1. Introduction

Agricultural water use is becoming increasingly constrained across the Mediterranean basin, a region typified by semi-arid climates and significant hydrological stress [

1]. The chronic overexploitation of groundwater resources has led to the progressive degradation of aquifer systems, highlighting the urgent need for more efficient and sustainable water management practices [

2,

3]. Projections indicate that irrigation water demand in Mediterranean agriculture is expected to rise by 7–18% by the end of the 21st century due to climate change. In this context, implementing precise irrigation management strategies is essential to sustain agricultural productivity while safeguarding long-term water availability and ensuring food security [

4].

Thanks to advancements in modern irrigation systems, it is now possible to supply crops with the precise amount of water needed for optimal development, thereby minimizing losses and promoting sustainability [

5]. Accurate estimation of crop water requirements is crucial for effective water allocation, particularly in groundwater-dependent irrigation systems that face overexploitation. Research has emphasized the importance of incorporating crop water needs into allocation decisions, considering factors such as crop growth stages, water scarcity, and irrigation scheduling [

5,

6,

7,

8]. However, significant uncertainties persist regarding the use of water in the field.

The quantification of the actual volume of water applied in irrigation is complex due to multiple sources of uncertainty: partial coverage and variable calibration of flow meters, spatial and temporal heterogeneity of flow in pipes and emitters, unrecorded losses (from leaks or evaporation during distribution), and biases introduced by farmers’ self-reporting [

9,

10,

11]. Direct verification through field inspections requires substantial logistical and financial resources, especially when assessing large-scale agricultural areas that rely on groundwater extraction [

12].

Although some advisory systems integrate agroclimatic data with periodic irrigation recommendations, the quantification of actual irrigation water use remains largely insufficient. In several countries, water use estimates rely on a fragmented combination of volumetric extraction li-censes, flow meter readings, and self-reported data—approaches that often lack standardization, spatial resolution, and temporal continuity [

10]. In others, irrigation decisions are predominantly guided by empirical practices and manual monitoring tools, without the support of centralized platforms for tracking field-scale abstraction.

In response to this challenge, there is a growing need to incorporate tools capable of providing accurate, large-scale assessments of irrigation water use. Satellite remote sensing offers an effective solution, as it enables the estimation of water consumption through the analysis of vegetation spectral responses, providing continuous spatial and temporal information [

13,

14,

15,

16]. Numerous studies have investigated the integration of satellite imagery into the estimation of crop water requirements [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. Particular attention has been devoted to irrigated crops, with several studies applying the FAO-56 dual crop coefficient approach in combination with remote sensing to develop user-friendly tools for determining crop water demands [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30].

While zonal irrigation strategies have shown promising results—achieving additional water savings of 5–15% by minimizing over-irrigation in wetter subzones and securing sufficient supply in drier areas [

30]—accurate quantification of water use at the farm scale remains a persistent challenge. This is largely due to gaps in field instrumentation, spatial and temporal variability in flow rates, and reliance on self-reported data, which can introduce significant biases. These complexities underscore the need for robust, scalable methods to assess irrigation performance.

In this context, water use efficiency emerges as a multidimensional concept, interpreted differently depending on the disciplinary perspective and scale of analysis. From a crop physiology standpoint, WUE is defined as the maximization of carbon assimilation per unit of water transpired, placing emphasis on intrinsic plant traits such as stomatal conductance and photosynthetic capacity [

31,

32,

33]. In contrast, irrigation scientists evaluate efficiency based on the proportion of applied water that is beneficially used by the crop, employing metrics such as application or distribution efficiency [

34,

35]. Agronomic approaches typically assess WUE as the ratio of crop yield to irrigation water applied, integrating both biological response and management practices. Meanwhile, agricultural economists focus on maximizing net economic returns per unit of irrigation input, linking biophysical performance to socioeconomic outcomes [

36]. These varying perspectives reflect the complexity of agricultural water management and underscore the need for interdisciplinary frameworks [

37].

In recent years, a growing body of research has focused on spatially explicit assessments of irrigation efficiency, enabled by remote sensing technologies. These approaches integrate satellite-derived actual evapotranspiration (ETa) with modeled crop water requirements (CWR) to derive performance indicators at the field or landscape scale. For instance, [

38] applied a basin-wide remote sensing approach to estimate spatially distributed water productivity using MODIS-derived ETa and crop yield data, as part of a water accounting framework for the Indus Basin. The SEBAL model has been employed to estimate ETa and evaluate irrigation performance in large irrigated areas [

39,

40]. Likewise, [

41], 2020 utilized Landsat imagery in conjunction with the FAO-56 dual crop coefficient approach to assess irrigation efficiency in Mediterranean cropping systems. Additional studies have explored simplified proxies such as ETa/ETc or NDVI/ETa to estimate spatial variability in water use efficiency [

42]. Collectively, these approaches highlight the growing importance of remote sensing in developing scalable, data-driven tools for irrigation monitoring and management.

To quantify irrigation performance, this study develops the Spatial Irrigation Adequacy Index (SIAI), which expresses the relative difference between satellite-derived ETa and CWR, both estimated from Satellite imagery, thereby capturing the degree of alignment between theoretical demand and observed water use. A key innovation of this approach lies in its ability to estimate irrigation water use—particularly groundwater abstraction—exclusively from remote sensing data, without relying on field-based instrumentation or meter records. This makes the method especially valuable for regions with limited monitoring infrastructure. Its implementation across three Mediterranean aquifer systems, characterized by contrasting climatic, edaphic, and institutional conditions, highlights both the scalability and robustness of the SIAI. Moreover, the spatially continuous outputs produced by this method facilitate adaptive irrigation management, interregional policy benchmarking, and the development of harmonized datasets for hydrological modeling and sustainable groundwater governance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

This research was carried out in three groundwater dependent agricultural systems located in distinct regions of the Mediterranean: eastern Spain (Requena-Utiel Aquifer), northeastern Morocco (Ain Timguenay Aquifer), and southern Portugal (Campina do Faro) (

Figure 1). These sites encompass diverse agro-hydrogeological conditions and crop types, offering a comparative framework for evaluating irrigation efficiency under varying scenarios of water availability and climatic pressure.

In Spain, the Requena-Utiel Aquifer (RqU), located in the central sector of the Jucar River Basin District (Valencia province), spans approximately 987.9 km

2 and is predominantly composed of medium-permeability lithologies, with localized areas of higher hydraulic conductivity. The aquifer supports intensive agricultural activity, with grapevine (Vitis vinifera) as the dominant irrigated crop, covering an estimated 16,000 hectares. Sustained groundwater abstraction for irrigation purposes has led to a progressive decline in the aquifer’s quantitative status, prompting regulatory interventions by regional water authorities [

43]. In dry years, such as 2023, annual irrigation allocations are determined based on accumulated precipitation prior to the growing season, resulting in irrigation restrictions that confine water application to periods of peak evapotranspiration, typically from June to August.

To support water management, Spain’s Regional Offices for Water Management operate the Agroclimatic Information System for Irrigation (SIAR), an open-access platform (

https://siar.gob.es) that provides real-time agro-meteorological data, including air temperature, precipitation, reference evapotranspiration (ETo), and soil moisture. These data are processed by local research centers, which generate weekly crop-specific irrigation recommendations. The implementation of this system has been associated with 10–13% reductions in irrigation water use without yield losses, by improving the precision of irrigation timing and dosage [

44]. However, the quantification of actual irrigation volumes remains partially constrained by a reliance on a fragmented monitoring system, combining volumetric abstraction licenses, compulsory flow meters on high-capacity pumps, and periodic self-reporting through official digital platforms (eGROUNDWATER Consortium, 2024).

In Morocco, the Ain Timguenay Aquifer (AinT) is located within the mountainous region of Sefrou Province in the northeastern part of the country, encompassing an estimated area of 68.12 km2, although the delineation of its hydrogeological boundaries remains under refinement. The aquifer supports predominantly apple orchards (Malus domestica), which have historically been the principal irrigated crop in the area. However, the extent of apple cultivation has declined in recent years, primarily due to reduced winter chill accumulation affecting flowering and fruit set. As of 2022, the cultivated area has decreased to approximately 292 hectares due to climate change. Farmers prefer to substitute apple trees for plum trees because this species is adapted to current environmental conditions. The irrigation season extends from April to September, coinciding with the peak evaporative demand of the crop.

Unlike more institutionalized systems found in other countries, Morocco lacks a formal irrigation advisory service. Farmers typically rely on low-flow drip irrigation systems and schedule water applications based on manual soil moisture assessment tools and experiential agronomic knowledge. Occasional guidance from local agronomists complements these practices but does not ensure uniformity in irrigation strategies. Moreover, no centralized platform exists to systematically monitor water abstractions or integrate spatial information on crop water stress, limiting the potential for data-driven irrigation management at the regional scale [

45].

In Portugal, the Campina de Faro Aquifer System (CdF), located in the Algarve region, spans an area of approximately 86.4 km2. It is hydrologically bounded by low-permeability Cretaceous formations to the north and flanked by the Quelfes and Quarteira aquifer systems to the east and west, respectively. The region experiences an average annual precipitation of around 550 mm, yet groundwater abstraction significantly exceeds natural recharge rates. In the eastern sector predominantly for agricultural use, and in the western sector both agriculture and golf course irrigation are prevalent. The dominant irrigated crop is citrus (Citrus spp.), covering an area of approximately 10,185 hectares. Citrus cultivation requires year-round irrigation, with peak water demand occurring in April and October, reflecting both crop phenology and seasonal climatic conditions.

Despite the implementation of volumetric extraction licenses and mandatory flow meters on high-capacity pumps (exceeding 5 CV), the region lacks a structured, crop-specific irrigation advi-sory system. As a result, irrigation scheduling and water application practices largely depend on farmers’ empirical knowledge and sporadic technical support, without the benefit of real-time, telemetry-based decision-making platforms. This gap in systematic, spatially resolved water management limits the capacity for optimizing irrigation efficiency and exacerbates concerns regarding the long-term sustainability of the aquifer (eGROUNDWATER Consortium, 2024).

2.2. Spatial Adequacy Index Method Based on Vegetation Reflectance Data

Irrigation efficiency was quantified using the Spatial Irrigation Adequacy Index (SIAI), which com-pares the estimated Crop Water Requirements (CRW) with the actual evapotranspiration (ETa) derived from satellite remote sensing. The CWR was computed following the dual crop coefficient approach outlined in FAO-56 [

46], incorporating the Penman-Monteith equation to estimate reference evapotranspiration (ETo).This integrative approach combines high-resolution satellite imagery, ground-based meteorological observations, soil properties, and land use classifications, enabling spatially explicit assessments of irrigation performance across heterogeneous agricultural landscapes.

The methodological workflow integrates several interconnected components to estimate the SIAI by combining satellite-derived and agrometeorological data (

Figure 2). Using Landsat 8/9 and Sentinel-2 imagery (provided by USGS and ESA), vegetation indices such as NDVI and SAVI were computed based on NIR (ρNIR) and RED (ρRED) reflectance. These indices enabled the dynamic estimation of the basal crop coefficient (Kcb) via empirically calibrated relationships that reflect crop phenology and canopy development. In parallel, meteorological variables—including mini-mum relative humidity (RHmin), wind speed at 2 meters (U2), and reference evapotranspiration (ETo)—were integrated with crop-specific parameters such as plant height and tabulated Kcb values to calculate the maximum crop coefficient (Kc,max), allowing for local adjustment of crop water requirements (CWR). To account for the soil evaporation component, the approach incorporated soil hydraulic properties including Total Evaporable Water (TEW), Readily Evaporable Water (REW), and surface depletion (De), which were used to estimate the soil evaporation re-duction coefficient (Kr) and the soil evaporation coefficient (Ke), completing the calculation of ETc under standard (non-stressed) conditions. Concurrently, actual evapotranspiration (ETa) was derived from the Landsat-based SSEBop model [

47], which uses land surface temperature (LST), reference ET (ETr), and a thermal index to compute daily latent heat fluxes at field scale. For spatial analysis, agricultural field boundaries were delineated using official land use datasets, complemented by current estimates of irrigated areas in the Requena-Utiel aquifer [

48], while custom crop maps validated by ground surveys were used for the Ain Timguenay and Campina de Faro aquifers. Finally, irrigation efficiency was assessed using the Spatial Irrigation Adequacy Index (SIAI), defined as the relative difference between actual evapotranspiration (ETa) and crop evapotranspiration requirements (CWR). This spatially explicit indicator enabled the classification of irrigation performance across agricultural plots, allowing the identification of zones affected by over-irrigation or water deficits. As such, the SIAI provides a robust decision-support tool for improving operational water management and guiding targeted interventions.

2.3. Remote Sensing–Based Data Acquisition for Estimating Crop Water Requirements

Crop water requirements were estimated using the FAO-56 dual crop coefficient approach [

46] which disaggregates ETc into two main components: the basal crop coefficient (Kcb),the crop stress coefficient (Ks) and the soil evaporation coefficient (Ke), capturing evaporation from the soil surface. These coefficients are multiplied by the reference evapotranspiration (ETo), which quantities the atmospheric evaporative demand:

Reference evapotranspiration (ETo) was calculated using the FAO Penman-Monteith equation [

46], assuming a well-watered grass surface. Tabulated Kcb values were initially obtained from FAO-56 for sub-humid climates with moderate wind speeds (e.g., RHmin ≈ 45%, u

2 ≈ 2 m·s

−1), and subsequently adjusted where local agroclimatic conditions differed significantly [

49]. In this study, ETc was calculated assuming standard, non-limiting water availability, thus the water stress coefficient (Ks) was set to throughout the growing season.

To enhance spatial and temporal resolution in areas with limited meteorological coverage, dynamic Kcb values were estimated using satellite – derived vegetation indices (VI). Specifically, the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI)(Rouse et. al., 1974)and Soil-Adjusted Vegetation Index (SAVI) [

51] were computed from the red and near-infrared (NIR) spectral bands obtained from Sentinel-2 and Landsat 8 imagery. Empirical relationships between VI and Kcb were used to generate continuous time series of Kcb values at the plot scale. On dates with no available satellite imagery due to cloud cover or acquisition gaps, linear interpolation was applied between valid observations to reconstruct the daily Kcb profiles.

Table 1.

Empirical Kcb–VI relationships used for the different crops in this study.

Table 1.

Empirical Kcb–VI relationships used for the different crops in this study.

| Crop |

Empirical relation |

Reference |

Vinification grapes

(Vitis vitifera) |

|

[24] |

Apples orchards

(Malus domestica) |

|

[52] |

Citrus trees

(Citrus sinensis) |

|

[53] |

The soil evaporation coefficient (Ke) is determined as:

where K_(c,max) represents the maximum crop coefficient value following an irrigation or precipitation event, calculated based on wind speed (u2, m.s-1), minimum relative humidity (RHmin, %), and crop height (h,m), as flows:

where K_r is a dimensionless soil evaporation reduction coefficient which requires a daily water balance computation for the surface soil layer, which is formulated as

where TEW is the total evaporable water (mm), REW is readily evaporable water (mm), and De is the daily soil depletion. The parameters used for soil water balance computations for grapes, apples, and citrus are provided in

Table 2.

In Mediterranean climates with extended dry seasons, irrigation is essential to meet crop water requirements (CWR) due to insufficient rainfall relative to evapotranspiration demand. Despite its limitations, rainfall still contributes to crop water supply and must be considered in irrigation planning. CWR is thus calculated by subtracting effective precipitation (Pe) from crop evapotranspiration (ETc). Pe accounts for the portion of rainfall available in the root zone after losses from evaporation, runoff, or deep percolation. This integrated approach allows for a more accurate estimation of irrigation needs, improving water allocation and scheduling decisions in water-scarce agricultural systems [

54].

2.4. Remote Sensing-Based Data Acquisition for Estimating Evapotranspiration

Actual evapotranspiration (ETa) represents the total volume of water consumed by crops through the combined soil evaporation and plant transpiration. ETa is considered a robust and direct indicator of water use efficiency, especially under varying irrigation conditions [

46,

47].

In this study, actual evapotranspiration (ETa) was estimated using the Landsat Provisional Actual Evapotranspiration product, developed by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). This dataset is based on the Operational Simplified Surface Energy Balance (SSEBop) model [

55], which extends the principles of the original Simplified Surface Energy Balance (SSEB) approach [

56,

57] by integrating thermal indices and pixel-specific hot/dry and cold/wet anchor points, inherited from SEBAL [

13] and METRIC [

14]. This operational methodology enables consistent, large-scale estimation of actual evapotranspiration without reliance on in situ measurements.

Although no local eddy covariance towers or instruments such as lysimeters were available for direct calibration of ETa estimate, the use of the SSEBop model—integrated within the Landsat Provisional ETa product—relies on robust physical principles and has undergone extensive validation across diverse agroecological contexts. Previous studies have demonstrated the model’s strong agreement with flux tower measurements in both annual and perennial crops [

58,

59]. Therefore, while site-specific calibration could further reduce uncertainty, the selected approach offers a scientifically reliable and operationally scalable solution, particularly in data-scarce regions such as the Mediterranean aquifer systems evaluated in this study.

To enhance the temporal resolution of ETa estimates, imagery from both Landsat 8 and Landsat 9 was employed for the 2023 irrigation season. The synergistic orbital configuration of these two satellites allows for image acquisition approximately every eight days, which is essential for capturing intra-seasonal variability in crop water use within irrigated systems [

61]. This increased revisit frequency supports a more detailed temporal reconstruction of evapotranspiration dynamics, enabling robust water use assessments at the plot level.

To ensure data quality, only scenes with less than 20% cloud cover were retained after applying a rigorous quality filtering procedure. Due to the absence of daily observations, linear interpolation was applied between consecutive valid acquisitions to generate continuous daily ETa time series for the entire growing season. This approach facilitated the characterization of both spatial and temporal patterns of water use, thereby enhancing the accuracy of irrigation performance assessments at fine spatial resolution [

47,

62].

2.5. Spatial Adequacy Index Calculation

Irrigation efficiency in the three crops was quantified using the spatial adequacy index for irrigation (SIAI), calculated as follows:

This metric expresses the relative difference of actual evapotranspiration from the theoretical crop water requirement, serving as a field-scale indicator of irrigation performance over the irrigation season [

55]. Positive SIAI values indicate water deficit, while negative values suggest over-irrigation relative to crop demand, whereby water application exceeds agronomic demand (

Table 3). Such cases occur when ETa surpasses CWR, either because crops are transpiring more water than theoretically required or that excessive soil evaporation contributes significantly to total water loss.

Incorporating SIAI as an irrigation performance indicator thus enables the spatial identification of over-irrigated zones, supporting targeted improvements in water use efficiency across diverse agro-hydrological contexts. This classification enables the spatial delineation of plots exhibiting suboptimal irrigation efficiency, whether due to excess or deficit water user-offering a robust tool for optimizing irrigation strategies and promoting sustainable groundwater management in overexploited aquifer systems.

This classification enabled the spatial identification of agricultural plots exhibiting suboptimal irrigation efficiency, either due to over-irrigation or inadequate water supply. Such spatially explicit assessments serve as valuable decision-support tools for optimizing irrigation practices and tailoring water management strategies to site-specific agronomic and hydrological conditions. Locating areas with excessive or deficient water application, this approach facilitates targeted, evidence-based interventions aimed at enhancing water productivity, mitigating environmental degradation, and promoting the sustainable use of groundwater resources in vulnerable agricultural systems.

3. Results

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

3.1. Estimation of Crop Water Requirements from Remote Sensing Data

This study estimated the crop water requirements (CWR) during the 2023 irrigation season for three woody perennial crops—grapevine (Vitis vinifera), apple (Malus domestica), and citrus (Citrus spp.)—cultivated in contrasting groundwater-dependent agricultural systems across the Mediterranean basin. Accurate quantification of CWR is critical for designing efficient irrigation schedules and guiding sustainable water resource planning, particularly in water-scarce and climate-vulnerable regions.

For grapevines, the estimated CWR was 160.9 mm over the irrigation period. This relatively low value aligns with the species’ known, as Bobal (grape variety native to the Utiel-Requena region of Spain), drought-tolerant characteristics and physiological adaptations to semi-arid Mediterranean environments. Grapevines possess deep root systems and effective stomatal control, enabling them to maintain productivity under limited water conditions [

63]. Local agronomic guidelines indicate that seasonal crop water requirements (CWR) for grapevines typically range between 120 and 256 mm, depending on the cultivar and whether the production objective prioritizes yield quantity or fruit quality [

63].

Apple orchards exhibited a substantially higher estimated CWR of 215.52 mm. This reflects the greater sensitivity of apples to water stress, as well as their higher evapotranspiration rates during the growing season. Apple trees require consistent irrigation to sustain vegetative growth, fruit development, and to prevent physiological disorders related to water deficit. Stem water potential measurements, which are influenced by crop load and precipitation, are commonly used to assess irrigation needs [

64]. Studies conducted in comparable agroclimatic zones, such as, have reported seasonal CWR values ranging from 277 mm (wet year) to 465 mm (dry year) [

65]. These variations emphasize the importance of integrating seasonal climatic variability into irrigation planning frameworks.

Citrus crops demonstrated the highest CWR among the studied species, with an estimated value of 591.3 mm. This elevated requirement is consistent with the physiological attributes of citrus trees, including shallow root systems and high transpiration rates, especially during periods of elevated evaporative demand. To sustain yields and avoid detrimental water stress, citrus or-chards require efficient irrigation strategies such as regulated deficit irrigation and micro-irrigation systems [

49,

66].

The findings reveal a clear gradient in water demand across crops: citrus > apple > grapevine. This hierarchy has direct implications for irrigation scheduling and groundwater resource management in Mediterranean regions, where water scarcity and over-abstraction from aquifers pose major challenges. By enabling crop-specific water demand quantification, CWR estimation contributes to the formulation of targeted irrigation strategies and promotes the rational use of limited water resources.

High-resolution CWR estimates were generated by integrating remote sensing and meteorological data, enabling their visualization through interactive digital platforms (

Figure 3). These tools combine spatial layers—such as crop type, soil properties, and aquifer conditions—to deliver site-specific irrigation recommendations via mobile or web interfaces.

By identifying spatial and temporal variability in crop water demand, the approach offers decision-support for both farmers and water managers. Their integration with weather forecasts and groundwater data enables dynamic irrigation scheduling, contributing to long-term aquifer sustainability through informed monitoring and policy planning [

39,

46].

3.2. Assessment of Irrigation Performance Using the Spatial Adequacy Index

Irrigation performance was evaluated through a spatially explicit comparison between actual evapotranspiration (ETa), derived from satellite remote sensing, and crop water requirements (CWR), estimated using the FAO-56 dual crop coefficient approach. This methodological integration enabled the identification of spatial patterns of irrigation adequacy across the three perennial crop types analysed—grapevine, apple, and citrus—facilitating a detailed assessment of water use efficiency at the plot scale.

Figure 4 displays the distribution of the average Spatial Irrigation Adequacy Index (SIAI) at the plot scale for grapevines (Vitis vinifera), apple orchards (Malus domestica), and citrus groves (Citrus spp.). The green dashed line at SIAI = 0 represents the point of optimal irrigation, where actual water application (ETa) matches the estimated crop water demand. Deviations from this threshold reflect inefficiencies due to under- or over-irrigation.

In grapevine plots, the mean SIAI (X ̅=0.99, σ=23.5) is close to zero, suggesting that, on average, irrigation is well aligned with crop water requirements (−5% ≤ SIAI ≤ 10%). However, the relatively high standard deviation indicates heterogeneity in irrigation practices across parcels, with a significant number of plots experiencing either suboptimal deficits or excesses.

In apple orchards, a markedly negative mean SIAI (X ̅ = −13.24, σ = 40.3) indicates a generalized tendency toward over-irrigation. Over 60% of the plots fall below the −20% threshold, placing them within the extreme over-irrigation category. This situation raises concerns regarding inefficient water use, potential nutrient leaching, and negative impacts on groundwater sustainability. The high standard deviation also reflects variability in irrigation management, with a minority of plots approaching optimal application levels.

By contrast, citrus groves exhibited a positive mean SIAI (X ̅ = 23.14, σ = 24.5), indicating widespread under-irrigation relative to ETc. A significant proportion of parcels fall into the moderate (10% < SIAI ≤ 25%) and severe (SIAI > 25%) deficit categories. Despite this general trend, some plots were irrigated optimally or even excessively, underscoring the spatial variability of water management practices within this crop system.

These findings reveal distinct irrigation performance patterns among crops: grapevines demonstrate relatively efficient water use, apples are largely over-irrigated, and citrus groves face persistent deficits. The SIAI serves as a valuable diagnostic tool to detect inefficiencies at the field level and to guide the development of site-specific, crop-appropriate irrigation strategies, ultimately supporting sustainable groundwater management.

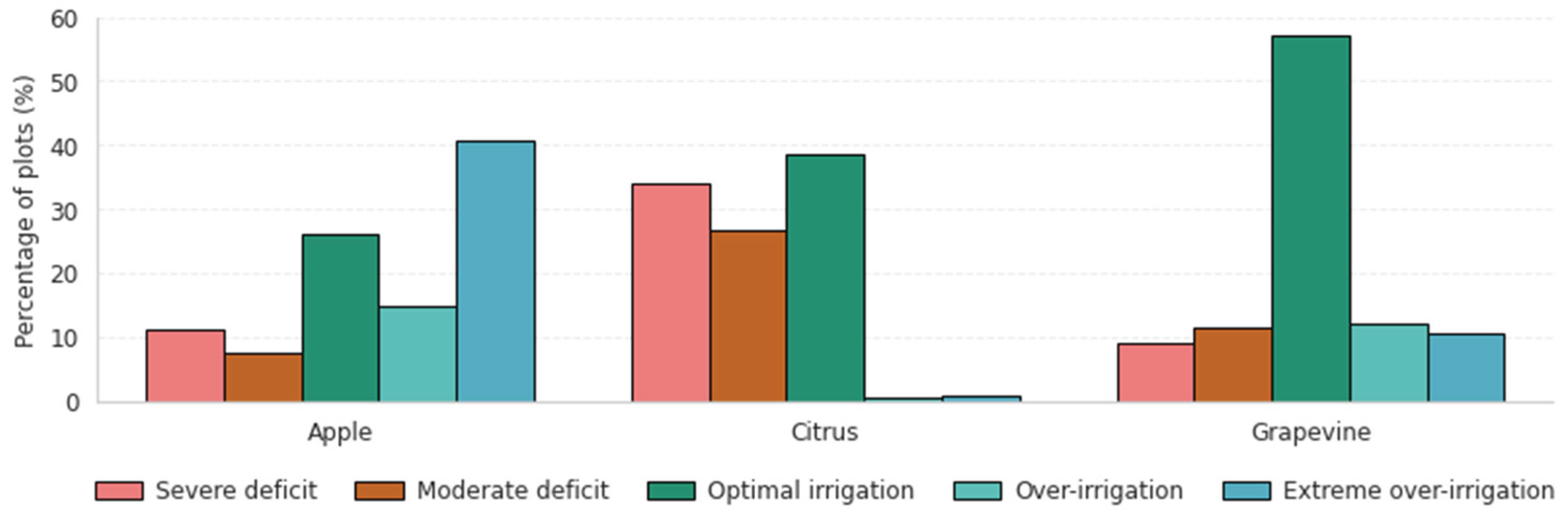

Figure 5 presents the proportional distribution of plots according to SIAI categories. The predominance of extreme over-irrigation in apple orchards confirms the quantitative analysis, while citrus plots show that nearly half of the fields experience severe water deficits. Grapevine plots display a more balanced distribution, though over half of the parcels still fall into the moderate over-irrigation category.

4. Discussion

Authors should discuss the results and how they can be interpreted from the perspective of previous studies and of the working hypotheses. The findings and their implications should be discussed in the broadest context possible. Future research directions may also be highlighted.

This study revealed significant crop-specific differences in spatial irrigation adequacy across three Mediterranean aquifers. Grapevines (Vitis vinifera) exhibited irrigation levels close to the optimal threshold, while apple orchards (Malus domestica) showed a consistent pattern of over-irrigation, and citrus groves (Citrus spp.) experienced persistent water deficits.

The near-optimal performance observed in vineyards is consistent with the literature supporting regulated or deficit irrigation strategies in grapevine cultivation [

67,

68], which suggests that moderate or deficit irrigation strategies can maintain productivity while enhancing water use efficiency in Mediterranean vineyards. In this case, spatial irrigation adequacy may also be influenced by the regulatory context: the Requena-Utiel aquifer is officially declared overexploited, and water allocations are regulated annually by the river basin authority based on crop-specific requirements [

45].

The over-irrigation observed in apple orchards likely reflects practices not sufficiently adjusted to evolving climatic conditions or crop load variability. Although they have a drip irrigation system and climatic data allowing them to practice rational irrigation, farmers irrigate without considering the water requirement of the apple tree. These findings align with previous studies highlighting the high sensitivity of apple trees to irrigation mismanagement in Mediterranean climates [

64]. Conversely, the under-irrigation trends identified in citrus plots may stem from physical water scarcity or restrictive abstraction policies. Although the average deficit was not extreme, it could still negatively impact yield and fruit quality, particularly during phenologically sensitive stages. This underscores the need for improved irrigation scheduling—both in volume and timing, especially in plots exhibiting severe deficits. The large standard deviation across citrus and apple plots further indicates heterogeneity in irrigation performance, warranting site-specific interventions. These findings highlight the utility of SIAI as a spatially explicit tool for identifying inefficiencies and informing targeted water management strategies.

Institutional contexts also differ across the case studies. While in Spain and Portugal, volumetric abstraction is regulated through licenses, flow meters, and digital self-reporting—progressively reinforced by remote monitoring and piezometric networks—Morocco lacks a formal irrigation advisory service, and groundwater governance remains informal, relying on collective agreements without systematic measurement of extracted volumes [

45].

One methodological limitation of this study lies in the linear interpolation used to estimate daily ETa from satellite imagery. This approach may smooth short-term variability caused by irrigation pulses or rainfall, potentially masking peak water use or stress periods. Moreover, accurate de-lineation of irrigated plots is critical, as misclassification can introduce substantial spatial bias. Cases where ETa exceeds CWR—typically interpreted as over-irrigation—may also be attributed to localized microclimatic variability, shallow groundwater contributions, inaccuracies in ETc estimation, or inherent limitations of the SSEBop model in capturing near-surface processes.

Overall, the spatially explicit evaluation of irrigation adequacy presented here offers valuable insights for optimizing irrigation scheduling, improving on-farm water use efficiency, and supporting groundwater conservation. Future efforts should integrate high-temporal-resolution ET products and socioeconomic data to enhance the operational relevance of such indices for adaptive irrigation management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.L.P., J.M.J, MA.J.B., and A.G.P.; resources, E.L.P., A.R.M., F.Z.B., A.K, P.T., methodology, E.L.P., J.M.J and MA.J.B.; validation, J.M.J., A.K. and LM.N.; investigation, E.L.P., writing—review and editing, E.L.P., J.M.J, MA.J.B., C.S.I., L.M.N and M.P.V.; project ad-ministration, M.P.V.; funding acquisition, M.P.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the eGROUNDWATER Project (GA No. 1921) under the PRIMA programme, supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the author by request (estloppe@upv.es).

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere gratitude to the San Antonio Irrigation Community (Spain) for providing the irrigation and management data used in this study, as well as to all stakeholders and field managers who contributed to data collection efforts in Portugal and Morocco. Their collaboration and technical assistance were essential to the successful completion of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Iglesias, A., & Garrote, L. (2015). Adaptation strategies for agricultural water management under climate change in Europe. Agricultural Water Management, 155, 113–124. [CrossRef]

- Custodio, E. (2002). Aquifer overexploitation: What does it mean? Hydrogeology Journal, 10(2), 254–277. [CrossRef]

- Foster, S. S. D., & Chilton, P. J. (2003). Groundwater: The processes and global significance of aquifer degradation. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 358(1440), 1957–1972. [CrossRef]

- FAO (2017). The Future of Food and Agriculture: Trends and Challenges, 4(4), 1951–1960. https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/2e90c833-8e84-46f2-a675-ea2d7afa4e24/content.

- Fereres, E.; Soriano, M.A. Deficit irrigation for reducing agricultural water use. Journal of Experimental Botany 2007, 58(2), 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowshon, M.K.; Iqbal, M.; Mojid, M.A.; Amin, M.S.M.; Lai, S.H. Optimization of equitable irrigation water delivery for a large-scale rice irrigation scheme. International Journal of Agricultural and Biological Engineering 2018, 11(5), 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, T.A. Enhancing water use efficiency in irrigated agriculture. Agronomy Journal 2001, 93(2), 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, C.; Rock, M.; Seckler, D. Water as an Economic Good: A Solution or a Problem? Research Report 14; International Irrigation Management Institute (IIMI): Colombo, Sri Lanka, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro, M.A.; Bahta, Y.T.; Jordaan, H. A systematic review on drivers of water-use behaviour among agricultural water users. Water 2024, 16(13), 1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, T.; Mieno, T.; Brozović, N. Satellite-based monitoring of irrigation water use: Assessing measurement errors and their implications for agricultural water management policy. Water Resources Research 2020, 56(11). [CrossRef]

- Ghoochani, O.M.; Eskandari Damaneh, H.; Ghanian, M.; Cotton, M. Why do farmers over-extract groundwater resources? Assessing (un)sustainable behaviors using an integrated agent-centered framework. Environments 2023, 10(12), 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ursitti, A.; Giannoccaro, G.; Prosperi, M.; De Meo, E.; de Gennaro, B.C. The magnitude and cost of groundwater metering and control in agriculture. Water 2018, 10(3), 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastiaanssen, W.G.M.; Menenti, M.; Feddes, R.A.; Holtslag, A.A.M. A remote sensing surface energy balance algorithm for land (SEBAL). Journal of Hydrology 1998, 212–213, 198–212. [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.G.; Tasumi, M.; Morse, A.; Trezza, R.; Wright, J.L.; Bastiaanssen, W.; Kramber, W.; Lorite, I.; Robison, C.W. Satellite-based energy balance for mapping evapotranspiration with internalized calibration (METRIC)—Applications. Journal of Irrigation and Drainage Engineering 2007, 133(4), 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, G.; Rasul, A.; Abdullah, H. Assessing how irrigation practices and soil moisture affect crop growth through monitoring Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 data. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 2023, 195(11), 1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Kong, J.; Wang, L.; Zhong, Y. Estimating evapotranspiration using an improved two-source energy balance model coupled with soil moisture in arid and semi-arid regions. Journal of Hydrology 2025, 659, 133283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huda, M.W.N.; Mawandha, H.G.; AG, M.R.; Ngadisih, N. The utilization of Sentinel-1 soil moisture satellite imagery for crop’s water requirement analysis in dryland agriculture. Proceedings of the International Conference on Sustainable Environment, Agriculture and Tourism (ICOSEAT 2022) 2023, 26, 484–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancela, J.J.; González, P.; Vilanova, M.; Mirás-Avalos, J.M. Water management using drones and satellites. Water 2019, 11(5), 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellvert, J.; Mata, M.; Vallverdú, X.; Paris, C.; Marsal, J. Optimizing precision irrigation of a vineyard to improve water use efficiency and profitability by using a decision-oriented vine water consumption model. Precision Agriculture 2020, 22, 319–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calera, A.; Garrido-Rubio, J.; Belmonte, M.; Arellano, I.; Fraile, L.; Campos, I.; Osann, A. Remote sensing-based water accounting to support governance for groundwater management for irrigation in the La Mancha Oriental aquifer, Spain. WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment 2017, 220, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Rubio, J.; Calera, A.; Arellano, I.; Belmonte, M.; Fraile, L.; Ortega, T.; Bravo, R.; González-Piqueras, J. Evaluation of remote sensing-based irrigation water accounting at river basin district management scale. Remote Sensing 2020, 12(19), 3187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pôças, I.; Calera, A.; Campos, I.; Cunha, M. Remote sensing for estimating and mapping single and basal crop coefficients: A review on spectral vegetation indices approaches. Agricultural Water Management 2020, 233, 106081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paço, T.A.; Pôças, I.; Cunha, M.; Silvestre, J.C.; Santos, F.L.; Paredes, P.; Pereira, L.S. Evapotranspiration and crop coefficients for a super-intensive olive orchard: Application of SIMDualKc and METRIC using ground and satellite observations. Journal of Hydrology 2014, 519, 2067–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, I.; Neale, C.M.U.; Calera, A.; Balbontín, C.; González-Piqueras, J. Assessing satellite-based basal crop coefficients for irrigated grapes (Vitis vinifera L.). Agricultural Water Management 2010, 98(1), 45–54. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.S.; Paredes, P.; Melton, F.; Johnson, L.; Wang, T.; López-Urrea, R.; Cancela, J.J.; Allen, R.G. Prediction of crop coefficients from fraction of ground cover and height: Background and validation using ground and remote sensing data. Agricultural Water Management 2020, 241, 106197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ippolito, M.; De Caro, D.; Ciraolo, G.; Minacapilli, M.; Provenzano, G. Estimating crop coefficients and actual evapotranspiration in citrus orchards with sporadic cover weeds based on ground and remote sensing data. Irrigation Science 2023, 41(1), 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Cuesta, J.M.; Allen, R.G.; Zarco-Tejada, P.J.; Kilic, A.; Santos, C.; Lorite, I.J. Impact of the spatial resolution on energy balance components in an open-canopy olive orchard. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2019, 74, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Er-Raki, S.; Chehbouni, A.; Boulet, G.; Williams, D.G. Using the dual approach of FAO-56 for partitioning ET into soil and plant components for olive orchards in a semi-arid region. Agricultural Water Management 2010, 97(11), 1769–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellvert, J.; Adeline, K.; Baram, S.; Pierce, L.; Sanden, B.L.; Smart, D.R. Monitoring crop evapotranspiration and crop coefficients over an almond and pistachio orchard through remote sensing. Remote Sensing 2018, 10(12), 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perelli, C.; Branca, G.; Corbari, C.; Mancini, M. Physical and economic water productivity in agriculture between traditional and water-saving irrigation systems: A case study in Southern Italy. Sustainability 2024, 16(12), 4971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condon, A.G.; Richards, R.A.; Rebetzke, G.J.; Farquhar, G.D. Improving intrinsic water-use efficiency and crop yield. Crop Science 2002, 42(1), 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinclair, T.R.; Tanner, C.B.; Bennett, J.M. Water-use efficiency in crop production. BioScience 1984, 34(1), 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, J.S. Increasing agricultural water use efficiency to meet future food production. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2000, 82(1–3), 105–119. [CrossRef]

- Bos, M.G.; Nugteren, J. On Irrigation Efficiencies, 4th ed.; International Institute for Land Reclamation and Improvement (ILRI): Wageningen, The Netherlands, 1990; Publication 120. [Google Scholar]

- Howell, T. Irrigation efficiency. In Encyclopedia of Soil Science, 2nd ed.; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2003; Chapter 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, D.; Lamm, F.; Alam, M.; Trooien, T.; Barnes, P.; Mankin, K. Efficiencies and water losses of irrigation systems. Irrigation Management Series 1997, February, 1–6.

- Nair, S.; Johnson, J.; Wang, C. Efficiency of irrigation water use: A review from the perspectives of multiple disciplines. Agronomy Journal 2013, 105(2), 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, P.; Bastiaanssen, W.; Molden, D.; Cheema, M.J.M. Basin-wide water accounting based on remote sensing data: An application for the Indus Basin. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences 2013, 17(7), 2473–2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastiaanssen, W.; Molden, D.J.; Makin, I.W. Remote sensing for irrigated agriculture: Examples from research and possible applications. Agricultural Water Management 2000, 46(2), 137–155. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0378377400000809.

- Jimenez-Bello, M.A.; Castel, J.R.; Testi, L.; Intrigliolo, D.S. Assessment of a remote sensing energy balance methodology (SEBAL) using different interpolation methods to determine evapotranspiration in a citrus orchard. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 2015, 8(4), 1465–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Rubio, J.; González-Piqueras, J.; Campos, I.; Osann, A.; González-Gómez, L.; Calera, A. Remote sensing–based soil water balance for irrigation water accounting at plot and water user association scale. Agricultural Water Management 2020, 238, 106236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker-Reshef, I.; Justice, C.; Sullivan, M.; et al. Monitoring global croplands with coarse-resolution Earth observations: The Global Agriculture Monitoring (GLAM) project. Remote Sensing 2010, 2(6), 1589–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchis-Ibor, C.; López-Pérez, E.; García-Mollá, M.; et al. Advancing co-governance through framing processes: Insights from action-research in the Requena-Utiel aquifer (Eastern Spain). International Journal of the Commons 2023, 17(1), 347–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirás-Avalos, J.M.; Rubio-Asensio, J.S.; Ramírez-Cuesta, J.M.; Maestre-Valero, J.F.; Intrigliolo, D.S. Irrigation-Advisor—A decision support system for irrigation of vegetable crops. Water 2019, 11(11), 2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchis-Ibor, C.; Bouzidi, Z.; Varanda, M.P.; et al. Can enhanced information systems and citizen science improve groundwater governance? Lessons from Morocco, Portugal and Spain. Water 2024, 16(19), 2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, Richard & Pereira, L. & Smith, Martin. Crop evapotranspiration-Guidelines for computing crop water requirements, 1998. FAO Irrigation and drainage paper 56.

- Senay, G.; Bohms, S.; Singh, R.K.; Gowda, P.H.; Velpuri, N.M.; Alemu, H.; Verdin, J.P. Operational evapotranspiration mapping using remote sensing and weather datasets: A new parameterization for the SSEB approach. Journal of the American Water Resources Association 2013, 49(3), 577–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Pérez, E.; Sanchis-Ibor, C.; Jiménez-Bello, M.Á.; Pulido-Velazquez, M. Mapping of irrigated vineyard areas through machine learning and remote sensing. Agricultural Water Management 2024, 302, 108988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.G.; Pereira, L.S.; Raes, D.; Smith, M. Crop Evapotranspiration—Guidelines for Computing Crop Water Requirements (FAO Irrigation and Drainage Paper 56); FAO: Rome, Italy, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Rouse, J.W.; Haas, R.W.; Schell, J.A.; Deering, D.W.; Harlan, J.C. Monitoring the vernal advancement and retrogradation of natural vegetation. NASA/GSFC: Greenbelt, MD, USA, 1974, pp. 1–8.

- Qi, J.; Chehbouni, A.; Huete, A.R.; Kerr, Y.H.; Sorooshian, S. A modified soil-adjusted vegetation index. Remote Sensing of Environment 1994, 48(2), 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odi-Lara, M.; Campos, I.; Neale, C.M.U.; Ortega-Farías, S.; Poblete-Echeverría, C.; Balbontín, C.; Calera, A. Estimating evapotranspiration of an apple orchard using a remote sensing-based soil water balance. Remote Sensing 2016, 8(3), 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawant, S.A.; Chakraborty, M.; Suradhaniwar, S.; Adinarayana, J.; Durbha, S.S. Time-series analysis of remote sensing observations for citrus crop growth stage and evapotranspiration estimation. ISPRS Archives 2016, XLI-B8, 1037–1042. [CrossRef]

- Brouwer, C.; Heibloem, M. Irrigation Water Needs: Irrigation Water Management. Training Manual No. 3; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Senay, G. Satellite psychrometric formulation of the operational simplified surface energy balance (SSEBop) model. Applied Engineering in Agriculture 2018, 34(3), 555–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senay, G.; Budde, M.E.; Verdin, J.P. Enhancing the Simplified Surface Energy Balance (SSEB) approach for estimating landscape ET: Validation with the METRIC model. Agricultural Water Management 2011, 98(4), 606–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senay, G.; Budde, M.; Verdin, J.P.; Melesse, A.M. A coupled remote sensing and simplified surface energy balance approach to estimate actual evapotranspiration from irrigated fields. Sensors 2007, 7(6), 979–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senay, G.; Friedrichs, M.; Morton, C.; et al. Mapping actual evapotranspiration using Landsat for the conterminous United States: Google Earth Engine implementation and assessment of the SSEBop model. Remote Sensing of Environment 2022, 275, 113011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knipper, K.; Anderson, M.; Bambach, N.; et al. A comparative analysis of OpenET for evaluating evapotranspiration in California almond orchards. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 2024, 355, 110146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hazdour, I.; Le Page, M.; Hanich, L.; Chakir, A.; Lopez, O.; Jarlan, L. A GEE-TSEB workflow for daily high-resolution fully remote-sensing evapotranspiration: Validation over four crops in semi-arid conditions and comparison with the SSEBop experimental product. Environmental Modelling & Software 2025, 187, 106365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pocock, M.J.O.; Chapman, D.S.; Sheppard, L.J.; Roy, H.E. Choosing and Using Citizen Science; Centre for Ecology & Hydrology: Wallingford, UK, 2014; 28 pp, https://www.ceh.ac.uk/sites/default/files/sepa_choosingandusingcitizenscience_interactive_4web_final_amended-blue1.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, M.C.; Allen, R.G.; Morse, A.; Kustas, W.P. Use of Landsat thermal imagery in monitoring evapotranspiration and managing water resources. Remote Sensing of Environment 2012, 122, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buesa, I.; Sanz, F.; Pérez, D.; Yeves, A.; Martínez, A.; Chirivella, C.; Bonet, L.; Intrigliolo, D.S. Manejo del agua y la vegetación en el viñedo mediterráneo; Fundación Cajamar: Almería, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Girona, J.; del Campo, J.; Mata, M.; Lopez, G.; Marsal, J. A comparative study of apple and pear tree water consumption measured with two weighing lysimeters. Irrigation Science 2011, 29(1), 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ucar, Y.; Kocięcka, J.; Liberacki, D.; Rolbiecki, R. Analysis of crop water requirements for apple using dependable rainfall. Atmosphere 2023, 14(1), 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Evapotranspiración del cultivo en condiciones estándar. Introducción a la evapotranspiración del cultivo (ETc); 2018. Disponible en: http://www.fao.org/3/x0490s/x0490s00.htm.

- Chaves, M.M.; Santos, T.P.; Souza, C.R.; et al. Deficit irrigation in grapevine improves water-use efficiency while controlling vigour and production quality. Annals of Applied Biology 2007, 150(2), 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intrigliolo, D.; Castel, J. Response of grapevine cv. Tempranillo to timing and amount of irrigation: Water relations, vine growth, yield and berry and wine composition. Irrigation Science 2010, 28(2), 113–125. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).