1. Introduction

Arteriovenous malformation (AVMs) is a form of vascular malformations which include arterial, venous, arteriovenous, lymphatic and combined malformations [

1,

2,

3] (

Figure 1). These lesions were first described in the brain by Hubert von Luschka and Rudolf Virchow in the 1850s, laying the foundation for our understanding of cerebrovascular pathology [

3,

4,

5,

6]. AVMs are currently identified through Hamburg classification, named and established by a 1988 workshop in Hamburg, Germany, as a clinical guide based on morphological and embryological characteristics [

7,

8,

9]. AVMs are most often congenital in origin, reflecting aberrant vascular development during embryogenesis, although accumulating evidence suggests they may also be dynamic lesions capable of remodeling and progression throughout life under the influence of genetic, inflammatory, and hemodynamic factors [

3,

4,

5]. The clinical consequences of AVMs are determined by size, location, vascular architecture, and flow dynamics. One of the most serious risks is life-threatening hemorrhage, which remains the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in cerebral AVMs (cAVMs) [

10]. Hemorrhage may be intraparenchymal, intraventricular, or subarachnoid, and often results in long-term neurological deficits. Beyond cAVMs, extracranial AVMs can occur in the gastrointestinal tract, pulmonary vasculature, liver, and musculoskeletal system, where they present with organ-specific dysfunction such as bleeding, high-output heart failure, chronic pain, or soft tissue overgrowth [

10,

11,

12,

13]. These diverse manifestations illustrate that AVMs represent a multisystem disease spectrum rather than a purely neurological condition.

The clinical manifestations of AVMs are highly variable. In the brain, they may remain asymptomatic and be discovered incidentally, or they can present with seizures, progressive neurological decline, or acute hemorrhage [

14]. Following an initial rupture, the risk of subsequent hemorrhage is considerably higher, underscoring the importance of individualized risk assessment [

10,

15,

16]. Cerebral AVMs are frequently diagnosed in young adults, although pediatric cases often present earlier and may demonstrate more aggressive behavior, particularly when associated with genetic syndromes such as hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT) [

4,

12,

14,

17,

18,

19,

20]. In these settings, multiple AVMs may occur across different organ systems, necessitating long-term surveillance and multidisciplinary care [

21,

22,

23].

Recent research has highlighted the molecular underpinnings of AVMs, including germline mutations in ENG (endoglin), ACVRL1(activin receptor-like kinase 1), and SMAD4 (Mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 4) in HHT, as well as somatic mutations in KRAS (Kirsten rat sarcoma virus) , MAP2K1 (Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1), and PIK3CA (phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha) in sporadic lesions [

4,

18,

19,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]. These discoveries have shifted the paradigm from viewing AVMs as static congenital anomalies to considering them as dynamic, genetically influenced vascular malformations amenable to targeted therapies [

31,

32,

33,

34]. At the same time, translational advances in imaging, including high-resolution digital subtraction angiography, susceptibility-weighted MRI, arterial spin labeling perfusion imaging, and 4D flow MRI—have greatly enhanced the ability to characterize AVM hemodynamics, identify rupture-prone lesions, and plan interventions [

1,

2,

20,

26,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40].

Given their clinical heterogeneity and potential severity, AVMs demand a coordinated, multidisciplinary approach involving neurologists, interventionalists, neurosurgeons, and geneticists [

13,

21,

36]. Parallel progress in preclinical research has provided invaluable insights: animal models in mice and zebrafish have elucidated the contributions of VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factors), Notch, and TGF-β (transforming growth factor–β) signaling, as well as endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition, to AVM initiation and progression [

24,

41,

42]. These models continue to inform therapeutic discovery, particularly for targeted pharmacologic approaches aimed at normalizing vascular structure and function.

Thus, AVMs represent not only a clinical challenge but also a unique biological model at the intersection of vascular biology, genetics, and hemodynamics [

43,

44]. Their rarity, affecting roughly 1 in 1,000 individuals, belies their significant clinical impact, particularly in young patients, and underscores the need for improved strategies in diagnosis, and long-term management [

11,

45]. As research advances, the integration of laboratory discoveries, imaging innovations, and clinical expertise holds promise for more precise and effective care, paving the way toward personalized medicine for AVM patients [

3,

12,

21,

31,

46].

2. Epidemiology and Clinical Presentation

AVMs are relatively uncommon vascular anomalies, with cAVMs being the most extensively studied subtype because of their potential for severe neurological morbidity [

29]. There is no definitive sex predominance, though a slight male bias has been observed in some regional studies [

47,

48]. In pediatric patients, earlier onset and more aggressive behavior are not uncommon, particularly in association with genetic syndromes [

47,

48].

A subset of AVMs occurs in the context of hereditary conditions, most notably HHT, an autosomal dominant disorder caused by mutations in ENG, ACVRL1, or SMAD4 [

11,

19,

25,

49,

50,

51]. These patients frequently harbor multiple AVMs in the lungs, liver, and brain, requiring multidisciplinary surveillance and long-term management. Another well-described syndrome is capillary malformation–arteriovenous malformation (CM-AVM), caused by mutations in RASA1 and EPHB4, characterized by multifocal fast-flow lesions and cutaneous vascular malformations [

27,

49,

51]. Clinical presentation varies by anatomic location, nidus size, and flow characteristics. For cAVMs, intracranial hemorrhage is the most common presentation, occurring in ~50% of cases [

26,

52,

53]. Hemorrhages are typically intraparenchymal but may extend into subarachnoid or intraventricular compartments with seizures occur in 20–40% of patients, particularly with cortical involvement [

10,

26]. Other presentations include chronic headaches, focal neurological deficits, or progressive decline related to venous hypertension and vascular steal in eloquent brain regions [

10,

36].

The annual risk of bleeding for unruptured cAVMs is ~2–4% but rises to 6–15% following a first hemorrhage [

1,

47,

54]. These data emphasize the need for individualized risk assessment, particularly in asymptomatic patients under surveillance [

46,

47,

50]. Spinal AVMs, while less common, produce distinct clinical features such as progressive myelopathy, radicular pain, or acute neurological decline due to ischemia or venous hypertension [

35].

Extracranial AVMs display a wide spectrum of presentations [

4,

11,

25,

50,

55]. Pulmonary AVMs, often seen in HHT, may cause hypoxemia, paradoxical embolism, or stroke [

11,

50,

56,

57]. Gastrointestinal AVMs can present occult bleeding or chronic anemia, while hepatic AVMs may lead to high-output cardiac failure or portal hypertension [

57]. Musculoskeletal and soft tissue AVMs often produce localized pain, swelling, limb overgrowth, or impaired function [

12,

13,

35]. In some cases, extensive arteriovenous shunting can cause systemic complications, such as increased cardiac preload or ischemia of adjacent tissues [

1,

57,

58,

59].

Given this heterogeneity, timely diagnosis and appropriate management require multidisciplinary expertise. Syndromic AVMs necessitate multisystem surveillance, while isolated AVMs benefit from targeted imaging, regular monitoring, and, when appropriate, intervention. Future integration of genetic insights with detailed clinical phenotyping may further enhance diagnostic precision and guide individualized treatment strategies.

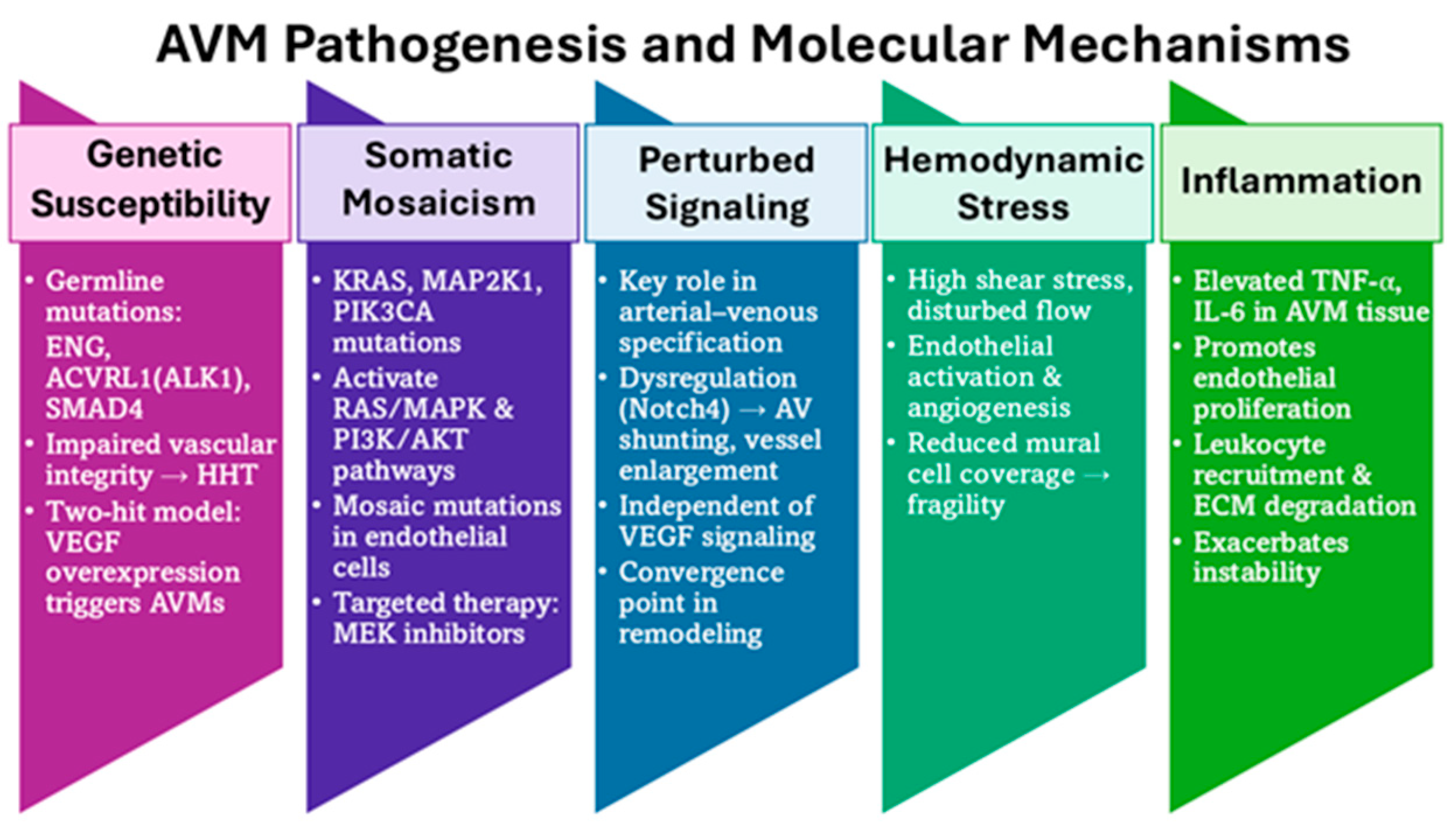

3. Pathogenesis and Molecular Mechanism

AVMs result from complex disturbances in vascular development and remodeling, influenced by both genetic and acquired factors [

5]. Although typically congenital, AVMs are increasingly recognized as dynamic lesions modulated by molecular and hemodynamic cues throughout life [

10,

43,

52,

60,

61,

62]. At the cellular level, aberrant arteriovenous connections arise from disruptions in endothelial specification, vessel patterning, and mural cell recruitment [

56,

58,

62,

63,

64]. A central mechanism is the failure of vascular stabilization and remodeling, rather than complete developmental arrest, suggesting that AVMs may progress postnatally under permissive conditions such as inflammation, injury, or hormonal stimulation [

28,

58,

62,

63].

A major pathway implicated in AVM biology is the TGF-β superfamily, particularly ENG and ACVRL1[

63]. Both are required for endothelial quiescence and vascular integrity [

18,

38,

63,

65,

66,

67]. Mutations in these genes, as observed in HHT, impair angiogenic regulation and drive abnormal proliferation and vessel dilation [

11,

25,

50,

56]. Genetic defects alone, however, are insufficient to produce AVMs. In animal models, localized angiogenic stimuli such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) overexpression are required to trigger malformation, supporting a “two-hit” model of disease [

19,

53,

56,

64].

In sporadic AVMs, somatic mutations have been identified in signaling genes including KRAS, MAP2K1, and PIK3CA [

20,

25,

68]. These mutations activate RAS/MAPK and PI3K/AKT signaling, leading to unchecked endothelial proliferation and aberrant angiogenesis [

25]. Importantly, KRAS mutations have been found in endothelial cells of human brain AVMs, providing the first direct evidence that sporadic lesions may result from postzygotic mosaic mutations [

20,

25,

68]. This paradigm mirrors other vascular malformations and overgrowth syndromes [

5,

54,

60]. Such discoveries highlight new therapeutic opportunities, with MEK inhibitors showing promise in preclinical RAS-mutated AVM models [

20,

64].

Notch signaling also plays a crucial role in arterial–venous specification and branching morphogenesis [

64,

69,

70,

71,

72,

73]. Dysregulation of Notch, particularly Notch4, induces arteriovenous shunting and vessel enlargement in murine models [

18,

20,

28,

74,

75,

76,

77]. Endothelial-specific overexpression of activated Notch4 generates malformations resembling human AVMs, independent of VEGF signaling [

18,

28,

42,

64,

74,

78,

79]. These findings suggest Notch serves as a convergence point for developmental and pathological vascular remodeling [

80]. Furthermore, reduced mural cell coverage and extracellular matrix components in AVM nidus tissue contribute to vascular fragility and hemorrhagic risk [

20,

81].

Beyond genetics, biomechanical forces and inflammation influence AVM initiation and progression [

21,

82]. High shear stress and disturbed flow activate endothelial transcriptional programs that promote angiogenesis and remodeling, particularly when TGF-β or Notch signaling is impaired [

53,

83,

84,

85]. Inflammatory mediators such as TNF-α and IL-6 are elevated in AVM tissue and further amplify endothelial proliferation, leukocyte recruitment, and extracellular matrix degradation, exacerbating lesion instability [

53,

82,

84,

86].

Taken together, AVM pathogenesis reflects a multifactorial process involving germline and somatic mutations, dysregulated angiogenic signaling, aberrant mechanotransduction, and inflammatory responses (

Figure 2) [

2,

21,

78,

79,

87]. Advances in molecular profiling have refined understanding of these mechanisms and uncovered new targets for pharmacologic intervention [

2,

21,

50]. As precision medicine evolves, integration of genetic diagnostics and pathway-specific therapies offers the potential for individualized management, especially in surgically inaccessible or refractory lesions.

4. Diagnosis and Treatment

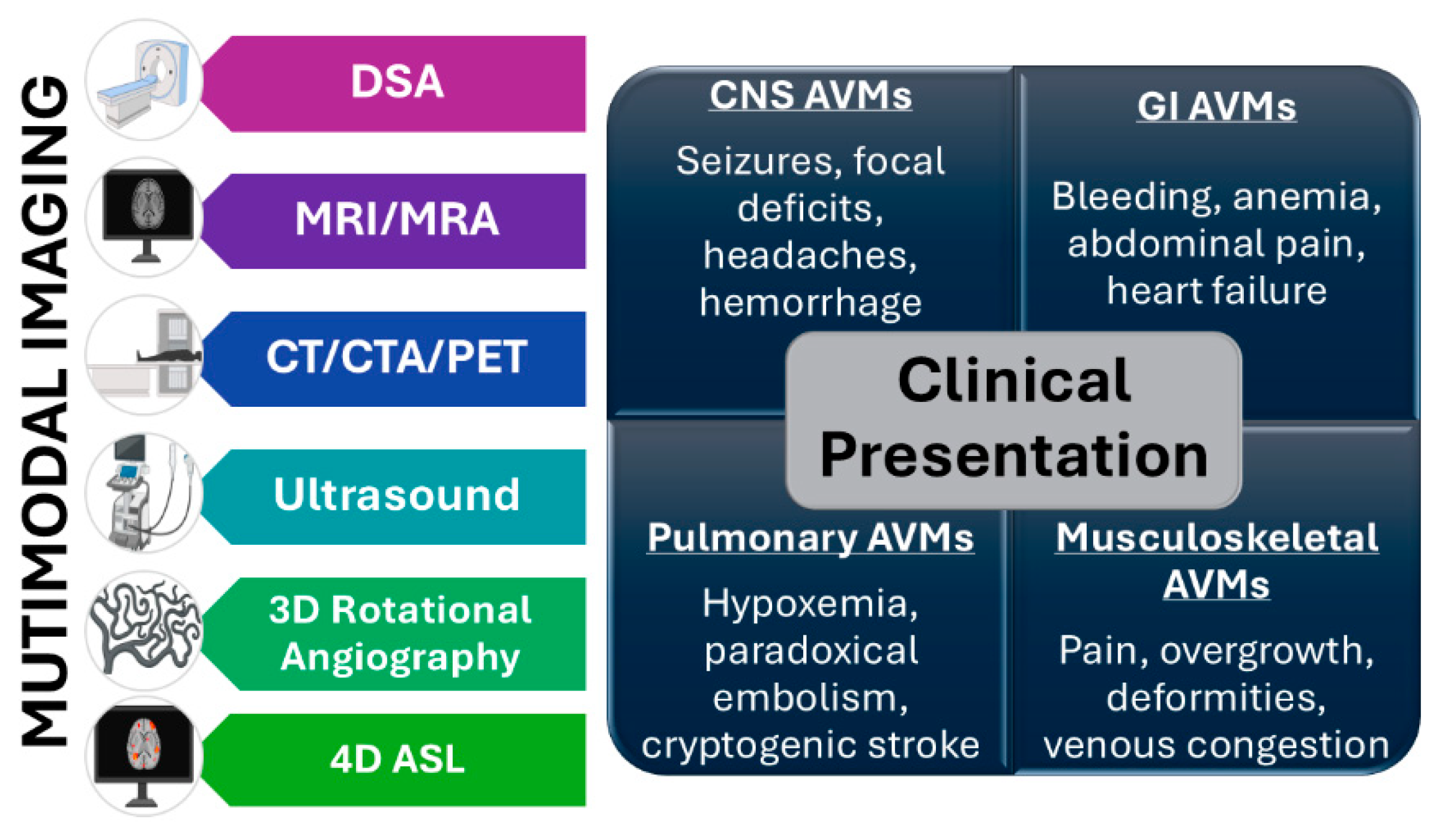

The clinical presentation of AVMs at the time of diagnosis is strongly determined by anatomical location, size, and vascular dynamics, resulting in significant heterogeneity across organ systems. Within the central nervous system (CNS), patients may present with seizures, focal neurological deficits, chronic headaches, or intracranial hemorrhage, depending on the lesion’s proximity to eloquent brain regions [

2,

3,

5,

36,

88,

89]. AVMs located in the gastrointestinal tract frequently manifest chronic gastrointestinal bleeding, anemia, abdominal pain, or, in severe cases, high-output cardiac failure due to large-volume arteriovenous shunting [

21,

40,

54,

90]. Musculoskeletal AVMs may cause localized pain, tissue overgrowth, venous congestion, deformities, or limb hypertrophy, often progressing to functional impairment if untreated [

2,

3,

5,

14,

53]. Pulmonary AVMs, commonly associated with HHT, can lead to hypoxemia, paradoxical embolization, and cryptogenic stroke [

19,

25,

56]. Conversely, minorities of the AVMs are diagnosed incidentally and remain asymptomatic. Recognizing these diverse presentations is crucial for timely and accurate diagnosis.

In addition to overt clinical symptoms, subclinical or small AVMs may remain asymptomatic for years, only being discovered incidentally during imaging for unrelated conditions [

13]. These incidental findings present diagnostic dilemmas, as their natural history and rupture risk can vary substantially [

91]. Syndromic associations, such as HHT or capillary malformation–AVM syndrome (linked to RASA1 and EPHB4 mutations), further complicate diagnosis, as multiple lesions in different organs may coexist [

27,

29,

54,

92]. A high index of suspicion is therefore required in patients with recurrent epistaxis, mucocutaneous telangiectasias, or family history of AVM-related disorders.

Accurate diagnosis relies on a multimodal imaging approach, with each modality offering unique insights into lesion architecture and hemodynamics. Digital subtraction angiography (DSA) remains the gold standard for AVM characterization, providing dynamic, high-resolution visualization of arterial feeders, the nidus, and venous drainage patterns [

36,

54,

60,

93,

94]. However, given its invasive nature, DSA is typically reserved for definitive evaluation and treatment planning.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has become the most widely used noninvasive modality, particularly for CNS AVMs [

31]. T1- and T2-weighted sequences demonstrate flow voids, while susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI) detects small hemorrhages or microbleeds [

34]. Perfusion-weighted MRI and MR angiography provide hemodynamic information, such as shunting and regional perfusion deficits [

34]. High field 7T MRI is under investigation for its ability to detect micro-AVMs and refine assessment of cortical involvement [

34].

Computed tomography (CT) and CT angiography (CTA) are invaluable for rapid assessment in the acute setting, particularly when hemorrhage is suspected [

2,

60,

93]. CTA allows reconstruction of vascular networks and can delineate nidus size and draining veins in patients who are unstable for MRI or angiography [

60].

Ultrasonography, particularly colored Doppler and duplex ultrasound, offers a real-time, inexpensive, and radiation-free modality for superficial AVMs [

31]. It is often used in pediatric or peripheral lesions. Three-dimensional rotational angiography (3D-RA) represents a major advancement, providing unparalleled spatial resolution for surgical or endovascular planning [

31,

43,

95].

Emerging modalities include positron emission tomography (PET), which may detect metabolic activity within the nidus, and molecular imaging strategies targeting angiogenesis-related markers [

2,

60,

93]. Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning are also being investigated for automated AVM segmentation, rupture-risk prediction, and treatment planning, offering potential to reduce interobserver variability [

60,

93,

94,

96].

Small, asymptomatic, or deeply located AVMs are often missed with conventional imaging. These lesions may present only with subtle symptoms or be masked by coexisting vascular abnormalities [

60,

89,

93]. Contrast-enhanced imaging or serial studies are sometimes required to capture dynamic changes in vascular flow [

54,

60,

93,

94]. In syndromic patients with multisystem disease, whole-body imaging or targeted screening may be required to identify extracranial lesions [

54,

60,

88,

93,

94].

Advancements in genomics and biomarker discovery are expected to augment imaging-based diagnostics. Identifying circulating biomarkers (e.g., endothelial dysfunction proteins, angiogenic factors, or cell-free DNA carrying KRAS/PIK3CA mutations) could help detect subclinical AVMs and stratify rupture risk [

27,

68,

85,

97]. Integration of genomics with imaging will enable precision diagnostics—linking AVM morphology to underlying molecular drivers.

In summary, AVM diagnosis requires a tailored, patient-specific approach that integrates multimodal imaging with careful clinical evaluation (

Figure 3). While DSA remains the gold standard, complementary use of MRI, CTA, ultrasound, and advanced imaging enhances diagnostic accuracy. Despite these advances, detecting small or asymptomatic AVMs continues to pose challenges. Future strategies combining imaging, genomics, and computational modeling promise for earlier detection, individualized risk assessment, and improved treatment planning.

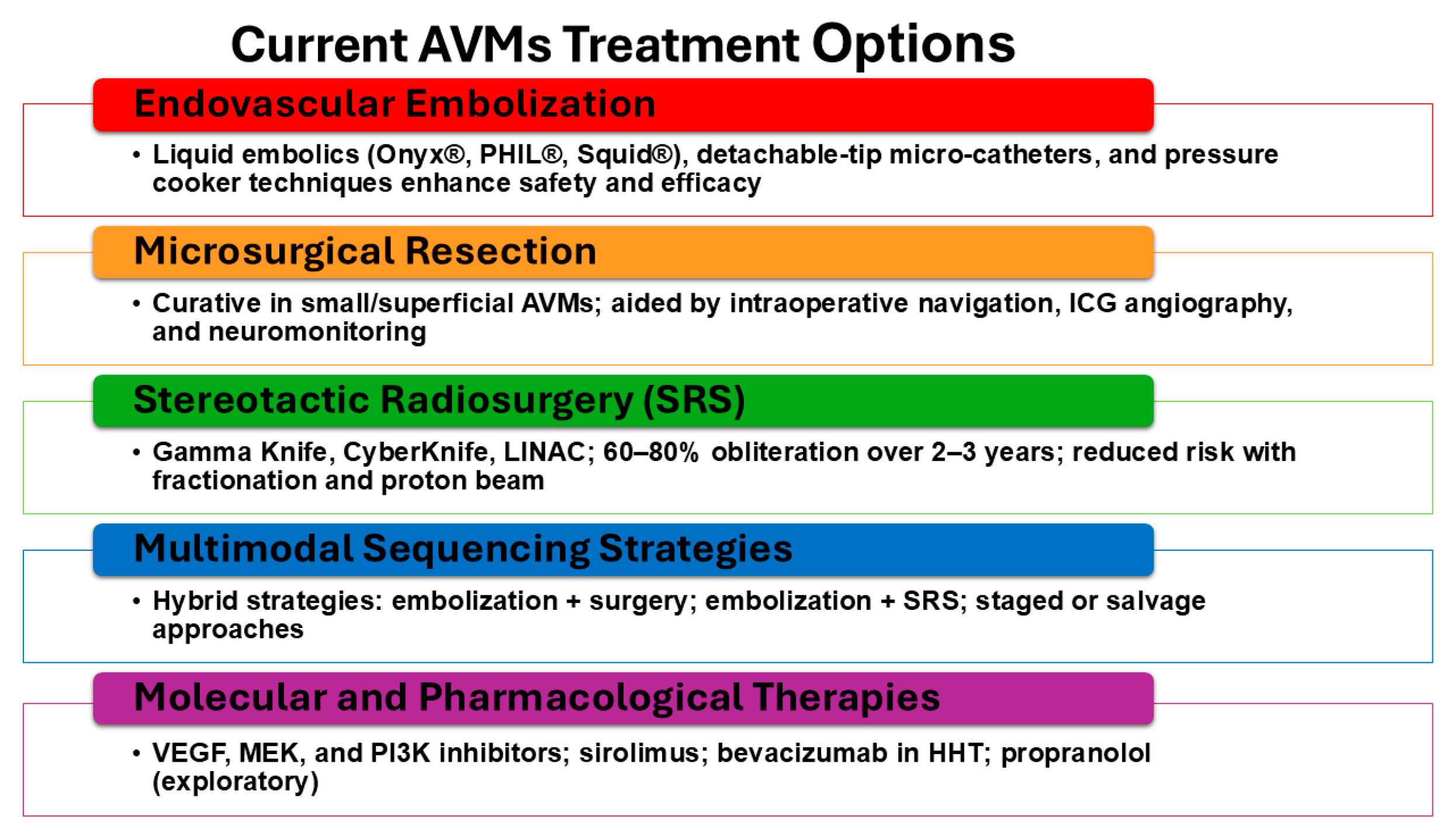

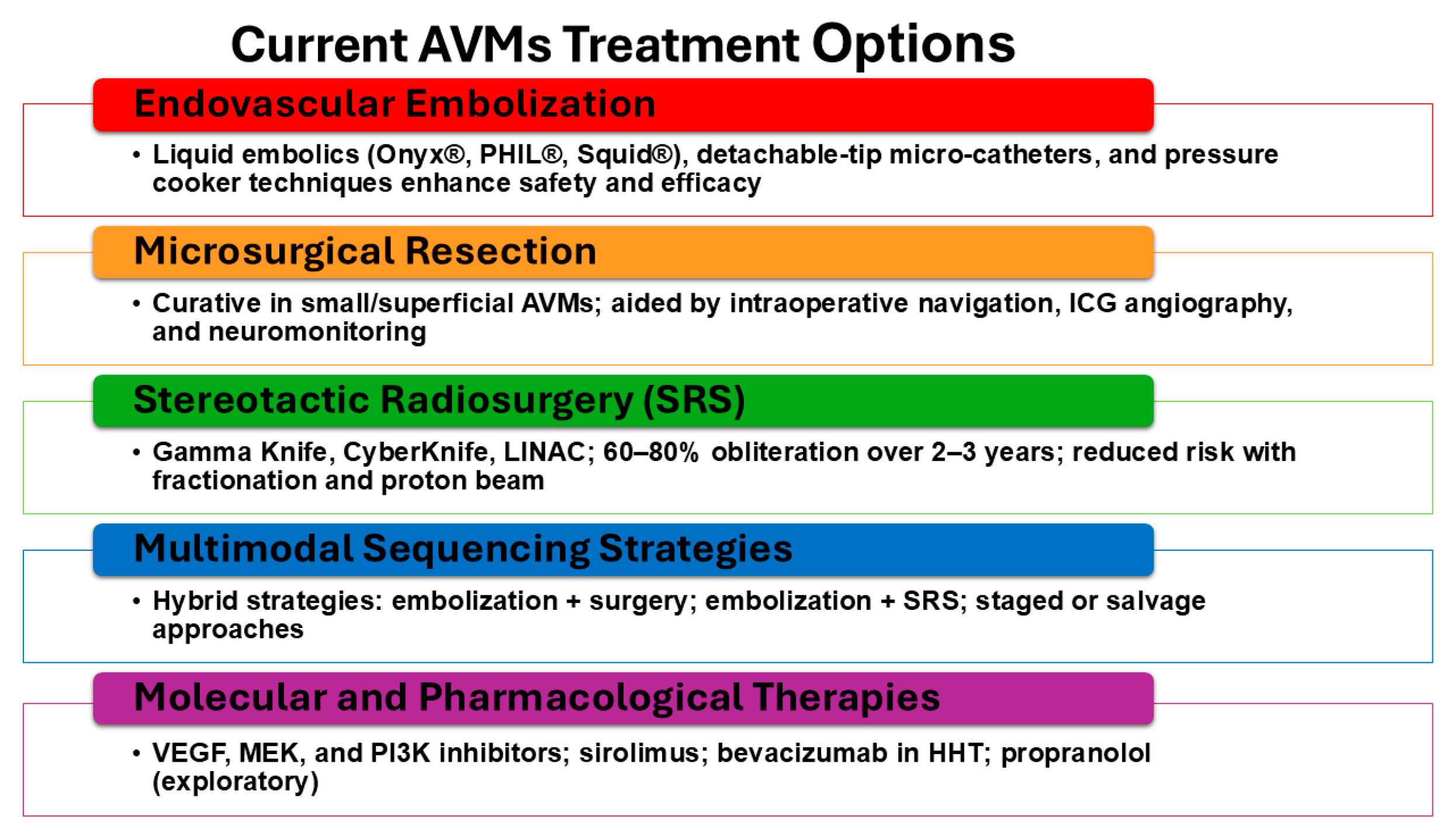

5. Current Treatment Options

5.1. Embolization, Surgery, and Radiation Therapy

The therapeutic management of AVMs is complex, requiring careful assessment of patient-specific and lesion-specific factors to determine the safest and most effective intervention [

21]. Historically, treatment relied on surgical excision or supportive care, but modern advances in endovascular techniques, microsurgical technologies, and stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) have transformed outcomes [

12,

47]. No single modality universally applies to all AVMs; instead, management strategies are tailored according to nidus size, venous drainage, eloquence of involved tissue, and hemorrhagic presentation [

3,

5,

14,

36,

89].

5.2. Endovascular Embolization

Embolization has evolved into a pivotal therapeutic and adjunctive modality. Early embolization employed particulate agents or alcohol, which were associated with high recurrence and complication rates. The introduction of n-butyl cyanoacrylate (NBCA) marked the first major improvement, enabling deeper penetration of the nidus [

5]. In the past two decades, newer liquid embolic such as Onyx® (ethylene-vinyl alcohol copolymer), PHIL® (precipitating hydrophobic injectable liquid), and Squid® have significantly improved treatment durability by permitting controlled injections and deeper nidus occlusion [

3,

98].

Technical refinements, including detachable-tip microcatheters, dual-lumen balloon catheters, and the “pressure cooker technique,” have improved precision and minimized reflux-related complications [

60,

98]. Cone-beam CT and 3D rotational angiography now permit real-time navigation, enabling targeted embolization of deep feeders that were previously inaccessible [

31].

While curative embolization is feasible for some small AVMs, it is most often used adjunctively to reduce nidus size, decrease flow, and prepare patients for subsequent microsurgery or radiosurgery [

98]. Reported obliteration rates with embolization remain variable, ranging from 10% to 50% depending on AVM architecture and embolic agent used [

98]. Complications include inadvertent venous occlusion, ischemia, and hemorrhage, underscoring the need for experienced multidisciplinary teams.

5.3. Microsurgical Resection

Surgical excision remains the only definitive curative therapy for appropriately selected patients [

17,

98,

99]. The Spetzler-Martin grading system has long guided selection, balancing surgical risk against potential benefit. Advances in microsurgical techniques, including intraoperative neuronavigation, indocyanine green (ICG) angiography, and continuous neuromonitoring, have enhanced safety and completeness of resection [

17,

99].

For small, superficial AVMs located in non-eloquent regions, microsurgical resection achieves obliteration rates exceeding 95% with low morbidity [

99]. However, for deep-seated or high-grade AVMs, surgical risks increase significantly, with permanent neurological deficit rates reported at 10–20% in some series [

99]. To mitigate this, hybrid approaches incorporating preoperative embolization to reduce intraoperative bleeding are now standard practice in many centers [

98,

99].

5.4. Stereotactic Radiosurgery (SRS)

SRS has become a cornerstone for the management of small- to medium-sized AVMs (< 3 cm) or those located in eloquent or surgically inaccessible areas. Platforms such as Gamma Knife, CyberKnife, and LINAC-based systems deliver precise, high-dose radiation to the nidus, inducing gradual endothelial proliferation, luminal occlusion, and obliteration over 2–3 years [

17]. Obliteration rates range from 60–80% at 3 years, with hemorrhage risk decreasing during the latency period [

5,

20,

96].

Complications include radiation necrosis, edema, and delayed cyst formation, but improved dose planning, fractionated SRS, and proton beam therapy are reducing such risks [

3]. Combining embolization and radiosurgery, particularly staged embolization followed by SRS, has shown promise in improving obliteration rates for larger or complex AVMs [

2,

14,

98].

5.5. Multimodality and Sequencing Strategies

No single modality is universally curative; therefore, integrated multimodal strategies are increasingly emphasized [

22,

34,

60]. Embolization followed by microsurgery reduces intraoperative bleeding and operative time [

40]. Radiosurgery following partial embolization is used for residual nidus reduction, while surgery following failed SRS provides salvage therapy. Emerging “hybrid operating rooms,” which combine angiographic and neurosurgical capabilities, enable intraoperative angiography and immediate resection following embolization, reducing recurrence risk [

22].

5.6. Emerging Minimally Invasive and Endovascular Interventions

New endovascular technologies are shifting the treatment landscape. Flow-diverting stents and covered stents are under investigation for redirecting arterial inflow, though risks of hemorrhage remain a concern [

21]. Bioactive coils and liquid embolic with radiopaque markers are improving visualization and precision [

60]. Advanced intraoperative imaging, including flat-panel CT and fusion angiography, enhances nidus targeting [

60].

5.7. Novel Molecular and Pharmacologic Therapies

Conventional mechanical approaches are now being supplemented by pharmacologic interventions targeting dysregulated signaling pathways. VEGF inhibitors, MEK inhibitors (for KRAS/MAP2K1 mutant AVMs), PI3K inhibitors (for PIK3CA mutant lesions), and sirolimus (mTOR inhibition) are under active investigation [

29,

59,

97,

100]. Case series in HHT have reported reduced epistaxis and AVM stabilization with bevacizumab, suggesting systemic therapy could serve as an adjunct to conventional modalities [

3]. Propranolol, widely used for infantile hemangiomas, has also been explored for AVMs with anecdotal benefit [

2,

53] (

Figure 4).

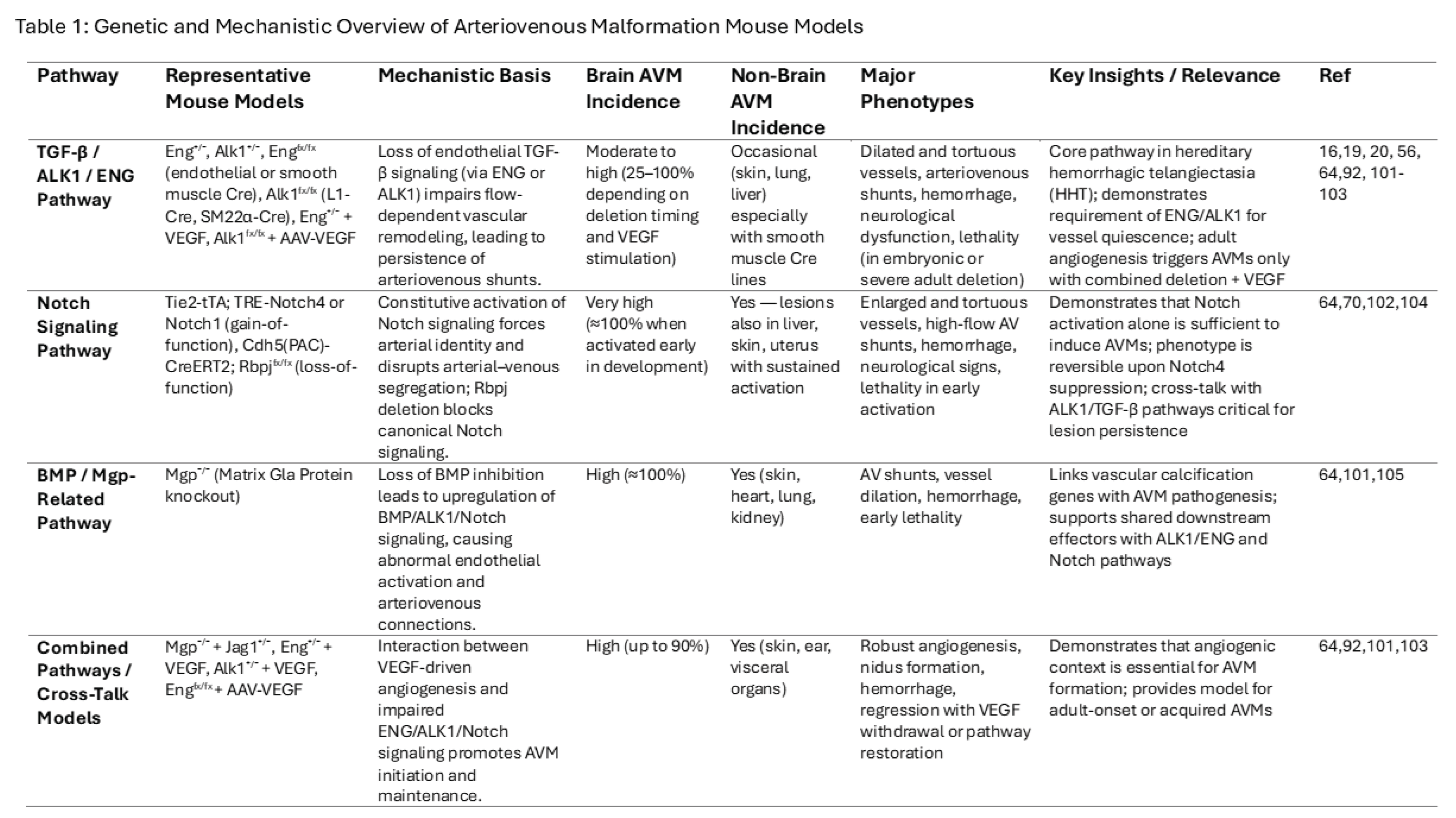

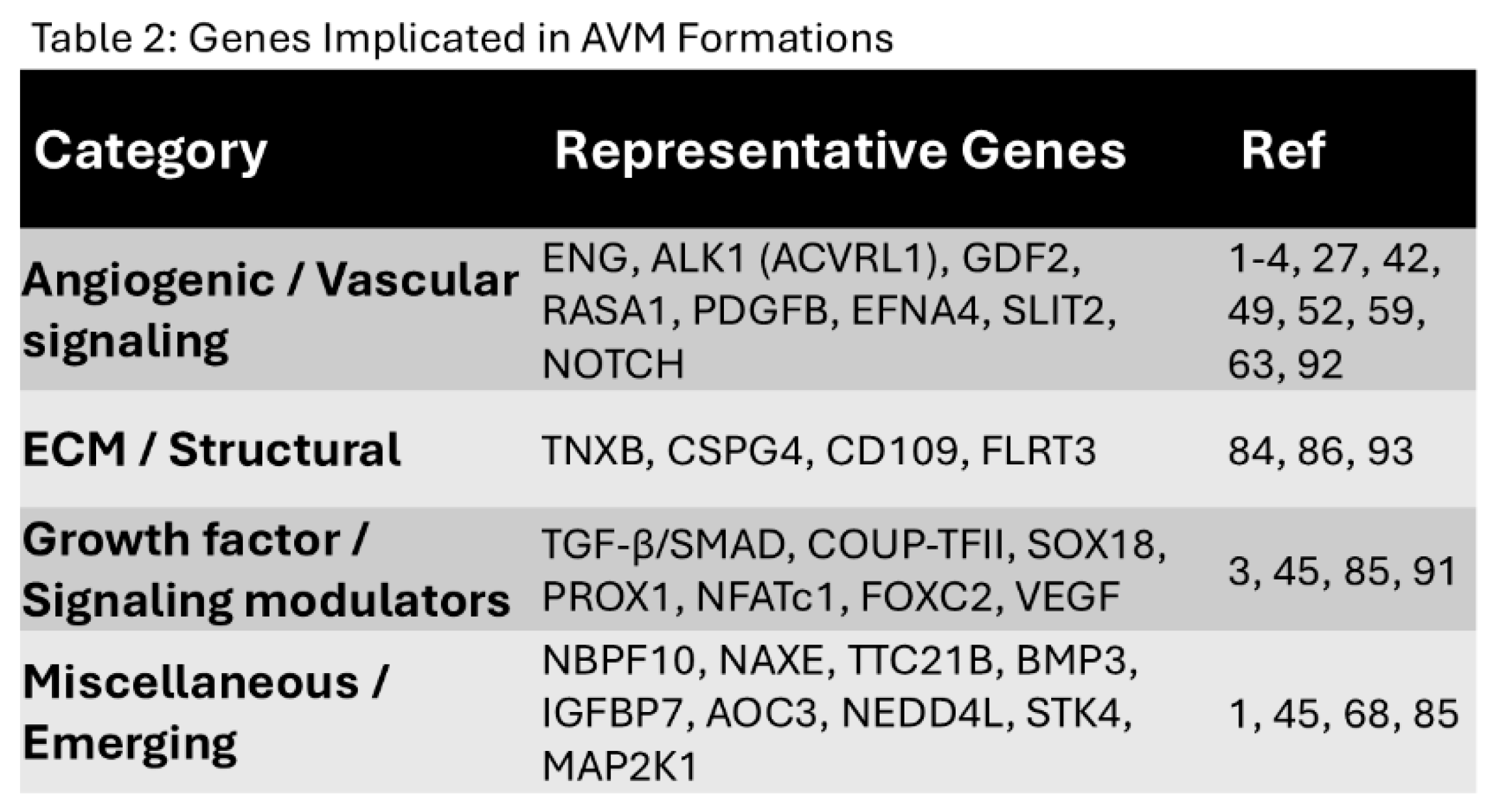

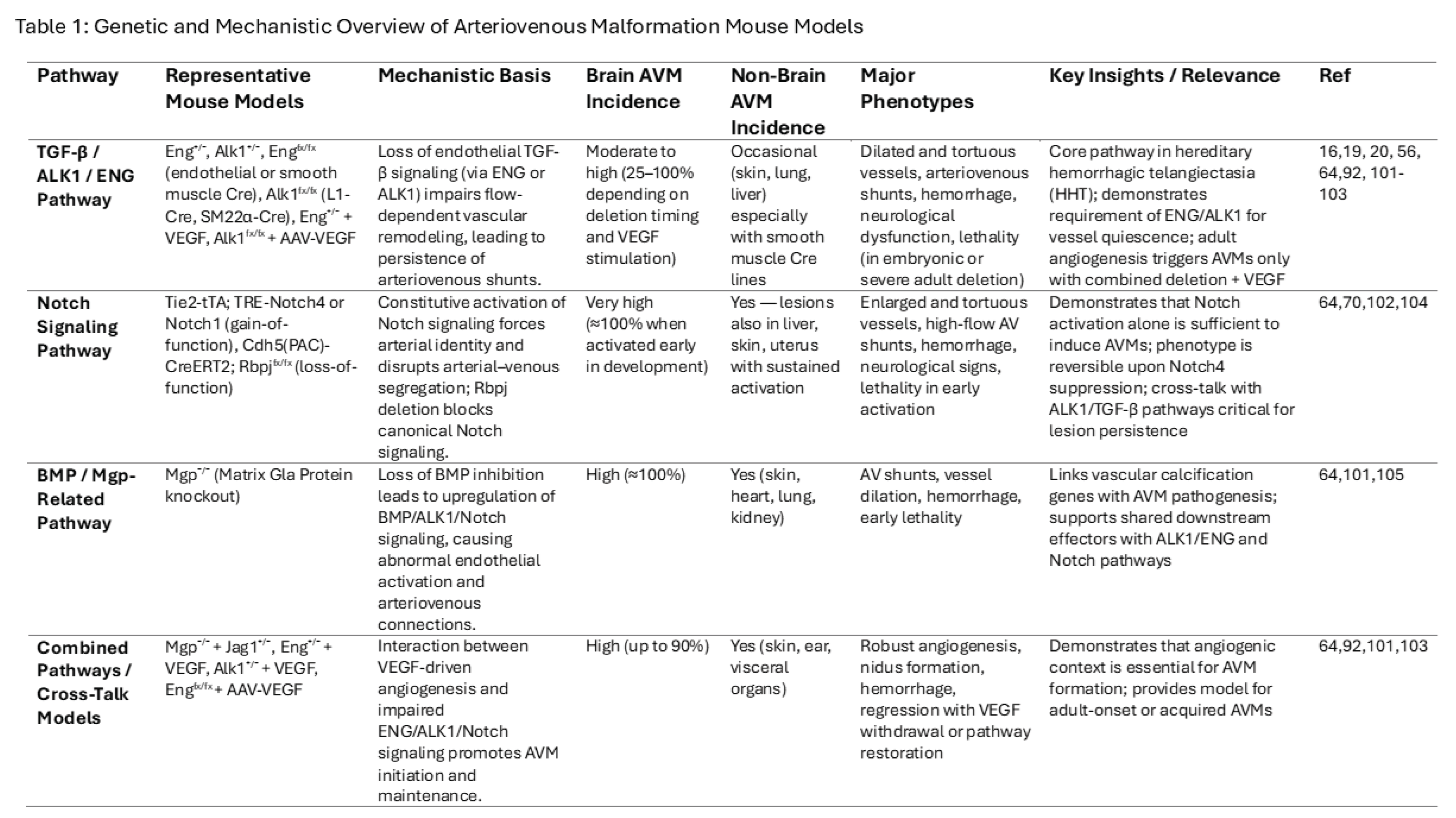

5.8. Animal Models and Translational Insights

Animal models remain indispensable for understanding AVM biology and testing novel interventions (Table 1). Genes potentially associated with AVM formation are listed in Table 2. Genetically engineered mice with ENG, ALK1, or RASA1 mutations recapitulate HHT-associated AVMs and have revealed key roles for TGF-β, Notch, and VEGF pathways [

3,

19,

24,

54,

56,

64,

91,

101,

102,

103,

104,

105]. Zebrafish models allow high-throughput screening of angiogenesis inhibitors, while optogenetic vascular models permit dynamic modulation of flow and vessel remodeling [

41]. Preclinical successes are guiding translational trials of MEK inhibitors and anti-angiogenic therapies [

106].

The future of AVM management lies in integrating genomics, imaging, and novel therapies into precision medicine frameworks. AI-driven rupture-risk prediction, imaging-based treatment planning, and molecular-targeted therapy are expected to complement surgical, endovascular, and radiosurgical modalities. Bioengineering approaches, including vascular tissue scaffolds and regenerative strategies, may one day enable reconstruction of normal vasculature following AVM obliteration.

5.9. Challenges in Developing Effective Treatments for AVMs and Future Directions

Despite significant advances in AVM therapies, several critical challenges persist. The heterogeneity of AVMs with differences in size, location, venous drainage, and clinical symptoms necessitates individualized, case-specific strategies [

3,

54,

96,

98]. Even after technically successful interventions, recurrence or incomplete nidus obliteration is not uncommon, highlighting the need for lifelong surveillance with advanced imaging modalities such as high-field MRI and catheter angiography [

60,

94]. Another unresolved issue is the optimal sequencing of treatment modalities, particularly when combining embolization, microsurgery, and radiosurgery [

2,

3,

21,

31,

90,

99]. Refinements in targeted molecular therapies, the development of novel embolic agents, and the integration of advanced imaging-guided planning represent promising avenues for reducing recurrence rates and improving long-term safety [

31,

60,

98]. At the same time, ongoing research into the genetic and molecular underpinnings of AVMs continues to uncover new therapeutic targets [

3].

The comprehensive management of AVMs demands a multidisciplinary team approach, involving neurosurgeons, interventional neuroradiologists, neurologists, and radiation oncologists. Vascular surgeons often play a role in extracranial AVMs, while anesthesiologists with neurovascular expertise contribute to intraoperative safety. Imaging specialists are crucial for assessing nidus morphology and hemodynamics, which in turn informs treatment planning [

22,

107]. This collaborative framework ensures holistic, patient-centered care that considers not only procedural safety but also comorbidities and quality of life [

23,

36,

60].

Long-term follow-up remains essential for evaluating treatment efficacy and patient outcomes. While successful intervention may result in AVM obliteration, residual risks such as delayed hemorrhage, treatment-related neurological deficits, and AVM recurrence persist [

2,

3,

31,

53,

54,

88]. Pediatric and young adult patients are particularly vulnerable, as recurrence has been documented even after apparent cure [

20,

61]. Structured longitudinal assessments provide insights into the durability of treatment outcomes and inform best practices for surveillance. Including patients that are asymptomatic that were diagnosed incidentally. Consequently, the decision to treat these patients is also complex because this depends on the anatomical and physiological features of the AVM would involves a multidisciplinary approach.

Patient education and engagement are equally critical. Patients and families should receive clear information regarding natural history, treatment risks, and the necessity of routine follow-up. Scheduled imaging (e.g., MRI/MRA, angiography) is central to detecting recurrence or residual lesions [

3,

36,

54]. Empowering patients through education fosters proactive care-seeking behaviors, facilitates adherence to monitoring protocols, and enhances long-term quality of life.

While substantial progress has been made in elucidating AVM biology, unanswered questions remain. The genetic and environmental factors that predispose individuals to AVM development are incompletely understood [

46]. Although somatic mutations in genes such as KRAS, MAP2K1, and PIK3CA have been implicated in sporadic AVMs, the precise triggers initiating lesion progression remain elusive [

1,

15,

20,

63,

68,

108]. Future research must unravel the interplay of angiogenic signaling, hemodynamic stress, and inflammation in nidus formation and rupture.

Looking forward, the integration of advanced imaging and genomics is expected to refine diagnosis and treatment selection. High-resolution modalities such as 7T MRI and 4D flow angiography can improve characterization of AVM morphology and hemodynamics [

15,

20,

68]. Concurrently, genomic profiling holds promise for identifying biomarkers predictive of rupture risk or treatment response [

1,

15]. Together, these advances will enable more precise risk stratification and personalized treatment paradigms.

The emergence of precision medicine approaches is reshaping AVM care. Tailoring therapy to individual AVM characteristics such as size, location, genetic profile could improve outcomes while minimizing morbidity [

1,

15]. Pharmacologic interventions targeting VEGF, Notch, or PI3K/AKT signaling are under active investigation [

108]. Integrating such strategies with surgical and endovascular care may optimize long-term disease control.

Finally, ethical considerations are central to advancing AVM research and care. Ensuring informed consent, transparency about risks, and equitable access to novel therapies remain essential. As new technologies emerge, including molecular therapies and AI-based rupture-risk prediction, ongoing ethical oversight will be critical to balance innovation with patient safety.

In summary, AVMs represent a multifaceted clinical challenge. Continued exploration of their genetic basis, coupled with innovations in imaging, targeted therapies, and multidisciplinary management, offers hope for improved outcomes. By advancing both biological understanding and therapeutic technologies, the field is moving toward more effective, durable, and personalized solutions for patients with these complex vascular anomalies.

6. Conclusions

AVMs arise from a multifaceted interplay of genetic, molecular, and hemodynamic factors that govern their initiation, progression, and clinical complications. Advances in imaging technologies and molecular diagnostics have greatly enhanced the ability to detect and characterize AVMs, thereby improving risk stratification and guiding individualized treatment planning. Despite progress with conventional therapies such as endovascular embolization, microsurgical resection, and stereotactic radiosurgery, significant challenges remain, including recurrence, incomplete obliteration, and treatment-related morbidity. The involvement of dysregulated signaling pathways, notably Notch, VEGF, and TGF-β, underscores the need for targeted molecular therapies that can directly address abnormal angiogenesis and vascular remodeling. In parallel, computational modeling and experimental research continue to shed light on AVM hemodynamics, opening new avenues for therapeutic innovation.

Future research must prioritize the refinement of robust preclinical models that faithfully replicate the heterogeneity of human AVMs. Genetically engineered mouse models, zebrafish platforms, and other vivo systems have already yielded critical insights, yet further optimization is required to enhance translational relevance. These models will remain indispensable for dissecting pathway-specific mechanisms and for testing novel pharmacologic approaches, such as inhibitors of aberrant Notch or VEGF signaling, which may ultimately provide less invasive and more durable treatment options.

Equally important is the integration of genomics, biomarker discovery, and personalized medicine into both research and clinical practice. Advances in bioengineering and regenerative medicine hold promises for vascular remodeling strategies that could complement or replace conventional interventions. A truly multidisciplinary framework is uniting neurosurgeons, interventional radiologists, geneticists, vascular biologists, biomedical engineers, and computational scientists will be critical to translate emerging scientific insights into patient care. By leveraging these collaborative advances, the field can move toward precision therapies that improve outcomes, reduce recurrence, and ultimately lessen the burden of AVM-related morbidity and mortality.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all members in Surgical Vascular Research Labs at DeWitt Daughtry Family Department of Surgery, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine for helpful discussion and suggestion.:

Conflicts of Interest

Authors: Yan Li, Gianni Walker, Bao-Ngoc Nguyen, Arash Bornak, and Sapna K. Deo have no commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. Authors: Zhao-Jun Liu (ZJL) and Dr. Omaida C. Velazquez (OCV) declare the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or presentation and/or publication of some aspects that are indirectly related to this work: E-selectin gene modification technologies aimed as pro neovascularization technologies were developed in our research laboratory and patented/licensed by the University of Miami. These E-Selectin technologies are currently under pre-clinical development by Ambulero Inc., a new start-up company out of the University of Miami that focuses on developing new vascular treatments for ischemic tissue conditions and limb salvage. ZJL and OCV serve as Ambulero Inc. consultants and chief scientific and medical advisory officers, respectively and are co-inventors of the E-Selectin technologies and are minority shareholders in Ambulero Inc. ZJL and OCV are also funded by the NIH/NHLBI and philanthropy in preclinical investigations of E-Selectin technologies and other pro neovascularization technologies.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AVM(s) |

Arteriovenous Malformation(s) |

cAVM(s)

HHT |

Cerebral Arteriovenous Malformation(s)

Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia |

| ENG |

Endoglin |

ACVRL1

SMAD4

KRAS

MAP2K1

PIK3CA

MRI

CM-AVM

TGF-β

VEGF

CNS

DSA

SWI

CT

CTA

3D-RA

PET

AI

NBCA

ICG |

Activin Receptor-like Kinase 1

Mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 4

Kirsten Rat Sarcoma Virus

Mitogen-activated Protein Kinase Kinase 1

Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-Bisphosphate 3-Kinase Catalytic Subunit Alpha

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Capillary malformation-Arteriovenous Malformation

Transforming Growth Factor–β

Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor

Central Nervous System

Digital Subtraction Angiography

Susceptibility-Weighted Imaging

Computed Tomography

Computed Tomography Angiography

Three-Dimensional Rational Angiography

Positron Emission Tomography

Artificial Intelligence

N-Butyl Cyanoacrylate

Indocyanine Green |

References

- Maddy, K. , et al., An updated review on the genetics of arteriovenous malformations. Gene Protein Dis, 2023. 2(2). [CrossRef]

- Osbun, J.W., M. R. Reynolds, and D.L. Barrow, Arteriovenous malformations: epidemiology, clinical presentation, and diagnostic evaluation. Handb Clin Neurol, 2017. 143: p. 25-29. [CrossRef]

- Schimmel, K. , et al., Arteriovenous Malformations-Current Understanding of the Pathogenesis with Implications for Treatment. Int J Mol Sci, 2021. 22(16). [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, M. , et al., Pathogenesis of Arteriovenous Malformations in the Absence of Endoglin. Circulation Research, 2010. 106(8): p. 1425-1433. [CrossRef]

- Casf, N. , Arteriovenous Malformation: Concepts on Physiopathology and Treatment. Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Therapy, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Beltramello, A. , et al., Operative classification of brain arteriovenous malformations. Interv Neuroradiol, 2008. 14(1): p. 9-19. [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.-B. , New classification of congenital vascular malformations (CVMs). Reviews in Vascular Medicine, 2015. 3(3): p. 1-5. [CrossRef]

- Goldenberg, D.C. , et al., Updated Classification of Vascular Anomalies: A living document from the International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies Classification Group. Journal of Vascular Anomalies, 2025. 6(2): p. e113. [CrossRef]

- Oomen, K.P.Q. and V.B. Wreesmann, Current classification of vascular anomalies of the head and neck. Journal of Oral Pathology & Medicine, 2022. 51(10): p. 830-836. [CrossRef]

- Shaligram, S.S. , et al., Risk factors for hemorrhage of brain arteriovenous malformation. CNS Neurosci Ther, 2019. 25(10): p. 1085-1095. [CrossRef]

- Faughnan, M.E. , et al., International guidelines for the diagnosis and management of hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia. J Med Genet, 2011. 48(2): p. 73-87. [CrossRef]

- Al-Shahi, R. and C. Warlow, A systematic review of the frequency and prognosis of arteriovenous malformations of the brain in adults. Brain, 2001. 124(10): p. 1900-1926. [CrossRef]

- Mohr, J.P. , et al., Medical management with or without interventional therapy for unruptured brain arteriovenous malformations (ARUBA): a multicentre, non-blinded, randomised trial. Lancet, 2014. 383(9917): p. 614-21. [CrossRef]

- Bokhari MR, B.S. , Arteriovenous Malformation of the Brain. StatPearls, 2023.

- Oulasvirta, E. , et al., Recurrence of brain arteriovenous malformations in pediatric patients: a long-term follow-up study. Acta Neurochir (Wien), 2023. 165(6): p. 1565-1573. [CrossRef]

- Scherschinski, L. , et al., Localized conditional induction of brain arteriovenous malformations in a mouse model of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Angiogenesis, 2023. 26(4): p. 493-503. [CrossRef]

- Hillman, J. , Population-based analysis of arteriovenous malformation treatment. J Neurosurg, 2001. 95(4): p. 633-7. [CrossRef]

- Murphy, P.A. , et al., Notch4 normalization reduces blood vessel size in arteriovenous malformations. Sci Transl Med, 2012. 4(117): p. 117ra8. [CrossRef]

- Crist, A.M. , et al., Vascular deficiency of Smad4 causes arteriovenous malformations: a mouse model of Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia. Angiogenesis, 2018. 21(2): p. 363-380. [CrossRef]

- Ricciardelli, A.R. , et al., From bench to bedside: murine models of inherited and sporadic brain arteriovenous malformations. Angiogenesis, 2025. 28(2): p. 15. [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.-B. , et al., Management of arteriovenous malformations: a multidisciplinary approach. Journal of Vascular Surgery, 2004. 39(3): p. 590-600. [CrossRef]

- Bruno, C.A., Jr. and P.M. Meyers, Endovascular management of arteriovenous malformations of the brain. Interv Neurol, 2013. 1(3-4): p. 109-23. [CrossRef]

- Plasencia, A.R. and A. Santillan, Embolization and radiosurgery for arteriovenous malformations. Surg Neurol Int, 2012. 3(Suppl 2): p. S90-s104. [CrossRef]

- Han, C. , et al., VEGF neutralization can prevent and normalize arteriovenous malformations in an animal model for hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia 2. Angiogenesis, 2014. 17(4): p. 823-830. [CrossRef]

- Snellings, D.A. , et al., Somatic Mutations in Vascular Malformations of Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia Result in Bi-allelic Loss of ENG or ACVRL1. Am J Hum Genet, 2019. 105(5): p. 894-906. [CrossRef]

- Winkler, E.A. , et al., A single-cell atlas of the normal and malformed human brain vasculature. Science, 2022. 375(6584): p. eabi7377. [CrossRef]

- Revencu, N. , et al., RASA1 mutations and associated phenotypes in 68 families with capillary malformation-arteriovenous malformation. Hum Mutat, 2013. 34(12): p. 1632-41. [CrossRef]

- ZhuGe, Q. , et al., Notch-1 signalling is activated in brain arteriovenous malformations in humans. Brain, 2009. 132(Pt 12): p. 3231-41. [CrossRef]

- Bai, J. , et al., Ephrin B2 and EphB4 selectively mark arterial and venous vessels in cerebral arteriovenous malformation. Journal of International Medical Research, 2014. 42(2): p. 405-415. [CrossRef]

- Fehnel, K.P. , et al., Dysregulation of the EphrinB2−EphB4 ratio in pediatric cerebral arteriovenous malformations is associated with endothelial cell dysfunction in vitro and functions as a novel noninvasive biomarker in patients. Experimental & Molecular Medicine, 2020. 52(4): p. 658-671. [CrossRef]

- Aiyappan, S.K., U. Ranga, and S. Veeraiyan, Doppler Sonography and 3D CT Angiography of Acquired Uterine Arteriovenous Malformations (AVMs): Report of Two Cases. J Clin Diagn Res, 2014. 8(2): p. 187-9. [CrossRef]

- Irtyuga, O. , et al., NOTCH1 Mutations in Aortic Stenosis: Association with Osteoprotegerin/RANK/RANKL. Biomed Res Int, 2017. 2017: p. 6917907. [CrossRef]

- Song, W. , et al., Investigation of a transgenic mouse model of familial dilated cardiomyopathy. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology, 2010. 49(3): p. 380-389. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, V.F. , et al., Imaging of peripheral vascular malformations - current concepts and future perspectives. Mol Cell Pediatr, 2021. 8(1): p. 19. [CrossRef]

- Zuurbier, S.M. and R. Al-Shahi Salman, Interventions for treating brain arteriovenous malformations in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2019. 9(9): p. Cd003436. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.J. , et al., Brain arteriovenous malformations: A review of natural history, pathobiology, and interventions. Neurology, 2020. 95(20): p. 917-927. [CrossRef]

- Abdelilah-Seyfried, S. and R. Ola, Shear stress and pathophysiological PI3K involvement in vascular malformations. J Clin Invest, 2024. 134(10). [CrossRef]

- Nakisli, S. , et al., Pericytes and vascular smooth muscle cells in central nervous system arteriovenous malformations. Front Physiol, 2023. 14: p. 1210563. [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.Y. , et al., Pathophysiology in Brain Arteriovenous Malformations: Focus on Endothelial Dysfunctions and Endothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition. Biomedicines, 2024. 12(8): p. 1795. [CrossRef]

- Liberman, F. , et al., High-output heart failure due to arteriovenous malformation treated by endovascular embolisation. Br J Cardiol, 2022. 29(3): p. 26. [CrossRef]

- Gore, A.V. , et al., Vascular development in the zebrafish. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med, 2012. 2(5): p. a006684. [CrossRef]

- Krebs, L.T. , et al., Notch1 activation in mice causes arteriovenous malformations phenocopied by ephrinB2 and EphB4 mutants. Genesis, 2010. 48(3): p. 146-50. [CrossRef]

- Kader, A. , et al., The influence of hemodynamic and anatomic factors on hemorrhage from cerebral arteriovenous malformations. Neurosurgery, 1994. 34(5): p. 801-7; discussion 807-8. [CrossRef]

- Tanweer, O. , et al., A comparative review of the hemodynamics and pathogenesis of cerebral and abdominal aortic aneurysms: lessons to learn from each other. J Cerebrovasc Endovasc Neurosurg, 2014. 16(4): p. 335-49. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.M. , et al., Genetic and epigenetic mechanisms in the development of arteriovenous malformations in the brain. Clin Epigenetics, 2016. 8: p. 78. [CrossRef]

- Stapf, C. , et al., Epidemiology and natural history of arteriovenous malformations. Neurosurg Focus, 2001. 11(5): p. e1. [CrossRef]

- van Beijnum, J. , et al., Treatment of brain arteriovenous malformations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Jama, 2011. 306(18): p. 2011-9. [CrossRef]

- Gross, B.A. and R. Du, Natural history of cerebral arteriovenous malformations: a meta-analysis. J Neurosurg, 2013. 118(2): p. 437-43. [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, F. , et al., Mutations in RASA1 and GDF2 identified in patients with clinical features of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Hum Genome Var, 2015. 2: p. 15040. [CrossRef]

- McDonald, J. , et al., Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia: genetics and molecular diagnostics in a new era. Front Genet, 2015. 6: p. 1. [CrossRef]

- Li, F. , et al., Endothelial Smad4 maintains cerebrovascular integrity by activating N-cadherin through cooperation with Notch. Dev Cell, 2011. 20(3): p. 291-302. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.M. , et al., DNA methylation signatures on vascular differentiation genes are aberrant in vessels of human cerebral arteriovenous malformation nidus. Clinical Epigenetics, 2022. 14(1): p. 127. [CrossRef]

- Drapé, E. , et al., Brain arteriovenous malformation in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia: Recent advances in cellular and molecular mechanisms. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 2022. 16. [CrossRef]

- Xu, M., H. Xu, and Z. Qin, Animal Models in Studying Cerebral Arteriovenous Malformation. Biomed Res Int, 2015. 2015: p. 178407. [CrossRef]

- Koyalakonda, S.P. and J. Pyatt, High output heart failure caused by a large pelvic arteriovenous malformation. JRSM Short Rep, 2011. 2(8): p. 66. [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.J. , et al., Novel brain arteriovenous malformation mouse models for type 1 hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. PLoS One, 2014. 9(2): p. e88511. [CrossRef]

- Cho, D. , et al., Two cases of high output heart failure caused by hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Korean Circ J, 2012. 42(12): p. 861-5. [CrossRef]

- Carlson, T.R. , et al., Endothelial expression of constitutively active Notch4 elicits reversible arteriovenous malformations in adult mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2005. 102(28): p. 9884-9. [CrossRef]

- Tual-Chalot, S. , et al., Loss of Endothelial Endoglin Promotes High-Output Heart Failure Through Peripheral Arteriovenous Shunting Driven by VEGF Signaling. Circulation Research, 2020. 126(2): p. 243-257. [CrossRef]

- Jain, M.S., H. M. Do, and T.F. Massoud, Computational Network Modeling of Intranidal Hemodynamic Compartmentalization in a Theoretical Three-Dimensional Brain Arteriovenous Malformation. Front Physiol, 2019. 10: p. 1250. [CrossRef]

- Chang, W. , et al., Hemodynamic changes in patients with arteriovenous malformations assessed using high-resolution 3D radial phase-contrast MR angiography. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol, 2012. 33(8): p. 1565-72. [CrossRef]

- Dolan, J.M., J. Kolega, and H. Meng, High wall shear stress and spatial gradients in vascular pathology: a review. Ann Biomed Eng, 2013. 41(7): p. 1411-27. [CrossRef]

- Walcott, B.P. , et al., Molecular, Cellular, and Genetic Determinants of Sporadic Brain Arteriovenous Malformations. Neurosurgery, 2016. 63 Suppl 1(Suppl 1 CLINICAL NEUROSURGERY): p. 37-42. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, C.M. , et al., Mouse Models of Cerebral Arteriovenous Malformation. Stroke, 2016. 47(1): p. 293-300. [CrossRef]

- Payne, L.B. , et al., The pericyte microenvironment during vascular development. Microcirculation, 2019. 26(8): p. e12554. [CrossRef]

- Murakami, M. and M. Simons, Regulation of vascular integrity. J Mol Med (Berl), 2009. 87(6): p. 571-82. [CrossRef]

- Pan, P. , et al., The role of mural cells in hemorrhage of brain arteriovenous malformation. Brain Hemorrhages, 2021. 2(1): p. 49-56. [CrossRef]

- Scimone, C. , et al., High-Throughput Sequencing to Detect Novel Likely Gene-Disrupting Variants in Pathogenesis of Sporadic Brain Arteriovenous Malformations. Frontiers in Genetics, 2020. 11. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W., K. M. Morgan, and S.R. Pine, Activation of the Notch1 Stem Cell Signaling Pathway during Routine Cell Line Subculture. Front Oncol, 2014. 4: p. 211. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. , et al., Constitutively active Notch1 signaling promotes endothelial-mesenchymal transition in a conditional transgenic mouse model. Int J Mol Med, 2014. 34(3): p. 669-676. [CrossRef]

- Atri, D. , et al., Endothelial signaling and the molecular basis of arteriovenous malformation. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 2014. 71(5): p. 867-883. [CrossRef]

- Gridley, T. , Notch signaling during vascular development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2001. 98(10): p. 5377-5378. [CrossRef]

- Gridley, T. , Notch signaling in the vasculature. Curr Top Dev Biol, 2010. 92: p. 277-309. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C. , et al., Actin cytoskeleton regulator Arp2/3 complex is required for DLL1 activating Notch1 signaling to maintain the stem cell phenotype of glioma initiating cells. Oncotarget, 2017. 8(20): p. 33353-33364. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B. , et al., Notch signaling pathway: architecture, disease, and therapeutics. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, 2022. 7(1): p. 95. [CrossRef]

- Bray, S.J. , Notch signalling: a simple pathway becomes complex. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 2006. 7(9): p. 678-689. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.Q. , et al., Roles of notch signaling pathway and endothelial-mesenchymal transition in vascular endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci, 2018. 22(19): p. 6485-6491. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. , et al., Notch-Tnf signalling is required for development and homeostasis of arterial valves. Eur Heart J, 2017. 38(9): p. 675-686. [CrossRef]

- Holderfield, M.T. and C.C.W. Hughes, Crosstalk Between Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor, Notch, and Transforming Growth Factor-β in Vascular Morphogenesis. Circulation Research, 2008. 102(6): p. 637-652. [CrossRef]

- Kopan, R. , Notch signaling. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol, 2012. 4(10). [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.J. , et al., Notch activation induces endothelial cell senescence and pro-inflammatory response: implication of Notch signaling in atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis, 2012. 225(2): p. 296-303. [CrossRef]

- Fish, J.E. and J.D. Wythe, The molecular regulation of arteriovenous specification and maintenance. Developmental Dynamics, 2015. 244(3): p. 391-409. [CrossRef]

- Atri, D. , et al., Endothelial signaling and the molecular basis of arteriovenous malformation. Cell Mol Life Sci, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Russo, T.A. , et al., Altered shear stress on endothelial cells leads to remodeling of extracellular matrix and induction of angiogenesis. PLoS One, 2020. 15(11): p. e0241040. [CrossRef]

- Wei, T. , et al., Extracranial arteriovenous malformations demonstrate dysregulated TGF-β/BMP signaling and increased circulating TGF-β1. Sci Rep, 2022. 12(1): p. 16612. [CrossRef]

- Munger, J.S. and D. Sheppard, Cross talk among TGF-β signaling pathways, integrins, and the extracellular matrix. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol, 2011. 3(11): p. a005017. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-J. , et al., Brain arteriovenous malformations. Neurology, 2020. 95(20): p. 917-927. [CrossRef]

- Ajiboye, N. , et al., Cerebral arteriovenous malformations: evaluation and management. ScientificWorldJournal, 2014. 2014: p. 649036. [CrossRef]

- Conger, A. , et al., Diagnosis and evaluation of intracranial arteriovenous malformations. Surg Neurol Int, 2015. 6: p. 76. [CrossRef]

- da Costa, L. , et al., The natural history and predictive features of hemorrhage from brain arteriovenous malformations. Stroke, 2009. 40(1): p. 100-5. [CrossRef]

- Abdelilah-Seyfried, S. , Epigenetics enters the stage in vascular malformations. J Clin Invest, 2024. 134(15). [CrossRef]

- Hao, Q. , et al., Increased tissue perfusion promotes capillary dysplasia in the ALK1-deficient mouse brain following VEGF stimulation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol, 2008. 295(6): p. H2250-6. [CrossRef]

- Achey, R. , et al., Computational Fluid–Structure Interactions in the Human Cerebrovascular System: Part 2—A Review of Current Applications of Computational Fluid Dynamics and Structural Mechanics in Cerebrovascular Pathophysiology. Journal of Engineering and Science in Medical Diagnostics and Therapy, 2022. 5(3). [CrossRef]

- Tranvinh, E. , et al., Contemporary Imaging of Cerebral Arteriovenous Malformations. American Journal of Roentgenology, 2017. 208(6): p. 1320-1330. [CrossRef]

- Collins, K.A., C. E. Korcarz, and R.M. Lang, Use of echocardiography for the phenotypic assessment of genetically altered mice. Physiological Genomics, 2003. 13(3): p. 227-239. [CrossRef]

- Drapé, E. , et al., Brain arteriovenous malformation in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia: Recent advances in cellular and molecular mechanisms. Front Hum Neurosci, 2022. 16: p. 1006115. [CrossRef]

- Shibuya, M. , Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) and Its Receptor (VEGFR) Signaling in Angiogenesis: A Crucial Target for Anti- and Pro-Angiogenic Therapies. Genes Cancer, 2011. 2(12): p. 1097-105. [CrossRef]

- Maimon, S. , et al., Brain arteriovenous malformation treatment using a combination of Onyx and a new detachable tip microcatheter, SONIC: short-term results. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol, 2010. 31(5): p. 947-54. [CrossRef]

- Kilburg, C. , et al., Novel use of flow diversion for the treatment of aneurysms associated with arteriovenous malformations. Neurosurg Focus, 2017. 42(6): p. E7. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. , et al., Ephrin-B2 controls VEGF-induced angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. Nature, 2010. 465(7297): p. 483-486. [CrossRef]

- Raj, J.A. and M. Stoodley, Experimental Animal Models of Arteriovenous Malformation: A Review. Vet Sci, 2015. 2(2): p. 97-110. [CrossRef]

- Gory, S. , et al., The Vascular Endothelial-Cadherin Promoter Directs Endothelial-Specific Expression in Transgenic Mice. Blood, 1999. 93(1): p. 184-192. [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.J. , et al., Minimal homozygous endothelial deletion of Eng with VEGF stimulation is sufficient to cause cerebrovascular dysplasia in the adult mouse. Cerebrovasc Dis, 2012. 33(6): p. 540-7. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L. , et al., Murine peripherin gene sequences direct Cre recombinase expression to peripheral neurons in transgenic mice. FEBS Letters, 2002. 523(1): p. 68-72. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, S. , et al., A mouse model of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia generated by transmammary-delivered immunoblocking of BMP9 and BMP10. Scientific Reports, 2016. 6(1): p. 37366. [CrossRef]

- Santander, N. , et al., Lack of Flvcr2 impairs brain angiogenesis without affecting the blood-brain barrier. J Clin Invest, 2020. 130(8): p. 4055-4068. [CrossRef]

- Triano, M.J. , et al., Embolic Agents and Microcatheters for Endovascular Treatment of Cerebral Arteriovenous Malformations. World Neurosurg, 2020. 141: p. 383-388. [CrossRef]

- Davis, R.B. , et al., Notch signaling pathway is a potential therapeutic target for extracranial vascular malformations. Scientific Reports, 2018. 8(1): p. 17987. [CrossRef]

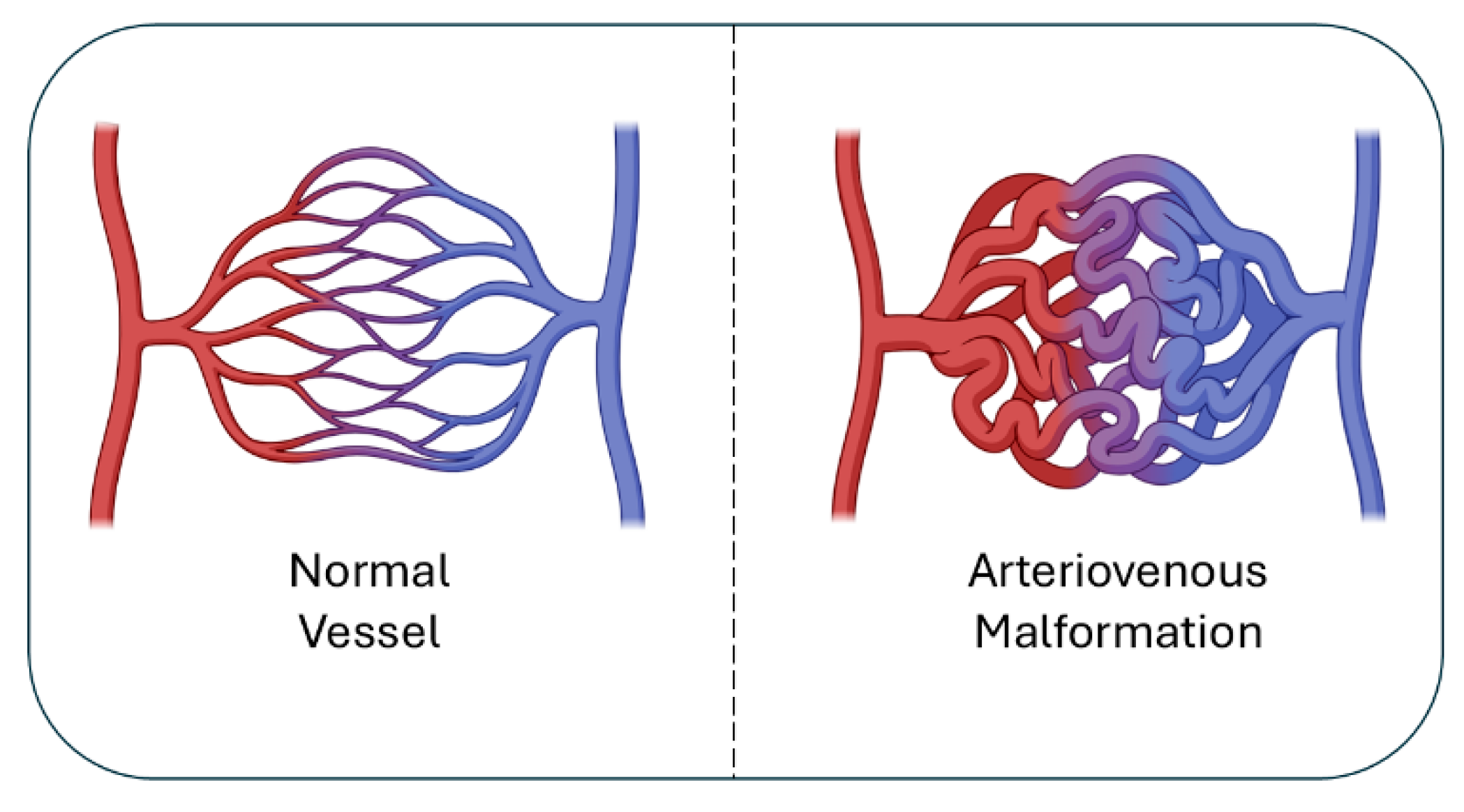

Figure 1.

Normal vs. AVM vasculature. Normal vessels (left) show orderly artery-capillary-vein connections, while AVMs (right) form a tangled nidus with direct artery-vein shunts, leading to high-flow, fragile vessels.

Figure 1.

Normal vs. AVM vasculature. Normal vessels (left) show orderly artery-capillary-vein connections, while AVMs (right) form a tangled nidus with direct artery-vein shunts, leading to high-flow, fragile vessels.

Figure 2.

Pathogenesis of AVMs. AVM formation reflects multiple converging mecha-nisms: genetic susceptibility (ENG, ACVRL1, SMAD4 mutations; VEGF “two-hit” mod-el), somatic mosaicism (KRAS, MAP2K1, PIK3CA activating RAS/MAPK & PI3K/AKT), perturbed signaling (Notch4 dysregulation → AV shunting), hemodynamic stress (shear stress, disturbed flow, mural cell loss), and inflammation (TNF-α, IL-6–driven endothelial proliferation, leukocyte recruitment, ECM degradation). Together, these processes destabilize vessels and drive AVM progression.

Figure 2.

Pathogenesis of AVMs. AVM formation reflects multiple converging mecha-nisms: genetic susceptibility (ENG, ACVRL1, SMAD4 mutations; VEGF “two-hit” mod-el), somatic mosaicism (KRAS, MAP2K1, PIK3CA activating RAS/MAPK & PI3K/AKT), perturbed signaling (Notch4 dysregulation → AV shunting), hemodynamic stress (shear stress, disturbed flow, mural cell loss), and inflammation (TNF-α, IL-6–driven endothelial proliferation, leukocyte recruitment, ECM degradation). Together, these processes destabilize vessels and drive AVM progression.

Figure 3.

AVM diagnosis requires a tailored, patient-specific approach that integrates clinical evaluation with multimodal imaging, including digital subtraction angiography (DSA), magnetic resonance imaging and magnetic resonance angiography (MRI/MRA) with perfusion and susceptibility sequences, computed tomography angiography (CTA), Doppler ultrasound, and 3D rotational angiography, and arterial spin labeling (ASL) and 4D flow techniques refining hemodynamic assessment.

Figure 3.

AVM diagnosis requires a tailored, patient-specific approach that integrates clinical evaluation with multimodal imaging, including digital subtraction angiography (DSA), magnetic resonance imaging and magnetic resonance angiography (MRI/MRA) with perfusion and susceptibility sequences, computed tomography angiography (CTA), Doppler ultrasound, and 3D rotational angiography, and arterial spin labeling (ASL) and 4D flow techniques refining hemodynamic assessment.

Figure 4.

Current treatment strategies for AVMs. Optimal AVM management increasingly relies on multimodal sequencing strategies that integrate endovascular, surgical, and radiosurgical approaches. Endovascular embolization may be used preoperatively to reduce flow and nidus size, as an adjunct to stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS), or as a stand-alone therapy in select lesions. Microsurgical resection remains the most definitive curative option for accessible AVMs, particularly in low-grade lesions, but carries risks of hemorrhage and neurological morbidity. Stereotactic radiosurgery provides a non-invasive alternative for small or surgically inaccessible AVMs, though obliteration may take years and hemorrhage risk persists during the latency period. Hybrid and staged strategies, such as embolization followed by surgery or SRS, can maximize efficacy and minimize complications, especially for large or complex AVMs. Salvage approaches are employed when recurrence or incomplete obliteration occurs. Together, these treatment modalities highlight the importance of individualized, multidisciplinary planning to balance cure, risk reduction, and functional outcomes.

Figure 4.

Current treatment strategies for AVMs. Optimal AVM management increasingly relies on multimodal sequencing strategies that integrate endovascular, surgical, and radiosurgical approaches. Endovascular embolization may be used preoperatively to reduce flow and nidus size, as an adjunct to stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS), or as a stand-alone therapy in select lesions. Microsurgical resection remains the most definitive curative option for accessible AVMs, particularly in low-grade lesions, but carries risks of hemorrhage and neurological morbidity. Stereotactic radiosurgery provides a non-invasive alternative for small or surgically inaccessible AVMs, though obliteration may take years and hemorrhage risk persists during the latency period. Hybrid and staged strategies, such as embolization followed by surgery or SRS, can maximize efficacy and minimize complications, especially for large or complex AVMs. Salvage approaches are employed when recurrence or incomplete obliteration occurs. Together, these treatment modalities highlight the importance of individualized, multidisciplinary planning to balance cure, risk reduction, and functional outcomes.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).