1. Introduction

Much research and policy attention has been paid over time to the systematic differences in how various gender groups are represented and treated in society and by cultural industries such as the media, advertising and films, among others. This accounts for the amount of studies and public opinion on hypermasculinity (Ejem 2022; Alam 2022; Matos 2024), gender pay gap (Halim et al. 2023), gender stereotypes (Heilman et al. 2024), woman objectification (Ejem et al. 2022), gendered vulnerabilities to disasters (Ejem et al. 2025) and became the core of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 5 and 10. More recently, researchers have conceptualized what they call the gender say gap, which is the outcome of persistent oppression from a dominant voice shrouding over the muffled voices of the less powerful through various silencing treatments (Mason 2022; Yih 2022). Gender say gap has been used by some researchers to refer to the silence of, and silencing of (mostly) woman voices, ideas and insights by society - or those of the less powerful gender by the dominant one (Mason 2022; Sampson 2018).

In patriarchal societies, gender say gap or gender silencing manifests in the invisibility of women and minority gender groups as expert authorities in business and public life (Mason, 2022), lack of confidence by mostly women to report gender-based violence, underrepresentation of women at senior level in boardrooms, giving women less speaking time than men in the media, and other manifestations of systematic silencing. In patriarchal societies, women’s voices are suppressed, while at the same time, there are those who are coopted in support of the system of power.

The scope of the Global Gender Index Gap covers the disparity that exists in four significant domains: health, education, economic participation and opportunity, and politics (Gutiérrez-Martínez et al. 2021) but the media is an important aspect in the pursuit of global gender equality (Sharma et al. 2021). The mainstream media has been a more profound aspect in the Global Gender Index Gap because they have been severally accused of promoting systematic differences in gender treatment and portrayal all over the world (Van der Pas and Aaldering 2020; Asr et al. 2021; Santoniccolo et al. 2023). Also, cultures and societies are heavily influenced by visual depictions and representations, which are primarily shaped and presented by the mass media (Anyanwu et al. 2023). It is, therefore, believed that treating gender representation in the media with fairness and ethical consideration should be viewed as a professional goal, akin to upholding principles of accuracy, fairness, and honesty (White 2009).

Content analyses across countries and decades have consistently proven that TV reinforces gender stereotypes through the way they depict men as dominant, authoritative while showing women as dependent, nurturing and primarily concerned with domestic roles (Hermann et al., 2021; Gjylbegaj & Radwan, 2025). Research has also shown that there is also gender disparities in the media in the roles and positions people occupy and the privileges they enjoy (Matole et al., 2024; Ross & Padovani, 2019). In that vein, researchers have identified the contrast between men and women concerning their salaries, participation, and visibility in the media workplace (Harris, 2017), having fewer women as news sources in the media, as well as fewer women news anchors, reporters, and boardroom members; and when you have them in those roles mentioned, in what rung of the scalar chain do they sit on? What kind of issues do the woman presenters present or report about?

Research evidence shows that the statistical representation of women in journalism compared to men in both news collecting and content has become the main focus of gender approaches to media studies ((Matole et al., 2024; Ross & Padovani, 2019; Collins, 2011; Ozer, 2023). Similarly, there is also evidence that women are given less speaking time than men in the media with research by Institut National de l’Audiovisuel in France showing that women occupy one-third of the speaking time on television and radio (Doukhan et al. 2018), and 44.4% in the USA (Statista 2024). While these have been reported in many studies as a global challenge (Harris 2017; Mason, 2022), the characteristics of a patriarchal society make them even more palpable because of the structural inequalities in these societies. Early evidence already suggests that women were largely marginalized and underrepresented in African media, almost to the point of being invisible (Gross 2023).

Two West African countries that have been noted for their strong patriarchal traditions include Ghana and Nigeria (Bawa et al., 2012), even though their specific manifestations, regional variations and intensity are said to differ due to ethnic, cultural and historical factors. In Ghana, there are cultural, social, and religious factors, leading to rigid gender roles and legitimizing man authority (Sikweyiya et al., 2020). In Northern Ghana, especially, women face significant obstacles to leadership (Adongo et al., 2023). The cultural and social norms in Nigeria entails that traditional gender roles limit women’s autonomy, and this extends to workplace where women face discrimination, limited career advancement and are excluded from leadership roles (Adisa et al., 2019; Nwano & Akhirome-Omonfuegbe, 2024; Imhanrenialena et al., 2024). In the context of media representation, it has been argued that the authority to shape the media and public agenda remains primarily a privilege enjoyed by men in Nigeria (Izunwanne et al. 2020), and in Ghana, despite progress towards gender equality and navigating entrenched system, men continue to dominate key positions in Ghana’s broadcast media (Danso et al., 2025) and there is still mixed picture of progress and stagnation for women in journalism in the country (Yeboah-Banin et al., 2020). Research has shown that while reasonable progress has been made in the recent past to increase women’s visibility in Ghana and Nigerian media and in broader socio-political contexts, they may be sometimes accompanied by constrained agenda-setting, restricted voice, and assimilation into dominant discursive norms (Emwinromwankhoe, 2023; Birdsall & Carmi, 2022; Syawal et al., 2024) – all of which are markers of systematic silencing.

In line with the macro picture and economic-structural dimensions of news system, there are cultural, structural, institutional, technological and economic forces that interact to shape how news is produced, distributed and consumed (Reese, 2019; Schudson, 2002; Knudson, 2008). The macro picture, in particular, posits that the cultural realities in society where journalism operates determines whose voices get amplified and what contents get prioritised, while the economic-structural dimension look at the institutional arrangement and market logics that shape the media system (Flew & Stepnik, 2024; Ryfe, 2021; Knudson, 2008).

This has also been accentuated by Shoemaker and Reese’s hierarchy of influence which describe the micro- and macro-forces that affect news content in an environment (Koroma, 2023). In this study, we are looking at individual level of analysis which include how a demographic feature (gender) may affect content production; routine level of analysis which refers to how power is exercised within the media organisations; and social systems which refers to how media producers reproduce power relations in society (Rodarte & Richardson, 2024; Kwanda & Lin, 2020; Umejei, 2018). Therefore, the units of analysis would include the characteristics of boardroom members of media organisations who make content decisions, news anchors/anchor persons who use their vocal presence to deliver the content and provide perspectives, experts/guests who are invited (or interviewed on news scenes or on the street) by the broadcast stations to provide context to news of the day. These are the people who use their influence and speaking time to control, filter and shape reality, and give saliency to social issues; and those who control these groups control the voice of the media and silence the less visible groups.

From a gender perspective, is there any evidence to suggest that, due to the individual and routine forces in TV organisations and the broader socio-cultural and economic structures in the environment in which the Ghana and Nigeria media systems operate, there is still a systematic silencing of the voices of a certain gender group through skewed composition among those who decide TV content, those who deliver the content and those who provide context to the content with their expertise and opinions? What is the most visible gender among presenters, news editors, management (and directors) in Ghana and Nigeria TV station? What are the cultural, structural, institutional, technological and economic forces that predicate gender representations in Ghana and Nigeria media system? Examining these will help the researcher to understand whether gendered visibility in Ghana and Nigeria media systems arises from deeply entrenched institutional and cultural structures and not merely from isolated instances of bias.

Therefore, the objectives of this research include to:

- a

examine the more visible group gender among presenters, news editors, management (and directors) in Ghana and Nigeria TV station;

- b

know if there is a systematic silencing of the voices of a certain gender group through speaking time given to guests/speakers (including eye witnesses and vox pops);

- c

find out the cultural, structural, institutional, technological and economic forces that predicate gender representations in Ghana and Nigeria media system.

1.2. Theoretical Framework

This work is anchored on the feminist muted theory. Propounded by Shirley and Ed-win Adener in 1968, the theory explains why some groups are silenced in society. It states that there are social hierarchies in society where some groups, usually men, are placed in a more privileged positions than others. The more privileged groups are dominant because they are given more voice than those that are not as privileged, usually the woman and non-binary groups. The dominant group at the top of the social hierarchy holds significant influence over societal communication. It is their dominance that leads to the phenomenon of muteness, meaning the silenced state of marginalised groups because of their lack of power. In patriarchal societies, according to Clemence and Jairos (2011), the dominant group usually consists of men in patriarchal societies, while the muted group usually consist of women who largely occupy lower-level positions in such societies. Those in dominant positions not only control resources but also the communicative structures of society, leading to the systematic muting and under-representation of less privileged voices in both public and institutional spheres – including the media.

While feminist muted theory provides a foundation for understanding gender disparities in media (Jan et al., 2023), this study focuses on examining the persistence and nature of representational inequalities in Nigerian and Ghanaian media, and more broadly across Africa. It highlights the gap in research regarding the structural and cultural factors that reinforce gender silencing within African newsrooms and content production. Projects such as the Global Media Monitoring Project (GMMP) have shown persistent gender imbalances in media staffing and representation in Africa (GMMP, 2020; GMMP, 2025). However, these studies typically do not explain the underlying mechanisms through which these imbalances are maintained within broader social structures.

The recent rise in visibility and influence by women in powerful positions in the world, including Africa (Chitsamatanga, 2023; Ilesanmi, 2018), has been discussed in relation to its implication on feminist muted theory and critiques of media voice (Syawal et al., 2024; Jan et al., 2023). However, there is a consensus in recent scholarship that representation alone does not guarantee gender advancement as elite presence can coexist with structural silencing (Agarwal, 2023). Researchers conclude that formal visibility of women may be sometimes accompanied by constrained substantive influence, restricted voice, and assimilation into dominant discursive norms (Emwinromwankhoe, 2023; Birdsall & Carmi, 2022; Syawal et al., 2024).

The main arguments of this study are to investigate whether gendered silencing occurs in Ghana and Nigeria media at managerial, presentational, and content levels, and explore how these processes are shaped by broader cultural, structural, institutional, technological and economic forces. The study will essentially examine the processes of systematic silencing in these TV stations by investigating who sets agenda, whose knowledge is legitimated and whose opinion is marginalised.

In contrast to the empirical findings of the GMMP, the central argument of this study is to provide a theory-driven analysis by linking feminist muted theory, macro picture and economic-structural dimensions with contemporary media practices in Ghana and Nigeria. By situating recent empirical findings within comparative and historical frames, the study aims to evaluate present-day gender representations in select media and determine whether patterns have changed or persisted over time. Thus, the study seeks to explain and theorize if (and why) the under-representation and muting of women voices continue in African media, using context-specific analysis.

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design

The researcher analysed the gender differences in the compositions of management staff (including directors), news anchors, guests, eye witnesses and vox pops of select TV organisations in West Africa. This was done by:

(a) Content-analysing the websites of the select TV stations and, in some cases, the SignalHire site, an HR analytics, recruiting and benchmarking platform that provides real-time and historical trends on employers’ hiring activities, workforce flows and company climate. This was done to examine the gender differences in the compositions of management staff and news anchors.

(b) Content-analysing news programmes on the YouTube channels of the select TV stations between January and June 2024 to examine the speaking time of man and woman guests, eye witnesses and vox pops. The YouTube channels are part of the stations’ dual-broadcasting system. It is the same content on their traditional stations that they distribute on their YouTube channels to expand read.

Based on Stempel’s (1952) method for sample size selection in content analysis, two constructed weeks were created using ChatGPT-generated randomization. Those 14 days made up the primary research dates that the news programmes on the YouTube channels were examined. Hester and Dougall (2007) explain that at least two constructed weeks are needed to accurately represent online news platforms.

The constructed weeks were as follows:

Week 1

Monday March 12

Tuesday May 7

Wednesday February 14,

Thursday April 1

FridayJune 21

Saturday May 18

Sunday February 25

Week 2:

Monday February 5

Tuesday January 16

Wednesday February 21

Thursday March 14

FridayJanuary 19

Saturday February 24

Sunday March 10

The use of constructed week procedure mitigated the bias that might arise from under- or over-representing some days (Kim et al., 2018). The researcher analysed all the videos of news programmes uploaded on the YouTube channels on those days.

These videos and websites helped to provide insights into whether there is a systematic silencing of any gender group in these media systems, and to infer any non-random reason why a gender group is more visible than the other. This research classified the gender groups as man and woman, in line with the two normative gender categorizations in West Africa societies.

Ghana and Nigeria were studied, being the two largest media markets in West Africa with TV market revenues of 900 million and 192 million US dollars respectively by 2023 (Statista 2023). As seen in

Table 1, three leading TV stations in each of the two countries were studied, summing up to 6 TV stations. The TV ratings were derived from Statista.com, GeoPoll and CANAL+, and were from 2022/23 data. All the TV stations are based in the largest media markets in Ghana and Nigeria – Lagos and Accra, respectively. Other inclusion criteria were that the management and employee lists of the TV stations and their organograms are available on the organizations’ websites; must be private or community news TV stations and the stations must have been in existence for at least 5 years.

Stations that focus on specialised programming such as sports, movies, music, etc. were also excluded.

Coding

The Gender Count Code sheet, designed by the researcher, was used to collect employees’ data from signalhire.com, the organizations’ websites and YouTube channels. Six (6) independent coders, trained onsite by the researchers, coded these online platforms. Each coder was assigned to a TV station.

For the YouTube channels, the coders coded a large 298-hour corpus of news programmes from the 6 stations. The coding was concluded in 41 days.

In view of the objectives of this study, these coders coded members of management staff (management and executive directors) who make decision about the TV offerings; and news anchors, the front-persons who anchor the programmes; and guests, eye witnesses and vox pops, in the news programmes who provide context to news of the day.

The coding process involved accessing the list of employees and managements of the TV Stations from signalhire.com and the organizations’ websites, and sifting through their names and roles, looking for those designated as management (management and executive directors) and news anchors, and entering them into the Gender Count Code sheet. This was followed by identifying their genders where they were obvious, through their accompanying photographs or their brief biographies; otherwise, those names whose genders were not apparent were looked up on LinkedIn.

The coding process also included manually counting the speaking time of man and woman guests, eye witnesses and vox pops on news programmes uploaded on the YouTube channels. This was considered a more exhaustive methodology for counting the number of men and women and the number of minutes that men and women spoke as guests, eye witnesses and vox pops, instead of using automatic descriptors (see Doukhan, et al. 2024)

To test the inter-rater reliability, the Krippendorff’s Alpha coefficient was used. With α = 0.876, it demonstrates high reliability of data coded from the six stations and consistency in the coding and also indicates that the data is not distorted by random differences in judgement.

Data Analysis

In the analysis, percentages were used at the descriptive levels to examine how the man presenters compare with the women. The Chi-square was used to examine the differences in gender distribution across the 6 stations. and T-test was used to compare the speaking time of man and woman guests. All of these enabled the researcher to draw inference on the representation of the gender groups in the select TV stations in Ghana and Nigeria. All the analyses were based on the SPSS.

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Content Analysis

This section presents data from the quantitative content analysis of the channel’s websites, SignalHire website and news programmes on YouTube channels of the 6 stations.

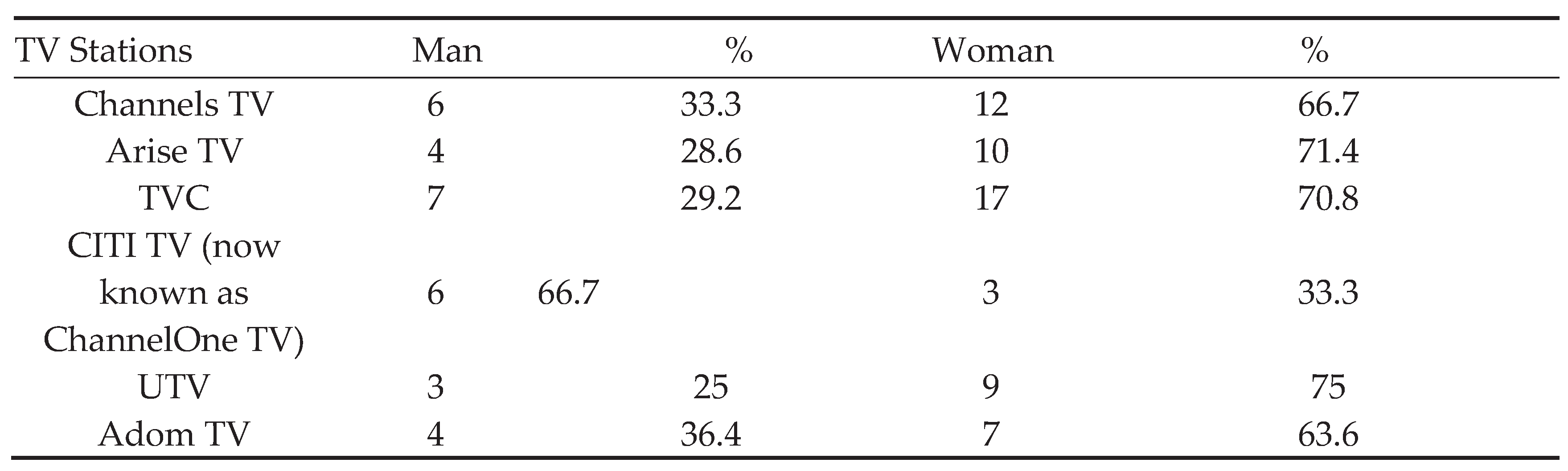

Table 2.

Gender differential analysis of presenters in the select TV stations.

Table 2.

Gender differential analysis of presenters in the select TV stations.

All 6 selected TV stations, except ChannelOne TV, Ghana (33.3%), have significantly more woman presenters than man. This indicates a reverse gender gap in the composition of presenters who deliver the news to the audience in TV stations in Ghana and Nigeria. That is to say, more women seem to be in positions where they use their vocal presence to deliver the content and provide perspectives. But to what extent are they part of the boardroom members of media organisations who make content decisions?

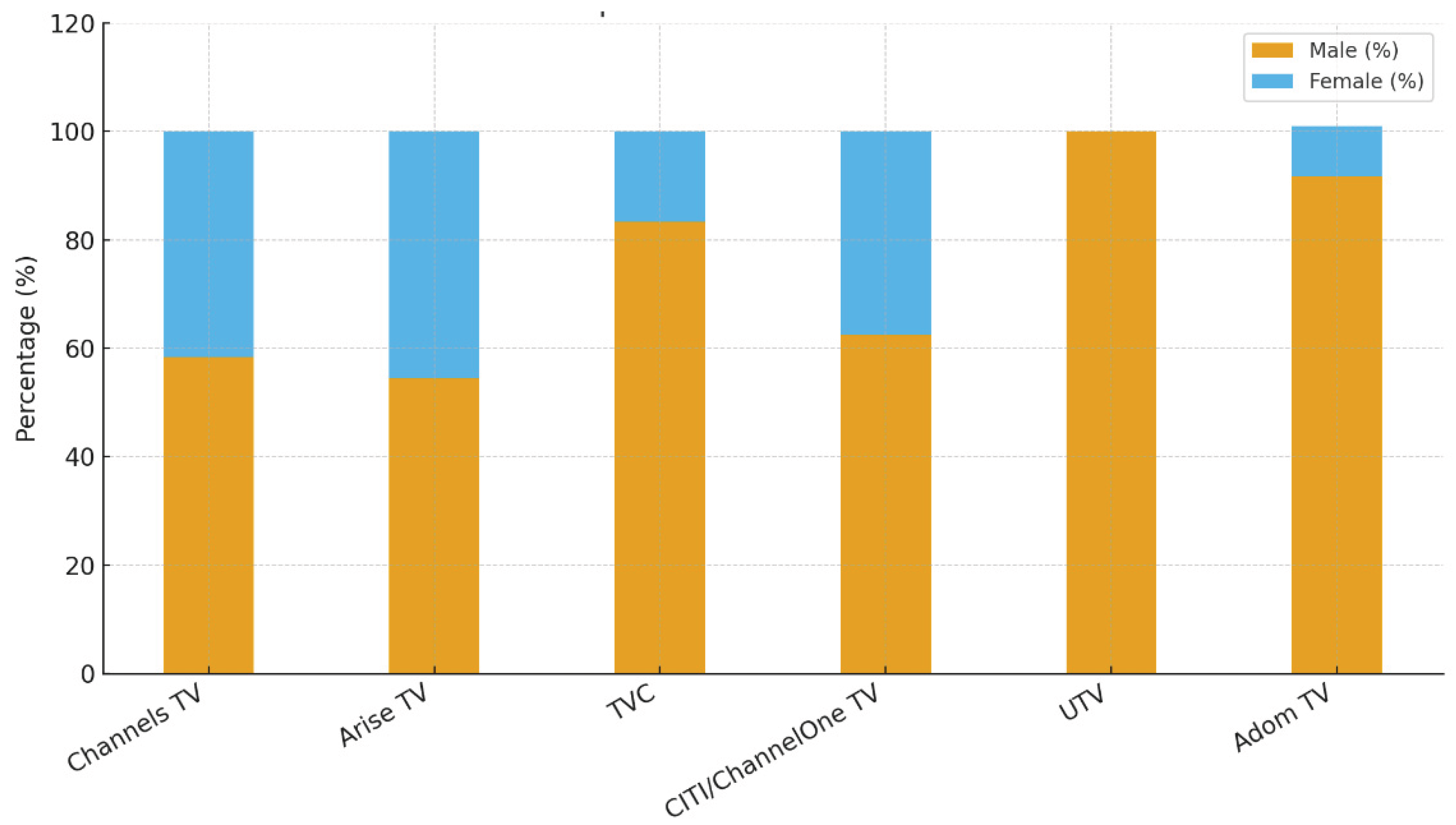

Figure 1 shows that male dominance is consistent among members of management (including executive directors) in the six TV companies, although the intensity varies. While Arise TV (Nigeria) and Channels TV (Nigeria) are closest to parity, UTV (Ghana) has zero women presence, and Adom TV (Ghana) shows near women exclusion. Overall, men make up three-quarter of the total number of management staff (and executive directors) (75.1%), while women make up one-quarter (24.9%).

The Chi-square test of independence was used to examine the differences in gender distribution across the 6 stations. With p < 0.05 [χ²: 95.87; df:5], the results show that the frequencies of man and woman members of management (and executive directors) differ significantly across the TV stations.

The researcher performed a t-test to compare the speaking time of man and woman guests, those who gave eye witness account of events, participants of vox pop and street intercept interviewees in the six TV companies. The test in

Table 3 shows that the speaking time of men (68.383) was higher than the speaking time of women (31.6). With p < 0.05, the tests showed that there was a significant difference between the speaking time of men and women (t(10) = 12.96957, p = 0.001069).

3.2. Qualitative Content Analysis

Gender differential analysis of news editors in the select TV stations.

All three TV stations in Ghana (Adom TV, UTV and ChannelOne TV) have woman news editors. The women make up a less significant proportion of news editors in the three TV stations selected from Nigeria. There is a woman news editor for TVC, designated as the Director of News. Channels TV has two man news editors and a woman Deputy News Editor. While News Editor position is not clearly distinguishable in available sources in Arise TV, the role is performed by a man who occupies the position of the Director of News and three men who serve as Deputy Directors of News.

Recent scholarship on Muted Group Theory and feminist critiques of media voice highlights the limits of numerical representation. While evidence in this study shows that 4 (66.7%) of the 6 TV stations have woman news editors, muted group research findings insist that representation alone does not guarantee gender advancement as elite presence can coexist with structural silencing (Birdsall & Carmi, 2022; Syawal et al., 2024).

Gender differential analysis of heads of the selected TV organizations.

All 6 stations except TVC (Nigeria) have Chairmen/CEO who are men. They include Samuel Attah-Mensah (ChannelOne TV, Ghana), Nduka Obaigbena (Arise TV), John Momoh (Channels TV, Nigeria), Kwasi Twum (Adom TV, Ghana), Osei Kwame (UTV, Ghana; Ernest Ofori Sarpong, the co-founder). The only outlier is TVC (Victoria Ajayi).

The implication of the information above is that men provide governance and oversight, and create a vital dynamic that shapes the overall success of most TV organisations in Ghana and Nigeria. Besides many other responsibilities, these CEOs develop content strategies and operational models (Sariol & Abebe, 2017), and the Chairmen work with the CEOs to ensure strategic decisions and ensure accountability (Shen, 2019; Bromiley & Rau, 2016). Almost all of these are done by men, meaning that men occupy very powerful positions in these stations, shape content strategies and operational models, and ensure strategic decisions and accountability.

4. Discussion

The study found that there were more women presenters than men in the select TV stations in Ghana and Nigeria, even though the proportion varies according to the station. All 6 selected TV stations, except ChannelOne TV, Ghana (33.3%), have significantly more woman presenters than man. It can be inferred from this evidence that there is a significant increase in the number of woman journalists in West African newsrooms and it indicates a reverse gender gap in the composition of presenters who deliver the news to the audience in TV stations in Ghana and Nigeria. More women seem to be in positions where they use their vocal presence to deliver the content and provide perspectives. This also confirms the evidence in recent bodies of literature that strides continue to be made towards gender parity in the news reporter role (GMMP, 2025; GMMP, 2020). For instance, in a 2020 study, women outnumbered men as presenters by 54% (GMMP, 2020).

This finding also implies that the gender differentials of presenters in a media system is not shaped by broader sociopolitical structures nor predicated on gender norms in society. For instance, one would have thought that due to the patriarchal structures overtly embedded and reinforced within African societies, the proportion of man dominance is expected to be highest in all facets of the media (Akurugu et al., 2022; Govender and Muringa, 2025; Ncube 2021). On the contrary, there seems to be more male dominance in TV anchors in countries where patriarchy is less overtly institutionalized than in many Africa contexts, such as the UK and the US (Ng’eno, 2017; Ryan, 2019).

A study by Watson’s (2020) on gender distribution of evening broadcast TV anchors on selected networks in the United States shows that men reported almost twice as much as women on NBC, ABC, CBS and PBS. Similarly, Nasruddin (2021) confirmed that men still dominate in the news industry but showed that South Africa is leading the US, UK and India in gender parity in the newsrooms with women consisting of 49% journalists and 42% in Kenya. Among the countries studied in different continents, the study showed that South Africa led in gender parity in the newsrooms with women consisting of 49% journalists, followed by the UK (47%), US (42-45%), Kenya (42%) and India (28%). The implication is that, contrary to expectation, the gender differentials in newsrooms are not predicated on gender norms in society.

However, since presence is not a sole marker of equity, this evidence has to be considered in the light of subsequent findings on the structural powers in these TV stations, and other indicators such as agenda-setting, authority, framing, representation, and the patterns and consistency of these markers across different stations (Jungherr et al., 2019). In the absence of other markers of equity, any rise in female representation as TV anchors in Ghana and Nigeria aligns with the core of neoliberal feminism, which entails that these women achieved these positions through self-empowerment and not because of any legal and institutional factors that drive equality in these societies (Bennett, 2024; Akinbobola, 2019).

To what extent are women part of the boardroom members of these TV organisations, who make content decisions? Findings in this study shows that male dominance is consistent among members of management (including executive directors) in the six TV companies, although the intensity varies. While Arise TV (Nigeria) and Channels TV (Nigeria) are closest to parity, UTV (Ghana) has zero women presence, and Adom TV (Ghana) shows near women exclusion. Overall, men make up three-quarter of the total number of management staff (and executive directors) (75.1%), while women make up one-quarter (24.9%). The Chi-square test of independence shows that, with p < 0.05 [χ²: 95.87; df:5], the frequencies of man and woman members of management (and executive directors) differ significantly across the TV stations.

This clearly shows the power relations between men and women in the media, and how men hold an enormous majority of power positions in these media houses. The implication is that men set the most media agenda and make the most boardroom decision in the media organisations. Relating to the previous findings about gender differentials in newsrooms, this finding corroborates evidence in literature that while women participation in newsrooms has increased in the global news media (Byerly 2016), they remain underrepresented in most top positions (Adams et al. 2022). Therefore, beyond making up more news anchors, the women in Ghana and Nigeria TV were not involved in decision-making and agenda of activities.

This support the claims that despite the democratic change, economic liberalization and intensified advocacy for women’s equality in Ghana, there is no significant improvements in the status of women in the media industries (Gadzekpo, 2023), and few women own media, or occupy top governance and management positions (Byerly 2011). Gadzekpo (2023) attributes that to the proverbial glass ceiling that continues to perpetuate gross gender inequalities in decision-making positions in the Ghanaian media.

To provide further context to the male dominance among members of management in the six TV companies, it was found that all 6 stations except TVC (Nigeria) have Chairmen/CEO who are men. They include Samuel Attah-Mensah (ChannelOne TV, Ghana), Nduka Obaigbena (Arise TV), John Momoh (Channels TV, Nigeria), Kwasi Twum (Adom TV, Ghana), Osei Kwame (UTV, Ghana; Ernest Ofori Sarpong, the co-founder). The only outlier is TVC (Victoria Ajayi).

The reinforces that finding that men provide governance and oversight, and create a vital dynamic that shapes the overall success of most TV organisations in Ghana and Nigeria. Besides many other responsibilities, these CEOs develop content strategies and operational models (Sariol & Abebe, 2017), and the Chairmen work with the CEOs to ensure strategic decisions and ensure accountability (Shen, 2019; Bromiley & Rau, 2016). Almost all of these are done by men, meaning that men occupy very powerful positions in these stations, shape content strategies and operational models, and ensure strategic decisions and accountability. To situate this within the discussion on systematic silencing, researchers have largely looked beyond presence to various markers of silencing, including structural power (who owns and controls the media), who gets to speak (agenda-setting), whose knowledge is authoritative, whose voices are presented (framing), who gets visibility (representation), and patterns and consistency across different stations (Jungherr et al., 2019; Roslyng & Dindler, 2023; Scheufele & Tewksbury, 2007; Entman, 2007). Most of these variables are consistent with the influence and power of the leadership of the TV stations.

Ownership and leadership predicate the power dynamics of every organisation, including TV stations. According to the economic-structural dimensions of news systems, ownership structure determines the institutional arrangement and market logics that shape the media system (Flew & Stepnik, 2024; Ryfe, 2021; Knudson, 2008). This highlights why news and media representations are not only cultural or social expressions but also embedded within broader economic structures within organisations. More so, there is a hierarchy of factors, unrelated to cultural values, that influence those owners and leaders in distributing and exercising power.

Yeboah-Banin et al.’s (2024) assertion that progress is visible in the status of women is only evidenced in the gender differentials of news editors in the select TV stations in Ghana and Nigeria. The data shows that all three TV stations in Ghana (Adom TV, UTV and ChannelOne TV) have woman news editors. The women make up a less significant proportion of news editors in the three TV stations selected from Nigeria. There is a woman news editor for TVC, designated as the Director of News. Channels TV has two man news editors and a woman Deputy News Editor. While News Editor position is not clearly distinguishable in available sources in Arise TV, the role is performed by a man who occupies the position of the Director of News and three men who serve as Deputy Directors of News.

This is, however, an important achievement in the visibility of women in Ghana and Nigeria as news editors are very influential in TV broadcasting. They select and display information, and thus contribute to shaping public views about issues (Alphonsus et al., 2022), occupying the position of gatekeepers (Conte, 2022). Those who occupy the position of news editors are profoundly influential in, not only shaping public perception, but also significant in driving visibility or reversing mutedness.

In relation to recent scholarship on Muted Group Theory and feminist critiques of media voice which highlights the limits of numerical representation, while evidence in this study shows that 4 (66.7%) of the 6 TV stations have woman news editors, muted group research findings insist that representation alone does not guarantee gender advancement as elite presence can coexist with structural silencing (Birdsall & Carmi, 2022; Syawal et al., 2024). Also, from a critical feminist theory perspective, there are still institutional and discursive mechanisms that maintain mutedness and constrain women’s substantive influence even where they occupy visible positions such as news editors in these TV stations, such as the customary and legal structure in Ghana and Nigeria legitimize women’s subordinate status and restrict autonomy (Akurugu et al., 2022; Gyan & Mfoafo-M’Carthy, 2021), gendered expectations (Madsen, 2018), colonial and neoliberal legacies of having men as key media figures (Bawafaa, 2023), dominant discourses in politics and media revolve round men (Nartey, 2023), and there is evidence that discursive strategies have been used to exclude intersectional or radical feminist voice (Nartey, 2023).

While women occupy news editorial positions, which goes contrary to recent findings in related studies (Gumede, 2023; GMMP, 2020; GMMP, 2025), leadership in these media houses remains overwhelmingly male, reinforcing the glass ceiling effect (Babic & Hansez, 2021; Neugart & Zaharieva, 2025). Having men occupy the Chairmen/CEO in all 6 stations except TVC (Nigeria), it means that final editorial power, governance and agenda-setting authority are often monopolized by men, thus reflecting broader patriarchal political cultures in Ghana and Nigeria. With women occupying news editor positions and large presentational roles in these TV stations while men occupy most of the leadership roles, it means that progress is being made in vertical segregation in TV stations but the progress remains tokenistic because these women, as many as they might be, do not have the structural support to transform the TV newsroom culture. Moreover, the neo-liberal economic pressures in African newsrooms undermine sustained effects towards gender equity (Lewis, 2019).

This entails that the women who work in West African TV are still not empowered to give them abilities to promote balance in influence and gender representations. It is the empowerment of women that enhances their image in the audiovisual landscape (UNESCO 2017) and makes the media a suitable ground for expressions and claims (Pavarala et al., 2006). This also mirrors the dramatically ironic conclusion that the population of women in the media is undeniably more than the men yet women remain underrepresented in positions of power (Ammerman and Groysberg 2021).

The 1995 World Conference on Women in Beijing, China, recognising the centrality of the media in advancing gender equality (which would later become the target of SDGs 5 and 10), proposed increasing women’s participation in and access to expression and decision making in and through the media; and promoting a balanced and non-stereotypical portrayal of women in the media (Deehring and Belsey-Priebe 2021). Based on evidence from this research, it can be concluded that the women’s participation in news delivery might have increased in West African TV, but access to expression and decision making in and through the media leave a lot to be imagined. This contradicts the evidence in research that there is a rise in women leadership in the media (Arguedes et al. 2024; Onalaja and Otokiti 2022)

The researcher performed a t-test to compare the speaking time of man and woman guests, those who gave eye witness account of events, participants of vox pop and street intercept interviewees in the six TV companies. The test shows that the speaking time of men (68.383) was higher than the speaking time of women (31.6). With p < 0.05, the tests showed that there was a significant difference between the speaking time of men and women (t(10) = 12.96957, p = 0.001069).

The speaking time extended to guests, vox pops or eyewitnesses. This seem to suggest the assertion in literature that the presence of women as decision makers in the media influence the selection of sources (Beckers et al., 2024). The woman members of the board are expected to be more conscious of their underrepresentation and should be, therefore, more prone to selecting woman sources (Niemi and Pitkänen 2017). True to that assertion, with fewer number of women who occupy elite roles in the media organisations, the proportion of women who participate as guests, eyewitnesses or vox pops are fewer. The Global Media Monitoring Project (2020) corroborated that women remain underrepresented in elite roles, far less likely to be interviewed as experts, but they score better in less active roles such as vox pops or eyewitnesses.

There seems to a widespread evidence that on average, men spoke more than women, in the many channels and nations studied. The Institut National de l’Audiovisuel’s study shows that the amount of speaking time varies among TV channels but, on average, men spoke more than women, no matter the channel studied (Doukhan et al., 2018) understood that the speaking time of women in French TV and radio is evolving, but men have significantly higher speaking time. In a study by UNESCO (2018), only 10% of new stories focus on women and they make up only 20% of experts or spokespeople interviewed.

This is accentuated by GMMP (2025) which asserted that historical findings indicate that after a slow and steady rise in women’s share of visibility and voice in the news, progress began flatlining in 2010, a trend that continues to date. Of the people heard, seen and spoken about in print and broadcast news, only 26% are women.

5. Conclusions

While there is a significant number of woman TV presenters in West Africa TV channels, their underrepresentation in boardrooms and in speaking time is very conspicuous and underlining. Women have made monumental achievements in recent history, but their representation in the media remain considerably low to that of their men counterparts. The implication of underrepresenting women’s voices is that it strengthens stereotypes and denies them the chance to be recognised for their expertise and knowledge. More so, systemic biases and stereotypes can impact hiring and promotion decision and can lead to professional segregation and limited opportunity for career mobility. The major contribution of this study is that the rise in the proportion of woman presenters in the West Africa TV channels studied is not sufficient to challenge gender stereotypes in patriarchal societies. The media and the broader society where they exist must tackle those institutional and discursive mechanisms that maintain mutedness and constrain women’s substantive influence even where they occupy visible positions in the TV stations. Therefore, addressing these mechanisms will help to achieve gender equality and create a diverse and inclusive media landscape.

Funding

This research received no funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s)

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TVC |

TV Continental |

| UTV |

United Television |

References

- Adams, K., Selva, M., & Nielsen, R. (2022). Women and leadership in the news media 2022: Evidence from 12 markets. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

- Adisa, T., Abdulraheem, I., & Isiaka, S. (2019). Patriarchal hegemony. Gender in Management: An International Journal. https://doi.org/10.1108/GM-07-2018-0095.

- Adongo, A., Dapaah, J., & Azumah, F. (2023). Gender and leadership positions: understanding women’s experiences and challenges in patriarchal societies in Northern Ghana. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijssp-02-2023-0028.

- Agarwal, B. (2023). Gender, presence and representation: Can presence alone make for effective representation?. Social change, 53(1), pp.34-50. https://doi.org/10.1177/00490857231158178.

- Akinbobola, Y., (2019). Neoliberal feminism in Africa. Soundings, 71(71), pp.50-61.

- Akurugu, C., Dery, I., & Bata, P. (2022). Marriage, bridewealth and power: critical reflections on women’s autonomy across settings in Africa. Evolutionary Human Sciences, 4. https://doi.org/10.1017/ehs.2022.27.

- Alam, S. (2022). Media and hegemonic masculinity:(De) construction and representation. South India Journal of Social Sciences, 20(1), 122-131.

- Alphonsus, U. C., Etumnu, E. W., Talabi, F. O., Fadeyi, I. O., Aiyesimoju, A. B., Apuke, O. D., & Celestine, G. V. (2022). Journalism and reportage of insecurity: Newspaper and television coverage of banditry activities in Northern Nigeria. Newspaper Research Journal. https://doi.org/10.1177/07395329221112393.

- Ammerman, C., & Groysberg, B. (2021). How to close the gender gap. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2021/05/how-to-close-the-gender-gap (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Anyanwu, B.J.C., Ejem, A. A. & Onuoha, I. (2023). Challenges of gender reporting. African Journal of Social and Behavioural Sciences, 13 (1), 15-27.

- Arguedes, A. R., Mukherjee, M. & Nielsen, R. K. (2024). Women and leadership in the news media 2024: Evidence from 12 markets. Retrieved from https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/women-and-leadership-news-media-2024-evidence-12-markets.

- Asr, F. T., Mazraeh, M., Lopes, A., Gautam, V., Gonzales, J., Rao, P., & Taboada, M. (2021). The gender gap tracker: Using natural language processing to measure gender bias in media. PloS one, 16(1), e0245533.

- Babic, A. & Hansez, I. (2021). The glass ceiling for women managers: Antecedents and consequences for work-family interface and well-being at work. Frontiers in psychology, 12, p.618250. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.618250.

- Bawa, S., (2012). Women’s rights and culture in Africa: a dialogue with global patriarchal traditions. Canadian Journal of Development Studies/Revue canadienne d’études du développement, 33(1), pp.90-105.

- Bawafaa, E. (2023). Marginalization and women’s healthcare in Ghana: Incorporating colonial origins, unveiling women’s knowledge, and empowering voices.. Nursing inquiry, e12614. https://doi.org/10.1111/nin.12614.

- Beckers, K., Aelst, P. V., & Swert, K. D. (2024). A Long March Toward Equality: Predicting the Presence of Women in Television News. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.1177/10776990231211806.

- Bennett, S.L., (2024). The commodification of feminism—A critical analysis of neoliberal feminist discourse. Studies in Social Science & Humanities, 3(5), pp.47-57.

- Birdsall, C., & Carmi, E. (2022). Feminist avenues for listening in: amplifying silenced histories of media and communication. Women’s History Review, 31(4), 542-560.

- Bromiley, P., & Rau, D. (2016). Social, Behavioral, and Cognitive Influences on Upper Echelons During Strategy Process. Journal of Management, 42, 174 - 202. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206315617240.

- Byerly, C. M. (2016). The Palgrave international handbook of women and journalism. Palgrave.

- Chitsamatanga, B.B. (2023). Increasing Female Visibility in Leadership Positions by Dismantling Male Hegemony in Zimbabwean State Universities. Gender and Behaviour, 21(3), pp.21940-21951.

- Clemence, R., & Jairos, G. (2011). The third sex: A paradox of patriarchal oppression of the weaker man. Journal of English and Literature, 2(3), 60-67.

- Collins, R. (2011). Content Analysis of Gender Roles in Media: Where Are We Now and Where Should We Go?. Sex Roles, 64, 290-298. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11199-010-9929-5.

- Conte, A. (2022). Death of the daily news: How citizen gatekeepers can save local journalism. University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Danso, S., Appiah-Adjei, G., & Adjin-Tettey, T. D. (2025). Vertical representation of gender in the Ghanaian broadcast media. Feminist Media Studies, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2025.2533879.

- Deehring, M. & Belsey-Priebe, M. (2021). Beyond Beijing: Using the news media to advance women, peace and security in Qatar. The Journey to Gender Equality: Mapping the implementation of the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action (Book). ISBN: 978-9930-542-24-8. https://www.upeace.org/pages/the-journey-to-gender-equality. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3880670.

- Doukhan, D., Dodson, L., Conan, M., Pelloin, V., Clamouse, A., Lepape, M.,... & Coulomb-Gully, M. (2024). Gender representation in TV and radio: Automatic information extraction methods versus manual analyses. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.10316.

- Doukhan, D., Poels, G., Rezgui, Z., & Carrive, J. (2018). Describing gender equality in French audiovisual streams with a deep learning approach. VIEW Journal of European Television History and Culture, 7(14), 103-122.

- Ejem, A. A. (2022). Hypermasculinity in Nollywood Films (2015-2017). (Doctoral dissertation, Imo State University). https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.6778193.

- Ejem, A. A. & Ben-Enukora, C. A. (2025). Gendered impacts of 2022 floods on livelihoods and health vulnerability of rural communities in select Southern states in Nigeria. Discover Social Science and Health. 5, 67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44155-025- 00211-7.

- Ejem, A. A., Nwokeocha, I. M., Abba-Father, J. O., Fab-Ukozor, N., & Ibekwe, C. (2022). Sex objects and conquered people? representations of women in Nigerian films in the 21st Century. Qistina: Jurnal Multisciplin Indonesia, 1(2), 48-63.

- Emwinromwankhoe, O. (2023). When Silence Becomes Overstretched: Exploring the Loud Silence in Women’s Struggle for Liberation in Contemporary Nollywood. CINEJ Cinema Journal, 11(2). https://doi.org/10.5195/cinej.2023.470.

- Entman, R.M. (2007). Framing bias: Media in the distribution of power. Journal of communication, 57(1), pp.163-173. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1460-2466.2006.00336.X.

- Flew, T.& Stepnik, A. (2024). The value of news: Aligning economic and social value from an institutional perspective. Media and Communication, 12.https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.7462.

- Gadzekpo, A. (2013). Ghana: Women in Decision-making — New Opportunities, Old Story. In: Byerly, C.M. (eds) The Palgrave International Handbook of Women and Journalism. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137273246_27.

- Gadzekpo, A., (2016). Media and gender socialization. The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Gender and Sexuality Studies, pp.1-5. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118663219.wbegss213.

- Gjylbegaj, V., & Radwan, A. (2025). Portrayal of gender roles in Emirati television dramas: a content analysis. Frontiers in Sociology, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2025.1506875.

- Global Media Monitoring Project. (2020). Who makes the news? 2020 final report. Retrieved from https://whomakesthenews.org/gmmp-2020-final-reports/.

- Global Media Monitoring Project. (2025). GMMP 2025 highlights of findings: Progress on a plateau. https://whomakesthenews.org/gmmp-2025-key-findings.

- Govender, G., & Muringa, T. P. (2025). “Women Will Never Be Equal to Men”: Examining Women Journalists’ Experiences of Patriarchy and Sexism in South Africa. Journalism and Media, 6(1), 27.

- Gross, L. (2023). Invisible in the media. United Nations. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/en/chronicle/article/invisible-media (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Gutiérrez-Martínez, I., Saifuddin, S.M. & Haq, R., (2021). The United Nations gender inequality index. Handbook on diversity and inclusion indices, pp.83-100.

- Gumede, Y. (2023). Women’s voices are missing in the media – including them could generate billions in income. Retrieved from https://acme-ug.org/2023/01/19/womens-voices-are-missing-in-the-media-including-them-could-generate-billions-in-income/.

- Gyan, C., & Mfoafo-M’Carthy, M. (2021). Women’s participation in community development in rural Ghana: The effects of colonialism, neoliberalism, and patriarchy. Community Development, 53, 295 - 308. https://doi.org/10.1080/15575330.2021.1959362.

- Halim, U. A., Qureshi, A., Dayaji, S. A., Ahmad, S., Qureshi, M. K., Hadi, S., & Younis, F. (2023). Orthopaedics and the gender pay gap: a systematic review. The Surgeon, 21(5), 301-307.

- Harris, B. (2017). November 1. What is the gender gap (and why is it getting wider)? World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2017/11/the-gender-gap-actually-got-worse-in-2017/(accessed on 11 March 2024).

- Hausmann, R., Tyson, L. D., Bekhouche, Y., & Zahidi, S. (2012). The global gender gap index 2012. The Global Gender Gap Report, 2012, 3-27.

- Heilman, M. E., Caleo, S., & Manzi, F. (2024). Women at work: pathways from gender stereotypes to gender bias and discrimination. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 11(1), 165-192.

- Hermann, E., Morgan, M., & Shanahan, J. (2021). Social change, cultural resistance: a meta-analysis of the influence of television viewing on gender role attitudes. Communication Monographs, 89, 396-418. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2021.2018475.

- Hester, J. B., & Dougall, E. (2007). The efficiency of constructed week sampling for content analysis of online news. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 84(4), 811-824.

- Ilesanmi, O.O. (2018). Women’s visibility in decision making processes in Africa—progress, challenges, and way forward. Frontiers in Sociology, 3, p.38.

- Imhanrenialena, B., Ebhotemhen, W., Agbaeze, E., Eze, N., & Oforkansi, E. (2024). Exploring how institutionalized patriarchy relates to career outcomes among African women: evidence from Nigeria. Gender in Management: An International Journal. https://doi.org/10.1108/gm-06-2023-0223.

- Izunwanne, G. N., Akor, G. B., & Elesia, C. C. (2020). Gender and the Media: Assessing the Visibility of Women in the Nigerian Press from Five Widely Circulated National Dailies. International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science, 4(12), 370-377.

- Jan, M.U., Ullah, R., Hamza, M. & Muhammad, I. (2023). Muteness and oppression of women in The Wasted Vigil from the perspective of patriarchy and a muted group theory. University of Chitral Journal of Linguistics and Literature, 7(II), pp.292-300.

- Jungherr, A., Posegga, O. & An, J., (2019). Discursive power in contemporary media systems: A comparative framework. The International Journal of press/politics, 24(4), pp.404-425.https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161219841543.

- Kassova, L. (2020). The missing perspectives of women in news. Seattle, Washington: Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

- Kim, H., Jang, S. M., Kim, S. H., & Wan, A. (2018). Evaluating sampling methods for content analysis of Twitter data. Social media and society, 4(2), 2056305118772836.

- Knudson, T. (2008). News about China in the US Media Since the Cold War’s End: Analysis of Economic Structural Determinants. Waseda University Global COE Program, Global Institute for Asian Regional Integration.

- Koroma, S. B. (2023). Between the Local and the Global: Contexts, Transitions, and Implications. In Journalism Cultures in Sierra Leone: Between Global Norms and Local Pressures (pp. 191-207). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Kwanda, F. A., & Lin, T. T. (2020). Fake news practices in Indonesian newsrooms during and after the Palu earthquake: A hierarchy-of-influences approach. Information, Communication & Society, 23(6), 849-866.

- Lewis, D. (2019). Neo-liberalism, gender, and South African working women. South African board for people pracfices women’s report, 2019, pp.10-16.

- Madsen, D. (2018). Gender, Power and Institutional Change – The Role of Formal and Informal Institutions in Promoting Women’s Political Representation in Ghana. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 54, 70 - 87. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021909618787851.

- Mason, C. (2022, October 11). The gender say gap. Man Bites Dog. https://www.manbitesdog.com/campaigns/the-gender-say-gap/(accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Matole, E., Ngange, K., & Elonge, M. (2024). Investigating Roles and Assignments in Media Practice in Cameroon: A Gender-Based Approach. Advances in Journalism and Communication. https://doi.org/10.4236/ajc.2024.122017.

- Matos, R. (2024). Analyzing Black Men and Their Masculinities in Media. Instructing Intersectionality: Critical and Practical Strategies for the Journalism and Mass Communication Classroom, 167.

- McManus, J. (1995). A market-based model of news production. Communication Theory, 5(4), pp.301-338. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1468-2885.1995.TB00113.X.

- Mutabai, C., Yussuf, A.I., Timamy, F., Ngugi, P., Waraiciri, P. & Kwa, N. (2016). Patriarchal societies and women leadership: Comparative analysis of developed and developing nations. International Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities Research, 4(3), pp.356-366.

- Nartey, M. (2020). A feminist critical discourse analysis of Ghanaian feminist blogs. Feminist Media Studies, 21, 657 - 672. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2020.1837910.

- Nartey, M. (2023). Women’s voice, agency and resistance in Nigerian blogs: A feminist critical discourse analysis. Journal of Gender Studies, 33, 418 - 430. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2023.2246138.

- Nasruddin, F. A. (2021). Broadcast media and gender norms. ALIGN, United Kingdom. Retrieved from https://www.alignplatform.org/resources/broadcast-media-and-gender-norms.

- Ncube, L. (2021). Experiences of woman journalists in Zimbabwean man-dominated newsrooms. Communicare: Journal for Communication Sciences in Southern Africa, 40(2), 63-81.

- Neugart, M., & Zaharieva, A. (2025). Social networks, promotions, and the glass-ceiling effect. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 34(2), 370-402. https://doi.org/10.1111/jems.12603.

- Niemi, M. K. & Pitkänen, V. (2017). Gendered use of experts in the media: Analysis of the gender gap in Finnish news journalism. Public Understanding of Science, 26(3), 355–368. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662515621470.

- Nwano, T., & Akhirome-Omonfuegbe, L. (2024). Recognising patriarchy at the core of gender discrimination in Nigeria. International Journal of Law, Justice and Jurisprudence. https://doi.org/10.22271/2790-0673.2024.v4.i1b.100.

- Ojo, T. (2018). Media ownership and market structures: banes of news media sustainability in Nigeria?. Media, Culture & Society, 40(8), pp.1270-1280.

- Onalaja, A. E. & Otokiti, B. O. (2022). Women’s leadership in marketing and media: overcoming barriers and creating lasting industry impact. Journal of Advanced Education and Sciences, 2(1), 38-51.

- Onota, E. O., & Roberts, A. N. (2025). Gender Balance In Politics: Are Nigeria and Ghana On Divergent Or Aligned Paths?. African Journal of Gender, Society & Development, 14(2), 33.

- Ozer, A. (2023). Women Experts and Gender Bias in Political Media. Public Opinion Quarterly, 87, 293 - 315. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfad011.

- Pavarala, V.; Malik, K. K. & Cheeli, J. R. (2006). Community Media and Women: Transforming Silence into Speech’, Chapter 3.2. In A. Gurumurthy; P. J. Singh; A. Mundkur and M. Swamy (eds.). Gender in the Information Society: Emerging Issues. New Delhi: Asia-Pacific Development Information Programme, UNDP and Elsevier. pp. 96–109.

- Rodarte, A. K., & Richardson, R. (2024). Hierarchy of Influences. Preprint available at https://osf.io/zhw8q/download/?format=pdf.

- Roslyng, M.M. & Dindler, C. (2023). Media power and politics in framing and discourse theory. Communication Theory, 33(1), pp.11-20. https://doi.org/10.1093/ct/qtac012.

- Ross, K., & Padovani, C. (2019). Getting to the top. Journalism, Gender and Power. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315179520-2.

- Ryan, K. 2019. Women and Patriarchy in Early America, 1600–1800. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of American History. https://doi.org/10.1093/ACREFORE/9780199329175.013.584.

- Ryfe, D. (2021). The economics of news and the practice of news production. Journalism Studies, 22(1), pp.60-76. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670x.2020.1854619.

- Sampson, A. (2018, October 8). Opinion: Why we need to break the “Gender say gap.” Gorkana. https://www.gorkana.com/2018/10/opinion-abbie-sampson-womne-in-pr-why-we-need-to-break-the-gender-say-gap/ (accessed on 05 November 2024).

- Santoniccolo, F., Trombetta, T., Paradiso, M. N., & Rollè, L. (2023). Gender and media representations: A review of the literature on gender stereotypes, objectification and sexualization. International journal of environmental research and public health, 20(10), 5770. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph2010577.

- Sariol, A., & Abebe, M. (2017). The influence of CEO power on explorative and exploitative organizational innovation. Journal of Business Research, 73, 38-45. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JBUSRES.2016.11.016.

- Scheufele, D.A. & Tewksbury, D. (2007). Framing, agenda setting, and priming: The evolution of three media effects models. Journal of communication, 57(1), pp.9-20. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.0021-9916.2007.00326.X.

- Schoch, L. (2022). The gender of sports news: Horizontal segregation and marginalization of woman journalists in the Swiss press. Communication and Sport, 10(4), 746-766.

- Schudson, M. (2002). The news media as political institutions. Annual review of political science, 5(1), pp.249-269.

- Sharma, R. R., Chawla, S., & Karam, C. M. (2021) Global gender gap index: world economic forum perspective. Handbook on Diversity and Inclusion Indices: A Research Compendium, 150.

- Shen, Y. (2019). CEO characteristics: a review of influential publications and a research agenda. Accounting & Finance. https://doi.org/10.1111/acfi.12571.

- Sikweyiya, Y., Addo-Lartey, A., Alangea, D., Dako-Gyeke, P., Chirwa, E., Coker-Appiah, D., Adanu, R., & Jewkes, R. (2020). Patriarchy and gender-inequitable attitudes as drivers of intimate partner violence against women in the central region of Ghana. BMC Public Health, 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08825-z.

- Statista. (2024). Distribution of speaking characters on broadcast TV in the U.S. 1997-2023, by gender. https://www.statista.com/statistics/754839/speaking-characters-broadcast-tv-gender/ (accessed on 29 February 2025).

- Stempel, G. H. 1952. Sample Size for Classifying Subject Matter in Dailies. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 29(3), 333.

- Syawal, M. S., Dwiandini, A., Khaerunnisa, D. H., & Irwansyah, I. (2024). Exploring the role of muted group theory in understanding women’s experiences: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Humanity Studies (IJHS), 7(2), 279-294.

- Syawal, M.S., Dwiandini, A., Khaerunnisa, D.H. & Irwansyah, I. (2024). Exploring the role of muted group theory in understanding women’s experiences: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Humanity Studies (IJHS), 7(2), pp.279-294.

- Uchem, R. (2012). Women and internalised oppression. University of Nigeria.

- Umejei, E. (2018). Hybridizing journalism: Clash of two “journalisms” in Africa. Chinese Journal of Communication, 11(3), 344-358.

- UNESCO (2017). Enhancing a gender responsive film sector in the South Mediterranean region. https://www.unesco.org/en/safety-journalists (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- Van der Pas, D. J., & Aaldering, L. (2020). Gender differences in political media coverage: A meta-analysis. Journal of Communication, 70(1), 114-143. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqz046.

- Yeboah-Banin, A. A., Fofie, I. M., & Gadzekpo, A. (2020). Status of women in Ghanaian media: Providing evidence for gender equality and advocacy project. Alliance for Women in Media Africa (AWMA) and School of Information and Communication Studies, University of Ghana.

- Yeboah-Banin, A.A., Fofie, I.M. & Gadzekpo, A.S. (2024). Status of women in the Ghanaian media: Are women conscious of their own inequalities?. Journal of African Media Studies, 16(2), pp.197-215.

- Yih, C. (2022). Theological reflection on silencing and gender disenfranchisement. Practical Theology, 16(1), 31–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/1756073X.2022.2108822.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).