Submitted:

02 November 2025

Posted:

04 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Background

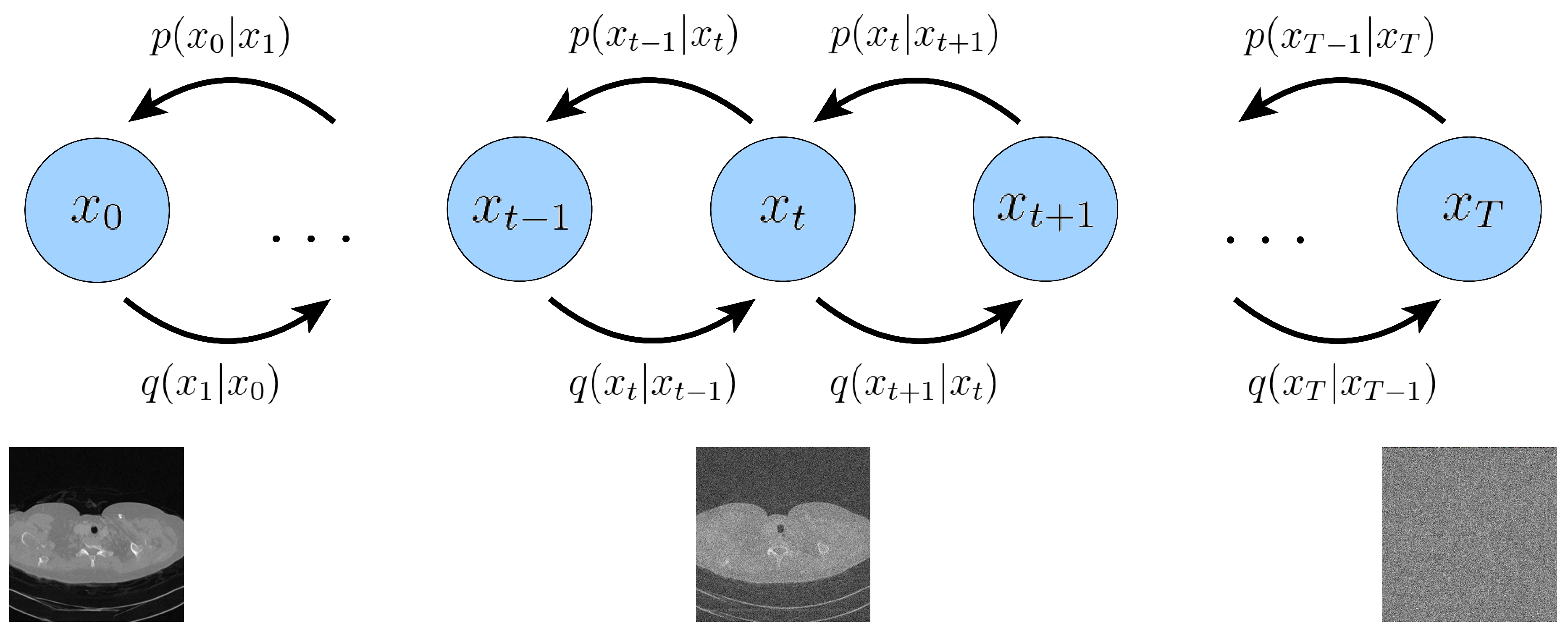

2.1. Variational Diffusion Models

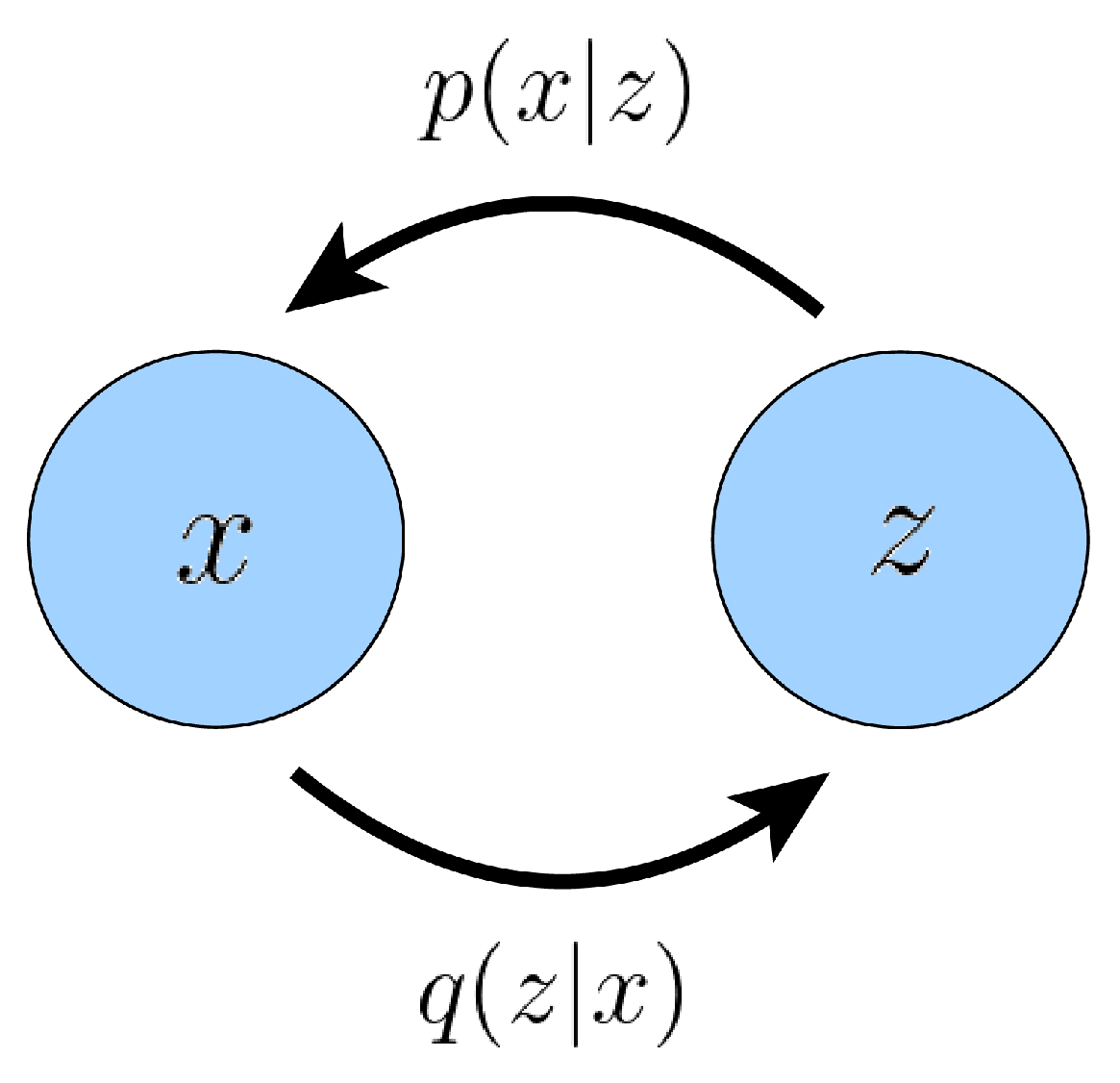

2.1.1. Variational Autoencoders

2.1.2. Hierarchical Variational Autoencoders

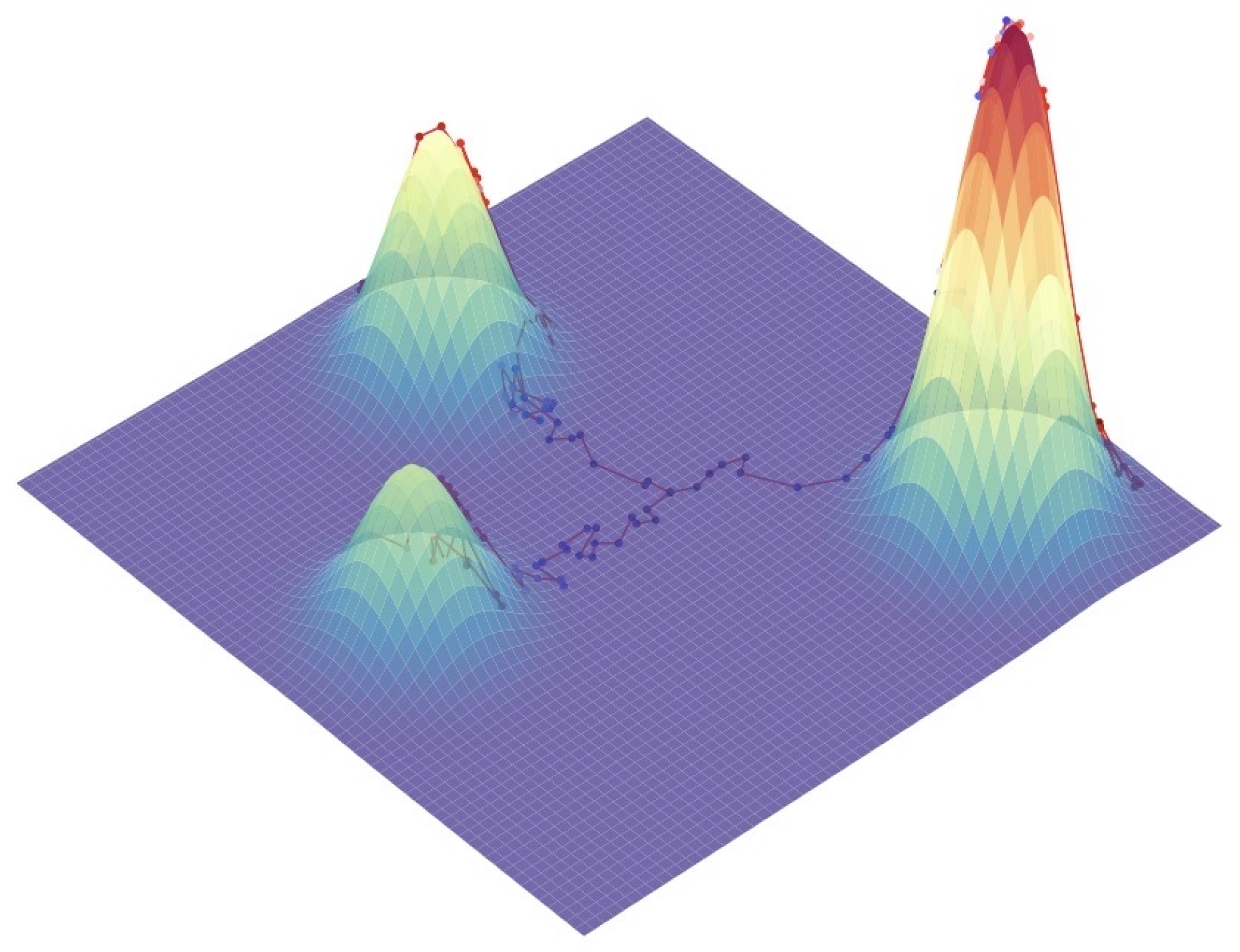

2.1.3. Unconditional Score-based Generative Model

2.1.4. Classifier-Free Guidance

2.2. Sparse-View Computer Tomography Inverse Problems

3. Methodology

3.1. Projection Onto Convex Sets (POCS)

3.2. Imputation in the Radon Domain

3.3. PC-POCS Sampling

| Algorithm 1 PC-POCS |

|

4. Experiment

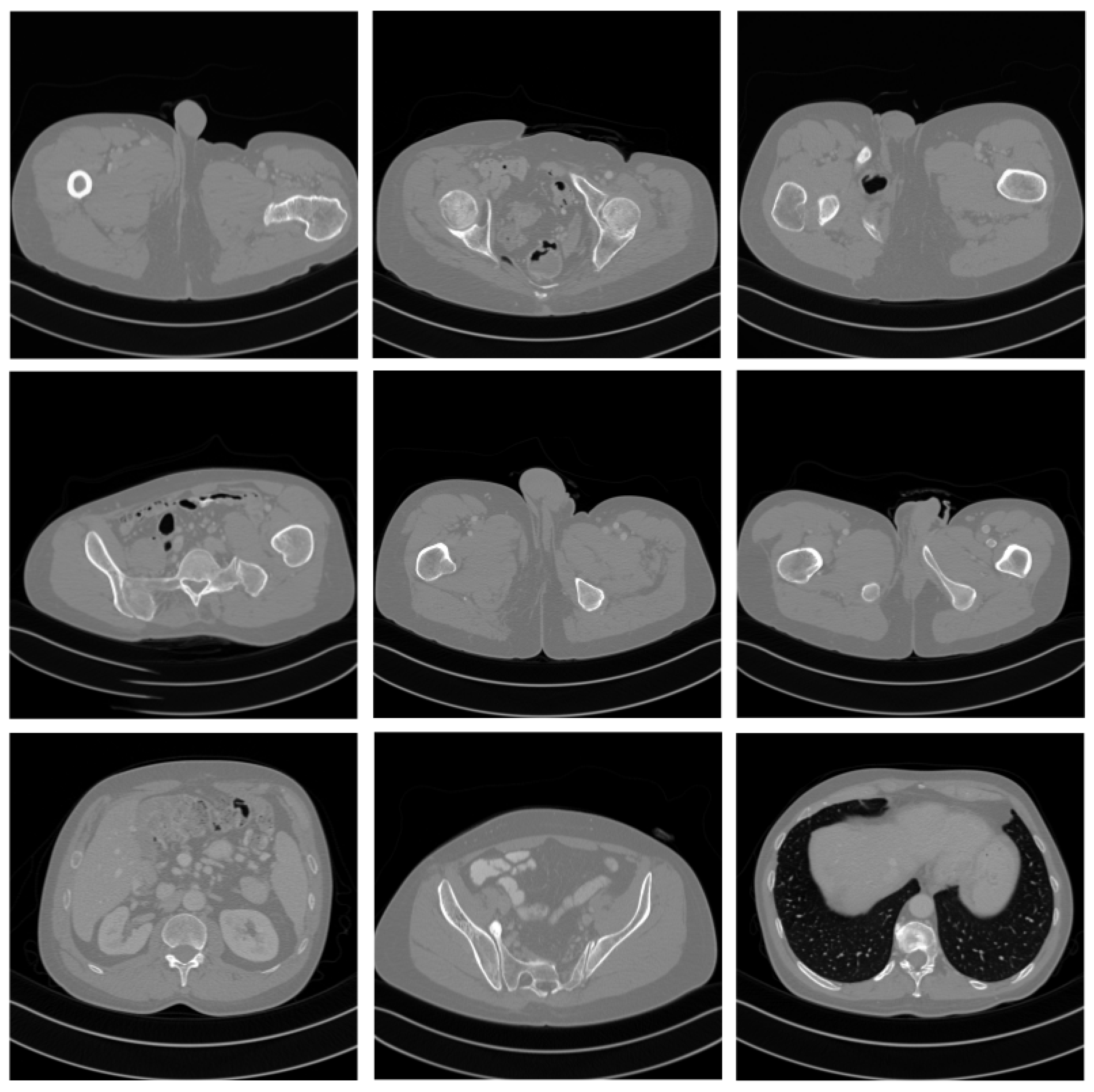

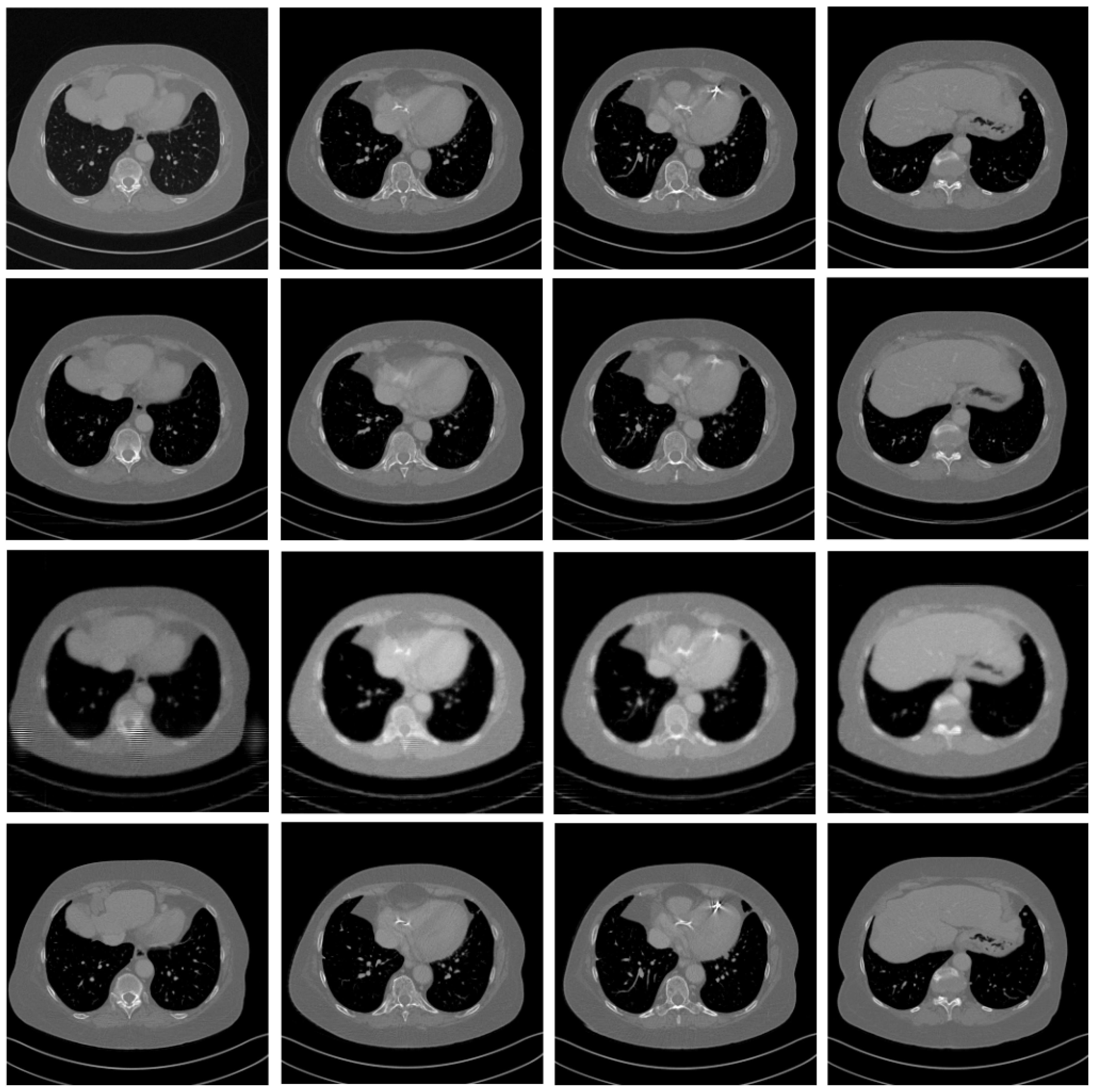

4.1. Dataset

4.2. Details of Network Training

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

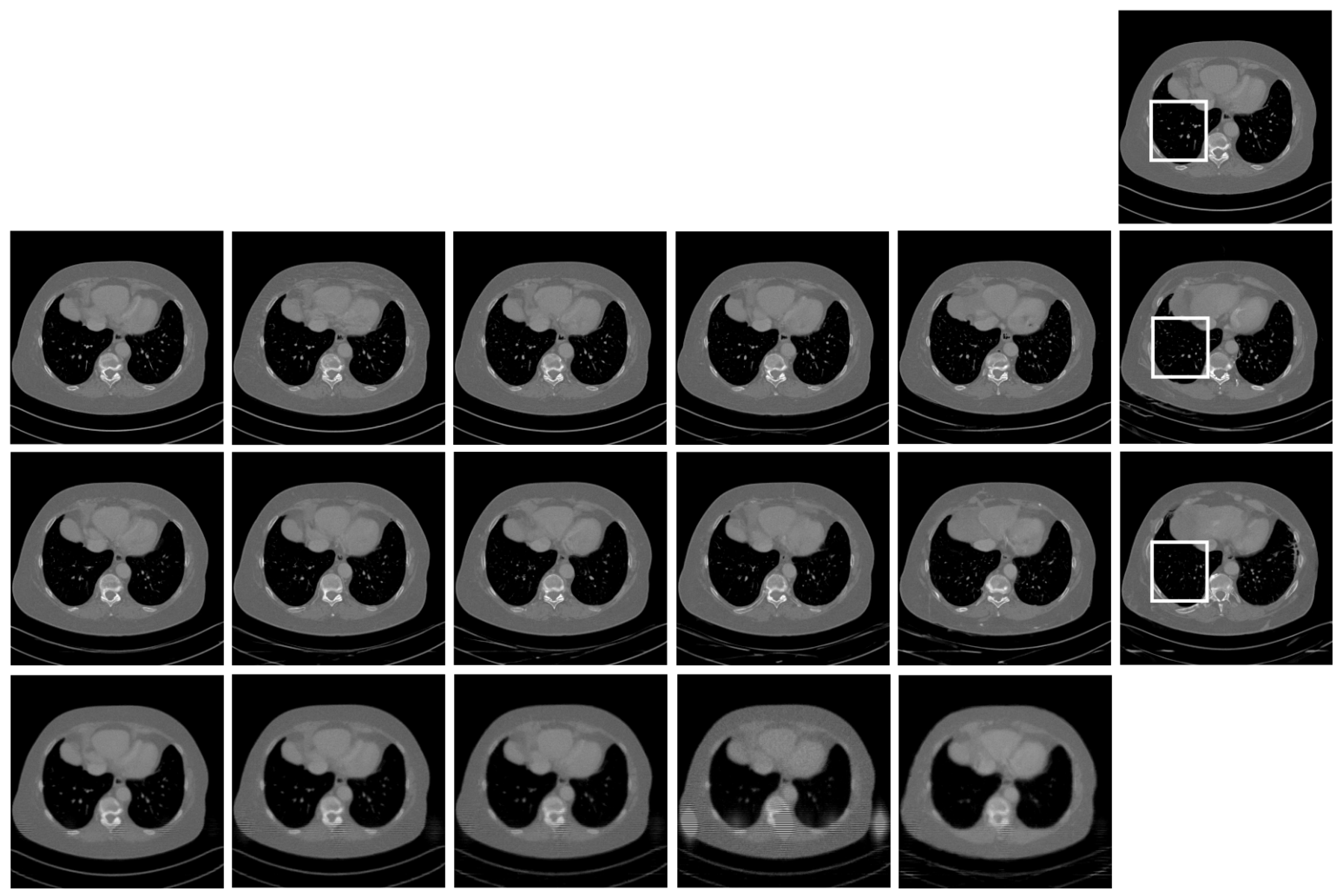

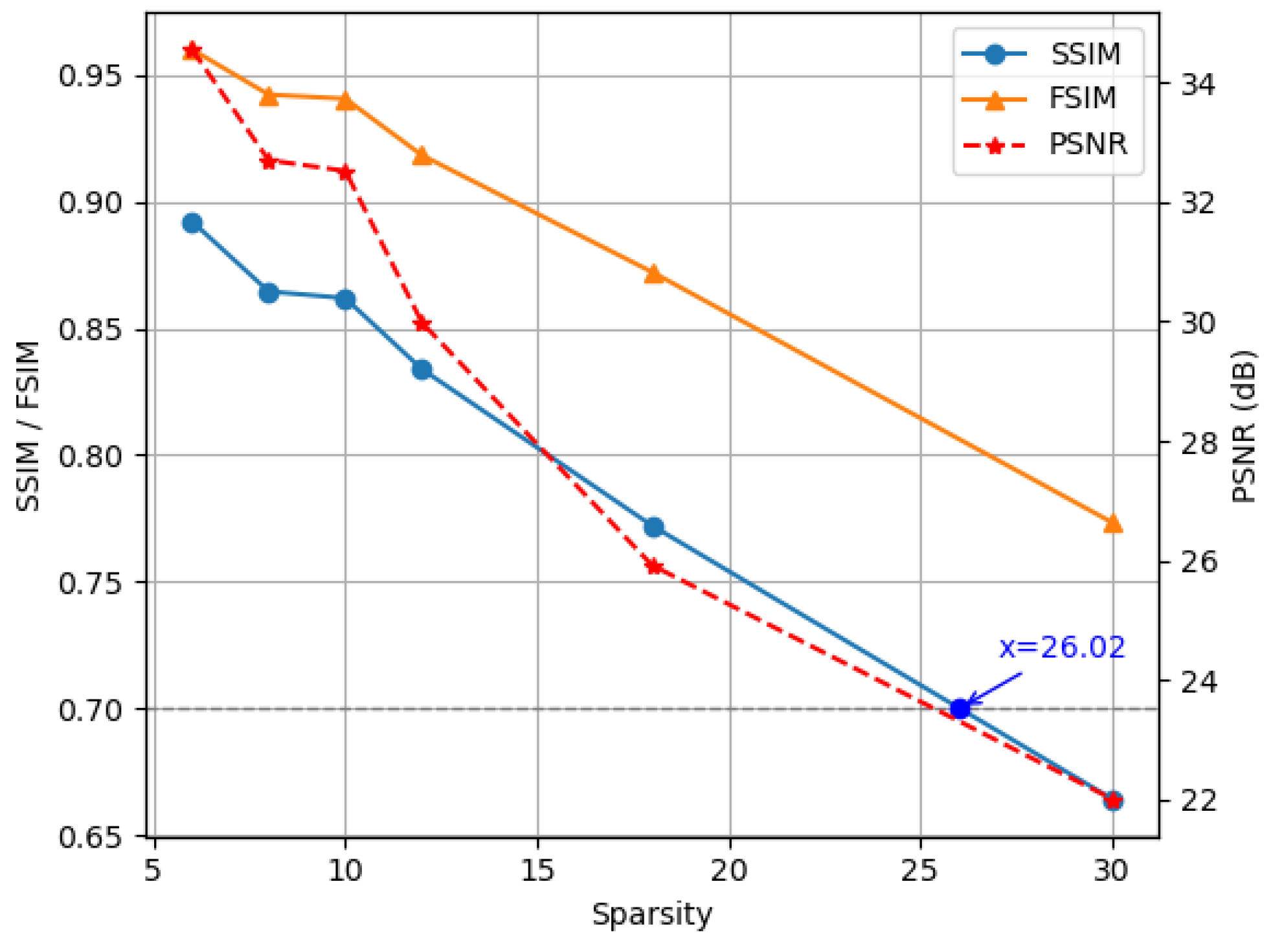

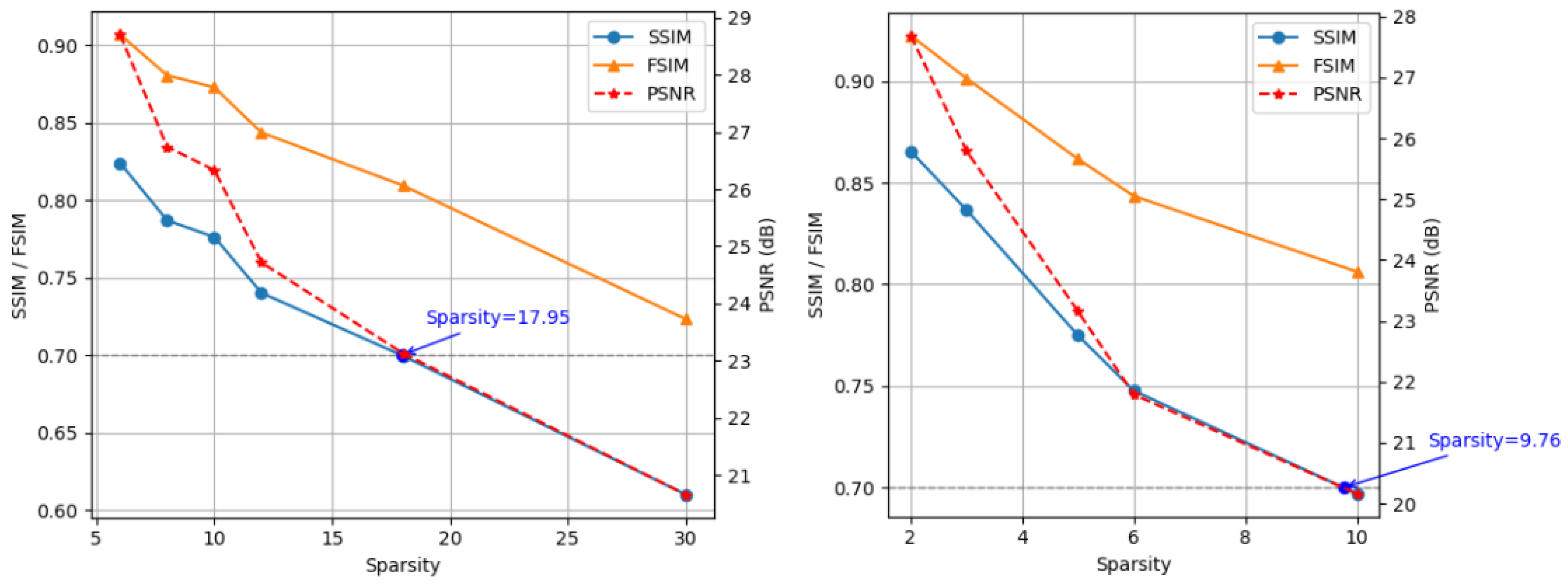

4.4. Comparative Experiment with the State-of-the-Art Methods

4.5. Ablation Study

5. Conclusion

5.1. Limitations

5.2. Broader Impact

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhu, B., Liu, J., Cauley, S. et al. Image reconstruction by domain-transform manifold learning. Nature 555, 487–492 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Morteza Mardani, Enhao Gong, Joseph Y Cheng, Shreyas Vasanawala, Greg Zaharchuk, Marcus Alley, Neil Thakur, Song Han, William Dally, John M Pauly, et al. Deep generative adversarial networks for compressed sensing automate MRI. arXiv preprint, 2017. arXiv:1706.00051.

- Liyue Shen, Wei Zhao, and Lei Xing. Patient-specific reconstruction of volumetric computed tomography images from a single projection view via deep learning. Nature biomedical engineering, 3(11):880–888, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Tobias Würfl, Mathis Hoffmann, Vincent Christlein, Katharina Breininger, Yixin Huang, Mathias Unberath, and Andreas K Maier. Deep learning computed tomography: Learning projection domain weights from image domain in limited angle problems. IEEE transactions on medical imaging, 37(6):1454–1463, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Muhammad Usman Ghani and W Clem Karl. Deep learning-based sinogram completion for low-dose CT. In 2018 IEEE 13th Image, Video, and Multidimensional Signal Processing Workshop (IVMSP), pp. 1–5. IEEE, 2018.

- Haoyu Wei, Florian Schiffers, Tobias Würfl, Daming Shen, Daniel Kim, Aggelos K Katsaggelos, and Oliver Cossairt. 2-step sparse-view CT reconstruction with a domain-specific perceptual network. arXiv preprint, 2020. arXiv:2012.04743.

- Vegard Antun, Francesco Renna, Clarice Poon, Ben Adcock, and Anders C Hansen. On instabilities of deep learning in image reconstruction and the potential costs of AI. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(48):30088–30095, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Yang Song and Stefano Ermon. Generative modeling by estimating gradients of the data distribution. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, pp. 11918–11930, 2019.

- Yang Song, Jascha Sohl-Dickstein, Diederik P Kingma, Abhishek Kumar, Stefano Ermon, and Ben Poole. Score-based generative modeling through stochastic differential equations. In International Conference on Learning Representations, 2021. URL https://openreview.net/forum? id=PxTIG12RRHS.

- Sander Dieleman. Guidance: a cheat code for diffusion models, 2022. URL https://benanne.github.io/2022/ 05/26/guidance.html.

- Yang Song, Liyue Shen, Lei Xing, and Stefano Ermon. Solving inverse problems in medical imaging with score-based generative models. In International Conference on Learning Representations, 2022.

- Hyungjin Chung, Byeongsu Sim, Dohoon Ryu, and Jong Chul Ye. 2022. Improving diffusion models for inverse problems using manifold constraints. In Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS ’22). Curran Associates Inc., Red Hook, NY, USA, Article 1862, 25683–25696.

- Diederik P Kingma and Max Welling. Auto-encoding variational bayes. arXiv preprint, 2013. arXiv:1312.6114.

- Danilo Jimenez Rezende, Shakir Mohamed, and Daan Wierstra. Stochastic backpropagation and approximate inference in deep generative models. In International Conference on machine learning, pages 1278–1286. PMLR, 2014.

- Durk P Kingma, Tim Salimans, Rafal Jozefowicz, Xi Chen, Ilya Sutskever, and Max Welling. Improved variational inference with inverse autoregressive flow. Advances in neural information processing systems, 29, 2016.

- Casper Kaae Sønderby, Tapani Raiko, Lars Maaløe, Søren Kaae Sønderby, and Ole Winther. Ladder variational autoencoders. Advances in neural information processing systems, 29, 2016.

- Jascha Sohl-Dickstein, Eric Weiss, Niru Maheswaranathan, and Surya Ganguli. Deep unsupervised learning using nonequilibrium thermodynamics. In International Conference on Machine Learning, pages 2256–2265. PMLR, 2015.

- Jonathan Ho, Ajay Jain, and Pieter Abbeel. Denoising diffusion probabilistic models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 33:6840–6851, 2020.

- Diederik Kingma, Tim Salimans, Ben Poole, and Jonathan Ho. Variational diffusion models. Advances in neural information processing systems, 34:21696–21707, 2021.

- Chitwan Saharia, William Chan, Saurabh Saxena, Lala Li, Jay Whang, Emily Denton, Seyed Kamyar Seyed Ghasemipour, Burcu Karagol Ayan, Sara Mahdavi, Rapha Gontijo Lopes, et al. Photorealistic text-to-image diffusion models with deep language understanding. arXiv preprint, 2022. arXiv:2205.11487.

- Jonathan Ho and Tim Salimans. Classifier-free diffusion guidance. In NeurIPS 2021 Workshop on Deep Generative Models and Downstream Applications, 2021.

- Eunhee Kang, Junhong Min, and Jong Chul Ye. A deep convolutional neural network using directional wavelets for low-dose X-ray CT reconstruction. Medical physics, 44(10):e360–e375, 2017. [CrossRef]

| Slice | MCG | Song | PC-POCS | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Index | SSIM | FSIM | PSNR | SSIM | FSIM | PSNR | SSIM | FSIM | PSNR | |

| 268 | 0.8245 | 0.8948 | 28.0463 | 0.7534 | 0.8494 | 19.3313 | 0.8902 | 0.9544 | 33.7343 | |

| 269 | 0.8185 | 0.8927 | 27.9395 | 0.7598 | 0.8506 | 19.0324 | 0.8952 | 0.9559 | 34.0099 | |

| 270 | 0.8217 | 0.8935 | 28.1502 | 0.7601 | 0.8489 | 19.8642 | 0.8915 | 0.9550 | 33.7837 | |

| 271 | 0.8265 | 0.9006 | 28.5476 | 0.7555 | 0.8466 | 19.2071 | 0.8886 | 0.9524 | 33.8067 | |

| 272 | 0.8193 | 0.8939 | 27.9205 | 0.7509 | 0.8447 | 19.4014 | 0.8882 | 0.9526 | 33.6799 | |

| 273 | 0.8229 | 0.8978 | 28.2543 | 0.7569 | 0.8447 | 21.0755 | 0.8909 | 0.9531 | 33.6392 | |

| 274 | 0.8124 | 0.8886 | 27.4984 | 0.7603 | 0.8446 | 21.1059 | 0.8867 | 0.9529 | 33.4561 | |

| 275 | 0.8168 | 0.8909 | 27.5838 | 0.7659 | 0.8447 | 23.4483 | 0.8880 | 0.9539 | 33.4843 | |

| 276 | 0.8198 | 0.8914 | 27.4239 | 0.7627 | 0.8461 | 24.8852 | 0.8914 | 0.9544 | 33.4510 | |

| 277 | 0.8141 | 0.8901 | 27.2613 | 0.7693 | 0.8460 | 25.2738 | 0.8868 | 0.9522 | 33.0534 | |

| 278 | 0.8255 | 0.8977 | 27.8815 | 0.7695 | 0.8424 | 24.8828 | 0.8862 | 0.9530 | 33.3379 | |

| 279 | 0.8114 | 0.8894 | 27.2112 | 0.7661 | 0.8481 | 21.6348 | 0.8853 | 0.9530 | 33.3544 | |

| 280 | 0.8231 | 0.9005 | 28.0072 | 0.7706 | 0.8499 | 21.5181 | 0.8867 | 0.9544 | 33.5495 | |

| 281 | 0.8228 | 0.9012 | 27.9217 | 0.7138 | 0.8355 | 23.2376 | 0.8921 | 0.9559 | 33.8156 | |

| 282 | 0.8216 | 0.9021 | 28.4271 | 0.7609 | 0.8478 | 22.7803 | 0.8876 | 0.9558 | 33.7879 | |

| 283 | 0.8263 | 0.9069 | 28.5272 | 0.7701 | 0.8483 | 23.2087 | 0.8881 | 0.9553 | 33.8860 | |

| 284 | 0.8239 | 0.9066 | 28.5368 | 0.7629 | 0.8517 | 25.7797 | 0.8889 | 0.9558 | 33.9643 | |

| 285 | 0.8197 | 0.9007 | 28.3875 | 0.7656 | 0.8554 | 23.0487 | 0.8930 | 0.9567 | 34.2841 | |

| 286 | 0.8274 | 0.9095 | 28.9279 | 0.7659 | 0.7865 | 25.6019 | 0.8927 | 0.9596 | 34.5028 | |

| 287 | 0.8316 | 0.9145 | 29.2608 | 0.7707 | 0.8478 | 21.7916 | 0.8950 | 0.9614 | 34.6276 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).