1. Introduction

The prevalence of hypertension (HTN) and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) continues to steadily increase [

1], significantly contributing to the growing burden of chronic kidney disease (CKD) [

2,

3,

4]. By 2040, CKD is projected to become the fifth leading cause of disability-adjusted life years worldwide [

5]. On May 23, 2025 The World Health Assembly (WHA78) has adopted its first ever resolution focused exclusively on kidney health [

6].Patients with resistant hypertension (RHTN) have particularly poor renal outcomes [

7]. At the same time, the development of CKD itself makes it difficult to control blood pressure (BP), which closes the vicious circle between HTN and CKD, among which 40% of patients have RHTN [

8]. Moreover, as renal function declines, the risk of developing RHTN increases by 1.6-fold in CKD stage G3a and doubles in more advanced CKD stages [

9]. Importantly, T2DM not only increases CKD risk, but also contributes to antihypertensive treatment resistance [

10], partially through renal injury mechanisms. Both HTN and T2DM lead to progressive renal function decline and represent major causes of CKD. According to Polonia et al., patients with HTN or T2DM experience an annual estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) decline of 2-4 mL/min/1.73m² [

11]. Furthermore, therapeutic BP reduction naturally decreases eGFR due to dependence of the latter on filtration pressure, a factor that must be considered when evaluating treatment effects. Thus, the assessment and interpretation of the effects of an antihypertensive treatment on kidney function in patients with HTN and T2DM should take both of these phenomena into account. That is, the null hypothesis for detecting the effect of antihypertensive treatment on kidney function in patients with HTN and T2DM is not a zero change but a non-zero decrease predicted from the known rate of the function decline over time and actual BP lowering effect of the treatment. Likewise, to calculate the magnitude of such an effect, the reference level should be taken, for example, not just the pre-treatment level, but the pre-treatment level minus the reduction expected as a result of the natural progression of renal dysfunction over the given time period and minus the reduction expected as a result of the decrease in BP from baseline.

The pathogenesis of HTN and T2DM shares common mechanisms related to hyperactivity of sympathetic nervous system (SNS) playing pivotal role in the disease progression and development of adverse outcomes [

12,

13] especially renal dysfunction. Excessive stimulation of the adrenoceptors in the kidneys causes renal vasoconstriction and thus the reduction of blood, oxygen supply to the renal tissue while also enhances sodium reabsorption associated with high oxygen consumption. In combination, these effects can cause severe renal tissue hypoxia, extensively shown as a major cause of CKD. A direct correlation exists between increased sympathetic tone and reduced eGFR [

12]. Consequently, SNS has emerged as a therapeutic target not only for HTN but also for CKD, driving the development of neuromodulation technologies, e.g. renal denervation. Renal denervation (RDN) reduced sympathetic hyperactivity [

14], BP [

15] and affects the key pathophysiological mechanisms of RHTN and CKD [

16,

17]. Specifically, RDN blocks the transmission of excessive sympathetic stimuli to the kidneys, which causes sustained vasodilation with a significant increase in renal perfusion, while simultaneously reduces sodium reabsorption and the associated high oxygen consumption. Restoration of renal tissue oxygenation terminates hypoxic damage to renal tissue and the associated progression of renal dysfunction in patients with HTN and T2DM, including those who already have CKD.

The potential nephroprotective effect of RDN has been demonstrated in several studies, including those with T2DM [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. Moreover, patients with CKD may derive even greater benefit compared to those without renal impairment [

23]. Currently, renal denervation is included as a therapeutic option for the management of HTN [

16,

17]. However, most available evidence comes from procedures performed using anatomically suboptimal ablation techniques targeting the main renal artery trunk. Distal renal denervation (dRDN) is the latest version of the therapy, optimized according to the actual anatomical shape of the renal nerve plexuses. It demonstrated a more pronounced antihypertensive effect and thus expected to have a more powerful nephroprotective effect. However, the nephroprotective potential of dRDN may be limited by the increased nephrotoxicity due to the multiple increase in the number of contrast injections, since multiple segmental branches are treated instead of a single renal artery trunk, as well as by the significant BP lowering effect, which naturally compromises renal perfusion.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to test the hypothesis that dRDN prevents progressive kidney function decline in patients with RHTN and T2DM.

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted a single-center prospective interventional study with a 12-month follow-up period at the Research Institute of Cardiology, Tomsk National Research Medical Center (the corresponding study protocol, titled “Distal Renal Denervation to Prevent Renal Function Decline in Patients With T2DM and Hypertension”, REFRAIN, is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov under identifier NCT04948918). All patients provided written informed consent prior to inclusion in the study.

Eligible patients included men and women 20–80 years old with T2DM (glucose tolerance test > 11.0 mmol/l, glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c)>6,5%) and office systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥ 140 mmHg, while receiving three or more antihypertensive medications (one is a diuretic) without changes for 3 months prior to enrollment. The exclusion criteria were pseudo-resistant HTN, secondary HTN, HbA1c > 10%, eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2, pregnancy, renal artery anatomy ineligible for treatment, and severe comorbidity significantly increasing the risk of the intervention according to investigator’s assessment. Renal dysfunction defined as a eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2, or repeated albuminuria ≥30 mg/g creatinine in the spontaneous urine (G3 or G2А2 by KDIGO 2012) [

24].

Office BP measurement according to standard practice and 24-h BP monitoring were performed at baseline and 1 year after the procedure. Variations in the concomitant antihypertensive drug therapy were assessed by the change in the average number of medications taken according to the interview.

Laboratory parameters of renal function were evaluated in all patients included in the study baseline and 1 year after the procedure: serum creatinine, eGFR by using the CKD-EPI formula, serum Lipocalin-2 (neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) (Human Lipocalin 2 ELISA test system (BioVendor Laboratory Medicine, Inc., Czech Republic)), cystatin C blood levels (BioVendor Laboratory Medicine, Inc., Czech Republic), (free metanephrine and normetanephrine in human plasma (MetCombi Plasma ELISA kit (IBL International GMBH, Germany)), HbA1c, 24 hour urine volume, 24 hour urinary excretion of albumin, potassium and sodium, metanephrine and normetanephrine

Renal Doppler flowmetry with calculation of renal resistive index (RRI) [

25] and kidney magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (1.5 Tesla, Titan vantage, Toshiba) were performed baseline and 1 year after RDN. An average value of the RRI was used from the upper, middle and lower segments of the kidney. A detailed description of the MRI protocol was published elsewhere [

26].

2.1. Renal Denervation Procedure

The dRDN was performed using the 6 F Symplicity Spyral catheter, which was sequentially advanced into segmental branches of the renal arteries where the 4 electrodes were deployed in a pre-defined helical pattern and radiofrequency energy was delivered simultaneously to all 4 quadrants of arterial wall circumference in a spiral fashion. The two such treatments in different positions were done in each segmental branch. If the branch was too short, the treatment was applied across the bifurcation.

2.2. Study Endpoints

The primary study outcome was change in eGFR from baseline to 12 month.

The secondary outcomes included efficacy and safety endpoints. Efficacy endpoints were changes after 12 months in: office BP levels (systolic/diastolic); 24-hour BP (24-h mean, daytime, nighttime; systolic/diastolic); cystatin C blood levels; NGAL blood levels; 24-hour urinary albumin excretion urinalysis; cortical and medullary volume of the kidneys and their ratio according to MRI (cortical and medullary volume measured using magnetic resonance imaging); RRI in a trunk and segmental renal arteries; peak linear blood flow velocity in the trunk and in segmental renal arteries blood. The safety endpoints were acute kidney injury incidence and major adverse renal events: the new-onset kidney injury (persistent albuminuria/proteinuria and/or sustained reduction in eGFR to <60 mL/min/1.73 m²), progression to end-stage kidney disease (eGFR <15 ml/min/1·73 m2), renal-related mortality (death attributable to kidney failure or dialysis-associated complications) were assessed over the entire study period.

The secondary analysis encompassed a comparative evaluation of patient subgroups stratified by the magnitude of antihypertensive response to the intervention, alongside an exploration of determinants modulating renal functional changes following dRDN. Given that renal perfusion is intrinsically dependent on systemic BP, and excessive BP reduction may compromise kidney function [

27], a supplementary analysis was performed. Patients were retrospectively stratified into responders and non-responders based on the magnitude of BP reduction at 12 months after dRDN. Responders were defined as individuals achieving a ≥10 mmHg reduction in 24-hour ambulatory systolic BP (24h SBP). Furthermore, responders were subclassified into two subgroups: moderate responders (10–20 mmHg reduction in 24h SBP) and super-responders (>20 mmHg reduction in 24h SBP).

А multiple linear regression analysis was performed to find the factors influencing the change of renal function after dRDN. The model included HbA1c, age, sex, baseline eGFR, and 24h SBP as dependent variables whereas eGFR change was used as dependent variable.

The study was carried out using equipment from the Medical Genomics Center of Collective Use of the Tomsk National Research Medical Center.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Statistica 10.0 ver. for Windows and SPSS 26 were used for the statistical analysis. The significance of differences in categorical variables was tested using Fisher’s exact test. The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to test the hypothesis of a normal distribution of continuous variables. Between-group differences were tested using unpaired t-tests for normally distributed variables and the Mann–Whitney U test otherwise. Within-group differences in repeated measures were assessed using paired t-test. The association between variables was assessed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r). Depending on the nature of renal function estimate as a continuous variable expressed by rational numbers. Multiple linear regression analysis was performed to identify predictors of the development of the analyzed effects. The 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated to assess the size of the treatment effects according to the International Conference on Harmonization E9 Guideline: “Statistical Principles for Clinical Trials”. Analyses were performed based on the per-protocol principle. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

The baseline clinical and demographic characteristics of the study cohort are presented in

Table 1. The overall cohort comprised patients aged over 60 years, with a female predominance. The majority have both general and abdominal obesity, along with comorbid coronary artery disease and peripheral atherosclerosis. Nephropathy was documented in 79% of patients.

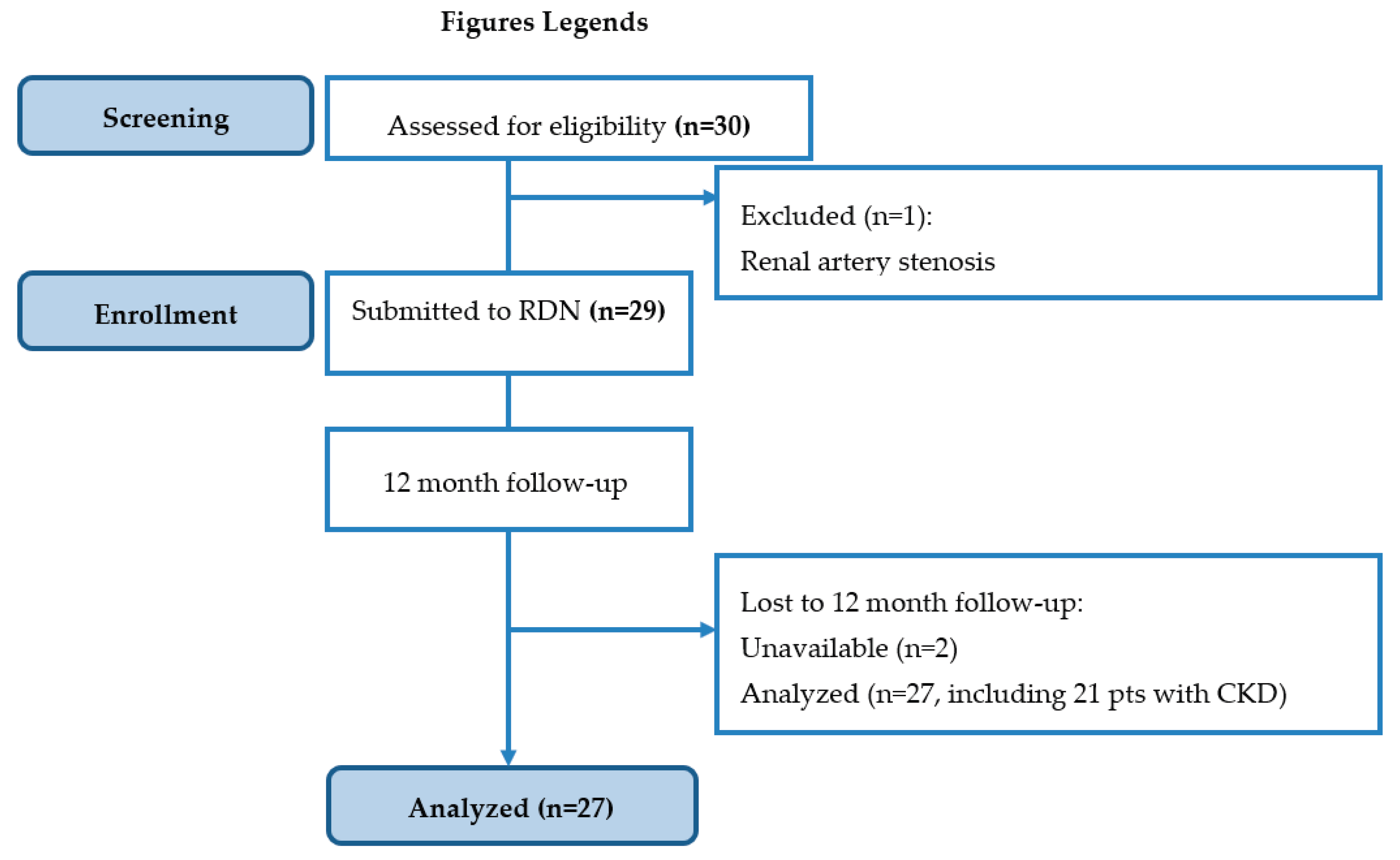

A total of 29 subjects were finally enrolled in the study and undergone dRDN.

Figure 1 summarizes the recruitment process and patient journey.

Baseline antihypertensive and concomitant medication prescription is shown in

Table 2. All patients were taking statins

3.2. Safety

The technical success of the procedure (at least 4 full-time applications of radiofrequency energy performed on each side) was 100%. Intraprocedural angiography revealed no significant vascular injuries to the renal arteries or their branches. No safety concerns, perioperative complications, or instances of acute kidney injury were observed during the study period.

3.3. Primary Endpoint Analysis

No significant changes in eGFR were observed in the study group at one year post-dRDN compared to baseline (Δ = 1.3 mL/min/1.73m² [95% CI: -9.6; 12.1], p = 0.824).

3.4. Secondary Endpoint Analysis

3.4.1. Assessment of Antihypertensive Efficacy

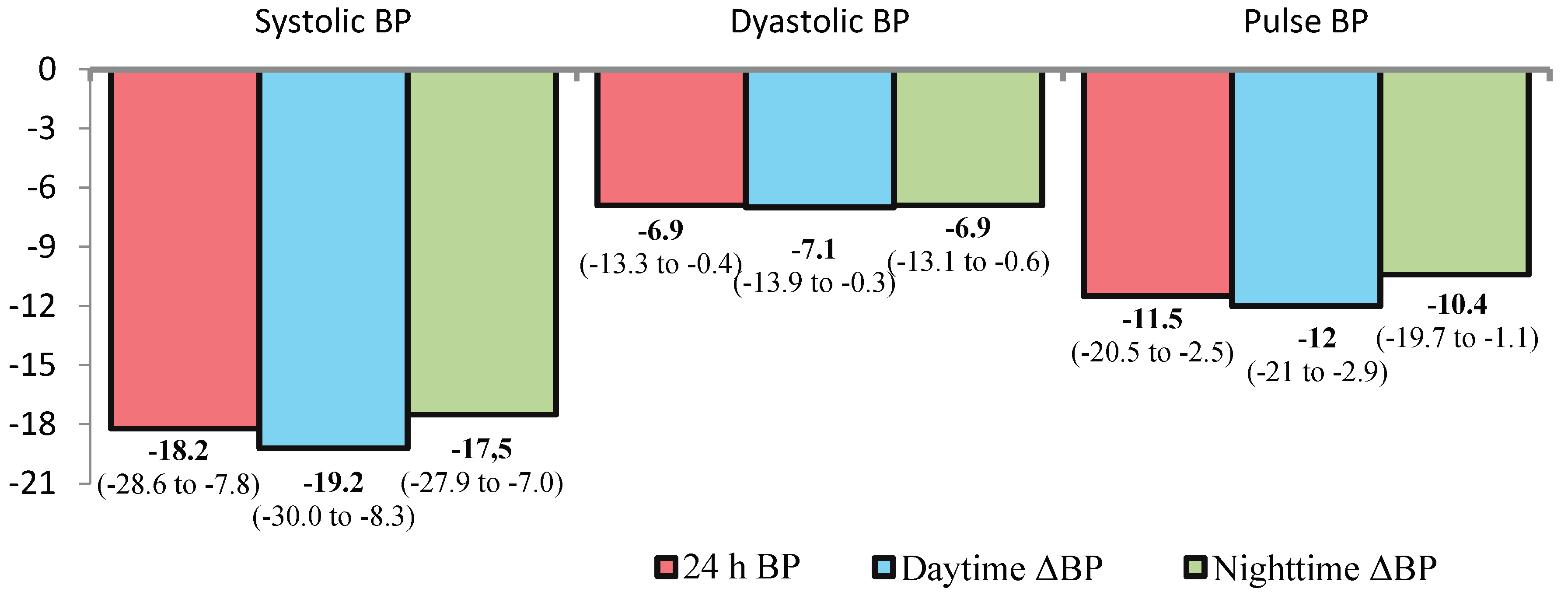

At 12 month after dRDN, significant reductions in office BP, 24-hour ambulatory BP, pulse pressure (PP), and systolic BP variability were observed (

Figure 2). The frequency of elevated pulse pressure (>60 mmHg) decreased by 1.9-fold, from 79% (n=23) to 41% (n=12) (p=0.007).

Target office BP levels (<140/90 mmHg) were achieved in 12 patients (44%).Analysis of changes in structural-functional renal parameters is presented in

Table 3.

3.4.2. Retrospective Comparison of Outcomes in Groups with Mild and Strong BP Lowering Effect

The proportion of responders (defined as ≥10 mmHg reduction in 24-hour systolic BP) was 63% (n=17). Among these, 11 patients (41%) achieved a >20 mmHg reduction in 24-hour systolic BP, constituting the super-responder subgroup. The frequency of elevated PP (>60 mmHg) decreased by 1.9-fold, declining from 79% (n=23) to 41% (n=12) (p=0.007). Subgroup analyses comparing responders and non-responders are presented in

Table 4. No significant differences in these parameters were observed between the subgroups.

It is noteworthy that the proportion of patients with CKD was comparably high in both responder and non-responder groups (n=14 [82.4%] vs. n=7 [70%], respectively). No significant differences in eGFR changes were observed based on the magnitude of BP reduction—categorized as 10–20 mmHg (moderate responders) or >20 mmHg (super-responders) (−0.6 ± 11.4 vs. −2.4 ± 12.5, p= 0.758). Given the study population (patients with DM) and the sympatholytic mechanism of the intervention, we further evaluated trends in glucose metabolism and catecholamine levels (

Table 5). No significant alterations in these parameters were detected.

3.4.3. Factors Influencing the Nephroprotective Effect dRDN

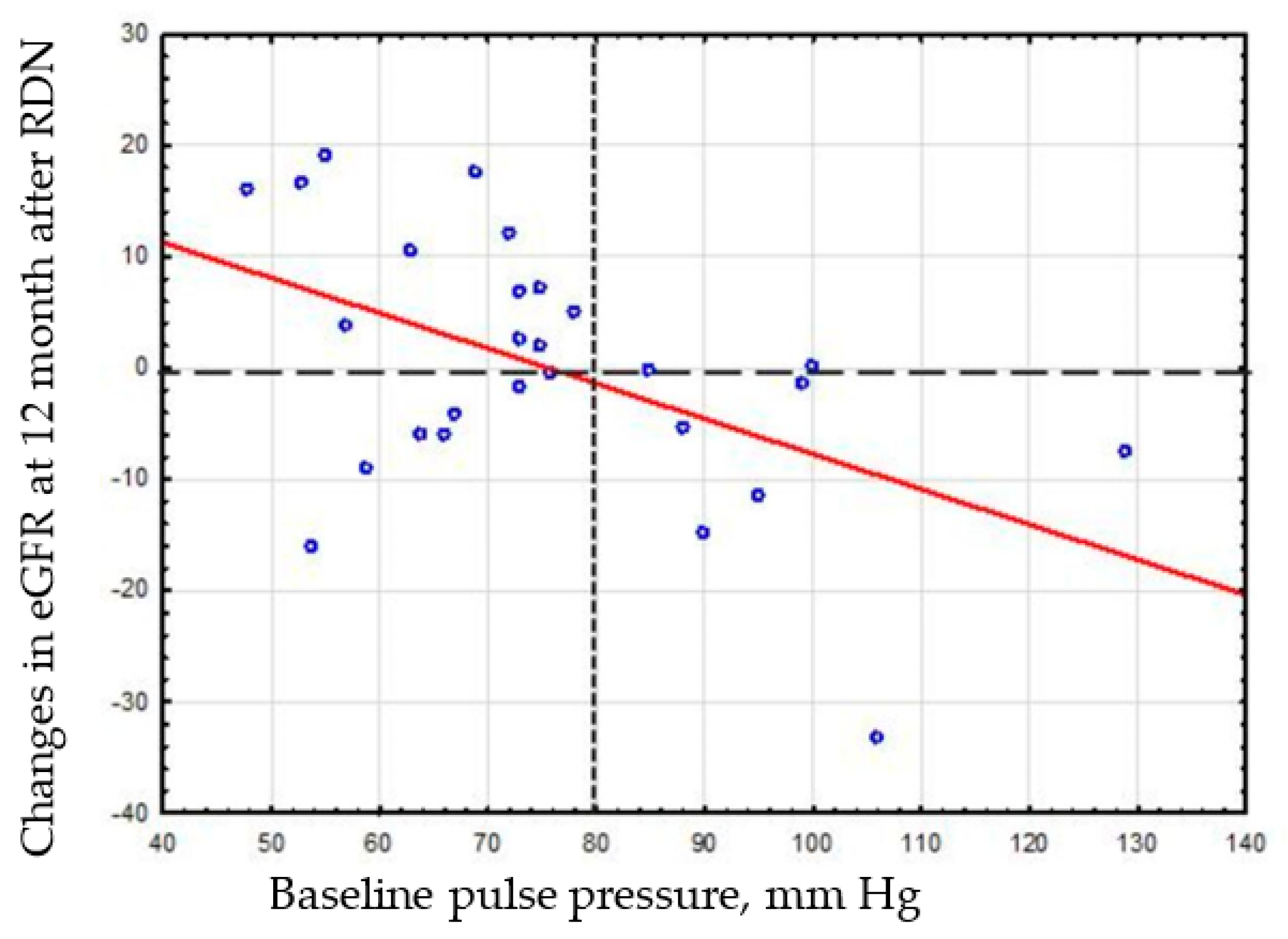

Multivariate regression analysis (

Table 6) identified baseline HbA1c and PP as independent predictors of eGFR changes at 12 months post-RDN. Lower baseline HbA1c and PP levels were associated with greater improvement in eGFR following the intervention.

Based on visual analysis of the correlation matrix of the relationship between PP and eGFR change (

Figure 3), we decided to compare the eGFR change in patient subgroups stratified by baseline PP (≥80 mmHg vs. <80 mmHg).

The wide dotted line indicates conditional division of patients with and without nephroprotective effect. Frequent dotted line indicates conditional division of patients into subgroups stratified by baseline PP (<80 mmHg vs. ≥80 mmHg).

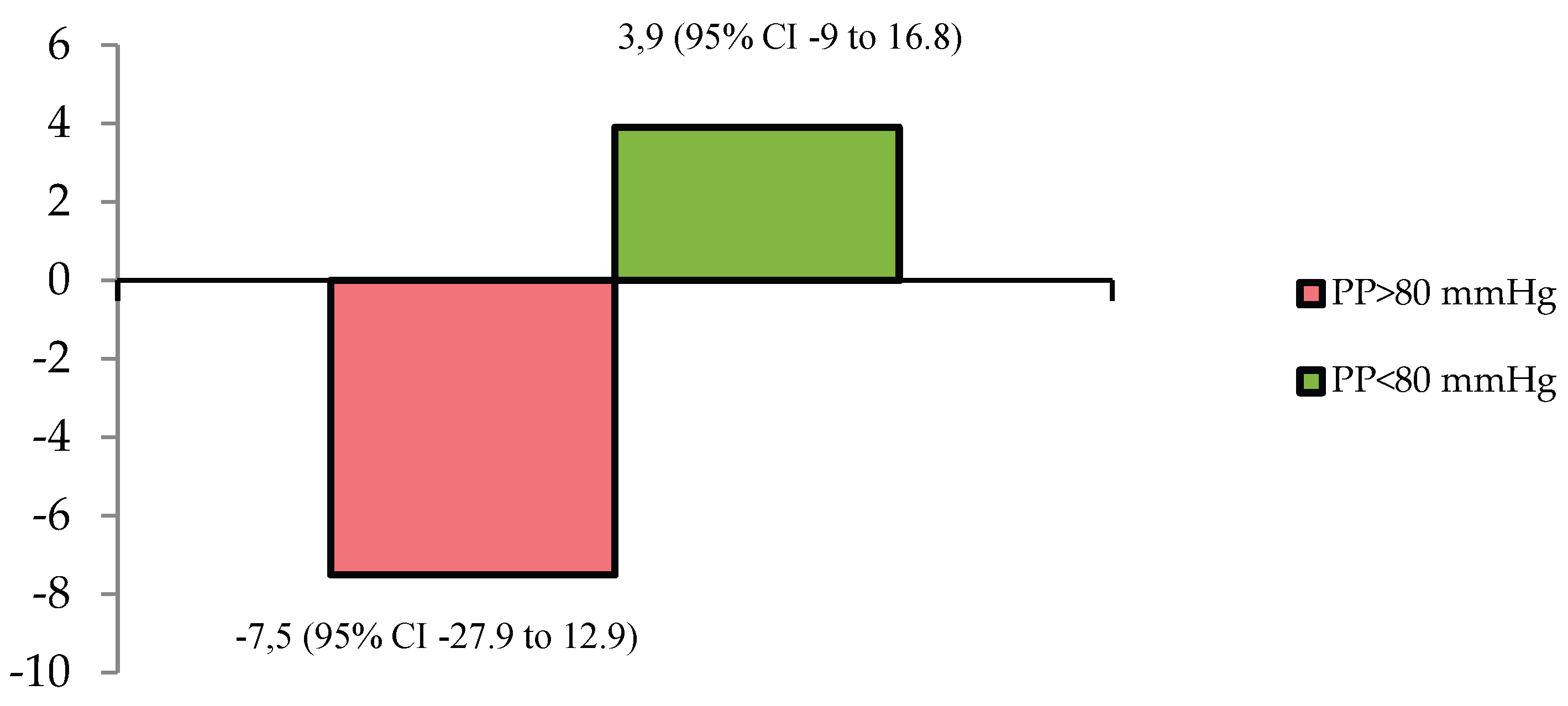

Comparative analysis of eGFR changes between patients with baseline PP ≥80 mmHg and <80 mmHg confirmed divergent renal functional trajectories (

Figure 4), with a mean intergroup difference of 11.5 mL/min/1.73m² (95% CI: 2.1–20.6; p = 0.018).

Comparative analysis of the nephroprotective effect, defined as the absence of a decline in eGFR, between patients with HbA1c levels ≥8% and <8% revealed significant differences (p=0.037). The frequency of this nephroprotective effect was 66.7% (12 of 18 patients) in the HbA1c <8% group, compared to 22.2% (2 of 9 patients) in the HbA1c ≥8% group. Patients with HbA1c ≥8% have a sevenfold reduction in the likelihood of developing the nephroprotective effect (OR=0.143, 95% CI: 0.022–0.910). To investigate whether the attenuated nephroprotective effect associated with elevated HbA1c levels was attributable to increased vascular stiffness, PP levels were compared between the HbA1c ≥8% and <8% groups. No significant intergroup differences in PP were detected (77.8 ± 14.8 mmHg vs. 75.4 ± 20.5 mmHg, p=0.741). Similarly, the frequency of elevated PP (>80 mmHg) did not differ significantly between the HbA1c ≥8% and <8% groups (45.5% vs. 27.8%, p=0.282).

4. Discussion

This study represents the first evaluation of the ability of the distal RDN to slow or prevent the progressive decline in renal function in diabetic patients with RHTN and renal dysfunction (in most cases). It was a primary finding of this study. No significant changes were observed in serum lipocalin-2, cystatin C, 24-hour urinary albumin excretion, renal blood flow parameters, or kidney volumetric measurements during the follow-up period. These findings suggest a clinically meaningful nephroprotective effect. Previously, we demonstrated similar nephroprotective efficacy of distal RDN in patients with RHTN over a 3-year follow-up [

28]; however, in that study, first-generation renal catheters (Symplicity Flex) were used for the intervention. Notably, the mean annual decline in eGFR in T2DM patients is reported as 3.3 ± 8.2 mL/min/1.73 m²/year, compared to 2.4 ± 7.7 mL/min/1.73 m²/year in non-diabetic individuals [

11]. According to our data, no significant change in eGFR was observed 1 year after dRDN, including in those with CKD. Similar data (on slowing/preventing progression of renal dysfunction after RDN) were reported by Chinese researchers in patients with CKD after a 6-month follow-up [

29]. The meta-analysis by Mohammad et al. also demonstrated no progressive decline in renal function in patients with RHTN and CKD after RDN [

30].Data from the global SYMPLICITY registry further reinforced these findings, showing that at 3 years post-RDN, CKD patients exhibited an approximately twofold slower decline in GFR compared to non-CKD patients (-3.7 mL/min/1.73 m² vs. -7.1 mL/min/1.73 m², respectively) [

31], despite comparable reductions in BP.

It is important to emphasize that the no significant change in eGFR occurred despite significant BP reduction. At the same time, on the basis of previously conducted studies for hypertensive/diabetic populations, where combined disease-related (2-4 mL/min/1.73m²/year) and antihypertensive treatment-associated (2 mL/min/1.73m²) declines—as evidenced by SPRINT and ACCORD-BP trial data—would predict a total annual reduction of 4-6 mL/min/1.73m².

The analysis of individual data from 2 large RCTs SPRINT and ACCORD-BP has shown that a decrease in BP due to antihypertensive pharmacotherapy causes a proportional decrease in eGFR, starting from a level of ≥10 mm Hg whereas lowering BP to less than 10 mm Hg does not affect eGFR. There was a linear decrease of 3.4% eGFR (95% CI, 2.9%-3.9%) per 10 mm Hg mean arterial pressure decrease. The observed eGFR decline based on 95% of the subjects varied from 26% after 0 mm Hg to 46% with a 40 mm Hg mean BP decrease. Accordingly, a decrease in eGFR would be expected in responders, and particularly in super-responders, within our study cohort. Based on the magnitude of 24-hour BP reduction achieved, a minimum eGFR decline of 3.4% should have manifested in the overall cohort. The lack of this anticipated GFR reduction points to possible restoration of kidney function, attributable to renal tissue regeneration consequent upon enhanced perfusion and diminished functional burden.

4.1. Effects of dRDN on 24-Hour Ambulatory Blood Pressure

This study documented significant reductions not only in systolic and diastolic BP, but also in PP. The incidence of elevated PP >60 mm Hg decreased by a factor of 1.9.

The beneficial effect of RDN on PP was also observed in the global SYMPLICITY registry [

32], the Regina RDN trial [

33] and a meta-analysis of five controlled studies in patients with RHTN at 6 months post-RDN [

34].

From an organ protection standpoint, decrease in PP is of considerable clinical importance. Elevated PP reflects increased arterial stiffness, which is associated with adverse cardiovascular [

35,

36] and renal outcomes [

37,

38]. ). As arterial stiffness progresses, the arterial wall’s capacity to dampen pulsatile energy diminishes. Consequently, the renal microvasculature experiences heightened pulsatile stress due to direct transmission of pressure waves to the glomeruli, resulting in barotrauma [

39]. This hemodynamic burden initiates a pathophysiological cascade comprising glomerular hypertrophy, hyperfiltration, segmental glomerulosclerosis, and ultimately nephrosclerosis and interstitial fibrosis [

37]. Therefore, management strategies for HTN and nephroprotection should encompass comprehensive control of not only systolic and diastolic BP, but also PP.

Additionally, we observed reductions in 24-hour and daytime BP variability, consistent with findings from the Persu et al. meta-analysis [

40]. It is hypothesized that diminished BP variability may confer independent organ-protective effects by mitigating hemodynamic fluctuations—a significant stressor in the pathophysiology of end-organ damage. In our prior study of patients with diabetes and refractory HTN, RDN reduced nocturnal systolic BP variability [

41].

4.2. Effects of dRDN on Renal Function and Hemodynamics

No significant changes in cystatin C, NGAL, albuminuria, or MRI-derived renal dimensions were detected, indicating preserved renal structural and functional integrity. Our results suggest a good safety profile of the procedure, even among individuals with baseline renal impairment, which is consistent with the data of Liu et al. [

29].

We did not find any changes in albuminuria after renal denervation. Previous studies have shown both a decrease in albuminuria after RDN [

42] and the absence of such an effect [

33]. Taken together, these data suggest that RDN at least attenuates hypertension-mediated kidney injury and in most cases prevents further albuminuria progression. Data regarding RDN’s effect on cystatin C remain inconsistent [

43], which may reflect this biomarker’s dependence on extrarenal factors beyond glomerular function. Our finding of unchanged NGAL levels corroborates prior observations by Dörr et al. [

44,

45]. Renal dimensional and volumetric stability following RDN was previously documented by Sanders et al. [

46]. No significant changes in RRI were observed in the overall cohort, CKD/non-CKD subgroups, or when stratified by magnitude of BP reduction. Our previous work established that RRI decreases in patients with RHTN and T2DM only when baseline elevation exists [

47]. Notably, the absence of renal hemodynamic deterioration in hypertensive diabetic patients may reflect nephroprotective effects of the procedure, potentially counteracting persistent adverse metabolic influences. Critically, Al Ghorani et al. reported sustained RRI stability even 10 years post-RDN despite natural vascular aging processes [

48]. Conversely, Mahfoud et al. documented significant RRI reductions at 3 and 6 months post-RDN independent of BP-lowering magnitude [

49]. However, this study enrolled only 15 diabetic patients, limiting generalizability.

4.3. Effects of dRDN on Glucose Metabolism and Catecholamines

No alterations in glucose levels or HbA1c were observed. Despite preclinical evidence suggesting renal denervation (RDN) may improve glycemic control through multiple molecular pathways, current clinical trial data remain discordant and do not indicate unequivocal improvement in glucose homeostasis or insulin sensitivity parameters [

50]. We detected no changes in plasma or urinary metanephrines, corroborating findings from a recent meta-analysis [

51].

4.4. Determinants of Renal Function Changes After dRDN

In our study HbA1c levels and PP were independent determinants of eGFR changes at 12 months post-RDN. Elevated PP can drive irreversible renal damage through chronic barotrauma, where hemodynamic stress is transmitted to the microvasculature and glomerular capillaries. At the same time, post-RDN tonic renal vasodilation and reduced vascular resistance may attenuate arterial wall compliance, potentially facilitating pulsatile energy transmission to glomeruli and exacerbating hemodynamic stress on compromised nephrons. This pathophysiological framework aligns with P. Y. Courand et al.’s findings of progressive eGFR decline in patients with aortic calcification following RDN [

52]. Notably, our data demonstrate that eGFR reduction occurred predominantly in patients with PP >80 mmHg. This suggests RDN’s renoprotective effects may be more pronounced in individuals with minimal vascular stiffness burden. Furthermore, we previously identified baseline PP >60 mmHg as a risk factor for renal parenchymal volume loss at 12 months post-RDN[

53]. Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors have previously been shown to be effective in slowing CKD progression and reducing cardiovascular risk [

54]. It should be noted that our patients did not use SGLT2 inhibitors, but all of them received renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors.

4.5. Study Limitations

The notable strengths of our study include the use of a second-generation multi-electrode catheter (Symplicity Spyral™), assessment of BP reduction via ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM), the center’s extensive experience in performing renal denervation (RDN) procedures, and the absence of confounding due to SGLT2 inhibitor therapy during the study.

Several important study limitations should be acknowledged. First, this was a single-arm study with no sham-control group. However, several rigorously controlled studies of RDN have previously shown a quite insignificant effect of the sham procedure on BP at 3-6 months after the intervention . Second, the small sample size may not have provided enough power to detect some between-group differences in secondary outcomes. Third, medication adherence was assessed through patient self-report.

4.6. Perspectives

The potential benefits of RDN’s sympatholytic effect warrant further investigation and may provide therapeutic advantages for other conditions characterized by heightened sympathetic activity, such as heart failure. Given that SGLT2 inhibitors reduce sympathetic nervous system activity[

55,

56,

57,

58], improve metabolic control, and confer nephroprotective effects, future randomized studies are needed to examine the impact on renal function of combining RDN with SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with RHTN and type T2DM.

Another promising research avenue involves exploring the nephroprotective potential of combining RDN with the non-steroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist finerenone, which has demonstrated robust evidence for reducing risks of CKD progression and cardiovascular complications [

59]. Undoubtedly, our findings require further validation in larger randomized controlled trials. As evidence accumulates supporting the nephroprotective efficacy of RDN, this procedure may emerge as the fourth pillar of therapeutic strategies to retard kidney disease progression in diabetes—alongside renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system blockade, SGLT2 inhibitors, and finerenone [

60].

Given that CKD patients are at high risk of contrast-induced nephropathy following contrast-enhanced RDN procedures [

32], which may also limit the realization of the intervention’s nephroprotective potential — future research could focus on comparing changes in renal function after RDN performed with contrast-based versus non-contrast CO2 angiography [

61].

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, distal renal denervation in patients with RHTN and concomitant T2DM is safe and associated not only with significant and sustained BP reduction but also with stabilization of renal function in contrast to the expected decrease of that function from natural decline in patients with HTN or diabetes and, also, as a result of the BP lowering effect of RDN. This nephroprotective effect of distal RDN in patients with RHTN and T2DM is negatively affected by arterial stiffness and hyperglycemia at baseline, while may be partly attributable to treatment induced reductions in arterial stiffness.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M., A.F. and S.P.; methodology, M.M., S.P., A.F. and V.M.; software, M.M., S.P. and A.F.; validation, M.M., S.P. and A.F.; formal analysis, M.M.; investigation, M.M., I.Z., V.L., E.S., S.K., A.G.; resources, M.M., S.P., A.F. and V.M; data curation, M.M., I.Z., V.L., E.S., S.K., A.G.; writing—original draft preparation, , M.M., I.Z., V.L., E.S., S.K and A.F.; writing—review and editing, M.M., S.P., A.F and V.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Cardiology Research Institute at Tomsk National Research Medical Center (IRB No. 174; approval date: 04 July 2018).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 24h SBP |

24-hour ambulatory systolic blood pressure |

| BP |

Blood pressure |

| BPM |

Beats per minute |

| CKD |

Chronic kidney disease |

| DBP |

diastolic blood pressure |

| dRDN |

Distal renal denervation |

| eGFR |

estimated glomerular filtration rate |

| HbA1c |

glycosylated hemoglobin |

| HTN |

Hypertension |

| MRI |

Magnetic resonance imaging |

| RHTN |

Resistant hypertension |

| RRI |

renal resistive index |

| SBP |

systolic / diastolic blood pressure |

| SNS |

sympathetic nervous system |

| T2DM |

type 2 diabetes mellitus |

References

- Martin, S.S.; Aday, A.W.; Almarzooq, Z.I.; Anderson, C.A.M.; Arora, P.; Avery, C.L.; Baker-Smith, C.M.; Barone Gibbs, B.; Beaton, A.Z.; Boehme, A.K.; et al. 2024 Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics: A Report of US and Global Data From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2024, 149, e347–e913. [CrossRef]

- Bello, A.K.; Okpechi, I.G.; Levin, A.; Ye, F.; Damster, S.; Arruebo, S.; Donner, J.-A.; Caskey, F.J.; Cho, Y.; Davids, M.R.; et al. An Update on the Global Disparities in Kidney Disease Burden and Care across World Countries and Regions. Lancet Glob Health 2024, 12, e382–e395. [CrossRef]

- Francis, A.; Harhay, M.N.; Ong, A.C.M.; Tummalapalli, S.L.; Ortiz, A.; Fogo, A.B.; Fliser, D.; Roy-Chaudhury, P.; Fontana, M.; Nangaku, M.; et al. Chronic Kidney Disease and the Global Public Health Agenda: An International Consensus. Nat Rev Nephrol 2024, 20, 473–485. [CrossRef]

- Ruilope, L.M.; Ortiz, A.; Ruiz-Hurtado, G. Hypertension and the Kidney: An Update. Eur Heart J 2024, 45, 1497–1499. [CrossRef]

- Kovesdy, C.P. Epidemiology of Chronic Kidney Disease: An Update 2022. Kidney Int Suppl 2022, 12, 7–11. [CrossRef]

- Tonelli, M.; Nangaku, M.; Machalska, M.; Fogo, A.; Jha, V.; Harris, D.; Levin, A.; Remuzzi, G. Guatemala’s Resolution on Kidney Health: A Historic Opportunity. The Lancet 2025, 405, 1809–1810. [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, C.R.L.; Leite, N.C.; Bacan, G.; Ataíde, D.S.; Gorgonio, L.K.C.; Salles, G.F. Prognostic Importance of Resistant Hypertension in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes: The Rio de Janeiro Type 2 Diabetes Cohort Study. Diabetes Care 2019, 43, 219–227. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, G.; Xie, D.; Chen, H.-Y.; Anderson, A.H.; Appel, L.J.; Bodana, S.; Brecklin, C.S.; Drawz, P.; Flack, J.M.; Miller, E.R.; et al. Prevalence and Prognostic Significance of Apparent Treatment Resistant Hypertension in Chronic Kidney Disease. Hypertension 2016, 67, 387–396. [CrossRef]

- Tanner, R.M.; Shimbo, D.; Irvin, M.R.; Spruill, T.M.; Bromfield, S.G.; Seals, S.R.; Young, B.A.; Muntner, P. Chronic Kidney Disease and Incident Apparent Treatment-Resistant Hypertension among Blacks: Data from the Jackson Heart Study. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2017, 19, 1117–1124. [CrossRef]

- Carey, R.M.; Calhoun, D.A.; Bakris, G.L.; Brook, R.D.; Daugherty, S.L.; Dennison-Himmelfarb, C.R.; Egan, B.M.; Flack, J.M.; Gidding, S.S.; Judd, E.; et al. Resistant Hypertension: Detection, Evaluation, and Management: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Hypertension 2018, 72. [CrossRef]

- Polonia, J.; Azevedo, A.; Monte, M.; Silva, J.A.; Bertoquini, S. Annual Deterioration of Renal Function in Hypertensive Patients with and without Diabetes. Vasc Health Risk Manag 2017, 13, 231–237. [CrossRef]

- Grassi, G.; Biffi, A.; Seravalle, G.; Bertoli, S.; Airoldi, F.; Corrao, G.; Pisano, A.; Mallamaci, F.; Mancia, G.; Zoccali, C. Sympathetic Nerve Traffic Overactivity in Chronic Kidney Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Hypertens 2021, 39, 408–416. [CrossRef]

- Huggett, R.J.; Scott, E.M.; Gilbey, S.G.; Stoker, J.B.; Mackintosh, A.F.; Mary, D.A.S.G. Impact of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus on Sympathetic Neural Mechanisms in Hypertension. Circulation 2003, 108, 3097–3101. [CrossRef]

- Hering, D.; Lambert, E.A.; Marusic, P.; Walton, A.S.; Krum, H.; Lambert, G.W.; Esler, M.D.; Schlaich, M.P. Substantial Reduction in Single Sympathetic Nerve Firing after Renal Denervation in Patients with Resistant Hypertension. Hypertension 2013, 61, 457–464. [CrossRef]

- Ogoyama, Y.; Tada, K.; Abe, M.; Nanto, S.; Shibata, H.; Mukoyama, M.; Kai, H.; Arima, H.; Kario, K. Effects of Renal Denervation on Blood Pressures in Patients with Hypertension: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Sham-Controlled Trials. Hypertens Res 2022, 45, 210–220. [CrossRef]

- Mancia, G.; Kreutz, R.; Brunström, M.; Burnier, M.; Grassi, G.; Januszewicz, A.; Muiesan, M.L.; Tsioufis, K.; Agabiti-Rosei, E.; Algharably, E.A.E.; et al. 2023 ESH Guidelines for the Management of Arterial Hypertension the Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension : Endorsed by the International Society of Hypertension (ISH) and the European Renal Association (ERA). Journal of Hypertension 2023, 41, 1874–2071.

- McEvoy, J.W.; McCarthy, C.P.; Bruno, R.M.; Brouwers, S.; Canavan, M.D.; Ceconi, C.; Christodorescu, R.M.; Daskalopoulou, S.S.; Ferro, C.J.; Gerdts, E.; et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the Management of Elevated Blood Pressure and Hypertension. Eur Heart J 2024, 45, 3912–4018. [CrossRef]

- Günes-Altan, M.; Schmid, A.; Ott, C.; Bosch, A.; Pietschner, R.; Schiffer, M.; Uder, M.; Schmieder, R.E.; Kannenkeril, D. Blood Pressure Reduction after Renal Denervation in Patients with or without Chronic Kidney Disease. Clinical Kidney Journal 2024, 17, sfad237. [CrossRef]

- Hering, D.; Mahfoud, F.; Walton, A.S.; Krum, H.; Lambert, G.W.; Lambert, E.A.; Sobotka, P.A.; Böhm, M.; Cremers, B.; Esler, M.D.; et al. Renal Denervation in Moderate to Severe CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 2012, 23, 1250–1257. [CrossRef]

- Marin, F.; Fezzi, S.; Gambaro, A.; Ederle, F.; Castaldi, G.; Widmann, M.; Gangemi, C.; Ferrero, V.; Pesarini, G.; Pighi, M.; et al. Insights on Safety and Efficacy of Renal Artery Denervation for Uncontrolled-Resistant Hypertension in a High Risk Population with Chronic Kidney Disease: First Italian Real-World Experience. J Nephrol 2021, 34, 1445–1455. [CrossRef]

- Ott, C.; Schmid, A.; Ditting, T.; Veelken, R.; Uder, M.; Schmieder, R.E. Effects of Renal Denervation on Blood Pressure in Hypertensive Patients with End-Stage Renal Disease: A Single Centre Experience. Clin Exp Nephrol 2019, 23, 749–755. [CrossRef]

- Scalise, F.; Sole, A.; Singh, G.; Sorropago, A.; Sorropago, G.; Ballabeni, C.; Maccario, M.; Vettoretti, S.; Grassi, G.; Mancia, G. Renal Denervation in Patients with End-Stage Renal Disease and Resistant Hypertension on Long-Term Haemodialysis. J Hypertens 2020, 38, 936–942. [CrossRef]

- Schmieder, R.E. Renal Denervation in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease: Current Evidence and Future Perspectives. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation 2022, gfac189. [CrossRef]

- Khwaja, A. KDIGO Clinical Practice Guidelines for Acute Kidney Injury. Nephron Clin Pract 2012, 120, c179-184. [CrossRef]

- Di Nicolò, P.; Prencipe, M.; Lentini, P.; Granata, A. Intraparenchymal Renal Resistive Index: The Basic of Interpretation and Common Misconceptions. In Imaging in Nephrology; Granata, A., Bertolotto, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; pp. 147–156 ISBN 978-3-030-60794-4.

- Ryumshina, N.I.; Zyubanova, I.V.; Sukhareva, A.E.; Manukyan, M.A.; Anfinogenova, N.D.; Gusakova, A.M.; Falkovskaya, A.Y.; Ussov, W.Y. Associations between MRI Signs of Kidney Parenchymal Changes and Biomarkers of Renal Dysfunction in Resistant Hypertension. Siberian Journal of Clinical and Experimental Medicine 2022, 37, 57–66. [CrossRef]

- Barbaro, N.R.; Fontana, V.; Modolo, R.; Faria, A.P.D.; Sabbatini, A.R.; Fonseca, F.H.; Anhê, G.F.; Moreno, H. Increased Arterial Stiffness in Resistant Hypertension Is Associated with Inflammatory Biomarkers. Blood Pressure 2015.

- Pekarskiy, S.; Baev, A.; Falkovskaya, A.; Lichikaki, V.; Sitkova, E.; Zubanova, I.; Manukyan, M.; Tarasov, M.; Mordovin, V.; Popov, S. Durable Strong Efficacy and Favorable Long-Term Renal Safety of the Anatomically Optimized Distal Renal Denervation According to the 3 Year Follow-up Extension of the Double-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial. Heliyon 2022, 8, e08747. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Bian, R.; Qian, Y.; Liao, H.; Gao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, W. Catheter-Based Renal Denervation in Chinese Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease and Uncontrolled Hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2023, 25, 71–77. [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, A.A.; Nawar, K.; Binks, O.; Abdulla, M.H. Effects of Renal Denervation on Kidney Function in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Hum Hypertens 2024, 38, 29–44. [CrossRef]

- Mahfoud, F.; Böhm, M.; Schmieder, R.; Narkiewicz, K.; Ewen, S.; Ruilope, L.; Schlaich, M.; Williams, B.; Fahy, M.; Mancia, G. Effects of Renal Denervation on Kidney Function and Long-Term Outcomes: 3-Year Follow-up from the Global SYMPLICITY Registry. European Heart Journal 2019, 40, 3474–3482. [CrossRef]

- Ott, C.; Mahfoud, F.; Mancia, G.; Narkiewicz, K.; Ruilope, L.M.; Fahy, M.; Schlaich, M.P.; Böhm, M.; Schmieder, R.E. Renal Denervation in Patients with versus without Chronic Kidney Disease: Results from the Global SYMPLICITY Registry with Follow-up Data of 3 Years. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2022, 37, 304–310. [CrossRef]

- Prasad, B.; Berry, W.; Goyal, K.; Dehghani, P.; Townsend, R.R. Central Blood Pressure and Pulse Wave Velocity Changes Post Renal Denervation in Patients With Stages 3 and 4 Chronic Kidney Disease: The Regina RDN Study. Can J Kidney Health Dis 2019, 6, 2054358119828388. [CrossRef]

- Pancholy, S.B.; Shantha, G.P.S.; Patel, T.M.; Sobotka, P.A.; Kandzari, D.E. Meta-Analysis of the Effect of Renal Denervation on Blood Pressure and Pulse Pressure in Patients with Resistant Systemic Hypertension. Am J Cardiol 2014, 114, 856–861. [CrossRef]

- Flint Alexander C.; Conell Carol; Ren Xiushui; Banki Nader M.; Chan Sheila L.; Rao Vivek A.; Melles Ronald B.; Bhatt Deepak L. Effect of Systolic and Diastolic Blood Pressure on Cardiovascular Outcomes. New England Journal of Medicine 2019, 381, 243–251. [CrossRef]

- Böhm, M.; Schumacher, H.; Teo, K.K.; Lonn, E.; Mahfoud, F.; Mann, J.F.E.; Mancia, G.; Redon, J.; Schmieder, R.; Weber, M.; et al. Achieved Diastolic Blood Pressure and Pulse Pressure at Target Systolic Blood Pressure (120-140 mmHg) and Cardiovascular Outcomes in High-Risk Patients: Results from ONTARGET and TRANSCEND Trials. Eur Heart J 2018, 39, 3105–3114. [CrossRef]

- Maeda, T.; Yokota, S.; Nishi, T.; Funakoshi, S.; Tsuji, M.; Satoh, A.; Abe, M.; Kawazoe, M.; Yoshimura, C.; Tada, K.; et al. Association between Pulse Pressure and Progression of Chronic Kidney Disease. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 23275. [CrossRef]

- Geng, T.-T.; Talaei, M.; Jafar, T.H.; Yuan, J.-M.; Koh, W.-P. Pulse Pressure and the Risk of End-Stage Renal Disease Among Chinese Adults in Singapore: The Singapore Chinese Health Study. J Am Heart Assoc 2019, 8, e013282. [CrossRef]

- O’Rourke, M.F.; Safar, M.E. Relationship between Aortic Stiffening and Microvascular Disease in Brain and Kidney: Cause and Logic of Therapy. Hypertension 2005, 46, 200–204. [CrossRef]

- Persu, A.; Gordin, D.; Jacobs, L.; Thijs, L.; Bots, M.L.; Spiering, W.; Miroslawska, A.; Spaak, J.; Rosa, J.; de Jong, M.R.; et al. Blood Pressure Response to Renal Denervation Is Correlated with Baseline Blood Pressure Variability: A Patient-Level Meta-Analysis. Journal of Hypertension 2018, 36, 221. [CrossRef]

- Falkovskaya, A.Y.; Mordovin, V.F.; Pekarskiy, S.E.; Manukyan, M.A.; Ripp, T.M.; Zyubanova, I.V.; Lichikaki, V.A.; Sitkova, E.S.; Gusakova, A.M.; Baev, A.E. Refractory and Resistant Hypertension in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Different Response to Renal Denervation. Kardiologiia 2021, 61, 54–61. [CrossRef]

- Ott, C.; Mahfoud, F.; Schmid, A.; Toennes, S.W.; Ewen, S.; Ditting, T.; Veelken, R.; Ukena, C.; Uder, M.; Böhm, M.; et al. Renal Denervation Preserves Renal Function in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease and Resistant Hypertension. J Hypertens 2015, 33, 1261–1266. [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, D.; Konishi, Y.; Kitada, K. Effects of Renal Denervation on the Kidney: Albuminuria, Proteinuria, and Renal Function. Hypertens Res 2024, 47, 2659–2664. [CrossRef]

- Dörr, O.; Liebetrau, C.; Möllmann, H.; Achenbach, S.; Sedding, D.; Szardien, S.; Willmer, M.; Rixe, J.; Troidl, C.; Elsässer, A.; et al. Renal Sympathetic Denervation Does Not Aggravate Functional or Structural Renal Damage. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013, 61, 479–480. [CrossRef]

- Dörr, O.; Liebetrau, C.; Möllmann, H.; Gaede, L.; Troidl, C.; Wiebe, J.; Renker, M.; Bauer, T.; Hamm, C.; Nef, H. Long-Term Verification of Functional and Structural Renal Damage after Renal Sympathetic Denervation. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2016, 87, 1298–1303. [CrossRef]

- Sanders, M.F.; van Doormaal, P.J.; Beeftink, M.M.A.; Bots, M.L.; Fadl Elmula, F.E.M.; Habets, J.; Hammer, F.; Hoffmann, P.; Jacobs, L.; Mark, P.B.; et al. Renal Artery and Parenchymal Changes after Renal Denervation: Assessment by Magnetic Resonance Angiography. Eur Radiol 2017, 27, 3934–3941. [CrossRef]

- Manukyan, M.; Falkovskaya, A.; Mordovin, V.; Pekarskiy, S.; Zyubanova, I.; Solonskaya, E.; Ryabova, T.; Khunkhinova, S.; Vtorushina, A.; Popov, S. Favorable Effect of Renal Denervation on Elevated Renal Vascular Resistance in Patients with Resistant Hypertension and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Front Cardiovasc Med 2022, 9, 1010546. [CrossRef]

- Al Ghorani, H.; Kulenthiran, S.; Lauder, L.; Recktenwald, M.J.M.; Dederer, J.; Kunz, M.; Götzinger, F.; Ewen, S.; Ukena, C.; Böhm, M.; et al. Ultra-Long-Term Efficacy and Safety of Catheter-Based Renal Denervation in Resistant Hypertension: 10-Year Follow-up Outcomes. Clin Res Cardiol 2024, 113, 1384–1392. [CrossRef]

- Mahfoud, F.; Cremers, B.; Janker, J.; Link, B.; Vonend, O.; Ukena, C.; Linz, D.; Schmieder, R.; Rump, L.C.; Kindermann, I.; et al. Renal Hemodynamics and Renal Function After Catheter-Based Renal Sympathetic Denervation in Patients With Resistant Hypertension. Hypertension 2012, 60, 419–424. [CrossRef]

- Koutra, E.; Dimitriadis, K.; Pyrpyris, N.; Iliakis, P.; Fragkoulis, C.; Beneki, E.; Kasiakogias, A.; Tsioufis, P.; Tatakis, F.; Kordalis, A.; et al. Unravelling the Effect of Renal Denervation on Glucose Homeostasis: More Questions than Answers? Acta Diabetol 2024, 61, 267–280. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Lin, L.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, X. Effects of Catheter-Based Renal Denervation on Renin-Aldosterone System, Catecholamines, and Electrolytes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. The Journal of Clinical Hypertension 2022, 24, 1537–1546. [CrossRef]

- Courand, P.-Y.; Pereira, H.; Del Giudice, C.; Gosse, P.; Monge, M.; Bobrie, G.; Delsart, P.; Mounier-Vehier, C.; Lantelme, P.; Denolle, T.; et al. Abdominal Aortic Calcifications Influences the Systemic and Renal Hemodynamic Response to Renal Denervation in the DENERHTN (Renal Denervation for Hypertension) Trial. J Am Heart Assoc 2017, 6, e007062. [CrossRef]

- Ryumshina, N.I.; Zyubanova, I.V.; Musatova, O.V.; Mochula, O.V.; Manukyan, M.A.; Sukhareva, A.E.; Zavadovsky, K.V.; Falkovskaya, A.Y. Predictors of the preservation of renal parenchyma volume after renal denervation in patients with resistant hypertension according to magnetic resonance imaging. “Arterial’naya Gipertenziya” (“Arterial Hypertension”) 2023, 29, 467–480. [CrossRef]

- Maxson, R.; Starr, J.; Sewell, J.; Lyas, C. SGLT2 Inhibitors to Slow Chronic Kidney Disease Progression: A Review. Clin Ther 2024, 46, e23–e28. [CrossRef]

- Herat, L.Y.; Magno, A.L.; Rudnicka, C.; Hricova, J.; Carnagarin, R.; Ward, N.C.; Arcambal, A.; Kiuchi, M.G.; Head, G.A.; Schlaich, M.P.; et al. SGLT2 Inhibitor–Induced Sympathoinhibition. JACC Basic Transl Sci 2020, 5, 169–179. [CrossRef]

- Böhm, M.; Kario, K.; Kandzari, D.E.; Mahfoud, F.; Weber, M.A.; Schmieder, R.E.; Tsioufis, K.; Pocock, S.; Konstantinidis, D.; Choi, J.W.; et al. Efficacy of Catheter-Based Renal Denervation in the Absence of Antihypertensive Medications (SPYRAL HTN-OFF MED Pivotal): A Multicentre, Randomised, Sham-Controlled Trial. The Lancet 2020, 395, 1444–1451. [CrossRef]

- Kandzari, D.E.; Böhm, M.; Mahfoud, F.; Townsend, R.R.; Weber, M.A.; Pocock, S.; Tsioufis, K.; Tousoulis, D.; Choi, J.W.; East, C.; et al. Effect of Renal Denervation on Blood Pressure in the Presence of Antihypertensive Drugs: 6-Month Efficacy and Safety Results from the SPYRAL HTN-ON MED Proof-of-Concept Randomised Trial. The Lancet 2018, 391, 2346–2355. [CrossRef]

- Townsend, R.R.; Mahfoud, F.; Kandzari, D.E.; Kario, K.; Pocock, S.; Weber, M.A.; Ewen, S.; Tsioufis, K.; Tousoulis, D.; Sharp, A.S.P.; et al. Catheter-Based Renal Denervation in Patients with Uncontrolled Hypertension in the Absence of Antihypertensive Medications (SPYRAL HTN-OFF MED): A Randomised, Sham-Controlled, Proof-of-Concept Trial. The Lancet 2017, 390, 2160–2170. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.; Filippatos, G.; Pitt, B.; Anker, S.D.; Rossing, P.; Joseph, A.; Kolkhof, P.; Nowack, C.; Gebel, M.; Ruilope, L.M.; et al. Cardiovascular and Kidney Outcomes with Finerenone in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes and Chronic Kidney Disease: The FIDELITY Pooled Analysis. Eur Heart J 2022, 43, 474–484. [CrossRef]

- Naaman, S.C.; Bakris, G.L. Diabetic Nephropathy: Update on Pillars of Therapy Slowing Progression. Diabetes Care 2023, 46, 1574–1586. [CrossRef]

- Shinohara, K. Renal Denervation in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease: An Approach Using CO2 Angiography. Hypertens Res 2024, 47, 1431–1433. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).