Submitted:

01 November 2025

Posted:

03 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Cellular Involvement of the Neurovascular and Perivascular Unit

2.1. Brain Endothelial Cell(s) (BEC)

2.2. Capillary Neurovascular Unit Pericyte(s) (Pc)

2.3. Perivascular Astrocyte Endfeet (pvACef)

2.4. Perisynaptic Astrocyte Endfeet (psACef)

2.5. Resident Perivascular Macrophages (PVMΦ)

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AC | astrocyte; ACef, astrocyte endfeet; APC(s), antigen presenting cell(s); AQP4, aquaporin-4 water channel; ASD, autism spectrum disorder(s); BBB, blood–brain barrier; BBBact/dys, BBB activation/dysfunction; BBBdd, BBB dysfunction/disruption; BEC(s), brain endothelial cell(s); becGCx, brain endothelial cell glycocalyx; BM, basement membrane; BTBR ob/ob mice, obese hyperphagic, diabetic, brown and tan, brachyuric mice with leptin-deficiency mutation ; CAA, cerebral amyloid angiopathy; CADASIL, cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy; CC 4.0. creative commons 4.0 permission to republish with appropriate references; CL, capillary lumen; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; db/db mice, hyperphagic obese diabetic mouse models homozygous for the diabetes spontaneous mutation of the leptin receptor (Leprdb); EPVS, enlarged perivascular spaces; FOCM, folate one-carbon metabolism; GHS, glutathione; GS, glymphatic system; Hcy, homocysteine, HHCY, hyperhomocysteinemia; iMGC, interrogating microglia cell; IPAD, intramural peri-arterial drainage; ISF, interstitial fluid; ISS, interstitial space(s); LOAD, late-onset Alzheimer’s disease; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; MetS, metabolic syndrome; MRI, magnetic resonance image-imaging; MTHFR, methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene; MVEPVS, MRI visible EPVS; NVU, neurovascular unit; Pc, pericyte; pCC, peripheral cytokines/chemokines; Pcef, pericyte endfeet; Pcfp, pericyte foot process; pvACef, perivascular astrocyte endfeet; psACef, protoplasmic perisynaptic astrocyte endfeet; PVS, perivascular spaces; PVS/EPVS, perivascular space/enlarged perivascular space; rPVMΦ, resident perivascular macrophages; ROS, reactive oxygen species; RTIWH, response to injury wound healing; SAS, subarachnoid space; -SH, thiol group(s); SVD, cerebral small vessel disease; TEM, transmission electron microscopy; TIA(s), transient ischemic attack(s); T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; VaD, vascular dementia; VCID, vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia; WMH, white matter hyperintensities. |

References

- Malatesta, M. Transmission Electron Microscopy as a Powerful Tool to Investigate the Interaction of Nanoparticles with Subcellular Structures. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

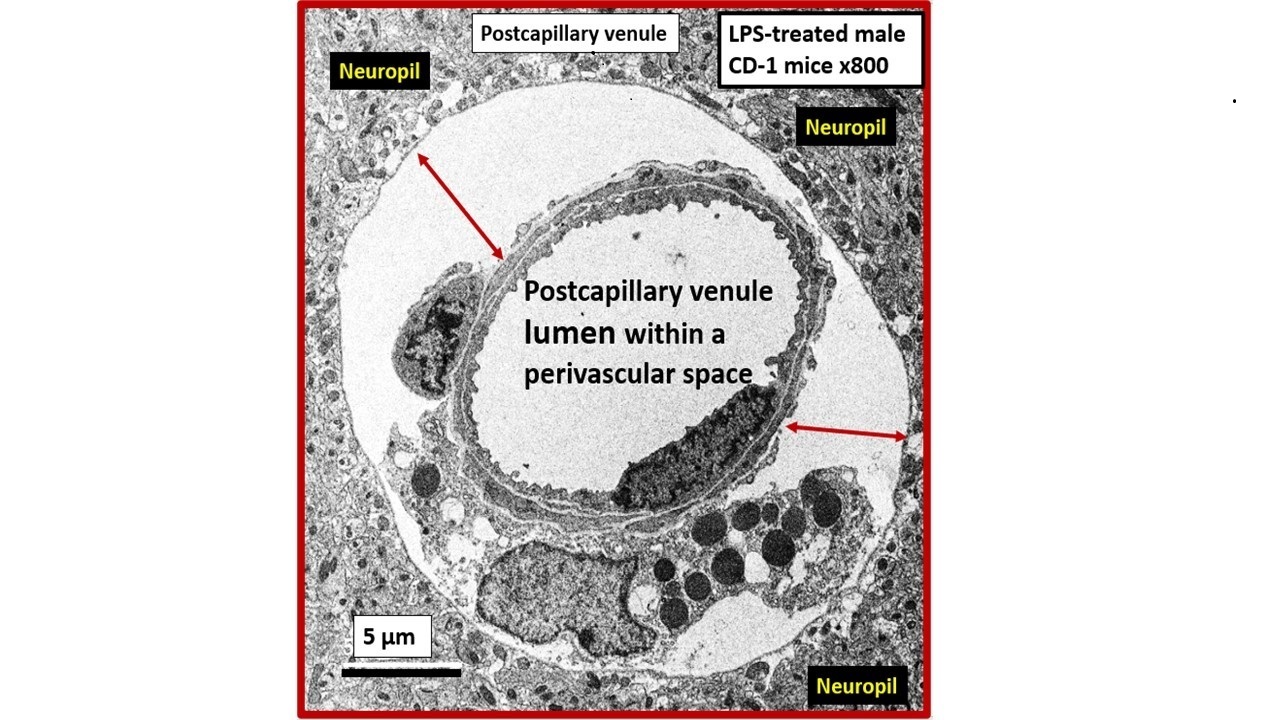

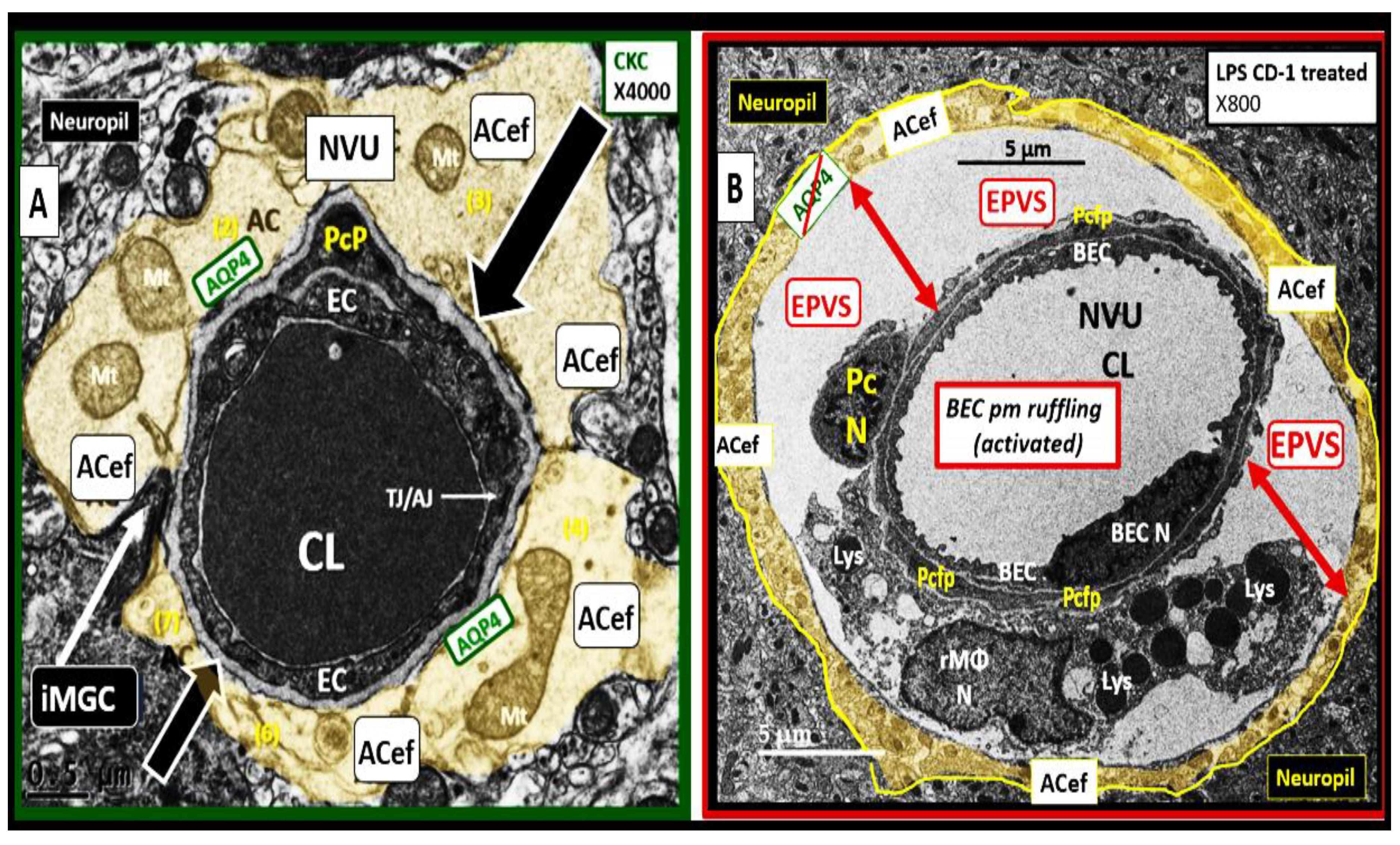

- Erickson, M.A.; Shulyatnikova, T.; Banks, W.A.; Hayden, M.R. Ultrastructural Remodeling of the Blood-Brain Barrier and Neurovascular Unit by Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Neuroinflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

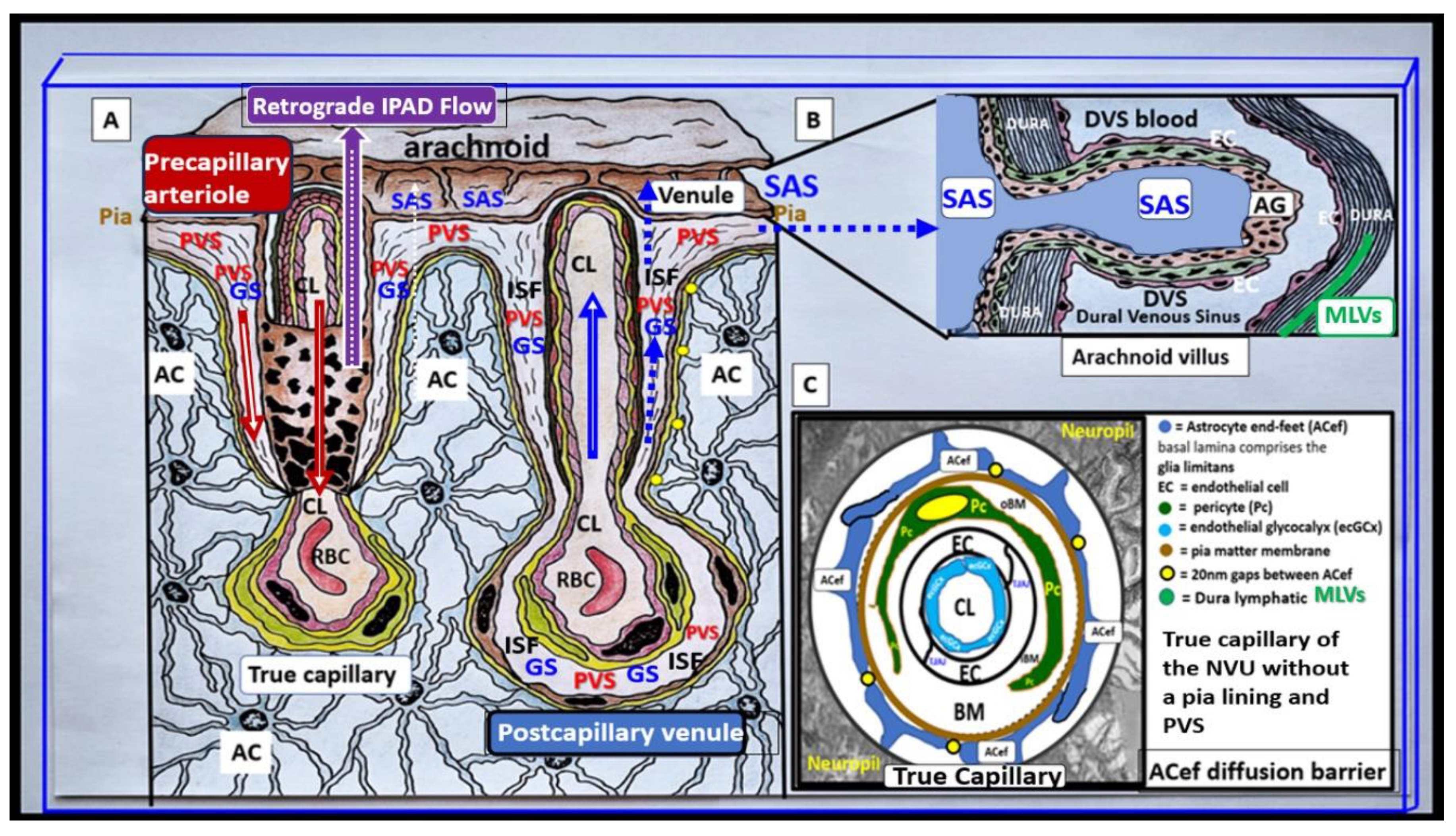

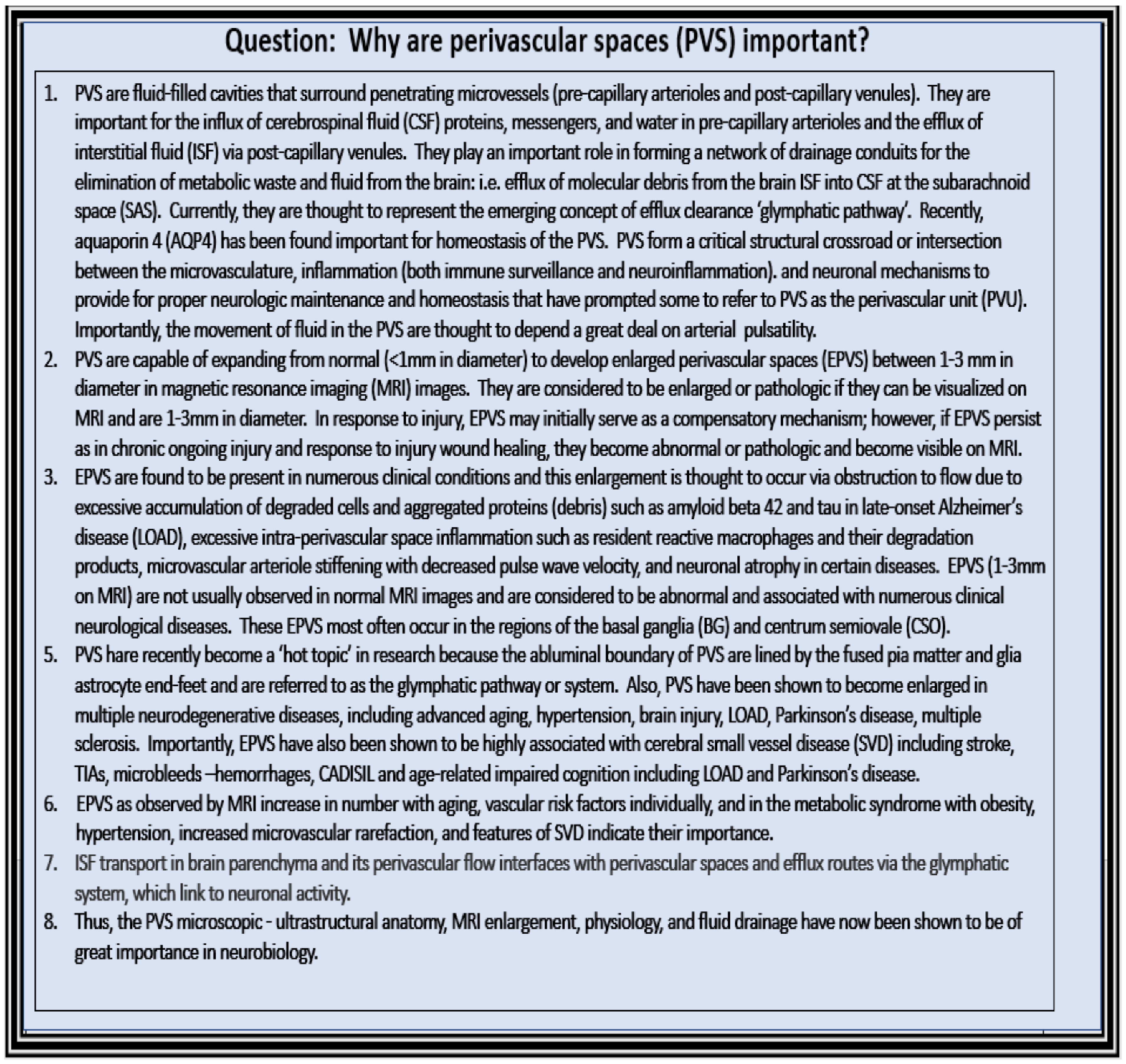

- Shulyatnikova, T.; Hayden, M.R. Why Are Perivascular Spaces Important? Medicina (Kaunas) 2023, 59, 917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnell, H.L.; Kersch, C.N.; Randall, L.; Woltjer, R.L.; Neuwelt, E.A. The Translational Significance of the Neurovascular Unit. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 762–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnell, H.L.; Mishra, A. Cells of the Blood-Brain Barrier: An Overview of the Neurovascular Unit in Health and Disease. Methods Mol. Biol. 2022, 2492, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iadecola, C. Neurovascular regulation in the normal brain and in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2004, 5, 347–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlokovic, B.J. Neurovascular pathways to neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease and other disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2011, 12, 723–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troili, F.; Cipollini, V.; Moci, M.; Morena, E.; Palotai, M.; Rinaldi, V.; et.al., *!!! REPLACE !!!*. Perivascular Unit: This Must Be the Place. The Anatomical Crossroad between the Immune, Vascular and Nervous System. Front. Neuroanat. 2020, 14, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, M.R. A Closer Look at the Perivascular Unit in the Development of Enlarged Perivascular Spaces in Obesity, Metabolic Syndrome, and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Biomedicines. 2024, 12, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, T.; Bechmann, I.; Engelhardt, B. Perivascular spaces and the two steps to neuroinflammation. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2008, 67, 1113–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, W.; Cheng, J.; Tan, Y. Brain perivascular macrophages: Current understanding and future prospects. Brain. 2024, 147, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan, X.; Wang, S.; Bèchet, N.; Gouras, G.; Wen, G. Perivascular macrophages in the central nervous system: Insights into their roles in health and disease. Cell Death Dis. 2025, 16, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, E.T.; Inman, B.E.; Weller, R.O. Interrelationships of the pia mater and the perivascular (Virchow-Robin) spaces in the human cerebrum. J. Anat. 1990, 170, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yu, L.; He, X.; Li, H.; Zhao, Y. Perivascular Spaces, Glymphatic System and MR. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 84493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.; Benveniste, H.; Black, S.E.; Charpak, S.; Dichgans, M.; Joutel, A.; et al. Understanding the role of the perivascular space in cerebral small vessel disease. Cardiovasc. Res. 2018, 114, 1462–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliff, J.J.; Wang, M.; Liao, Y.; Plogg, B.A.; Peng, W.; Gundersen, G.A.; et al. A Paravascular Pathway Facilitates CSF Flow Through the Brain Parenchyma and the Clearance of Interstitial Solutes, Including Amyloid β. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012, 4, 147ra111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliff, J.J.; Lee, H.; Yu, M.; Feng, T.; Logan, J.; Nedergaard, M.; Benveniste, H. Brain-wide pathway for waste clearance captured by contrast-enhanced MRI. J. Clin. Invest. 2013, 123, 1299–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohr, T.; Hjorth, P.G.; Holst, S.C.; Hrabětová, S.; Kiviniemi, V.; Lilius, T.; et al. The glymphatic system: Current understanding and modeling. iScience 2022, 25, 104987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hladky, S.B.; Barrand, M.A. The glymphatic hypothesis: The theory and the evidence. Fluids Barriers CNS. 2022, 19, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Fan, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, M.; Wang, G.; Dong, Y.; Liu, J.; Song, W. The glymphatic system: A new perspective on brain diseases. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2023, 15, 1179988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

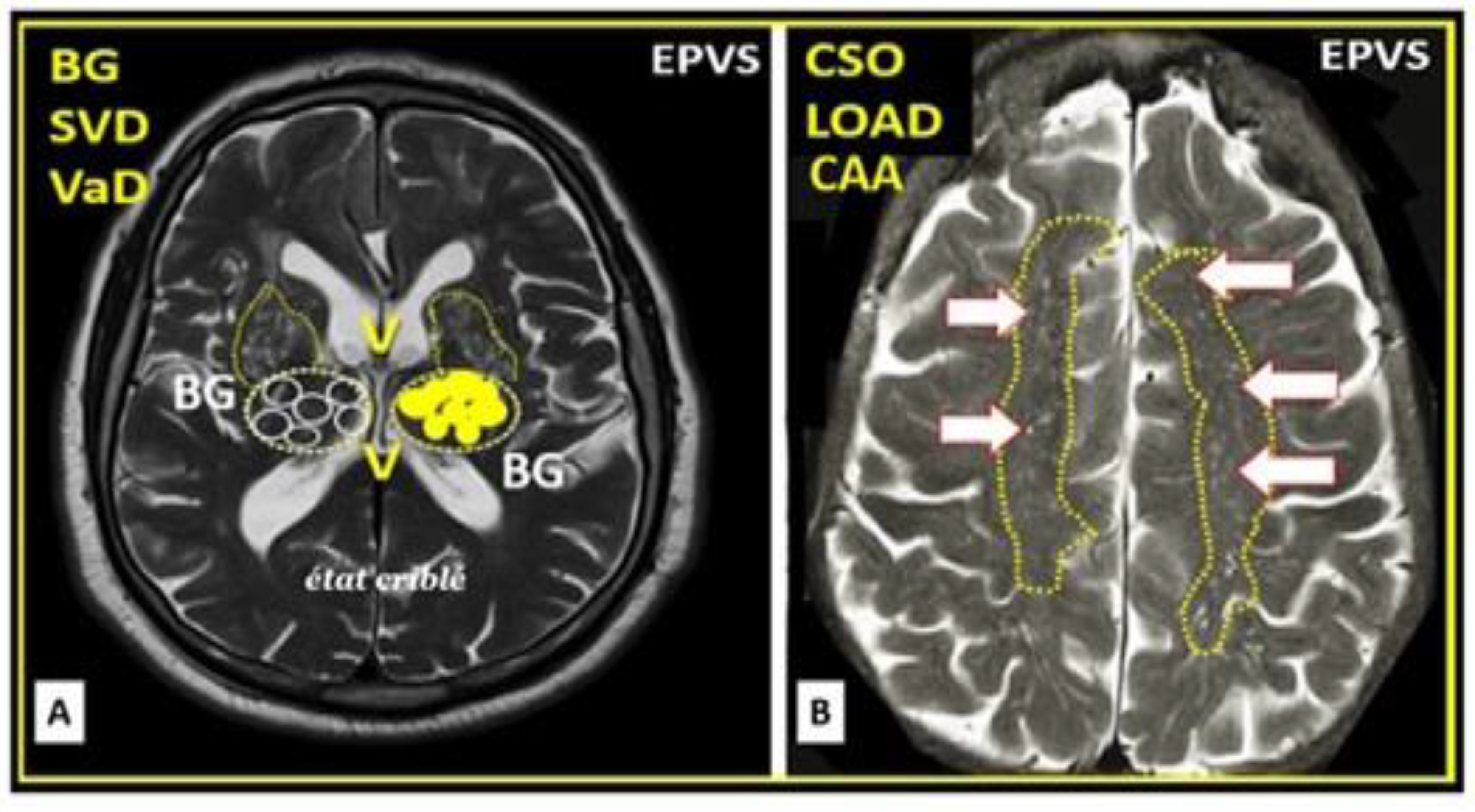

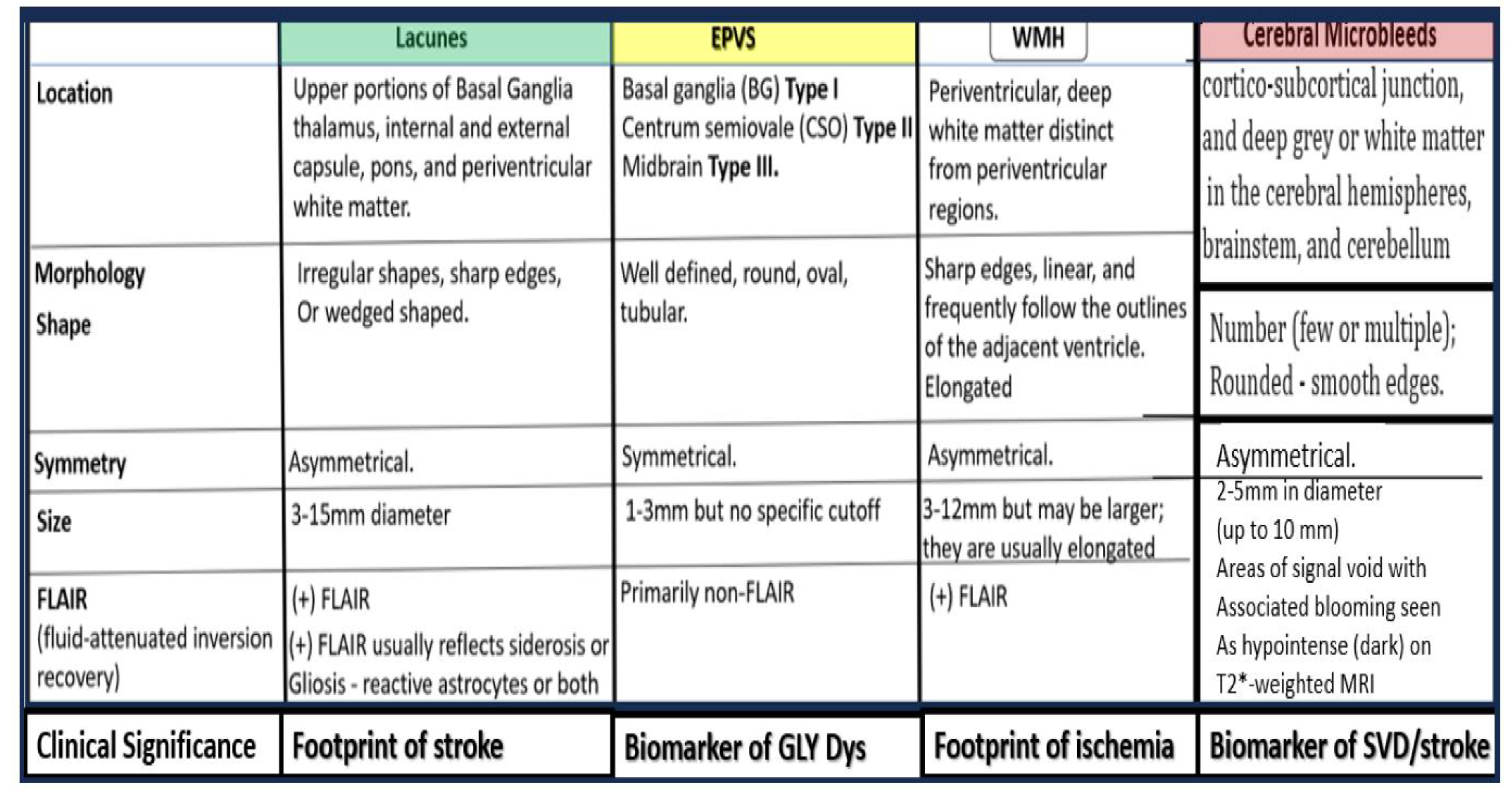

- Wardlaw JM, Smith EE, Biessels GJ, Cordonnier C, Fazekas F, Frayne, R. ; et al. Neuroimaging standards for research into small vessel disease and its contribution to ageing and neurodegeneration. Lancet Neurol. 2023, 22, 602–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, M.; Luan, M.; Song, X.; Wang, Y.; Xu, L.; Zhong, M.; Zheng, X. Enlarged Perivascular Spaces and Age-Related Clinical Diseases. Clin. Interv. Aging. 2023, 18, 855–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heier, L.A.; Bauer, C.J.; Schwartz, L.; Zimmerman, R.D.; Morgello, S.; Deck, M.D. Large Virchow-Robin spaces: MR-clinical correlation. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 1989, 10, 929–936. [Google Scholar]

- Doubal, F.N.; Maclullich, A.M.J.; Ferguson, K.J.; Dennis, M.S.; Wardlaw, J.M. Enlarged Perivascular Spaces on MRI Are a Feature of Cerebral Small Vessel Disease. Stroke. 2010, 41, 450–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, M.D.; Kisler, K.; Montagne, A.; Toga, A.W.; Zlokovic, B.V. The role of brain vasculature in neurodegenerative disorders. Nat. Neurosci. 2018, 21, 1318–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benjamin, P.; Trippier, S.; Lawrence, A.J.; Lambert, C.; Zeestraten, E.; Williams, O.A.; et al. Lacunar Infarcts, but Not Perivascular Spaces, Are Predictors of Cognitive Decline in Cerebral Small-Vessel Disease. Stroke 2018, 49, 586–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arba, F.; Quinn, T.J.; Hankey, G.J.; Lees, K.R.; Wardlaw, J.M.; Ali, M.; Inzitari, D. , on behalf of the VISTA Collaboration. Enlarged perivascular spaces and cognitive impairment after stroke and transient ischemic attack. Int. J. Stroke. 2018, 13, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wardlaw, J.M.; Smith, C.; Dichgans, M. Mechanisms of sporadic cerebral small vessel disease: Insights from neuroimaging. Lancet Neurol. 2013, 12, 483–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bown, C.W.; Carare, R.O.; Schrag, M.S.; Jefferson, A.L. Physiology and Clinical Relevance of Enlarged Perivascular Spaces. Neurology 2022, 98, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, M.R.; Tyagi, N. The Integrity of Perivascular Spaces Is Absolutely Essential for Proper Function of the Glymphatic System Waste and Excess Water Removal from the Brain. Histol Histopathol. 2025, 18952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, M.R. Brain Endothelial Cells Play a Central Role in the Development of Enlarged Perivascular Spaces in the Metabolic Syndrome. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023, 59, 1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erickson, M.A.; Banks, W.A. Transcellular routes of blood-brain barrier disruption. Exp. Biol. Med. 2022, 247, 788–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbott, N.J.; Patabendige, A.A.; Dolman, D.E.; Yusof, S.R.; Begley, D.J. Structure and function of the blood-brain barrier. Neurobiol. Dis. 2010, 37, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banks, W.A. From blood-brain barrier to blood-brain interface: New opportunities for CNS drug delivery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2916, 15, 275–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, M.R. Brain Injury: Response to Injury Wound-Healing Mechanisms and Enlarged Perivascular Spaces in Obesity, Metabolic Syndrome, and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023, 59, 1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, W.A.; Gray, A.M.; Erickson, M.A. Salameh TS, Damodarasamy M; et al. Lipopolysaccharide-induced blood-brain barrier disruption: Roles of cyclooxygenase, oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and elements of the neurovascular unit. J. Neuroinflammation. 2015, 12, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, M.A.; Banks, W.A. Transcellular routes of blood–brain barrier disruption. Exp. Biol. Med. 2022, 247, 788–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, M.A.; Liang, W.S.; Fernandez, E.G.; Bullock, K.M.; Thysell, J.A.; Banks, W.A. Genetics and sex influence peripheral and central innate immune responses and blood-brain barrier integrity. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0205769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Guo, Y.; Zhai, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, W.; Zhu, Z.; Xuan, W.; Li, P. Perivascular macrophages in the CNS: From health to neurovascular diseases. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2022, 28, 1908–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, M.R. The Brain Endothelial Cell Glycocalyx Plays a Crucial Role in the Development of Enlarged Perivascular Spaces in Obesity, Metabolic Syndrome, and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Life 2023, 13, 1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutuzov, N.; Flyvbjerg, H.; Lauritzen, M. Contributions of the glycocalyx, endothelium, and extravascular compartment to the blood–brain barrier. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E9429–E9438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampei, S.; Okada, H.; Tomita, H.; Takada, C.; Suzuki, K.; Kinoshita, T.; et al. Endothelial Glycocalyx Disorders May Be Associated With Extended Inflammation During Endotoxemia in a Diabetic Mouse Model. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 623582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attwell, D.; Mishra, A.; Hall, C.N.; O’Farrell, F.M.; Dalkara, T. What is a pericyte? J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 2016, 36, 451–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalkara, T.; Gursoy-Ozdemir, Y.; Yemisci, M. Brain microvascular pericytes in health and disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2011, 122, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweeney, M.D.; Ayyadurai, S.; Zlokovic, B.V. Pericytes of the neurovascular unit: Key functions and signaling pathways. Nat. Neurosci. 2016, 19, 771–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, E.A.; Bell, R.D.; Zlokovic, B.V. Central nervous system pericytes in health and disease. Nat. Neurosci. 2011, 14, 1398–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalkara, T.; Østergaard, L.; Heusch, G.; Attwell, D. Pericytes in the brain and heart: Functional roles and response to ischaemia and reperfusion. Cardiovasc. Res. 2025, 120, 2336–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, D.; Rustenhoven, J.; Feng, S.; Hurley, D.; ROldfield, R.L.; Bergin, P.S.; et al. +-. J. Neuroinflammation. 2014, 11, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rustenhoven, J.; Jansson, D.; Smyth, L.C.; Dragunow, M. Brain Pericytes As Mediators of Neuroinflammation. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2017, 38, 291–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iadecola, C.; Nedergaard, M. Glial regulation of the cerebral microvasculature. Nat. Neurosci. 2007, 10, 1369–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.N.; Reynell, C.; Gesslein, B.; Hamilton, N.B.; Mishra, A.; Sutherland, B.A.; et al. Capillary pericytes regulate cerebral blood flow in health and disease. Nature 2014, 508, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, M.R.; Yang, Y.; Habibi, J.; Bagree, S.V.; Sowers, J.R. Pericytopathy: Oxidative stress and impaired cellular longevity in the pancreas and skeletal muscle in metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2010, 3, 290–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, E.A.; Sagare, A.P.; Zlokovic, B.V. The Pericyte: A Forgotten Cell Type with Important Implications for Alzheimer’s Disease? Brain Pathol. 2014, 24, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dore-Duffy, P.; Andre Katychev, A.; Xueqian Wang, X.; Van Buren, E. CNS microvascular pericytes exhibit multipotential stem cell activity. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. 2006, 26, 613–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, M.R. Protoplasmic Perivascular Astrocytes Play a Crucial Role in the Development of Enlarged Perivascular Spaces in Obesity, Metabolic Syndrome, and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Neuroglia. 2023, 4, 307–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkhratsky, A.; Butt, A.M. Neuroglia: Function and Pathology, 1st ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Verkhratsky, A.; Nedergaard, M.; Hertz, L. Why are astrocytes important? . Neurochem. Res. 2015, 40, 389–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verkhratsky, A.; Nedergaard, M. Physiology of Astroglia. Physiol. Rev. 2018, 98, 239–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkhratsky, A.; Parpura, V.; Li, B.; Scuderi, C. Astrocytes: The Housekeepers and Guardians of the CNS. Adv. Neurobiol. 2021, 26, 21–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkhratsky, A.; Nedergaard, M. Astroglial cradle in the life of the synapse. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2014, 369, 20130595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szu, J.I.; Binder, D.K. The Role of Astrocytic Aquaporin-4 in Synaptic Plasticity and Learning and Memory. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkhratsky, A.; Bush, N.A.O.; Nedergarrd, M.; Butt, A.M. The Special Case of Human Astrocytes. Neuroglia 2018, 1, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Cui, X.; Zhu, B.; Zhou, L.; Gao, Y.; Lin, T.; Shi, Y. Role of astrocytes in the pathogenesis of perinatal brain injury. Mol. Med. 2025, 31, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, F.; Kasai, A.; Soto, J.S.; Yu, X.; Qu, Z.; Hashimoto, H.; et al. Molecular basis of astrocyte diversity and morphology across the CNS in health and disease. Science 2022, 378, eadc9020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelhardt, B.; Carare, R.O.; Bechmann, I.; Flügel, A.; Laman, J.D.; Weller, R.O. Vascular, glial, and lymphatic immune gateways of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 2016, 132, 317–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.K.; Wang, F.; Wang, W.; Luo, Y.; Wu, P.F.; Jun-Li Xiao, J.L.; et al. Aquaporin-4 deficiency impairs synaptic plasticity and associative fear memory in the lateral amygdala: Involvement of downregulation of glutamate transporter-1 expression. Neuropsychopharmacology 2012, 37, 1867–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagelhus, E.A.; Ottersen, O.P. Physiological roles of aquaporin-4 in brain. Physiol. Rev. 2013, 93, 1543–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazaré, N.; Oudart, M.; Cohen-Salmon, M.; Cohen-Salmon, M. Local translation in perisynaptic and perivascular astrocytic processes - a means to ensure astrocyte molecular and functional polarity? J Cell Sci. 2021, 134, jcs251629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz de León-López, C.A.; Navarro-Lobato, I.; Khan, Z.U. The Role of Astrocytes in Synaptic Dysfunction and Memory Deficits in Alzheimer’s Disease. Biomolecules. 2025, 15, 910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozo, K.; Goda, Y. Unraveling mechanisms of homeostatic synaptic plasticity. Neuron. 2010, 66, 337–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitureira, N.; Letellier, M.; Goda, Y. Homeostatic synaptic plasticity: From single synapses to neural circuits. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2012, 22, 516–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, M.R. Pericytes and Resident Perivascular Macrophages Play a Key Role in the Development of Enlarged Perivascular Spaces in Obesity, Metabolic Syndrome and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. J. Alzheimers Neurodegener. Dis. 2023, 9, 062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, L.; Guo, Y.; Zhai, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, W.; Zhu, Z.; Xuan, W.; Li, P. CNS Perivascular macrophages in the CNS: From health to neurovascular diseases. Neurosci. Ther. 2022, 28, 1908–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, T.; Guo, R.; Zhang, F. Brain perivascular macrophages: Recent advances and implications in health and diseases. CNS Neurosci. 2019, 25, 1318–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ide, S.; Yahara, Y.; Kobayashi, Y.; Strausser, S.A.; Ide, K.; Watwe, A.; et al. Yolk-sac-derived macrophages progressively expand in the mouse kidney with age. eLife 2020, 9, e51756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, X.; Wang, S.; Bèchet, N.; Gouras, G.; Wen, G. Perivascular macrophages in the central nervous system: Insights into their roles in health and disease. Cell Death Dis. 2025, 16, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Saito, T.; Saido, T.C.; Barron, A.M.; Ruedl, C. Microglia and CD206(+) border-associated mouse macrophages maintain their embryonic origin during Alzheimer’s disease. Elife 2021, 10, e71879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frosch, M.; -Amann, L.; Prinz, M. CNS-associated macrophages shape the inflammatory response in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayd, A.; Vargas-Caraveo, A.; Perea-Romero, I.; Robledo-Montana, J.; Caso, J.R.; Madrigal, J.L.M.; et al. Depletion of brain perivascular macrophages regulates acute restraint stress-induced neuroinflammation and oxidative/nitrosative stress in rat frontal cortex. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020, 34, 50–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, N.F.; Velloso, L.A. Perivascular macrophages in high-fat diet-induced hypothalamic inflammation. J. Neuroinflamm. 2022, 19, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedragosa, J.; Salas-Perdomo, A.; Gallizioli, M.; Cugota, R.; Miro-Mur, F.; Brianso, F.; et al. CNS-border associated macrophages respond to acute ischemic stroke attracting granulocytes and promoting vascular leakage. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2018, 6, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraco, G.; Sugiyama, Y.; Lane, D.; Garcia-Bonilla, L.; Chang, H.; Santisteban, M.M.; et al. Perivascular macrophages mediate the neurovascular and cognitive dysfunction associated with hypertension. J. Clin. Invest. 2016, 126, 4674–4689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Jiang, H. Border-associated macrophages in the central nervous system. J. Neuroinflammation. 2024, 21, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vara-Pérez, M.; Movahedi, K. Border-associated macrophages as gatekeepers of brain homeostasis and immunity. Immunity. 2025, 58, 1085–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H. Space and Place: A Daoist Perspective. In The Philosophy of Geography. Springer Geography; Tambassi, T., Tanca, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, 2021; Volume 6, pp. 95–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mestre, H.; Kostrikov, S.; Mehta, R.I.; Nedergaard, M. Perivascular spaces, glymphatic dysfunction, and small vessel disease. Clin Sci (Lond). 2017, 131, 2257–2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, M.K.; Mestre, H.; Nedergaard, M. The glymphatic pathway in neurological disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2018, 17, 1016–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, M.K.; Mestre, H.; Nedergaard, M. Fluid transport in the brain. Physiol. Rev. 2022, 102, 1025–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedergaard, M.; Goldman, S.A. Glymphatic failure as a final common pathway to dementia. Science 2020, 370, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Han, H.; Yuan, F.; Javeed, A.; Zhao, Y. The brain interstitial system: Anatomy, modeling, in vivo measurement, and applications. ProgNeurobiol. 2017, 157, 230–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, M.R.; Grant, D.G.; Aroor, A.R.; DeMarco, V.G. Empagliflozin Ameliorates Type 2 Diabetes-Induced Ultrastructural Remodeling of the Neurovascular Unit and Neuroglia in the Female db/db Mouse. Brain Sci. 2019, 9, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, W.A.; Hayden, M.R. Deficient Leptin Cellular Signaling Plays a Key Role in Brain Ultrastructural Remodeling in Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munis, Ö.B. Association of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus With Perivascular Spaces and Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy in Alzheimer’s Disease: Insights From MRI Imaging. Dement. Neurocogn Disord. 2023, 22, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, T.P.; Cain, J.; Thomas, O.; Jackson, A. Dilated perivascular spaces in the Basal Ganglia are a biomarker of small-vessel disease in a very elderly population with dementia. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2015, 36, 893–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zebarth, J.; Kamal, R.; Perlman, G.; Ouk, M.; Xiong, L.Y.; Yu, D.; Lin, W.Z.; Ramirez, J.; et al. Perivascular spaces mediate a relationship between diabetes and other cerebral small vessel disease markers in cerebrovascular and neurodegenerative diseases. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2023, 32, 107273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Torre, J.C. Cardiovascular risk factors promote brain hypoperfusion leading to cognitive decline and dementia. Cardiovasc. Psychiatry Neurol. 2012, 2012, 367516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, P.; Zhang, D.; Li, J.; Tang, M.; Yan, X.; Zhang, X.; et al. The enlarged perivascular spaces in the hippocampus is associated with memory function in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 3644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayden, M.R.; Tyagi, S.C. Homocysteine and reactive oxygen species in metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and atheroscleropathy: The pleiotropic effects of folate supplementation. Nutr. J. 2004, 3, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayden, M.R.; Tyagi, S.C. Impaired Folate-Mediated One-Carbon Metabolism in Type 2 Diabetes, Late-Onset Alzheimer’s Disease and Long COVID. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021, 58, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, M.J.; Liu, Z.G. Crosstalk of reactive oxygen species and NF-κB signaling. Cell Res. 2010, 21, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, U.; Banerjee, P.; Bir, A.; Sinha, M.; Biswas, A.; Chakrabarti, S. Reactive oxygen species, redox signaling and neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease: The NF-κB connection. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2015, 15, 446–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordaro, M.; Siracusa, R.; Fusco, R.; Cuzzocrea, S.; Paola, R.D.; Impellizzeri, D. Involvements of Hyperhomocysteinemia in Neurological Disorders. Metabolites. 2021, 11, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, M.F.; Sullivan, L.M.; D’Agostino, R.B.; Elias, P.K.; Paul, F. Jacques PF, Selhub J; et al. Homocysteine and Cognitive Performance in the Framingham Offspring Study: Age Is Important. Stroke 2004, 35, 404–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCully, K.S. Vascular pathology of homocysteinemia: Implications for the pathogenesis of arteriosclerosis. Am. J. Pathol. 1969, 56, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stampfer, M.J.; Malinow, M.R.; Willett, W.C.; Newcomer, L.; Upson, B.; Ullmann, D.; Tishler, P. ; Hennekens CH: Aprospective study of plasma homocyst(e)ine risk of myocardial infarction in USphysicians. JAMA 1992, 268, 877–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnesen, E.; Refsum, H.; Bonaa, K.H.; Ueland, P.M.; Forde, O.H.; Nordrehaug, J.E. Serum total homocysteine and coronary heart disease. Int. J. Epidemiol. 1995, 24, 704–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boushey, C.J.; Beresford, S.A.; Omenn, G.S. ; Motulsky AG: Aquantitative assessment of plasma homocysteine as a risk factor for vascular disease Probable benefits of increasing folic acid intakes. JAMA 1995, 274, 1049–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, I.M.; Daly, L.E.; Refsum, H.M.; Robinson, K.; Brattstrom, L.E. ; Ueland PM: Plasma homocysteine as a risk factor for vascular disease The European Concerted Action Project. JAMA 1997, 277, 1775–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wald, N.J.; Watt, H.C.; Law, M.R.; Weir, D.G.; McPartlin, J.; Scott, J.M. Homocysteine and ischemic heart disease: Results of a prospective study with implications regarding prevention. Arch. Intern. Med. 1998, 158, 862–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogeveen, E.K.; Kostense, P.J.; Beks, P.J.; Mackaay, A.J.; Jakobs, C.; Bouter, L.M.; Heine, R.J.; Stehouwer, C.D. Hyperhomocysteinemia is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, especially in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: A population-based study. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1998, 18, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, G.N.; Loscalzo, J. Homocysteine and atherothrombosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998, 338, 1042–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stehouwer, C.D.; Weijenberg, M.P.; van den Berg, M.; Jakobs, C.; Feskens, E.J.; Kromhout, D. Serum homocysteine and risk of coronary heart disease and cerebrovascular disease in elderly men: A 10-year follow-up. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998, 18, 1895–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boers, G.H. Mild hyperhomocysteinemia is an independent risk factor of arterial vascular disease. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2000, 26, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinzon, R.T.; Wijaya, V.O.; Veronica, V. The role of homocysteine levels as a risk factor of ischemic stroke events: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1144584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, A.D.; Refsum, H.; Bottiglieri, T.; Fenech, M.; Hooshmand, B.; McCaddon, A.; et al. Homocysteine and Dementia: An International Consensus Statement. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2018, 62, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuo, J.M.; Wang, H.; Pratico, D. Is hyperhomocysteinemia an Alzheimer’s disease (AD) risk factor, an AD marker, or neither? Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2011, 32, 562–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L. Homocysteine and Parkinson’s disease. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2023, 30, e14420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustafa, A.A.; Hewedi, D.H.; Eissa, A.M.; Frydecka, D.; Misiak, B. Homocysteine levels in schizophrenia and affective disorders—Focus on cognition. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldelli, E.; Leo, G.; Andreoli, N.; Fuxe, K.; Biagini, G.; Luigi FAgnati, L.F. Homocysteine potentiates seizures and cell loss induced by pilocarpine treatment. Neuromolecular Med. 2010, 12, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Xu, Y.; Pang, D.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, L.; Li, M.; Li, W.; Duan, G.; Zhu, C. Interrelation between homocysteine metabolism and the development of autism spectrum disorder in children. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2022, 15, 947513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garic, D.; McKinstry, R.C.; Rutsohn, J.; Slomowitz, R.; Wolff, J.; MacIntyre, L.C.; et al. Enlarged Perivascular Spaces in Infancy and Autism Diagnosis, Cerebrospinal Fluid Volume, and Later Sleep Problems. JAMA Netw. Open. 2023, 6, e2348341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Wang, L.; Liu, W.; Wu, Y.; Yuan, Z. The synergistic effect of homocysteine and lipopolysaccharide on the differentiation and conversion of raw264.7 macrophages. 7 macrophages. J Inflamm (Lond). 2014, 11, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessen, N.A.; Munk, A.S.; Lundgaard, I.; Nedergaard, M. The Glymphatic System: A beginner’s guide. Neurochem. Res. 2015, 40, 2583–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Thrippleton, M.J.; Blair, G.W.; Dickie, D.A.; Marshall, I.; Hamilton, I.; et al. Small vessel disease is associated with altered cerebrovascular pulsatility but not resting cerebral blood flow. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 2020, 40, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mestre, H.; Tithof, J.; Du, T.; Song, W.; Peng, W.; Sweeney, A.M.; et al. Flow of cerebrospinal fluid is driven by arterial pulsations and is reduced in hypertension. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dreha-Kulaczewski, S.; Joseph, A.A.; Merboldt, K.D.; Ludwig, H.C.; Gärtner, J.; Frahm, J. Identification of the upward movement of human CSF in vivo and its relation to the brain venous system. J. Neurosci. 2017, 37, 2395–2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Kang, H.; Xu, Q.; Chen, M.J.; Liao, Y.; Thiyagarajan, M.; et al. Sleep drives metabolite clearance from the adult brain. Science 2013, 342, 373–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hablitz, L.M.; Plá, V.; Giannetto, M.; Vinitsky, H.S.; Stæger, F.F.; Metcalfe, T.; et al. Circadian control of brain glymphatic and lymphatic fluid flow. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazaré, N.; Oudart, M.; Moulard, J.; Cheung, G.; Tortuyaux, R.; Mailly, P.; et al. Local Translation in Perisynaptic Astrocytic Processes Is Specific and Changes after Fear Conditioning. Cell Rep. 2020, 32, 108076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colón-Ramos, D.A. Synapse formation in developing neural circuits. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 2009, 87, 53–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Südhof, T.C.; Malenka, R.C. Understanding Synapses: Past, Present, and Future. Neuron. 2008, 60, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecker, C.; Suckling, J.; Deoni, S.C.; Lombardo, M.V.; Bullmore, E.T.; Baron-Cohen, S.; et al. Brain anatomy and its relationship to behavior in adults with autism spectrum disorder: A multicenter magnetic resonance imaging study. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2012, 69, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaak, I.; Brouns, M.R.; Van de Bor, M. The dynamics of autism spectrum disorders: How neurotoxic compounds and neurotransmitters interact. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 2013, 10, 3384–3408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauritsen, M.B. Autism spectrum disorders. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2013, 22, S37–S42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garic, D.; McKinstry, R.C.; Rutsohn, J.; Slomowitz, R.; Wolff, J.; MacIntyre, L.C.; et al. Enlarged Perivascular Spaces in Infancy and Autism Diagnosis, Cerebrospinal Fluid Volume, and Later Sleep Problems. JAMA Netw. Open. 2023, 6, e2348341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotgiu, M.A.; Jacono, L.A.; Barisano, G.; Saderi, L.; Cavassa, V.; Montella, A.; Crivelli, P.; Carta, A.; Sotgiu, S. Brain perivascular spaces and autism: Clinical and pathogenic implications from an innovative volumetric MRI study. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1205489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Castro, V.; Valdes-Hernandez, M.D.C.; Chappell, F.; Armitage, P.A.; Makin, S.; Wardlaw, J.M. Reliability of an automatic classifier for brain enlarged perivascular spaces burden and comparison with human performance. Clin. Sci. 2017, 131, 1465–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeidan, J.; Fombonne, E.; Scorah, J.; Ibrahim, A.; Durkin, M.S.; Saxena, S.; et al. Global prevalence of autism: A systematic review update. Autism Res. 2022, 15, 778–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frye, R.E.; Rossignol, D.A.; Scahill, L.; McDougle, C.J.; Huberman, H.; Quadros, E.V. Treatment of Folate Metabolism Abnormalities in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Semin. Pediatr. Neurol. 2020, 35, 100835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattson, M.P.; Shea, T.B. Folate and homocysteine metabolism in neural plasticity and neurodegenerative disorders. Trends Neurosci. 2003, 26, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen Kadosh, K.; Muhardi, L.; Parikh, P.; Basso, M.; Jan Mohamed, H.J.; Prawitasari, T.; et al. Nutritional Support of Neurodevelopment and Cognitive Function in Infants and Young Children—An Update and Novel Insights. Nutrients 2021, 13, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korsmo, H.W.; Jiang, X. One Carbon Metabolism and Early Development: A Diet-Dependent Destiny. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 32, 579–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homocysteine Lowering Trialists’ Collaboration Lowering blood homocysteine with folic acid based supplements: Meta-analysis of randomised trials Homocysteine Lowering Trialists’ Collaboration. BMJ 1998, 316, 894–898. [CrossRef]

- Ramaekers, V.T.; Rothenberg, S.P.; JSequeira, J.M.; Opladen, T.; Blau, N.; Quadros, E.V.; Selhub, J. Autoantibodies to folate receptors in the cerebral folate deficiency syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 1985–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beversdorf, D.Q.; Anagnostou, E.; Hardan, A.; Wang, P.; Erickson, C.A.; Frazier, T.W.; Veenstra-VanderWeele, J. Editorial: Precision medicine approaches for heterogeneous conditions such as autism spectrum disorders (The need for a biomarker exploration phase in clinical trials - Phase 2m). Front. Psychiatry 2023, 13, 1079006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).