1. Introduction

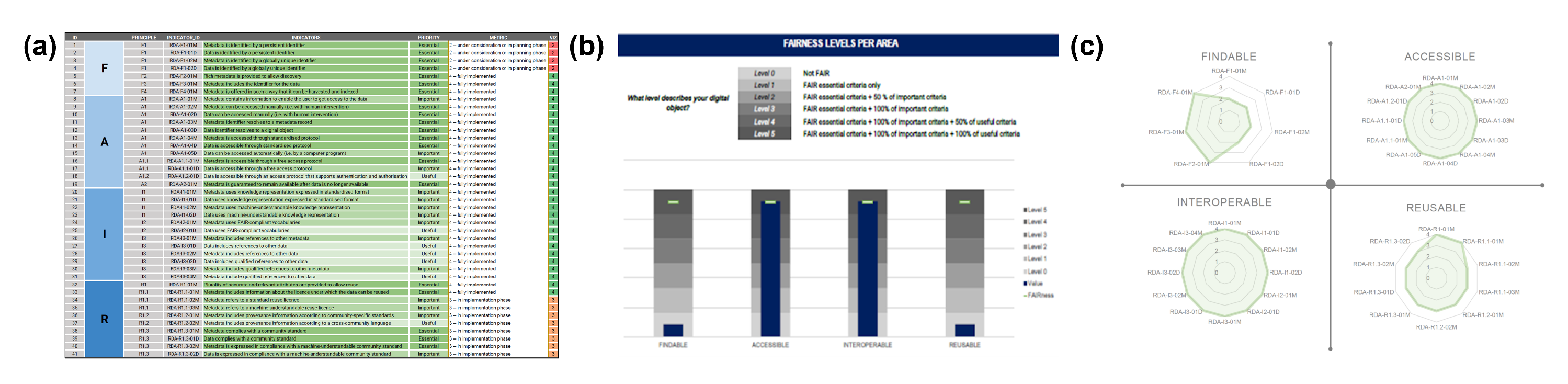

The Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage (UNESCO, 1972) defined both cultural and natural heritage as assets of universal value that humanity must collectively preserve. According to UNESCO, natural heritage encompasses geological formations, biological manifestations representing ecological processes, and outstanding natural landscapes, with the objective of safeguarding the intrinsic universal value of nature itselfc [

1]. As of 2025, there are 1,248 World Heritage properties, including 972 cultural, 235 natural, and 41 mixed sites [

2]. While cultural heritage records the creative imprints of humankind, natural heritage serves as an environmental record system that bears witness to the geological and biological processes predating human existence—an archive of nature that preserves the long-term chronicle of life and the Earth’s transformations.

In recent years, the digital transformation of heritage—including natural heritage—has become a key infrastructure across diverse domains such as conservation science, biodiversity research, ecological education, and exhibition [

3]. With the advancement of high-precision technologies such as photogrammetry, structured-light scanning, LiDAR, X-ray, and computed tomography (CT), large-scale digitization of natural history specimens has rapidly expanded. However, most institutions remain in the production-oriented stage of this process [

4]. Although various techniques—such as photogrammetry, structured-light scanning, and CT imaging—are used to digitize natural history specimens [

5], the resulting 3D data exist in heterogeneous file formats including OBJ, FBX, PLY, STL, and glTF [

6]. Since each institution develops and manages data according to its own internal standards, interoperability remains low, and geometric data are often stored separately from metadata. This fragmented practice hinders the ability to capture temporal and contextual changes comprehensively [

7]. The lack of an integrated digital framework remains a critical obstacle to the long-term preservation and reuse of natural heritage data, as quantitative advances in digitization have not been matched by qualitative progress in management and utilization.

Within this context, the field of biodiversity informatics has introduced the concept of the Digital Extended Specimen (DES) [

8,

9]. The DES model seeks to manage a specimen as an extended digital object that links the physical specimen with genomic, geographic, ecological, and environmental data from various third-party sources. This approach has been recognized as a concrete means of implementing the principles of findability, accessibility, interoperability, and reusability (FAIR), thereby maximizing both the research value of specimens and the usability of associated data [

10]. However, DES efforts remain primarily focused on biological taxonomy and specimen-level data, with limited attention to heritage-related or community-based contexts [

11]. In other words, natural heritage continues to be perceived mainly as an ecological entity, while its identity as a repository of universal human value—emphasized by UNESCO—has not been fully incorporated. Hence, the digital management framework for natural heritage must evolve beyond the specimen-centered approach to address environmental, communal, and cultural memory dimensions in an integrated manner.

Against this background, the European Union has developed the SYNTHESYS3 project to establish a collaborative digital platform for natural heritage [

12]. Based on the Virtual Access model, this platform aims to integrate specimen data from 21 institutions across Europe and enhance accessibility for researchers. However, its data infrastructure remains largely grounded in text-based records such as specimen labels, field notes, and collection diaries, with limited integration of visual or morphological datasets. This limitation hampers the multidimensional connectivity and visual reusability required by the DES concept, constraining the representation of the spatial and contextual attributes intrinsic to natural heritage data. Consequently, while significant progress has been made in improving accessibility, challenges persist regarding data diversity, structural integration, and semantic interoperability.

In contrast, the cultural heritage domain has witnessed the emergence of new systems that integrate metadata and paradata to enhance data reliability and interpretive transparency in digital restoration and 3D reconstruction processes [

13,

14]. Notably, the Memory Twin concept extends the conventional Digital Twin paradigm—originally centered on physical structure simulation—into a holistic framework integrating data, metadata, and paradata [

15]. Beyond ensuring geometric accuracy, it transparently documents the decisions and processes underlying data creation and functions as a participatory digital model that preserves collective memory, cultural identity, and narrative meaning. Building upon Holistic Heritage BIM (HHBIM), the framework integrates the material, social, and emotional dimensions of heritage, establishing an ethical and participatory data ecosystem aligned with the FAIR and CARE principles. Ultimately, the Memory Twin signifies a paradigm shift in cultural heritage data management—transforming visual reproduction into a semantic and narrative framework that connects past and present, communities and technologies.

Building upon these discussions, this study aims to establish a foundation for enhancing the reliability and reusability of natural heritage data by encompassing the entire 3D data lifecycle—from high-fidelity 3D digitization processes specialized for natural heritage to the design of a knowledge-graph database that integrates data, metadata, and paradata, and the development of a collaborative information management and retrieval environment. Through this approach, the study proposes an expanded digital management ecosystem for natural heritage that moves beyond specimen-centered technical systems to encompass both heritage and digitization contexts.

2. The State of the Art

2.1. Natural Heritage 3D Digitization and the Digital Extended Specimen

Over the past two decades, the digitization of natural heritage has evolved primarily to enhance the accessibility of records and specimens. However, most existing studies have focused on the digital conversion of text and image-like transcription, while methodological discussions on systematically implementing contextual relationships between generated data remain limited. Consequently, natural heritage digitization has not sufficiently reflected the interrelations among the physical attributes, spatial and temporal contexts, and associated records of specimens, nor has it provided diverse exploration methods or relational interpretations.

Examples such as OCR-based transcription technologies adopted by major U.S. natural history institutions and the digitization of handwritten archives at Harvard University [

16] have improved accessibility but still rely on static, text-centered structures. These projects lack a systemic approach to reconstruct semantic relationships among data. Similarly, 3D digitization technologies—such as CT scanning or structured-light scanning—have expanded efforts to document morphological precision (e.g., the openVertebrate project), yet discussions on data quality improvement remain focused on issues such as misidentification, spelling errors, and formatting inconsistencies in transcription datasets [

17]. Research on the optimization of scanning workflows or models for managing 3D scan data remains sparse. The ICEDIG survey revealed that more than half of respondents conducted digitization tasks independently using local tools such as Excel or Access, with management units inconsistently defined at the specimen or taxonomic levels [

18]. This indicates that digitized resources remain fragmented, dependent on individual annotations and interpretations, and lack integration into centralized quality control systems.

To address these limitations, the Digital Extended Specimen (DES) concept links physical specimens with genomic, environmental, and ecological data through persistent identifiers (PIDs) [

8]. Grounded in the goal of transforming individual specimens into machine-readable knowledge networks by relationally connecting their multilayered information, the DES underscores the need for a data management framework that moves beyond text- and image-based transcription systems to capture the complex characteristics and contexts of specimens. This perspective suggests that the digitization of natural heritage should evolve from the mere digital conversion of physical resources toward the reorganization of knowledge structures based on inter-data relationships. Within this evolutionary process, the need to standardize 3D data production and management systems becomes increasingly evident to enhance the reliability and explainability of natural heritage data.

2.2. Evolution of Natural Heritage Data Management Environments as Collaborative Ecosystems

As an alternative to static digitization structures, platform-based biodiversity information infrastructures have emerged, emphasizing connectivity, standardization, and collaborative curation. Arctos, DiSSCo, GBIF, iDigBio, and BHL are representative international collaborative data management systems developed under these principles. However, the data architectures of these platforms remain primarily designed around biological specimen information flows, offering limited capacity to represent not only the contextual and cultural dimensions of natural heritage but also the processual contexts of digital workflows that underpin its authenticity and interpretive transparency.

Based on the comparative analysis summarized in

Table 1, three strategic directions can be identified. First, a transition toward

`object-centric data models’. Arctos and DiSSCo define each specimen or digital object as a fundamental management unit, achieving scalability through interconnected relational structures [

19,

20]. Second, the establishment of interoperability frameworks grounded in the

`FAIR principles’. GBIF and iDigBio adopt RDF and JSON-LD formats to strengthen cross-domain connectivity and improve data accessibility through persistent identifier (PID) systems and GraphQL APIs [

21,

22]. Third, a

`metadata-centered federation’ strategy. BHL and iDigBio maintain data in their original institutional repositories while integrating metadata and linking information for centralized discovery [

16,

22].

Despite these strategic advancements, contextual limitations persist. Excessive emphasis on formal interoperability has often overlooked semantic integration capable of interpreting the relational contexts of specimens, including their micro, social, and heritage dimensions. As a result, structural scalability for representing and analyzing high-dimensional data—such as 3D scans, geospatial information, and multi-taxonomic hierarchies—remains limited. Moreover, participatory curation frameworks largely confined to expert communities hinder cyclical governance among data producers, managers, and users. For instance, while Arctos promotes transparency through its community model, general user participation remains restricted [

19], and GBIF has been criticized for institutional bias in data provision [

21]. Taken together, these findings suggest that existing platforms have advanced technological interoperability within specimen-based management systems but now need to evolve toward intelligent models capable of integrating the diverse user dynamics and complex cultural, geographical, and social contexts of natural heritage.

2.3. Multi-Layered Structure of Natural Heritage Standardization

The standardization of natural heritage data originated from Linnaean taxonomy and the international nomenclature codes of the nineteenth century, evolving as a historical process to describe biological information in a common language. However, with the widespread adoption of three-dimensional digitization technologies, the structural limitations of existing standards have become increasingly evident.

The Darwin Core (DwC) serves as a core standard for biodiversity data exchange, defining attributes such as taxonomy, specimens, and locality, thereby establishing the foundation for international interoperability. Nevertheless, DwC is designed as a text-based, two-dimensional structure that cannot systematically describe the geometric properties, resolution, file formats, or relationships between derived versions of 3D models. The ABCD schema, based on XML, expresses semantic relationships between specimens with greater precision, yet lacks mechanisms for structurally representing the digitization process and the technical properties of digital objects. For instance, contextual information about digitization—such as scanner specifications, scan resolution, and post-processing software—is not defined as standardized fields, making it difficult to assess data reproducibility and reliability.

The Audubon Core provides a metadata standard for multimedia resources but is primarily designed for two-dimensional media; it does not explicitly address the management of multi-resolution levels of detail (LOD), the provenance of derived models, or compatibility with 3D viewers. The Dublin Core coordinates interoperability at a higher level of abstraction but remains too general to describe the technical life cycle of digital objects in detail. Similarly, the FAIR principles emphasize data accessibility and reusability but do not include evaluation metrics for 3D data quality—such as mesh integrity, texture resolution, or geometric accuracy. The CARE principles address ethical control over data use, yet they have not been extended to cover the management of paradata.

Current standardization efforts remain largely centered on the physical attributes of specimens, failing to structurally represent the digitization process and the technical context of digital objects. When identical specimens are digitized using different scanning methods, the absence of paradata—such as information on equipment specifications, resolution settings, and post-processing algorithms—prevents researchers from assessing the scientific suitability of the resulting 3D models and undermines the reliability of digital resources. In the cultural heritage domain, attempts have been made to model digitization processes ontologically through CRMdig, an extension of the CIDOC-CRM. However, CRMdig was designed primarily for the cultural heritage domain and thus does not integrate natural science–specific attributes such as biological taxonomy, collection data, or interspecies relationships. Its interoperability with standards such as Darwin Core and ABCD also remains undefined. Therefore, the standardization of natural heritage data requires an integrative effort to connect biological standards (DwC, ABCD) with cultural heritage digitization standards (CRMdig) and to explicitly represent the inherent properties of three-dimensional data.

2.4. The Necessity of Metadata and Paradata

As digitization technologies for natural heritage continue to advance and data management environments diversify, three-dimensional (3D) data have become essential resources for accurately capturing the morphological characteristics of specimens. However, current standard frameworks lack an integrated structure capable of managing the spatial properties, processing workflows, and quality information of 3D data within their full contextual settings. To address these limitations, the importance of a three-layered structure comprising data, metadata, and paradata has been demonstrated through the Tendaguru Dinosaur Expedition—a century-long digitization project of paleontological data initiated in 1909—showing that such an approach is critical for integratively documenting excavation contexts, taxonomic revisions, and physical conservation histories [

23]. In particular, paradata—including scanner specifications, resolution parameters, and post-processing workflows—were reported to account for approximately 80–90% of the total dataset, serving as a crucial component in ensuring the reproducibility and scientific credibility of 3D models. Nevertheless, this model was developed to satisfy project-specific requirements and was not intended for inter-institutional collaboration or broad standardization. In contrast, the cultural heritage domain has undertaken earlier initiatives toward the systematic standardization of 3D data management. Within the EUreka3D project, 3D cultural heritage objects were conceptualized as complex digital entities composed of point clouds, meshes, and textures, emphasizing the need to record both the technical quality of data and the interpretive context of their creation [

24]. To realize this, four interconnected infrastructure types—data repositories, aggregators, viewers, and virtual research environments—were proposed, demonstrating that an interoperable management framework can be achieved through their organic integration. However, this approach remains limited when applied to natural heritage, as it fails to represent hierarchical structures such as specimen–collection–institution relationships, dynamic changes in biological taxonomy, and interspecies interactions. The crucial role of semantic linkage of spatial data in the integrated management of natural and cultural heritage has been widely recognized [

25]. Through the semantic interconnection of geospatial and heritage data using frameworks such as the INSPIRE Directive, CRMgeo, and GeoSPARQL, 3D models can function not merely as visual artifacts but as semantic nodes that holistically encapsulate ecological, geological, and historical contexts. In this regard, the establishment of standardized interfaces and identification mechanisms is essential to ensure interoperability between 3D datasets and broader spatial information infrastructures. Although diverse approaches to 3D data management have been proposed, most existing projects remain tailored to specific contextual needs, leading to limited interoperability and adoption across institutions. Therefore, for 3D data to attain scientific reliability and enable collaborative reuse, it is imperative to move beyond isolated technical implementations and establish an integrated infrastructure grounded in validated standards and interoperable tools.

3. Methodology

Over the past several decades, the digitization of natural heritage has advanced through technically oriented approaches such as OCR-based transcription techniques, error correction for misidentification and misspellings, and the refinement of data quality management systems. While biodiversity data standards such as Darwin Core, ABCD, and Audubon Core have ensured a certain level of technical interoperability, these standards remain limited in their ability to fully capture the physical precision, heritage and cultural values, and contextual information (paradata) generated during the digitization process. This indicates that current natural heritage data management systems must evolve beyond the mere provision of "accurate information" toward becoming interpretive knowledge resources that integrate meaning, provenance, and contextual understanding.

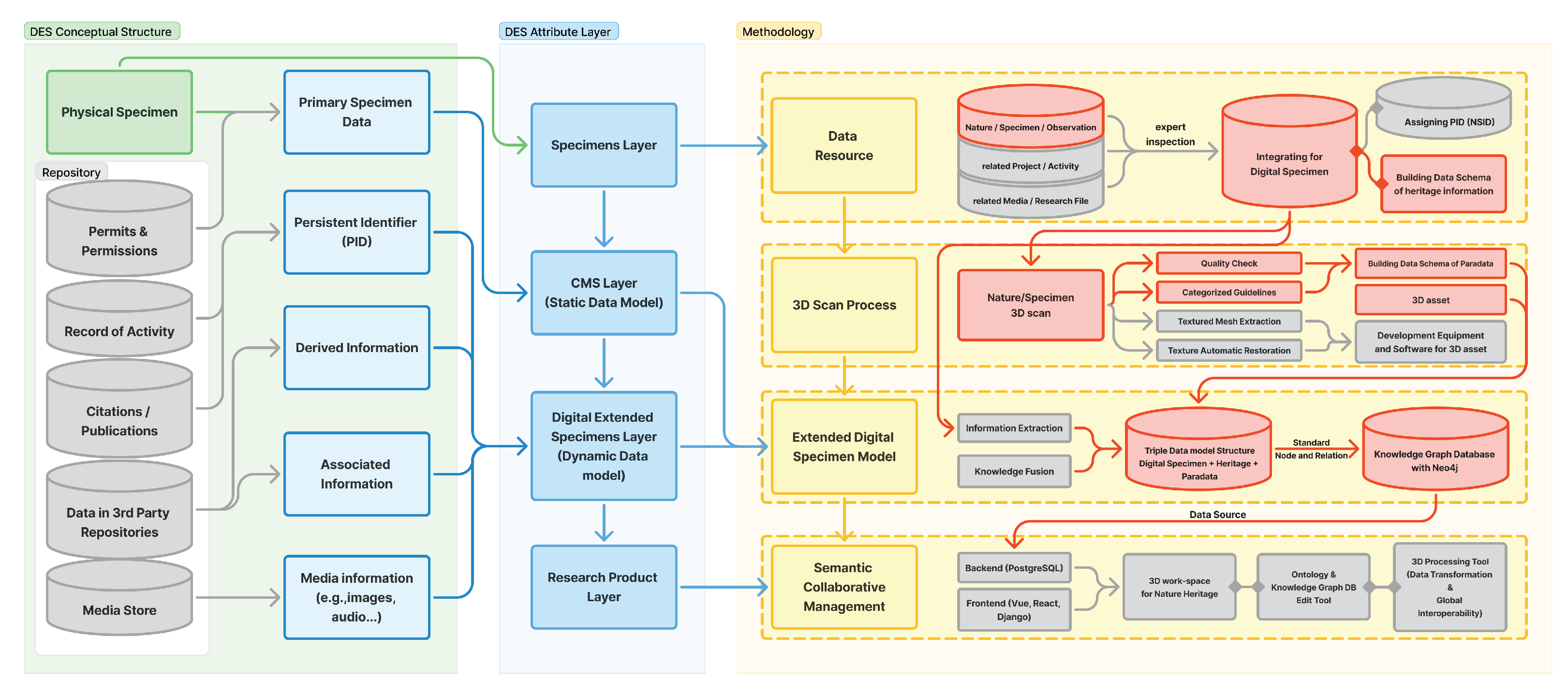

To address these limitations, this study proposes an integrated research methodology grounded in the concept of the Digital Extended Specimen (DES) [

8]. The DES represents a multilayered data structure that extends from a physical specimen through its linkage with Collection Management Systems (CMS), human annotations, and machine-driven transactions, thereby enabling a comprehensive representation of the scientific, technical, and cultural contexts of the specimen. Based on the three-layered structure of the DES—Data, Metadata, and Paradata—this study designed a systematic framework encompassing the entire lifecycle of natural heritage data, from production and management to utilization.

This integrated framework is implemented through four functional phases:

Data Acquisition & Normalization: Collects and consolidates dispersed natural heritage specimens from multiple institutions, standardizing terminology and formats to establish a unified foundational dataset.

3D Digitization: Establishes a hyper-reality 3D scan workflow optimized for natural heritage by combining structured-light scanning and photogrammetry. Environmental parameters (temperature, humidity, illumination) and algorithmic settings are controlled to ensure the reproducibility and quality reliability of the acquired data.

Knowledge Graph Database: Designed through ontology integration, semantically interlinks biological data (Darwin Core), heritage value data (CIDOC-CRM), and digitization process data (CRMdig, PROV-O), constructing a knowledge graph-based data structure (E-DNH Ontology) that integrates biological, cultural, and technical dimensions.

Collaborative Management & Utilization: Integrates OpenSearch-based semantic search, AI-driven quality assessment, and real-time annotation within a cloud environment, while implementing a persistent identifier (PID) system (Handle/DOI) to ensure interoperability with global infrastructures such as DiSSCo and GBIF.

These four phases operate in conjunction with the three-tiered DES model, which serves as the conceptual and ontological foundation of the proposed methodology. The DES model defines the semantic hierarchy of data, metadata, and paradata, while the four functional phases implement this hierarchy through the processes of data acquisition, 3D digitization, ontology-based structuring, and collaborative utilization. Together, they constitute an integrated system architecture that enables a cyclic flow of data production, management, and reuse. As illustrated in

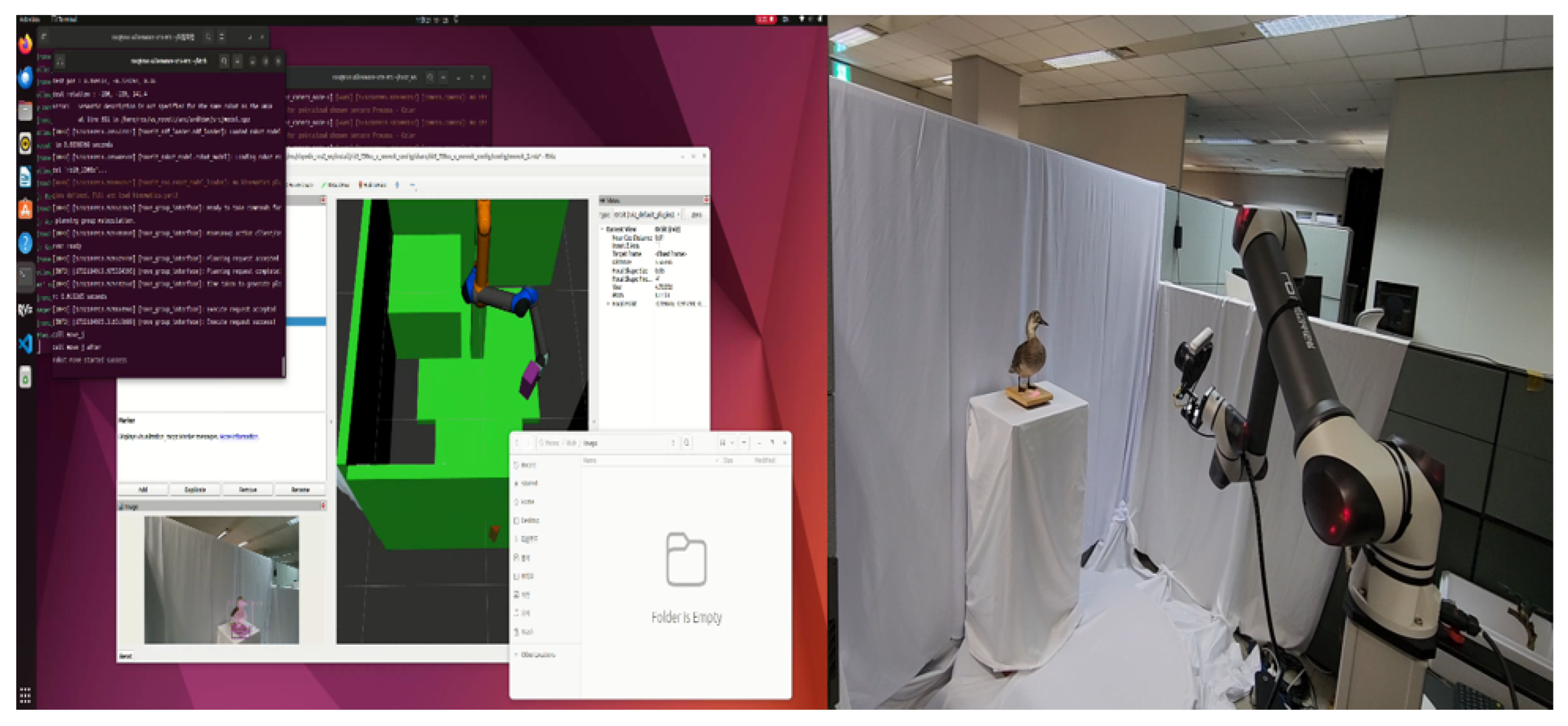

Figure 1, this framework interlinks all phases through shared semantic layers, allowing biological information, technical contexts, and cultural values to be managed within a unified, intelligent collaborative environment. Ultimately, the proposed framework advances beyond a technology-driven linear model of digitization by ensuring data reliability, reusability, and semantic interoperability, thereby establishing a sustainable and transparent digital ecosystem for natural heritage.

3.1. Data Resource Layer

The first stage of this study focuses on constructing the Data Resource Layer, which serves as the foundational basis for the Extended Digital Nature Heritage (E-DNS) Ontology. This layer involves the physical acquisition of natural heritage specimens and the normalization of their descriptive data, thereby establishing a systematic foundation for subsequent 3D digitization and ontology design processes.

This research was conducted through collaboration among the Hannam University Natural History Museum, the Natural Monument Center, and Seoul Grand Park, targeting a total of 197 natural heritage specimens. The dataset comprises 135 avian specimens (68.5%), 49 insect specimens (24.9%), 10 mammalian specimens (5.1%), and 3 reptilian specimens (1.5%). Institutional roles were clearly divided: Hannam University was responsible for the digitization of small to medium-sized vertebrate specimens (fish, amphibians, reptiles), while the Natural Monument Center provided metadata and persistent identifiers (PIDs) for nationally designated natural monument species. The composition of specimens and institutional responsibilities is summarized in

Table 2.

Specimen selection was based on a comprehensive review of preservation environments, data management systems, and photographic and scanning feasibility within each institution. For each specimen, primary metadata—including scientific name, taxonomic hierarchy, collection site, collection year, and collector—were standardized, while parameters affecting digital quality—such as camera angle, lighting conditions, and preservation state—were systematically managed. Through this process, heterogeneous institutional data formats were unified, establishing a standardized data foundation scalable to the higher layers of the E-DNS Ontology. The detailed structure of specimen metadata normalization and quality control parameters is presented in

Table 3.

An expert advisory workshop, involving specialists from the Natural Monument Center and the Korea National Park Service, was convened to discuss scanning quality control, data linkage mechanisms, and the development direction of the “Nature Asset” repository. Based on the workshop outcomes, data normalization criteria were refined to address inconsistencies in taxonomic identification, storage environments, and metadata description levels across institutions. Furthermore, improvements were proposed for inter-specimen relationship modeling and the persistent identifier (PID) structure.

The datasets established in this stage comprise three primary categories: (1) specimen attributes, encompassing taxonomic, biological, and preservation-related information; (2) project-based data, capturing digitization workflows, institutional collaborations, and process-related paradata; and (3) heritage records, including historical documents and ecological narratives that contextualize specimens within cultural and environmental dimensions. Together, these heterogeneous datasets were integrated into a unified and standardized schema, providing interoperability across institutions and establishing a scalable foundation for the upper layers of the DES framework—namely, 3D digitization and ontology-based semantic integration. Consequently, the Data Resource Layer forms the core structural backbone of the natural heritage data ecosystem, ensuring the integrity, consistency, and long-term reusability of specimen-related information across collaborative and multi-institutional infrastructures.

The subsequent sections elaborate on the higher layers of the proposed framework. Section 4 presents the 3D Scanning Layer, which establishes a hyper-reality 3D digitization workflow optimized for natural heritage specimens. Sections 5 and 6 further describe the Knowledge Graph Database Layer, centered on the Extended Digital Natural Heritage (E-DNH) Ontology, and the Collaborative Management & Utilization Layer, which implements a semantic, cloud-based platform for cooperative data management and reuse.

4. Higher-Reality 3D Digitization Workflow for Natural Heritage

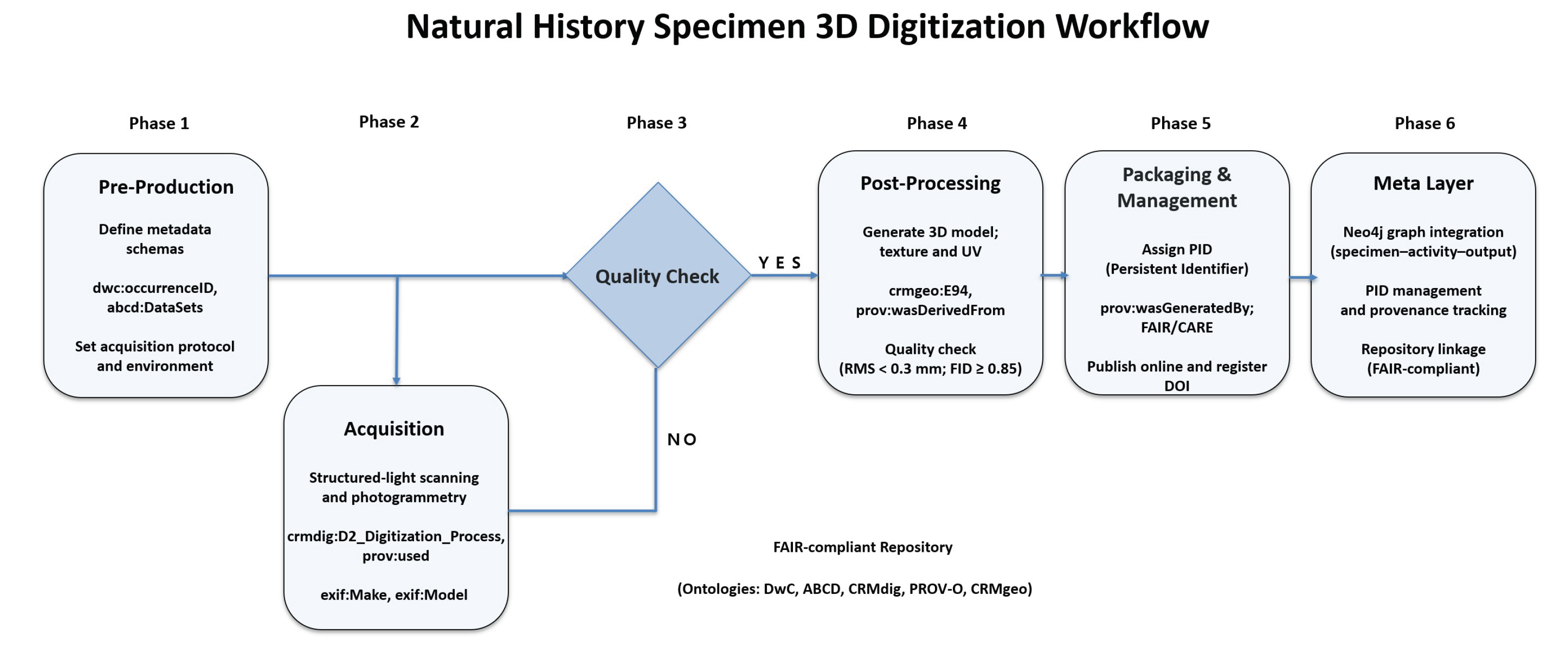

The 3D digitization workflow proposed in this study was designed not merely as a visual modeling process but as an integrated system that simultaneously generates data, metadata, and paradata. The workflow, as illustrated in

Figure 2, consists of six sequential stages: pre-production, acquisition, quality assurance and control (QA/QC), post-processing, packaging, and meta-layer integration.

4.1. Pre-production

In the pre-production stage, physical characteristics of specimens and environmental parameters were quantitatively defined, and all device settings and protocols were standardized to ensure reproducibility. All scanning sessions were conducted under controlled environmental conditions of 20 ± 2 °C temperature and relative humidity, using diffuse LED panels (1000–1500 lux, 5500 K color temperature, CRI > 95) for uniform lighting. Cross-polarizing filters were applied to minimize specular reflections on glossy surfaces.

A structured-light scanner (Artec Space Spider) with a point accuracy of 0.05 mm at 16 fps was used for geometry capture, capable of reconstructing fine morphological details such as scales, feathers, and skin textures. A motorized turntable system (360° rotation, 5° interval) enabled automated multi-angle scanning across 48 positions and four elevation levels. For texture acquisition, a Sony α7R V camera (61 MP, 35 mm f/1.4, ISO 100) was used, producing an average of 12,000–25,000 high-resolution frames per session. All parameters, including equipment specifications, operator IDs, and environmental variables, were documented as PROV-O–based paradata and stored as event nodes in the Neo4j database.

Table 4 summarizes the major equipment and specifications used for the 3D digitization process. The structured-light scanner (

Artec Space Spider) achieved a point accuracy of 0.05 mm and was used for close-range geometry capture. The DSLR camera (

Sony α7R V) provided 61 MP resolution for texture acquisition. The turntable system (RB10-1300) featured 360° rotation with 5° intervals and 48 positions, enabling automated scanning sequences. Diffuse LED panels (1000–1500 lux, 5500 K, CRI > 95) ensured uniform illumination conditions.

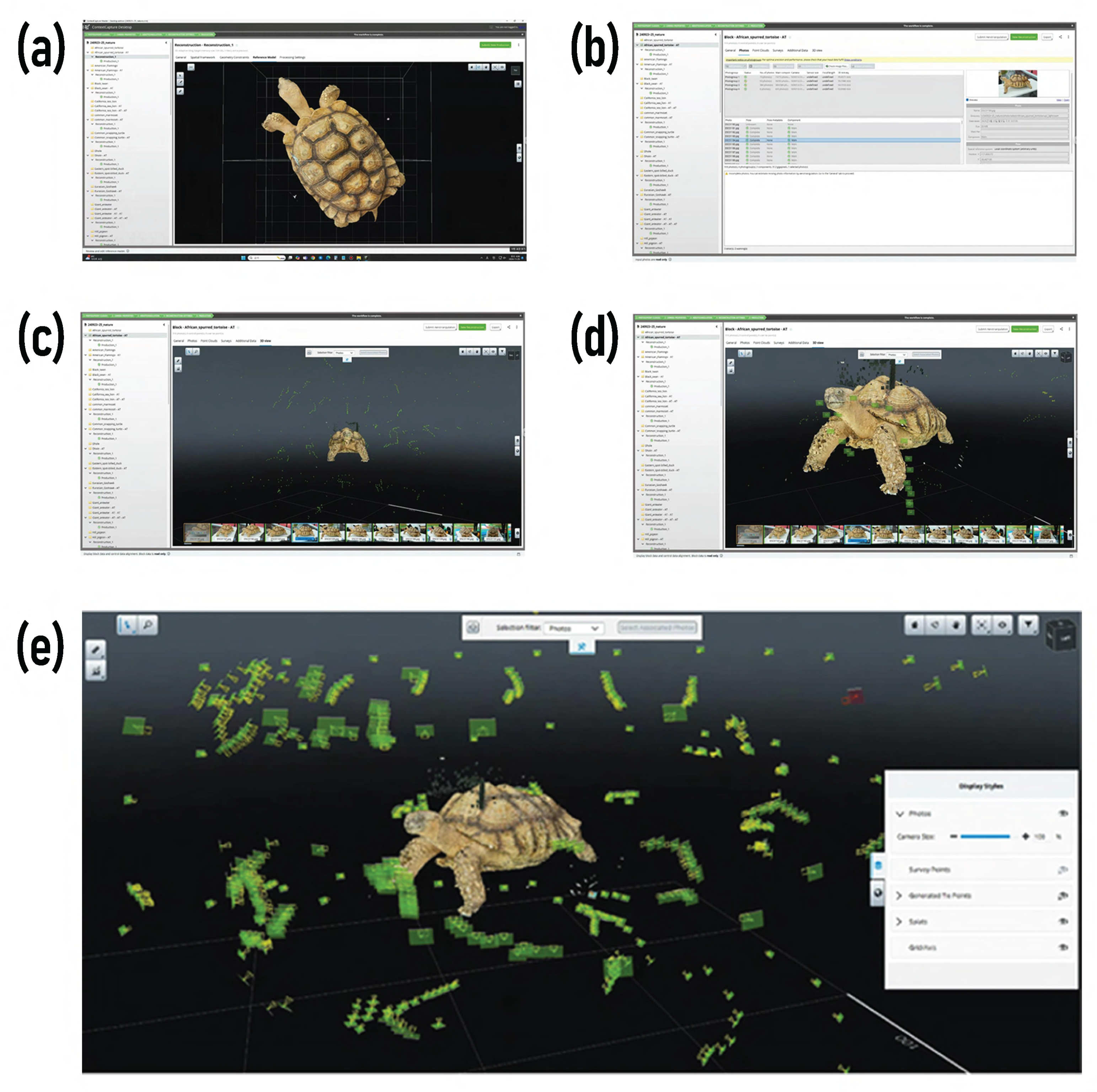

4.2. Acquisition

The acquisition process adopted a hybrid approach combining structured-light scanning and photogrammetry. Small- and medium-sized specimens were captured at a distance of 25–30 cm using the

Artec Space Spider with 70% frame overlap, while occluded regions were detected in real time and re-scanned. For larger specimens, a robotic rig captured 192 RAW images at 80% overlap and 30–60° cross-angles, processed in

Agisoft Metashape 2.1.2 using Structure-from-Motion (SfM) and Multi-View Stereo (MVS) algorithms. Photogrammetric alignment and dense point-cloud reconstruction were performed in

ContextCapture, as visualized in

Figure 3.

4.3. Quality Assurance & Quality Control (QA/QC)

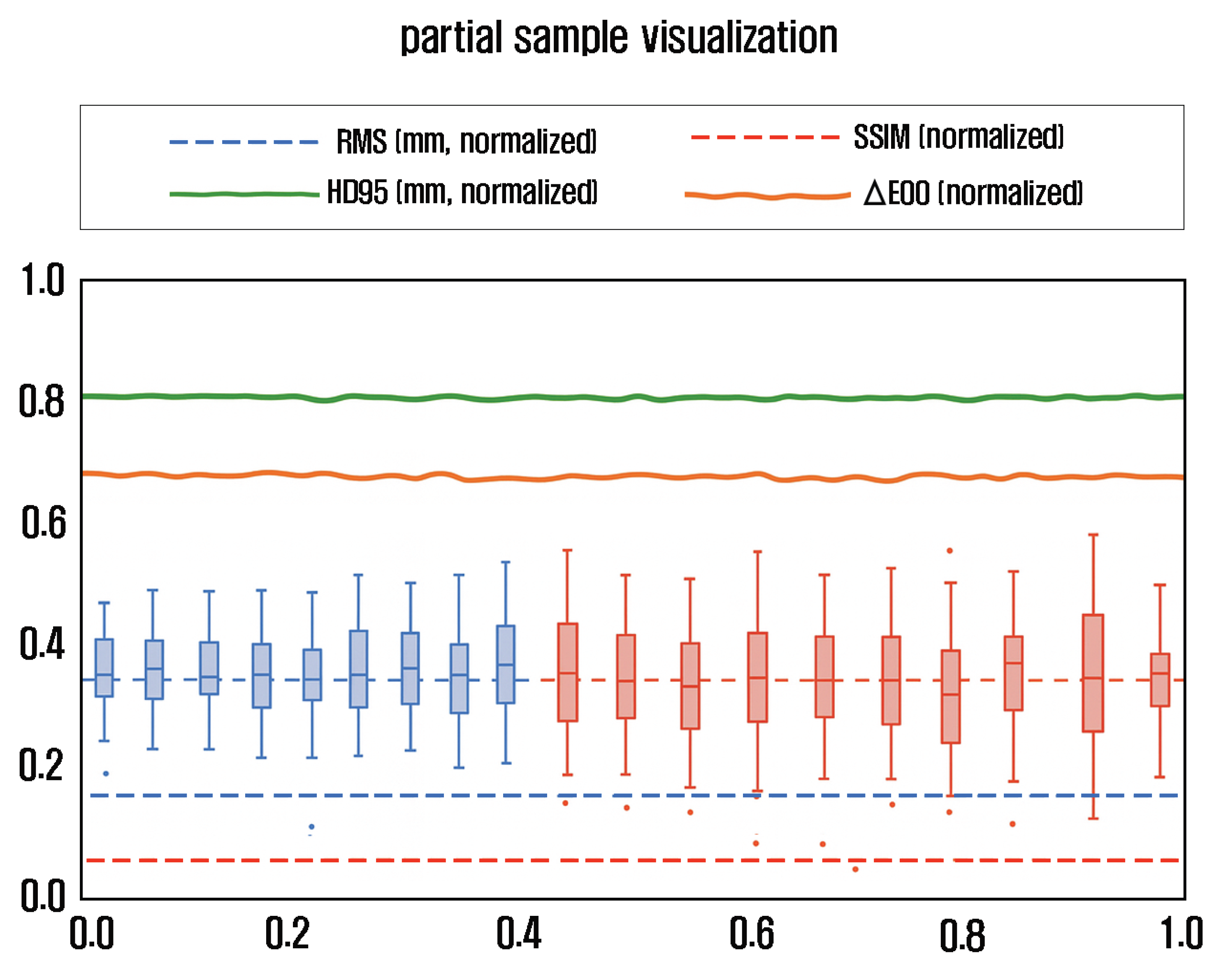

A total of 197 3D digital specimens were subjected to quality assurance and control. Among them, 20 samples (approximately 10%) were randomly selected for validation. All data were acquired under identical environmental and equipment conditions—Artec Space Spider, 20 ± 2 °C, 45 ± 5% RH, 1000–1500 lux LED, 5500 K, CRI > 95—with a QC tolerance maintained within ±2%. This range ensured statistical stability of geometric and visual quality metrics.

Geometric accuracy was assessed using Root Mean Square Error (RMS), Hausdorff Distance (HD95), and Chamfer Distance, while visual fidelity was evaluated via Structural Similarity Index (SSIM), color difference (CIEDE2000), and Fréchet Inception Distance (FID). An RMS threshold of 0.3 mm was established based on Smith et al. (2019) and the minimum morphological unit (for example, a fish scale of approximately 0.5 mm). Each metric compared reconstructed models with original data: RMS Error for geometric congruence, for color accuracy, and SSIM/FID for textural similarity. Results showed RMS 0.18 ± 0.09 mm, 2.1 ± 0.7, and SSIM 0.92 ± 0.03, confirming that all specimens met the defined thresholds. These results demonstrate precision suitable for both academic and exhibition applications, providing a reliable basis for Digital Extended Specimen (DES)-based semantic integration and long-term preservation.

Table 5 presents the quantitative QA/QC metrics and acceptance criteria, while

Figure 4 visualizes the distribution of these indicators across the evaluated samples. RMS Error, HD95, and Chamfer Distance were used to evaluate geometric accuracy, whereas SSIM,

, and FID assessed texture fidelity. The results indicate that all models satisfied the target thresholds (RMS ≤ 0.3 mm, SSIM ≥ 0.95,

≤ 3.0), demonstrating high consistency in both geometric and visual quality. Quality data were stored in Neo4j (

:QualityCheck) nodes for traceability, and any sub-threshold dataset was automatically reassigned for re-acquisition.

Figure 4 illustrates the normalized distribution of RMS, HD95, SSIM, and

across 20 randomly selected specimens, confirming that all samples remained within the acceptance thresholds defined in

Table 5.

Table 6 summarizes workflow-level metrics, showing average processing time, data volume, automation ratio, and QC pass rate at each stage. The average acquisition took 45 minutes per specimen, with 15–30 GB of raw data, and achieved a 98% QC pass rate.

4.4. Post-processing

In the post-processing stage, operations included Iterative Closest Point (ICP) alignment, TSDF fusion, noise removal, remeshing, normal recalculation, UV unwrapping, 8K texture baking, and color correction. Blender 4.0.2 and Artec Studio 18 were jointly used, applying ColorChecker matrices to maintain ≤ 2.1. Photogrammetric and structured-light datasets were merged, combining high-resolution textures with precise geometry, achieving 100% watertight meshes. Each finalized model underwent multi-stage QA validation prior to metadata integration.

4.5. Packaging and Management

Final outputs were produced in a three-tier structure for preservation, analysis, and web distribution: OBJ (0.5–2 GB) for archival storage, PLY (2–5 GB) for analytical use, and GLB (50–200 MB) for web-based visualization. Each file received a Darwin Core identifier (dwc:occurrenceID) and a cryptographic checksum, packaged using the BagIt format, and transferred to an OAIS ISO 14721:2012-compliant long-term preservation system.

4.6. Meta-Layer Integration

The objective of this stage was to identify and structure the contextual (paradata) and evidential elements generated throughout the digitization process. Beyond simple data integration, this step clarifies how technical operations, tools, and human decisions influence the interpretive and representational fidelity of digital natural heritage assets. Unlike cultural heritage, natural heritage digitization must accommodate biological variability and irreversible temporal change. Thus, each scanning act functions as an evidential event, reflecting environmental, instrumental, and procedural contexts that directly affect reproducibility and scientific reliability. Technical and environmental variables—illumination, humidity, LiDAR parameters, scanning angles—were quantitatively recorded, and their correlations with geometric accuracy, textural fidelity, and reconstruction quality were analyzed. Paradata elements specific to natural heritage 3D digitization were categorized into three analytical scopes: (1) physical context, covering scanning environment, specimen mounting, and device resolution; (2) computational context, including alignment algorithms and texture mapping parameters; and (3) interpretive context, involving AI model selection, manual editing, and quality threshold criteria. These analytical categories and their corresponding elements are summarized in

Table 7.

These three categories structure the digitization process as a chain of evidence, process, and result, where each paradata record corresponds to ontology classes such as AcquisitionEvent, DataProcessing, and QualityAssessment. This meta-paradata analysis exposes the methodological layers embedded in the creation of digital natural heritage data, allowing precise tracing of how technical procedures and human interpretations collectively construct the digital specimen. Through this approach, the digital specimen is redefined not as a mere visual replica but as an evidence-based composite digital object that integrates scientific observation, technological reconstruction, and interpretive transparency—forming the foundation for the Extended Digital Natural Heritage (E-DNH) ontology model introduced in the following sections.

5. Extended Digital Natural Heritage Ontology

5.1. Purpose

Natural heritage is not only valuable as a biological entity but also represents the complex accumulation of human acts of perception, documentation, and preservation. However, existing digital archiving systems have failed to sufficiently reflect this multilayered nature, remaining largely at the level of metadata management focused on physical specimens. This study, therefore, conceptualizes natural heritage not as a single dataset but as an ecosystem of knowledge, and proposes an Extended Digital Natural Heritage (E-DNH) ontology to systematically describe the structure in which observed nature, heritage value, and digital processes mutually interact.

First, the proposed ontology provides a semantic nexus for knowledge integration. A natural heritage entity may be seen as a taxonomic specimen, a conservation target, or a digital source object, depending on disciplinary perspectives. When such viewpoints use distinct vocabularies and data structures, integrated reasoning becomes difficult. The E-DNH ontology connects these perspectives through a shared semantic model, enabling cross-domain queries and reasoning.

Second, it makes implicit knowledge explicit. Scientific, political, and technical knowledge accumulated during heritage collection, registration, and digitization often remains undocumented. By formalizing this tacit expertise into explicit relations and logical constraints, the ontology supports knowledge transmission and reuse.

Third, it offers a shared language for multidisciplinary collaboration. Biologists, geologists, curators, policymakers, and technologists describe natural heritage differently. Through semantic mappings among their vocabularies, the ontology fosters mutual understanding and serves as a reference for defining requirements and evaluating results.

Fourth, it establishes a computable basis for reasoning. Beyond data storage, inference rules enable machines to generate new insights—for example, recommending conservation priorities or assessing climate-related risks.

Finally, it ensures sustainability and scalability. Its modular, standards-based design allows gradual extension as new discoveries, policies, and technologies emerge, linking it to the global natural heritage knowledge ecosystem. Thus, the E-DNH ontology functions as a semantic infrastructure that integrates the multilayered dimensions of natural heritage into a coherent knowledge space.

5.2. Design Principles

The E-DNH ontology is designed to overcome the technical limitations of existing digital specimen models by structurally representing the complex interrelations between the physical entity, cultural context, and digital actions of natural heritage. To achieve this, three primary design considerations were established.

5.2.1. Triple Module with Data, Metadata, and Paradata

The E-DNH ontology distinguishes information across three conceptual layers: data, metadata, and paradata. The data layer represents physical specimens or observational records; the metadata layer describes their cultural value, legal status, and management context; and the paradata layer encompasses the technical and interpretative processes involved in digital production. This tripartite design functions not only as a data structure but as a principle that represents both the lifecycle of information and the epistemic evolution of knowledge.

Traditional natural heritage information systems have tended to store measurements and observations on a single plane, where facts, interpretations, and contexts are mixed without distinction. Such flat structures make it difficult to evaluate data reliability and lead to the loss of contextual meaning when knowledge is reused. To address this issue, the E-DNH ontology stratifies knowledge according to the agent and purpose of creation: the data layer captures primary evidence observed through instruments and sensors; the metadata layer records the social and cultural meanings that transform a natural entity into a heritage object; and the paradata layer explicitly reveals the digital mediation process, clarifying that a digital outcome is not a perfect replica but an interpretative reconstruction produced within specific technological constraints.

This tri-layer structure ensures both the traceability and reproducibility of knowledge. The data layer alone cannot indicate who created the data or for what reason, and the metadata layer alone cannot explain the technical processes behind the resulting 3D model. The explicit documentation of the paradata layer implements the principle of propagation of uncertainty, allowing mathematical tracking of how sensor calibration or alignment errors affect the geometric and visual accuracy of the final digital model. Furthermore, by adopting the

provenance model of W3C PROV-O, the E-DNH framework enables reverse tracing from a digital outcome back to its raw data, ensuring scientific reproducibility when the same parameters are applied.

Table 8 illustrates how the paradata layer is operationalized within an actual 3D digitization workflow, showing the relationships among equipment calibration, acquisition conditions, and uncertainty propagation throughout the processing chain.

5.2.2. Ensuring Interoperability Among Multiple Standards

Natural heritage information is inherently multidisciplinary, with each domain having developed its own data standards and vocabularies. The E-DNH ontology respects these existing standards while constructing an integrated knowledge framework through semantic interlinking.

The Digital Specimen Module is based on

Darwin Core [

21], the de facto standard in biodiversity informatics, which provides rich vocabularies for describing collection history, taxonomic identification, and spatiotemporal context—widely adopted by natural history museums and research institutions worldwide. To complement this,

ABCD 3.0 offers detailed anatomical descriptions of specimen parts; Audubon Core defines metadata for multimedia resources; and

MorphoSource provides 3D morphological data models ensuring scientific completeness. The

Heritage Module adopts the event-oriented philosophy of

CIDOC CRM, the reference model for cultural heritage information. CIDOC CRM models heritage-related actions as temporal events, capturing not only static attributes but also dynamic processes of inscription, conservation, and utilization. The

LIDO schema supports administrative and technical metadata for museums and heritage institutions, facilitating data exchange and interoperability with aggregation platforms such as Europeana. The

Digital Module integrates

W3C PROV-O for provenance tracking and CRMdig for modeling the digitization workflow. PROV-O enables transparent tracing of digital asset lineage, while

CRMdig records measurement activities, technical parameters, and equipment specifications.

In the integration process, Darwin Core was used to describe specimens as biological entities, CIDOC CRM to represent them as heritage objects, and CRMdig with PROV-O to capture their digitization and provenance. By aligning corresponding properties among these models, E-DNH represents the transformation of specimens across collection, designation, digitization, and reuse phases. This cross-standard integration provides a transparent foundation for documenting the reliability and reproducibility of digital assets.

5.2.3. Semantic Reasoning and Knowledge Expandability

The E-DNH ontology incorporates an inference mechanism capable of deriving implicit knowledge from explicitly modeled information. This design moves beyond conventional data retrieval toward an active knowledge system that supports discovery and hypothesis generation.

First, taxonomic reasoning enables the identification of biodiversity patterns. By linking Taxon Identification and Location data, the system can automatically aggregate and visualize species distributions, endemic ratios, and ecological interactions within specific regions. When combined with Chronometric Age information, it becomes possible to trace temporal changes in biota, assess extinction risks, and analyze the impacts of climate change. Second, heritage-value reasoning facilitates the identification of conservation priorities through the network of heritage relationships. By analyzing the association between Heritage Aspect and Outstanding Universal Value, the system can evaluate which natural phenomena satisfy multiple World Heritage criteria and determine the effectiveness of existing legal protection frameworks. The network connecting Heritage Interact and Social Engagement further supports the analysis of how community participation influences conservation outcomes. Third, technical reasoning enhances the traceability and reliability of digital outcomes. By connecting Quality Assessment with Provenance Trace, the system can reverse-track the technical procedures behind a specific digital output and identify stages where uncertainty was introduced. The Comparative Validation module allows the cross-evaluation of different digitization methodologies, providing a basis for selecting optimal workflows.

These reasoning capabilities are enabled by the cross-module relationships and the semantic definitions of standardized vocabularies within the ontology. As new data are incorporated, the knowledge graph expands dynamically, generating new insights through the evolving relationships among existing entities.

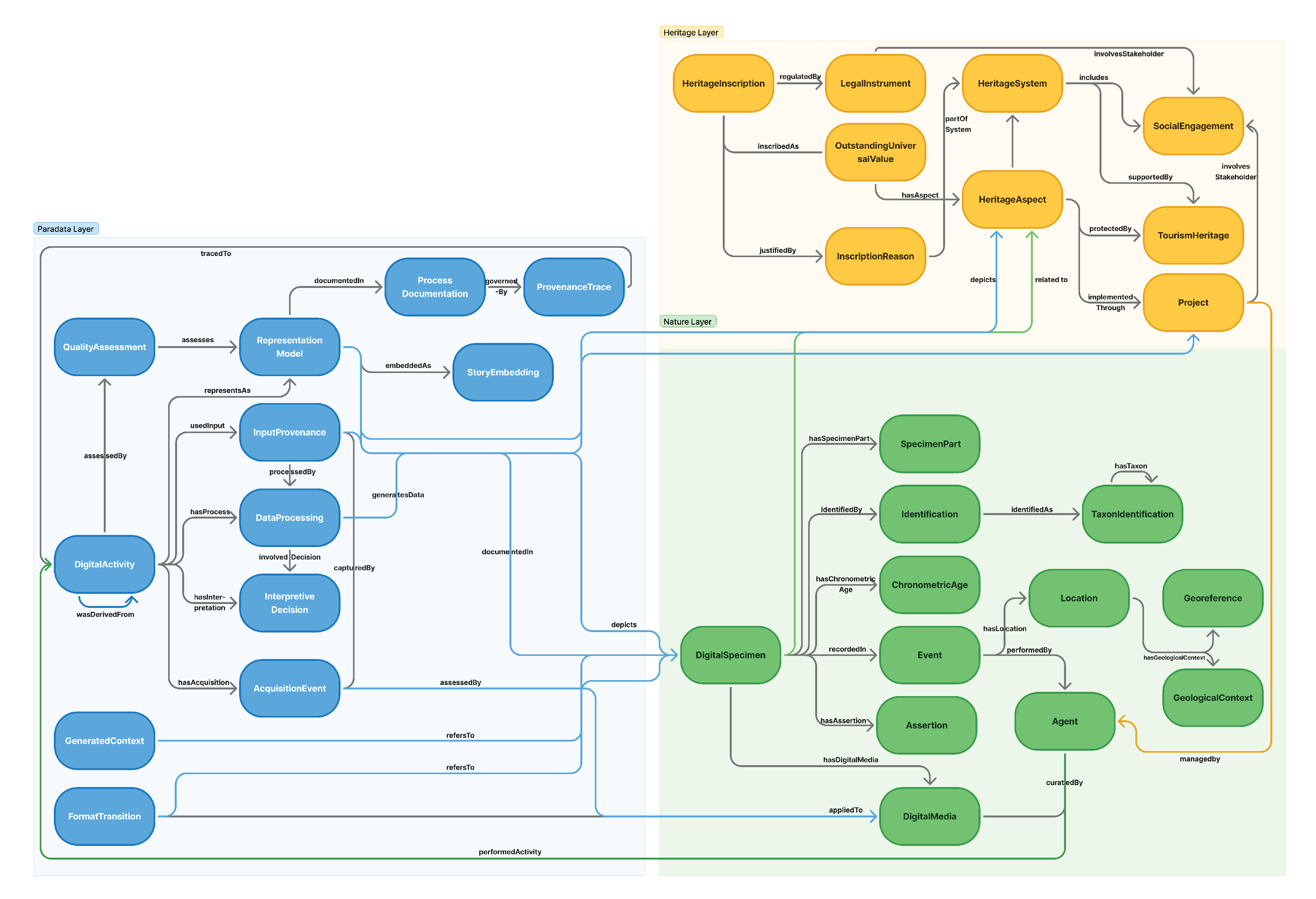

5.3. Modular Design Strategy

Building upon the design principles discussed in the previous section, the E-DNH ontology adopts a modular architecture inspired by the NeOn Methodology. This approach decomposes complex natural heritage knowledge into manageable yet semantically connected components, enabling coherent reasoning across different domains while maintaining conceptual clarity. The modular architecture follows three fundamental design logics: separation of concerns, reusability and scalability, and loose coupling with explicit interfaces.

First, separation of concerns allows experts from different disciplines to refine and validate the ontology independently. The Nature Module focuses on the biological and ecological dimensions of specimens, the Heritage Module captures their cultural and governance context, and the Digital Module represents the technical and interpretive processes involved in digitization. Each module encapsulates a self-contained semantic structure aligned with its disciplinary perspective. Second, reusability and scalability ensure that each module can be applied or extended in diverse projects. The Nature Module can serve natural history collection systems, the Heritage Module can be integrated into heritage information infrastructures encompassing both cultural and natural heritage, and the Digital Module can operate within digital preservation and visualization platforms. The modular design also supports the incremental addition of new classes and properties to meet emerging research and policy requirements. Third, loose coupling with explicit interfaces allows interoperability while minimizing dependency among modules. Core entities—such as DigitalSpecimen, HeritageAspect, and DigitalActivity—serve as semantic bridges linking data about biological specimens, heritage values, and digitization processes. These links enable cross-module reasoning and federated queries while preserving modular autonomy.

As visualized in

Figure 5, the three modules correspond directly to the tri-layered structure of data, metadata, and paradata defined in

Section 5.2.2. The

Nature Module models empirical data (e.g.,

Event,

Location), the

Heritage Module encodes interpretive and managerial metadata (e.g.,

HeritageProject,

LegalInstrument), and the

Digital Module captures process-level paradata (e.g.,

AcquisitionEvent,

DataProcessing). Together, they represent the complete intellectual lifecycle of natural heritage—from observation and valuation to digital reconstruction and validation—positioning E-DNH not merely as a data archive but as a semantic knowledge infrastructure that supports integrative reasoning, transparency, and long-term sustainability. The following Sections (5.4-5.6) provide detailed definitions of the classes and object properties for each module.

5.4. Nature Module (Nature and Digital Specimen)

The Nature Module provides a semantic framework for systematically describing the physical entities and scientific observations of natural heritage. It adopts Darwin Core as its core vocabulary—a standard developed through over thirty years of efforts in biodiversity informatics—while integrating complementary specifications such as ABCD 3.0 for precise anatomical descriptions of specimen parts, Audubon Core for multimedia metadata, and the MorphoSource model for 3D morphological data. Through this integration, the module enables seamless data exchange among natural history museums, research institutions, and biodiversity data aggregators, ensuring both the scientific completeness and interoperability of specimen information.

5.4.1. Core Class Definition

DigitalSpecimen.

A Digital Specimen represents the digital surrogate of a physical natural specimen, characterized by identifiers, specimen type, and holding institution. It extends the Occurrence concept of Darwin Core, establishing the digital twin of a permanently curated specimen within a museum collection.

Event.

The Event class records the spatiotemporal activities associated with the specimen—such as collection, observation, or excavation events—capturing the precise moment when the specimen was documented within a scientific context. These records serve as essential provenance information for assessing the specimen’s origin and reliability.

Location.

The Location class defines the geographical setting where the specimen was discovered or observed. In addition to coordinates, it incorporates hierarchical spatial data such as administrative divisions, place names, elevation, or depth, supporting both ecological distribution analysis and boundary delineation of heritage sites.

Identification.

The Identification class documents the taxonomic determination process and results of a specimen. It explicitly records the identifier, date, method, and confidence level, thereby allowing the historical traceability and re-evaluation of taxonomic decisions over time.

DigitalMedia.

The Digital Media class describes the visual or auditory representations of a specimen—such as photographs, videos, 3D models, and audio recordings—using the Audubon Core metadata structure. It includes attributes such as file format, resolution, authorship, and capture conditions, ensuring standardized management of multimedia assets.

Agent.

The Agent class represents individuals or organizations involved in specimen-related activities, including collectors, taxonomists, curators, and researchers. By documenting the roles and contributions of each agent, this class supports scientific accountability and scholarly citation across the specimen lifecycle.

5.4.2. Object Properties

Table 9 summarizes the principal o

bject properties defined for the Nature Module.

5.5. Heritage Module (Heritage Value)

The Heritage Module semantically models the processes through which natural heritage is recognized, protected, and managed as a shared cultural and historical asset of humanity. Building upon the event-centered design philosophy of CIDOC Conceptual Reference Model (CIDOC CRM)—which conceptualizes heritage not as a static entity but as a socially constructed phenomenon evolving over time—the module integrates the LIDO metadata schema to capture the dynamic processes of heritage valuation, inscription, conservation, and utilization. This approach reflects the dual nature of natural heritage as both a scientific subject and a culturally constituted asset shaped through social consensus and legal instruments. By doing so, the module establishes an interoperable framework that facilitates information exchange among heritage management institutions and supports data integration with international heritage platforms such as UNESCO World Heritage and national designation systems.

5.5.1. Core Class Definitions

OutstandingUniversalValue.

Outstanding Universal Value represents the core concept of UNESCO’s World Heritage inscription criteria, denoting the exceptional and global significance of a natural heritage site to all humanity. This class structures attributes that correspond to the inscription criteria, including geological processes, ecosystems, biodiversity, and aesthetic value.

HeritageInscription.

The Heritage Inscription class records the administrative and legal procedures through which natural heritage sites are officially designated for protection. It tracks the chronological stages of inscription across multi-layered protection systems, including World Heritage listing, national monument designation, and natural monument registration.

HeritageAspect.

The Heritage Aspect class decomposes the multidimensional values of natural heritage. It allows separate evaluation and management of diverse attributes—such as biological diversity, geological importance, ecological process, cultural landscape, and scientific research value—when a single site embodies multiple heritage dimensions simultaneously.

HeritageProject.

The Heritage Project class represents organized activities for the conservation, restoration, or sustainable use of heritage sites. It includes projects such as habitat restoration, invasive species removal programs, environmental monitoring systems, and visitor management improvements, enabling systematic tracking of heritage management practices.

LegalInstrument.

Dhe Legal Instrument class describes the legal, regulatory, and policy frameworks that govern heritage protection. It structures how international conventions, national laws, ordinances, and management guidelines are applied to natural heritage, while specifying the scope and enforceability of each instrument.

SocialEngagement.

The Social Engagement class models the participation of local communities, indigenous groups, and stakeholders in heritage management. It documents activities related to collaborative governance, integration of traditional knowledge, and community consultation, highlighting the social dimensions of heritage stewardship.

5.5.2. Object Properties

Table 10 summarizes the principal

object properties that define semantic relationships within the Heritage Module.

5.6. Digital Module (Digitalization Process)

The Digital Module structures all technical activities, decisions, and evaluations that occur during the three-dimensional digitization of natural heritage as paradata. It integrates the provenance-tracking framework of W3C PROV-O, which models the genealogical relationships of digital entities through the triad of Activity, Entity, and Agent, with CRMdig, an extension of CIDOC CRM specifically designed to model digitization processes. CRMdig precisely represents the Digitization Process (D2), Parameter Assignment (D13), and Digital Object (D1), thereby providing a conceptual foundation for translating the complexity metrics and quality indicators defined by the EU Eureka3D Quality Framework into an ontological structure. The module specializes in this framework for the context of natural heritage, formalizing technical components verified in real-world 3D digitization projects—such as robotic scanning, multi-sensor fusion, and AI-based texture reconstruction—into dedicated classes and properties. This paradata structure ensures both the trustworthiness and reproducibility of digital representations.

5.6.1. Core Class Definitions

InputProvenance.

The InputProvenance class traces the origins and generation context of raw data used in the digitization process. It structures all input factors affecting data quality, including scanner model, sensor configuration, environmental conditions, and specimen preparation state.

AcquisitionEvent.

The AcquisitionEvent class records the precise moment when digital data are captured from a physical specimen. It specifies technical parameters of data acquisition such as scan resolution, point-cloud density, number of angles, and duration of the scanning session.

DataProcessing.

The DataProcessing class documents the computational procedures through which raw data are transformed into usable 3D models. It records details of each processing step—point-cloud registration, mesh generation, noise reduction, and hole filling—along with algorithms, parameters, and software versions employed.

QualityAssessment.

The QualityAssessment class measures how faithfully the digital output reproduces the geometry, color, and texture of the original specimen. It performs quantitative evaluations based on the Eureka3D quality indicators, including geometric accuracy, color fidelity, and texture clarity.

UncertaintyAnnotation.

The UncertaintyAnnotation class explicitly records confidence limits that arise during digital reconstruction. It visually and semantically distinguishes reconstructed or AI-generated components—such as inferred surfaces, estimated colors, or synthetic textures—and quantifies the sources and degrees of uncertainty.

ProvenanceTrace.

The ProvenanceTrace class establishes a traceable network that enables backtracking from the final digital object to its raw data and all intermediate processing steps. It employs the PROV-O properties wasDerivedFrom and wasGeneratedBy to construct a complete genealogical chain of digital provenance.

5.6.2. Object Properties

Table 11 summarizes the principal

object properties defined for the Digital Module.

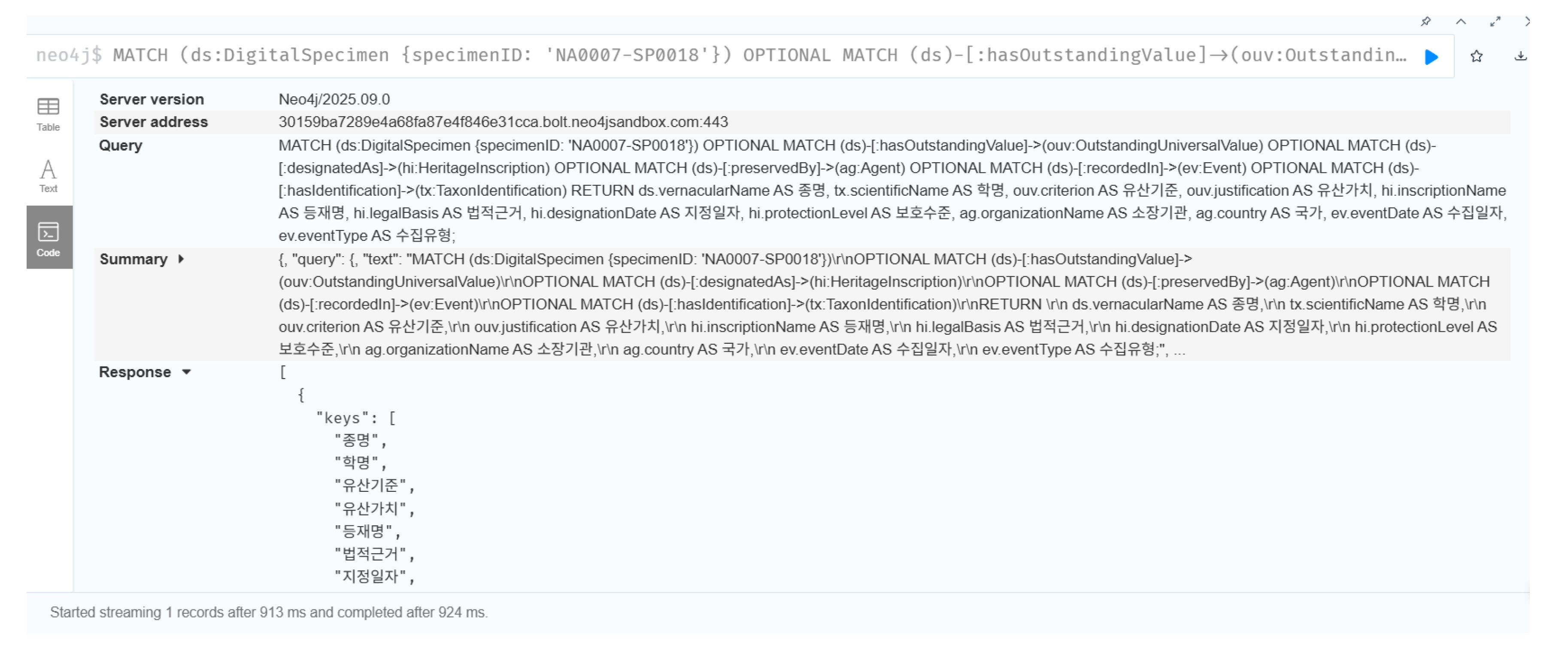

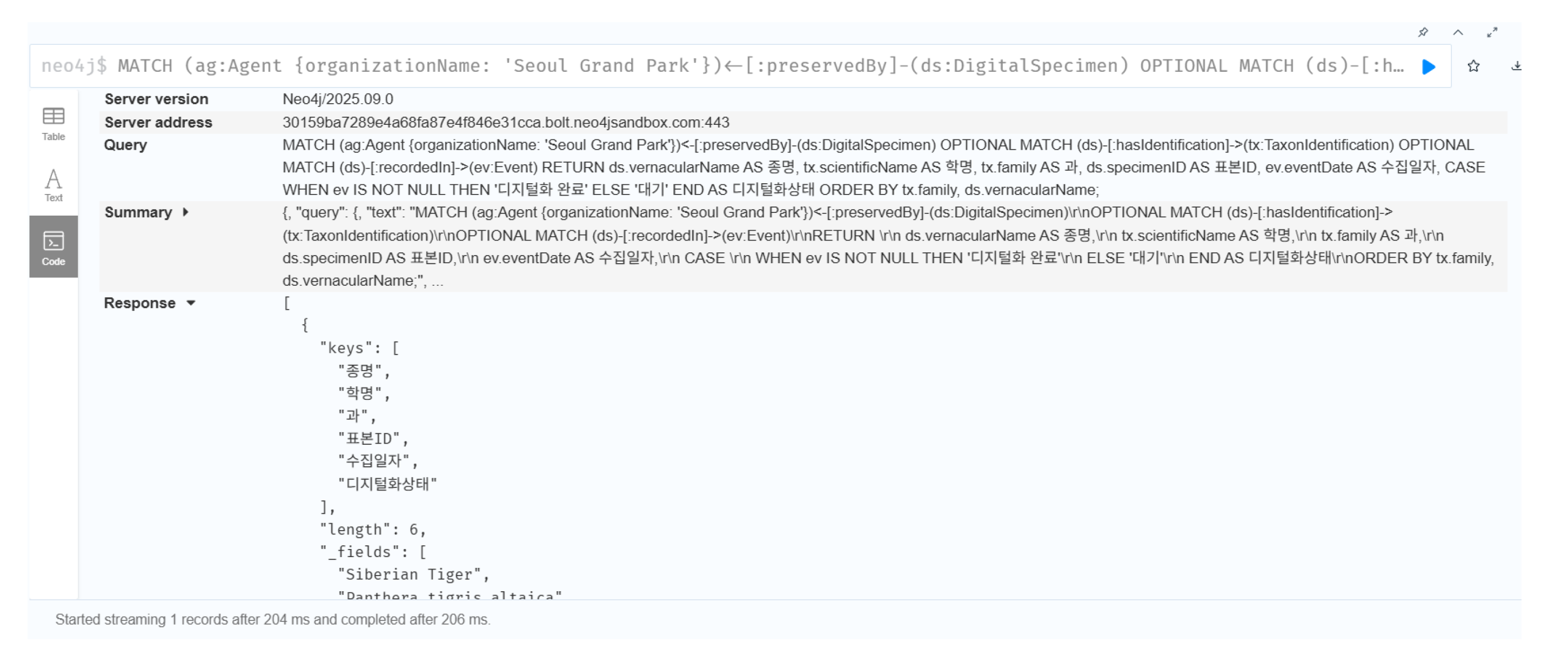

5.7. Ontology-Based Knowledge Graph Implementation

This section demonstrates the practical implementation of the E-DNH ontology using real natural heritage datasets, validating how the semantic relationships among the modules enable integrated knowledge reasoning. The case study focuses on 197 taxidermy specimens of endangered wildlife, representing approximately 140 biological species, preserved across the collections of Seoul Grand Park, Hannam University, and the National Heritage Administration of Korea. These datasets reveal the intersection points among the DigitalSpecimen class in the Nature Module, the OutstandingUniversalValue class in the Heritage Module, and the DigitalActivity class in the Digital Module, illustrating how the biological reality, cultural significance, and digital reconstruction of natural heritage are semantically integrated within a unified knowledge structure.

5.7.1. Interdependence among Cross-Modules

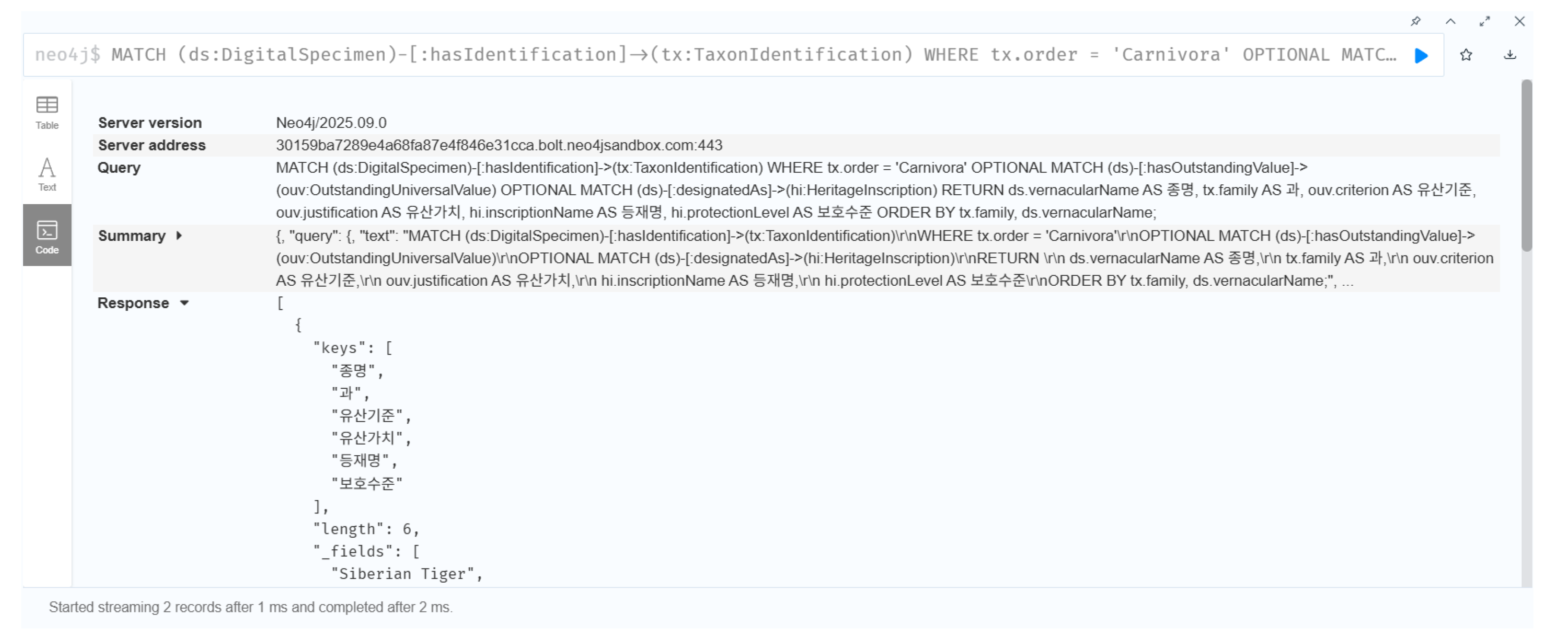

When defining inter-ontological relations, the focus is placed on the interdependent connections that natural heritage maintains with taxonomic classification, heritage value assessment, and digitization processes. For instance, species that qualify for designation as Natural Monuments in Korea are generally those listed as Vulnerable (VU) or higher on the IUCN Red List, or species that perform ecologically critical roles. Within the dataset analyzed in this study, 28 out of 31 species designated as Natural Monuments were categorized as Endangered (EN), Vulnerable (VU), or Near Threatened (NT). This correlation indicates that heritage inscription strongly aligns with biological rarity, ensuring that ontology-based recommendation systems can jointly consider both conservation priority and heritage designation when identifying candidates for protection or educational visualization.

The first cross-module dependency concerns the taxonomic hierarchy (TaxonIdentification), which serves as a primary determinant of heritage value characteristics. In the dataset, Carnivora species—such as otters, Siberian tigers, and wolves—are recognized for their ecological significance as apex predators, while Gruiformes species—such as cranes, storks, and white-naped cranes—possess cultural symbolism and scientific research value. Thus, taxonomic position directly shapes the type of HeritageAspect, linking ecological function and cultural meaning. Pattern analysis of the order attribute of DigitalSpecimen and the aspectType attribute of HeritageAspect within the Neo4j graph quantitatively reveals how heritage aspects are distributed across taxonomic groups.

The second dependency concerns protection status (nationalProtection, iucnStatus), which exerts a major influence on digitization priority and quality criteria. Among the specimens selected for 3D digitization, 68% were classified as either endangered wildlife or Natural Monuments. These specimens were scanned under higher spatial resolutions (0.1 mm vs. 0.5 mm) and stricter quality thresholds (RMS error < 0.3 mm; completeness > 95%) than ordinary specimens. A consistent trend was observed in which higher protection levels corresponded to higher resolution values in AcquisitionEvent and more stringent geometricAccuracy criteria in QualityAssessment. Hence, protection status functions as a key determinant of the technical parameters of the digitization process, forming a cross-module linkage in which attributes of the Heritage Module directly influence the configuration of activities in the Digital Module.

The third dependency involves the type of holding institution (Agent), which generated clear methodological and functional distinctions in digitization practices. In this dataset, Seoul Grand Park (a zoological institution) emphasized external realism for educational exhibition purposes, Hannam University (an academic research institution) focused on anatomical precision for morphological studies, and the National Heritage Administration (a governmental body) pursued photogrammetric documentation accompanied by detailed metadata for heritage recording. The institutional role primarily affects the purpose attribute of DigitalActivity and the outputFormat of TechnicalSpecification. Accordingly, this study defines the Agent.type property as a relational bridge connecting institutional characteristics in the Heritage Module with the process design of the Digital Module.

5.7.2. Internal Relationships and Hierarchy

When dealing with ontologies originating from different domains, hierarchical structuring serves as a fundamental mechanism for enabling integrated modeling of cross-domain concepts. This multi-layered relational modeling approach provides the semantic foundation for interoperability among heterogeneous ontologies, establishing the groundwork for subsequent knowledge inference and query optimization. Intra-module relationship modeling focuses on defining the internal relationships among detailed classes within each ontology module. By precisely describing the hierarchical dependencies and semantic connections between various entity levels, this modeling approach ensures accurate representation of complex object attributes, individual instances, and interlinked processes within the ontology.

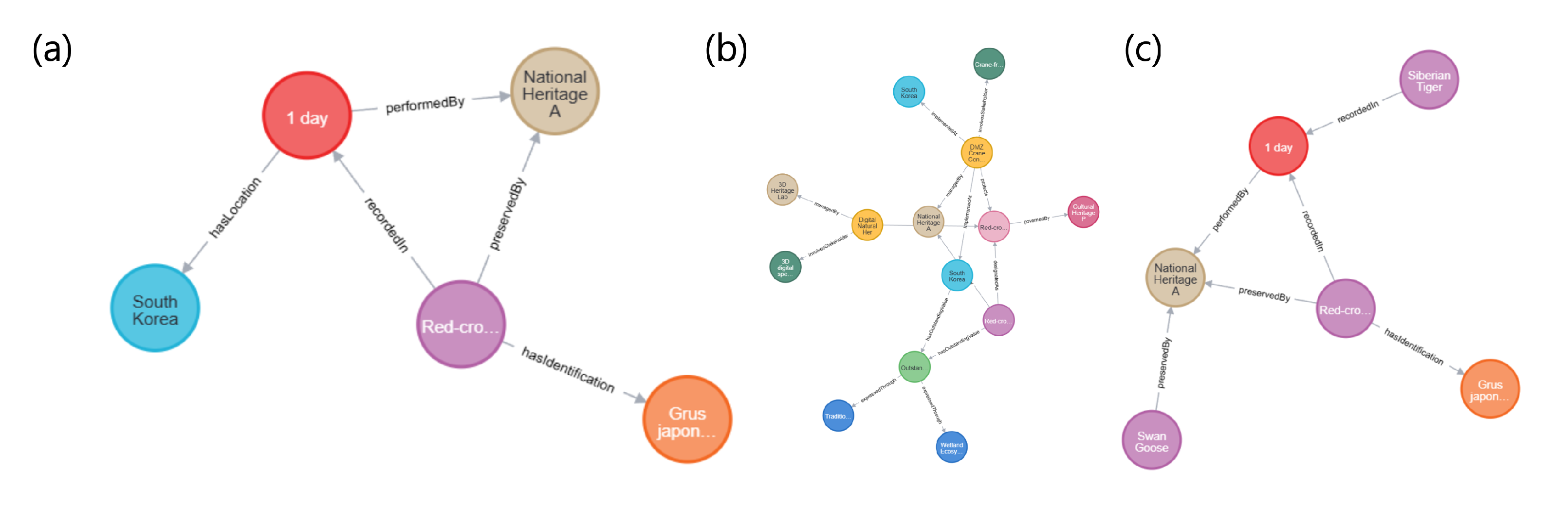

Figure 6 illustrate the exploratory flow of information within the internal relationships of each module — digital specimen, heritage value, and digital context — demonstrating how the E-DNH ontology supports systematic knowledge navigation and semantic reasoning across its modular architecture.

1) Internal Relationships within the Nature Module

Within the

Nature Module, the DigitalSpecimen functions as the central node. In this case study, the internal relationships were modeled around four crane (

Grus japonensis, NA0007) specimens (

Figure 6. (a)).

// Taxonomic identification of crane specimens

MATCH (ds:DigitalSpecimen {id: ’NA0007’})-[:identifiedAs]->(t:TaxonIdentifica

tion)

RETURN ds.vernacularName, t.order, t.family, t.genus

This query specifies that the specimen belongs to the taxonomic hierarchy Order Gruiformes → Family Gruidae → Genus Grus. The identifiedAs relationship reflects the Identification concept defined in Darwin Core and may include attributes such as identification date, identifier, and confidence level. In this dataset, the crane specimen was morphologically identified based on diagnostic characteristics—body length 140 cm, wingspan 240 cm, white plumage with black neck and head—with an identification confidence of 100%. Furthermore, the DigitalSpecimen maintains a preservation context through its relationship with the holding institution:

// Institutional distribution of crane specimens

MATCH (ds:DigitalSpecimen {scientificName: ’Grus japonensis’})-[:curatedBy]

->(ag:Agent)

RETURN ag.name AS Institution, COUNT(ds) AS SpecimenCount

The query result shows three specimens held by Seoul Grand Park and one by the National Heritage Administration, indicating that Seoul Grand Park serves as the primary repository for crane specimens. This distribution reflects the institution’s policy of operating a migratory bird conservation program and repurposing deceased individuals as educational materials through specimen preparation.

2) Internal Relationships within the Heritage Module

Within the

Heritage Module, the OutstandingUniversalValue (OUV) serves as the conceptual starting point. In this case study, the "Biodiversity Conservation Value" was represented as a single OutstandingUniversalValue node (OUV_001) (

Figure 6. (b)).

// Heritage inscription and legal foundation

MATCH (ouv:OutstandingUniversalValue {id: ’OUV_001’})-[:inscribedAs]->

(hi:HeritageInscription) -[:regulatedBy]->(li:LegalInstrument)

RETURN ouv.description, hi.designation, li.lawName, li.article

This query reveals that the Biodiversity Conservation Value is protected under a dual legal framework: designated both as a Natural Monument under Article 25 of the Cultural Heritage Protection Act and as a Class I Endangered Species under Article 7 of the Wildlife Protection and Management Act. The two laws govern distinct but complementary domains—cultural–historical significance under the National Heritage Administration and ecological–scientific significance under the Ministry of Environment. When a natural entity falls under both frameworks, it receives the highest level of institutional protection. The OutstandingUniversalValue is further subdivided into multiple HeritageAspects, as shown below:

// Multidimensional aspects of heritage value

MATCH (ouv:OutstandingUniversalValue {id: ’OUV_001’})-[:hasAspect]

->(ha:HeritageAspect)

RETURN ha.aspectType, ha.description ORDER BY ha.aspectType

For the crane (Grus japonensis), three primary aspects were identified:

Ecological significance: a top predator in wetland ecosystems and a key indicator of ecological health;

Cultural symbolism: a traditional emblem of longevity and good fortune, frequently depicted in Korean folklore and art;

Scientific research value: a focal species in migratory pathway analysis, climate-change monitoring, and conservation genetics.

Among these, the ecological significance aspect is directly connected to an ongoing conservation project:

// Linking heritage aspect with conservation project

MATCH (ha:HeritageAspect {id: ’HA_001’})-[:implementedThrough]

->(hp:HeritageProject)

RETURN ha.aspectType, hp.projectName, hp.objective, hp.budget

The “Crane Restoration and Habitat Conservation Project” (2015–present; annual budget ∼ ₩500 million) aims to stabilize the wintering populations in the Cheorwon area. This case exemplifies how the ecological aspect of heritage value can be translated into practical conservation action, bridging the conceptual layer of the ontology with real-world implementation.

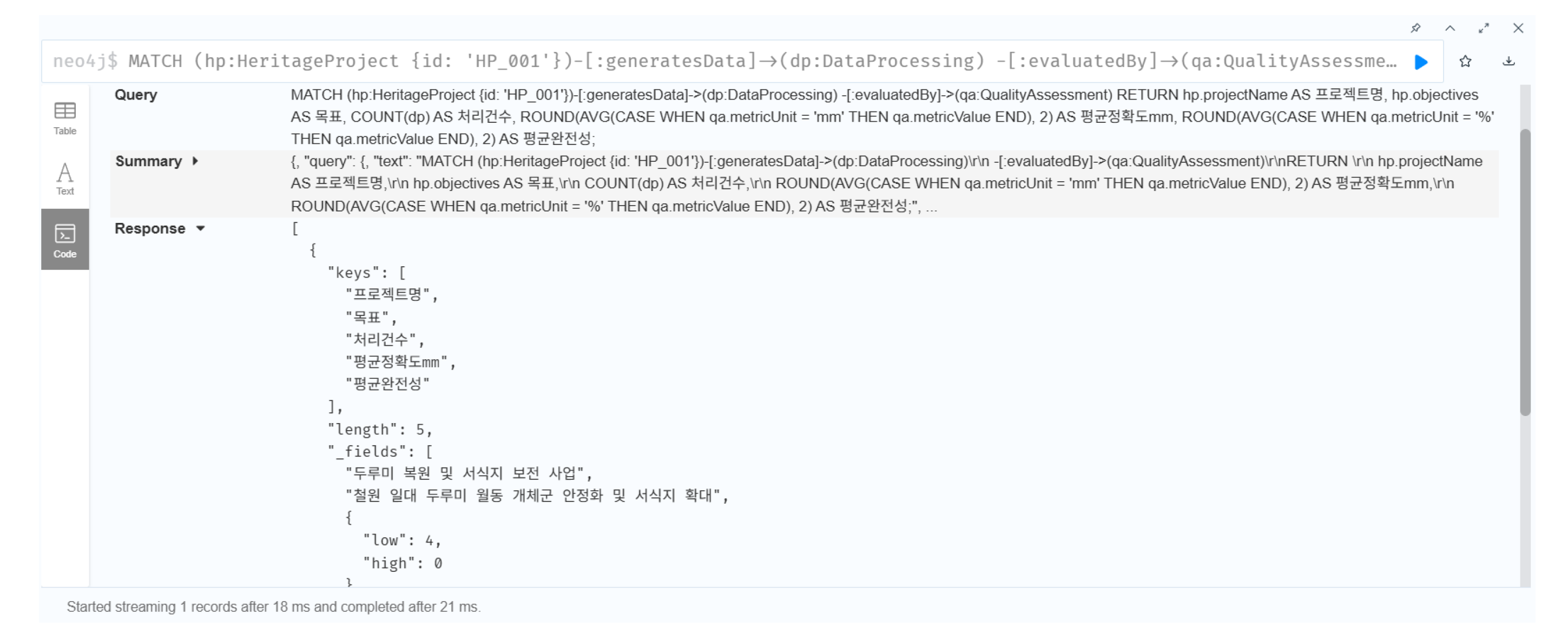

3) Internal Relationships within the Digital Module

Within the Digital Module, the core structure centers on tracing data lineage throughout the digitization workflow. The entire digitization process of the otter specimen (SP0018) was reconstructed in full detail (

Figure 6.(c)).

// Tracing data lineage of digitization workflow

MATCH path = (ae:AcquisitionEvent {id: ’AE_SP0018’})

-[:processedBy]->(dp:DataProcessing)

-[:assessedBy]->(qa:QualityAssessment)

-[:annotatesUncertainty]->(ua:UncertaintyAnnotation)

RETURN path

This query defines the following sequential process chain:

AcquisitionEvent (AE_SP0018): specimen preparation and 3D scanning conducted in 2022 using Artec Space Spider (resolution: 0.1 mm; ambient conditions: 20 °C, 45% RH);

DataProcessing (DP_001):Structure from Motion and Multi-View Stereo reconstruction using RealityCapture v1.3 (image overlap 85%, ICP alignment error < 0.5 mm);

QualityAssessment (QA_001): geometric accuracy RMS = 0.23 mm, color difference < 3.0, completeness = 97.8% (based on Eureka3D benchmark);

UncertaintyAnnotation (UA_001): AI-based texture restoration applied to damaged feather micro-structures, with a confidence level of 68%.

This lineage explicitly distinguishes which portions of the final 3D model originate from verified source data and which areas were algorithmically reconstructed through AI inference. The ProvenanceTrace node encapsulates the entire chain as a single meta-object, ensuring full traceability and reusability of digital assets across future workflows. By preserving the complete provenance path, the Digital Module guarantees scientific transparency, enabling reproducibility, quality validation, and responsible reuse of digital specimens.

5.7.3. Knowledge Graph Visualization and Interpretation

First, the centrality analysis indicates that the DigitalSpecimen node exhibits the highest degree of connectivity. For example, the crane specimen (NA0007) is directly or indirectly linked to twelve nodes, reflecting that the physical entity of natural heritage serves as the conceptual core from which all knowledge relationships originate. In contrast, the LegalInstrument and UncertaintyAnnotation nodes appear as terminal nodes, signifying that legal and uncertainty information provide contextual support rather than structural centrality within the knowledge network.

Figure 7.

presents the visualization of the above cases within the Neo4j graph database. The following structural characteristics can be observed in this graph.

Figure 7.

presents the visualization of the above cases within the Neo4j graph database. The following structural characteristics can be observed in this graph.

Second, cross-module relationships act as bridge edges that maintain the overall network integrity. When the relationships hasOutstandingValue (Nature → Heritage) and digitizedBy (Nature → Digital) are removed, the graph disintegrates into three independent components. This demonstrates that cross-module links are not mere references but structural dependencies essential for semantic connectivity within the E-DNH graph.

Third, path length analysis shows an average distance of 3.2 hops between any two nodes, indicating a small-world network structure that enables efficient semantic traversal even across complex queries. For instance, to retrieve “the digital model quality of species protected under a specific legal act”, the query path LegalInstrument →HeritageInscription→OutstandingUniversalValue→DigitalSpecimen→AcquisitionEvent→ Data Processing → QualityAssessment successfully produces the desired inference through a six-hop reasoning chain.

Fourth, the clustering coefficient of 0.68 reveals that connected nodes form tightly knit local clusters. This implies that related entities—such as all information linked to the crane (Grus japonensis)—form dense subgraphs, which facilitate context-aware information retrieval and enable the design of recommendation systems based on semantic proximity.

Overall, these graph metrics demonstrate that the E-DNH ontology functions not merely as a taxonomic framework but as an integrated knowledge network, capable of representing and reasoning over the multifaceted contexts of natural heritage. The following section presents an example of semantic storytelling, showcasing how this knowledge graph supports interpretive narratives grounded in real heritage data.

6. Semantic Collaborative Environment for Natural Heritage

6.1. System Architecture Overview

The proposed

Collaborative Extended Digital Natural Heritage Platform (C-EDNH) is designed as an intelligent data management framework that integrates the entire lifecycle of natural heritage data—from collection and semantic enrichment to utilization (

Figure 8). The architecture of the C-EDNH extends the Digital Knowledge Ecosystem concept introduced in the Basilica Iulia Project [1] into the natural heritage domain. It moves beyond conventional two-dimensional, metadata-centric information management systems to establish a collaborative, three-dimensional knowledge management environment in which multidisciplinary researchers can intuitively explore, annotate, and share spatial information. Through this approach, the platform combines the biological, heritage, and technical attributes of natural heritage specimens with three-dimensional digital twins, thereby realizing a collaborative framework that transcends mere visual representation and integrates semantic context. This architecture represents a paradigm shift from traditional linear and sequential workflows toward a dynamic and interconnected structure in which all components simultaneously consume and generate semantic data. Beyond functioning as a data repository, the system implements a knowledge-graph-based Semantic Knowledge Loop, ensuring the

Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability, and

Reusability (FAIR) of natural heritage data throughout its lifecycle. The overall architecture of the E-DNH is composed of three interlinked layers, each performing distinct yet complementary functions within a unified semantic framework.

Layer I – Data Acquisition Layer:

This layer encompasses the measurement-based digitization workflow, referred to as the Higher Reality 3D Digitalize(HR3D). It converts physical specimens into digital representations while comprehensively documenting every processing step. Using an integrated workflow that combines RealityCapture-based photogrammetry and robotic scanning systems, the platform standardizes the processes of high-precision measurement, registration, mesh generation, texture correction, and AI-assisted restoration. All outputs are recorded in standardized data formats and managed through persistent identifiers (NSId/DOI) to ensure long-term traceability and interoperability.

Layer II – Data Integration and Management Layer:

This layer integrates and normalizes the acquired 3D and textual data within an ontology-based framework. Implemented on a Neo4j graph database, it semantically links the biological, heritage, and technical attributes of natural heritage specimens. Following CIDOC CRM, CRMdig, and Darwin Core standards, it defines the relationships among data, metadata, and paradata in a triple-layer structure. Through E-DNH Tools, researchers can collaboratively annotate and validate the heritage significance, legal protection status, and digitization quality of digital specimens. At this stage, digital representations are transformed into semantically enriched knowledge structures, enabling cross-domain reasoning and validation.

Layer III – Data Collaboration and Application Layer:

TThe uppermost layer provides advanced services for data utilization and international interoperability. It integrates AI-driven authoring tools, an OpenSearch-based semantic search engine, blockchain-based integrity verification, and a multi-user collaborative interface. A Handle-based NSId auto-assignment system ensures interoperability with global identifier infrastructures such as DiSSCo and GBIF, while AWS IAM and CloudFront services enable cloud-based authentication and access control. This layer operationalizes collaborative research and data governance within a globally networked ecosystem of natural heritage knowledge.

At the core of the architecture lies a Neo4j-based graph database that functions as a semantic hub connecting the biological, heritage, and technical attributes of natural heritage specimens. Each digital specimen is modeled as an interconnected graph node linking its taxonomy, heritage value, and digitization history, thereby enabling complex queries and reasoning across the knowledge base. Consequently, the digital twin extends beyond geometric representation to incorporate semantic, temporal, and evidential dimensions, maintaining an explicit link to its physical counterpart. For instance, the system can answer queries such as “Which endangered species discovered in a given region have high-resolution 3D models available?” Surrounding this semantic core, an interoperability portal facilitates collaboration and dissemination through virtual exhibitions, OAI-PMH–compliant metadata publication, and integration with infrastructures such as DiSSCo and GBIF. The layered architecture supports bidirectional data flow between processing stages, allowing semantic outputs to inform earlier stages of the workflow. For example, annotations or heritage assessments created in Layer III are immediately reflected in the knowledge graph (Layer II), guiding scanning priorities and quality control in Layer I. Finally, the Provenance Tracking mechanism—currently under development—automatically records each step of the digitization process, from photogrammetry and robotic scanning to Gaussian Splatting and AI inpainting, including parameters and quality metrics. This ensures reproducibility, transparency, and scientific accountability throughout the entire workflow.

6.2. Core Technological Components

This section outlines the core technological components of the E-DNH platform in a stepwise manner. Each component corresponds to the hierarchical architecture described in

Section 6.1, collectively forming an integrated framework that supports the three essential processes of the natural heritage domain—3D data processing, semantic knowledge structuring, and interoperability with international identifier infrastructures. The system harmonizes these elements into a unified technological ecosystem, ensuring seamless transitions between data acquisition, semantic enrichment, and collaborative utilization within a single, coherent workflow.

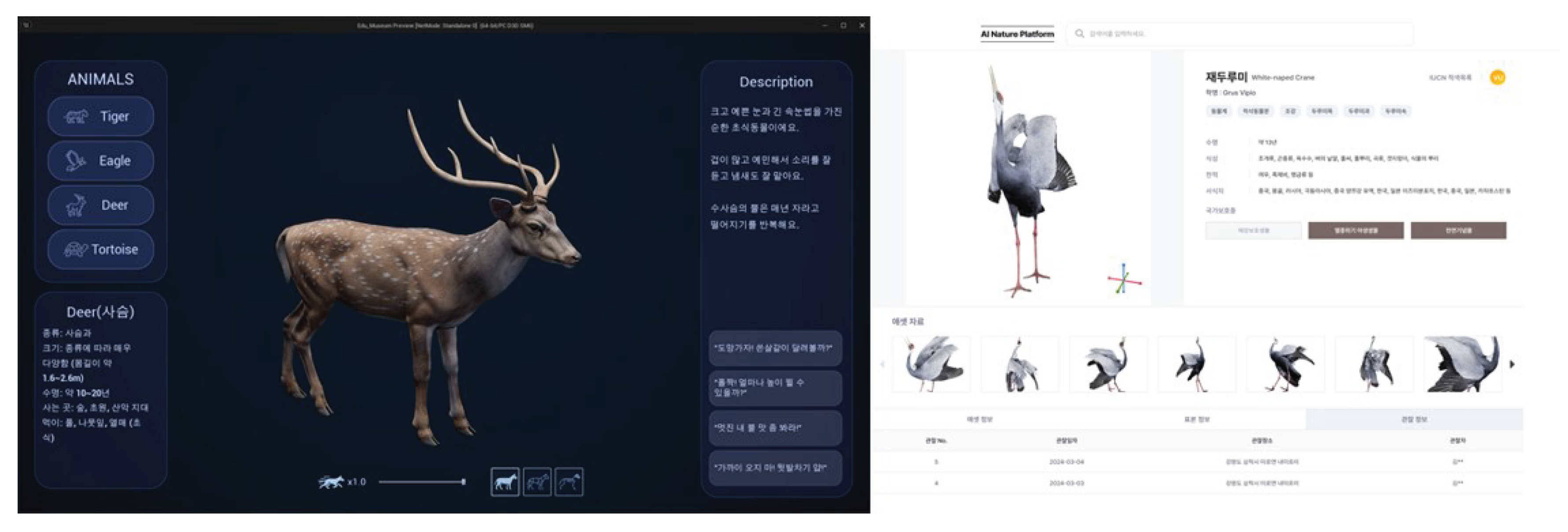

6.2.1. HR3D (Higher Reality 3D Digitalize)

One of the core technological achievements of this study is the development of the

HR3D (Higher Reality 3D Digitalize) system, as illustrated in

Figure 11, which is designed to reproduce the fine textures and morphological features of natural heritage specimens with ultra-high precision. The proposed framework integrates Gaussian Splatting–based 3D reconstruction with AI inpainting powered by Latent Diffusion Models (LDM), overcoming the inherent limitations of traditional mesh-based approaches while substantially improving the efficiency of large-scale dataset management. The HR3D system establishes an integrated data-processing pipeline optimized for the specific characteristics of natural heritage specimens and consists of the following modular components: