1. Introduction

Differentiated thyroid cancer is the most prevalent endocrine malignancy, with generally favorable outcomes following surgical and, where indicated, radioiodine treatment. Notably, residual or metastatic DTC cells may retain TSH-receptors, and suppressing TSH can reduce the stimulation of any remaining thyroid cancer cells, potentially reducing the risk of recurrence and improving disease-free survival [

1]. Thus, modulation of TSH levels through levothyroxine therapy is a cornerstone of DTC management. For a long time most DTC patients underwent long term TSH suppression (i.e., <0.1 mIU/L); however, TSH suppression beyond low-normal levels has not demonstrated clear recurrence reduction in low-risk patients with excellent response (i.e., the large majority of DTC patients nowadays) and potential adverse effects of prolonged TSH suppression, including atrial fibrillation, heart failure, decreased bone mineral density and symptoms of thyroid overactivity, require careful consideration [

2]. Accordingly, TSH measurement is the cornerstone test for assessing appropriate levothyroxine dosing and avoiding inappropriate TSH suppression or elevation, respectively. However, although current TSH immunometric assays are standardized against the 2

nd International Standard (IS) - WHO 80/558, concerns about inter-assay variability persist, especially since TSH values influence the long-term intensity of thyroxine treatment [

3]. Differences in antibody configuration, calibration, and detection systems may lead to inconsistencies in TSH measurement across assay platforms, potentially altering treatment decisions. The 2015 American Thyroid Association (ATA) guidelines recommended tailored TSH suppression according to the patient’s risk category after initial treatment for DTC: high risk [TSH ≤ 0.1 mIU/L], intermediate risk [TSH 0.1–0.5 mIU/L], and low risk [TSH 0.5–2 mIU/L]. Furthermore, TSH values should be re-titrated during follow-up according to the patient’s dynamic response to therapy. Specifically, TSH levels between 0.5–2 mIU/L and 0.1–0.5 mIU/L were recommended for patients with ER and those with BIR or IndR, respectively, whereas levels ≤ 0.1 mIU/L were advised in patients with SIR (

Table 1) [

4]. Although these criteria remain the foundation of TSH modulation, achieving and maintaining target TSH levels in real-world practice remains challenging, as shown by many cohort studies and meta-analyses [

5]. Finally, the 2025 ATA guidelines, released in October 2025, have introduced relevant updates. First, instead of fixed numerical cutoffs, the recommended TSH targets are now expressed relative to the assay-specific reference range, acknowledging inter-assay variability and harmonization challenges. Second, TSH suppression is now stratified more conservatively: values within the reference range are considered appropriate for patients with ER or IndR, whereas values below the reference range are advised for those with BIR or SIR [

6]. These refinements reflect a shift toward individualized biochemical monitoring based on assay performance and patient risk dynamics.

Therefore, this study was designed to examine how closely real-world TSH management reflects ATA guideline targets and to quantify the influence of assay-specific reference ranges on risk-adapted TSH modulation after DTC treatment.

2. Material and Methods

We collected residual serum specimens from patients with histologically confirmed DTC, who had undergone clinical visit(s) with TSH, Tg, and TgAb testing during the previous 5 years in our centers. All samples were collected in the morning fasting state, and residual specimens were frozen at -80° C. For the purpose of the present study, sera were included if

a. the residual volume was greater than 0.5 mL,

b. the sample had undergone ≤2 freeze/thaw cycles, and

c. sera were obtained at least 12 months after primary treatment (i.e., total thyroidectomy plus radioiodine) and six months after the first response assessment. Sera were transported at -80° C by certified carriers and centralized at the Laboratory of Clinical Chemistry, Gruppo Ospedaliero Moncucco and Medysin® AG, Lugano, Switzerland. The patients’ disease status (i.e., response to treatment) at the time of blood drawing was centrally assigned by an experienced endocrine oncologist (L.G.) according to the ATA 2015 guidelines [

4], based on a longitudinal analysis of standardized clinical files. Serum TSH concentrations were simultaneously measured using three automated immunoassay platforms [Elecsys® TSH assay (Roche), Atellica® IM TSH (Siemens), and Alinity TSH (Abbott)]. All assays were calibrated and operated according to the manufacturers' protocols. Quality controls were within acceptable ranges during the measurement period. Relevant analytical characteristics of different TSH immunoassays are summarized in

Table 2.

2.1. Statistical Analysis

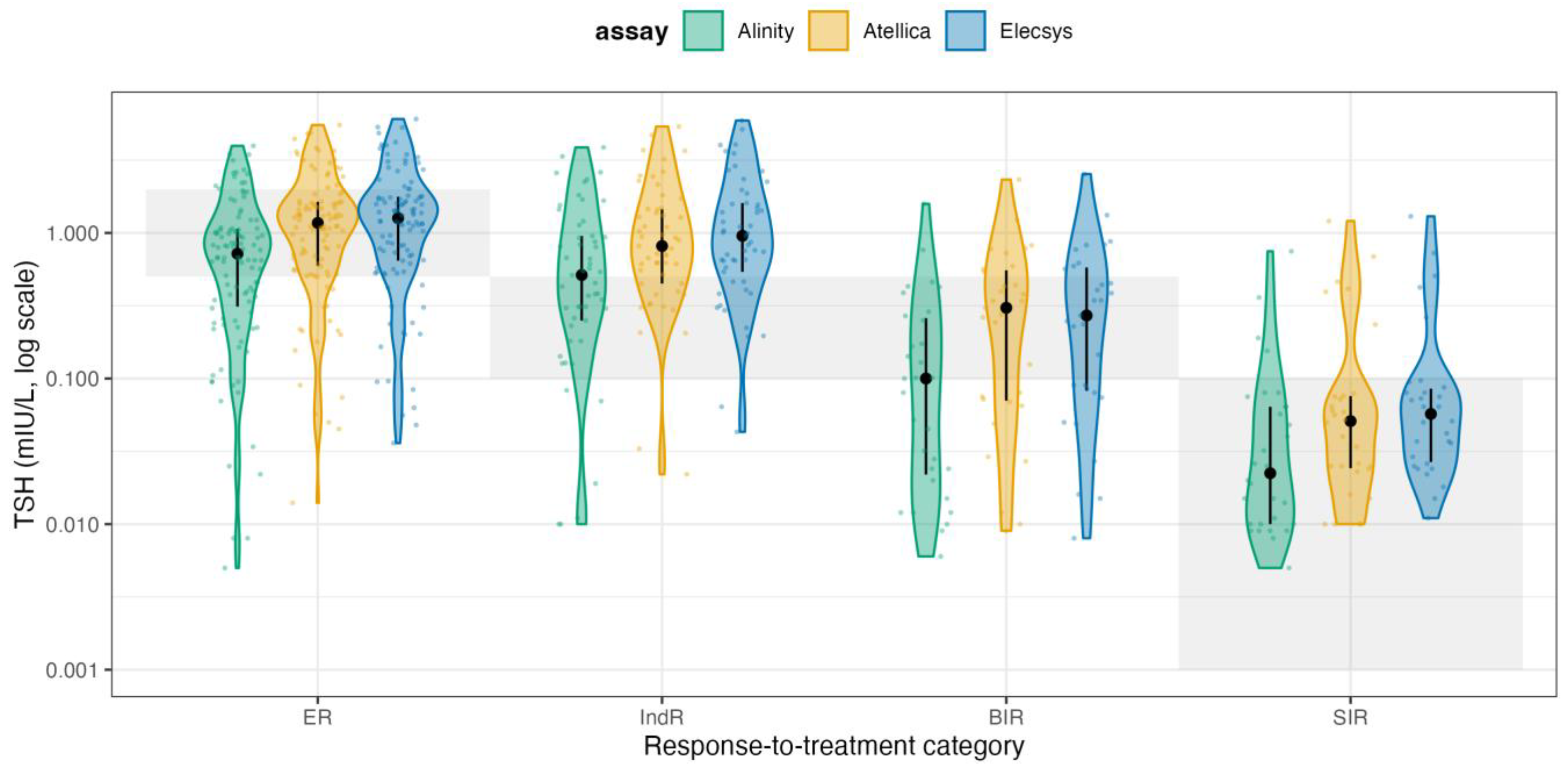

Statistical analysis addressed two aims: (i) analytical comparability of TSH measurements across immunoassays, and (ii) clinical appropriateness of TSH suppression relative to guideline targets. The agreement between Elecsys, Atellica, and Alinity was evaluated using paired serum samples, with Passing-Bablok regression (a nonparametric, robust method to outliers) to estimate the slope and intercept, along with 95% confidence intervals. Additionally, Bland–Altman analysis was performed to quantify the mean bias and 95% limits of agreement. For each patient, an experienced endocrinologist assigned a response-to-therapy category, ER, IndR, BIR, and SIR according to the ATA criteria. For each category, we defined a target TSH range according to the ATA 2015 recommendations (ER: 0.5-2.0 mIU/L; IndR/BIR: 0.1-0.5 mIU/L; SIR: <0.1 mIU/L). We then reclassified patients using the ATA 2025 approach, employing assay-specific reference ranges (RRs) (

Table 2). ER and IndR patients were considered in-target when TSH was within the platform’s RR, whereas BIR and SIR patients were in-target when TSH was below the platform’s lower reference limit. Accordingly, no category below the target applies to BIR and SIR. For each assay platform and response category, measured TSH was classified as below, within, or above the recommended target range, and the proportion of patients in each stratum was summarized (n and %). To visualize these findings, adherence to guideline targets was displayed using stratified heatmaps, and the overall distribution of TSH values across response categories and assays was displayed using violin plots on a log10 scale with overlaid guideline target bands. All analyses were performed in R (version 4.4.2).

3. Results

Serum samples from 220 consecutive patients with DTC were included in this study. Baseline demographic, pathological, and clinical data are summarized in

Table 3. The cohort had a slight female predominance (124/220, 56%), and the majority of tumors were papillary thyroid carcinoma (181/220, 82%), followed by follicular thyroid carcinoma (33/220, 15%). Most patients were AJCC stage I or II at presentation (109/220 [50%] stage I, 74/220 [34%] stage II), whereas only 11/220 (5%) were stage IV. At the time of serum sampling, the response-to-therapy status according to ATA categories indicated that 106/220 (48%) patients had ER, 53/220 (24%) had IndR, 31/220 (14%) had BIR, and 30/220 (14%) had SIR. The mean age at sampling was 50.3 ± 20.4 years.

3.1. Agreement Between Different TSH Immunoassays

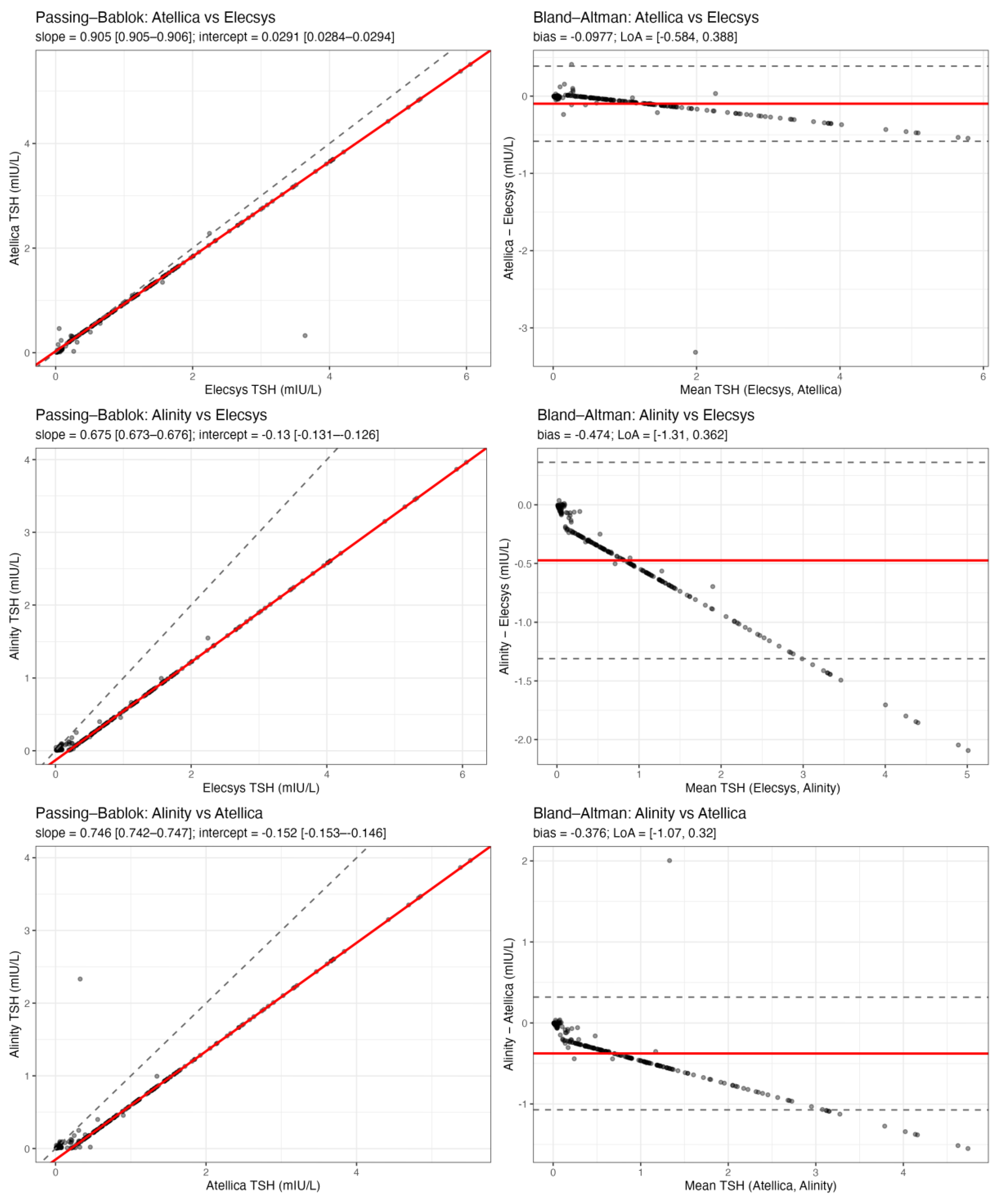

Pairwise method comparison between the three TSH immunoassays (Elecsys, Atellica, and Alinity) demonstrated high analytical agreement and only minor systematic differences (

Figure 1).

Passing-Bablok regression for Atellica vs Elecsys yielded a slope of 0.905 (95% CI 0.905-0.906) and an intercept of 0.029 mIU/L (95% CI 0.028-0.029), indicating a small proportional difference but essentially no constant bias. For Alinity vs Elecsys, the slope was 0.675 (95% CI 0.673-0.676) and the intercept -0.130 mIU/L (95% CI -0.131 to -0.126), consistent with slightly lower absolute TSH values reported by Alinity, particularly at higher concentrations. For Alinity vs Atellica, the slope was 0.746 (95% CI 0.742-0.747) and the intercept -0.152 mIU/L (95% CI -0.153 to -0.146), again supporting a proportional underestimation by Alinity relative to the comparator assay. Bland-Altman analysis confirmed that these differences were small in magnitude and unlikely to influence clinical decision-making. The mean bias (Atellica - Elecsys) was -0.098 mIU/L, with 95% limits of agreement from -0.584 to +0.388 mIU/L. The mean bias (Alinity - Elecsys) was -0.474 mIU/L, with limits of agreement from -1.31 to +0.36 mIU/L. The mean bias (Alinity - Atellica) was -0.376 mIU/L, with limits of agreement from -1.07 to +0.32 mIU/L. Negative bias values indicate that Atellica and especially Alinity tend to report slightly lower TSH values than Elecsys on average. Importantly, even the widest limits of agreement remain well within ranges that would not generally alter levothyroxine management (i.e., they do not move patients across clinically meaningful TSH cutoffs such as 0.1, 0.5, or 2.0 mIU/L in a systematic way). Overall, these data indicate that the three platforms are analytically interchangeable for longitudinal follow-up of DTC patients, and that the variability observed in clinical practice is unlikely to be driven by assay discordance.

3.2. TSH Values Outside Target Ranges by Response Class

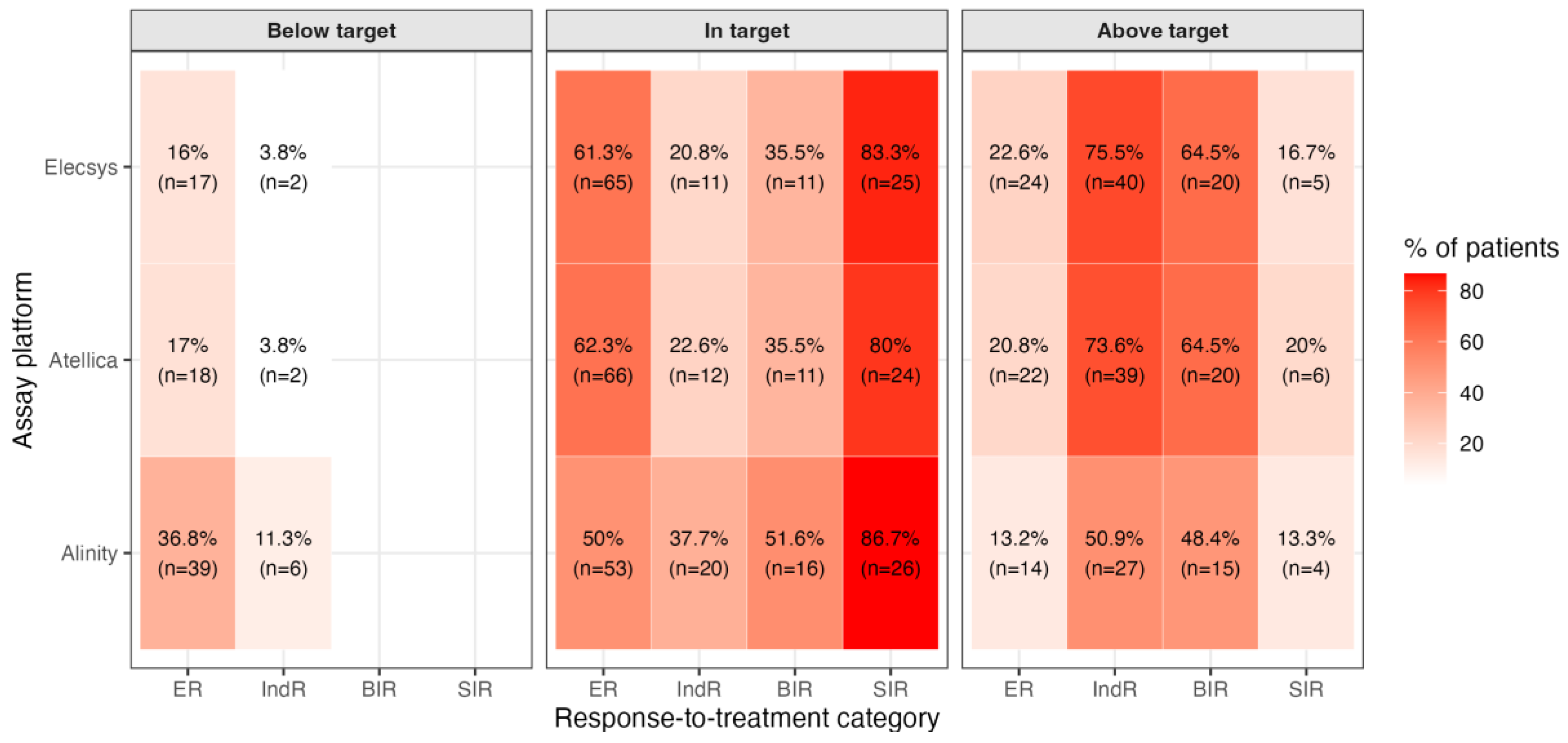

We next assessed whether the measured TSH values were consistent with guideline-defined targets. For each patient, and for each assay (Elecsys, Atellica, Alinity), we classified the observed TSH as below, within, or above the recommended range for that patient’s response-to-therapy category. Targets were first defined according to the ATA 2015 guidance: 0.5-2.0 mIU/L for ER, 0.1-0.5 mIU/L for IndR and BIR, and <0.1 mIU/L for SIR. We then repeated the same classification using a response-adapted framework consistent with the evolving ATA 2025 approach, which explicitly allows progressive relaxation of TSH suppression. Under the ATA 2015 targets, we observed marked deviations from guideline recommendations, and the pattern of deviation depended strongly on the clinical response category (

Figure 2A).

Among patients with ER, a considerable fraction remained more suppressed than recommended: between 16.0% and 36.8% of ER patients (n = 17-39, depending on assay) had TSH values below 0.5 mIU/L, i.e., below the guideline target range of 0.5-2.0 mIU/L despite being considered disease-free. This suggests persistent overtreatment and prolonged TSH suppression in a group for whom current practice guidelines generally recommend de-escalation. The opposite phenomenon emerged in patients who did not have an unequivocally excellent response. In IndR, the dominant deviation was under-suppression: up to 75.5% of IndR patients (n = 40) had TSH values above 0.5 mIU/L, i.e., above the recommended range of 0.1-0.5 mIU/L. A similar pattern was observed in the BIR group, where 48.4% to 64.5% of patients (n = 15-20) were above target. In other words, in patients with biochemical or indeterminate evidence of possible residual disease, TSH was often higher than the range recommended for oncologic safety. By contrast, TSH management in patients with SIR, who by definition have persistent structural disease and are expected to remain fully suppressed, was largely aligned with guideline expectations: 80.0% to 86.7% of SIR patients (n = 24-26) were within the recommended suppression target (<0.1 mIU/L), and only a minority exceeded 0.1 mIU/L. Using the ATA 2025 assay-specific targets (within reference range(RR) for ER and IndR, below the lower reference limit for BOR and SIR), the pattern of apparent non-adherence changed meaningfully (

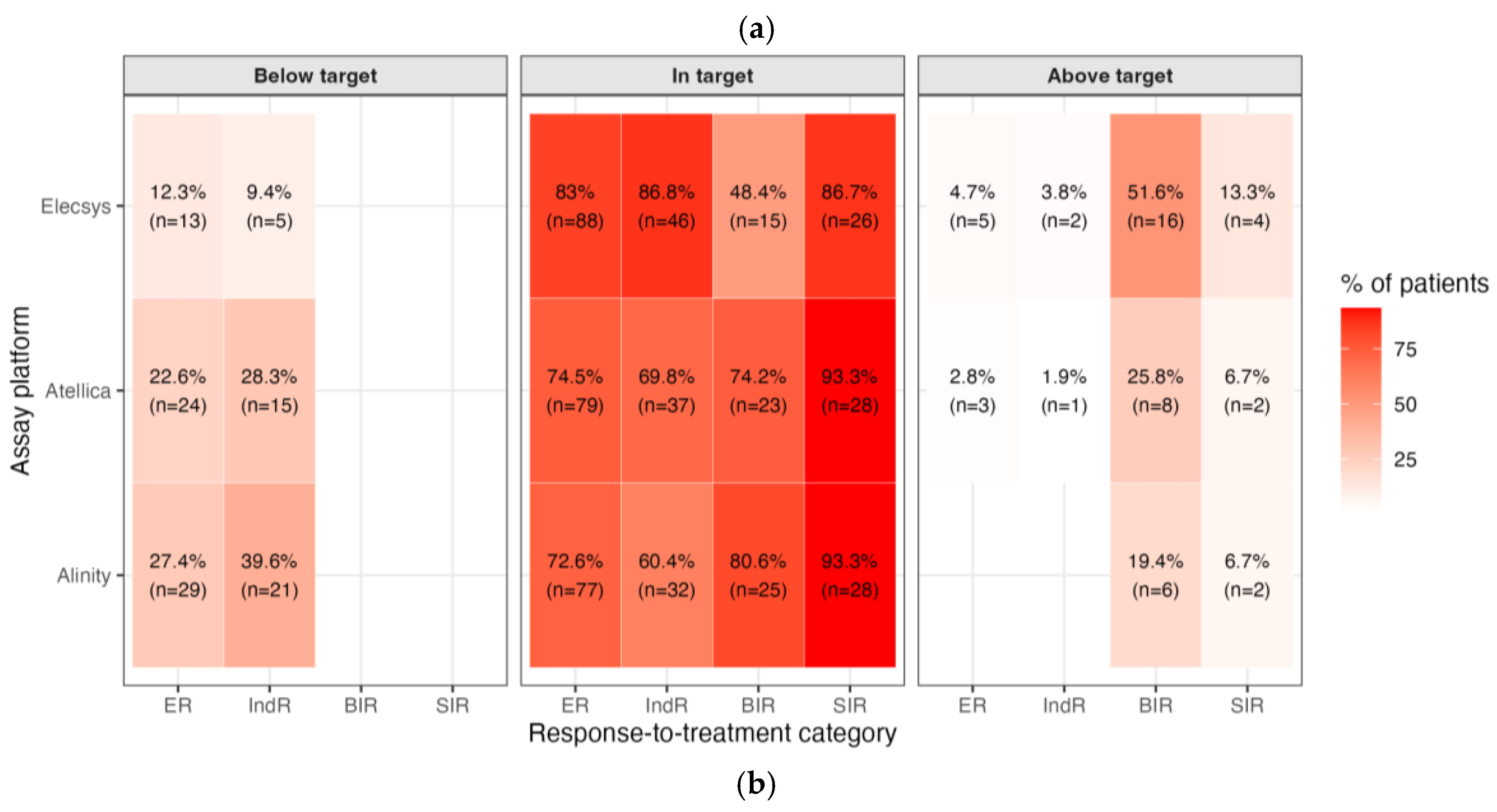

Figure 2B).

In ER, the share in-target rose to 72.6-83.0% (Alinity 72.6%, Atellica 74.5%, Elecsys 83.0%), with residual over-suppression (i.e., below the RR) in 12.3-27.4% and very few above RI (0-4.7%). In IndR, most patients were also in target (60.4-86.8%), though a non-trivial fraction remained below the RR (9.4-39.6%), while above-RR cases were rare (0-3.8%). For BIR, where the therapeutic goal is TSH below the assay’s RRs, 48.4-80.6% of patients were in-target, while 19.4-51.6% were above the RR (i.e., below-target cells apply). Finally, in SIR patients, adherence to full TSH suppression was high across platforms (86.7-93.3% in-target) with only 6.7-13.3% above RRs. Overall, assay-specific 2025 targets classify a much larger share of ER and IndR patients as appropriately managed while still highlighting residual undersuppression in part of the BIR group and a small minority of SIR patients, respectively. To visualize how these effects distribute across the entire TSH spectrum, we plotted violin distributions by response class and assay on a log scale (

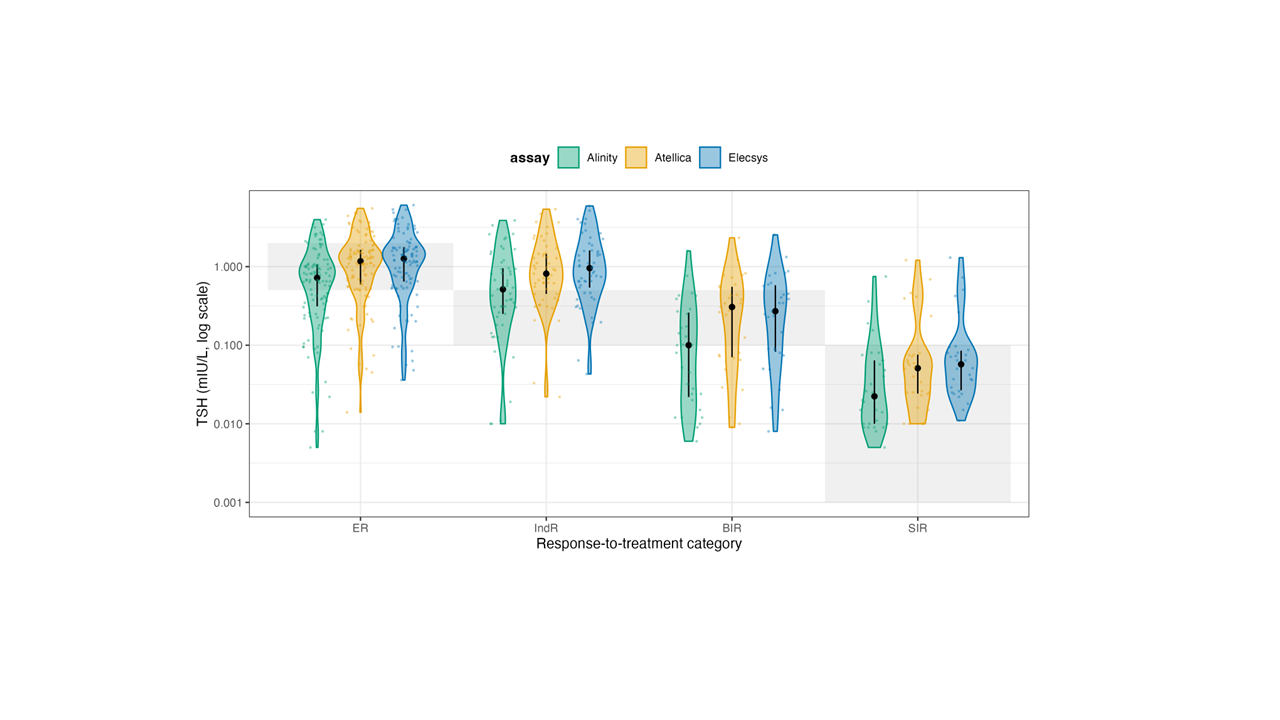

Figure 3).

For readability, the shaded horizontal bands reflect the fixed-ATA 2015 target ranges for each response category (ER 0.5-2.0 mIU/L; IndR and BIR 0.1-0.5 mIU/L; SIR <0.1 mIU/L), whereas the ATA 2025 panel applies assay-specific reference intervals. In these violin plots, each shaded horizontal band represents the guideline-recommended TSH range for that specific response category, and the assay-specific TSH distributions (Elecsys, Atellica, Alinity) are overlaid together with the median and interquartile range. These plots make the clinical pattern visually obvious: ER patients often remain below their recommended range (i.e., they are still being aggressively suppressed when guidelines would allow relaxation), IndR and BIR patients frequently sit above their recommended range (i.e., are relatively under-suppressed), and SIR patients cluster tightly in the <0.1 mIU/L region, indicating that clinicians maintain high-intensity suppression primarily in those with clear structural disease. Taken together, these data show two key points. First, Elecsys, Atellica, and Alinity exhibit only modest proportional differences and small absolute biases, supporting their practical interchangeability for TSH monitoring in DTC. Second, when the ATA 2025 assay-specific targets are applied, part of the apparent overtreatment seen under fixed cut-offs is reconciled in ER/IndR, whereas a clinically relevant gap persists in BIR with TSH remaining above the intended suppression zone in a non-trivial subset of patients. More importantly, the large variability in TSH values relative to guideline targets is driven predominantly by prescribing behavior rather than analytical performance. In current practice, many Excellent Responders remain more suppressed than necessary, whereas patients with only indeterminate or biochemical evidence of residual disease are often less suppressed than recommended. Applying a response-adapted framework consistent with ATA 2025 reclassifies a substantial proportion of this “non-adherence” in Excellent Responders as acceptable individualized de-escalation, but still reveals a clinically relevant gap in TSH suppression among patients without a clearly Excellent Response.

4. Discussion

The present analysis highlights the persistent gap between guideline-recommended and real-world TSH management in patients with DTC [

7]. Although the 2015 ATA guidelines proposed distinct TSH suppression targets according to recurrence risk and response to therapy, multiple observational studies and registry-based data indicate that these goals are inconsistently achieved in clinical practice. This variability reflects both physician-driven decisions—often balancing oncologic safety with comorbidity risk—and analytical differences between TSH assays that complicate the uniform application of targets. Additionally, recent evidence challenges the long-standing assumption that deep TSH suppression (≤ 0.1 mIU/L) uniformly improves prognosis [

8]. A large multicenter cohort and meta-analyses demonstrate that, among low- and intermediate-risk patients, maintaining TSH within or moderately below the reference range does not increase the risk of recurrence or mortality [

9]. Conversely, persistent suppression below the physiological range has been associated with a higher incidence of atrial fibrillation, bone mineral loss, and impaired quality of life [

10]. These findings reinforce the rationale for the 2025 ATA guideline update, which redefines TSH goals relative to the assay-specific reference range rather than absolute fixed cut-offs. In this context, our comparison of three widely used immunoassay platforms—Elecsys, Atellica, and Alinity—demonstrated a very high degree of analytical alignment, with minimal systematic bias and strong correlation across the clinically relevant TSH range. Our results perfectly align with those recently reported by Ursem and colleagues. They compared Elecsys, Alinity, and Atellica assays in the low TSH range (<0.4 mIU/L) and reported minor imprecision (1-14%) with negligible clinical impact [

11]. This concordance supports the reliability of cross-platform monitoring in most clinical scenarios and suggests that assay variability may be less influential than previously assumed when high-quality, standardized platforms are used. In turn, the good agreement between assays reflects the improvement of TSH assays comparability due to the use of traceable commutable reference materials and calibration traceability as proposed by the International Federation of Clinical Chemistry (IFCC)-Working Group for Standardization of Thyroid Function Tests [

12,

13]. Nevertheless, small differences near the lower reference limit may still impact clinical interpretation in patients requiring tight TSH control, underscoring the importance of maintaining awareness of platform-related nuances. The shift from absolute numerical thresholds to reference-based targets represents an important conceptual advance. It acknowledges both residual inter-assay variability and the need for patient-specific interpretation of biochemical data. Future strategies should emphasize assay harmonization, individualized monitoring, and dynamic risk-adapted titration. Laboratories and clinicians should consistently report TSH values together with their reference ranges and ensure internal traceability to international standards. Clinically, suppression intensity should be reassessed over time according to evolving disease status. For patients with an excellent or indeterminate response, maintaining TSH within the normal range appears both safe and desirable. In contrast, suppression below the reference limit may remain appropriate for biochemical or structural incomplete responses. Prospective multicentric studies integrating biochemical and clinical parameters are warranted to validate this more flexible, response-driven approach.

5. Conclusions

In summary, our findings confirm that TSH values in patients treated for DTC are generally consistent across modern immunoassay platforms, supporting reliable biochemical follow-up. However, real-world TSH levels often deviate from traditional suppression targets, reflecting an evolving balance between oncologic control and the prevention of iatrogenic harm. The updated 2025 ATA guidelines acknowledge these realities and shifted from fixed numerical thresholds to assay-specific ranges, providing a more flexible, physiologic framework balancing oncologic control with long-term safety. The routine integration of assay-specific reference data and dynamic risk stratification will be essential to refine the management of patients with DTC.

Author Contributions

L.G. and P.P.O. contributed to the conception or design of the work; all authors contributed to the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data; L.B. performed statistical analyses; L.G. contributed to the first draft of the paper; all authors provided critical revision of the manuscript and approved the final version.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Boards of “G. Martino” University Hospital, Messina (Italy), and Gruppo Ospedaliero Moncucco, Lugano (Switzerland).

Informed Consent Statement

The requirement for informed consent was waived due to the retrospective design using anonymized data. Moreover, all determinations were requested by specialists as part of the routine diagnostic testing. Then, the study only included the determination requested by the specialists, which was performed using three different methods on leftover serum samples. Medical decisions were taken by attending physicians according to the hospitals’ routine testing method results.

Data Availability Statement

For information on the study and data sharing, qualified researchers may contact the corresponding author, Prof. Dr. med. Luca Giovanella (luca.giovanella@moncucco.ch).

Conflicts of Interest

L.G.: received research grants and speaker fees not related to the present work from Roche Diagnostics (Switzerland). A.C., P.P.O., F.D.A., M.I., R.M.R., L.B., and A.A. declare no competing interests.

References

- Freudenthal, B.; Williams, G.R. Thyroid Stimulating Hormone Suppression in the Long-Term Follow-up of Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Clin Oncol 2017, 29, 325–328. [CrossRef]

- Biondi, B.; Cooper, D.S. Benefits of Thyrotropin Suppression versus the Risks of Adverse Effects in Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Thyroid 2010, 20, 135–146. [CrossRef]

- Rawlins, M.L.; Roberts, W.L. Performance Characteristics of Six Third-Generation Assays for Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone. Clin Chem 2004, 50, 2338–2344. [CrossRef]

- Haugen, B.R.; Alexander, E.K.; Bible, K.C.; Doherty, G.M.; Mandel, S.J.; Nikiforov, Y.E.; Pacini, F.; Randolph, G.W.; Sawka, A.M.; Schlumberger, M.; et al. 2015 American Thyroid Association Management Guidelines for Adult Patients with Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer: The American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Thyroid 2016, 26, 1–133. [CrossRef]

- Gubbi, S.; Al-Jundi, M.; Foerster, P.; Cardenas, S.; Butera, G.; Auh, S.; Wright, E.C.; Klubo-Gwiezdzinska, J. The Effect of Thyrotropin Suppression on Survival Outcomes in Patients with Differentiated Thyroid Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Thyroid 2024, 34, 674–686. [CrossRef]

- Ringel, M.D.; Sosa, J.A.; Baloch, Z.; Bischoff, L.; Bloom, G.; Brent, G.A.; Brock, P.L.; Chou, R.; Flavell, R.R.; Goldner, W.; et al. 2025 American Thyroid Association Management Guidelines for Adult Patients with Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. [CrossRef]

- Papaleontiou, M.; Chen, D.W.; Banerjee, M.; Reyes-Gastelum, D.; Hamilton, A.S.; Ward, K.C.; Haymart, M.R. Thyrotropin Suppression for Papillary Thyroid Cancer: A Physician Survey Study. Thyroid 2021, 31, 1383–1390. [CrossRef]

- Thewjitcharoen, Y.; Chatchomchuan, W.; Wanothayaroj, E.; Butadej, S.; Nakasatien, S.; Krittiyawong, S.; Rajatanavin, R.; Himathongkam, T. Clinical Inertia in Thyrotropin Suppressive Therapy for Low-Risk Differentiated Thyroid Cancer: A Real-World Experience at an Endocrine Center in Bangkok. Medicine (United States) 2024, 103. [CrossRef]

- Qiang, J.K.; Sutradhar, R.; Everett, K.; Eskander, A.; Lega, I.C.; Zahedi, A.; Lipscombe, L. Association Between Serum Thyrotropin and Cancer Recurrence in Differentiated Thyroid Cancer: A Population-Based Retrospective Cohort Study. Thyroid 2025, 35, 208–215. [CrossRef]

- Haymart, M.R.; Esfandiari, N.H.; Stang, M.T.; Sosa, J.A. Controversies in the Management of Low-Risk Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Endocr Rev 2017, 38, 351–378. [CrossRef]

- Ursem, S.R.; Boelen, A.; Hillebrand, J.J.; den Elzen, W.P.J.; Heijboer, A.C. How Low Can We (Reliably) Go? A Method Comparison of Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone Assays with a Focus on Low Concentrations. Eur Thyroid J 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Thienpont, L.M.; Van Uytfanghe, K.; De Grande, L.A.C.; Reynders, D.; Das, B.; Faix, J.D.; MacKenzie, F.; Decallonne, B.; Hishinuma, A.; Lapauw, B.; et al. Harmonization of Serum Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone Measurements Paves the Way for the Adoption of a More Uniform Reference Interval. Clin Chem 2017, 63, 1248–1260. [CrossRef]

- Cowper, B.; Lyle, A.N.; Vesper, H.W.; Van Uytfanghe, K.; Burns, C. Standardisation and Harmonisation of Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone Measurements: Historical, Current, and Future Perspectives. Clin Chem Lab Med 2024, 62, 824–829. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).