1. Introduction

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has rapidly transitioned from a specialized research topic to a widely adopted tool across academic, scientific, and professional environments. The emergence of generative AI systems, such as large language models (LLMs), has enabled the automation of tasks traditionally considered human-centered, including text generation, data analysis, and literature synthesis [

1]. While these technologies offer unprecedented opportunities to enhance efficiency and expand access to knowledge, their integration into higher education and research raises pressing questions concerning ethics, authorship, transparency, and academic integrity [

2,

3].

The current debate reflects diverging perspectives. Advocates emphasize the potential of AI to democratize access to knowledge, reduce workload in repetitive tasks, and support non-native speakers of English in scientific publishing [

4,

5]. However, critics warn against over-reliance on automated systems that may produce biased, fabricated, or unverifiable information, thereby threatening the reliability of scientific communication [

6,

7]. Concerns about plagiarism, loss of critical thinking skills, and erosion of accountability have further intensified the controversy [

3]. As a result, scientific publishers, universities, and policymakers are urgently formulating guidelines to regulate the responsible use of AI in research and education [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13].

Despite the growing number of position papers and editorials, there remains a lack of consolidated frameworks that integrate ethical principles, legal requirements, and practical guidelines for everyday academic work. Existing contributions often focus narrowly on plagiarism detection or data privacy, without offering a holistic view of how AI can be used responsibly throughout the research cycle—from idea generation and literature review to manuscript submission and dissemination [

14,

15]. This gap calls for a systematic and pragmatic approach that balances innovation with integrity.

The purpose of the present work is to develop an ethical and practical framework for the use of AI in academic and scientific contexts. Building on recent editorial guidelines, institutional policies, and comparative analyses of AI tools, the framework identifies risks, establishes best practices, and proposes mechanisms for transparency and accountability. Moreover, the specific objectives are: (i) Analyze institutional, editorial, and legal guidelines (such as GDPR, publisher policies, and universities) to identify common and divergent principles in the responsible use of AI in research; (ii) Compare and evaluate different AI platforms (ChatGPT, SciSpace, Paperpal, Consensus, Turnitin, etc.), highlighting their functionalities, limitations, risks, and potential contribution at each stage of the research cycle; and (iii) Propose an ethical and practical framework that integrates good practices, risks, and opportunities in all phases of academic work, including resources such as checklists and AI use statement templates.

The principal conclusion of this study is that AI can indeed support academic productivity without undermining scientific integrity, provided its use is transparent, critically assessed, and governed by clear ethical standards. By addressing both opportunities and challenges, this work contributes to the ongoing dialogue on responsible AI integration in academia. It offers students, educators, and researchers a comprehensive reference to navigate the complexities of emerging technologies while safeguarding the foundational values of science.

To achieve these objectives, the remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 (Materials and Methods) describes the research design, including the documentary analysis, comparative evaluation of AI tools, and the process used to develop the framework.

Section 3 (Results) presents the main findings, including policy analysis, tool comparison, and the proposed framework, as well as the identification of recurring risks.

Section 4 (Discussion) interprets these results considering previous studies, explores their broader implications, and outlines directions for future research, while also acknowledging the study’s limitations. Finally,

Section 5 (Conclusions) highlights the main contributions of this work and reflects on the significance of adopting responsible and transparent approaches to AI in academic and scientific contexts.

Appendix A provides exploratory examples of prompts for the ideation phase;

Appendix B compares AI tools for scientific research;

Appendix C offers templates for stating the use of AI in academic writing; and

Appendix D presents a checklist for the ethical use of AI in academic and scientific contexts.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was designed as a documentary and comparative analysis to construct an ethical and practical framework for the use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in academic and scientific work. Documentary analysis is well suited to mapping and translating high-level AI ethics principles into concrete requirements because many existing contributions to AI ethics take the form of guidelines, frameworks, and policy documents whose normative content must be extracted and compared to practice. Scholarly work shows that close reading and content extraction of guidelines reveal overlapping principles and the specific normative requirements they imply, enabling operationalization of abstract values into implementable items. The literature endorses documentary and comparative methods as rigorous, practical first steps for constructing ethical and implementable AI-use frameworks in academic research and recommends combining these with targeted empirical validation (exemplified for the ideation phase in

Appendix A) to ensure usability and effectiveness [

16,

17,

18]

The methodology combined (i) the review of institutional and editorial policies, (ii) comparative evaluation of AI-based platforms, and (iii) synthesis of ethical and legal guidelines relevant to higher education and research. A bibliographic search was performed across PubMed, Scopus, IEEE Xplore, Science Direct and Web of Science using the keywords ‘artificial intelligence tools’ and ‘scientific research.’ Priority was given to articles published between 2019 and 2025, with particular emphasis on exploring the advantages, drawbacks, and ethical considerations surrounding the use of AI.

2.1. Documentary Research and Policy Review

A systematic review of international guidelines was conducted, focusing on policies from major scientific publishers (e.g., Springer Nature, Elsevier, IEEE) and leading institutions in higher education. Relevant regulatory frameworks, including the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and copyright directives within the European Union, were also analyzed. These documents were examined to identify common principles, divergences, and emerging practices regarding the responsible use of AI in research and education.

2.2. Comparative Tool Analysis

AI platforms widely cited in similar studies [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21], such as ChatGPT (OpenAI), SciSpace, AvidNote, Consensus, Paperpal, and NotebookLM, were assessed through exploratory testing. Evaluation criteria included functionality, disciplinary specialization, cost, privacy compliance (e.g., GDPR alignment), and technical limitations. Where available, public documentation from developers was cross-checked with academic evaluations to ensure reliability.

2.3. Framework Development and Test

The collected data was organized along the research workflow: ideation, literature review, methodology planning, data collection and analysis, manuscript preparation, plagiarism/originality verification, and dissemination [

22]. For each stage, opportunities, risks, and best practices were mapped, supported by concrete examples and recommendations. The framework was iteratively refined to maximize clarity, transferability, and alignment with institutional policies.

Appendix A exemplifies prompts and results in an exploratory process for the ideation phase.

2.4. Use of Generative AI in the Study

Generative AI tools, specifically ChatGPT [

23], Elicit [

24], SciSpace [

25], and NotebookLM [

26], were employed as support during the preparation of this study. Their role included assistance in reference researching, structural organization, preliminary drafting, and language reformulation. All AI-generated outputs were critically reviewed, validated, and adapted by the human author, who assumes full responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of the final text. No automated outputs were used without verification. AI was not used for data fabrication, statistical analysis, or decision-making regarding ethical or conceptual content. This declaration aligns with best practices outlined by international publishers and institutional guidelines.

2.5. Ethics Statement

This research did not involve human or animal participants, nor the collection of sensitive personal data, and therefore did not require ethical approval.

2.6. Data and Code Availability

No new datasets or computer code were generated in this study. Supporting materials, including AI tool comparison tables, checklists, and templates for responsible AI use declarations, are provided as supplementary files.

3. Results

The study produced a comprehensive ethical and practical framework for the responsible use of artificial intelligence (AI) in academic and scientific work. The framework is structured around the main stages of the research workflow and highlights specific opportunities, risks, and recommended practices at each phase.

3.1. Policy and Ethical Guidelines

Analysis of international publishers’ guidelines (Elsevier, Springer Nature, IEEE) revealed strong consensus on three principles: (i) AI tools cannot be listed as authors, (ii) all AI use must be transparently declared, and (iii) human researchers retain full accountability for the accuracy and integrity of the content [

8,

9,

10]. Institutional policies were found to vary in detail, but most are converging toward requiring disclosure statements and training for students and staff.

3.2. Key Insights from related studies

Prompt Design: Effective prompts are clear, context-rich, sequenced, and allow for user modification and reflection. Domain-specificity and adaptability are essential.

Critical Thinking Safeguards: User control, transparency, iterative refinement, and human-in-the-loop mechanisms are critical for preserving researcher agency and preventing over-reliance on Artificial Intelligence.

Domain-Specific Considerations: related works show that ethical, technical, and methodological requirements vary by field. Human-Computer Interaction and Artificial Intelligence & Ethics are most developed in terms of prompting strategies and safeguards; Cybersecurity and Software Engineering require further empirical work.

Effectiveness: Structured, co-creative frameworks enhance creativity, appropriateness, and user satisfaction. Over-automation or lack of transparency can diminish critical engagement.

Limitations: Evidence base is heterogeneous, with some domains underrepresented and several studies available only as abstracts, limiting assessment of methodological rigor and generalizability.

3.3. Tool Comparison

The comparative evaluation of AI platforms confirmed significant differences in scope, reliability, and compliance. Broad-purpose assistants such as ChatGPT demonstrated versatility in ideation, text generation, and conceptual explanation. However, their outputs were sometimes undermined by fabricated references and sensitivity to prompt formulation, which limits reliability for rigorous academic work. Similarly, SciSpace showed strength in assisting with PDF reading and the explanation of technical content, although its coverage of languages beyond English remained limited and performance weakened with longer or highly complex documents.

By contrast, specialized writing support tools such as

Paperpal [

27] and

Grammarly [

28] proved more reliable for linguistic refinement and stylistic clarity. Their main limitation lies in their narrow scope, restricted primarily to English, and in the risk of altering the meaning of technical sentences, particularly in specialized disciplines.

Writefull Revise [

29] offered a similar focus on academic English but with integration features for platforms such as Word and Overleaf, making it useful for manuscript preparation.

Tools designed to support evidence-based research, such as

Consensus [

30],

Scite [

31], and

Semantic Scholar [

32], facilitated targeted literature searches and citation analysis. These platforms provided synthesized insights from peer-reviewed sources but suffered from limited disciplinary coverage, with stronger performance in medicine and psychology than in the humanities or engineering. Similarly,

ResearchRabbit [

33] and

Connected Papers [

34] enabled visual mapping of scholarly networks, yet their utility depended on articles having DOI metadata, which restricted applicability in certain fields.

Other platforms focused on workflow management and reference handling.

AvidNote [

35], for example, provided notetaking and project organization functions, but lacked strong integration with generative AI features. In contrast,

Zotero [

36] and

Mendeley [

37] served as robust reference managers with multilingual support and export options, though questions of data privacy have been raised in relation to Mendeley’s management by Elsevier.

Finally, tools for originality and integrity verification, including

Turnitin [

38],

Copyleaks [

39], and

GPTZero [

40], were indispensable in detecting plagiarism and identifying AI-generated text. While generally reliable, these tools were not free of error, as false positives and negatives occasionally occurred, requiring human verification of results.

A structured comparison of AI tools for academic research is shown in

Table A1,

Appendix B. Taken together, these findings demonstrate that no single tool can address the full range of academic needs. Instead, responsible integration requires combining platforms according to their strengths: generative assistants for brainstorming, specialized editors for linguistic refinement, evidence-based search engines for literature review, and integrity checkers for final verification.

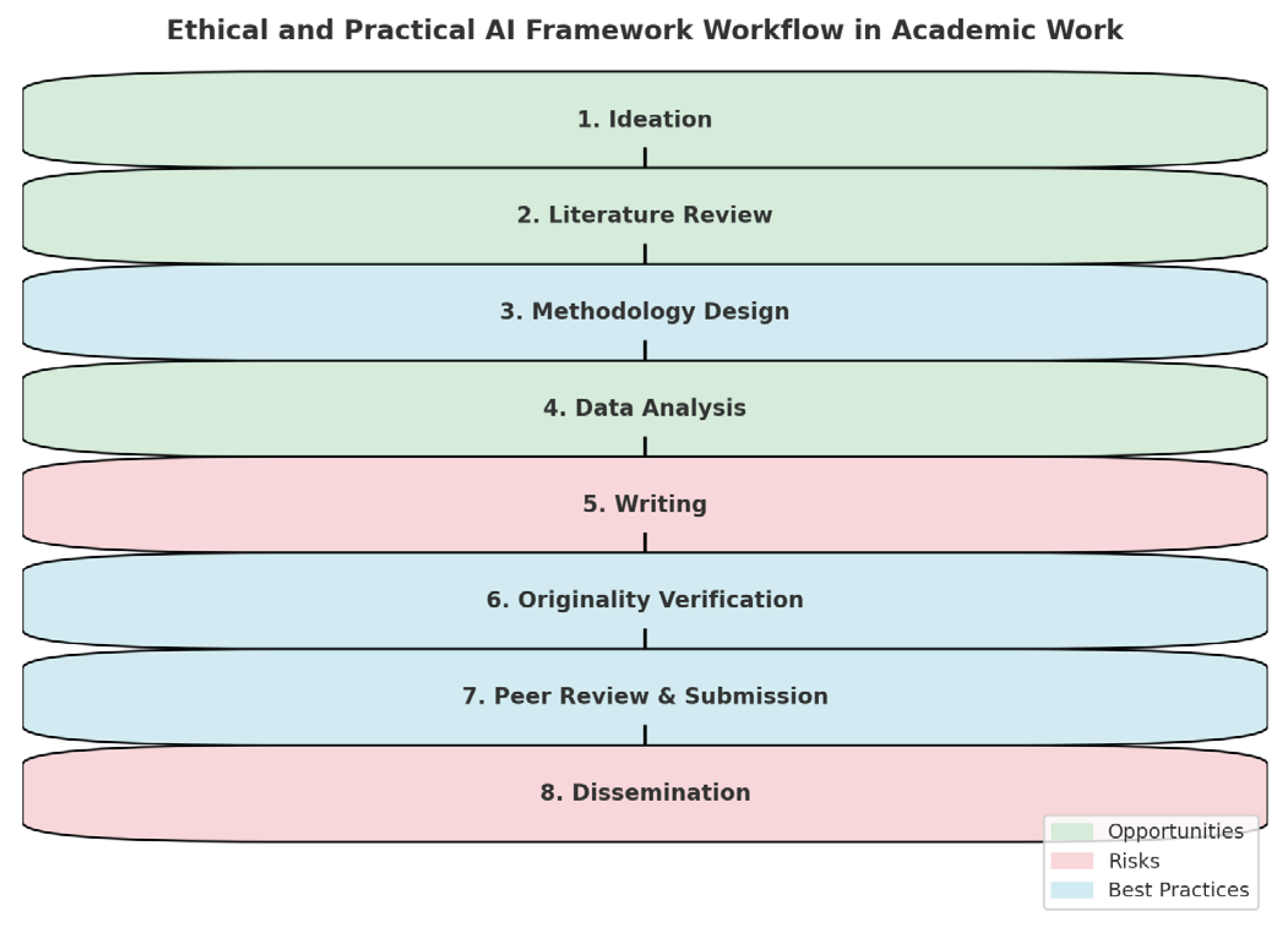

3.4. Framework Output

The proposed framework integrates ethical principles with operational guidance across eight stages of the research cycle: (1) ideation, (2) literature review, (3) methodology design, (4) data analysis, (5) writing, (6) originality verification, (7) peer review and submission, and (8) dissemination. At each stage, AI applications were mapped to potential benefits (e.g., efficiency, accessibility) and risks (e.g., plagiarism, bias, dependency). and Templates (

Appendix C – Template 1 and Template 2) and checklists for the eight stages (

Appendix D) were produced to support transparency, including a standardized declaration of AI use in academic outputs.

3.5. Key Risks Identified

Four recurring risks emerged across tools and contexts: (i) algorithmic bias and inequity reproduction, (ii) fabrication of facts and references, (iii) over-reliance leading to loss of critical skills, and (iv) unresolved concerns over data privacy and ownership. These risks underscore the need for active human oversight and institutional monitoring.

3.6. Experimental Conclusions

The results demonstrate that AI can effectively support multiple stages of academic work when used critically and transparently. However, unregulated use introduces significant threats to scientific integrity. The framework therefore provides a structured approach to maximize benefits while mitigating risks, positioning itself as a practical reference for students, educators, and researchers. The visual workflow (

Figure 1) illustrates how the proposed framework integrates ethical considerations and practical guidance throughout the academic research process. At the initial stages, AI tools provide clear

opportunities (green) to support ideation, literature review, and data analysis. However, risks (red) such as fabricated references, plagiarism, and over-reliance are more evident in the writing and dissemination phases. To mitigate these, the framework embeds

best practices (blue), particularly in methodology design, originality verification, and peer review. The sequential flow highlights that AI integration should not be considered in isolation, but as part of a continuous cycle in which opportunities must be balanced by ethical safeguards and institutional responsibilities.

Table 1 summarizes

opportunities, risks, and best practices for each of the eight stages of the framework.

4. Discussion

The results of this study confirm that artificial intelligence (AI) tools can be integrated into academic and scientific workflows in ways that improve efficiency and accessibility, but only when their limitations are explicitly acknowledged and mitigated. The framework developed here addresses a central hypothesis: that AI can support scholarly productivity without compromising academic integrity, provided that its use is transparent, critical, and governed by ethical standards.

4.1. Comparison with Previous Studies

Earlier work has underscored both the promise and perils of AI in academia. Proponents have highlighted its value for democratizing access to knowledge and assisting non-native speakers with scientific writing [

1,

2]. Our findings align with this view by showing clear opportunities in the ideation, literature review, and data analysis stages, where AI tools demonstrated genuine potential to enhance productivity. At the same time, critical voices have warned of fabricated references, plagiarism risks, and the erosion of critical thinking skills [

41]. The risks identified in this study, particularly during writing and dissemination, strongly support these concerns and emphasize the need for human oversight.

4.2. Interpretation of Findings

The structured framework developed here contributes by bridging the gap between narrowly focused guidelines (e.g., plagiarism detection or GDPR compliance) and a more holistic, workflow-oriented approach. By mapping opportunities, risks, and best practices across the full research cycle, the framework provides practical clarity where many institutional policies remain vague. This positions the model not merely as a compliance tool but as an educational and operational guide that can be adapted across disciplines.

4.3. Implications

The implications extend beyond individual researchers. Institutions can adopt the framework as part of academic integrity policies, training curricula, and internal quality assurance processes. Publishers may also find the model useful for designing standardized disclosure statements for AI use. More broadly, the framework contributes to the ongoing international debate on whether AI constitutes an assistant, collaborator, or threat in academic contexts. Our findings support the view that AI should be treated as an assistive tool rather than a co-author, consistent with editorial positions from major publishers [

8,

9,

10].

4.4. Future Directions

Future research should focus on empirically testing the framework in real-world academic settings, for instance, by evaluating how students and researchers adopt its recommendations and whether it effectively reduces misconduct. Comparative studies across regions would be valuable to capture cultural and regulatory differences in AI adoption. Finally, as AI technologies evolve rapidly, longitudinal research is essential to monitor new risks, such as multimodal content fabrication or environmental impacts of large-scale AI use, and to update the framework accordingly.

4.5. Limitations

This study was primarily based on documentary analysis, comparative evaluation of AI tools, and synthesis of existing institutional and editorial guidelines. While this approach enabled the development of a comprehensive framework, it does not capture empirical data on how researchers, students, or institutions currently apply AI in practice. The effectiveness of the proposed framework in reducing misconduct, improving transparency, or fostering responsible AI adoption remains to be validated in real-world academic contexts. Future empirical studies, including surveys, case studies, and controlled interventions, will be necessary to test, refine, and expand the applicability of the framework across disciplines and cultural settings.

5. Conclusions

This study developed a comprehensive framework for the ethical and practical use of artificial intelligence in academic and scientific work. By systematically reviewing institutional policies, editorial guidelines, and available AI platforms, the framework mapped opportunities, risks, and best practices across all stages of the research workflow. The principal finding is that AI can indeed enhance efficiency and accessibility in scholarly work, but its value is contingent upon transparent disclosure, critical human oversight, and institutional safeguards.

The framework makes several contributions. First, it consolidates scattered recommendations into a single, workflow-oriented model that is applicable across disciplines. Second, it provides practical resources (including checklists and standardized declaration templates) that institutions, publishers, and researchers can readily adopt. Finally, it reinforces the principle that AI should remain an assistive tool, not a substitute for human judgment, creativity, or accountability.

Looking ahead, the study underscores the importance of continuous monitoring and adaptation as AI technologies evolve. Universities and publishers must remain proactive in updating their policies, while researchers and students must cultivate digital literacy and ethical responsibility. By balancing technological innovation with the enduring values of integrity and transparency, the proposed framework offers a pathway toward responsible and sustainable integration of AI into the future of academic and scientific work.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Laercio Cruvinel; methodology, Laercio Cruvinel and Héctor Ascama; software, Laercio Cruvinel; investigation, all; writing—original draft preparation, Laercio Cruvinel and Héctor Ascama; writing—review and editing, all. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by national funds through FCT - Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia - as part of the project CI2 - Refª UID/05567/2023.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

(1) During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used ChatGPT 4, Elicit, SciSpace, and NotebookLM for the purposes of assistance in reference researching, structural organization, preliminary drafting, and language reformulation. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication. (2) This work was funded by national funds through FCT - Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia - as part of the project CI2 - Refª UID/05567/2023.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| LLM |

Large Language Model |

| GDPR |

General Data Protection Regulation |

| IEEE |

Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers |

Appendix A

Exploratory Examples for Ideation Phase

Prompt: Suggest a prompt for the ideation phase of a scientific research in the field of Artificial Intelligence & Ethics. Stimulate AI support while ensuring critical thinking remains with the researcher. The resulting prompt is to ask five relevant questions.

Result from ChatGPT 5: “Suggest five original and feasible research questions at the intersection of Artificial Intelligence and Computer Science education. Focus on challenges such as algorithmic bias, explainable AI, or the integration of AI tools (e.g., large language models) into higher education. For each question, briefly explain (i) its significance, (ii) potential methodological approaches to investigate it, and (iii) the expected impact of addressing the question on academic integrity and technological innovation.”

Result from Elicit: “The reviewed studies show that well-crafted prompts can harness Artificial Intelligence while keeping researchers in charge. In Artificial Intelligence & Ethics, structured prompts via large language models and bibliometric approaches lead to questions that probe social impact, ethical dilemmas, policy, bias, and inclusivity.”

What social impacts arise from integrating AI into research?

What ethical dilemmas emerge with AI-assisted ideation?

How do current policy frameworks address AI-driven challenges?

In what ways can bias be identified and mitigated through prompt design?

How can prompts foster inclusivity in AI-supported research?

Selected prompt from ChatGPT 5:

Suggest five original and feasible research questions at the intersection of Artificial Intelligence and Computer Science education. Focus on challenges such as algorithmic bias, explainable AI, or the integration of AI tools (e.g., large language models) into higher education. For each question, briefly explain (i) its significance, (ii) potential methodological approaches to investigate it, and (iii) the expected impact of addressing the question on aca-demic integrity and technological innovation.

Result summarized from SciSpace: “I’ve developed five comprehensive, original research questions at the intersection of AI and Computer Science education. Let me provide you with a summary:“

Investigates how to systematically integrate bias education throughout CS programs (not just ethics courses) to produce graduates who proactively design equitable AI systems.

Develops frameworks for teaching XAI concepts to students in adjacent roles (product management, UX, policy) without requiring deep mathematical expertise, enabling better cross-functional collaboration.

Addresses the urgent crisis of how to assess authentic learning when AI can complete programming assignments instantly, proposing assessment redesigns that acknowledge LLMs as legitimate professional tools.

Examines whether AI-powered tutoring can improve outcomes in introductory CS courses while maintaining equity and enhancing (rather than replacing) human pedagogical relationships.

Proposes teaching students to anticipate how AI systems can be manipulated, misused, or fail—developing “red team” thinking as a core competency for building robust, secure systems.

Appendix C

AI Use Statement Templates in Academic Papers

We suggest two adjustable models: one for limited use and one for extensive, transparent use. These models can be adapted by institutions or authors according to the level of ethical requirements and the evaluation policy.

The use of generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools in the production of academic work must be properly identified and declared, in accordance with principles of integrity, transparency and accountability. The templates below can be included at the end of the document, in the introduction, or as a specific annex.

Template 1 – Statement of Limited Use of AI (Limited Assistance)

Declaration of use of Artificial Intelligence tools

The present work was carried out autonomously, being the full responsibility of the author(s) as to its content, structure and argumentation.

Artificial Intelligence tools (namely: [e.g., Grammarly, DeepL, ChatGPT]) were used in a limited way, exclusively to support the:

-

1.

Spelling and grammar review;

-

2.

Translation of excerpts between languages;

-

3.

Rephrasing of sentences for greater textual clarity.

The intellectual authorship of all ideas, analyses and conclusions belongs entirely to the author(s). AI was not used to generate scientific content or to replace critical thinking or bibliographic foundation.

Date:____/____/______

Full name of the author: ____________________________________

Signature:___________________________________________

Template 2 – Statement of extensive and transparent use of AI (with phased breakdown)

Detailed statement of use of Artificial Intelligence tools

The present work benefited from the support of generative Artificial Intelligence tools as part of the academic production process. All conceptual, methodological and analytical decisions were supervised by the author(s), and compliance with the principles of scientific integrity was ensured.

The following describes how the tools were used:

-

1.

Ideation and structuring phase: ChatGPT was used to suggest topics and structure an initial work plan proposal.

-

2.

Literature review: Elicit and Scite were used to locate relevant articles and generate abstracts of scientific papers, which were later verified by the authors.

-

3.

Writing and proofreading: ChatGPT and Grammarly were used to rewrite paragraphs, improve textual cohesion, and adjust technical vocabulary.

-

4.

Formatting and normalization: Tools such as Zotero, Paperpile, and Word AI have been used to generate or verify bibliographic references.

At no time was AI-generated content used without review, validation, and critical adaptation by the author(s). All the sources mentioned were consulted directly.

Date:____/____/______

Full name of the author: ____________________________________

Signature:___________________________________________

Appendix D

Quick Checklists (by Job Phase)

Phase 1: Ideation and definition of the research problem

I consulted human and academic sources in addition to AI suggestions

I validated the relevance of the topic with the supervisor or research group

I used brainstorming tools (e.g., ChatGPT, Scite Assistant) with well-defined prompts

Interactions with AI were recorded in a logbook or research note

Potential biases in the type of ideas suggested by the tools were identified

Phase 2: AI-assisted literature review

I used tools with access to legitimate scientific databases (e.g., Research Rabbit, Elicit, Connected Papers)

I manually checked all references before citing them

I avoided copying entire passages without rephrasing them with my own thought

I indicated in the work whether I used AI for article synthesis or classification

I avoided relying on auto-generated summaries without reading the originals

Phase 3: Methodological planning and instrument design

I used AI only as a support for formulating hypotheses or instruments, never as a substitute for critical reasoning

I reviewed the forms, interviews or questionnaires with human supervision

I considered ethical, privacy, and data validity limitations

I tested the neutrality of the AI-suggested questions

The role of AI in planning, if applicable, was appropriately documented

Phase 4: Data collection and analysis

I used AI tools that are compatible with the study data formats

The results of AI-powered classifications, clusters, or inferences were manually validated

I reviewed graphs and visualizations to avoid biased interpretations

I ensured that I did not enter sensitive data into public AI platforms

I included in the report a description of the tools and configurations used

Phase 5: Writing and formatting the manuscript

I used AI only as a writing aid (e.g., rewriting paragraphs, suggesting synonyms)

I maintained the intellectual authorship of ideas, structure and argumentation

I avoided using AI to write all the theoretical or analytical sections

I carefully reviewed the generated texts before integrating them

I indicated at the end of the document (or footnote) that AI was used as a support tool

Phase 6: Originality and Compliance Check

I tested the document in plagiarism detection tools (e.g., Turnitin, Copyscape)

I checked the originality of the generated text with tools like GPTZero or Sapling AI Detector

I rewrote excessively AI-dependent parts

I confirmed that all the sources cited really exist and were consulted

I maintained consistency between references, bibliography and citations

Phase 7: Submission and peer review

I have drafted a transparent statement about the use of AI in the manuscript

I prepared responses to the reviewers with their own language, without the use of AI without supervision

I reviewed the publisher’s or conference’s instructions for the permissible use of AI

I submitted the manuscript in accordance with the ethical standards of the institution

I have archived previous versions and proofs of revision for possible verification

Phase 8: Impact disclosure and monitoring

Disseminated the work on legitimate academic networks (e.g., ORCID, ResearchGate, PubPeer)

I monitored the impact with tools like Altmetric or PlumX

I avoided using AI to create promotional briefs without human supervision

I respected the licensing policy when sharing the work publicly

I updated my resume and academic profiles with the final production

References

- Z. Chen et al., “Research integrity in the era of artificial intelligence: Challenges and responses,” Jul. 05, 2024, Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. [CrossRef]

- J. Miao, C. Thongprayoon, S. Suppadungsuk, O. A. Garcia Valencia, F. Qureshi, and W. Cheungpasitporn, “Ethical Dilemmas in Using AI for Academic Writing and an Example Framework for Peer Review in Nephrology Academia: A Narrative Review,” Nephrology Academia: A Narrative Review. Clin. Pract. 2024, vol. 14, pp. 89–105, 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. Konwar, “Ethical Considerations in The Use of AI Tools Like ChatGPT and Gemini in Academic Research,” Turkish Online Journal of Qualitative Inquiry (TOJQI), vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 13–16, 2025. [CrossRef]

- N. Ruiz, L. Martinez, and M. C. Laplagne, “The impact of Artificial intelligence in higher education,” in 2023 South American Conference on Visible Light Communications, SACVLC 2023, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2023, pp. 153–158. [CrossRef]

- M. Pan, J. Wang, and J. Wang, “Application of Artificial Intelligence in Education: Opportunities, Challenges, and Suggestions,” in Proceedings - 2023 13th International Conference on Information Technology in Medicine and Education, ITME 2023, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2023, pp. 623–627. [CrossRef]

- V. Aliukonis, M. Poškutė, and E. Gefenas, “Perish or publish dilemma: Challenges to responsible authorship,” Mar. 01, 2020, MDPI AG. [CrossRef]

- Steponenaite and B. Barakat, “Plagiarism in AI empowered world,” in Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 14021, M. Antona and C. Stephanidis, Eds., Springer Nature Switzerland, Jul. 2023, pp. 434–442. [CrossRef]

- Elsevier, “Generative AI policies for journals,” Online. Accessed: Jun. 27, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.elsevier.com/about/policies-and-standards/generative-ai-policies-for-journals.

- Springer Nature, “Research Integrity: An Introduction for Researchers,” Online. Accessed: Jun. 27, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.springernature.com/gp/authors/campaigns/research-integrity-course.

- IEEE, “Ethical Requirements,” Online. Accessed: Jun. 27, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://journals.ieeeauthorcenter.ieee.org/become-an-ieee-journal-author/publishing-ethics/ethical-requirements/.

- Harvard University, “Initial guidelines for the use of Generative AI tools at Harvard,” Online. Accessed: Jun. 27, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.huit.harvard.edu/ai/guidelines.

- Instituto Superior Técnico - Conselho Pedagógico, “Sobre a utilização de IA nos métodos de ensino e de avaliação de conhecimentos,” Online. Accessed: Jun. 27, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://direito.up.pt/digeucit/wp-content/uploads/sites/968/2024/01/ferramentas-de-ai-no-ensino-v8-1.pdf.

- União Europeia, “Regulamento (UE) 2016/679 do Parlamento Europeu e do Conselho, de 27 de abril de 2016, relativo à proteção das pessoas singulares no que diz respeito ao tratamento de dados pessoais e à livre circulação desses dados (Regulamento Geral sobre a Proteção de Dados),” Jornal Oficial da União Europeia, no. L119, pp. 1–88, May 2016, Accessed: Jun. 27, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PT/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32016R0679.

- D. Eacersall et al., “Navigating Ethical Challenges in Generative AI-Enhanced Research: The ETHICAL Framework for Responsible Generative AI Use,” 2024. Accessed: Jun. 27, 2025. [Online]. Available: Eacersall, D., “Navigating Ethical Challenges in Generative AI-Enhanced Research: The ETHICAL Framework for Responsible Generative AI Us.

- D. S. Fowler, “AI in Higher Education,” Journal of Ethics in Higher Education, no. 3, pp. 127–143, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- N. L. Crossnohere, M. Elsaid, J. Paskett, S. Bose-Brill, and J. F. P. Bridges, “Guidelines for Artificial Intelligence in Medicine: Literature Review and Content Analysis of Frameworks,” J Med Internet Res, vol. 24, no. 8, p. e36823, 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. Prem, “From ethical AI frameworks to tools: a review of approaches,” AI and Ethics, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 699–716, 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Ryan and B. C. Stahl, “Artificial intelligence ethics guidelines for developers and users: clarifying their content and normative implications,” Journal of Information, Communication and Ethics in Society, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 61–86, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- F. Branda, M. Ciccozzi, and F. Scarpa, “Artificial intelligence in scientific research: Challenges, opportunities and the imperative of a human-centric synergy,” J Informetr, vol. 19, no. 4, p. 101727, Nov. 2025. [CrossRef]

- B. N. Hryciw, A. J. E. Seely, and K. Kyeremanteng, “Guiding principles and proposed classification system for the responsible adoption of artificial intelligence in scientific writing in medicine,” Front Artif Intell, vol. 6, 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Khalifa and M. Albadawy, “Using artificial intelligence in academic writing and research: An essential productivity tool,” Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine Update, vol. 5, p. 100145, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- L. A. Oliveira, Dissertação e Tese em Ciência e Tecnologia segundo Bolonha. Lidel, 2011.

- OpenAI, “ChatGPT,” Online. Accessed: Jun. 29, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://openai.com/chatgpt/.

- Elicit Research, “Elicit,” Online. Accessed: Jun. 29, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://elicit.com/.

- PubGenius Inc., “Scispace,” Online. Accessed: Jun. 29, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://scispace.com/.

- Google, “NotebookLM,” Online. Accessed: Jun. 29, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://notebooklm.google/.

- Cactus Communications, “Paperpal,” Online. Accessed: Jun. 29, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://paperpal.com/.

- Inc. Grammarly, “Grammarly,” Online. Accessed: Jun. 29, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.grammarly.com/.

- Writefull, “Writefull,” Online. Accessed: Jun. 29, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.writefull.com/.

- Consensus, “Consensus,” Online. Accessed: Jun. 29, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://consensus.app/.

- Research Solutions, “Scite_,” Online. Accessed: Jun. 29, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://scite.ai/.

- The Allen Institute for Artificial Intelligence, “Semantic Scholar,” Online. Accessed: Jun. 29, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.semanticscholar.org/.

- Research Rabbit, “ResearchRabbit,” Online. Accessed: Jun. 29, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.researchrabbit.ai/.

- Connected Papers, “Connected Papers,” Online. Accessed: Jun. 29, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.connectedpapers.com/.

- Avidnote, “Avidnote,” Online. Accessed: Jun. 29, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://avidnote.com/.

- Digital Scholar, “Zotero,” Online. Accessed: Jun. 29, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.zotero.org/.

- Elsevier, “Mendeley,” Online. Accessed: Jun. 29, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.mendeley.com/.

- Turnitin LLC, “Turnitin,” Online. Accessed: Jun. 29, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.turnitin.com/.

- Copyleaks, “Copyleaks,” Online. Accessed: Jun. 29, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://copyleaks.com/pt/.

- GPTZero, “GPTZero,” Online. Accessed: Jun. 29, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://gptzero.me/.

- S. Dinçer, “The use and ethical implications of artificial intelligence in scientific research and academic writing,” Educational Research & Implementation, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 139–144, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).