1. Introduction

The explosive development of Android applications and the concurrent development in malware sophistication have placed classical detection mechanisms ineffective. Static signature-based approaches and heuristic rule sets, which were until recently effective, are progressively failing to deal with polymorphic, metamorphic, and obfuscated malware [

1]. Android's open nature and open app distribution channels, specifically, have further increased the attack surface, with attackers able to circumvent detection using progressively more sophisticated techniques.

To counter these, deep learning and machine learning have turned out to be game-changing assets in the domain of cybersecurity [

2], enabling dynamic detection of unknown threats and feature extraction automation. Most importantly, Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and their variants in the form of Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) have been able to represent sequential patterns of opcode streams and API call logs [

3]. These models have the capability to learn temporal dependencies that are crucial in distinguishing benign from malicious behavior.

However, RNN-based designs suffer from problems such as vanishing gradients, the failure to model long-term dependencies, and low parallelisation [

4]. Transformers, originally designed for natural language processing, overcome these drawbacks using self-attention mechanisms that can capture global context and token relationships more effectively [

4]. Recent advancements in time-series analysis and cybersecurity domains suggest potential applicability in malware detection as well [

5]. Despite this possibility, comparative studies in the context of malware analysis, particularly organized datasets like EMBER-2018, are absent. Additionally, detection accuracy, generalizability of the model, and computation cost are not investigated altogether.

Here, we introduce an adaptive and robust method for Android malware detection that compares systematically the performance of RNN-LSTM models with that of the Transformer paradigm. Training, testing, and comparison of both approaches are performed on different performance metrics using opcode and bytecode features of the EMBER-2018 dataset. Our findings suggest that RNN-LSTM models are efficient and effective when used with known patterns, whereas Transformer-based methods have superior generalization and detection of new malware samples. By closing this comparative gap, our research provides useful insights into the creation of scalable, smart malware detection systems that can be instantiated in real-time within mobile and enterprise settings.

2. Background Study

CIA of information systems is also on target as malwares and other cyber-attacks continue to rise. Authors have presented the review [

6] with respect to malware detection and classification covering from year 2020 to year 2024. Malware detection and classification frameworks have several advances from detecting sophisticated threats to assembling deep learning models. A focus on improving detection accuracy, malware behavior analysis, and feature extraction with study of various detection techniques like hybrid models, deep learning, and machine learning. The use of unnecessary software, i.e., malwares for crafting the cyber-attacks is common as the malware classification and malware detection are tough. Researchers came up with the new technique for malware classification and detection - Automated Android malware detection via Optimal ensemble learning approach for Cybersecurity (AAMD-OELAC). With the comprehensive experimental analysis and portraying of simulation results the AAMD-OELAC methods have seen success over other existing methods.

The presence of covid virus has changed the lives of almost everyone since 2019, as variants of malwares continue to rise. A novel deep learning-based architecture is proposed by researchers because traditional AI and ML algorithms cannot detect new malware variants and are no longer effective on that [

7]. Using several datasets like Malevis dataset, Microsoft BIG 2015 dataset, and Malimg dataset, this proposed method outperforms other methods (including most of the ML-based malware detection) with around 97.78 % accuracy in malware detection.

There is no doubt that there are several cybersecurity related challenges, and several novel approaches are applied for those cybersecurity challenges - as one of them is Quantum machine learning (QML) [

8]. QML improves the classical ML approach as it leverages quantum computing to solve real-world problems. Authors have developed and designed QML-based learning modules by applying case studies of student-centric nature. The utilization of Quantum support vector machine (QSVM) using open-source Pennylane QML framework for malware classification and malware attack protection.

Out of many cybersecurity issues, and several cyber threats, one primary issue is the malware, as there are more than 350K such malicious programs and unwanted applications [

9]. The need of automatic malware classification and malware analysis is urgent as the “ENISA Threat Report 2018” 94% of all executable malwares are polymorphic. Authors have classified the malware using federated learning by considering data privacy and the novel method (proposed on dataset by VirusTotal) achieved a high accuracy of 0.917 approximately. An OELAC for automated malware detection for Android malware with automated identification and classification of malwares [

10].

Table 1.

Summary of the background study & several approaches with insights for malware detection, classification, and protection.

Table 1.

Summary of the background study & several approaches with insights for malware detection, classification, and protection.

| |

Insight 1 |

Insight 2 |

Insight 3 |

Ref. |

| PRISMA framework for malware detection |

Malware has exacerbated exposure to cyber threats. |

PRISMA 2020 analyses current malware trends. |

Data from WoS & Scopus covering from 2020 to 2024 |

[6] |

| DL algorithms for new malware classification |

Easier to commit crime in cyberspace than in regular life. |

Using advanced obfuscation malware variants continue. |

DL approach for detecting all variants of malware. |

[7] |

| Quantum SVM for malware classification |

Quantum computing to improve classical ML approach |

QML & case-study based learning modules for students. |

Utilize QSVM for malware classification & protection. |

[8] |

| Federate Learning for malware classification |

One important cybersecurity issue today is malware. |

AV-TEST institute - over 350K malware & PUP / day. |

Feature extraction based on malware with high accuracy. |

[9] |

| OELAC for automated malware detection |

ML algorithms are ineffective in identifying new malware. |

AAMD-OELAC technique: Automated Android Malware |

Automated classification & identification of malware. |

[10] |

3. Malwares on the Rise

Over the last decade, the scope and sophistication of malware intrusion have increased sharply. On average, approximately 560,000 new malware samples are identified daily, contributing to a reported 6.2 billion attacks in 2023 alone, illustrating the growing complexity of the digital threat landscape [

11]. Notably, adversaries are increasingly shifting toward evasive strains, such as info stealers, memory-resident Trojans, and modular malware variants, which avoid traditional detection methods [

12,

13]. The advent of malware-as-a-service (MaaS) offerings, such as RedLine and XLoader, has democratized malware deployment, enabling even low-skill attackers to access sophisticated payloads and scalable command-and-control mechanisms [

13]. Mobile-focused malware also saw a noticeable increase in 2024, with Android banking trojans such as Hook and GodFather exploiting advanced overlay-based exploits to compromise finance-related applications [

14,

15].

Modern malware frequently integrates obfuscation techniques such as polymorphic code generation, virtual machine detection evasion, and adaptive payload release, which significantly reduce the effectiveness of legacy static analysis tools [

16]. To address this, the cybersecurity domain increasingly relies on Artificial Intelligence (AI), particularly deep learning-based solutions. Architectures such as Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN), Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM), and transformer models have shown promise in detecting malicious behavior by modelling execution patterns through opcode sequences, system calls, and behavioural telemetry [

16,

17]. LSTM architectures specialize in modelling long-term temporal dependencies in dynamic malware behavior, whereas transformers that use self-attention offer superior global contextual understanding. The rise of generative malicious tools, such as WormGPT and FraudGPT, which can produce ever-evolving threats, further necessitates the deployment of intelligent and adaptable detection mechanisms built on these advanced AI systems [

18].

4. Model Architectures - RNN-LSTM vs Transformers

Traditional neural architectures such as Feedforward Neural Networks (FNNs) and Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) have well-known limitations when applied to high-dimensional structured data such as the EMBER feature vectors. FNNs process each input feature through fixed layers without capturing complex inter-feature relationships unless explicitly designed. RNNs, while capable of modelling sequential dependencies, are inherently sequential in nature—processing inputs one step at a time, which limits their ability to scale efficiently on long or high-dimensional inputs. Moreover, RNNs suffer from issues like vanishing gradients and long-term dependency degradation, which are unsuitable for static malware detection tasks where feature relationships are global and non-local.

In contrast, the Transformer architecture introduces a paradigm shift in how such structured inputs are processed. Instead of treating input features as isolated scalars or sequential tokens, Transformers enable parallel and holistic processing of the entire input vector through the mechanism of self-attention.

4.1. Key Advantages of Using Transformers for EMBER Feature Vectors

I. Parallel Processing and Scalability: Unlike RNNs that iterate over time steps, Transformers compute self-attention across all features simultaneously. This parallelism allows the model to process all 2,381 input features concurrently, leading to significant efficiency gains—especially when analysing large-scale malware samples or high-dimensional vectors. This becomes crucial when malware files contain deeply nested or complex binary structures that require capturing patterns across distant features.

II. Self-Attention: Capturing Global Context: The core strength of the Transformer lies in its self-attention mechanism, which computes pairwise interactions between all feature dimensions. For each feature, the model dynamically learns how much "attention" to pay to every other feature. This is particularly beneficial in static malware analysis, where the correlation between non-adjacent fields—e.g., header metadata and byte-level entropy—can be crucial for detecting obfuscation or malicious intent. In effect, self-attention enables the model to learn cross-feature dependencies, even when such relationships are long-range and non-obvious.

III. Multi-Head Attention: Diverse Representations: The use of multi-head attention enhances this capability by allowing the model to attend to the input space from multiple representation subspaces in parallel. Each attention head captures a different aspect or pattern in the feature vector, such as structural properties, byte-level distributions, or suspicious import behaviours. By aggregating these diverse perspectives, the model develops a richer, more context-aware representation of the input.

IV. Positional Awareness in Structured Data: Although the EMBER feature vectors are not sequential in the traditional sense, feature order can still encode domain-specific structure (e.g., header fields precede section information). By integrating positional encodings, the Transformer is made sensitive to feature positions, enabling it to differentiate between similarly valued features that occur in different locations.

V. Robustness to Irregular Feature Importance: Malware features often vary in importance depending on the sample. Self-attention allows the model to dynamically reweight features based on the context of each input instance, as opposed to static weightings in FNNs. This adaptive attention makes the model more robust to noise, adversarial feature manipulations, or irrelevant metadata.

4.2. Dataset

This study uses the EMBER 2018 dataset, a large-scale benchmark for static Windows malware classification. It provides pre-extracted and engineered feature vectors for each Portable Executable (PE) file. Each sample includes a vector of 2,381 numerical features representing various PE attributes (header data, imported functions, byte histograms, etc.), and a label indicating its classification as benign, malicious, or unknown. The dataset was stratified and split into 80% training and 20% validation subsets. Features were standardized using z-score normalization.

5. Proposed Framework – secRNNlong

5.1. Model Architecture

A custom Transformer-based architecture was designed for sequence modelling over feature vectors. Although the input is a flat feature vector (not a traditional sequence), the Transformer is adapted by treating each feature dimension as a "token" in the sequence. The model includes the following components. Input Projection: A linear layer projects each scalar feature to a d_model-dimensional embedding space. Positional Encoding: Injects position-specific signals to account for sequential dependencies across feature indices. Transformer Encoder: A stack of self-attention layers (nhead = 8, num_layers = 4) with feedforward sub-layers (dim_feedforward = 1024). Global Average Pooling: Collapses the sequence dimension to a single feature vector. Classification Head: A multi-layer perceptron (MLP) with ReLU activations and dropout, concluding with a linear output layer for binary classification. The model processes the input as a pseudo-sequence of shape (batch_size, seq_len=2381, d_model).

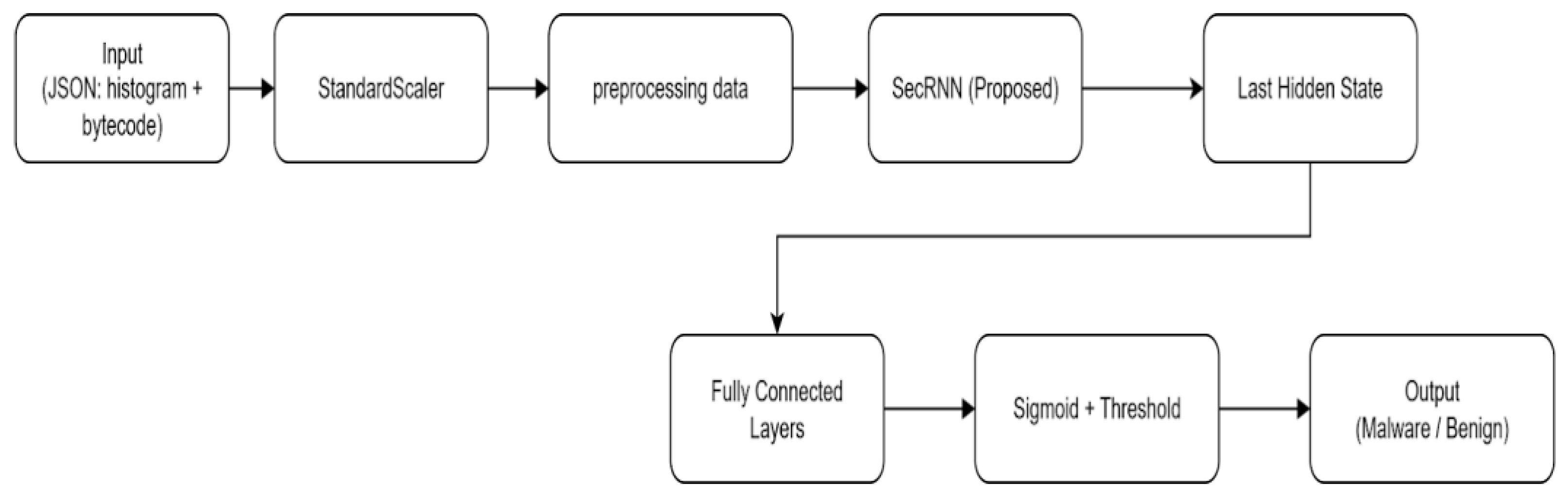

Figure 1.

Flowchart with secRNNlong (proposed) for malicious code classification.

Figure 1.

Flowchart with secRNNlong (proposed) for malicious code classification.

5.2. Training Procedure

Training was conducted using the PyTorch framework with the following configuration. Loss Function: CrossEntropyLoss for binary classification. Optimizer: AdamW with a learning rate of 0.0001 and weight decay 0.01. Scheduler: ReduceLROnPlateau, which reduces the learning rate on stagnating validation loss. Batch Size: 128, Epochs: 5 (prototyping phase). Device: GPU (CUDA) was utilized for accelerated training. Training included gradient clipping (max_norm = 1.0) for stability and used early model checkpointing based on best validation accuracy.

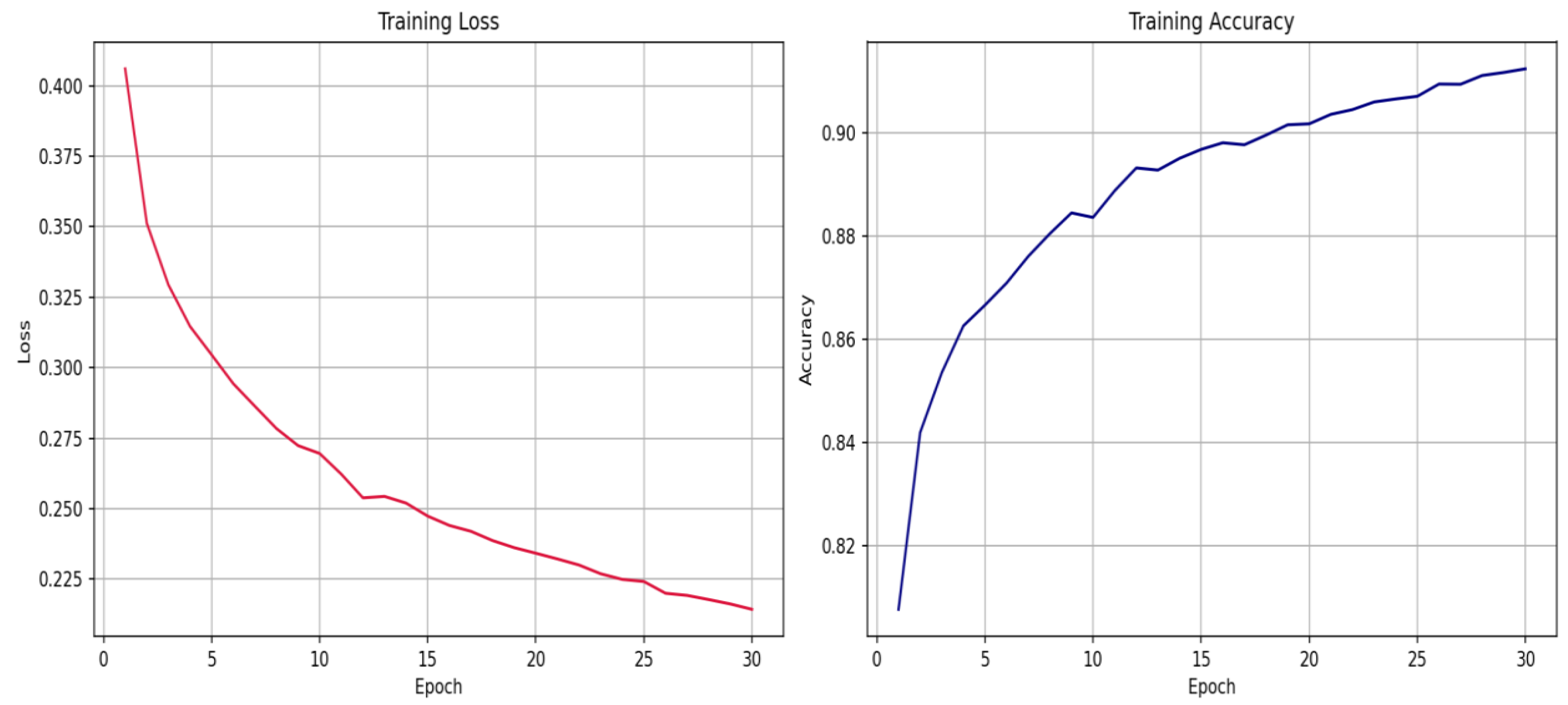

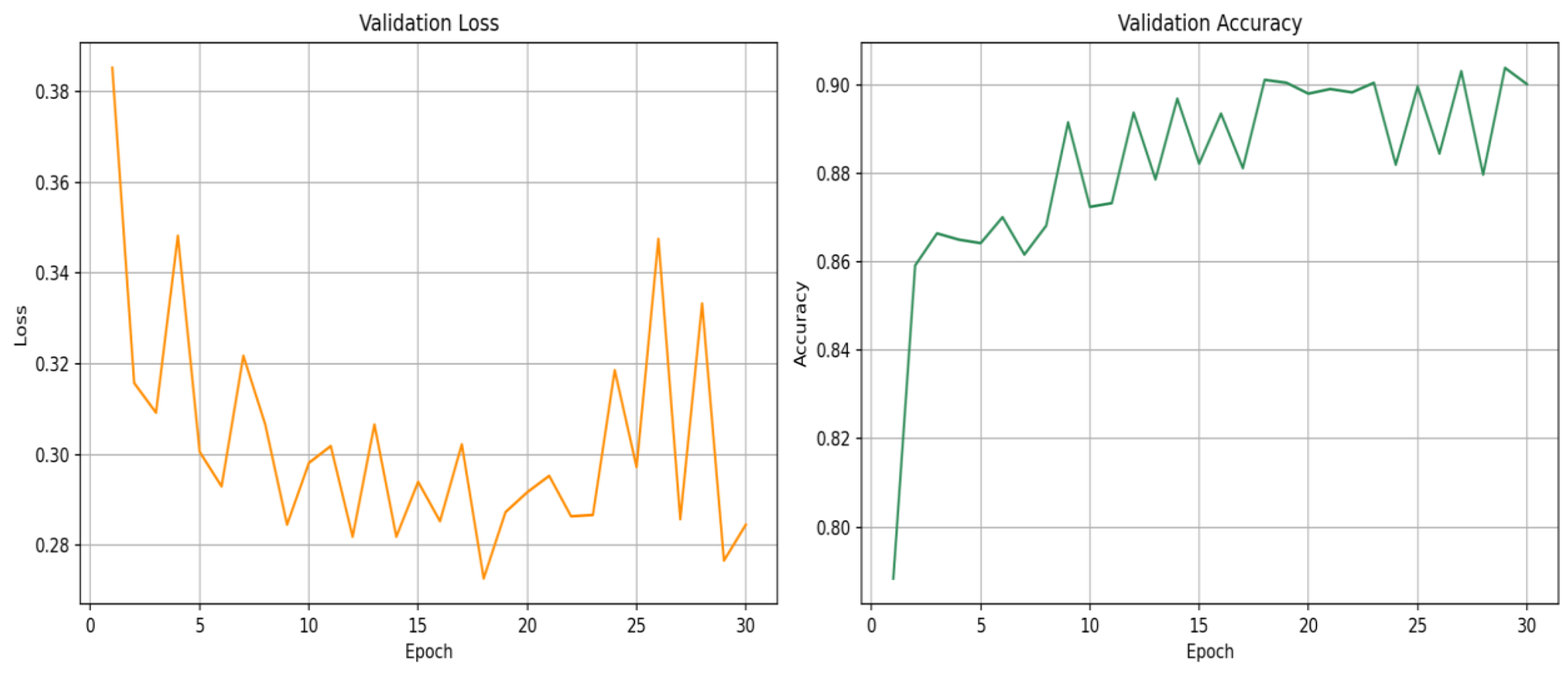

5.2.1. RNN-LSTM Training and Validation Curves

The training loss plot indicates a steady declining trend, reflecting good learning and decrease in classification error across 30 epochs. Training accuracy gradually increases, reaching well above 91%, which depicts the model's growing capacity to learn discriminative patterns in the training set. Although the validation loss oscillates slightly but declines overall, reflecting modest overfitting control and consistent generalization ability. Validation accuracy is consistently high, reaching above 90% towards the last epochs, reflecting the model's stability on unseen malware instances.

Figure 2.

secRNNlong Training loss and Training Accuracy (for RNN-LSTM).

Figure 2.

secRNNlong Training loss and Training Accuracy (for RNN-LSTM).

Figure 3.

secRNNlong Validation loss and Validation Accuracy (for RNN-LSTM).

Figure 3.

secRNNlong Validation loss and Validation Accuracy (for RNN-LSTM).

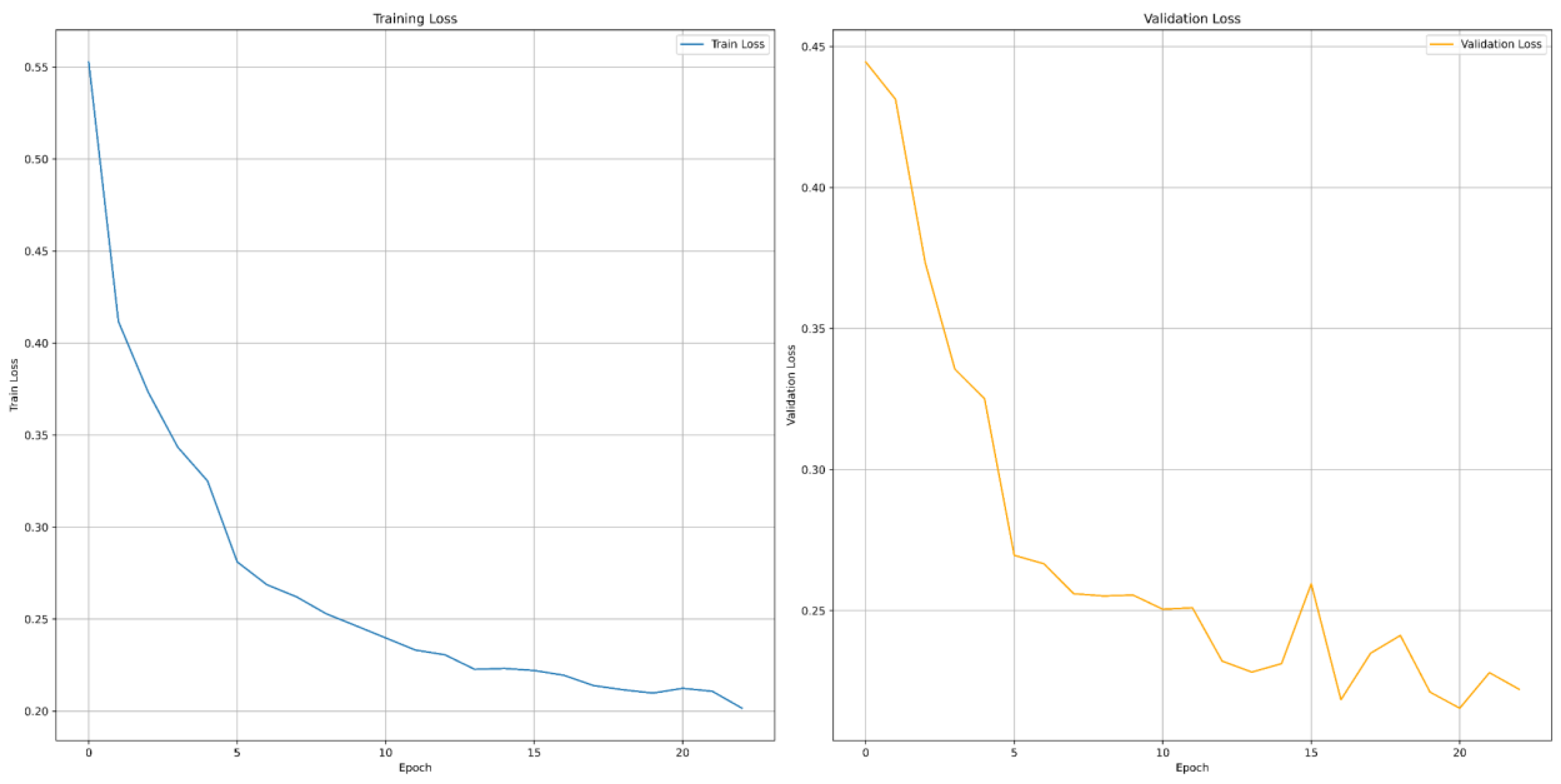

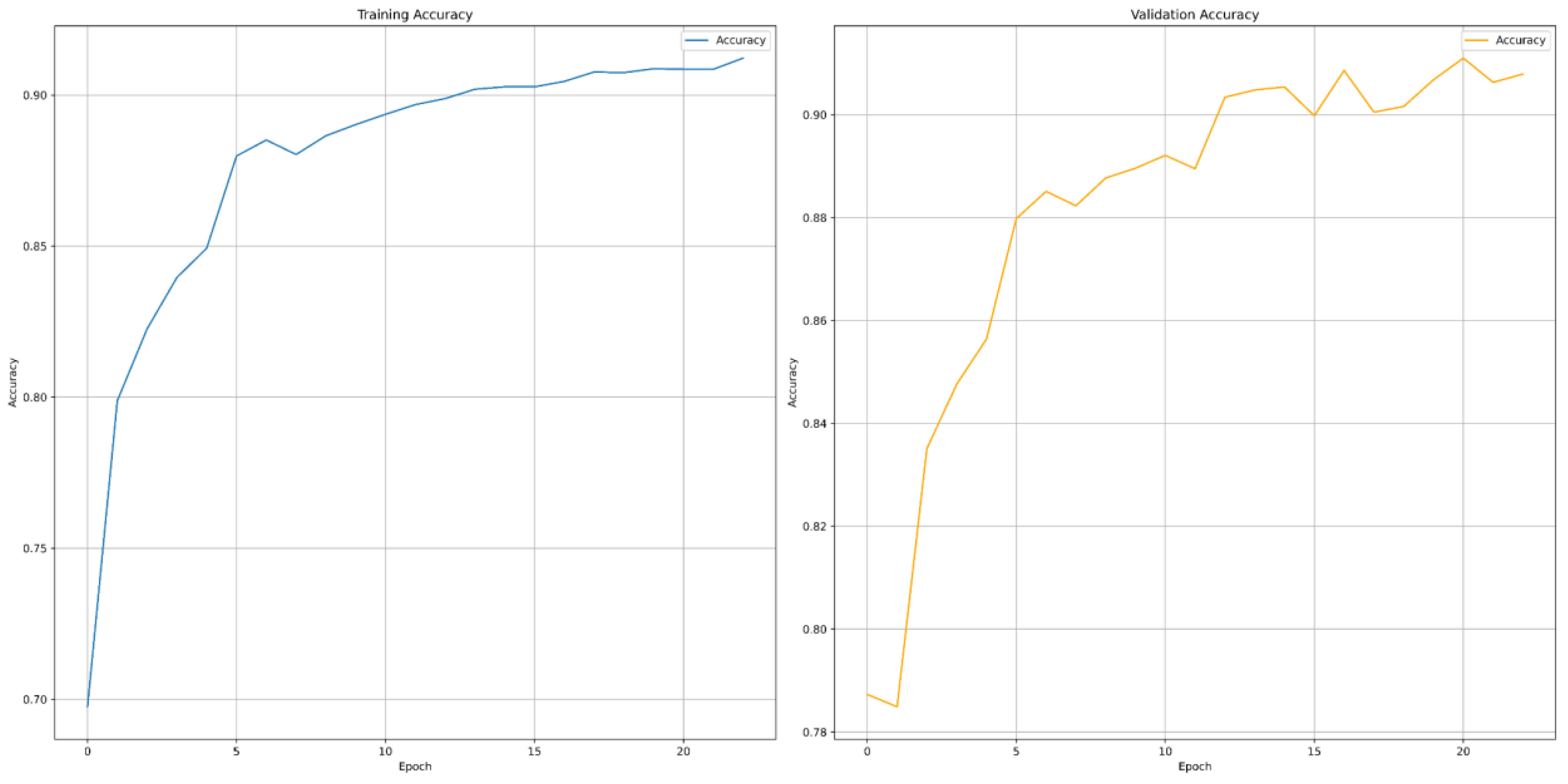

5.2.2. Transformers Training and Validation Curves

The training loss graph displays a sharp and consistent decline, confirming effective learning and improved optimization across the 22 training epochs. Training accuracy rises steadily, eventually crossing 91%, indicating the model's strong ability to capture relevant patterns from static features. While the validation loss shows a smooth downward trajectory with minimal fluctuations, suggesting stable generalization and minimal overfitting. Validation accuracy consistently increases and stabilizes above 90%, highlighting the model's high reliability in detecting unseen malware instances.

Figure 4.

secRNNlong Training loss and Training Accuracy (for Transformers).

Figure 4.

secRNNlong Training loss and Training Accuracy (for Transformers).

Figure 5.

secRNNlong Validation loss and Validation Accuracy (for Transformers).

Figure 5.

secRNNlong Validation loss and Validation Accuracy (for Transformers).

5.3. Evaluation

For the RNN-LSTM model, evaluation was conducted at the end of each epoch on the validation set. The following metrics were recorded: Training Loss and Accuracy, Validation Loss, and Accuracy. Over the course of training: Training loss decreased from ~0.55 to ~0.32. Validation loss dropped similarly from ~0.44 to ~0.32. Training accuracy improved from ~69.6% to ~84.8%. Validation accuracy increased from ~78.7% to ~85.6%.

For the Transformer model, we measured at the end of each epoch on the validation set. The metrics we recorded were Training Loss, Training Accuracy, Validation Loss, and Validation Accuracy. Training loss decreased significantly from ~0.55 to ~0.20 during training, and validation loss decreased from ~0.44 to ~0.22. Training accuracy increased consistently from ~69.8% to ~91.2%, and validation accuracy increased from ~78.5% to ~90.8%.

6. Conclusion & Future Scope

This study presents a comparative evaluation of two deep learning approaches for static malware detection using RNN with LSTM memory units and Transformer based models for Android malware detection, evaluated on the EMBER-2018 dataset. The study shows that both models have good detection performance. The RNN-LSTM model can detect known malware patterns well based on the temporal relationships it knows about given that it has a recurrent architecture. The Transformer model generalized, was more accurate, and had more robust training by using self-attention for the detection of complex and global patterns in the static feature space to achieve better classification performance. Experimental results revealed that RNN-LSTM found to achieve close to 90% accuracy in certain controlled settings achieved detection scores of over 99% in being able to recognize different malware variants while being more stable and adaptable. By seeing static feature vectors as sequences, the Transformer not only allowed for richer modelling of interactions among features but also provided a high degree of scalability needed in real-time detection settings.

Several advanced research and deployment pathways stand out building on the early positive outcomes of this comparative study. AI Co-pilots for Malware Analysts: Embedding Transformer models into analysts' workflows as intelligent assistants for suggesting paths of investigation, correlating threat intelligence, or autogenerating IOCs (Indicators of Compromise) could bring SOC (Security Operations Center) efficiency to new heights. Multimodal Malware Detection: Potential systems could fuse static, dynamic, and contextual features, encompassing, among others, system calls, network flows, and traces of user interaction, into joint embeddings which are then fed to Transformer-based models to achieve deeper behavioural understanding of malware beyond static signatures. Self-supervised Malware Representation Learning: Inspired by the NLP and vision realms, one could argue that a base task of pretraining large malware models on unlabelled corpora (e.g., large-scale unlabelled executables or memory dumps) and subsequent fine-tuning using labelled samples could drastically improve performance owing to the inference of available labels.

References

- K. Xu, Y. Li, R. H. Deng, and K. Chen. Deeprefiner: Multi-layer android malware detection system applying deep neural networks. In IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy (EuroS&P), 2018.

- C. M. Chen et al. Applying convolutional neural network for malware detection. In IEEE International Conference on Awareness Science and Technology (iCAST), 2019.

- S. I. Imtiaz et al. Deepamd: Detection and identification of android malware using high-efficient deep artificial neural network. Future Generation Computer Systems, 2021.

- P. Musikawan et. al. Enhanced deep learning neural network for android malware. IEEE Internet of Things Journal (IOTJ) 2022.

- Vaswani, N. Shazeer, N. Parmar, J. Uszkoreit, L. Jones, A. N. Gomez, L. Kaiser, and I. Polosukhin. Attention is all you need. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), 2017.

- S. Berrios, D. Leiva, B. Olivares, H. Allende-Cid, and P. Hermosilla. Systematic review: Malware detection and classification in cybersecurity. Applied Sciences, 15(14):7747, 2025.

- Ö. Aslan and A. A. Yilmaz. A new malware classification framework based on deep learning algorithms. IEEE Access, 9:87936–87951, 2021.

- M. S. Akter, H. Shahriar, S. I. Ahamed, K. D. Gupta, M. Rahman, A. Mohamed, and F. Wu. Case study-based approach of quantum machine learning in cy- bersecurity: quantum support vector machine for malware classification and protection. In 2023 IEEE 47th Annual Computers, Software, and Applications Conference (COMPSAC), pages 1057–1063, 2023.

- K. Y. Lin and W. R. Huang. Using federated learning on malware classification. In 2020 22nd International Conference on Advanced Communication Technology (ICACT), pages 585–589, 2020.

- H. Alamro, W. Mtouaa, S. Aljameel, A. S. Salama, M. A. Hamza, and A. Y. Othman. Automated android malware detection using optimal ensemble learning approach for cybersecurity. IEEE Access, 11:72509–72517, 2023.

- Deep Instinct. Cyber threat landscape report 2023. https://www.deepinstinct.com/resources/reports.

- IBM Security. X-force threat intelligence index 2023, 2023. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/reports/xforce-threat-intelligence.

- Kaspersky Labs. IT threat evolution 2023 Q3. https://securelist.com/it-threat-evolution-q3-2023/.

- Zimperium. Hook malware technical analysis 2024. https://www.zimperium.com/blog/hook-malware-analysis/.

- Cyble. Godfather android banking trojan report 2024. https://cyble.com/blog/godfather-trojan-targets-banking-apps/.

- Z. Xu, C. Shen, Y. Liu, and C. Wu. Malware detection using deep learning based on api call sequences. IEEE Access, 8:132235–132245, 2020.

- E. Raff et al. Malware detection by eating a whole exe. arXiv preprint arXiv:1710.09435, 2018.

- SlashNext. Wormgpt: Generative ai used for malware and phishing campaigns, 2023. Available online: https://www.slashnext.com/blog/wormgpt-malware/.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).