.; Cohen, S.P.; Correia, F.D. Impact on productivity impairment of a digital care program for chronic low back pain: A prospective longitudinal cohort study. Musculoskelet Sci Pract 2023, 63, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janela, D.; Costa, F.; Areias, A.C.; Molinos, M.; Moulder, R.G.; Lains, J.; Bento, V.; Scheer, J.K.; Yanamadala, V.; Cohen SPet, a.l. Digital care programs for chronic hip pain: A prospective longitudinal cohort study. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, F.; Janela, D.; Molinos, M.; Lains, J.; Franscisco, G.E.; Bento, V.; Correia, F.D. Telerehabilitation of acute musculoskeletal multi-disorders: Prospective, single arm, interventional study. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 2022, 23, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaegter, H.B.; Handberg, G.; Kent, P. Brief psychological screening questions can be useful for ruling out psychological conditions in patients with chronic pain. Clin J Pain 2018, 35, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, A.-M. The minimum clinically significant difference in visual analogue scale pain score does not differ with severity of pain. Emerg Med J 2001, 18, 205–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, F. EMDR Institute Basic Training Course Weekend 2 Training of The Two Part EMDR Therapy Basic Training. 1990-2022. EMDR Institute Inc.

- Vlaeyen, J.W.; Kole-Snijders, A.M.; Boeren RGet, a.l. Fear of movement/(re)injury in chronic low back pain and its relation to behavioural performance. Pain 1995, 62, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, D.A.; Lambert, B.S.; Boutris, N.; McCulloch, P.C.; Robbins, A.B.; Moreno, M.R.; Harris, J.D. Validation of Digital Visual Analog Scale Pain scoring with a traditional paper-based visual analog scale in adults. JJAAOS Glob Res Rev 2018, 2, e088–e094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.P.; Chen, C.; Brugger, A.M. Interpretation of visual analog scale ratings and change scores: a reanalysis of two clinical trials of postoperative pain. J Pain 2003, 4, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonstra, A.M.; Schiphorst Preuper, H.R.; Balk, G.A.; Stewart, R.E. Cut-off points for mild, moderate, and severe pain on the visual analogue scale for pain in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Pain 2014, 155, 2545–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams JBet, a.l. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Williams, G. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In Spacapan S, Oskamp S Editors. The Social Psychology of Health. Newbury park, CA: Sage; 1988: 31-66.

- Sullivan, M. The Pain Catastrophizing Scale. 2009 Available at: https://www.oregon.gov/oha/HPA/dsi-pmc/PainCareToolbox/Pain%20Catastrophizing%20Scale.pdf.

- Kroenk, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlayen, J.; Kole-Snijders, A.; Boeran, R.; van Eek, H. Fear of movement/(re) injury in chronic low back pain and its relation to behavioural performance. Pain 1995, 62, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, C.R.; Patel, N.R. Exact Tests in SPSS: Fisher’s Exact Test and Monte Carlo Methods. IBM Spess Exact Tests. Uk: IBM Corporation; [accessed 2024 Jan 5] Available from: https://www.sussex.ac.uk/its/pdfs/PASW_Exact_Tests.pdf.

- Kass, G.V. An exploratory technique for investigating large quantities of categorical data. J Royal Stat Soc (Appl Stat), 1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brieman, L.; Friedman, J.H.; Olshen, R.A.; Stone, C.J. Classification and regression trees. Wodsworth & Brooks/Cole Advanced Books & Software, Monterey CA, USA 1987.

- Loh, W.; Shih, Y. Split selection methods for classification trees. Statistica sinica 1997, 7, 815–840. [Google Scholar]

- Vijaykumar B, Vikramkumar, Trilochan. Bayes and Naïve Bayes Classifier. Arixiv 2014, arXiv:1404.0933. [CrossRef]

| Status | N (%) | 1a | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| USC | 39 (3.37) | 47.43 (12.73) |

33.79 (45.59) |

57.7 (25.4) |

6.28 (2.63) |

7.13 (2.70) |

6.08 (3.36) |

5.87 (3.07) | 5.85 (3.44) |

5.51 (3.54) | 41.0/41.0/18.0 |

| SW | 38 (3.7) | 49.57 (13.00) | 14.29 (19.64) | 62.4 (19.9) | 5.55 (3.49) | 6.11 (3.29) | 5.55 (3.19) | 5.29 (3.12) | 5.58 (2.83) | 6.24 (3.07) | 7.9/71.1/21.0 |

| DNC | 153 (13.9) | 40.97 (13.33) | 13.27 (18.74) | 59.2 (22.8) | 6.21 (2.93) | 6.68 (2.63) | 6.24 (2.96) | 5.84 (2.73) | 5.72 (3.05) | 6.04 (3.09) | 30.1/66.0/3.9 |

| DNCP | 97 (8.9) | 40.92 (12.52) | 18.33 (28.61) | 65.2 (19.3) | 6.54 (3.01) | 7.46 (2.38) | 6.79 (2.97) | 6.51 (2.88) | 6.98 (2.81) | 6.80 (2.75) | 23.7/70.1/6.2 |

| AW | 5 (0.5) | 55.40 (7.37) | 7.40 (3.78) | 44.0 (20.7) | 4.20 (4.03) | 5.20 (3.11) | 4.40 (4.04) | 5.20 (4.09) | 3.60 (2.41) | 4.40 (2.41) | 40.0/60.0/0.0 |

| NR | 17 (1.6) | 43.53 (13.16) | 33.79 (45.99) | 61.8 (1.78) | 6.06 (2.70) | 6.94 (3.01) | 7.06 (2.82) | 6.18 (2.86) | 7.06 (2.25) | 7.94 (2.28) | 29.7/58.5/11.8 |

| NR Disc. | 62.5 (18.5) |

5.58 (3.73) |

6.33 (2.81) |

6.17 (3.09) |

5.17 (2.83) |

6.00 (2.29) |

6.00 (3.41) |

||||

| PR | 192 (17.5) | 44.55 (12.86) | 18.71 (25.00) | 58.9 (18.6) | 5.82 (2.96) | 6.51 (2.56) | 5.90 (2.97) | 5.45 (2.68) | 5.88 (2.72) | 5.49 (3.07) | 28.1/66.1/5.8 |

| PR Disc. | 51.9 (18.2) |

5.32 (2.89) |

5.76 (2.41) |

5.38 (2.78) |

4.99 (2.73) |

5.41 (2.49) |

5.29 (2.94) |

||||

| FR | 555 (50.5) | 41.34 (13.27) | 16.76 (35.00) | 42.9 (23.0) | 4.78 (3.11) | 5.38 (2.91) | 4.59 (3.19) | 4.36 (3.00) | 4.27 (3.10) | 4.36 (3.13) | 53.7/42.5/3.8 |

| FR Disc. | 41.3 (23.5) |

4.21 (3.09) |

4.73 (2.91) |

4.18 (3.05) |

4.10 (2.99) |

4.05 (3.03) |

4.32 (3.13) |

||||

| Cum. | 1096 (100) | 42.36 (13.28) | 17.51 (31.34) | 51.5 (23.6) | 5.42 (3.12) | 6.06 (2.88) | 5.37 (3.22) | 5.07 (3.00) | 5.13 (3.13) | 5.17 (3.21) | 100/100/100 |

| Injury | N | % | 1a | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| WAD | 260 | 23.72% | 40.06 (13.51) | 7.05 (4.38) | 53.8 (24.1) | 6.53 (2.66) | 5.99 (3.08) | 5.83 (3.15) | 5.17 (2.95) | 5.18 (3.29) | 5.15 (3.33) | 164.78 (16.62) |

| NI | 55 | 5.02% | 25.36 (11.40) | 25.36 (59.03) | 53.5 (21.4) | 6.85 (2.60) | 6.85 (2.60) | 5.91 (3.11) | 5.71 (3.13) | 6.11 (3.22) | 5.69 (3.21) | 242.20 (38.80) |

| BI | 364 | 33.21% | 41.30 (12.67) | 21.20 (36.67) | 51.9 (23.1) | 6.18 (2.82) | 5.47 (3.07) | 5.56 (3.20) | 5.14 (3.00) | 5.22 (3.09) | 5.21 (3.15) | 166.33 (18.82) |

| SI | 391 | 35.75% | 45.01 (13.49) | 20.69 (27.61) | 49.0 (23.7) | 5.47 (3.03) | 6.53 (2.66) | 4.78 (3.19) | 4.82 (3.00) | 4.88 (3.02) | 5.08 (3.17) | 218.54 (16.11) |

| Cum. | 1096 | 100 | 42.41 (13.26) | 17.53 (31.37) | 51.4 (23.6) | 6.05 (2.88) | 6.05 (2.88) | 5.37 (3.22) | 5.06 (3.00) | 5.13 (3.13) | 5.17 (3.21) | 188.77 (18.57) |

| Status | USC (%) | DNC (%) | DNCP (%) | NR (%) | PR (%) | FR (%) |

| WAD | 10 (2.75) | 52 (14.28) |

21 (5.76) |

5 (1.38) | 46 (12.67) | 150 (41.21) |

| NI | 5 (18.18) |

4 (7.27) |

6 (10.90) |

3 (5.46) |

12 (21.81) |

25 (45.45) |

| BI | 18 (4.97) | 51 (14.01) |

36 (9.90) |

5 (1.37) |

81 (22.25) |

171 (46.98) |

| SI | 44 (11.28) |

46 (11.76) |

34 (8.70) |

4 (1.02) |

53 (13.55) |

209 (53.45) |

| Cum. | 77 | 153 | 97 | 17 | 192 | 555 |

|

Classifier (Min. Parent/Child) |

Anxiety | Stress | Depress. | Pain C. | Kines C. |

| CHAID (10/2) Test CHAID (5/2) Test |

38.6/85.3/69.4 28.6/80.0/60.4 50.6/79.7/69.6 38.9/70.9/59.7 |

69.3/61.2/65.2 60.2/58.4/59.3 72.4/53.9/62.2 74.8/53.3/65.2 |

79.4/46.7/66.3 77.1/32.1/61.9 88.1/32.8/66.6 86.3/26.8/63.4 |

94.9/18.5/65.7 95.5/17.2/63.4 85.5/39.8/67.7 83.8/32.1/64.1 |

6.4/96.2/62.8 7.5/96.9/62.7 45.3/76.1/64.4 37.0/70.3/58.5 |

| Ex-CHAID (10/2) Test Ex-CHAID (5/2) Test |

0.0/100/64.8 0.0/100/65.5 26.8/91.7/68.3 23.0/88.8/68.7 |

55.5/71.9/63.7 51.0/61.9/56.9 72.9/50.8/61.7 73.1/61.8/67.3 |

79.8/43.1/65.1 85.2/38.6/69.8 94.3/21.1/66.1 88.5/25.3/63.5 |

87.9/37.3/69.1 84.2/30.2/59.5 87.3/32.6/66.4 89.6/28.3/64.6 |

0.9/99.8/63.3 0.0/98.5/60.0 37.3/80.4/64.4 27.9/77.9/56.5 |

| CRT (10/2) Test CRT (5/2) Test |

61.4/77.8/71.9 66.7/79.5/75.6 50.2/85.9/74.0 33.7/84.7/63.4 |

67.7/63.7/70.0 77.5/59.2/68.5 79.3/63.7/71.4 64.5/61/4/62.9 |

87.3/54.3/74.8 77.4/45.3/63.7 85.1/55.1/73.3 83.5/73.3/70.3 |

84.1/59.9/74.7 75.4/41.9/62.3 83.4/57.8/73.6 78.1/41.5/63.2 |

50.6/79.5/68.5 37.2/67.3/57.0 42.4/82.6/67.2 19.7/79.5/59.6 |

| QUEST (10/2) Test QUEST (5/2) Test |

11.6/97.2/68.0 9.0/97.7/64.4 19.9/93.5/69.1 14.6/87.1/56.8 |

64.2/67.1/65.8 59.7/60.2/59.9 65.2/64.6/64.9 62.8/64.1/63.5 |

87.6/26.7/64.0 86.8/14.0/58.6 86.4/39.9/68.1 82.7/37.5/66.2 |

89.5/23.6/63.6 92.8/28.2/69.4 89.3/22.6/63.4 89.7/16.7/61.8 |

7.4/97.1/64.1 6.0/98.4/61.4 0.0/100/62.6 0/100/62.7 |

| NBC Test |

45.9/94.0/78.0 33.7/85.8/67.4 |

73.3/82.1/77.7 65.8/63.6/60.3 |

75.6/60.1/73.4 68.1/60.4/65.1 |

87.2/46.7/72.0 72.8/33.9/58.2 |

46.2/86.0/69.4 27.3/77.8/59.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).