1. Introduction

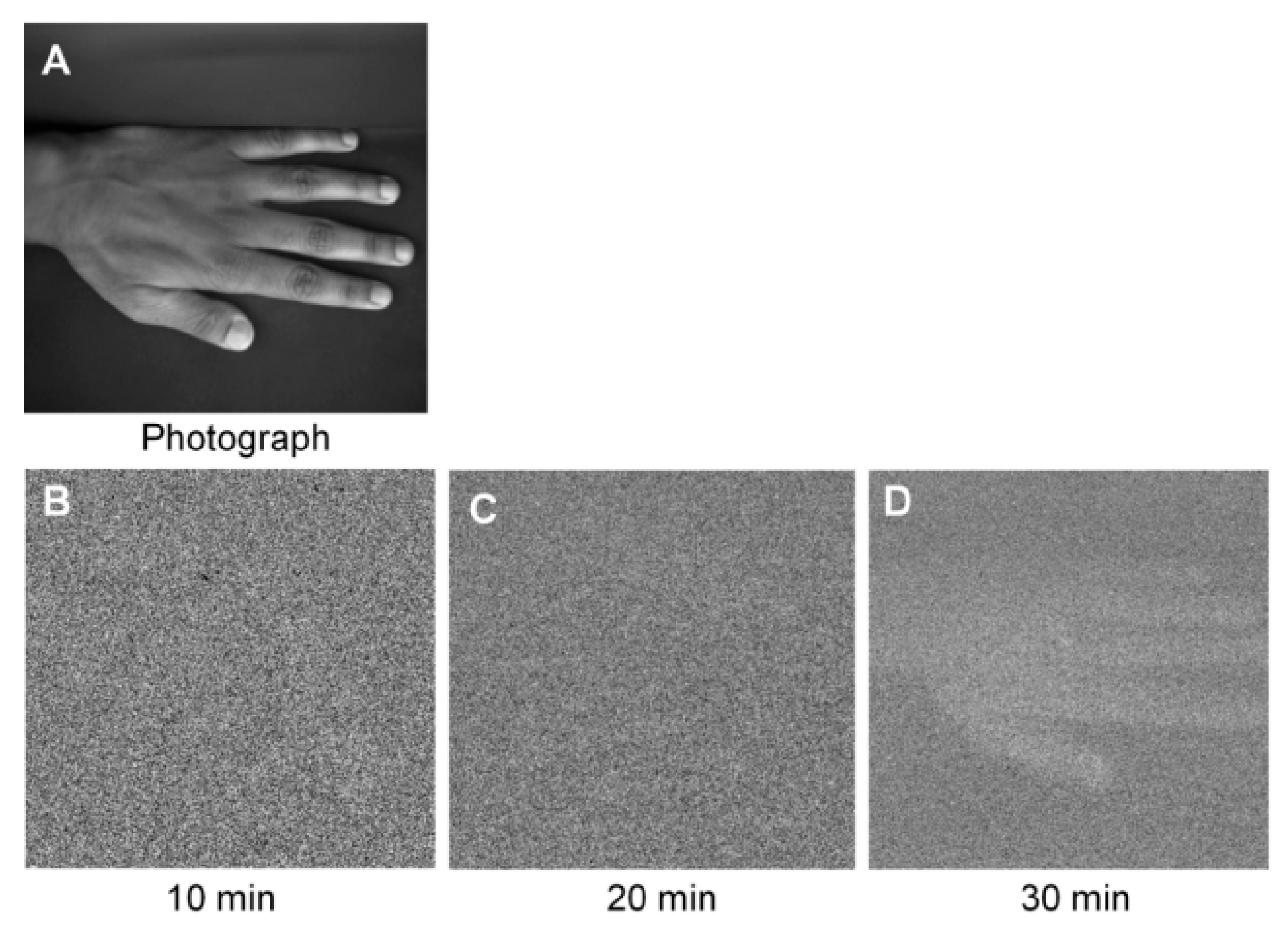

Photon emission by living cells – also known as biophoton emission – has received increasing attention in the fields of biophysics, biochemistry, and quantum biology in recent decades [

1,

2,

3]. This phenomenon refers to extremely low-intensity (ultra-weak) light emitted by living organisms under natural conditions without external excitation, which falls within the visible and near-ultraviolet range (approx. 200–800 nm) [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9] (

Figure 1.). Although it is not visible to the human eye, it can be detected and characterized with sufficiently sensitive detectors. Several research groups [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14] have begun to conduct research on the ultra-weak photon emission of biological systems by the use of ultra-low noise, highly sensitive photon counting systems.

Figure reproduced without modification from: Ankush Prasad & Pavel Pospíšil, Towards the two-dimensional imaging of spontaneous ultra-weak photon emission from microbial, plant and animal cells, Scientific Reports 3, 1211 (2013)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

The first systematic observations of photon emission are attributed to Alexander Gurwitsch, who discovered in the 1920s that cells emit light at certain stages of development, which can induce the division of other cells. He called this phenomenon "mitogenic radiation [

15]." The concept was controversial for a long time, but in the 1970s, Fritz-Albert Popp and his colleagues used new measurement techniques to confirm that living cells do indeed produce ultra-weak photon emission, and they hypothesized that this emission could be interpreted as a coherent quantum process [

11]. Biophoton emission has now been observed in many cell and tissue types, including plants, animals, bacteria, and human cell lines [

7,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. The emission is typically associated with oxidative biochemical reactions (e. g., the formation of reactive oxygen species) and is sensitive to various physiological and pathological processes.

A growing body of research suggests a potential biological role for photon emission, including intra- and intercellular communication, regulation of cellular processes, and fine-tuning of environmental responses. In addition, quantum biological interpretations have emerged suggesting that photon fields, coherent radiation, and quantum fluctuations may also operate in cells, promoting self-organization and communication.

The aim of this review is to:

Systematize the biochemical and biophysical basis of biophoton emission.

Present the experimental methods currently in use and their limitations.

Evaluate quantum biological theories and their empirical basis.

Review the possibilities of cell-level and intercellular light-based communication.

Present scientific evidence for photon emission as a means of DNA communication.

Identify currently open questions and suggest directions for further research.

2. Biological Mechanisms of Photon Emission

2.1. Biochemical Background

Photons emitted by living cells are predominantly by-products of oxidative metabolic processes. According to the most widely accepted explanation, biophoton emission is the result of the relaxation of excited states (e. g., triplet oxygen, singlet oxygen, excimer complexes) generated during redox reactions in cells.

The main sources of photons include:

- -

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as superoxide anion (O₂⁻), hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) or singlet oxygen (¹O₂), which are highly reactive, short-lived molecules [

23,

24,

25,

26].

- -

Products formed during lipid peroxidation, especially malondialdehyde and aldehyde derivatives formed by the oxidation of unsaturated fatty acids [

27].

- -

Protein and DNA oxidation processes, which result in excited molecules and free radicals [

28].

During these processes, chemical energy creates electron-excited states, which release photons in the visible or near-UV range during de-excitation.

The intensity of the emitted photons is extremely low – typically 1–100 photons/s/cm² – and can therefore only be measured under specially shielded conditions and with highly sensitive detectors. The emission is not uniform, but often shows stochastic fluctuations or quasi-periodic patterns.

Numerous studies have observed that the intensity and spectrum of the emission are sensitive to changes at the cellular level: for example, they increase in the case of oxidative stress, apoptosis, cell proliferation, or inflammatory response [

29,

30,

31].

2.2. Photon Emission at the Cellular Level

Photon emission is not uniformly distributed in cells – the main emitting structures include:

- -

Mitochondria, where significant amounts of ROS are generated during oxidative phosphorylation. The mitochondrial electron transport chain can produce intermediates capable of direct photon emission [

32,

33,

34].

- -

Cell membranes and intracellular membrane systems, particularly due to lipid peroxidation, which occurs in membranes [

26,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44].

Popp believed that biophotons may represent a wide frequency range originating from DNA and concentrated in the cell nucleus DNA; accordingly, light can be stored in DNA and released over time [

45].

The emission pattern and intensity are closely related to the metabolic activity, cycle, and stress state of the cell. For example, it has been observed that photon emission increases significantly before cell division or during apoptosis [

46]. It is interesting to note that in some cases, the emission follows rhythmic patterns, suggesting the role of internal oscillators or cyclic cell regulatory systems.

2.3. Open Questions

- -

Which specific molecular reactions are responsible for the highest photon emission? Is it possible to selectively inhibit or enhance these reactions?

- -

To what extent is photon emission cell type-dependent? Are there cell lines that emit light particularly strongly or regularly?

- -

How does the internal architecture of the cell (e. g., the spatial distribution of mitochondria) affect the emission pattern?

- -

Is real-time, spectrally selective mapping of photon emission from cells in vitro and in vivo possible?

3. Experimental Approaches and Challenges

Measuring biophoton emission is a technologically extremely sensitive and complex task, as the emission intensity is several orders of magnitude lower than ambient light or classical fluorescent signals. Accordingly, research is based on high-sensitivity detection, ensuring a dark environment, and precise handling of samples.

3.1. Measurement Techniques

3.1.1. Photon Detection Systems

The most commonly used devices for detecting photon emission are as follows:

- -

Photomultiplier tubes (PMTs):

The most widely used devices for detecting ultra-weak light. They are extremely sensitive to individual photons with low background noise. Their disadvantage is that they typically only allow integrated intensity measurement in a given wavelength range, without spatial resolution [

47,

48].

- -

Cooled CCD cameras (Charge-Coupled Device):

These enable imaging photon emission measurement, allowing the examination of cell- or tissue-specific emission distribution. Deep cooling (e. g., to –80 °C) reduces dark noise. Their disadvantage is their relatively low temporal resolution [

49,

50,

51,

52].

- -

SPAD (Single-Photon Avalanche Diodes):

A newer technology that enables photon-by-photon time-resolved measurement and can be used in small, integrable systems (e. g., cell chips). Their advantage is their excellent time resolution, while their disadvantage is their wavelength-dependent sensitivity [

53].

- -

CMOS (Complementary Metal-Oxide Semiconductor)

A key technological advantage as well as a weakness of sCMOS is that each pixel has its own read-out circuitry which introduces some variance in low-light level imaging and any electron-multiplication. Repeating this process for every pixel leads to a significant variance and increased background noise [

54].

3.1.2. Environmental and Measurement Conditions

- -

Darkroom: Complete exclusion of environmental photons is necessary – often with multi-layer shielding, vibration-free flooring, and thermostatic control.

- -

Calibration: It is important to know the exact dark count and the spectral response of the detector.

- -

Temperature and pH control: Cell metabolism and thus photon emission are extremely sensitive to environmental factors.

3.2. Samples and Experimental Protocols

Typical models for measurements:

- -

In vitro cell cultures: provide a standardized, well-controlled environment. Common models: HeLa, fibroblasts, plant cells.

- -

Isolated cell organelles: e. g., mitochondria or membrane fragments for targeted biochemical analysis.

- -

Tissue samples or whole living organisms (e. g., zebrafish embryos, mouse embryos, Arabidopsis leaves): for studying physiological relevance.

- -

Sample preparation is a critical step: mechanical stress, oxidative environment, or metabolic disturbances can falsely increase emissions.

Challenges and limitations

- -

Low signal-to-noise ratio: Even under ideal conditions, it is difficult to separate true photon emission from background noise.

- -

Lack of standardization: Research groups use different measurement procedures, which makes comparison difficult.

- -

Environmental effects: Temperature, humidity, and electromagnetic noise can affect the accuracy of measurements.

- -

Biological variability: The natural heterogeneity and dynamic state of cells pose a challenge to reproducibility.

4. Quantum Biological Interpretations

The photon emission of living cells was initially treated as a mere biochemical by-product, but some researchers—especially Fritz-Albert Popp et al.—suggested as early as the second half of the 20th century that this phenomenon might be more than passive oxidative noise: cells can actively emit and possibly detect photons, and thus may be capable of quantum-based information transfer within the organism.

4.1. The Coherent Biophoton Theory

According to Popp and his colleagues [

55,

56], biophoton emission is not random noise, but a quasi-coherent electromagnetic field characterized by:

- -

A low-entropy photon field in which the temporal and spatial patterns of photon emission are not completely random.

- -

The photon emission spectrum may also contain monochromatic components, especially during certain physiological processes.

- -

Cells, as quantum oscillators, may be capable of generating light pulses and synchronizing with each other.

Popp interpreted these photons in a manner similar to biological lasers, where molecules present in cells can be collectively excited, and emission can be induced. This idea is consistent with the concepts of quantum optical coherence and superradiance.

4.2. Quantum Coherence and Quantum Information in Living Systems

In recent years, quantum biology has become an increasingly widely researched field, particularly due to the following examples:

- -

Photosynthesis: light energy can be transferred in a quantum coherent manner in photosynthetic complexes (e. g., FMO complexes), as confirmed by femtosecond spectroscopy [

57].

- -

Bird navigation: signs of geomagnetic sensing based on quantum spin entanglement have been found in the retina of redstarts [

58,

59].

- -

Smell: according to some theories, odor molecules activate receptors through quantum tunneling [

60,

61,

62].

Based on these findings, it has been suggested that biophoton emission may also function as a quantum process, for example:

- -

Photons may function not only as emissions but also as internal communication signals.

- -

Cells may behave as a quantum network, where electromagnetic fields synchronize activity.

- -

Emission may follow nonlinear dynamics, which can also be observed in chaotic or fractal patterns [

46].

4.3. Critical Remarks and Methodological Issues

Although quantum biological interpretations are promising, there are currently a number of challenges:

- -

Coherence time: biological systems operate in a thermal, noisy environment where the duration of quantum coherence is extremely short—typically on the order of picoseconds.

- -

Lack of empirical evidence: few direct measurements confirm coherent biophoton emission. Measurements are sensitive to noise, and statistical processing requires great caution.

- -

Alternative explanations: the observed patterns can often be explained by classical nonlinear systems (e. g., oscillation, stochastic resonance).

- -

Nevertheless, quantum biological interpretations offer important new perspectives for the study of living systems. To move forward, multidisciplinary experimental protocols combining quantum optical, biophysical, and biochemical methods are needed.

5. Light-Based Communication at the Cellular and Intercellular Levels

Biophoton emission can be interpreted not only as a by-product of the metabolic state of cells, but also, based on numerous experimental results, as an information carrier. According to this idea, cells may be capable of photon-based communication, either at the intracellular or intercellular level. This phenomenon raises the possibility of a new type of non-molecular signal transmission channel.

5.1. Intracellular Light Signals

Intracellular photon emission is mainly associated with the following structures:

- -

Mitochondria: Reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated during cellular respiration and their chemical reactions can lead to the emission of photons. These "internal light points" may also encode temporal and spatial patterns of intracellular activity [

63].

- -

Microtubules: According to some theories, the internal hollow structure of microtubules may be capable of photon conduction, acting as "biological optical fibers" [

64]. This is also related to models of consciousness based on quantum theory [

65].

- -

Certain forms of light sensitivity have also been demonstrated in cells without photoreceptors, such as light-induced calcium waves or the activation of other secondary messengers [

66,

67].

5.2. Intercellular Photon Communication

Numerous experiments support the idea that communication between cells can occur not only through chemical signals, but also through weak light signals. Examples:

- -

Gurwitsch's mitogenetic radiation (1920s): long-distance light signaling between the apical regions of onion bulbs, which may have induced cell division.

- -

Kobayashi et al. [

46]: non-chemical interactions between different plant cell cultures were demonstrated, which were reduced by optical shielding.

- -

In higher-order systems (nervous system, immune system), some studies suggest that coordinated cell activity may be partly light-based – this may be particularly interesting at the level of neuromodulation, neurocommunication, and cell division, for example [

68,

69,

70].

5.3. Possible Mechanisms

Two key conditions are necessary for light-based communication between cells:

- -

Emission: The emitter cell is capable of emitting photons in a controlled manner, either in response to environmental stimuli or according to internal rhythms.

- -

Detection: The receiving cell detects the photons and responds functionally based on these signals. This can be activation via receptors or membrane proteins, or even modification of intracellular signaling pathways.

Presumably, photons can also function in a paracrine, autocrine, or endocrine-like manner, although the latter is questionable due to the low light intensity.

5.4. The Question of Photon Patterns and Information Content

- -

The photons emitted by cells can carry information not only based on their quantity, but also on temporal fluctuations (pulsation, oscillation), spectral characteristics (wavelength dispersion, bands), polarization, and other quantum characteristics. Experimental results show that certain photon patterns may be unique to a cell line, developmental stage, or stress state [

71]. This information encoding is similar to classical electrical activity patterns (e. g., EEG, action potentials), but occurs with a photonic signal.

6. Present Scientific Evidence for Photon Emission as a Means of DNA Communication

Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) is a complex molecule belonging to the group of nucleic acids that stores genetic information. The structure of DNA allows for the stable storage of information, its accurate duplication and its transmission to offspring as hereditary material. The transmission of biological information from one generation to the next is made possible by the hereditary material itself, which is essential for the survival of the species.

Today's experimental biology, the understanding and application of the molecular functioning of living systems, is undergoing a huge change. The most important driving force for this is the introduction of the genomic approach. Genomics means genome-scale biology, meaning that studies can extend to the DNA-level or expression (mRNA and/or protein) analysis of all genes of a given organism.

The basis of molecular biology is the central dogma itself, that is, the direction of genetic information flow, is as follows: DNA → mRNA → protein → trait. The central dogma includes transcription (i.e. transcription: DNA → mRNA) and translation (i.e. translation: mRNA → protein). Over the past seven decades, much of the research has focused on the mechanisms of formation of biomolecules responsible for the structure and function of cells. Researchers have mainly studied the function of a single selected gene.

Thanks to this research, our knowledge about the structure and function of DNA has increased tremendously, but our knowledge is mostly based on the results of biochemical research. Despite the fact that ECG, EEG and EMG are widely used not only in research but also in clinical routine, and even the fantastic development of imaging diagnostics has made the use of the results of physics and biophysics as an everyday possibility, we have less faith in this knowledge when it comes to interpreting the basic functioning and functions of cells.

The Interaction Between Photon Emission and DNA

Traditionally, it has been thought that macromolecules found in living cells, including DNA, RNA, and proteins, do not exhibit specific light emission. However, recent research challenges this concept by demonstrating that under certain conditions and at physiological temperatures, nucleic acids exhibit spontaneous light emission. Through non-invasive observation of barley genomic DNA and advanced statistical physical analyses, temperature-induced dynamic entropy fluctuations and fractal dimensional oscillations were identified at a key organizational threshold. The study found evidence of non-equilibrium phase transitions, a noticeable photovoltaic current jump at zero bias, and a proportional increase in photoinduced current with increasing DNA quantity. These results suggest that DNA is one of the main sources of ultra-weak photon emission in biological systems [

72].

DNA is the carrier of genetic information. DNA forms complex three-dimensional structures through complementary base pairs, whose outstanding feature is high-density information storage—based on its physical dimensions. The theoretical data density of DNA is 6 bits per 1 nm of polymer, or ∼4.5×107 GB/g [

73,

74]. Therefore, research into the properties of DNA molecules is crucial for biological questions and their application in various industries.

Using Gurwitsch's findings, Vlail Kaznacheyev conducted thousands of experiments, the results of which were published in book form in 1981 [

75]. The experiments showed that cell information can be transmitted electromagnetically and induced in target cells that absorb photon radiation. In the basic experiment, two sealed quartz containers containing the same cell cultures were separated by a thin optical quartz window. One sample was divided into equal parts, and both halves were placed in the two halves of the device, with only a thin optical window visible between them. Thus, the two containers were completely isolated from the environment, except for the optical connection. The cells in one sample were exposed to ionizing radiation, which destroyed them. The cells in the unirradiated culture also died within 12 hours. It was assumed that photons from the irradiated cells, which were absorbed by the cells in the unirradiated culture, caused their death. In another experiment, they used mouse fibroblasts and adult human microvascular endothelial cells, Caco-2 cell lines, and single-celled green algae (Chlamydomonas reinhardtii), all of which exhibited similar optical biocommunication.

Fritz-Albert Popp discovered a broader spectrum of ultra-weak photon emissions (∼10−3 eV) emitted by living cells, ranging from 200 to 800 nm. He coined the term "biophoton" for these [

76]. According to Popp et al. [

45], a biophoton is a non-thermal photon in the visible and ultraviolet spectrum emitted by a biological system. Popp found that biophotons are coherent and suggested that they may regulate all life processes in an organism [

77]. Biophotonic signal transmission can be used to receive, transmit, and process electromagnetic data, perhaps with some transmission characteristics similar to fiber optics. Popp believed that biophotons may represent a wide frequency range originating from DNA and concentrated in the cell nucleus DNA; accordingly, light can be stored in DNA and released over time [

45]. He concluded that biophotons communicate instantaneously with all cells in the body in a synchronous wave of information energy [

77].

DNA, as the primary carrier of genetic material, is directly linked to the phenomenon of biophoton emission. The structure of DNA is particularly sensitive to photons and can even be damaged by them, but according to certain theories, they can also serve to transmit information within cells. DNA can be not only a target but also a source of biophoton emission. Experiments have confirmed that isolated DNA molecules are also capable of emitting photons, especially under stress or when exposed to external electromagnetic fields. According to some research, DNA may also act as a kind of quantum antenna that resonates at certain frequencies.

Quantum biology assumes that biophoton emission is not merely a by-product of metabolic processes, but part of cell-level communication, and even "light-based" information exchange between cells. This light-based communication can be extremely coherent, similar to laser light, which differs from random thermal light emission.

Biophotons may represent complex communication between cells based on the speed of light. The physics of light seems to fit biological observations. Light is the most efficient and fastest carrier of information in the world. The coherent nature of biophotons may have a profound effect on information transfer. Frequency encoding allows light to encode information from DNA in biophotons. An optical resonator is necessary to store light in a very small, enclosed space. The ability to trap photons and slow down the propagation of light plays an important role in quantum optics [

78]. The twisting of the light beam can form a propagating spiral pattern that may be capable of reading and encoding parts of DNA and transmitting vast amounts of data [

79].

More than fifty years ago, Herbert Fröhlich introduced the concept of long-range coherence in biological systems [

80,

81,

82]. Synchronous, large-scale collective Fröhlich oscillations represent photon emission between cells, which is neither a chemical nor a thermal interaction. Based on this, the oscillations of the DNA molecule emit energy, reaching coherent oscillation in the critical state. In addition, the spectroscopic properties of the Fröhlich condensate are particularly evident in the narrow linewidth. This ensures long-lived coherence and collective motion of the condensate [

83].

Although it has been reported that stochastic fluorescence changes can occur in nucleic acids under the influence of visible light [

84], there is no mention in the scientific literature of natural light emission from nucleic acids. This may be due to the fact that the emission of energy quanta can only be detected under certain conditions and only glows for a very short time when the appropriate physical and chemical conditions are present in the body. Therefore, it is likely that previous observations were unsuccessful because the DNA molecule spent most of its time inactive.

The question arises: why does DNA emit light? The answer is that the light emitted by DNA can be used for energy transfer. This enables the simultaneous transfer of information in the immediate vicinity of DNA molecules, which presumably regulates the coherent development and functioning of living organisms. In addition, it can trigger a signal transmission cascade that initiates growth in the DNA world under favorable environmental conditions.

7. Summary of Our Own Research

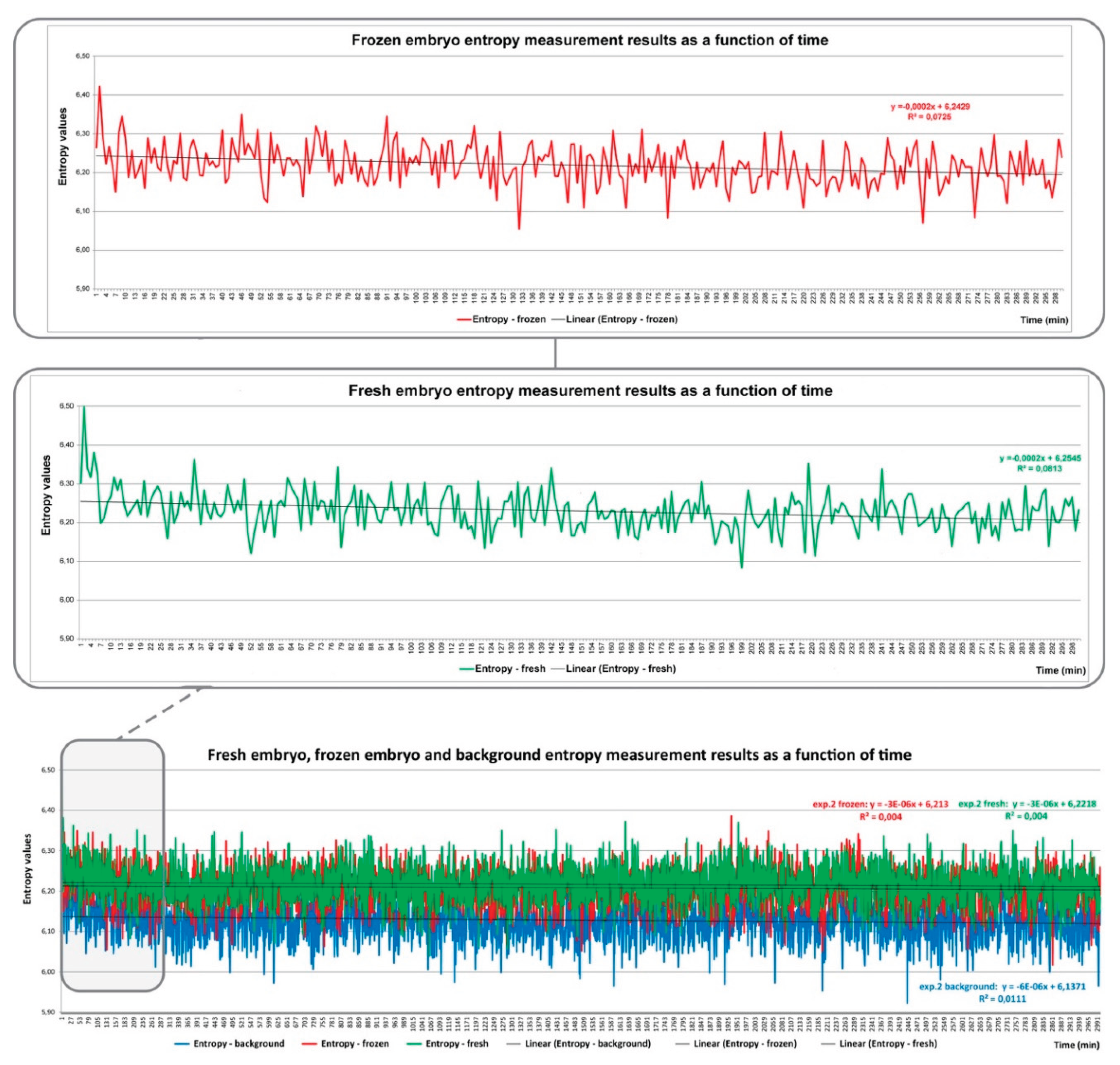

Over the past half century, in vitro fertilization (IVF) has undergone significant development and has now become part of everyday medical practice. During the procedure embryo development can be monitored excellently using TimeLapse technology, but this system uses visible light, which can damage cells. All living cells, including embryos, spontaneously emit photons (UPE) generated by metabolic reactions and influenced by physiological conditions. We hypothesized that this phenomenon could be used to monitor embryo development without any other stimulation, in a "stress-free" environment.

During our investigations, we detected photons emitted by mouse embryos using a combined system of an ORCA-Quest CMOS camera (Hamamatsu Ltd.) and a microscope incubator. The recordings were made in the dark. Reference measurements showed only negligible differences between empty and nutrient-filled samples. It has been observed that the UPE values of degenerated two-cell stage embryos were significantly lower than those of well-developed embryos. The UPE values of freshly conceived embryos were significantly higher than those of previously frozen and then thawed embryos, but visibly well developing embryos. On the basis of results we suggested that UPE detection in mouse embryos may provide a realistic basis for the development of a photon emission embryo control system (PEECS), which we have been working on ever since [

85,

86].

The

Figure 2. shows the results of measurements based on average information content - information theoretical Shannon entropy - [

86]. The total measurement duration is 50 hours (bottom graph of the figure), of which the middle and upper parts contain the measurement results of 5 hours. The temporal change of the entropy curves of fresh and frozen embryos shows a different structure. Several possibilities have been proposed as an explanation for this. It may refer to the previously mentioned complex biochemical and biophysical processes of embryo metabolism, but it can also be considered, in an information theoretical sense, as the communication of two independent systems. Clarifying all of this is part of our own research.

Fresh and frozen embryo entropy values are presented separately.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

8. Future Research Directions

The ultra-weak photon emission of living cells is an exciting and multidimensional phenomenon that fundamentally affects biological organization, cellular information processing, and even the quantum physical interpretation of life. Although many important observations have been made in recent decades, the functional significance, mechanism, and information content of the phenomenon remain unclear. Among the theoretical models proposed so far, the concept of a coherent biophoton field and cells as quantum oscillator networks stands out, in which the detection of temporal synchronization of cell cultures based on photon emission and the identification of fractal or nonlinear dynamics in emission patterns (e. g., recurrence analysis, detection of chaotic dynamics) appears particularly promising. Numerical modeling with quantum-inspired oscillator networks (e. g., modification of the Kuramoto model with quantum parameters) may represent one of the greatest challenges and opportunities of our time. R. Riera Aroche et al [

89] described how DNA behaves like a quantum computer, defining the quantum states that form the qubit. Josephson-Junction qubits are one of the most promising platforms for quantum computation. This future is not far off.

The question of photonic communication between cells remains open. The aim of these studies is to determine whether cells are capable of recognizing light emitted by other cells, responding functionally to it, and encoding/timing light-based information.

9. Conclusions

Biophotons are generated at the atomic and/or molecular level, and we believe that they perform a well-defined task. At the same time, when we examine and analyze the photon emission of certain physiologically important molecules, especially DNA, we attempt, with varying degrees of success, to evaluate the aggregate data from the atomic/molecular spectrum and the curves generated from them. Therefore, we are convinced that the results of various scientific studies should be interpreted as mosaics of a large information system and summarized into a unified and understandable system. If we consider that more than seventy years passed between the discovery of the first nucleic acid in white blood cells and the recognition of the structure of DNA in its current sense, then we must be patient in exploring the real background of photon emission and correctly interpreting the data obtained.

The ultra-weak photon emission of cells, especially the emission mechanisms linked to DNA and their role in communication, remains a challenging but promising area of research. Based on the current literature, there is no convincing empirical evidence that DNA functions as a biophotonic communication system. However, the hypotheses are noteworthy in that they open up new perspectives on the interpretation of biological information processing and cell organization mechanisms [

90,

91,

92].

The study of DNA photonic activity is not only interesting from a biophysical point of view, but may also contribute to:

- -

understanding coherent processes at the cellular level,

- -

broadening the toolkit of quantum biology,

- -

and, in the long term, exploring the physical dimensions of biological information processing.

Highly sensitive quantum optical methods and rigorous experimental protocols are necessary for progress in this field of research. In addition, openness to speculative models, combined with critical thinking and verifiability, is essential to ensure that this field avoids the pitfalls of pseudoscience while becoming a source of new scientific discoveries.

We would like to conclude our manuscript with a thought from 1941 by Hungarian Nobel Prize winner Albert Szent-Görgyi [

93], but rewritten for today: towards the new quantum biology?

Acknowledgments

Project no. RRF-2.3.1-21-2022-00012, titled National Laboratory on Human Reproduction has been implemented with the support provided by the Recovery and Resilience Facility of the European Union within the framework of Programme Széchenyi Plan Plus.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Steven H D Haddock 1, Mark A Moline, James F Case. Bioluminescence in the sea. Ann Rev Mar Sci. 2010, 2, 443–93. [CrossRef]

- E. A. Widder, Bioluminescence in the Ocean: Origins of Biological, Chemical, and Ecological Diversity, Science. 2010.

- Marieh B Al-Handawi, Srujana Polavaram, Anastasiya Kurlevskaya, Patrick Commins, Stefan Schramm, César Carrasco-López, Nathan M Lui, Kyril M Solntsev, Sergey P Laptenok, Isabelle Navizet, Panče Naumov Spectrochemistry of Firefly Bioluminescence. Chem Rev. 2022, 122, 13207–13234. [CrossRef]

- Niggli, H.J. Ultraweak photons emitted by cells: biophotons. J Photochem Photobiol B. 1992, 14, 144–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devaraj, M. , and P. Martosubroto (Eds). 1997. Small Pelagic Resources and their Fisheries in the Asia-Pacific region. Proceedings of the APFIC.

- R Vogel , R Süssmuth. Low level chemiluminescence from liquid culture media. J Appl Microbiol. 1999, 86, 999–1007. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niggli, H.J. Temperature dependence of ultraweak photon emission in fibroblastic differentiation after irradiation with artificial sunligIndian J Exp Biol. 2003, 41, 419–23.

- Joseph Tafur, M.D. ,1 Eduard P.A. Van Wijk, Ph.D.,2,3 Roeland Van Wijk, Ph.D.,2,4 and Paul J. Mills, Ph.D. Biophoton Detection and Low-Intensity Light Therapy: A Potential Clinical Partnership. Photomedicine and Laser Surgery Volume 28, Number 1, 2010 ª Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. Pp. 23–30. [CrossRef]

- Ankush Prasad & Pavel Pospíšil. Towards the two-dimensional imaging of spontaneous ultra-weak photon emission from microbial, plant and animal cells. Scientific Reports 2013, 3, 1211.

- Yan, Z. Zhang X. Preliminary study of the human body surface photon emission. Prog. Biochem. Biophysics 1979, 2, 48–52. [Google Scholar]

- Popp et al., Popp FA, Nagi W, Li KH, Scholz W, Weingartner O, Wolf R. Biophoton emission. New evidence for coherence and DNA as source. Cell Biophys. 1984, 6, 33–51. [CrossRef]

- Enrique Cadenas, Helmut Siesi, Ana Campa, Giuseppe Cilento. Electronically Excited States in Microsomal Membranes: Use of Chlorophyll-a As An Indicator of Triplet Carbonyls. Photochemistry and Photobiology. [CrossRef]

- T. I. Quickenden, M. J. T. I. Quickenden, M. J. Comarmond, R. N. Tilbury. Ultra Weak Bioluminescence Spectra of Stationary Phase Saccharomyces cerevisiae And Schizosaccharomyces pombe. 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inaba, H. Super-High Sensitivity Systems for Detection and Spectral Analysis of Ultraweak Photon Emission from Biological Cell Cells and Tissues. Experientia 1988, 44, 550–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A.G. Gurwitsch. Die natur des spezifischen erregers der zellteilung. Dev Genes Evol 1923, 100, 11.

- Laager, F. Light based cellular interactions: hypotheses and perspectives Front. Phys., 2015, 3, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T I Quickenden 1, R N Tilbury Luminescence spectra of exponential and stationary phase cultures of respiratory deficient Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Photochem Photobiol B. 1991, 8, 169–74. [CrossRef]

- Gallep, C.M. and dos Santos, S.R. Photon-Counts during Germination of Wheat (Triticum aestivum) in Wastewater Sediment Solutions Correlated with Seedling Growth. Seed Science and Technology 2007, 35, 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S Cohen , F A Popp. Biophoton emission of human body. Indian J Exp Biol. 2003, 41, 440–5.

- Schwabl H, Klima H. Spontaneous ultraweak photon emission from biological systems and the endogenous light field. Forsch Komplementarmed Klass Naturheilkd. 2005, 12, 84–9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pospíšil, P. Prasad A., Rác M. Mechanism of the formation of electronically excited species by oxidative metabolic processes: role of reactive oxygen species. Biomolecules 2019, 9, E258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, A. Mihačová, E., Manoharan, R.R. et al. Application of ultra-weak photon emission imaging in plant stress assessment. J Plant Res 2025, 138, 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michal Cifra a, Pavel Pospíšil b Ultra-weak photon emission from biological samples: Definition, mechanisms, properties, detection and applications Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology 2014, 139, 2–10.

- Pospíšil P, Prasad A, Rac M. Role of reactive oxygen species in ultra-weak photon emission in biological systems. J Photochem Photobiol B 2014, 139, 11–23. [CrossRef]

- Pospíšil P, Yamamoto Y. Damage to photosystem II by lipid peroxidation products. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj 2017, 1861, 457–466. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A Shanei 1, Z Alinasab 1*, A Kiani 1, MA Nematollahi Detection of Ultraweak Photon Emission (UPE) from Cells as a Tool for Pathological Studies J Biomed Phys Eng. 2017, 7, 389–396.

- Antonio Ayala 1, Mario F Muñoz 1, Sandro Argüelles. Lipid peroxidation: production, metabolism, and signaling mechanisms of malondialdehyde and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2014, 2014, 360438. [CrossRef]

- John, R. Bucher, Oxidative stress and radical-induced signalling IARC Scientific Publications, No. 165. Baan RA, Stewart BW, Straif K, editors. Lyon (FR): International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2019.

- Kaznacheev, A.V.P. Mikhailova, L.P. & Kartashov, N.B. Distant intercellular electromagnetic interaction between two tissue cultures. Bull Exp Biol Med 1980, 89, 345–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michal Cifra 1, Jeremy Z Fields, Ashkan Farhadi. Electromagnetic cellular interactions Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2011, 105, 223–46. [CrossRef]

- Michal Cifra, Christian Brouderb, Michaela Nerudov. Biophotons, coherence and photocount statistics: a critical review. 2015; arXiv:1502.07316v1.

- Bat’yanov A., P. Distant-optical interaction of mitochondria through quartz. Biull Eksp. Biol. Med. 1984, 97, 675–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholkmann, F. Fels D., Cifra M. Non-chemical and non-contact cell-to-cell communication: a short review. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2013, 5, 586–593. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rhys R Mould 1,†,#, Alasdair M Mackenzie 2,†,*,#, Ifigeneia Kalampouka 1, Alistair V W Nunn 1,3, E Louise Thomas 1, Jimmy D Bell 1, Stanley W Botchway 2Ultra weak photon emission—a brief review. Front Physiol. 2024, 15, 1348915. [CrossRef]

- Roland Thar 1, Michael Kühl, Propagation of electromagnetic radiation in mitochondria? J Theor Biol. 2004, 230, 261–70. [CrossRef]

- Craddock T. J., A. Friesen D., Mane J., Hameroff S., Tuszynski J. A. The feasibility of coherent energy transfer in microtubules. J. R. Soc. Interface 2014, 11, 20140677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, A. Pospíšil, P. Linoleic Acid-Induced Ultra-Weak Photon Emission from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii as a Tool for Monitoring of Lipid Peroxidation in the Cell Membranes. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e22345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunn A. V., W. Guy G. W., Bell J. D. Bioelectric fields at the beginnings of life. Bioelectricity 2022, 4, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- N S Dhalla 1, R M Temsah, T Netticadan Role of oxidative stress in cardiovascular diseases. J Hypertens. 2000, 18, 655–73. [CrossRef]

- Rusty Rodriguez and Regina Redman (2005) Balancing the generation and elimination of reactive oxygen species PNAS. [CrossRef]

- Philip Newsholme 1, Vinicius Fernandes Cruzat 1 2, Kevin Noel Keane 1, Rodrigo Carlessi 1, Paulo Ivo Homem de Bittencourt Jr Molecular mechanisms of ROS production and oxidative stress in diabetes. Biochem J. 2016, 473, 4527–4550. [CrossRef]

- Prasad, S. , Gupta S. C., Tyagi A. K. (2017). Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and cancer: Role of antioxidative nutraceuticals. Cancer Lett. 387, 95–105. [CrossRef]

- Phull A., R. Nasir B., Haq I. U., Kim S. J. Oxidative stress, consequences and ROS mediated cellular signaling in rheumatoid arthritis. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2018, 281, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sumien et al., 2021 Sumien N., Cunningham J. T., Davis D. L., Engelland R., Fadeyibi O., Farmer G. E., et al. (2021). Neurodegenerative disease: Roles for sex, hormones, and oxidative stress. Endocrinology 162 (11), bqab185. [CrossRef]

- Popp F., A. , Nagl W., Li K. H., Scholz W., Weingärtner O., Wolf R. (1984). Biophoton emission - new evidence for coherence and DNA as source. Cell Biophys. 6, 33–52. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, M. , Takeda M., Sato T., Yamazaki Y., Kaneko K., Ito K. I., Kato H., Inaba H. (1999): In vivo imaging of spontaneous ultraweak photon emission from a rat‘s brain correlated with cerebral energy metabolism and oxidative stress. Neurosci. Res. 34, 103–113. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, M. Sasaki K., Enomoto M., Ehara Y. Highly sensitive determination of transient generation of biophotons during hypersensitive response to cucumber mosaic virus in cowpea. J. Exp. Bot. 2006, 58, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Photonis (2002). Photomultiplier tube basics. Available online: https://psec.uchicago.edu/library/photomultipliers/Photonis_PMT_basics.pdf (accessed on 11 April 2023).

- Chen Y., S. Chen B. T. 2003 Measuring of a three-dimensional surface by use of a spatial distance computation, Applied Optics, 42 11 1958 1972.

- Lijian Zhang, Leonardo Neves, Jeff S Lundeen and Ian A Walmsley. A characterization of the single-photon sensitivity of an electron multiplying charge-coupled device Journal of Physics B: Atomic, Molecular and Optical Physics , Volume 42, Number 11.

- Saeidfirozeh, H. , Shafiekhani, A., Cifra, M. et al. Endogenous Chemiluminescence from Germinating Arabidopsis Thaliana Seeds. Sci Rep 8, 16231 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Khaoua, I. , Graciani, G., Kim, A. et al. Detectivity optimization to measure ultraweak light fluxes using an EM-CCD as binary photon counter array. Sci Rep 11, 3530 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Christian Kurtsiefer1, Markus Oberparleiter1, and Harald Weinfurter1,2 High-efficiency entangled photon pair collection in type-II parametric fluorescence. Phys. Rev. A 64, 023802 – Published 2 July, 2001.

- Rhys R Mould 1,†,#, Alasdair M Mackenzie 2,†,*,#, Ifigeneia Kalampouka 1, Alistair V W Nunn 1,3, E Louise Thomas 1, Jimmy D Bell 1, Stanley W Botchway Ultra weak photon emission—a brief review Front Physiol. 2024 Feb14;15:1348915. [CrossRef]

- Popp, F.-A. (1979) Photon Storage in Biological Systems. In: Popp, F.-A., Becker, G., Koenig, H.L. and Peschka, W., Eds., Electromagnetic Bio-Information, Urban & Schwarzenberg, Munich, 123-148.

- Fritz-Albert Popp Properties of biophotons and their theoretical implications Indian J Exp Biol. 2003, 41, 391–402.

- Engel, G. , Calhoun, T., Read, E. et al. Evidence for wavelike energy transfer through quantum coherence in photosynthetic systems. Nature 446, 782–786 (2007). [CrossRef]

- Thorsten Ritz Quantum effects in biology: Bird navigation. Procedia Chemistry Volume 3, Issue 1, 2011, Pages 262-275.

- R. A. Holland True navigation in birds: from quantum physics to global migration Journal of Zoology. 2014. [CrossRef]

- S M Sagar 1, R J Thomas, L T Loverock, M F Spittle. Olfactory sensations produced by high-energy photon irradiation of the olfactory receptor mucosa in humans. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1991, 20, 771–6. [CrossRef]

- Anashe Bandari Human smell perception is governed by quantum spin-residual information. Scilight News 2019 Volume 2019, Issue 30. [CrossRef]

- Willeford, K. The Luminescence Hypothesis of Olfaction. Sensors (Basel). 2023, 23, 1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Karu, T. Primary and secondary mechanisms of action of visible to near-IR radiation on cells. J Photochem Photobiol B. 1999, 49, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mari Jibu, Kunio Yasue, Scott Hagan Evanescent (tunneling) photon and cellular ‘vision’ BioSystems 42 (1997) 65–73.

- Hameroff, S. and Penrose, R. (1996) Orchestrated Reduction of Quantum Coherence in Brain Microtubules: A Model for Consciousness. Mathematics and Computers in Simulation, 40, 453-480. [CrossRef]

- Kučera O, Cifra M. Cell-to-cell signaling through light: just a ghost of chance? Cell Commun Signal. 2013 Nov 12;11:87. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mould RR, Kalampouka I, Thomas EL, Guy GW, Nunn AVW, Bell JD. Non-chemical signalling between mitochondria. Front Physiol. 2023 Sep 22;14:1268075. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tang, R. and Dai, J. (2014) Biophoton Signal Transmission and Processing in the Brain. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B 139, 71–75. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S. , Boone, K., Tuszyński, J. et al. Possible existence of optical communication channels in the brain. Sci Rep, 2016; 6, 36508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeilpour, T. , Fereydouni, E., Dehghani, F. et al. An Experimental Investigation of Ultraweak Photon Emission from Adult Murine Neural Stem Cells. Sci Rep, 2020; 10, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eduard, P.A. Van Wijk a b, Roeland Van Wijk a, Saskia Bosman a Using ultra-weak photon emission to determine the effect of oligomeric proanthocyanidins on oxidative stress of human skin. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology Volume 98, Issue 3, 8 March 2010, Pages 199-206.

- Pietruszka, M. , Marzec, M. Ultra-weak photon emission from DNA. Sci Rep 14, 28915 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Knappe, G. A. , Wamhoff, E. C. & Bathe, M. Functionalizing DNA origami to investigate and interact with biological systems. Nat. Rev. Mater. 8, 123–138 2022.

- Organick, L.; et al. Probing the physical limits of reliable DNA data retrieval. Nat. Commun. 11, 616,2020.

- Kaznacheev, V.P. and Mihaylova, M.P. (1981) Ultra-Weak Radiations in Intercellular Interactions. Science, Novosibirsk.

- Bischof, M. (2003) Introduction to Integrative Biophysics. In: Popp, F.-A. and Beloussov, L., Eds., Integrative Biophysics, Springer, Dordrecht, 1-115. [CrossRef]

- F. A. Popp, K. H. Li, W. P. Mei, et al., (1988) Physical aspects of biophotons. Experientia, 44, 576-585.

- Tanabe, T. , Notomi, M., Kuramochi, E., Shinya, A., & Taniyama, H. (2007). Trapping and delaying photons for one nanosecond in an ultrasmall high-Q photonic-crystal nanocavity. Nature Photonics, 1(1), 49-52. [CrossRef]

- Feldmann A, Ivanek R, Murr R, Gaidatzis D, Burger L, Schübeler D (2013) Transcription Factor Occupancy Can Mediate Active Turnover of DNA Methylation at Regulatory Regions. PLoS Genet 9, e1003994. [CrossRef]

- Fröhlich, H. Long-range coherence and energy storage in biological systems. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2, 641–649,1968.

- Vasconcellos, Á. R. , Vannucchi, F. S., Mascarenhas, S. & Luzzi, R. Fröhlich Condensate: emergence of Synergetic Dissipative structures in Information Processing Biological and Condensed Matter systems. Information 3, 601–620,2012.

- Nakamura, Y. Pashkin, Y. A. & Tsai, J. S. Coherent control of macroscopic quantum states in a single-Cooper-pair box. Nature 398, 786–788,1999.

- Zhang, Z. Agarwal, G. S. & Scully, M. O. Quantum fluctuations in the Fröhlich Condensate of Molecular vibrations Driven Far from Equilibrium. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 158101, 2019.

- Dong, B.; et al. Superresolution intrinsic fluorescence imaging of chromatin utilizing native, unmodified nucleic acids for contrast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 113, 9716–9721 (2016).

- Berke et al, 2024, Unique algorithm for the evaluation of embryo photon emission and viability Sci Rep. 2024, 14, 15066. [CrossRef]

- Bódis et al. 2024 Detection of ultra-weak photon emissions from mouse embryos with implications for Assisted reproduction Journal of Health Care Communications Volume 9, Issue 4.

- Shannon, C. E. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1948; 27, 623–656. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, C. E. Prediction and entropy of printed English. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1951; 30, 50–64. [Google Scholar]

- Riera Aroche, R. , Ortiz García, Y.M., Martínez Arellano, M.A. et al. DNA as a perfect quantum computer based on the quantum physics principles. Sci Rep 14, 11636 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Popp, F.A. , et al. (1992) Recent Advances in Biophoton Research and Its Aplication. World Scientific, Singapore City, London, New York. [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.H. Lee, J.H. Kim, M.Y. Kim, J.H. Lim, J. Lee Effect of 710 nm visible light irradiation on neurite outgrowth in primary rat cortical neurons following ischemic insult. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 422 (2012), pp. 274–279.

- Van Wijk, R. and Van Wijk, E.P.A. (2005) An Introduction to Human Biophoton Emission. Forsch Komplementärmed Klass Naturheilkd, 12, 77-83. [CrossRef]

- Szent-Györgyi, A. Towards a New Biochemistry? Science. 1941, 93, 609–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).