Multilingual dialogue, a cornerstone of human interaction, encompasses the linguistic diversity across languages and the complexities of culture, context, and communication styles. In recent years, the development of multilingual dialogue systems has become a critical area of research in natural language processing (NLP). Dialogue systems, which facilitate communication between humans and machines, have predominantly been designed for a single language. However, multilingual capabilities have become essential for widespread adoption with increasing globalization and the need for more inclusive technologies. This has led to the creation of large-scale multilingual dialogue datasets such as MultiWOZ 2.0 and OPUS-MT, which serve as foundational resources for training and evaluating dialogue models across multiple languages. These datasets have enabled significant strides in developing systems that can handle cross-lingual interactions effectively.

Advances in pre-trained language models, such as BERT and T5, have accelerated progress in multilingual dialogue systems. These models leverage transfer learning to adapt to various linguistic contexts, enabling dialogue systems to generate coherent, context-aware responses in multiple languages. Additionally, the application of cross-lingual transfer learning has proven valuable in improving performance for low-resource languages by transferring knowledge from high-resource languages, as demonstrated by Ji et al. In parallel, techniques like dialogue state tracking have enhanced the ability of multilingual systems to maintain context and coherence over long conversations.

Despite these advancements, several challenges remain. Issues such as data silos, inconsistent data quality, and the scalability of models across languages continue to hinder the development of truly universal multilingual systems. Efforts to address these challenges include improving the quality of training data (the area where the research paper is focused on), leveraging AI-powered multilingual tools, and optimizing data preprocessing strategies. These advancements are vital to ensuring the development of multilingual dialogue systems that are not only scalable but also capable of providing seamless, context-aware interactions in various languages.

While models trained on multilingual dialogue datasets have demonstrated significant potential in enhancing communication and overcoming language barriers worldwide, a notable lack of comprehensive multilingual conversational speech datasets remains. The research community requires a diverse, multilingual conversation dataset to improve models on speaker diarization and ASR (Automatic Speech Recognition). Just like ImageNet is for image recognition, we need a multilingual conversation dataset that could be used to train and build a highly scalable, generalized speech recognition model. Though some publicly available conversation datasets exist, they are all in American English accents and will not work in training speech recognition models for other languages. LibriSpeech and TED-LIUM are suitable for automatic speech recognition (ASR) tasks but primarily consist of isolated utterances or formal speech. Switchboard and Fisher are focused on telephone conversations in English but lack multilingual and emotionally rich diversity.

To address these limitations, in this paper, we propose the Multi-lingual Dialogue Dataset, a dialogue dataset with multilingual, multi-turn dialogues from the topics and summaries derived from the New York Times dataset. Similar to how instruction-tuning datasets are generated to train vision and language assistants, we use a prompting-based approach to develop a multilingual, multi-turn dialogue dataset using a pre-trained LLM.

The recent advancements in large language models (LLMs) have led to impressive performance across various natural language processing (NLP) benchmarks. These models, trained on vast amounts of unsupervised text data, significantly benefit numerous downstream text generation tasks. LLMs can be fine-tuned by utilizing instruction tuning to address a wide range of NLP challenges better. Furthermore, LLMs exhibit in-context learning capabilities, meaning they can adapt and learn from a few examples within a given context, even if those examples were not present during training. These characteristics make LLMs highly appealing for other modalities, such as speech. Given their success in NLP, there is growing interest in leveraging LLMs to enhance speech modeling as well.

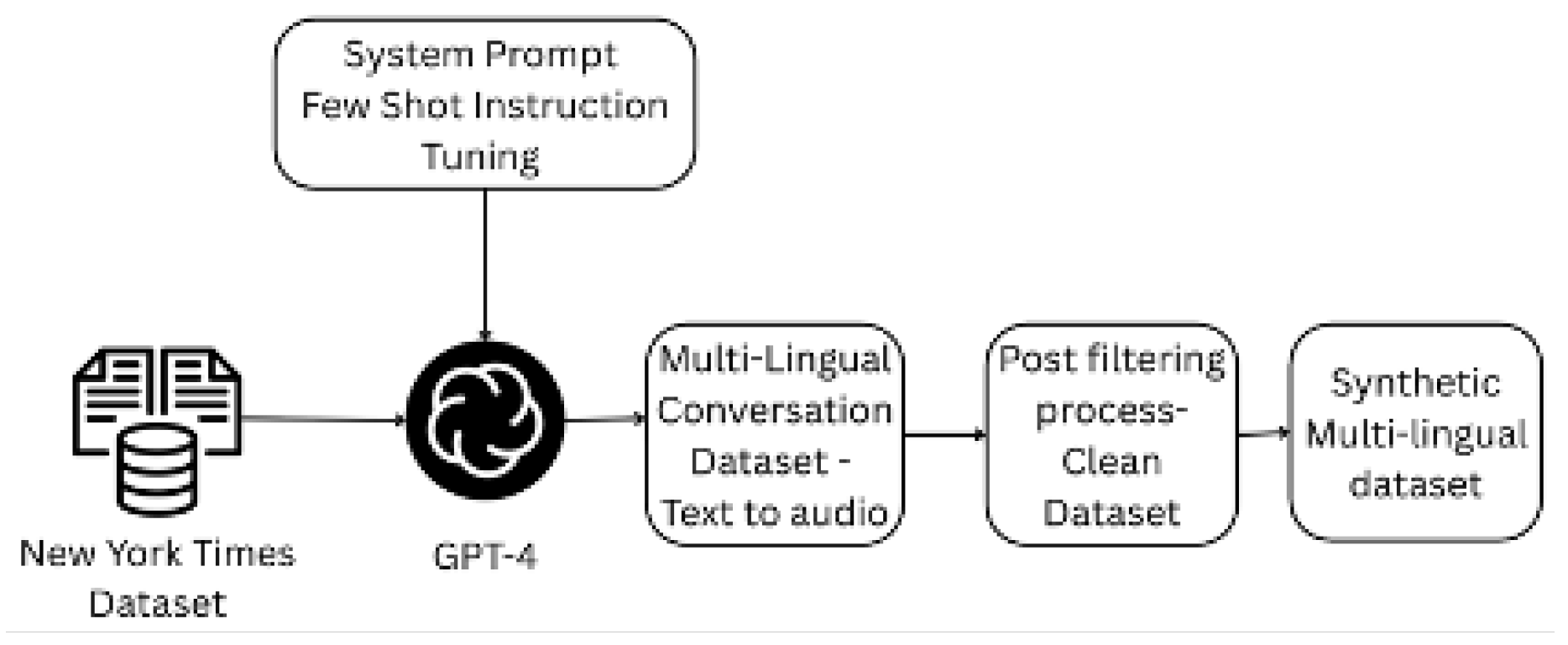

For creating the synthetic dataset, we utilize New York Times article topics and the synopsis of the article to guide the dialogue generation process using GPT-4. Additionally, we implement data filtration strategies to filter out any harmful opinionated dialogues and noisy synthetic dialogues, therefore promoting the retention of the most reliable ones. Our proposed dataset comprises 200K samples, each containing between four and eight dialogue turns. Our main contributions are: 1) a dataset pipeline for generating a multilingual dialogue dataset for any language from any existing structured dataset, and 2) the evaluation of existing audio-augmented large language models on our proposed dataset.

Related Work

Instruction-following Large Language Models (LLMs) have exhibited exceptional performance in zero-shot and few-shot tasks within the language domain, including machine translation, summarization, and other related tasks. The concept of creating models that can follow instructions has since been expanded to other domains, including vision and audio.

LLaVA made the first attempt at generating instruction-following data involving visual content using GPT-4. Specifically, they leverage image captions and bounding box localization as metadata for the image, which is then used as a query for the language model. In total, they gather 158k samples for language-image instruction-following data.

Since then, increasing interest has been in creating instruction-following datasets like VALLEY, Macaw-LLM, and Video-ChatGPT. In the audio domain, the LTU dataset was generated using GPT to make an open-ended question-answering dataset to assess general knowledge and reasoning about everyday sounds. However, LTU’s dataset is limited in several ways: it only includes single-turn conversations, lacks complex inter-conversational context, and does not feature strong correlations between rounds. On the other hand, Qwen-Audio has curated a 20k audio-based instruction-following dataset, but there is minimal discussion regarding its curation process or the specifics of the dataset itself. Although some conversations exist today, such as Switchboard and DailyDialogue, for audio LLM training, these datasets are particular to the English language, and the opportunity to scale the models to multilingual becomes limited due to the unavailability of multilingual datasets.

Our Multi-Lingual Dialogue Dataset addresses all the above-mentioned limitations by generating multi-lingual, multi-turn conversations for article topics and summaries from the New York Times dataset. Compared to existing datasets, Multi-lingual Dialogue Datasets have multi-turn dialogues in various languages with strong correlations between rounds through the presence of pronouns (e.g., he, she, it), follow-up questions based on the previous answer, and complex context.

Recent research has focused on advancing audio foundation models [that leverage large language models (LLMs) to understand audio content. These models typically use an audio encoder to convert audio into tokens, which are then processed with textual instructions by an LLM to generate a final response. Pretrained on various tasks, such as audio captioning, emotion recognition, sound event classification, speech recognition, and music understanding, these models have demonstrated significant improvements in zero-shot and few-shot performance when using a unified architecture. While these models show strong audio comprehension, recent work like Audio Flamingo has introduced methods such as in-context learning and retrieval-augmented generation to further enhance their ability to follow instructions, achieved through fine-tuning with interleaved audio-text pairs. To assess the relevance of our proposed Multi-lingual Dialogue Dataset, we evaluate the performance of audio foundation models, including LTU, Qwen-Audio, and Audio Flamingo, on multi-turn dialogues.

Methodology

Data Pipeline

This section will discuss the data generation pipeline illustrated in

Figure 1. The Multi-Lingual Dialogue Dataset (MLDD) is constructed using The New York Times dataset. The structured NYT dataset consists of 1.8 million articles published between January 1, 1987, and June 19, 2007. The article metadata is provided by the NYT Newsroom in the English language. The dataset contains 1.8M records in XML file format. Out of the 1.8M files, we randomly selected 500K documents for our dataset creation process. The New York dataset metadata comprises the date and time published, title, synopsis of the article, tags, etc. Articles are tagged for persons, places, organizations, titles, and topics using a controlled vocabulary applied consistently across articles. Tags are leveraged as filtering criteria to filter out articles on categories such as sports and places. Further, the title of the article and the summary of the article are considered for prompting the LLM, GPT-4 in this case, to generate 4-8 turn conversations.

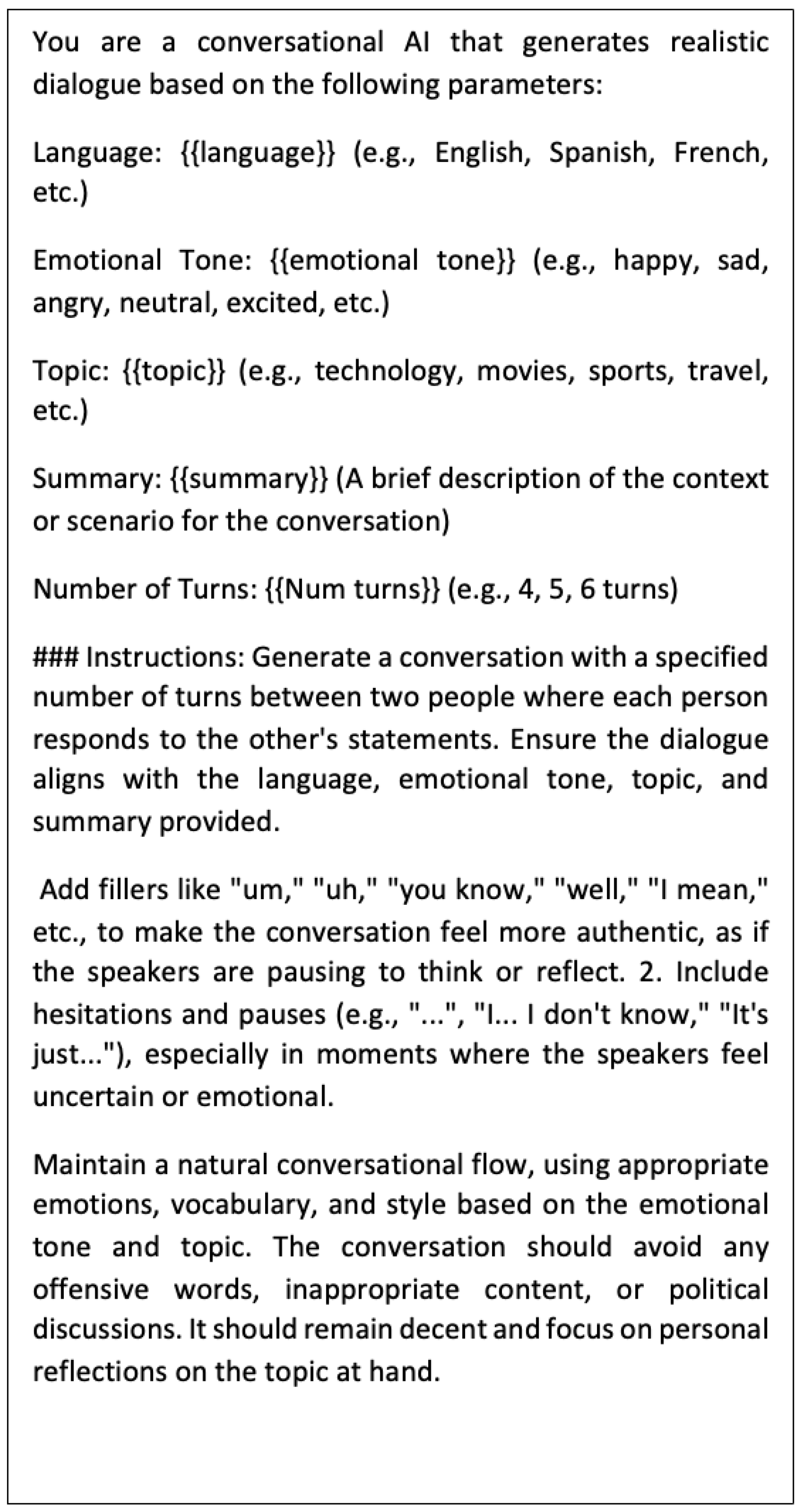

Prompt

To generate conversation on different topics, we leverage intensive LLM prompting. We design specific prompt templates to generate

1) Multiturn dialogues and

2) emotional tones of the conversation.

LLMs are prompted to adapt while coming up with the conversation content. Necessary jargon specific to expressing the emotion of the conversation is used. For example, for an angry emotion, conversations like “Huh! This is disappointing “, and for a happy emotion, the conversation will start with “I am so thankful and glad that…”

LLMs are carefully prompted to limit the conversation generation to between 4-8 turns, and guardrails are established to ensure LLMs do not become opinionated in the conversations generated. The language in which the conversation is generated is decided dynamically through random selection. The system prompt would look like in

Figure 2. We adopted a few-shot prompting to instruct the LLM model on the expected outcomes. We observed that in this case,few-shot prompting worked better than zero-shot prompting.

Data Filtration

Our data generation pipeline in the methodology section has two filters—one before passing on to the LLM and the other after the LLM output is generated. In the pre-processing step, we filter out contents from the New York Times dataset on topics such as sports, music, fashion, health & wellness, technology, science & environment, education, lifestyle, culture, arts, and travel. We restricted ourselves to generic topics to make sure the conversation generated did not become opinionated and biased.

The second filtration is done on the LLM output (conversation dataset) to ensure the conversation is aligned with the topic and the summary being passed to the LLM. Any conversation record that does not adhere to this rule will be filtered out as part of the final dataset. This is done by computing the cosine similarity between the QA pair in each dialogue and the article synopsis, which was the input to the prompt

LLM, GPT-4, in this case. The dialogues are ranked in order based on the cosine similarity score, and the top 200,000 records are considered for the final processing of converting text to audio.

Text to Speech for Audio Generation

The final step in the data pipeline is the text-to-speech conversion. The conversation dataset containing the dialogues and the emotion tag is passed through text to the speech processor, which converts each dialogue into individual audio segments. The emotional aspect of the speech is handled by manipulating the pitch and rate of speech. An example of how pitch and rate are manipulated through emotions is illustrated in the tables below. To create a conversation that reflects the real world, we also attempted to adjust the speed throughout the conversation dynamically. Random noise was artificially appended to the existing audio to replicate background noise throughout the conversations.

Table 1.

Emotion to Pitch.

Table 1.

Emotion to Pitch.

| Emotional Tone |

Pitch |

Description |

| Happy |

1.2 |

Increase pitch for happy |

| Sad |

0.8 |

Lower pitch for sad |

| Angry |

1.4 |

Increase pitch and stress for angry |

| Neutral |

1 |

Normal pitch for Neutral |

Table 2.

Emotion to Rate.

Table 2.

Emotion to Rate.

| Emotional Tone |

Rate |

Description |

| Happy |

1.5 |

Increase rate for happy |

| Sad |

0.7 |

Slower rate for sad |

| Angry |

1.2 |

Faster rate for angry |

| Neutral |

1 |

Normal rate for neutral |

Datasets

Real-world conversational datasets are a rare find. Even the few examples stated in the introduction section of this paper are limited in size and are constrained to English conversations. No single dataset exists today that is a multilingual conversational dataset that mimics real-world discussions that could be used for training state-of-the-art ASR. The dataset created through the pipeline discussed in the methodology section would address the current gap in the speech analytics field. The dialogue dataset is split into a training dataset that contains 140,000 conversation samples, each between 4 and 8 turns of dialogue, and the testing dataset has the remaining 60,000 samples. The dataset was randomly sampled, and no filtering mechanism was applied to develop a training and test group.

While the Multi-Lingual Dialogue Dataset addresses the gap of a multilingual conversation dataset for researchers looking to build state-of-the-art models in the speech domain, we see opportunities for improvement in the existing process. For example, the post-filtering process that calculates the cosine similarity between the summary input and each conversation within the dialogue could be fully automated through the reinforcement learning technique, where an LLM can be assigned as an assessor or grader and, therefore, do an iterative prompt tuning for better conversation generation.

Experiments & Results

In this section, we give researchers ideas on how the dataset can be evaluated to understand if the dataset is rich and diverse in the context and if it represents real-world audio dialogues. We evaluated three recent audio understanding LLMs on our dialogues: Qwen-Audio and Audio-Flamingo. We use the pre-trained models as they are for inferencing and measurement on the Multi-lingual Dialogue Dataset. The results are in the table below. We first did a zero-shot evaluation. We convert the audio generated from the pipeline back to a text transcript and compare it to the original transcript created through the LLM. We picked CIDEr because it is more tolerant of variations and paraphrasing, so it is better at recognizing that different phrasings can still convey the same meaning.

Table 3.

Experiment Results.

Table 3.

Experiment Results.

| Model |

CIDEr |

BLEU4 |

| Audio-Flamingo |

0.6 |

0.1 |

| Audio-Flamingo

|

1.2 |

0.3 |

| LTU |

0.48 |

0.17 |

| LTU

|

0.67 |

0.25 |

| Qwen-Audio |

0.53 |

0.03 |

We also fine-tuned Audio-Flamingo and LTU on the Multi-Lingual Dialogue Dataset and compared the zero-shot results vs. fine-tuned results. The fine-tuned model (identified with in below Figure 4) produced better results compared to zero-shot inferencing with the pre-trained model. As Audio Flamingo is trained with retrieval and in-context learning, it shows better performance and can use context better than LTU. This shows fine-tuning models on multilingual dialogues enables an audio-understanding LLM to have much stronger dialogue capabilities.

Conclusion

This paper introduces the Multi-Lingual Dialogue Dataset, specifically for multi-turn dialogues, covering a broad spectrum of topics ranging from education, lifestyle, sports, etc. By leveraging a prompting-based approach through few-shot learning, we generate a substantial volume of high-quality dialogues suitable for training and evaluating ASR models. This paper addresses the multilingual aspect of the dialogues and attempts to lay out the flow of how the conversation generated can represent the real world by manipulating the audio generated for pitch, tone, speed, adding random noise, etc. To represent the real world, this paper also addressed ways to add modulations, fillers, and breaks to dialogues generated through LLM, aligning with the emotion of the conversation in the multi-turn dialogue. Although this pipeline addresses the current gap in the audio analytics research field, one limitation is the lack of quality assurance of the LLM-generated conversation. Although we do the cosine similarity to ensure the content generated is like the topic in the prompt, that does not provide the quality and the policy guardrails. The future paper will discuss applying reinforcement learning to self-correct the conversation content generated through LLMs.

References

- S. Ruder, R. Johnson, and P. R. Kumar, “Dialogue datasets for multilingual conversational AI: A survey,” in Proc. Conf. Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), 2020, pp. 1–10.

- L. M. Rojas-Barahona and P. A. Perez, “Universal dialogue state tracking with a pretrained language model,” in Proc. Conf. Natural Language Learning (CoNLL), 2020, pp. 65–75.

- Y. Ji, D. H. Kim, and D. Lee, “Cross-lingual transfer learning for dialogue generation,” in Proc. Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), 2019, pp. 1124–1135.

- J. Tiedemann and S. Thottingal, “OPUS-MT: A massive multilingual machine translation system,” in Proc. Workshop on Neural Generation and Translation (WNGT), 2020, pp. 19–23.

- J. Devlin, M.-W. Chang, K. Lee, and K. Toutanova, “BERT: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding,” in Proc. NAACL-HLT, 2019, pp. 4171–4186.

- C. Raffel, N. Shazeer, A. Roberts, et al., “T5: Exploring the limits of transfer learning with a unified text-to-text transformer,” in Proc. Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), 2020, pp. 4171–4186.

- L. Li, Y. Song, Z. Wang, et al., “Building multilingual dialogue systems with pretrained language models,” in Proc. Int. Conf. Learning Representations (ICLR), 2020, pp. 125–136.

- Y. Zhang, S. Chen, and X. Zeng, “Towards multilingual text generation for dialogue systems,” in Proc. Int. Conf. Computational Linguistics (COLING), 2020, pp. 2205–2214.

- R. Singh, D. N. D. M., and T. K. Chakraborty, “Exploring multilingual conversational agents: Challenges and approaches,” in Proc. Workshop on Multilingual Natural Language Processing (MLNLP), 2020, pp. 34–42.

- X. Mei, C. Meng, H. Liu, Q. Kong, T. Ko, C. Zhao, M. D. Plumbley, Y. Zou, and W. Wang, “Wavcaps: A ChatGPT-assisted weakly-labelled audio captioning dataset for audio-language multimodal research,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.17395, 2023.

- A. Radford, J. W. Kim, T. Xu, G. Brockman, C. McLeavey, and I. Sutskever, “Robust speech recognition via large-scale weak supervision,” in Proc. Int. Conf. Machine Learning (ICML), 2023, pp. 28492–28518.

- C. D. Kim, B. Kim, H. Lee, and G. Kim, “Audiocaps: Generating captions for audios in the wild,” in Proc. Conf. North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (NAACL-HLT), 2019, pp. 119–132.

- Y. Gong, S. Khurana, L. Karlinsky, and J. Glass, “Whisper-at: Noise-robust automatic speech recognizers are also strong general audio event taggers,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.03183, 2023.

- S. Deshmukh, B. Elizalde, R. Singh, and H. Wang, “Pengi: An audio language model for audio tasks,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.11834, 2023.

- Y. Chu, J. Xu, X. Zhou, Q. Yang, S. Zhang, Z. Yan, C. Zhou, and J. Zhou, “Qwen-audio: Advancing universal audio understanding via unified large-scale audio-language models,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.07919, 2023.

- Y. Gong, H. Luo, A. H. Liu, L. Karlinsky, and J. Glass, “Listen, think, and understand,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.10790, 2023.

- S. Liu, A. S. Hussain, C. Sun, and Y. Shan, “Music understanding llama: Advancing text-to-music generation with question answering and captioning,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.11276, 2023.

- A.-M. Oncescu, A. Koepke, J. F. Henriques, Z. Akata, and S. Albanie, “Audio retrieval with natural language queries,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2105.02192, 2021.

- R. Huang, M. Li, D. Yang, J. Shi, X. Chang, Z. Ye, Y. Wu, Z. Hong, J. Huang, J. Liu, et al., “Audiogpt: Understanding and generating speech, music, sound, and talking head,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.12995, 2023.

- L. Salewski, S. Fauth, A. Koepke, and Z. Akata, “Zero-shot audio captioning with audio-language model guidance and audio context keywords,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.08396, 2023.

- A. Agostinelli, T. I. Denk, Z. Borsos, J. Engel, M. Verzetti, A. Caillon, Q. Huang, A. Jansen, A. Roberts, M. Tagliasacchi, et al., “Musiclm: Generating music from text,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2301.11325, 2023.

- E. Fonseca, X. Favory, J. Pons, F. Font, and X. Serra, “Fsd50k: an open dataset of human-labeled sound events,” IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio, Speech, and Language Processing, vol. 30, pp. 829–852, 2021.

- H. Touvron, L. Martin, K. Stone, P. Albert, A. Almahairi, Y. Babaei, N. Bashlykov, S. Batra, P. Bhargava, S. Bhosale, et al., “Llama 2: Open foundation and fine-tuned chat models,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.09288, 2023.

- J. Achiam, S. Adler, S. Agarwal, L. Ahmad, I. Akkaya, F. L. Aleman, D. Almeida, J. Altenschmidt, S. Altman, S. Anadkat, et al., “GPT-4 technical report,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.08774, 2023.

- A. Adigwe, N. Tits, K. E. Haddad, S. Ostadabbas, and T. Dutoit, “The emotional voices database: Towards controlling the emotion dimension in voice generation systems,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1806.09514, 2018.

- B. Peng, C. Li, P. He, M. Galley, and J. Gao, “Instruction tuning with GPT-4,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.03277, 2023.

- P. K. Rubenstein, C. Asawaroengchai, D. D. Nguyen, A. Bapna, Z. Borsos, F. d. C. Quitry, P. Chen, D. E. Badawy, W. Han, E. Kharitonov, et al., “Audiopalm: A large language model that can speak and listen,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.12925, 2023.

- Z. Kong, A. Goel, R. Badlani, W. Ping, R. Valle, and B. Catanzaro, “Audio Flamingo: A novel audio language model with few-shot learning and dialogue abilities,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.01831, 2024.

- B. Elizalde, S. Deshmukh, and H. Wang, “Natural language supervision for general-purpose audio representations,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.05767, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2309.05767.

- J. Gardner, S. Durand, D. Stoller, and R. M. Bittner, “Llark: A multimodal foundation model for music,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.07160, 2023.

- S. Lipping, P. Sudarsanam, K. Drossos, and T. Virtanen, “Clotho-AQA: A crowdsourced dataset for audio question answering,” in Proc. 30th Eur. Signal Process. Conf. (EUSIPCO), 2022, pp. 1140–1144.

- Z. Yang, W. Ping, Z. Liu, V. Korthikanti, W. Nie, D.-A. Huang, L. Fan, Z. Yu, S. Lan, B. Li, et al., “Re-ViLM: Retrieval-augmented visual language model for zero and few-shot image captioning,” in Proc. Conf. Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), 2023.

- H. Liu, C. Li, Q. Wu, and Y. J. Lee, “Visual instruction tuning,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.08485, 2023.

- J.-B. Alayrac, J. Donahue, P. Luc, A. Miech, I. Barr, Y. Hasson, K. Lenc, A. Mensch, K. Millican, M. Reynolds, et al., “Flamingo: A visual language model for few-shot learning,” in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), vol. 35, pp. 23716–23736, 2022.

- H. Wang, H. Wu, Z. He, L. Huang, and K. W. Church, “Progress in machine translation,” Engineering, vol. 18, pp. 143–153, 2022.

- W. S. El-Kassas, C. R. Salama, A. A. Rafea, and H. K. Mohamed, “Automatic text summarization: A comprehensive survey,” Expert Systems with Applications, vol. 165, p. 113679, 2021.

- R. Luo, Z. Zhao, M. Yang, J. Dong, M. Qiu, P. Lu, T. Wang, and Z. Wei, “Valley: Video assistant with large language model enhanced ability,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.07207, 2023.

- C. Lyu, M. Wu, L. Wang, X. Huang, B. Liu, Z. Du, S. Shi, and Z. Tu, “Macaw-LLM: Multi-modal language modeling with image, audio, video, and text integration,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.09093, 2023.

- M. Maaz, H. Rasheed, S. Khan, and F. S. Khan, “Video-ChatGPT: Towards detailed video understanding via large vision and language models,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.05424, 2023.

- H. Cao, D. G. Cooper, M. K. Keutmann, R. C. Gur, A. Nenkova, and R. Verma, “CREMA-D: Crowd-sourced emotional multimodal actors dataset,” IEEE Trans. Affective Computing, vol. 5, no. 4, pp. 377–390, 2014.

- C. Busso, M. Bulut, C.-C. Lee, A. Kazemzadeh, E. Mower, S. Kim, J. N. Chang, S. Lee, and S. S. Narayanan, “IEMOCAP: Interactive emotional dyadic motion capture database,” Lang. Resources and Evaluation, vol. 42, pp. 335–359, 2008.

- P. Barros, N. Churamani, E. Lakomkin, H. Siqueira, A. Sutherland, and S. Wermter, “The OMG-Emotion behavior dataset,” in Proc. Int. Joint Conf. Neural Networks (IJCNN), 2018, pp. 1–7.

- Z. Rafii, A. Liutkus, F.-R. Stöter, S. I. Mimilakis, and R. Bittner, “MUSDB18-HQ: An uncompressed version of MUSDB18,” Aug. 2019. [Online]. Available: . [CrossRef]

- S. Hershey, D. P. Ellis, E. Fonseca, A. Jansen, C. Liu, R. C. Moore, and M. Plakal, “The benefit of temporally strong labels in audio event classification,” in Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), 2021, pp. 366–370.

- Y. Wu, K. Chen, T. Zhang, Y. Hui, T. Berg-Kirkpatrick, and S. Dubnov, “Large-scale contrastive language-audio pretraining with feature fusion and keyword-to-caption augmentation,” in Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), 2023, pp. 1–5.

- R. Vedantam, C. Lawrence Zitnick, and D. Parikh, “CIDEr: Consensus-based image description evaluation,” in Proc. IEEE Conf. Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2015, pp. 4566–4575.

- K. Papineni, S. Roukos, T. Ward, and W.-J. Zhu, “BLEU: A method for automatic evaluation of machine translation,” in Proc. 40th Annu. Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL), 2002, pp. 311–318.

- C.-Y. Lin, “ROUGE: A package for automatic evaluation of summaries,” in Proc. Text Summarization Branches Out, 2004, pp. 74–81.

- V. Pendyala, R. Raja, A. Vats, R. Para, D. Krishnamoorthy, U. Kumar, S. R. Narra, S. Bharadwaj, D. Nagasubramanian, P. Roy, D. Roy, D. Pant, and S. Lohani, “The Cognitive Nexus, Vol. 1, Issue 2: Advances in AI Methodology, Infrastructure, and Governance,” IEEE Computational Intelligence Society, Santa Clara Valley Chapter, Oct. 2025. Magazine issue editorial. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/396179773_The_Cognitive_Nexus_Vol_1_Issue_2_Advances_in_AI_Methodology_Infrastructure_and_Governance.

- V. Pendyala, R. Raja, A. Vats, N. Krishnan, L. Yerra, A. Kar, N. Kalu-Mba, M. Venkatram, and S. R. Bolla, “The Cognitive Nexus, Vol. 1, Issue 1: Computational Intelligence for Collaboration, Vision–Language Reasoning, and Resilient Infrastructures,” IEEE Computational Intelligence Society, Santa Clara Valley Chapter, July 2025. Magazine issue editorial. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/396179779_The_Cognitive_Nexus_Vol_1_Issue_1_Computational_Intelligence_for_Collaboration_Vision-Language_Reasoning_and_Resilient_Infrastructures.

- V. Pendyala, R. Raja, A. Vats, R. Para, D. Krishnamoorthy, U. Kumar, S. R. Narra, S. Bharadwaj, D. Nagasubramanian, P. Roy, D. Roy, D. Pant, and S. Lohani, “The Cognitive Nexus, Vol. 1, Issue 2: Advances in AI Methodology, Infrastructure, and Governance,” Preprints, Oct. 2025. DOI: 10.20944/preprints202510.0091.v1. Available at: . [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).