Submitted:

31 October 2025

Posted:

03 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Hypothesis

3. Rationale and Supporting Evidence

3.1. Myofibroblast Mechanobiology, Tissue Remodelling and Contracture

3.2. Herbicide Residues and Harmful Substances in Food Products

3.3. Myofibroblasts in Visceral Tissue Influence Organ Function and Integrity

3.4. Substrate Stiffness Affects Cell Function and Behaviour

4. Extraintestinal Manifestations of IBS: Pain and Fibromyalgia-Type Symptoms

5. Implications of the Hypothesis

6. Ways to Test the Hypothesis

- Biophysical tests: atomic force microscopy, optical coherence elastography, dynamic mechanical analysis, of sampled tissue (e.g., abdominal fascia, psoas muscle, gut wall) might be insightful, although these would have to take into account the complexity of the model and possible confounding factors, and control for hypermobility syndrome. Age, sex, pH, temperature, hydration, hyaluronic acid composition, adipocytes, cell phenotype and density, are all variables that may affect the properties of tissue.

- Imaging: Results of magnetic resonance elastography investigations, if sensitive enough, are expected to reflect higher abdominal ECM rigidity and reveal abdominal taut bands or fascial nodules and cords.

- Staining: immunohistochemistry and histological staining of tissue samples for myofibroblast markers would reveal a higher density of myofibroblasts in IBS. Presence of vimentin, α-SMA, and connexin 43, should be increased.

- Response to current medications: the most effective pharmacological treatments for IBS that have so far been identified empirically are thus expected to work mainly through an influence on myofibroblasts and fascia (downregulate myofibroblasts and reduce ECM stiffness). As a disorder in the domain of biophysics, extracorporeal shockwave therapy and vibration therapy should be useful in IBS, though not necessarily curative. If myofascial tension in the low back is transmitted to abdominal myofascial tissue through myofascial links, there should be clinical improvement by treating tension in the low back.

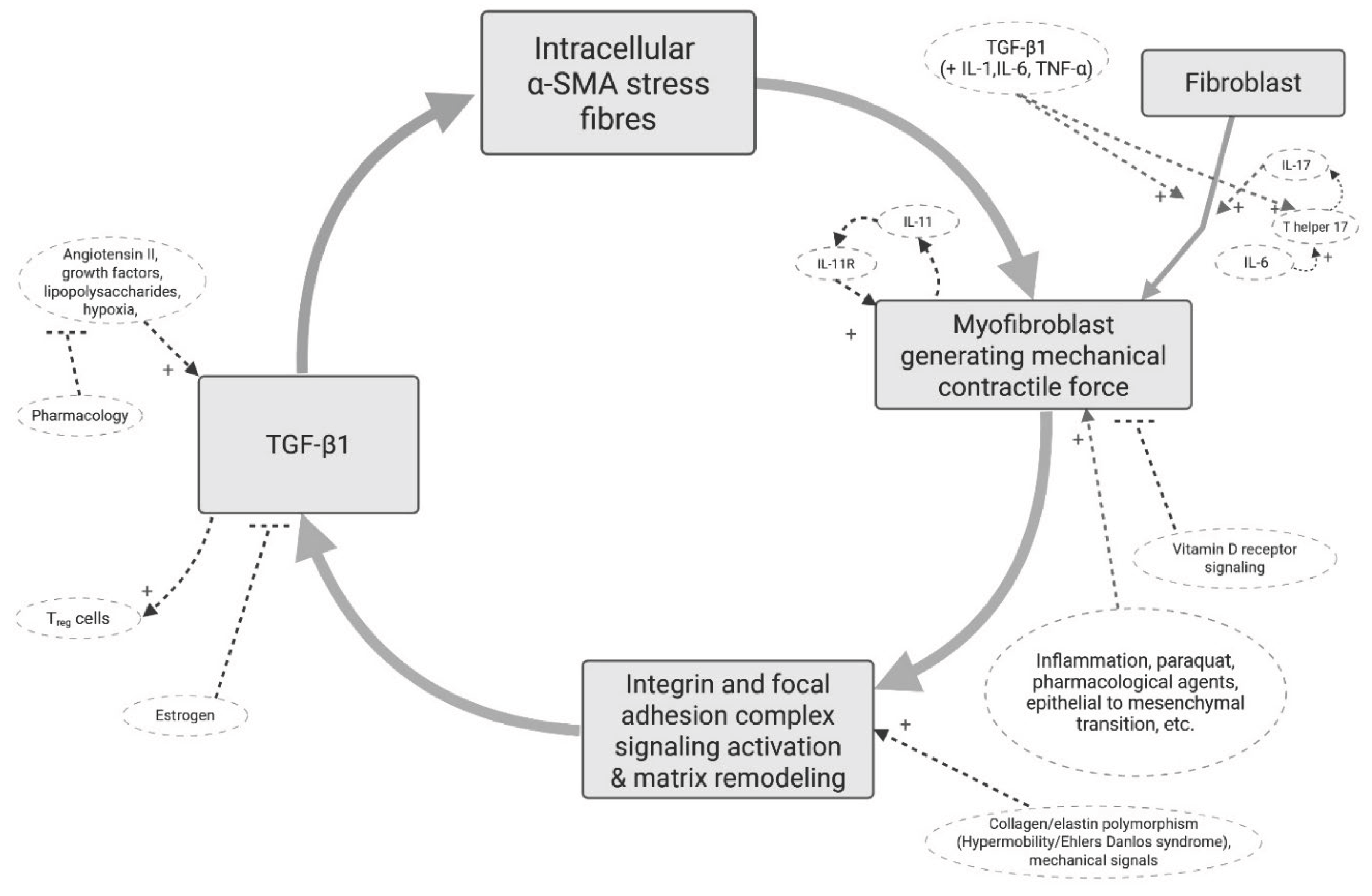

- Issue with systemic pharmacological therapies: A key player in the activation and maintenance of myofibroblasts is the cytokine TGF-β1. At first, based on the myofibroblast theory, systemically targeting the TGF-β pathway pharmacologically seems like a promising therapeutic strategy. However, TGF-β has a multifunctional role in the body. TGF-β is essential for numerous physiological processes, including immune regulation, cell growth, differentiation, and tissue repair. Indiscriminate, systemic inhibition of TGF-β1 can lead to a wide range of severe on-target and off-target adverse effects such as cardiovascular toxicity, immune dysregulation, and more.

7. Limitations and Challenges

8. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

AI Use Disclosure

Abbreviations

References

- Ford AC, Sperber AD, Corsetti M, Camilleri M. Irritable bowel syndrome. Lancet. 2020 Nov 21;396(10263):1675-1688. Epub 2020 Oct 10. PMID: 33049223. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Arendt-Nielsen L, Morlion B, Perrot S, Dahan A, Dickenson A, Kress HG, Wells C, Bouhassira D, Drewes AM. Assessment and manifestation of central sensitisation across different chronic pain conditions. Eur J Pain. 2018 Feb;22(2):216-241. Epub 2017 Nov 5. PMID: 29105941. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Huang KY, Wang FY, Lv M, Ma XX, Tang XD, Lv L. Irritable bowel syndrome: Epidemiology, overlap disorders, pathophysiology and treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2023 Jul 14;29(26):4120-4135. PMID: 37475846; PMCID: PMC10354571. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Ohlsson B. Extraintestinal manifestations in irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2022 Aug 9;15:17562848221114558. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Kurland JE, Coyle WJ, Winkler A, Zable E. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome and depression in fibromyalgia. Dig Dis Sci. 2006 Mar;51(3):454-60. PMID: 16614951. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Wang XJ, Ebbert JO, Loftus CG, Rosedahl JK, Philpot LM. Comorbid extra-intestinal central sensitization conditions worsen irritable bowel syndrome in primary care patients. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2023 Apr;35(4):e14546. Epub 2023 Feb 19. PMID: 36807964. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Luís M, Pinto AM, Häuser W, Jacobs JW, Saraiva A, Giorgi V, Sarzi-Puttini P, Castelo-Branco M, Geenen R, Pereira da Silva JA. Fibromyalgia and post-traumatic stress disorder: different parts of an elephant? Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2025 Jun;43(6):1146-1160. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Bourke JH, Langford RM, White PD. The common link between functional somatic syndromes may be central sensitisation. J Psychosom Res. 2015 Mar;78(3):228-36. Epub 2015 Jan 9. PMID: 25598410. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Wessely S, Nimnuan C, Sharpe M. Functional somatic syndromes: one or many? Lancet. 1999 Sep 11;354(9182):936-9. PMID: 10489969. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Wolfe F, Walitt B, Rasker JJ, Häuser W. Primary and Secondary Fibromyalgia Are The Same: The Universality of Polysymptomatic Distress. J Rheumatol. 2019 Feb;46(2):204-212. Epub 2018 Jul 15. PMID: 30008459; PMCID: PMC12320112. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Talley NJ. Irritable bowel syndrome: definition, diagnosis and epidemiology. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 1999 Oct;13(3):371-84. PMID: 10580915. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Mortensen JH, Manon-Jensen T, Jensen MD, Hägglund P, Klinge LG, Kjeldsen J, Krag A, Karsdal MA, Bay-Jensen AC. Ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, and irritable bowel syndrome have different profiles of extracellular matrix turnover, which also reflects disease activity in Crohn’s disease. PLoS One. 2017 Oct 13;12(10):e0185855. PMID: 29028807; PMCID: PMC5640222. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Kuhn TS. The structures of scientific revolutions. 4th edition (50th anniversary edition). London: University of Chicago Press (2012). Chapter 4. pp 39. n.d.

- Goldenberg DL. How to understand the overlap of long COVID, chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis, fibromyalgia and irritable bowel syndromes. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2024 Aug;67:152455. Epub 2024 May 7. PMID: 38761526. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Maixner W, Fillingim RB, Williams DA, Smith SB, Slade GD. Overlapping Chronic Pain Conditions: Implications for Diagnosis and Classification. J Pain. 2016 Sep;17(9 Suppl):T93-T107. PMID: 27586833; PMCID: PMC6193199. n.d. [CrossRef]

- McKernan LC, Crofford LJ, Kim A, Vandekar SN, Reynolds WS, Hansen KA, Clauw DJ, Williams DA. Electronic Delivery of Pain Education for Chronic Overlapping Pain Conditions: A Prospective Cohort Study. Pain Med. 2021 Oct 8;22(10):2252-2262. PMID: 33871025; PMCID: PMC8677459. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Valencia C, Fatima H, Nwankwo I, Anam M, Maharjan S, Amjad Z, Abaza A, Vasavada AM, Sadhu A, Khan S. A Correlation Between the Pathogenic Processes of Fibromyalgia and Irritable Bowel Syndrome in the Middle-Aged Population: A Systematic Review. Cureus. 2022 Oct 4;14(10):e29923. PMID: 36381861; PMCID: PMC9635936. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Fall EA, Chen Y, Lin JS, Issa A, Brimmer DJ, Bateman L, Lapp CW, Podell RN, Natelson BH, Kogelnik AM, Klimas NG, Peterson DL, Unger ER; MCAM Study Group. Chronic Overlapping Pain Conditions in people with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS): a sample from the Multi-site Clinical Assessment of ME/CFS (MCAM) study. BMC Neurol. 2024 Oct 18;24(1):399. PMID: 39425035; PMCID: PMC11488184. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Johnston KJA, Signer R, Huckins LM. Chronic overlapping pain conditions and nociplastic pain. HGG Adv. 2025 Jan 9;6(1):100381. Epub 2024 Nov 4. PMID: 39497418; PMCID: PMC11617767. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Alpers DH. Is irritable bowel syndrome more than just a gastroenterologist’s problem? Am J Gastroenterol. 2001 Apr;96(4):943-5. PMID: 11316208. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Plaut S. Scoping review and interpretation of myofascial pain/fibromyalgia syndrome: An attempt to assemble a medical puzzle. PLoS One 2022;17. [CrossRef]

- Plaut S. Disrupted Biotensegrity in the Fiber Cellular Fascial Network and Neuroma Microenvironment: A Conceptual Framework for “Phantom Limb Pain”. Int J Mol Sci. 2025 Aug 22;26(17):8161. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Goebel A, Andersson D, Shoenfeld Y. The biology of symptom-based disorders - time to act. Autoimmun Rev. 2023 Jan;22(1):103218. Epub 2022 Oct 22. PMID: 36280093. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Malkova AM, Shoenfeld Y. Autoimmune autonomic nervous system imbalance and conditions: Chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia, silicone breast implants, COVID and post-COVID syndrome, sick building syndrome, post-orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, autoimmune diseases and autoimmune/inflammatory syndrome induced by adjuvants. Autoimmunity reviews. 2023 Jan 1;22(1):103230. n.d.

- Tomasek JJ, Gabbiani G, Hinz B, Chaponnier C, Brown RA. Myofibroblasts and mechano: Regulation of connective tissue remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2002;3:349–63. [CrossRef]

- Moyer KE, Banducci DR, Graham WP 3rd, Ehrlich HP. Dupuytren’s disease: physiologic changes in nodule and cord fibroblasts through aging in vitro. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002 Jul;110(1):187-93; discussion 194-6. PMID: 12087251. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Bisson MA, Mudera V, McGrouther DA, Grobbelaar AO. The contractile properties and responses to tensional loading of Dupuytren’s disease--derived fibroblasts are altered: a cause of the contracture? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004 Feb;113(2):611-21; discussion 622-4. PMID: 14758224. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Ziegler ME, Staben A, Lem M, Pham J, Alaniz L, Halaseh FF, Obagi S, Leis A, Widgerow AD. Targeting Myofibroblasts as a Treatment Modality for Dupuytren Disease. J Hand Surg Am. 2023 Sep;48(9):914-922. Epub 2023 Jul 20. PMID: 37480917. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Zhao F, Zhang M, Nizamoglu M, Kaper HJ, Brouwer LA, Borghuis T, Burgess JK, Harmsen MC, Sharma PK. Fibroblast alignment and matrix remodeling induced by a stiffness gradient in a skin-derived extracellular matrix hydrogel. Acta Biomater. 2024 Jul 1;182:67-80. Epub 2024 May 13. PMID: 38750915. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Jendzjowsky NG, Kelly MM. The Role of Airway Myofibroblasts in Asthma. Chest. 2019 Dec;156(6):1254-1267. Epub 2019 Aug 28. PMID: 31472157. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Johnson RD, Lei M, McVey JH, Camelliti P. Human myofibroblasts increase the arrhythmogenic potential of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2023 Sep 5;80(9):276. Erratum in: Cell Mol Life Sci. 2024 Dec 27;82(1):20. doi:10.1007/s00018-024-05492-w. PMID: 37668685; PMCID: PMC10480244. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Kinchen J, Chen HH, Parikh K, Antanaviciute A, Jagielowicz M, Fawkner-Corbett D, Ashley N, Cubitt L, Mellado-Gomez E, Attar M, Sharma E, Wills Q, Bowden R, Richter FC, Ahern D, Puri KD, Henault J, Gervais F, Koohy H, Simmons A. Structural Remodeling of the Human Colonic Mesenchyme in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Cell. 2018 Oct 4;175(2):372-386.e17. Epub 2018 Sep 27. PMID: 30270042; PMCID: PMC6176871. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Kruglikov IL, Scherer PE. The Role of Adipocytes and Adipocyte-Like Cells in the Severity of COVID-19 Infections. Obesity 2020;28:1187–90. [CrossRef]

- Martin K, Pritchett J, Llewellyn J, Mullan AF, Athwal VS, Dobie R, et al. PAK proteins and YAP-1 signalling downstream of integrin beta-1 in myofibroblasts promote liver fibrosis. Nat Commun 2016;7. [CrossRef]

- Wang S, Meng X-M, Ng Y-Y, Ma FY, Zhou S, Zhang Y, et al. TGF-β/Smad3 signalling regulates the transition of bone marrow-derived macrophages into myofibroblasts during tissue fibrosis. vol. 7. n.d.

- Stempien-Otero A, Kim DH, Davis J. Molecular networks underlying myofibroblast fate and fibrosis. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2016;97:153–61. [CrossRef]

- Hinz B, Lagares D. Evasion of apoptosis by myofibroblasts: a hallmark of fibrotic diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2020 Jan;16(1):11-31. Epub 2019 Dec 2. PMID: 31792399; PMCID: PMC7913072. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Hinz B, Mastrangelo D, Iselin CE, Chaponnier C, Gabbiani G. Mechanical tension controls granulation tissue contractile activity and myofibroblast differentiation. American Journal of Pathology 2001;159:1009–20. [CrossRef]

- Sasabe R, Sakamoto J, Goto K, Honda Y, Kataoka H, Nakano J, et al. Effects of joint immobilization on changes in myofibroblasts and collagen in the rat knee contracture model. Journal of Orthopaedic Research 2017;35:1998–2006. [CrossRef]

- Seo BR, Chen X, Ling L, Song YH, Shimpi AA, Choi S, et al. Collagen microarchitecture mechanically controls myofibroblast differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(21):11387–11398. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Sari E, Oztay F, Tasci AE. Vitamin D modulates E-cadherin turnover by regulating TGF-β and Wnt signalings during EMT-mediated myofibroblast differentiation in A459 cells. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 2020;202. [CrossRef]

- Sun Z, Yang Z, Wang M, Huang C, Ren Y, Zhang W, Gao F, Cao L, Li L, Nie S. Paraquat induces pulmonary fibrosis through Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway and myofibroblast differentiation. Toxicol Lett. 2020 Oct 15;333:170-183. Epub 2020 Aug 11. PMID: 32795487. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Lee SA, Yang HW, Um JY, Shin JM, Park IH, Lee HM. Vitamin D attenuates myofibroblast differentiation and extracellular matrix accumulation in nasal polyp-derived fibroblasts through smad2/3 signaling pathway. Sci Rep. 2017 Aug 4;7(1):7299. PMID: 28779150; PMCID: PMC5544725. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Olson ER, Naugle JE, Zhang X, Bomser JA, Meszaros JG. Inhibition of cardiac fibroblast proliferation and myofibroblast differentiation by resveratrol. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005 Mar;288(3):H1131-8. Epub 2004 Oct 21. PMID: 15498824. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Baghdasaryan A, Claudel T, Kosters A, Gumhold J, Silbert D, Thüringer A, Leski K, Fickert P, Karpen SJ, Trauner M. Curcumin improves sclerosing cholangitis in Mdr2-/- mice by inhibition of cholangiocyte inflammatory response and portal myofibroblast proliferation. Gut. 2010 Apr;59(4):521-30. PMID: 20332524; PMCID: PMC3756478. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Yang W, Zhang S, Zhu J, Jiang H, Jia D, Ou T, Qi Z, Zou Y, Qian J, Sun A, Ge J. Gut microbe-derived metabolite trimethylamine N-oxide accelerates fibroblast-myofibroblast differentiation and induces cardiac fibrosis. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2019 Sep;134:119-130. Epub 2019 Jul 9. PMID: 31299216. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Wu M, Han M, Li J, Xu X, Li T, Que L, Ha T, Li C, Chen Q, Li Y. 17beta-estradiol inhibits angiotensin II-induced cardiac myofibroblast differentiation. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009 Aug 15;616(1-3):155-9. Epub 2009 May 24. PMID: 19470381. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Kheirollahi V, Wasnick RM, Biasin V, Vazquez-Armendariz AI, Chu X, Moiseenko A, Weiss A, Wilhelm J, Zhang JS, Kwapiszewska G, Herold S, Schermuly RT, Mari B, Li X, Seeger W, Günther A, Bellusci S, El Agha E. Metformin induces lipogenic differentiation in myofibroblasts to reverse lung fibrosis. Nat Commun. 2019 Jul 5;10(1):2987. PMID: 31278260; PMCID: PMC6611870. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Zoppi N, Chiarelli N, Binetti S, Ritelli M, Colombi M. Dermal fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transition sustained by αvß3 integrin-ILK-Snail1/Slug signaling is a common feature for hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and hypermobility spectrum disorders. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 2018;1864:1010–23. [CrossRef]

- Chiarelli N, Zoppi N, Ritelli M, Venturini M, Capitanio D, Gelfi C, et al. Biological insights in the pathogenesis of hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome from proteome profiling of patients’ dermal myofibroblasts. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 2021;1867. [CrossRef]

- Johnson LA, Sauder KL, Rodansky ES, Simpson RU, Higgins PD. CARD-024, a vitamin D analog, attenuates the pro-fibrotic response to substrate stiffness in colonic myofibroblasts. Exp Mol Pathol. 2012 Aug;93(1):91-8. Epub 2012 Apr 18. PMID: 22542712; PMCID: PMC6443252. n.d. [CrossRef]

- da Silva TM, Seabra LMJ, Colares LGT, de Araújo BLPC, Pires VCDC, Rolim PM. Risk assessment of pesticide residues ingestion in food offered by institutional restaurant menus. PLoS One. 2024 Dec 18;19(12):e0313836. PMID: 39693277; PMCID: PMC11654986. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Magulova K, Priceputu A. Global monitoring plan for persistent organic pollutants (POPs) under the Stockholm Convention: Triggering, streamlining and catalyzing global POPs monitoring. Environ Pollut. 2016 Oct;217:82-4. Epub 2016 Jan 18. PMID: 26794340. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Wei D, Shi J, Chen Z, Xu H, Wu X, Guo Y, Zen X, Fan C, Liu X, Hou J, Huo W, Li L, Jing T, Wang C, Mao Z. Unraveling the pesticide-diabetes connection: A case-cohort study integrating Mendelian randomization analysis with a focus on physical activity’s mitigating effect. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2024 Sep 15;283:116778. Epub 2024 Jul 26. PMID: 39067072. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Ospina M, Schütze A, Morales-Agudelo P, Vidal M, Wong LY, Calafat AM. Temporal trends of exposure to the herbicide glyphosate in the United States (2013-2018): Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Chemosphere. 2024 Sep;364:142966. Epub 2024 Jul 27. PMID: 39074666; PMCID: PMC11590049. n.d. [CrossRef]

- McGwin G Jr, Griffin RL. An ecological study regarding the association between paraquat exposure and end stage renal disease. Environ Health. 2022 Dec 12;21(1):127. PMID: 36503540; PMCID: PMC9743741. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Wang K, Zhang C, Zhang B, Li G, Shi G, Cai Q, Huang M. Gut dysfunction may be the source of pathological aggregation of alpha-synuclein in the central nervous system through Paraquat exposure in mice. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2022 Nov;246:114152. Epub 2022 Oct 3. PMID: 36201918. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Sanmarco LM, Chao CC, Wang YC, Kenison JE, Li Z, Rone JM, Rejano-Gordillo CM, et al. Identification of environmental factors that promote intestinal inflammation. Nature. 2022 Nov;611(7937):801-809. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Chen C, Qi M, Zhang W, Chen F, Sun Z, Sun W, Tang W, Yang Z, Zhao X, Tang Z. Taurine alleviated paraquat-induced oxidative stress and gut-liver axis damage in weaned piglets by regulating the Nrf2/Keap1 and TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathways. J Anim Sci Biotechnol. 2025 Aug 18;16(1):117. PMID: 40826133; PMCID: PMC12359926. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Sadighara P, Mahmudiono T, Marufi N, Yazdanfar N, Fakhri Y, Rikabadi AK, Khaneghah AM. Residues of carcinogenic pesticides in food: a systematic review. Rev Environ Health. 2023 Jun 6;39(4):659-666. PMID: 37272608. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Yang Z, Wang M, Cao L, Liu R, Ren Y, Li L, Zhang Y, Liu C, Zhang W, Nie S, Sun Z. Interference with connective tissue growth factor attenuated fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transition and pulmonary fibrosis. Ann Transl Med. 2022 May;10(10):566. PMID: 35722387; PMCID: PMC9201195. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Tyagi N, Singh DK, Dash D, Singh R. Curcumin Modulates Paraquat-Induced Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition by Regulating Transforming Growth Factor-β (TGF-β) in A549 Cells. Inflammation. 2019 Aug;42(4):1441-1455. PMID: 31028577. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Jeong JY, Kim B, Ji SY, Baek YC, Kim M, Park SH, Kim KH, Oh SI, Kim E, Jung H. Effect of Pesticide Residue in Muscle and Fat Tissue of Pigs Treated with Propiconazole. Food Sci Anim Resour. 2021 Nov;41(6):1022-1035. Epub 2021 Nov 1. PMID: 34796328; PMCID: PMC8564320. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen TP, Xie Y, Garfinkel A, Qu Z, Weiss JN. Arrhythmogenic consequences of myofibroblastmyocyte coupling. Cardiovasc Res 2012;93:242–51. [CrossRef]

- Grafstein B, Liu S, Cotrina ML, Goldman SA, Nedergaard M. Meningeal Cells Can Communicate with Astrocytes by Calcium Signaling. vol. 47. 2000.

- Sui G-P, Wu C, Roosen A, Ikeda Y, Kanai AJ, Fry CH. Modulation of bladder myofibroblast activity: implications for bladder function. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2008;295:688–97. [CrossRef]

- Follonier L, Schaub S, Meister JJ, Hinz B. Myofibroblast communication is controlled by intercellular mechanical coupling. J Cell Sci. 2008 Oct 15;121(Pt 20):3305-16. Epub 2008 Sep 30. PMID: 18827018. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Adegboyega PA, Mifflin RC, DiMari JF, Saada JI, Powell DW. Immunohistochemical study of myofibroblasts in normal colonic mucosa, hyperplastic polyps, and adenomatous colorectal polyps. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2002 Jul;126(7):829-36. PMID: 12088453. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Andoh A, Fujino S, Okuno T, Fujiyama Y, Bamba T. Intestinal subepithelial myofibroblasts in inflammatory bowel diseases. J Gastroenterol. 2002 Nov;37 Suppl 14:33-7. PMID: 12572863. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Neuhaus J, Pfeiffer F, Wolburg H, Horn LC, Dorschner W. Alterations in connexin expression in the bladder of patients with urge symptoms. BJU Int. 2005 Sep;96(4):670-6. PMID: 16104929. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Kohl P, Camelliti P, Burton FL, Smith GL. Electrical coupling of fibroblasts and myocytes: relevance for cardiac propagation. J Electrocardiol. 2005 Oct;38(4 Suppl):45-50. PMID: 16226073. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Camelliti P, Green CR, LeGrice I, Kohl P. Fibroblast network in rabbit sinoatrial node: structural and functional identification of homogeneous and heterogeneous cell coupling. Circ Res. 2004 Apr 2;94(6):828-35. Epub 2004 Feb 19. PMID: 14976125. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Camelliti P, Green CR, Kohl P. Structural and functional coupling of cardiac myocytes and fibroblasts. Adv Cardiol. 2006;42:132-149. PMID: 16646588. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Andoh A, Ogawa A, Bamba S, Fujiyama Y. Interaction between interleukin-17-producing CD4+ T cells and colonic subepithelial myofibroblasts: what are they doing in mucosal inflammation? J Gastroenterol. 2007 Jan;42 Suppl 17:29-33. PMID: 17238023. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Kayal C, Moeendarbary E, Shipley RJ, Phillips JB. Mechanical Response of Neural Cells to Physiologically Relevant Stiffness Gradients. Adv Healthc Mater. 2020 Apr;9(8):e1901036. Epub 2019 Dec 2. PMID: 31793251; PMCID: PMC8407326. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Lantoine J, Grevesse T, Villers A, Delhaye G, Mestdagh C, Versaevel M, Mohammed D, Bruyère C, Alaimo L, Lacour SP, Ris L, Gabriele S. Matrix stiffness modulates formation and activity of neuronal networks of controlled architectures. Biomaterials. 2016 May;89:14-24. Epub 2016 Feb 26. PMID: 26946402. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Gu Y, Ji Y, Zhao Y, Liu Y, Ding F, Gu X, Yang Y. The influence of substrate stiffness on the behavior and functions of Schwann cells in culture. Biomaterials. 2012 Oct;33(28):6672-81. Epub 2012 Jun 25. PMID: 22738780. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Baghdadi MB, Houtekamer RM, Perrin L, Rao-Bhatia A, Whelen M, Decker L, Bergert M, Pérez-Gonzàlez C, Bouras R, Gropplero G, Loe AKH, Afkhami-Poostchi A, Chen X, Huang X, Descroix S, Wrana JL, Diz-Muñoz A, Gloerich M, Ayyaz A, Matic Vignjevic D, Kim TH. PIEZO-dependent mechanosensing is essential for intestinal stem cell fate decision and maintenance. Science. 2024 Nov 29;386(6725):eadj7615. Epub 2024 Nov 29. PMID: 39607940. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Wang F, Knutson K, Alcaino C, Linden DR, Gibbons SJ, Kashyap P, Grover M, Oeckler R, Gottlieb PA, Li HJ, Leiter AB, Farrugia G, Beyder A. Mechanosensitive ion channel Piezo2 is important for enterochromaffin cell response to mechanical forces. J Physiol. 2017 Jan 1;595(1):79-91. Epub 2016 Aug 13. PMID: 27392819; PMCID: PMC5199733. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Alcaino C, Knutson KR, Treichel AJ, Yildiz G, Strege PR, Linden DR, Li JH, Leiter AB, Szurszewski JH, Farrugia G, Beyder A. A population of gut epithelial enterochromaffin cells is mechanosensitive and requires Piezo2 to convert force into serotonin release. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018 Aug 7;115(32):E7632-E7641. Epub 2018 Jul 23. PMID: 30037999; PMCID: PMC6094143. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Sperber AD, Atzmon Y, Neumann L, Weisberg I, Shalit Y, Abu-Shakrah M, Fich A, Buskila D. Fibromyalgia in the irritable bowel syndrome: studies of prevalence and clinical implications. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999 Dec;94(12):3541-6. PMID: 10606316. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Slim M, Calandre EP, Rico-Villademoros F. An insight into the gastrointestinal component of fibromyalgia: clinical manifestations and potential underlying mechanisms. Rheumatol Int. 2015 Mar;35(3):433-44. Epub 2014 Aug 14. PMID: 25119830. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Wang XJ, Ebbert JO, Loftus CG, Rosedahl JK, Philpot LM. Comorbid extra-intestinal central sensitization conditions worsen irritable bowel syndrome in primary care patients. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2023 Apr;35(4):e14546. Epub 2023 Feb 19. PMID: 36807964. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Doggweiler-Wiygul R. Urologic myofascial pain syndromes. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2004 Dec;8(6):445-51. PMID: 15509457. n.d. [CrossRef]

- Drossman DA. Do psychosocial factors define symptom severity and patient status in irritable bowel syndrome? Am J Med. 1999 Nov 8;107(5A):41S-50S. PMID: 10588172. n.d. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).