1. Introduction

Traffic jams are a widespread issue in cities around the world. As people move toward cities, the number of vehicles increases, putting additional pressure on existing road infrastructure [

1]. As a result, especially during peak hours, vehicles are often stuck waiting for green lights, causing long queues at intersections. For city planners, managing balanced traffic flow across roads and intersections is a complex challenge [

2]. Conventional traffic signal systems [

3,

4] that depend on fixed timings or basic actuated rules [

5,

6] cannot meet current traffic conditions, resulting in time loss, greater fuel use, and more air pollution.

To solve these issues, researchers are developing smart traffic control systems [

7] that can operate in real time by adapting to vehicle behavior. Various machine learning (ML) algorithms [

8,

9,

10], including Support Vector Machines (SVM) [

11,

12], Random Forest [

13,

14], and K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) [

15,

16], have been employed to intelligent traffic management [

17,

18]. Deep learning techniques [

19,

20,

21,

22] have attracted considerable attention for their adaptability and ability to learn from raw data. While effective, these approaches often struggle with data randomness and complex traffic dynamics. Reinforcement learning (RL) [

23,

24,

25] has emerged as a powerful alternative, capable of learning directly from real-time data and making optimal decisions without predefined rules.

Before focusing on RL, it is important to acknowledge ML approaches that remain effective, particularly in scenarios where RL faces limitations such as high computational costs or sensor inaccuracies. For example, genetic algorithm-based methods [

26,

27] optimize signal timings by selecting the best-performing control parameters to reduce fuel use and travel delays [

28]. Similarly, 2D-CNN-based models use camera data to estimate vehicle density and classify vehicles accurately, enabling systems to respond quickly to changing traffic and prioritize emergency vehicles [

19]. Reinforcement learning (RL) uses real-time traffic states like vehicle queue length, speed, and lane idleness to determine whether to keep the green light or switch to another phase. Many RL systems use deep learning [

19,

20,

21,

22] to capture complex patterns and develop smarter control policies. Such learning-based systems offer greater flexibility and show strong potential to handle real-world congestion beyond the capabilities of traditional signals.

Several advanced RL models have been developed to make traffic systems more adaptive. IntelliLight [

29] introduces a deep RL framework [

30,

31,

32] that maximizes throughput while ensuring realistic decision-making. PressLight [

33], based on the Max-Pressure principle [

34,

35,

36], demonstrates that pressure-based rewards lead to more balanced and stable flows. FRAP [

37] addresses symmetry issues by introducing symmetry-aware learning, making it efficient in rotated or flipped traffic scenarios. Robust deep RL models [

30] improve real-world reliability by handling noisy or imperfect data. Other approaches, such as those by Guo et al. [

38] and Joo and Lim [

39], enhance adaptability, robustness to sensor noise, and phase optimization through deep Q-networks [

40,

41].

Recent work extends beyond single-intersection control to multi-agent systems. The Multi-agent Coordinated Policy Optimization (MACOPO) algorithm [

42] coordinates signals across intersections to reduce waiting times and emissions in large-scale networks. Similarly, the Multiagent Graph-based Soft Actor-Critic (MAGSAC) [

43] leverages a graph-based SAC framework [

44] to manage signals across complex road networks. These methods have shown promising results in simulations, often reducing travel times, waiting times, and queue lengths by significant margins, in some cases up to 72%. Beyond ML and RL, hybrid systems combine rule-based logic with adaptive, data-driven components. For example, ATLCS adjusts signals based on real-time vehicle counts and synchronizes junctions for smoother peak-hour flow [

45], while priority-based controls reduce wait times and grant emergency vehicles special access [

46].

In this study, we are providing a comprehensive overview of recent developments in intelligent traffic signal management, specifically looking at methods that rely on reinforcement learning. We also highlight other AI-driven strategies that complement or extend RL capabilities. By examining these innovations, our goal is to strengthen the expanding research on developing smarter, safer, and more efficient urban transportation systems.

2. Review

This study aims to provide a detailed overview of the most recent advancements in intelligent traffic signal control with a focus on decreasing both average travel time and fuel usage. The focus was specifically placed on models that offer real-time adaptability, scalability to various intersection types, and robust performance in dynamic urban traffic conditions. While this paper emphasizes RL-based approaches, it also includes a secondary analysis of other Hybrid and ML models. To capture a comprehensive scenario, this review employs a two-step approach: first, we focus on research papers based on ML and hybrid methods, and then review RL-based methods for comparison.

After collecting and filtering the papers, we organized them into two broad categories. The first category includes ML and hybrid approaches, such as adaptive systems [

45], genetic algorithm-based models [

28], priority-based control [

46] for emergency vehicles, and techniques for traffic density estimation [

19]. The second category includes

reinforcement learning-based models, such as IntelliLight [

29], PressLight [

33], FRAP [

37], AttendLight [

47], robust RL frameworks [

30], MACOPO [

42], and MAGSAC [

43], which use deep learning or advanced Q-learning to dynamically optimize traffic signal timing. Each paper was reviewed in detail to extract the core idea, methodology, implementation details, and experimental outcomes.

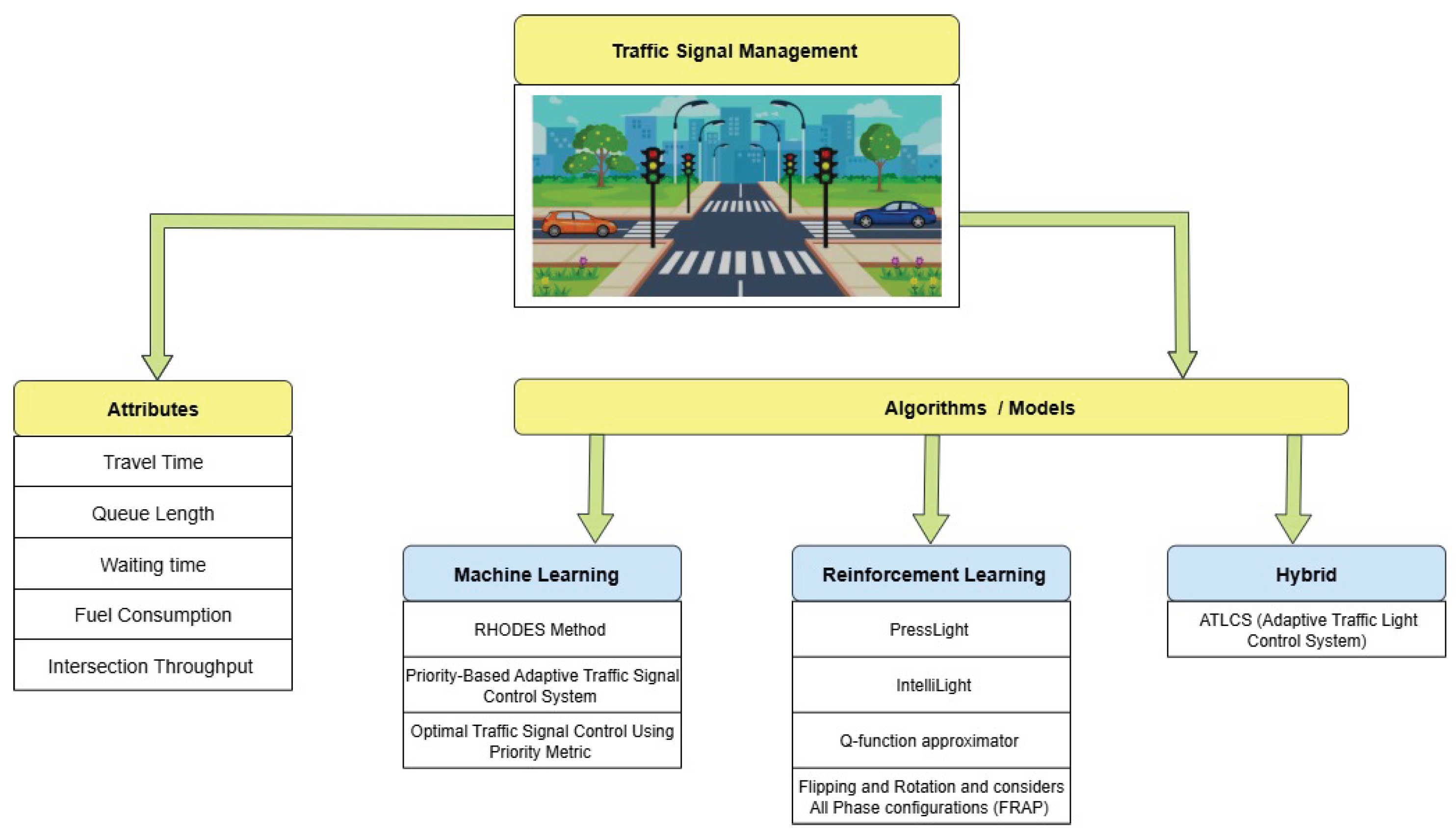

The models were compared by evaluating their performance across key attributes like travel time, queue length, waiting time, fuel consumption, and intersection throughput. An overview of traffic signal management in terms of evaluation attributes and representative model categories is shown in

Figure 1. This structured strategy provides a clear view of how reinforcement learning stands out among modern techniques while acknowledging the contribution of other methods.

2.1. An Overview of Key Terms and Concepts in Machine Learning (ML), Reinforcement Learning (RL), and Hybrid Learning, with a Focus on Traffic Systems

Machine Learning (ML):

ML refers to methods based on data training, extracting information, and making decisions related to traffic management. These methodologies rely on traditional supervised or unsupervised machine learning techniques [

8], including Random Forest [

14], SVM [

11], and Gradient Boosting [

48]. ML requires labeled or structured datasets in order to establish the mapping between input features and desired outcomes. In addition to these ML algorithms, deep learning approaches like Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) [

19,

49,

50] are applied in traffic management for vision-based tasks such as vehicle detection and traffic density estimation. For example, a CNN can estimate vehicle density from camera images and send this information to a control unit that decides signal timing [

19] [

50]. Typically, ML methods are widely used in traffic control systems for tasks such as predicting congestion. In smart traffic systems, ML is often used for the preprocessing and decision support layer. For instance, past traffic data can be used to train algorithms such as SVM and Random Forest to predict congestion levels or suggest the best signal plans during peak hours [

51]. ML approaches need good-quality data for prediction or classification. Conventionally, ML’s use in traffic management has shown its ability to support the development of smart cities by providing data for control strategies and improving awareness of situations, but its effectiveness depends on the quality of the input data.

Reinforcement Learning (RL):

Reinforcement learning [

23,

24,

25] is a branch of ML in which an intelligent agent learns to make a sequence of decisions by engaging in real-time with its environment and receiving feedback in the form of rewards. The foundation of Reinforcement Learning lies in the Markov Decision Process (MDP) [

52,

53]. MDP is a mathematical model for decision-making where outcomes are influenced by both the decision-maker’s actions and random choices [

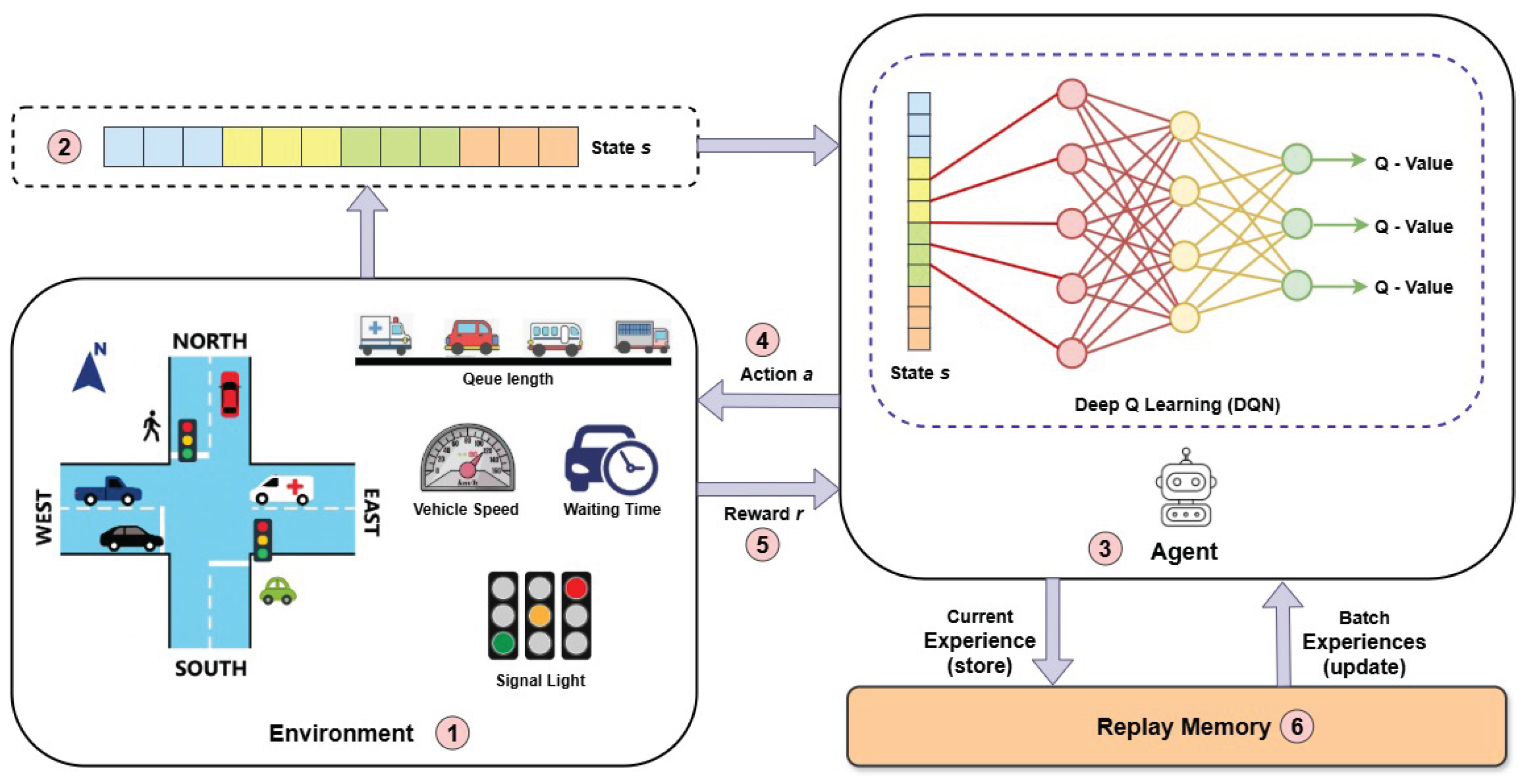

54]. The key elements of RL within the context of a traffic management system include (see

Figure 2):

Environment: The network where agents operate, like traffic intersections, including the physical infrastructure of roads and vehicles. Labeled as 1 in

Figure 2

State : Current conditions such as traffic queue lengths, waiting times, lane occupancy, vehicle speed, and so on. Shown within the dotted box labeled “State” in

Figure 2 and marked as 2.

Agent: The decision-maker, such as a traffic signal controller. Represented by labeled 3 in

Figure 2

Action : Decision taken by the agent. For example, changing or maintaining the current traffic light phase. As shown by label 4, the directional arrows from the agent to the environment in

Figure 2.

Reward : A numerical measure that reflects the effectiveness of an action, such as lowering vehicle waiting time or shortening queue length. Marked as 6

Figure 2, the feedback arrow returns from the environment to the agent.

Replay Memory: Marked as 6 in

Figure 2, A replay memory stores the agent’s past experiences so it can learn from them and improve its decision-making.

In traffic signal control, we can model the problem as a Markov Decision Process (MDP), which is described by a tuple

. This tuple consists of the state space

S, action space

A, state transition probabilities

P, reward function

R, and a discount factor

. The primary goal is to determine a policy

that optimizes the expected cumulative reward, as expressed in Equation

1

Training Process:

RL models achieve effectiveness by balancing exploration and exploitation [

55], which is important for avoiding convergence to suboptimal strategies. There are different types of learning approaches used to train the RL model, including the following:

Q-Learning, an algorithm [

56] that estimates Q-values, representing the predicted rewards of state–action pairs without relying on a model of the environment. As shown in equation

2, the Q-value for a given state-action pair (

s,

a) is updated using the immediate reward (

r), the next state (

), and the possible action (

) in that next state. The update rule incorporates two key parameters: the learning rate (

) and the discount factor (

).

The

Deep Q-Network (DQN) [

57] is a learning method that extends Q-learning by merging deep neural networks to approximate Q values in high-dimensional state spaces. This approach, which uses the approximation shown in Equation

3, is well-suited for processing complex inputs like images or multi-lane traffic information.

Policy Gradient [

58,

59] is an approach that directly improves the policy rather than estimating value functions. It employs gradient ascent to maximize the objective function,

, which is the expected return, as mentioned in Equation

4. This approach directly optimizes the policy

, which is the strategy an agent uses to select actions based on states.

Here, are policy parameters and is the return.

Epsilon-Greedy Strategy [

60] is a reinforcement learning technique designed to balance exploration and exploitation. This allows the agent to continue learning and discovering improved strategies rather than being stuck with a suboptimal one. For example, in traffic signal control, if

, the agent might 10% of the time pick a random signal phase even if it seems less optimal, such as giving green to a less busy lane.

Hybrid Approaches:

Hybrid approaches merge traditional rule-based systems with data-driven techniques like machine learning (ML) [

8,

9] or reinforcement learning (RL) [

24,

25] to enable adaptable decision-making. Rule-based systems follow predetermined instructions; on the other hand, data-driven learning methods use real-time traffic to make decisions, which increases flexibility and the ability to learn. Hybrid systems work well in real traffic without needing massive training or simulations, as the systems combine simple rule-based logic with smarter optimization algorithms. Many systems become more effective by using hybrid approaches that combine ML and RL techniques. For example, in a traffic environment, ML models predict the traffic density from an intersection, and based on this information, RL models decide optimal signal timings to maximize the throughput. ATLCS (Adaptive Traffic Light Control System) [

45] is a hybrid model discussed in this study that combines rule-based coordination across multiple intersections with adaptive timing adjustments based on real-time traffic volumes. Hybrid methods are useful in deployments where full smart traffic control is not yet feasible; they help improve traffic efficiency without the need for large-scale training or complex models.

3. Research Papers

3.1. Machine Learning (ML) and Hybrid-Based Approaches

3.1.1. RHODES Method by Mirchandani et al. (2001)

To enhance traffic management, Mirchandani and Head [

61] developed the Real-time Hierarchical Optimized Distributed Effective System (RHODES), which uses real-time data from traffic detectors to optimize traffic flow adaptively. The RHODES [

62] system uses real-time traffic data from surface street sensors to collect traffic flow measurements. It then predicts future traffic patterns at various hierarchical levels, which helps in anticipating traffic conditions. Rather than depend on an ML model, the RHODES approach uses a custom traffic flow model to predict future traffic. The system used these predictions to create the best signal control settings, which it then used to adjust signal timings in real-time to reduce delays and make traffic flow more efficiently. CORSIM (Corridor Simulation) [

63] is a traffic simulation tool developed and maintained by the Federal Highway Administration, designed to track vehicle positions and movements across the network at one-second intervals. The RHODES system has proven effective in managing traffic by reducing delays across different CORSIM simulation models. The simulation outcomes show enhanced performance in traffic signal control relative to conventional approaches such as Fixed-Time Signal Control [

3], Actuated Signal Control [

5], and Pre-timed Signal Control [

64].

3.1.2. Smart Traffic Light Control System Using PIC and IR by Ghazal et al. (2016)

The paper by Ghazal et al. [

65] presents a study to address key issues such as traffic congestion, interference between adjacent intersections, and the lack of emergency vehicle prioritization. The authors developed a smart traffic signal control system that utilizes a Programmable Intelligent Controller (PIC) microcontroller [

66,

67] and Infrared (IR) sensors [

68,

69] to dynamically adjust intersection signal timings according to real-time vehicle density. The system is also able to prioritize emergency vehicles through a wireless XBee-based portable controller [

70,

71]. In this approach, the IR sensors continuously monitor vehicle counts in different lanes. Using these inputs, the microcontroller assesses traffic density and switches the signal light between three predefined traffic modes, such as normal (30-second green light), traffic jam (50-second green light), and soft traffic (15-second green light) to enhance traffic efficiency. This system also includes a wireless XBee-based portable controller that enables emergency vehicles to override regular traffic signals, which ensures a priority path through intersections without delays. The model was successfully implemented and tested in different traffic conditions. The suggested approach offers a cost-effective and easy-to-implement solution that reduces peak-hour congestion, minimizes the unnecessary waiting times at intersections, and allows emergency vehicles to override regular traffic signals. The current system, despite showing promise for dynamic traffic control, is limited because it can only manage a single intersection with just three predetermined traffic modes. This limitation prevents it from effectively handling traffic flow in unpredictable urban networks or responding in real time. Additionally, the emergency vehicle priority mechanism depends on manual activation via a portable controller, which is less efficient than automated detection methods and could delay response in fast-moving scenarios.

3.1.3. Adaptive Traffic Light Control System (ATLCS) by Aleko and Djahel. (2020)

Traffic congestion on urban roads remains a recurring issue in modern cities. Traditional traffic light systems often fail to address this problem effectively under fluctuating traffic conditions. To address the issue of urban road traffic congestion, especially during peak hours in city centers, Aleko and Djahel [

45] introduce an Adaptive Traffic Light Control System (ATLCS) that synchronizes traffic signals across consecutive intersections. The ATLCS aims to improve traffic flow by synchronizing traffic lights at consecutive intersections. The timing of the signals is dynamically adjusted according to the volume of traffic waiting at each intersection. The model aims to cut down delays and reduce the stop-and-go effect, especially during the afternoon peak hours when traffic is most congested. Using SUMO (Simulation of Urban Mobility) [

72], an open-source microscopic traffic simulation tool, it was shown that ATLCS decreased the average travel time for vehicles moving in a synchronized direction by as much as 39% when compared to traditional fixed-time systems. Overall traffic flow in the simulated road network improved by 17% with the synchronized traffic signal system. This demonstrates that the gains from synchronization weren’t limited to just a few major roads. The evaluation also noted fewer "stop and go" occurrences, leading to smoother travel during peak hours.

3.1.4. Priority-Based Adaptive Traffic Signal Control System by Mondal and Rehena. (2022)

Urban areas are facing major challenges in their transportation infrastructure and city management due to the growing number of vehicles. Earlier studies [

73,

74,

75] tried using smart methods like machine learning and fuzzy logic [

76,

77], but they either lacked real-time adaptability or consistently prioritized lanes with high vehicle density, resulting in vehicles in low-density lanes having to wait for extended periods. In response to these challenges, Mondal et al. [

46] introduced a priority-based adaptive traffic signal control system that adjusts signal timings in real time according to vehicle density and waiting time, while also giving priority to emergency vehicles at intersections. The system collects real-time vehicle density and waiting time data using in-road sensors, such as inductive loops, pneumatic tubes, or RFID [

78,

79], which are linked to a roadside communication network. A processing unit then analyzes this information and determines which lane should receive the green light next. The system operates in two modes: Regular mode (RM), which controls normal traffic flow, and emergency mode (EM), which intelligently manages emergency vehicle approaches at intersections. The proposed system was evaluated through computer simulations on a four-legged intersection model under both equal and unequal traffic scenarios to assess its performance. The authors considered two key attributes. Firstly, the traffic flow percentage of each lane, and secondly, the time interval between successive green signals for the same lane. The performance showed that the adaptive system enhanced traffic flow considerably, allowing 31.05% more vehicles to pass through intersections compared to the fixed-time approach. The proposed system, applicable to both real-time and emergency conditions, is well-suited as a prototype for smart city traffic management aimed at maintaining steady intersection flow.

3.1.5. Optimal Traffic Signal Control Using Priority Metric Method by Kim et al. (2023)

Traditional traffic signal systems are highly inefficient, causing increased fuel consumption and traffic congestion. The research by Kim et al. [

28] aims to reduce fuel consumption across the entire network and enhance traffic flow by modifying traffic signals in real-time based on current traffic conditions. Conventional approaches, such as fixed-time signal schedules [

80] and basic coordinated actuated systems [

81] that rely on proximity sensors, cannot adjust to real-time traffic, which results in poor traffic flow, frequent vehicle stops, longer travel times, and higher fuel consumption across traffic networks. To address these limitations, Kim et al. [

28] present a novel traffic signal control approach designed to boost the energy efficiency of vehicles throughout the network. The approach relies on real-time traffic data collected through advanced sensing technologies, including cameras, radars [

82], and LiDARs [

83]. It calculates a priority metric using a weighted combination of various factors, including vehicle count, speed, waiting time, and road priority. A Genetic Algorithm (GA) [

84], a common method for global optimization, is employed to determine the optimal weights for these factors. Inspired by natural selection, GA refines solutions iteratively step by step through selection, crossover, and mutation [

85]. The performance of this method is tested through simulations using SUMO [

86], where the traffic model was built and calculated using real-world traffic data from a corridor along US-82 in Tuscaloosa, Alabama. The results show that this approach significantly achieves up to a 14.8% reduction in fuel consumption over traditional fixed-time control and a 3.7% reduction compared to coordinated actuated control.

3.1.6. Vehicle Density Estimation Traffic Light Control System Using 2D-CNN by Mathiane et al. (2023)

While previous research mannerhas addressed several issues in Traffic management, it still struggles to efficiently adjust to real-time traffic conditions. Considering this issue, Mathiane et al. [

19] introduced a novel vehicle density estimation traffic light control system that utilized a two-dimensional convolutional neural network (2D-CNN) [

87]. By employing a 2D-CNN [

88] for vehicle classification and prioritizing emergency vehicles, the system ensures that emergency vehicles like ambulances can navigate intersections quickly during critical situations. The results of the study indicated that the suggested adaptive traffic light control system considerably improved traffic management. Simulations were conducted using both Pygame [

89], a lightweight Python library often used to visualize vehicle movements and traffic signals in 2D, and SUMO [

86], a high-fidelity traffic simulation platform. The result showed that the adaptive system achieved a vehicle throughput of 90% compared to traditional fixed-timing systems [

3,

4], allowing significantly more vehicles to pass through intersections. Furthermore, the 2D-CNN model had a remarkable 96% accuracy rate for classifying vehicles. This capability ensures effective prioritization of emergency vehicles and contributes to quicker response times at critical intersections. The effectiveness of the proposed system lies in its ability to tackle urban traffic issues and underline its potential in advancing intelligent transportation systems.

3.2. Reinforcement Learning (RL) Based Approaches

3.2.1. IntelliLight a Reinforcement Learning Approach by Wei et al. (2018)

Recent research has shown that applying reinforcement learning (RL) [

24,

25] and deep reinforcement learning (DRL) [

90,

91] to dynamic traffic signal control produced promising outcomes. However, most of these techniques are limited to simulated environments with simplified assumptions and overlook how learned policies actually behave in real-world settings. These approaches rarely consider real-world conditions where traffic patterns are highly unpredictable and complex. To overcome the shortcomings of traditional methods and earlier RL-based traffic signal systems [

92,

93], the authors introduced IntelliLight [

29], a deep reinforcement learning model developed to manage traffic signals more intelligently. The authors found that simply maximizing numerical rewards in traffic control does not always lead to the most efficient or realistic outcomes. So, instead of only focusing on rewards, the authors also emphasized understanding the learned policies to ensure they align with real-world traffic behavior. The problem was simplified to a two-phase traffic light at a single intersection, where an intelligent agent monitors factors like vehicle positions, queue lengths, and waiting times, and then decides whether to maintain or change the signal. An agent is trained in two phases, guided by a reward function that evaluates multiple traffic flow metrics, including queue lengths, average delays, waiting times, vehicle throughput, and total travel time. Initially, the agent undergoes an offline training phase using a fixed signal schedule for data collection. Subsequently, it is followed by an online exploration phase where it actively manages traffic lights and refines its learning via an epsilon-greedy exploration strategy [

60]. To enhance decision-making, they introduce the Phase Gate, allowing the model to respond differently depending on the current traffic light phase, and the Memory Palace, which stores phase-action experiences separately to avoid data imbalance during training. The authors’ proposed method was evaluated against traditional approaches, including Fixed-Time Control [

94], Self-Organizing Traffic Lights (SOTL) [

95], and a basic DRL model [

91]. Using the SUMO [

86] simulator, they found that IntelliLight consistently outperformed all baselines across different synthetic traffic scenarios. In synthetic experiments, it reduced queue length by 81.8% to 99.9% compared to traditional approaches across different traffic configurations. The authors also tested real-world traffic data from over 1,700 surveillance cameras in Jinan, China. IntelliLight once again delivered strong results, reducing travel time by 40.26% and queue length by 47.6% when measured against conventional methods. It also adapted smartly to changing traffic patterns like peak hours and weekends without needing manual adjustments, showing its practical potential for real-world use.

3.2.2. Q-Function Approximator by Guo et al. (2019)

Even though RL [

92,

93] offers promising alternatives, many current RL solutions are limited and cannot smartly handle real-world traffic complexity. To overcome these gaps, Guo et al. [

38] propose a novel Q-function approximator, which is based on a custom neural network, to create a smarter and more flexible traffic signal control system for complex urban intersections. To handle the high-dimensional state space, a Q-function approximator (known as Q-network) [

96] was employed. The system utilizes real-time traffic data, specifically vehicle speed and position, to determine the most effective signal phases for minimizing congestion, considering both multiple lanes and eight different signal phases. Some advanced RL techniques, such as experience replay and a target network, are integrated to stabilize the learning process, allowing the model to learn more consistently from previous experiences. The authors assessed the effectiveness of their RL-based traffic signal control model by performing multiple simulation experiments in the SUMO [

86] traffic simulator. They configured a realistic intersection and trained the Q-network across 200 episodes by fine-tuning hyperparameters like learning rate, replay memory size, and discount factor. The model’s adaptability was tested under four traffic scenarios, including major and minor roads, through and left-turn lanes, tidal flow, and fluctuating demand. For benchmarking, the RL model was compared against three conventional methods: fixed-time control [

94], gap-based control [

97], and time loss-based control [

98]. Results presented in the study showed that the proposed RL model consistently outperformed benchmark methods, achieving 27% to 73% reductions in average queue length and 42% to 79% reductions in average wait time across different patterns. The model also showed strong performance under dynamic traffic conditions, confirming its robustness and flexibility to real-world variations.

3.2.3. Flipping and Rotation and Considers All Phase Configurations (FRAP) by Zheng et al. (2019)

Zheng et al. [

37] noted that although advanced RL approaches such as IntelliLight [

29] and Deep Q-Network (DQN) [

57] based frameworks have shown promising solutions in addressing urban traffic congestion, they struggle with long convergence times and the inability to handle symmetrical traffic scenarios such as flipped or rotated traffic flows. To overcome these challenges, the authors introduce an RL-based model called FRAP (Flipping and Rotation and considers All Phase configurations), that integrates Ape-X Deep Q-Learning (DQN) [

57] to estimate Q-values for each action using state features. The FRAP model uses a phase competition mechanism to prioritize high-demand movements, ensure symmetry invariance to handle flipped and rotated flows without retraining. The Ape-X DQN framework enhances learning efficiency by sharing knowledge across symmetric states. The study uses the CityFlow simulation [

99] platform to evaluate the FRAP model with datasets from Jinan, Hangzhou, and Atlanta [

100], measuring performance through average vehicle travel time at intersections. The model demonstrates remarkable improvements, reducing travel time by as much as 47.69% when compared with advanced approaches like IntelliLight and DRL [

91]. It shows robustness to flipped and rotated traffic flows, removing the need for retraining, and proves versatile across different intersection configurations.

3.2.4. PressLight by Wei et al. (2019)

While several RL methods, such as [

92,

93], can bring better performance, Wei et al. [

33] point out two main issues with how these methods are currently used. Firstly, they rely on complex and unstructured input data, like image-based inputs. Second, the reward functions don’t directly reflect the true goal, which means reducing travel time, but instead use indirect measures like queue lengths or delays. These limitations lead to longer training times and unstable performance. To address these limitations, Wei et al. [

33] introduced PressLight, an RL-based model built upon the Max Pressure principle [

35], which has been theoretically proven to optimize network throughput. The approach assigns an independent RL agent to each intersection in the arterial network, where the agent monitors essential traffic features, including the current signal phase, vehicle counts on outgoing lanes, and a segmented view of incoming lane traffic close to the intersection. At every step, the agent decides which signal phase to activate and gets a reward based on how balanced the traffic is. Specifically, its main goal is to minimize pressure, measured by the imbalance of traffic between incoming and outgoing roads. The authors use a Deep Q-Network [

57] to enable the agent to learn from past experiences and enhance its decision-making over time. It should be noted that PressLight is based on real traffic science rather than a guessing game. The authors demonstrated that their state design aligns with traffic flow equations used in transportation literature and that the pressure-based reward leads to system stability, which in turn leads to a reduction in people’s travel time. The authors performed all experiments on the CityFlow [

99] simulator, where PressLight was benchmarked against several baseline methods using synthetic and real-world traffic data across different settings and sizes of the road network. Using average travel time as the main evaluation metric, PressLight consistently delivered superior results with shorter travel times than all baseline methods. For instance, under heavy flat traffic in a six-intersection arterial, PressLight reduced the average travel time to 160 seconds, which is a 31.2% improvement over Light-Intellight (LIT) [

101] (233 seconds) and a 38.8% improvement over MaxPressure [

35] (262 seconds). On real roads, PressLight achieved significantly lower average travel times, for example, 55s on Qingdao Road (Jinan) and 92s on Beaver Avenue (State College), compared to MaxPressure’s 567s and 223s, demonstrating its strength in handling dynamic traffic. Overall, the findings indicate that PressLight performs effectively in real traffic, offering easy scalability and a clear improvement in traffic flow.

3.2.5. AttendLight Algorithm by Oroojlooy et al. (2020)

As mentioned above, RL has shown superior performance in managing traffic signals in modern cities, outperforming traditional fixed timing systems and adaptive methods like SOTL [

95] and Max-pressure [

35]. Despite their improved performance, RL models still have limitations, as they typically require retraining for every new intersection layout, which is computationally costly, time-consuming, and inefficient. To overcome this limitation, Oroojlooy et al. [

47] introduce a universal RL-based model, AttendLight, that is capable of managing intersection signals with different numbers of roads, lanes, and signal phases, without the need for retraining. The authors defined the traffic signal control problem by using real-time traffic characteristics of each lane as the state, selecting the next active signal phase as the action, and using the negative intersection pressure as the reward, which indirectly contributes to reducing travel time. AttendLight model works on two attention mechanisms, the first is state-attention used to extract meaningful features from varying lane data, and the second is action-attention used to select the most suitable phase based on these features and past decisions. The authors also make use of the LSTM [

102] cell, which ensures the model learns from the sequence of previous actions, improving its decision-making over time. The AttendLight model is trained using a policy-gradient method called REINFORCE [

103], under both single and multi-environment settings, making it suitable for both individual intersections and large-scale deployments without retraining. The authors evaluated AttendLight through extensive experiments on 112 different intersection scenarios, including both real-world and synthetic data. In single-environment tests, where the model is trained and used on the same intersection. AttendLight showed significant results, reducing the average travel time by up to 46% compared to FixedTime, 39% compared to MaxPressure, 34% compared to SOTL, 16% compared to DQTSC-M [

104], and 9% compared to FRAP [

37]. In multi-environment settings, where a single model is trained across many intersections and then tested on unseen ones, the model still performed strongly, with only 13% performance loss, which was reduced to 3–5% after a small amount of fine-tuning. These results highlight that AttendLight is not only accurate and efficient, but also adaptable to new intersections without requiring complete retraining.

3.2.6. Traffic Signal Control Using Q-Learning by Joo et al. (2020)

With the growth of smart cities and IoT technologies, traffic control has the potential to become smarter and more efficient than ever before. Among various AI methods, reinforcement learning, particularly Q-learning [

56], holds promising potential because it can learn and adapt in real-time. Building on these advancements, Joo et al. [

105] investigated the use of Q-learning [

56] in a traffic signal control system that both increases intersection throughput and maintains balanced traffic flow in all directions. The study also reviews previous efforts using fuzzy logic [

76,

77], standard Q-learning [

56], and deep RL [

90], highlighting their limitations and setting the stage for the proposed solution. Instead of changing the whole system for every new intersection layout, the authors fixed the action set based on road directions, which made the model more flexible and easier to apply to any n-way intersection. The system learns from experience by using current traffic situations referred to as states, determining which road gets the green light, known as actions, and evaluating performance based on how smoothly traffic is flowing, which is measured through rewards. The authors designed the reward using two key parameters: the first one presents the balance of traffic distribution, which is measured by queue length deviation, and the second one presents the number of vehicles that pass the intersection, representing throughput. This mechanism allows the system to clear more vehicles at the intersection without keeping the green signal on one road for too long. The authors ran simulation tests using the SUMO simulator [

86] to test their model performance on a 4-way intersection and compared it with two other Q-learning methods, one is the extension traffic signal E-TS [

106] that only adjusts green light timing, and another one is cluster-traffic signal C-TS [

107] that controls traffic in groups or clusters. The authors measured performance using three core indicators: queue length, the standard deviation of queue lengths, and waiting time. The results indicate that the proposed model achieved a 25% reduction in average queue length relative to E-TS [

106] and a 63% reduction compared to C-TS [

107]. Traffic distribution was more balanced, showing 50% lower deviation compared to E-TS and 75% lower than C-TS. Vehicles experienced reduced waiting times with the model (app.) 15% less than with E-TS and 40% less than with C-TS. The model demonstrated effectiveness across various intersection types, including three-way, five-way, and six-way intersections.

3.2.7. Robust Deep Reinforcement Learning by Tan et al. (2020)

Previous adaptive traffic signal control approaches based on deep reinforcement learning (DRL) [

90] face several challenges in managing traffic congestion at intersections. Subsequent studies [

108,

109,

110] indicate that DRL has shown promising improvements in dynamic traffic control systems. Most models operate under the assumption that sensor-collected traffic data is accurate and free of noise, even though in real-world conditions it can be affected by weather, technical faults, or blockages from large vehicles such as trucks. Such edge cases mislead RL agents and lower their effectiveness in real-world deployment. Considering this practical limitation, Tan et al [

30] propose a robust DRL framework that can still learn effective traffic signal policies even when the input state data, such as queue length, is noisy or imperfect. The authors integrate Double Deep Q-Networks (Double DQN) [

111], which maintain two separate Q-networks for reducing overestimation of action values by a more stable variant of DRL. The key innovation lies in adding synthetic Gaussian [

112] noise into the queue length data during training, which helps the agent become less dependent on perfectly accurate inputs and more resilient to real-world sensor inaccuracies. The authors propose five different state space configurations using combinations of traffic signal phases, vehicle speeds, actuation counts, and residual queues. The action space allows the agent to maintain or change signal phases, with realistic timing constraints like yellow and red light durations. The authors assessed the performance of their robust RL method using the SUMO simulator [

86], modeling a four-way intersection with protected left turns and varying traffic flows. They tested two types of models: a Nominal agent, which was trained with clean, perfect data, and a Robust agent trained with slightly wrong or noisy data. It was observed that the Robust agent achieved outstanding performance compared to the Nominal agent under noisy test conditions. For example, the nominal agent’s performance deteriorated to -13.43 at noise level 10, whereas the Robust agent remained steady at -3.13, indicating over 76% better robustness. The authors even tested a realistic situation with trucks causing sensor problems, and again, the Robust agent did much better. For example, in one test with 20% truck traffic, the Robust agent performed about 60% better in a hybrid sensor setup and more than 78% better in another case using induction sensors. These results show that their model works well even with noisy, real-world data.

3.2.8. Optimizing Traffic Signals Using Deep Q-Networks by Joo and Lim. (2021)

While RL has solved several traffic management issues, many studies still tested only with fixed signal cycles, which makes them less practical for real-world use. Joo and Lim [

39] observed that nearly 30% of green signal time in fixed signal systems was wasted because more time was allocated than required. Considering these limitations, the authors introduce smart traffic management using Deep Q-Network (DQN) [

57] based RL as a potential solution to optimize signal timing dynamically. The main goal is to maximize intersection capacity while minimizing waiting times and green signal wastage. The authors used DQN to adjust the duration of green signals in a fixed phase order, while Wei et al. [

33] used it in their PressLight system to select which phase to activate, aiming to improve network throughput by using a pressure-based reward. The study by Joo and Lim framed traffic signal control as a Markov Decision Process (MDP) [

52] [

53], where optimal actions are learned from states and rewards. The state was represented by six main parameters, including traffic load, queue length, waiting time deviation, and surrounding traffic conditions. The reward function was designed to optimize two objectives: maximizing intersection capacity and minimizing the standard deviation of waiting time to ensure fair signal allocation across all lanes. The effectiveness of the proposed model is assessed in SUMO [

86] on a nine-intersection network, where real-time traffic flow is generated using a Poisson distribution [

113]. The model’s performance was compared with cooperative traffic signal control with traffic flow prediction (TFP-CTSC) [

114] and cooperative deep Q-network with Q-value transfer (QT-CDQN) [

115], considering evaluation metrics such as intersection capacity, queue length, waiting time, standard deviation of waiting time, and waste of green signal. The findings indicate that the proposed system reduced queue length by approximately 50% compared to TFP-CTSC and by 45% compared to QT-CDQN. It also reduced the standard deviation of waiting time by 35% compared to TFP-CTSC and 60% compared to QT-CDQN. In terms of throughput, the system increased intersection capacity by 40% over TFP-CTSC and 30% over QT-CDQN. These findings confirm that the proposed approach significantly improves traffic flow efficiency, minimizes congestion, and increases overall intersection performance compared to fixed-time traffic control methods.

3.2.9. Multi-Agent Coordinated Policy Optimization (MACOPO) by Ren et al. (2024)

As vehicle density grows, Ren et al. [

42] observe that conventional rule-based methods and current reinforcement learning (RL) techniques are insufficient for managing real-time traffic and high emissions in complex urban areas with multiple intersections. To overcome this limitation, Ren et al. introduced the Multi-agent Coordinated Policy Optimization (MACOPO) [

42], based on a two-layer DRL-based approach [

90]. To achieve optimized network-wide performance, the model integrates the two-layer coordination mechanism, local cooperation, and global coordination. This approach treated each individual intersection as an autonomous agent responsible for managing its local traffic signals. At the local level, each agent makes decisions based on the rewards of its own and its neighboring intersections, using a Local Cooperation Factor (LCF). At the global level, MACOPO acts as a manager for the entire network, adjusting the LCF values to maximize network-wide rewards through gradient-based optimization to ensure that all the local cooperation works toward improving the entire system rather than competing for individual gains. Both simulated and real-world datasets, such as Cologne [

116], were used to assess the performance of the MACOPO algorithm. The study indicated that MACOPO achieved superior performance compared to various baseline and state-of-the-art methods. For instance, when tested on real-world datasets, the model achieved an average of 35% shorter waiting times (comparable to the 57–100% reductions observed by Pan [

117]) reduction reported by Swapno et al. 2024), 25–30% lower vehicle emissions, and around 12–15% higher throughput. Overall, the study shows that MACOPO is an advanced solution for smart traffic control that can reduce delays and emissions while improving traffic flow across multiple intersections.

3.2.10. Multiagent Graph-Based Soft Actor-Critic (MAGSAC) by Shang, et al. (2025)

Shang et al. [

43] noted that, influenced by a variety of factors such as driver behavior to environmental conditions, many recent RL approaches still rely on Q-learning or DQN [

57] variants that generate deterministic strategies, exacerbating the issue of limitations to handle the uncertainty of real-world traffic. They also noted that even with multi-agent reinforcement learning (MARL) frameworks, existing works overlook the dynamic relationships between traffic signals at different intersections, which can lead to ineffective cooperation or redundant information exchange. To address these limitations, the authors formulate traffic signal control as a partially observable Markov decision process (POMDP) [

118], with each intersection serving as an agent that has its own observation, action, and reward space. Based on this foundation, the authors introduced a new approach called Multiagent Graph-based Soft Actor-Critic (MAGSAC) [

43], combining graph neural networks (GNN) [

119] with a soft actor-critic (SAC) [

44] algorithm. In this architecture, intersections are represented as nodes in a graph to capture network structure. A graph learning module with LSTM [

102] handles temporal traffic patterns and multihead attention mechanisms to filter out irrelevant information and highlight important interactions between intersections. The SAC algorithm used in this work with entropy regularization helps the traffic lights to make better decisions by dynamically choosing the action, and the dual critics system is used to stabilize the learning process. The performance of the MAGSAC was tested on the CityFlow [

99] simulator on both synthetic grid networks and real-world urban datasets from Jinan, Hangzhou, and New York. The results clearly showed that MAGSAC performed well, especially in complex, large-scale networks. On real-world datasets, MAGSAC reduced ATT by 16.6%, 54.5%, and 55.8%, respectively, compared with PressLight [

33]. In this approach, even increasing the number of intersections, MAGSAC maintained shorter training times than other RL methods, demonstrating that its graph-based design scales well to large networks.

4. Comparison and Discussion

4.1. Machine Learning (ML) and Hybrid-Based Approaches

Even though RL models have gained enormous attention in recent years in intelligent traffic management, ML and hybrid-based systems still hold an important role in this field. These systems are more efficient because they are easier to set up, perform consistently under typical conditions without advanced tuning, and require less computing power. Using simple rules, sensor data, and basic optimization, these approaches usually manage traffic signals dynamically to improve traffic flow.

Among these models discussed in

Section 3.1, ATLCS [

45] stands out for its effective use of real-time vehicle counts to synchronize signals across adjacent intersections. It helps reduce traffic jams, minimize stop-and-go movement, and improve overall flow. In these approaches, vehicles move more smoothly and waste less time at lights, especially during busy rush hours. The simulated result for these approaches showed up to 39% travel time reduction in prioritized directions and improved overall traffic flow across the entire network by 17%. The RHODES [

61] system was one of the earliest systems, introducing a real-time adaptive architecture that influenced many subsequent designs. The paper Ghazal et al. [

65] combined IR sensors and PIC microcontrollers to reduce congestion and prioritize emergency vehicles, offering a cost-effective hardware-based approach.

Overall, Hybrid and ML-based traffic control systems are less complex than deep RL models, but they are still very practical and useful, especially in regions where cities don’t have powerful computing infrastructure or cannot invest in expensive AI systems. The comparative evaluation of these Hybrid and ML models is summarized in

Table 1. This table summarizes the reductions in travel time, queue length, waiting time, and fuel consumption, as well as improvements in intersection throughput, for each method, based on direct comparisons among models evaluated on the same simulation platform or dataset.

Within the SUMO environment, using magnetometer data, ATLCS [

45] achieved a 39% reduction in travel time and a 17% increase in throughput on Manchester arterial roads. In contrast, Mathiane et al. [

19] achieved a remarkable 90% throughput improvement on vision-based data, which is much better than ATLCS. On the other hand, Kim et al. [

28] conducted experiments using US-82 traffic data in Alabama and demonstrated a 14.1–14.8% reduction in fuel consumption. These results show that in SUMO-based experiments, ATLCS is most effective for reducing travel time, Mathiane’s CNN-based approach is strongest for throughput, and Kim’s method highlights measurable improvements in fuel efficiency. Additionally, unlike advanced ML methods such as the 2D-CNN model by Mathiane et al., ATLCS does not need heavy image-processing hardware or complex training.

Some models were tested in different simulation environments, which makes direct metric-to-metric comparison difficult. For instance, RHODES [

61], implemented in CORSIM, achieved a 30–50% reduction in waiting time, demonstrating strong adaptability in its context. Mondal and Rehena [

46], using a Python-based simulator, increased throughput by 31%, while Ghazal et al. [

65] evaluated a hardware prototype that confirmed feasibility in practical deployments. These studies highlight the diversity of ML and Hybrid methods.

4.2. Reinforcement Learning (RL) Based Approaches

Reinforcement learning (RL) has emerged as a highly promising approach for adaptive traffic signal control. These approaches learn from dynamic environments and adjust decisions in real time, giving RL-based models superior adaptability and responsiveness relative to conventional traffic signal control systems.

Among the reviewed models in

Section 3.2, PressLight [

33] stands out for its performance due to its strong theoretical foundation and practical success in managing the traffic signal in real time. PressLight aligns its reward design with traffic flow equations, ensuring both stability and optimal throughput based on the Max Pressure principle. Some other models use images as their main input or depend on heuristic reward settings to understand traffic. PressLight overcomes these challenges by using structured traffic features and pressure-based feedback for learning. This approach achieved remarkable results, reducing average travel times by more than 30% compared to traditional systems in synthetic simulations. It also performed better than both traditional traffic signal systems and other RL-based methods in real-world scenarios.

There are several other RL-based models discussed in the review paper that also offer special strengths or features. IntelliLight [

29] enhances interpretability by introducing memory and phase gate mechanisms, achieving a reduction of up to 72% in queue length. FRAP [

37] introduces symmetry-aware learning to handle rotated traffic patterns without retraining. AttendLight [

47] uses dual attention mechanisms to support multiple intersection types and achieved a 46% improvement in travel time over fixed-time systems. The Q-function approximator by Guo et al. [

38] emphasized spatial-temporal awareness, while Joo et al. [

105] and Joo & Lim [

39] tackled signal timing fairness and efficiency using Q-learning and DQNs.

A particularly innovative solution is Robust Deep RL by Tan et al. [

30], which addresses noisy or imperfect sensor data. By injecting synthetic noise during training and leveraging Double DQNs, their model learns to make stable decisions even in degraded sensing conditions. The most recent MARL-based models, such as MACOPO [

42] and MAGSAC [

43], represent an important step beyond single-intersection optimization.

Overall, RL-based methods deliver notable improvements in performance metrics like travel time, queue length, waiting time, fuel consumption, and intersection throughput. The detailed comparative evaluation of these RL models is shown in

Table 2, where for each method, we list the percentage improvements achieved for each metric. This table has been evaluated across two main simulation platforms, SUMO and CityFlow, using synthetic and real-world datasets.

Within CityFlow simulation platforms, using datasets from Jinan, Hangzhou, and Atlanta, FRAP [

37] reported the highest travel time reduction of 47.69%, which is better than both PressLight [

33], which achieved a 38.8% reduction, and IntelliLight [

29], which demonstrated a 40.26% reduction under similar conditions. Additionally, AttendLight [

47] demonstrated more significant improvements in travel time (9–46%) and showed better adaptability to different intersection layouts, which were not considered in earlier models. The most recent method, MAGSAC [

43], showed 34.7% travel time reduction on small synthetic grids and up to 90.9% reduction on larger grids, which is significantly outperforming FRAP and PressLight in terms of large networks.

Within SUMO simulation platforms, Robust Deep RL [

30] worked better than a regular RL model, achieving ∼76% robustness under noise and up to 78% better waiting time performance. Guo et al. [

38] achieved shortened queue lengths by 27–73% and reduced waiting times by 42–79%, which is stronger than Robust RL in terms of queue management, but they do not consider noisy data. Joo et al. [

105] and Joo & Lim [

39], both also tested within multi-intersection networks, reported a reduction of up to 50% in travel time and a 60% reduction in waiting time. Meanwhile, the MARL approach MACOPO [

42] was also tested on the same platform and achieved ∼74–90% queue length reduction, ∼82% waiting time reduction, and ∼5–59% emission reductions. This means that, compared to Guo et al. and Joo & Lim, MACOPO provides better improvements across all metrics. Additionally, it outperforms Robust DRL in terms of stability, working well for larger, multi-intersection networks.

The comparisons in

Table 2 show that in the CityFlow environment, FRAP achieved better travel time reduction than PressLight, and MAGSAC demonstrated even stronger scalability on large synthetic and real-world networks. In the SUMO environment, while models like Robust DRL, Guo et al., and Joo & Lim achieved solid performance. Similarly, MACOPO delivered the most consistent improvements across queue length, waiting time, and emissions. This shows that while PressLight is a practical and stable model for deployment, other approaches such as FRAP, MAGSAC, and MACOPO outperform it under specific datasets or conditions, particularly for large-scale, network-wide optimization.

5. Research Gap

AI-based traffic control systems have made significant progress in reducing traffic congestion and making signals more responsive to real-time traffic at intersections. Despite improvements in these systems, further research is needed to address the remaining gaps for optimal and practical real-world applications. For instance, a large portion of the existing RL-based systems, such as IntelliLight [

29], PressLight [

33], and FRAP [

37], show promising results in simulation-based environments like SUMO or CityFlow. Still, their performance and robustness in real-world deployments remain limited. The transition from simulation to reality introduces several practical issues, like failure of sensors, incomplete data from traffic cameras, and unpredictable (random) driving patterns of road users. These simulation systems use perfect, clean, and complete data, which is rarely the case in real urban conditions. Even models like the Robust Deep RL approach [

30] that attempt to handle noisy or imperfect inputs need further validation in large-scale deployments with varied traffic conditions, environmental factors (like weather), and network topology. Another major limitation is scalability and coordination. Many of the models in the current literature are designed for isolated intersections or small-scale networks. Some models, such as AttendLight [

47], attempt to work across different types of intersections using smart attention mechanisms. Recently, researchers tend to use Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning (MARL), such as MACOPO [

42] and MAGSAC [

43], where each intersection functions as an ’agent’ that learns to cooperate with neighboring intersections. The key challenge is getting all the traffic signals to work together as a team, and coordinating dozens of AI-powered signals is still an unsolved problem in the traffic management domain. Some important contextual and social considerations are often overlooked. Most models used metrics like travel time, queue length, or throughput to optimize for vehicle flow efficiency. Very few approaches, particularly PressLight [

33] and the Priority-Based Adaptive Traffic Signal Control System [

46], address the needs of pedestrian crossings, bicycle lanes, or public transit priority, which are fundamental to designing inclusive and equitable transportation systems. Moreover, emergency vehicle routing, school zones, and special event traffic require custom rule sets that are largely absent in current RL frameworks.

6. Future Considerations

With the increasing complexity of urban environments, the future work for the development of intelligent traffic control must aim higher to build systems that are not just smart, but also safe, inclusive, and adaptable to the full range of transportation challenges in modern cities. One of the most important directions for future development is the adoption of Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning (MARL). Unlike single-agent models that control one intersection at a time, MARL frameworks allow each intersection to act as an intelligent agent, capable of coordinating with neighboring intersections that help manage complex road networks and minimize traffic congestion across city blocks. However, challenges like agent synchronization, conflict resolution, and communication delays must be resolved to ensure real-time stability. Recent research has also explored Federated Learning (FL) [

120] in combination with MARL to improve scalability and privacy. FL allows intersections to train local models and only share high-level model updates, rather than sending raw traffic data to a central server. Future research could also draw inspiration from advances in computer vision and remote sensing. For example, techniques such as automated road extraction using deep learning frameworks [

121] can deliver detailed, up-to-date roadway data that enriches simulations and makes adaptive traffic systems more reliable and context-aware. Intelligent traffic systems should not only focus on reducing travel time, queue length, and increasing the throughput, but also consider the needs of pedestrian crossings, designated bike lanes, and signal priority for buses to build a truly inclusive and balanced traffic system. It is essential that, when developing advanced models that learn from data, patterns, or rewards, human privacy and security are taken into consideration. In addition, real-world situations like allowing emergency vehicles to pass quickly, managing traffic around schools, or handling road closures during events require custom rules and adaptive strategies that should be included in the RL-based models.

7. Conclusions

This study presents a detailed and thorough analysis of an Artificial Intelligence (AI)-driven traffic control system aimed at enhancing traffic flow and reducing congestion in urban areas. We’ve analyzed multiple advanced models from rule-based ML models to advanced deep reinforcement learning (DRL) frameworks like IntelliLight, FRAP, and PressLight. From the analysis, we found that RL-based models have demonstrated strong performance in simulation environments, based on significant reductions in various attributes, including travel time, waiting time, and queue length. These observations highlighted their capability to handle everything from single traffic intersections to larger urban networks with high traffic complexity. Despite these significant achievements, multiple challenges must be overcome before such systems can be widely deployed in real-world applications. These shortcomings resulted in a disconnect between simulation and real-world implementation, poor coordination across intersections, and limited consideration for emergency vehicles, pedestrians, and public transportation. These gaps show important directions for future research. In conclusion, the approaches reviewed in this paper reflect a major step forward in smart traffic management. With further development and careful integration with scalable multi-agent learning frameworks and federated learning into existing infrastructure, these approaches might help start a future where urban transportation is sustainable, more data-driven, faster, less wasteful, and equitable for everyone.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.R.K.K.; methodology, M.R.K.K. and A.M.; formal analysis, M.R.K.K. and A.M.; investigation, M.R.K.K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.R.K.K.; writing—review and editing, N.R., L.D. and A.M.; visualization, M.R.K.K. and A.M.; supervision, N.R. and L.D.; funding acquisition, N.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This material is based in part upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant Nos. CNS-2018611 and CNS-1920182.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Koźlak, A.; Wach, D. Causes of traffic congestion in urban areas. Case of Poland. In Proceedings of the SHS Web of Conferences. EDP Sciences; 2018; 57, p. 01019. [Google Scholar]

- Djahel, S.; Doolan, R.; Muntean, G.M.; Murphy, J. A communications-oriented perspective on traffic management systems for smart cities: Challenges and innovative approaches. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2014, 17, 125–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muralidharan, A.; Pedarsani, R.; Varaiya, P. Analysis of fixed-time control. Transportation Research Part B: Methodological 2015, 73, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavala, B.; Alférez, G.H. Proactive control of traffic in smart cities. In Proceedings of the Proceedings on the International Conference on Artificial Intelligence (ICAI). The Steering Committee of The World Congress in Computer Science, Computer …; 2015; p. 604. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, P.; Wu, G.; Boriboonsomsin, K.; Barth, M.J. Developing a framework of eco-approach and departure application for actuated signal control. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV). IEEE; 2015; pp. 796–801. [Google Scholar]

- Fellendorf, M. VISSIM: A microscopic simulation tool to evaluate actuated signal control including bus priority. In Proceedings of the 64th Institute of transportation engineers annual meeting. Springer Berlin/Heidelberg; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1994; 32, pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- De Oliveira, L.F.P.; Manera, L.T.; Da Luz, P.D.G. Development of a smart traffic light control system with real-time monitoring. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2020, 8, 3384–3393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Espinoza, A.; López-Bonilla, O.R.; García-Guerrero, E.E.; Tlelo-Cuautle, E.; López-Mancilla, D.; Hernández-Mejía, C.; Inzunza-González, E. Traffic flow prediction for smart traffic lights using machine learning algorithms. Technologies 2022, 10, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, M.; Abbas, S.; Ghazal, T.M.; Khan, M.A.; Sahawneh, N.; Ahmad, M. Smart cities: Fusion-based intelligent traffic congestion control system for vehicular networks using machine learning techniques. Egyptian Informatics Journal 2022, 23, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, H.; Thakur, J.S. Smart traffic control: machine learning for dynamic road traffic management in urban environments. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2025, 84, 10321–10345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manogaran, G.; Rodrigues, J.J.; Kozlov, S.A.; Manokaran, K. Conditional support-vector-machine-based shared adaptive computing model for smart city traffic management. IEEE Transactions on Computational Social Systems 2021, 9, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisheit, T.; Hoyer, R. Prediction of switching times of traffic actuated signal controls using support vector machines. In Advanced Microsystems for Automotive Applications 2014: Smart Systems for Safe, Clean and Automated Vehicles; Springer, 2014; pp. 121–129. [Google Scholar]

- Dogru, N.; Subasi, A. Traffic accident detection using random forest classifier. In Proceedings of the 2018 15th learning and technology conference (L&T); IEEE, 2018; pp. 40–45. [Google Scholar]

- Bafail, O. Optimizing smart city strategies: A data-driven analysis using random forest and regression analysis. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 11022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusiandro, M.A.; Nasution, S.M.; Setianingsih, C. Implementation of the advanced traffic management system using k-nearest neighbor algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2020 International conference on information technology systems and innovation (ICITSI). IEEE; 2020; pp. 149–154. [Google Scholar]

- Mladenović, D.; Janković, S.; Zdravković, S.; Mladenović, S.; Uzelac, A. Night traffic flow prediction using K-nearest neighbors algorithm. Operational research in engineering sciences: theory and applications 2022, 5, 152–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravish, R.; Swamy, S.R. Intelligent traffic management: A review of challenges, solutions, and future perspectives. Transport and Telecommunication 2021, 22, 163–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidi, H.; Kamankesh, A. An approach to intelligent traffic management system using a multi-agent system. International Journal of Intelligent Transportation Systems Research 2018, 16, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathiane, M.J.; Tu, C.; Adewale, P.; Nawej, M. A vehicle density estimation traffic light control system using a two-dimensional convolution neural network. Vehicles 2023, 5, 1844–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reza, S.; Oliveira, H.S.; Machado, J.J.; Tavares, J.M.R. Urban safety: an image-processing and deep-learning-based intelligent traffic management and control system. Sensors 2021, 21, 7705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saini, S.K.; Ghumman, M.S. Automated traffic management system using deep learning based object detection. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Machine Learning and Cybernetics (ICMLC). IEEE; 2022; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed, A.R.; Mohammed, S.A.; Shirmohammadi, S. Machine learning and deep learning based traffic classification and prediction in software defined networking. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Symposium on Measurements & Networking (M&N). IEEE; 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Salkham, A.a.; Cunningham, R.; Garg, A.; Cahill, V. A collaborative reinforcement learning approach to urban traffic control optimization. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE/WIC/ACM International Conference on Web Intelligence and Intelligent Agent Technology. IEEE; 2008; 2, pp. 560–566. [Google Scholar]

- Hegde, S.B.; Premasudha, B.; Hooli, A.C.; Akshay, M. A Review on Smart Traffic Management with Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the International Congress on Information and Communication Technology. Springer; 2024; pp. 455–470. [Google Scholar]

- Wiering, M.A.; et al. Multi-agent reinforcement learning for traffic light control. In Proceedings of the Machine Learning: Proceedings of the Seventeenth International Conference (ICML’2000); 2000; pp. 1151–1158. [Google Scholar]

- Ceylan, H.; Bell, M.G. Traffic signal timing optimisation based on genetic algorithm approach, including drivers’ routing. Transportation Research Part B: Methodological 2004, 38, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teklu, F.; Sumalee, A.; Watling, D. A genetic algorithm approach for optimizing traffic control signals considering routing. Computer-Aided Civil and Infrastructure Engineering 2007, 22, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Schrader, M.; Yoon, H.S.; Bittle, J.A. Optimal Traffic Signal Control Using Priority Metric Based on Real-Time Measured Traffic Information. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Zheng, G.; Yao, H.; Li, Z. Intellilight: A reinforcement learning approach for intelligent traffic light control. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 24th ACM SIGKDD international conference on knowledge discovery & data mining; 2018; pp. 2496–2505. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, K.L.; Sharma, A.; Sarkar, S. Robust deep reinforcement learning for traffic signal control. Journal of Big Data Analytics in Transportation 2020, 2, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregurić, M.; Vujić, M.; Alexopoulos, C.; Miletić, M. Application of deep reinforcement learning in traffic signal control: An overview and impact of open traffic data. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 4011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, F.; Yau, K.L.A.; Noor, R.M.; Wu, C.; Low, Y.C. Deep reinforcement learning for traffic signal control: A review. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 208016–208044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Chen, C.; Zheng, G.; Wu, K.; Gayah, V.; Xu, K.; Li, Z. Presslight: Learning max pressure control to coordinate traffic signals in arterial network. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD international conference on knowledge discovery & data mining; 2019; pp. 1290–1298. [Google Scholar]

- Ramadhan, S.A.; Sutarto, H.Y.; Kuswana, G.S.; Joelianto, E. Application of area traffic control using the max-pressure algorithm. Transportation planning and technology 2020, 43, 783–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercader, P.; Uwayid, W.; Haddad, J. Max-pressure traffic controller based on travel times: An experimental analysis. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies 2020, 110, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukerche, A.; Zhong, D.; Sun, P. A novel reinforcement learning-based cooperative traffic signal system through max-pressure control. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2021, 71, 1187–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.; Xiong, Y.; Zang, X.; Feng, J.; Wei, H.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Xu, K.; Li, Z. Learning phase competition for traffic signal control. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 28th ACM international conference on information and knowledge management, 2019, pp. 1963–1972.

- Guo, M.; Wang, P.; Chan, C.Y.; Askary, S. A reinforcement learning approach for intelligent traffic signal control at urban intersections. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Intelligent Transportation Systems Conference (ITSC). IEEE, 2019, pp. 4242–4247.

- Joo, H.; Lim, Y. Traffic signal time optimization based on deep Q-network. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 9850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.A.; Elhadef, M.; Khan, M.U.G. Collaborative traffic signal automation using deep q-learning. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 136015–136032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Du, X.; Wang, G.; Han, Z. A deep q learning network for traffic lights’ cycle control in vehicular networks. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2019, 68, 1243–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, F.; Dong, W.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, F.; Kong, Y.; Yang, Q. Two-layer coordinated reinforcement learning for traffic signal control in traffic network. Expert Systems with Applications 2024, 235, 121111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, J.; Meng, S.; Hou, J.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, X.; Jiang, R.; Qi, L.; Li, Q. Graph-based cooperation multi-agent reinforcement learning for intelligent traffic signal control. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L.; Wu, Y.; Qiao, C.; Tian, Y. Multiagent soft actor–critic for traffic light timing. Journal of Transportation Engineering, Part A: Systems 2023, 149, 04022133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleko, D.R.; Djahel, S. An efficient adaptive traffic light control system for urban road traffic congestion reduction in smart cities. Information 2020, 11, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, M.A.; Rehena, Z. Priority-based adaptive traffic signal control system for smart cities. SN Computer Science 2022, 3, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oroojlooy, A.; Nazari, M.; Hajinezhad, D.; Silva, J. Attendlight: Universal attention-based reinforcement learning model for traffic signal control. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2020, 33, 4079–4090. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Martin, M.; Carro, B.; Sanchez-Esguevillas, A. Neural network architecture based on gradient boosting for IoT traffic prediction. Future Generation Computer Systems 2019, 100, 656–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Que, Z.; Hou, J.; Du, S.; Song, Y. An efficient convolutional neural network for small traffic sign detection. Journal of Systems Architecture 2019, 97, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghdam, H.H.; Heravi, E.J.; Puig, D. A practical approach for detection and classification of traffic signs using convolutional neural networks. Robotics and autonomous systems 2016, 84, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, H. Prediction of road traffic congestion based on random forest. In Proceedings of the 2017 10th international symposium on computational intelligence and design (ISCID). IEEE, 2017, Vol. 2, pp. 361–364.

- Xu, Y.; Xi, Y.; Li, D.; Zhou, Z. Traffic signal control based on Markov decision process. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2016, 49, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, T. Constrained Markov Decision Processes for Intelligent Traffic. In Proceedings of the 2019 10th International Conference on Computing, Communication and Networking Technologies (ICCCNT). IEEE, 2019, pp. 1–7.

- Alagoz, O.; Hsu, H.; Schaefer, A.J.; Roberts, M.S. Markov decision processes: a tool for sequential decision making under uncertainty. Medical Decision Making 2010, 30, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Zariphopoulou, T.; Zhou, X. Exploration versus exploitation in reinforcement learning: A stochastic control approach. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1812.01552 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, B.; Kim, M.; Harerimana, G.; Kim, J.W. Q-learning algorithms: A comprehensive classification and applications. IEEE access 2019, 7, 133653–133667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Liu, X.; Xu, Y.; Guo, J. A deep Q-network (DQN) based path planning method for mobile robots. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Information and Automation (ICIA). IEEE, 2018, pp. 366–371.

- Silver, D.; Lever, G.; Heess, N.; Degris, T.; Wierstra, D.; Riedmiller, M. Deterministic policy gradient algorithms. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. Pmlr, 2014, pp. 387–395.

- Kakade, S.M. A natural policy gradient. Advances in neural information processing systems 2001, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Hariharan, N.; Paavai, A.G. A Brief Study of Deep Reinforcement Learning with Epsilon-Greedy Exploration. International Journal of Computing and Digital Systems 2022, 11, 541–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirchandani, P.; Head, L. A real-time traffic signal control system: architecture, algorithms, and analysis. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies 2001, 9, 415–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]