1. Introduction

In today’s global landscape, characterised by increasing complexity and rapid technological, demographic and social progress, the study of change within public administrations is of crucial importance. Understanding the dynamics through which public administrations adapt and transform is essential to ensuring their effectiveness, their ability to respond to citizens’ needs and their long-term sustainability. The concept of change in the context of public administrations goes beyond simple operational changes, encompassing instead fundamental transformations in structures, processes, cultures and service delivery models (Rocha & Zavale, 2021).

In Italy, public administrations play a fundamental role, being a major employer and a key provider of essential services to citizens (Bulman, 2021). They operate in a dynamic and complex environment, subject to a wide range of internal and external pressures that require adaptation and change (Presidency of the Council of Ministers, 2021). External factors include political and regulatory changes (Capano & Natalini, 2020), public health crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic (ISTAT, 2021), rapid technological advances and the growing need for digital services (Agency for Digital Italy, 2024). Demographic changes are also significant external factors (ISTAT, 2024). The centrality of technology and digitalisation underscores the transformative impact of the digital age, which requires significant changes in service delivery models and work organisation to meet the growing demand for more transparent, accountable and responsive.

Internal factors driving change include the desire to improve performance, the need to evolve organisational culture, changes in leadership and the resulting priorities, the need to address performance gaps and respond to workforce needs (Rocha & Zavale, 2021). This wide range of factors, both internal and external, points to the dynamic and complex nature of the environment in which public administrations operate, which requires constant adaptation and change.

Among the most significant external factors are demographic changes. Italy, in particular, is undergoing significant demographic changes, characterised by a rapidly ageing population, declining birth rates and a growing proportion of older workers in the workforce (World Economics, 2025). Data show that in 2022, 37% of workers in Italy were between 50 and 64 years old (INAPP, 2023).

The ageing of the public sector workforce is not a phenomenon exclusive to Italy, but a trend observed in many OECD countries (OECD, 2021). Many developed nations are facing similar demographic changes in their public administrations. Although the general trend of an ageing public sector workforce is common, the specific age distribution and pace of change may vary between countries due to differences in birth rates, life expectancy, pension policies and labour market dynamics. Some countries may have a higher proportion of young workers in their public sector than Italy, while others may face even more pronounced ageing trends (EBSCO, 2023).

Further complicating the issue, alongside the phenomenon of the progressive ageing of the population and the workforce, is the fact that the contemporary world of work, including public administrations, in Italy and globally, is increasingly characterised by the coexistence of different generations, with the potential for up to five distinct generational groups to coexist (Fry, 2020).

This generational diversity presents both opportunities and challenges for organisational management and work culture, and makes it even more urgent to understand and effectively manage a multigenerational workforce in the public sector (International Monetary Found, 2023). The loss of experienced workers due to retirement requires strategies for knowledge transfer and for attracting and retaining younger generations. The imminent retirement of a large segment of the workforce, particularly Baby Boomers, poses challenges for knowledge transfer and skills continuity. In addition, the rapid pace of technological change requires continuous adaptation and retraining of the workforce. Research suggests a tension between the need for innovation in public administration and potential resistance to change within established bureaucratic structures (Van der Voet, 2016).

The coexistence of multiple generations in the workplace undoubtedly offers a rich landscape of diverse experiences and skills, but it can also serve as fertile ground for the development of ageism (Butler, 1969). This issue is increasingly relevant in a work environment where Traditionalists, Baby Boomers, Generation X, Millennials and Gen Z coexist, each with their own characteristics and expectations (EBSCO, 2023). Examining the relationship between ageism and the chronological age of workers, it is evident that younger workers may have more severe ageist attitudes towards other age groups than older workers (Yi et al., 2022).

Within this discourse, the authors, in agreement with the literature, have chosen to refer to older workers as those aged 50 and above (McCarthy et al., 2014; Zacher & Rudolph, 2023), as the concept of older workers in the workplace develops based on workers’ progressive approach to retirement age. Ageism is therefore a phenomenon that potentially affects a significant portion of the workforce. Ageism in the workplace can take various forms. Research shows that older workers are considered inflexible, unwilling to adapt to technology, resistant to change and in a state of physical and mental decline, which is why they are often considered unsuitable for training and more expensive for the organisation (Johnson et al., 2013; Nelson, 2016).

For older workers, ageism can lead to decreased job satisfaction and motivation, hindering their commitment and productivity and limiting opportunities for advancement and professional growth. The negative consequences of ageism include decreased productivity, increased turnover, and a deterioration of the corporate climate (Yi et al., 2022). Older employees may also feel pressured to retire early due to discrimination and lack of opportunities (Donizzetti, 2015; Duncan & Loretto, 2004). Among older people, ageism is associated with poorer physical and mental health, increased social isolation, loneliness and stress, greater financial insecurity, decreased quality of life and premature death (World Health Organization, 2021).

From an organisational perspective, ageism can have harmful consequences for public administrations. The early retirement of experienced older workers leads to a loss of valuable institutional knowledge and skills (International Monetary Found, 2023). Ageism can stifle innovation and creativity by hindering collaboration and the exchange of ideas between different generations (Wang & Duan, 2024).

Ageism in the case of older women takes on a different and entirely unique form, giving rise to gendered ageism (Itzin & Phillipson, 1995). This refers to the specific discrimination and prejudice that arise from the intersection of age and gender. In the workplace, this often manifests itself through unique challenges for older women, who experience the combined effects of ageism and sexism. This prejudice views feminine attributes associated with youth, such as being physically attractive, as factors that influence women’s work experience (Siguroardóttir & Snorradóttir, 2020). Women face pressure to maintain a youthful appearance in order to be perceived as competent and relevant in the workplace. Unlike older men, whose grey hair may be seen as a sign of experience, wisdom and charm, older women may feel pressure to hide the signs of ageing (Cecil et al., 2023; McGann et al., 2016). In addition, women’s work performance is thought to decline earlier than men’s (Jyrkinen, 2014; McInnins et al., 2021). Women are seen as less competent because of their age and are less frequently asked to take on new responsibilities and tasks. This represents a major obstacle to career advancement. Older women are also more likely to be dismissed or encouraged to reduce their working hours and switch to part-time work (Siguroardóttir & Snorradóttir, 2020).

The presence of gendered ageism in the workplace and its significant impact on job satisfaction (Monahan et al., 2023) and organisational climate (Tahmaseb-McConatha et al., 2023) could further complicate the process of change that the world of work, and public administrations in particular, have been facing in recent years. Recognising these prejudices is a strategic necessity in order to focus on the potential of each worker, transforming the coexistence of different generations, combined with gender specificities, from a potential risk of conflict to a driver of innovation and public value.

Based on what has emerged from the literature, this study aims to explore, through a qualitative survey, the work experience of public administration employees, focusing on intergenerational relationships, gendered ageism and how these may intersect with dimensions such as job satisfaction and organisational climate.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedures

Semi-structured interviews were used to collect data, with the interview grid constructed according to a thematic approach (Braun & Clarke, 2006). The main thematic areas were defined in line with the research objectives. For each area, a number of open-ended questions were formulated with the aim of stimulating the participant’s narrative, along with a series of follow-up questions to explore aspects of interest in more detail. This approach ensured that all topics relevant to the research were covered, while maintaining the flexibility necessary to bring out the subjective experiences of the participants. The tool was designed to explore the perceptions and experiences of the subjects in relation to four main thematic areas: job satisfaction and dissatisfaction (e.g., ‘What satisfies you most about your job and what satisfies you least?’) perception of the organisational climate (e.g., ‘How would you describe the atmosphere in your office and more generally within your work environment?’) the quality of intergenerational relationships in the workplace (e.g., ‘How would you describe your relationships with younger/older colleagues?’) and experiences related to ageism (e.g., “How do you think your younger colleagues view your work abilities?”) and gendered ageism (e.g., “Do you think that for a female worker in the older age group, looking young or not can affect her work experience?”).

Participants were recruited through snowball sampling. According to the inclusion criteria, participants had to be adults working in public administration. Participation was voluntary. Participants were asked to respond honestly and were informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time. The research protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee for Psychological Research of the Department of Humanities at the University of Naples Federico II (prot. 22/2023 of 15/05/2023) and the University’s Privacy Office and was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the APA and the principles of the 1995 Declaration of Helsinki. Written consent to participate was obtained from each participant before the interview began. This consent included authorisation for audio recording, which was carried out to ensure accurate transcription of the content.

2.2. Participants

A total of 30 public administration employees took part in the study. Participants were aged between 24 and 65 (M = 47.23; SD = 11.30), 14 were women and 16 were men. In terms of job category, 13 were managers and 17 were employees. Their length of service varied considerably, from a minimum of 1 year to a maximum of 40 years, highlighting the considerable heterogeneity of the group of participants (M = 11.97; SD = 13.04).

2.3. Analyses

The collected data were analysed following the methodological framework of Thematic Analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006), according to which the analysis of qualitative data follows a process aimed at identifying, analysing and reporting patterns of meaning, i.e. themes, present in the textual corpus. In the first phase, all interviews were transcribed faithfully, forming a single corpus. Subsequently, to ensure a systematic and rigorous analysis of the corpus, T-Lab Plus software was used, a package of linguistic, statistical and graphical tools for text analysis (Lancia, 2004). Using this software, the corpus was first subjected to a process of disambiguation and automatic lemmatisation, which revealed that it consisted of 75,417 occurrences, 6,626 forms and 4,268 lemmas

1.

Subsequently, the corpus underwent a Thematic Analysis of Elementary Contexts, a qualitative-quantitative analysis particularly suited to exploring the content of rich narrative and discursive corpora. This approach allows the patterns of meaning and recurring themes in the participants’ stories to emerge systematically. This analysis is carried out through a process that begins with the division of the text into elementary context units (ECUs), i.e. segments of text that are homogeneous in terms of lexical content and approximately the length of a sentence. These units are then classified and aggregated into thematic clusters based on the co-occurrence of specific keywords within them. The clusters are identified using an unsupervised hierarchical ascending method (specifically, the Bisecting K-Means algorithm). Each cluster consists of a specific vocabulary of keywords, whose statistical relevance within the cluster is measured by the chi-square test. In the final stage, researchers assign an interpretative label to each cluster, based on the vocabulary that characterises it. Furthermore, to visualise the relationships between these thematic clusters, the results are represented graphically using Correspondence Analysis. This graph positions the clusters as points on a Cartesian plane, whose structure is defined by two main axes. These axes are Factorial Axes extracted statistically from the software, representing the most important dimensions of meaning that organise the entire corpus. The horizontal axis (Factor 1) expresses the strongest semantic contrast, while the vertical axis (Factor 2) expresses the second most important contrast. The label assigned to each pole is derived from careful interpretation by the researchers, who analyse the groups of words at opposite ends of each axis to understand the logic of the contrast. In this way, the final graph not only shows the proximity or distance between themes, but also explains the fundamental relationships that define the participants’ experience, thus ensuring rigour and traceability in the qualitative interpretation of the data.

3. Results

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

3.1. Descriptive Analyses

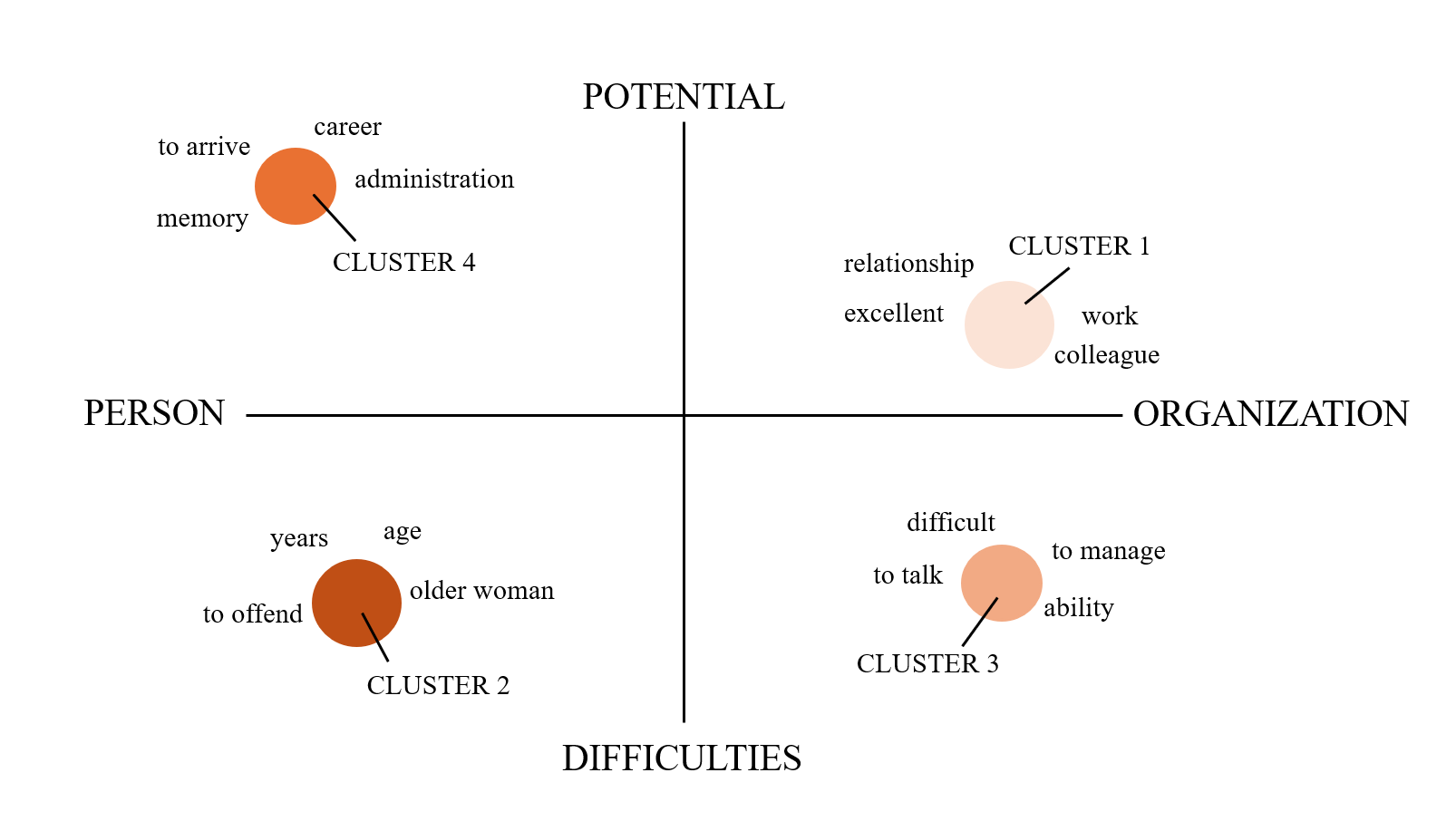

The descriptive analysis classified 1,654 elementary context units (ECUs) and divided them into four clusters, or macro-themes. With regard to the quantitative dimensions of the clusters: CLUSTER 1 consisted of 465 elementary context units, corresponding to 28.11% of the variance; CLUSTER 2 consisted of 479 elementary context units, corresponding to 28.96% of the variance; CLUSTER 3 consisted of 396 elementary context units, corresponding to 23.94% of the variance; finally, CLUSTER 4 consisted of 314 elementary context units, corresponding to 18.98% of the variance.

Table 1 shows the specific vocabularies for each cluster, sorted by T-Lab Plus according to the chi-square value.

The relationships between these clusters are shown on a Cartesian axis (

Figure 1), developed on the basis of the factor axes statistically extracted by the software, which represent the most important dimensions of meaning that organise the entire corpus. The horizontal axis (Factor 1), which expresses the strongest semantic contrast (39.09% of the variance), has been labelled ‘individual’ on the left and ‘organisation’ on the right, to indicate the contrast between individual, personal issues and organisational, relational issues reported by the interviewees. On the vertical axis (Factor 2), which expresses the weakest contrast (33.35% of the variance), the labels ‘potential’ at the top and ‘difficulties’ at the bottom were assigned to highlight the contrast between issues related to the difficulties that respondents feel they face in their work environment and the potential on the basis of which positive change can be developed.

3.2. Cluster 1: Potential and Opportunities in Relationships with Colleagues

This first cluster is positioned at the intersection between potential and organisation, indicating the positive elements that characterise relationships between employees. It is characterised by words such as: work, colleague, relationship, excellent, change and contact. One element that emerges strongly from the analysis is the central role of interpersonal relationships as the foundation of organisational well-being. The interviewees’ words show that having a good relationship with colleagues is directly associated with enjoying the working environment. A young woman who has been working in the same public administration for some time said:

«But I... personally believe I have a fairly peaceful relationship with all my colleagues, so I enjoy my working environment».

Satisfaction with one’s job also seems to be influenced by the quality of the relationships established with colleagues. In this regard, a young male employee who recently joined the public administration said:

«Then I also developed a rapport with the rest of my colleagues, which led me to appreciate the role and the sector I had been assigned to even more».

This cohesion translates into an approach that sees results as the fruit of teamwork rather than individual effort. The emphasis shifts from the individual to the group, and success is perceived as the result of joint effort. An old man who recently joined the public administration said:

«I would say that we try to do our job, at least in my sector, with my colleagues, in the best possible way».

The same interviewee also shows us the pinnacle of this process, which manifests itself in prosocial behaviours that go beyond the formal boundaries of one’s own sector and duties. Solidarity and flexibility become the norm when the ultimate goal is the common good of the organisation. His words perfectly exemplify this mindset:

«I have helped colleagues who may have had a heavier workload, helped colleagues from other sectors, even assembling chairs or drawers without any problems. I mean, if you do it, the important thing is to solve a problem».

3.2. Cluster 2: Ageism and Gendered Ageism

The second cluster is positioned at the intersection between difficulty and the individual, and is characterised by words such as: age, years, old woman and offend. This cluster brings together the critical issues perceived at the individual level and highlights the risk factors that workers associate with their own subjective experience. Among these, the issue of intergenerational comparison emerges as a significant source of tension and friction, taking on markedly negative connotations for some employees.

Elements of prejudice towards older people emerge clearly from the words of a young manager interviewed:

«Let’s say that age has a big impact on jokes; it’s a very relevant issue. For example, men are said to lose their minds when they reach a certain age».

Conversely, older workers recognise that they suffer from such prejudice, reacting with a strategy of defensive distancing, as is evident from the words of an older interviewee:

«They tease me by calling me “grandfather” or “uncle” ... I say, “Listen, mate, you’re thirty or forty years old, but I don’t compare myself to you».

The interviewees’ words also reveal a real comparison between the different generations. On the one hand, older people are seen as stingy holders of knowledge, while on the other, young people are seen as active perpetrators of prejudice and discrimination against this category. A young woman effectively sums up this conflictual dynamic:

«Because, you see, older people, not all of them, but older people tend to keep their knowledge to themselves, not to divulge it, not to pass it on, while young people tend to say: “You’re getting on in years, you’re ready for retirement, you’re slow, you’re not as efficient as I am, so I’m better than you».

The issue becomes more complex and multifaceted when age intersects with gender, giving rise to the phenomenon of gendered ageism. Firstly, we recognise the presence of certain stereotypes related to the age of women in our society, such as: ‘you shouldn’t ask a woman her age’. These stereotypes are not seen as a factor of vulnerability for women but, in the perception of one male interviewee, as a strategic tool used by women to accuse their interlocutor of lack of gallantry:

«Maybe she doesn’t care about her age, but since there is this idea that ‘you shouldn’t ask a woman her age’, then she perceives it as a lack of gallantry, perhaps».

The interviewee continues his reflection, admitting the possibility that some women genuinely suffer because of their age:

«And then there are women who actually suffer from it».

However, this interpretation culminates in a mechanism in which the responsibility for the discomfort is entirely attributed to the women themselves. The same interviewee stated:

«We need to make it clear that a woman should not be offended... That is, she needs to accept her age».

Another dimension of gendered ageism concerns social pressure on physical appearance, an element that seems to weigh heavily on older female workers. On this subject, an older man observed:

«I know that for women, let’s say... the only thing that destabilises them is not the workplace, but their age. So when you talk to the female friends I know, when they reach forty, they already feel old. Because, let’s say, they are confronted with the issue of appearance. Today, it’s all about appearance, beauty... looks».

The direct testimonies of older female workers confirm the complexity of the phenomenon. A first defence mechanism is psychological distancing from the stigmatised category, as emerges from the words of an older interviewee:

«Well, regardless of that, I don’t feel like an old woman».

This distancing is not confined to identity, but translates into concrete behaviours aimed at masking the signs of ageing, as the same woman describes:

«Despite my white hair, which I cover up every 20 days so that no one can see it».

Another issue highlighted by this old woman concerns the discrimination she experiences from her male colleagues, who seem to prefer younger female colleagues:

«So the older male colleague has more fun, showing off with the thirty-year-old colleague rather than the fifty-year-old one, yes, that’s how it is».

The emotional weight of these dynamics is heavy. Another interviewee describes the deep distress caused by age-related insults, to which the woman tries to respond by verbally expressing her discomfort:

«It’s just a matter of feeling bad because I received that insult. But all I can say is, “I was hurt that you said that to me, because it’s true, yes, I feel that I am of a certain age, I don’t disagree with you, but you know that’s the way it is, so why are you criticising me?” ».

Finally, a feeling of inadequacy emerges in relation to atypical career paths, such as being hired at an advanced age. Another woman says she feels out of place because she was hired at the age of 52:

«I feel out of place in my current job [...] but in this case it is my age that makes me feel out of place. It is precisely because I was hired at the age of 52 on a permanent basis in the public administration».

3.3. Cluster 3: Challenges in Managing Working Relationships

The third cluster explores the critical issues that emerge from the interpersonal dynamics within the organisation. It is characterised by words such as: manage, deal with, difficult and organise. Among the elements that seem to generate discontent are the imbalances that sometimes exist between different sectors and professional figures. A female manager said the following on this subject:

«What I like least, from a general point of view, is the organisation of the institution, because in my opinion there are some imbalances between the various sectors and roles».

This structural weakness has a direct impact on the day-to-day management of relationships, making it a difficult and delicate task. A young manager highlights the presence of a fragile balance, which makes interaction between colleagues complex and requires extra attention:

«So it is also difficult to manage relationships with other employees. Having a solid structure in which to operate is certainly important [...] but you also need to have the sensitivity to know how to manage the balance».

To make the management of interpersonal relationships even more complex, there are a number of stereotypes regarding the difficulties that different social categories may have in the workplace. The same young manager, for example, reflects on a supposed lack of relational experience on the part of younger people:

«Perhaps simply with a more mature management of relationships, which a young person certainly cannot have».

But he also reflects on the greater ability of young people, compared to older people, to work in a team:

«Working in teams is always within the capabilities of young people».

The challenges of teamwork are also filtered through a gender lens, giving rise to stereotypes about women’s interpersonal skills. Another young manager articulates a dichotomous view of men’s and women’s abilities:

«Perhaps women have greater precision... let’s say we increase precision by one point and decrease teamwork skills by one point, maybe two. Perhaps men can appear more superficial on certain things, especially formal ones, but perhaps men have greater teamwork skills than women».

Finally, the point of view of older workers regarding the integration of new hires emerges. A senior female worker recognises the academic skills of young people, but identifies barriers that prevent the establishment of positive interpersonal relationships:

«Even though the young people who have joined us now have their own, ‘fresher’ educational background, some of them are full of themselves. So let’s say that relations are limited to good office neighbours».

However, his reflection ends on a hopeful note, suggesting that initial friction can be overcome with time, leaving open the possibility of future integration:

«Then, over time, relationships can improve, that’s for sure».

3.4. Cluster 4: Change in Public Administration and Work-Life Balance

The fourth and final cluster is positioned at the intersection between the individual and potential, highlighting how the transformations taking place in public administration are perceived and experienced subjectively, offering both new opportunities and unprecedented challenges. This cluster is characterised by words such as today, career, young person, arriving, progression and children. A central theme is the perception of an epochal change that is sweeping through the public sector. As one senior employee states:

«Because today we can see that the world has changed».

This change is identified by a young manager with the advent of so-called ‘administration 2.0′, driven primarily by technological innovation, whose evolution is seen as unstoppable:

«In recent years, there has been a change in public administration, administration 2.0 [...]. We’ve reached the age of the computer, but today it is the computer, tomorrow it will be artificial intelligence».

In this scenario, young people are seen as the main repositories of new digital skills, a generational gap well described by an older worker through a comparison with his own youth:

«Today, young people, children, are already growing up in a certain way with regard to computers, smartphones... When I was a boy, our games were table football and pinball, but I also notice this with my children who play on the PlayStation».

In addition to technology, another driver of change is identified in the recruitment of new recruits, whose arrival is seen as a positive factor. An older manager said in this regard:

«The most recent staff recruitment took place in 2019. Many talented young people have joined us».

Intergenerational contact in this context of renewal can become a valuable resource, capable of generating individual well-being, as one senior employee testifies:

«Even though I am 65, I feel like a youngster among the young people».

However, within these dynamics of change, a specific critical issue emerges that concerns female workers: the complex management of the balance between professional and family life. A senior manager with long work experience describes how taking on a managerial position can become unsustainable, leading to resignation in order to safeguard one’s well-being and health, even in the face of economic advantage:

«And so the managerial position becomes problematic. In fact, I can tell you that in 23 years, the worst period of my working life was precisely when I had a managerial position [...] for a woman who wants to balance her career and family with a managerial position [...] because if I have to sacrifice my health to be a manager, honestly, no [...]. If I have to compromise my health to earn double the salary, but I want the salary I earn today and to be healthy and peaceful, to come home peaceful».

This search for a new balance has had a positive outcome in the experience of a young woman who, through a change of job, has rediscovered her well-being by prioritising time for her family, describing this choice as the happiest of her life:

«Now I can be with my son. My son is 7 years old today, so I’m home at Christmas, I’m home at Easter, I’m home on Saturdays and Sundays, whereas before I was forced to go to work anyway, and it was the happiest choice of my life».

4. Discussion

This study aimed to explore the work experience of public administration employees, with a focus on intergenerational relationships, ageism, gendered ageism and their intersections with satisfaction and organisational climate. The qualitative analysis revealed a complex and multifaceted reality, divided into four thematic clusters whose relationship is defined by two main axes: the contrast between the individual and the organisation, and the tension between potential and difficulties. This structure highlights how the experience in the Public Administration is a set of opposing forces, where relational resources and opportunities for change coexist with profound discriminatory and managerial critical issues.

The first axis of meaning that emerged, ‘Potential’, brings together two central themes. On the one hand, Cluster 1, located at the intersection with the ‘organisation- ‘pole, confirms the fundamental role of social and relational capital as a pillar of organisational well-being. The participants’ testimonies, which directly associate good relationships with colleagues with ‘enjoying the working environment’ and greater satisfaction, emphasise how cohesion and prosocial behaviour are a strategic resource for the public administration. This result not only highlights a key factor for individual well-being but also represents a lever for improving performance and organisational culture, crucial objectives in the process of change that public administrations are facing (Rocha & Zavale, 2021; Presidency of the Council of Ministers, 2021).

On the other side of the ‘Potential’ pole, Cluster 4, located at the intersection with the ‘individual’ sphere, shows the subjective perception of change. The advent of ‘administration 2.0′, driven by technology (Agency for Digital Italy, 2024) and the inclusion of new generations in the organisational context (International Monetary Found, 2023), is seen as an inevitable and potentially positive process. The testimony of the older worker who feels like a ‘youngster among young people’ offers a glimpse of how intergenerational contact can be a resource and not just a source of friction. However, this same cluster reveals the other side of the coin: the challenge, especially for women, of balancing career development and private life. The choice to give up management roles to safeguard one’s health or to change jobs to devote oneself to family highlights a systemic critical issue that the public administration must address in order not to lose talent and to ensure substantial equity in career opportunities.

Conversely, the ‘Difficulties’ axis reveals the grey areas of work experience. Cluster 2, located in the ‘individual-difficulties’ quadrant, is the most alarming core of the results. The participants’ narratives not only confirm the presence of ageist stereotypes (the older people as ‘slow’, ‘inefficient’, ‘stingy with knowledge’), in line with what has been documented in the literature (Johnson et al., 2013; Nelson, 2016) but also offer a vivid insight into them. The experience of being ridiculed (‘the grandfather, the uncle’) and the conflictual dynamic described between young and old corroborate the existence of a deep-rooted prejudice that has negative consequences on health (World Health Organization, 2021) and motivation (Yi et al., 2022).

Even more specific and serious is the emergence of gendered ageism (Itzin & Phillipson, 1995). The testimonies collected provide direct empirical evidence of the mechanisms described by international studies. The pressure on appearance, which pushes women to ‘cover their grey hair’, is a clear example of ‘masking’ to conform to standards of youth and competence (Cecil et al., 2023). The observation that ‘the older male colleague shows off in front of his thirty-year-old female colleague’ and the tendency to blame women who take offence at comments about their age (‘you have to accept your age’) reveal a discriminatory double standard that intertwines sexism and ageism, limiting opportunities and undermining job satisfaction (Siguroardóttir & Snorradóttir, 2020; Monahan et al., 2023). This phenomenon, as suggested by Beery and Swayze (2023), pushes women to the margins, with a devastating impact at the individual and organisational levels.

Finally, Cluster 3, positioned between ‘difficulties’ and ‘organisation’, shows how individual prejudices translate into structural barriers. The perception of ‘imbalances between sectors’, the difficulty in ‘managing balances’ and stereotypes about the interpersonal skills of young people and women (‘men have greater teamwork skills’) indicate that the challenge is not only interpersonal, but also managerial and cultural. These stereotypes hinder effective collaboration between generations, which is essential for promoting innovation (Wang & Duan, 2024), and create barriers to integration, as highlighted by the senior worker who describes relations with new recruits as ‘good office neighbours’.

In summary, the discussion of the results shows the public administration as an organisation in transition, rich in human and relational potential but at the same time afflicted by prejudices and discrimination that undermine its cohesion and effectiveness. The challenge for management and future policy will be to harness the potential (good relations, the drive for change) while actively addressing the difficulties (ageism, gendered ageism and management issues), transforming generational diversity from a risk into a real driver of public value.

5. Conclusions

This study explored work experiences within the Italian public administration at a time of profound demographic and technological change. The results revealed a complex map of the working environment, dominated by a fundamental tension between the potential offered by human relations and change, and the difficulties generated by deep-rooted prejudices and management challenges. In particular, the research highlighted the pervasiveness of ageism and, in an even more insidious form, gendered ageism.

The main conclusion of this work is that the success of the modernisation of the Public Administration (Presidency of the Council of Ministers, 2021) cannot be separated from a targeted investment in human and relational capital. Actively combating all forms of age and gender discrimination is not only an ethical imperative (World Health Organization, 2021), but also a strategic necessity in order to retain knowledge and skills (International Monetary Found, 2023), promote a positive organisational climate (Tahmaseb-McConatha et al., 2023) and unleash the innovative potential that arises from collaboration between different generations (Wang & Duan, 2024).

This study has some limitations. Due to the very nature of the study, the results obtained cannot be statistically generalised to the entire population of Italian civil servants. Furthermore, the use of snowball sampling may have introduced distortions in the selection of participants. However, the value of this work lies in the depth of the analysis, which offers a rich and contextualised understanding of the dynamics experienced by workers. There are many prospects for future research. It would be useful to conduct large-scale quantitative studies to measure the prevalence of the identified phenomena of ageism and gendered ageism and their correlation with performance and well-being indicators. Longitudinal studies could monitor the evolution of these dynamics over time, especially in relation to the implementation of new technologies and the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (Minister for Public Administration, 2024). Finally, intervention research could design and evaluate the effectiveness of training programmes and organisational interventions aimed at countering prejudice and promoting a truly inclusive and intergenerational work culture.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation: [C.C. and A.R.D.]; Methodology: [C.C.]; Formal analysis and investigation: [C.C. and A.R.D.]; Writing—original draft preparation: [C.C.]; Writing—review and editing: [A.R.D.]; Supervision: [A.R.D.]. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee for Psychological Research of the Department of Humanities at the University of Naples Federico II (prot. 22/2023 of 15/05/2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 |

Occurrence refers to the total number of words that make up the text. Form refers to each individual word, distinguished from others solely on the basis of its graphic structure, which may occur any number of times in a corpus or text. The lemma is the element to which a set of forms are referred, which are distinguished from each other because they are the result of the inflection of the same verb, noun or adjective. |

References

- Agency for Digital Italy (AgID). (2024). Three-Year Plan for Information Technology in Public Administration 2024–2026. Available online: https://www.agid.gov.it/it/pianificazione/piano-triennale (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Beery, S. L. B., & Swayze, S. (2023). Pushed out to pasture way before their time: Gendered ageism through the eyes of women working in the U.S. federal civil service. Cogent Gerontology, 2. [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [CrossRef]

- Bulman, T. (2021). Strengthening Italy’s public sector effectiveness. OECD. Available online: https://one.oecd.org/document/ECO/WKP(2021)41/en/pdf (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Butler, R. N. (1969). Age-ism: Another form of bigotry. The Gerontologist, 9(4), 243–246. [CrossRef]

- Capano, G., & Natalini, A. (2020). Public policies in Italy. Il Mulino.

- Cecil, V., Pendry, L. F., Ashbullby, K., & Salvatore, J. (2023). Masquerading their way to authenticity: Does age stigma concealment benefit older women? Journal of Women & Aging, 35(4), 428–445. [CrossRef]

- Donizzetti, A. R. (2015). The repercussions of ageism on career choices: The case of Italian workers. In M. Lagacé (Ed.), Representations and discourse on ageing: The hidden face of ageism? (pp. 173–190). Presses de l’Université Laval.

- Duncan, C., & Loretto, W. (2004). Never the right age? Gender and age-based discrimination in employment. Gender, Work & Organisation, 11(1), 95–115. [CrossRef]

- EBSCO. (2023). Ageing and the U.S. workforce. Available online: https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/economics/aging-and-us-workforce (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Fry, R. (2020). Millennials overtake Baby Boomers as America’s largest generation. Pew Research Centre. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2020/04/28/millennials-overtake-baby-boomers-as-americas-largest-generation/ (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- INAPP. (2023). Rise in older workers in Italy, 37% are over 50 years old. Available online: https://www.inapp.org/inapp-comunica/stampa/rise-in-older-workers-in-italy-37-are-over-50-years-old (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- International Monetary Fund. (2023). Italy: Selected issues (IMF Staff Country Report No. 2023/274).

- ISTAT. (2021). Annual report 2021—The situation of the country. Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/archivio/258542 (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- ISTAT. (2024). National demographic balance sheet—Year 2023. Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/archivio/296232 (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Itzin, C., & Phillipson, C. (1995). Gendered ageism. In C. Itzin & C. Phillipson (Eds.), Gender, culture and organisational change: Putting theory into practice (p. 81). Routledge.

- Johnson, G., Billett, S., Dymock, D., & Martin, G. (2013). The discursive (re) positioning of older workers in Australian recruitment policy reform: An exemplary analysis of written and visual narratives. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal, 32(1), 4–21. [CrossRef]

- Jyrkinen, M. (2014). Women managers, careers and gendered ageism. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 30(2), 175–185. [CrossRef]

- Lancia, F. (2004). Tools for text analysis. Introduction to the use of T-LAB. Franco Angeli.

- McCarthy, J., Heraty, N., Cross, C., & Cleveland, J. N. (2014). Who is considered an ‘older worker’? Extending our conceptualisation of ‘older’ from an organisational decision maker perspective. Human Resource Management Journal, 24(4), 374–393. [CrossRef]

- McGann, M., Ong, R., Bowman, D., Duncan, A., Kimberley, H., & Biggs, S. (2016). Gendered ageism in Australia: Changing perceptions of age discrimination among older men and women. Economic Papers: A Journal of Applied Economics and Policy, 35(4), 375–388. [CrossRef]

- McInnis, A., & Medvedev, K. (2021). Sartorial appearance management strategies of creative professional women over age 50 in the fashion industry. Fashion Practice, 13(1), 25–47. [CrossRef]

- Minister for Public Administration. (2024). The PNRR for the PA: Reforms and investments. Available online: https://www.funzionepubblica.gov.it/it/il-dipartimento/area-di-interesse/attuazione-delle-misure-pnrr/il-pnrr-per-la-pa-riforme-e-investimenti/presentazione/ (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Monahan, C., Zhang, Y., & Levy, S. R. (2023). COVID-19 and K-12 teachers: Associations between mental health, job satisfaction, perceived support, and experiences of ageism and sexism. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 23(2), 517–536. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, T. D. (2016). The age of ageism. Journal of Social Issues, 72(1), 191–198. [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2021). Ageing and talent management in European public administrations. OECD Publishing. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/gov/pem/ageing-and-talent-management-in-european-public-administrations.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Presidency of the Council of Ministers. (2021). National recovery and resilience plan—#NextGenerationItalia. Available online: https://www.italiadomani.gov.it/il-piano/il-piano-completo.html (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Rocha, J. O., & Zavale, G. J. (2021). Innovation and change in public administration. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 9(6), 285–297. [CrossRef]

- Sigurðardóttir, S. H., & Snorradóttir, Á. (2020). Older women’s experiences in the Icelandic workforce-positive or negative? Nordic Journal of Working Life Studies, 10(4). [CrossRef]

- Tahmaseb-McConatha, J., Kumar, V. K., Magnarelli, J., & Hanna, G. (2023). The gendered face of ageism in the workplace. Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal, 10(1), 528–536. [CrossRef]

- Van der Voet, J. (2016). Change leadership and public sector organisational change: Examining the interactions of transformational leadership style and red tape. The American Review of Public Administration, 46(6), 660–682. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L., & Duan, X. (2024). Generational diversity and team innovation: the roles of conflict and shared leadership. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1501633. [CrossRef]

- World Economics. (2025). Italy’s working age population. Available online: https://www.worldeconomics.com/Population-Of-Working-Age/Italy.aspx (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- World Health Organisation. (2021). Ageism is a global challenge. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/18-03-2021-ageism-is-a-global-challenge-un (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Yi, Y., Song, X., & Choi, K. (2022). Age and workplace ageism: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 66(4), 629–650. [CrossRef]

- Zacher, H., & Rudolph, C. W. (2023). The construction of the ‘older worker’. Merits, 3(1), 115–130. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).