1. Introduction

HF remains a highly prevalent disease, carrying a substantial risk of morbidity and mortality. The estimated overall incidence and prevalence of HF according to the HFA atlas developed by the European Society of Cardiology was 1 to 4 cases per 1000 persons-years and 10 to 30 cases per 1000 persons, accordingly[

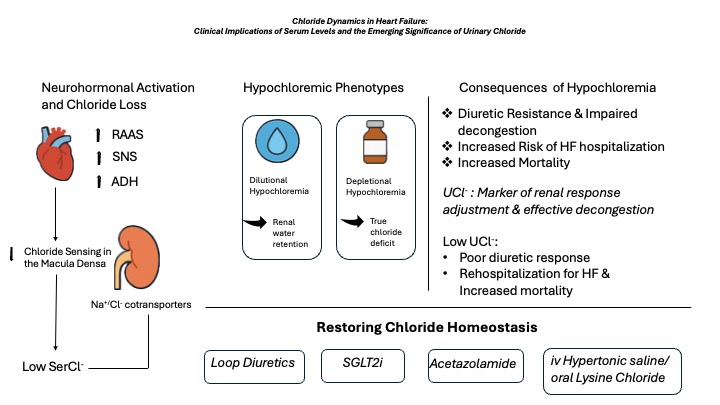

1]. Dysregulation of crucial neurohormonal systems as HF progresses leads to both limitation of free water clearance with subsequent dilution and depletion of important electolytes such as sodium and chloride. Electrolyte disturbances remain a commonly encountered and continuously investigated abnormality in HF era. Clinical significance of hyponatremia has been the major focus of research for decades, being associated with adverse outcomes and increased mortality in HF. Sodium’s anionic counterpart, chloride has recently emerged as a potential treatment target given its significant value for predicting adverse outcomes [

2,

3,

4]. The singularity in chloride lies in the fact that fluctuation in its levels reflect the combination of maladaptive neurohormonal, renal and acid-base disturbances. Interestingly, several HF studies have established serum chloride to be a more accurate predictor of adverse outcomes than sodium [

5]. Apart from mortality, hypochloremia has been associated with an increased risk of HF hospitalization as well as poor diuretic efficiency and unsuccessful decongestion[

6,

7].

The purpose of this review is to summarize current evidence concerning serum chloride while an emphasis on more specific aspects of hypochloremia has been given such as the sodium-chloride interplay, the impact of acute vs chronic chloride disturbances and temporary vs persistent hypochloremia on survival as well as the role of hypochloremia across HF spectrum [HF with preserved and reduced ejection fraction. Practical and easy to implement in clinical setting flowcharts for classification and management of hypochloremia according to the underlying mechanism will be provided. A special section for the role of urinary chloride and its interpretation in the HF context is also included.

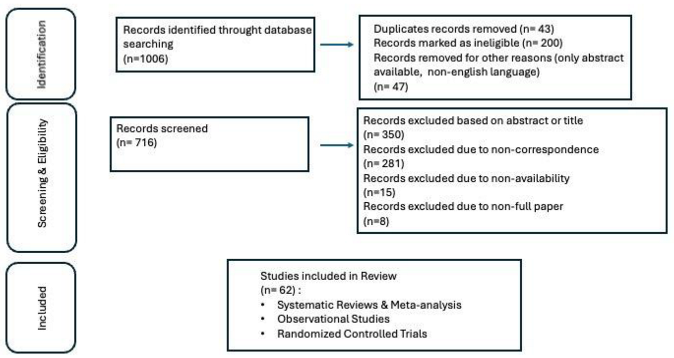

2. Literature Review Methodology

To inform this narrative review, a broad literature search was carried out using PubMed through June 2025. The search was limited to English-language publications, with no restrictions on publication date. Relevant studies were identified using a set of predefined keywords and their combinations.

Keywords were selected for their relevance to chloride disturbances in heart failure and cardiorenal syndrome. Additional studies were identified by screening references of key articles and reviews, with priority given to original research, large cohorts, meta-analyses, and clinical trials. References were managed using Zotero v6.0 (George Mason University, Fairfax, VA, USA).

3. Hypochloremia Across the Spectrum of Heart Failure

The incidence of hypochloremia has been estimated to be up to 17% in AHF registries, ranging from 13-21%, based on a recent meta-analysis[

8]. Numerous studies have demonstrated the strong and sodium-independent association existing between hypochloremia and mortality both in the setting of acute and chronic HF. Lower baseline chloride levels have also been related to poor diuretic response and impaired decongestion. According to a study by Maaten et al., based on the population of the PROTECT trial (Placebo-controlled Randomized Study of the Selective A1 antagonist Rolofylline for Patients Hospitalized with Acute Decompensated Heart Failure and Volume Overload to Assess Treatment Effect on Congestion and Renal Function), lower chloride concentration on admission was related to less weight loss with need for higher diuretic doses and adjuvant use of thiazide diuretics, smaller percentage change in NT-proBNP levels compared to baseline values and greater need for inotropes therapy. Also, hypochloremic patients presented an impaired response in reduction of intravascular volume (based on percentage of hemoconcentration achieved during hospitalization). The association of chloride with diuretic response remained significant even after adjustment for sodium and bicarbonate levels [

9]. Similarly, admission chloride was inversely and independently associated with mortality with every unit increase in its levels associated with a 6% improvement in survival by 6%, based on another study including patients with systolic dysfunction hospitalized for ADHF [

4].

According to the findings of a study by Grodin et al., enrolling patients undergoing elective diagnostic coronary angiography with stable heart failure, hypochloremia was associated with an increase in 5-year mortality risk. Among sex, comorbidities such as diabetes, CAD, HFpEF or HFrEF and impaired renal function [eGFR≤ 60ml/min], only diuretic usage seemed to interfere significantly with the hypochloremia-risk association [

10]. The strong association of serum chloride with prognosis in HF was shown in a study conducted in a Chinese cohort [

11]. Patients belonging to the lowest chloride quartile (chloride ≤ 101.2 mmol/L) presented a more adverse profile with lower values of LVEF, lower sodium and albumin levels and higher values of NT-proBNP, total bilirubin, urea, uric acid and inflammatory markers such as hs-CRP.

Based on the above published data, hypochloremia is associated with greater disease burden, diuretic-resistant cardiorenal disease, and increased markers of adverse prognosis (low serum albumin and potassium, metabolic alkalosis) reflecting overall an advanced disease state.

4. Clinical Significance of Hypochloremia in Patients with HF With

Preserved Ejection Fraction (HFpEF)

Most of the above findings for hypochloremia have been established in specific populations mainly including patients with HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). The clinical implications of serum chloride levels in patients with HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) were investigated in a study including participants from the TOPCAT trial (Treatment of Preserved Cardiac Function Heart Failure with an Aldosterone Antagonist Trial) [

6]. The association of hypochloremia with all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality was found to be similar with the one shown in patients with HFrEF. Severe HF symptoms (NYHA class III/IV), increased filling pressures (E/e’) estimated by echocardiography and higher loop and thiazide diuretic use were more prevalent in patients presenting with lower baseline chloride levels. As expected, higher loop diuretic doses were associated with lower chloride levels. Additional echocardiographic data were presented in a study including patients extracted from the PURSUIT HFpEF study who were hospitalized for ADHF with a HFpEF phenotype. Patients in the low chloride group (73-101mEq/L) presented with lower stroke volume index, cardiac index and lower TAPSE values. The above findings direct towards right ventricular systolic function as the main cause of hypochloremia in patients with HFpEF [

12]. A study by Wenyi Gu et al., sought to investigate the prognostic significance of hypochloremia across the three different HF phenotypes, given that LVEF remains a major determinant for prognosis in HF patients. As expected, hypochloremia was found to be an independent predictor of mortality in all three subtypes of HF. However, the coexistence of hypochloremia with low serum sodium levels was more frequent in patients with HFrEF compared to patients with HFpEF and HFmrEF, implicating that across HF spectrum the sodium-chloride correlation differs. The association of serum chloride with mortality was strong and independent for all different phenotypes of HF however there was a greater increase in mortality for each unit decrease in chloride for patients with LVEF≥ 40% compared to those with LVEF < 40% (17,3% vs 10,2%).

Based on the above, it becomes evident that distinct pathophysiologic mechanisms associated with hypochloremia dominate each HF subtype, depending on the extent of neuro-hormonal activation, the different dosing and type of therapy and the predominant dysfunction of left ventricular vs bi-ventricular dysfunction [

13].

5. Pathophysiologic Role of Hypochloremia in Heart Failure Progression

Chloride, being the main anion in plasma and extracellular fluid, holds a central role by regulating vascular refill, osmotic pressure, acid-base balance and renin secretion[

14].The role of chloride in preservation of fluid homeostasis is crucial and distinct from sodium, being implicated in important cardiac, renal and neurohormonal systems. In the context of hypochloremia, renin secretion from the juxtaglomerular apparatus is increased due to decreased chloride sensing in the macula densa which in turn triggers the tubuloglomerular feedback. This increase in circulating renin levels leads to inappropriate activation of RAAS which in turn induces increased renal sodium reabsorption and systemic congestion. Congestion state is further impaired by activation of sympathetic nervous system causing vascular contraction, further decreasing natriuresis and diuresis. Additionally, chloride is a key-regulator of sodium transport pathways located in the loop of Henle and distal convoluted tubule. Serine-threonine kinases-WNK (with-no-lysine protein kinases) are also known as chloride-sensing kinases detecting changes in chloride concentration, intracellular volume and plasma osmolarity. Hypochloremia triggers the upregulation of WNK kinases leading to increased activity of Na-K-2Cl

- co-transporter and Na-Cl

- symporters in the thick ascending limb of the loop of Henle and in the distal convoluted tubule accordingly thus facilitating chloride and sodium reabsorption [

15,

16]. Diuretic resistance is also a primary mechanism via which hypochloremia perpetuates congestion. A simple explanation for this is the ability of chloride to bind specifically to the catalytic site of WNK kinases affecting their ability to phosphorylate sodium-regulatory pathways. Therefore hypochloremia competes the primary mechanism of action of loop and thiazide diuretic agents[

17]. In fact, according to the results of the Renal Optimization Strategies Evaluation in Acute Heart Failure [ROSE-AHF trial], lower baseline Cl levels were associated with lower diuretic efficiency and higher in-hospital intravenous furosemide dose, independent of sodium levels, bicarbonate and Cystatin-C. Chloride-depletion alkalosis, a common acid-base abnormality in heart failure, is also considered to further impair diuretic resistance. The etiology for this lies in the fact that insufficient chloride leads to decreased excretion of bicarbonate in the lumen from pendrin a luminal Cl

-/HCO3

- exchanger located in the apical membrane of the collecting duct[

18].

6. Mechanisms Linking HF to Hypochloremia

Hypochloremia along with hyponatremia is a frequently encountered electrolyte disturbance in HF occurring in the context of volume overload due to chloride depletion. Increased water reabsorption is a key pathophysiologic mechanism in HF resulting from increased non-osmotic release of arginine vasopressin, leading to dilution-induced hypochloremia. The other potent mechanism causing depletional hypochloremia is the diuretic-mediated chloride loss which leads to much greater relative wasting of chloride compared to sodium as well as enhanced neuro-hormonal response creating thus a vicious cycle [

2]. Indeed, loop diuretic agents can increase chloride excretion up to 20 times. Loop diuretics mainly act in the thick ascending limb of Henle by inhibition of Na-K-Cl cotransporters. Contrary to sodium, which is reabsorbed more distally down the nephron, chloride reabsorption is less possible as we move more distally to the nephron, resulting in a higher incidence of hypochloremia compared to hyponatremia.

Recently, the pattern of change of urinary chloride and the association of urinary chloride/sodium during decongestive therapy has gained considerable interest as potential marker of diuretic response and it will be discussed in detail below. Although the theory of restriction of dietary salt intake is a common practice in HF patients, recent studies imply its potential adverse impact. Electrolyte disturbances mainly hyponatremia and hypochloremia provoked by rigorous sodium restriction induce neuro-hormonal activation and thus further evoke HF progression [

16,

19]. Increasing sodium intake in ADHF patients may be even beneficial provided that a negative sodium balance is achieved via diuresis [

20]. Interestingly, researchers have shown that the combination of hypertonic saline with high-dose loop diuretics resulted in greater natriuresis and diuresis compared to high-dose loop diuretics alone [

21,

22]

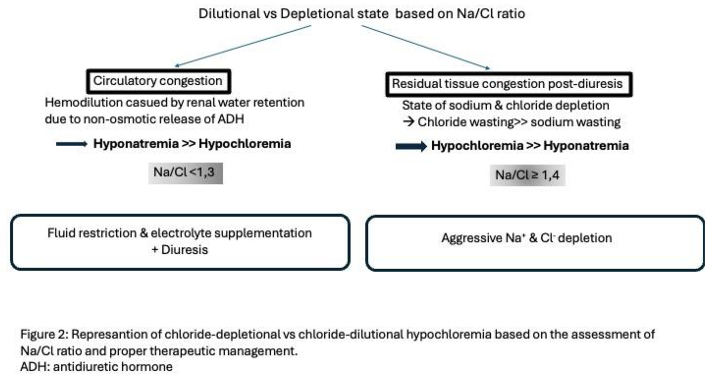

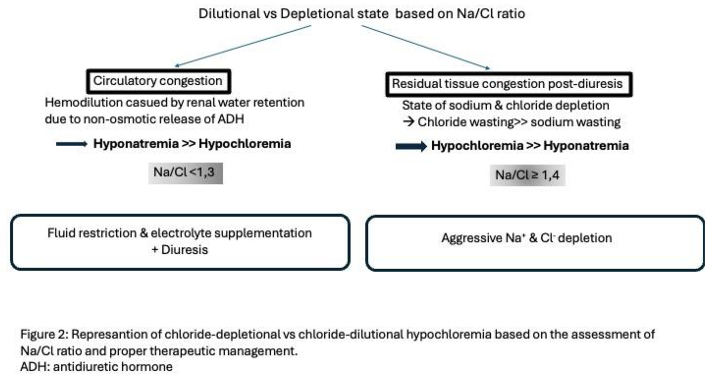

There seems to be two distinct pathophysiological patterns of hypochloremia based on the underlying mechanism: dilutional vs depletional. In the first scenario, serum chloride concentration is decreased due to reduced chloride delivery to the macula densa resulting in renin secretion from the juxtaglomerular apparatus. Vasopressin and sympathetic nervous system are activated leading to renal vasoconstriction and decrease in renal blood flow. Also, the regulation of key sodium transporters in the distal tubule by with-no-lysine kinases [WNK] is lost because of hypochloremia which leads to their overactivation promoting further sodium reabsorption. The above processes lead to impaired aortic filling and HF progression. In this context, hypochloremia and hyponatremia coexist with hemodilution being the main contributor. Fluid restriction, electrolyte supplementation and use of potassium-sparing diuretics such as mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists are appropriate strategies in this case. In the second scenario, hypochloremia coexists with normal serum sodium levels and commonly with metabolic alkalosis while the main driving mechanism is true chloride deficit. The depleted phenotype is partly attributed to diuretic-induced chloride loss. The main strategy for this phenotype is aggressive repletion of electrolytes [

16,

23,

24].

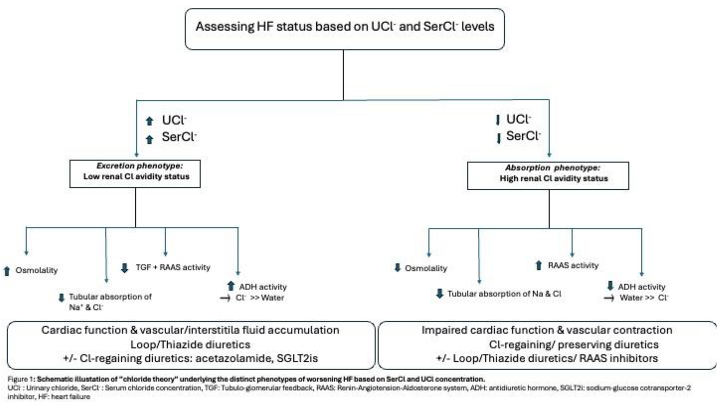

7. The Chloride Theory

The central idea of this theory is that serum chloride concentration modulates renal water retention, vascular volume and aortic filling through its direct effect on sympathetic nervous system, RAAS system, ADH secretion and vasodilatory-natriuretic pathways. Chloride is a key-electrolyte of fluid distribution and fluid movement between intracellular and intravascular space during worsening HF [

25]. Research has shed further light on this chloride-based theory by demonstrating that serum chloride concentration has a direct impact on alterations of the vascular volume, independently of serum sodium concentration[

26,

27] and also that chloride is a critical regulator of renal sodium reabsorption thus being implicated in the modulation of arterial pressure [

28].

Based on the chloride accumulation pattern in relation to water retention, two distinct phenotypes under acute HF status exist: the excretion phenotype/ low renal Cl- avidity versus the absorption phenotype/high renal Cl- avidity. In the excretion phenotype, cardiac function is preserved, and patient can maintain an effective arterial blood volume leading subsequently to decreased RAAS activation. Vascular space is overloaded with electrolytes (mainly Na+ and Cl-) and water being excreted to the urinary tract due to low RAAS activity. However, there is insufficient movement of excess water and electrolytes from the vascular and interstitial space therefore favoring excess body fluid retention. Serum osmolality is maintained in this scenario leading to decreased secretion of ADH and inhibition of tubuloglomerular feedback. On the contrast, the absorption phenotype reflects a more serious HF state with vascular contraction, excess fluid accumulation into the interstitial space, impaired renal function and increased cardiac burden. In this clinical scenario, chloride concentration reaching the renal tubules is inadequate resulting in decreased absorption of renal sodium and subsequently reduced plasma volume. In addition, increases RAAS activity occurs due to decreased chloride reaching the macula densa. However, the increase in neurohormonal activation is not sufficient to increase reabsorption of electrolytes as their supply in the renal tubules is markedly decreased. In the excretion phenotype the optimal therapeutic strategy is the use of Cl-depleting loop/thiazide diuretics in parallel with Cl-preserving diuretics such as SGLT2i and acetazolamide. In the case of low urinary chloride, increased RAAS activity and relative resistance to conventional loop/thiazide diuretic therapy is expected. So, in the absorption phenotype, Cl-regaining diuretics in combination with Cl-depleting diuretics as well as the use of RAAS blockers would favor vascular volume restoration and transfer of excess fluid from the interstitial into the vascular space [Figure 1].

During decongestive therapy of worsening HF serum chloride concentration has a central pathophysiologic role. Interventions to reduce or increase serum chloride concentration based on baseline levels will have a direct therapeutic effect on plasma volume and vascular tone regulation, on renal water and electrolyte handling and on RAAS and ADH systems.

8. Hypochloremia and its Contribution to Diuretic Resistance

Diuretic resistance is defined as a dissatisfying rate of natriuresis and diuresis despite escalating dose of diuretic therapy. Yet its definition remains subjective and problematic to measure in clinical practice.

Mechanisms of diuretic resistance are complex and are both extra-tubular and tubular with the latter being the primary driver of poor diuretic response. Distal nephron sodium reabsorption significantly contributes to the development of diuretic resistance. The interaction of chloride with a family of serine/threonine protein kinases, known as with-no-lysine kinases, is crucial for the function of serum/chloride (NCC) and serum/chloride/potassium (NKCC2) co-transporters (located in the thick ascending Henle’s loop and the distal convoluted tubule accordingly). Hypochloremia results in un-regulation of these transporters via activation of WNK kinases resulting in activation of channels that are pharmacologically inhibited by diuretics, thus leading to diuretic resistance. Another possible mechanism linking hypochloremia and hypochloremic alkalosis with worse diuretic response may be explained by their effect on distal tubular sodium handling. Metabolic alkalosis is a known contributor to diuretic resistance. Pendrin is a luminal exchanger located in the collecting duct modulating bicarbonate excretion in parallel with chloride reabsorption. In the presence of chloride depletion, there is insufficient substrate on the tubular lumen for pendrin to exchange with bicarbonate. Therefore contraction alkalosis is maintained further decreasing diuretic efficacy [

2,

31,

32].

Several studies have investigated the role of hypochloremia in the genesis of diuretic resistance. A study by Hanberg et al. [

34], included two separate HF populations: one group receiving loop diuretics and another group of stable outpatients receiving standard dose of furosemide on top of lysine chloride supplementation. The primary aim of the study was to investigate whether an association existed between serum chloride levels and diuretic efficiency as well as to investigate whether chloride changing levels would have an impact on laboratory and clinical parameters. Among the first group, patients with hypochloremia were under treatment with higher standard loop diuretic dose and use of adjuvant therapy with thiazide diuretics compared with those with normal chloride levels. A modest association was also found between serum chloride and diuretic efficiency (defined as the increase in serum sodium output per doubling of loop diuretic dose, with a reference dose of 40mg of intravenous furosemide equivalents) with the odds of low diuretic efficiency being substantially high in patients with hypochloremia, even after adjustment for serum sodium and bicarbonate levels. In addition to that, the relative excretion of diuretic and the total quantity of diuretic in urine were both decreased in hypochloremic patients implicating reduced diuretic tubular delivery and impaired tubular response to the amount of diuretic delivered as primary mechanisms of diuretic resistance. Similar findings from numerous studies have confirmed the association of hypochloremia with markers of poor decongestion such as less weight change and lower improvement in intravascular volume as estimated by percentage of hemoconcentration achieved [

35].

9. Special Issues to be Considered In Hypochloremia Management

9.1. Serum Chloride Alterations in AHF Decongestion and Clinical Prognosis

Although the association of hypochloremia with worse clinical outcomes is known, we have little knowledge concerning the impact of timing and duration of hypochloremia on prognosis of AHF patients.

A retrospective study by Kurashima et al.[

36], including 2798 patients admitted for AHF, sought to investigate the effect of change in serum chloride levels during decongestion therapy. For this purpose, population was divided into 4 separate groups: patients with normochloremia (≥98 mEq/L) during the investigation period, patients developing hypochloremia throughout treatment (normochloremia on presentation with following decrease in serum chloride levels <98 mEq/L), those with transient hypochloremia present on admission but disappearing at discharge and persistent hypochloremia existing both on admission and on discharge. In total, most patients (78%) presented with hypochloremia, 12% with treatment-induced hypochloremia, 5% with resolved hypochloremia and the rest 5% with persistent hypochloremia. Interestingly the presence of constant hypochloremia was associated with more severe dyspnoea on discharge (estimated by NYHA class), lower levels of systolic blood pressure (SBP), more frequent use of diuretics and lower serum sodium levels both at admission and discharge. Also, discharge only BNP levels were found to be significantly higher in the persistent hypochloremia group. When associating hypochloremia status with primary (all-cause death) and secondary outcomes (cardiovascular death and combined outcome of cardiovascular death and rehospitalization for HF), persistent hypochloremia had a statistically significant with both outcomes. Apparently, patients presenting with resolved hypochloremia had a similar favorable prognosis to those patients presenting with normal chloride levels. However, patients presenting with evolving hypochloremia presenting during diuretic therapy, had better prognosis compared to those with persistent hypochloremia but worse outcomes compared to those with resolved hypochloremia or normochloremia. The above observations highlight the possible prognostic significance of improved hypochloremia at discharge being a marker of favorable outcomes. Another similar retrospective study by Maaten et al.[

37], including a cohort of patients from the PROTECT study (Placebo-controlled Randomized study of the Selective A1 antagonist Rolofylline for Patients Hospitalized with Acute Decompensated Heart Failure and Volume Overload to Assess Treatment Effect on Congestion and Renal Function) [

38] aimed to investigate the presence of association between changing chloride levels and diuretic efficiency, decongestion and mortality. Low chloride levels measured at day 7 and at day 14 were both associated with a higher risk of mortality whereas admission chloride levels were no longer predictive of mortality after adjustment for baseline sodium levels. Interestingly a decrease in chloride levels observed either on day 7 or on day 14 was associated with an increased risk of mortality. A similar significant extent of increase in the mortality rate was observed in patients presenting with persistent hypochloremia. Similarly with the findings of the previous study of Kurashima et al., patients with resolved hypochloremia and patients with normochloremia exhibited similar prognosis. Moreover, the association of admission hypochloremia with adverse outcomes was attenuated after correction for chloride levels achieved in subsequent measurements [ie. Day 7 or day 14], implicating that the final chloride measurement portends stronger prognostic significance than the change observed itself. The above observations highlight new aspects in chloride evaluation implicating that the time point at which hypochloremia occurs has probably a greater prognostic significance than the presence of hypochloremia itself.

9.2. Sodium and Chloride: A Linked Electrolyte Axis:

Numerous studies have found a well-established and strong association of hyponatremia with increased mortality risk in chronic and acutely decompensated heart failure[

39,

40,

41]. However, therapeutic strategies aiming to increase serum sodium levels such as vasopressin antagonists did not have a significant impact on outcomes as shown by the TACTICS-HF (Targeting Acute Congestion with Tolvaptan in Congestive Heart Failure) study [

42]. On the other hand, chloride known as the anion counterpart of sodium in salt, is an emerging predictor of adverse outcomes in heart failure. Hypochloremia frequently presents with concomitant hyponatremia, probably reflecting a more serious homeostatic impairment. Given that sodium and chloride both are subject to kidney metabolism, it is likely that they carry relevant information [

43].

Therefore, it is of paramount importance, to clarify whether these two electrolytes have a different and independent role from one another before considering hypochloremia as a separate treatment target.

A Chinese study by Zhang et al.[

44], aimed to investigate the prognostic significance for all-cause mortality of serum chloride in patients with chronic heart failure. According to the results, serum chloride levels were independently and inversely associated with mortality both in the univariate association and after multivariable adjustment for age, sex, LVEF, loop diuretic use, eGFR and NT-proBNP. However, when sodium was added to the adjustment, the relation of chloride with mortality no longer existed. When the cohort of patients was divided into separate groups based on median concentration of serum sodium and chloride, Kaplan-Meier survival curves showed the worst survival for the group with the lower sodium and chloride concentration whereas the patient group with high serum sodium but low serum chloride had a better survival but still a worse prognosis as compared to the group with low serum sodium and high chloride levels (HR for mortality: 4.334, 1.624, 1.166 accordingly). Moreover, the Na/Cl ratio was also calculated, and survival curves were analyzed across Na/Cl quartiles. Those patients with the higher Na/Cl ratio had the higher mortality rate. The above findings point towards the hypothesis that the prognostic role of chloride is probably affected by sodium concentration, implicating that hypochloremia can serve as an additive prognostic marker of sodium for mortality. Felker et al., studied symptomatic patients with chronic heart failure to identify novel laboratory markers associated with all-cause mortality in HF. Among them, serum chloride was found to be statistically stronger parameter of all cause-mortality, when compared to sodium, in a multivariable model [

45].

On the opposite, Grodin et al. [

4],investigating the prognostic role of chloride in patients hospitalized for ADHF, showed an inverse association for serum chloride and sodium with mortality. However, chloride levels on admission showed a greater discrimination for mortality as compared to sodium and when chloride values were added to the multivariable adjustment, serum sodium was no longer associated with mortality. Also, Kaplan-Meier survival curves classified by levels of chloride and sodium demonstrated the lowest survival rate when both chloride and sodium were low (<96mEq/L and <134mEq/L accordingly) with the second worst survival rate for those patients with hypochloremia (<96mEq/L) but with normal serum sodium levels (≥ 134mEq/L). Similar findings were described by another study carried out in stable chronic heart failure patients [

46].

In the context of HF, the relative concentrations of sodium and chloride can be lowered symmetrically or asymmetrically. This Na/Cl relation may have diagnostic utility in HF therapy. A study by Zhiqing et al. [

47], sought to evaluate the clinical utility of the above ratio in patients with acute heart failure and its possible association with mortality. It was a single-center retrospective study enrolling 2,008 patients admitted for acute HF with the primary outcome being all cause mortality at 3 months after discharge. Three patient groups were analyzed according to Na/Cl ratio values (<1,3, 1,3-1,4 and ≥1,4) with the values between 1,3-1,4 used as the reference group. Patients with a ratio below 1,3 and above or equal to 1,4 had the highest adjusted HR for mortality (3.58 and 2.66 accordingly) with the value of 1,34 carrying the lowest mortality risk. Also, Na/Cl ratio when associated with 3-months mortality created a U-shaped curve. The significant association found between Na/Cl and mortality was independent of age, sex, LVEF, absence or presence of hyponatremia or hypochloremia. The use of Na/Cl ratio can help categorize patients in distinct risk groups and therefore customize decongestive strategies. When Na/Cl ratio is low (ie. <1,3), hyponatremia is more frequent pointing towards circulatory congestion and dilution as an etiology of electrolyte disturbance. When Na/Cl ratio is high (ie. ≥1,4) hypochloremia is present implicating that there is residual tissue congestion after aggressive diuresis which in turn led to electrolyte depletion. So in the first case, the appropriate strategy is fluid restriction combined with electrolyte supplementation, whereas in the second case therapy includes intense chloride and sodium supplementation which will restore plasma osmotic pressure and thus improve tissue congestion

[Figure 2].

Chloride seems to have a stronger prognostic role as a marker of risk. Although hypochloremia is equally prevalent in HF patients, it only partially overlaps with hyponatremia. As explained by chloride’s unique pathophysiological role, hypochloremia may enlighten different mechanistic pathways explaining its stronger prognostic significance [

48]. However, the two electrolytes should always be interpreted in parallel, and their ratio should be taken into account. It is evident that patients presenting with both hypochloremia and hyponatremia are in increased mortality risk as compared to those with normal electrolytes. In the setting of low serum chloride, serum sodium value should also be considered. If it is within normal range or even increased, this translates as a state effective decongestion.

9.3. Pathophysiologic Role of Bicarbonate in Hypochloremia

Bicarbonate is the most abundant anion in human body after chloride. Its main role is to maintain acid-base balance and charge balance, correlated negatively with chloride. This inverse relation between chloride and bicarbonate is actually beneficial, helping in maintaining cation-anion balance [

14]. Metabolic alkalosis is a very common electrolyte disturbance in the context of HF. The activation of sympathetic nervous system and renin-angiotensis-aldosterone system leads to an increase in noradrenaline and aldosterone levels which subsequently result in enhanced reabsorption of bicarbonate in the proximal convoluted tubule. Meanwhile, aldosterone activates the H

+ -ATPase pump in the collecting duct, thus increasing the H

+ concentration in urine, resulting in a positive balance of bicarbonate.

Patients are entrapped in a vicious cycle of metabolic alkalosis and hypochloremia, attributed mainly to the HF pathophysiology but also to the use of loop diuretics. Given its significant association with serum chloride, it is possible that the effect of chloride in HF prognosis may be partly influenced by serum bicarbonate concentration. Moreover the presence of hypochloremia occurring due to either increased bicarbonate absorption or to aggressive diuresis, further sustains alkalosis as there is less chloride in the urine to be exchanged with bicarbonate. The above further contributes to diuretic resistance associated with pendrin a luminal Cl-/HCO3 – exchanger in the collecting duct.

A study by Zhaochong et al.[

49], investigated the presence and the degree of impact of serum bicarbonate levels in the association of hypochloremia with in-hospital mortality. Patients admitted to the intensive care unit [ICU] with a principal diagnosis of HF were included in this study. Patient’s laboratory parameters were divided based on serum chloride and bicarbonate levels into three groups for different levels of each electrolyte: hypochloremia[<96mEq/L], normochloremia (96-108mEq/L), hyperchloremia (>108mEq/L) and low bicarbonate (<22mEq/L), medium bicarbonate (22-26mEq/L) and high bicarbonate (>26mEq/L). Based on the results patients with hypochloremia tended to have higher bicarbonate levels and an inverse correlation was found between serum chloride and serum bicarbonate, (R= -0,334), as expected. In association with serum bicarbonate groups, serum chloride was linearly associated with in-hospital mortality only when bicarbonate levels were in the low and medium range. Therefore, increasing serum chloride levels in the above patient groups resulted in a decrease in in-hospital mortality. However, when bicarbonate levels were high, hyperchloremia was not a predictor for in-hospital-mortality. Interestingly, when the prognostic risk of HF patients with hypochloremia was analyzed according to different bicarbonate concentrations, the in-hospital mortality was found to be greater in those patients having hypochloremia accompanied by low serum bicarbonate levels. The latter finding confirms the rule that chloride needs to be inversely related to bicarbonate to maintain cation-anion balance. When these two electrolytes increase or decrease simultaneously the prognosis of the patient becomes poor.

On the contrary, alkalosis may have a prognostic role when occurring in the context of effective diuresis by being a prognostic indicator of improved volume status and therefore useful in clinical practice. Khan et al.,[

50] sought to investigate the prognostic role of chloride associated depletion alkalosis in acute decompensated heart failure. Population of interest was divided into two categories based on the change of serum bicarbonate values on admission and on discharge. A change of ≥ 3mmol/L in serum bicarbonate levels was defined as contraction depletion alkalosis (CDA). The primary endpoints of the study were in-hospital mortality as well as all-cause mortality in 30 days and need for hospital readmission. In-hospital mortality was significantly higher in the group without CDA whereas no statistically significant difference concerning the other endpoints of the trial between the two groups. Also, the group that developed CDA presented also a slight improvement in serum creatinine. CDA reflects a state of decreased volume due to effective decongestion. Therefore, it may be useful in conjunction with other parameters as a marker of favorable prognosis and adequate diuresis.

10. Urinary Chloride: A Marker and Tool in Heart Failure Management

The accurate assessment of fluid overload and the implementation of adequate diuretic therapy in acute heart failure have been the main interest for many years. However, research has now focused not only on the total urine volume as a marker of successful decongestion but also on urine composition analysis to estimate therapy response and overall outcome. Low urinary sodium has been recently identified as a marker of poor diuretic response and increased mortality in acute heart failure [

51,

52,

53]. Based on chloride’s pathophysiological significance in renal salt sensing, in the tubuloglomerular feedback and regulation of renin secretion at the macula densa[

54], it seems reasonable to investigate the potential utility of urinary chloride in determination of prognosis, as a marker of renal response adjustment and diuresis in acute and chronic heart failure.

Under this prospect, a Polish study [

55] aimed to record the trajectory of urinary sodium and chloride in 50 patients with ADHF undergoing intensive diuretic treatment. Both urinary chloride (UCl) and sodium levels (UNa) reached their peak values simultaneously, that is two hours after implementation of intravenous diuretic therapy. UCl excretion at this timepoint and at all subsequent timepoints was significantly higher compared to UNa concentration. Additionally, a strong linear correlation was shown between UCl and UNa at all timepoints, with its strongest value observed at 1h after diuretic administration. Moreover, a UCl< 72mmol/L was associated with greater odds for poor diuretic response compared to UNa concentration <50-70mmol/L.

Similarly another study by Nawrocka-Millward et al.[

56], enrolled patients with AHF and divided them into two separate groups of low and high UCl, based upon urinary chloride levels. The group of low UCl presented lower levels of blood pressure [systolic and diastolic], higher incidence of hypochloremia and hyponatremia and higher NT-proBNP levels at discharge. Also, creatinine and urea on admission and creatinine levels 24h after admission were statistically significant higher compared to the high UCl group. Renin and aldosterone levels were estimated on admission and on the first day of hospitalization, both being significantly increased in the low UCl group. In terms of outcomes, in-hospital mortality, need for inotropic support, worsening of HF during therapy and need for treatment in an intensive cardiac unit were all increased in the low UCl group. One-year mortality and the combined outcome of one-year mortality and rehospitalization for HF were both significantly higher in the low UCl group (HR: 2.42 and 2.20 accordingly). In a multivariable model including urinary and serum chloride levels, UCl was found to be an independent prognostic marker along with serum creatinine levels.

The achievement of normovolemia is the goal of therapy during HF decongestion as residual congestion has been associated with poor outcomes. The assessment of urinary composition during decongestive treatment combined with clinical examination and monitoring of urine output could help in reaching euvolemia. The validity of this hypothesis was examined in a study by Verbrugge et al.[

57]. Patients with HFrEF, hospitalized for an episode of acute decompensation underwent analysis of 24-hour urinary samples collected for three consecutive days during decongestive therapy with combinational diuretic therapy. While urine output remained stable during the study period (after adjustment for loop diuretic dose), urinary sodium and chloride excretion both presented a significant decline in the first 24 hours of therapy and stabilized thereafter. Interestingly, the ratio of Na

+/Cr and Cl

-/Cr were found to be predictors of negative fluid balance (urine output lower than total daily fluid intake of 1,5L). Moreover, 26% of patients developed acute kidney injury (defined as a rise in creatinine ≥ 0,3 mg/dL). Total 24-hour UNa and UCl were statistically significant lower in this patient group. Similarly, another study by Xanthopoulos et al. [

58], aimed to assess the predictive value of urinary sodium and chloride values during decongestion in acutely decompensated patients with advanced HF. UCl values were estimated at baseline, 2-hours and 24-hours after administration of diuretic therapy. 2-hours UCl value presented good discrimination with a cut-off value ≤ 99,8 meq/L having 13 times higher odds for the primary study outcome (all-cause mortality and/or HF rehospitalization) with UCl values at admission and at 24-hours having no prognostic significance. In a univariate logistic regression analysis, UNa and UCl levels at 2-hours were among those factors associated with the primary study outcome.

The appropriate combination and dosing of diuretics as well as the timely-correct down titration once euvolemia has been reached remain questionable in HF management. Urinary chloride combined with urinary sodium assessment can potentially serve as a marker of effective decongestion and no further need for up titration of diuretics. Especially when these values are corrected for urinary creatinine compared to absolute ion concentrations alone, account better for changes in renal function. Based on the above, there is accumulating evidence that urinary chloride could be implemented in everyday clinical practice, similarly to a urinary sodium-guided diuresis as a marker of response to HF treatment and as a predictor of a more advanced disease state.

11. Emerging Therapeutic Strategies in the Management of Hypochloremia and a Practical Framework for Serum and Urinary Chloride Disorders

According to the chloride theory, chloride has a key role in regulating body fluid distribution. An attractive strategy would be to use diuretics having an impact on serum chloride levels. SGLT2i are known for their natriuretic and osmotic diuretic effects leading to significant diuresis through decrease in plasma volume [

59]. However, little is known concerning their effect on serum chloride concentration. This knowledge gap was investigated by a small retrospective single-center study [

60]. Ten patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, without known history of HF, receiving therapy with empagliflozin were enrolled. Serum and urinary chloride levels were evaluated for each patient. Treatment with SGLT2i led to a statistically significant increase in serum chloride levels. This chloride-regaining effect may be attributed to several SGLT2i-associated mechanisms such as aquaresis mediated hemoconcentration, impact on RAAS activity and decrease in serum bicarbonate concentration. However, this study included a small number of diabetic, non-HF patients, therefore larger observational studies are needed to further elucidate the effect of SGLT2i on chloride handling.

Acetazolamide, is a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor which has recently gained attention as a chloride-regaining diuretic. By inhibiting carbonic anhydrase, increases bicarbonate concentration in proximal renal tubules and creates the necessary electrochemical gradient that subsequently promotes chloride reabsorption and reduces activity of the chloride/bicarbonate exchanger located at the proximal convoluted tubule. Acetazolamide enhances sodium and bicarbonate excretion and chloride reabsorption, thus preventing the development of both metabolic alkalosis and hypochloremia [

61]. The addition of acetazolamide in standard intravenous loop diuretic therapy in ADHF patients has been associated with increased odds of successful decongestion and reduced hospital stay irrespectively of baseline chloride levels, based on a post-hoc analysis of the ADVOR trial (Acetazolamide in Decompensated Heart Failure With Volume Overload). The decongestive property of acetazolamide is probably attributed to its chloride-preserving effect. Chloride-depletion can also be achieved either by administering orally lysine chloride or intravenous hypertonic saline solution. Indeed, the possible beneficial impact of intravenous administration of hypertonic saline in conjunction with loop diuretics has been shown by several studies concerning increase in urine output, sodium excretion, urine furosemide delivery and greater weight loss [

21,

62]. Sodium-free chloride supplementation with orally administered lysine chloride has been tested in a pilot study of 10 patients. The results were favorable concerning the improvement of markers of fluid overload such as serum albumin and weight loss following treatment with lysine chloride combined with loop diuretics [

34].

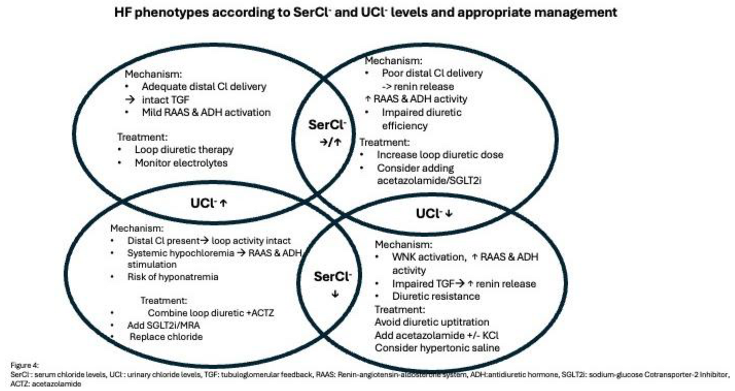

Based on serum and urinary chloride levels four distinct phenotypes of HF state exist. The underlying pathophysiology and appropriate therapeutic management are illustrated in Figure 3.

When serum chloride levels are within normal range or increased, plasma volume is maintained or even increased with a tendency for fluid accumulating into the blood vessels due to the increase in serum osmolality. Adequate chloride is being delivered ti the distal parts of the nephron. Therefore, TGF remains intact and RAAS and ADH activity are only mildly activated. The optimal strategy is to continue titration of loop diuretics and monitor electrolytes. However, in case where normochloremia with low UCl- occur, distal delivery of chloride is impaired which subsequently leads to enhanced renin release and neurohormonal activation. Loop diuretic effect is inadequate which mandates further increase in loop diuretic dose while considering also adding acetazolamide or SGLT2i.

When hypochloremia is present, vascular contraction and extravasation of ex vascular fluid into the interstitial space occurs due to decreased serum osmolality as well as decreased supply of chloride to the macula densa resulting in decreased reabsorption of filtered sodium from the tubular space towards the extracellular space and increase in RAAS activity. In addition, as a response to arterial under-filling, ADH and RAAS activity are increased leading to excess water retention relatively greater in relation to serum chloride. Despite enhanced RAAS activity, reabsorption of filtered odium and chloride is not respectively increased as their supply in the urinary tubules is itself reduced.

If hypochloremia coexists with high UCl- means that adequate chloride is present in the distal tubule. In this case therapy should focus on chloride depletion in parallel with decongestion. Thus, combination of loop diuretics with chloride-gaining diuretics such as ACTZ and SGLT2i with concomitant chloride supplementation would be advisable in this setting. If serum and urinary chloride levels are both suppressed, TGF is impaired resulting in increased renin release which further worsens diuretic resistance. In this scenario, the correction of hypochloremia is the key either by using ACTZ either by oral or intravenous administration of chloride with hypertonic saline solution or free-sodium chloride supplementation.

12. Conclusions

Maintaining electrolyte balance and reducing cardiorenal damage remain central goals in the management of heart failure. Chloride—sometimes called the “queen of electrolytes”—is the body’s main anion and plays a key role in maintaining electrical neutrality, osmotic pressure, and acid–base balance. Current evidence shows that low serum chloride levels are linked to more advanced disease state, higher diuretic use, and greater comorbidity burden. While chloride itself may not be a direct therapeutic target in HF, it can serve as a valuable tool for prognosis and clinical decision-making. For these reasons, advancing our understanding of its regulatory and homeostatic role in HF remains important.

More evidence is needed to clarify the prognostic value of serum and urinary chloride in larger, more diverse patient groups receiving modern guideline-based therapies, with outcomes measured for both survival and non-survival endpoints. The mechanisms behind hypochloremia may also hold prognostic significance and should be explored further using direct urinary electrolyte measurements. In addition, considering total cations and other major anions—particularly bicarbonate and albumin—is essential for accurately interpreting the clinical consequences of hypochloremia.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.:

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACTZ |

Acetazolamide |

| ADH |

Anti-diuretic hormone |

| ADHF |

Acute Decompensation of Heart Failure |

| AHF |

Acute Heart Failure |

| CAD |

Coronary Artery Disease |

| CDA |

Contraction Depletion Alkalosis |

| eGFR |

Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate |

| HF |

Heart Failure |

| HFmrEF |

Heart Failiure with Mildly Reduced Ejectin Fraction |

| HFpEF |

Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction |

| HFrEF |

Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction |

| hs-CRP |

High-sensitive C-reactive protein |

| LVEF |

Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction |

| NCC |

Serum/chloride co-transporters |

| NKCC2 |

Serum/chloride/potassium co-transporters |

| NT-proBNP |

NT-pro-B-type Natriuretic peptide |

| NYHA |

New-York Heart Association class |

| RAAS |

Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System |

| SBP |

Systolic Blood Pressure |

| SGLT2i |

Sodium |

| TGF |

Tubuloglomerular Feedback |

| UCl |

Urinary chloride |

| UNa |

Urinary Na |

| WNK |

With-no-lysine-kinases |

References

- Pm S, P V, Ea J, Ap M, A T, I M, et al. The Heart Failure Association Atlas: Heart Failure Epidemiology and Management Statistics 2019. Eur J Heart Fail [Internet]. 2021 June [cited 2025 July 26];23[6]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33634931/.

- Arora, N. Serum Chloride and Heart Failure. Kidney Med. 2023, 5, 100614. [CrossRef]

- Cuthbert, J.J.; Pellicori, P.; Rigby, A.; Pan, D.; Kazmi, S.; Shah, P.; Clark, A.L. Low serum chloride in patients with chronic heart failure: clinical associations and prognostic significance. Eur. J. Hear. Fail. 2018, 20, 1426–1435. [CrossRef]

- Grodin JL, Simon J, Hachamovitch R, Wu Y, Jackson G, Halkar M, et al. Prognostic Role of Serum Chloride Levels in Acute Decompensated Heart Failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015 Aug 11;66[6]:659–66. [CrossRef]

- Jm T, Js H, Jp A, Ma B, Jm TM, Fp W, et al. Hypochloraemia is strongly and independently associated with mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail [Internet]. 2016 June [cited 2025 July 26];18[6]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26763893/.

- Jl G, Jm T, A P, K S, Mh D, Jc F, et al. Perturbations in serum chloride homeostasis in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: insights from TOPCAT. Eur J Heart Fail [Internet]. 2018 Oct [cited 2025 July 26];20[10]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29893446/.

- Grodin, J.L.; Sun, J.-L.; Anstrom, K.J.; Chen, H.H.; Starling, R.C.; Testani, J.M.; Tang, W.W. Implications of Serum Chloride Homeostasis in Acute Heart Failure (from ROSE-AHF). Am. J. Cardiol. 2017, 119, 78–83. [CrossRef]

- Prognostic impact of serum chloride concentrations in acute heart failure patients: A systematic Rreview and meta-analysis - PubMed [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 20]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37379618/.

- ter Maaten, J.M.; Damman, K.; Hanberg, J.S.; Givertz, M.M.; Metra, M.; O’cOnnor, C.M.; Teerlink, J.R.; Ponikowski, P.; Cotter, G.; Davison, B.; et al. Hypochloremia, Diuretic Resistance, and Outcome in Patients With Acute Heart Failure. Circ. Hear. Fail. 2016, 9. [CrossRef]

- Jl G, Fh V, Sg E, W M, Jm T, Wh T. Importance of Abnormal Chloride Homeostasis in Stable Chronic Heart Failure. Circ Heart Fail [Internet]. 2016 Jan [cited 2025 July 27];9[1]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26721916/.

- Zhang, Y.; Peng, R.; Li, X.; Yu, J.; Chen, X.; Zhou, Z. Serum chloride as a novel marker for adding prognostic information of mortality in chronic heart failure. Clin. Chim. Acta 2018, 483, 112–118. [CrossRef]

- M S, T W, T Y, M Y, T H, A N, et al. Prognostic significance of serum chloride level in heart failure patients with preserved ejection fraction. ESC Heart Fail [Internet]. 2022 Apr [cited 2025 July 27];9[2]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35137570/.

- Gu, W.; Zhou, J.; Peng, Y.; Cai, H.; Wang, H.; Wan, W.; Li, H.; Xu, C.; Chen, L. Prognostic Significance of Serum Chloride Level Reduction in Patients with Chronic Heart Failure with Different Ejection Fractions. Int. Hear. J. 2023, 64, 700–707. [CrossRef]

- Cuthbert, J.J.; Bhandari, S.; Clark, A.L. Hypochloraemia in Patients with Heart Failure: Causes and Consequences. Cardiol. Ther. 2020, 9, 333–347. [CrossRef]

- A K, C R. Emergence of Chloride as an Overlooked Cardiorenal Connector in Heart Failure. Blood Purif [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2025 July 26];49[1–2]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31851979/.

- Zandijk, A.J.; van Norel, M.R.; Julius, F.E.; Sepehrvand, N.; Pannu, N.; McAlister, F.A.; Voors, A.A.; Ezekowitz, J.A. Chloride in Heart Failure. JACC: Hear. Fail. 2021, 9, 904–915. [CrossRef]

- Js H, V R, Jm TM, O L, Ma B, F PW, et al. Hypochloremia and Diuretic Resistance in Heart Failure: Mechanistic Insights. Circ Heart Fail [Internet]. 2016 Aug [cited 2025 July 26];9[8]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27507113/.

- Luke RG, Galla JH. It Is Chloride Depletion Alkalosis, Not Contraction Alkalosis. J Am Soc Nephrol JASN. 2012 Feb;23[2]:204. [CrossRef]

- Kataoka, H. Treatment of hypochloremia with acetazolamide in an advanced heart failure patient and importance of monitoring urinary electrolytes. J. Cardiol. Cases 2018, 17, 80–84. [CrossRef]

- Gupta D, Georgiopoulou VV, Kalogeropoulos AP, Dunbar SB, Reilly CM, Sands JM, et al. Dietary sodium intake in heart failure. Circulation. 2012 July 24;126[4]:479–85. [CrossRef]

- Licata, G.; Di Pasquale, P.; Parrinello, G.; Cardinale, A.; Scandurra, A.; Follone, G.; Argano, C.; Tuttolomondo, A.; Paterna, S. Effects of high-dose furosemide and small-volume hypertonic saline solution infusion in comparison with a high dose of furosemide as bolus in refractory congestive heart failure: Long-term effects. Am. Hear. J. 2003, 145, 459–466. [CrossRef]

- Paterna S, Di Pasquale P, Parrinello G, Amato P, Cardinale A, Follone G, et al. Effects of high-dose furosemide and small-volume hypertonic saline solution infusion in comparison with a high dose of furosemide as a bolus, in refractory congestive heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2000 Sept;2[3]:305–13. [CrossRef]

- Grodin, J.L. Pharmacologic Approaches to Electrolyte Abnormalities in Heart Failure. Curr. Hear. Fail. Rep. 2016, 13, 181–189. [CrossRef]

- Kataoka, H. Treatment of hypochloremia with acetazolamide in an advanced heart failure patient and importance of monitoring urinary electrolytes. J. Cardiol. Cases 2018, 17, 80–84. [CrossRef]

- Kataoka, H. The “chloride theory”, a unifying hypothesis for renal handling and body fluid distribution in heart failure pathophysiology. Med Hypotheses 2017, 104, 170–173. [CrossRef]

- Kataoka, H. Biochemical Determinants of Changes in Plasma Volume After Decongestion Therapy for Worsening Heart Failure. J. Card. Fail. 2018, 25, 213–217. [CrossRef]

- Kataoka, H. Proposal for heart failure progression based on the ‘chloride theory’: worsening heart failure with increased vs. non-increased serum chloride concentration. ESC Hear. Fail. 2017, 4, 623–631. [CrossRef]

- A Boegehold, M.; A Kotchen, T. Importance of dietary chloride for salt sensitivity of blood pressure. Hypertension 1991, 17, I158–61. [CrossRef]

- Morisawa, D.; Hirotani, S.; Oboshi, M.; Sugahara, M.; Fukui, M.; Ando, T.; Okuhara, Y.; Nakabo, A.; Naito, Y.; Masuyama, T. Combination of hypertonic saline and low-dose furosemide is an effective treatment for refractory congestive heart failure with hyponatremia. J. Cardiol. Cases 2014, 9, 179–182. [CrossRef]

- Jujo, K.; Saito, K.; Ishida, I.; Furuki, Y.; Kim, A.; Suzuki, Y.; Sekiguchi, H.; Yamaguchi, J.; Ogawa, H.; Hagiwara, N. Randomized pilot trial comparing tolvaptan with furosemide on renal and neurohumoral effects in acute heart failure. ESC Heart Fail. 2016, 3, 177–188. [CrossRef]

- Soleimani, M. The multiple roles of pendrin in the kidney. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2014, 30, 1257–1266. [CrossRef]

- Classic and Novel Mechanisms of Diuretic Resistance in Cardiorenal Syndrome - PubMed [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 9]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36128483/.

- A Kotchen, T.; Welch, W.J.; Lorenz, J.N.; E Ott, C. Renal tubular chloride and renin release. 1987, 110, 533–40.

- Hanberg, J.S.; Rao, V.; ter Maaten, J.M.; Laur, O.; Brisco, M.A.; Wilson, F.P.; Grodin, J.L.; Assefa, M.; Broughton, J.S.; Planavsky, N.J.; et al. Hypochloremia and Diuretic Resistance in Heart Failure. Circ. Hear. Fail. 2016, 9. [CrossRef]

- ter Maaten, J.M.; Damman, K.; Hanberg, J.S.; Givertz, M.M.; Metra, M.; O’cOnnor, C.M.; Teerlink, J.R.; Ponikowski, P.; Cotter, G.; Davison, B.; et al. Hypochloremia, Diuretic Resistance, and Outcome in Patients With Acute Heart Failure. Circ. Hear. Fail. 2016, 9. [CrossRef]

- Trajectory of serum chloride levels during decongestive therapy in acute heart failure - PubMed [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 9]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36584943/.

- Hypochloremia, Diuretic Resistance, and Outcome in Patients With Acute Heart Failure - Google Search [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 9]. Available from: https://www.google.com/search?q=Hypochloremia%2C+Diuretic+Resistance%2C+and+Outcome+in+Patients+With+Acute+Heart+Failure&rlz=1C5CHFA_enGR1145GR1145&oq=Hypochloremia%2C+Diuretic+Resistance%2C+and+Outcome+in+Patients+With+Acute+Heart+Failure&gs_lcrp=EgZjaHJvbWUqBggAEEUYOzIGCAAQRRg7MgYIARBFGD0yBggCEEUYPNIBBzcyNmowajSoAgCwAgE&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8.

- Rolofylline, an adenosine A1-receptor antagonist, in acute heart failure - PubMed [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 9]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20925544/.

- Balling, L.; Schou, M.; Videbaek, L.; Hildebrandt, P.; Wiggers, H.; Gustafsson, F.; Network, F.T.D.H.F.C. Prevalence and prognostic significance of hyponatraemia in outpatients with chronic heart failure. Eur. J. Hear. Fail. 2011, 13, 968–973. [CrossRef]

- Klein L, O’Connor CM, Leimberger JD, Gattis-Stough W, Piña IL, Felker GM, et al. Lower serum sodium is associated with increased short-term mortality in hospitalized patients with worsening heart failure: results from the Outcomes of a Prospective Trial of Intravenous Milrinone for Exacerbations of Chronic Heart Failure [OPTIME-CHF] study. Circulation. 2005 May 17;111[19]:2454–60. [CrossRef]

- Rusinaru, D.; Tribouilloy, C.; Berry, C.; Richards, A.M.; Whalley, G.A.; Earle, N.; Poppe, K.K.; Guazzi, M.; Macin, S.M.; Komajda, M.; et al. Relationship of serum sodium concentration to mortality in a wide spectrum of heart failure patients with preserved and with reduced ejection fraction: an individual patient data meta-analysis†. Eur. J. Hear. Fail. 2012, 14, 1139–1146. [CrossRef]

- Felker, G.M.; Mentz, R.J.; Cole, R.T.; Adams, K.F.; Egnaczyk, G.F.; Fiuzat, M.; Patel, C.B.; Echols, M.; Khouri, M.G.; Tauras, J.M.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Tolvaptan in Patients Hospitalized With Acute Heart Failure. JACC 2017, 69, 1399–1406. [CrossRef]

- Kataoka, H. Chloride in Heart Failure Syndrome: Its Pathophysiologic Role and Therapeutic Implication. Cardiol. Ther. 2021, 10, 407–428. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Peng, R.; Li, X.; Yu, J.; Chen, X.; Zhou, Z. Serum chloride as a novel marker for adding prognostic information of mortality in chronic heart failure. Clin. Chim. Acta 2018, 483, 112–118. [CrossRef]

- Felker GM, Allen LA, Pocock SJ, Shaw LK, McMurray JJV, Pfeffer MA, et al. Red cell distribution width as a novel prognostic marker in heart failure: data from the CHARM Program and the Duke Databank. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007 July 3;50[1]:40–7. [CrossRef]

- Grodin, J.L.; Verbrugge, F.H.; Ellis, S.G.; Mullens, W.; Testani, J.M.; Tang, W.W. Importance of Abnormal Chloride Homeostasis in Stable Chronic Heart Failure. Circ. Hear. Fail. 2016, 9, e002453–e002453. [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Q. U-Shaped Relationship of Sodium-to-chloride Ratio on admission and Mortality in Elderly Patients with Heart Failure: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 2022, 48, 101419. [CrossRef]

- Vaduganathan, M.; Pallais, J.C.; Fenves, A.Z.; Butler, J.; Gheorghiade, M. Serum chloride in heart failure: a salty prognosis. Eur. J. Hear. Fail. 2016, 18, 669–671. [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Liu, Y.; Hong, K. The association between serum chloride and mortality in ICU patients with heart failure: The impact of bicarbonate. Int. J. Cardiol. 2023, 399, 131672. [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.N.S.; Nabeel, M.; Nan, B.; Ghali, J.K. Chloride Depletion Alkalosis as a Predictor of Inhospital Mortality in Patients with Decompensated Heart Failure. Cardiology 2015, 131, 151–159. [CrossRef]

- Biegus, J.; Zymliński, R.; Sokolski, M.; Todd, J.; Cotter, G.; Metra, M.; Jankowska, E.A.; Banasiak, W.; Ponikowski, P. Serial assessment of spot urine sodium predicts effectiveness of decongestion and outcome in patients with acute heart failure. Eur. J. Hear. Fail. 2019, 21, 624–633. [CrossRef]

- Mullens, W.; Damman, K.; Harjola, V.; Mebazaa, A.; Rocca, H.B.; Martens, P.; Testani, J.M.; Tang, W.W.; Orso, F.; Rossignol, P.; et al. The use of diuretics in heart failure with congestion — a position statement from the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur. J. Hear. Fail. 2019, 21, 137–155. [CrossRef]

- Authors/Task Force Members:, McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, Gardner RS, Baumbach A, et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: Developed by the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology [ESC]. With the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association [HFA] of the ESC. Eur J Heart Fail. 2022 Jan;24[1]:4–131. [CrossRef]

- Kataoka H. Clinical Significance of Spot Urinary Chloride Concentration Measurements in Patients with Acute Heart Failure: Investigation on the Basis of the TubuloGlomerular Feedback Mechanism. Cardiol Open Access. 2021 Apr 25;6[1]:115–23. [CrossRef]

- Guzik, M.; Zymliński, R.; Ponikowski, P.; Biegus, J. Urine chloride trajectory and relationship with diuretic response in acute heart failure. ESC Hear. Fail. 2024, 12, 133–141. [CrossRef]

- Nawrocka-Millward, S.; Biegus, J.; Fudim, M.; Guzik, M.; Iwanek, G.; Ponikowski, P.; Zymliński, R. The role of urine chloride in acute heart failure. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Verbrugge, F.H.; Nijst, P.; Dupont, M.; Penders, J.; Tang, W.W.; Mullens, W. Urinary Composition During Decongestive Treatment in Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction. Circ. Hear. Fail. 2014, 7, 766–772. [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulos, A.; Christofidis, C.; Pantsios, C.; Magouliotis, D.; Bourazana, A.; Leventis, I.; Skopeliti, N.; Skoularigki, E.; Briasoulis, A.; Giamouzis, G.; et al. The Prognostic Role of Spot Urinary Sodium and Chloride in a Cohort of Hospitalized Advanced Heart Failure Patients: A Pilot Study. Life 2023, 13, 698. [CrossRef]

- Heerspink, H.J.; Perkins, B.A.; Fitchett, D.H.; Husain, M.; Cherney, D.Z.I. Sodium Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibitors in the Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus. Circulation 2016, 134, 752–772. [CrossRef]

- Kataoka, H.; Yoshida, Y. Enhancement of the serum chloride concentration by administration of sodium–glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor and its mechanisms and clinical significance in type 2 diabetic patients: a pilot study. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2020, 12, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Martens, P.; Verbrugge, F.H.; Dauw, J.; Nijst, P.; Meekers, E.; Augusto, S.N.; Ter Maaten, J.M.; Heylen, L.; Damman, K.; Mebazaa, A.; et al. Pre-treatment bicarbonate levels and decongestion by acetazolamide: the ADVOR trial. Eur. Hear. J. 2023, 44, 1995–2005. [CrossRef]

- Effects of hypertonic saline solution on body weight and serum creatinine in patients with acute decompensated heart failure - PubMed [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 27]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28932357/.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).