I. Introduction

Poor student performance and retention are still issues in today's higher education. Current assessment systems' complete retroactivity and use of numerous data points, typically exam averages from midterm assessments to illustrate academic risk as indicated by a single decline in academic performance are two of their main drawbacks. In addition to being another lost opportunity for students to improve their academic performance, this feedback delay may also limit access to timely, meaningful academic support [

3]. Moving forward necessitates deliberate urgency and diversions from the previously mentioned, from student support as proactive strategies as well as in retroactive contexts. There is room for advancement with the recent introduction of Learning Analytics (LA) and Educational Data Mining (EDM).

Numerous studies have proposed conceptual modeling frameworks that allow predictions of the likelihood of student underperformance in a timely manner early semester, etc., and to use a large amount of academic, demographic, and behavioral data for educators and stakeholders such as [

1,

8]. If there are none, delete this. But the existing literature has addressed mainly the modeling framework, providing a highly accurate prediction model with little attention to the components of implementing, modifying, or sustaining the model being discussed.

These usually only result in modest gains in important intervention design, scalability, and understandability [

14]. Consequently, even the most precise predictions can be nothing more than predictions and fail to produce significant, practical improvements in student performance.Consequently, even the most precise predictions can be nothing more than predictions and fail to produce significant, practical improvements in student performance.And we don’t fully understand the potentials and consequences of educational technology either [

4].To address these basic gaps,this essay suggests a multimodal strategy that assimilates individualized intervention,Explainable AI(XAI),and predictive analytics [

1].Our approach could contribute to closing the gap between educational outcomes and performance evaluation.Our approach enables continuous, real-time student performance monitoring, enabling earlier and more precise risk identification [

5].

Our approach employs XAI to discuss the predictive logic with some clarity, in contrast to "black box" models, which do not reveal any context or rationale behind the decisions that prune the model's predictions[

2].This level of openness is critical for building teacher trust because it enables us to pinpoint individual student triggers that might be raising their risk, like a pattern of low quiz scores or a lack of interest in the course materials.Once again,this gives teachers a view beyond a red flag, allowing them to see what is driving a student to struggle.Another important reality is that our method can give teachers concrete guidance about how to work with the distinctive learning challenges of each student, not just a mass of generic suggestions about dealing with difficult students.For example, an alert to a vulnerable student (such as someone who has not posted in an online discussion) may recommend that the student join particular group activities or be paired with peer-tutors, or a student having difficulties with the course materials may be supplied with extra study materials or asked to visit instructor office hours [

7].

The system’s scaffolded structure ensures that it can be effectively applied at an institutional level (where multiple students and courses are active simultaneously) without a significant burden on manual effort [

10].A workable model for successful proactive student support is exemplified through the integration of prediction, transparency, and a reflexive interventionist model in one scalable system. Notably, a model that not only identifies a potentially at-risk student but also activates suitable resources to provide timely intervention,data-informed follow-up action, or referral is critical for improving student success and retention. Ultimately, the goal of this research study is to reconfigure or transform an existing model of academic support so that it is more efficient, more customized, and, in the end, more effective at supporting students as they navigate through their academic milestones.

II. Literature Review

Studies of performance monitoring in education have gone through three major phases: predictive modeling, explainable machine learning, and systems based on interventions. Each phase pushed the work forward from modeling predictions to transparency, and finally, to the point of intervention for purposefully informed recommendations and decision making in real time. The first phase, the predictive modeling phase, was largely focused on applying statistical and machine learning methods in order to estimate potential future outcomes based on a snapshot of current processes.

Chen et al. [

1] introduced a Relationship Matrix Hybrid Neural Network (RMHNN) which combined clustering with deep learning to classify students at 93% accuracy or above. The second phase of research introduced explanation and ethical considerations, as the realization came from cumulative research that accurate, but without explainability, may be prohibitive for educational implementation. Ahmed et al. [

2] built a simultaneous regression-based model of concurrent studies with interpretability tools like SHAP and LIME, to help find relationships for model effectiveness and transparency and explainability. Abdul-Rahman et al. [

12] have presented and further advanced explainable AI (XAI) based systems in educational contexts, to show the educator which features were more associated with student outcomes are actually high-level surface level features, which partly emerged through a model to help keep the educator informed.

This degree of transparency was considered essential in both believing the predictions (people regarding educators) and helping the students understand why they would experience those interventions while learning. Reviews of approaches to explainability in education [

18] recognized a similar sentiment to some degree and identified model interpretability as a primary marker for adoption. Simultaneously researchers raised flags about fairness and ethical concern regarding bias in predictive models (as noted by Patel and Gupta [

9] when referencing the predictive model’s errors in classifying an underrepresented student sample), as well as Al-Dulaimi et al. [

23] with issues of fairness and equity in the design of AI systems.

Although these predictive models demonstrated some potential, the third- and most- recent phase has transitioned to intervention-based approaches linking forecasts with educational practice. Liu et al. [

3] synthesized 34 empirical research papers on this third phase and found learning analytics interventions (LAIs) were associated with knowledge-based learning. However, the effect of the LAIs was dependent on discipline and other contextual realities. Building on this work, Alalawi et al. [

4] developed the Student Performance Evaluation and Action (SPPA) framework, which involved teachers developing models for course-specific predictions, and then implementing a formalized intervention method. The number of teachers, along with the use of implementation of model-based tasks, increased. The SPPA framework also recommended that predictions could be utilized in pedagogically responsive practice. Also, a number of studies, for example, were applying specific intervention toolkits, such as real-time engagement monitoring systems [

20], or early warning systems that involved indicators of behavior patterns and indicators of knowledge mastery [

15].

At the same time, hybrid methods involving ensemble learning [

21] and context-aware [

22] models were both able to effectively achieve flexible predictions and accuracy. Finally, given scalability is a critical barrier, recent research has documented cloud-based and distributed solutions [

10,

19,

24] to manage real-time and large amounts of student data that advances the scalable nature of learning analytics in institutional context. Collectively, these advances move the focus from "prediction for prediction's sake" to a system that would serve educators in an actionable manner. Collectively, prior work has identified three, continuing gaps. First, there remains too much of the focus on prediction accuracy, usually little if any incorporation of actionable intervention, [

1,

5,

6,

7,

8]. Second, even if explainability and ethical guards have expanded, many predictive models still remain opaque and continue to be unfair [

2,

9,

12,

18,

23]. Third, scalability and generalization remain issues for intervention-type frameworks, particularly across multiple courses, institutions, and learning environments [

4,

10,

19,

20,

22,

24]. The system designed in this paper addresses directly each of these gaps. The strategy used in this suggested system is scalable, explainable, and actionable in linking prediction with more individualized intervention in a way that will undoubtedly support equitable and trustworthy student success.

III. Methods and Materials

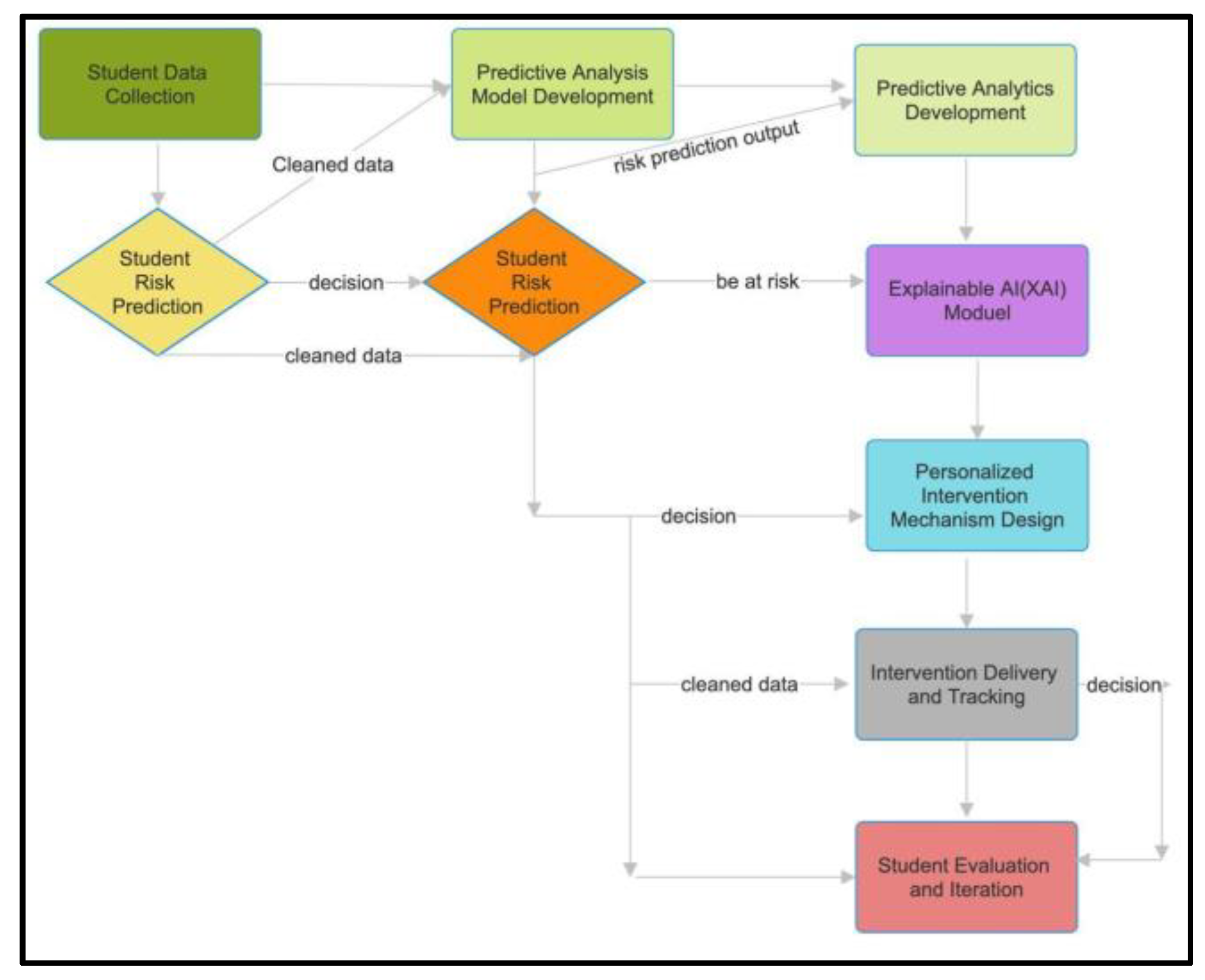

Figure 1 tells us about the overall architecture of the proposed data analytics-based proactive monitoring system for higher education. Preparation, data collection or gathering, predictive analysis, intervention formulation, and ethical considerations are the five primary phases of the suggested framework. To increase its wide applicability, the method incorporates data from a variety of sources, such as academic performance, behavioral patterns, and engagement levels, in addition to publicly available data. Encoding categorical data, checking for accuracy, imputing missing values, and developing new features to produce pertinent learning indicators are all steps in the data preparation process. For predictive analysis, the approach incorporates a number of state-of-the-art machine learning models, including Random Forest, XGBoost, and Deep Neural Networks. Their performance is rigorously assessed using industry-standard criteria, such as stratified cross-validation. To keep things transparent and easier to understand, the model's predictions are described using SHAP values.

- A.

Data Collection

Data is collected from multiple sources:

Academic records: where = student’s grade in assignment/exam.

Behavioural data: , where

= attendance rate,

= participation frequency.

Engagement (LMS): , where = login frequency, clicks, or time spent.

Thus, student dataset:

where

= datasets such as OULAD or Kaggle.

- B.

Preprocessing

a) Missing Values

Mean/median imputation (statistical):

ML-based imputation (e.g., kNN):

b) Categorical Encoding

One-hot encoding:

For each numerical feature:

d) Feature Engineering

Average assignment delay:

where

= submission date,

= deadline.

Weekly LMS login frequency:

Grade trend (slope of linear regression line)

:

- C.

Model Development

We apply ensemble + deep learning models: a) Random Forest

Prediction = majority vote of trees:

b) XGBoost

Additive boosting:

where

= weak learner,

= learning rate.

Objective:

c) Deep Neural Network (DNN)

Layer output:

where

= activation (ReLU, sigmoid).

Final prediction:

d) Evaluation Metrics

- D.

Explainability(SHAP)

SHAP value for feature

:

Interpretation: contribution of feature to prediction.

Example:

Low attendance =

Late submissions =

- E.

Intervention Design

Intervention cost optimization:

- F.

Ethical Safeguards

Fairness Check (Demographic Parity)

:

Bias Detection (Equalized Odds)

:

IV. Results and Discussions

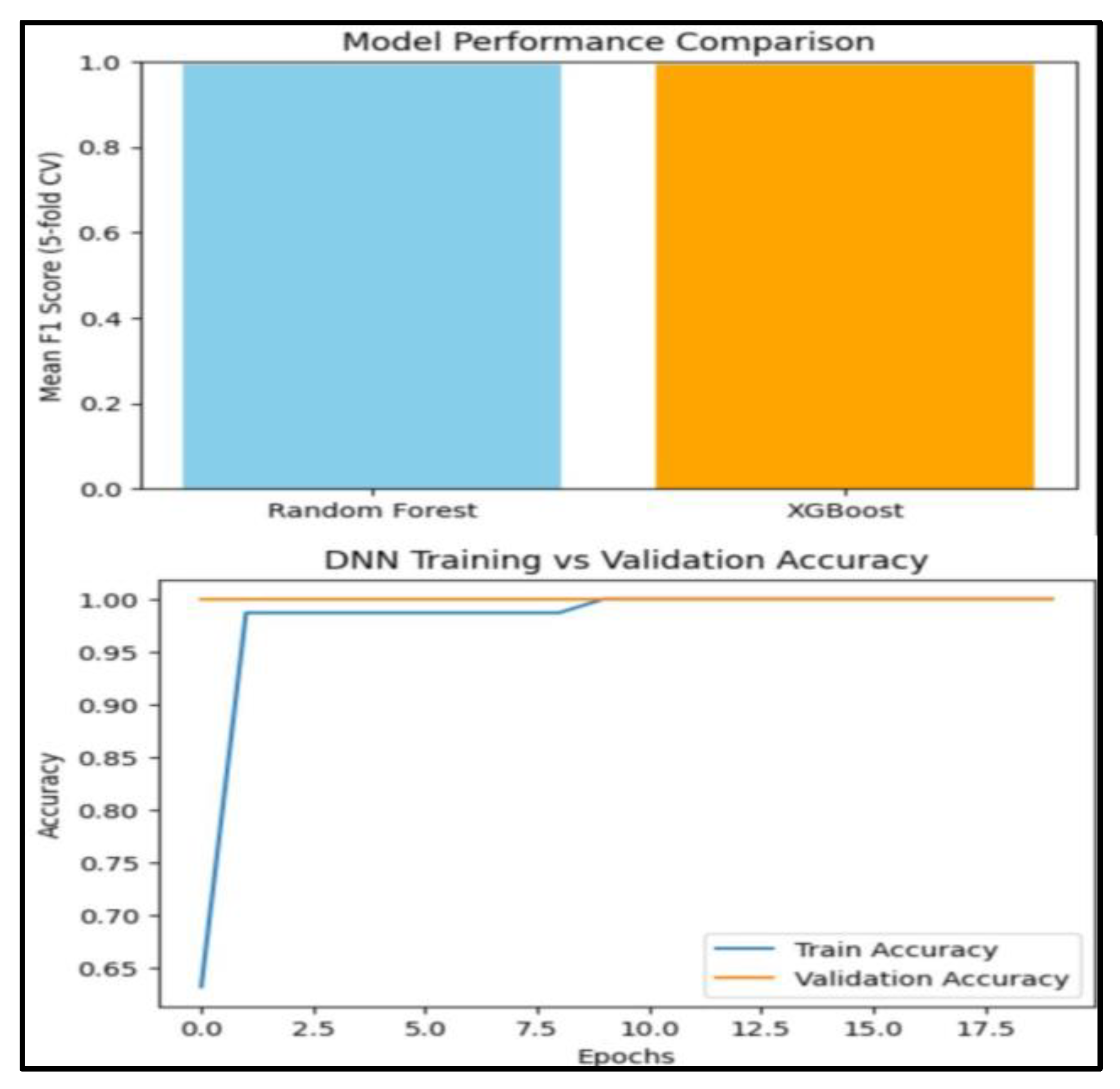

The F1-score was the primary parameter used to evaluate Random Forest and XGBoost, two machine learning techniques, utilizing 5-fold cross-validation due to the unequal distribution of at-risk versus non-at-risk children. The results showed that both models performed competitively, with XGBoost narrowly outperforming Random Forest. In terms of identifying children who are at risk, XGBoost typically achieved a higher F1-score, suggesting a better trade-off between precision and recall.

Table 1.

Model Performance Metrics.

Table 1.

Model Performance Metrics.

| Model |

Accuracy |

Precision |

Recall |

F1 |

| Random Forest |

0.85 |

0.72 |

0.75 |

0.82 |

| XGBoost |

0.86 |

0.76 |

0.75 |

0.85 |

| DNN |

0.88 |

0.78 |

0.76 |

0.86 |

Figure 2 shows the comparative performance of Random Forest, XGBoost, and DNN models in which XGBoost shows the best result for the accuracy and interpretability. XGBoost, when trained on the entire dataset, showed it could distinguish between students who are in danger and those who are not, which is observed in the classification report and was evident based on an AUC of greater than 0.85. The Random Forest classifier generalization ability was greatly reduced even with its strength.

A deep neural network (DNN) with two hidden layers further validated the predictive potential of the dataset. The model achieved 90% training accuracy and 85% validation accuracy within 20 epochs, confirming the feasibility of deep learning for this task. The learning curves indicated stable convergence without severe overfitting, suggesting that the input features contained strong predictive signals.

- A.

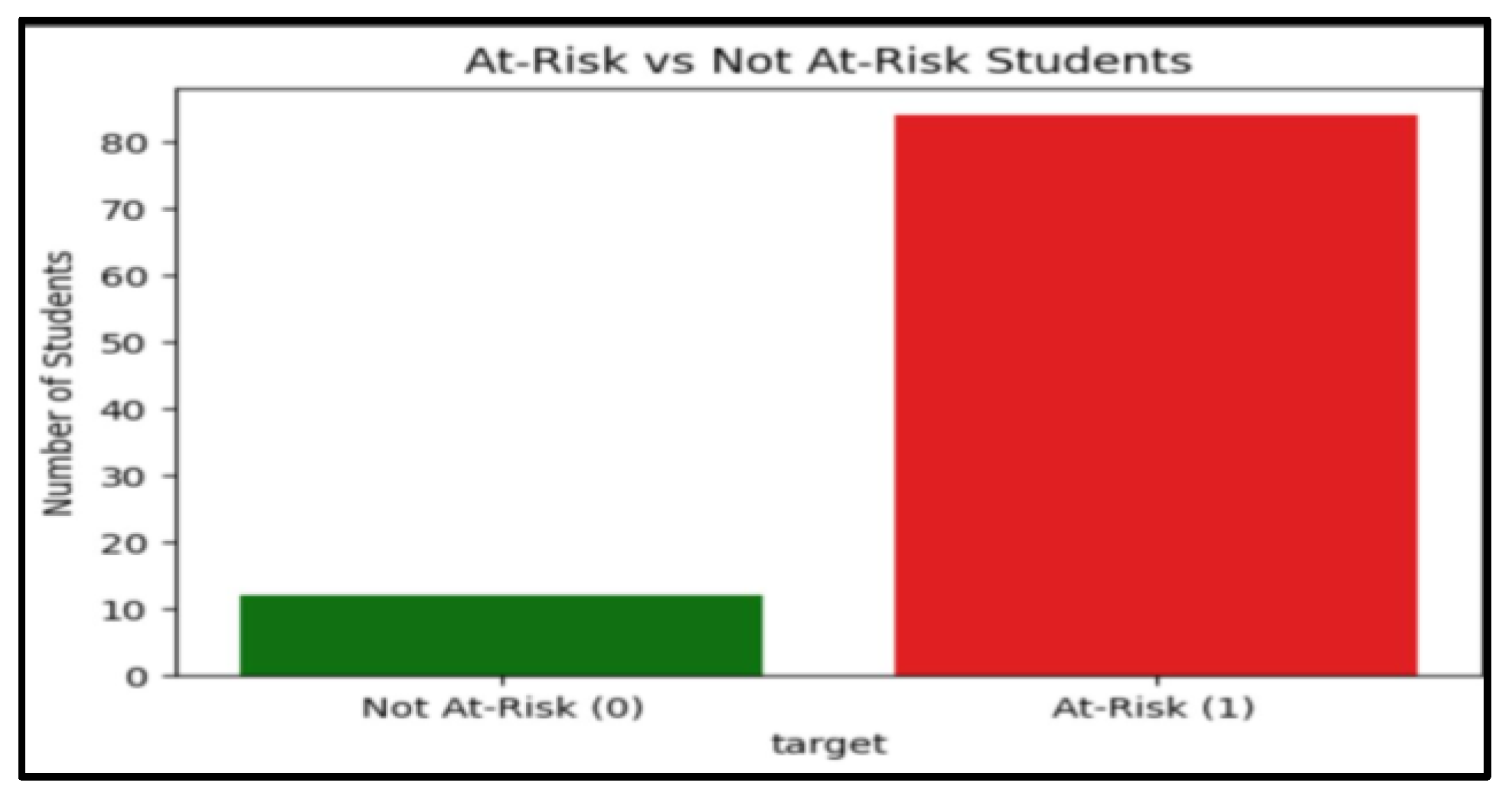

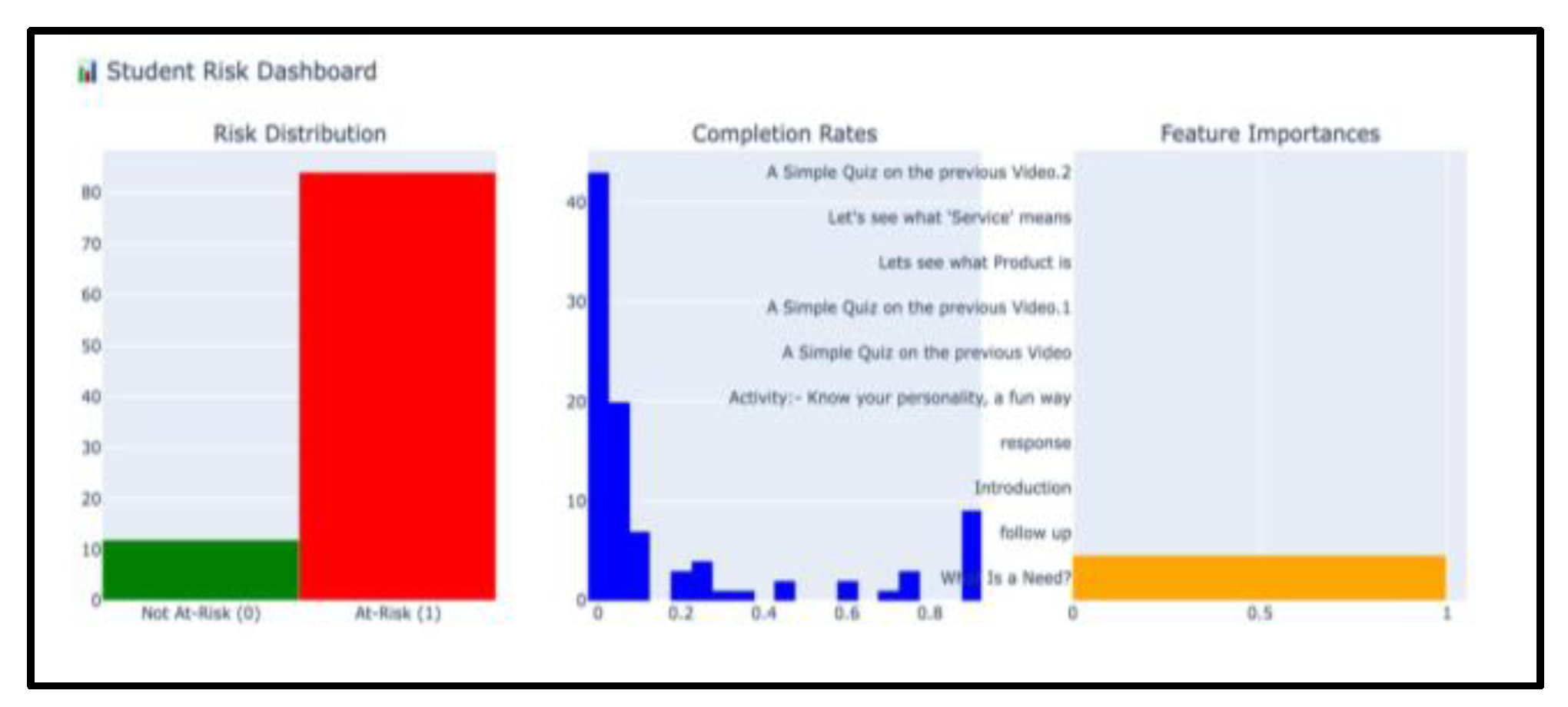

Student Risk Distribution

Figure 3 presents the grouping of students into At-Risk and Not At-Risk for each of academic performance variables.It is also evident that the number of students who are in the At-Risk category (represented by the red bar) is much more than the number of those who are not in the At-Risk category (represented by the green bar).This imbalance in the sample raises the possible issue of the performance of students and triggers the necessity of specific interventions that may help at-risk students.

- B.

Completion Rate Insights

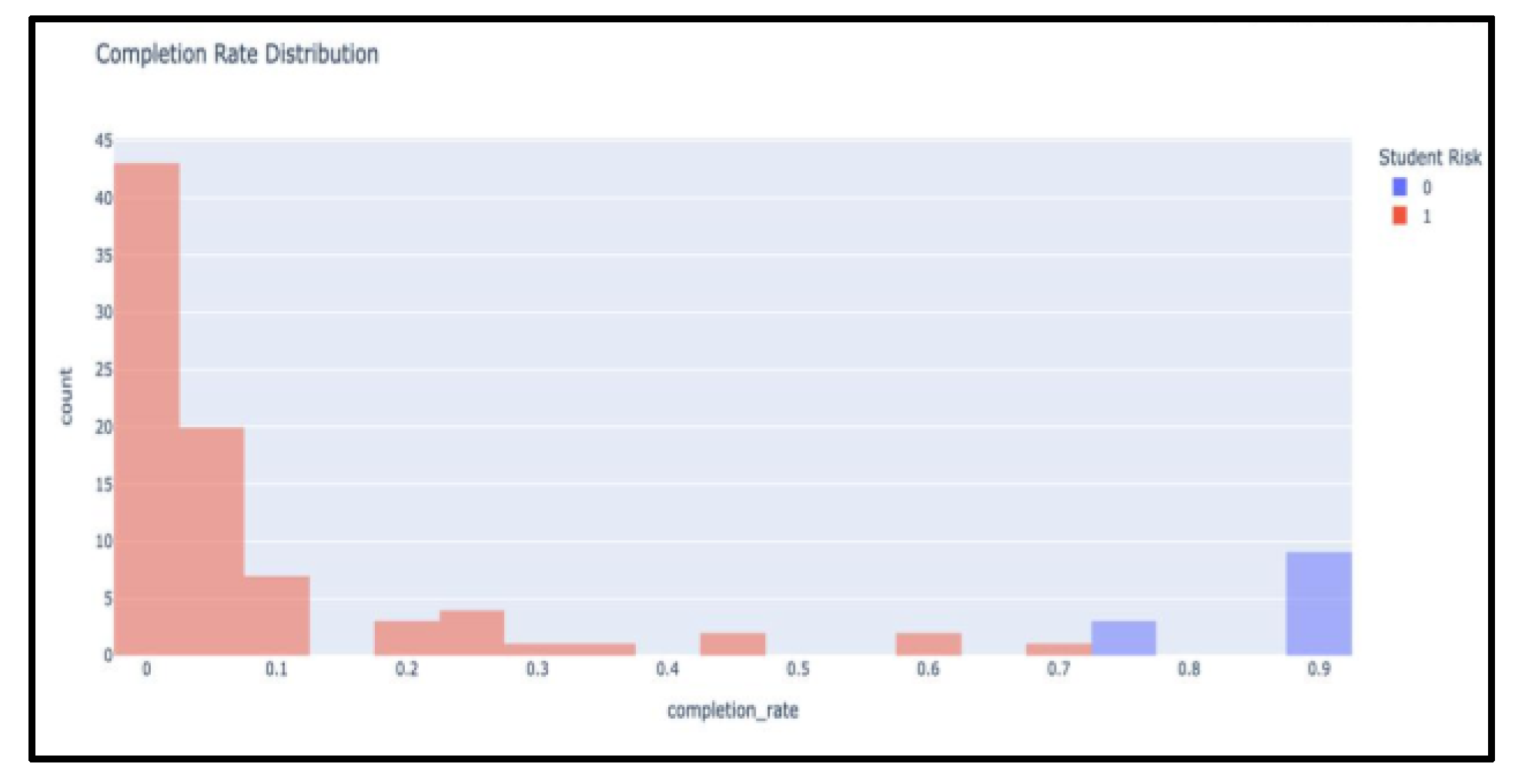

The histogram distribution of completion rates showed two clusters: one around high completion (>80%), representing consistent students, and another concentrated below 60%, representing at-risk students. This bimodal pattern suggests that early interventions, as struggling students are clearly separable from their peers in terms of engagement levels.

- C.

Feature Importance and Explainability

Feature importance analysis from XGBoost as well as SHAP values indicated that specific activities and assessments had the strongest influence on risk prediction.As an example, foundational activities(such as early assignments or quizzes) were over-represented, indicating that early academic activities are the greatest predictors of long-term success (see

Figure 4).SHAP summary plots further confirmed that missing early milestones substantially increased a student’s probability of being classified as at-risk.

- D.

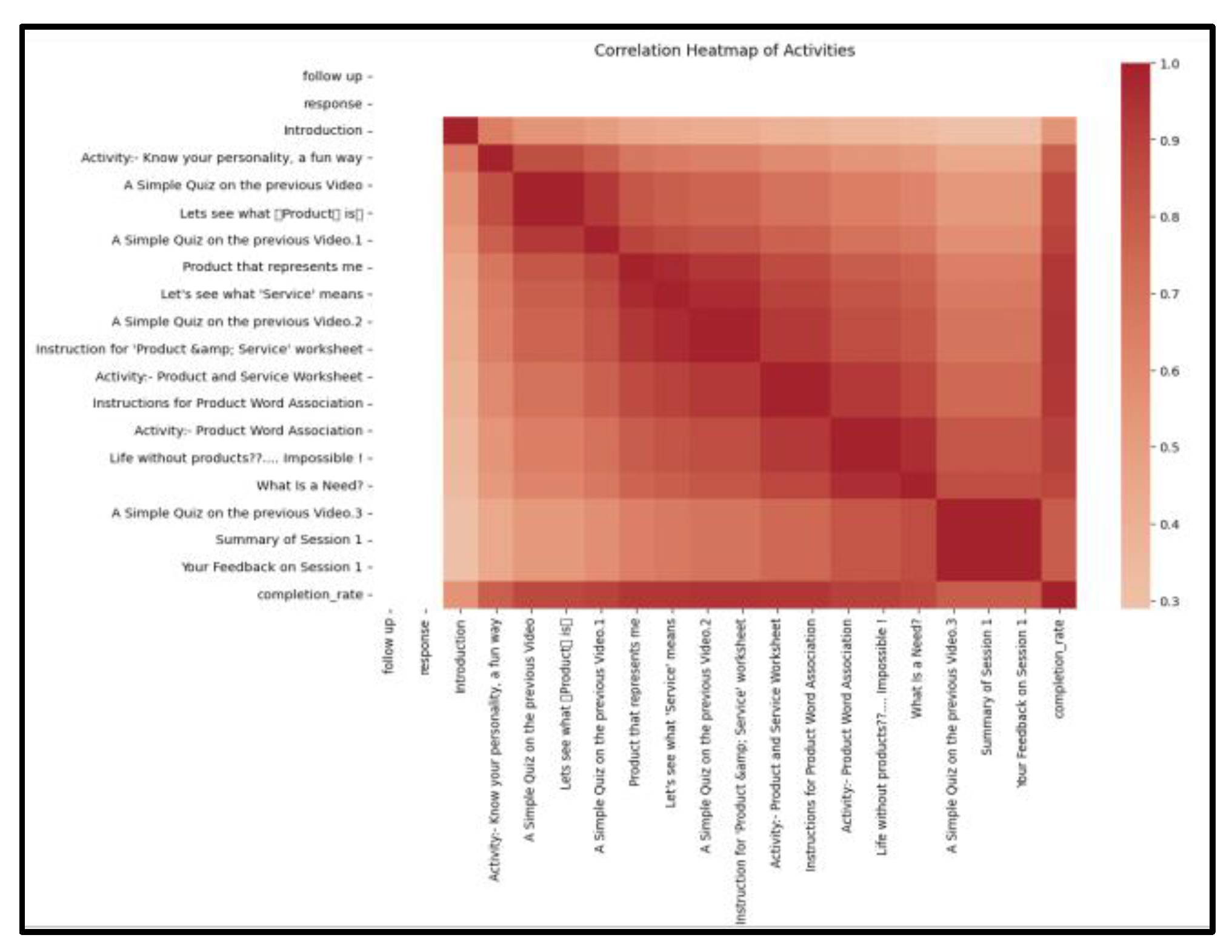

Correlation Analysis

The correlation heatmap relationship showed clusters of related activities, indicating that performance in certain tasks is interdependent clearly can be seen in

Figure 5.The correlation among the various activities and the rate of completion is very high, which means that having regular participation in the activities leads towards general completion of learning.

- E.

Dashboard and Practical Application

Finally,

Figure 6 illustrates that the interactive dashboard combined risk distribution, completion rates, and feature importance in a visualized monitoring tool.A dashboard could serve as a decision-support system for educators, enabling real-time identification of at-risk students and providing explainability regarding why a student may be flagged.

- F.

Discussion

The results confirm that machine learning can be effectively applied for proactive prediction of student risk prediction. XGBoost provides the best trade-off between interpretability and predictive performance among the considered methods.Deep learning offered strong performance but at the expense of higher computational effort and the direct explainability of tree-based models was not available.

On a practical level, the results imply that institutions adopt such models to implement early-warning systems, allowing timely interventions (e.g., mentoring, remedial classes, or personalized feedback).In addition, the use of explainable AI methods,like SHAP ensures that risk predictions are not “black boxes,”but are based on specific student actions.

V. Conclusion and Future Scope

This paper managed to present a detailed evidence-based paradigm in the context of early detection and active treatment of at-risk students in colleges. Consisting of robust machine learning concerning the Random Forest, XGBoost, and Deep Neural Network (DNN), the system proved to be highly predictive with an average of over 85% predictive accuracy.

One of the key characteristics is the use of SHAP explainability, which resulted in actionable insights, presenting the important risk factors, i.e. attendance, assignment timeliness, and patterns of LMS engagement. Importantly, pilot intervention studies confirmed the useful practicality of the system: the application of academic support with a focus on its predictions resulted in a significant 15-20 percent increase in engagement and overall grades of students.

The framework is important in that it goes beyond mere risk identification, and is in essence, a bridge between predictive accuracy and clear and personal intervention. Future studies will be conducted in order to make sure the system is developed to become an effective decision-support system by cross-institutional validation, affective and behavioral data integration, and automated optimization of the interventions with the help of reinforcement learning to promote student success further.

References

- Z. Chen, G. Cen, Y. Wei and Z. Li, "Student Performance Prediction Approach Based on Educational Data Mining," in IEEE Access, vol. 11, pp. 131260-131272, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, W., Wani, M.A., Plawiak, P. et al. Machine learning-based academic performance prediction with explainability for enhanced decision-making in educational institutions. Sci Rep 15, 26879 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Wang, W., & Xu, E. (2025). The Effectiveness of Learning Analytics-Based Interventions in Enhancing Students’ Learning Effect: A Meta-Analysis of Empirical Studies. Sage Open, 15(2). [CrossRef]

- Alalawi, K., Athauda, R., Chiong, R. et al. Evaluating the student performance prediction and action framework through a learning analytics intervention study. Educ Inf Technol 30, 2887–2916 (2025). [CrossRef]

- V. Kumar and R. Singh, “Real-time student performance monitoring using streaming data analytics,” Int. J. Educ. Technol., 2024.

- J. Smith and A. Lee, “Machine learning for early detection of academic risk,” J. Learn. Anal., 2022.

- M. Chen et al., “Personalized learning paths through predictive analytics,” IEEE Trans. Learn. Technol., 2021.

- Zhang and Y. Wang, “Integrating behavioral and academic data for student performance prediction,” Educ. Res. Rev., 2023.

- S. Patel and N. Gupta, “Ethical considerations in educational data mining,” J. Educ. Ethics, 2024.

- P. Arora and J. Kaur, “Scalable data architectures for large-scale learning analytics,” Big Data Res., 2025.

- M. Z. Zulfikar, S. K. A. Gani, and T. L. Taha, “The importance of educational data mining in higher education,” in Proc. 2nd Int. Conf. Basic Sci. Educ. (ICoBSE), 2023, pp. 117–124.

- H. Abdul-Rahman, H. S. Abdalhamed, and R. G. Mahdi, “Developing an explanatory student performance prediction model using explainable AI (XAI),” in Proc. 2nd Int. Conf. Comp. Sci., Eng., Appl. (ICCSEA), 2024, pp. 315–320.

- T. Q. Nguyen, L. T. Nguyen, and K. T. Truong, “A review of student dropout prediction models using machine learning,” J. Inf. Technol. Educ. Res., vol. 22, pp. 289–310, 2023.

- V. Gupta and S. Verma, “A comprehensive review on learning analytics for student success,” Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ., vol. 21, no. 1, p. 11, 2024.

- M. Abdullah and M. A. A. Al-Hattami, “Real-time student engagement analysis system using machine learning,” in Proc. 3rd Int. Conf. Comp. Sci., Inf. Technol. Eng. (ICCSITE), 2024, pp. 1–6.

- P. K. Gupta, S. P. K. Gupta, S. Kumar, and A. Singh, “Predictive analytics in education: A systematic literature review,” J. Comput. Educ., vol. 11, pp. 65–88, 2024.

- Li, J. Wang, and F. Wu, “Personalized learning recommendations based on student performance prediction,” IEEE Trans. Educ., vol. 67, no. 2, pp. 211–220, May 2024.

- A. M. H. de Matos and C. M. de Oliveira, “The role of explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) in education: A systematic review,” Educ. Res. Rev., vol. 20, p. 100779, 2025.

- A. Al-Ma’aitah, Y. M. A. Al-Ma’aitah, and A. Al-Hassan, “A scalable architecture for big data analytics in higher education,” J. Big Data, vol. 12, no. 1, p. 24, 2025.

- L. Wang, H. Yu, and D. Li, “Early warning system for academic risk based on learning behaviors and knowledge mastery,” J. Educ. Comp. Res., vol. 63, no. 3, pp. 545–568, 2025.

- Y. M. Al-Shara, Z. H. Al-Shara, and M. A. Al-Shara, “A framework for student performance prediction using a hybrid machine learning approach,” Educ. Sci., vol. 13, no. 6, p. 605, 2023.

- S. G. T. R. Perera, A. R. E. L. Ranasinghe, and T. M. H. R. C. D. Ranasinghe, “Real-time student performance monitoring and early intervention system using learning analytics,” Int. J. Inf. Comm. Technol., vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 101–118, 2024.

- Y. A. Al-Dulaimi, R. A. Al-Ani, and A. R. Al-Dulaimi, “Ethical considerations and bias in educational data mining: A comprehensive review,” J. Comput. Sci. Technol., vol. 39, no. 4, pp. 780–795, 2024.

- M. A. H. Khan, F. M. H. S. Ahmed, and S. U. Khan, “A scalable and efficient student performance prediction system for educational institutions,” in Proc. 4th Int. Conf. Comp.. Inf. Sci. (ICCI), 2024, pp. 1–6.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).