1. Introduction

The automatic generation of image captions represents a dynamic intersection of computer vision and natural language processing, aiming to produce coherent, human like descriptions of visual content [

1]. Although this technology has traditionally been applied in domains such as assistive technologies, social networks, and autonomous systems, its relevance to Earth observation and environmental monitoring is rapidly increasing. In particular, image change captioning the task of describing differences between pairs or sequences of multi-temporal remote sensing images offers a powerful framework for understanding land cover dynamics over time [

2]. By translating complex spectral and spatial changes into descriptive narratives, automatic captioning not only makes raw satellite data more interpretable, but also captures the semantic essence of environmental transformations.

In the context of land cover monitoring using multi-temporal remote sensing, a central analytical focus is the identification of change types. These refer to the nature and trajectory of landscape transformations over time, such as deforestation, urban expansion, agricultural intensification, fluctuations in water bodies, or vegetation regrowth. Rather than mere spectral variations, these changes reflect substantive shifts in land use and ecological processes, with profound environmental, social, and economic implications. For an automated image captioning system, effectively capturing and articulating these change types in natural language is critical.

A further critical dimension of this task lies in the semantic relationships between objects when characterizing land cover changes, as depicted in satellite imagery. Transformations observed in multi-temporal images frequently involve multiple interdependent entities; for instance, the conversion of forest to agricultural land entails not only the loss of vegetation but also the emergence of cultivated landscapes. When captioning the same image pair, human annotators often emphasize distinct aspects of these relationships: some may prioritize the decline in tree cover, others the expansion of cropland, and still others the broader ecological or socio-economic consequences. This variability underscores both the richness and the inherent ambiguity of natural language descriptions of change. Consequently, automated captioning systems must be designed to account for not only object level changes, but also the relational and contextual nuances that shape human interpretations of environmental dynamics.

The evaluation of the outputs of automated image captioning systems poses substantial challenges, especially in the domain of land cover change detection. Although generated captions must accurately depict complex spatial and temporal transformations, human interpretations of the same image pair often exhibit significant variability in both wording and emphasis. This inconsistency undermines the reliability of traditional evaluation metrics, which typically depend on surface level lexical matching and may overlook semantically valid descriptions phrased differently. As a result, the selection of appropriate evaluation strategies emerges as a pivotal consideration in the design and assessment of captioning systems for multi-temporal remote sensing applications.

Recent works have explored the task of multi-temporal image captioning from multiple methodological perspectives. The Chg2Cap [

4] framework proposed a structured three-stage network architecture composed of a Siamese CNN based feature extractor, an attentive encoder incorporating a hierarchical self attention mechanism, and a transformer based caption generator that decodes the learned visual embeddings into coherent textual descriptions.

Building upon this foundation, RSICCformer [

6] advanced the field by introducing a fully transformer-based architecture specifically tailored for remote sensing change captioning. The network is composed of three principal components: a CNN-based feature extractor, a dual branch transformer encoder, and a transformer-based caption decoder that synthesizes these discriminative representations into textual descriptions of the detected differences.

More recently, SAT-Cap [

5] proposed a streamlined yet effective framework that integrates spatial and channel level attention mechanisms for change aware caption generation. The architecture comprises three key components: a spatial channel attention encoder that jointly captures spatial distributions and inter-channel dependencies to refine feature representations, a difference guided fusion module that employs cosine similarity for efficient information integration between multi-temporal features, and a caption decoder that translates the fused representation into natural language descriptions of scene evolution.

Despite these advances, existing state of the art methods remain inherently constrained by dataset specific vocabularies and narrowly scoped pretraining objectives. Since these models learn linguistic representations solely from captions within a limited corpus (e.g., LEVIR-CC), their lexical and semantic spaces are tightly coupled to the dataset distribution, hindering generalization to unseen geographic regions, environmental contexts, or descriptive styles. This vocabulary confinement often results in repetitive or overly template-based caption generation, reducing the capacity to adapt to novel scenes or user-specific interpretive needs.

Moreover, these models operate exclusively in a vision only regime, lacking the ability to integrate external textual information or dynamic linguistic guidance during inference. In contrast, recent advances in multi-modal learning enable architectures capable of processing both text and image inputs [

3], where the textual component can serve as an adaptive prompt to steer the model’s attention and descriptive intent. Such prompt driven conditioning allows the captioning process to be modulated according to analytical goals such as emphasizing urban growth, vegetation loss, or hydrological variation—thereby moving beyond static, dataset locked vocabularies toward context aware and instruction following generation.

To address these limitations, our work introduces a multi-modal Vision Language Transformer architecture that integrates both visual and textual modalities within a unified representation space. Specifically, our approach combines a Vision Transformer (ViT) for spatial representation learning, a Large Language Model (LLM) for high level linguistic reasoning, and Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) for parameter efficient fine-tuning. In contrast to vision only methods, our model processes both text and image inputs, enabling a bidirectional flow of semantic information between modalities. This design allows for dynamic prompt engineering, where textual cues can guide or condition visual interpretation, thereby enhancing adaptability and interpretability. Leveraging universal pretrained vocabularies and cross modal feature alignment, our model generalizes more effectively across domains and achieves state of the art performance on the LEVIR-CC dataset [

6], establishing a robust framework for scalable and semantically rich change captioning in remote sensing.

On the other hand, in this work, we conduct a critical analysis of traditional caption evaluation metrics, demonstrating their limitations in dual task scenarios where both change description and stability recognition must be simultaneously assessed. Conventional lexical similarity measures, such as BLEU or ROUGE, often misrepresent performance by penalizing semantically equivalent yet lexically distinct captions, while failing to capture the categorical nature of no change predictions. To address these shortcomings, we introduce a more principled evaluation strategy that decouples the assessment of descriptive fidelity from change detection accuracy, later recombining them through the CCS formulation. This hybrid metric provides a unified and semantically grounded measure of model consistency and robustness across both subtasks, offering a fairer and more informative basis for comparative analysis.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 presents the proposed multi-modal Vision Language Transformer Architecture, detailing its visual and linguistic components, the integration of LoRA for efficient fine-tuning, and the mathematical formulation underlying each module.

Section 3 describes the LEVIR-CC dataset, outlining its structure, preprocessing, and relevance for multi-temporal remote sensing captioning.

Section 4 introduces a critical analysis of conventional captioning metrics and proposes the new Complementary Consistency Score (CCS) framework, which provides a unified and semantically grounded evaluation strategy for both

change and

no change samples.

Section 5 reports and discusses the experimental results, including quantitative comparisons with state of the art methods and an examination of how multi-modal conditioning enhances descriptive precision and model generalization. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the paper by summarizing key findings, discussing their broader implications for multi-modal understanding in remote sensing, and outlining directions for future research.

2. Materials and Methods

To effectively address the task of monitoring land cover changes through multi-temporal remote sensing image captioning, we design a hybrid multi-modal framework that integrates Vision Transformers (ViTs), Large Language Models (LLMs), and Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA). The goal of this framework is to jointly process sequences of remote sensing images and textual inputs, enabling the generation of descriptive captions that capture both spatial and temporal transformations of land cover.

The proposed architecture leverages the Vision Transformer (ViT) as the primary visual backbone. ViTs are particularly well suited for remote sensing applications due to their ability to capture long range dependencies and subtle spatial patterns [

7]. In this framework, input images are decomposed into fixed-size patches, projected into an embedding space, and subsequently processed by stacked Transformer encoder layers [

8]. The use of multi-head self attention enables the model to learn complex spatial relationships, while positional encodings preserve structural and temporal consistency across multi-temporal imagery. Specific architectural elements include patch embedding via 2D convolutional projection, repeated Transformer blocks composed of attention and feed forward sublayers, and the integration of rotary positional embeddings (RoPE) within the attention mechanism to inject spatial context into the query and key projections [

9]. Furthermore, attention masking strategies are applied to control modality specific interactions: a

BlockDiagonalMask is employed within the Vision Encoder to restrict attention computations to visual tokens, while a

BlockDiagonalCausalMask is used in the final multi-modal Transformer blocks to enable autoregressive decoding of text conditioned on both image and text embeddings.

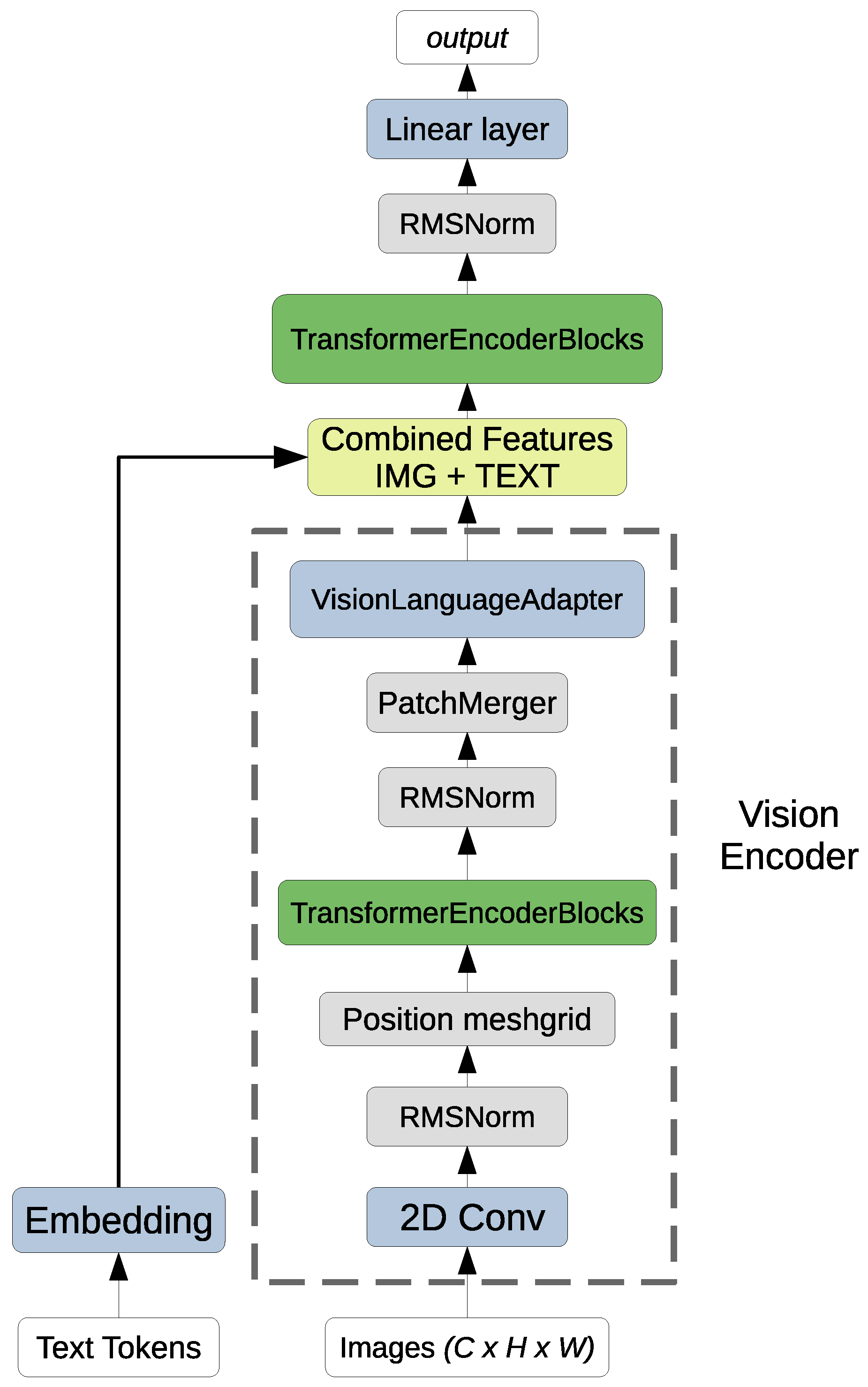

To bridge the gap between visual and textual modalities, a pre-trained multi-modal Large Language Model (LLM) is employed. Multi-modal alignment between vision and language representations follows the cross attention fusion paradigm similar to [

10], allowing textual queries to dynamically modulate visual embeddings. However, directly fine-tuning such models with billions of parameters requires substantial computational resources, often demanding high memory GPUs or distributed multi-node systems. To mitigate these hardware and energy constraints while maintaining model adaptability, we apply Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA). LoRA introduces trainable low-rank matrices into specific linear and convolutional layers of the model, while the original pretrained weights remain frozen. This approach significantly reduces the number of trainable parameters and memory footprint, allowing efficient fine-tuning on standard hardware without compromising performance.

This section is organized into three subsections. First,

Section 2.1 introduces the proposed vision language architecture, which establishes the foundation for multi-modal understanding and cross modal representation learning. Next,

Section 2.5 presents the Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) approach, a parameter efficient fine-tuning (PEFT) technique designed to adapt large pre-trained models with minimal computational overhead. Finally,

Section 2.6 describes the integration of LoRA modules into the vision language framework, illustrating how low-rank adaptations are applied to both linear and convolutional layers to enhance model efficiency and adaptability. Together, these components constitute a unified and scalable framework for multi-temporal remote sensing image captioning, enabling accurate and efficient monitoring of land cover changes over time.

2.1. Multi-Modal Vision Language Transformer Architecture

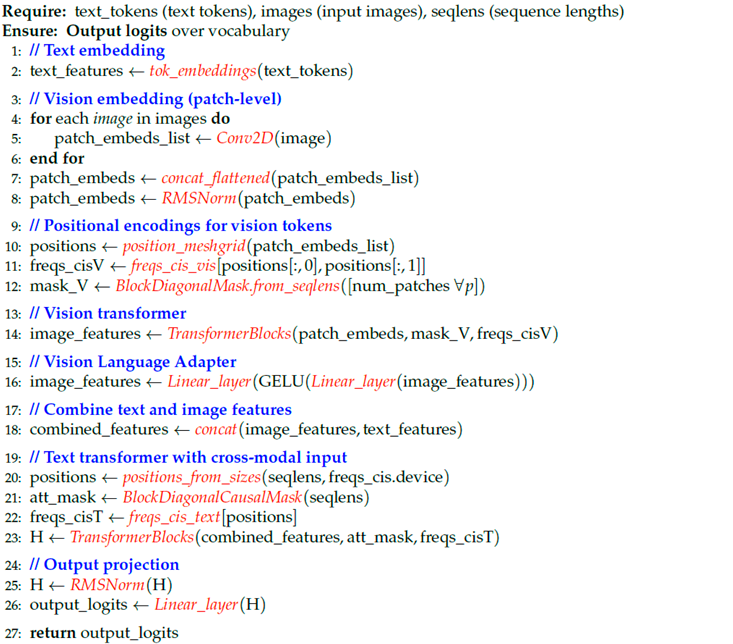

The multi-modal transformer architecture integrates textual and visual information through a unified sequence based design, enabling joint reasoning across both modalities. The complete flow is illustrated in

Figure 1. The model is composed of two primary processing streams one for text tokens and another for images which are fused into a shared Transformer backbone.

2.2. Vision Processing Branch (Vision Encoder)

The Vision Processing Branch, is designed to extract discriminative spatiotemporal representations from multi-temporal remote sensing imagery. Formally, the multi-temporal image sequence is denoted as:

Where

T is a sequence of co-registered images acquired at different times over the same geographic region, where

C is the number of spectral channels and

are the spatial dimensions.

2.2.1. Conv2D.

Each image

is first decomposed into a set of non-overlapping patches through a two dimensional convolutional operation with kernel and stride equal to the patch size

p. This operation can be formalized as:

where

represents the patch embeddings,

is the number of image patches, and

D is the embedding dimension of the projected feature space. Each row of

corresponds to the latent representation of a local spatial patch.

A root mean square normalization (RMSNorm) is applied to each embedding vector to stabilize the training dynamics:

2.2.2. Transformer Encoder Blocks (Visual Encoder)

The normalized embeddings

are subsequently processed by a sequence of Transformer encoder layers, each composed of a multihead self attention (MHSA) mechanism and a feed forward network (FFN) with residual connections:

Here,

denotes a block diagonal attention mask (

BlockDiagonalMask) that constrains self-attention computations within the spatial domain of each temporal image, preventing cross image interference during encoding and

is the number of visual Transformer layers.

1. MHSA: Linear projections and attention computation.

For a single attention layer with

H heads and per head dimension

(so

), the query, key, and value projections are

These are reshaped into

H heads:

Attention is computed per head (optionally with RoPE applied to

Q and

K):

The head outputs are concatenated and projected:

Finally, residual is applied:

The attention sublayer relies on the set of linear weight matrices:

each of which is a natural target for parameter efficient adapters.

2. Feed Forward Network (FFN).

The Feed-Forward Network (FFN) extends the standard Transformer formulation by introducing an additional gated projection branch. It operates position wise on each token embedding and employs three linear projections, each associated with its own bias term. The computation is defined as:

Here,

denotes a non linear activation function (e.g., SiLU), and ⊙ represents element wise multiplication and

is the intermediate (hidden) dimension in the FFN sublayer.

Intuitively, the first and third projections ( and ) generate two complementary feature spaces: one transformed through a non linear activation and the other preserving linear structure. Their element wise interaction gates the hidden representation before it is projected back to the model dimension through the output layer . This gated design improves the representational flexibility of the FFN while maintaining computational efficiency.

A residual connection is applied in the same way as in the Multi-Head Self Attention (MHSA) sublayer:

The complete set of trainable parameters in the FFN sublayer is given by:

Optionally, a

Patch Merger module can be applied to aggregate neighboring patch embeddings, reducing spatial redundancy while preserving high level semantics. The merged feature representation is defined as:

where

and

.

2.3. Vision Language Adapter

Finally, each encoded temporal representation

is projected into a unified multi-modal embedding space through a Vision Language Adapter

, producing

where

and

are learnable linear projections, and

denotes the Gaussian Error Linear Unit activation function. This adapter maps the temporal visual embeddings into the multi-modal space while introducing a lightweight non linearity for cross-modal fusion.

The Vision Language Adapter sublayer relies on the set of linear weight matrices:

2.4. Multi-modal Fusion and Transformer Output

Following the independent encoding of visual and textual modalities, the model performs a fusion step that jointly embeds spatial temporal image representations and linguistic tokens within a shared feature space. Let the textual input sequence be denoted as:

where each token

is drawn from a vocabulary

of size

and

L is the length of tokenized caption.

2.4.1. Embedding.

Each token

is mapped to a continuous embedding vector via a trainable embedding matrix

:

2.4.2. Combined Features.

Let

denote the encoded visual features from the Vision Encoder (cf.

Section 2.2), where each

corresponds to one temporal observation. The multi-modal token sequence is formed by concatenating visual and textual representations:

2.4.3. Transformer Encoder Blocks.

The combined multi-modal sequence

, containing

S features tokens of dimension

D, is processed by a stack of

Transformer blocks that enable joint reasoning across modalities. Each block includes Multi-Head Self Attention (MHSA), a Feed Forward Network (FFN), and residual connections with normalization, applied as described in the previous

Section 2.2.2:

Here,

is a

BlockDiagonalCausalMask that enforces autoregressive dependencies within the textual sequence while preserving bidirectional access to preceding visual tokens and

is the number of multi-modal transformer blocks. Intuitively, vision tokens can condition language generation freely, while text tokens cannot attend to future words. Formally:

where

for text tokens or

j is a visual token.

2.4.4. Normalization (RMSNorm) and Output Projection (Linear Layer).

After the final Transformer layer, a root mean square normalization is applied to stabilize activations:

The normalized multi-modal representation

is then projected into the vocabulary space via a linear transformation:

Each row

corresponds to the unnormalized logits for the

i-th token over all possible vocabulary elements. During training, these logits are passed through a softmax function to produce the conditional distribution:

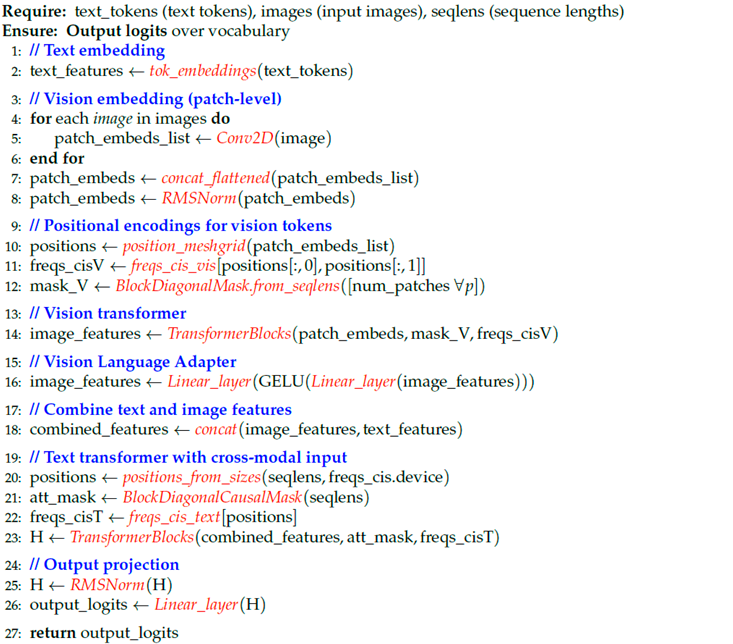

The following pseudocode (see Algorithm 1) illustrates the processing flow within the vision language transformer architecture. It is intended for clarity and conceptual understanding, and is written in a Python like style rather than rigorous mathematical notation. Several helper functions are used in the pseudo code:

position_meshgrid generates 2D coordinates for visual patches,

freqs_cis_vis and

freqs_cis_text compute rotary positional embeddings (RoPE) for vision and text tokens, respectively, and

positions_from_sizes produces a flat index sequence corresponding to token positions for masking and embedding lookup.

|

Algorithm 1 multi-modal Vision Language Forward Pass |

|

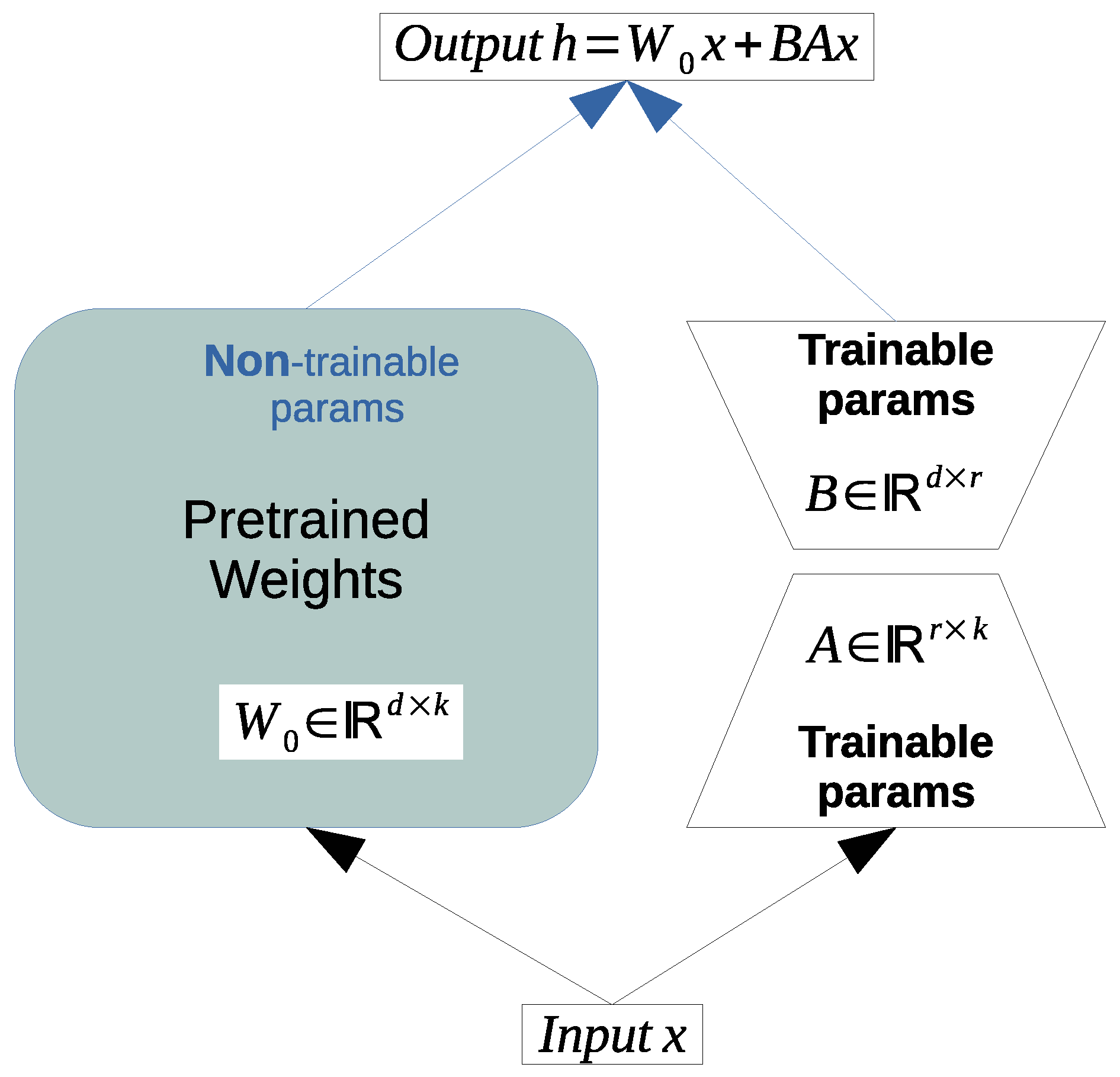

2.5. PEFT: Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA)

Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) [

18] is a parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT) approach designed to adapt large pre-trained models to downstream tasks while minimizing the number of trainable parameters. Neural networks, particularly those composed of dense or convolutional layers, rely heavily on large weight matrices that are typically full rank. Empirical studies [

16] have shown that large language models possess a low

intrinsic dimension, enabling effective learning even when projected into a lower dimensional subspace. Building on this insight, [

17] hypothesized that the weight updates required for task adaptation also lie in a low rank subspace.

Formally, let

denote a pre-trained weight matrix of a linear layer. LoRA constrains its update by decomposing the adjustment into two low rank matrices

and

, with rank

, and introducing a scaling factor

to control the magnitude of the update:

Typically, the scaling factor is normalized by the rank r, such that the effective scaling becomes . This normalization ensures that increasing the rank r and consequently the number of trainable parameters does not disproportionately amplify the magnitude of the LoRA update.

During fine-tuning, the original weights

remain frozen, and only the parameters of

A and

B are optimized. For an input vector

x, the adapted forward pass is computed as:

where the low rank term

captures task specific adaptation applied to the frozen base model. This formulation significantly reduces the computational and memory overhead compared to full fine-tuning while maintaining sufficient expressive capacity.

LoRA for 2D Convolutional Layers

LoRA extends to 2D convolutions by interpreting them as linear operations over local patches. Let

where

is the convolutional kernel and

X is the input feature map. After applying the

im2col operation, the convolution is reformulated as a matrix multiplication:

where

is the unfolded input (each column represents a flattened patch of

X), and

is the reshaped kernel (each row corresponds to an output channel). The output of the convolution in matrix form is:

Low-Rank Adaptation

LoRA introduces a low rank update to the kernel:

where:

projects the input patches to a low dimensional space,

projects back to the output space,

is the rank of the decomposition,

is a scaling factor.

The adapted forward pass becomes:

where only A and B are trained, and remains frozen. After computation, reshapes to .

An overview of this process, applicable to both linear and convolutional layers, is illustrated in

Figure 2.

2.6. Integration of LoRA Modules into the Multi-Modal Architectures

Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) modules are integrated throughout the multi-modal Vision Language Transformer to enable

parameter efficient fine-tuning without updating the full set of pretrained weights. Following the architectural flow described in

Section 2.2,

Section 2.3 and

Section 2.4, LoRA can be inserted into all major

linear and

convolutional components that govern both the visual and textual processing branches.

2.6.1. LoRA in the Vision Processing Branch

In the visual encoder, LoRA is first applied to the convolutional layer responsible for patch embedding (see Equation 2). Given the convolutional kernel

, LoRA introduces a pair of learnable low rank matrices

and

, such that the adapted convolutional weights become:

This adaptation enables the visual front end to specialize for domain specific image distributions while maintaining the frozen backbone parameters.

Each Transformer encoder block within the vision branch (

Section 2.2.2) is further augmented with LoRA modules in both its

Multi-Head Self Attention (MHSA) and

Feed Forward Network (FFN) sublayers. For attention, LoRA is applied to the query, key, value, and output projection matrices (see Equation

12):

each reparameterized as:

These low rank adapters allow each attention head to adapt its representation for specific downstream tasks without retraining the full attention block.

Similarly, LoRA is integrated into the

Feed Forward Network, specifically in the three linear transformations (see Equation

16):

producing LoRA augmented weights:

This configuration enhances the expressive power of the FFN while preserving computational efficiency.

2.6.2. LoRA in the Vision Language Adapter

The

Vision Language Adapter (

Section 2.3), which bridges the vision encoder and multi-modal Transformer, is also equipped with LoRA modules. Given its two linear mappings

and

(see Equation

20), the low rank updates are defined as:

where

and

. These updates allow the adapter to refine how visual features are projected into the shared multi-modal embedding space, improving cross modal alignment with minimal additional parameters.

2.6.3. LoRA in the Transformer

After the fusion stage (

Section 2.4), LoRA is also integrated into the

multi-modal Transformer backbone that jointly processes visual and textual tokens. All linear transformations within its MHSA and FFN sublayers namely

are augmented with LoRA modules using the same low rank decomposition strategy. This allows the multi-modal reasoning layers to adapt efficiently to new tasks and datasets, without disrupting the alignment learned during pre-training.

Through this systematic integration, LoRA modules act as

lightweight adapters distributed across all key projection layers in the model:

Each adapted matrix receives a low rank task specific update of the form

, with rank

. This design preserves the representational capacity of the original Transformer while reducing the number of trainable parameters by several orders of magnitude. In practice, this yields strong downstream performance with minimal computational overhead, making LoRA an effective and scalable strategy for adapting large vision language models to specialized tasks.

2.6.4. Discussion: Targeted LoRA Integration in Multi-Modal Architectures

This work adopts a targeted and function aware LoRA integration strategy within the multi-modal Vision Language Transformer, aiming to achieve effective adaptation with minimal computational overhead. Rather than applying LoRA indiscriminately across all layers, we prioritize modules that contribute most to task transferability and multi-modal alignment. The integration points follow the computational flow outlined in Algorithm 1, with LoRA modules strategically inserted at key transformation layers.

2. Vision Language Adapter (Cross Modal Alignment)

Serving as the bridge between visual and linguistic modalities, this module benefits from LoRA driven fine-tuning to enhance cross modal coherence. By introducing low rank updates into the input and output projections of the adapter, the model learns to align semantic and spatial information efficiently, improving multi-modal grounding without retraining the full backbone [

20].

3. Text Transformer Blocks (Joint multi-modal Reasoning).

Here, LoRA enriches the model’s capacity for reasoning over integrated visual and textual tokens. It modifies the query, value, and feed forward matrices to capture subtle cross modal dependencies, enabling efficient adaptation of the attention dynamics to context dependent multi-modal patterns.

5. Exclusion of Convolutional Layers.

Unlike dense linear layers, convolutional filters exhibit strong spatial priors and limited parameter redundancy, making lo rank decomposition suboptimal. Empirically, maintaining fixed convolutional parameters preserves low level feature stability while the subsequent Transformer and adapter layers perform domain specific adaptation.

In summary, LoRA serves as a compact yet powerful mechanism for multi-modal adaptation, enabling domain specific specialization of large vision language models while maintaining efficiency, generalization, and deployment feasibility in resource constrained environments.

3. Dataset Description: LEVIR-CC

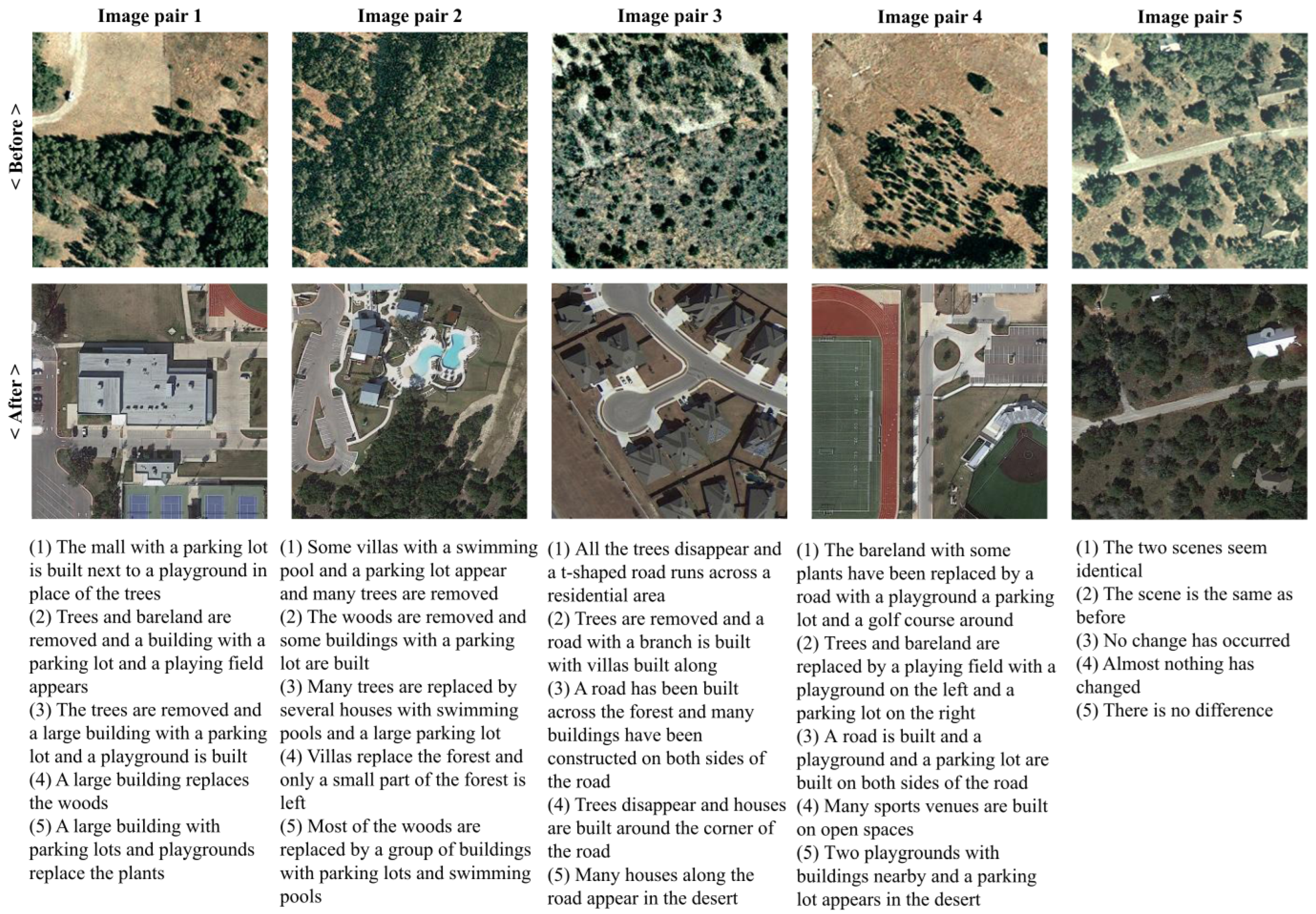

To evaluate the proposed multi-modal vision language framework for land cover change monitoring, we adopt the LEVIR-CC dataset, a large scale and richly annotated benchmark specifically designed for Remote Sensing Image Change Captioning (RSICC) tasks. This dataset provides a solid foundation for developing and validating models capable of generating natural language descriptions of land cover dynamics, effectively bridging visual change detection and semantic caption generation.

The LEVIR-CC dataset introduced in [

6]. The dataset is constructed from multi-temporal very high resolution (VHR) remote sensing imagery collected primarily from Google Earth, with a ground sampling distance of approximately

per pixel. It contains a total of 10,077 carefully aligned bitemporal image pairs, each of spatial size

pixels. Every image pair is accompanied by five human written captions, resulting in more than 50,000 natural language descriptions that narrate the observed changes.

Each caption provides concise yet semantically rich descriptions of surface changes such as the construction or demolition of buildings, road expansions, vegetation increase or loss, and other anthropogenic modifications. The textual annotations are linguistically diverse, with an average caption length of approximately words, covering a vocabulary of over unique tokens. The image pairs are temporally distributed across multiple years and include complex urban, suburban, and rural contexts, ensuring broad geographic and semantic diversity.

A key strength of LEVIR-CC lies in itsscale, diversity, and annotation quality. The dataset’s multi-domain coverage and fine grained textual labels enable robust cross modal learning between vision and language modalities. Furthermore, its balanced representation of change and non change samples allows for effective evaluation of both detection accuracy and descriptive reasoning.

Since its release, LEVIR-CC has evolved into a standard benchmark for multi-modal remote sensing research. Recent studies have used it to evaluate models for vision language pretraining, multi-modal reasoning, and semantic change detection [

5,

21,

22]. Its structured design, large scale human annotations, and well aligned bitemporal image caption pairs make it particularly suitable for training and assessing models that aim to jointly capture spatial, temporal, and semantic correlations.

Given these attributes, LEVIR-CC provides an ideal experimental platform for assessing our proposed architecture. It enables rigorous evaluation of both visual encoding performance and cross modal generative capabilities, offering a meaningful benchmark for understanding how transformer based vision language models can interpret and describe real world land cover evolution.

To provide a clearer understanding of the dataset characteristics,

Figure 3 (taken from [

6]) presents representative examples from the LEVIR-CC benchmark, highlighting various types of land cover changes and their associated human annotated captions.

The LEVIR-CC dataset presents a balanced distribution between

change and

no change samples, as shown in

Table 1. Each

Change image pair is annotated with five diverse captions describing specific land cover modifications, such as new constructions, vegetation loss, or infrastructure expansion. In contrast,

no change samples share a uniform set of five identical captions indicating the absence of observable change. This design allows the dataset to support both descriptive and discriminative evaluation: models can be assessed not only on their capacity to generate semantically rich captions for true changes but also on their ability to correctly identify and represent stable regions through consistent

no change predictions.

Dual Task Challenge in LEVIR-CC

The evaluation of models trained on LEVIR-CC requires special attention due to its inherent dual task nature. The dataset simultaneously supports two distinct but complementary objectives: identifying whether a bi-temporal image pair represents a change orno change scenario, and generating descriptive captions for samples containing actual changes. This duality complicates metric interpretation, as conventional captioning scores such as BLEU, CIDEr, METEOR and SPICE are meaningful only for positive change cases, where textual descriptions convey semantic content. For no change samples, evaluation should instead focus on the model’s ability to correctly recognize stability and consistently generate neutral no change expressions. Aggregating both types of samples into a single evaluation can obscure performance, since standard text similarity metrics are insensitive to the semantic polarity of negative statements. Therefore, a decoupled evaluation protocol separating change and no change cases provides a more faithful and interpretable assessment of multi-modal models designed for change captioning tasks.

4. Metrics Used in Image Captioning

In this section, we describe the most commonly used automatic evaluation metrics for image captioning. These include BLEU [

11], METEOR [

12], ROUGE [

13], CIDEr [

14], and SPICE [

15]. Each metric captures different aspects of caption quality, from

n-gram overlap to semantic content.

The variability in human descriptions poses a fundamental challenge for automatic evaluation of captioning models. Metrics such as BLEU or ROUGE, which rely heavily on surface level n-gram overlap, often penalize outputs that use different words or sentence structures despite accurately conveying the same semantic meaning. In the context of multi-temporal remote sensing, this issue becomes even more critical, since descriptions of land cover change may legitimately emphasize different aspects of the same transformation, such as the disappearance of vegetation versus the emergence of cropland. As a result, a model’s prediction may be judged as poor under lexical overlap metrics even when it is semantically valid. More advanced measures like CIDEr and SPICE attempt to mitigate this limitation by incorporating consensus weighting or semantic parsing, but they too struggle to fully capture domain specific nuances, such as the ecological and socioeconomic significance of certain changes. These challenges highlight the need for careful selection and interpretation of evaluation metrics when assessing captioning systems designed for environmental monitoring.

BLEU: N-gram Precision in Captioning

BLEU is based on the precision of n-grams between candidate and reference captions. While it is widely used due to its simplicity and comparability, it is less effective for short, variable captions where synonyms and paraphrasing are common.

METEOR: Recall Oriented Evaluation

METEOR improves upon BLEU by incorporating stemming, synonyms, and recall. It has been shown to correlate better with human judgments, especially at the sentence level, making it suitable for evaluating short captions.

ROUGE: Overlap Based Summarization Metric

Originally proposed for text summarization, ROUGE measures recall oriented overlap using n-grams and longest common subsequences. Its focus on recall makes it less common in captioning but still useful for capturing content coverage.

CIDEr: Consensus Based Evaluation

CIDEr was specifically designed for image captioning. It employs TF-IDF weighted n-gram similarity to reward informative and distinctive words. It is the primary metric in many captioning benchmarks, as it correlates strongly with human judgments.

SPICE: Semantic Propositional Image Caption Evaluation

SPICE evaluates caption quality by comparing scene graphs of candidate and reference captions, focusing on semantic propositional content such as objects, attributes, and relationships. This semantic based approach makes it more effective than lexical overlap metrics for tasks requiring semantic accuracy, and it correlates well with human judgments, particularly in contexts with paraphrasing or synonym use.

4.1. Importance of Metrics for Change Captioning

Given the specific challenges of multi-temporal remote sensing captioning, it is useful to consider the relative importance of these metrics for evaluating model performance. CIDEr and SPICE generally provide the most informative assessment, as they better capture semantic content and reward distinctive, contextually meaningful descriptions of land cover changes. METEOR also holds high relevance due to its consideration of synonyms and recall, which is critical when multiple valid expressions can describe the same transformation. BLEU and ROUGE, while still valuable for lexical consistency and content coverage, are less reliable in this context because they are highly sensitive to exact word matches and may penalize semantically correct but lexically diverse predictions. Therefore, for change captioning tasks, metrics emphasizing semantic fidelity and consensus (CIDEr, SPICE, METEOR) should be prioritized, while BLEU and ROUGE can serve as supplementary measures to complement the overall assessment (see

Table 2).

According to

Table 2, the following composite measures have been introduced in the state of the art approach to address the limitations of individual metrics and provide a more robust evaluation framework:

The composite score offers a balanced integration of lexical and semantic evaluation criteria by combining BLEU-4, METEOR, ROUGE-L, and CIDEr. This formulation jointly accounts for precision and recall, capturing both textual consistency and descriptive adequacy. The simplified variant focuses on meaning oriented assessment through METEOR and CIDEr, providing a compact yet semantically robust indicator of performance. Meanwhile, further strengthens the emphasis on semantic fidelity by incorporating SPICE alongside METEOR and CIDEr, making it especially relevant for tasks where the accurate conveyance of meaning and contextual relationships is critical.

Overall, these composite metrics are intended to counterbalance the weaknesses of individual measures particularly their susceptibility to lexical variation and deliver a more comprehensive and reliable evaluation framework for multi-temporal remote sensing image captioning models.

To illustrate the behavior and relevance of the previously described metrics in the context of multi-temporal change captioning, we conducted a set of experiments using the test set of the LEVIR-CC dataset. Each sample in the dataset is annotated with five reference captions describing the observed changes. In our evaluation setup, we follow a common protocol in captioning studies: one caption is treated as the predicted output from the model, while the remaining four captions serve as reference descriptions. This approach allows us to simulate the variability in human language and analyze how different metrics respond to lexical and semantic differences between the predicted caption and multiple valid references.

By applying BLEU, METEOR, ROUGE, CIDEr, and SPICE in this setting, we can observe the sensitivity of each metric to paraphrasing, synonym usage, and semantic coverage, providing insights into their suitability for evaluating change captioning tasks. The results for samples with

only changes are presented in

Table 3, while the results for samples with

no changes are shown in

Table 4.

The evaluation results for

no change samples, presented in

Table 4, reveal a markedly different behavior compared to the change samples. In this case, the overall metric values are substantially lower, especially for BLEU and ROUGE, which depend heavily on lexical overlap. This outcome is expected, as

no change captions typically employ short and semantically equivalent expressions with considerable lexical variation (e.g.,

there is no difference vs.

the two scenes seem identical), resulting in limited

n-gram correspondence among captions.

It is important to note that the CIDEr metric was not computed for this subset, since many identical phrases occur repeatedly across samples, leading to undefined or non informative TF–IDF weighting. Under such conditions, CIDEr cannot reliably capture distinctiveness or informativeness, which are central to its formulation. Conversely, METEOR and SPICE maintain comparatively higher and more consistent values, reflecting their greater sensitivity to semantic similarity and propositional meaning.

Overall, the results emphasize the limitations of traditional overlap-based metrics in evaluating semantically equivalent no change captions. In fact, most state of the art methods that report high evaluation scores on such samples do so by predicting a fixed no change phrase identical to the reference text. While this strategy ensures perfect metric alignment, it effectively transforms the problem from a caption generation task into a binary classification one simply detecting whether change occurs or no thus overlooking the generative and descriptive objectives that define captioning based approaches.

To further illustrate the evaluation challenges discussed, we conducted an additional experiment including both

change and

no change samples from the LEVIR-CC test set. For the latter, five equivalent expressions were employed to indicate the absence of change, each corresponding to one of the reference captions, as shown in

Table 5. This setup enables us to analyze how lexical variability among semantically equivalent

no change statements influences the behavior of automatic evaluation metrics. Specifically, we compare three configurations using caption 3 the best performing case in

Table 3 as the predicted text:

- (i)

Original configuration: The no change sentences differ in wording across captions.

- (ii)

Unified phrasing configuration: The predicted caption employs a unified phrasing identical to one of the reference sentences (“the two scenes seem identical”).

- (iii)

Minor lexical difference configuration: Introduces a subtle variation in the no change sentence by altering a single word (“is”) relative to caption 4, changing “no change has occurred” to “no change is occurred”.

In these cases, all no change samples are correctly predicted. In the first case, the samples are expressed through distinct yet semantically equivalent phrases. In the second, the model generates a no change sentence that exactly matches one of the reference texts, representing the most typical situation in practical model evaluation. The third configuration, despite involving only a minimal lexical modification, yields a considerable decrease in most metric scores. Together, these comparisons highlight the strong sensitivity of automatic metrics to surface level textual similarity and their tendency to over penalize valid paraphrases, thus underscoring the inherent limitations of lexical overlap based measures in dual task captioning scenarios.

The results in

Table 6 clearly demonstrate the sensitivity of traditional captioning metrics to lexical variation in

no change expressions. Despite conveying the same semantic meaning, the original configuration with diverse

no change phrases yields substantially lower scores across all metrics. When a single, consistent phrasing is used, performance values increase dramatically particularly for BLEU, ROUGE, and CIDEr, which rely on exact

n-gram overlap. This outcome empirically supports the discussion in the previous section: automatic metrics can undervalue semantically correct predictions in dual task captioning datasets like LEVIR-CC, where linguistic diversity naturally arises. Therefore, metric interpretation must account for this limitation to avoid misleading conclusions about model quality.

4.2. Toward a More Suitable Evaluation Strategy for Dual Task Captioning

The experiments discussed above reveal a key limitation of traditional captioning metrics when applied to the LEVIR-CC dual task setting. Conventional measures such as BLEU, METEOR, ROUGE, CIDEr, and SPICE are well suited for evaluating textual descriptions of visual changes but become unreliable when assessing no change captions. In these cases, minor lexical variations between semantically equivalent sentences (e.g., “the scene is the same as before” vs. “the two scenes remain identical”) can lead to substantial fluctuations in computed scores, even though both statements convey the same meaning. This inconsistency obscures the true performance of models that must simultaneously detect and describe changes.

To address this issue, we propose a two branch evaluation protocol that separates the measurement of descriptive quality from the assessment of change detection accuracy:

Change samples: For samples where a change is present, we continue to employ standard captioning metrics BLEU, METEOR, ROUGE, CIDEr, and SPICE to quantify the quality, fluency, and semantic correctness of the generated change descriptions.

No change samples: For samples where

no change is present, evaluation focuses on the model’s ability to correctly recognize scene stability. Since this task represents a categorical rather than descriptive decision, traditional similarity based captioning metrics are not appropriate. Instead, we evaluate such cases using

accuracy, defined as the ratio of correctly identified

no change samples to the total number of

no change instances:

where

denotes the number of correctly predicted

no change cases, and

is the total number of samples labeled as

no change. This formulation yields an interpretable measure of the model’s capacity to detect temporal stability, independent of linguistic variability.

Finally, we define a unified evaluation index, denoted as the Change Captioning Score (CCS), which integrates both descriptive and detection performance using a balancing coefficient

. Each variant of the composite metric can be incorporated as the change sensitive component:

The parameter allows flexible weighting according to dataset composition or application focus for example, for balanced test sets or when precise change description is prioritized.

This hybrid evaluation framework mitigates the lexical sensitivity of traditional metrics and aligns the assessment process with the dual objectives of multi-modal change captioning: accurately identifying when a change occurs and effectively describing what has changed.

5. Experiments

This section presents an empirical evaluation of the proposed multi-modal Vision Language Transformer framework for multi-temporal remote sensing image captioning. Leveraging the LEVIR-CC dataset (

https://github.com/Chen-Yang-Liu/LEVIR-CC-Dataset, accessed on 17/10/2025), we systematically assess the model’s capacity to generate semantically rich and spatially accurate captions that reflect land cover changes over time.

To evaluate the effectiveness of our proposed framework, we employ the Mistral-Small-3.1-24B-Instruct-2503 (

https://huggingface.co/mistralai/Mistral-Small-3.1-24B-Instruct-2503, accessed on 17/10/2025) model as the foundational multi-modal Large Language Model (LLM) for fine-tuning with Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA). This state of the art, instruction tuned model with 24 billion parameters is specifically designed to handle image-text inputs and produce textual outputs, making it well suited for tasks requiring joint reasoning across visual and linguistic modalities. By integrating LoRA, we efficiently adapt its pre-trained weights to the specialized domain of multi-temporal remote sensing image captioning, while preserving the model’s general multi-modal knowledge and language generation capabilities. This approach ensures that the model retains its robust ability to process and reason about both visual and textual information, while being fine-tuned to accurately describe spatial and temporal land cover changes all with significantly reduced computational overhead compared to full fine-tuning.

5.1. LoRA Integration: Target Layer Selection

To enable efficient fine-tuning of the Mistral-Small-3.1-24B-Instruct-2503 model for multi-temporal remote sensing image captioning, we strategically apply Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) to key layers in the architecture, as outlined in

Section 2. Specifically, LoRA is integrated into the following critical components:

-

- –

Query projection

- –

Key projection)

- –

Value projection

- –

Output projection

These layers are part of the Multi Head Self-Attention (MHSA) mechanism within the multi-modal Transformer blocks, where LoRA enhances the model’s ability to capture complex dependencies between visual and textual tokens.

-

- –

Input projection

- –

Output projection

These layers form the core of the Vision Language Adapter, which bridges the visual encoder and the multi-modal Transformer. By applying LoRA here, we ensure that the adapter effectively aligns the visual and textual feature spaces, enabling seamless cross modal reasoning.

This targeted application of LoRA allows the model to specialize in generating accurate and descriptive captions for land cover changes, while preserving its general multi-modal capabilities and significantly reducing the computational resources required for fine-tuning.

The following

Table 7 details the parameter architecture of our multi-modal model, distinguishing between frozen and LoRA trainable components, with the LoRA matrices using a rank of 128 for efficient fine-tuning.

Table 8.

Parameter statistics of the multi-modal base model. The table reports the total parameter count, trainable (LoRA) subset, and frozen parameters. LoRA adapters (rank = 128) enable fine-tuning only of the total parameters.

Table 8.

Parameter statistics of the multi-modal base model. The table reports the total parameter count, trainable (LoRA) subset, and frozen parameters. LoRA adapters (rank = 128) enable fine-tuning only of the total parameters.

| Parameter Type |

Count |

% of Total |

| Total Parameters |

24.75B |

100% |

| • Trainable Parameters (LoRA) |

741.3M |

3.0% |

| • Frozen Parameters |

24.01B |

97.0% |

Model Architecture and Training Configuration

Key architectural parameters are summarized below; detailed layer shapes are provided in

Table 7.

Table 9.

Training configuration used for LoRA fine-tuning of the multi-modal Mistral-24B model. All settings are derived directly from the training script. Lazy data loading and random sampling were applied to improve efficiency.

Table 9.

Training configuration used for LoRA fine-tuning of the multi-modal Mistral-24B model. All settings are derived directly from the training script. Lazy data loading and random sampling were applied to improve efficiency.

| Parameter |

Value / Description |

| LoRA Configuration |

Rank = 128, = 32, dropout = 0.1 |

| Sequence Length |

2048 tokens |

| Batch Size |

10 |

| Training Epochs |

5 |

| Learning Rate |

, cosine with restarts scheduler |

| Optimizer |

AdamW (weight decay = 0.01, max grad norm = 1.0) |

| Loss Function |

Cross entropy with masking applied. |

Model Parameters

Model Dimension (): 5120.

Number TextTransformer Blocks: 40.

Attention Heads (): 40.

Head Dimension (): 128.

Hidden Dimension (): 32,768.

Vocabulary Size: 131,072.

Normalization Epsilon (): .

Vision Transformer: patch size and 24 transformer blocks.

Hardware Configuration

The training was performed using 3 NVIDIA A100 GPUs (40 GB each) in a distributed setup. Mixed precision computation (bfloat16) and torch.distributed data parallelism were employed to balance memory usage and throughput during LoRA fine-tuning of the Mistral-Small-3.1-24B-Instruct model. This configuration provided sufficient computational capacity to handle the multi-modal inputs and long sequence lengths.

Software Environment and Resources

The fine-tuning experiments were conducted using Python 3.10 and the PyTorch framework, built upon the Hugging Face Transformers ecosystem. The workflow integrated key libraries including transformers, datasets, and peft for LoRA based parameter efficient adaptation. Image preprocessing and feature handling were managed through torchvision and Pillow (PIL).

For quantitative assessment, we employed the Microsoft COCO Caption Evaluation toolkit, available at (

https://github.com/jiasenlu/coco-caption/tree/master, accessed on 17/10/2025). This toolkit is widely adopted for benchmarking captioning and multi-modal generation tasks, providing standardized implementations of key metrics such as BLEU, METEOR, ROUGE-L, CIDEr and SPICE.

5.2. Quantitative Results and Analysis

Table 10 and

Table 11 summarize the quantitative comparison between the proposed method and representative state of the art (SoTA) approaches on the LEVIR-CC dataset.

Table 10 reports the results for

change samples, evaluated using standard lexical and semantic metrics, as well as the aggregated indicators

,

, and

.

The proposed model achieves superior performance across the majority of semantically oriented metrics, particularly METEOR, ROUGE-L, and CIDEr, indicating improved descriptive precision and contextual understanding. While SAT-Cap attains slightly higher BLEU scores due to greater lexical overlap with reference captions, our model exhibits a more balanced performance overall. The consistent gains in both and highlight stronger agreement between lexical accuracy and semantic coherence, underscoring the effectiveness of the multi-modal fusion and LoRA based adaptation strategy.

Table 11 extends the evaluation to include

no change samples via the

score, and integrates both sample ranges using the Complementary Consistency Scores (CCS) defined in

Section 4.2. For this analysis, the balancing coefficient is set to

, providing equal emphasis on descriptive fidelity and categorical accuracy.

In this complementary evaluation, the proposed framework achieves the highest consistency across both change and no change scenarios, reaching and . These results confirm the model’s capacity to generalize effectively, maintaining coherent and contextually appropriate descriptions even in temporally stable scenes. By contrast, previous approaches often reach high values only when the output captions exactly replicate reference expressions, thereby reducing the generative nature of the task to simple classification.

A further advantage of our approach lies in the integration of newly learned knowledge into the pre-trained language model without disrupting its universal linguistic space. The large language model employed here retains its general purpose vocabulary and semantic associations, allowing it to describe remote sensing phenomena using natural and contextually meaningful language rather than dataset specific terms. This contrasts sharply with many SoTA captioning models, which rely on restricted vocabularies or dataset dependent token dictionaries. The proposed hybrid ViT–LLM architecture, enhanced through LoRA fine-tuning, therefore bridges specialized remote sensing semantics with a general linguistic foundation promoting better cross domain generalization and more human aligned textual descriptions of land cover dynamics.

Table 10 highlights an important observation regarding the evaluation of methods on samples with only changes. While some approaches, such as

Chg2Cap, may achieve competitive overall performance when considering combined tasks, a closer look at metrics focused purely on text generation reveals a different trend. Under this isolated evaluation,

RSICCformer outperforms

Chg2Cap in both

(

vs.

) and

(

vs.

), demonstrating superior descriptive fidelity and semantic coherence. This underscores the importance of disentangling classification and generation tasks in order to fairly assess methods capabilities in producing accurate and meaningful captions. Notably, our proposed approach further surpasses all baselines across most generation focused metrics, reinforcing its effectiveness in capturing the nuanced changes in the scene.

In this evaluation, Caption 3 is treated as the prediction while the other four captions (see LEVIR-CC

Section 3) serve as references. Caption 3 reflects the accurate description provided by a human expert, with all captions being correct and valid. However, it often employs different words to describe the changes, so the differences mainly affect semantics rather than lexical choice. Despite its expert quality, Caption 3 does not outperform any of the automatic generation methods across the considered metrics. Notably, METEOR demonstrates the closest alignment with Caption 3, indicating its particular sensitivity to semantic adequacy and meaning preservation, which are central to the human expert’s description.

6. Conclusions

The findings of this study demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed multi-modal Vision Language Transformer framework, enhanced with Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA), for the task of multi-temporal remote sensing image captioning. By jointly leveraging visual and textual modalities, the model successfully bridges the gap between spatial temporal change detection and natural language generation. The integration of LoRA enables efficient fine-tuning of large pre-trained language models, preserving their general linguistic knowledge while adapting them to the specialized domain of remote sensing. This approach represents a significant step forward compared with prior methods such as Chg2Cap and RSICCformer, which rely on more rigid, dataset specific vocabularies and often fail to generalize across broader scenarios.

From a comparative standpoint, the proposed architecture achieves superior semantic coherence and descriptive expressiveness, particularly in challenging cases where subtle land cover changes occur. The introduction of the Complementary Consistency Score (CCS) family of metrics , , and provides a fairer and more comprehensive evaluation protocol, capturing both the quality of change descriptions and the model’s accuracy in recognizing no change instances.

In a broader context, the results suggest that integrating universal language pre-trained models into remote sensing pipelines can significantly enhance interpretability and transferability, reducing dependence on dataset specific linguistic patterns. This aligns with recent trends in multi-modal learning that emphasize generalization across domains rather than narrow task optimization. Moreover, the capacity of the model to process paired temporal imagery illustrates its potential for broader environmental monitoring applications, such as disaster assessment, deforestation tracking, or agricultural change analysis.

Future research should explore extending this framework toward multi-sensor and multi-temporal fusion, incorporating radar and hyperspectral data to enrich semantic understanding. Additionally, instruction tuned and prompt based adaptation could be investigated to enable more flexible and user guided caption generation. Finally, expanding the evaluation to cross dataset and multi-lingual benchmarks would further assess the robustness and universality of the proposed approach.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, and code, J.L.L.; review and editing, P.Q, P.S and V.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ViT |

Vision Transformer |

| LLM |

Large Language Model |

| LoRA |

Low-Rank Adaptation |

| BLEU |

Bilingual Evaluation Understudy |

| METEOR |

Metric for Evaluation of Translation with Explicit ORdering |

| ROUGE |

Recall-Oriented Understudy for Gisting Evaluation |

| CIDEr |

Consensus-based Image Description Evaluation |

| SPICE |

Semantic Propositional Image Caption Evaluation |

| LEVIR-CC |

LEVIR Change Captioning Dataset |

References

- Vinyals, O.; Toshev, A.; Bengio, S.; Erhan, D. Show and Tell: A Neural Image Caption Generator. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 3156–3164.

- Daudt, R.C.; Le Saux, B.; Boulch, A. Fully Convolutional Siamese Networks for Change Detection. In 2018 25th IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), pp. 4063–4067.

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Hallacy, C.; Ramesh, A.; Goh, G.; Agarwal, S.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; Mishkin, P.; Clark, J.; Krueger, G. Learning Transferable Visual Models from Natural Language Supervision. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), pp. 8748–8763.

- Chang, S., & Ghamisi, P. Changes to captions: An attentive network for remote sensing change captioning. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2023, 32, 6047–6060. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Yu, W., & Ghamisi, P. Change Captioning in Remote Sensing: Evolution to SAT-Cap–A Single-Stage Transformer Approach. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.08114 2025. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C., Zhao, R., Chen, H., Zou, Z., & Shi, Z. Remote sensing image change captioning with dual-branch transformers: A new method and a large scale dataset. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Dosovitskiy, A. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.11929. [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2017, 30.

- Su, J.; Ahmed, M.; Lu, Y.; Pan, S.; Bo, W.; Liu, Y. Roformer: Enhanced transformer with rotary position embedding. Neurocomputing 2024, 568, 127063. [CrossRef]

- Alayrac, J.B.; Donahue, J.; Luc, P.; Miech, A.; Barr, I.; Hasson, Y.; Lenc, K.; Mensch, A.; Millican, K.; Reynolds, M.; Ring, R. Flamingo: A visual language model for few-shot learning. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, 35, 23716–23736.

- Papineni, K., Roukos, S., Ward, T., & Zhu, W.-J. BLEU: a method for automatic evaluation of machine translation. Proc. 40th Annu. Meet. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 2002, 311–318. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S., & Lavie, A. METEOR: An automatic metric for MT evaluation with improved correlation with human judgments. Proc. ACL Workshop Intrins. Extrins. Eval. Measures Mach. Transl. Summar. 2005, 65–72.

- Lin, C.-Y. ROUGE: A package for automatic evaluation of summaries. Proc. Workshop Text Summarization Branches Out (WAS 2004) 2004, 74–81.

- Vedantam, R., Zitnick, C.L., & Parikh, D. CIDEr: Consensus-based image description evaluation. Proc. IEEE Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit. 2015, 4566–4575. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, P., Fernando, B., Johnson, M., & Gould, S. SPICE: Semantic propositional image caption evaluation. Proc. Eur. Conf. Comput. Vis. (ECCV) 2016, 382–398. [CrossRef]

- Aghajanyan, A., Zettlemoyer, L., & Gupta, S. Intrinsic dimensionality explains the effectiveness of language model fine-tuning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2012.13255 2020.

- Wang, S., Yu, L., & Li, J. LoRA-GA: Low-Rank Adaptation with Gradient Approximation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.05000 2024.

- Hu, E.J., Shen, Y., Wallis, P., Allen-Zhu, Z., Cao, Y., Wang, S., & Wang, L. LoRA: Low-Rank Adaptation of Large Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2106.09685 2021.

- Dosovitskiy, A., Beyer, L., Kolesnikov, A., Weissenborn, D., Zhai, X., Unterthiner, T., Dehghani, M., Minderer, M., Heigold, G., Gelly, S., & others. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.11929 2020.

- Radford, A., Kim, J.W., Hallacy, C., Ramesh, A., Goh, G., Agarwal, S., Sastry, G., Askell, A., Mishkin, P., Clark, J., & others. Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. Proc. Int. Conf. Mach. Learn. 2021, 8748–8763.

- Yang, Y., Liu, T., Pu, Y., Liu, L., Zhao, Q., & Wan, Q. Remote sensing image change captioning using multi-attentive network with diffusion model. Remote Sens. 2024, 16(21), 4083. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y., Li, L., Chen, K., Liu, C., Zhou, F., & Shi, Z. Semantic-cc: Boosting remote sensing image change captioning via foundational knowledge and semantic guidance. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).