Submitted:

03 November 2025

Posted:

04 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

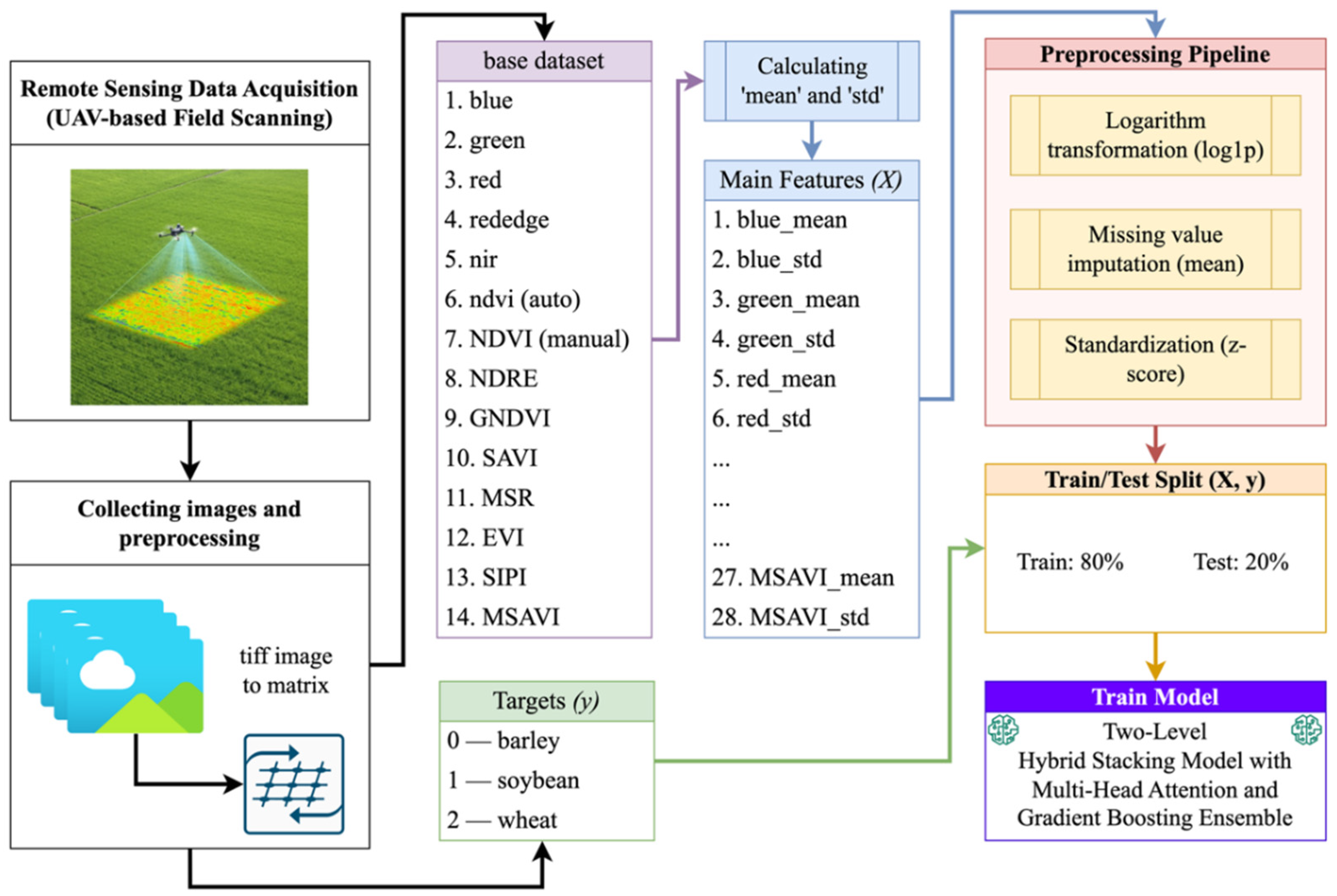

- An expanded feature space, including spectral channels and eight key vegetation indices (NDVI, NDRE, GNDVI, SAVI, MSR, EVI, SIPI, MSAVI) with their statistical characteristics (mean, std), generating 28 features per patch;

- An Out-Of-Fold meta-learning mechanism (OOF) that prevents data leakage and increases classifier robustness;

- An ExtraTreesClassifier meta-layer that optimally aggregates probabilistic predictions from base models, reducing the risk of overfitting and enhancing the system's generalization ability.

2. Related Work

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Dataset

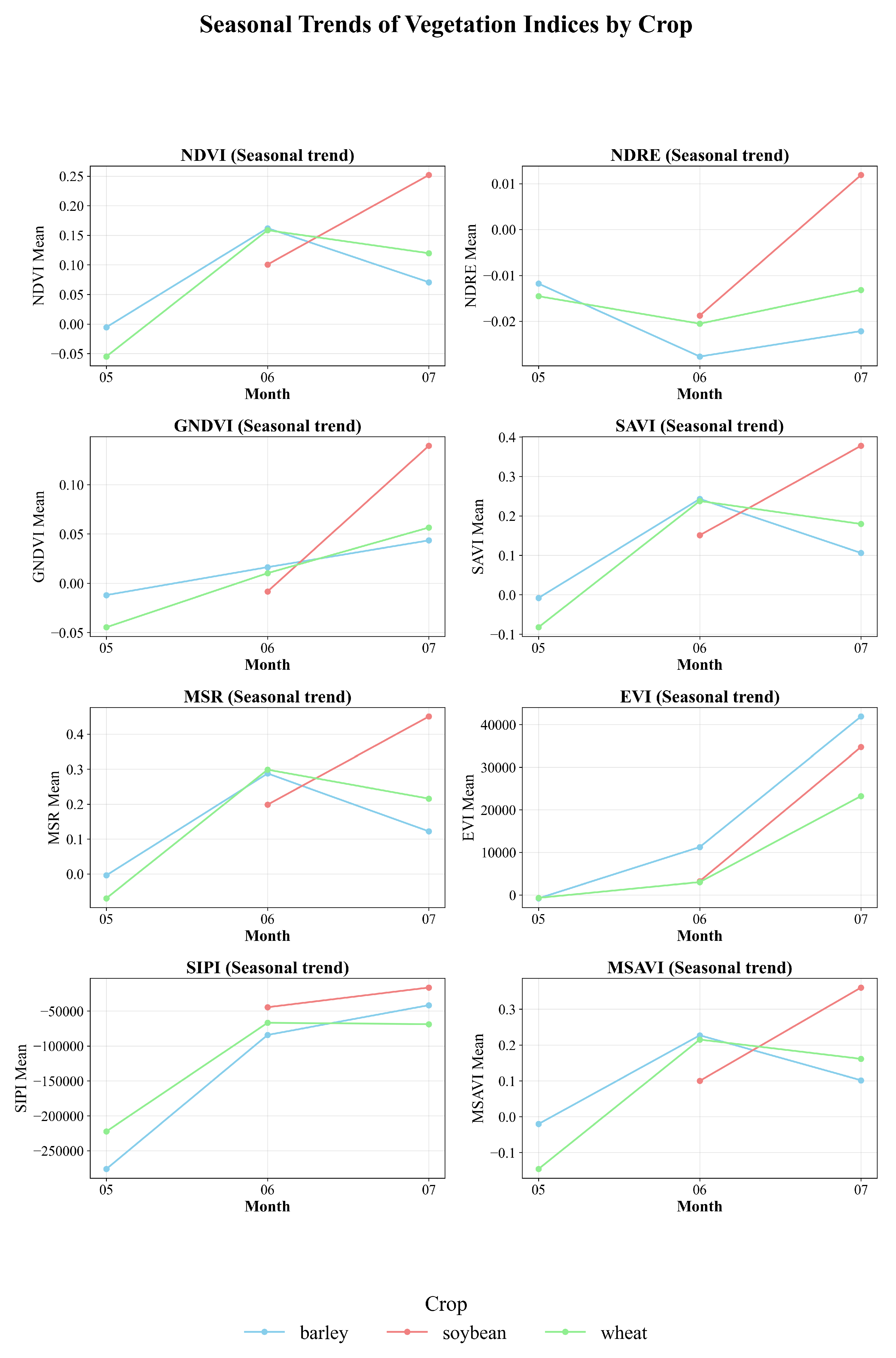

3.2. Statistical Analysis of Spectral Channels and Vegetation Indices

3.3. Post-Processing of Features

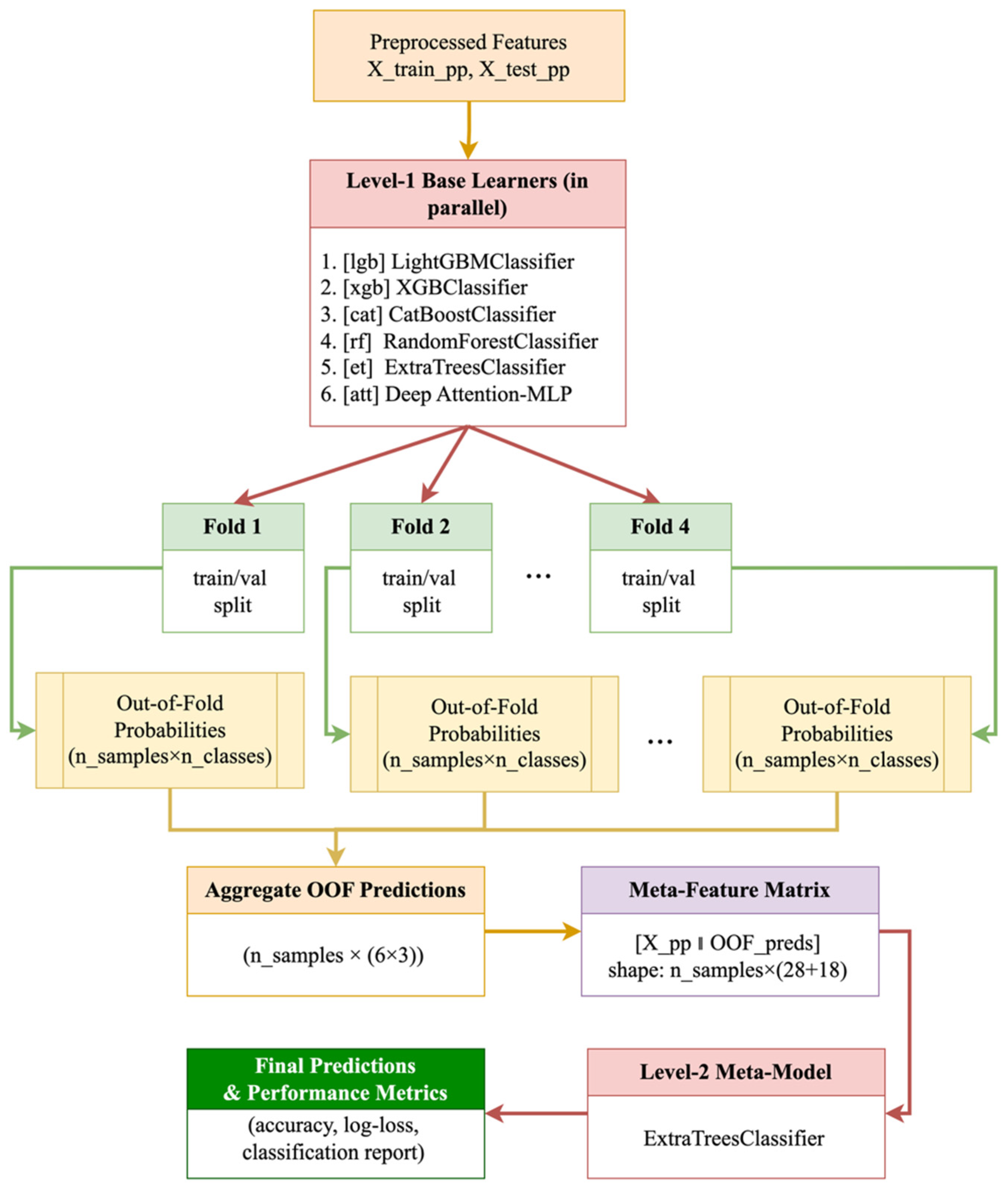

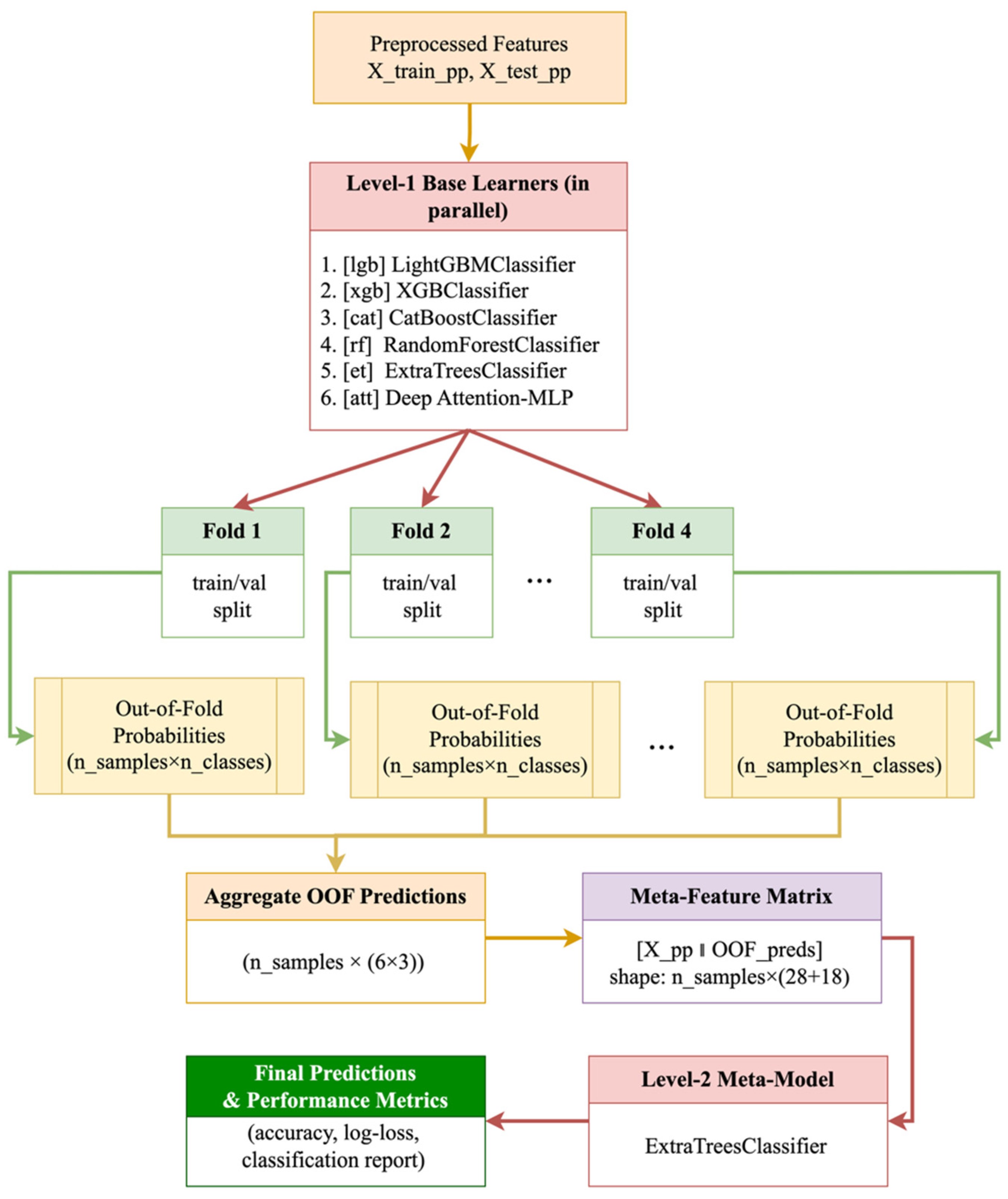

3.4. Building a Two-Tier Stacking Model

- LightGBMClassifier (lgb)

- XGBClassifier (xgb)

- CatBoostClassifier (cat)

- RandomForestClassifier (rf)

- ExtraTreesClassifier (et)

- Deep Attention-MLP (att)

- Avoiding data leakage through an out-of-band strategy: the probabilities of the base models for the meta-level are formed exclusively on validation folds.

- Integrating diverse data representations: gradient boosting reveals strong nonlinear dependencies, random forests and ExtraTrees stabilize predictions through averaging, and Attention-MLP takes into account complex correlations within vegetation indices.

4. Results

4.1. Analysis of Seasonal Dynamics of Vegetation Indices

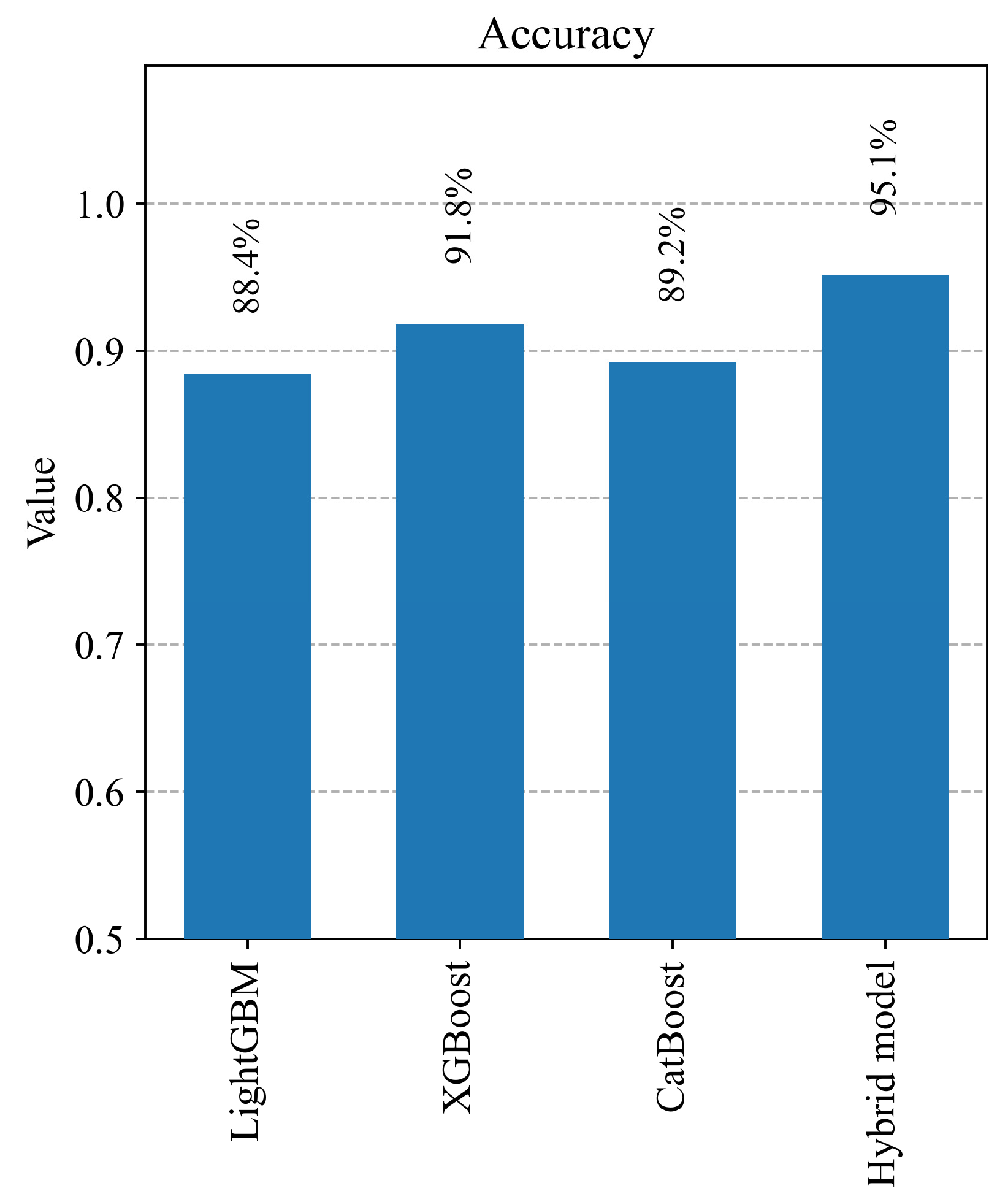

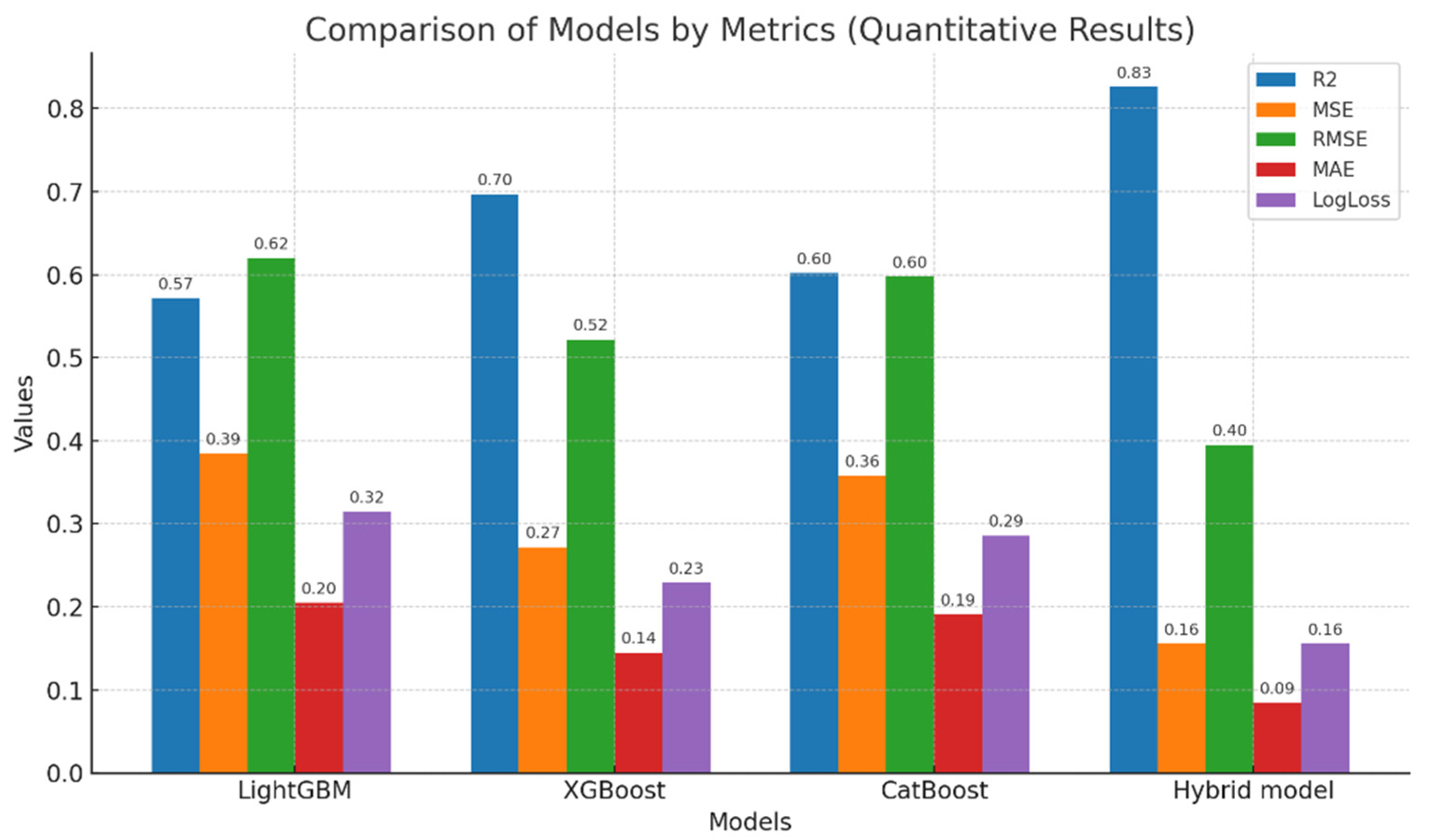

4.2. Evaluation of Model Results

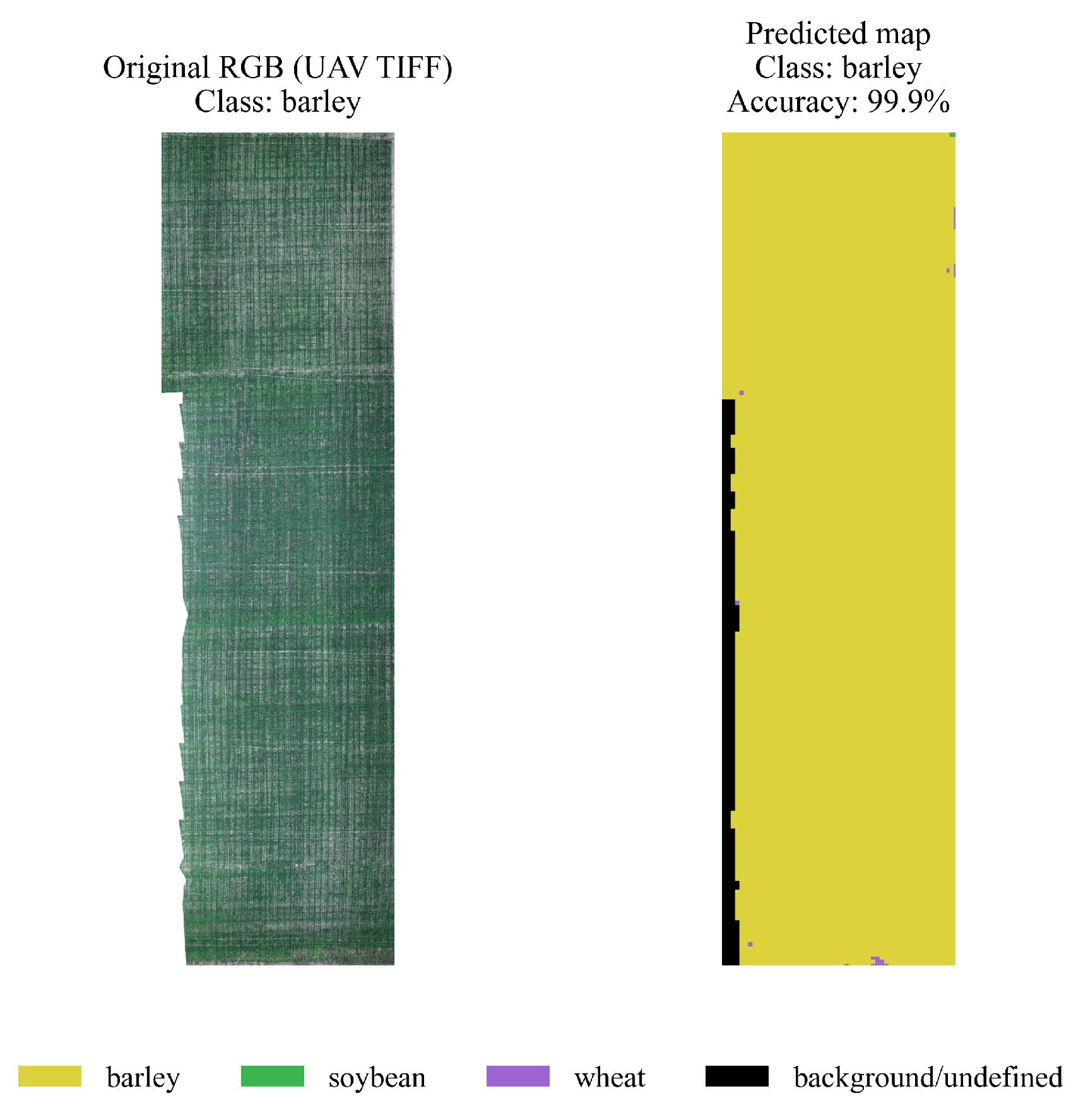

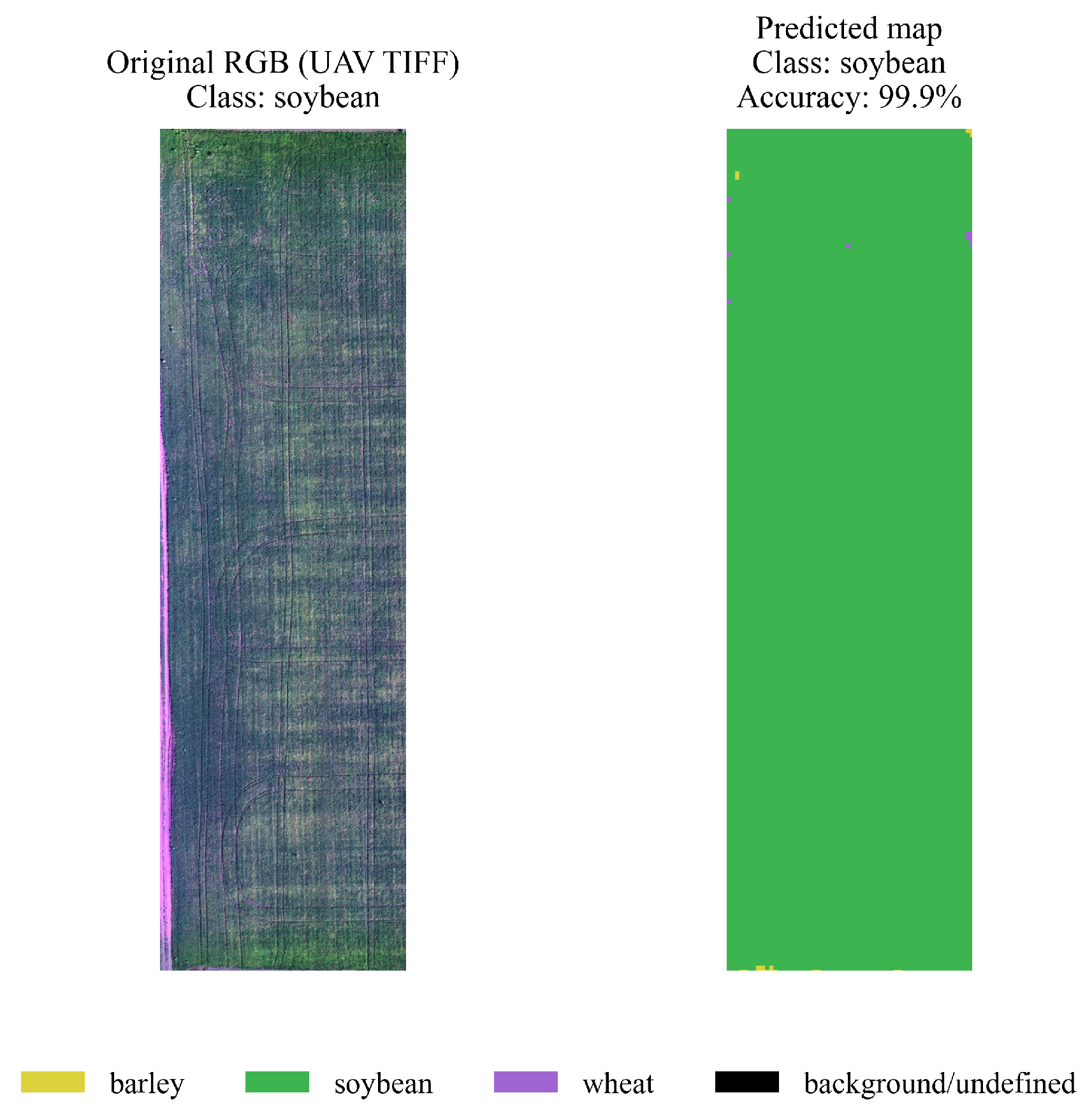

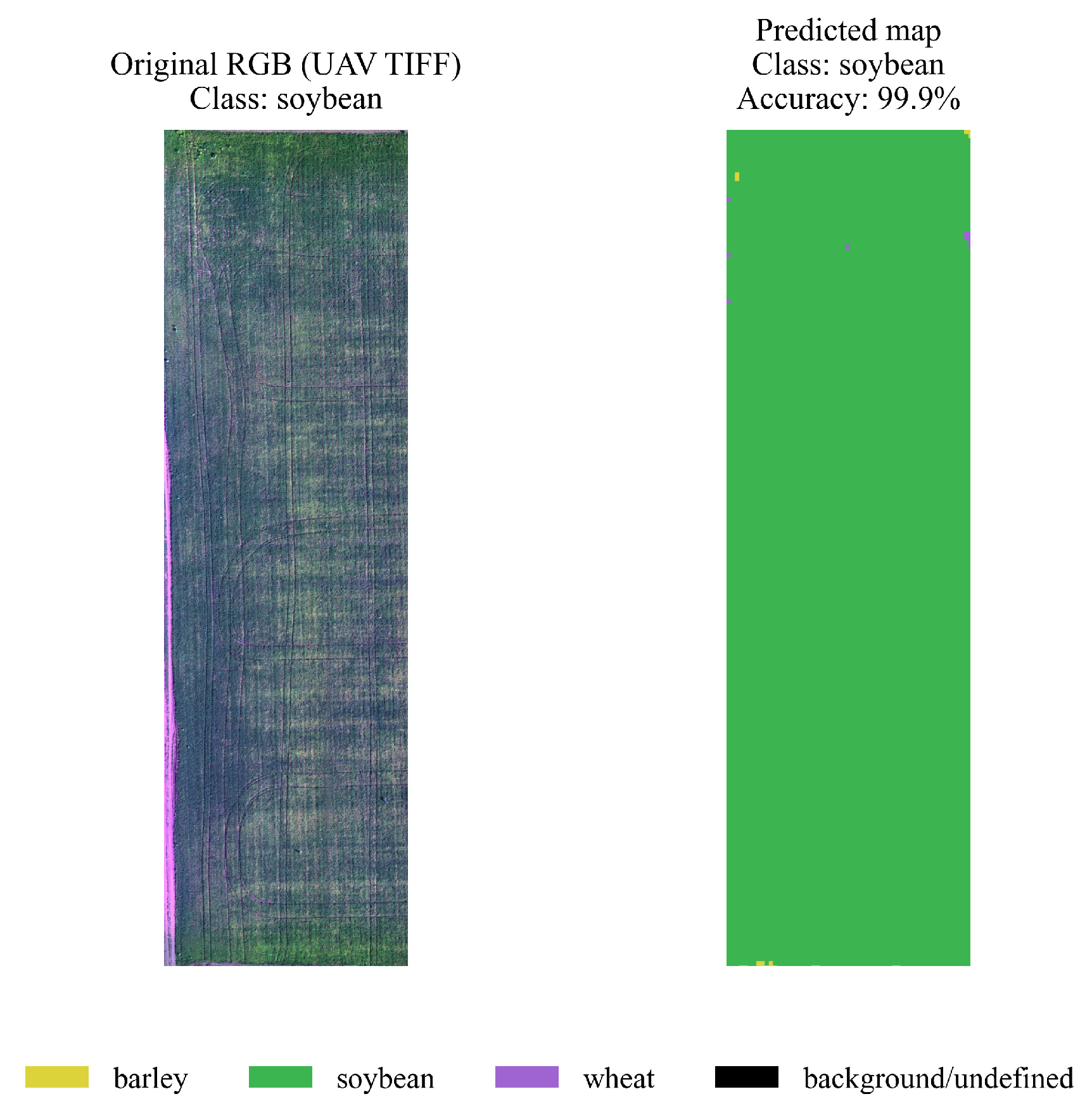

4.3. Spatial Segmentation and Visualization

- yellow — barley,

- green — soybeans,

- purple — wheat,

- black — background/undefined areas.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| NDVI | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index |

| SAVI | Soil Adjusted Vegetation Index |

| MSAVI | Modified Soil Adjusted Vegetation Index |

| EVI | Enhanced Vegetation Index |

| MSR | Modified Simple Ratio |

| GNDVI | Green Normalized Difference Vegetation Index |

| NDRE | Normalized Difference Red Edge Index |

| NIR | Near Infrared |

| MLP | Multilayer Perceptron |

| OOF | Out-Of-Fold (cross-validation prediction mechanism) |

References

- Shu, M.; Fei, S.; Zhang, B.; Yang, X.; Guo, Y.; Li, B.; Ma, Y. Application of UAV Multisensor Data and Ensemble Approach for High-Throughput Estimation of Maize Phenotyping Traits. Plant Phenomics 2022, 2022, 9802585. [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Hong, Y.; Li, J. Integrating UAV-Based Remote Sensing and Machine Learning to Monitor Rice Growth in Large-Scale Fields. Field Crop 2025, 8.

- Pádua, L.; Marques, P.; Martins, L.; Sousa, A.; Peres, E.; Sousa, J.J. Monitoring of Chestnut Trees Using Machine Learning Techniques Applied to UAV-Based Multispectral Data. Remote Sens. 2020, 12(18), 3032. [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Ding, J.; Li, J.; Han, L.; Cui, K.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Z. Advanced Dynamic Monitoring and Precision Analysis of Soil Salinity in Cotton Fields Using CNN-Attention and UAV Multispectral Imaging Integration. Land Degrad. Dev. 2025, 36(4), 5578. [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Zhang, W.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, H. Crop Classification Combining Object-Oriented Method and Random Forest Model Using Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) Multispectral Image. Agriculture 2024, 14(4), 548. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Fu, B.; Sun, X.; Yao, H.; Zhang, S.; Wu, Y.; Deng, T. Effects of Multi-Growth-Periods UAV Images on Classifying Karst Wetland Vegetation Communities Using Object-Based Optimization Stacking Algorithm. Remote Sens. 2023, 15(16), 4003. [CrossRef]

- Miller, T.; Mikiciuk, G.; Durlik, I.; Mikiciuk, M.; Łobodzińska, A.; Śnieg, M. The IoT and AI in Agriculture: The Time Is Now—A Systematic Review of Smart Sensing Technologies. Sensors 2025, 25(12), 3583. [CrossRef]

- Chang, B.; Li, F.; Hu, Y.; Yin, H.; Feng, Z.; Zhao, L. Application of UAV Remote Sensing for Vegetation Identification: A Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1452053. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, G.; Qi, Z. Integration of Remote Sensing and Machine Learning for Precision Agriculture: A Comprehensive Perspective on Applications. Agronomy 2024, 14(9), 1975. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhou, X.; Cheng, Q.; Fei, S.; Chen, Z. A Machine-Learning Model Based on the Fusion of Spectral and Textural Features from UAV Multi-Sensors to Analyse the Total Nitrogen Content in Winter Wheat. Remote Sens. 2023, 15(8), 2152. [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Hu, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Qiao, Y.; Zhang, K.; Guo, T.; Chen, J. Estimation of Potato Chlorophyll Content from UAV Multispectral Images with Stacking Ensemble Algorithm. Agronomy 2022, 12(10), 2318. [CrossRef]

- Dimyati, M.; Supriatna, S.; Nagasawa, R.; Pamungkas, F.D.; Pramayuda, R. A Comparison of Several UAV-Based Multispectral Imageries in Monitoring Rice Paddy (A Case Study in Paddy Fields in Tottori Prefecture, Japan). ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2023, 12(2), 36. [CrossRef]

- de Santana Correia, A.; Colombini, E.L. Attention, Please! A Survey of Neural Attention Models in Deep Learning. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2022, 55(8), 6037–6124. [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Li, H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y. OBViT: A High-Resolution Remote Sensing Crop Classification Model Combining OBIA and Vision Transformer. In Proc. 2023 11th Int. Conf. Agro-Geoinformatics; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Li, L.; Fei, S.; Yang, M.; Tao, Z.; Meng, Y.; Xiao, Y. Wheat Yield Prediction Using Machine Learning Method Based on UAV Remote Sensing Data. Drones 2024, 8(7), 284. [CrossRef]

- Acosta, M.; Visconti, F.; Quiñones, A.; Blasco, J.; de Paz, J.M. Estimation of Macro and Micronutrients in Persimmon (Diospyros kaki L.) cv. ‘Rojo Brillante’ Leaves through VIS-NIR Reflectance Spectroscopy. Agronomy 2023, 13(4), 1105. [CrossRef]

- Zhai, W.; Li, C.; Cheng, Q.; Ding, F.; Chen, Z. Exploring Multisource Feature Fusion and Stacking Ensemble Learning for Accurate Estimation of Maize Chlorophyll Content Using Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Remote Sensing. Remote Sens. 2023, 15(13), 3454. [CrossRef]

- Qiao, L.; Tang, W.; Gao, D.; Zhao, R.; An, L.; Li, M.; Song, D. UAV-Based Chlorophyll Content Estimation by Evaluating Vegetation Index Responses under Different Crop Coverages. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 196, 106775. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Lu, B.; Shang, J.; Wang, X.; Hou, Z.; Jin, S.; Zeng, Z. Ensemble Learning for Oat Yield Prediction Using Multi-Growth Stage UAV Images. Remote Sens. 2024, 16(23), 4575. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Xu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, Z.; Ullah, I.; Zhang, Z.; Miao, M. A Stacking Ensemble Learning Model Combining a Crop Simulation Model with Machine Learning to Improve the Dry Matter Yield Estimation of Greenhouse Pakchoi. Agronomy 2024, 14(8), 1789. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen Van, L.; Lee, G. Optimizing Stacked Ensemble Machine Learning Models for Accurate Wildfire Severity Mapping. Remote Sens. 2025, 17(5), 854. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Lu, C.; Yang, M.; Xia, Y.; Huang, D.; Lv, J. Research on Crop Classification Using U-Net Integrated with Multimodal Remote Sensing Temporal Features. Sensors 2025, 25(16), 5005. [CrossRef]

- Qaadan, S.; Alshare, A.; Ahmed, A.; Altartouri, H. Stacked Ensembles Powering Smart Farming for Imbalanced Sugarcane Disease Detection. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15(5), 2788. [CrossRef]

- Maulit, A.; Nugumanova, A.; Apayev, K.; Baiburin, Y.; Sutula, M. A Multispectral UAV Imagery Dataset of Wheat, Soybean and Barley Crops in East Kazakhstan. Data 2023, 8(5), 88. [CrossRef]

| Indicator | Barley | Soybean | Wheat |

| Blue, mean | 30294.74 | 31281.24 | 34236.00 |

| Blue, std | 5439.69 | 5634.40 | 4866.85 |

| Green, mean | 30626.37 | 31606.39 | 34063.71 |

| Green, std | 5785.33 | 6090.98 | 5120.80 |

| Red, mean | 27087.16 | 26084.46 | 29860.62 |

| Red, std | 6045.75 | 6157.13 | 5232.79 |

| RedEdge, mean | 33069.99 | 35576.38 | 36134.86 |

| RedEdge, std | 5402.41 | 5635.47 | 4580.95 |

| NIR, mean | 31737.90 | 35456.46 | 35132.80 |

| NIR, std | 5551.30 | 5691.14 | 4839.71 |

| NDVI, mean | 0.0910 | 0.1762 | 0.1003 |

| NDVI, std | 0.1079 | 0.1228 | 0.0948 |

| Indicator | Barley | Soybean | Wheat |

| Blue, mean (SD) | 6348.63 | 8735.04 | 10217.45 |

| Blue, std (SD) | 1700.65 | 2043.66 | 2235.90 |

| Green, mean (SD) | 5544.67 | 8419.40 | 10020.82 |

| Green, std (SD) | 1591.61 | 1801.59 | 2196.95 |

| Red, mean (SD) | 6860.20 | 10499.54 | 12214.14 |

| Red, std (SD) | 1953.69 | 2462.09 | 2602.48 |

| RedEdge, mean (SD) | 4630.23 | 6784.15 | 9465.18 |

| RedEdge, std (SD) | 1606.21 | 1942.92 | 2120.32 |

| NIR, mean (SD) | 4807.80 | 7226.45 | 9710.12 |

| NIR, std (SD) | 1661.03 | 1962.63 | 2152.67 |

| NDVI, mean (SD) | 0.1111 | 0.1668 | 0.1632 |

| NDVI, std (SD) | 0.0475 | 0.0506 | 0.0552 |

| Index | Barley | Soybean | Wheat |

| NDVI, mean | 0.0910 | 0.1762 | 0.1003 |

| NDVI, std | 0.1079 | 0.1228 | 0.0948 |

| NDRE, mean | -0.0222 | -0.0034 | -0.0164 |

| NDRE, std | 0.0224 | 0.0223 | 0.0214 |

| GNDVI, mean | 0.0215 | 0.0655 | 0.0177 |

| GNDVI, std | 0.0700 | 0.0806 | 0.0640 |

| SAVI, mean | 0.1364 | 0.2644 | 0.1504 |

| SAVI, std | 0.1618 | 0.1843 | 0.1423 |

| MSR, mean | 0.1612 | 0.3244 | 0.1918 |

| MSR, std | 0.1822 | 0.2186 | 0.1637 |

| EVI, mean | 21243.96 | 18984.23 | 10364.94 |

| EVI, std | 2357625.00 | 1447696.00 | 1185393.00 |

| SIPI, mean | -105925.40 | -30491.88 | -98746.84 |

| SIPI, std | 8724567.00 | 2293828.00 | 6478547.00 |

| MSAVI, mean | 0.1259 | 0.2301 | 0.1215 |

| MSAVI, std | 0.1853 | 0.2124 | 0.1685 |

| Index | Barley | Soybean | Wheat |

| NDVI, mean (SD) | 0.1111 | 0.1668 | 0.1632 |

| NDVI, std (SD) | 0.0475 | 0.0506 | 0.0552 |

| NDRE, mean (SD) | 0.0251 | 0.0291 | 0.0300 |

| NDRE, std (SD) | 0.0068 | 0.0072 | 0.0103 |

| GNDVI, mean (SD) | 0.0664 | 0.1178 | 0.0872 |

| GNDVI, std (SD) | 0.0273 | 0.0274 | 0.0335 |

| SAVI, mean (SD) | 0.1667 | 0.2502 | 0.2448 |

| SAVI, std (SD) | 0.0713 | 0.0759 | 0.0828 |

| MSR, mean (SD) | 0.1900 | 0.2877 | 0.3036 |

| MSR, std (SD) | 0.0897 | 0.0802 | 0.1009 |

| EVI, mean (SD) | 524423.20 | 499497.20 | 360916.60 |

| EVI, std (SD) | 33342580.00 | 31506620.00 | 22802270.00 |

| SIPI, mean (SD) | 455748.80 | 205095.20 | 383935.20 |

| SIPI, std (SD) | 24517450.00 | 12844970.00 | 20468290.00 |

| MSAVI, mean (SD) | 0.1955 | 0.3112 | 0.3350 |

| MSAVI, std (SD) | 0.0886 | 0.1425 | 0.2385 |

| Metric | LightGBM | XGBoost | CatBoost | Hybrid model |

| Barley Precision | 0.88 | 0.92 | 0.89 | 0.96 |

| Barley Recall | 0.89 | 0.92 | 0.90 | 0.95 |

| Barley F1-score | 0.89 | 0.92 | 0.89 | 0.95 |

| Soybean Precision | 0.91 | 0.94 | 0.91 | 0.95 |

| Soybean Recall | 0.81 | 0.87 | 0.83 | 0.91 |

| Soybean F1-score | 0.86 | 0.90 | 0.87 | 0.93 |

| Wheat Precision | 0.88 | 0.92 | 0.89 | 0.95 |

| Wheat Recall | 0.89 | 0.92 | 0.90 | 0.96 |

| Wheat F1-score | 0.89 | 0.92 | 0.89 | 0.95 |

| Macro avg F1-score | 0.88 | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.95 |

| Overall Accuracy | 0.88 | 0.92 | 0.89 | 0.95 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).