1. Introduction

The Chinese have a long history in Asia, particularly in the southeastern part of the continent. They were a closed society with moderate relations with their neighbors. There were also times when the Chinese expanded westwards[

1], and their artistic works show some similarities to those of the Arab and Seljuk groups, the latter being Turkish peoples. I assume that, due to their shared geographical location in ancient and medieval times, these groups had numerous opportunities to influence each other’s artistic creations, leading them to favor similar symmetries in the patterns I am examining here to determine their artistic preferences.

The 17 so-called wallpaper groups are periodic patterns that extend across the surface without gaps or overlaps and exhibit symmetry [

2]. One characteristic of the cultural group in which a work of art was created is its preference for symmetry, which is reflected in the 17 groups. Such characteristics of a civilization are therefore determined by the distribution of the number of wallpaper symmetries that we observe in its works of art [

3]. I have taken up this concept and used statistical methods to examine the tessellated ornaments of some cultural groups. The results show that the Arabs, the Seljuk Empire, and the Seljuks of Rum had similar ornaments, while the classical (ancient) Hellenes, Armenians, and Eastern Romans created works of art with comparable symmetry [

4]. It is interesting to note that Persia developed its own style independently of both groups [

5].

2. Chinese Wallpapers

I have studied periodic ornaments from various civilizations of antiquity and the Middle Ages. The Chinese Empire [

1] promises a wealth of artwork, applied to ceramics, wood, paper, or fabric. I hypothesize that Chinese design, especially before and during the

Tang Dynasty (618 – 907), may have received and exerted a certain influence through exchanges with the Turkic-speaking peoples with whom they shared their land and extensive borders. After 650, the Arabs reached Transoxiana (Sogdia) and came into first contact with the Chinese. Thereafter, they interacted both militarily overland and through maritime trade. China is not only the source of porcelain, but also of silk, paper, and various innovations. In return, China received silver and wool from the West. Therefore, the roots of trade with Constantinople and further with the West in general are referred to as the

Silk Road, which formed the basis of Sino-European relations. The trade routes can be traced back to the 8th century, but there is no reliable information about earlier times. Therefore, we refer to the patterns of Chinese decorative art, whose symmetry is a fingerprint of the craftsmen who created them.

There are numerous reports on Chinese patterns, mostly from private porcelain collections [

6]. I was unable to find a specific source for Chinese wallpaper. Therefore, I rely on Owen Jones’ classic work,

The Grammar of Ornament [

7], in which he presents ornaments from various significant cultural groups, including China. I was able to identify 53 different Chinese works of art. Typical examples are shown in

Figure 1. Due to copyright restrictions, I redrew six examples in black and white and simplified them to their essential elements. The patterns are often found on porcelain objects, with the exception of the pattern at the top right, which is used on fabrics and paintings. The swastica-like motifs, which are common in East Asian iconography, symbolize good fortune and eternity. Together with the corresponding symmetry groups, these ornaments and their percentage occurrence are summarized in

Table 1.

3. Results

I have previously presented the symmetry properties of different cultural groups and compared them with each other by calculating their correlation. For this purpose, I used

multidimensional scaling (MDS),

hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA), the

heat-map method, and

principal component analysis (PCA) [

5]. I have found PCA [

8,

9] to be a straightforward approach, which I will use for the present comparison in addition to HCA. It is a linear dimension-reduction technique that preserves the most important features of the data while reducing them to their principal components based on their correlation or covariance structure. Essentially, PCA transforms correlated variables into a new set of uncorrelated variables called principal components, which represent most of the variance in the data.

Table 2 shows the preferences of wallpaper groups in the artwork of nine ancient and medieval civilizations. The symmetries shown as rows are grouped into rotational symmetries, i.e.,

n = 1, 2, 3, 4, and

6. For each cultural group, the respective symmetry is listed as the number of occurrence (#) and its percentage share (%). This table forms the basis for calculating the correlations between the artworks of these peoples.

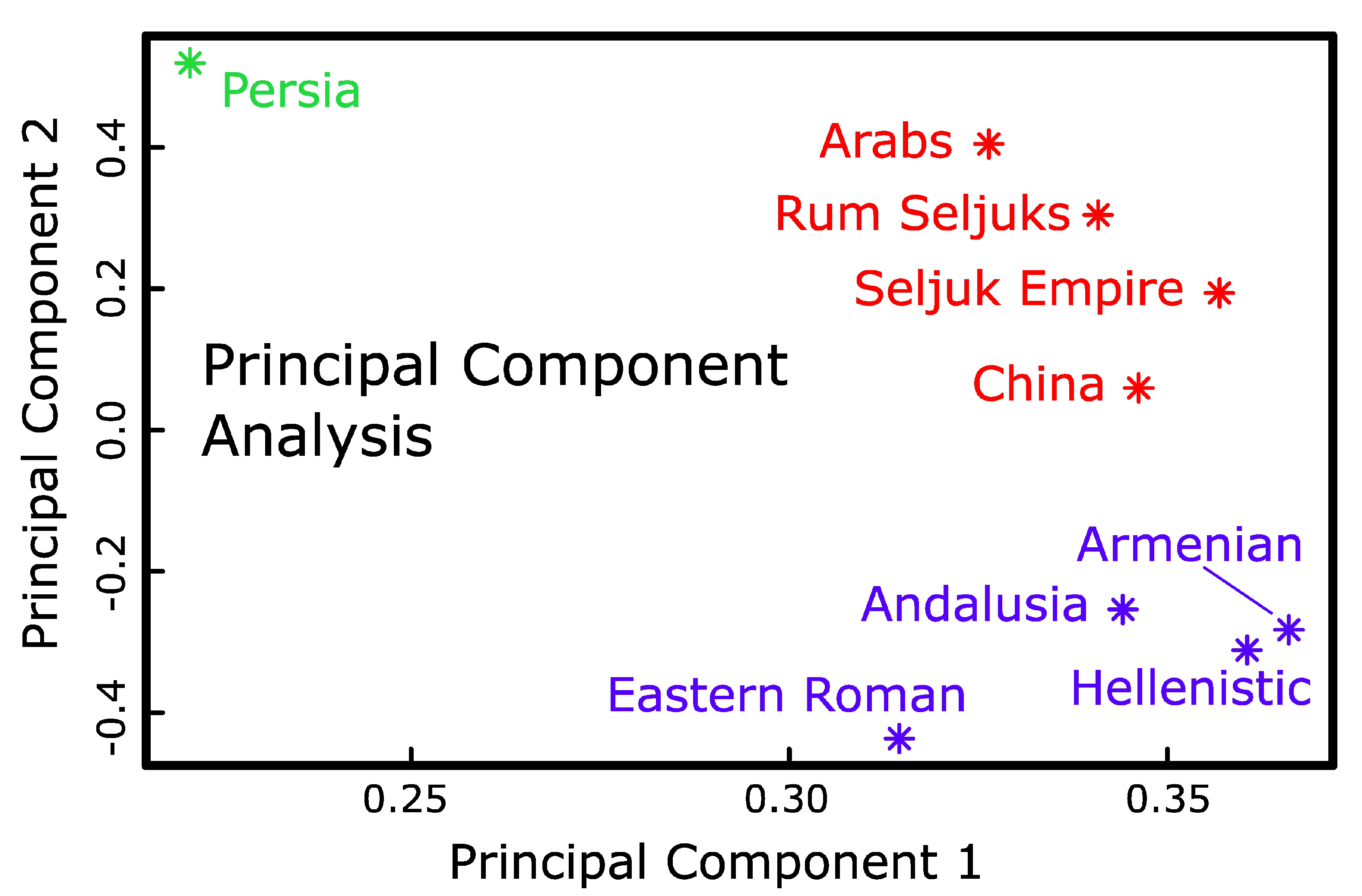

Figure 2 compiles the PCA results for the artistic output of nine cultural groups, including China. The two axes of the figure are the result of an arbitrary linear combination of the original axes in the PCA calculation. As previously documented, the Hellens, Armenians, Eastern Romans, and Andalusians form one group, while the Arabs, Seljuk Empire and Seljuks of Rum appear to have created similarly symmetrical works of art. Persia created its own design before and after the Muslim conquest [

5]. Interestingly, Chinese ornamentation resembles that of the Muslim group, i.e., Arab and Turkish culture. Arab art and Muslim art are terms that are sometimes used synonymously. I emphasize that although the Arabs are responsible for spreading Islam in Asia and Africa, Muslim art is the product of many cultural groups, not just the Arabs.

The reliability/quality of the PCA can be examined using the

scree plot [

10], which documents the relative variances of the individual new variables, the principal components. In other words, the scree plot shows the percentage explanation of each principal component to the data. In this case, 72.0 %, 13.8 %, 8.7 %, 2.9 %, and 1.3 % of the information is contained in the first five principal components. The representation with only the first two components in

Figure 2 therefore accounts for (72.0 % + 13.8 %) 85.8 % of the data.

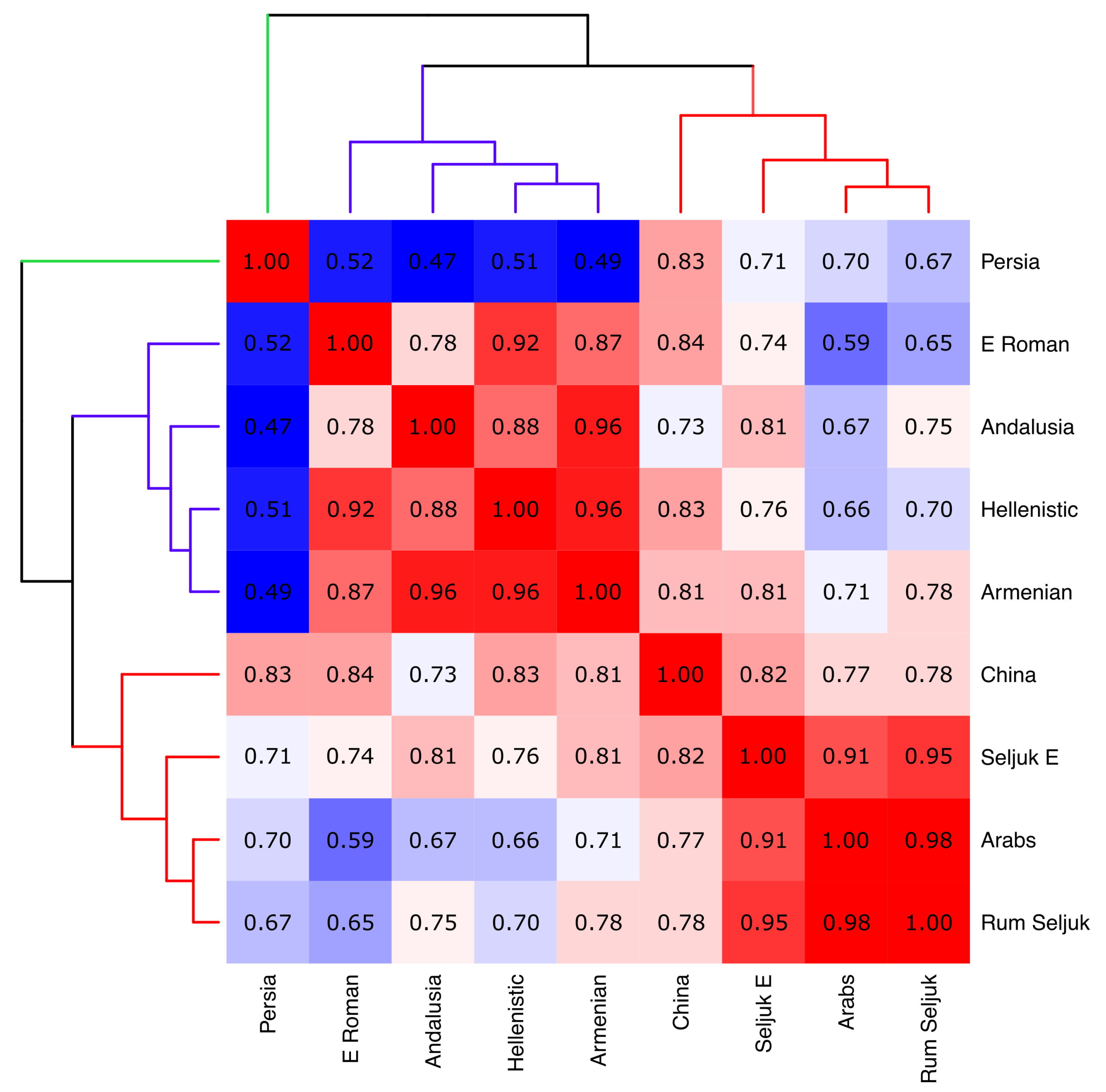

To substantiate these results, we applied the heat-map method to the observations on the nine cultural groups. Heat map is the name given to a function that contains a clustering algorithm [

11]. We used the pairwise cosine correlation of the nine medieval groups in the algorithm. HCA, which is integrated into the heat-map algorithm, rearranges both the variables and the observations according to their similarity.

Figure 3 shows a visual representation of the result. The degree of similarity, expressed in quantitative terms, is represented by colors, with red denoting the highest (hottest) similarity, i.e., the self-similarity, and blue denoting the lowest (coolest) similarity, as the name of the algorithm suggests. The algorithm also provides a

dendrogram for the civilizations studied, one is located at the top, another to the left of the heat map. A dendrogram is a direct representation of the results of HCA, an agglomerative technique for data analysis. In other words, it shows the grouping of variables. The figure illustrates the aggregation of Muslim (red lines in the dendrogram) and Greco-Roman (blue lines in the dendrogram) civilizations. This dendrogram supports the results shown in

Figure 2 and places Chinese artefacts close to the Muslim group, namely next to the Turkish Seljuks and the Arabs.

4. Discussion

The results reveal similarities between the symmetry properties of two-dimensional periodic patterns created by the Arabs, Turkic peoples, and Chinese civilization. The reason for this most likely lies in the shared history of these peoples, especially their shared geography, where their culture has its roots. Since the East and West are connected by the vast Eurasian steppe, we consider the peoples who have inhabited these areas since the first millennium, even though the Chinese have lived in the eastern part for longer. This similarity in art thus paved the way for the migration of Chinese art to the West, and similarly for science and technology. The Eurasian highlands were long home to nomads who spoke related Turkic dialects. Later, with the rise of Islam in the 7th century, Arabs gained prominence in these areas. The Chinese literature is an important source of historical information about this period, and Wikipedia offers extensive documentation on the subject.

To understand the migration of Chinese culture from east to west, we need to look at the nomadic peoples who lived on China’s northern and western borders. Two thousand years ago, we encounter the

Xianbei as a nomadic monarchy that settled the Eurasian highlands from the north of the Black Sea to the southeast of present-day Mongolia. It was a tribal confederation that was hostile to its neighbors. After the third century, it disbanded and a similar tribal dynasty, the

Rouran Khaganate, emerged [

12]. Similar to the previous group, the rulers were called

khagans or simply

khans.

Nomadic feudalism is the best description for the hostile confederation. Their fighters were usually victorious over their opponents who traveled on foot, as they were fierce warriors who rode small but agile horses. They streched from Manchuria in the east almost to present-day Hungary in the west. The Rouran tribes had Turkic characteristics, while the Xianbei had Mongolian characteristics. One indication of urbanization is the fact that the Rouran are known to have their headquarters in Gansu in northwestern China. However, the Rouran Khaganate collapsed in 552 when the rebellious

Göktürks took control of the confederation [

13]. The Göktürk Khaganate is also known as the

First Turkic Empire. They were a clan that specialized in blacksmithing and lived as oppressed members of Rouran society. After coming to power, they had to fight some of their neighbors to secure their vast lands, while maintaining friendly relations with the Chinese also through interfaith marriages.

Due to internal conflicts, the Göktürk Khaganate split into western and eastern parts in 603. The eastern part was incorporated into the Chinese system after the Chinese army of the Tang dynasty defeated it in 630 [

13]. The Western Khaganate, on the other hand, established close relations with Byzantium and fought against their common enemy, the Iranian Sassanid Empire. At that time, the western part was no longer able to defend itself against the Tang’s western campaign. In 658, it too was annexed by the Chinese Tang dynasty. Despite the collapse of the Göktürks, Turkic language and culture spread throughout Central Asia. The first steppe empire to come into contact with Byzantium, Persia, and China –three major urban civilizations– was the Turkic Khaganate [

14].

After the Tang Chinese took control of the entire Turkic Khaganate in 658, the

Uighurs, another Turkic tribal confederation, joined forces with the Chinese [

15]. Their union was cemented by marriage ties, and by 750 they had reached their zenith. As the Turkic-Chinese alliance spread across Eurasia, the Arabs, inspired by their newly discovered ethnic religion, Islam, took steps to spread their faith outside the Arabian Peninsula. Their eastern campaign began during the

Rashidun period, which lasted from 632 to 661. Omar (634 – 644) conquered Byzantine Egypt and fought against the Sassanid Empire in Persia. Uthman conquered large parts of Syria, Armenia, Khorasan in eastern Persia, and Sindh, thus sharing the borders with India. During the occupation of Persia, they converted the Persians to Islam, and their campaigns of Islamization and Arabization lasted for several decades. [

16].

The next Moslem rulers belonged to the Umayyad dynasty (661 – 750), with their capital in Damascus. In the east, they crossed the Onux river to reach Transoxiana, where they met the Tong Chinese. Samarkand and Buhara were important trade centers. After this initial encounter, Arab-Chinese contacts continued in trade and diplomacy via the Silk Road and across the sea. Communication between Arabs and Turks also flourished, especially after the Turks were converted to Islam.

The following Arab dynasty, the

Abbasid Caliphate defeated the Chinese in 751 at the Battle of Talas. With the withdrawal of the Tongs from central Asia, the Uighurs became the new dominant power. During this historical period, all the conditions were in place for a close encounter between the long-established Chinese civilization and the flourishing Arabs, either directly or through the mediation of the Turks. Baghdad, the capital of the Abbasid Caliphate, became a center for science, culture, art, philosophy, and invention when the Abbasids reached their peak, or Golden Age, after 775 [

17]. A large number of Arab mercenaries traveled to the Chinese Tang Dynasty to provide military support in the fight against rebellions. The Abbasids also sent diplomats to forge alliances and friendships. Trade and cultural exchange between Baghdad and China flourished, and large cities became trading centers along the trade routes in Transoxiana. The Abbasids brought paper, porcelain, and decorated ceramics to Baghdad thanks to their friendly relations with China. Chinese ceramics were imported, leading to improvements in local production as well as imitations. Abbasid ceramics developed into a more important art form with a greater emphasis on decoration. This created a natural connection between Chinese and Arabic art.

The Turkish tribal groups can be traced back to names such as Kara Khanids, Ghaznavids, and later in the 11th century, the Seljuks. Trade was facilitated by the Silk Road, which was controlled by these Turkish groups. In the 11th and 12th centuries, Europeans in Constantinople and beyond benefited from trade with China by importing outstanding inventions such as gunpowder and the compass, both of which played a crucial role in European development. At the end of the 13th century, Marco Polo’s visit to what is now Beijing is one of the first direct connections between East-West without intermediaries.

5. Conclusions

China was a closed society having little contact with its neighbors. However, there are reports that at the beginning of the first millennium, there were some relations with Rouran Khaganate in the north. These intensified during the Göktürk Khaganate in the 6th century, an empire that was later absorbed by the Chinese. This led to the first military contacts and trade relations with Turkish tribal organizations. The Arab warriors, on the other hand, invaded Chinese territories in the late 7th century. The Chinese maintained contact with both the Turkish tribes and the Arab newcomers for a long time, partly because they controlled the Silk Road, which was used for trade between China and Europe.

This historical development suggests that the Chinese had already been in contact with and interacting with Turkish societies in the early centuries, which consisted of nomadic tribes and may have passed on Chinese art to the European territories in the west. This transfer of art was certainly carried out in later years by the Seljuks, especially the Seljuks of Rum [

18]. Similarly, the trade goods also found their way to the West.

The Arabs arrived in the Persian steppes during the Rashidun period, i.e., in the early Muslim era, before settling as Umayyads in their capital Damascus. It is therefore conceivable that the Arabs came into contact with Chinese art via the Turkish tribes, possibly through Turkish traders. Interestingly, the first significant architectural monument of the Umayyads known today is the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus, which was completed in 715. Arabic ornaments we have looked at here come from this mosque. No Arab works of art from earlier periods are known. We therefore conclude that the Arabs brought such works of art home with them from Transoxiana.

The inhabitants of Transoxiana were skilled traders and had their own culture, which was centered around the important cities of Samarkand and Bukhara. They were located on the Silk Road and were ruled by a multicultural, cosmopolitan trading group. Before the Arab invasion, Turkish rule in Transoxiana dates back to the 560s after the Battle of Bukhara. Most Chinese goods and cultural influences reached Europe and other parts of Asia via Transoxiana. Due to the scarcity of artworks available today, there is no evidence to substantiate our findings regarding the extent to which Chinese elements existed in these two cities in the pre-Arab era. This would have directly proven that Chinese culture was the seed of Arabic culture, as I am not aware of any such cultural achievements on the Arabian Peninsula before the Arabs came into contact with Chinese and Turkish culture.

Since we have recognized Hellenic art as the progenitor of Greco-Roman and early Christian art [

19], we must conclude that the roots of Muslim art lie in early Chinese art. Chinese art is thus the precursor to Islamic art, which in this context also includes Turkish works of art. Advances in porcelain manufacturing, silk weaving, historiography (paper), warfare (gunpowder), navigation (compass), and the discovery of new lands beyond the European continent flourished thanks to Chinese innovations. This conclusion was made possible by applying scientific and mathematical tools to symmetry in art.