Submitted:

27 October 2025

Posted:

28 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Hyperinsulinemia Is Not the Predecessor of Insulin Resistance

3. The Origin of Insulin Resistance Is a Defect of Estrogen Signaling, While Hyperinsulinemia Is a Compensatory Effort for Improving Estrogen Regulation

4. The Defect of Estrogen Signaling Is the Origin of Genomic Instability and Insulin Resistance in BRCA Gene Mutation Carriers

5. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Originates from the Disruption of Estrogen Signaling via CYP19A Gene Mutation

6. Estrogen Is the Principal Regulator of All Cellular Functions in Mammalians

7. Adipose Tissue Ensures Metabolic Balance and Energy Homeostasis via Estrogen Regulation

8. Skeletal Muscle Contraction Improves Insulin Sensitivity via Rapid Unliganded Activation of ERs by IGF-1 Receptor

9. Estrogen Regulation of Multitude Functions of the Liver

10. Hypothalamic Estrogen Signaling Is the Central Regulator of Somatic, Reproductive and Mental Health

11. The Origin of Cancer Development by Unhealthy Lifestyle Factors and Bad Habits: A Defect of Estrogen Signaling and the Associated Insulin Resistance

12. Conclusion

References

- Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2022: Globocan estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. Cancer J Phys 2024; 74(3): 229-63. Epub 2024 Apr 4. PMID: 38572751. [CrossRef]

- Kontomanolis EN, Koutras A, Syllaios A, Schizas D, Mastoraki A, Garmpis N, Diakosavvas M, Angelou K, Tsatsaris G, Pagkalos A, Ntounis T, Fasoulakis Z. Role of Oncogenes and Tumor-suppressor Genes in Carcinogenesis: A Review. Anticancer Res. 2020 Nov;40(11):6009-6015. PMID: 33109539. [CrossRef]

- Mbemi A, Khanna S, Njiki S, Yedjou CG, Tchounwou PB. Impact of Gene-Environment Interactions on Cancer Development. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 Nov 3;17(21):8089. PMID: 33153024; PMCID: PMC7662361. [CrossRef]

- Sinkala M. Mutational landscape of cancer-driver genes across human cancers. Sci Rep. 2023 Aug 7;13(1):12742. PMID: 37550388; PMCID: PMC10406856. [CrossRef]

- Suba Z. DNA Damage Responses in Tumors Are Not Proliferative Stimuli, but Rather They Are DNA Repair Actions Requiring Supportive Medical Care. Cancers (Basel). 2024 Apr 19;16(8):1573. PMID: 38672654; PMCID: PMC11049279. [CrossRef]

- Beatson G.T. On the treatment of inoperable cases of carcinoma of the mamma: Suggestions for a new method of treatment, with illustrative cases. Lancet. 1896;2:104–107. [CrossRef]

- Boyd S. OOPHORECTOMY IN CANCER OF THE BREAST. BMJ. 1902;1:110–111. [CrossRef]

- Suba Z. Estrogen Regulated Genes Compel Apoptosis in Breast Cancer Cells, Whilst Stimulate Antitumor Activity in Peritumoral Immune Cells in a Janus-Faced Manner. Curr Oncol. 2024 Aug 24;31(9):4885-4907. PMID: 39329990; PMCID: PMC11431267. [CrossRef]

- Reaven GM. Banting Lecture 1988. Role of insulin resistance in human disease. 1988. Nutrition. 1997 Jan;13(1):65; discussion 64, 66. PMID: 9058458. [CrossRef]

- Prasad H, Ryan DA, Celzo MF, Stapleton D. Metabolic syndrome: definition and therapeutic implications. Postgrad. Med. 2012 Jan;124(1):21-30. PMID: 22314111. [CrossRef]

- Thomas DD, Corkey BE, Istfan NW, Apovian CM. Hyperinsulinemia: An Early Indicator of Metabolic Dysfunction. J Endocr Soc. 2019 Jul 24;3(9):1727-1747. PMID: 31528832; PMCID: PMC6735759. [CrossRef]

- Nolan CJ, Prentki M. Insulin resistance and insulin hypersecretion in the metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes: Time for a conceptual framework shift. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2019 Mar;16(2):118-127. Epub 2019 Feb 15. PMID: 30770030. [CrossRef]

- Galicia-Garcia U, Benito-Vicente A, Jebari S, Larrea-Sebal A, Siddiqi H, Uribe KB, Ostolaza H, Martín C. Pathophysiology of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Aug 30;21(17):6275. PMID: 32872570; PMCID: PMC7503727. [CrossRef]

- Ormazabal V, Nair S, Elfeky O, Aguayo C, Salomon C, Zuñiga FA. Association between insulin resistance and the development of cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2018 Aug 31;17(1):122. PMID: 30170598; PMCID: PMC6119242. [CrossRef]

- Szablewski L. Insulin Resistance: The Increased Risk of Cancers. Curr Oncol. 2024 Feb 13;31(2):998-1027. PMID: 38392069; PMCID: PMC10888119. [CrossRef]

- Ciarambino T, Crispino P, Guarisco G, Giordano M. Gender Differences in Insulin Resistance: New Knowledge and Perspectives. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2023 Sep 27;45(10):7845-7861. PMID: 37886939; PMCID: PMC10605445. [CrossRef]

- Mauvais-Jarvis F, Clegg DJ, Hevener AL. The role of estrogens in control of energy balance and glucose homeostasis. Endocr Rev. 2013 Jun;34(3):309-38. Epub 2013 Mar 4. PMID: 23460719; PMCID: PMC3660717. [CrossRef]

- Suba Z. Low Estrogen Exposure and/or Defective Estrogen Signaling Induces Disturbances in Glucose Uptake and Energy Expenditure. J Diabetes Metab 2013, 4:5. [CrossRef]

- Hevener AL, Clegg DJ, Mauvais-Jarvis F. Impaired estrogen receptor action in the pathogenesis of the metabolic syndrome. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2015 Dec 15;418 Pt 3(Pt 3):306-21. Epub 2015 May 29. PMID: 26033249; PMCID: PMC5965692. [CrossRef]

- Betai D, Ahmed AS, Saxena P, Rashid H, Patel H, Shahzadi A, Mowo-Wale AG, Nazir Z. Gender Disparities in Cardiovascular Disease and Their Management: A Review. Cureus. 2024 May 5;16(5):e59663. PMID: 38836150; PMCID: PMC11148660. [CrossRef]

- Reckelhoff JF. Sex steroids, cardiovascular disease, and hypertension: unanswered questions and some speculations. Hypertension. 2005 Feb;45(2):170-4. Epub 2004 Dec 6. PMID: 15583070. [CrossRef]

- Xiang D, Liu Y, Zhou S, Zhou E, Wang Y. Protective Effects of Estrogen on Cardiovascular Disease Mediated by Oxidative Stress. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2021 Jun 28;2021:5523516. PMID: 34257804; PMCID: PMC8260319. [CrossRef]

- Selvaraj RC, Cioffi G, Waite KA, Jackson SS, Barnholtz-Sloan JS. A Pan-Cancer Analysis of Age and Sex Differences in Cancer Incidence and Survival in the United States, 2001-2020. Cancers (Basel). 2025 Jan 24;17(3):378. PMID: 39941747; PMCID: PMC11815994. [CrossRef]

- Suba Z. Gender-related hormonal risk factors for oral cancer. Pathol Oncol Res. 2007;13(3):195-202. Epub 2007 Oct 7. PMID: 17922048. [CrossRef]

- Heer E, Harper A, Escandor N, Sung H, McCormack V, Fidler-Benaoudia MM. Global burden and trends in premenopausal and postmenopausal breast cancer: a population-based study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020 Aug;8(8):e1027-e1037. PMID: 32710860. [CrossRef]

- Ohkuma T, Iwase M, Fujii H, Ide H, Kaizu S, Jodai T, Kikuchi Y, Idewaki Y, Sumi A, Nakamura U, Kitazono T. Joint impact of modifiable lifestyle behaviors on glycemic control and insulin resistance in patients with type 2 diabetes: the Fukuoka Diabetes Registry. Diabetol Int. 2017 Feb 17;8(3):296-305. PMID: 30603335; PMCID: PMC6224889. [CrossRef]

- Bruckner F, Gruber JR, Ruf A, Edwin Thanarajah S, Reif A, Matura S. Exploring the Link between Lifestyle, Inflammation, and Insulin Resistance through an Improved Healthy Living Index. Nutrients. 2024 Jan 29;16(3):388. PMID: 38337673; PMCID: PMC10857191. [CrossRef]

- Ariazi EA, Ariazi JL, Cordera F, Jordan VC. Estrogen receptors as therapeutic targets in breast cancer. Curr Top Med Chem. 2006;6(3):181-202. PMID: 16515478.

- Hayes DF. Tamoxifen: Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde? J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004 Jun 16;96(12):895-7. PMID: 15199102. [CrossRef]

- Suba Z. Compensatory Estrogen Signal Is Capable of DNA Repair in Antiestrogen-Responsive Cancer Cells via Activating Mutations. J Oncol. 2020 Jul 28;2020:5418365. PMID: 32774370; PMCID: PMC7407016. [CrossRef]

- Ramteke P, Deb A, Shepal V, Bhat MK. Hyperglycemia Associated Metabolic and Molecular Alterations in Cancer Risk, Progression, Treatment, and Mortality. Cancers (Basel). 2019 Sep 19;11(9):1402. PMID: 31546918; PMCID: PMC6770430. [CrossRef]

- Lee HM, Lee HJ, Chang JE. Inflammatory Cytokine: An Attractive Target for Cancer Treatment. Biomedicines. 2022 Aug 29;10(9):2116. PMID: 36140220; PMCID: PMC9495935. [CrossRef]

- Rho O, Kim DJ, Kiguchi K, Digiovanni J. Growth factor signaling pathways as targets for prevention of epithelial carcinogenesis. Mol Carcinog. 2011 Apr;50(4):264-79. Epub 2010 Jul 20. PMID: 20648549; PMCID: PMC3005141. [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Ghani M, DeFronzo RA. Insulin Resistance and Hyperinsulinemia: the Egg and the Chicken. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021 Mar 25;106(4):e1897-e1899. PMID: 33522574; PMCID: PMC7993580. [CrossRef]

- Wilcox G. Insulin and insulin resistance. Clin Biochem Rev. 2005 May;26(2):19-39. PMID: 16278749; PMCID: PMC1204764.

- Johnson AM, Olefsky JM. The origins and drivers of insulin resistance. Cell. 2013 Feb 14;152(4):673-84. PMID: 23415219. [CrossRef]

- Freeman AM, Acevedo LA, Pennings N. Insulin Resistance. 2023 Aug 17. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan–. PMID: 29939616.

- Janssen JAMJL. Hyperinsulinemia and Its Pivotal Role in Aging, Obesity, Type 2 Diabetes, Cardiovascular Disease and Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Jul 21;22(15):7797. PMID: 34360563; PMCID: PMC8345990. [CrossRef]

- Zhang AMY, Wellberg EA, Kopp JL, Johnson JD. Hyperinsulinemia in Obesity, Inflammation, and Cancer. Diabetes Metab J. 2021 May;45(3):285-311. Epub 2021 Mar 29. Erratum in: Diabetes Metab J. 2021 Jul;45(4):622. PMID: 33775061; PMCID: PMC8164941. https://doi.org/10.4093/dmj.2021.0131. [CrossRef]

- Houston EJ, Templeman NM. Reappraising the relationship between hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance in PCOS. J Endocrinol. 2025 Mar 12;265(2):e240269. PMID: 40013621; PMCID: PMC11906131. [CrossRef]

- Rangraze IR, El-Tanani M, Arman Rabbani S, Babiker R, Matalka II, Rizzo M. Diabetes and its Silent Partner: A Critical Review of Hyperinsulinemia and its Complications. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2025;21(9):e15733998311738. PMID: 39192649. [CrossRef]

- Janssen JAMJL. Overnutrition, Hyperinsulinemia and Ectopic Fat: It Is Time for A Paradigm Shift in the Management of Type 2 Diabetes. Int J Mol Sci. 2024 May 17;25(10):5488. PMID: 38791525; PMCID: PMC11121669. [CrossRef]

- Nijenhuis-Noort EC, Berk KA, Neggers SJCMM, Lely AJV. The Fascinating Interplay between Growth Hormone, Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1, and Insulin. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul). 2024 Feb;39(1):83-89. Epub 2024 Jan 9. PMID: 38192102; PMCID: PMC10901670. [CrossRef]

- Giustina A, Berardelli R, Gazzaruso C, Mazziotti G. Insulin and GH-IGF-I axis: endocrine pacer or endocrine disruptor? Acta Diabetol. 2015 Jun;52(3):433-43. Epub 2014 Aug 14. PMID: 25118998. [CrossRef]

- Macvanin M, Gluvic Z, Radovanovic J, Essack M, Gao X, Isenovic ER. New insights on the cardiovascular effects of IGF-1. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023 Feb 9;14:1142644.. PMID: 36843588; PMCID: PMC9947133. [CrossRef]

- Suba Z. DNA stabilization by the upregulation of estrogen signaling in BRCA gene mutation carriers. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2015 May 15;9:2663-75. PMID: 26028963; PMCID: PMC4440422. [CrossRef]

- Yan H, Yang W, Zhou F, Li X, Pan Q, Shen Z, Han G, Newell-Fugate A, Tian Y, Majeti R, Liu W, Xu Y, Wu C, Allred K, Allred C, Sun Y, Guo S. Estrogen Improves Insulin Sensitivity and Suppresses Gluconeogenesis via the Transcription Factor Foxo1. Diabetes. 2019 Feb;68(2):291-304. Epub 2018 Nov 28. PMID: 30487265; PMCID: PMC6341301. [CrossRef]

- Kuryłowicz A. Estrogens in Adipose Tissue Physiology and Obesity-Related Dysfunction. Biomedicines. 2023 Feb 24;11(3):690. PMID: 36979669; PMCID: PMC10045924. [CrossRef]

- Gregorio KCR, Laurindo CP, Machado UF. Estrogen and Glycemic Homeostasis: The Fundamental Role of Nuclear Estrogen Receptors ESR1/ESR2 in Glucose Transporter GLUT4 Regulation. Cells. 2021 Jan 7;10(1):99. PMID: 33430527; PMCID: PMC7827878. [CrossRef]

- Rajpathak SN, Gunter MJ, Wylie-Rosett J, Ho GY, Kaplan RC, Muzumdar R, Rohan TE, Strickler HD. The role of insulin-like growth factor-I and its binding proteins in glucose homeostasis and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2009 Jan;25(1):3-12. PMID: 19145587; PMCID: PMC4153414. [CrossRef]

- Salminen A, Kaarniranta K, Kauppinen A. Insulin/IGF-1 signaling promotes immunosuppression via the STAT3 pathway: impact on the aging process and age-related diseases. Inflamm Res. 2021 Dec;70(10-12):1043-1061. Epub 2021 Sep 2. PMID: 34476533; PMCID: PMC8572812. [CrossRef]

- Ohlsson C, Hammarstedt A, Vandenput L, Saarinen N, Ryberg H, Windahl SH, Farman HH, Jansson JO, Movérare-Skrtic S, Smith U, Zhang FP, Poutanen M, Hedjazifar S, Sjögren K. Increased adipose tissue aromatase activity improves insulin sensitivity and reduces adipose tissue inflammation in male mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2017 Oct 1;313(4):E450-E462. Epub 2017 Jun 27. PMID: 28655716; PMCID: PMC5668598. [CrossRef]

- Saponaro C, Gaggini M, Carli F, Gastaldelli A. The Subtle Balance between Lipolysis and Lipogenesis: A Critical Point in Metabolic Homeostasis. Nutrients. 2015 Nov 13;7(11):9453-74. PMID: 26580649; PMCID: PMC4663603. [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti P, Kim JY, Singh M, Shin YK, Kim J, Kumbrink J, Wu Y, Lee MJ, Kirsch KH, Fried SK, Kandror KV. Insulin inhibits lipolysis in adipocytes via the evolutionarily conserved mTORC1-Egr1-ATGL-mediated pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2013 Sep;33(18):3659-66. Epub 2013 Jul 15. PMID: 23858058; PMCID: PMC3753874. [CrossRef]

- Ko SH, Kim HS. Menopause-Associated Lipid Metabolic Disorders and Foods Beneficial for Postmenopausal Women. Nutrients. 2020 Jan 13;12(1):202. PMID: 31941004; PMCID: PMC7019719. [CrossRef]

- Yin C, Liu WH, Liu Y, Wang L, Xiao Y. PID1 alters the antilipolytic action of insulin and increases lipolysis via inhibition of AKT/PKA pathway activation. PLoS One. 2019 Apr 16;14(4):e0214606. Erratum in: PLoS One. 2019 Jun 17;14(6):e0218721. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0218721. PMID: 30990811; PMCID: PMC6467375. [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi T, Kubota T, Nakanishi Y, Tsugawa H, Suda W, Kwon AT, Yazaki J, Ikeda K, Nemoto S, Mochizuki Y, Kitami T, Yugi K, Mizuno Y, Yamamichi N, Yamazaki T, Takamoto I, Kubota N, Kadowaki T, Arner E, Carninci P, Ohara O, Arita M, Hattori M, Koyasu S, Ohno H. Gut microbial carbohydrate metabolism contributes to insulin resistance. Nature. 2023 Sep;621(7978):389-395. Epub 2023 Aug 30. PMID: 37648852; PMCID: PMC10499599. [CrossRef]

- Semo D, Reinecke H, Godfrey R. Gut microbiome regulates inflammation and insulin resistance: a novel therapeutic target to improve insulin sensitivity. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024 Feb 21;9(1):35. PMID: 38378663; PMCID: PMC10879501. [CrossRef]

- Wang H, Shi F, Zheng L, Zhou W, Mi B, Wu S, Feng X. Gut microbiota has the potential to improve health of menopausal women by regulating estrogen. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2025 Jun 9;16:1562332. PMID: 40551890; PMCID: PMC12183514. [CrossRef]

- Rishabh, Bansal S, Goel A, Gupta S, Malik D, Bansal N. Unravelling the Crosstalk between Estrogen Deficiency and Gut-biotaDysbiosis in the Development of Diabetes Mellitus. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2024;20(10):e240124226067. PMID: 38275037. [CrossRef]

- Link CD. Is There a Brain Microbiome? Neurosci Insights. 2021 May 27;16:26331055211018709. PMID: 34104888; PMCID: PMC8165828. [CrossRef]

- Kim J-a, Wei Y, Showers JR. Role of Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Insulin Resistance. Circulation Research 2008; 102(4) 401-14. [CrossRef]

- Huang, X., Pan, CH., Yin, F. et al. The Role of Estrogen in Mitochondrial Disease. Cell Mol Neurobiol 2025 45, 68. [CrossRef]

- Tao Z, Cheng Z. Hormonal regulation of metabolism-recent lessons learned from insulin and estrogen. Clin Sci (Lond). 2023 Mar 31;137(6):415-434. PMID: 36942499; PMCID: PMC10031253. [CrossRef]

- Miki Y, Swensen J, Shattuck-Eidens D, Futreal PA, Harshman K, Tavtigian S et al. A strong candidate for the breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility gene BRCA1. Science 1994; 266(5182): 66-71.

- Wooster R, Bignell G, Lancaster J, Swift S, Seal S, Mangion J et al. Identification of the breast cancer susceptibility gene BRCA2. Nature 1995; 378(6559): 789-92.

- Venkitaraman AR. Cancer susceptibility and the functions of BRCA1 and BRCA2. Cell 2002; 108: 171–182.

- Gorski JJ, Kennedy RD, Hosey AM, Harkin DP. The complex relationship between BRCA1 and ER alpha in hereditary breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2009; 15(5): 1514-8. [CrossRef]

- Wang L, Di LJ. BRCA1 and estrogen/estrogen receptor in breast cancer: where they interact? Int J Biol Sci 2014; 10(5): 566-75.

- Lakhani SR, Van De Vijver MJ, Jacquemier J, et al. The pathology of familial breast cancer: predictive value of immunohistochemical markers estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, HER-2, and p53 in patients with mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2. J Clin Oncol. 2002; 20: 2310–8. [CrossRef]

- Sorlie T, Perou CM, Tibshirani R, et al. Gene expression patterns of breast carcinomas distinguish tumor subclasses with clinical implications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001; 98: 10869–74.

- Santana dos Santos, E.; Lallemand, F.; Petitalot, A.; Caputo, S.M.; Rouleau, E. HRness in Breast and Ovarian Cancers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3850. [CrossRef]

- Spillman MA, Bowcock AM. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mRNA levels are coordinately elevated in human breast cancer cells in response to estrogen. Oncogene. 1996; 13: 1639–45.

- Suba Z. Triple-negative breast cancer risk in women is defined by the defect of estrogen signaling: preventive and therapeutic implications. OncoTargets Ther 2014; 7: 147-64.

- Fan S, Wang J, Yuan R, et al. BRCA1 inhibition of estrogen receptor signaling in transfected cells. Science 1999; 284: 1354–6. [CrossRef]

- Xu J, Fan S, Rosen EM. Regulation of the estrogen-inducible gene expression profile by the breast cancer susceptibility gene BRCA1. Endocrinology 2005; 146: 2031–47.

- Ma Y, Fan S, Hu C, Meng Q, Fuqua SA, Pestell RG. et al. BRCA1 regulates acetylation and ubiquitination of estrogen receptor-alpha. Molecular Endocrinology 2010; 24: 76–90. [CrossRef]

- Fan S, Ma YX, Wang C, et al. p300 Modulates the BRCA1 inhibition of estrogen receptor activity. Cancer Res 2002; 62: 141–51.

- Wang C, Fan S, Li Z, Fu M, Rao M, Ma Y. et al. Cyclin D1 antagonizes BRCA1 repression of estrogen receptor alpha activity. Cancer research 2005; 65: 6557–67.

- Fan S, Ma YX, Wang C, Yuan RQ, Meng Q, Wang JA, Erdos M, Goldberg ID, Webb P, Kushner PJ, Pestell RG, Rosen EM. Role of direct interaction in BRCA1 inhibition of estrogen receptor activity. Oncogene 2001; 20(1): 77-87. [CrossRef]

- Russo J., Russo I. H. Toward a unified concept of mammary carcinogenesis Aldaz M. C. Gould M. N. McLachlan J. Slaga T. J. eds. Progress in Clinical and Biological Research: 1-16, Wiley-Liss New York 1997.

- Hosey AM, Gorski JJ, Murray MM, Quinn JE, Chung WY, Stewart GE. et al. Molecular basis for estrogen receptor alpha deficiency in BRCA1-linked breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2007; 99: 1683–94. [CrossRef]

- Burga, L.N., Hu, H., Juvekar, A. et al. Loss of BRCA1 leads to an increase in epidermal growth factor receptor expression in mammary epithelial cells, and epidermal growth factor receptor inhibition prevents estrogen receptor-negative cancers in BRCA1-mutant mice. Breast Cancer Res 2011; 13: R30.

- Ma Y, Hu Ch, Riegel AT, Fan S, Rosen EM. Growth factor signaling pathways modulate BRCA1 repression of estrogen receptor-alpha activity. Mol Endocrinol 2007; 21(8): 1905-23.

- Ghosh S, Lu Y, Katz A, Hu Y, Li R. Tumor suppressor BRCA1 inhibits a breast cancer-associated promoter of the aromatase gene (CYP19) in human adipose stromal cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2007; 292: 246–252. [CrossRef]

- Sau A, Lau R, Cabrita MA, Nolan E, Crooks PA et al. Persistent Activation of NF-κB in BRCA1-Deficient Mammary Progenitors Drives Aberrant Proliferation and Accumulation of DNA Damage Cell Stem Cell 2016; 19(1): 52-65.

- Zheng L, Annab LA, Afshari CA, Lee WH, Boyer TG. BRCA1 mediates ligand-independent transcriptional repression of the estrogen receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001; 98:9587–92. [CrossRef]

- Arnold A , Papanikolaou A. Cyclin D1 in Breast Cancer Pathogenesis. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23(18): 4215-24.

- Wang X, El-Halaby AA, Zhang H, Yang Q, Laughlin TS, Rothberg PG, Skinner K, Hicks DG. p53 alteration in morphologically normal/benign breast luminal cells in BRCA carriers with or without history of breast cancer. Hum Pathol. 2017 Oct;68:22-25. Epub 2017 Apr 21. PMID: 28438622. [CrossRef]

- Oktay K, Kim JY, Barad D, Babayev SN. Association of BRCA1 mutations with occult primary ovarian insufficiency: a possible explanation for the link between infertility and breast/ovarian cancer risks. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28(2): 240-4.

- Lin WT, Beattie M, Chen LM, Oktay K, Crawford SL, Gold EB, Cedars M, Rosen M. Comparison of age at natural menopause in BRCA1/2 mutation carriers with a non-clinic-based sample of women in northern California. Cancer 2013; 119(9): 1652-9.

- Chand AL, Simpson ER, Clyne CD. Aromatase expression is increased in BRCA1 mutation carriers. BMC Cancer. 2009; 9: 148. [CrossRef]

- Bruno E, Manoukian S, Venturelli E, Oliverio A, Rovera F, Iula G, Morelli D, Peissel B, Azzolini J, Roveda E, Pasanisi P. Adherence to Mediterranean Diet and Metabolic Syndrome in BRCA Mutation Carriers. Integr Cancer Ther. 2018 Mar;17(1):153-160. Epub 2017 Jul 25. PMID: 28741383; PMCID: PMC5950953. [CrossRef]

- Lentscher JA, Decherney AH. Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis of Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2021 Mar 1;64(1):3-11. PMID: 32701517; PMCID: PMC10683967. [CrossRef]

- Zańko A, Siewko K, Krętowski AJ, Milewski R. Lifestyle, Insulin Resistance and Semen Quality as Co-Dependent Factors of Male Infertility. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Dec 30;20(1):732. PMID: 36613051; PMCID: PMC9819053. [CrossRef]

- Dong J, Rees DA. Polycystic ovary syndrome: pathophysiology and therapeutic opportunities. BMJ Med. 2023 Oct 12;2(1):e000548. PMID: 37859784; PMCID: PMC10583117. [CrossRef]

- Blackwood SJ, Tischer D, Pontén M, Moberg M, Katz A. Relationship between insulin sensitivity and hyperinsulinemia in early insulin resistance is sex-dependent. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2025 May 13:dgaf282. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 40356550. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Jiménez JL, Barrera D, Espinoza-Simón E, González J, Ortíz-Hernández R, Escobar L, Echeverría O, Torres-Ramírez N. Polycystic ovarian syndrome: signs and feedback effects of hyperandrogenism and insulin resistance. Gynecological Endocrinology. 2022 Jan 2;38(1):2-9.

- Bulun SE. Aromatase and estrogen receptor α deficiency. Fertil Steril. 2014 Feb;101(2):323-9. PMID: 24485503; PMCID: PMC3939057. [CrossRef]

- Suba Z. Diverse pathomechanisms leading to the breakdown of cellular estrogen surveillance and breast cancer development: new therapeutic strategies. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2014 Sep 11;8:1381-90. PMID: 25246776; PMCID: PMC4166254. [CrossRef]

- Quaynor SD, Stradtman EW Jr, Kim HG, Shen Y, Chorich LP, Schreihofer DA, Layman LC. Delayed puberty and estrogen resistance in a woman with estrogen receptor α variant. N Engl J Med. 2013 Jul 11;369(2):164-71. PMID: 23841731; PMCID: PMC3823379. [CrossRef]

- Scicchitano P, Dentamaro I, Carbonara R, Bulzis G, Dachille A, Caputo P, Riccardi R, Locorotondo M, Mandurino C, Matteo Ciccone M. Cardiovascular Risk in Women With PCOS. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 2012; 10(4):611-8. Epub 2012 Sep 30. PMID: 23843832; PMCID: PMC3693634. [CrossRef]

- Bird ST, Hartzema AG, Brophy JM, Etminan M, Delaney JA. Risk of venous thromboembolism in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a population-based matched cohort analysis. CMAJ. 2013 Feb 5;185(2):E115-20. Epub 2012 Dec 3. PMID: 23209115; PMCID: PMC3563911. [CrossRef]

- Wang J, Yin T, Liu S. Dysregulation of immune response in PCOS organ system. Front Immunol. 2023 May 5;14:1169232. PMID: 37215125; PMCID: PMC10196194. [CrossRef]

- Yuk JS, Noh JH, Han GH, Yoon SH, Kim M. Risk of cancers in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: Cohort study based on health insurance database in South Korea. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2025 Sep 27. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 41014020. [CrossRef]

- Ignatov A, Ortmann O. Endocrine Risk Factors of Endometrial Cancer: Polycystic Ovary Syndrome, Oral Contraceptives, Infertility, Tamoxifen. Cancers (Basel). 2020 Jul 2;12(7):1766. PMID: 32630728; PMCID: PMC7408229. [CrossRef]

- Xu XL, Deng SL, Lian ZX, Yu K. Estrogen Receptors in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Cells. 2021 Feb 21;10(2):459. PMID: 33669960; PMCID: PMC7924872. [CrossRef]

- Casper RF, Mitwally MF. Use of the aromatase inhibitor letrozole for ovulation induction in women with polycystic ovarian syndrome. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Dec;54(4):685-95. PMID: 22031258. [CrossRef]

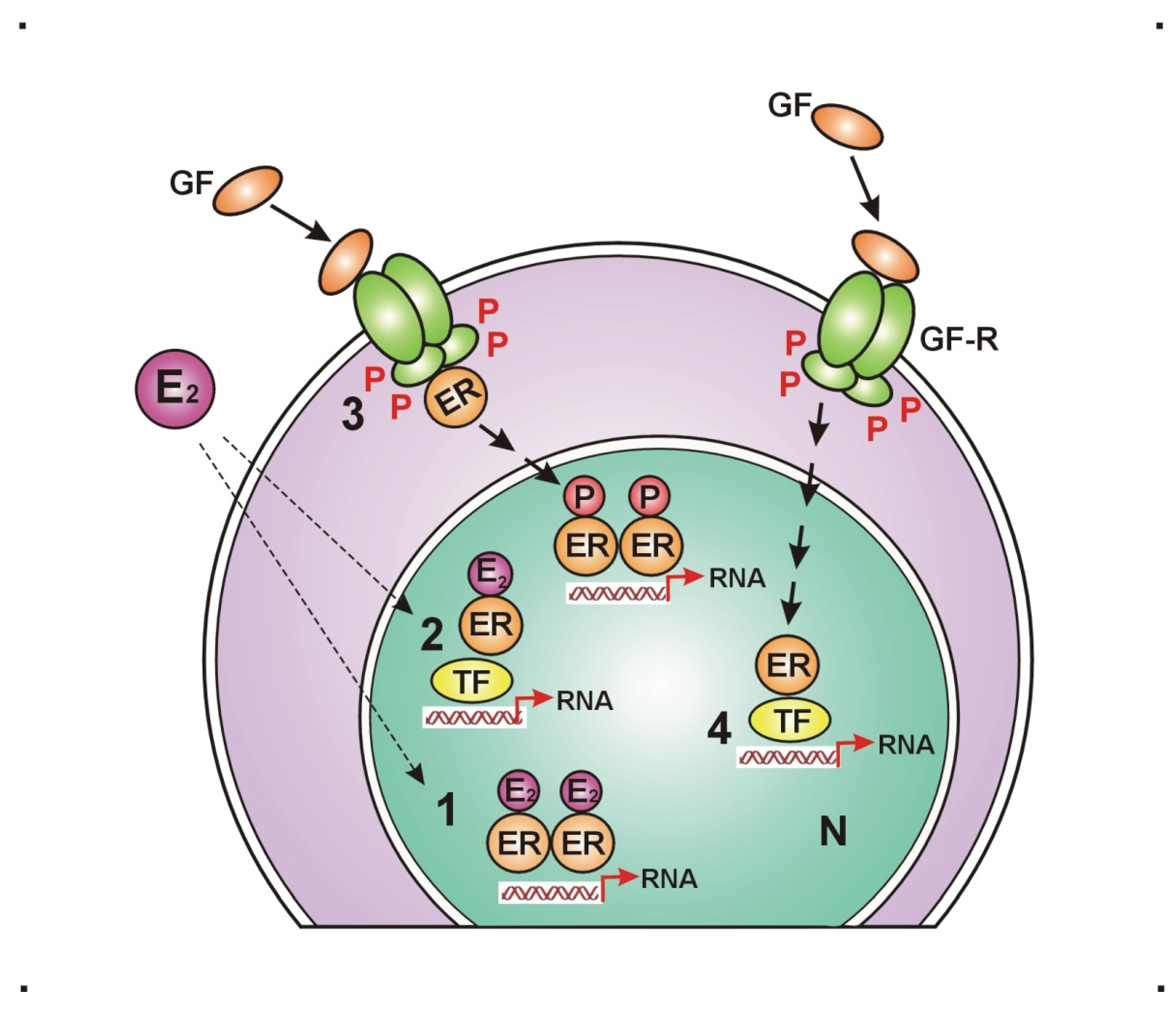

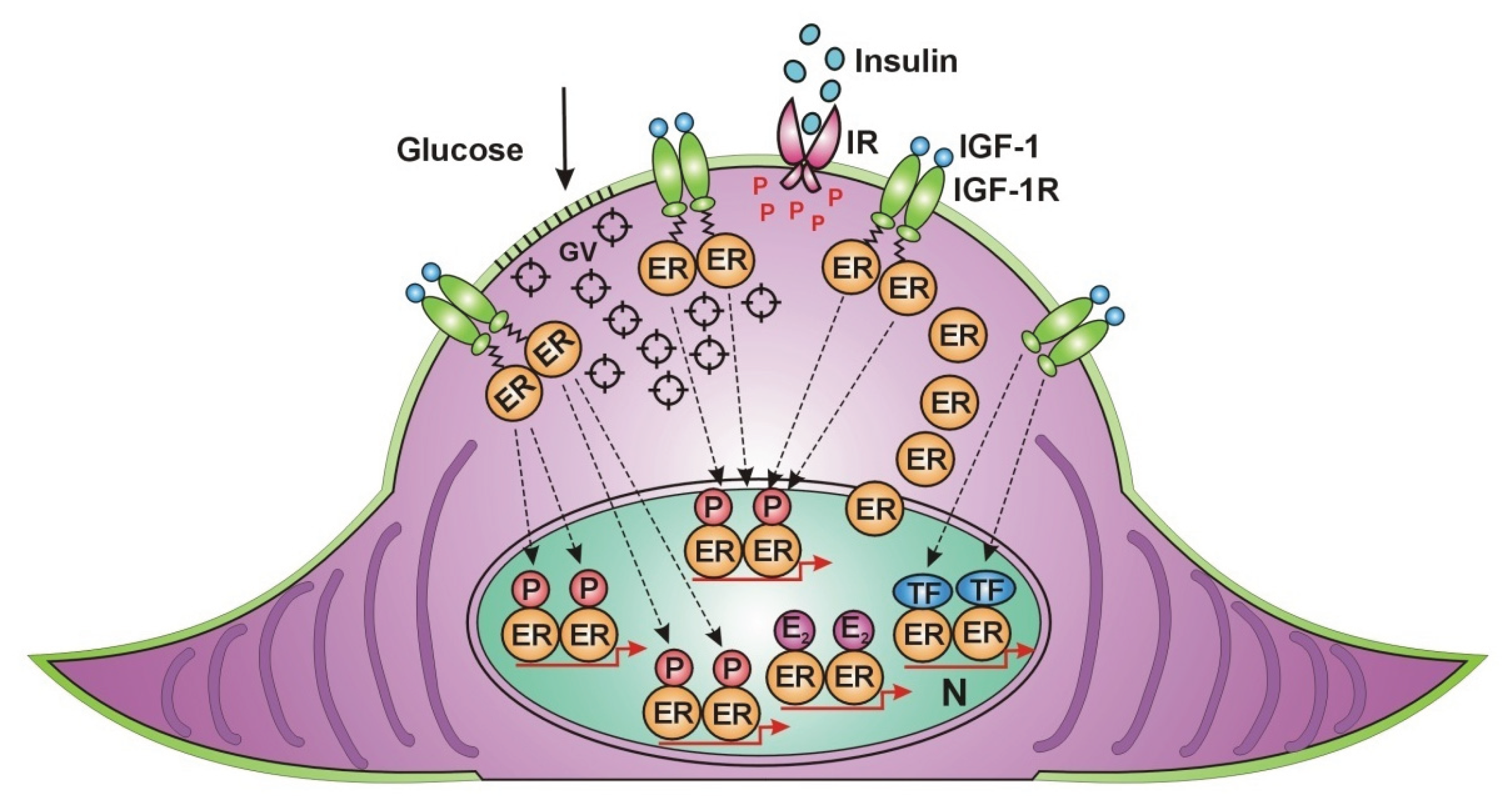

- Maggi A. Liganded and unliganded activation of estrogen receptor and hormone replacement therapies. Biochim Biophys Acta 2011; 1812(8): 1054–1060. [CrossRef]

- Curtis SW, Washburn T, Sewall C, DiAugustine R, Lindzey J, Couse JF et al. Physiological coupling of growth factor and steroid receptor signaling pathways: estrogen receptor knockout mice lack estrogen-like response to epidermal growth factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996; 93(22): 12626–30. [CrossRef]

- Levin ER. Bidirectional Signaling between the Estrogen Receptor and the Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor. Mol Endocrinol 2003; 17(3): 309–317. [CrossRef]

- Suba, Z. Amplified crosstalk between estrogen binding and GFR signaling mediated pathways of ER activation drives responses in tumors treated with endocrine disruptors. Recent Pat Anticancer Drug Discov (2018) 13(4): 428-444. [CrossRef]

- Suba Z. Rosetta Stone for Cancer Cure: Comparison of the Anticancer Capacity of Endogenous Estrogens, Synthetic Estrogens and Antiestrogens. Oncol Rev. 2023 Apr 19;17:10708. PMID: 37152665; PMCID: PMC10154579. [CrossRef]

- Suba Z. Activating Mutations of ESR1, BRCA1 and CYP19 Aromatase Genes Confer Tumor Response in Breast Cancers Treated with Antiestrogens. Recent Pat Anticancer Drug Discov. 2017;12(2):136-147. PMID: 28245776. [CrossRef]

- Barros RPA, Gustafsson JÅ. Estrogen Receptors and the Metabolic Network. Cell Metabolism (2011) 14(3): 289-299. [CrossRef]

- Tiano JP, Mauvais-Jarvis F. Importance of oestrogen receptors to preserve functional β-cell mass in diabetes. Nat Rev Endocrinol (2012) 8(6): 342-51. [CrossRef]

- Choi SB, Jang JS, Park S. Estrogen and exercise may enhance beta-cell function and mass via insulin receptor substrate 2 induction in ovariectomized diabetic rats. Endocrinology (2005) 146(11): 4786-94. [CrossRef]

- Campello RS, Fátima LA, Barreto-Andrade JN, Lucas TF, Mori RC, Porto CS, Machado UF. Estradiol-induced regulation of GLUT4 in 3T3-L1 cells: involvement of ESR1 and AKT activation. J Mol Endocrinol (2017) 59(3): 257-268. [CrossRef]

- Steiner BM, Berry DC. The Regulation of Adipose Tissue Health by Estrogens. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022 May 26;13:889923. PMID: 35721736; PMCID: PMC9204494. [CrossRef]

- Lizcano F, Guzmán G. Estrogen Deficiency and the Origin of Obesity during Menopause. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:757461. Epub 2014 Mar 6. PMID: 24734243; PMCID: PMC3964739. [CrossRef]

- Barakat R, Oakley O, Kim H, Jin J, Ko CJ. Extra-gonadal sites of estrogen biosynthesis and function. BMB Rep. 2016; 49(9): 488-96.

- Labrie F, Bélanger A, Luu-The V, et al. DHEA and the intracrine formation of androgens and estrogens in peripheral target tissues: its role during aging. Steroids. 1998; 63: 322–328.

- Bjune J-I, Strømland PP, Jersin RÅ, Mellgren G, Dankel SN. Metabolic and Epigenetic Regulation by Estrogen in Adipocytes. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2022; 13: 828780. [CrossRef]

- Dieudonné MN, Leneveu MC, Giudicelli Y, Pecquery R. Evidence for functional estrogen receptors α and β in human adipose cells: regional specificities and regulation by estrogens. Am J Physiol-Cell Physiol 2004; 286(3): C655-C661.

- Kim JH, Cho HT, Kim YJ. The role of estrogen in adipose tissue metabolism: insights into glucose homeostasis regulation. Endocr J. 2014;61(11):1055-67. Epub 2014 Aug 9. PMID: 25109846. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed F, Kamble PG, Hetty S, Fanni G, Vranic M, Sarsenbayeva A, Kristófi R, Almby K, Svensson MK, Pereira MJ, Eriksson JW, Role of Estrogen and Its Receptors in Adipose Tissue Glucose Metabolism in Pre- and Postmenopausal Women. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 2022; 107(5), e1879–e1889. [CrossRef]

- Donohoe CL, Doyle SL, Reynolds JV. Visceral adiposity, insulin resistance and cancer risk. Diabetol Metab Syndr 2011; 3: 12.

- Pelekanou V, Leclercq G. Recent insights into the effect of natural and environmental estrogens on mammary development and carcinogenesis The Int J of Develop Biol 2011; 55(7-9): 869-78.

- Wang H, Leng Y, Gong Y. Bone Marrow Fat and Hematopoiesis. Front. Endocrinol 2018; 9: 694. [CrossRef]

- Wang P, Mariman E, Renes J, Keijer J. The Secretory Function of Adipocytes in the Physiology of White Adipose Tissue. J Cell Physiol 2008; 216: 3–13.

- Monteiro R, Teixeira D, Calhau C. Estrogen signaling in metabolic inflammation. Mediators Inflamm. 2014; 2014: 615917. Epub 2014 Oct 23. PMID: 25400333; PMCID: PMC4226184. [CrossRef]

- Boon WC, Jenny D.Y. Chow JDY, Simpson ER. The Multiple Roles of Estrogens and the Enzyme Aromatase. 2010; 181: 209-32. [CrossRef]

- Clegg DJ, Brown LM, Woods SC, Benoit SC. Gonadal hormones determine sensitivity to central leptin and insulin. Diabetes. 2006; 55: 978–987.

- Combs TP, Pajvani UB, Berg AH, et al. A transgenic mouse with a deletion in the collagenous domain of adiponectin displays elevated circulating adiponectin and improved insulin sensitivity. Endocrinology. 2004; 145(1): 367–383. [CrossRef]

- Steppan CM, Bailey ST, Bhat S, et al. The hormone resistin links obesity to diabetes. Nature. 2001; 409(6818): 307–12.

- Pradhan G, Samson SL, Sun Y. Ghrelin: much more than a hunger hormone. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2013 Nov;16(6):619-24. PMID: 24100676; PMCID: PMC4049314. [CrossRef]

- Smith A, Woodside B, Abizaid A. Ghrelin and the Control of Energy Balance in Females. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022 Jul 15;13:904754. PMID: 35909536; PMCID: PMC9334675. [CrossRef]

- Suba Z. Crossroad between obesity and cancer: a defective signaling function of heavily lipid laden adipocytes (Online First). In: Crosstalk in Biological Processes. Ed: El-Esawi MA. InTechOpen, London, May 3rd 2019. [CrossRef]

- Lueprasitsakul P, Latour D, Longcope C. Aromatase activity in human adipose tissue stromal cells: effect of growth factors. Steroids. 1990 Dec;55(12):540-4. PMID: 1965238. [CrossRef]

- Armani A, Berry A, Cirulli F, Caprio M. Molecular mechanisms underlying metabolic syndrome: the expanding role of the adipocyte. FASEB J. 2017; 31(10): 4240-4255.

- De Pergola G, Silvestris F. Obesity as a major risk factor for cancer. J Obes. 2013; 2013: 291546.

- Kawai T, Autieri MV, Scalia R. Adipose tissue inflammation and metabolic dysfunction in obesity. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2021 Mar 1;320(3):C375-C391. Epub 2020 Dec 23. PMID: 33356944; PMCID: PMC8294624. [CrossRef]

- Huh JY, Park YJ, Ham M, and Kim JB. Crosstalk between Adipocytes and Immune Cells in Adipose Tissue Inflammation and Metabolic Dysregulation in Obesity. Mol Cells 2014; 37(5): 365–371.

- Purohit A, Newman SP, Reed MJ. The role of cytokines in regulating estrogen synthesis: implications for the etiology of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Research 2002; 4: 65.

- Hope MC, Unger CA, Kettering MC, Socia CE, Aladhami AK, Rice BC, Niamira DS, Wiznitzer BP, Altomare D, Cotham WE, Enos RT. Adipose Tissue Estrogen Receptor-Alpha Overexpression Ameliorates High-Fat Diet-Induced Adipose Tissue Inflammation. J Endocr Soc. 2025 Aug 19;9(10):bvaf134. PMID: 40980540; PMCID: PMC12448864. [CrossRef]

- Blum WF, Alherbish A, Alsagheir A, El Awwa A, Kaplan W, Koledova E, Savage MO. The growth hormone-insulin-like growth factor-I axis in the diagnosis and treatment of growth disorders. Endocr Connect. 2018 Jun;7(6):R212-R222. Epub 2018 May 3. PMID: 29724795; PMCID: PMC5987361. [CrossRef]

- Yakar S, Adamo ML. Insulin-like growth factor 1 physiology: lessons from mouse models. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2012 Jun;41(2):231-47, v. Epub 2012 May 15. PMID: 22682628; PMCID: PMC5488279. [CrossRef]

- Boucher J, Tseng J-H, Kahn CR. Insulin and insulin-like growth factor receptors act as ligand-specific amplitude modulators of a common pathway regulating gene. J Biol Chem 2010; 285(22): 17235-17245.

- Caizzi L, Ferrero G, Cutrupi S, Cordero F, Ballaré C, Miano V, et al. Genome-wide activity of unliganded estrogen receptor-α in breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2014; 111(13): 4892-7.

- Barthelemy J, Bogard G, Wolowczuk I. Beyond energy balance regulation: The underestimated role of adipose tissues in host defense against pathogens. Front Immunol. 2023 Mar 2;14:1083191. PMID: 36936928; PMCID: PMC10019896. [CrossRef]

- Millas I, Duarte Barros M. Estrogen receptors and their roles in the immune and respiratory systems. Anat Rec (Hoboken). 2021 Jun; 304(6): 1185-1193. Epub 2021 Apr 15. PMID: 33856123. [CrossRef]

- Bradley D, Deng T, Shantaram D, Hsueh WA. Orchestration of the Adipose Tissue Immune Landscape by Adipocytes. Annu Rev Physiol. 2024 Feb 12;86:199-223. PMID: 38345903. [CrossRef]

- Stubbins RE, Najjar K, Holcomb VB, Hong J, Núñez NP. Oestrogen alters adipocyte biology and protects female mice from adipocyte inflammation and insulin resistance. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism. 2012; 14(1): 58–66.

- Wang T, Wang J, Hu X, Huang XJ, Chen GX. Current understanding of glucose transporter 4 expression and functional mechanisms. World J Biol Chem. 2020 Nov 27;11(3):76-98. PMID: 33274014; PMCID: PMC7672939. [CrossRef]

- Warburton DE, Nicol CW, Bredin SS. Health benefits of physical activity: the evidence. CMAJ. 2006 Mar 14;174(6):801-9. PMID: 16534088; PMCID: PMC1402378. [CrossRef]

- Pereira RM, Pereira de Moura L, Muñoz VR et als. Molecular mechanisms of glucose uptake in skeletal muscle at rest and in response to exercise. 2017, Motriz Revista de Educação Física 23(spe). [CrossRef]

- Merino B, García-Arévalo M. Sexual hormones and diabetes: The impact of estradiol in pancreatic β cell. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2021; 359: 81-138. Epub 2021 Mar 16. PMID: 33832654. [CrossRef]

- Khan MZ, Zugaza JL, Torres Aleman I. The signaling landscape of insulin-like growth factor 1. J Biol Chem. 2025 Jan;301(1):108047. Epub 2024 Dec 3. PMID: 39638246; PMCID: PMC11748690. [CrossRef]

- Schwartz N, Verma A, Bivens CB, Schwartz Z, Boyan BD. Rapid steroid hormone actions via membrane receptors. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016 Sep;1863(9):2289-98. Epub 2016 Jun 22. PMID: 27288742. [CrossRef]

- Mendelsohn ME, Karas RH. Rapid progress for non-nuclear estrogen receptor signaling. J Clin Invest. 2010 Jul;120(7):2277-9. Epub 2010 Jun 23. PMID: 20577045; PMCID: PMC2898619. [CrossRef]

- Dichtel LE, Cordoba-Chacon J, Kineman RD. Growth Hormone and Insulin-Like Growth Factor 1 Regulation of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022 Jun 16;107(7):1812-1824. PMID: 35172328; PMCID: PMC9202731. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Pérez L, Guerra B, Díaz-Chico JC, Flores-Morales A. Estrogens regulate the hepatic effects of growth hormone, a hormonal interplay with multiple fates. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2013 Jun 3;4:66. PMID: 23761784; PMCID: PMC3670000. [CrossRef]

- Chaturantabut S, Shwartz A, Evason KJ, Cox AG, Labella K, Schepers AG, Yang S, Acuña M, Houvras Y, Mancio-Silva L, Romano S, Gorelick DA, Cohen DE, Zon LI, Bhatia SN, North TE, Goessling W. Estrogen Activation of G-Protein-Coupled Estrogen Receptor 1 Regulates Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase and mTOR Signaling to Promote Liver Growth in Zebrafish and Proliferation of Human Hepatocytes. Gastroenterology. 2019 May;156(6):1788-1804.e13. Epub 2019 Jan 12. PMID: 30641053; PMCID: PMC6532055. [CrossRef]

- Faulds MH, Zhao C, Dahlman-Wright K, Gustafsson JÅ. The diversity of sex steroid action: regulation of metabolism by estrogen signaling. J Endocrinol. 2012 Jan;212(1):3-12. Epub 2011 Apr 21. PMID: 21511884. [CrossRef]

- Yakar S, Adamo ML. Insulin-like growth factor 1 physiology: lessons from mouse models. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2012 Jun;41(2):231-47, v. Epub 2012 May 15. PMID: 22682628; PMCID: PMC5488279. [CrossRef]

- Kahlert S, Nuedling S, van Eickels M, Vetter H, Meyer R, Grohe C. Estrogen receptor alpha rapidly activates the IGF-1 receptor pathway. J Biol Chem. 2000 Jun 16;275(24):18447-53. PMID: 10749889. [CrossRef]

- Flores B, Trivedi HD, Robson SC, Bonder A. Hemostasis, bleeding and thrombosis in liver disease. J Transl Sci. 2017 May;3(3):10.15761/JTS.1000182. Epub 2017 Mar 4. PMID: 30221012; PMCID: PMC6136435. [CrossRef]

- Muciño-Bermejo J, Carrillo-Esper R, Méndez-Sánchez N, Uribe M. Thrombosis and hemorrhage in the critically ill cirrhotic patients: five years retrospective prevalence study. Ann Hepatol. 2015 Jan-Feb;14(1):93-8. PMID: 25536646.

- Kostallari E, Schwabe RF, Guillot A. Inflammation and immunity in liver homeostasis and disease: a nexus of hepatocytes, nonparenchymal cells and immune cells. Cell Mol Immunol. 2025 Oct;22(10):1205-1225. Epub 2025 Jul 1. PMID: 40595432; PMCID: PMC12480768. [CrossRef]

- Bryzgalova G, Lundholm L, Portwood N, Gustafsson JA, Khan A, Efendic S, Dahlman-Wright K. Mechanisms of antidiabetogenic and body weight-lowering effects of estrogen in high-fat diet-fed mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008 Oct;295(4):E904-12. Epub 2008 Aug 12. PMID: 18697913; PMCID: PMC2575902. [CrossRef]

- Hamden, K., Carreau, S., Ellouz, F. et al. Protective effect of 17β-estradiol on oxidative stress and liver dysfunction in aged male rats. J. Physiol. Biochem. 63, 195–201 (2007). [CrossRef]

- Anagnostis P, Stevenson JC, Crook D, Johnston DG, Godsland IF. Effects of menopause, gender and age on lipids and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol subfractions. Maturitas. 2015 May;81(1):62-8. Epub 2015 Mar 6. PMID: 25804951. [CrossRef]

- Anagnostis P, Lambrinoudaki I, Stevenson JC, Goulis DG. Menopause-associated risk of cardiovascular disease. Endocr Connect. 2022 Apr 22;11(4):e210537. PMID: 35258483; PMCID: PMC9066596. [CrossRef]

- Cetin EG, Demir N, Sen I. The Relationship between Insulin Resistance and Liver Damage in non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Patients. Sisli Etfal Hastan Tip Bul. 2020 Dec 11;54(4):411-415. PMID: 33364879; PMCID: PMC7751232. [CrossRef]

- Talamantes S, Lisjak M, Gilglioni EH, Llamoza-Torres CJ, Ramos-Molina B, Gurzov EN. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and diabetes mellitus as growing aetiologies of hepatocellular carcinoma. JHEP Rep. 2023 Jun 9;5(9):100811. PMID: 37575883; PMCID: PMC10413159. [CrossRef]

- Goel M, Mittal A, Jain VR, Bharadwaj A, Modi S, Ahuja G, Jain A, Kumar K. Integrative Functions of the Hypothalamus: Linking Cognition, Emotion and Physiology for Well-being and Adaptability. Ann Neurosci. 2025 Apr;32(2):128-142. Epub 2024 Jun 12. PMID: 39544638; PMCID: PMC11559822. [CrossRef]

- Zeng Y, Rong R, You M, Zhu P, Zhang J, Xia X. Light-eye-body axis: exploring the network from retinal illumination to systemic regulation. Theranostics. 2025 Jan 2;15(4):1496-1523. PMID: 39816683; PMCID: PMC11729557. [CrossRef]

- Alvord VM, Kantra EJ, Pendergast JS. Estrogens and the circadian system. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2022 Jun;126:56-65. Epub 2021 May 9. PMID: 33975754; PMCID: PMC8573061. [CrossRef]

- Rettberg JR, Yao J, Brinton RD. Estrogen: a master regulator of bioenergetic systems in the brain and body. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2014 Jan;35(1):8-30. Epub 2013 Aug 29. PMID: 23994581; PMCID: PMC4024050. [CrossRef]

- Hara Y, Waters EM, McEwen BS, Morrison JH. Estrogen Effects on Cognitive and Synaptic Health Over the Lifecourse. Physiol Rev. 2015 Jul;95(3):785-807. PMID: 26109339; PMCID: PMC4491541. [CrossRef]

- Acevedo-Rodriguez A, Kauffman AS, Cherrington BD, Borges CS, Roepke TA, Laconi M. Emerging insights into hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis regulation and interaction with stress signaling. J Neuroendocrinol. 2018 Oct;30(10):e12590. Epub 2018 Aug 7. PMID: 29524268; PMCID: PMC6129417. [CrossRef]

- Taneja V. Sex Hormones Determine Immune Response. Front Immunol. 2018 Aug 27;9:1931. PMID: 30210492; PMCID: PMC6119719. [CrossRef]

- Torres Irizarry VC, Jiang Y, He Y, Xu P. Hypothalamic Estrogen Signaling and Adipose Tissue Metabolism in Energy Homeostasis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022 Jun 9;13:898139. PMID: 35757435; PMCID: PMC9218066. [CrossRef]

- Rossi MA. Control of energy homeostasis by the lateral hypothalamic area. Trends Neurosci. 2023 Sep;46(9):738-749. Epub 2023 Jun 22. PMID: 37353461; PMCID: PMC10524917. [CrossRef]

- Sun X, Liu B, Yuan Y, Rong Y, Pang R, Li Q. Neural and hormonal mechanisms of appetite regulation during eating. Front Nutr. 2025 Mar 24;12:1484827. PMID: 40201582; PMCID: PMC11977392. [CrossRef]

- Butera PC. Estradiol and the control of food intake. Physiol Behav. 2010 Feb 9;99(2):175-80. Epub 2009 Jun 23. PMID: 19555704; PMCID: PMC2813989. [CrossRef]

- Islami F, Marlow EC, Thomson B, McCullough ML, Rumgay H, Gapstur SM, Patel AV, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A. Proportion and number of cancer cases and deaths attributable to potentially modifiable risk factors in the United States, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024 Sep-Oct;74(5):405-432. Epub 2024 Jul 11. PMID: 38990124. [CrossRef]

- IARC Working Group. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, Volume 100E: Personal Habits and Indoor Combustions. IARC Press; 2012.

- Cena H, Fonte ML, Turconi G. Relationship between smoking and metabolic syndrome. Nutr Rev. 2011 Dec;69(12):745-53. Erratum in: Nutr Rev. 2013 Apr;71(4):255. PMID: 22133198. [CrossRef]

- Artese A, Stamford BA, Moffatt RJ. Cigarette Smoking: An Accessory to the Development of Insulin Resistance. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2017 Aug 23;13(6):602-605. PMID: 31662726; PMCID: PMC6796230. [CrossRef]

- Barbieri RL, Gochberg J, Ryan KJ. Nicotine, cotinine, and anabasine inhibit aromatase in human trophoblast in vitro. J Clin Invest. 1986 Jun;77(6):1727-33. PMID: 3711333; PMCID: PMC370526. [CrossRef]

- Biegon A, Alia-Klein N, Fowler JS. Potential contribution of aromatase inhibition to the effects of nicotine and related compounds on the brain. Front Pharmacol. 2012 Nov 6;3:185. PMID: 23133418; PMCID: PMC3490106. [CrossRef]

- Wan Q, Liu Y, Guan Q, Gao L, Lee KO, Zhao J. Ethanol feeding impairs insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in isolated rat skeletal muscle: role of Gs alpha and cAMP. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005 Aug;29(8):1450-6. PMID: 16131853. [CrossRef]

- Wannamethee SG, Shaper AG, Perry IJ, Alberti KG. Alcohol consumption and the incidence of type II diabetes. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2002 Jul;56(7):542-8. PMID: 12080164; PMCID: PMC1732195. [CrossRef]

- Johnson C.H., Golla J.P., Dioletis E., Singh S., Ishii M., Charkoftaki G., Thompson D.C., Vasiliou V. Molecular Mechanisms of Alcohol-Induced Colorectal Carcinogenesis. Cancers. 2021;13:4404. [CrossRef]

- Orywal K., Szmitkowski M. Alcohol Dehydrogenase and Aldehyde Dehydrogenase in Malignant Neoplasms. Clin. Exp. Med. 2017;17:131–139. [CrossRef]

- Rachdaoui N, Sarkar DK. Effects of alcohol on the endocrine system. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2013 Sep;42(3):593-615. PMID: 24011889; PMCID: PMC3767933. [CrossRef]

- Fanfarillo F, Caronti B, Lucarelli M, Francati S, Tarani L, Ceccanti M, Piccioni MG, Verdone L, Caserta M, Venditti S, Ferraguti G, Fiore M. Alcohol Consumption and Breast and Ovarian Cancer Development: Molecular Pathways and Mechanisms. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2024 Dec 20;46(12):14438-14452. PMID: 39727994; PMCID: PMC11674816. [CrossRef]

- Chen JR, Lazarenko OP, Haley RL, Blackburn ML, Badger TM, Ronis MJ. Ethanol impairs estrogen receptor signaling resulting in accelerated activation of senescence pathways, whereas estradiol attenuates the effects of ethanol in osteoblasts. J Bone Miner Res. 2009 Feb;24(2):221-30. PMID: 18847333; PMCID: PMC3276356. [CrossRef]

- Lauby-Secretan B, Scoccianti C, Loomis D, Grosse Y, Bianchini F, Straif K; International Agency for Research on Cancer Handbook Working Group. Body Fatness and Cancer--Viewpoint of the IARC Working Group. N Engl J Med. 2016 Aug 25;375(8):794-8. PMID: 27557308; PMCID: PMC6754861. [CrossRef]

- Anderson GL, Neuhouser ML. Obesity and the risk for premenopausal and postmenopausal breast cancer. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2012 Apr;5(4):515-21. Epub 2012 Mar 5. PMID: 22392012. [CrossRef]

- Suba Z. Circulatory estrogen level protects against breast cancer in obese women. Recent Pat Anticancer Drug Discov. 2013 May;8(2):154-67. PMID: 23061769; PMCID: PMC3636519. [CrossRef]

- Gong D, Lai WF. Dietary patterns and type 2 diabetes: A narrative review. Nutrition. 2025 Dec;140:112905. Epub 2025 Jul 8. PMID: 40749645. [CrossRef]

- Papadimitriou N, Markozannes G, Kanellopoulou A, Critselis E, Alhardan S, Karafousia V, Kasimis JC, Katsaraki C, Papadopoulou A, Zografou M, Lopez DS, Chan DSM, Kyrgiou M, Ntzani E, Cross AJ, Marrone MT, Platz EA, Gunter MJ, Tsilidis KK. An umbrella review of the evidence associating diet and cancer risk at 11 anatomical sites. Nat Commun. 2021 Jul 28;12(1):4579. PMID: 34321471; PMCID: PMC8319326. [CrossRef]

- Park JH, Moon JH, Kim HJ, Kong MH, Oh YH. Sedentary Lifestyle: Overview of Updated Evidence of Potential Health Risks. Korean J Fam Med. 2020 Nov;41(6):365-373. Epub 2020 Nov 19. PMID: 33242381; PMCID: PMC7700832. [CrossRef]

- McTiernan A, Friedenreich CM, Katzmarzyk PT, Powell KE, Macko R, Buchner D, Pescatello LS, Bloodgood B, Tennant B, Vaux-Bjerke A, George SM, Troiano RP, Piercy KL; 2018 PHYSICAL ACTIVITY GUIDELINES ADVISORY COMMITTEE*. Physical Activity in Cancer Prevention and Survival: A Systematic Review. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019 Jun;51(6):1252-1261. PMID: 31095082; PMCID: PMC6527123. [CrossRef]

- Sjøberg KA, Frøsig C, Kjøbsted R, Sylow L, Kleinert M, Betik AC, Shaw CS, Kiens B, Wojtaszewski JFP, Rattigan S, Richter EA, McConell GK. Exercise Increases Human Skeletal Muscle Insulin Sensitivity via Coordinated Increases in Microvascular Perfusion and Molecular Signaling. Diabetes. 2017 Jun;66(6):1501-1510. Epub 2017 Mar 14. PMID: 28292969. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).