1. Introduction

The challenge of balancing maximizing grain yield, achieving socioeconomic returns, and ensuring environmental preservation is a significant challenge for modern agriculture. In this context, proper crop fertilization management is crucial for ensuring the sustainability of agricultural systems and optimizing the use of natural resources [

1]. Phosphorus (P) deficiency is one of the primary factors limiting productivity on a global scale, affecting approximately 80% of Tropical America area [

2], and 75% of Brazilian soils [

3]. It is one of the most critical constraints to biological nitrogen fixation (BNF), as this nutrient is essential for the bioenergetic processes sustaining the symbiosis between legumes and rhizobia.

The application of phosphate fertilizers is indispensable due to the limited availability of P in the soil solution and its high fixation to colloids, and it is considered a fundamental measure to optimize crop growth and productivity [

4]. Therefore, an adequate amount of phosphorus is a crucial factor in a complex process, supporting cellular mechanisms of BNF [

5], improving agronomic performance, and ultimately strengthening resilient agricultural strategies against challenges posed by highly weathered tropical soils [

6]. Phosphorus deficiency hampers ATP production in nodules and decreases the specific activity of nitrogenase, affecting everything from the reduction of atmospheric N

2 in bacteroids to the assimilation of NH₄⁺ into amino acids and ureides in plants [

7]. This physiological limitation limits the crop’s ability to reach its full potential in agricultural systems that depend on BNF rather than synthetic nitrogen fertilizers.

In this context, cowpea (

Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp.) stands out as a strategic crop, serving not only as a staple food in the tropics but also as a model of efficient symbiotic relationships with Bradyrhizobium. This association promotes agricultural productivity, decreases reliance on nitrogen inputs, and supports socioeconomic sustainability [

8]. The recent expansion of cowpea cultivation into the Brazilian Cerrado—previously confined to the North and Northeast regions [

9]—represents a key agricultural frontier, with a production surplus of 38,271.7 tons, compared to significant deficits in the North (17,576.7 t) and Northeast (102,281.3 t).

Despite its importance for agricultural production, inefficient phosphorus management in tropical soils—such as those of Brazil, which have a high nutrient fixation capacity [

2,

3]—creates a contradiction. On the one hand, the average global cowpea productivity remains low (461.8 kg ha⁻

1), limited by highly weathered, acidic soils with high aluminum saturation, which necessitate the use of amendments and fertilizers. On the other hand, applying phosphorus rates above the critical level without optimized management does not result in significant productivity gains. Still, it contributes to nutrient accumulation in the soil, thereby increasing the risk of losses through adsorption, runoff, and percolation.

As has historically occurred with soybeans in the Cerrado, the consolidation of a robust body of scientific evidence on cowpea's nutritional requirements can redefine its position within the contemporary agri-food system. Beyond phosphorus supply, understanding the role of micronutrients such as cobalt and molybdenum is crucial for enhancing symbiosis with bacteria of the genus

Bradyrhizobium and sustaining the efficiency of BNF. Micronutrient deficiency is as detrimental as the lack of macronutrients (N, K, and P), primarily because it directly affects nitrogen metabolism [

10]. Molybdenum is essential for the synthesis and activation of nitrate reductase, which regulates the assimilation of nitrogen into essential organic compounds [

11]. Cobalt, as a central constituent of vitamin B₁

2, ensures the functional integrity of nitrogenase, preventing its inactivation and consequently maintaining the energy flow that converts atmospheric N

2 into forms assimilable by the plant [

12].

Understanding how different doses of phosphorus, cobalt, and molybdenum, combined with diazotrophic bacteria, influence plant morphophysiological attributes—such as stem diameter, dry matter accumulation, and, above all, nodulation in legumes—is crucial for tropical agriculture. This approach not only optimizes phosphorus use efficiency in highly acidic, weathered environments but also establishes a strategic synergy between macronutrients and micronutrients, potentially transforming cowpea into a model crop with reduced dependence on external inputs.

In a scenario of growing food demand and climate urgency, the development of integrated management strategies in the Brazilian Cerrado that combine high productivity with the maintenance of soil fertility represents a viable solution for optimizing resource use and reducing global pressure on fossil-based nitrogen fertilizers. By demonstrating the potential of cowpea as a key component for enhancing food security and mitigating emissions, this study contributes to the global sustainability agenda. It advances the frontiers of tropical agriculture within the context of rational resource use.

Therefore, the objective of this study was to determine the optimal levels of P, Co, and Mo for optimizing nodulation, growth, and development of cowpea plants in soils representative of the Cerrado region of Mato Grosso, Brazil.

2. Results

2.1. Determination of the Appropriate Phosphorus Dose

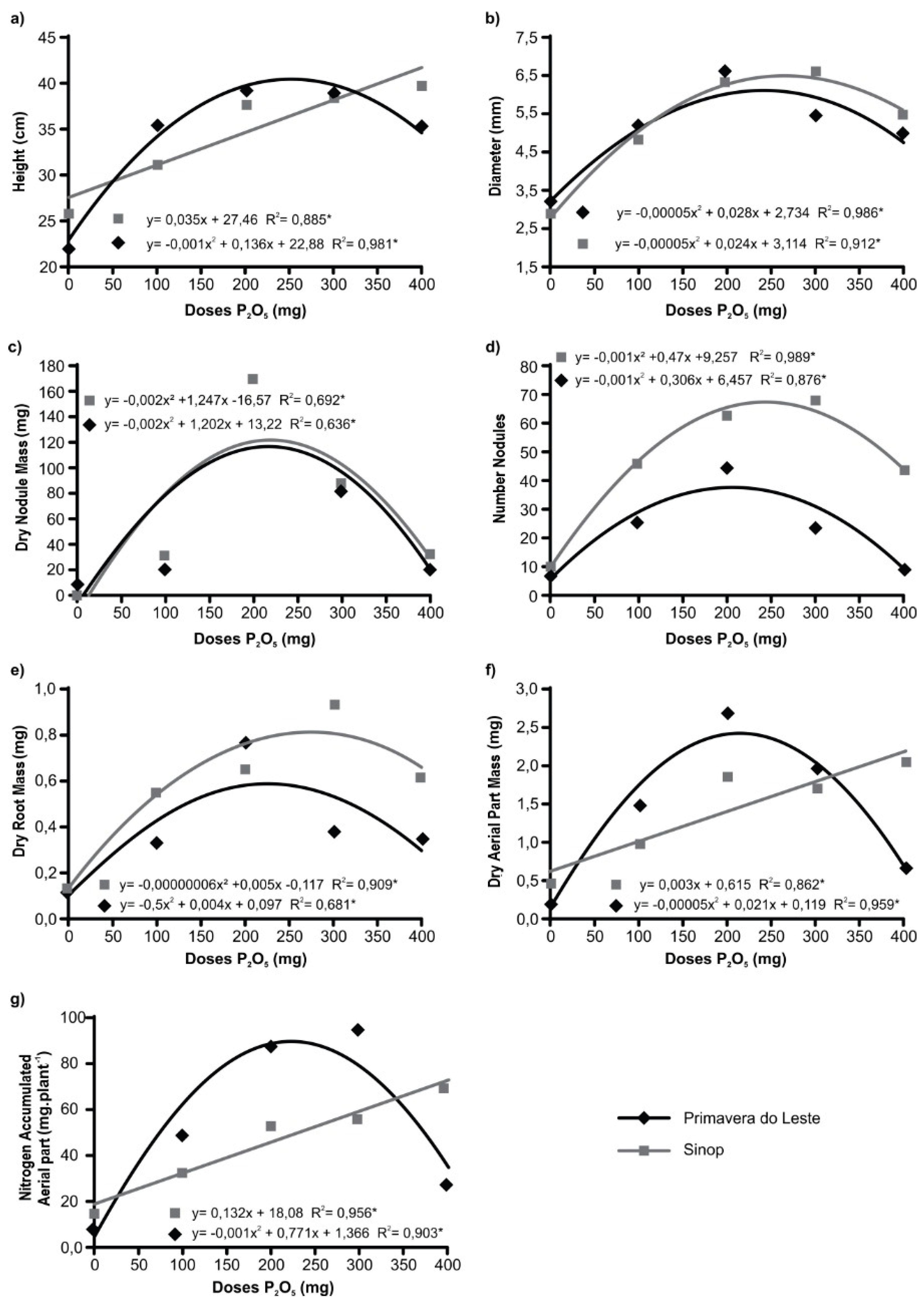

Phosphate fertilization had a significant influence on the analyzed variables. For plant height (

Figure 1a), the adjusted function showed the best results when doses of 200 mg·pot⁻

1 and 400 mg·pot⁻

1 of P

2O

5 were applied, corresponding to maximum values of 39.10 cm and 39.73 cm in the soils of Primavera do Leste (PL) and Sinop (S), respectively. The lowest value was observed when no P

2O

5 was applied.

The model that best described the behaviour of the stem diameter variable (b) as a function of P doses was the quadratic model for both soils (

Figure 1b). The best result for plants grown in Primavera do Leste was obtained when a dose of 200 mg pot⁻

1 of P

2O

5 was incorporated into the soil, corresponding to a stem diameter of 6.4 mm. In the Sinop soil, the best result was obtained with a dose of 300 mg P

2O

5 per pot, resulting in a stem diameter of 6.55 mm.

Regarding the average dry nodule mass production (MNS) (

Figure 1c), the highest technical efficiency for both soils was achieved with the incorporation of a dose of 200 mg vase⁻

1 of P

2O

5, corresponding to 170 mg of nodules per plant. In terms of the number of nodules, there was a significant increase up to the dose of 200 mg vase⁻

1 of P

2O

5 in the Sinop soil, while for the Primavera do Leste soil, this number increased up to 300 mg vase⁻

1 of P

2O

5 (

Figure 1d).

Regarding dry root mass (

Figure 1e), the highest value for the Primavera do Leste (PL) soil was observed with the incorporation of a dose of 200 mg vase⁻

1 of P

2O

5, corresponding to 0.77 g. For the Sinop soil, the maximum production was 0.93 g at a dose of 300 mg P

2O

5 vase⁻

1.

For dry aerial part mass (DAM), the maximum yield (

Figure 1f) for the Primavera do Leste (PL) soil occurred with the incorporation of an average dose of 200 mg plant⁻

1, corresponding to 2.65 g. In the Sinop soil, the highest value was 2.02 g at a dose of 400 mg plant⁻

1. For plants grown in the Sinop soil, the optimal dose was equivalent to 400 kg ha⁻

1; however, the increase in DAM from the average dose (equivalent to 200 kg ha⁻

1) to the highest dose was only 9.9% (0.2 g).

For total nitrogen content (

Figure 1g), the highest value for the Primavera do Leste (PL) soil was observed with the incorporation of a dose of 300 mg vase⁻

1 of P

2O

5, corresponding to 93.42 mg. For the Sinop soil, the highest value was 68.98 mg, at the highest dose (400 mg plant⁻

1). This result indicates that not only did the nodule mass or number increase, but the efficiency of biological nitrogen fixation (BNF) also improved.

The DAM and accumulated nitrogen (N) curves for the Sinop soil exhibited similar behavior, where greater DAM production corresponded to higher nitrogen accumulation.

2.2. Test II: Effect of Cobalt and Molybdenum on the Development of Cowpea Plants

Table 1 shows that the most significant plant height was achieved when a dose equivalent to 64 g ha⁻

1 of Mo and 6 g ha⁻

1 of Co was added to the soil, resulting in 40.31 cm in the PL soil and 48.09 cm in the Sinop soil. This indicates that applying a 6:64 ratio of cobalt and molybdenum (Co–Mo) significantly affected plant height, increasing it by approximately 9 cm in the Sinop soil.

For stem diameter, adding cobalt and molybdenum was not beneficial, as both soils showed a significant decrease in plant diameter at the highest doses.

The treatment with the 4:32 dose promoted nodulation (115 and 118 nodules) for Sinop and Primavera do Leste, respectively. When comparing the phosphorus values at the dose with the best performance for nodulation (200 mg of P2O5), the number of nodules (NN) was 63 and 45 per plant for the soils of Sinop and Primavera do Leste, respectively. This represents an increase of almost double the number of nodules in the Sinop soil and nearly triple in the Primavera do Leste soil. In contrast, the Co–Mo treatments produced more than twice the number of nodules observed in the experiment to determine the P dose; however, the nodules were small and still in the process of development.

For the dry aerial part mass (DAP) variable, the largest mass was observed when a medium dose (16 mg.vase-1 of molybdenum and 3 mg.vase-1 of cobalt) was incorporated into the soil, corresponding to 5.11 g per plant, in the Primavera do Leste (PL) soil, and 4.16 g in the Sinop soil. At the higher dose (64 mg vase-1 of molybdenum and 6 mg vase-1 of cobalt), the values were 4.83 g in the PL soil and 3.8 g in the Sinop soil.

For the dry root mass (DRM) variable, the highest value was recorded in plants grown in the PL soil with the incorporation of a low dose (equivalent to 8 g ha⁻1 of molybdenum and 2 g ha⁻1 of cobalt), corresponding to 2.39 g in the PL soil and 1.13 g in the Sinop soil. When evaluating the accumulated nitrogen content in the aerial part, the most significant result was obtained with the incorporation of a medium dose (equivalent to 16 g ha⁻1 of molybdenum and 3 g ha⁻1 of cobalt) into the soil, corresponding to 120 mg of accumulated N in the PL soil and 86.7 mg in the Sinop soil.

The maximum total N content (120.55 mg) at the medium dose was higher than that of the control treatment, which did not include the addition of Co–Mo, presenting a value of 78.25 mg of N. This represents a 54% increase compared with the control.

3. Discussion

3.1. Determination of the Appropriate Phosphorus Dose

Regarding the influence of phosphate fertilization on the variables analyzed to determine the appropriate phosphorus dose, the results are consistent with other studies that observed lower cowpea height at a dose of 0 kg P

2O

5, confirming that phosphorus deficiency is a nutritional factor limiting crop growth, especially in the Oxisol soils used in this study [

13].

In another study [

14], it was concluded that height and diameter, when analyzed together, represent the most relevant morphological variables for assessing the quality of forest seedlings. It was also inferred that seedlings with a larger stem diameter show a better balance in shoot growth, corroborating studies that identify plant height as an essential indicator for evaluating crop quality, development, and growth dynamics [

15].

The quadratic model for both soils, represented in

Figure 1b, as a function of P doses, showed that the application of 200 mg pot⁻

1 of P

2O

5 in the Primavera do Leste soil had a significant effect on stem diameter at 35 days after germination (DAG). This greater diameter resulted in a higher dry shoot mass, consistent with findings from a previous study that obtained similar results using localized phosphorus application [

15].

The values for nodule number and dry nodule mass (

Figure 1c) indicate adequate nodulation for cowpea [

16,

17]. However, it is important to note, that although the maximum value recorded for the NN variable in the PL soil corresponds to a dose of 300 mg vase⁻

1 of P (68 nodules per plant on average), the addition of a further 100 kg ha⁻

1 of P

2O

5, resulting in an average increase of only five nodules (7.3%), would probably be economically unfeasible, as plants with at least 15 nodules and a nodule mass of around 100 mg per plant represent a satisfactory nodulation condition [

17]. A comparison between

Figure 1c and 1d shows that, when considering the treatments without P application and with the 200 mg vase⁻

1 dose, there was an approximately 30-fold increase in nodule mass and at least a fourfold increase in the number of nodules, demonstrating that soil P deficiency contributed to poor plant nodulation. Phosphorus deficiency was therefore a limiting factor for nodulation, as it is highly required during the initiation and growth phases (affecting nodule number, size, and mass) [

18,

19].

In another study [

20], the results also indicated that a limited supply of phosphorus hinders the development and nodulation of common beans. In plants with phosphorus deficiency, biological nitrogen fixation (BNF) can be directly affected, as inorganic phosphate (Pi) enhances symbiotic N

2 fixation by promoting the growth of the host plant. Consequently, phosphorus deficiency compromises the functioning and development of nodules and rhizobia [

21].

Regarding dry root mass (e), plants supplied with 200 mg P2O5 exhibited greater root length and density, indicating higher efficiency in water absorption and mobilization in deeper soil layers. This characteristic may also contribute to the nutrient supply in surface layers through root decomposition.

According to another study [

22], the application of adequate phosphorus (P) doses from the early stages of plant growth stimulates root development, which is vital for the formation of reproductive primordia and essential for proper grain development, thereby contributing to increased productivity. Similarly, it was observed that seedlings with a more developed root system showed greater growth gains after planting [

23]. These findings reinforce that an adequate P supply promotes root system expansion, enhancing water and nutrient uptake and, consequently, overall plant performance.

The application of phosphorus doses combined with inoculation increased the MPAS of plants grown in Sinop soil. This result confirms the low phosphorus concentration in the soil solution of the Cerrado region, which is attributed to the high nutrient fixation capacity of clays and iron and aluminum oxides [

24,

25]. The appropriate phosphorus dose promoted better plant nutrition and greater biomass production, demonstrating the crop’s dual suitability for use as green manure.

The phosphate adsorption process onto the soil mineral matrix occurs primarily within the clay-sized particle fraction, due to the significant increase in specific surface area and charge density of soil minerals as particle size decreases. The clay fraction primarily consists of phyllosilicate clay minerals, including kaolinite, smectite, and vermiculite, as well as iron and aluminum oxides formed during pedogenic processes. These minerals contain functional groups that are highly reactive to phosphate molecules, which explains the wide variation in adsorption and desorption patterns among different soils [

26,

27].

In the present study, it was observed that in Sinop soil, which has a texture containing 19% clay, the response was linear for plant height, MSPA, and accumulated nitrogen, indicating a lower phosphorus adsorption rate. In contrast, in the Primavera do Leste soil, which contains 42% clay, increasing the dose did not produce a linear response for these variables. This may be attributed to greater phosphorus immobilization by the clay fraction.

Regarding the increase in MPAS at the average dose (equivalent to 200 kg ha⁻1) for plants grown in the Sinop soil, the increase was only 9.9% (0.2 g) at the highest dose. It is believed that this increase would not be economically viable, warranting further investigation.

Similar results were reported in a study [

28], which observed an increase in soybean shoot dry mass (SDM) in response to phosphorus doses, with the 150 kg ha⁻

1 dose being the most efficient. Thus, the findings of the present study reinforce that phosphate fertilization plays a decisive role in the development of cowpea; however, determining the optimal dose must consider not only the plant’s physiological response but also the cost–benefit ratio of the agricultural practice.

3.2. Test II: Effect of Cobalt and Molybdenum on the Development of Cowpea Plants

Regarding stem diameter, it was observed that higher doses of cobalt and molybdenum appeared to cause toxic effects, particularly those associated with cobalt. In this context, a 2005 study reported that the application of this micronutrient to seeds did not alter nitrogen nutrition but was toxic to soybeans at doses above 3.4 g ha⁻

1 [

29]. Similarly, it was found that cobalt concentrations in the nutrient solution, even as low as 0.1 mg kg⁻

1, can produce adverse effects on plant growth [

3].

However, it is worth noting that the reduction in stem diameter was not necessarily detrimental, considering that the stem is a lignified structure. Therefore, directing photoassimilates towards the formation of shoot biomass rather than stem thickening may provide greater benefits to plant development.

The results also indicated a significant increase in the number of nodules—almost double in Sinop and nearly triple in Primavera do Leste—under the 4:32 treatment. This finding demonstrates the positive effect of molybdenum on nodulation, suggesting that the Co–Mo combination contributes to a more efficient nitrogen fixation process. Nevertheless, the interval between application and sampling (20 to 35 days) may have limited the full expression of this effect, since cowpea nodulation begins between 8 and 10 days after plant emergence. Applications made before 25 days may therefore be decisive for accurately evaluating the size, number, and mass of nodules [

30].

Another factor to consider is the relatively high organic matter content of the evaluated soils (6.4% in Primavera do Leste and 5.4% in Sinop), which likely reduced the plants’ dependence on BNF, as the available nutrients in the soil were widely utilized.

Previous studies support these findings. Researchers have reported an increase in the number of nodules with the application of molybdenum, as well as a positive effect of cobalt addition on nodulation [

31]. Similarly, in a related study evaluating different Co and Mo doses, a significant difference was observed among treatments in the number of nodules per plant [

32]. Another study [

33] also reported an increase in nodulation and BNF in legumes following cobalt application. Furthermore, other authors have noted that nodule dry mass is directly correlated with nodulation efficiency, with soybean plants containing 100 to 200 mg of nodule dry mass per plant being associated with higher levels of fixed nitrogen [

34,

35].

4. Materials and Methods

The soils used in the experiment were collected from the municipalities of Sinop and Primavera do Leste, both located in the state of Mato Grosso, in areas with no previous history of cultivation. In Sinop, sampling took place at latitude 11°52'4.17" S and longitude 55°36'48.10" W, at an elevation of 356 m above sea level. The climate is tropical with a dry season, according to the Köppen–Geiger classification (Aw), with an average annual temperature of 24 °C and approximately 2,500 mm of annual precipitation. In the municipality of Primavera do Leste, sampling was carried out at latitude 15°21'12.41" S and longitude 54°25'15.17" W, at an elevation of 620 m above sea level. The average annual temperature in the region ranges between 18 °C and 24 °C, and the average yearly rainfall is approximately 1,560 mm.

At the collection site in Sinop, the soil is classified as a dystrophic Red Latosol, while in Primavera do Leste, it is a dystrophic Red-Yellow Latosol. Samples were collected at 0–20 cm depth, then broken up, air-dried, and sieved through a 2 mm mesh. The chemical and physical characteristics were as follows: Primavera do Leste: pH (CaCl2) = 4.1; Ca = 1.4 cmol₍c₎ dm⁻³; Mg = 0.6 cmol₍c₎ dm⁻³; K = 0.16 cmol₍c₎ dm⁻³; Al = 0.9 cmol₍c₎ dm⁻³; P (resin) = 10 mg dm⁻³; M.O. = 6.4 g kg⁻1; physical composition (%): sand = 41, silt = 17, clay = 42. Sinop: pH (CaCl2) = 4.0; Ca = 1.4 cmol₍c₎ dm⁻³; Mg = 0.6 cmol₍c₎ dm⁻³; K = 0.21 cmol₍c₎ dm⁻³; Al = 1.2 cmol₍c₎ dm⁻³; P (resin) = 12 mg dm⁻³; M.O. = 5.4 g kg⁻1; physical composition (%): sand = 44, silt = 19, clay = 37.

One month before the experiments began, 2 t ha⁻1 and 2.8 t ha⁻1 of limestone with 91% PRNT were applied and thoroughly mixed to homogenize the soil, aiming to correct acidity and neutralize toxic aluminum in the soils of Sinop and Primavera do Leste, respectively.

Two experiments were conducted under greenhouse conditions: Trial I for determining the appropriate P dose, and Trial II for deciding the appropriate Co and Mo doses. In both experiments, soil was placed in 2 kg plastic pots. Cowpea seeds were superficially disinfected with 70% ethyl alcohol for 1 minute and 5% sodium hypochlorite for 3 minutes, followed by ten successive washes with sterile deionized water. Sowing was carried out using four seeds per pot (cv. BRS Guariba), which is recommended for cultivation in the Central-West region. Thinning was performed five days after emergence, maintaining two plants per pot. Irrigation was applied daily, keeping moisture close to 80% of field capacity. All treatments were inoculated with the Bradyrhizobium strain BR3262 (Zilli, 2009).

Two trials were conducted to evaluate the effect of different treatments. Trial I was arranged in a randomized block design in a 2 × 5 factorial scheme (2 soils × 5 P2O5 rates) with four replicates. The P2O5 rates, applied in the form of single superphosphate [Ca(H2PO₄)2·CaSO₄], were 0, 100, 200, 300, and 400 mg pot⁻1, corresponding to 0, 100, 200, 300, and 400 kg P2O5 per hectare.

Based on the results of Trial I, which established the optimal phosphorus (P) dose, Trial II was conducted to evaluate the effect of different proportions of cobalt (Co) and molybdenum (Mo). Five Co:Mo ratios (w:w) were tested: 0:0, 2:8, 3:16, 4:32, and 6:64 (mg pot⁻1), corresponding to 0, 2, 3, 4 and 6g Co ha-1 and 0, 8, 16, 32 and 64g Mo ha-1 — in a 2 × 5 factorial scheme (soils × doses) with four replicates. Cobalt chloride (CoCl2) and ammonium molybdate [(NH₄)₆Mo₇O2₄·4H2O] were used as sources, and the application was performed via foliar spray on the twentieth day after plant emergence.

At 35 days after germination (V4 stage), measurements were taken for plant height and stem diameter at the cotyledonary node. Subsequently, the plants were harvested and separated into roots and shoots by cutting approximately 1 cm above the soil surface. The nodules were detached from the roots and counted to determine the number of nodules (NN). To evaluate dry nodule mass (DNM), dry root mass (DRM), and dry shoot mass (DSM), these plant parts were placed in a forced-air circulation oven at 65–70 °C until reaching a constant mass and were then weighed. The shoots were ground to determine total nitrogen (N) content using the semimicro Kjeldahl method [

36]. The total N content was multiplied by the dry shoot mass to obtain the total nitrogen (N-total) accumulated in the aerial part [37].

Statistical analyses were performed using the Sisvar software. Data were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA) and regression analysis to evaluate the effect of the doses. The most appropriate model was selected based on the magnitude of the coefficient of determination (R²), significant at the 5% probability level. Comparisons between the effects of the doses and between soil types were carried out using Tukey’s test, at a 5% significance level.

5. Conclusion

The dose of 200 mg of P2O5 pot⁻1, corresponding to 200 kg ha⁻1 of P2O5, resulted in the greatest nodulation of cowpea plants and higher nitrogen accumulation, consequently increasing plant biomass.

The soil collection site influenced the development and nodulation response of cowpea plants when subjected to different phosphorus (P) doses.

The application of Co + Mo influenced plant development, regardless of whether it affected the BNF process.

Micronutrient levels (Mo at 32 g ha-1 and Co at 4 g ha-1) provided superior nodulation, biomass, and nitrogen accumulation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: F.P. and G.R. X.; Methodology: F.S.P., G.R. X., J.E.Z., J.R. and E.Z.; Software: F.P., S.N. and E.S.J.; Validation: F.S.P., S.N., E.S.J., J.R., J.E.Z. and G.R. X.; Formal analysis: F.P.; Investigation: F.S.P., S.N. and E.S.J.; Resources: G.R.X. and J.E.Z.; Data curation: F.S.P. and J.R.; Writing—original draft preparation: F.P.; Writing—review and editing: F.S.P., S.N., E.S.J., E.Z., A.B.C.L.; J.C.A. and G.R.X.; Visualization: F.S.P., S.N., E.S.J., E.Z., A.B.C.L., J.C.A.; J.R., J.E.Z. and G.R.X.; Supervision: J.E.Z. and G.R.X.; Project administration: F.S.P. and G.R.X.; Funding acquisition: G.R.X. All authors have read and approved the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Brazilian Agriculture Research Corporation (EMBRAPA); Graduate Program in Soil Sciences at the Federal Rural University of Rio de Janeiro; Carlos Chagas Filho Research Foundation of the State of Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ) project E-26/202.997 (G.R.X.). Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data presented in this study are available as supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank laboratory technician João Luiz Bastos for his valuable collaboration in the field experiments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in the present manuscript:

| BNF |

Biological Nitrogen Fixation |

| DSM |

Dry Shoot Mass |

| P |

Phosphorus |

| N |

Nitrogen |

| CoMo |

Cobalt + Molybdenum |

References

- Barbieri, M.; Dossim, M.F.; Nora, D.D.; Santos, W.B. dos; Bevilacqua, C.B.; Andrade, N. de; Boeni, M.; Deuschle, D.; Jacques, R.J.S.; Antoniolli, Z.I. Ensaio sobre a bioatividade do solo sob plantio direto em sucessão e rotação de culturas de inverno e verão. Revista de Ciências Agrárias 2019, 42, 122–134. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, P.A.; Salinas, J.G. Low-Input Technology for Managing Oxisols and Ultisols in Tropical America. In Advances in Agronomy; Brady, N.C., Ed.; 280-406; Academic Press, 1981; pp. 279–406. [CrossRef]

- Malavolta, E. Elementos de Nutrição Mineral de Plantas; Editora Ceres: São Paulo-SP, 1980;

- Elgharably, A. Effects of rock phosphate added with farm yard manure or sugar juice residues on wheat growth and uptake of certain nutrients and heavy metals. Journal of Soils and Sediments, 2020. 20(10), 3931–3940. [CrossRef]

- Sulieman, S.; Kusano, M.; Ha, C.V.; Watanabe, Y.; Abdalla, M.A.; Abdelrahman, M.; Kobayashi, M.; Saito, K.; Mühling, K.H.; Tran, L.-S.P. Ajustes Metabólicos Divergentes Em Nódulos São Indispensáveis Para a Fixação Eficiente de N 2 Da Soja Sob Estresse de Fosfato. Plant Science 2019, 289, 110249. [CrossRef]

- EMBRAPA Sistema brasileiro de classificação de solos; 5th ed.; Empresa Brasileira de Pesquisa Agropecuária, 2018; ISBN 978-85-7035-800-4.

- Sa, T.M.; Israel, D.W. Energy Status and Functioning of Phosphorus-Deficient Soybean Nodules. Plant Physiol 1991, 97, 928–935. [CrossRef]

- Freire Filho, F.R.; Ribeiro, V.Q.; Barreto, P.D.; Santos, A.A. dos Feijão-caupi: avanços tecnológicos. In Melhoramento genético.; In: FREIRE FILHO, F. R.; LIMA, J. A. de A.; RIBEIRO, V. Q. (Ed.). Feijão-caupi: avanços tecnológicos. Brasília, DF: Embrapa Informação Tecnológica; Teresina: Embrapa Meio-Norte, 2005. Cap. 1. p. 28-92.: Teresina: Embrapa Meio-Norte, 2005; pp. 29–92.

- Freire Filho, F.R. Feijão-caupi no Brasil: produção, melhoramento genético, avanços e desafios; Embrapa Meio-Norte, 2011; ISBN 978-85-88388-21-5.

- Taiz, L.; Moller, I.M.; Zeiger, E.; Murphy, A. Fisiologia e desenvolvimento Vegetal; 6th ed.; Artmed: Porto Alegre, 2017;

- Dalmolin, A.K. Aplicação Foliar de Molibdênio e Cobalto na Cultura da Soja: Rendimento e Qualidade de Sementes. Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciência e Tecnologia de Sementes- Dissertação, Universidade Federal de Pelotas: Rio Grande do Sul - Brasil, 2015.

- Ceretta, C.A.; Pavinato, A.; Pavinato, P.S.; Moreira, I.C.L.; Girotto, E.; Trentin, É.E. Micronutrientes na soja: produtividade e análise econômica. Cienc. Rural 2005, 35, 576–581. [CrossRef]

- Coutinho, P.W.R.; Silva, D.M.S.; Saldanha, E.M.C.; Okumura, R.S.; Júnior, M.L.S. Doses de Fósforos Na Cultura Do Feijão-Caupi Na Região Nordeste Do Estado Do Pará. REVISTA AGRO@MBIENTE ON-LINE 2014, 66–73. [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, J. Produção e controle de qualidade de mudas florestais. Memórias do Instituto de Botânica 1995, 451.

- Souto, J.S.; Oliveira, F.T.; Gomes, M.M.S.; Nascimento, J.P. Efeito Da Aplicação de Fósforo No Desenvolvimento de Plantas de Feijão Guandu: Cajanus Cajan L. Millsp. Revista verde de agroecologia e desnvolvimento sustentável 2009, 135–140, ISSN 1981-8203.

- Gualter, R.M.R.; Leite, L.F.C.; Araújo, A.S.F.D.; Alcântara, R.M.C.M.D.; Costa, D.B. INOCULAÇÃO E ADUBAÇÃO MINERAL EM FEIJÃO-CAUPI: EFEITOS NA NODULAÇÃO, CRESCIMENTO E PRODUTIVIDADE. RSA 2008, 9, 469. [CrossRef]

- Zilli, J.E.; VILARINHO, A.A.; ALVES, J.M.A. A Cultura do Feijão-caupi na Amazônia Brasileira.; Boa Vista, RR: Embrapa Roraima., 2009; ISBN 978-85-62701-00-9.

- Collins, M.; Lang, D.J.; Kelling, K.A. Effects of Phosphorus, Potassium, and Sulfur on Alfalfa Nitrogen-Fixation under Field Conditions. Agronomy Journal 1986, 78, 959–963. [CrossRef]

- Lanyon, L. E., & Griffith, A. (1988). Nutrition and fertilizer use. In A. A. Hanson, D. K. Barnes, & R. R. Hill (Eds.), Alfalfa and alfalfa improvement (pp. 333–372). Madison, WI: American Society of Agronomy.

- Araújo, A.P.; Teixeira, M.G. Ontogenetic Variations on Absorption and Utilization of Phosphorus in Common Bean Cultivars under Biological Nitrogen Fixation. Plant and Soil 2000, 225, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, M.I.; Fujita, K. Comparison of Phosphorus Deficiency Effects on the Growth Parameters of Mashbean, Mungbean, and Soybean. Soil Science and Plant Nutrition 1998, 44, 19–30. [CrossRef]

- Raij, B. van. (1991). Fertilidade do solo e adubação (343 p.). Piracicaba, SP: Agronômica Ceres; Associação Brasileira para a Pesquisa da Potassa e do Fosfato.

- Gonçalves, J.L. de M.; Santarelli, E.G.; Moraes Netto, S.P. de; Manara, M.P.; Stape, J.L. Produção de mudas de espécies nativas: substrato, nutrição, sombreamento e fertilização. Nutrição e fertilização florestal 2000, 310–350.

- Novais, R. f.; Smyth, T.J. Fósforo Em Solo e Planta Em Condições Tropicais. Embrapa Cerrados (CPAC) 1999, 399.

- Hanyabui, E.; Apori, S.O.; Frimpong; Atiah, k Phosphorus Sorption in Tropical Soils. Agriculture and food 2020, 599–616. [CrossRef]

- Rheinheimer, D. dos S.; Anghinoni, I.; Conte, E.; Kaminski, J.; Gatiboni, L.C. Dessorção de fósforo avaliada por extrações sucessivas em amostras de solo provenientes dos sistemas plantio direto e convencional. Cienc. Rural 2003, 33, 1053–1059. [CrossRef]

- Rheinheimer, D.S.; Anghinoni, I.; Conte, E. Sorção de fósforo em função do teor inicial e de sistemas de manejo de solos. Rev. Bras. Ciênc. Solo 2003, 27, 41–49. [CrossRef]

- Corrêa, J.C.; Mauad, M.; Rosolem, C.A. Fósforo no solo e desenvolvimento de soja influenciados pela adubação fosfatada e cobertura vegetal. Pesq. agropec. bras. 2004, 39, 1231–1237. [CrossRef]

- Marcondes, J.A.P.; Caires, E.F. Aplicação de molibdênio e cobalto na semente para cultivo da soja. Bragantia 2005, 64, 687–694. [CrossRef]

- Xavier, T.F.; Araújo, A.S.F. de; Santos, V.B. dos; Campos, F.L. Ontogenia da nodulação em duas cultivares de feijão-caupi. Cienc. Rural 2007, 37, 561–564. [CrossRef]

- Toledo, M.Z.; Garcia, R.A.; Pereira, M.R.R.; Boaro, C.S.F.; Lima, G.P.P. Nodulação e atividade da nitrato redutase em função da aplicação de molibdênio em soja. Bioscience Journal 2010, 26, 858–864.

- Campos, B.-H.C. de; Gnatta, V. Inoculantes e fertilizantes foliares na soja em área de populações estabelecidas de Bradyrhizobium sob sistema plantio direto. Rev. Bras. Ciênc. Solo 2006, 30, 69–76. [CrossRef]

- Raij, B.V. Avaliação Da Fertilidade Do Solo. 1981, 142.

- Bárbaro-junior, L.S.; Bárbaro, I.M.; Toller, E.V. Análise de parâmtros de fixação biológica de nitrogênio em cultivares comerciais de soja. ResearchGate 2009. [CrossRef]

- Câmara, G.M. de S. Nitrogênio e produtividade da soja. Soja: tecnologia da produção II 2000, 295–339.

- Empresa Brasileira de Pesquisa Agropecuária – EMBRAPA, Serviço Nacional de Levantamento e Conservação de Solos. (1997). Manual de métodos de análise de solo (212 p.). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Embrapa.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).