Submitted:

22 October 2025

Posted:

24 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

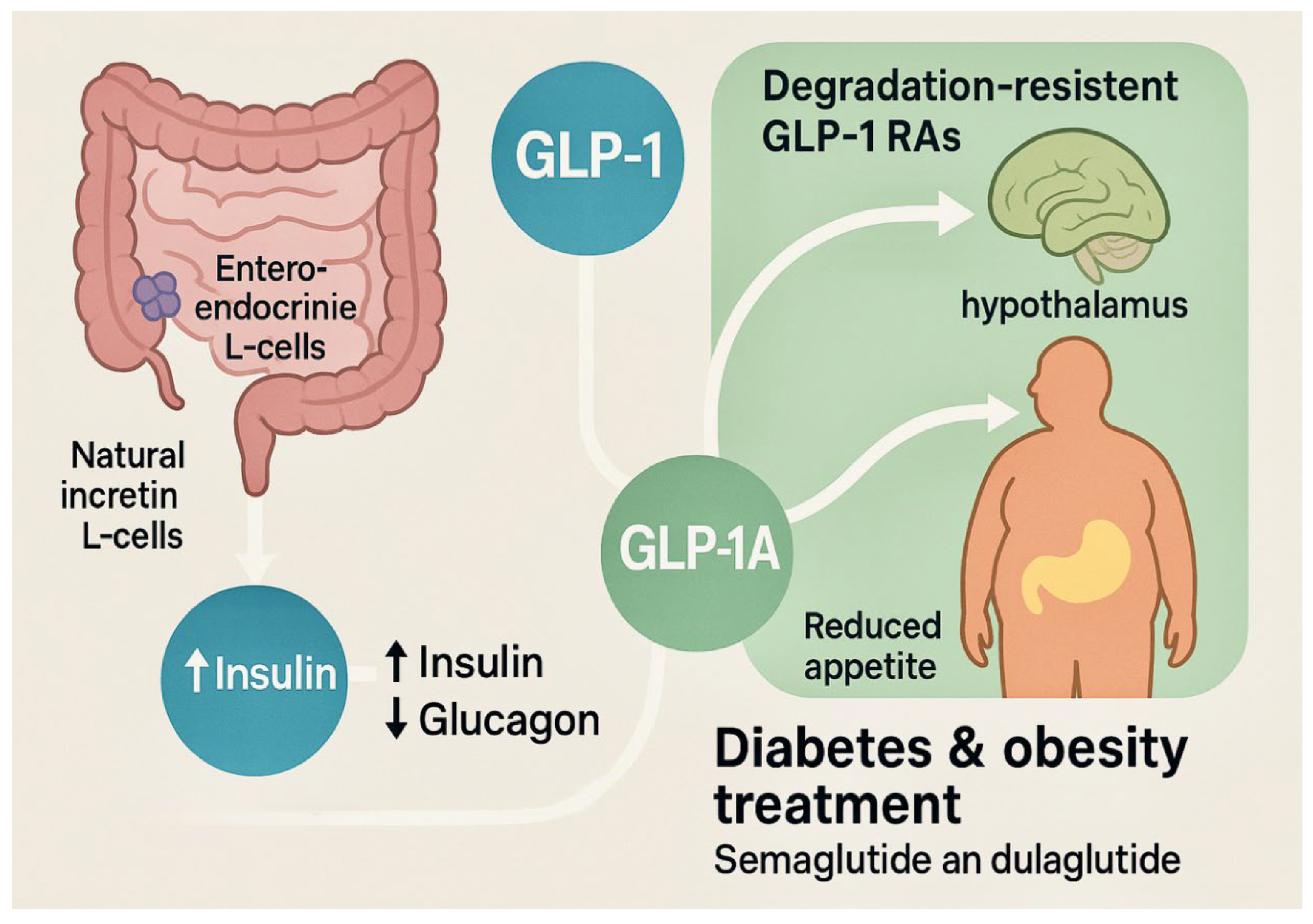

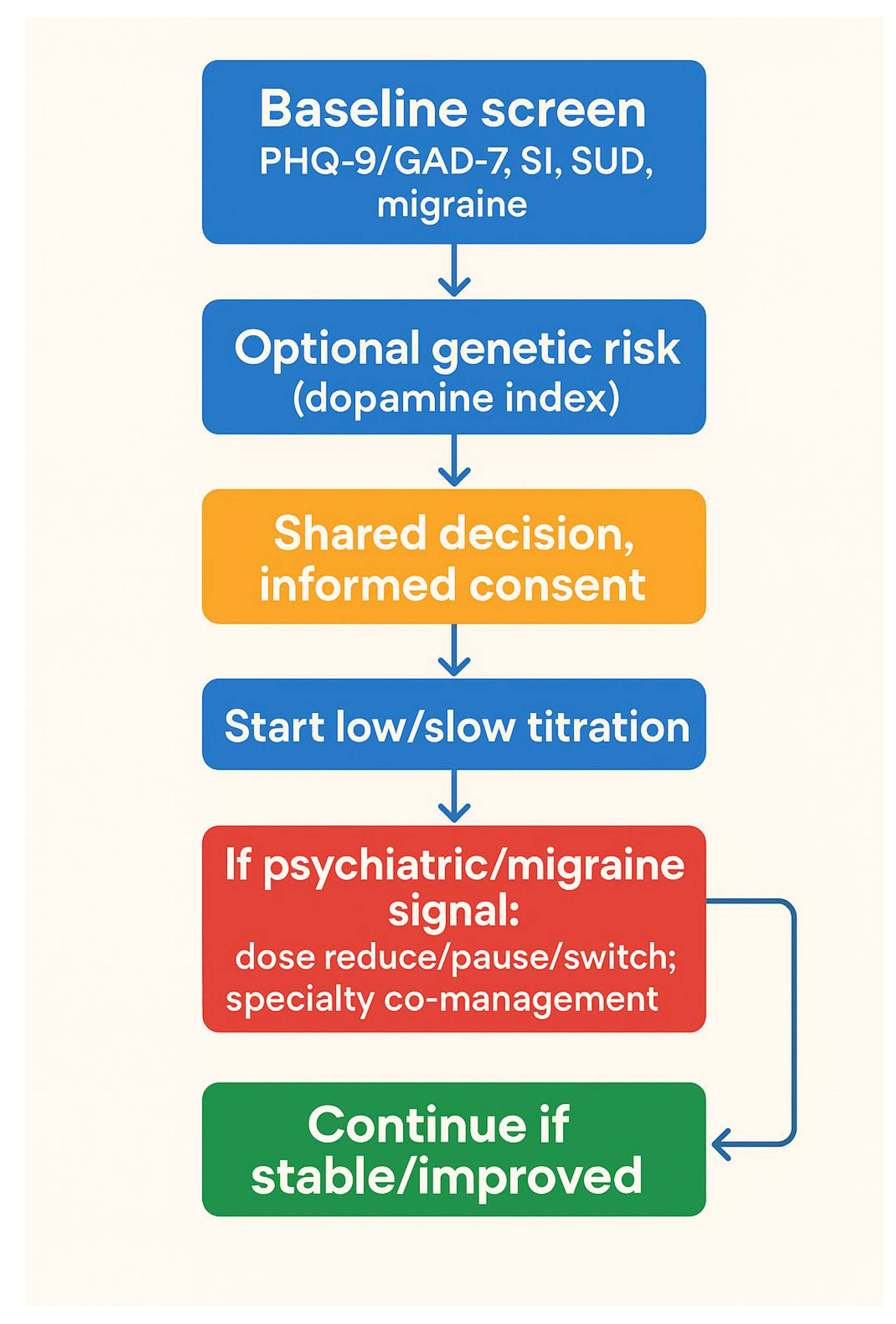

Background: GLP‑1 receptor agonists (GLP‑1RAs) are effective for type 2 diabetes and obesity and engage central stress and reward pathways (HPA axis; mesolimbic dopamine). Psychiatric signals have been reported in some settings. Objective :To narratively synthesize evidence on neuropsychiatric effects of GLP‑1RAs—mood, anxiety, suicidality, reward processing, substance use, and migraine—and to consider genetic/epigenetic moderators (e.g., hypodopaminergia/reward deficiency syndrome).Evidence: Mechanistic and imaging studies demonstrate GLP‑1 engagement of HPA and reward circuitry; animal work suggests acute anxiogenic responses with mixed chronic effects. Pharmacovigilance datasets (FAERS/EudraVigilance) show signals for headache, dizziness, sensory changes, and less consistently for depression/anxiety/suicidality; such data are hypothesis‑generating and not causal. Clinical trials and meta‑analyses report heterogeneous outcomes, including small antidepressant effects in some T2DM cohorts. Conclusions: Neuropsychiatric outcomes with GLP‑1RAs appear context‑dependent. Individuals with hypodopaminergic biology may be vulnerable to reward blunting/anxiety, whereas others may experience mood benefits. A pragmatic approach is screen–stratify–monitor, with slow titration and prompt adjustment if psychiatric signals emerge. Prospective, genotype‑informed studies are needed to identify who benefits or is harmed and why.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. History of the GLP-1 Receptor

2.2. GLP-1 in Depression, Suicidiality, and Anxiety

2.3. GLP-1 in Substance Use Disorder

2.4. GLP-1 in Neuropsychiatric Disorders

3. Counterarguments

3.1. Policy and Clinical Implementation Framework

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adhikari R, Jha K, Dardari Z, Heyward J, Blumenthal R. S, Eckel R.H, Alexander C.G, Blaha M.J (). National Trends in Use of Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter-2 Inhibitors and Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists by Cardiologists and Other Specialties, 2015 to 2020. Journal of the American Heart Association 2022, 11, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W. , Cai, P., Zou, W., & Fu, Z. Psychiatric adverse events associated with GLP-1 receptor agonists: a real-world pharmacovigilance study based on the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System database. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2024, 15, 1330936. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Feng, Yu, Kai, Yang, Zhirong, Wu, Shanshan, Zhang, Yuan, Shi, Luwen, Ji, Linong, Zhan, Siyan, Impact of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists on Major Gastrointestinal Disorders for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Mixed Treatment Comparison Meta-Analysis, Journal of Diabetes Research, 2012, 230624, 14 pages, 2012.

- Drucker, D. J. , & Nauck, M. A. The incretin system: glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors in type 2 diabetes. The Lancet 2006, 368, 1696–1705. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, Y. M. , Fujita, Y., & Kieffer, T. J. Glucagon-like peptide-1: glucose homeostasis and beyond. Annual review of physiology 2014, 76, 535–559. [Google Scholar]

- Crane, J. , & McGowan, B. The GLP-1 agonist, liraglutide, as a pharmacotherapy for obesity. Therapeutic advances in chronic disease 2016, 7, 92–107. [Google Scholar]

- van Bloemendaal, L. , IJzerman, R. G., Ten Kulve, J. S., Barkhof, F., Konrad, R. J., Drent, M. L.,... & Diamant, M. GLP-1 receptor activation modulates appetite-and reward-related brain areas in humans. Diabetes 2014, 63, 4186–4196. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Deacon, C. F. , Johnsen, A. H., & Holst, J. J. Degradation of glucagon-like peptide-1 by human plasma in vitro yields an N-terminally truncated peptide that is a major endogenous metabolite in vivo. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 1995, 80, 952–957. [Google Scholar]

- Baggio, L. L. , & Drucker, D. J. Biology of incretins: GLP-1 and GIP. Gastroenterology 2007, 132, 2131–2157. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, J. Y. , Wang, Q. W., Yang, X. Y., Yang, W., Li, D. R., Jin, J. Y.,... & Zhang, X. F. GLP− 1 receptor agonists for the treatment of obesity: role as a promising approach. Frontiers in endocrinology 2023, 14, 1085799. [Google Scholar]

- Manuel Gil-Lozano, Diego Pérez-Tilve, Mayte Alvarez-Crespo, Aurelio Martís, Ana M. Fernandez, Pablo A. F. Catalina, Lucas C. Gonzalez-Matias, Federico Mallo, GLP-1(7-36)-amide and Exendin-4 Stimulate the HPA Axis in Rodents and Humans. Endocrinology 2010, 151, 2629–2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mello, A. F. , Mello, M. F., Carpenter, L. L., & Price, L. H. Update on stress and depression: the role of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. Revista brasileira de psiquiatria (Sao Paulo, Brazil : 1999) 2003, 25, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauchi, M. , Zhang, R., D'Alessio, D. A., Seeley, R. J., & Herman, J. P. Role of central glucagon-like peptide-1 in hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical facilitation following chronic stress. Experimental neurology 2008, 210, 458–466. [Google Scholar]

- Modestino, E. J. , Bowirrat, A., Lewandrowski, K. U., Sharafshah, A., Badgaiyan, R. D., Thanos, P. K., Baron, D., Dennen, C. A., Elman, I., Sunder, K., Murphy, K. T., & Blum, K. Hemiplegic Migraines Exacerbated using an Injectable GLP-1 Agonist for Weight Loss. Acta scientific neurology 2024, 7, 12–18. [Google Scholar]

- Drucker, D. J. The biology of incretin hormones. Cell metabolism 2006, 3, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudaliar, S. , & Henry, R. R. The incretin hormones: from scientific discovery to practical therapeutics. Diabetologia 2012, 55, 1865–1868. [Google Scholar]

- Perley, M. J. , & Kipnis, D. M. Plasma insulin responses to oral and intravenous glucose: studies in normal and diabetic sujbjects. The Journal of clinical investigation 1967, 46, 1954–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupre, J. (1964). An intestinal hormone affecting glucose disposal in man.

- Holst, J. J. Glucagon and other proglucagon-derived peptides in the pathogenesis of obesity. Frontiers in Nutrition 2022, 9, 964406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanvantari, S. , Seidah, N. G., & Brubaker, P. L. Role of prohormone convertases in the tissue-specific processing of proglucagon. Molecular endocrinology 1996, 10, 342–355. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Holt, M. K. , Richards, J. E., Cook, D. R., Brierley, D. I., Williams, D. L., Reimann, F., Gribble, F. M., & Trapp, S. Preproglucagon Neurons in the Nucleus of the Solitary Tract Are the Main Source of Brain GLP-1, Mediate Stress-Induced Hypophagia, and Limit Unusually Large Intakes of Food. Diabetes 2019, 68, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whalley, N. M. , Pritchard, L. E., Smith, D. M., & White, A. Processing of proglucagon to GLP-1 in pancreatic α-cells: is this a paracrine mechanism enabling GLP-1 to act on β-cells? The Journal of endocrinology 2011, 211, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unger, R. H. , Eisentraut, A. M., McCall, M. S., & Madison, L. L. Measurements of endogenous glucagon in plasma and the influence of blood glucose concentration upon its secretion. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 1970, 49, 837–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, G. I. , Sanchez-Pescador, R., Laybourn, P. J., & Najarian, R. C. Exon duplication and divergence in the human preproglucagon gene. Nature 1983, 304, 368–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holst, J. J. Evidence that enteroglucagon (II) is identical with the C-terminal sequence (residues 33–69) of glicentin. Biochemical Journal 1982, 207, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holst, J. J. The physiology of glucagon-like peptide 1. Physiological Reviews 2007, 87, 1409–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ørskov, C. , Wettergren, A., & Holst, J. J. Biological effects and metabolic rates of glucagonlike peptide-1 7–36 amide and glucagonlike peptide-1 7–37 in healthy subjects are indistinguishable. Diabetes 1993, 42, 658–661. [Google Scholar]

- Kreymann, B. , Ghatei, M. A., Williams, G., & Bloom, S. R. Glucagon-like peptide-1 7-36: a physiological incretin in man. The Lancet 1987, 330, 1300–1304. [Google Scholar]

- Lotosky, J. , Jean, X., Altankhuyag, A., Khan, S., Bernotas, A., Sharafshah, A., Blum, K., Posner, A., & Thanos, P. K. GLP-1 and Its Role in Glycogen Production: A Narrative Review. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazakos, K. Incretin Effect: Glp-1, Gip, Dpp4. Diabetes research and clinical practice 2011, 93, S32–S36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creutzfeldt, W. The [pre-] history of the incretin concept. Regulatory peptides 2005, 128, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edholm, T. , Degerblad, M., Grybäck, P., Hilsted, L., Holst, J. J., Jacobsson, H.,... & Hellström, P. M. Differential incretin effects of GIP and GLP-1 on gastric emptying, appetite, and insulin-glucose homeostasis. Neurogastroenterology & Motility 2010, 22, 1191–e315. [Google Scholar]

- Mentlein, R. Mechanisms underlying the rapid degradation and elimination of the incretin hormones GLP-1 and GIP. Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2009, 23, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deacon, C. F. Circulation and degradation of GIP and GLP-1. Hormone and metabolic research 2004, 36, 761–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toft-Nielsen, M. B. , Madsbad, S., & Holst, J. J. Continuous subcutaneous infusion of glucagon-like peptide 1 lowers plasma glucose and reduces appetite in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes care 1999, 22, 1137–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mentlein R, Gallwitz B, Schmidt WE. Dipeptidyl-peptidase IV hydrolyses gastric inhibitory polypeptide, glucagon-like peptide-1(7–36)amide, peptide histidine methionine and is responsible for their degradation in human serum. Eur J Biochem. 1993, 214, 829–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulvihill, E. E. , & Drucker, D. J. Pharmacology, physiology, and mechanisms of action of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors. Endocrine reviews 2014, 35, 992–1019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yap, M. K. K. , & Misuan, N. Exendin-4 from Heloderma suspectum venom: From discovery to its latest application as type II diabetes combatant. Basic & clinical pharmacology & toxicology 2019, 124, 513–527. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, L. L. , Young, A. A., & Parkes, D. G. Pharmacology of exenatide (synthetic exendin-4): a potential therapeutic for improved glycemic control of type 2 diabetes. Regulatory peptides 2004, 117, 77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Kolterman, O. G. , Kim, D. D., Shen, L., Ruggles, J. A., Nielsen, L. L., Fineman, M. S., & Baron, A. D. Pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and safety of exenatide in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy 2005, 62, 173–181. [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen, L. B. , & Lau, J. The discovery and development of liraglutide and semaglutide. Frontiers in endocrinology 2019, 10, 155. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, R. , Galave, V. S. B., & Jindal, A. B. Current status of Liraglutide delivery systems for the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Drug Delivery and Translational Research 2025, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J. Y. , Wang, Q. W., Yang, X. Y., Yang, W., Li, D. R., Jin, J. Y.,... & Zhang, X. F. GLP− 1 receptor agonists for the treatment of obesity: role as a promising approach. Frontiers in endocrinology 2023, 14, 1085799. [Google Scholar]

- Detka, J. , & Głombik, K. Insights into a possible role of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists in the treatment of depression. Pharmacological Reports 2021, 73, 1020–1032. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosal, S. , Myers, B., & Herman, J. P. Role of central glucagon-like peptide-1 in stress regulation. Physiology & behavior 2013, 122, 201–207. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, W. , Wang, S., Tang, H., Yuan, T., Zuo, W., & Liu, Y. Neuropsychiatric adverse events associated with Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists: a pharmacovigilance analysis of the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System database. European Psychiatry 2025, 68, e20. [Google Scholar]

- Lewandrowski, K. U. , Blum, K., Sharafshah, A., Thanos, K. Z., Thanos, P. K., Zirath, R., Pinhasov, A., Bowirrat, A., Jafari, N., Zeine, F., Makale, M., Hanna, C., Baron, D., Elman, I., Modestino, E. J., Badgaiyan, R. D., Sunder, K., Murphy, K. T., Gupta, A., Lewandrowski, A. P. L., … Schmidt, S. Genetic and Regulatory Mechanisms of Comorbidity of Anxiety, Depression and ADHD: A GWAS Meta-Meta-Analysis Through the Lens of a System Biological and Pharmacogenomic Perspective in 18.5 M Subjects. Journal of personalized medicine 2025, 15, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Bloemendaal, L. , IJzerman, R. G., Ten Kulve, J. S., Barkhof, F., Konrad, R. J., Drent, M. L.,... & Diamant, M. GLP-1 receptor activation modulates appetite-and reward-related brain areas in humans. Diabetes 2014, 63, 4186–4196. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Blum, K. , Sharafshah, A., Lewandrowski, K. U., Schmidt, S. L., Fiorelli, R. K. A., Pinhasov, A.,... & Badgaiyan, R. D. Pre-addiction phenotype is associated with dopaminergic dysfunction: Evidence from 88.8 million genome-wide association study-based samples. Gene & Protein in Disease 2025, 8090. [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan S, Bodahanapati A, Katta A, Aydemir E, Mendoza A, Vigilia C, Blum K, Baron D, Lewandrowski KU, Badgaiyan RD, Sunder K. Personalized Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (PrTMS®) Coupled with Transcranial Photobiomodulation (tPBM) For Co-Occurring Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Acta Sci Neurol. 2025, 8, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tobaiqy M, Elkout H. Psychiatric adverse events associated with semaglutide, liraglutide and tirzepatide: a pharmacovigilance analysis of individual case safety reports submitted to the EudraVigilance database. Int J Clin Pharm aprile. 2024, 46, 488–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharafshah, A. , Lewandrowski, K. U., Gold, M. S., Fuehrlein, B., Ashford, J. W., Thanos, P. K., Wang, G. J., Hanna, C., Cadet, J. L., Gardner, E. L., Khalsa, J. H., Braverman, E. R., Baron, D., Elman, I., Dennen, C. A., Bowirrat, A., Pinhasov, A., Modestino, E. J., Carney, P. R., Cortese, R., … Blum, K. In Silico Pharmacogenomic Assessment of Glucagon-like Peptide-1 (GLP1) Agonists and the Genetic Addiction Risk Score (GARS) Related Pathways: Implications for Suicidal Ideation and Substance Use Disorder. Current neuropharmacology 2025, 23, 974–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, M. L. , Kassir, S. A., Underwood, M. D., Bakalian, M. J., Mann, J. J., & Arango, V. Dysregulation of striatal dopamine receptor binding in suicide. Neuropsychopharmacology 2017, 42, 974–982. [Google Scholar]

- Anderberg, R. H. , Richard, J. E., Hansson, C., Nissbrandt, H., Bergquist, F., & Skibicka, K. P. GLP-1 is both anxiogenic and antidepressant; divergent effects of acute and chronic GLP-1 on emotionality. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2016, 65, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, K. , Thanos, P. K., & Gold, M. S. Dopamine and glucose, obesity, and reward deficiency syndrome. Frontiers in psychology 2014, 5, 919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amorim Moreira Alves, G. , Teranishi, M., Teixeira de Castro Gonçalves Ortega, A. C., James, F., & Perera Molligoda Arachchige, A. S. Mechanisms of GLP-1 in Modulating Craving and Addiction: Neurobiological and Translational Insights. Medical Sciences 2025, 13, 136. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, M. J. , Robinson, T. E., & Berridge, K. C. Incentive salience and the transition to addiction. Biological research on addiction 2013, 2, 391–399. [Google Scholar]

- Blum, K. , Oscar-Berman, M., Gardner, E. L., Simpatico, T., Braverman, E. R., & Gold, M. S. (, S: and neurobiology of dopamine in anhedonia. In Anhedonia: A Comprehensive Handbook Volume I: Conceptual Issues and Neurobiological Advances (pp. 179–208). Dordrecht.

- Egecioglu, E. , Engel, J. A., & Jerlhag, E. The glucagon-like peptide 1 analogue Exendin-4 attenuates the rewarding properties of psychostimulant drugs in mice. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e69010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquez-Meneses, J. D. , et al. GLP-1 analogues in the neurobiology of addiction: Translational insights and therapeutic perspectives. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2025, 26, 5338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves, G. A. M. , et al. Mechanisms of GLP-1 in modulating craving and addiction. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2025, 14, 1063033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qeadan, F. , et al. The association between glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist medications and substance use outcomes: A retrospective cohort study. Addiction 2025, 120, 1234–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquez-Meneses, J. D. , et al. GLP-1 analogues in the neurobiology of addiction: Translational insights and therapeutic perspectives. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2025, 26, 5338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, K. , Sharafshah, A., Khalsa, J., Uwe-Lewandrowski, K., Mohankumar, K., Thanos, P. K., Pinhasov, A., Baron, D., Dennen, C. A., Morgan, J. J., Lindenau, M., Elman, I., Gardner, E. L., Gold, M. S., Modestino, E. J., Brian, F., Carney, P. R., Cortese, R., Bowirrat, A., Madigan, M. A., … Badgaiyan, R. D. Precision Genomics: A Reality Having Universal Impact in a New Era of Psychiatry - Lessons Learned, Past and Present. Journal of addiction psychiatry 2025, 9, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modestino, E. J. , Bowirrat, A., Baron, D., Thanos, P. K., Hanna, C., Bagchi, D.,... & Blum, K. Is There a Natural, Non-addictive, and Non-anti-reward, Safe, Gene-based Solution to Treat Reward Deficiency Syndrome? KB220 Variants vs GLP-1 Analogs. Journal of addiction psychiatry 2024, 8, 34. [Google Scholar]

- Wise, R. A. , & Jordan, C. J. Dopamine, behavior, and addiction. Journal of biomedical science 2021, 28, 83. [Google Scholar]

- Yapici-Eser, H. , Appadurai, V., Eren, C. Y., Yazici, D., Chen, C. Y., Ongur, D., Pizzagalli, D. A., Werge, T., & Hall, M. H. Association between GLP-1 receptor gene polymorphisms with reward learning, anhedonia, and depression diagnosis. Acta Neuropsychiatrica 2020, 32, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C. , Liu, W. H., Yang, W., Chen, L., Xue, Y., & Chen, X. Y. GLP-1 modulated the firing activity of nigral dopaminergic neurons in both normal and parkinsonian mice. Neuropharmacology 2024, 252, 109946. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y. , Xu, B., Zhang, M. et al. Advances in GLP-1 receptor agonists for pain treatment and their future potential. J Headache Pain 2025, 26, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halloum, W. , Dughem, Y.A., Beier, D. et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists for headache and pain disorders: a systematic review. J Headache Pain 2024, 25, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X. , Zhao, P., Wang, W., Guo, L., & Pan, Q. The Antidepressant Effects of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. The American journal of geriatric psychiatry : official journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry 2024, 32, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, D. H. , Ramachandra, R., Ceban, F., Di Vincenzo, J. D., Rhee, T. G., Mansur, R. B., Teopiz, K. M., Gill, H., Ho, R., Cao, B., Lui, L. M. W., Jawad, M. Y., Arsenault, J., Le, G. H., Ramachandra, D., Guo, Z., & McIntyre, R. S. Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists as a protective factor for incident depression in patients with diabetes mellitus: A systematic review. Journal of psychiatric research 2023, 164, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gultekin, M. , Davran, F., Yuksel, N., Beyazcicek, O., & Demir, S. (2025). Assessment of serum glucagon-like peptide-1 and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 levels in patients with migraine. Acta neurologica Belgica, 10.1007/s13760-025-02894-w. Advance online publication. [CrossRef]

- Silverii, G. A. , Marinelli, C., Mannucci, E., & Rotella, F. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and mental health: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes, obesity & metabolism 2024, 26, 2505–2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Outcome | Mechanistic/Imaging | Pharmacovigilance | Clinical Trials/Meta-analyses | Overall Direction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression/anhedonia | fMRI reward blunting; HPA activation (moderate) | Mixed signal | Small improvements in some T2DM cohorts; mixed overall | Context-dependent |

| Anxiety | Acute anxiogenic in animals; stress markers ↑ | Weak–moderate signal | Inconsistent | Context-dependent |

| Suicidality | – | Rare signal; confounded | No consistent elevation vs controls | Insufficient |

| Headache/Migraine | Trigeminal/vascular mechanisms plausible | Headache signal present | Mixed; some neutral | Heterogeneous |

| Reward/drive | Dopamine tone ↓ with activation; incentive salience ↓ | – | Not prespecified in most trials | Potential blunting in vulnerable phenotypes |

| Substance use | Drug reward ↓ (benefit) | – | Early translational/observational signals | Bidirectional(benefit vs blunting) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).