Submitted:

23 October 2025

Posted:

24 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

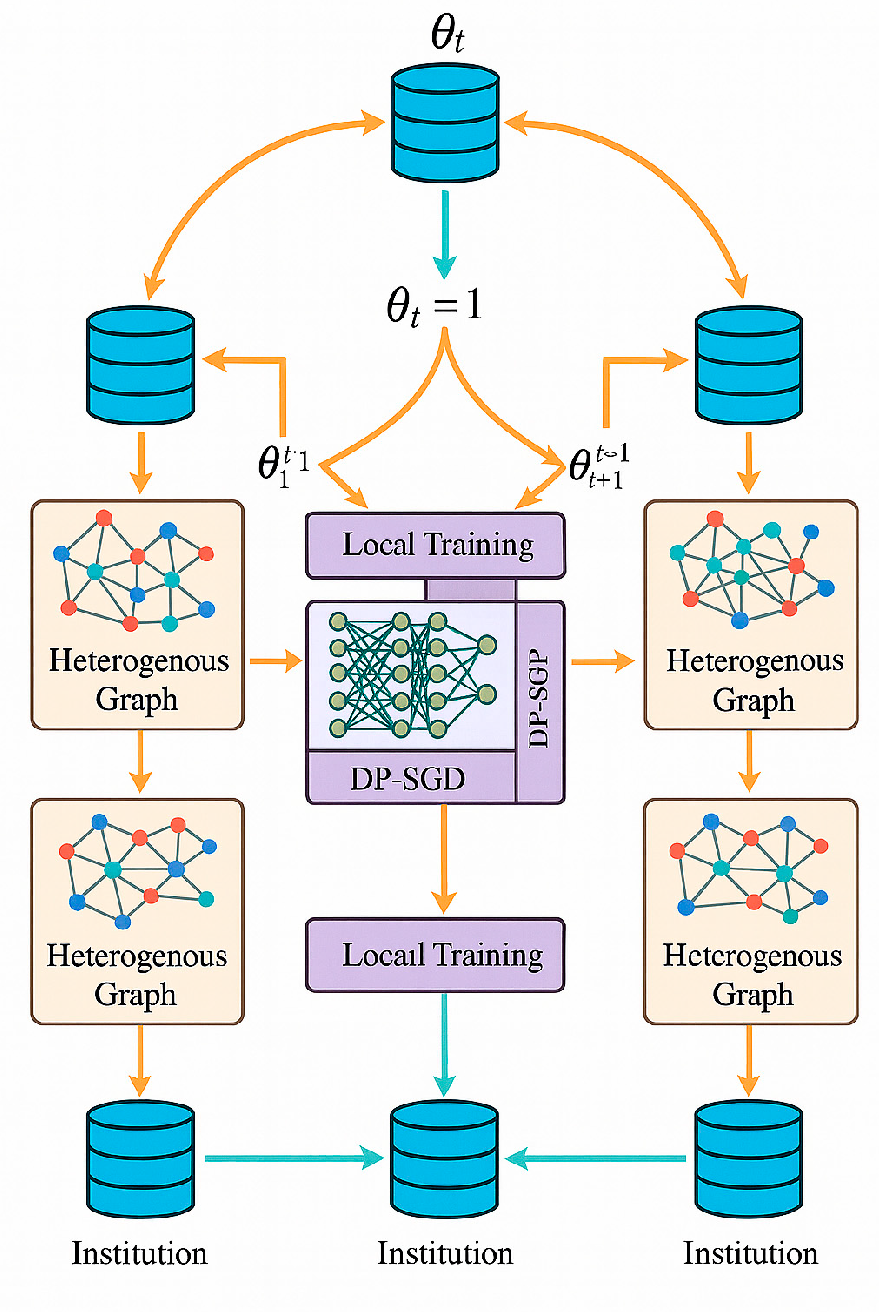

2. Fundamental Principles of Federated Learning

3. Design of Cross-Institutional Transaction Network Federated Learning Models

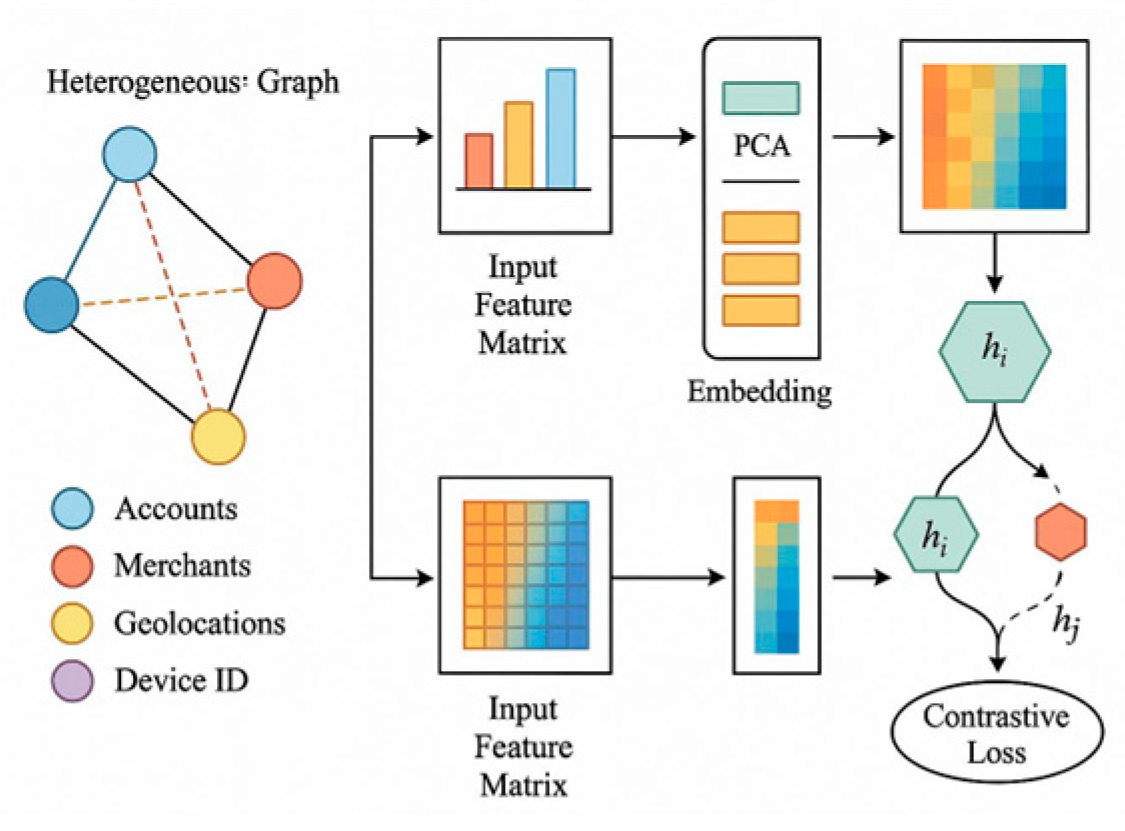

3.1. Basic Model Architecture

3.2. Privacy Protection Mechanism

3.3. Model Parameter Optimization

4. Implementation Approach for Federated Learning in Anti-Money Laundering Collaborative Modeling

4.1. Data Preprocessing and Feature Engineering

4.2. Federated Learning Algorithm Implementation

4.3. Model Training and Validation Workflow

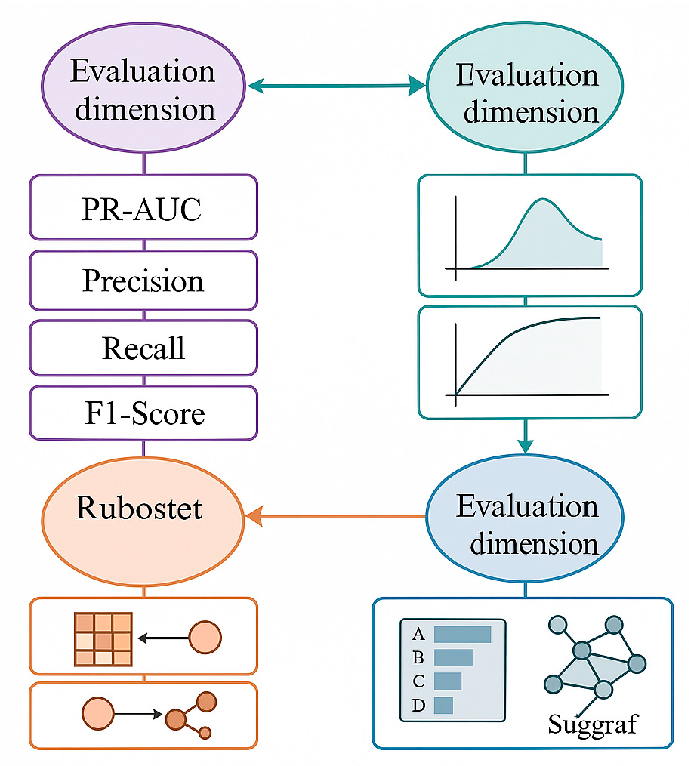

4.4. Performance Evaluation Metrics Design

5. Experimental Results and Analysis

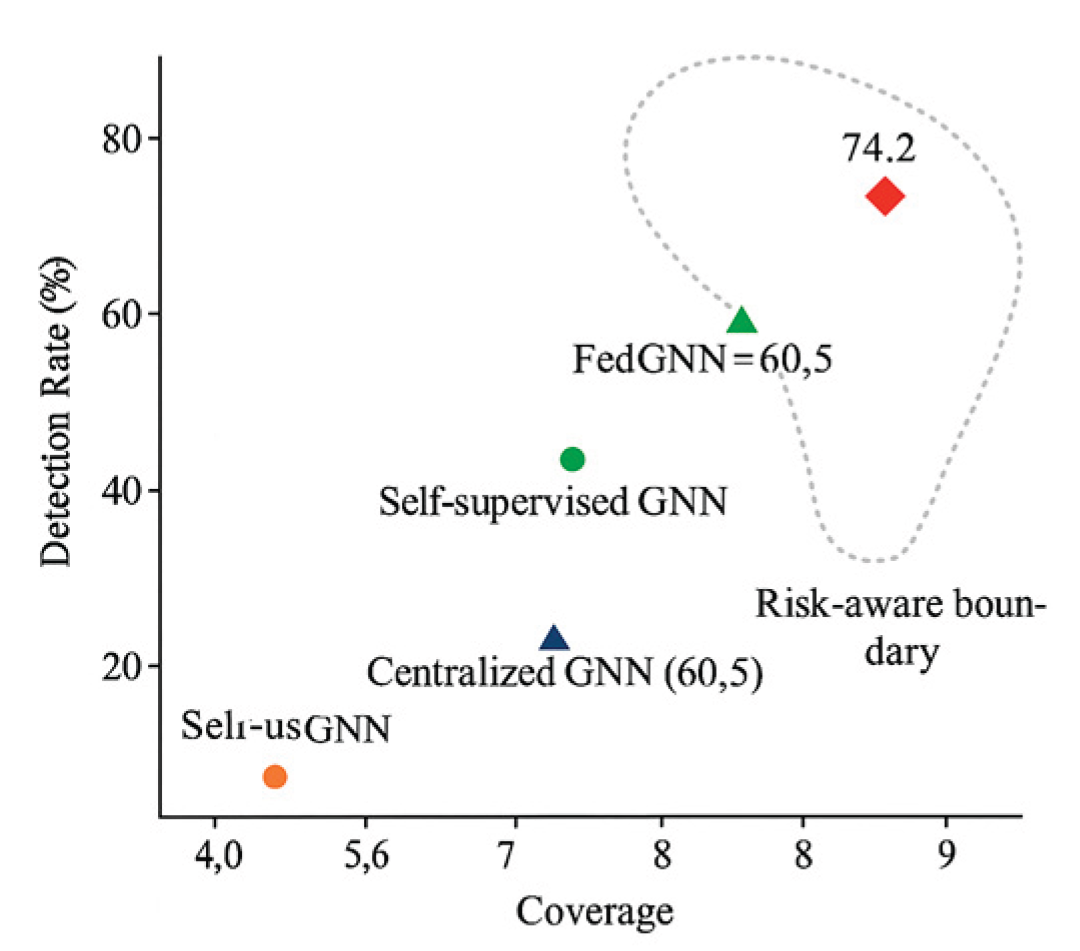

5.1. Experimental Design

5.2. Experimental Results and Analysis

6. Conclusions

References

- Ohinok S, Kopylchak M. International Cooperation in Combating Corruption and Money Laundering[J]. Екoнoміка рoзвитку систем, 2024, 6, 156–162.

- Gao S, Xu D. Conceptual modeling and development of an intelligent agent-assisted decision support system for anti-money laundering[J]. Expert Systems with Applications, 2009, 36, 1493–1504. [CrossRef]

- Gerbrands P, Unger B, Getzner M, et al. The effect of anti-money laundering policies: an empirical network analysis[J]. EPJ Data Science, 2022, 11, 15. [CrossRef]

- Wang Q, Tsai W T, Shi T, et al. Hide and seek in transaction networks: a multi-agent framework for simulating and detecting money laundering activities[J]. Complex & Intelligent Systems, 2025, 11, 271.

- Hu, L. (2025). Hybrid Edge-AI Framework for Intelligent Mobile Applications: Leveraging Large Language Models for On-device Contextual Assistance and Code-Aware Automation. Journal of Industrial Engineering and Applied Science,3(3), 10-22.

- Bociga D, Lord N, Bellotti E. Dare to share: information and intelligence sharing within the UK’s anti-money laundering regime[J]. Policing and Society, 2025, 35, 812–831.

- Akartuna E A, Johnson S D, Thornton A. A holistic network analysis of the money laundering threat landscape: Assessing criminal typologies, resilience and implications for disruption[J]. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 2025, 41, 173–214. [CrossRef]

- Khan A, Jillani M A H S, Ullah M, et al. Regulatory strategies for combatting money laundering in the era of digital trade[J]. Journal of Money Laundering Control, 2025, 28, 408–423. [CrossRef]

- Pramanik M I, Ghose P, Hossen M D, et al. Emerging Technological Trends in Financial Crime and Money Laundering: A Bibliometric Analysis of Cryptocurrency's Role and Global Research Collaboration[J]. Journal of Posthumanism, 2025, 5, 3611–3633. [CrossRef]

- Amoako E K W, Boateng V, Ajay O, et al. Exploring the role of machine learning and deep learning in anti-money laundering (AML) strategies within US financial industry: A systematic review of implementation, effectiveness, and challenges[J]. Finance & Accounting Research Journal, 2025, 7, 22–36.

| Model Type | PR-AUC (%) | Recall (%) | Precision (fixed ≥0.92) |

| Locally Trained GNN | 68.4 | 62.1 | ≥0.92 |

| Self-Supervised Pre-trained GNN | 73.2 | 67.4 | ≥0.92 |

| Federated GNN (without DP) | 75.9 | 69.2 | ≥0.92 |

| Centralized GNN (Full Data) | 76.5 | 71 | ≥0.92 |

| GFM (Proposed Method) | 89.1 | 80.3 | ≥0.92 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).