1. Introduction

Healthcare has become a significant contributor to global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, accounting for approximately 4.4% of total global emissions—if considered a country, the sector would rank fifth worldwide [

1]. This paradox—an industry devoted to protecting human health while simultaneously threatening planetary health—positions hospital decarbonization as a central sustainability challenge. The 2015 Paris Agreement and the European Green Deal have established ambitious targets requiring all sectors, including healthcare, to reduce their carbon footprint by at least 55% by 2030 and to achieve climate neutrality by 2050 [

2,

3].

Hospitals are complex socio-technical systems characterized by high resource intensity, substantial energy demand, and multiple emission sources. Their environmental impact extends beyond direct energy consumption to include supply chains, waste generation, and medical gases [

4,

5]. Addressing these emissions requires structured, system-based strategies that integrate environmental management with circular economy principles—minimizing waste, optimizing resource flows, and closing material loops [

6]. Within this context, the circular economy has gained growing relevance in healthcare, supporting sustainable procurement, energy efficiency, and waste valorization initiatives [

7,

8,

9].

Recent studies have demonstrated the feasibility of decarbonization in healthcare organizations through interventions such as low-carbon hospital design [

10], energy-efficient retrofitting [

11], and circular procurement models [

12]. However, few empirical works have translated these concepts into a comprehensive and replicable decarbonization model implemented in publicly funded hospitals, particularly within Southern European systems facing financial and regulatory constraints.

This study addresses that gap by developing and validating the HULA Circular Decarbonization Model (HCDM)—a structured and reproducible methodological framework integrating circular economy principles into hospital operations. The model was implemented at the Hospital Universitario Lucus Augusti (HULA, Spain) within the European project Low Carbon Healthcare in the Mediterranean Region.

The article describes the process of designing and executing the hospital’s Carbon Management Plan (CMP), quantifies emission reductions across Scopes 1–3, and analyzes flagship projects including anesthetic gas recovery, food waste prevention, plastic elimination, renewable energy installation, and staff engagement initiatives. This experience provides actionable evidence on how circular economy principles can drive hospital decarbonization, offering a scalable model for public healthcare systems seeking alignment with the European Green Deal, the WHO COP28 Health Report, and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [

13,

14,

15].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Conceptual Approach

This research applies a reproducible methodological framework—the HULA Circular Decarbonization Model (HCDM)—developed to operationalize circular economy principles within hospital settings. The framework was designed and validated at the Hospital Universitario Lucus Augusti (HULA), a publicly funded tertiary facility located in Lugo, Spain.

The model builds on the European project Low Carbon Healthcare in the Mediterranean Region (EUKI–LIFE Programme, 2019–2021), integrating its guidelines for Carbon Management Plans (CMPs) with the Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Protocol and ISO 14,001 standards. Unlike previous case studies, the HCDM is structured as a replicable process model composed of five iterative phases that link institutional governance, operational implementation, and continuous evaluation.

The study’s scope included all activities associated with direct and indirect GHG emissions, classified under the GHG Protocol as Scope 1 (direct), Scope 2 (energy-related indirect), and Scope 3 (other indirect emissions).

2.2. Data Collection and Carbon Accounting

Data were collected over a three-year period (2021–2023) using institutional reports, energy consumption records, supplier documentation, and waste management registries. Validation was ensured through HULA’s Environmental Management System (ISO 14001:2015).

The carbon footprint was calculated in metric tons of CO2 equivalent (tCO2e) using emission factors from the Spanish Ministry for Ecological Transition and the European Environment Agency. For each emission source, activity data (e.g., energy use, anesthetic gas volumes, waste, transport distances) were multiplied by corresponding emission factors. The results were consolidated by scope, allowing comparison with other European healthcare institutions.

2.3. The HULA Circular Decarbonization Model (HCDM)

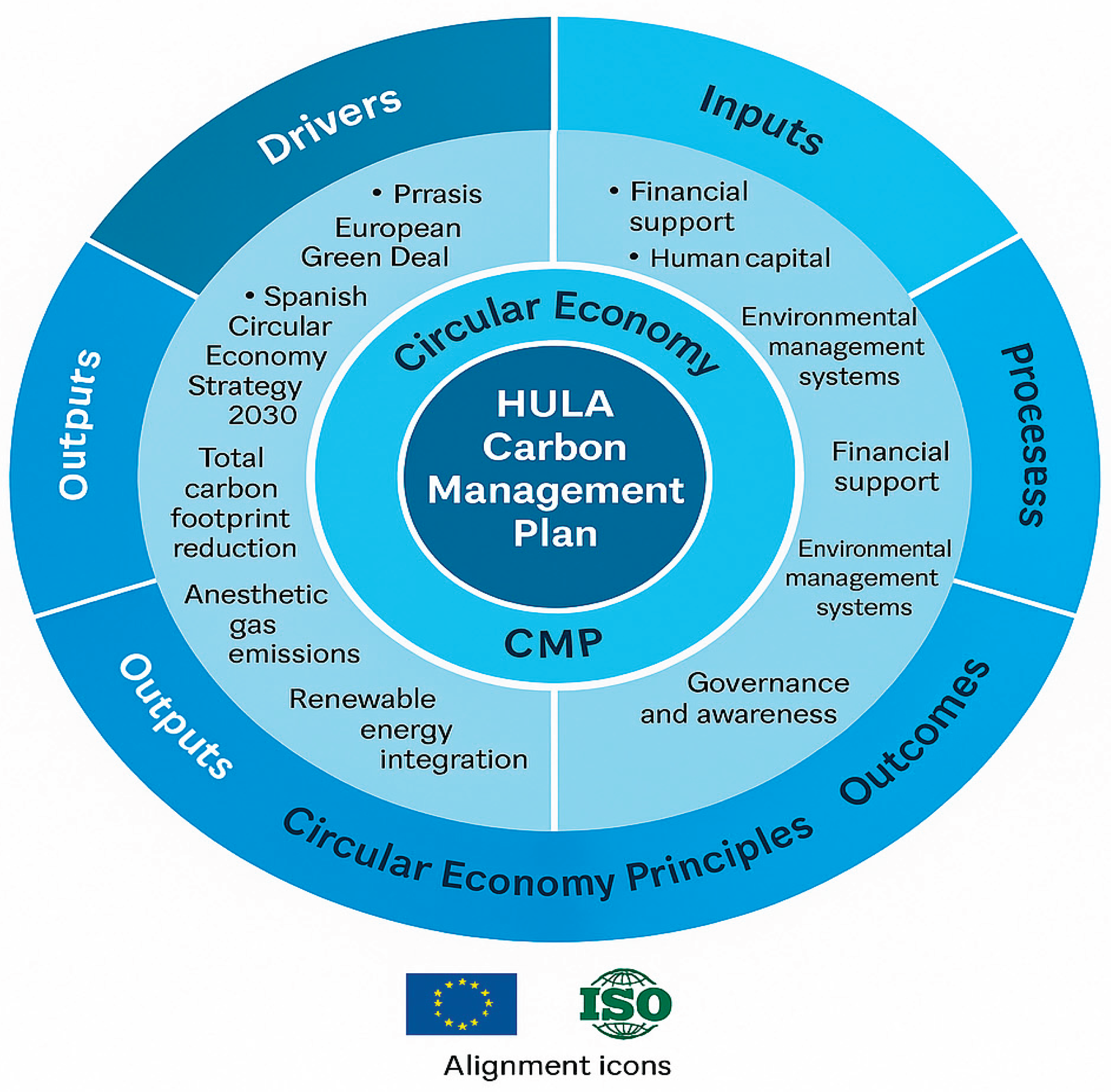

The HCDM synthesizes the hospital’s decarbonization process into a

five-phase methodological model (

Table 1). It provides a structured pathway for healthcare institutions seeking to reduce emissions through circular economy strategies.

Each axis of the CMP aligns with circular economy objectives:

Energy and infrastructure: efficiency and photovoltaic self-consumption.

Clinical emissions: anesthetic gas capture and sustainable prescribing.

Waste and circular economy: plastic reduction and food waste prevention.

Mobility and logistics: low-emission transport and supply-chain optimization.

Governance and awareness: capacity-building and staff engagement.

2.4. Implementation and Monitoring

Implementation began in early 2022, prioritizing interventions with immediate environmental and financial impact. Each action plan included an initial diagnosis, budget, responsible unit, and key performance indicators.

Monitoring followed the ISO 14,001 Plan–Do–Check–Act framework, incorporating both quantitative and qualitative metrics: total GHG emissions (tCO2e), energy consumption (kWh), water use (m3), plastic waste (tons), anesthetic gas emissions (kg), and staff participation rates.

Performance data were reported annually to the hospital’s management board and to the Galician Health Service. The iterative feedback mechanism allowed dynamic adjustment of targets and ensured institutional accountability.

2.5. Data Analysis and Model Validation

Emission reductions between 2021 (baseline) and 2023 were calculated as relative percentage changes. Descriptive statistics summarized quantitative results, while qualitative analysis of internal reports identified enabling factors, challenges, and lessons learned.

Validation of the HCDM was achieved through internal auditing under ISO 14001, cross-referencing with EU GHG Protocol benchmarks, and peer consultation with sustainability officers from other hospitals in the Galician Health Service network.

All findings were integrated into the HULA Decarbonization Framework (

Figure 1), which illustrates the dynamic interaction between institutional drivers, circular resource flows, and carbon reduction outcomes within a publicly funded healthcare system.

3. Results

3.1. Overall carbon footprint reduction

Between 2021 and 2023, the implementation of the Decarbonization Strategy led to a 35% reduction in the total carbon footprint of the Hospital Universitario Lucus Augusti (HULA). Total emissions decreased from 7,262.9 tCO2e in 2021 to 4,687.1 tCO2e in 2023.

The most significant reduction occurred in Scope 1 emissions, which dropped from 6,459.7 tCO2e (88.9% of total emissions) to 4,116.6 tCO2e (87.8%), primarily due to energy efficiency measures and the introduction of anesthetic gas recovery technology.

Although Scope 2 emissions remained at zero (owing to the hospital’s exclusive use of certified renewable electricity), Scope 3 emissions were reduced from 803.3 tCO2e to 570.6 tCO2e through waste minimization, sustainable procurement, and circular food management.

These results confirm the technical and organizational feasibility of implementing circular economy principles in large public hospitals. They also demonstrate that systemic decarbonization can be achieved within existing public budgets, provided there is strong governance, cross-departmental coordination, and structured monitoring.

To summarize the performance achieved during the first phase of implementation,

Table 1 presents key environmental indicators and their percentage changes between 2021 and 2023.

3.2. Key decarbonization projects

Reduction of anesthetic gas emissions: Anesthetic gases represented a critical source of direct emissions. In 2023, the adoption of the Contrafluran® recovery system—based on activated carbon filters—achieved a 95% reduction in emissions of desflurane and sevoflurane, equivalent to 350 tCO2e avoided per year. Implemented across 20 operating rooms with a total cost of €30,000, the initiative has since been replicated in other hospitals within the Galician Health Service, illustrating the model’s scalability.

Food Waste Prevention and Circular Food Management: The hospital’s catering service achieved Spain’s first “Zero Food Waste” certification (AENOR) through mass balance analysis, waste audits, and preventive kitchen measures. The initiative directly contributed to Scope 3 emission reductions and aligned with Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 2, 12, and 13.

Plastic Reduction and Substitution: The replacement of disposable biosanitary containers with reusable systems reduced plastic waste by approximately 30 tons per year, avoiding around 20 tCO2e. The elimination of 350,000 single-use plastic bags through textile logistics further advanced the hospital’s circular resource strategy.

Digital Transformation and Paperless Hospital Initiative: The “Escriba” digital documentation project eliminated over 2.9 million printed documents, reducing paper use by 41% between 2021 and 2022. This initiative contributed both to carbon reduction and organizational efficiency.

Renewable Energy and Photovoltaic Self-Consumption: In 2024, 997.9 kW of photovoltaic capacity were installed under the regional INEGA Renewable Energy Program, reinforcing the hospital’s resilience to fossil fuel dependency and further consolidating Scope 2 decarbonization.

Waste Valorization and Biosecurity Improvements: Enhanced segregation in non-hazardous waste streams enabled 25–35% material recovery, mainly plastics. The installation of 17 cold-based biosecurity units eliminated volatile emissions in laboratories, reducing 19.8 tCO2e annually and improving occupational safety.

Organizational outcomes and awareness

Beyond quantitative reductions, the HCDM fostered a cultural transformation within the hospital. Sustainability awareness and participation increased markedly among both clinical and administrative staff. Interdisciplinary teams and management support ensured the integration of sustainability objectives into institutional planning.

The hospital’s leadership has been recognized regionally and nationally, positioning HULA as a reference model within the Galician Health Service. The Decarbonization Strategy also reinforced institutional alignment with the European Green Deal, the Spanish Circular Economy Strategy (España Circular 2030), and the WHO COP28 Special Report on Climate Change and Health (2023).

4. Discussion

The experience of the Hospital Universitario Lucus Augusti (HULA) demonstrates that meaningful carbon reductions can be achieved in public healthcare systems when environmental management and circular economy principles are integrated into everyday operations. The results confirm that hospitals, despite their structural complexity and financial constraints, can move beyond isolated sustainability actions toward a consolidated Decarbonization Strategy aligned with European and global climate goals.

4.1. Lessons Learned from Implementation

The most significant finding is that measurable emission reductions—35% in two years—were possible through a combination of organizational commitment, interdisciplinary collaboration, and gradual investment in circular processes. The Carbon Management Plan (CMP) proved essential as an operational framework, allowing the hospital to translate general environmental ambitions into specific, measurable actions.

Unlike many theoretical approaches, the HULA model evolved from an existing ISO 14001:2015 environmental certification toward a comprehensive framework integrating carbon accounting, waste valorization, and social engagement. This hybrid structure bridges a gap identified in prior literature, where sustainability initiatives in healthcare often remain fragmented or lack quantitative validation [

1,

7,

9]. The success of HULA depended less on technological innovation and more on governance coherence and human engagement, consistent with other public-sector circular management initiatives in Europe [

10,

11].

4.2. Integrating Circular Economy Principles into Healthcare

The implementation confirmed that circular economy principles can be effectively operationalized within hospital environments without compromising clinical quality or safety. Initiatives such as anesthetic gas recovery, zero food waste certification, and plastic substitution exemplify the transition from linear consumption to restorative resource cycles.

These results are consistent with findings in

Journal of Cleaner Production and

Sustainability, which highlight the emergence of circular and low-carbon healthcare as an essential pathway toward planetary health [

12,

13,

14]. In this regard, the Contrafluran® intervention achieved a 95% reduction in anesthetic gas emissions while demonstrating cost-effectiveness and scalability—criteria essential for replication across healthcare systems. Similarly, the

Zero Food Waste program reframed hospital catering services as active agents of climate policy, not merely logistical support—a perspective increasingly emphasized in sustainable healthcare management research [

15,

16].

4.3. Governance, Engagement, and Policy Alignment

Institutional leadership emerged as a decisive enabler of success. The alignment of hospital management, the Galician Health Service, and environmental governance structures ensured continuity of funding and interdepartmental coordination. These dynamics mirror the

“multi-level governance

” conditions identified by the European Environment Agency and WHO as prerequisites for effective sustainability transitions in the public sector [

17,

18].

The HULA Circular Decarbonization Model (HCDM) thus operationalizes climate neutrality targets at the institutional level, bridging micro-level governance with macro-level policy frameworks such as the European Green Deal, the Spanish Circular Economy Strategy (España Circular 2030), and the WHO COP28 Special Report on Climate Change and Health (2023).

Equally important was the cultural dimension: the strategy fostered a shared sense of ownership and responsibility among healthcare staff. Training and communication initiatives increased engagement, reflecting the social sustainability component that is often underrepresented in technical decarbonization frameworks [

19].

4.4. International Context and Comparative Insights

Globally, the HCDM shares common objectives with national initiatives such as the NHS Net Zero Strategy (United Kingdom), the Nordic Sustainable Healthcare Programme, and the Health Care Without Harm Europe Network, yet it offers a distinctive contribution: demonstrating that significant emission reductions can be achieved in publicly funded systems with limited capital investment. This positions the HULA model as a transferable approach for middle-income and resource-constrained healthcare contexts, complementing high-investment strategies in northern Europe and North America.

Furthermore, the model’s focus on governance integration and circular procurement aligns with OECD recommendations for sustainable public administration, underscoring the replicability of HCDM principles across national health systems. Its use of standardized carbon accounting (GHG Protocol) and continuous improvement under ISO 14,001 provides methodological interoperability with international reporting frameworks.

4.5. Challenges and Future Directions

Despite these achievements, several challenges persist. Scope 3 emissions—linked to suppliers and patient transport—remain difficult to quantify and mitigate. Moreover, limited human resources and administrative rigidity can hinder technological innovation in public institutions. Addressing these barriers will require national policy incentives, intersectoral partnerships, and standardized tools for health-sector carbon accounting.

Future development of the HCDM includes expanding the Decarbonízate initiative to primary care centers, integrating artificial intelligence and digital twins for real-time emission tracking, and scaling renewable energy self-generation. These steps aim to consolidate progress toward the 2050 net-zero goal while offering a replicable and evidence-based model adaptable to other regional or international health systems.

5. Conclusions

The results of this study demonstrate that the transition toward low-carbon and circular healthcare is both feasible and measurable within publicly funded health systems. The experience of the Hospital Universitario Lucus Augusti (HULA) validates that structured planning, institutional leadership, and a reproducible methodological framework—the HULA Circular Decarbonization Model (HCDM)—can deliver tangible emission reductions and organizational transformation.

By reducing its total carbon footprint by 35% in two years, the hospital showed that decarbonization does not rely solely on large-scale technological investments. Instead, success emerges from coordinated low-cost interventions—including anesthetic gas recovery, plastic reduction, and food waste prevention—combined with a continuous cycle of monitoring, staff engagement, and governance integration.

The integration of circular economy principles provided a coherent foundation to connect environmental, economic, and social dimensions of hospital management. Beyond emission reduction, the HCDM fostered a culture of sustainability among healthcare professionals, demonstrating that cultural change is a decisive enabler of climate action in the public sector.

From a policy standpoint, this case underlines the potential of regional and national health systems to act as catalysts for climate-neutral transitions. The HCDM operationalizes the European Green Deal, the España Circular 2030 Strategy, and the WHO COP28 Health Agenda at the institutional level. Hospital-based Carbon Management Plans should therefore be recognized as strategic instruments within national sustainability frameworks, linking policy commitments with measurable operational outcomes.

Scaling the HCDM model to other healthcare institutions will require harmonized carbon accounting standards, incentives for renewable energy adoption, and cross-sectoral collaboration between health authorities, local governments, and environmental agencies. Such integration would accelerate the decarbonization of healthcare while reinforcing the sector’s contribution to the UN Sustainable Development Goals, particularly SDG 3 (Health and Well-being), SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), and SDG 13 (Climate Action).

Relevance statement

This study provides one of the first in-depth evaluations of a comprehensive Decarbonization Strategy implemented in a European public hospital. It contributes original evidence to the field of low-carbon and circular healthcare management by linking quantitative emission data with practical governance mechanisms. The HULA Circular Decarbonization Model (HCDM) offers a transferable and policy-relevant framework for healthcare institutions aiming to operationalize climate neutrality targets under resource constraints, reinforcing the central role of the health sector in global sustainability transitions.

References

- Pichler PP, Jaccard IS, Weisz U, Weisz H. International comparison of healthcare carbon footprints. Environ Res Lett. 2019;14(6):064004. [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Paris Agreement of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). 2015. Available at: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/english_paris_agreement.pdf.

- European Commission. The European Green Deal. COM(2019) 640 final. 2019. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52019DC0640.

- Eckelman MJ, Sherman JD. Environmental impacts of the US health care system and effects on public health. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0157014. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Jiménez L, González-Díaz C, Álvarez-Martín E, et al. The carbon footprint of healthcare settings: a systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2023;79(12):e1–e20. [CrossRef]

- Health Care Without Harm (HCWH). Health Care’s Climate Footprint: How the Health Sector Contributes to the Global Climate Crisis and Opportunities for Action. Brussels: HCWH Europe; 2019. https://noharm-global.org/documents/health-cares-climate-footprint.

- Kirchherr J, Reike D, Hekkert M. Conceptualizing the circular economy: an analysis of 114 definitions. Resour Conserv Recycl. 2017;127:221–232. [CrossRef]

- D’Alessandro C, Bianchi G, Romano A, et al. Circular economy practices in the healthcare sector: a comprehensive review. Sustainability. 2024;16(1):401. [CrossRef]

- Rizan C, Bhutta MF, Reed M, Lillywhite R. The carbon footprint of waste streams in a UK hospital. J Clean Prod. 2021;286:125446. [CrossRef]

- Orsini LP, Del Giudice M, Marra A, et al. Towards greener hospitals: the effect of green practices on hospital performance. J Clean Prod. 2024;441:140987. [CrossRef]

- Bizzarri G, Morini GL. New technologies for an effective energy retrofit of hospitals: results of a case study. Energy Build. 2006;38(10):1130–1139. [CrossRef]

- De Masi RF, Palumbo A, Clemente C, et al. Energy retrofit design optimization for hospitals in Mediterranean climate: a multistage approach. Sustainability. 2023;15(14):11450. [CrossRef]

- Aquino ACT de, Menezes PR, Carmo AC. Healthcare waste and circular economy principles: it is time for action. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2024;21(7):792. [CrossRef]

- Andersen MPS, Molander L, Shah A, et al. The climate impact of inhalational anaesthetic gases: a review. Lancet Planet Health. 2023;7(8):e667–e676. [CrossRef]

- Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica y el Reto Demográfico. Estrategia Española de Economía Circular: España Circular 2030. Madrid: Gobierno de España; 2020. https://www.miteco.gob.es/es/.

- Xunta de Galicia. Estrategia Gallega de Economía Circular 2020–2030. Santiago de Compostela: Xunta de Galicia; 2019. https://medioambiente.xunta.gal.

- World Health Organization (WHO). COP28 Special Report on Climate Change and Health. Geneva: WHO; 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/cop28-special-report.

- Mermillod B, Faye B, Hernandez D, et al. Estimating the carbon footprint of healthcare in France. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2024;21(6):690. [CrossRef]

- van Straten B, Butler P, van den Dobbelsteen J, et al. Towards circular hospitals: feasibility of reusing surgical stainless-steel instruments. Sustain Mater Technol. 2021;29:e00297. [CrossRef]

- Reuters. Big Pharma pulls together to shrink healthcare’s outsized carbon footprint. 14 Feb 2024. https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/big-pharma-carbon-footprint-2024-02-14.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).